ABSTRACT

A new law was voted in France in 2016 to increase cooperation between public sector hospitals. Hospitals were encouraged to work under the leadership of local referral centers and to share their support functions (e.g., information systems) with newly created hospital groups, called “Regional Hospital Groups.” The law made it compulsory for each public sector hospital to become affiliated with one of 136 newly created hospital groups. The policy’s aim was to ensure that all patients were sent to the hospital best qualified to treat their unique condition, among the hospitals available at the regional level. Therefore, we aimed to assess whether this regionalization policy was associated with changes in observed patterns of patient mobility between hospitals. This nationwide observational study followed an interrupted time series design. For each stay occurring from 2014 to 2019, we ascertained whether or not the stay was followed by mobility toward another hospital within 90 days, and whether or not the receiving hospital was part of the same Regional Hospital Group as the sender hospital. The proportion of mobility directed toward the same regional hospital group increased from 22.9% in 2014 (95% CI 22.7–23.1) to 24.6% in 2019 (95% CI 24.4–24.8). However, the absence of discontinuity during the policy change year was consistent with the hypothesis of a preexisting trend toward regionalization. Therefore, the policy did not achieve major changes in patterns of mobility between hospitals. Other objectives of the reform, including long-term consequences on the healthcare offer, remain to be assessed.

Introduction

Regionalization is defined as an active process by which patients are matched to appropriate resources.Citation1 A volume-outcomes relationship whereby hospitals treating more patients provide higher quality of care has been observed for a variety of diseases: traumatic injuries,Citation2 stroke,Citation3 acute respiratory distress syndrome,Citation4,Citation5 urgent vascular surgery procedures,Citation6–9 and bariatric surgery.Citation10 Therefore, in order to achieve the best outcomes for their patients, physicians may be tempted to refer them to a nearby high-volume hospital instead of treating them locally. Inter-hospital patient transfers are frequent, with more than 500,000 such transfers each year in France.Citation11 Nonetheless, patient mobility can be perceived as complex, expensive, and presenting a risk of adverse events.Citation12 Moreover, although the expertise of a hospital is a key consideration when considering whether to refer a patient, referrals also depend on organizational and relational factors.Citation13 Planning a patient transfer or referral should be easier if the sending and the receiving hospital are part of the same administrative group.Citation14 In a study conducted in the Massachusetts region, shared affiliation increased the likelihood of transfer by a factor of 5.8.Citation15 Although there are other aspects to collaboration between hospitals, the ability to refer or share patients can be considered as a marker of collaboration or increased ties between hospitals.Citation16

Conveniently, a law for the modernization of healthcare was voted in France in 2016 in order to increase coordination between public sector hospitals. The French health system is based on a universal health insurance for all citizens, with healthcare delivered by public and private operators (of which some do not operate for profit). The system is characterized by high public spending on health, and this budget is primarily financed through working citizens’ compulsory social security contributions and taxes, rather than by direct, out-of-pocket expenditure.Citation17–19 Patients are free to consult or to be hospitalized in any healthcare facility they choose. The 2016–41 law (adopted on January 26, 2016) made it compulsory for French hospitals of the public sector to partake in the creation of new groups of hospitals called Regional Hospital Groups (RHGs). Each of these groups was encouraged to have a unique governing body, to work under the supervision of a leader hospital, and to share support functions (including the hospital informatics system, acquisitions, logistics, continuing medical education, and insurance).

One of the aims of this reform was to allow hospitals to provide the appropriate level of technicity for each patient, so that patients would be treated in the right hospital within the group according to their needs. This aim could be facilitated by a variety of measures, which were part of the policy change. First, functioning in a hospital group under common leadership could attenuate competition between hospitals, and therefore encourage referrals. Second, a shared information system could facilitate patient mobility, defined as successive visits to two different hospitals during a brief period. Third, it was anticipated that the creation of new care services serving the entire RHG for each disease would result in patients being referred to these unique, group-level, specialized facilities. This policy constituted a new tool to regulate healthcare among French regions, and an addition to preexisting toolsCitation20 such as regional stay volume objectives and plans pertaining to interregional cooperation for highly specialized treatments (e.g. neurosurgery).

