ABSTRACT

This Commentary explores the relationship between Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Health Benefits Package (HBP) design to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in low- and middle-income countries. It emphasizes that while HTA evaluates individual healthcare interventions, HBP reform aims to create comprehensive service sets considering overall population health needs and available resources. Challenges in LMICs include limited local data and technical capacity, leading to reliance on cost-effectiveness estimates from other settings. We suggest a practical approach by combining HTA and HBP elements through a hybrid or compartmentalized method. This approach sets differentiated cost-effectiveness thresholds for specific healthcare platforms or programs (e.g., primary care or essential surgery), aligning priority-setting with organizational considerations, ethics, and implementation strategies. Strong institutions and academic support are vital for evidence-informed priority-setting processes. In summary, HTA can play a pivotal role in designing HBPs for UHC in LMICs, and a compartmentalized approach can enhance priority-setting while considering budget constraints and equity.

Introduction

All countries have signed up to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.8 and have committed to Universal Health Coverage (UHC), but several low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are struggling to achieve UHC. Health reforms along the path to UHC entail securing robust financing for essential services to make them available to everyone who needs them, without financial hardship.

Many countries have found it useful to specify which services are “essential” through a health benefits package (HBP). A HBP can be defined as comprehensive lists of policies, health interventions, and technologies that are cost-effective, promote health equity, protect against financial risk, and are affordable within the given budget constraints.Citation1 By explicitly defining HBPs, countries can establish guarantees for service access and deliver on UHC commitments.

Although defining a HBP is an important and necessary stepping stone for achieving UHC, the process itself involves many difficult decisions about what a country can afford to guarantee through public finance. This involves a series of trade-offs, whereby different often opposing priorities and criteria are balanced against each other to develop an explicit package. Often powerful interest groups and stakeholders hold opposing views on which needs and interventions should have priority. By moving from interest-based and implicit rationing of services to systematic, evidence-based, and transparent priority setting, countries can substantially improve health outcomes, the distribution of those outcomes, and financial protection for a given budget.

Health technology assessment (HTA) is commonly seen as the default approach to excluding or including interventions in HBPs. It can be described as a systematic process used to assess the value, effectiveness, safety, and economic implications of healthcare interventions, technologies, or services.Citation2 It involves multidisciplinary input and helps policymakers and stakeholders evaluate and compare different interventions or technologies, considering factors such as clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, budget impact, safety, ethical implications, and organizational feasibility.

Priority-setting and HBPs for UHC received considerable attention early in the SDG period, and groups such as the International Decision Support Initiative (iDSI) and the Disease Control Priorities (DCP) Network undertook many projects to help build local capacity for HTA in the context of UHC reforms and HBP design.Citation3–5 Nearly a decade has passed since these initiatives began, providing an opportunity to critically reflect on the processes, methods, and tools that are being used for HBPs. In this paper, we consider the role of HTA in HBP design and reform in LMICs. Additionally, we address a few specific concerns related to HBP implementation.

Health Technology Assessment and Health Benefit Package Design: Are They the Same?

Since HTA and HBP processes both rely heavily on generating and using economic evaluation evidence, it is tempting to use these two terms interchangeably. However, they are conceptually different, at least in the context of LMIC health systems. While HTA assesses individual interventions (usually brand-new technologies) on a case-by-case basis, the objective of HBP reform is to design a comprehensive set of services. Both approaches consider multiple criteria, but HTA places greater emphasis on clinical and economic factors. The HTA approach examines the specific characteristics and impacts of individual interventions, whereas the HBP approach takes a macro-level perspective, considering overall population health needs, health system objectives and strategies, and available resources.Citation14

