ABSTRACT

Strategic purchasing is noted in the literature as an approach that can improve the efficiency of health spending, increase equity in access to health care services, improve the quality of health care delivery, and advance progress toward universal health coverage. However, the evidence on how strategic purchasing can achieve these improvements is sparse. This narrative review sought to address this evidence gap and provide decision makers with lessons and policy recommendations. The authors conducted a systematic review based on two research questions: 1) What is the evidence on how purchasing functions affect purchasers’ leverage to improve: resource allocation, incentives, and accountability; intermediate results (allocative and technical efficiency); and health system outcomes (improvements in equity, access, quality, and financial protection)? and 2) What conditions are needed for a country to make progress on strategic purchasing and achieve health system outcomes? We used database searches to identify published literature relevant to these research questions, and we coded the themes that emerged, in line with the purchasing functions—benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring—and the outcomes of interest. The extent to which strategic purchasing affects the outcomes of interest in different settings is partly influenced by how the purchasing functions are designed and implemented, the enabling environment (both economic and political), and the level of development of the country’s health system and infrastructure. For strategic purchasing to provide more value, sufficient public funding and pooling to reduce fragmentation of schemes is important.

Introduction

Strategic health purchasing is noted in the literature as an approach that can improve the efficiency of health spending, increase equity in access to health care, improve the quality of health care delivery, and advance progress toward universal health coverage (UHC).Citation1–6 Strategic purchasing involves a systematic evaluation of health needs, benefit package design, selection of appropriate providers, payment incentives to providers, and provider monitoring to encourage good performance, using available pooled funds.Citation7

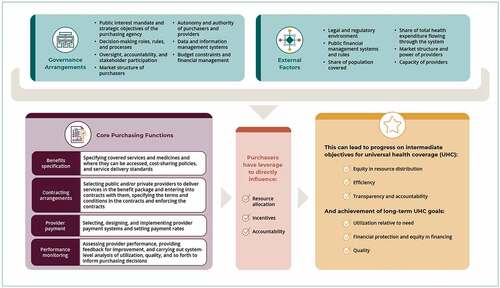

The Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework developed by the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC) and its technical partners describes the purchasing functions, capacities, and enabling environment required for strategic purchasing to improve health outcomes ().Citation8 The premise underlying the framework is that effective strategic purchasing involves a set of core functions (benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring) that are supported by clear institutional arrangements that allocate responsibility for carrying out those functions, governance structures that provide oversight and accountability, and mechanisms to ensure effective stakeholder participation. The core functions are also influenced by external factors that can enhance or limit purchasing power, including the legal and regulatory environment governing other aspects of the health system, the share of the population covered by the purchaser and the share of total health spending it manages, public financial management (PFM) rules, and the market structure of purchasers and providers. Purchasing capacities further affect how well each function is carried out and thus how much they can influence purchasers’ leverage to improve resource allocation, incentives, and accountability; and achieve the desired intermediate results and health system outcomes.

Application of the framework in nine sub-Saharan African countries revealed that progress in strategic purchasing has been limited to certain core functions in some schemes, and that progress at the scheme level has not resulted in large-scale health system change.Citation9 One reason is fragmentation of health financing arrangements, which results in purchasers having little leverage to improve resource allocation and provide incentives to health providers to improve their performance and provide good-quality care. Despite a growing body of evidence on strategic purchasing, no systematic study has been conducted to learn how strategic purchasing reforms have worked in low- and middle-income countries, including key factors that have enabled success, how those factors have affected purchasing functions, and how those functions have led to results. This paper seeks to address that evidence gap.

In this paper, we examine the evidence on country experience in strengthening the four core purchasing functions identified in the framework—benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring—and whether and how improving these core functions has led to direct effects on resource allocation, incentives, accountability, and ultimately intermediate results and health system outcomes. We also examine the preconditions that have led to or contributed to the observed effects and key lessons learned.

Methods

We conducted a literature review between May and August 2020 based on two research questions:

What is the evidence on how the core purchasing functions (benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring) affect purchasers’ leverage to improve: resource allocation, incentives, and accountability); intermediate results (allocative and technical efficiency); and health system outcomes (improvements in equity, access, quality, and financial protection)?Citation8,Citation10,Citation11

What conditions are needed for a country to make progress on strategic purchasing and achieve the desired intermediate results and health system outcomes?

We conducted database searches to identify published literature relevant to these research questions. (See .) We exported the outputs from the searches to a citation manager (Zotero) and uploaded them to EPPI-Reviewer Web (version 4.11.4.0). After screening for duplicates, one reviewer completed an independent review of the title and abstracts. The exclusion criteria were: articles published before 2000; articles not written in English; articles that did not influence at least one purchasing function and describe effects on purchasers leverage to improve resource allocation, incentives, and accountability, intermediate results, or health system outcomes; articles that solely presented theoretical arguments on the topics of interest (e.g., articles on the economic basis of purchasing). The final list for review included 42 articles from Africa, Asia, and Latin America that covered at least one of the four purchasing functions. (See Appendix A for the full list.) depicts the study selection process.

