ABSTRACT

During the last two decades, Mexico adopted policies intended to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of medicines procurement in its nationally fragmented health system. In this policy report, we review Mexico’s efforts to guarantee access to medicines during three national administrations (from 2000 to 2018), and then examine major health system changes introduced by the current government (2018–2024), which have created significant setbacks in guaranteeing access to medicines in Mexico. These recent changes are having important consequences in the levels of satisfaction of health care users and citizens, household expenditure on health, and health conditions. We suggest key lessons for Mexico and other countries seeking to improve pharmaceutical procurement as part of guaranteeing access to medicines.

Introduction

Access to medicines in health systems has gained increasing attention in the past decade, illustrated by the inclusion of universal health coverage (UHC) as a target (3.8) of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)3 (Good Health and Wellbeing).Citation1 The SDG definition of UHC includes “access to safe, effective, quality and affordable medicines and vaccines for all.”

Public procurement of pharmaceuticals is a key component of the public commitment to guarantee access to medicines.Citation2 The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the critical importance of effective public procurement of medicines in health systems as a mechanism for assuring access, efficiency and quality, as well as moving toward the ultimate system goals of improving health status, citizen satisfaction, and financial risk protection.Citation3 The public procurement of medicines is an essential component of national pharmaceutical policies, closely connected to the three related processes of financing, selection, and distribution.

Public procurement is part of the broader health system subfunction of “strategic purchasing,” which, in turn, is part of the financing function and seeks to obtain more value out of money spent on health through the purchase of services and inputs such as medicines.Citation4 National rules that govern public procurement aim to ensure transparent and ethical transactions (and control corruption), whereby the buyer (often a public payer such as a government or an agency) receives the requested product, and the seller (medicines manufacturer, distributor or wholesaler) receives timely payment.Citation2 Public procurement offices require trained human resources, adequate investments and budgets, and appropriate procedures in order to achieve the public goals set by national policy. There are various ways to organize public procurement at a national level, with important health system consequences.Citation3

Over the past several decades, Mexico has sought to guarantee better access to medicines through various public policies. The implementation in 2004 of Seguro Popular (SP), a public insurance program targeting the population without social security (around 60 million people), guaranteed access to a specific set of health care interventions, including pharmaceuticals.Citation5 SP increased the budget for health and assured sustainable financing for medicines. About 30% of SP financing transferred to states was recommended for use in the procurement of medicines, although the actual amounts spent varied by state.Citation5

In two national administrations, in 2007–2012 and 2013–2018, Mexico adopted several strategies to support wider health sector reforms to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of medicines procurement in its nationally fragmented health system. In this policy report, we review Mexico’s policy efforts to guarantee access to medicines during three previous national administrations, and examine major health system changes introduced by the current government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO) (2018–2024), which have created significant setbacks in access to medicines. These recent changes, we argue, are having important consequences in the levels of satisfaction of health care users and citizens, household expenditure on health, and important health conditions. We suggest key lessons for Mexico and other countries seeking to improve pharmaceutical procurement.

Procurement of Medicines in Mexico 2000-2018

Mexico implemented several institutional changes, during three national administrations (from 2000 to 2018), to improve the strategic purchase of medicines throughout the national health system, especially with regard to the purchase of single-sourced medicines, a system for the consolidated procurement of multi-source, non-patented medicines, and efforts to improve transparency in public sector procurement of medicines.

Selection: Mexico has a Basic List of Health Inputs (Cuadro Básico y Catálogo de Insumos para la Salud or CBCI) that has provided a reference point for many selection decisions by public health institutions since 1983. The institutional list of medicines for the Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS) (Cuadro Básico institutional) was a driving force supporting improvements on how inclusion decisions were made since the late 2000s. An important reform in 2011 strengthened the use of health technology assessment in decisions about what to include in CBCI (see: Reglamento Interior de la Comisión Interinstitucional del CBCI, DOF 22/06/2011); however, many problems remained with CBCI processes and in priority-setting across the health sector.Citation6 In addition, each public sub-system used its own process of medicines selection for inclusion in its benefit package and respective treatment protocols that guided the use of the covered medicines, creating problems of inconsistency, lack of coordination, and duplication of analyses. For instance, SP included two lists of services and medicines: first, a set of 294 essential services for conditions of high incidence and relatively low cost, with services delivered in outpatient clinics and general hospitals (known as CAUSES, or Catálogo Universal de Servicios de Salud); and second, a package of 66 high-cost interventions for conditions with potentially catastrophic financial consequences for families delivered in accredited specialty units and financed by a special fund (FPGC or Fondo de Protección contra Gastos Catastróficos).Citation5

