ABSTRACT

Countries pursuing universal health coverage must set priorities to determine which benefits to add to a national health program, but the roles that organizations play are less understood. This article investigates the case of the formation of an organization with a mandate for choice of technology for public health interventions and priorities, the Health Technology Assessment India. First, we narrate a chronology of agenda setting and adoption of national policy for organizational formation drawing on historical documentation, publicly available literature, and lived experiences from coauthors. Next, we conduct a thematic analysis that examines windows of opportunity, enabling factors, barriers and conditions, roles of stakeholders, messaging and framing, and specific administrative and bureaucratic tools that facilitated organization formation. This case study shows that organizational formation relied on the identification of multiple champions with sufficient seniority and political authority across a wide group of organizations, forming a coalition of broad base support, who were keen to advance health technology assessment policy development and organizational placement or formation. The champions in turn could use their roles for policy decisions that used private and public events to raise priority and commitment to the decisions, carefully considered organizational placement and formation, and developed the network of organizations for the generation of technical evidence and capacity building for health technology assessment, strengthened by international networks and organizations with financing, expertise, and policymaker relationships.

Introduction

Organizations are involved in all health systems, including organizations classified by their function (e.g., provider, payer, or regulatory organizations)Citation1 or organizations classified by the type (e.g., government or non-governmental). There are various studies examining the competition of provider organizations as well as payer organizations.Citation2,Citation3 But the origins and development of governmental organizations in becoming institutions has been argued to be less studied.Citation4 Governmental organizations are involved in different roles in the health system, such as a national payer that may make payments to healthcare providers or even to other private payers, as well as public health authorities that deliver essential public health services. Recognizing that not all organizations are institutions, recent work has examined the ways in which organizations become institutions, defined as having “developed a consistent and effective way of working, which is strongly valued by internal and external stakeholders.”Citation5 Further, there is need to not only examine organizational failures but also organizational successes and accomplishments.Citation6,Citation7 The ways in which organizations emerge or are created and formed, or how they are modified and change over time is a process of organizational development. How do organizations concerned with health technology assessment (HTA) policy development also develop over time and become institutions?

Of the different kinds of governmental organizations working in the health care sector, one type of governmental organization focuses on policy development for HTA and priority setting, which we call “HTA policy development.” Countries pursuing universal health coverage through expansion of health care benefits included in national programs are invariably confronted with questions about which benefits to add. Such priority setting processes can have major ramifications for the costs and benefit of care delivered. These processes are not merely technical but also highly political and organizational exercises. The creation or emergence of a governmental organization or agency conducting and regulating HTA can serve as a solution or “intervention” that facilitates HTA policy development.

Several cases of governmental organizations conducting HTA are well known, such as the United Kingdom’s National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as well as Thailand’s Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) in the Ministry of Public Health. The International Decision Support Initiative (iDSI), which currently has its secretariat at the Center for Global Development (CGD), is a network of multiple organizations that have contributed to HTA policy development internationally as well as in-country HTA organizational development. Yet the particular powers, mandates and authorities, scope of functions and activities, as well as organizational design of governmental organizations involved in HTA can vary across countries, with these characteristics emerging interdependently as the organization is developed.

This study explores how a newer governmental organization for HTA policy development, the Medical Technology Assessment Board (MTAB) and its secretariat Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn), emerged as the national HTA agency in India. In the policy cycle of agenda setting, adoption, and implementation, and evaluation, this study focuses on the first two parts—the agenda setting and adopting the agenda to better understand how these factors led to the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn.Citation8 Using qualitative analyses, including historical documentation and lived experiences (namely of the coauthors based in India), this article seeks to understand organizational development by understanding the windows of opportunity, enabling factors, barriers, and conditions, including roles of different players and coalitions, the kinds of messaging and framing used to advance agendas, and where relevant, specific administrative and bureaucratic tools or rules. The study may offer broader lessons about how to create a public organization with the mission to serve the public’s interest, including priority setting.

