ABSTRACT

India has recently implemented several major health care reforms at national and state levels, yet the nation continues to face significant challenges in achieving better health system performance. These challenges are particularly daunting in India’s poorer states, like Odisha. The first step toward overcoming these challenges is to understand their root causes. Toward this end, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health conducted a comprehensive study in Odisha based on ten new field surveys of the system’s performance to provide a multi-perspective analysis. This article reports on the assessment of the performance of Odisha’s health system and the preliminary diagnosis of underlying causes of the strengths and challenges. This comprehensive health system assessment is aimed toward the overarching goals of informing and supporting efforts to improve the performance of health systems in Odisha and other similar contexts.

Introduction

India has implemented several major health care reforms at national and state levels over the last two decades. Yet, the nation continues to face significant challenges in achieving better health system performance. These challenges are particularly daunting in India’s poorer states, such as Odisha, where the challenges are exacerbated by widespread poverty, difficult geographical terrain, proneness to natural calamities, and a high proportion of vulnerable populations.

Over the past three years, the India Health System Project at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health has conducted a comprehensive health system assessment, with the overarching objective to inform and support efforts to improve Odisha’s health system. The project seeks to suggest reforms that can assure affordable and equitable access to quality care for the state’s population while avoiding major financial risk and improving citizen satisfaction. Its findings are also relevant for other states in India’s Empowered Action Group (EAG),Footnotea which make up the majority of the country’s poor population.

This project has conducted a comprehensive empirical analysis of the performance of Odisha’s health system from multiple perspectives. Here, we report on two components—an assessment of the performance of Odisha’s health system and our preliminary diagnosis of underlying causes of its strengths and challenges—based on ten new surveys.

Our Analytical Approach

In our analysis, a health system is understood as a means to an end ().Citation1 We use the Control Knob Framework as the analytical approach for this paper. The framework is based on a set of relationships in which certain structural components (the means) and their interactions are connected to the goals the health system intends to achieve (the ends). The means—comprised of five policy areas or “control knobs” are health financing, strategic purchasing and provider payments, organization of the delivery system, regulation, and persuasion—lead to the ends: three intermediate goals and three final goals. The final goals are health status, financial risk protection, and citizen satisfaction, and the intermediate goals are access, quality, and efficiency. For all goals, we are concerned about both level of performance (compared to various benchmarks) and distributional issues (equity dimensions).

Materials and Methods

The Health System of Odisha

The state of Odisha in eastern India has a population of over 41 million and is predominantly rural (83.3%).Citation2 With 32.6% of people living below the poverty line (BPL),Citation2 Odisha is among India’s six most impoverished states with very low developmental indices. Odisha is home to many vulnerable social groups, including a large tribal (indigenous) population base, constitutionally known as the Scheduled Tribes (ST), and historically disadvantaged castes or the Scheduled Castes (SC).Footnoteb In addition, health expenditure has remained low (around $46 per capita or Rs. 2,949) compared to other Indian states, and with about 76% of total health expenditure (THE) paid by individuals, as out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE), one of the highest in India.Citation3 These factors combine to create significant challenges for Odisha to provide equitable health care services to its citizens.

As with other states in India, Odisha has a pluralistic health system where a range of formal and informal providers in both the public and private sectors deliver health care. The public sector facilities are funded and run by the state’s and central government’s department of health. These public sector facilities include Sub-Centers, Health and Wellness Centers (HWCs), and Primary Health Centers (PHCs) for primary care delivery, and Community Health Centers (CHCs), Sub-divisional Hospitals, District Hospitals, and Medical College Hospitals for secondary and tertiary care. The private sector is heterogeneous and includes a range of providers (super-specialty hospitals with highly-skilled doctors, charitable hospitals and clinics, doctors with small individual practices [or solo providers], traditional healers, and private pharmacies). In addition, outpatient and primary health care are provided by outpatient departments of public and private sector secondary and tertiary hospitals.

Odisha has implemented a series of important health policies in the last two decades, including both federal and state initiatives, notably: (1) the federal National Health Mission (NHM) of 2005, which is the umbrella program of the Indian government for public health system strengthening, (2) the federal Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Center (HWC) program of 2018, which aims to expand the scope of primary health care and set up new health facilities (mostly updated and repurposed Sub-Centers and Primary Care Centers), (3) the state Biju Swasthya Kalyan Yojana (BSKY) of 2018, which is a tax-financed universal insurance scheme for hospitalization, (4) the state Niramaya scheme (2015), which seeks to provide free drugs at public sector hospitals and improve supply-chain management through information technology, and (5) the state Nidan scheme (2018), which aims to provide free diagnostic services to patients at public health facilities.

Methodology

Our assessment of Odisha’s health system is based on ten new comprehensive surveys () that collected data from a wide range of stakeholders: 30,654 individuals across 7,567 households, 1,485 patients, and 554 public and private sector facilities, across different levels of care, including hospitals, nursing homes, and primary care facilities, as well as 1,124 individual providers, with 794 providers at facilities and 685 providers engaged in solo practice, and 1,035 private pharmacies.Citation4 Triangulating findings across the surveys enabled us to understand health system performance from multiple perspectives with reliable, up-to-date data. We also used existing data on Odisha from the National Sample Survey (NSS), National Family Health Survey (NFHS), and Sample Registration System (SRS) reports to validate and enhance our findings.