The policy was a new step toward regionalized care in France, following the 2009 law which had created Regional Health Agencies (Agences Régionales de Santé) seven years earlier. The creation of hospital groups working together as a network of complementary, rather than competing organizations,Citation21 was expected to increase access to efficient and high-quality care, and thereby, to increase health-related equity for all patients. At the time of the policy change, the extent to which the measures implemented by the policy would encourage patient mobility within RHGs could only be inferred based on predictive statistical models. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate whether, based on medico-administrative data, the 2016 French law was really associated with an increase in patient mobility within hospitals belonging to the newly formed Regional Hospital Groups.

Materials and Methods

Population and Design

The study was an observational, retrospective, nationwide study following a risk-adjusted interrupted time series design, with an analysis conducted at the level of individual hospital stays. We studied stays occurring in French public hospitals affiliated with Regional Hospital Groups from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2019. The period before the intervention consisted of the years 2014 and 2015. The year 2016, in which the law took effect, was considered as a transition period. Years 2017 to 2019 followed the reform and constituted the post-intervention period. The unit of analysis was the individual hospital stay. The primary outcome was whether or not a hospital stay was followed by a within-RHG patient mobility. We compared the number of stays followed by a patient mobility within the RGH each year (each of these stays was counted as a positive primary outcome), after the reform (2017 to 2019), and before the reform (years 2014 and 2015). The association between the period and the primary outcome was studied both in unadjusted and risk-adjusted analyses. The effect of the 2016 law would be considered positive if the adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) for mobility toward the same group in the year 2019 was higher than for the reference year 2014. The strength of evidence would be reinforced by the observation of a discontinuity (sudden or rapid change) in patient mobility rates near the policy change year (2016), and by a difference in observed trends between mobility toward the same RHG and mobility toward other hospitals.

Policy Change Companion Program

The regionalization program was accompanied by a nationwide implementation program that included the publication of written RHG guidelines, learning and co-development sessions, and an experience-sharing program with an evaluation of success cases and risks associated with the policy change.Citation22 Each RHG could participate in one or more of the implementation program activities.

Data Sources

Hospitalization Data

We obtained data from the French Medical Information System. The source database, which is used by the national health insurance system to pay hospitals, includes all hospital discharges in the entire territory of France.Citation23 The data included were prospectively collected by the clinicians in charge of their patients, and verified by medical informatics professionals. Inpatient stays were recorded as standard discharge abstracts containing demographic characteristics (age and sex), primary or secondary diagnoses (using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision), as well as detailed procedural codes associated with the care provided. Each stay occurring in French hospitals is part of the database. The chronology of stays was also available in the database, so that it was possible to ascertain whether the patient had previously been hospitalized within the last 30 days, which can be seen as a negative indicator of health.Citation24 Stays for newborns or iterative treatments (e.g., hemodialysis, chemotherapy), short transfers <48 hours, and stays from hospitals with <20 cases of patient mobility toward the RHG were excluded. Stays occurring in overseas territories were also excluded due to their specific situation with regard to patient mobility. The data used for the primary multivariable analysis excluded stays that were not followed by a patient mobility within 90 days. Because stays that were not followed by patient mobility within 90 days were excluded from the model used in the primary analysis, there were only two possible outcomes for each stay in this model: either the next stay of the patient occurred in one of the other hospitals of the RHG (termed “within-RHG mobility”), or it occurred in a hospital outside of the RHG (negative outcome). An increase in mobility within the RHG at the expense of mobility outside of the RHG could be interpreted as meaning that hospitals inside the RHG have implemented new patient-sharing networks or reinforced their existing ties.

Moreover, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that was based on data which also contained stays that were not followed by mobility within 90 days. These stays were included in the data used for the sensitivity analysis and considered as negative outcomes. The aim of the sensitivity analysis was to show an absolute increase in mobility within the RHG. In contrast, the primary analysis aimed to show a relative increase in mobility within the RHG, at the expense of mobility toward other hospitals not included in the RHG.