Data and Methods

This study uses two frameworks. The first framework is used for this special issue, which considers windows of opportunity, enabling factors, barriers and conditions, roles of stakeholders, messaging and framing, and specific administrative and bureaucratic tools that facilitated organization formation. We use Campos and Reich (2019) as the second framework, which examines the roles of interest groups, bureaucrats, budgets, leadership, beneficiaries, and external actors.Citation9 Both of these frameworks are concerned with the use of political economy analysis and the ways in which stakeholders influence policy development. The special issue’s framework emphasizes specific organizational features and tools used for policy development (e.g., windows of opportunity, messaging and framing, and specific administrative and bureaucratic tools), whereas the second framework emphasizes the role of different kinds of stakeholders in influencing and implementing policy processes, for which organizational development is one aspect of implementation.

For this study, we conducted a two-part methodology. The first part relied on a historical document review based on materials and documents from the iDSI, an organization whose purpose is to develop partnerships to share knowledge on HTA and priority-setting to advance evidence-based decision-making, including grant proposals, grant reports, memos, research publications, and other documents archived by CGD. This review of historical documentation is used to confirm the facts of organizational formation of the MTAB and HTAIn with key informant-coauthors (Abha Mehndiratta, Non-Resident Fellow, Center for Global Development; Shankar Prinja, Professor of Health Economics, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research; T. Sundararaman, Independent Consultant, former Executive Director of National Health Systems Resource Centre; and Soumya Swaminathan, Independent Consultant. Former Secretary, Department of Health Research) and narrate a chronological timeline of events leading up to the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn. Next, in order to answer the overarching question of this study, which is to examine how the MTAB and HTAIn were created, we describe the historical chronology based on facts, on which we conduct a thematic analysis to qualitatively explore the different factors leading to organizational formation.

History of the Formation of the MTAB and HTAIn

presents a concise, descriptive summary of critical events that created momentum for the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn and HTA policy development in India, beginning in 2012. is curated from a longer chronological list of documents and events, presented in Appendix A1, for which events reflect high-level national government policy pronouncements or decisions that were crucial for HTAIn’s formation.

Table 1. List of critical events that created momentum for the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn and HTA policy development in India.

Prior to 2012, there were efforts to generate local evidence to inform decision-making. While there was some synthesis and translation of evidence on clinical effectiveness into clinical guidelines, there was a lack of systematic use of these tools for scaling up interventions for public health and public policy, which required a different evidentiary basis than clinical implementation.

The government of India made an explicit commitment in 2012–13 to HTA which was expressed in the 12th Five-Year Plan prepared by the then-Planning Commission (later renamed the NITI Aayog). This plan outlined that “on the lines of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) International, the Department of Health Research (DHR) would develop the expertise to assess available therapies and technologies for their cost-effectiveness and essentiality, and formulate and update, on a regular basis, the Standard Treatment Guidelines, and suggest inclusion of new drugs and vaccines into the public health system.”Citation10 The DHR is a department within the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India.

Subsequently, in 2013, a Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of India and the UK’s NICE International was signed.Citation12 In 2013, at a Parliamentary Standing Committee, the DHR put forth proposals on the areas of work, including that the DHR would “set up a technology assessment board consisting of economists, social scientists, public health professionals, and other … specialists whereby new technologies can be scientifically assessed for cost efficacy before introduction/procurement for affordable health care”Citation11 Subsequent policy documents mentioned the need to set up an institution or organization similar to NICE.

Furthermore, the National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC), as part of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Medical Technologies, in collaboration with Amrita Institute in Kochi and Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) Chandigarh, helped to support a HTA certificate course in 2014. The training courses focused on building capacity and training on how to conduct a systematic review of evidence, with less emphasis on collecting cost data and conducting costing and economic evaluation. In 2014, these courses published “HTA studies,” a compilation of the culminating study projects from students who had participated in the two courses.

In 2014, the Gates Foundation awarded a grant to NICE International and iDSI, which collaborated with NHSRC in order to work on standard treatment guidelines.