Table 1. The ten Odisha health system surveys.

Combining these ten surveys in one study allows us to:

Link demand-side and supply-side perspectives: Most large-scale datasets in India focus only on household (demand) data. Our study includes public and private providers (supply), which allows linking household utilization data to the characteristics of providers.

Provide more comprehensive understanding of the private health sector: The combination of surveys allowed us to collect data from multiple categories of private sector providers in Odisha (including hospitals, nursing homes, chemist shops, and providers engaged in solo practice).

Collect geospatial data to allow market analyses: We collected geospatial data on where users and providers are located, whether providers are clustered in certain locations, and if users bypass their nearest providers. This allowed analyses of market behavior.

Assess quality and effectiveness: Our surveys in Odisha systematically examined citizen satisfaction, with patient experiences collected at outpatient and inpatient exit interviews across all levels of health care providers. This allowed us to assess three aspects of health care quality: patient safety, patient-centeredness, and clinical effectiveness.

Results

In this section, we report the results from our analysis of data from the different surveys, as well as secondary data in some cases. For each health system goal, we indicate the surveys and datasets used in the analysis. Most of the results presented in this paper are based on household survey data, although we also present some analysis of the provider surveys and patient interview data.

Final Health System Goals

We begin with our findings on the three final goals of Odisha’s health system: health status, financial risk protection, and citizen satisfaction.

Health Status: Final Goal #1

The first goal of a health system is to improve the population’s health status.Citation1 Our analysis of this goal is based on secondary data. Existing data show that Odisha has made notable advances in health status in recent years.Citation5–7 The state’s infant mortality rate (IMR) has reduced dramatically, from 112 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1992–93 to 36 in 2019–21.Citation5,Citation7,Citation8 The state also achieved one of the faster declines in maternal mortality compared to India’s seven other EAG states, with a decrease in maternal mortality rate (MMR) from 235 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010–12 to 168 in 2015–17.Citation5,Citation7–9 Although Odisha has the highest incidence of malaria in the country, the state has seen a steep decline—of more than 80%—in malaria cases between 2017 and 2019.Citation10

Several health status indicators, however, continue to be major warning signals in the state. For example, Odisha’s improved IMR (36) compares poorly to the national average of 30 and is above the IMR in other EAG states, including Bihar (27), Jharkhand (30), and Rajasthan (35).Citation5 Similarly, Odisha’s MMR (168) is higher than the national average (113) and many other states.Citation5 While mortality rates associated with infectious diseases—such as diarrheal diseases, drug-susceptible tuberculosis, and malaria—have declined over the last two decades in Odisha, the rates are still the highest among the EAG states.Citation6 Odisha also faces a growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). More than half of deaths in the state are currently caused by NCDs, especially cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.Citation6

Odisha also confronts important inequities in different health status outcomes among certain population sub-groups: rural residents, people belonging to STs and SCs, and households in lower wealth quintiles.Footnotec These sub-groups experience lower life expectancy and higher rates of morbidity and infant and maternal mortality.

Financial Risk Protection: Final Goal #2

Financial risk protection is the extent to which households are protected from economic hardship associated with paying for health care. We assessed financial risk protection in Odisha with our survey of 7,567 households (Survey 1 in ).

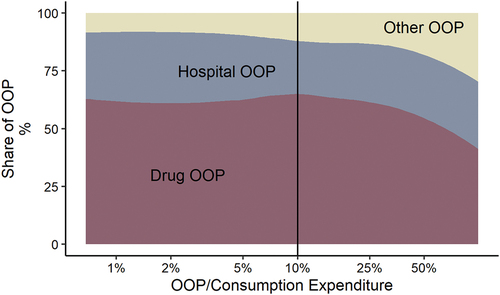

We found that 24% of Odisha’s households incur Catastrophic Health Expenditures (CHE), defined as OOPE that exceeds 10% of their consumption expenditure, and 12% of the households faced impoverishment due to payment for OOPE. 65% of CHE was due to purchases of medicines (). Outpatient care and spending on medicines constitute a large proportion of OOPE (69%) and 32% of inpatient care. Expenditure on diagnostic tests and doctor fees together account for less than 10%, while 69% of outpatient care OOPE are on medicines.

A disaggregated analysis of the high OOPE on drugs shows that a remarkable 86% of outpatient users purchased drugs from private pharmacies. Even among those who chose the public sector as the first point of contact for outpatient services, 72% reported purchasing drugs from private pharmacies afterward. Drug purchases from private pharmacies accounted for 41% of OOPE among inpatient users, even though these expenses are theoretically included in the BSKY benefits package, and Odisha’s Niramaya Scheme specifically provides free drugs in public sector hospitals ().

Table 2. Out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on drugs by type of care and type of provider.