Table 1. Terms and boolean operators used in the literature search.

The articles selected for review used different frameworks to describe the purchasing functions. However, the core purchasing functions as defined in the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework are based on the key purchasing decisions—what to buy (benefits specification), from whom to buy (contracting arrangements), and how to buy (provider payment), and using information to improve these decisions (performance monitoring). The authors used these key principles to match the description in the papers to the core purchasing functions— benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring. While all 42 papers described at least one of the purchasing functions, 29 of the 42 papers described two or more of these functions (Appendix A). Of the 42 papers, only 5 had descriptions of all the core purchasing functions. The authors supplemented the 42 papers with additional country reports from the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, World Bank and World Health Organization.

Common themes were extracted by authors based on the purchasing function and associated results were summarized for each paper according to the purchasing function and outcome of interest (Appendix B). The results of interest were effects of purchasing functions on purchasers’ leverage to improve: resource allocation, incentives, and accountability; intermediate results (allocative and technical efficiency referred to broadly as efficiency); and health system outcomes ().

Results

The authors mapped the findings to the four purchasing functions and summarized how improving these functions affected purchasers’ leverage and intermediate results, as well as health system outcomes. (See Appendix B.)

This section summarizes the underlying conditions and enabling factors that contribute to the observed results and outcomes.

Question 1. What is the evidence on how the core purchasing functions affect purchasers’ leverage, intermediate results, and health system outcomes?

Core Function #1: Benefits Specification

Benefits specification includes determining the services and interventions in the benefit package, the service delivery standards, where and how the services will be accessed (including gatekeeping policies), how much of the cost of services will be covered by the purchaser (and accompanying cost-sharing policies), and which medicines will be covered.Citation8 Specifying the covered services and medicines and how beneficiaries can access them is the first opportunity for purchasers to improve resource allocation, incentives, and accountability, by directing resources to the highest-priority services and populations.

Benefits specification can lead to improvements in equity and access to services when the benefit package is informed by evidence, is needs based, and takes into account the preferences and values of the covered population. The benefit packages in Thailand and Mexico were informed by an evidence-based health technology assessment,Citation12–15 but processes in the Philippines and Vietnam have been less transparent and more subjective.Citation14,Citation16 These differences in benefit package design partly explain the variation in effects on health care access and other health system outcomes in those countries.

Comprehensive benefit packages such as those in the national health insurance systems of Ghana, Mexico, and Thailand—which include necessary inpatient, outpatient, health promotion, and disease prevention services for the enrolled population—have been instrumental in achieving health system outcomes in those countries, including increasing equitable access to and utilization of services and improving financial protection.Citation4,Citation8,Citation17,Citation18 Clearly defined and comprehensive benefit packages have enabled effective resource allocation and accountability for the schemes in meeting commitments to the population.Citation19 Benefit packages can exacerbate inequity, however, when they vary significantly across enrolled population groups, as has been the case in Kenya and the Philippines.Citation16,Citation20

Benefit packages should be adequately communicated to the population so people are aware of their entitlements and obligations and purchasers and providers can be held accountable for providing those entitlements.Citation7 Effective communication empowers beneficiaries—particularly marginalized groups—to claim their benefits while increasing care utilization overall and reducing possible variations in access to care.Citation20 This is particularly true with respect to cost-sharing obligations on the part of beneficiaries. In the Kyrgyz Republic, for example, the introduction of a clearly defined and communicated State Guaranteed Benefit Package in 2001 included formal copayments for nonexempt population groups. Although this was the first time that formal cost-sharing was included in the government health system, this approach has led to documented improvements in financial protection, access, and efficiency and a reduction in informal payments.Citation21

Finally, the benefit package should align with the capacity of the service delivery system to meet commitments to the population. A mismatch between the benefit package and provider capacity to deliver the services hampers access to services and can erode trust in the government’s commitment to ensure access to services with financial protection.Citation8,Citation21

Core Function #2: Contracting Arrangements

Contracting arrangements include systems and policies for selecting public and/or private providers to deliver services in the benefit package, contracts that specify terms and conditions (e.g., at which level specific services can be delivered and data reporting requirements), and enforcement of the contracts.Citation8 Contracting can directly contribute to improved resource allocation, incentives, and accountability by specifying which services can be delivered by which providers, the payment terms, and how providers will be held accountable for complying with the agreed-upon terms. Contracts are an important tool for communicating expectations and introducing a credible threat of being excluded from financing if a provider does not meet minimum quality and performance standards.Citation22

Contracting is most effective when clear criteria are specified for engaging providers and a clear process is in place for identifying providers and establishing and managing agreements with them.Citation23 When population needs are considered in designing the terms of contracts with providers, contracting can enable improvements in health system outcomes. In Thailand’s Universal Coverage (UC) Scheme and China’s social health insurance system, providers are contracted to provide a specific range of services to a specified population.Citation4,Citation12 A “close-to-the-client” provider is contracted to provide outpatient services to the catchment population, to reduce travel costs for patients and increase utilization.

