ABSTRACT

Several purchasing arrangements coexist in Uganda, creating opportunities for synergy but also leading to conflicting incentives and inefficiencies in resource allocation and purchasing functions. This paper analyzes the key health care purchasing functions in Uganda and the implications of the various purchasing arrangements for universal health coverage (UHC). The data for this paper were collected through a document review and stakeholder dialogue. The analysis was guided by the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework created by the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC) and its technical partners. Uganda has a minimum health care package that targets the main causes of morbidity and mortality as well as specific vulnerable groups. However, provision of the package is patchy, largely due to inadequate domestic financing and duplication of services funded by development partners. There is selective contracting with private-sector providers. Facilities receive direct funding from both the government budget and development partners. Unlike government-budget funding, payment from output-based donor-funded projects and performance-based financing (PBF) projects is linked to service quality and has specified conditions for use. Specification of UHC targets is still nascent and evolving in Uganda. Expansion of service coverage in Uganda can be achieved through enhanced resource pooling and harmonization of government and donor priorities. Greater provider autonomy, better work planning, direct facility funding, and provision of flexible funds to service providers are essential elements in the delivery of high-quality services that meet local needs and Uganda’s UHC aspirations.

Introduction

As low- and middle-income countries embrace the ambitious goal of achieving universal health coverage (UHC), the issues of inadequate domestic financing, out-of-pocket payments, financial sustainability, and value for money in health spending have been catapulted to the top of policy and research agendas.Citation1,Citation2 Strategic purchasing of health services is considered one tool that can help secure more value for money and increase efficiency in allocating funds and paying for health services, especially in the context of defined UHC goals.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4 This has led to a call for countries to use strategic purchasing rather than passive purchasing approaches, as well as increased focus on strategic purchasing from national and global-level players that are supporting countries that have initiated health financing reforms.Citation5,Citation6

Health purchasing is defined most generally as the allocation of pooled funds on behalf of the population to the providers of health services.Citation7 For purchasing to be considered strategic, it must include an active process of allocating funds based on available information about health provider performance and population health needs, with the ultimate aim of increasing efficiency, equitable distribution of resources, and cost containment.Citation1 Strategic purchasing decisions include: 1) what services and medicines to buy with available funds, 2) from which providers to buy, 3) how and how much to pay those providers.Citation3

Successful implementation of these key components of strategic purchasing requires coordinated action and, in particular, interaction between purchasers and patients and between the government and purchasers.Citation4,Citation8 No blueprint for strategic purchasing can fit every context; each country must assess its capabilities and develop its own purchasing framework, policy design, and roadmap for moving from a more passive purchasing system to a more strategic one.Citation1,Citation8

While strategic purchasing processes will depend on the specific country context, the supporting policies and reforms should consider patient needs, improve organizational governance and stewardship, and create appropriate incentive regimes. These changes can ultimately contribute to the efficient and equitable delivery of high-quality services that meet population needs, which is the ultimate aim of strategic purchasing.Citation4,Citation6,Citation8

Uganda has a mixed health care system, with public and private providers and a tiered primary health care (PHC) network connected by referral systems between basic and specialized services. Implementation of strategic purchasing in Uganda has been constrained by the challenges documented in other low- and middle-income countries. They include purchasing by multiple agencies, lack of clarity about the roles of different purchasers, inadequate legislation to support strategic purchasing, and high administrative costs. Other constraints include inadequate information for making strategic purchasing decisions, local prioritization challenges, poor patient engagement, and political concerns.Citation4,Citation9–11

Against this backdrop, we set out to map the implementation of strategic purchasing in Uganda by analyzing key purchasing arrangements and their implications for UHC. Our objective was to understand the constraints on more strategic purchasing and to identify options for making progress.

This analysis covers the three main financing arrangements in the country: 1) use of government budget financing to purchase services at the national and local levels; 2) performance-based financing (PBF), with a focus on the World Bank–funded Uganda Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health Services Improvement Project (URMCHIP); and 3) other donor/project-based financing.