Primary Outcome

The main outcome was patient mobility inside the RHG. For each stay that occurred in a hospital practicing Medicine, Surgery or Obstetrics (MSO), the main outcome was defined as positive if the stay was followed by a stay in a different hospital of the same RHG within 90 days of discharge. Readmissions to the same hospital were not counted as positive cases of mobility. The 90-day period allowed for the inclusion of cases of mobility that occurred within zero days (direct transfers), while also considering referral hospitalizations planned at a later date. The main outcome was considered negative if the subsequent stay occurred in the same hospital (regarding the multivariable analysis, this case was only possible in the data used for the sensitivity analysis, as stays followed by same-hospital readmissions were excluded from the data used for the primary multivariable analysis). The main outcome of within-RHG mobility was also negative if the mobility was directed toward a hospital situated in another RHG, or if it was directed toward a hospital not affiliated to any RHG (for example, most hospitals situated in the greater Paris region were exempted from joining a RHG, so mobility directed toward these hospitals was always counted as a negative outcome). The main outcome was also negative if the subsequent stay was in a hospital operating in the private sector. If there was no subsequent stay within 90 days, the main outcome was also negative (regarding the multivariable analyses, this case could only occur in the data used for the sensitivity analysis, as there were no stays that were not followed by mobility in the data used for the primary multivariable analysis).

Abstracting of Clinical Data

All stays in the French Medical Information System are routinely assigned to a Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG), which summarizes clinical data derived from patient and stay characteristics. For a higher-level analysis, the DRGs can be assigned to one of 27 broad domains (e.g. digestive system, pulmonology) described in the Activity Domain (AD) classification.Citation25 The Elixhauser comorbidity index with 31 categories was used to assess patient severity.Citation26,Citation27

Socioeconomic Data Based on the Place of Residence

The medical informatics database is pseudonymized and does not contain, for example, patient names or precise addresses. However, it contains a code for the place of residence of the patient, with a precision of a few kilometers (equivalent to a zip code). The place of residence can be matched to a geographical indicator of socio-economic status, namely the French Deprivation Index (FDI), which is partly based on the per capita income of the local area.Citation28,Citation29 This continuous variable was centered by subtracting the mean and scaled by dividing it by its standard deviation.

Data Regarding Hospital Characteristics

Three types of hospitals were considered, based on the association between the number of stays per year and observed patient mobility in French hospitals.Citation30 The smallest hospitals, which were expected to have a high rate of patient mobility, were defined as those with <1500 stays per year. Large centers were defined as centers with ≥50,000 stays per year, and the remainder constituted the middle category. Human resources data and the number of beds per hospital were retrieved from official annual hospital statistics published by the French national agency in charge of medical information.Citation31

Regional Hospital Group Characteristics

RHG-level data was retrieved from national financial audit authorities.Citation11 This data included the number of associated centers (hospital-at-home organizations or long-term care facilities) affiliated with the RHG, and the number of partner hospitals (partner hospitals are private sector hospitals that have a cooperation contract with the RHG; the for-profit status of private hospitals prevents them from being full members of a RHG). The average number of managing directors per hospital in the RHG was also calculated and defined as the ratio between the total number of directors and the total number of hospitals. The number of patient pathways (coordinated care between several actors, e.g., geriatrics pathway, palliative care) included in the RHG project was also recorded. We also ascertained whether all hospitals were under common leadership and whether each RHG had a complete territorial analysis in its founding contract. It was also possible to determine whether the percentage of medical teams merged into a RHG-level team was higher than the median of 12.5%.

Ethical and Regulatory Aspects of the Study

The study was declared to the French registry of studies using healthcare data (N° F20210106180024). As the study was retrospective, based on anonymized data and purely observational, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval according to the French Public Health Code (L1121-1, law number 2012–300, March 5, 2012).