Contracting with private providers is a strategy used by many government purchasing agencies to increase access to services and ensure quality of care.Citation17 In Tanzania, for example, access to publicly funded services in remote areas has improved through contracting with faith-based providers, and financial protection has improved by reducing out-of-pocket payments to these providers.Citation17

Core Function #3: Provider Payment

Provider payment includes the systems and policies for selecting, designing, and implementing provider payment systems and setting payment rates.Citation8 Provider payment is the main tool that purchasers have to improve incentives for providers, but payment systems can also influence resource allocation, either directly or indirectly through incentives, and accountability by linking payment to service delivery.

The evidence shows that provider payment remains an underused strategic purchasing tool, with many countries continuing to rely on input-based budgets or open-ended fee-for-service payment, neither of which has been found to lead directly to improved health system outcomes. Input-based budget payment typically lacks flexibility for providers to allocate spending between line items, with savings made in one line not easily moved to cover deficits in others.Citation24 On the other hand, open-ended fee-for-service payment can lead to cost escalation and a shift to more expensive services.Citation12–15

Provider payment can facilitate improved outcomes when payment is linked to services in the package (“output-based payment”) and specific service delivery objectives. This creates incentives for efficient and high-quality service delivery, promotes effective allocation of resources across levels of care, and enables management of the purchaser’s budget—that is, payments are not open ended but are capped at some level of the system.Citation12,Citation25

Some countries are moving toward output-based payment methods, such as capitation and case-based payment using diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), with some evidence of positive results.Citation12,Citation26 In 2009, China changed the way six public hospitals were paid, moving from fee-for-service to blended methods that included case-based payment with DRGs. DRG payment led to reductions of 6.2% in government health expenditure and 10.5% in out-of-pocket payments by patients per hospital admission. No evidence was found of increased hospital readmission rates or cost shifting from cases eligible for DRG payment to ineligible cases.Citation27

Although stand-alone performance-based financing schemes show mixed results,Citation28 blending performance-based incentives with appropriately selected and designed output-based payment systems have brought service delivery improvements in Estonia.Citation29

Further, it is important to align the payment incentives from multiple funding flows and maintain trust between purchasers and providers—for example, through timely payment and routinely revised payment rates.Citation30–32 A review of provider payment for primary care physicians in China showed that a mixed system of input-based and output-based payment to health facilities was more effective under a long-term contract with the government.Citation30 Regardless of the payment system, when providers are not paid at predefined times, they lose motivation and have an incentive to stop providing services or to charge informal fees.Citation31

Core Function #4: Performance Monitoring

Performance monitoring includes systems and processes for assessing provider performance, providing feedback for improvement, and carrying out system-level analysis of utilization and quality, to inform purchasing decisions.Citation8 Strong performance monitoring systems have been shown to improve health provider accountability, leading to significant gains in efficiency, better adherence to treatment guidelines, expanded access to health care, and improved quality of care.Citation8,Citation12,Citation33 Appropriately monitoring contract performance is important for service quality.Citation17 Defining and tracking metrics for improvement can result in improvements in quality and performance.Citation33

Using performance monitoring to enable improvements in health system results requires strong data systems and effective processes to provide feedback to providers.Citation7 For example, reporting requirements and data quality should be made explicit in contracts with providers.Citation34 Monitoring information should be shared with providers, along with supportive feedback, to enable dialog between purchasers and providers and support performance improvement.Citation35 Further, the intensity of monitoring and verification should be balanced with what these measures can help accomplish in terms of improved accountability and provider performance.Citation36 Monitoring and verification data should be used for further system-level analysis to monitor trends, whether objectives are being met, and whether purchasing policies are leading to any unintended consequences.

Community engagement in the design of performance monitoring systems improves provider accountability and adherence to contracting terms, and it ultimately increases access, equity, and patient satisfaction.Citation33 On the other hand, weak financial and human capacity can limit the effectiveness of performance monitoring.Citation11,Citation17,Citation37

Question 2. What conditions are needed for a country to make progress on strategic purchasing and achieve the desired intermediate results and health system outcomes?

A number of factors external to purchasing arrangements can affect the ability of strategic purchasing to facilitate improvements in intermediate results and health system outcomes. These factors include PFM systems and their rules for planning and budgeting, budget execution, and accounting for public funds.Citation8 In many settings, PFM rules limit the use of output-based payment, such as restrictions on accounting for inputs rather than outputs and prepayment for goods and services. In Kenya and Argentina, facility improvements (including upgrades to infrastructure and equipment) and overall strengthening of service delivery and quality of care were seen when PHC providers received flexible funds.Citation12,Citation26 However, these gains were reversed in Kenya when facility autonomy was reversed and budget execution decisions were recentralized to the county level.Citation27

Evidence from Uganda and Tanzania shows that a good budget structure with PFM rules that allow provider autonomy and flexibility can facilitate strategic purchasing and create a system of accountability for achieving health system goals. The bottom-up budgeting and planning process in Tanzania, which starts at the facility level, and program-based budgeting in Uganda help allocate funds based on priorities and population needs.Citation38 A good government budgeting process with PFM rules that allow for use of output-based payment can improve provider autonomy to use funds flexibly, while ensuring high levels of accountability, as well as improve allocation of resources for health to achieve improved efficiency and the health system goals of improved access and equity.

