ABSTRACT

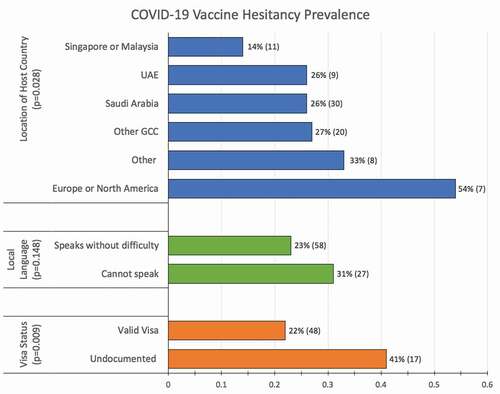

The COVID-19 pandemic poses an extraordinary threat to the health, safety, and freedom of temporary foreign workers (TFWs). Highly effective vaccines against COVID-19 may hold an outsized benefit for TFWs, particularly those living in congregate settings where protective measures such as social distancing are not possible. While some studies of migrant destination countries have included migrants, no study to date has sought to understand variations in vaccine hesitancy among individuals in a single migrant source population across different destinations. Such a design is critical for understanding how the context of immigration affects levels of hesitancy among migrants from similar conditions of origin. This observational study leverages longitudinal data from an ongoing monthly rapid-response survey of TFWs from Bangladesh (n = 360). Overall vaccine hesitancy was 25%, with significant variation by host country. Multivariate analyses confirmed that immigration system factors and threat perception are the strongest predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for TFWs. The predicted probability of hesitancy for an undocumented TFW was 0.405, while the predicted probability for those with valid visas was 0.207 (p < .01). The probability of being hesitant for TFWs who were worried about getting COVID-19 was 0.129 compared to 0.305 (p < .01) for those who were not worried. Results reveal low vaccine hesitancy among TFWs from Bangladesh with differences in location, undocumented status, COVID-19 threat perception, and level of worry about side effects. There could be relatively high returns for targeting vaccine access and distribution to TFWs because of their high levels of vaccine acceptance.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic poses an extraordinary threat to the health, safety, and freedom of temporary foreign workers (TFWs). TFWs are uniquely vulnerable because their right to remain in a country depends on their ability to work.Citation1 Facing massive pandemic-induced shifts in the labor market, TFWs may face deportation or be required to step into increasingly dangerous work roles in order to preserve their legal status. These concerns are especially present in the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a six-nation bloc where up to 90% of the workforce is foreign-born and where persistent concerns have been raised about human rights violations, occupational conditions, emotional and physical abuse, and indebtedness of TFWs.Citation2 In addition to the vulnerabilities facing migrants, recent work has shown that migration-dependent households in sending communities experience economic hardships such as decreases in earnings and food insecurity at higher rates than non-migrant households, and hardships exacerbated by the stigma that returning migrants are responsible for the spread of COVID-19.Citation3,Citation4

Highly effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may thus hold an outsized benefit for TFWs, particularly those living in congregate settings where protective measures such as social distancing are not possible.Citation4,Citation5 Access to and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine can help ameliorate threats to migrants and their families back home. Timely, effective, and equitable vaccine distribution is necessary,Citation6 but not sufficient, to ensure widespread protection against COVID-19, as vaccination programs rely on high uptake levels in order to slow transmission and provide direct and indirect protection.Citation7,Citation8 Vaccine hesitancy, defined as “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services,”Citation9 is a growing worldwide issue and was declared one of the top ten global health threats by the WHO in 2019.Citation10,Citation11 The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy groups determinants of vaccine hesitancy into three categories: contextual, individual and group, and vaccination-specific influences.Citation9,Citation12 Studies using this framework prior to the COVID-19 pandemic found that the top three reasons for vaccine hesitancy were 1) risk/benefit perceptions (i.e., safety concerns, fear of side effects, fear of contracting disease), 2) lack of knowledge/awareness of vaccination and its importance, and 3) religious, cultural, gender-based and socioeconomic issues.Citation10 Reasons for hesitancy varied by context, including country income level and WHO region, highlighting the importance of research examining country-specific factors.Citation10