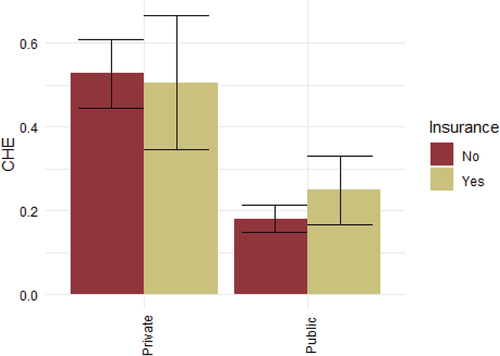

In terms of insurance coverage, only 14% of households reported having any insurance coverage. Further, 4% of our household survey respondents hospitalized in public facilities and 9% of those hospitalized in private facilities used health insurance to pay for expenses. Our survey found CHE rates were 52% and 19% for hospitalizations in private and public hospitals, respectively. Although hospital care is supposed to be free under BSKY, CHE rates for hospitalizations were not statistically significantly different when the patient reported using insurance versus not (), indicating that insurance is not effectively protecting hospitalized people from financial risk in Odisha.

Citizen Satisfaction: Final Goal #3

Citizen satisfaction is the degree to which citizens—not just patients—are satisfied with the health system. Our study uses data from our household survey (Survey 1 in ) to assess citizen satisfaction and its correlates, including the place of residence, income and education levels, social group, insurance coverage, health service utilization, and choice of providers.

We found widespread citizen dissatisfaction with the health system in Odisha overall and an expressed desire for improvement. 56% of our respondents expressed a need for major changes to the health system, and an additional 33% reported that the health system needs to be completely rebuilt. Overall, 91% of households considered it “very important” to improve the health system, although 57% of the people were “very confident” about receiving treatment from the health system if they fell ill.

The health system aspects that received the highest satisfaction ratings were linked to physical access and availability of services. On average, between 66% and 72% of people reported high satisfaction with their provider’s location, hours of operation, the ability to choose providers, and availability of drugs and diagnostics at hospitals. Conversely, the lowest satisfaction ratings were for treatment expenses for hospitalization, with 36% of people reporting poor satisfaction with the cost of hospital treatment.

In terms of factors associated with citizen satisfaction, we found that households with insurance reported higher satisfaction with the health system than those that did not have coverage. Households that had a health care visit during the last year before the survey reported lower satisfaction levels with the health system than those who had not used health services in the recent past. In terms of socio-demographic characteristics, we did not see very significant gradients in citizen satisfaction levels across income and education levels, although women, people in ST groups, and those in rural areas reported lower satisfaction with the health system than men, people in non-tribal groups, those in urban areas, respectively.

Intermediate Health System Goals

Our analysis of Odisha’s health system considered three intermediate outcome goals: access, quality, and efficiency. These intermediate outcomes can be directly influenced by policy reforms and can help drive performance improvements in the final goals discussed above.

Access: Intermediate Goal #1

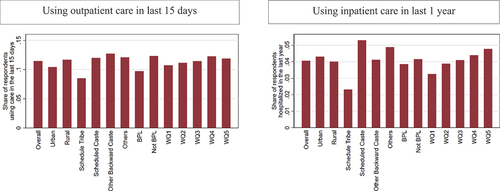

We measured “access” by self-reported visits to health care providers for outpatient and inpatient care. We used data from our household survey to analyze access to health services (Survey 1 in ).

Our study confirmed other reports that people in Odisha have ready access to care. Nearly 90% of people who were ill in the last two weeks prior to our survey sought care from a health care provider, either public or private. Regarding physical availability of health services, most households in our survey reported living within 30 minutes of a public facility: 94% for a Sub-center, 82% for a PHC, and 58% for a CHC.

We found various limitations in the availability of medicines. Only 18% of select essential drugs, based on the Indian government’s National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM), were available at Sub-Centers and 38% at PHCs—versus 48% at private pharmacies. While public sector hospitals had better stocks (73%) than private sector hospitals (59%) and lower-level facilities, stocks were far from complete in most facilities.

Private sector providers play a significant role in access to outpatient care. We found that most households (54%) sought outpatient care from the private sector (a heterogeneous category that includes various kinds of providers).Footnoted Out of these, 16% sought care from private pharmacies. Seeking care at private pharmacies was common across households; we found no noticeable differences across wealth quintiles and social groups.

Another key finding on access is the role of hospitals in providing outpatient care. For example, of the 46% of households who sought outpatient care in the public sector, 33% reported going to public primary care facilities, and 13% went to outpatient departments at public hospitals.

Other data sources have shown that Odisha has made notable improvements in the utilization of “essential” health services, including full basic immunization among children, antenatal care (ANC), and institutional deliveries.Citation7 Our survey results confirm that this positive trend continues: for example, we found that 67% reported having at least four ANC visits among recently pregnant women in our sample.

Our analysis found that wealthier households used more care than less wealthy households. We also found similar gradients in antenatal care use by women from different wealth quintiles and among ST populations compared to other social groups ().

Quality: Intermediate Goal #2

Our study assessed health care quality using three core concepts: clinical effectiveness, patient safety, and patient-centeredness.