Single-source medicines procurement: In 2008, the national government created the Coordinating Commission for Negotiating the Price of Medicines and Other Inputs (CCNPM) for the purchase of single-source medicines (typically high price products) involving the two major social security systems and Mexico’s national Ministry of Health.Citation7 The new commission operated through a technical secretary and three advisory groups: clinical, economic and intellectual property advisory committees.Citation8 This commission used collaboration among several public health institutions to negotiate lower prices for patented medicines, which resulted in substantial savings in public pharmaceutical expenditure. According to the annual reports of the CCNPM, the reported savings for the period 2008–2011 of negotiations amounted to $355 million USD in procurements due to lower prices.Citation7 A recent analysis calculated a total savings from 2014 to 2019 of $236.5 billionFootnotea USD from reduced prices by CCNPM.Citation9

Multi-source medicines procurement and distribution: Since 2006, the Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS)—the main social security agency in Mexico and the largest buyer of medical supplies in Latin America—began to consolidate the purchases of multi-source medicines for its own state delegations and high specialty medical units around the country, setting maximum reference prices for public procurement. Later on, other social security health institutions joined IMSS consolidated purchases. Despite significant savings, problems arose with noncompliance of providers, and bid rigging or collusion in purchases. Consequently, IMSS procurement practices were revised in 2011 to align with OECD guidelines against collusion.Citation10

In 2013, the Mexican government established a system for the pooled procurement of non-patented medicines in the public sector. This new system was coordinated by IMSS to purchase medicines and other health inputs on behalf of all other social security institutions, the national Ministry of Health and most state ministries of health. The purposes of this system (known as Compra consolidada-IMSS) were: to select trustworthy manufacturers with high-quality products; to purchase the most cost-effective medicines in the right amounts; and to include distribution in the purchase negotiations in order to assure consistent and timely deliveries throughout Mexico.Citation11 This system for purchase of multi-source medicines used the consolidated market power of the various health subsystems to obtain better prices and produce savings in medicine purchases. A recent analysis calculated a total savings from 2014 to 2019 of $1,219 billion USD from reduced prices negotiated by IMSS.Citation9 The majority of purchases in this system were concentrated on ten distributors, with 70% focused on only three. This concentration was criticized as corruption and driving up costs and was used by the AMLO government to justify the 2019 reforms.

Transparency: Mexico established an electronic system known as CompraNet for managing public tenders for goods and services in 1996. CompraNet includes medicines purchases, and registers all tenders, awarded manufacturers and distributors, product prices and volumes.Citation12 In addition, IMSS created a website (http://compras.imss.gob.mx) to provide information on IMSS purchases and assure its accountability, and this website was expanded to include data for Compra consolidada-IMSS. The website contains information on purchases from 2011 onward, and from 2012–2018 it contained information on purchases by other institutions through the consolidated purchases system. The information currently available online, however, is no longer fully updated on medicines and health inputs purchased by IMSS, significantly reducing transparency in procurement.

These various efforts helped improve Mexico’s procurement processes for medicines from 2000 to 2018 through strategies such as development of a skilled workforce in procurement and strengthening centralized procurement information and dashboards, although various problems remained.Citation10,Citation13 There were signs of collusion in the bidding procedures among providers, and a high though decreasing proportion of pharmaceuticals were purchased through direct awards. The changes in the procurement system, however, gradually increased the availability of medicines in public institutions (although gaps still remained, reflected in high levels of out-of-pocket spending for medicines).Citation9,Citation14

Procurement of Medicines in Mexico after 2018

After the presidential elections of December 2018, the new administration (under AMLO, who campaigned strongly against corruption) moved to eliminate SP. In November 2019 the Mexican Congress (with a majority of seats held by AMLO’s party) voted to remove SP from the General Health Law and establish the Health Institute for Welfare (INSABI), in order to create a new “system of universal and free access to health services and associated medicines for the population that lacks social security.”Citation15,Citation16 INSABI then began to negotiate agreements with Mexico’s 32 states to provide these services through the program of “Health Care and Free Medicines,” although eight states refused to sign agreements to join INSABI (as of February 2020).Citation17 The creation of INSABI was accompanied by major changes in the selection, procurement and distribution of medicines.

Selection: The decree to eliminate SP and establish INSABI explained the “what and the why” of the reform for free medicines, but it omitted the “how” this reform would be achieved. With regard to medicines selection, in contrast to SP, INSABI did not include a specific benefit package, thereby creating ambiguity about which medicines would be provided by the government as part of the right to health and free medicines. There was an effort to revise and update the CBCI, but it was not linked to a revision of treatment protocols, nor to an explicit list of medicines at each level of healthcare.