Statistical Methods

Descriptive and Unadjusted Analysis

The characteristics of RHGs were described with summary statistics, using frequencies and percentages, the mean and standard deviation, or the median and interquartile range for asymmetric continuous variables. In a first descriptive step, the proportion of stays followed by a within-RHG patient mobility was evaluated before and after the reform (in years 2014 and 2019) using all hospital stays (including those not followed by any type of mobility) as the denominator. The proportion of stays followed by a within-RHG mobility was also evaluated separately for selected activity domains (digestive system, orthopedics and trauma, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory medicine). These activity domains were chosen based on clinical relevance before conducting the subgroup analysis.

Multivariable Analysis

As it was not possible to include all stays in the risk-adjusted analysis (because this would require expensive computing resources) we used a convenience sample of 20% of all stays. The sample used for the primary multivariable analysis was extracted with random (non-stratified) sampling among stays followed by any type of mobility, within or outside of the index stay RHG. To compare the characteristics of stays followed by a within-RHG mobility with the characteristics of stays not followed by a within-RGH mobility, statistical tests were performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.Citation32 The effect size for qualitative and continuous variables was calculated with Cramér’s V or Cohen’s D as appropriate.

The multivariable analysis was conducted using a mixed effects logistic regression model,Citation33 modeling the probability of patient mobility following each stay within the RHG. The independent variable of interest was the year indicator.

Adjustment variables potentially associated with the main outcome were chosen a priori based on expert review. The model was adjusted for fixed effects: age (included as a continuous variable), sex, activity domain grouping,Citation25 the type of stay (surgical or medical), comorbidity measured by the Elixhauser score,Citation26,Citation27 and the FDI socioeconomic indicator.Citation28 An interaction between the type of stay (surgical or medical) and the Activity Domain classification was included in the model to allow for variable effects according to the type of surgery. An indicator mentioning whether the patient had already been hospitalized within the previous 30 days was included as an additional proxy of severity.Citation24 The analysis was adjusted for hospital volume, defined as the number of stays per year. RHG-level adjustment variables were also included in the model, namely: number of associated centers, number of partner hospitals, average number of managing directors per hospital practicing MSO, an indicator binary variable for all hospitals being under joint leadership, a binary indicator variable for whether the regional hospital group plan contained a complete territorial analysis in its founding contract, a binary variable for a declared percentage of medical teams merged greater than the median, the number of patient pathways included in the RHG project (See Technical Appendix, Supplementary Material). Regarding random effects, each distinct hospital was modeled with a random intercept. Outcomes at the level of each RHG were allowed to vary with time, with the inclusion of a random slope for each RHG. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by including stays not followed by mobility in the analysis. Model performance was evaluated using the Area Under the Curve (AUC),Citation34 also known as the C-statistic.

Missing data was treated by complete cases analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (www.R-project.org) in the Microsoft R Application Network release (MRAN version 4.0.2).

Results

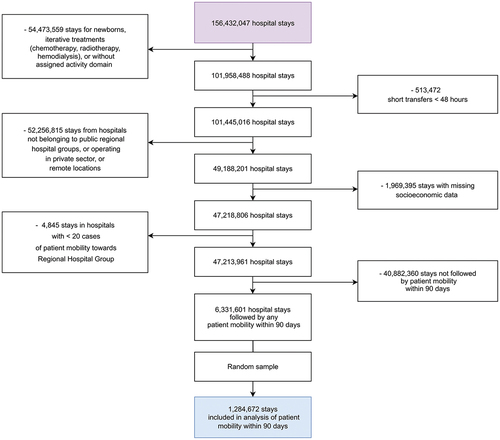

The characteristics of the 136 RHGs are described in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). A total of 1,284,672 stays were included in the analysis of the primary outcome ().