Clinical effectiveness: Clinical effectiveness is the provision of health services based on scientific knowledge, including avoiding the overuse of inappropriate care and underusing effective care. Clinical effectiveness is determined by measuring the extent to which a diagnosis or treatment is based on evidence or standard guidelines and its influence on clinical outcomes.

Clinical effectiveness is usually assessed through one of three methods: chart reviews, standardized patients, or clinical vignettes. A few studies in India have used standardized patients and vignettes to assess clinical effectiveness.Citation11,Citation12 However, our literature review did not find any published studies from Odisha. Our study, therefore, represents an important addition to knowledge about the clinical quality of health care in Odisha.

We used vignettesCitation13 to interview primary-care level providers in public and private sectors on five illness conditions—tuberculosis, childhood diarrhea, pre-eclampsia, heart attack, and asthma—and evaluated their responses against clinical guidelines through 550 unique interactions. The public sector providers were those at government-run PHCs, and the private sector providers included those engaged in solo practice, irrespective of medical qualifications. We examined differences among providers on three parameters: competence to make a correct diagnosis, knowledge of the diagnostic process, and competence to provide the correct treatment. Additionally, we analyzed prescription patterns among providers at the primary level.

We found that both public and private providers had poor competence, often making wrong diagnoses and giving incorrect and unnecessary treatments, potentially harming patients. Only 58% of providers made a correct diagnosis across the five illness conditions in our vignettes (). We found that provider competence to diagnose and treat conditions across public and private sectors was poor. In most cases, providers did not prescribe the right treatment as recommended by clinical guidelines. Across the different conditions, only 2.2% of providers prescribed the correct treatments without any unnecessary drugs. Not a single provider in our study prescribed the full-recommended treatment for pre-eclampsia, heart attack, and asthma (). An average of 40% of providers prescribed only unnecessary or incorrect drugs across the five vignette conditions, for example, antibiotics for heart attack or pre-eclampsia or antacids and painkillers for tuberculosis, pre-eclampsia, and asthma ().

Table 3. Competence of providers at the primary care level to diagnose and treat conditions.

Patient Safety: The safety of patients is a critical component of quality that has important consequences for health system performance. Patient safety culture is “the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization’s health and safety management.”Citation14 Yet, patient safety and its consequences are barely studied in India.

Higher patient safety culture scores are statistically associated with better patient outcomes and decreased adverse events in hospitals.Citation15 Adverse events (injuries that result from medical care) can include both errors (for example, administration of the wrong drug to a patient) as well as events that may be less easily prevented (such as an allergic reaction to a medicine).

We examined patient safety culture in Odisha’s public hospitals with a validated analytical tool, the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPS).Citation16 We interviewed 2,687 patient-facing staff members (physicians, nurses, paramedics, and hospital management staff) in nine public sector hospitals (Survey 9 in ). A limitation of our sample was that we could not undertake safety audits in the private sector, as we did not receive informed consent from any private sector hospital.

We found significant problems with patient safety culture in Odisha’s public hospitals. There was a lack of monitoring systems for routine collection of data on medical errors in public hospitals. Almost no patient safety events were reported in any of the hospitals surveyed. In some facilities, over 90% of respondents reported never submitting an event report. Across public hospitals, on average, only 12% of staff had ever reported an event, compared to an average of around 45% in high-income countries. Because hospitals are not reporting safety events, it is impossible to know how much harm is caused by unsafe services in Odisha’s inpatient settings—and, in turn, it is not possible to address that harm.

Patient-Centeredness: Patient-centered care is health care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and allows patients to help guide clinical decisions.Citation17 Studies show that patient satisfaction is associated with a higher quality of care and better health outcomes.Citation18–20 In addition, when patients have negative care experiences, they are more likely to delay seeking necessary medical care and are at higher risk of not adhering to treatment recommendations.Citation21,Citation22

To date, Odisha lacks studies on patient satisfaction or databases with information on patient experiences and characteristics. As a result, little is known about how patient characteristics affect experience or satisfaction with care in the state.

The data for this assessment come from interviews with 1,485 patients in two surveys (Surveys 7 and 8 in ). The first was an exit survey with 507 patients receiving inpatient care in five hospitals across Odisha. We adapted the Hospital Survey on Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health care Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) tool for this survey.Citation23 The second was an exit survey with 978 patients receiving outpatient care at a range of public and private sector providers, including outpatient departments of hospitals and nursing homes, CHCs, PHCs, and solo providers.

In both inpatient and outpatient settings, patients with no formal education and those belonging to SC or ST groups received the lowest quality of interpersonal treatment as assessed through objective care experience measures. We found that, within the same facility, more-educated and higher-caste patients reported significantly higher interpersonal treatment from providers. Patients from ST groups were 14% points less likely to report being treated with dignity and respect than patients from other social groups.