Procurement: Between 2019 and 2022, the institutional responsibility for public procurement of medicines changed three times:

First, the Ministry of Financing (MoF): The Federal Administration Law, passed by the Mexican Congress in December of 2018, stated that only the MoF could be in charge of all pooled procurement in the public sector at the federal level, in order to improve public benefits and savings.Citation18In May 2019, the MoF announced that the new model for pooled procurement of medicines would be launched in the second half of 2019 with the purchase of various groups of pharmaceuticals.Citation19 The new procurement procedure, however, did not work as expected, and no offers for 62% of the tendered pharmaceutical codes were received.Citation20

Second, the Administrative Office of the MoF: In October 2019, the government published an agreement that transferred the responsibility for the pooled purchasing of medicines in the public sector to the Administrative Office of the MoF (Oficialía Mayor) and later announced the beginning of the pooled procurement of medicines and other health inputs for 2020.Citation21 On November 29, 2020, the CCNPM was dismantled.Citation22 The MoF, however, lacked the expertise and experience needed for the purchase of medicines, and their first public call for the pooled procurement of medicines for 2020 was delayed.Citation23 In the initial months of 2020, major shortages of all types of medicines were detected in the health facilities of all public health agencies throughout the country, confronting families with major challenges in obtaining and financing their health care.Citation24

Due to this failure in public procurement of medicines and the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, the legal framework underwent additional modifications. In order to facilitate the purchase of the vaccines and medicines needed to meet the demands of the pandemic, the Law of Acquisitions, Leases and Services in the Public Sector was amended so that the procurement of medicines would be exempt from the bidding process.Citation25 Then, the regulatory framework was revised to allow the purchase and import of pharmaceutical products not registered with the Mexican regulatory agency (COFEPRIS) if the products were approved by certain foreign regulatory agencies (such as the Swiss or US FDA) or received prequalification by the World Health Organization, in order to facilitate the purchase of pharmaceuticals in the global market and resolve shortages in Mexico.Citation26

Third, the United Nations Office of Project Services (UNOPS): On July 31, 2020, Mexico’s president announced the transfer of the full responsibility for pooled procurement of medicines in the public sector from the MoF to the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS).Citation27,Citation28 INSABI would sign a contract with UNOPS in the amount of $6.8 billion USD for the purchase of medicines for the period 2021–2024. The initial results of this new procurement model were not encouraging. The call for pooled procurement, originally planned for October, was delayed until December 2020.Citation29 UNOPS declared that the procurement process would conclude in May 2021 and that public health agencies would have to turn to emergency procurements through direct awards to meet the medicines demand for the first half of 2021. In June 2021, UNOPS declared that 55% of the requested pharmaceutical codes had been declared empty, with no tenders received.Citation30 UNOPS had managed only two previous projects for the public purchase of medicines on a much smaller scale (in Guatemala and Honduras), and even in those two cases UNOPS was unable to fill about 35% of the drug codes requested.Citation28 In the final days of November, INSABI announced its intention of organizing two independent tenders of medicines for 2022 using the Mexican public procurement system of CompraNet for various health agencies.Citation31

Distribution: In March 2019, through a presidential decree, the three most important private companies responsible for about 70% of the distribution of health inputs in Mexico were banned from participating in the procurement and distribution of medicines.Citation32 The government argued that these companies were abusing the public purse, a charge of corruption that was never proved.Citation14 This decision to ban the three companies triggered an acute shortage of prescription medicines, particularly cancer drugs.Citation33 The government then sought to reorganize the distribution of medicines in public health agencies to address these shortages. (IMSS later resumed purchases from one of these big distributors, Maypo. In 2020, IMSS purchased $55.8 billion USD worth of medicines, with 97% through direct-award contracts.Citation34)

Distribution via Birmex: On July 31, 2020, with the purpose of dismantling what the federal authorities called the “distribution oligopoly,” the government decided to hand over this responsibility to BIRMEX, a public corporation previously in charge of the production of vaccines but with no experience in the distribution of pharmaceuticals.Citation35 This new distribution system was unable to resolve the serious problems with access to medicines, since BIRMEX declared that the new system would not be in place until the second half of 2022.Citation36

Distribution via the military: On November 11, 2021, the President of Mexico publicly complained about the lack of medicines in public institutions and ordered an immediate solution to this problem.Citation37 Ten days later he stated that, if necessary, the military would take over the responsibility for the national distribution of medicines in public institutions.Citation38 In the same presentation, he reiterated his goal of guaranteeing the right to free medicines and health services, using the examples of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. A few days later, a general in retirement was appointed head of BIRMEX.Citation39 It has not been clear, however, what role the military took in the distribution of medicines or what percentage of medicines for public facilities would be distributed by them.