In 2014, Indian leaders made use of the executed 2013 India-UK MOU, through a study visit to meet NICE leadership, better understand the NICE governing structure, its remit, the operation of its committees, the basics of HTA as a methodology, and the generation and understanding of cost-effectiveness evidence. The Indian delegation, represented by the DHR, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and National Health Systems Resource Center (NHSRC), included a former Director General of Health Services (DGHS, equivalent to the rank of secretary of health) as a senior policy maker, the Joint Secretary of DHR, and other staff from ICMR and NHSRC, and was funded by the iDSI grant.

In 2014, the DHR hosted an awareness-building conference workshop in collaboration with the World Bank, entitled “Better Decisions for Better Health: Priority Setting and Health Technology Assessment for Universal Health Coverage in India.” Present at this event were both secretaries (the Secretary of Health and the Secretary for DHR), and the High Commissioner for the UK to India, among others. The iDSI grant and iDSI staff supported the DHR in hosting this event.

Three stakeholders attended this conference workshop who were engaged Indian academic leaders in medicine, public health, and health economics. One stakeholder was a professor and head of the department at All-India Institute for Medical Sciences (AIIMS) who had advocated for a NICE-like institute, not only to generate HTA evidence but also to provide good clinical guidance for physicians and other health professionals. The second key stakeholder, a former NHSRC director, also held HTA workshops and advocated for the setting up of an organization that provides cost-effectiveness evidence. The third key stakeholder, an assistant professor from PGIMER Chandigarh, had begun carrying out extensive technical health economics research in HTA and would later join the government to participate in HTA policy development and organizational development in India.

In 2014, NHSRC published a report on the HTA landscape in India called “Compendium of Health Technology Assessments: Health Technology Assessments,” as a culmination of the early HTA studies in India while emphasizing the need for more HTA studies to be conducted.

In 2015, senior leaders from the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare attended the Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC), in Bangkok, Thailand, which included a side meeting on countries in the region developing HTA capabilities, organized by the government of Thailand, Ministry of Public Health, Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP).

Organizational mapping conducted on the situation of HTA in India indicated that DHR leadership had yet to fully engage by early 2015, potentially in part due to impending leadership retirement, resulting in a leadership vacuum of six months until the successor to the DHR secretary was named. In September 2015, a new DHR secretary joined, resulting in a different approach and increased willingness to work on HTA policy development. By the end of 2015, new DHR leadership called for and led a Joint Steering Committee to guide the formation of the national HTA body, with support from iDSI international partners. A landscape and mapping of priority setting stakeholders was also undertaken by NICE International in 2015 (see Appendix A2).

In 2016, the annual PMAC conference took place with the theme of HTA and priority setting. HITAP was key to planning and organizing the PMAC event. Several high-level policy makers were invited and attended, including the DHR secretary who was a plenary speaker, and a senior staff member from the NHRSC. During PMAC, the DHR secretary shared India’s public commitment to establish a Medical Technology Assessment Board in India and decided to hold an event to bring Indian stakeholders together about the vision for the MTAB.

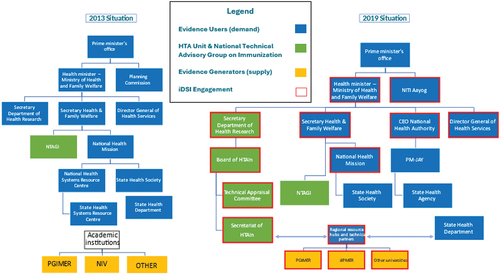

The DHR secretary convened a three-day workshop over July 25–27 with high-level participants, including the Secretary of Health and the DGHS, and two Ministers of State (akin to deputy ministers of health at the national level).Citation30 The DHR secretary also invited the Vice Chair of NITI Aayog, who came in for the closing of the workshop. One of the focal discussion topics of this workshop was the issue of the institutionalization of HTA through the MTAB and its organizational placement. presents the two organizational charts in 2013 and 2019 to visualize the before and after of the formation of the MTAB.