Uganda’s Health Financing and Service Delivery Landscape

Funding for health in Uganda is inadequate for achieving the country’s stated UHC goals. The 2016 National Health Accounts (NHA) report estimated that per capita health spending was about 51 USD, nearly 40% short of the target for providing the Uganda National Minimum Health Care Package (UNMHCP).Citation12 This declined to 37 USD per capita in the most recent NHA.Citation13 Total health expenditure (THE) as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) was 4.3%, while government health expenditure as a share of GDP was a mere 0.7% in 2018/2019.Citation13 The NHA estimated that in 2018/19 private spending accounted for 39% of THE, development assistance for health accounted for 41.4%, and government spending accounted for only 17.2%. Private and community health insurance generally account for less than 2% of THE.Citation13

In terms of service provision, the system includes 6,937 providers, of which 45% are public, 40% are private for-profit providers, and 15% are private not-for-profit providers. The private providers tend to have more market power in urban areas and less in rural areas, which are often dominated by public facilities. Private providers are perceived to offer better quality services than public facilities.

Main Health Financing Mechanisms in Uganda

Like many low-income countries, Uganda has several concurrent financing systems for health services, each with their own purchasing arrangements. The primary financing mechanism is the government budget used to purchase a bundle of health inputs. Government budget resources generally flow from the central government to local governments and fall into two broad categories: conditional grants and nonconditional grants.Citation14 However, there is little room for discretionary allocation of resources because the national government makes conditional PHC grants to facilitate service delivery, mainly in the form of wage and nonwage grants.Citation14 The wage grant is for wages and salaries for civil servants, which are often directly deposited into individual civil servants’ bank accounts. Nonwage grants are mainly used for development and administrative functions such as supervision, utility costs, and outreach activities.Citation14

A notable change in Uganda’s financing landscape over the past two decades has been a progressive shift to PBF.Citation15 The PBF models that have emerged in Uganda are largely financed by donors, with many of them supplementing government budgets. The PBF payments are made to providers based on meeting an established set of outputs, in what is known as cash on delivery.Citation14 These initiatives include PBF projects funded and implemented by Enabel, Cordaid, and the World Bank.

A custom-designed national PBF framework was launched in 2017, following extensive consultation with stakeholders. The framework aims to align PBF implementation with the national and decentralized system of service delivery and associated institutional mandates.Citation15 In 2015, Uganda received funding from the Global Financing Facility Trust Fund and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency to implement PBF nationwide to expand access to an integrated service package for reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health. Project implementation has been guided by the national PBF framework, and the key purchasing functions have been distributed among various entities. As of 2021, the PBF program covered 136 of the country’s 145 districts.

A third type of health financing mechanism is donor-funded projects and schemes that provide health services to the population. Development assistance is channeled through both on-budget and off-budget mechanisms. Financing data show that development partners have increased off-budget support over time.Citation16,Citation17 This can be attributed to the need of donors to maintain direct control over the grants and purchasing decisions.Citation18 Key donors include the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, the European Union, Netherlands, Ireland, and others who finance various health care interventions in Uganda.

Methods

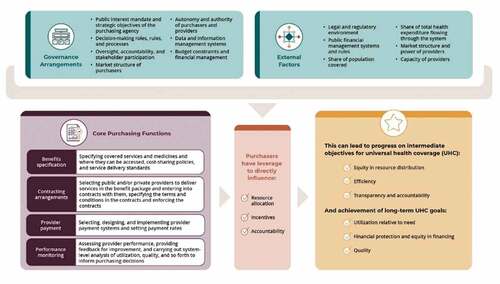

The study used a qualitative descriptive approach, applying the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework () developed by the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC).Citation19 We conducted the mapping exercise for the three main purchasing arrangements in Uganda—government budget financing, PBF, and donor-funded projects. For government budget financing, we considered the purchasing roles of both central government and local government and analyzed those roles as a single purchasing arrangement, because both receive allocations from the government budget and their expenditures are subject to public finance management rules. The main data collection method was document review, supplemented with stakeholder dialogue. Information was compiled in the Microsoft Excel–based tool developed by SPARC and analyzed by synthesizing available information on the purchasing arrangements and cross-checking against the strategic purchasing benchmarks.

Analytical Framework

Our analysis was guided by the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework, which builds on other, existing strategic purchasing frameworks.Citation19 The four key domains of the framework are: 1) the governance arrangements that provide oversight and accountability for purchasing arrangements, 2) the purchasing functions executed through the purchasing arrangements (benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring), 3) the external factors that influence the results of purchasing, and 4) the results and intermediate outcomes of the purchasing arrangements (such as access, coverage, quality, equity, and financial protection).