Transparency: An audit, implemented by the Ministry of Public Function in 2021, determined that INSABI had no defined procedures to do market research or processes to plan, program and supervise the safety of pharmaceuticals and their delivery to state ministries of health. In December 2021, legislators in the Mexican Congress demanded more transparency in the processes and contracts negotiated by UNOPS, which reached approximately $6 billion USD from 2021–2024.Citation40 UNOPS promised on its website to “help maximize the efficiency, transparency, and effectiveness of the procurement of medicines in Mexico,”Citation41 but the agency has so far not publicly presented unit prices or quantities of different medicines purchased.

Effects of the Changes in the Procurement of Medicines in Mexico

The major institutional changes in Mexico’s procurement of medicines from 2019 to 2022 have had significant consequences in the availability of medicines in public institutions, the cost of pharmaceuticals, the satisfaction of health care users, private expenditure on health, and health conditions.

Availability of medicines in public institutions: Information gathered by several NGOs in Mexico indicates that the availability of many types of medicines (cancer drugs, insulin, non-Covid vaccines) has decreased significantly in the past two years. . The number of monthly unfulfilled prescriptions at IMSS, for example, grew from less than 300 thousand in January of 2017 to over a million and a half in May of 2021.Citation42 But the problem of unfulfilled prescriptions is not limited to IMSS; it is reported to affect all states, all public institutions and all levels of care ().Citation12,Citation43

Figure 1. Percentage of unfilled prescriptions by beneficiary in the main Mexican social security institutions (2017-2021).Citation44

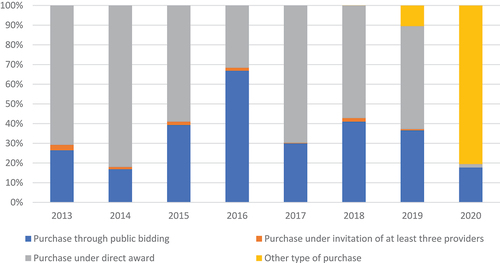

Cost of pharmaceuticals: The lack of medicines in public institutions due to problems in the pooled procurement of pharmaceuticals has increased the number of emergency procurements through direct awards (not through competitive bidding), which are associated with higher purchase prices and higher corruption risks. Public funds used in direct purchase contracts of pharmaceuticals increased from an annual average of $1,075 billion USD in the period 2013–2018 to $1,558 billion USD in 2019.Citation19 In addition, there emerged in 2019 a new category of purchases, “other procurements (otras contrataciones),” which represented 80% of the government’s consolidated procurement of medicines in 2020 ().Citation19 It is not clear whether these purchases involved competitive bidding or direct awards.

Figure 2. Percentage of purchase (value) of pharmaceuticals in the public sector, Mexico 2013-2020.Citation45

Satisfaction of healthcare users: Patients’ complaints about the lack of medicines in public health care facilities and public demonstrations to demand an immediate solution to medicine stock-outs have surged. According to the NGO Zero Shortage, complaints about medicines shortages in public facilities have increased dramatically in the past two years. These shortages have been denounced in criminal courts, the National Human Rights Commission and the Inter-American Human Rights Commission by several civil society organizations, most notably, the National Movement for Health/Parents of Children with Cancer, and Zero Impunity.Citation24

Demonstrations demanding solutions to the lack of medicines have also been organized in several states since the beginning of 2021. In November 2021, a group of parents of children with cancer promised to organize demonstrations at the Mexico City International Airport every Tuesday until the shortage of cancer drugs is solved.Citation46 The Mexican government responded negatively to the demonstrations.Citation47

The lack of medicines in public institutions, in addition to the interruption of public services during the COVID-19 pandemic, has forced patients and their families to buy the pharmaceuticals they need in private pharmacies, increasing out-of-pocket expenditure in health. According to the National Income and Expenditure Household Survey 2020, the average quarterly expenditure in health in Mexican households increased 40% in the past two years, from $45 USD (901 constant MXN pesos) in 2018 to $63 USD (1,266 constant MXN pesos) in 2020.Citation48 Household expenditure on medicines, which grew by 68% (from $18.80 USD [376 MXN pesos] to $31.60 USD [632 MXN pesos]) in this same period, was the health item with the highest increase.Citation49

Private expenditure on health and health conditions: There are no formal studies to date on the effects of the scarcity of medicines in public facilities on the treatments and outcomes of specific diseases. However, various groups of parents of children with cancer have publicly criticized the lack of cancer drugs in public hospitals as having negative impacts on the survival rates of children with leukemia and other cancers.Citation50 These medicines are expensive and low-income families cannot afford them. It is plausible that shortages of other essential medicines are producing increases in out-of-pocket expenditures on pharmaceuticals and reductions in treatment effectiveness.