Global studies focused specifically on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance have shown some promising results and also highlighted areas of concern. A systematic review conducted in December 2020 showed global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance to be around 70%, although acceptance varied largely by country and region.Citation13,Citation14 Acceptance was highest in Asia and Latin America (exceeding 90% in China, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Ecuador), lower in Europe and the US (53–59% in Italy, Poland, France, and US), and lowest in the Middle East, particularly in Kuwait (23.6%) and Jordan (28.4%).Citation13,Citation14 Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy mirrored those of general vaccine hesitancy in terms of risk/benefit concerns about safety and side effectsCitation13,Citation15–17 and religious, cultural, gender-based, and socioeconomic issues regarding vaccines.Citation13,Citation18

While there is limited work on vaccine hesitancy among Bangladeshis at home or abroad, or among TFWs more generally, early studies point to the importance of understanding vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in this highly mobile and vulnerable population. Studies in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, common host countries among Bangladeshi TFWs, found that being a foreign national was associated with lower COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.Citation19,Citation20 In Bangladesh, a cross-sectional study showed national COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy to be 32.5%. Hesitancy was associated with being older, male, married, a tobacco user, having no physical illness in the last year, and being less concerned about COVID-19 for oneself or family.Citation21 While some studies of vaccine hesitancy in migrant destination countries have included migrants, no study to date has sought to understand variation in vaccine hesitancy among individuals in a single migrant source population across different destinations. Such a design is critical for understanding how the context of immigrant reception affects levels of hesitancy among migrants from similar conditions of origin. The objective of this study was to evaluate vaccine access and acceptance among a population of TFWs from Bangladesh and contribute to understanding vaccine hesitancy in the context of global migration.

Conceptual Framework

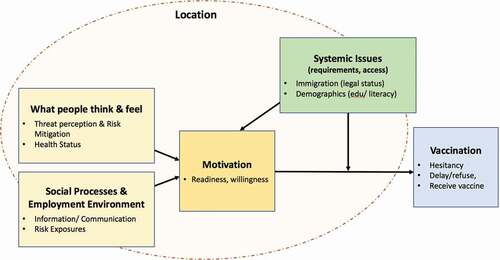

This study was informed by the WHO Behavioral and Social Drivers of vaccination (BeSD) model () which posits that vaccine attitudes and behavior are a product of: 1) what people think and feel, 2) social processes, and 3) systemic issues that impact practical access considerations and motivation. We have adapted this model to apply to TFWs by considering how location influences all domains, including the key aspect of employment conditions given the degree of employer control over TFWs, and recognizing that practical issues are systemic and influence both outcomes and motivation.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework WHO behavioral and social drivers of vaccination (BeSD) model applied to temporary foreign workers

We have three hypotheses about vaccine hesitancy for TFWs from Bangladesh that focus on factors relating to immigration:

Hypothesis 1 Destination: Vaccine hesitancy will vary by host country. Integration into the host community, legal status, and living conditions could mediate country-level differences.

Hypothesis 2 Legal Status: Undocumented TFWs will have higher a higher prevalence of vaccine hesitancy compared to those with valid visas.

Hypothesis 3 Integration: As integration increases (longer time in country, increased language acquisition), TFWs will have a lower prevalence of vaccine hesitancy.

In addition to testing these hypotheses, we also model the confounding effects of health, threat perception and risk mitigation, risk exposures, and information. These domains are informed by the BeSD model and represent possible mechanisms for hesitancy. Given our focus on TFWs from a single country of origin, our goal is to leverage information about differences attributable to migration.

Methods

Study Design & Sample

This observational study leverages longitudinal data from an ongoing monthly rapid-response survey of TFWs from Bangladesh (n = 360) and builds on the unique longitudinal data of the Research and Empirical Analysis of Labor Migration (REALM) Bangladesh cohort study (n = 1,436). Respondents from the Matlab Subdistrict, a rural area 50 km from Dhaka, were interviewed in 1996, 2012, and 2017–19 with an intensive survey covering migration processes, social and migrant networks, indebtedness, remittances, living conditions, occupational risks, and health. The current follow-up study screened 881 REALM respondents for eligibility (criteria: active phone number and living abroad in January 2020), 381 of whom were enrolled and completed baseline interviews. Phone surveys began September 11, 2020, and continue through September 2021. Interviews were conducted in Bangla by trained staff fluent in both English and Bangla and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