In this paper, we present findings on the second and fourth domains, taking into account the other domains.

Data Collection

We used a Microsoft Excel data collection tool designed by SPARC to collect and collate information describing the purchasing arrangements drawn from a document review and stakeholder dialogue. The documents reviewed included national and sector-level strategic documents, national guidelines on financing, recent evaluations of key sector interventions, project proposal documents, and published literature on health financing and public finance management. We accessed the documents mainly from the public domain, including the Ministry of Health (MOH) website, to complement the rich repository of sources in the Center for Health Policy and Systems Development.Citation20 After reading the full text of the selected documents, we entered summaries of relevant data extracted from the reviewed documents into the Excel tool.

We collected additional primary data through a dialogue meeting with an array of relevant stakeholders held in March 2020. The objective of the dialogue meeting was to explore opportunities for and obstacles to enhancing strategic purchasing in Uganda. The dialogue meeting was also prompted by a looming policy to adopt a national health insurance scheme in Uganda. A total of 26 stakeholders participated, including government officials and representatives from development partners, civil society organizations, the private sector, and academia. A presentation of the findings of the mapping exercise was followed by a plenary discussion of their implications.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the results of the document review, the mapping exercise, and the stakeholder dialogue reports thematically by the domains highlighted in the framework. We reached consensus through team meetings of all the authors: EEK, AS, RS, CM, FS, CC, AGM, and NO. We cross-checked the descriptive information on the purchasing arrangements for each health financing scheme against the strategic purchasing benchmarks to identify areas of progress and challenges for strategic purchasing in Uganda.

Results

This section presents our findings by key purchasing function.

Benefits Specification

The government, through its budget, strives to ensure access to a package of basic health services. The removal of cost sharing in public facilities in 2001 expanded entitlements to provide all Ugandans access to the health services under the UNMHCP at all public health facilities.Citation21 The UNMHCP has four areas of focus: maternal and child health, noncommunicable diseases, health promotive and preventive services, and communicable diseases.Citation22 Since 2001, services at public facilities have been expected to be free at the point of use, except in private wings of those facilities. The UNMHCP is said to be broad and all-inclusive, but it is beyond current government capacity to ensure sustained service provision and thereby falls short of achieving service coverage and financial risk protection goals.Citation23

In the project-based schemes, project fundholders are the main conduit for reaching beneficiaries. In a typical project model, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) with known clientele or service outlets (such as Uganda Catholic Medical Bureau or Marie Stopes) is selected to receive funds to benefit its clients and partnerships. Most projects focus on maternal and child health and communicable diseases such as malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis (TB), which together reportedly received about 65% of development assistance for health in Uganda.Citation24

The PBF purchasing arrangements mainly provide selected services from the UNMHCP,Citation25 primarily for maternal and child health and communicable diseases such as malaria. However, the available packages do not provide a full range of promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services. This has been mainly attributed to resource constraints under the government system and the fragmented nature of project-based schemes as well as the narrow focus of PBF schemes.

The package funded by the government budget is based on burden-of-disease studies and the cost-effectiveness of interventions. The PBF and project-based schemes generally focus on diseases and conditions that contribute to high morbidity and mortality.Citation26 In all three types of purchasing arrangements, the community is not directly consulted on the design of the benefit package. This lack of feedback and social accountability mechanisms undermines the responsiveness of service packages to beneficiary needs.

details the benefit package and target beneficiaries under the different purchasing arrangements, as well as the implications for UHC.

Table 1. Benefit packages, target beneficiaries, community engagement and implications for UHC.

Contracting Arrangements

The central and local governments have mandates to form service delivery partnerships and contract with private providers and other fundholders. The partnerships are governed by soft tools such as memorandums of understanding (MOUs) rather than explicit contracts. Public and private facilities are expected to provide the package of services prescribed under the UNMHCP to all Ugandans.Citation21 To strengthen the complementarity of roles, the government launched the National Policy on Public Private Partnership in Health (PPPH) in 2012.Citation27 Within the PPPH framework, subsidies are extended to well-organized and accredited private health providers, mostly providers affiliated with religious medical bureaus. These government subsidies are intended to mitigate the costs of services provided by private not-for-profit providers so they are more affordable to poorer households.Citation28 However, the overall financial burden to households remains high, reflected in the high share of out-of-pocket expenditure in total health spending (39% in 2018/19),Citation29 which includes payment for services accessed in both private and private not-for-profit facilities.