Purchasing functions, in concert with an enabling environment, can improve purchasers’ leverage, intermediate results, and health system results, as seen in Argentina and Thailand.Citation26 In Argentina, only 0.5% of provincial expenditure for performance contracting by provinces led to reductions in newborn and child mortality. Providing incentives to the provincial health level and providers, empowering providers to control the use of new funds, and creating a culture of accountability fostered the program’s success.

Comprehensive Strategic Purchasing: The Case of Argentina’s Programa Sumar

Argentina’s Plan Nacer, now Programa Sumar, is one example in which rigorous evidence demonstrates the effects of strategic purchasing implemented over time. The combination of changes to the four core purchasing functions has improved purchasers leverage, intermediate results and health system outcomes.

Benefits Specification

Programa Sumar provides a comprehensive benefit package, which has expanded incrementally over time and now covers neonatal care, immunizations, treatment of childhood conditions, reproductive care, and other essential services over the life cycle, from childhood through adolescence, reproductive age, adulthood, and old age.Citation39,Citation40

Contracting Arrangements

Provider contracts define the services, payment arrangements, and performance metrics to be monitored. Providers are granted autonomy in financial decision making, giving them the flexibility to respond to incentives.

Provider Payment

Resource allocation to the provinces is based on health indicators and provincial performance, while payment to facilities is made through fee-for-service payments based on achievement of predefined health indicators and targets.

Performance Monitoring

An impact evaluation of Plan Nacer showed that in participating facilities between 2005 and 2008, the risk of neonatal death among covered babies declined by 74%.Citation39,Citation41 The risk of low birth weight in participating facilities declined by 9% among non-beneficiaries and 19% among beneficiaries. Women enrolled in the plan were 20% less likely to need a cesarean section, and Plan Nacer averted an estimated 773 neonatal deaths and 1,071 cases of low-birth-weight babies and saved 25,401 total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), with an estimated cost per lost DALY averted of USD $814, well under Argentina’s gross domestic product per capita of USD $6,075.

Discussion

This review found cases of improvements in access to services, quality of care, and equity following implementation of one or a combination of the core purchasing functions. However, a key limitation is that the studies did not follow a randomized controlled trial (RCT) methodology that would be able to attribute specific improvements to strategic purchasing or attribute specific improvements to purchasing functions. This review was also limited because the authors only included papers written in English. Majority of the papers reviewed were based on health insurance schemes and a limited number of studies assessed purchasing through government-budgets. The findings are based largely on anecdotal evidence as synthesized from the studies, and the conclusions drawn in this review should be understood from that perspective. Further, the reviewed studies did not use similar frameworks to define the purchasing functions, such as the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework. Many of the studies were descriptive in nature, describing one or more functions but not exactly in the same way as in the Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework. It is impossible to precisely attribute health system effects to strategic purchasing, and many of the examples in the literature are anecdotal or inferred based on expected pathways for strategic purchasing to achieve the health system results of equitable access to good-quality services without financial hardship.

This review found few exemplars of well-functioning strategic purchasing systems among low- and middle-income countries. Differences in institutional capacities and health system infrastructure are among the key contextual factors that explain the varying levels of success with different interventions.

Nonetheless, there is evidence that even incremental progress can lead to improved health system outcomes and that, conversely, weak purchasing arrangements can work against UHC objectives even as coverage expands and health expenditure increases.Citation8 An enabling environment is critical to achieving the benefits of strategic purchasing, particularly a strong PFM and budgeting system and autonomy of health providers to respond to purchasing incentives.

Furthermore, for strategic purchasing to work well, other health financing functions, including revenue collection and pooling, must be structured in a way that maximizes the benefits.Citation10,Citation11,Citation42 Low public financing remains the main barrier to achieving UHC goals.Citation43 The health system must also have sufficient health workers, commodities, and medical supplies as well as strong leadership that makes evidence-based decisions. Fragmentation, which is sometimes created by donor-driven agendas, is a critical roadblock to sustainable systemwide strategic purchasing reforms.Citation9 Even when progress is made in strategic purchasing within a scheme, only a small portion of the funds are channeled through the scheme, which limits the use of purchasing power to exert influence on the system.

This review has exposed key gaps in the evidence on the role of strategic purchasing in advancing progress toward better health system outcomes. More evidence is needed on how a combination of reforms to the purchasing functions can affect health system performance and, in particular, how the purchasing functions reinforce one another. Another area that needs more understanding is how to achieve the right power balance between purchasers and providers so they can engage effectively in purchasing functions and respond to incentives. There is also limited evidence on effective frameworks for engaging the private sector and improving contracting with private providers, especially in countries that largely finance health services through public resources.