Follow-up data are available for 360 individuals, for whom we report variation in vaccine uptake and hesitancy. Multivariate analyses focused on a subsample of 253 respondents who were still abroad in the fifth month of data collection (Jan/Feb 2021) and who had not already received or refused the COVID-19 vaccine (82 excluded because they had returned to Bangladesh, 25 excluded because they had already received or refused the vaccine). Protection of human subjects during fieldwork and data analyses were ensured under the icddr,b Ethical Review Committee Protocol #PR-10005.

Measures

The monthly survey included modules on demographics, employment, return migration, COVID-19 risk perception, social distancing/protective behaviors, access to care, general well-being, COVID-19 knowledge and symptoms, COVID-19 vaccine, politics and government, and family (children’s schooling, economic security, social contact).

Dependent Variables

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was defined as rejection of or uncertainty toward a hypothetical vaccine offer. If an individual answered “no” to the question “Have you received the vaccine for COVID-19” and “no” to the question “Have you been offered the vaccine for COVID-19,” they were asked “Would you take the vaccine for COVID-19 if it were offered to you?” Answers of “No” or “I’m not sure right now” were coded as vaccine hesitant. “Yes” responses were coded as vaccine acceptant/not hesitant.

Independent Variables

The prior surveys (1996, 2012, 2017–19) included self-reports of age, education, marital status, occupation, and physical and mental health. These responses were confirmed in the 2020 baseline survey as consistency checks, with physical and mental health questions repeated on a monthly basis. Vulnerability to severe COVID-19 complications was assessed using self-reports of the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) list of underlying medical conditions.Citation22 In addition to the aggregate measure of any CDC risk factor, smoking status, obesity, self-reported health, and depression were measured separately. Depression was determined using the CES-D scale.Citation23 Location (measured at the country level) was confirmed at the beginning of each monthly interview. Visa status was measured for all respondents who were not in Bangladesh at the time of the interview by first assessing whether their visa status had changed since the last interview and with the follow-up question “In the past 30 days, did you have an active work visa or work permit letter to live in [host country]?” Language ability was a self-reported measure captured in the 2017–2019 survey and was dichotomized based on speaking ability (cannot speak local language versus speaks without difficulty). Duration abroad was a total measure of time overseas as a TFW since first migration. This was measured as a continuous and categorical variable. COVID-19 threat perception was measured by the question “Right now, how worried are you about getting COVID-19?” Fear of vaccine side effects was asked of all respondents who had not yet received the vaccine. Responses to both questions were dichotomized into worried versus not worried. Social distancing was measured using prior 7-day recall as to whether the respondent always wore a mask when leaving the house and/or maintained two meters distance from people outside of their household. Risky behavior was measured with 7-day recall of engagement in one or more of seven activities that could increase risk of COVID-19 exposure, such as attending Friday prayers at the mosque or eating in restaurants. Additional exposure risks were assessed by the presence of COVID-19-positive individuals in a respondent’s housing unit or worksite and whether or not they lived in crowded housing, defined as five or more people sharing a bedroom. Exposure to non-COVID-19 occupational abuses and hazards were assessed using data from the 2017–2019 survey. Abuse by employer was measured as whether or not a TFW had experienced any of the following: physical abuse, held against will, forced to pay money they did not owe, threatened with violence/deportation/imprisonment, or imprisoned. Occupational hazards were measured both as presence of any (yes/no) and total number of hazards that TFWs were exposed to at least once a month as part of their work (extreme heat, extreme sun exposure, working at heights >3 stories, breathing vapors/gas/dust/fumes, toxic chemicals, human or animal waste/biohazards, risk of losing/crushing body part, live electrical wires/transformers, explosives, heavy objects falling from above). We collected information on receipt of news and information about both Bangladesh and the host country by asking how often respondents follow the news in each location and the frequency of contact with their spouses. Finally, approval of the Bangladeshi and host country’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic was asked of all participants regardless of current location and dichotomized into strong approval versus somewhat approve or disapprove.