The market for PBF and donor-funded projects has been, until recently, dominated by private providers because they are generally more flexible and face fewer limitations on their autonomy to make managerial and financial decisions. They usually enter into explicit contracts with fundholders after a vetting, bidding, or accreditation process.Citation26

While the government goes to considerable effort to maintain quality control and ensure equitable distribution of services, mainly through regulation, health purchasing through the government budget financing is not explicitly linked to the quality of services provided by a facility.Citation30 PBF and donor-funded schemes, on the other hand, aim to link funding to the quality of services.Citation15 Providers who provide good-quality care are selected either through competitive calls for proposals or specific (project-based) criteria and through a PBF accreditation process.Citation26 Lack of accreditation under the government system may constrain the delivery of quality services.

elaborates on these findings.

Table 2. Contractual arrangements, quality considerations, and implications for UHC.

Provider Payment

Provider payment methods vary by purchasing arrangement. Government budget financing uses input-based methods to pay providers. Funds are released by the central government to local governments through conditional grants that stipulate what the money should be used for and nonconditional grants that are more flexible. Payments are made to local governments, and in some cases directly to health facilities or to health workers. The allocation formula for PHC grants considers, among others, the target population served, burden of disease considerations, poverty headcount, fixed allocation of funding, number of health subdistricts, and whether or not a local government is located in a geographically hard-to-reach area.Citation14

PBF schemes pay-for-performance but they usually finance inputs through seed grants. Payment rates are variable and depend on the available resource envelope and historical allocations, among other factors.Citation26 Donor-funded projects usually mix input- and output-based provider payment methods.

Provider autonomy to manage revenue is generally lowest with government budget financing, higher with donor funding, and highest with PBF funds.Citation31

Performance Monitoring

All purchasing arrangements include performance monitoring and accountability measures. However, the extent to which performance is linked to purchasing decisions varies considerably across the three models. PBF by definition links payments to results, with bonuses for better performance.Citation26 The public financial management system and rules are central to all three purchasing arrangements. Indeed, government systems usually complement accountability and performance monitoring measures within PBF schemes and donor-funded projects. All three purchasing arrangements include expectations for financial accountability, which is pursued through financial reporting, audits, and governance measures such as procurement procedures.Citation32 Facility structures such as hospital boards and health unit management committees provide oversight at the service provider level. Hierarchical structures provide supportive supervision.Citation33 PBF and donor-funded projects have built-in performance monitoring and accountability mechanisms. Linkage of payment to individual provider performance is limited across the three purchasing arrangements, but PBF tends to spur individual provider performance by linking bonuses to results.

details the payment methods and rates, provider monitoring mechanisms, and level of provider autonomy under each type of purchasing arrangement.

Table 3. Purchasers, provider payment, performance monitoring, and implications for UHC.

Discussion

Although progress has been made in ensuring strategic purchasing is embedded within the purchasing functions in each of the financing arrangements in Uganda, several challenges greatly limit the ability of strategic purchasing to contribute to achieving UHC goals. Some of the main challenges are summarized below.

Lack of Purchasing Power

The power of strategic purchasing is limited in Uganda because of the small share of total health spending that flows through strategic purchasing mechanisms. If a purchaser controls a large share of total funds in the health system, it can exert influence on resource allocation, create incentives for providers, and improve accountability throughout the system. Public financing for health in Uganda is constrained by low budget allocations for health, a low GDP growth rate (5%) that is not commensurate with the high population growth rate, and a low revenue base, with a tax-to-GDP ratio of 15.8% (FY 2018/19).Citation34 Because the public budget contributes such a low share of total health funding, the MOH, as the purchaser for the government budget, has limited purchasing power, constraining its ability to provide financial protection for its population.