Conclusion

Strategic purchasing has been identified as a key approach for achieving the UHC goals of improved and equitable access and financial risk protection. However, improvements in purchasing depend on a range of factors, including strengths and shortcomings in human resources, information technology, governance, supply chains, and the regulatory environment. They also depend on external factors such as monitoring and accountability frameworks and the managerial autonomy of providers and purchasers. Although the evidence base is not broad, a number of lessons have emerged to guide countries that are looking to design or modify purchasing functions in a manner that can promote their health system goals.

Clear health system objectives and a strategy that clarifies the role of purchasers and the intended results are critical. Consensus among stakeholders on these objectives, including tradeoffs in benefits specification, contracting arrangements, and provider payment, is a prerequisite to aligning stakeholders around health system objectives. Social accountability and social justice mechanisms that promote transparency and citizen engagement are needed to improve the accountability of purchasers to beneficiaries. Effective communication is vital to inform the population of their entitlements and obligations; empower beneficiaries, particularly marginalized groups, to claim their benefits; improve utilization among marginalized groups; and reduce variations in access to care. Purchasers also need the capacity to carry out strategic planning and policy development, generate information on health needs and system capacity, make purchasing decisions within the constraints of the current system, and communicate strategically with both providers and the covered population. The involvement of high-level public health officials in designing strategic purchasing interventions, as well as a strong political and technical teams, can increase the chances of success of improving purchasing functions.

Although the evidence base remains incomplete, strategic purchasing is a necessary policy direction for countries at all income levels to channel limited health funds most effectively toward improved health system outcomes. Stronger evidence is needed on what makes strategic purchasing effective in different contexts to continue making the case for strategic purchasing and to better understand how improvements in purchasing can result in better health system outcomes.

Author Contributions

FM and RS carried out the data extraction and synthesis. FM and A G-M wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Benjamin Picillo, who conducted the literature search and selection, and all the individuals who provided insights, comments, and reviews that improved the quality of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cashin C, Nakhimovsky S, Laird K, Strizrep T, Cico A, Radakrishnan S, Lauer A, Connor C, O’Dougherty S, White J, et al. Strategic health purchasing progress: a framework for policymakers and practitioners. Bethesda (MD): Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates; 2018 [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TBMG.pdf.

- Bastani P, Samadbeik M, Kazemifard Y. Components that affect the implementation of health services’ strategic purchasing: a comprehensive review of the literature. Electron Physician. 2016;8(5):4–28. doi:10.19082/2333.

- Habicht T, Habicht J, van Ginneken E. Strategic purchasing reform in Estonia: reducing inequalities in access while improving care concentration and quality. Health Policy (New York). 2015;119(8):1011–16. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.06.002.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Thammatacharee J, Jongudomsuk P, Sirilak S. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1152–61. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu120.

- Reinhardt U, Cheng T. The world health report 2000—Health systems: improving performance. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1064.

- Sanderson J, Lonsdale C, Mannion R. What’s needed to develop strategic purchasing in healthcare? Policy lessons from a realist review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(1):4–17. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2018.93.

- Mathauer I, Dale E, Jowett M, Kutzin J. Purchasing of health services for universal health coverage: how to make it more strategic? Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019 ( Health financing policy brief; no. 6). [accessed 2022 February 1]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311387.

- Cashin C, Gatome-Munyua A. The strategic health purchasing progress tracking framework: a practical approach to describing, assessing, and improving strategic purchasing for universal health coverage. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(2):e2051794. doi:10.1080/23288604.2022.2051794.

- Gatome-Munyua A, Sieleunou I, Barasa E, Ssengooba F, Issa K, Musange S, Osoro O, Makawia S, Boyi-Hounsou C, Amporfu E, et al. Applying the strategic health purchasing progress tracking framework: lessons from nine African countries. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(2):e2051796. doi:10.1080/23288604.2022.2051796.

- Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangement. Health Policy (New York). 2001;56(3):171–204. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00149-4.

- Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(8):602–11. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.113985.

- Langenbrunner JC, Cashin C, O’Dougherty S, editors. Designing and implementing health care provider payment systems: how-to manuals. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2009 [accessed 2022 Feb 1]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275637955_Designing_and_Implementing_Health_Care_Provider_Payment_Systems_How-to_Manual.

- Cashin C, Ankhbayar B, Phuong HT, Jamsran G, Nanzad O, Phuong NK, Oanh TT, Tien TV, Tsilaajav T. Assessing health provider payment systems: a practical guide for countries working toward universal health coverage. Arlington (VA): Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage / Results for Development Institute; 2015 [accessed 2021 Sep 29]. https://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/resources/assessing-health-provider-payment-systems-a-pr.

- Wang H, Otoo N, Dsane-Selby L. Ghana national health insurance scheme: improving financial sustainability based on expenditure review. World bank studies. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2017 (A World Bank study). [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/493641501663722238/pdf/117828-PUB-PUBLIC-pubdate-7-31-17.pdf.

- Phuong NK, Oanh TT, Phuong HT, Tien TV, Cashin C. Assessment of systems for paying health care providers in Vietnam: implications for equity, efficiency and expanding effective health coverage. Glob Public Health. 2015;10(Suppl 1):S80–94. doi:10.1080/17441692.2014.986154.