Figure 1. MOHFW organizational charts before and after HTAIn formation: 2013 and 2019.

Notes: Boxes highlighted in red reflect the network development. PM-JAY refers to Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana, the national health insurance program. JIPMER refers to Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research. PGIMER refers to Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research. CMC Vellore refers to Christian Medical College Vellore. Regional resource hubs and technical partners were established and expanded after the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn.

In 2017, the National Health Policy (NHP) of 2017 continued to reinforce the importance of an organizational body to generate HTA evidence and the importance of HTA evidence to develop clinical guidelines.Citation28 A first draft of the NHP was released in the public domain in December 2015, which began high-level discussion on the topic and was approved in August 2017 after extensive public consultation.

After the workshop in 2016, the DHR Secretary directed the new Joint Secretary to work on establishing the Board including identifying institutions that have HTA capacity, supporting the development of the Terms of References (TORs) for staffing positions, and planning the organizational structure and design.Citation31 A questionnaire was sent to Indian organizations in order to map out the stakeholders that would later become the Regional Resource Centers (RRCs) that would be supported by the future MTAB. These activities were led by DHR with support from iDSI.

In March 2017, the DHR Secretary prepared and submitted the Cabinet Note for approval and funding for MTAB. This Cabinet Note spelled out the structure of MTAB and its role and function, while crucially referring to past major policy pronouncements such as the 12th Five-Year Plan, the Parliamentary Standing Committee and the National Health Policy of 2017 to signal past political support and buy-in. The Cabinet Note was sent with a funding amount to the Ministry of Finance and approved by March 2017. By April of 2017, the Joint Secretary had fully established the team with more than a dozen total staff in the secretariat and a senior scientist reporting to the Joint Secretary. In 2017, the MTAB was established with the secretariat named as HTAIn and with a full organizational structure and board, technical appraisal committee, and secretariat.

Thematic Analysis

To understand generalizable lessons for how an HTA organization can emerge, we examine this case study to understand of roles of stakeholders, such as government or bureaucratic leaders, and their ability to create or use windows of opportunity for policy adoption and implementation, and specifically policies that create the organization itself. We also identify specific administrative and bureaucratic tools they used and explored the ways they created enabling factors and tackled barriers to organizational creation.

Multiple Champions Creating Multiple Windows of Opportunity

The processes and histories leading up to 2017 with the emergence and creation of the MTAB and HTAIn reflect the role of high-level policy documents and committees creating political authority and approval to proceed with government leadership, the use of international to draw attention and create international networks for support, as well as the supplemental roles of international donor assistance, as shown in the high-level events in . The timelines reflect the persistent and annual building of urgency, gaining buy-in, and growing a network of supporters and champions of HTA.

The express commitment to HTA was manifested through the 12th Five-Year Plan in 2012, as a high-level national policy document published by the Planning Commission (now called the NITI Aayog). This plan expressed a need to establish an independent organization, building on prior activities and networks to foster political priority, distinct from ad hoc expert committees dependent on development partners. The urgency and momentum continued to grow with wins each year as shown in and Appendix A1. Despite the repeated momentum of events, the MTAB and HTAIn did not form until the government expressed leadership and ownership through DHR.

Amidst the landscape of multiple supporters and champions of HTA, the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn depended crucially in 2015 on the emergence of a key supporter within the government, with the new leader and DHR secretary. The new DHR secretary focused the needs of the MTAB on avoiding dependence on an ad hoc expert committee and instead focused on establishing a process, institution, and system that solicits and addresses questions on technology choice as well as concerns on priority setting. Under the new leadership, several key windows of opportunity emerged from the new urgency and commitment to create MTAB: the Joint Steering Committee to guide the creation of the organization in 2015 as well as a pivotal three-day workshop in 2016 with the necessary high-level senior policy makers and political appointees who were able to support the creation of the organization as well financial resources to maintain and support the organization.