Efficiency: Intermediate Goal #3

An efficient health system is one in which the inputs allocated to produce health outcomes are used optimally without wastage. “Technical” efficiency refers to using the least possible inputs to produce a given amount of health output. “Allocative” efficiency captures whether inputs are allocated among the production of different health outcomes in a way that maximizes societal health. Simply put, technical efficiency is about “doing things the right way,” while allocative efficiency focuses on “doing the right things.”Citation24

Some prior work has examined efficiency in the Odisha health system using public sector data. These studies, however, have examined only a narrow set of inputs in public health facilities, with a focus on technical efficiency and using complicated statistical analysis, making the results difficult to use in practice.Citation25–31 Our study, on the other hand, includes surveys that cover various kinds of providers and facilities and uses a set of ratio-based indicators to provide a more complete understanding of factors that affect health system inefficiencies, both technical and allocative, in Odisha.

The data for our assessment of health system efficiency in Odisha came from four surveys: two facility surveys that included 554 public and private sector facilities (in , Survey 2 of hospitals and CHCs, and Survey 3 of primary care facilities) and two individual provider surveys covering 1,124 providers (in , Survey 4 of providers in a facility and Survey 5 of solo providers).

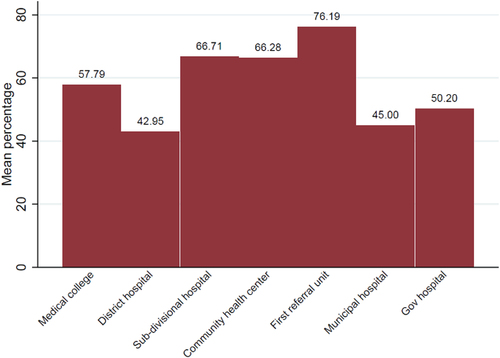

We found latent capacity in the public sector facilities, which could be a source of technical inefficiency.Footnotee Physicians working in PHCs spend an average of 617 minutes (10 hours) per week on nonclinical tasks, based on their self-reported time spent per patient, the number of patients seen, and days/hours worked per week. Physicians in public secondary and tertiary care hospitals reported spending only about 6 minutes per outpatient, with a slightly higher reported time spent per outpatient for physicians at PHCs (9 minutes). In addition, we found latent capacity in hospital bed occupancy, which could be another source of inefficiency. The mean occupancy rate at public secondary and tertiary care facilities is below the recommended 80%, except for one public Medical College Hospital ().

Figure 5. Mean bed occupancy rate in public health care facilities.

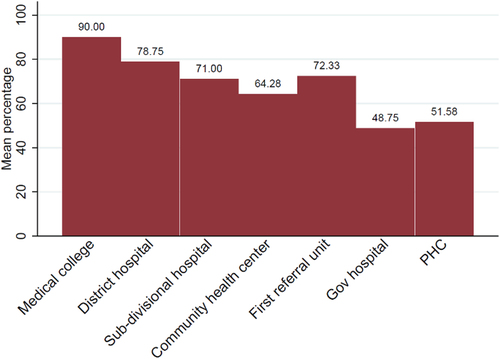

We found technical inefficiencies in the use of health care resources in the public system in Odisha, related to staff limitations. While between 81% and 89% of sanctioned positions were filled for certain categories of health care workers (such as nurses, paramedics, and mid-level providers), the shortages were much higher for doctors; only 65% of sanctioned posts were filled for general physicians and 56% for specialists. From an allocative perspective, there is a sub-optimal mix of trained nurses and allopathic doctors in public health care facilities, with a mean doctor-to-nurse ratio of 1:1.43, which is less than the recommended ratio of 1:2,Citation32 likely due to the shortage of physicians in the public sector compared with a lack of shortage of other cadres of health care workers ().

Figure 6. Mean percentage of sanctioned doctors positions filled in public health care facilities.

Discussion

A significant contribution of this study is its comprehensive health system assessment using the Control Knob Framework. We analyze a single case study of the state of Odisha, but the case illustrates problems found in similar resource-poor settings in other states of India and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). While the generalizability of our findings, as with all case studies, requires additional analysis and verification, this study’s use of the Control Knob Framework for doing a comprehensive health system assessment provides a good example of the strengths of this approach and how it could be done for other health systems.Citation1

Our main findings of this study indicate that despite several positive developments and commendable efforts to improve health system performance, Odisha still faces significant performance challenges in its health system. Below we present some preliminary diagnoses of the underlying causes of the three key challenges of Odisha’s health system, according to our assessment: poor financial risk protection, poor quality of care, and low citizen satisfaction. These diagnoses have important implications for considering possible reform options to improve Odisha’s health system performance, although we do not explore these options in this paper due to limitations in space.

Potential Reasons Behind Poor Financial Risk Protection

Our study confirmed existing data to show that financial risk protection in Odisha is worse than in other Indian states, including other EAG states. Our analysis found that the major drivers of catastrophic health expenditure in Odisha are spending on outpatient care in both public and private sectors and on medicines from the private sector, and the lack of adequate insurance coverage for these expenditures. These are ongoing problems across India, as reported in the existing literature.Citation33

The first major reason for poor financial risk protection is that most Odisha residents (54%) seek outpatient care from the private sector, particularly private pharmacies and solo practitioners (both qualified and unqualified), rather than from public sector primary health care facilities (PHCs, Sub-Centers, and HWCs). As stated in existing literature, households chose private sector facilities because of the inconvenient locations and operating hours of public sector facilities, lower stocks and perceived lower quality of drugs at these facilities, lack of respect from public sector providers, and poorer infrastructure.Citation34–37 Our survey found that even when people seek care at public sector facilities, more than 70% buy their medicines from private pharmacies, possibly due to the poor availability of drugs at public sector facilities.