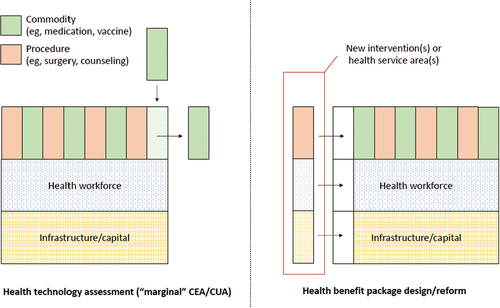

Some of the conflation of these two terms probably arises from the fact that in high-income countries, where HTA institutions have been in place for many years, health systems are more mature and HBP modifications happen continually through HTA processes as new technologies enter the market. By contrast, many LMICs do not currently offer a comprehensive set of services with full coverage, especially for emerging topics like noncommunicable diseases and injuries. Reforms in HBP occur sporadically (e.g., every five or 10 years) and often in parallel to broader health sector reforms that accompany changes in governments.Citation6 Importantly, HBP reforms may involve restructuring health service delivery and adding a range of new interventions and programs. In general, HTA seeks to analyze the marginal value for money of displacing an existing technology with a new technology under the assumption of a stable health budget over time. By contrast, HBP design, in the context of LMICs, seeks to build out a developing health system to provide an ever-expanding range of services, under the assumption of growth in health sector resources over time. illustrates the different implications of HTA and HBP reform for health systems.

Figure 1. Distinguishing HTA processes from HBP processes.

Even when the mandate for HBP reform is clear, the design of an HBP is difficult to accomplish in practice. Most countries lack high-quality, locally relevant evidence and have limited institutional capacity for conducting a sufficient number of economic evaluations. Further, HBP processes are often de-linked from financing and other health system functions such as service delivery, stewardship, monitoring, and resource generation, limiting their implementation.Citation7

In the absence of local data and technical capacity, the fallback approach for HBP design is to take cost-effectiveness estimates (usually from HTAs) from other settings.Citation8 This can be problematic. An HTA-type analysis often assumes a reasonable standard of care in the comparator scenario, whereas the standard is often “no care” in less-developed health systems. Additionally, the cost of implementing a medical technology in a less-developed health system can be much higher than in a mature system if the necessary infrastructure and human resources are not already in place.Citation9 The lack of methods and tools for accurately transferring cost-effectiveness estimates across settings, and modeling the cost implications of complex health system reforms (via HBPs) is a major problem and needs to be a priority for research. In the mean time, practitioners will continue to rely on international HTA studies in HBP design, though we argue they should do this with great caution.

With all these limitations considered, HTA processes do offer some strengths that HBP processes can draw on. The traditional elements of HTA are well-suited for closing the gaps between priority setting, HBP design, and implementation: They have a more systematic approach to ask the right questions, assess organizational impact, analyze ethical issues, and distinguish clearly between assessment vs. appraisal. Building local HTA capacity gives countries a solid methodological and procedural foundation for HBP reform.

Health Technology Assessment and Model Health Benefit Packages in the Disease Control Priorities Project

The Disease Control Priorities (DCP), published by the World Bank Group, has historically provided periodic reviews of the most up-to-date evidence on cost-effective, equity-enhancing interventions that address the major health needs in LMICs. The objective of DCP has been to provide evidence that can be a starting point for local policy deliberation, including on HBP design. DCP3 also introduced the “extended cost-effectiveness analysis” method to incorporate equity and financial protection considerations alongside cost-effectiveness considerations.Citation10