A scientist-bureaucrat, the new DHR secretary was familiar with the importance of gaining internal support and buy-in, as demonstrated by holding a workshop with key stakeholders. The secretary was also versed with administrative tools such as the Cabinet Note to the Ministry of Finance in order to obtain approval and funding for the MTAB and HTAIn, as well as the need to map out organizational structures () in the MOHFW to help justify the organizational placement of the MTAB and HTAIn within the DHR. Importantly, the Cabinet Note was able to cite and refer to past policy documents in support of HTA to signal successive political support and buy-in.

There were questions about organizational placement and participants; see . For example, separately, the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI), a technical committee that makes decisions on inclusions of vaccines, administered by the MOHFW and involved another academic institution whose involvement was contested due to concerns of foreign influence. Amidst a backdrop of political change in 2014, the NTAGI was permanently placed in the MOHFW in its original form as an ad hoc expert committee set up by a government order for a specific function with its secretariat role being performed by the MOHFW. In designing HTAIn’s organizational placement, NTAGI’s involvement with an external non-governmental academic institution was considered as an alternative organizational form. However, the experience of NTAGI in involving an external academic organization raised concerns about decreased government ownership over the process, making NTAGI susceptible to political change and criticism about international philanthropic influence. The changes experienced by NTAGI further strengthened the rationale to place HTA within the DHR, as shown .

Placing the MTAB within the DHR not only shielded it from the risks of international influence but potentially any influence outside of the government. Indeed, placing HTA within the DHR could be interpreted as a “de-risking” strategy, namely, to reduce the risks of non-governmental or external influence in an industry that, by definition, has numerous stakeholders including health care providers, payers, pharmaceutical companies, medical device manufacturers, physicians, and of course patients. Other de-risking strategies included dismantling the international steering committee established in 2015–16 once the MTAB functions and structures were in place, as well as relying on Indian academic centers independent from international donor funding.

Building a National Governmental Ecosystem

The “HTA ecosystem” within India developed with multiple organizations influencing and developing the formation and growth of the MTAB and HTAIn organization, with government leadership as essential. These organizations included DHR as the future location of the MTAB and HTAIn; different units and leaders within MOHFW who came to be supportive of the concept of HTA and of creating an organization; NHSRC and PGIMER as government-adjacent institutions that participated early in conducting training and capacity building activities for carrying out the HTA studies themselves.

Champions within each organization, with their respective own networks and connections facilitated relationships and linkages, supported the addition of HTA to multiple high-level policy documents leading up to the formation of MTAB. Having HTA mentioned in the 12th Five-Year Plan was crucial as it demonstrated national leadership from the highest levels of government, namely, the Prime Minister’s office. The explicit mention and inclusion of NICE, cost-effectiveness, and evidence in 12th Five Year Plan also hints at the role of national leadership in understanding international best practices and reaching out to international networks for necessary expertise to work to overcome specific challenges.

Repeated interactions, meetings, and cross-connections between government policy makers, academics, as well as those from international organizations, led to the emergence of a network of sensitized individuals across organizations in India. The presence of multiple champions across institutions, who were able to communicate messages repeatedly and reinforce the importance of HTA also helped to build a policy discourse in favor of HTA. Different events served as mini-policy windows, adding a depth of understanding even among the champions, such as attendance to PMAC or to study visits to HTA institutions.

Once that mandate was established in 2015–16 with the Cabinet Note submitted by the new DHR secretary with the support and approval of senior policy makers, the secretariat in DHR began to focus on creating credible organizational structures and processes which would make consideration of evidence for policy routine (i.e., as part of policy adoption) as well as creating a network of organization for generation of technical evidence, capacity building, along with facilitating international networks, linkages, and exchange (i.e., as part of policy implementation). The Cabinet Note was not intended to be a long-term source for financing the MTAB but enabled the immediate creation of an organization and required annual approval since 2017. In recent years, the DHR worked to build a whole network of resource centers, mainly comprised of academic institutions with the capacity to conduct HTA as well as approval by the Departure of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, in 2023 for HTAIn to transition from a program to an additional office attached to the DHR, all ensuring long-term sustainability and institutionalization.