Our results show that the availability of essential medicines is a challenge across the public sector facilities, especially at the primary care level. These findings suggest that improving drug supplies and quality could help increase the utilization of public sector primary care facilities. By triangulating data from our provider surveys and existing literature, we suggest two main possible explanations for these drug shortages. First is the structure of the essential drug list (EDL), which still mainly includes medicines for communicable diseases, while the highest burden of morbidities in Odisha is from NCDs.Citation35,Citation38 Second is the occurrence of supply chain problems, such as delays in requests for drugs sent by health facilities to the Odisha State Medical Corporation (OSMC), the state’s drug procurement agency, and delays by the OSMC in fulfilling these supplies.Citation39

Other factors also influence the purchase of medicines in the private sector. Many people purchase drugs from the private sector in Odisha, because of the role of provider incentives. As others have reported, public sector providers might send patients to private pharmacies where they have financial interests, either through ownership or receiving commissions on sales.Citation40 In addition, patients’ preferences and perceptions could also contribute to purchases of medicines from private pharmacies. This is supported by literature showing that individuals in India prefer to purchase drugs from private pharmacies due to perceptions of a better quality of branded drugs in private shops compared to generics found in public facilities.Citation40–42

The second major reason for poor financial risk protection is the limited risk-pooling mechanisms in Odisha to protect households from the costs of non-hospital care and medicines (the main sources of OOPE). Existing government health insurance programs (like the state’s BSKY program) do not cover outpatient services or medicines outside hospitalizations. Instead, government subsidies prioritize hospitalization rather than outpatient and primary care. In addition to not providing financial risk protection for non-hospital care and medicines, this approach is also an inefficient allocation of resources, since outpatient and primary care are more cost-effective.

Potential Causes Behind Poor Quality of Care

Our study explored three important sources of poor quality of care in Odisha’s health system: low provider competence in diagnosing common conditions, low provider knowledge of corresponding and appropriate treatments, and a clinical culture that appears to discourage candid and routine error reporting. The findings have implications for the provision of high-quality care and for ratings of patient satisfaction, especially among vulnerable groups.

By triangulating data from our provider surveys with the clinical vignettes, we identified several possible factors that may contribute to poor technical competence among health care providers in Odisha: inadequate training, limited regulation, lack of mandatory treatment guidelines in Odisha, and a lack of incentives to provide high-quality and rational care.Citation43 Similar findings on clinical quality and provider characteristics have been reported from other states in India.Citation44,Citation45

Poor clinical quality of care contributes to poor health outcomes from treatment, which can lead to increased morbidities and mortalities. They also have serious consequences for the wastage of scarce resources, both for individual households and for the health system, which is especially important in resource-limited settings. These findings, combined with the results on high financial risk imposed by spending on drugs, show that people are spending a lot of money on care of low or little value to their health. Poor clinical effectiveness and patient safety cultures at hospitals can increase the severity or the spread of disease and contribute to both technical and allocative inefficiencies in health systems. As Odisha expands access to care through programs like BSKY and Ayushman Bharat HWC, it will be important to implement measures that improve health care quality, provider competence, and patient safety to ensure that the tax resources purchase high-value care.

Potential Causes Behind Low Citizen Satisfaction

Our assessment of citizen satisfaction shows that an overwhelming majority of the public perceives the need to improve Odisha’s health system. Our finding that satisfaction levels were relatively high for aspects related to physical access to care are congruent with our result that around 90% of the households in Odisha seek treatment when ill, and a majority of them live within proximate distance of a health provider.

The high level of dissatisfaction in Odisha is perhaps driven by people’s experiences of how the health system performs and the problems identified in our assessment: poor quality of care, low financial risk protection, and inequities in health services. Although the physical availability of health facilities has improved significantly,Citation46 our survey found measurable inequity in access to services for the poor, rural, and SC and ST populations, as mentioned above in the Results.

Our findings about low levels of citizen satisfaction with Odisha’s health system are particularly relevant for policy makers and politicians, as the low levels of satisfaction may reflect public opinion about government institutions and the political administration in the state. Low citizen satisfaction could eventually lead to an erosion of trust in the health system and a decrease in health-seeking behaviors.Citation47,Citation48 Our findings could be a good barometer of the public’s views on the achievements and limitations of the state’s health reforms undertaken in recent years, and thus could help guide future reforms.

Conclusion

This article presents key findings from the Odisha Health System Assessment Study, based on data from ten surveys with households, patients, and providers. The study was designed to address critical gaps in existing data, expand knowledge, and deepen understanding by undertaking a comprehensive assessment of the performance of Odisha’s health system in order to help shape future reforms.