- Obermann K, Jowett M, Kwon S. The role of national health insurance for achieving UHC in the Philippines: a mixed methods analysis. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1483638. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1483638.

- Rao KD, Paina L, Ingabire MG, Shroff ZC. Contracting non-state providers for universal health coverage: learnings from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):127. doi:10.1186/s12939-018-0846-5.

- Chemor Ruiz A, Ratsch AEO, Alamilla Martínez GA. Mexico’s Seguro popular: achievements and challenges. Health Syst Reform. 2018;4(3):194–202. doi:10.1080/23288604.2018.1488505.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Sakuma Y, Smith PC. Defining a health benefits package: what are the necessary processes? Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):39–50. doi:10.1080/23288604.2016.1124171.

- Mbau R, Kabia E, Honda A, Hanson K, Barasa E. Examining purchasing reforms towards universal health coverage by the National Hospital Insurance Fund in Kenya. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1116-x.

- Giuffrida A, Jakab M, Dale EM. Toward universal coverage in health: the case of the State Guaranteed Benefit Package of the Kyrgyz Republic. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 2013 ( Universal health coverage studies series [UNICO]. no. 17). [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/685631468278090377/pdf/750060NWP0Box30l0Coverage0in0Health.pdf.

- Figueras J, Robinson R, Jakubowsky E. Purchasing to improve health systems performance: drawing the lessons. In: Figueras J, Robinson R, editors. Jakubowsky, purchasing to improve health systems performance. Maidenhead (UK): Open University Press; 2005. p. 44–80. [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.academia.edu/13682135/Purchasing_to_Improve_Health_Systems_Performance_Drawing_the_Lessons.

- Howden-Chapman P, Ashton T. Shopping for health: purchasing health services through contracts. Health Policy (New York). 1994;29(1–2):61–83. doi:10.1016/0168-8510(94)90007-8.

- Cashin C, Batbayar A, Tsilaajav T, Nanzad O, Jamsran G, Somanathan A. Assessment of systems for paying health care providers in Mongolia: implications for equity, efficiency and universal health coverage. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2015. Report no. 98790-MN. [accessed 2022 November 7]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/711891467991004186/Assessment-of-systems-for-paying-health-care-providers-in-Mongolia-implications-for-equity-efficiency-and-universal-health-coverage.

- Jowett M, Kutzin J, Kwon S, Hsu J, Sallaku J, Solano JG, Hsu J, Sallaku J, Solano JG, Sallaku J, et al. Assessing country health financing systems: the health financing progress matrix. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2020 (Health financing guidance; no. 8). [accessed 2020 Sep 29]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017405.

- Mathauer I, Wittenbecher F. Hospital payment systems based on diagnosis-related groups: experiences in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(10):746–756A. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.115931.

- Jian W, Lu M, Chan KY, Poon AN, Han W, Hu M, Yip W. Payment reform pilot in Beijing hospitals reduced expenditures and out-of-pocket payments per admission. Health Aff. 2015;34(10):1745–52. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0074.

- de Walque D, Kandpal E, Wagstaff A, Friedman F, Neelsen S, Piatti-Fünfkirchen M, Sautmann A, Shapira G, Van de Poel E. Improving effective coverage in health: do financial incentives work? Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2022. Policy research report. [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/improving-effective-coverage-in-health.

- Habicht T, Reinap M, Kasekamp K, Sikkut R, Aaben L, van Ginneken E. Estonia: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2018;20(1). Copenhagen (Denmark) World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe van Ginneken E, editor. (Busse R, Figueros J, McKee M, Mossialos E, Nolte E, van Ginneken E, editors. [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/estonia-health-system-review-2018.

- Barasa E, Mathauer I, Kabia E, Ezumah N, Mbau R, Honda A, Dkhimi F, Onwujekwe O, Phuong HT, Hanson K. How do healthcare providers respond to multiple funding flows? A conceptual framework and options to align them. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(6):861–68. doi:10.1093/heapol/czab003.

- Akweongo P, Chatio ST, Owusu R, Salari P, Tedisio F, Aikins M. How does it affect service delivery under the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana? Health providers and insurance managers perspective on submission and reimbursement of claims. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247397. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247397.

- Kazungu JS, Barasa EW, Obadha M, Chuma J. What characteristics of provider payment mechanisms influence health care providers’ behaviour? A literature review. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2018;33(4):e892–e905. doi:10.1002/hpm.2565.

- Dzakula A, Sagan A, Pavíc N, Lonćčarek K, Sekelj-Kauzlarić K. Croatia: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2014;16:1–162.

- Perrot J, de Roodenbeke E, editors. Strategic contracting for health systems and services. New York (NY): Routledge; 2012 [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315130309/strategic-contracting-health-systems-services-eric-de-roodenbeke-jean-perrot.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Using data analytics to monitor health provider payment systems: a toolkit for countries working toward universal health coverage. Arlington (VA): Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage / Results for Development Institute; 2017. Seattle (WA): PATH; Amsterdam (Netherlands): PharmAccess Foundation. [accessed 2021 Sep 29]. https://media.path.org/documents/DHS_jln_full_toolkit.pdf.