In parallel, the development and growing presence of trained professionals in HTA in India alongside the demonstration of the value of HTA through HTA studies from both local and international experiences further helped to convince policy makers of the value of HTA. As of 2023, there are 18 such resource centers which receive formal funding from the HTAIn secretariat as well as another ten technical partners that participate without the MTAB and HTAIn funding. This network is supported by the MTAB and HTAIn core budget for studies, capacity building, setting up data systems (e.g., cost data, EQ-5D value sets), as well as process and guidelines standardization, with PGIMER serving a leading role as an academic institution.

Supportive Assistance from International Actors

Several international actors were involved at various stages of the formation and development of the MTAB and HTAIn including iDSI and NICE. International actors played different kinds of roles, including building awareness and demand, gaining buy-in, facilitating social and professional networks, and creating linkages to international cooperation and exposure including through study visits (e.g., to the UK) or conference workshops, such as those hosted in India or the two PMAC conferences held in 2015 and 2016.

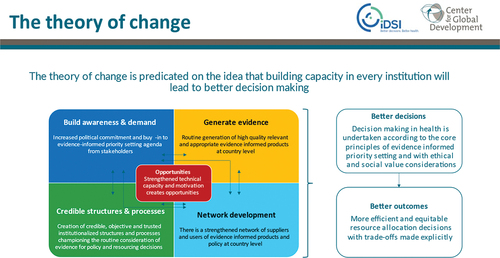

While different international organizations were involved in advocating for HTA, the role of iDSI as an inclusive network for a variety of international organizations to engage on issues related to HTA needs special mention. iDSI conceptualizes its role as creating a network framework to enable several functions of awareness, advocacy, evidence generation, capacity building, and international linkages. Its theory of change requires iDSI to create an international network for facilitating HTA policy development and HTA organizational development within the countries it supports (see Appendix A3).

Past evaluation work has highlighted the role of iDSI in contributing to HTA policy development in India.Citation29,Citation32,Citation33 One key component of the theory of change of iDSI was to identify policy players in the health care system space. These policy players needed to be engaged with problems that required HTA solutions or who were themselves HTA champions. IDSI supported and empowered them through a process of in-depth knowledge, familiarity with recently developed techniques and methods, sharing worldwide experiences and networking support to build the coalition or community of champions for HTA. The role, process, and value of finding people in order to build a network and a coalition of like-minded individuals with shared vision and interests is the story of iDSI as well as the story of the MTAB and HTAIn’s formation, led by the MOHFW and DHR.

Discussion

This case study of the MTAB and HTAIn examined how a governmental organization for HTA policy development emerged in India.

First, there was facilitation of multiple champions with sufficient seniority and political authority within the government, who were able to use events to raise the visibility of the issue and ensure the topic was a priority for policy makers. These events helped to generate specific political support in the form of decisions that endorsed the need for HTA in key policy documents. Champions also carefully considered organizational placement and formation and were versed in the necessary tools to implement these decisions and form an organization. Thus, leaders with sufficient authority (namely bureaucratic leaders) can use specific tools (such as administrative tools or windows of opportunity) to advance a particular policy—in this case—to create an organization.

Second, a wide group of organizations across the country formed an informal coalition of broad base support, all keen to advance the cause of HTA policy development and organizational placement or formation, all reinforcing a consensus on the shared messages of the need for organizational formation. Notably, many of these organizations also had a role in capacity building across the country.

Third, the development of the necessary capacity within the country, including through national leadership, supported in part by international assistance and manifested in the growing national ecosystem across multiple institutions and stakeholders. Capacity development included creating a network of organizations and individuals with necessary human resources, knowledge, skills, financing and organizational rules for the generation of technical evidence and conducting of HTA studies. Capacity building efforts were strengthened by international networks and organizations with financing, expertise, and policy maker relationships, and this was crucial to help build momentum, international credibility, as well as provide financial resources to achieve short-term wins and build momentum to lead to the creation of the MTAB and HTAIn.

