ABSTRACT

Producing a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is resource intensive, therefore, an explicit process for Topic Identification, Selection, and Prioritization (TISP) can optimize the use of limited resources to those HTA topics of national importance. TISP does not have to be complicated, however, a formalized process facilitates HTA recommendations that better align with local priorities. The comprehensiveness of TISP processes varies according to countries’ needs and to the types of decisions HTA supports. There may be many relevant considerations for TISP, such as the resources available for allocation within the health system, the number of dedicated personnel to complete HTA, and the number of stakeholders and institutions involved in the decision-making process. In countries where HTA-supported decision-making is well-established, the process for TISP is usually formalized. In settings where HTA is emerging, relatively new, or where there may not be the necessary supporting institutional mechanisms, there is limited normative guidance on how to implement TISP. We argue that developing a clear process for TISP is key when institutionalizing HTA. Moreover, insights and experiences from more formalized HTA systems can provide valuable lessons. In this commentary we discuss three institutional aspects that we believe are vital to TISP: 1) Begin topic selection with a clear link to health system feasibility, 2) Ensure legitimacy and impact through transparent TISP processes, and 3) Include the public from the start to embed patient and public engagement throughout HTA.

Introduction

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is an important decision-support aid to achieve universal health coverage.Citation1 HTA promotes a multi-disciplinary process to evaluate the clinical, economic, organizational, social, and ethical issues of implementing health technologies (e.g., health interventions, medicines, medical devices, and more).Citation2 HTA is an explicit health care priority setting tool, which is critical when countries weigh up the best use of finite resources to build resilient health systems.Citation3,Citation4 The HTA process can generically be described in four stages: 1) Topic Identification, Selection and Prioritization (TISP), 2) Analysis, 3) Appraisal, deliberation, and decision making, and 4) Implementation.Citation5 While a wide range of guidance exists for the downstream stages of HTA, an international survey found that HTA bodies are uncertain about the best approach to TISP;Citation6 furthermore, guidance on developing TISP is lacking.Citation7

HTA institutionalization, referring to the process of conducting and using HTA as a normative practice to generate evidence for use in policymaking and resource allocation decisions within a health system,Citation8–10 requires countries to follow institutional mechanisms through the four stages of an HTA (described above). The process of conducting an HTA is financially and time intensive, and the demand for technologies to be evaluated largely exceeds the available capacity to evaluate these technologies.Citation11 Thus, for decision makers in countries with emerging or new HTA systems, or limited capacity to conduct HTAs, deciding on the best topic for an HTA is an important gap in HTA technical assistance efforts. In situations where the demands on the HTA system cover a large range of potential topics, scholars suggest that rapid or adaptive methods can support countries to complete more HTAs.Citation12,Citation13 However, these methods can only help when the topics for HTAs have been decided upon. A recently published study from India found the return on investment of their HTA system depended on robust topic selection and reliable implementation of HTA recommendations.Citation14

There seems to be limited value in doing this supranationally—as the suitability of topics for HTA is defined by a country’s specific needs, priorities, resources, political influences, health system values, and not least, how the health care services are organized. There is no “one-size-fits-all” for how a TISP system should look, nor how it should be institutionalized.Citation7 In the institutionalization of the HTA system, we suggest that more attention should be placed on how topics are identified for HTA and that limited resources should be focused on those HTA topics that are most relevant to a health system. This commentary aims to present that improving the linking of TISP to feasibility, transparency, and public patient engagement can better support appropriate topic identification and institutionalization of HTA processes.

The Global Experience of Organizing TISP

There is limited systematic information about how TISP is organized in countries across the world. The World Health Organization’s Global Survey on HTA and Health Benefit Packages broadly refers to TISP, with few country responses related to the existence of prioritization criteria and evidence base for inclusion or exclusion of health technologies (see questions 6, 11, 12, 13).Citation15 A recent systematic review shed some insight into the process of topic selection frameworks used by some HTA agencies.Citation6 In reporting on the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) members’ approaches to TISP, six generic stepsFootnote1 were identified from specifying the criteria, identifying, shortlisting, scoping, ranking, and deliberation of topics.Citation6 Beyond these steps, the authors suggest that a consensus-based approach for developing methods of topic selection could be valuable for the HTA community.Citation6