Fragmented Purchasing Arrangements

Another challenge that Uganda faces with its multiple health purchasing mechanisms, especially PBF schemes and donor-funded projects, is sustainability. Project-based programs offer less-comprehensive benefits than the UNMHCP and can overlap in the covered geographies and targeted beneficiary types, leading to duplicative efforts and inefficiencies. Incentives to providers who are paid by salaries, are weak. Absenteeism and neglect of duty are not uncommon. Overall, donor funding has a short lifespan, usually three to five years. This is a major vulnerability for UHC programs, especially in countries like Uganda where development assistance contributes significantly to health financing.

Similarly, many PBF pilots have been implemented outside of government institutions that have health financing roles at national and subnational levels.Citation2,Citation35 Many of these projects have used vertical approaches that assign purchasing and payment functions to international NGOs. Uganda needs a PBF program that aligns with mandated institutional arrangements for payment, verification, and public policy so it can feasibly scale up. The URMCHIP project is an ongoing government effort to scale up innovations that align with the tenets of strategic health purchasing and can inform solutions for integrating strategic purchasing into government systems. Performance-related payment can also help strengthen health system building blocks and thereby help improve overall facility performance.Citation36

Public Financial Management Rules that Limit Incentives for Efficiency and Quality

Several challenges related to public financial management rules and processes also limit the effectiveness of strategic health purchasing in Uganda. The processes used by the public sector to monitor performance, as well as pay providers (including health workers) do not create incentives for providers to improve service quality and efficiency. Overall, performance management of frontline operations is undermined by the payment arrangements for individual health workers. Payroll is centralized at the national level, making it difficult to carry out performance management at the facility level. The disciplinary and reprimand processes for public servants (health workers on government payroll) are so elaborate that it could take not less than 5 years to make a final determination on whether or not to dismiss an errant health worker. The sense of “job” security undermines performance objectives.

Misaligned Accountability Mechanisms

Local governments are financially accountable mainly to the national treasury, and they send performance results to parent ministries.Citation13 For example, district health offices must account for spending directly to the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development; and they must send output reports, in the form of health management information system (HMIS) data, to the MOH. Each ministry imposes sanctions for delayed reporting and failure to meet expectations—often by delaying the next quarterly disbursement from the treasury.Citation34 The government has implemented measures to curb misuse of funds and corruption, including indicting and prosecuting officers responsible for budgets at different levels of service delivery, although many of the measures are yet to yield positive results.Citation37

Performance accountability is managed by the soft administrative mechanisms described above, partly because the drivers of underperformance generally arise upstream from purchasing organizations.Citation38 Districts hold performance review meetings, and the MOH publishes a league table to display the performance ranking of local governments. The central government has added innovations to address the main sources of suboptimal performance, but the existing health financing architecture may not be conducive to support an adequate and acceptable package of reforms such as strategic purchasing for UHC.Citation38

PBF schemes and donor-funded projects place greater emphasis on financial accountability because funds are disbursed based on performance.Citation2 Within PBF projects, outputs are verified before payments are made. The extended district health management team within the URMCHIP project uses paper-based verification, which often leads to delayed release of funds. A standardized electronic system that uses existing supervision systems may be more effective and efficient in the long run. A unified electronic system for reporting results from publicly funded and donor-funded projects—instead of the current fragmented system—could help strengthen performance accountability, improve the quality of services, and expand service coverage.

Donor-funded projects usually require regular reports to track performance, and project managers and sponsors often make field visits to confirm the outputs reported. However, their preference for strong and capable service providers has tended to reinforce inequities, especially in remote localities with weak health systems or high investment costs.Citation39 A study by Ssengooba et al. (2017) found that the central and local governments were poor at negotiating priorities for their population when engaging with development assistance fundholders and NGOs.Citation40

Lack of Integration of Donor Funds with Government Systems

Development assistance can potentially improve purchasing functions, but donor-funded projects generally have external purchasers that are unwilling to pool resources or coordinate with the public financing system. This may be due to donor priorities, fears about misuse of funds due to corruption, the difficulty of illustrating results when funds are jointly used, and bureaucratic delays within the government system.Citation41 But often several donor-based projects with similar beneficiaries work in the same district or with the same fundholder. This leads to duplication and inefficiency.Citation41 Several strategies are being implemented to deal with this challenge. In sectors such as reproductive health, donors have been assigned to particular service regions. This “zoning” of donors reduces duplicative efforts and makes better use of donor funds to expand access to essential services and expand population coverage.

