Abstract

In Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger, the policy to remove user fees for primary care was carried out through significant adjustments in public financial management (PFM). The paper analyzes the PFM adjustments by stage of the budget cycle and describes their importance for health financing. The three countries shifted from input-based to program-based allocation for primary care facility compensation, allowed service providers autonomy to access and manage the funds, and established budget performance monitoring frameworks related to outputs. These PFM changes, in turn, enabled key improvements in health financing, namely, more direct funding of primary care facilities from general budget revenue, and payments to those service providers based on outputs and drawn from noncontributory entitlements. The paper draws on these experiences to provide key lessons on the PFM enabling conditions needed to expand health coverage through public financing mechanisms.

Introduction

Study Background

User Fee Policies

In 1987, African health ministers launched the Bamako Initiative, which prompted changes to two aspects of primary care financing in most francophone African countries.Citation1,Citation2 First, countries introduced user fees, either by defining tariffs for individual services or opting for a flat rate (equivalent to one USD in Niger, for example) to cover primary care consultations and prescribed drugs. Second, health service providers were granted substantial flexibility to manage funds generated from receipt of these user fees, to support their facility operating costs.Citation3 These funds could be used to purchase drugs, pay utilities, hire temporary staff, and top-up salaries for civil servants.Citation4–6 While these funds covered only a small proportion of the cost of the facilities’ operations,Citation7 their flexibility made them an important source of income for primary care providers, in a context where the level, regularity of flow, and flexibility of general revenues allocated for health facilities all were constrained.Citation2,Citation3,Citation8 Nonetheless, there is ample evidence that these user fees have had detrimental consequences for the population, particularly the poor, as these fees have hindered their access to primary care and negatively affected financial protection.Citation9–11

Against this backdrop, starting in the early 2000s, many sub-Saharan African countries have removed user fees for targeted groups to increase access to primary care services and improve financial protection.Citation12–15 Burkina Faso, Burundi, and Niger were among the first countries to do so. In 2006, Burundi and Niger removed user fees at health centers and district hospitals for antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care for women, and curative care for children under five.Citation16–22 Burkina Faso exempted delivery and emergency obstetric care, and ten years later brought in similar exemptions at all levels of the health system for women and children.Citation23 Other categories of patient and types of service remained subject to fees.

Public Financial Management (PFM) System

During the implementation of the Bamako Initiative, supply-side budget funding supporting the operating costs of primary care facilities was generally limited in volume. Funds for these facilities, aside from staff costs covered by central budgets, often constituted less than 5% of public spending on health.Citation24 This public funding was often linked to rigid line-item controls, and was commonly delivered in kind (e.g., in the form of drugs and medical equipment) to subnational levels (e.g., health districts) for onward distribution to service providers. These budgets were formulated and executed by inputs, the prevailing practice in most sub-Saharan African countries at the time.Citation25 Budget provisions were costed by input (e.g., drugs, equipment, staff) and presented by disaggregated object of expenditure (e.g., fuel for primary care facilities, dialysis equipment for district hospitals, utilities, and office supplies). A line-item ceiling was generally established during the budget allocation process to ensure that budget holders did not spend beyond their caps.Citation25,Citation26 This rigid budget and disbursement structure generally hindered effective use of budget funds at the front lines, making user fee revenues desirable for managers given their more flexible nature.Citation3,Citation8

Once governments decided to remove user fees, they could choose between several approaches to compensate facilities for the loss of revenue: (a) providing no financial compensation, leaving free health care as a mere declarationCitation27; (b) providing a budget under existing budget rules (e.g., through input-based allocation, via districts)Citation28; or (c) combining financial compensation with changes in PFM so the new funds could be allocated and used more flexibly. Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger chose the third approach.

In what ways were the PFM systems adjusted by the three countries in their respective transitions from user fees to free health care? This study describes how Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger reformed key PFM mechanisms to enable more flexible use of budget funds as part of their policies to remove user fees, a process which has not been well documented previously.