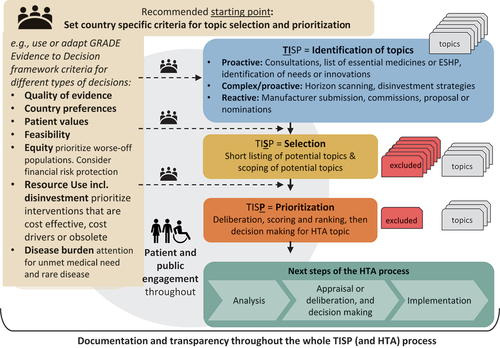

illustrates an approach to TISP. After setting country-specific criteria, these can be used to guide the following components of selection and prioritization. Topic identification can be a “proactive” or “reactive” approach but often ends up as a combination of both. A proactive approach is when part of the HTA system’s mandate or work involves actively searching for topics. A reactive approach is when a pre-defined approach to TISP is lacking and is often in response to a submission of evidence or economic analysis from the pharmaceutical industry.Citation7 A survey that included 21 countries with newly formalized HTA systems found that half of the respondents used a proactive approach and that topics were identified through a formalized topic identification process, while horizon scanning or early warning systems were only present in 25% of responses (n = 5).Citation16 In general, HTA agencies tend to have a more formalized TISP approach to manage reactive responses to requests for pharmaceuticals or manufacturer submissions,Citation17 while for medical devices and public health interventions, formalized TISP processes are less common,Citation18 and less guidance on TISP is available for these health technologies.

Figure 1. Topic identification selection and prioritization process.

The selection process provides information on how identified topics are checked or filtered for conformity with the aims of the HTA system. For example, those conditions or treatments that do not align with the HTA system’s aims or have previously been considered without the discovery of new evidence will be excluded. Prioritization describes the step where a decision is made to either initiate, reject, or postpone the assessment.Citation7,Citation19 Common criteria include disease burden, availability of treatment(s), treatment alternatives, access to treatment, costs (including economic, clinical, or social impacts, potential benefits, etc.), in addition to technical advice from clinical experts or other stakeholders.Citation6,Citation32 Various HTA agencies have developed tools to support the selection and or prioritization of topics, such as the PriTec tool by the Spanish Agencies for HTA Network.Citation19–21 Delphi panels, multi-criteria decision analysis, online ranking tools, and also expert input can support prioritization processes.Citation22–24

In terms of the final decision on the topic, based on our professional experience and identified in the literature, the formal decision-makers are commonly Ministries of Health (or Ministers of Health), National Health Services, National Health Insurance Agencies, or another government department e.g., a Ministry of Research.Citation16,Citation25 In Norway, for example, the Ordering Forum, which includes representation of hospital trusts and central authorities, has the mandate to prioritize HTAs to be conducted following proactive or reactive topic identification.Citation26 Although there may be instances where political engagement may help the HTA system to be more responsive, e.g., political decision makers requesting specific analyses to inform their decisions. In other instances, where the HTA system lacks an institutional framework and process prescribed in government policy or legislation, there is a risk that the decision-making for TISP may be less relevant to the needs of the health care system, and even possibly be vulnerable to pressure or influence from politicians, media, interest groups, or industry,Citation27 which may influence decisions or compromise treatment coverage.

How Better TISP Processes Can Support Better HTA

Topic Selection Must Begin with a Clear Link to Health System Feasibility

The value of an HTA system rests on the ability to implement the outcome recommended in the assessment. This is described by Campos and Reich as a fundamental implementation challenge, where rollout can be delayed because the responsibility for health policy implementation usually rests with a different set of governmental actors than the ones who designed the policy.Citation28 Within the context of HTA, it is often the Ministry of Health, or delegated authority, who holds the responsibility to conduct HTA, where the purchase or delivery of the health technology or service, can be the responsibility of another entity.

The progressive realization of universal health coverage requires countries to define which health services are of the highest priority, for example, by defining an Essential Health Services Package (ESHP). This requires the country to manage trade-offs, whether they should first: a) include more priority services, b) expand coverage of existing priority services, or c) reduce co-payments for existing priority services.Citation29 By establishing clear linkages between the design of the health services package, the conduct of HTA, and the budgetary approval for financing the technology, TISP can be a valuable step to bridge considerations of universal health coverage in health service package design and HTA. It can also offer the opportunity for countries to reduce expenditure through disinvestment of obsolete medicines or technologies. To support HTA topics that are most relevant to the health system, consideration of the feasibility, i.e., the financing and delivery of the technology under consideration in the HTA, should occur at the beginning of every TISP process.