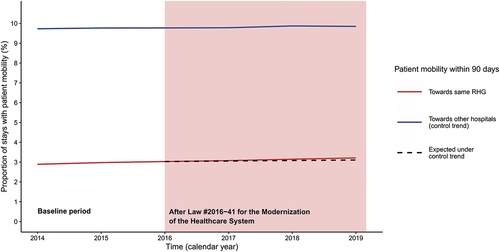

The number of occurrences of patient mobility increased gradually between the period before the policy change and the post-intervention period. Two years before the policy change, there were 237,596 cases of mobility originating from the hospitals that would be included in RHGs, and having another hospital of the same group as destination (year 2014: 2.89% of all stays). The corresponding number in the third year after the policy change (2019) was 290,818 (3.21% of all stays; +0.32%). The four subgroups of interest chosen for the subgroup analysis all exhibited a similar increase in the proportion of within-RHG mobility (see Table S2, Supplementary Material). Stays for respiratory diseases (+0.54%) and cardiovascular diseases (+0.65%) had the highest increases in the proportion of within-RHG mobility after an index stay. The overall progression of mobility toward the same RHG versus toward other hospitals is presented in .

Figure 2. Time series of the proportion of stays followed by patient mobility toward hospitals affiliated to a Regional Hospital Group (RHG) from 2014 to 2019.

The characteristics of stays according to the subsequent occurrence of within-RHG mobility within 90 days, ascertained in the random sample of stays used for the multivariable analysis, are presented in Table S3 (Supplementary Material; See also Table S4 for a detailed analysis according to the activity domain of the stay). Social deprivation (Cramér’s V: 0.32), older age (Cramér’s V: 0.24) and a lower average number of managing directors per hospital (Cramér’s V: 0.27) were strong predictors of mobility toward other hospitals of the same RHG.

Multivariable Analysis by Mixed Effects Logistic Regression

Overall, 1,284,672 stays were included in the multivariable model. Fixed effect regression coefficients are summarized graphically in (see also Table S5 in Supplementary Material). There was a gradual increase in mobility across calendar years during the study in multivariable analysis. The increase was consistent with the changes observed in descriptive data, with more mobility toward hospitals of the same RHG in the post-intervention years. The Odds Ratio (OR) for the year 2019 (reference year: 2014) was 1.132 (95% Confidence Interval 1.067–1.200). The predictive performance of the model was close to excellent, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.767.

Figure 3. Graphical display of variables associated with mobility inside the Regional Hospital Groups in multivariable analysis.

These results imply that if a hypothetical patient with characteristics corresponding to a probability of 22.9% of mobility inside the RHG (i.e., the average probability observed in our sample) was admitted to a hospital in 2014, and then to the same hospital in 2019, with exactly the same characteristics (including age), he/she would see an increase of 2.3% (95% CI 1.2%–3.4%) in the corresponding probability of within-RHG mobility between the two stays (See Technical Appendix, Supplementary Material for additional details on the method used for this calculation). The direction of the change was similar in the sensitivity analysis (Table S6, Supplementary Material).

Discussion

Although there was an increase in patient mobility between the hospitals that would become members of the same RHG over the study years, both the unadjusted and the risk-adjusted indicators for patient mobility did not display any discontinuity in the year in which the French regionalization policy was voted, or in the following years. The progression of the proportion of patients who changed hospitals within the RHG followed a pattern suggestive of a secular trend. A report published in 2020 had noted a similar evolution.Citation11 Regionalization of care in France had already been described in earlier studies, which suggests there could be some degree of endogeneity in the 2016 policy change.Citation35,Citation36 The long-term trend toward regionalization and affiliation of hospitals to broader health systems has also been seen in other countries.Citation37,Citation38