Methods

Overall Approach

A qualitative approach was used to identify and characterize the main changes in PFM and related regulations following the decision to remove certain user fees.Citation29 The study design involved in-depth case studies conducted in 2018–19 in Burkina Faso, Burundi, and Niger. The research approach followed a rigorous qualitative protocol, which involved: i) preliminary desk review; ii) study protocol development; iii) approval process from ministries of health; iv) in-depth interviews and group discussions; and v) analysis of thematic content (by stage of the budget cycle).

The desk review consisted of reviewing the literature, laws, regulations, and policy documents related to the removal of health service user fees and to PFM frameworks in the three countries. This step, which sought to identify the changes in regulation and in laws that had taken place, found limited documentation on these. Consequently, interviews with planning and budgeting officials of health ministries were added, using semi-structured questions to clarify the budgeting and spending processes involved in compensating health facilities for their loss of revenues from user fees and to capture any changes from previous practices. After review and approval of the study protocol by the ministries of health, consultants and World Health Organization (WHO) country offices helped to conduct a total of 23 interviews with government officials. Consent of interviewees was obtained, and interviewees were guaranteed anonymity. The content of the interviews was analyzed using a thematic content approach.Citation29 In each of the three countries, two local consultants grouped study inputs by stage of the budget cycle and summarized key findings in a country report. In Niger, two group discussions were also organized with representatives of the health and finance ministries for their perspectives on the PFM changes. Further in-country consultations were organized in all three countries with development partners and subject-matter experts to review key findings and identify additional secondary sources. Professionals from various levels of the WHO collaborated with the contributors in the three countries to produce this synthesis paper.

Key PFM Definitions

This paper uses the standard PFM taxonomy to refer to the main phases of the budget cycle: budget development, execution, and oversight.Citation30,Citation31 The budget development process refers to how domestic resources are prioritized, allocated, and presented in budget documents. As part of that development process, the term “formulation” refers to the organization of a government budget based on standard classifications. Historically, countries have formulated their budgets predominantly by economic classification (e.g., salaries, medicines, utilities, etc.), resulting in an input-based budget. Increasingly, countries are presenting their budgets in the form of budget programs: a program aggregates inputs into a consolidated envelope that contributes to a common set of policy goals and outputs (e.g., access to primary care services). Program-based budgeting reforms try to remedy some of the deficiencies associated with input-based budgets by shifting the focus from inputs to outputs, thereby empowering budget holders with more managerial control over programmatic envelopes which are tied to targets.Citation32,Citation33

Budget execution refers to when and how allocations are disbursed and spent. This is closely linked to how services are purchased from providers and how funds flow to health facilities (i.e., provider payment),Citation34 a key function of health financing policy. Country standard operating procedures provide detailed information on key steps and roles in the execution chain.Citation35 After adoption of a given budget, most countries follow a four- to five-step process to implement the budgeted expenditures. Typically, the process involves authorization and apportionment (after budget approval, sectoral ministries receive authorization to spend); commitment (expenditure decisions are made by sectoral ministries), acquisition, and verification (once goods and services are delivered, there is a verification against initial order); and creating payment orders and making payments (upon receipt of payment order, bills are paid).

Budget oversight refers to how funds are accounted for, reported, and audited. Financial information systems can track expenditures according to budget allocations.Citation31 In systems where budgets are defined by inputs, reporting is also done by inputs, obscuring the link between spending and outputs. This final phase in the budget cycle generally involves independent agencies that audit accounts and report findings to the legislature, to inform future budget decisions.

Results

Change in Budget Development and Formulation

In Niger, the methods for formulating and estimating the size of the budget to support the implementation of free health care, starting in 2006, broke with historical input-based practice. Once user fees were removed, the quantity estimate was based on the previous year’s volume of free consultation and related services, while the price was a flat, bundled rate. The budget formulated the compensation mechanism as a lump-sum envelope, and not by line items. This revised approach follows the norms for program-based budgeting, providing more flexibility in the allocation of resources and aligning with a policy goal (increased access to primary care services) (see ).