This case study has several limitations. First, the authors of this case study were participants in some of these events as lived experiences. Due to concerns for political sensitivity, stakeholders who were neutral or negative toward HTA creation are not considered in this case study nor were interviews conducted with a broad set of informants beyond the coauthors. However, some of the reasons for resistance to change have been indicated, including a sensitivity to the role of specific international development partners. Finally, the changing power and dynamics between different organizations, including the role of external organizations compared to in-country organizations, as well as the changing roles and power of individuals holding government positions and ranks, were not explicitly examined in this case study.

Nevertheless, as seen in India on other policy issues, there has been a changing dynamic in the ways in which national organizations interact and engage with international organizations. In part with increasing domestic financial resources through the allocation of government budget to the MTAB and HTAIn compared to international resources, increasing academic capital through increased capacity building and training of local talent and workforce rather than reliance on external consultants, and increasing social capital through social networks between Indian HTA policy makers and researchers in India and internationally. The role of international networks may be interpreted as being similar to an international network broker such as iDSI.

The future of the MTAB and HTAIn remains optimistic, but more work remains on its long-term institutionalization. By 2019, the creation of the National Health Authority, the apex body responsible for implementing India’s flagship public health insurance scheme called “Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana,” demanded even more HTA and further shaped HTA development and coordination with MTAB and HTAIn. The story of how a formal network of 18 centers by 2022 was established also merits further research. Thus, this article is limited to the creation of MTAB and HTAIn as one key and initial part of organizational development. The lessons of institutionalization and organizational development beyond creation and emergence represent a future area of research.

Future research about organizational formation of HTA-focused organizations would benefit from a comparative understanding of the organizational placement within government authorities for health and the nature of capacity building that goes into success. Capacity in this understanding is not only the knowledge and skills but also the institutional rules that enable and empower the organization to reach its objectives. The organizational structures and corresponding functions of health authorities across countries vary. This case study contributes to a burgeoning area of research in institutional design and capacity and organizational behavior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Roberts M, Hsiao W, Berman P, Reich M. Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Fulton BD. Health care market concentration trends in the United States: evidence and policy responses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1530–13. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556.

- Xu T, Wu AW, Makary MA. The potential hazards of hospital consolidation: implications for quality, access, and price. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1337–38. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.7492.

- Boin A, Christensen T. The development of public institutions: reconsidering the role of leadership. Adm Soc. 2008;40(3):271–97. doi:10.1177/0095399707313700.

- Boin A, Fahy LA, ‘t Hart P. Guardians of public value: how public organisations become and remain institutions. Boin A, Fahy LA, ‘t Hart P, editors. Springer Nature; 2021. 10.1007/978-3-030-51701-4.

- Douglas S, Schillemans T, ‘t Hart P, Ansell C, Bøgh Andersen L, Flinders M, Head B, Moynihan D, Nabatchi T, O’Flynn J. et al. Rising to Ostrom’s challenge: an invitation to walk on the bright side of public governance and public service. Policy Des Pract. 2021;4(4):441–51. doi:10.1080/25741292.2021.1972517.

- Tendler J. Good government in the tropics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997.

- Howlett M, Ramesh M. Studying public policy: policy cycles and policy subsystems. Toronto; New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Campos PA, Reich MR. Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(3):224–35. doi:10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251.

- Planning Commission, Government of India. Twelfth five year plan (2012–2017): social sectors. New Delhi, India: SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Department-related parliamentary standing committee on health and family welfare sixty-ninth report on demands for grants 2013–14 (demand No.49) of the department of health research (ministry of health and family welfare). Report No.: 69. New Delhi: New Delhi: Parliament of India, Rajya Sabha; 2013. p. 1–44.