The abrupt changes in institutions and procedures related to medicines procurement had important consequences on the availability and access to medicines in Mexico. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the impact through medicine price inflation and global raw material shortages.Citation51 Two possible solutions have been discussed in policy and academic circles: 1) the reestablishment of the CCNPM and the original system for the consolidated procurement of non-patented medicines in the public sector, and 2) the creation of an international commission of experts in pharmaceutical policies to identify alternatives. Most recently, the AMLO government has proposed plans to assign the Mexican General Comptroller Office (Secretaría de la Función Pública) to control all pooled procurement procedures in Mexico, although the legislature has not approved this measure yet.Citation52

The risk of not taking immediate action is that the current acute crisis of medicines shortages, high product prices, and rising household out-of-pocket expenditures will continue for several more years. The financial support of the AMLO administration to the health sector has been poor, in spite of the major cuts implemented by the previous administration between 2015 and 2018 and the occurrence of the Covid-19 pandemic. There have been basically no changes in the resources allocated to the health sector for the period 2018–2021.Citation53 These conditions are likely to have major consequences for the health and wellbeing of the Mexican population, especially the more vulnerable groups.

Recently, in March 2022, the AMLO government announced a national initiative to provide health services for the population without social security through an expansion of the program known as IMSS-Bienestar (to replace services provided by INSABI), directed at marginalized communities.Citation54 The program is expected to federalize state hospitals and primary health centers. These changes in the health system could have significant implications for procurement practices, as the changes are implemented in participating states across Mexico.

Lessons

This policy report on the evolution of measures taken by Mexican federal government to procure medicines shows that the changes introduced by the administration of President López Obrador, while intended to improve public procurement for the health system, were unfortunately poorly planned, abruptly implemented, and frequently ineffective or counterproductive. Instead of improving procurement, the measures undermined the strategic purchasing capacity of public institutions, produced major shortages of critical health inputs, and generated dissatisfaction and increased out-of-pocket expenditure among health care users. Analyzing and understanding the political economy of these policy changes represents an important research question, but it is beyond the scope of this policy review paper.

Many countries in Latin America are seeking to increase their organizational capacity of strategic purchasing of health products (especially medicines) as a core function of their health systems, in order to expand health coverage and increase both efficiency and equity.Citation55 The following lessons about institutional capacity, from the recent experiences in Mexico, may be relevant for other countries:

Technical expertise for procurement: Public procurement of pharmaceuticals is a complex process that demands organizational capacity to assure effective and efficient purchases. Any changes in this procedure should be made ensuring sufficient technical and managerial expertise and experience are provided, especially regarding the processes of national and international tenders of public procurement that involve complex assessments of price, quality, payment, delivery, and registration, and potential trade-offs among these different features. Building the necessary technical and managerial expertise takes time and effort, and requires institutional investment in retaining valued employees. Institutional capacity in these areas can be quickly undermined through abrupt institutional changes, as illustrated by the recent Mexican changes.

Procurement in the health system: Public procurement of medicines is only one dimension assuring access to pharmaceuticals in the health system, and it needs to be closely linked to the processes of financing, selection, and distribution. Financing implies the mobilization of sufficient resources to purchase the medicines needed by the population. Selection requires highly technical expertise from the clinical, pharmacovigilance, and pharmacoeconomic fields to assure that medicine lists reflect population health needs. Timely distribution demands strong logistics. Disruptions in any of these processes can create serious shortages of medicines, which has significant economic and health consequences. Centralization of public procurement without selection and distribution backups, as was done in Mexico, creates risks for the entire national health system and for families with health problems.

Transparency of public procurement: Transparency is a crucial characteristic of public procurement procedures. The purchase of pharmaceuticals using public resources should be a transparent and fair transaction between buyers and providers, with public information on prices, quality, and competitive bidding, and trade-offs made in purchase decisions. In pooled procurement processes in the public sector, open competition and clear rules should be guaranteed to allow all actors—including the industry—to collaborate and achieve public goals.

Accountability for public procurement: The procurement of medicines represents one of the main categories of expenditure of public health systems, and mechanisms of accountability should exist to assure that corrupt practices are identified and corrected, and that charges of corruption are substantive and fair. With the absence of effective public institutions to exercise this kind of accountability in the current political context of Mexico, civil society organizations have emerged to help identify and analyze problems in the procurement of medicines. More broadly, Mexico needs mechanisms to monitor and evaluate public procurement processes on a regular basis (ideally by an independent organization), and changes to procurement procedures should be measured and publicly discussed, alongside recommendations for improvement.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[a]. Mexican pesos were converted into US dollars using the average exchange rate obtained from Banco de Mexico (https://www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/main.do?page=tip&idioma=en#). For calculations to convert Mexican pesos to US dollars, please contact the authors for the supplementary file.