Analysis

After describing the univariate distribution for all variables, we conducted bivariate analysis of vaccine hesitancy in terms of all independent variables using chi-square tests of differences in proportions, t-tests of differences in means, and unadjusted logistic regression models. In developing multivariate models, we drew on predictors of vaccine hesitancy from the WHO BeSD Model, the results of bivariate analyses and multivariate models of each predictor category (see for categories) and model fit statistics included the Stata command “linktest” to detect specification errors in logistic regression ().Citation24–26 We tested categories of predictors that represent different hypotheses about vaccine hesitancy such as whether greater immigration-related vulnerability would predict greater vaccine hesitancy. Using multivariate logistic regression, we describe predictors of hesitancy and address covariation in terms of demographics, immigration-related characteristics, COVID-19 comorbidity, threat perception and protective behavior, COVID-19 exposure, and news sources. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15.

Table 1. Characteristics of TFWs from Bangladesh

Table 2. Vaccine hesitancy for TFWs from Bangladesh currently-abroad

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Systemic Issues

This all-male sample is predominantly married (92%) with school-age children at home (66%). The mean age is 41 and most of the men (57%) have 5–9 years of education (). The proportion who had returned to Bangladesh remained steady over the 5 months of data collection ranging from 18% at baseline to 23% in the fifth month of data collection (January/February 2021) with approximately 10% of those returnees going back abroad each month. Respondents’ host countries included Saudi Arabia (32%), United Arab Emirates (UAE) (14%), other GCC states (Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait) (21%), Singapore/Malaysia (23%), Europe/N. America (4%) and other countries (7%). The currently undocumented population ranged from 11% at baseline to 15% four months later, but was not statistically different across the 5 months of data collection. Deportation fear was greater earlier in the pandemic with up to 35% of respondents being somewhat or very afraid of being deported or detained in September/October 2020, which dropped to 14% in January/February 2021. In September/October 2020, 76% of TFWs were sending home fewer remittances than before the pandemic or none at all. This proportion declined significantly over the subsequent four months to less than half (43%) of TFWs sending fewer or no remittances home compared to the prior 30-day period.

What People Think & Feel

In spite of the overall good health of migrants, many had underlying health conditions that can increase the severity of COVID-19: 24% had at least one CDC-identified risk factor. Overall, 56% of respondents perceived COVID-19 as a high threat to themselves and 75% as a threat to their families, but this consistently decreased over time from 81% to 93% at its peak in September 2020 to 31% and 40% in January 2021. Most TFWs practice regular social distancing and masking with 89.5% reporting at least some regular protective behaviors overall and 82% still engaging in these practices in January/February 2021.

Employment Environment

TFWs often live in dormitory-style housing units and crowded housing (five or more people sharing a bedroom) was a risk factor for 28% of all TFWs. Cumulatively, 33% report someone testing or suspected COVID-19 positive in their worksite or home (worksite only 19%; home only 22%) ().

Vaccination

As of early February 2021, 25% of respondents were vaccine hesitant, a slight increase from 17% in late December/early January. Common stated reasons for hesitancy were fear of unpleasant side effects and not feeling at risk for COVID-19. Wanting more people to have taken the vaccine first and wanting more information were the next most common reasons. Overall, 44% of respondents had concerns about vaccine side effects regardless of their reported vaccine hesitancy. Most respondents did not have a vaccine product preference (74%), while 19% preferred vaccines from US or Europe. The vast majority of TFWs (96%) strongly approved of their host country’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic with no differences between TFWs who were currently abroad and those who had recently returned to Bangladesh. Conversely, only 33% of all TFWs strongly approved of the Bangladeshi government’s handling of the pandemic with stark differences between those who were in Bangladesh at the time of the survey (52%) and those who were abroad (28%).

Bivariate Analyses

There was no difference in the proportion of vaccine hesitancy between TFWs who had returned to Bangladesh and those who were still abroad (25%). Subsequent results are reported for the subset of TFWs who were abroad during January/February 2021 (n = 253), the latest month of data collection at the time of writing. Bivariate analysis revealed no significant differences in vaccine hesitancy across age groups or between those who did or not have risk factors for severe COVID-19, but differences emerged across education levels, location, visa status, worry about side effects, COVID-19 threat perception, as well as occupational and housing exposures.