- Waithaka D, Cashin C, Barasa E. Is performance-based financing a pathway to strategic purchasing in sub-Saharan Africa? A synthesis of the evidence. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(2):e2068231. doi:10.1080/23288604.2022.2068231.

- Hanson K, Barasa E, Honda A, Panichkriangkrai W, Patcharanarumol W. Strategic purchasing: the neglected health financing function for pursuing universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries. Comment on “What’s needed to develop strategic purchasing in healthcare? Policy lessons from a realist review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(8):501–04. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2019.34.

- Ssennyonjo A, Osoro O, Ssengooba F, Ekirapa E, Mayora C, Ssempala R, Bloom D. The government budget: an overlooked vehicle for advancing strategic health purchasing. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(2):2082020. doi:10.1080/23288604.2022.2082020.

- Sabignoso M, Zanazzi L, Sparkes S, Mathauer I. Strengthening the purchasing function through results-based financing in a federal setting: lessons from Argentina’s Programa Sumar. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2020. Health financing working paper; no. 15. [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003651.

- Joint Learning Network (JLN). Financing and payment models for primary health care: six lessons from JLN country implementation experience. Arlington (VA): Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage / Results for Development Institute; 2017 [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/phc-financing-payment-models-six-lessons.pdf.

- Nuñez PA, Fernández-Slezak D, Farall A, Szretter ME, Salomón OD, Valeggia CR. Impact of universal health coverage in child growth and nutrition in Argentina. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):720–26. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303056.

- Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):867–68. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.113654.

- Barroy H, Musango L, Hsu J, Van de Maele N. Public financing for health in Africa: from Abuja to the SDGs. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2016 [accessed 2022 November 7]. https://www.afro.who.int/publications/public-financing-health-africa-abuja-sdgs.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage (JLN). JLN/GIZ case studies on payment innovation in primary health care: series summary. Arlington (VA): JLN; 2017 [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://improvingphc.org/sites/default/files/JLN-GIZ_Case_Studies_on_Payment_Innovation_for_Primary_Health_Care__0.pdf.

- Van de Poel E, Flores G, Ir P, O’Donnell O. Impact of performance‐based financing in a low‐resource setting: a decade of experience in Cambodia. Health Econ. 2016;25(6):688–705. doi:10.1002/hec.3219.

- Bigdeli M, Annear PL. Barriers to access and the purchasing function of health equity funds: lessons from Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(7):560–64. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.053058.

- Yip W, Fu H, Chen TA, Zhai T, Jian W, Xu R, Pan J, Hu M, Zhou Z, Chen Q, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1192–204. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1.

- Pu X, Gu Y, Wang X. Provider payment to primary care physicians in China: background, challenges, and a reform framework. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;20:e34. doi:10.1017/S146342361800021X.

- Gajate-Garrido G, Ahiadeke C. The effect of insurance enrollment on maternal and child health care utilization: the case of Ghana. Washington (DC): International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2015. IFPRI discussion paper; no. 01495. [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/effect-insurance-enrollment-maternal-and-child-health-care-utilization.

- Fenny AP, Asante FA, Enemark U, Hansen KS. Malaria care seeking behavior of individuals in Ghana under the NHIS: are we back to the use of informal care? BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):370. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1696-3.

- Witter S, Garshong B. Something old or something new? Social health insurance in Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(1):20. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-9-20.

- Nguyen HT, Rajkotia Y, Wang H. The financial protection effect of Ghana national health insurance scheme: evidence from a study in two rural districts. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):4. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-10-4.

- Cashin C. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: ensuring access to essential malaria services with financial protection. Bethesda (MD): Abt Associates; 2016 [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00M66H.pdf.

- Wang W, Temsah G, Mallick L. The impact of health insurance on maternal health care utilization: evidence from Ghana, Indonesia and Rwanda. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(3):366–75. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw135.

- Cashin C, Hendrartini Y, Trisnantoro L, Pervin A, Taylor C, Hatt L. HFG Indonesia strategic health purchasing (November 2016-August 2017): final report. Bethesda (MD): Abt Associates. 2017. [accessed 2022 November 15] https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00T3GH.pdf.

- Munge K, Mulupi S, Barasa E, Chuma J. A critical analysis of purchasing arrangements in Kenya: the case of micro health insurance. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):45. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3863-6.

- Feldhaus I, Mathauer I. Effects of mixed provider payment systems and aligned cost sharing practices on expenditure growth management, efficiency, and equity: a structured review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):996. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3779-1.

- Waweru E, Nyikuri M, Tsofa B, Kedenge S, Goodman C, Molyneux S. Review of Health Sector Services Fund implementation and experience. London (UK): RESYST; 2013 [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://resyst.lshtm.ac.uk/resources/review-of-health-sector-services-fund-implementation-and-experience.

- Barasa EW, Manyara AM, Molyneux S, Tsofa B. Recentralization within decentralization: county hospital autonomy under devolution in Kenya. PloS One. 2017;12(8):e0182440. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182440.