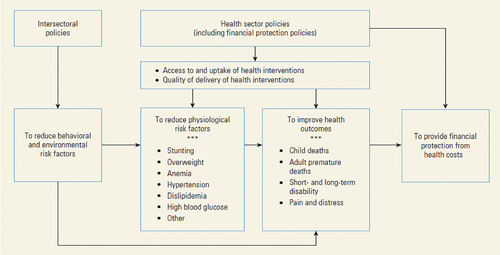

In one sense, the DCP project can be seen as a comprehensive summary of numerous HTAs. The 3rd Edition (DCP3) included nine volumes that presented 21 essential intervention packages, each of which addressed the concerns of a major professional community and contained a mix of intersectoral policies and health sector interventions (). To produce a unified and harmonized model health benefits package for UHC systems, Watkins and colleaguesCitation9 extracted all health sector interventions contained in the 21 intervention packages. Interventions that improve health but are implemented by other sectors, such as tobacco taxes (ministry of finance) and road safety measures (ministry of transportation), were analyzed elsewhere in DCP3.Citation12 Watkins and colleagues harmonized definitions, removed duplicates, and classified each intervention in multiple dimensions, leading to a model HBP containing 218 interventions, termed “essential UHC”,Citation11,Citation13,Citation14 Since then, several countries have used these recommendations in local policy applications.Citation15,Citation16,Citation17 Throughout the DCP-related initiatives there has been an intentional effort to align DCP recommendations to local data, skills, and experience and develop local capacity in priority-setting. Still, DCP evidence should be viewed as a stepping stone on the path toward a comprehensive, locally driven HTA approach. The latter includes other elements, such as consideration of organizational, legal, and ethical dimensions, that are outside the scope of international normative efforts to address.

Figure 2. DCP3 conceptual framework for health-related policies (source).Citation11

The next edition of DCP will draw on lessons learned and include more of the elements that HTA can provide. The aim will be to provide a useful bridge between HTA and HBP processes and to develop new methods relevant to HBP design, drawing on the best from HTA. Additionally, DCP feedback from decision makers in different countries and social contexts has provided insights about how HTAs and other economic evidence are being used in practice.Citation18 These real-world lessons will also inform the development and content of DCP4. It is important to engage in equitable partnerships with governments and institutions that are engaged in revising HBPs, help to strengthen local capacity, and foster inclusive and open deliberations about priority setting.Citation19

Through collaboration and capacity strengthening in a select number of LMICs, DCP4 will summarize, produce, and help translate economic evidence into better priority setting for UHC and for intersectoral collaboration on health issues. It will also address global threats to health and inform the agenda for international collective action on health.Citation5

Blending HBP and HTA Approaches in Compartmentalized Analyses

If there is high-level political commitment to UHC, explicit priority setting, and institutionalization of HTA, the HBP approach and HTA methods can complement each other. For example, both could make use of the same pre-specified criteria such as burden of disease, cost-effectiveness, equity impact and financial risk protection.Citation20

Health technology assessments can help decision makers in adding or removing a specific service to the current service mix. A core criterion is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of a new intervention compared to the existing standard of care. Incremental analysis supports decision making at the margin, as shown in . If interventions are not ranked by ICER (i.e., a league table), the decision about whether to include or exclude a technology relies on implicit or explicit cost-effectiveness thresholds. Recommendations, or price negotiations, could be made to the cost of the new technology to reduce the ICER below the cost-effectiveness threshold.Citation21 In HTA, other considerations than cost-effectiveness can be introduced. For example, concerns for the worse off in terms of health or the aim of reducing socioeconomic inequities can lead to severity- or equity-adjusted ICERs.Citation21,Citation22

A recent paper by Baltussen and colleaguesCitation23 suggests that the two approaches discussed here called sectoral analysis (HBP) and incremental analysis (HTA) can be combined in a hybrid approach. We propose a variation on this hybrid approach called “compartmentalized analysis,” intended to be a pragmatic approach to priority setting within health sub-sectors or program areas. Compartmentalized analysis is broader than HTA, but narrower in scope to HBP reform. For example, HTA deals with specific questions such as whether to reimburse a new cholesterol-lowering drug for persons at high risk of cardiovascular disease, whereas HBP deals with broad questions of health system development and maximization (and fair distribution) of health overall.