References

- Organization WH. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). [ accessed May 4, 2022] https://www.who.int/health-topics/sustainable-development-goals#tab=tab_1.

- Wirtz VJ, Hogerzeil HV, Gray AL, Bigdeli M, de Joncheere CP, Ewen MA, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Jing S, Luiza VL, Mbindyo RM, et al. Essential medicines for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2017;389(10067):403–10. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9.

- Roberts MJ, Hsiao W, Berman P, Reich MR. Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- Cashin C, Nakhimovsky S, Laird K, Strizrep T, Cico A, Radakrishnan A , et al. Strategic health purchasing progress: a framework for policymakers and practitioners. Bethesda (MD): Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc; 2018.

- Moye-Holz D, Dreser A, Gómez-Dantés O, Wirtz VJ. Promoting access to cancer medicine in Mexico: seguro popular key policy components. In: Babar Z, editor. Global Pharmaceutical Policy. Singapore, Asia: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020. p. 177–222.

- Barraza Lloréns M, González Pier E, Giedion U. Retos para la priorización en salud en México. Giedion U, Distrutti M, Muñoz A, Pinto D, Díaz A, editors. La priorización en salud paso a paso: cómo articulan sus procesos México, Brasil y Colombia. Washington (DC): Inter-American Development Bank; p. 15–89 ; April 2018 accessed April 30, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0001092

- Gómez-Dantés O, Wirtz V, Reich MR, Terrazas P, Ortiz M. A new entity for the negotiation of public procurement prices for patented medicines in Mexico. Bull WHO. 2012;90(10):788–92. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.106633.

- Reglas de Operación de la Comisión Coordinadora para la Negociación de Preciso de Medicamentos y Otros Insumos para la Salud. Diario Oficial de la Federación 2008;June. [accessed October 9, 2021] http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5298148&fecha=07/05/2013

- Llanos Guerrero A Eficiencia del gasto en salud: compra consolidada de medicamentos. Centro de Investigación Económica y Presupuestaria; March 16, 2021. [accessed February 11, 2022]. https://ciep.mx/4Ys7

- OECD. Public procurement review of the Mexican institute of social security: enhancing efficiency and integrity for better health care. Paris, France: OECD, 2012. https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/49408672.pdf [accessed February 12, 2022]

- BID. Que financiar en salud y a qué precio. [accessed October 13, 2021] https://learning.edx.org/course/course-v1:IDBx+IDB25x+3T2020/home

- Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, Mexico. Compranet. [ accessed February 11, 2022] https://compranet.hacienda.gob.mx/web/login.html.

- OECD. Second public procurement review of the Mexican institute of social security (IMSS). Paris, France, OECD, 2018. [accessed May 1, 2022] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264190191-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/9789264190191-en [accessed May 1, 2022]

- Agren D. Lack of medicines in Mexico. Lancet. 2021;398(10297):289–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01656-1.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Decreto por el que se reforman, adicionan y derogan diversas disposiciones de la Ley General de Salud y de la Ley de los Institutos Nacionales de Salud. November 29, 2019. [accessed September 8, 2021]. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5580430&fecha=29/11/2019.

- Reich MR Restructuring health reform, Mexican style, Health Syst Reform 2020;6. 1–11. [accessed February 11, 2022] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epub/10.1080/23288604.2020.1763114?needAccess=true

- Cruz-Martínez A. Se han adherido al INSABI 24 entidades. La Jornada; February 12, 2020. [accessed May 2, 2022] https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/02/12/politica/004n1pol

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Decreto por el que se reforman, adiciona y derogan diversas disposiciones de la Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública Federal. November 30, 2018. [accessed November 30, 2021]. http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5545330&fecha=30/11/2018

- Tron Zuccher D, Melgoza Rocha A. Operación Desabasto: así se detonó la escasez de medicamentos. Impunidad Cero. February 2021. [accessed February 11. 2022] https://www.impunidadcero.org/articulo.php?id=146&t=operacion-desabasto

- Rodríguez A Compra de medicamentos para 2020 tiene riesgo de quedar desierta, alerta la consultora INEFAM. El Financiero; October 18, 2019. [accessed November 10, 2021] https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/empresas/compra-de-medicamentos-para-2020-tiene-riesgo-de-quedar-desierta-alerta-la-consultora-inefam.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Acuerdo por el que se delegan facultades a la persona titular de la Oficialía Mayor de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, en materia de compras consolidadas. [ accessed November 10, 2021] https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5575191&fecha=11/10/2019.