Our findings demonstrate that Odisha’s health system has made some important achievements in recent years but continues to face significant challenges in assuring affordable and equitable access to quality health care for its population. Our analysis of this assessment also points to possible causes for the identified performance problems. Our findings can be used by policy makers to design future reforms to improve the performance of Odisha’s health system on its intermediate and ultimate goals. Continuing to study the state’s performance is also important, as these findings have important implications for Odisha, other states across India (especially the EAG), and other LMIC countries facing similar challenges.

Ethical Approval

Data were collected between August 2019 and March 2020 by an independent data collection agency. Informed consent from all participants was obtained before the interviews. Three different IRB approvals were received for this study: the IRB at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (IRB18–1675), an independent IRB in India to meet domestic requirements, and the health Research and Ethics Committee of the Directorate of Health Services, Government of Odisha (60/PMU/187/17).

Informed consent from participants

Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent for all ten surveys used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Tata Trust. We are grateful to the Government of Odisha for their support and encouragement for undertaking this assessment of the state’s health system and for granting us the necessary permissions for this study. We express our heartfelt thanks to the thousands of people in Odisha who participated in this study and generously responded to our surveys. Without their cooperation, this study would not have been possible. We gratefully acknowledge the consultations with our partner organizations, the Health Systems Transformation Platform and the Indian Institute of Public Health-Bhubaneshwar. Their advice and guidance were invaluable. We thank the team at Oxford Policy Management who collected and cleaned the data for this study. The authors thank our team of research assistants, Deepika Dilip, Alex Gachanja, Benjamin Gelman, Neha Gupta, Elaine He, Joanne Hokayem, Tejal Patwardhan, Alison Ross, and Brian Zhou; and collaborators at the Ariadne Labs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

a. India has identified eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states, which are recognized as socioeconomically less developed, including high infant mortality rates and delayed demographic transitions. These EAG states include: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttaranchal and Uttar Pradesh, along with Odisha. The group of EAG states provides an important benchmark for assessing Odisha’s health system performance.

b. The Scheduled Caste (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are officially designated groups recognized in the Constitution of India. Nationally, the SCs and STs comprise about 16.6% and 8.6%, respectively, of India’s population (according to the 2011 census). The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 lists 1,108 castes across 29 states in its First Schedule, and the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950 lists 744 tribes across 22 states in its First Schedule. The Constitution lays down the general principles of positive discrimination for SCs and STs.

c. Our study measured wealth quintiles based on a principal component analysis of assets and conditions of housing and infrastructure. Similar measurements are used by India’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS) and the global Demographic and Health Survey (DHS).

d. The discrepancy between our findings and the NSS that reports a lower percentage of households seeking private-sector outpatient care is primarily because our survey considered private pharmacies as an explicit provider category and measured care-seeking from private pharmacies, unlike in the NSS.

e. Our finding on latent capacity needs to be interpreted in the light of existing evidence from India that clinical staff spend a sizable proportion of their time on administrative tasks. This is inefficient use of physician time, as it could be potentially spent on patient care instead. These inefficiencies assume even more significance, given the shortages of doctors in Odisha, the high patient volumes, and the short consultation times that we found in our study.

References

- Roberts MJ, Hsiao WC, Berman P, Reich MR. Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- Registrar General of India. Census of India. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 2011.

- NSSO. Key indicators of household consumption on health in India (NSS 75th Round). National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India; 2019.

- India Health Systems Project. Odisha Health System Assessment: study design and methodology Working Paper. USA: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2020.

- SRS. Sample Registration Survey. New Delhi: Government of India; 2019.

- ICMR, PHFI, IHME. India: health of the nation’s states – the Indian state-level disease burden initiative in the Global Burden of Disease Study; 2017. https://www.healthdata.org/

- IIPS. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019-21. Mumbai: IIPS; 2022.

- IIPS. National Family Health Survey of India – I, 1992-1993. In: International Institute for Population Studies; 1994.

- Ali SC Odisha improves child & maternal health, progresses faster than other poor States. https://wwwindiaspendcom/, 2019.

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization 2019.

- The World Bank. Medical Advice Quality and Availability in Rural India (MAQARI); 2003.

- Bihar Evaluation of Social Franchising and Telemedicine (BEST). Bethesda: ClinicalTrials.gov, National Library of Medicine; 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01345695

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–13. doi:10.1001/jama.283.13.1715.

- ACSNI. ACSNI Study Group on Human Factors Organising for Safety. London: HMSO; 1993.

- DiCuccio MH. The relationship between patient safety culture and patient outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2015;11(3):135–42. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000058.

- AHRQ. Surveys on Patient Safety Culture (SOPS) Hospital Survey https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/surveys/hospital/index.html. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2004.

- IOM. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2–8. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765.

- Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, Landon BE. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):1024–40. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01122.x.

- Wang DE, Tsugawa Y, Figueroa JF, Jha AK. Association between the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital star rating and patient outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):848–50. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0784.

- Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Affleck G, Barrows E, ZuWallack R. Adherence with twice-daily dosing of inhaled steroids: socioeconomic and health-belief differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(6):1810–17. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9712007.

- Ruiz-Moral R, Pérula de Torres LÁ, Jaramillo-Martin I. The effect of patients’ met expectations on consultation outcomes. A study with family medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):86–91. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0113-8.

- CMS, AHRQ. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2002. https://hcahpsonline.org/

- Yip W, Hafez R. Improving Health System Efficiency: reforms for improving the efficiency of health systems: lessons from 10 country cases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Shetty U, Pakkala TPM. Technical efficiencies of healthcare system in major states of India: an Application of NP-RDM of DEA Formulation. J Health Manag. 2010;12(4):501–18. doi:10.1177/097206341001200406.

- Purohit BC. Health care system efficiency: a sub-state level analysis for Orissa (India). Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies. 2016;28(1):55–74. doi:10.1111/rurd.12044.

- Hota AK, Rout HS. Health Infrastructure in Odisha with Special Reference to Cuttack and Bhubaneswar Cities; 2016. http://dxdoiorg/101177/0974930615617275.

- Hussain MA, Dandona L, Schellenberg D. Public health system readiness to treat malaria in Odisha State of India. Malar J. 2013;12(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-351.

- Padhy GK, Padhy RN, Panigrahi SK, Sarangi P, Das S. Bottlenecks identified in the Implementation of components of national health programmes at PHCs of Cuttack district of Odisha. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3(4):271–77. doi:10.4103/2230-8598.123468.

- Swain TR, Rath B, Dehury S, Tarai A, Das P, Samal R, Samal S, Nayak H. Pricing and availability of some essential child specific medicines in Odisha. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47(5):496–501. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.165197.

- Patra SK, Ramadass M, Annam L. National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) & Health Status of Odisha. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2015;6(1):241–46. doi:10.5958/0976-5506.2015.00046.7.

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993: investing in Health, Volume1. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 1993.

- Selvaraj S, Farooqui HH, Karan A. Quantifying the financial burden of households’ out-of-pocket payments on medicines in India: a repeated cross-sectional analysis of National Sample Survey data, 1994–2014. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e018020. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018020.

- Kujawski SA, Leslie HH, Prabhakaran D, Singh K, Kruk ME. Reasons for low utilisation of public facilities among households with hypertension: analysis of a population-based survey in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(6):e001002. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001002. [published Online First: 2019/01/10].

- Haakenstad A, Kalita A, Bose B, Cooper JE, Yip W. Catastrophic health expenditure on private sector pharmaceuticals: a cross-sectional analysis from the state of Odisha, India. Health Policy Plan. 2022 August;37(7):872–84. doi:10.1093/heapol/czac035.

- Rao KD, Sheffel A. Quality of clinical care and bypassing of primary health centers in India. Soc Sci Med. 2018;207:80–88. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.040. [published Online First: 2018/05/08].

- Das J, Holla A, Mohpal A, Muralidharan K. Quality and accountability in health care delivery: audit-study evidence from primary care in India. Am Econ Rev. 2016;106(12):3765–99. doi:10.1257/aer.20151138. [published Online First: 2016/12/01].

- Bose M, Dutta A. Health financing strategies to reduce out-of-pocket burden in India: a comparative study of three states. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 3;18(1):830.

- Express News Service. CAG exposes chinks in the procurement of drugs, medical consumables in Odisha. The New Indian Express. 2021 Apr 3.

- Kotwani A, Ewen M, Dey D, Iyer S, Lakshmi PK, Patel A, Raman K, Singhal GL, Thawani V, Tripathi S, et al. Prices & availability of common medicines at six sites in India using a standard methodology. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125(5):645–54. [published Online First: 2007/07/24].

- Aivalli PK, Elias MA, Pati MK, Bhanuprakash S, Munegowda C, Shroff ZC, Srinivas PN. Perceptions of the quality of generic medicines: implications for trust in public services within the local health system in Tumkur, India. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2(Suppl 3):e000644. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000644. [published Online First: 2018/03/14].

- Sreenivasan M, Narasimha Reddy TL. A study on the purchase decision behavior of doctors in India with respect to perception on quality of generic drugs. Int J Curr Adv Res. 2018;7:15627–35.

- Kalita A, Gupta N, Woskie L, Yip W. Providers’ knowledge of diagnosis and treatment best practices for Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI): evidence from India using clinical vignettes. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(S2). 41–41. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13805.

- Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012 Dec;31(12):2774–84.

- Mohanan M, Vera-Hernández M, Das V, Giardili S, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Rabin TL, Raj SS, Schwartz JI, Seth A. The know-do gap in quality of health care for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia in rural India. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Apr;169(4):349–57.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Rural Health Statistics. New Delhi: Government of India; 2019.

- Blendon RJ, Leitman R, Morrison I, Donelan K. Satisfaction with health systems in ten nations. Health Aff. 1990;9(2):185–92. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.9.2.185.

- Bleich SN, Özaltin E, Murray CJ. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009 Apr;87(4):271–78.