Compartmentalized analysis would fill a gap, for example, what is the optimal suite of interventions to address cardiovascular disease in a given context with a given budget? (In this case, the “compartment” is a cardiovascular disease program.) In our experience, compartmentalized approaches are in demand from policymakers who want to define things such as an essential surgery package, a primary care package, or an essential cancer package for the sector. Compartmentalized analyses could be more helpful than ad hoc single-item HTAs, and less daunting than a comprehensive HBP reform process that covers the whole health sector. Additionally, compartmentalized analysis could address HBP policy questions outside the scope of conventional HTA, such as the tradeoff between investing in a new type of cholesterol medication vs. investing in expanded coverage and quality of existing cholesterol medications, both of which could be relevant options for a cardiovascular disease program. In DCP4, we plan to develop analytical tools that are flexible enough to address a range of HBP questions such as these. In practice, compartmentalized analyses would place greater analytical responsibility on technical working groups (e.g., disease experts within sub-sectors) who then provide recommendations to health planners tasked with allocating resources across the sub-sectors. The former task is technocratic, whereas the latter task is political and strategic.

By being a less ambitious approach, compartmentalized analysis could draw on the strengths of both the HBP package approach and the HTA approach. It is imperative to continue to rely on cost-effectiveness thresholds that could be adjusted by other priority-setting criteria like severity of disease or equity. Thresholds are critical for two reasons. First, fair and efficient priority setting requires that thresholds are consistent across disease groups, conditions, risk factors, interventions and packages. For example, the interventions included in an essential cancer package should satisfy the same threshold as the interventions included in an essential surgery package. If there are relevant reasons for adjusting the threshold for cancer services, these reasons should be applied universally across all packages. In this sense, compartmentalized analysis borrows strength from the HBP approach.

Second, the use of predefined cost-effectiveness thresholds simplifies the task substantially. There is no need to rank-order all potential interventions in a comprehensive sector-wide package; the analysts would focus only on the cost-effectiveness of the subset of interventions relevant to the health program. Relying on thresholds for a select number of interventions, analyzed even at different points in time, is an obvious advantage and could ease the workload on institutions responsible for this type of analysis. In this sense, compartmentalized analysis borrows strength from the HTA approach. Defining the right cost-effectiveness threshold is a non-trivial task, but the concept and methods have now become well established.Citation24 With expanding budgets, thresholds should be revised accordingly.

Conclusion

This paper explored the relationship between HTA and HBP design and underscores the need for innovation in methods and tools (e.g., DCP4) and the approach to priority-setting itself through hybrid or compartmentalized approaches.

As a well-established approach to priority setting, HTA has much to offer other approaches that are focused on the needs and contexts of low- and middle-income countries. First, using thresholds in compartmentalized analysis to determine which interventions to prioritize can be a helpful approach. It allows institutions to make decisions based on specific criteria, even at different times. This advantage can potentially reduce the workload on these institutions. Second, it would introduce systematic rigor in synthesizing evidence and evaluating impacts beyond mere cost-effectiveness. Third, it would establish strong connections between priority setting and organizational considerations, including addressing health personnel requirements. Fourth, it would align clinical practice guidelines with cost-effectiveness thresholds and facilitate improved health financing by considering factors such as budget impact, equity, and financial risk protection.

This work requires strong institutions with trained people that are devoted to this demanding work, and a strong commitment to evidence-informed explicit priority setting through open and inclusive processes. It also requires support from independent academic institutions providing impartial analysis that can inform and critique the politics of priority setting. We acknowledge that policymakers are the owners and stewards of HBPs, and they often make decisions that do not align with what technical experts would recommend. However, our hope is that by improving the methods and tools used in HBP design, such as the hybrid or compartmentalized approach, we can empower policymakers to weigh the evidence more systematically and make decisions that are consistent with the values and preferences of the general public.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

- World Health Organization. Institutionalizing health technology assessment mechanisms: a how to guide. Geneva: World Health Organziation; 2021.

- Reich MR. Introduction to the PMAC 2016 special issue: “Priority setting for universal health coverage”. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):1–6. doi:10.1080/23288604.2016.1125258.

- The International Decision Support Initiative (iDSI). [accessed 2023 Sept 12]. https://www.idsihealth.org.

- Fourth Edition of Disease Control Priorities (DCP-4). [accessed 2023 Sept 12]. https://www.uib.no/en/bceps/156731/fourth-edition-disease-control-priorities-dcp-4.