- Habicht J, Hawkins L, Jakab M, Rannamäe A, Sydakova A. Governance for strategic purchasing in Kyrgyzstan’s health financing system. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2020 (Health financing case study; no. 16). [accessed 2022 November 9]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000345-3.

- Beith A, Wright J, Ergo A. The link between provider payment and quality of maternal health services: case studies on provider payment mechanisms in Kyrgyz Republic, Nigeria, and Zambia. Bethesda (MD): Health Finance and Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2017 [accessed 2022 November 9]. https://www.hfgproject.org/link-provider-payment-quality-maternal-health-services-case-studies-provider-payment-mechanisms-kyrgyz-republic-nigeria-zambia/.

- Kutzin J. Health expenditures, reforms and policy priorities for the Kyrgyz Republic. Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan): Manas Health Policy Analysis Project; 2003. Policy research paper; no. 24. [accessed 2022 November 9]. http://hpac.kg/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/PERJKforPRP24.pdf.

- Jakab M, Kutzin J. Improving financial protection in Kyrgyzstan through reducing informal payments: evidence from 2001–06. Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan): Manas Health Policy Analysis Project; 2009. Policy research paper; no. 57.

- Jakab M, Akkazieva B, Kutzin J. Can reductions in informal payments be sustained? Evidence from Kyrgyzstan, 2001–2013. Copenhagen (Denmark): World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2016. Health financing policy papers. [accessed 2022 November 9]. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/329223/Informal-payments-KGZ.pdf.

- González Block MA, Reyes Morales H, Cahuana Hurtado L, Balandrán A, Méndez E. Mexico: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2020;22(2). Copenhagen (Denmark); World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; Allin S, Marchilden G, editors. (Busse R, Figueros J, McKee M, Mossialos E, van Ginneken E, editors.[accessed 2022 November 8]. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/mexico-health-system-review-2020.

- Nigenda G, Wirtz VJ, González-Robledo LM, Reich MR. Evaluating the implementation of Mexico’s health reform: the case of Seguro Popular. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1(3):217–28. doi:10.1080/23288604.2015.1031336.

- Tien TV, Phuong HT, Mathauer I, Phuong NTK. A health financing review of Viet Nam with a focus on social health insurance: bottlenecks in institutional design and organizational practice of health financing and options to accelerate progress towards universal coverage. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2011 [accessed 2022 November 9]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341160.

- Patcharanarumol W, Panichkriangkrai W, Sommanuttaweechai A, Hanson K, Wanwong Y, Tangcharoensathien V. Strategic purchasing and health system efficiency: a comparison of two financing schemes in Thailand. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195179. [accessed 2022 November 15]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29608610/.

- García-Díaz R, Sosa-Rubí S. Analysis of the distributional impact of out-of-pocket health payments: evidence from a public health insurance program for the poor in Mexico. J Health Econ [Internet]. 2011 July;30(4):707–18. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.04.003.

- Hone T, Habicht J, Domente S, Atun R. Expansion of health insurance in Moldova and associated improvements in access and reductions in direct payments. J Glob Health. 2016;6(2):020702. doi:10.7189/jogh.06.020702.

- Turcanu G, Domente S, Buga M, Richardson E. Republic of Moldova: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;14(7). Copenhagen (Denmark); World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; Richardson E, editor. (Busse R, Figueros J, McKee M, Saltman R, editors. [accessed 2022 November 8]. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/republic-of-moldova-health-system-review-2012.

- Vian T, Feeley FG, Domente S, Negruta A, Matei A, Habicht J. Barriers to universal health coverage in Republic of Moldova: a policy analysis of formal and informal out-of-pocket payments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:319. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0984-z.

- Dugee O, Sugar B, Dorjsuren B, Mahal A. Economic impacts of chronic conditions in a country with high levels of population health coverage: lessons from Mongolia. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24(6):715–26. doi:10.1111/tmi.13231.

- Etiaba E, Onwujekwe O, Honda A, Ibe O, Uzochukwu B, Hanson K. Strategic purchasing for universal health coverage: examining the purchaser–provider relationship within a social health insurance scheme in Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e000917. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000917.

- Reyes KAV, Ho BLC, Nuevo CEL, et al. Policy analysis on criteria and priority setting process for new technologies to be adopted in PhilHealth benefit package development. Manila (Philippines): UNICEF; 2016.

- Limwattananon S, Neelsen S, O’Donnell O, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V, van Doorslaer E. Universal coverage on a budget: impacts on health care utilization and out-of-pocket expenditures in Thailand. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Tinbergen Institute; 2013. Tinbergen Institute discussion paper; no. TI 2013-067/V. [accessed 2022 November 9]. https://papers.tinbergen.nl/13067.pdf.

- Intaranongpai S, Hughes D, Leethongdee S. The provincial health office as performance manager: change in the local healthcare system after Thailand’s universal coverage reforms. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2012;27(4):308–26. doi:10.1002/hpm.2113.

- Le QN, Blizzard L, Si L, Giang LT, Neil AL. The evolution of social health insurance in Vietnam and its role towards achieving universal health coverage. Health Policy OPEN. 2020;1:100011. doi:10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100011.