Table 1. Summary of key findings

Burundi took a similar approach to budgeting for free services. In 2006, a temporary program-type line was introduced in the budget to channel funding to facilities. The line was defined as a lump sum and was estimated based on the expected volume and quality of services to be delivered. The rest of the Ministry of Health (MoH) budget, in keeping with the overall national budget, continued to be based on inputs. In 2010, this temporary budget line was combined with another funding source (mostly from on-budget from external grants) that provided performance-based grants to health service providers, resulting in a unified transfer modality for funding of facilities.Citation19 Since then, the merged compensation mechanism has been budgeted as an allocation topping-up the traditional input-based provisions that cover salaries and other inputs.

In Burkina Faso, the program-based budget in place since 2017 allowed for the inclusion of the free health care compensation as a lump-sum line.Citation36 The program structure included three tiers: program goals (headline), actions (where the budget sits), and activities (detailed presentation of interventions). Budget provisions for free health care were inserted at the level of “actions,” the second level in the program budget structure. This budget structure has facilitated a transition away from an input-based definition of the compensation envelope.

Change in Budget Execution and Oversight

The introduction of free health care policies in these three countries required changes to the release, control, and monitoring of a significant part of the health budget. Each country’s Ministry of Finance (MoF) opted for direct transfers to health facilities (primary care centers and district hospitals)—a funding channel that did not exist previously.

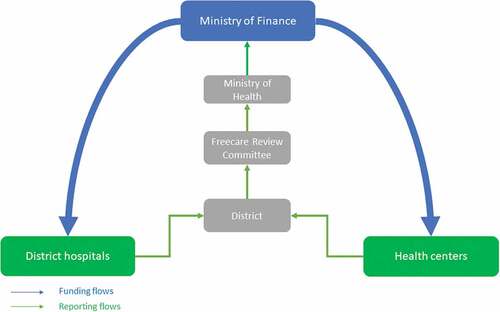

In Niger, for example, the budget provision was prospectively positioned in the budget for the entire fiscal year, and funds were released (i.e., providers were paid) via retrospective reimbursements to facilities on the basis of ex-post claims (see ).

Figure 1. Mapping disbursement and reporting flows for free health care compensation: example from Niger

In Burkina Faso and Burundi, the funds were deposited directly into the bank accounts of health facilities, which became de facto spending units. In Niger, funds initially transited through district bank accounts, with earmarking for specific facilities based on claims, as most facilities did not have their own bank accounts. Starting in 2018, funds were made directly available to regional drug stores and allocated as cash imprest to health facilities for other operating costs. In all three countries, facilities were given the flexibility to use the budgetary envelope to cover operating costs according to their needs, with no caps or restrictions on utilization. Funds received through the compensation mechanism were no longer controlled on the use of specific line items. Instead, facilities were financially incentivized to deliver on targeted outputs including volume and, in Burundi, indicators of the quality of services.Citation19 Providers there and in Burkina Faso received funds according to their ex-post monthly claims. In Niger, this happened quarterly.

The program-type line in Niger’s budget was associated with output targets for service performance that were included in the budget’s performance monitoring framework. This approach established a novel connection within the budget framework between what was allocated and what was deemed to be achieved. One could know how much was spent for free health care and how many and which types of services were delivered with this expense within a fiscal year. Burkina Faso took a similar approach in introducing a performance monitoring framework for its program-based budget,Citation36 including performance indicators for the free health care mechanism.