- Bukhman G, Mocumbi AO, Atun R, Becker AE, Bhutta Z, Binagwaho A, Clinton C, Coates MM, Dain K, Ezzati M, et al. The lancet NCDI poverty commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. Lancet. 2020;396(10256):991–1044. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3.

- Reynolds T, Wilkinson T, Bertram MY, Jowett M, Baltussen R, Mataria A, Feroz F, Jama M. Building implementable packages for universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 1):e010807. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010807.

- Vellekoop H, Odame E, Ochalek J. Supporting a review of the benefits package of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022;20(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12962-022-00365-0.

- Hauck K, Thomas R, Smith PC. Departures from cost-effectiveness recommendations: the impact of health system constraints on priority setting. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):61–70. doi:10.1080/23288604.2015.1124170.

- Verguet S, Kim JJ, Jamison DT. Extended cost-effectiveness analysis for health policy assessment: a tutorial. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(9):913–23. doi:10.1007/s40273-016-0414-z.

- Watkins DA, Jamison DT, Mills T, Atun T, Danforth K, Glassman A, Horton S, Jha P, Kruk ME, Norheim OF, et al. Universal health coverage and essential packages of care. In: Jamison D, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, and Mock C, editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. Vol. 9. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2017. p. 43–65.

- Watkins DA, Nugent R, Saxenian H, Yamey G, Danforth K, Gonzalez-Pier E, Mock CN, Jha P, Alwan A, Jamison DT. Intersectoral policy priorities for health. In: Jamison D 3rd, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, and Laxminarayan R, editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. Vol. 9. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2017. p. 23–41.

- Jamison DT, Alwan A, Mock CN, Nugent R, Watkins D, Adeyi O, Anand S, Atun R, Bertozzi S, Bhutta Z, et al. Universal health coverage and intersectoral action for health: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1108–20.

- Norheim OF. Ethical priority setting for universal health coverage: challenges in deciding upon fair distribution of health services. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):75. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0624-4.

- Eregata GT, Hailu A, Geletu ZA, Memirie ST, Johansson KA, Stenberg K, Bertram MY, Aman A, Norheim OF. Revision of the Ethiopian essential health service package: an explication of the process and methods used. Health Syst Reform. 2020;6(1):e1829313. doi:10.1080/23288604.2020.1829313.

- Alwan A, Majdzadeh R, Yamey G, Blanchet K, Hailu A, Jama M, Johansson KA, Musa MYA, Mwalim O, Norheim OF, et al. Country readiness and prerequisites for successful design and transition to implementation of essential packages of health services: experience from six countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 1):e010720. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010720.

- Baltussen R, Mwalim O, Blanchet K, Carballo M, Eregata GT, Hailu A, Huda M, Jama M, Johansson KA, Reynolds T, et al. Decision-making processes for essential packages of health services: experience from six countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 1):e010704. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010704.

- Alwan A, Yamey G, Soucat A. Essential packages of health services in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: what have we learnt? BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl 1):e010724. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010724.

- Norheim OF. Disease control priorities third edition is published: a theory of change is needed for translating evidence to health policy. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):771–77. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2018.60.

- Verguet S, Hailu A, Eregata GT, Memirie ST, Johansson KA, Norheim OF. Toward universal health coverage in the post-COVID-19 era. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):380–87. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01268-y.

- Tranvag EJ, Haaland OA, Robberstad B, Norheim OF. Appraising drugs based on cost-effectiveness and severity of disease in Norwegian drug coverage decisions. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219503. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19503.

- Cookson R, Culyer AJ, Griffin S, Norheim OF, editors. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis. Quantifying health equity impacts and trade-offs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020.

- Baltussen R, Surgey G, Vassall A, et al. Designing health benefit packages for universal health coverage – should countries follow a sectoral, incremental or focused approach? Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2023;21(1):75. in press. doi:10.1186/s12962-023-00484-2.

- Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016;19(8):929–35. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017.