Several types of forums help facilitate dialogue between development partners and the MOH and other health-sector stakeholders.Citation42 These forums can help reduce fragmentation and improve alignment. Studies show that most donors focus on the results of the projects they fund and many of their programs use some form of PBF, but they need to better align their priorities with those of the government in order to increase coverage of services within the UNMHCP.

Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of the study is its reliance on predominantly qualitative information using a document review approach. Given the limited published research on health financing and strategic purchasing in Uganda, we had to rely largely on unpublished policy documents and stakeholder consultations.

Conclusions

Despite the constraints related to the level of health funding and public financial management rules, the government budget remains the most viable source of financing for UHC in Uganda, and it should therefore be the focus of efforts to improve strategic purchasing. The government budget is also the most viable and equitable option for expanding coverage, and it is most amenable to strategic purchasing given its predictability.Citation38 Donor funds, by contrast, are largely unpredictable and short-term, and the population benefits only while the project is active.

If the government budget is to be the main vehicle for strategic purchasing to advance UHC in Uganda, some challenges will need to be addressed through a number of key actions and reforms:

Greater pooling of funds by purchasing entities in the health sector, including government funding agencies and donors. In particular, “basket funding” to strengthen the pooling of resources from donor agencies with the government budget should be a top policy priority.

Government leadership in determining the package of services that development partners provide. Services procured through PBF and donor-funded projects remain fragmented and not well aligned with the UNMHCP priorities and Uganda’s UHC agenda. Population coverage must be progressively expanded through sustainable and affordable services. The current practice of assigning development partners to particular regions, coupled with improved management and tracking of donor resources, can help ensure more equitable distribution of donor resources and more effective use of those resources.

Increased funding and greater flexibility, transparency, and accountability so resources can be channeled to where they are needed most. Efficiency can be enhanced if local governments improve the mechanisms they use to monitor and track resources allocated to them. More advocacy is also needed to increase government allocations to health if strategic purchasing is to become a more viable public policy option. The government contribution to total health financing remains very low, which makes implementation of strategic purchasing in public financial management systems less feasible. Local governments also receive largely conditional grants, which limits the ability of districts and facilities to use money according to identified needs.

Clearly defined strategic purchasing roles and mechanisms for strengthening performance management at the national and local levels. The governance system and performance management systems for strategic purchasing are weak. Mechanisms for strengthening performance management at the national and local levels should be coupled with appropriate incentives that encourage managers and providers to develop an organizational culture that promotes quality and efficient service delivery. Contracts for district health teams, officers in charge of facilities, and individual providers should be specific and linked to key outputs. However, care should be taken to ensure that funding is commensurate with resource needs.

Modifications to the current HMIS to make it more unified and provide more accurate information on outputs and the costs of delivering services. This is critical for price setting. It can also help in determining the appropriate mix of payment mechanisms, verifying provider outputs for performance management decisions and actions, and reducing the high verification costs incurred in PBF projects.

Author Contributions

CC conceptualized the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework that guided this paper. EEK, FS, AS, RS, and CM conceptualized the paper. EEK, FS, AS, RS, and CM performed the analysis for the paper. EEK wrote the first draft of the paper. EEK, FS, AS, RS, NO, CC, and AM provided substantial comments during the writing of the paper.

Ethical Approval

This manuscript did not require ethical approval since the information used was largely obtained through a review of existing public documents.

Informed Consent From Participants

It was not necessary to obtain consent for publication because individual respondents were not interviewed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Centre (SPARC) and the consortium of Africa-based Anglophone and Francophone partners that created the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework. SPARC is a resource hub hosted by AMREF Health Africa with technical support from Results for Development; to generate evidence and strengthen strategic health purchasing in sub-Saharan Africa to enable better use of health resources. The authors also appreciate the individuals who provided insights, comments, and reviews that improved the quality of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. The world health report. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage.[accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44371/9789241564021_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2010.

- Ssengooba F, Ekirapa E, Musila T, Ssennyonjo A. Learning from multiple results-based financing schemes: an analysis of the policy process for scale-up in Uganda (2003-2015). Geneva (Switzerland): Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2000. Health systems: improving performance. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2000. [accessed 2022 Apr 18]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42281.