Discussion

The shifts in PFM practices observed include changes to the processes for budget development and formulation and to the mechanism for budget execution; increased financial flexibility for service providers; and accountability based on outputs. These shifts have enabled the three countries to maintain the incentive for productivity and provide flexible funds to facility managers as part of the national effort to deliver on the political commitment to make health services free of charge for users. PFM reforms such as those introduced in the countries reviewed here altered the “engineering” of health finance, potentially enabling progress toward coverage expansion. maps the PFM adjustments onto the main health financing functions, showing the connection between those adjustments and health financing reforms (see ) that can be conducive to expanding health coverage, most notably in terms of purchasing, benefit design, and financial management autonomy for service providers.Citation37

Table 2. Connections between PFM adjustments and financing functions that are supportive of expanding health service coverage

The development and formulation of the fee-compensation budget as a program-based envelope rather than by economic classification allowed providers to be compensated for outputs and to manage the funds as needed without line-item constraints. Direct disbursement of funds from Treasury gave primary care facilities timely and direct access to these flexible resources to meet their operating costs. And the monitoring of expenditure by service outputs rather than inputs shifted accountability from control of inputs to performance of service outputs. These changes in PFM made it possible for primary care facilities to do more with general budget funds that otherwise would only have provided them with additional revenues. The specific changes put in place in the effort to remove user fees in Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger managed to maintain the quantity of revenues raised and their quality, in the sense of flexibility, as well as the incentives for provider productivity.

In broader perspective, while introduced to support the free health care policies, the changes in PFM also provide a foundation for longer-term reforms of health financing to enable progress toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC).Citation38 By enabling implementation of a package of measures including general budget revenue funding, output-based payments, and noncontributory entitlements, these PFM changes offer a more effective and equitable path toward UHC than contributory health insurance, particularly in lower-income countries with low levels of formal employment.Citation39 The evidence is strong that in low- and middle-income countries, health coverage can be expanded most effectively through noncontributory entitlement funded from general budget revenues.Citation27,Citation37,Citation40 But more money alone does not enable progress if the funds cannot be matched to priority services and populations, and if facility managers do not have authority over their use. In light of the evidence put forward in this paper, it is understood that PFM adjustments can indeed enable this change.

Study Limitations

This paper’s focus was on studying the underlying PFM processes, mechanisms, and adjustments that accompanied the removal of user fees and on discussing why and how those changes mattered from a health financing perspective. Hence, the concern was with implementation mechanisms rather than the ultimate effects of the changes to date. It did not aim to assess the overall effects of user fee removal on health or health financing-related outputs, including utilization of health facilities, or to establish a causal relationship between those changes and the outputs. It has yet to be demonstrated conclusively that the aforementioned shifts in PFM, and the changes in health financing functions enabled by the former, have resulted in progress toward UHC in the three countries studied here. Although preliminary findings show a positive effect of user fee removal on access to primary care in Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation41 further research is needed to assess the effects of the policy change on other outputs, including on financial protection in the longer term.

Conclusion

In Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger, the initiation of free health care policies was supported by substantial changes to the three stages of the domestic PFM system’s budget cycle, allowing facilities to be compensated for the loss of flexible revenues. In the first stage, development and formulation, budgets that typically had been planned and formulated through inputs now incorporated provisions to compensate primary care providers based on outputs. The second stage, execution, included adjustments to spending modalities through the introduction of a direct transfer mechanism to facilities, flexible rules for resource use, and a shift to ex-post control. The direct transfer of funds from the Treasury to facilities represented a major change, both for health facility financing and for PFM more broadly, empowering service providers by enabling flexible use of these budget funds. In the third stage, monitoring, practices had to be refined to allow tracking systems to link expenditures and outputs. Taken together, these changes enabled implementation of output-based payments from general revenues and allowed provider autonomy over the use of funds, measures that the countries deemed necessary to turn the promise of free health policies into practice. Looking ahead, such adjustments provide an opportunity to foster a more supportive environment for progress toward UHC in the study countries, by mainstreaming the use of output-based budgeting and spending beyond just primary care. Aligning PFM and health financing efforts may also be an important consideration for other low- and-middle income countries where the reach of contributory entitlements is limited due to low levels of formal employment. Compensating health facilities directly for specific outputs, from general budget revenues, is a practical way forward.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ministries of health of Burkina Faso, Burundi and Niger for supporting the research process, data collection and overall analysis. The authors acknowledge the input on an earlier version of this paper by Bruno Meessen (WHO), Inke Mathauer (WHO), Fahdi Dkhimi (WHO), Sophie Witter (Queen Margaret University), Maria Bertone (Queen Margaret University), and Saran Branchi (The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hardon A. Ten best readings in … the Bamako initiative. Health Policy Plan. 1990;5(2):186–8. doi:10.1093/heapol/5.2.186.