- The Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK. Memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the department of health research, ministry of health and family welfare, government of India and the national institute for health and care excellence, UK on a strategic and technical cooperation with regard to evidence-informed healthcare policy and practice; 2013.

- NICE International. Better decisions for better health: priority setting and health technology assessment for universal health coverage in India; 2014.

- National Health Systems Resource Center, New Delhi, World Health Organization Country Office for India. Compendium of health technology assessments: an evidence-based approach to technology-related policy making in health care. World Health Organization; 2014.

- Report on the 2016 conference on priority setting for universal health coverage. Bangkok, Thailand: Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC); 2016. p. 1–181.

- NICE International, International Decision Support Initiative (IDSI). The Current Status of Priority setting and Health Technology Assessment for Universal Health Coverage in India. 2015. p. 1–18.

- Sonawane DB, Karvande SS, Cluzeau FA, Chavan SA, Mistry NF. Appraisal of maternity management and family planning guidelines using the agree II instrument in India. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59(4):264. doi:10.4103/0019-557X.169651.

- Study Visit of Indian Delegation to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2014.

- Minutes of the Joint Steering Committee meeting held as per the MoU between DHR and NICE, UK on 16.12.2015 through Video Conferencing (First Meeting); 2015.

- Government of India Department of Health Research and NICE International. Minutes of the second joint steering committee (DHR-NICE UK) meeting held at 2: 00 pm, March 1, 2016 through video conferencing. Conference Hall. ICMR Hqrs, New Delhi; 2016.

- Jhalani M. Prince Mahidol award conference 2016 “priority setting for universal health coverage”; 2015.

- Srivastava RK. Paper for PMAC 2016 (26–31, January 2015) sub-theme-3 priority setting in action - learning & sharing experience moving towards universal health coverage-indian experience in development of national medical technology assessment board. Vol. PS 2.5. Bangkok, Thailand; 2016.

- Government of India Department of Health Research (DHR), Government of India Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), International Decision Support Initiative (IDSI). Health technology assessment stakeholder’s consultative workshop, 25th July, 2016, India habitat centre, New Delhi, India; 2016.

- HITAP. Report on topic selection workshop in India. New Delhi: The International Decision Support Initiative (iDSI); 2016. p. 1–39.

- Press Information Bureau, Government of India. International workshop on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) inaugurated; government is committed to reducing out of pocket expenses on healthcare: Smt Anupriya Patel; HTA will lead India to have a robust universal health coverage programme: Shri Faggan Singh Kulaste. Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2016 Jul 25.

- Capacity gap analysis questionnaire to inform DHR partnerships.

- IDSI Health Technology Assessment Capacity Questionnaire Cover Note; 2016.

- Concept Note for establishing Medical Technology Assessment Board (MTAB) and institutionalizing HTA in India; 2016.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National health policy. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2017, p. 28. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/documents/policy.

- Gleed G, Kalyanwala S. iDSI country learning review: India. Brighton (UK): ITAD; 2019.

- Dabak SV, Pilasant S, Mehndiratta A, Downey LE, Cluzeau F, Chalkidou K, Luz ACG, Youngkong S, Teerawattananon Y. Budgeting for a billion: applying Health Technology Assessment (HTA) for universal health coverage in India. Health Research Policy And Systems. 2018;16(1):115. doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0378-x.

- Downey LE, Mehndiratta A, Grover A, Gauba V, Sheikh K, Prinja S, Singh R, Cluzeau FA, Dabak S, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Institutionalising health technology assessment: establishing the medical technology assessment board in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000259. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000259.

- NICE International. Report on NICE international’s engagement in India. ITAD; 2015. p. 1–61.

- NICE International, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Mid-term learning review: International Decision Support Initiative (IDSI). Brighton (UK): ITAD; 2016. p. 1–71.

Appendix A1.

Detailed chronology of events of HTA policy development in India

Appendix A2

NICE International: Stakeholder mapping of institutions with capacity for priority setting

Source: 2015 Report by UK NICE International