Systemic Issues

The highest percentages of hesitancy (54%) were in Europe and North America (n = 15) with the lowest (14%) in Singapore and Malaysia (n = 81). In the Gulf States (n = 223), vaccine hesitancy was 26% or 27% (). Undocumented TFWs (n = 41) had higher levels of vaccine hesitancy (41%) compared to those with valid visas (n = 218) (22%, p = .009) (). Unadjusted logistic regression models of vaccine hesitancy suggested that host country, education, immigration factors, health and well-being, threat perception and exposure may all be important factors in determining hesitancy (). Compared to respondents living in Singapore or Malaysia, TFWs living in all other countries had higher odds of being vaccine hesitant. Respondents in Saudi Arabia, UAE and in the GCC states of Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait had between 3.4 and 5.4 times higher odds of being vaccine hesitant than those in Singapore and Malaysia (). Measures of immigrant integration into the host country such as visa status, language acquisition, and duration of migration all indicate that increases in integration are associated with less vaccine hesitancy.

What People Think & Feel

Hesitancy was significantly lower among those with high compared to low COVID-19 threat perception (17% versus 29%, p = .021). Hesitancy was much lower among those who were not concerned about side effects versus those who were very concerned (15% versus 63%, p < .001).

While the presence of risk factors was not associated with vaccine hesitancy, those with worse self-rated health had 3.24 higher odds (95% CI: 1.305–8.067) of being hesitant. Higher COVID-19 threat perception (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.222–0.833), and regular mask wearing and/or social distancing (OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.083–1.066) are all associated with lower levels of hesitancy.

Social Processes & Employment Environment

TFWs who experienced risk exposures through crowded housing (OR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.295–1.061), COVID-19 cases in housing (OR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.222–0.986) and occupational hazards (OR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.245–0.911) had lower odds of being vaccine hesitant compared to their fellow TFWs who did not experience employment-based exposures. Social processes such as communication with family back home did not predict vaccine hesitancy, although individuals who were more lonely were less slightly less likely to be vaccine hesitant (OR:0.92; 95% CI: 0.850–0.999).

Multivariate Analyses

Multivariate logistic regression models of vaccine hesitancy include all factors shown to be significant in bivariate analyses (Model I, ). Additionally, we report results from a multivariate model that includes representative factors from each of the three domains (Systemic Issues, What people think and feel, Social Processes and Employment Environment) and six categories: demographics, immigration, health, threat perception and risk mitigation, risk exposures, and information and communication from our conceptual model (Model II, ). Multivariate analyses confirm that immigration-related factors and threat perception, both of the COVID-19 virus and the side effects from vaccines, are the strongest predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for TFWs from Bangladesh.

Systemic Issues

Adjusted estimates show that undocumented migrants were significantly more likely to be vaccine hesitant (Model II AOR: 3.50; 95% CI: 1.372–8.942). The predicted probability of hesitancy for an undocumented TFW was 0.405, while the predicted probability for those with valid visas was 0.207 (p < .01). While not statistically significant, language acquisition demonstrated similar patterns, with more integration being associated with lower odds of vaccine hesitancy (Model II AOR: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.216–1.212) ().

What People Think & Feel

Being worried or very worried about getting COVID-19 was significantly associated with lower odds of vaccine hesitancy (Model II AOR: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.104–0.597). The predicted probability of being hesitant for TFWs who were worried about getting COVID-19 was 0.129 compared to 0.305 (p < .01) for those were not worried, all else equal.

Discussion

TFWs are at heightened risk for COVID-19 as well as the negative economic and social consequences of the global pandemic response. Vaccinating this population could not only reduce burdens on millions of foreign workers, but would also benefit host countries given the proportion of TFWs who make up the workforce. Bangladesh and other sending countries stand to benefit from widespread vaccination of their citizens abroad given the reliance on remittances and prior outbreaks caused by repatriation.Citation3,Citation4 Our study confirms relatively low levels of vaccine hesitancy among this population of TFWs (25%), particularly when compared to prior studies of the host-country native populations.Citation14,Citation19 However, important structural barriers tied to immigrant vulnerabilities exist: undocumented and unhealthy migrants have higher prevalence of hesitancy and greater fear of vaccine side effects. Effectively reaching TFWs with vaccine access and messaging requires intersectoral cooperation and coordination to address systemic issues. Due to their reliance on TFWs, the health, immigration, labor, and travel sectors have a responsibility to ensure that this population is protected by safe and effective vaccines.