- World Bank. Financing health services in developing countries: an agenda for reform. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 1987. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-0900-1.

- Nyonator F, Kutzin J. Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(4):329–41. doi:10.1093/heapol/14.4.329.

- Bertone MP, Witter S. The complex remuneration of human resources for health in low income settings: policy implications and a research agenda for designing effective financial incentives. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):62. doi:10.1186/s12960-015-0058-7.pdf.pdf.

- Mathauer I, Mathivet B, Kutzin J. In: Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2017. ‘Free health care‘ policies: opportunities and risks for moving towards UHC. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. Health financing policy brief no. 2 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-HGF-PolicyBrief-17.2

- Nunan M, Duke T. Effectiveness of pharmacy interventions in improving availability of essential medicines at the primary healthcare level. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(5):647–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02748.x.

- Mc Pake B, Hanson K, Mills A. Community financing of health care in Africa: an evaluation of the Bamako Initiative. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(11). doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90381-d.

- Litvack JI, Bodart C. User fees plus quality equals improved access to health care: results of a field experiment in Cameroon. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(3):369–83. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90267-8.

- Creese AL. User charges for health care: a review of recent experience. Health Policy Plan. 1991;6(4):309–19. doi:10.1093/heapol/6.4.309.

- Gilson L. The lessons of user fee experience in Africa. Health Policy Plan. 1997;12(3):273–85. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.heapol.a018882.

- Gilson L, Russell S, Buse K. The political economy of user fees with targeting: developing equitable health financing policy. J Int Dev. 1995;7(3):369–401. doi:10.1002/jid.3380070305.

- Yates R. 2006. International experiences in removing user fees for health services — implications for Mozambique. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. In London (UK): DFID Health Resource Centre; https://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/International-Experiences-in-Removing-User-Fees-for-Health-Services.pdf

- Lagarde M, Palmer N. The impact of user fees on access to health services in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;13(4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009094.

- Ridde V, Morestin F. A scoping review of the literature on the abolition of user fees in health care services in Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(1):1–11. doi:10.1093/heapol/czq021.

- McPake B, Brikci N, Cometto G, Schmidt A, Araujo E. Removing user fees: learning from international experience to support the process. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 2):ii104–ii117. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr064.

- Meessen B, Hercot D, Noirhomme M, Ridde V, Tibouti A, Tashobya CK, Gilson L. Removing user fees in the health sector: a review of policy processes in six sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 2):ii16–ii29. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr062.

- Hatt LE, Makinen M, Madhavan S, Conlon CM. Effects of user fee exemptions on the provision and use of maternal health services: a review of literature. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013; 31(4 Suppl 2): S67–S80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4021702/

- Ridde V. From institutionalization of user fees to their abolition in West Africa: a story of pilot projects and public policies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(S6). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-15-S3-S6.

- Basenya O, Nimpagaritse M, Busogoro F, Ndayishimiye J, Nkunzimana C, Ntahimpereye G, Bossuyt M, Ndereye J, Ntakarutimana L. Le financement basé sur la performance comme stratégie pour améliorer la mise en œuvre de la gratuité des soins: premières leçons de l’expérience du Burundi. 2011. PBF CoP Working Paper No: 5. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. http://www.healthfinancingafrica.org/uploads/8/0/8/8/8088846/wp5.pdf.

- Lagarde M, Barroy H, Palmer N. Assessing the effects of removing user fees in Zambia and Niger. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(1):30–36. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010166.

- Nimpagaritse M, Bertone MP. The sudden removal of user fees: the perspective of a frontline manager in Burundi. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 2):ii63–ii71. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr061.

- Ridde V, Diarra A. A process evaluation of user fees abolition for pregnant women and children under five years in two districts in Niger (West Africa). BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):89. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-89.