- Charvel S, Cobo F El responsable es el estado. Letras Libres 2021; 23. 26–29. [accessed February 11, 2022] https://letraslibres.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/dosier-cobo-mex.pdf.

- Rodríguez A Se retrasa proceso de compra de medicamentos del gobierno. El Financiero; December 16, 2019. [accessed November 10, 2021] https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/empresas/se-retrasa-proceso-de-compra-de-medicamentos-del-gobierno

- Melgoza-Rocha A La lucha por la vida: el drama de las familias frente al desabasto. Letras Libres 2021; 23. 16–21. [accessed February 11, 2022] https://letraslibres.com/uncategorized/la-lucha-por-la-vida-el-drama-de-las-familias-frente-al-desabasto.

- IMCO. Dictamen de reforma a la Ley de adquisiciones contiene importantes retrocesos en materia de excepciones a la licitación en el sector salud. IMCO; November 18, 2020 [Accessed February 1st, 2022] https://imco.org.mx/dictamen-de-reforma-a-ley-de-adquisiciones-contiene-importante-retroceso-en-materia-de-excepciones-a-la-licitacion-en-sector-salud.

- Animal P. Gobierno permitirá importación de medicamentos aunque no tengan registro sanitario en México. Animal Político; January 29, 2020. [accessed February 1st, 2022] https://www.animalpolitico.com/2020/01/gobierno-importacion-medicamento-china-india-desabasto.

- UNOPS. UNOPS apoyará las adquisiciones públicas de medicamentos en México. [ accessed November 10, 2021]. https://www.unops.org/es/news-and-stories/news/unops-to-support-national-medicine-procurement-in-mexico.

- Ibarra LG, Méndez J, Flores K A revolution in medicines procurement in Mexico: a discussion about the new UNOPS model; 20 Nov 2020. [accessed November 10, 2021]. https://geneva-network.com/event/a-revolution-in-medicines-procurement-in-mexico-a-discussion-about-the-new-unops-model.

- Vega A UNOPS abre proceso de licitación de medicinas; abasto iniciará en mayo de 2021. Animal Político. [ [accessed November 15, 2021]. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2020/12/unops-abrelicitacion-medicinas-abasto-2021.

- Cruz-Martínez A Concluye la licitación de medicamentos con 45% de las claves asignadas. La Jornada; June 15, 2021. [accessed November 15, 2021]. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/06/15/politica/012n1pol.

- Convoca C-MA INSABI a licitación pública de medicamentos. La Jornada; November 25, 2021. [accessed November 25, 2021]. https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2021/11/24/politica/publica-insabi-convocatoria-a-licitacion-publica-de-medicamentos.

- Hernández L Gobierno veta a principales proveedores de fármacos. El Economista; April 9, 2019. [accessed November 10, 2021] https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/empresas/Gobierno-veta-a-principales-proveedores-de-farmacos-20190409-0038.html.

- Staff F. Pisa, la empresa que causó la crisis por falta de medicamentos contra el cáncer. January 23, 2020. [accessed February 11, 2022] https://www.forbes.com.mx/pisa-la-empresa-que-causo-la-crisis-por-falta-de-medicamentos-contra-el-cancer.

- Maldonado M Zoe Robledo revive a distribuidoras vetadas por AMLO. El Universal; April 13, 2020. [accessed Feb 20, 2022] https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/opinion/mario-maldonado/zoe-robledo-revive-distribuidoras-vetadas-por-amlo

- Urrutia A, Muñoz AE Nueva empresa pública distribuirá medicinas. La Jornada; July 31, 2020. [accessed November 10, 2021] https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/politica/2020/07/31/nueva-empresa-publica-distribuira-medicinas-amlo-8577.html.

- Badillo D Distribución de medicamentos, un sistema dislocado. El Economista; July 18, 2021. [accessed November 15, 2021]. https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Distribucion-de-medicamentos-un-sistema-dislocado-20210718-0002.html.

- Jornada L. AMLO reclama a funcionarios del sector salud por falta de medicamentos. La Jornada; November 11, 2021. [accessed November 15, 2021]. https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2021/11/10/politica/amlo-a-gabinete-ya-no-hay-excusas-para-desabasto-de-medicinas.

- Universal E. AMLO analiza encargar a las Fuerzas Armadas la distribución de medicina. El Universal; November 23, 2021. [accessed November 23, 2021]. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/amlo-analiza-encargar-las-fuerzas-armadas-la-distribucion-de-medicinas.

- Guerrero C, Hernández E Militar encabezará reparto de medicinas. Reforma; November 30, 2021. [accessed November 30, 2021]. https://www.reforma.com/encabezara-militar-reparto-de-medicinas/ar2306639?v=7.