Confirming hypothesis one, regional differences in hesitancy emerged that generally aligned with other work on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy including that higher COVID-19 presence regionally does not necessarily lead to more vaccine acceptance. Exposure at the micro-level through housing and worksite exposures had some effect (reduced prevalence of hesitancy), but did not fully explain the variation in hesitancy. Additionally, we reported higher hesitancy among TFWs in North America and Europe compared to the GCC countries, which was distinct from previous studies that showed the highest prevalence in the GCC.Citation13 Hesitancy did not appear to be driven by a lack of vaccine availability, given the increases in hesitancy as rollout progressed, but could be related to how the health system reaches vulnerable foreign nationals. This points to the importance of considering TFWs in the procurement and allocation of vaccines and the accompanying messaging.Citation6

The migrants in this study were relatively healthy, as is the case with most TFWs, despite many having risk factors for COVID-19 such as smoking and obesity, and also facing occupational abuse and hazards.Citation27 However, vulnerability to severe COVID-19 and the risks posed by hazardous or abusive work environments were not associated with any significant variation in hesitancy. TFWs with risk factors or health concerns had increased worry about the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine. Accordingly, hesitancy in this population may be driven more by fear of vaccine side effects related to their health conditions than by threat of the virus. Targeted messaging educating migrants about the significant health risks of COVID-19 infection, especially for those with existing comorbidities, relative to the low risk of serious vaccine side effects, is thus needed.Citation28 While they were not significant factors in predicting vaccine hesitancy, almost half of TFWs followed the news everyday, over 96% trusted their host country’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, and married respondents had multiple daily phone calls with their spouses in Bangladesh. Accordingly, these are potential pathways for reaching TFWs with vaccine information.

In strong support of our second hypothesis, results showed that the systemic issues like migration-related vulnerabilities associated with being undocumented lead to vaccine hesitancy. In testing hypothesis three, we find that typical measures of immigrant integration (duration abroad and language acquisition) demonstrated that assimilation of local norms does not necessarily apply in terms of vaccine hesitancy. However, these results were not statistically significant and further work is needed to test how the complex relationships between integration and destination impact vaccine attitudes. Referring to the BeSD model (), these findings confirm that vaccine hesitancy is associated with system-level factors that are not addressed through messaging targeted at individual beliefs and behavior. Structural interventions that address existing issues within the immigration system are not only important for economic and physical security, but also population health.

There were several limitations to this study. Due to the cross-sectional design, we are unable to make causal claims about the determinants of vaccine hesitancy. We had an all-male sample so did not capture sex differences in hesitancy which can be an important factor in targeting interventions.Citation21 Given that immigration-related characteristics were significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy, it is important to consider the context of migration for this sample in interpretation of the results. For example, our sample consists of a relatively mature migration flow; migrants were older (mean age of 41) and experienced (mean 12 years abroad) and come from a community with a long history of out-migration. Additionally, the sample included only a small number of TFWs in North America and Europe as the primary destinations for Bangladeshi migrants are the GCC countries, Singapore and Malaysia. This study does not include a direct measure of the source of health information and what sources are most trusted. While we do include indirect measures of communication and information receipt, these do not adequately capture health information, an important aspect of understanding vaccine hesitancy. Finally, this descriptive study was designed before the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines. In spite of these limitations, our findings point to recommendations for ensuring widespread uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine for foreign workers from Bangladesh.

Conclusions and Implications

Results reveal low vaccine hesitancy among TFWs from Bangladesh with differences in location, undocumented status, COVID-19 threat perception, and level of worry about side effects. There could be relatively high returns for targeting vaccine access and distribution to TFWs because of their high levels of vaccine acceptance.