- Ridde V, Bicaba A. Revue des politiques d’exemption/subvention du paiement au Burkina Faso: la stratégie de subvention des soins obstétricaux et néonataux d’urgence. Antwerp (Belgium): Institute of Tropical Medicine; 2009. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. http://www.equitesante.org/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/lib/request/request.dl.php?api_user_id=1627688&dlkey=EZR2C4FQ&content_type=application/pdf.

- Gauthier B, Wane W. Leakage of public resources in the health sector: an empirical investigation of Chad. J Afr Econ. 2008;18(1):52–83. doi:10.1093/jae/ejn011.

- Barroy H, Kabaniha G, Boudreaux C, Cammack T, Bain N. Leveraging public financial management for better health in Africa: key bottlenecks and opportunities for reform. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019. Health Financing Working Paper No: 14. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-UHC-HGF-HFWorkingPaper-19.2

- Lienert I. A comparison between two public expenditure management systems in Africa. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2003. IMF Working Paper No: 03/2. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2003/wp0302.pdf.

- Kutzin J, Yip W, Cashin C. Alternative financing strategies for universal health coverage. In: Scheffler RM, editor. World scientific handbook of global health economics and public policy. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2016. p. 267–309. doi:10.1142/9789813140493_0005.

- Nabyonga Orem J, Mugisha F, Kirunga C, Macq J, Criel B. Abolition of user fees: the Uganda paradox. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(2 Suppl):ii41–51. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr065.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research, 4th ed. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2018.

- Potter BH, Diamond J. Guidelines for public expenditure management. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 1999. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/expend/index.htm.

- Allen R, Hemming R, Potter BH (2013): The international handbook of public financial management; [Accessed 2022 April 5]. https://www.springer.com/de/book/9780230300248

- Jacobs DF, Hélis J-L, Bouley D International Monetary Fund. 2009 Budget classification [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. doi:10.5089/9781462343478.005. Technical Notes and Manuals 9 6 https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF005/10622-9781462343478/10622-9781462343478/10622-9781462343478_A001.xml?redirect=true&redirect=true

- Barroy H, Dale E, Sparkes S, Kutzin J. Budget matters for health: key formulation and classification issues. In: Health financing policy brief no: 4. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2018 [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-HIS-HGF-PolicyBrief-18.4

- Mathauer I, Dale E, Meessen B. Strategic purchasing for universal health coverage: key policy issues and questions. A summary from expert and practitioners’ discussions. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2017. Health Financing Working Paper No: 8. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259423.

- Tommasi D. Budget Execution. In: Shah A, editor. Budgeting and budgetary institutions. Washington (DC): The World Bank. 2007. p. 279–322. Public Sector Governance and Accountability Series doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-6939-5.

- Barroy H, André F, Nitiema A. In Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2018 Transition to programme budgeting in health in Burkina Faso: status of the reform and preliminary lessons for health financing. [Accessed Apr 5 2022]. Health financing case study no. 11 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UHC-HGF-HEF-CaseStudy-18.11

- Jowett M, Kutzin J, Kwon S, Hsu J, Sallaku J, Solano JG. In: . Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2020 Assessing country health financing systems: the health financing progress matrix [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. Health financing guidance no. 8 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017405

- Witter S. Service- and population-based exemptions: are these the way forward for equity and efficiency in health financing in low-income countries? Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2009;21:251–88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19791706/

- Yazbeck AS, Savedoff WD, Hsiao WC, Kutzin J, Soucat A, Tandon A, Wagstaff A, Chi-Man Yip W. The case against labor-tax-financed social health insurance for low- and low-middle-income countries. Health Aff. 2020;39(5):892–97. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00874.

- Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements. Health policy. New York 2001;56(3):171–204. doi:10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00149-4.

- Falisse J-B, Ndayishimiye J, Kamenyero V, Bossuyt M. Performance-based financing in the context of selective free health-care: an evaluation of its effects on the use of primary health-care services in Burundi using routine data. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(10):1251–60. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu132.