- Preker AS, Liu X, Velenyi EV, Baris E editors., Public ends, private means: strategic purchasing of health services. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2007. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6683.

- Mathauer I PowerPoint presentation presented at: the “Strategic purchasing for UHC: unlocking the potential” global meeting; 2016 Apr 25–27; Geneva, Switzerland.

- Hanson K, Barasa E, Honda A, Panichkriangkrai W, Patcharanarumol W. Strategic purchasing: the neglected health financing function for pursuing universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries. Comment on “What’s needed to develop strategic purchasing in healthcare? Policy lessons from a realist review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(8):501–11. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2019.34.

- Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements. Health Policy (New York). 2001;56(3):171–204. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00149-4.

- Preker AS, Harding A. Political economy of strategic purchasing. In: Preker AS, Liu X, Velenyi EV, Baris E, editors. Public ends, private means: strategic purchasing of health services. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2007. p. 13–51. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6683.

- Ghoddoosi-Nejad D, Janati A, Arab Zozani M, Doshmangir L, Sadeghi Bazargani H, Imani A. Is strategic purchasing the right strategy to improve a health system’s performance? A systematic review. Bali Med J. 2017;6(1):102–13. doi:10.15562/bmj.v6i1.369.

- Ghoddoosi Nejad D, Janati A, Arab-Zozani M. The neglected role of stewardship in strategic purchasing of health services: who should buy? East Mediterr Health J. 2019;24(11):1038–39. doi:10.26719/2018.24.11.1038.

- Abolghasem Gorji H, Pour Mousavi SM S, Shojaei A, Keshavarzi A, Zare H. The challenges of strategic purchasing of healthcare services in Iran Health Insurance Organization: a qualitative study. Electron Physician. 2018;10(2):6299–306. doi:10.19082/6299.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Uganda health accounts: national health expenditure. Financial years 2014/15 and 2015/16. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2018. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. http://library.health.go.ug/publications/health-insurance/national-health-accounts-fy-201415-201516.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. National health accounts 2016 - 2019. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 18]. http://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/NHA%20Uganda_2016-2019_Report_Final.pdf.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Primary health care grants guidelines: financial year 2016/17. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2016. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://www.health.go.ug/cause/primary-health-care-grants-guidelines/.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. National results-based financing framework for the health sector. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2017.

- UNICEF Uganda Country Office; Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Tracking off-budget financial resources in the health sector. FY2019/2020. Kampala (Uganda): UNICEF Uganda Country Office, Ministry of Health; 2021. [accessed 2022 May 2]. https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/8116/file/UNICEF-Uganda-Tracking-Off-Budget-Financial-Resources-Health-Sector-2020.pdf.

- Lee H. Aid allocation decisions of bilateral donors in Ugandan context. Dev Stud Res. 2022;9(1):70–81. doi:10.1080/21665095.2022.2043174.

- UNICEF Uganda Country Office; Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Tracking off-budget financial resources in the health sector. FY2018/19. Kampala (Uganda): UNICEF Uganda Country Office, Ministry of Health; 2020. [accessed 2020 Sep 17]. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/media/7276/file/Tracking%20off%20budget%20financial%20resources%20in%20the%20health%20sector%20FY2018-19-lores.pdf.

- Cashin C, Gatome-Munyua A. The Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework: A Practical Approach to Describing, Assessing, and Improving Strategic Purchasing for Universal Health Coverage. Health System Reform. 2022;8:2, doi:10.1080/23288604.2022.2051794.

- Center for Health Policy and Systems Development (CHPSD). Kampala (Uganda): Makerere University School of Public Health. [ accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://sph.mak.ac.ug/research-innovations/centers/center-health-policy-and-systems-development-chpsd.

- Nabyonga Orem J, Mugisha F, Kirunga C, MacQ J, Criel B. Abolition of user fees: the Uganda paradox. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 2):ii41–ii51. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr065.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Health Sector Strategic Plan III 2010/11-2014/15. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2010. [accessed 2022 Apr 18]. http://publications.universalhealth2030.org/uploads/health_sector_strategic_plan_uganda_2014.pdf.