Coordination between the host country health and immigration systems, which are directly tied to the economic and labor sectors, are key in addressing health crises. In vaccine distribution efforts, health systems must consider, and arguably, prioritize, TFWs in order to suppress transmission and, potentially, reach herd immunity. Success or failure of health system interventions such as vaccination campaigns can be tied to successes and failures in other systems. TFWs have unique needs and vulnerabilities associated with their employment, visa status, travel restrictions, and the interconnectedness of their health, livelihoods, and ability to legally work and host countries have an obligation to ensure effective and equitable vaccine distribution to all who reside within their borders. On a global scale, efforts such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) highlight the interconnectedness of systems and the importance of public participation to ensure health systems can achieve their mission of improving the health of populations. Applying these principles and those of the World Health Organization’s program on Financing Common Goods for Health can help structure the multisectoral response neededCitation29 to leverage the relatively high vaccine acceptance of TFWs and address the structural vulnerabilities that lead to hesitancy in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and contributions of icddr,b and would also like to thank the work of our fieldwork staff, especially Ferdousi Aktar.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Khan A, Harroff-Tavel H. Reforming the kafala: challenges and opportunities in moving forward. Asian Pac MigrJ.2011;20(3–4):1–11.doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681102000303.

- Sönmez S, Apostolopoulos Y, Tran D, Rentrope S. Human rights and health disparities for migrant workers in the uae. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(2):E17–35.

- Barker N, Davis Ca, López-Peña P, Mitchell H, Mobarak AM, Naguib K, Reimão ME, Shenoy A, Vernot C. Migration and the labour market impacts of COVID-19. Migration and the Labour Market Impacts of COVID-19: WIDER Working Paper. 2020.

- Karim MR, Islam MT, Talukder B. COVID-19’s impacts on migrant workers from Bangladesh: in search of policy intervention. World Dev. 2020;136:105123–105123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105123.

- Jamil R, Dutta U. Centering the margins: the precarity of bangladeshi low-income migrant workers during the time of COVID-19. Am Behav Sci. 2021;65(10):1384–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211000397.

- Yadav P. Health product supply chains in developing countries: diagnosis of the root causes of underperformance and an agenda for reform. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1(2):142–54.doi:https://doi.org/10.4161/23288604.2014.968005.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger JA. Vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.24657.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine.2014;32(19):2150–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- World Health Organization. Report of the sage working group on vaccine hesitancy. 2014.

- Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of who/unicef joint reporting form data-2015–2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3861–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063.

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020160.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Paul E,Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccinesandintentionto vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health-Europe. 2021;1:100012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

- Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, Karukivi M, Lindfelt M, Antfolk J. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif. 2021;172:110590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590.

- Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, Scacco A, McMurry N, Voors M, Syunyaev G, Malik AA, Aboutajdine S, Adeojo O, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1385–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y.

- Olagoke AA, Olagoke OO, Hughes AM. Intention to vaccinate against the novel 2019 coronavirus disease: the role of health locus of control and religiosity. J Relig Health. 2021;60(1):65–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01090-9.

- Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S276771.

- Alabdulla M, Reagu SM, Al-Khal A, Elzain M, Jones RM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: a national cross-sectional survey of a migrant-majority population. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15(3):361–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12847.

- Ali M, Hossain A. What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh?: A cross-sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e050303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021.-050303.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine information for people with certain medical conditions. Atlanta. Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020.

- Radloff LS. The ces-d scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618760521.

- World Health Organization. WHO SAGE roadmap for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/2019-nCoV/Vaccines/SAGE/Prioritization/2021.1

- World Health Organization. Data for action: achieving high uptake of COVID-19 vaccines: gathering and using data on the behavioural and social drivers of vaccination. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccination/demand_planning/2021.2.

- Kuhn R, Barham T, Razzaque A, Turner P. Health and well-being of male international migrants and non-migrants in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional follow-up study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(3):Article e1003081. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003081.

- Gee J, Marquez P, Su J, et al. First month of COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring—United States, December 14, 2020–January 13, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021:70:283–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7008e3

- Sparkes SP, Kutzin J, Earle AJ. Financing common goods for health: a country agenda. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):322–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1659126.