- Cámara de Diputados. Piden diputados del PAN al Inai obligar a la UNOPS a transparentar los procesos de compra de medicamentos y material médico ante desabasto. Notilegis. Nota No 1383. Dec 14, 2021. [accessed February 14, 2022]. https://comunicacionsocial.diputados.gob.mx/index.php/notilegis/piden-diputados-del-pan-al-inai-obligar-a-la-unops-a-transparentar-los-procesos-de-compra-de-medicamentos-y-material-medico-ante-desabasto#gsc.tab=0

- UNOPS. A Powerful Tool for Change. [ accessed Feb 17, 2022]. https://www.unops.org/news-and-stories/stories/a-powerful-tool-for-positive-change.

- Corral Y, Casteñada Prado A El desabasto de medicamentos existe y reconocerlo es el primer paso para solucionarlo. Nexos, October 28, 2021. [accessed November 15, 2021]. https://anticorrupcion.nexos.com.mx/el-desabasto-de-medicamentos-existe-y-reconocerlo-es-el-primer-paso-para-solucionarlo.

- Chávez V. Suman 30 entidades 4504 quejas por falta de medicamentos. El Financiero; July 25, 2021. [accessed January 25, 2022] https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/nacional/2021/07/26/suman-30-entidades-4504-quejas-por-falta-de-medicamentos.

- Corral Y and Casteñada Prado A. El desabasto de medicamentos existe y reconocerlo es el primer paso para solucionarlo. Nexos, October 28, 2021. [accessed October 28, 2021]. https://anticorrupcion.nexos.com.mx/el-desabasto-de-medicamentos-existe-y-reconocerlo-es-el-primer-paso-para-solucionarlo.

- Tron Zuccher D, Megloza Rocha A. Operación Desabasto. Así se detonó la escasez de medicamentos. Impunidad Cero, February 2021, pp. 32–33. [Accessed November 11, 2021]. https://www.impunidadcero.org/articulo.php?id=146&t=operacion-desabasto.

- Vega A Padres de niños con cáncer protestarán en el aeropuerto cada martes mientras haya desabasto de medicamentos. Animal Político; November 9, 2021. [accessed January 25, 2022] https://www.animalpolitico.com/2021/11/padres-ninos-cancer-protesta-desabasto-medicamentos.

- Garduño R Acusa AMLO a opositores de protestas de padres de niños con cáncer. La Jornada; November 25, 2021. [accessed January 26, 2021] https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2021/11/25/politica/acusa-amlo-a-opositores-de-protestas-de-padres-de-ninos-con-cancer.

- INEGI. Encuesta Nacional de Ingreso y Gasto de los Hogares 2020 (ENIGH). Presentation July 28, 2021. [accessed September 9, 2021]. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/enigh/nc/2020/doc/enigh2020_ns_presentacion_resultados.pdf

- Llanos Guerrero A, Méndez Méndez JS Interrupción de los servicios de salud por Covid-19: implicaciones en el gasto de bolsillo. Ciudad de Mexico: Centro de Investigación Económica y Presupuestaria; August 13, 2021. [accessed February 12, 2022]. https://ciep.mx/IX9Q.

- El Universal. Falta de medicamentos oncológicos, cuestión de vida o muerte: madres de familia. El Universal; June 30, 2021. [accessed September 9, 2021] https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/ninos-con-cancer-falta-de-medicamentos-oncologicos-cuestion-de-vida-o-muerte-madres-de.

- Bookwalter CM Drugs shortages amid the Covid-19 pandemic. US Pharmacist; February 12, 2021. [accessed May 4. 2022] https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/drug-shortages-amid-the-covid19-pandemic.

- Arista L AMLO: la SFP se encargará de las compras consolidadas y auditor secretarías. [ accessed May 1st, 2022] https://politica.expansion.mx/presidencia/2021/07/29/amlo-la-sfp-se-encargara-de-las-compras-consolidadas-y-auditar-secretarias

- Fundar. Presupuesto para el sector salud en tiempos de Covid-19. [accessed May 2, 2022]. https://fundar.org.mx/pef2022/presupuesto-para-el-sector-salud-en-tiempos-de-covid-19.

- El Ceo. Lanza IMSS Bienestar nuevo programa de salud para personas sin seguro social; March 15, 2022. [accessed April 30, 2022]. https://elceo.com/politica/lanzan-imss-bienestar-nuevo-programa-de-salud-para-personas-sin-seguridad-social/

- Vargas V, Rama M, Singh R Pharmaceuticals in Latin America and the Caribbean: players, access, and innovation across diverse models. Technical Report [ accessed February 11, 2022] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358103501_Pharmaceuticals_in_Latin_America_and_the_Caribbean_Players_Access_and_Innovation_Across_Diverse_Models.