The absence of a clear-cut effect of the policy could be explained by a variety of reasons. Some of the RHGs comprised a few, small hospitals, making it difficult to re-distribute care functions within their geographical zone.Citation11 These small RHGs are known to be situated in zones with difficult socioeconomic conditions.Citation11 The relatively short time that elapsed since the policy change may also have contributed to the relatively small effect observed in the study. The aim of creating RHGs was to help each hospital find its place in a network of actors in which each hospital has recognized strengths and expertise areas, making interhospital transfers almost necessary, even during routine care. However, it is difficult for hospitals to radically transform their healthcare offer in a few months or years, as hospitals also need to be ready to deliver a minimum service, and to have expertise areas varied enough to face the usual emergencies or public health crises, as was clearly illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sharing patients within the usual hospital network was not always possible during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a previous study has shown that patients transferred to other regions had comparable or better outcomes compared to patients transferred to nearby facilities.Citation39 Less than a third of RHGs were led by high-volume teaching centers. Therefore, patients may have continued to be sent to the closest teaching centers, at the expense of nearby within-RHG hospitals, during “normal” periods as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of managing directors per hospital was associated with a lower propensity for patient mobility inside the RHG. This could be due to residual hospital size confounding, as the number of directors could be higher in RHGs with the largest centers, which have strong patient retention capabilities (rehospitalization in the same center being distinct from mobility). Patient and physician preferences are associated with healthcare consumptionCitation40 and could also influence mobility, and this may not be accounted for in the analysis. Some medical specialties are regulated at the interregional rather than the regional level, and may warrant a distinct study. For some regions, it may be impossible or inefficient to refer patients requiring specialized care to hospitals inside the RHG, or they may have counter-incentives such as agreements with tertiary care centers outside of the RHG (e.g. for cardiac surgery). These counter-incentives may have decreased the apparent effect of the policy.

Overall, the modest increase in patient mobility within RHGs observed in our study four years after the reform should not be construed as indicating that the RHG policy has failed. Further studies could determine the type of RGH most successful at implementing the policy. Further research using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods could evaluate the effect of RHGs for selected diagnoses, and ascertain whether the law that created RHGs has achieved its goals in other areas, such as promoting RHG-wide information systems, enabling joint continuous medical education sessions within RHGs, or mutualizing quality insurance systems across hospitals.

Limitations of the Study

Although a comorbidity score was used as an adjustment variable, there could have been variations inside the case mix domains that were considered. Nonetheless, similar studies conducted at this scale used comparable methods of case mix adjustment.Citation41 Finally, we did not have a control group of similar hospitals not affected by the policy change to eliminate shocks due to other causes and that could possibly explain the observed effects of time on patient mobility. However, the reform under study was the main healthcare reform targeting patient mobility during the study period, so it is unlikely that other policy changes could explain our findings.

Conclusions

In this nationwide study, hospitals were reluctant to modify their referral practice in response to a policy change enjoining them to reinforce regional cooperation between hospitals. Regionalization will be endorsed by healthcare professionals and patients only when it becomes clear that the benefits outweigh the costs. It is also possible that a policy with specific quantitative goals for hospital collaboration or health care offer restructuration, with a precise timeline, could have achieved larger effects.

Data Sharing Statement

The stay-level data that support the findings of this study are curated by the French national agency in charge of medical information. These data were used under the MR005 legal framework, and can be made available by the agency in anonymized form for research purposes under certain conditions (www.atih.sante.fr). Aggregated data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request (ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000–0002–8364–6506).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (54.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: Nicolas Parneix (Cour des Comptes) for providing Regional Hospital Group data; Fiona Ecarnot (Université de Franche-Comté) for language editing; the Scientific Committee of the French Technical Agency in charge of Hospital Information for their support of this project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2023.2267256

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carr BG, Martinez R. Executive summary — 2010 consensus conference. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(12):1269–10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00941.x.

- Garwe T, Stewart KE, Newgard CD, Stoner JA, Sacra JC, Cody P, Oluborode B, Albrecht RM. Survival benefit of treatment at or transfer to a tertiary trauma center among injured older adults. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):245–56. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1632997.

- Kaleem S, Lutz MW, Hernandez CE, Kang JH, James ML, Dombrowski KE, Swisher CB, VanDerwerf JD. A triage model for interhospital transfers of low risk intracerebral hemorrhage patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(4):105616. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105616.

- Feazel L, Schlichting AB, Bell GR, Shane DM, Ahmed A, Faine B, Nugent A, Mohr NM. Achieving regionalization through rural interhospital transfer. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1288–96. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.032.