- Kadowa I. A case study of the Uganda National Minimum Healthcare Package, EQUINET Discussion paper 110. Uganda: Ministry of Health, EQUINET; 2017 [discussion paper 110. [accessed 2022 Apr 18]]. https://www.equinetafrica.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/EHB%20Uganda%20case%20study%20repAug2017pv.pdf.

- Stierman E, Ssengooba F, Bennett S. Aid alignment: a longer-term lens on trends in development assistance for health in Uganda. Glob Health. 2013;9(1):7. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-9-7.

- Ssennyonjo A, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Musila T, Ssengooba F. Fitting health financing reforms to context: examining the evolution of results-based financing models and the slow national scale-up in Uganda (2003-2015). Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1919393. doi:10.1080/16549716.2021.1919393.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Results based financing implementation manual. Uganda Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health Services Improvement Project. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2018.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. National policy on public private partnership in health. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2012. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. http://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/National%20Policy%20on%20Public%20Private%20Partnerships%20in%20Health%20Final%20Print_0.pdf.

- Ssennyonjo A, Namakula J, Kasyaba R, Orach S, Bennett S, Ssengooba F. Government resource contributions to the private-not-for-profit sector in Uganda: evolution, adaptations and implications for universal health coverage. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12939-018-0843-8.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. [ accessed 2022 Apr 18]. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en.

- Davies F, Geddes M, Wabwire M. Equity of local government health financing in Uganda. London: ODI; 2021 [Accessed 2022 May 2]. ODI Working paper 617. Public Finance www.odi.org/equity-of-local-government-health-financing-in-uganda.

- Chama-Chiliba CM, Hangoma P, Chansa C, Mulenga MC. Effects of performance-based financing on facility autonomy and accountability: evidence from Zambia. Health Policy OPEN. 2022;3:100061. doi:10.1016/j.hpopen.2021.100061.

- World Health Organization. Governance for Strategic Purchasing: an analytical framework to guide acountry assessment. [Accessed 2 May 2022.] Health financing guidance. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000025.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Health Sector Development Plan (draft) 2021-2025. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2021.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development. Background to the budget: fiscal year 2019/20. Industrialization for job creation and shared prosperity. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development; 2019. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://www.finance.go.ug/sites/default/files/Budget/BTTB%20FY2019.20%202019%20web.pdf .

- Witter S, Bertone MP, Namakula J, Chandiwana P, Chirwa Y, Ssennyonjo A, Ssengooba F. (How) does RBF strengthen strategic purchasing of health care? Comparing the experience of Uganda, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Health Res Policy. 2019;4(1):3. doi:10.1186/s41256-019-0094-2.

- Ndanyi DM. Performance management and health service delivery in the local governments of Uganda. J Afr Stud Dev. 2019;11(6):84–93.

- Gumisiriza P, Mukobi R. Effectiveness of anti-corruption measures in Uganda. Rule Law Anti-Corrupt Cent J. 2019;2019:8.

- Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Mayora C, Ssennyonjo A, Baine SO, Ssengooba F. Purchasing health care services for universal health coverage: policy and programme implications for Uganda. In: Ssengooba F, Kiwanuka SN, Rutebemberwa E, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, editors. Universal health coverage in Uganda: looking back and forward to speed up the progress. Kampala (Uganda): Makerere University; 2017. p. 205–25. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337534542_Purchasing_Health_Care_Services_for_Universal_Health_Coverage_Policy_and_Programme_Implications_for_Uganda.

- Oomman N, Bernstein M, Rosenzweig S Seizing the opportunity on AIDS and health systems. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2008. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/16459_file_Seizing_the_Opportunity_web.pdf.

- Ssengooba F, Namakula J, Kawooya V, Fustukian S. Sub-national assessment of aid effectiveness: a case study of post-conflict districts in Uganda. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0251-7.

- Kirabo-Nagemi C, Mwesigwa CL. Donor power and prioritization in development assistance for health policies: the case of Uganda. J Dev Econ. 2021;2:54–74.

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health. Mid-term review report for the Health Sector Development Plan 2015/16 - 2019/20. Kampala (Uganda): Ministry of Health; 2018. [accessed 2021 Sep 21]. http://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/HSDP%20MTR%20Report-Final_25.10.2018%20final2222.pdf.