- Needham DM, Bronskill SE, Rothwell DM, Sibbald WJ, Pronovost PJ, Laupacis A, Stukel TA. Hospital volume and mortality for mechanical ventilation of medical and surgical patients: a population-based analysis using administrative data. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2349–54. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000233858.85802.5C.

- Lim S, Kwan S, Colvard BD, d’Audiffret A, Kashyap VS, Cho JS. Impact of in terfacility transfer of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm patients. J Vasc Surg. 2022;76(6):1548–54.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2022.05.020.

- Warner CJ, Roddy SP, Chang BB, Kreienberg PB, Sternbach Y, Taggert JB, Ozsvath KJ, Stain SC, Darling RCI. Regionalization of emergent vascular surgery for patients with ruptured AAA improves outcomes. Ann Surg. 2016;264(3):538–43. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001864.

- Dueck AD, Kucey DS, Johnston KW, Alter D, Laupacis A. Survival after ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: effect of patient, surgeon, and hospital factors. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(6):1253–60. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2004.02.006.

- Goldstone AB, Chiu P, Baiocchi M, Lingala B, Lee J, Rigdon J, Fischbein MP, Woo YJ. Interfacility transfer of medicare beneficiaries with acute type a aortic dissection and regionalization of care in the United States. Circulation. 2019;140(15):1239–50. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038867.

- Brunaud L, Polazzi S, Lifante JC, Pascal L, Nocca D, Duclos A. Health care institutions volume is significantly associated with postoperative outcomes in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28(4):923–31. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-2969-y.

- France. Cour des Comptes. Regional Hospital Groups. Results for years 2014 to 2019 (French version: les groupements hospitaliers de territoire. Exercices 2014 à 2019). Paris (FR): La Documentation Française; 2020. p. 163.

- Sablot D, Leibinger F, Dumitrana A, Duchateau N, Van Damme L, Farouil G, Gaillard N, Lachcar M, Benayoun L, Arquizan C, et al. Complications during inter-hospital transfer of patients with acute ischemic stroke for endovascular therapy. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(5):610–16. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1695299.

- Lomi A, Mascia D, Vu DQ, Pallotti F, Conaldi G, Iwashyna TJ. Quality of care and interhospital collaboration: a study of patient transfers in Italy. Med Care. 2014;52(5):407–14. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000107.

- Gebremichael M, Borg U, Habashi NM, Cottingham C, Cunsolo L, McCunn M, Reynolds NH. Interhospital transport of the extremely ill patient: the mobile intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(1):79–85. doi:10.1097/00003246-200001000-00013.

- Zachrison KS, Amati V, Schwamm LH, Yan Z, Nielsen V, Christie A, Reeves MJ, Sauser JP, Lomi A, Onnela JP. Influence of hospital characteristics on hospital transfer destinations for patients with stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15(5):e008269. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008269.

- Lee BY, McGlone SM, Song Y, Avery TR, Eubank S, Chang CC, Bailey RR, Wagener DK, Burke DS, Platt R, et al. Social network analysis of patient sharing among hospitals in Orange County, California. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):707–13. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.202754.

- Freeman R, Frisina L. Health care systems and the problem of classification. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract. 2010;12(1–2):163–78. doi:10.1080/13876980903076278.

- Böhm K, Schmid A, Götze R, Landwehr C, Rothgang H. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy Amst Neth. 2013;113(3):258–69. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.09.003.

- Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Durand-Zaleski I, Hernandez-Quevedo C. France: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2015;17(3):1–218, xvii. PMID: 26766545

- Lernout T, Lebrun L, Bréchat PH. Trois générations de schémas régionaux d’organisation sanitaire en quinze années : bilan et perspectives. Santé Publique. 2007;19(6):499–512. doi:10.3917/spub.076.0499.

- Mascia D, Di Vincenzo F. Understanding hospital performance: the role of network ties and patterns of competition. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36(4):327–37. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e31821fa519.

- Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins. Plan national d’accompagnement à la mise en oeuvre des GHT à destination des établissements parties. Paris (FR): DGOS; 2016. [accessed 2023 Jan 31]. https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/dgos_plan_accompagnement_mise_oeuvre_ght.pdf.

- Or Z, Bellanger M. France: implementing homogeneous patient groups in a mixed market. In: Busse RGA, Quentin W, Wiley M, editors. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe. New York (NY): Open University Press; 2011. p. 221–41.

- Wong EG, Parker AM, Leung DG, Brigham EP, Arbaje AI. Association of severity of illness and intensive care unit readmission: a systematic review. Heart Lung J Crit Care. 2016;45(1):3–9.e2. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.10.040.

- French National Agency in Charge of Medical Information (ATIH). Diagnosis Related Groups classifications in 2022. Paris (FR): ATIH; 2022 [accessed 2022 Dec 9]. https://www.atih.sante.fr/regroupement-ghm-en-2022.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

- Lix LM, Quail J, Fadahunsi O, Teare GF. Predictive performance of comorbidity measures in administrative databases for diabetes cohorts. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):340. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-340.

- Rey G, Jougla E, Fouillet A, Hémon D. Ecological association between a deprivation index and mortality in France over the period 1997–2001: variations with spatial scale, degree of urbanicity, age, gender and cause of death. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):33. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-33.

- Temam S, Varraso R, Pornet C, Sanchez M, Affret A, Jacquemin B, Clavel-Chapelon F, Rey G, Rican S, Le Moual N. Ability of ecological deprivation indices to measure social inequalities in a French cohort. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):956. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4967-3.

- Chrusciel J, Le Guillou A, Daoud E, Laplanche D, Steunou S, Clément MC, Sanchez S. Making sense of the French public hospital system: a network-based approach to hospital clustering using unsupervised learning methods. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1244. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07215-4.

- Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (DREES). Statistique annuelle des établissements. Paris (FR): DREES; 2022 [accessed 2022 Oct 14]. https://www.sae-diffusion.sante.gouv.fr/sae-diffusion/recherche.htm.

- Casella G, Berger RL. Statistical inference. Belmont (CA): Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning; 2021.

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2007. (Analytical methods for social research).

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2013. ( Wiley series in probability and statistics). doi:10.1002/9781118548387.

- Thibon P, Cornu M, Lamendour N, Guillois B, Dreyfus M. Régionalisation des soins périnatals en basse-normandie : évolution sur cinq ans. J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod. 2011;40(2):156–61. doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2010.11.005.

- De Pouvourville G. L’intégration du système de santé par la région: la genèse de la loi HPST. Actual Doss En Santé Publique. 2011;74:12–16. [accessed 2023 Sept 4]. https://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/Telecharger?NomFichier=ad741216.pdf.

- Reinke CE, Thomason M, Paton L, Schiffern L, Rozario N, Matthews BD. Emergency general surgery transfers in the United States: a 10-year analysis. J Surg Res. 2017;219:128–35. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.058.

- Shrime MG, Iverson KR, Yorlets R, Roder-DeWan S, Gage AD, Leslie H, Malata A. Predicted effect of regionalised delivery care on neonatal mortality, utilisation, financial risk, and patient utility in Malawi: an agent-based modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e932–9. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30170-6.

- Sanchez MA, Vuagnat A, Grimaud O, Leray E, Philippe JM, Lescure FX, Boutonnet M, Coignard H, Hibon AR, Sanchez S, et al. Impact of ICU transfers on the mortality rate of patients with COVID-19: insights from comprehensive national database in France. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):151. doi:10.1186/s13613-021-00933-2.

- Wennberg J, Gittelsohn. Small area variations in health care delivery. Science. 1973;182(4117):1102–08. doi:10.1126/science.182.4117.1102.

- Dormont B, Milcent C. Competition between hospitals: does it affect quality of care. Paris (FR): Editions rue d’Ulm; 2018.