Besides financial feasibility, there may also be challenges related to the feasibility of disinvestment, the feasibility of changing clinical practice, and other aspects of implementation. Topic selection should emphasize the feasibility of implementing the HTA recommendation. The three most common criteria used by INAHTA agencies for TISP are: the burden of disease, clinical or health impact, and economic impact, with no reference to the feasibility of implementation.Citation6 In our professional experiences, working with countries who have emerging HTA systems, the skills to conduct HTA are often given higher priority over determining the best topic for the HTA. A superficial TISP process can contribute to HTA topics being prioritized with insufficient consideration of local needs. South Africa offers an example of an HTA system that clearly prioritizes feasibility in TISP. In the country’s draft HTA method document it states that the: “ … HTA process needs to focus its limited resources on technologies that are available and implementable … and have a reasonable chance of being cost-effective in the South African context.”Citation11 Specifically, the screening criteria refer to feasibility: “ … the technology’s availability in South Africa and the implementability [sic] of the technology in South Africa.”Citation11

A global review identified eight key domains for priority setting methodology used for medicines and medical devices, one of which is feasibility.Citation30 Additionally, the GRADE Evidence to Decision framework’s (EtD) criteria for decision-making in health care systems,Citation31 can guide HTA bodies’ deliberations about feasibility in TISP. GRADE EtD is a decision support tool designed to assist decision makers to transparently make judgments and decisions by prompting the deliberation of whether the problem is a priority. Feasibility, quality of the evidence, how those affected value the outcomes, and resource use are all considered with equal weight when compared to the expected benefits of the technology ().Citation31,Citation33 The value of the HTA rests on its implementation, and therefore a TISP process that explicitly prioritizes both the feasibility of financing and feasibility of delivery should occur at the beginning of any TISP process, supporting effective policy implementation.

Transparent TISP Improves Legitimacy and Impact

Transparency legitimizes the work of an HTA body, enabling a systematic and explicit priority setting process. Transparency facilitates increased stakeholder engagement and is considered to be a pre-condition for a fair decision-making process.Citation34 Disclosure of information assists the public to meaningfully engage in public policy decisions.Citation35 A TISP process that lacks transparency may lead to the selection and prioritization of topics that are inconsistent with the preferences of the society it serves,Citation29 or could potentially contribute to a negative view about the HTA decision. It is widely supported that that inclusive and transparent processes foster legitimacy, supporting social acceptance of decisions.Citation29,Citation35,Citation36

The Slovak Republic is an example of a country with strengths in the transparency of TISP, as the HTA process is grounded on a legal framework with decisions on the recommendation of reimbursement of medicines, procurement, and disinvestment, all publicly available.Citation37 Legislative amendments were suggested in the the Slovak Republic to manage concerns about unsustainable spending and curb the use of a high explicit cost-effectiveness threshold with exceptions for orphan drugs.Citation38 It is now stipulated in law that all technologies with a budget impact over €1.5 million have to undergo an HTA process by the newly formed Slovakian HTA agency.Citation39,Citation40 Centralizing the TISP process has increased transparency in Slovakia, especially for those medicines previously not reimbursed and those under specific patient schemes that were reported to not be cost-effective.Citation38,Citation40 A concern has been raised that linking new TISP criteria to budgetary considerations may result in the agency having to complete more HTAs than they have personnel to complete.Citation27

The role of industry in the TISP process is an ongoing area of controversy that continues to challenge the countries’ efforts to maintain transparency. Countries’ use of industry’s dossier recommendations and cost effectiveness analysis directly to HTACitation17 raises questions about the impartiality of TISP and the underlying rationale for prioritized topics.Citation16 The International Horizon Scanning Initiative (IHSI) was established partly in response to this to better support European IHSI members understanding of upcoming innovations and their influence on currently available products in price negotiations with pharmaceutical manufacturers.Citation41

Include the Public from the Start to Embed Public and Patient Engagement Throughout HTA

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI), or user involvement, are the terms commonly used in reference to stakeholder engagement in HTA processes. The emphasis on the end user as the most important party to include in decision-making can de-emphasize the role that the wider public can also have in health policy decision-making. The aim of public engagement is to include public values and preferences, as well as the experience of patients in decisions related to medicine procurement or treatment coverage.Citation42 PPI in HTA tends to be limited to making submissions about the drugs under the review process. A recent study found that patient and public engagement may be less common in the TISP process, compared to other stages of the HTA, such as the analysis or appraisal phases.Citation16

A challenge of including public perspectives in TISP can be identifying who the “public” are, and the best ways to include their viewpoints in the process. Some interest groups are better organized than others, and rather than true “public” engagement,Citation28 PPI within the health sector can sometimes be described as professionalized advocacy—often by patient representative groups.Citation43,Citation44 This can lead to a limited group of “already active and engaged members” that are not representative of the wider population involved in such processes.Citation44 For TISP, neither the public at large, nor patient interest groups are particularly well represented, as TISP tends to be a process that is limited to decision-makers within the health system.Citation16 This lack of public engagement may stem from TISP requiring prioritization between different disease areas. Decision-makers may also believe that the public lacks the experience or understanding of disease conditions and medications to make informed decisions.

HTA systems should consider how to include service user needs and argumentation at the beginning of TISP—firstly, to help identify HTA topics related to conditions and services that are most relevant to the public as well as society. Mechanisms can be developed to elicit and include public perspectives in addition to traditional PPI. Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage benefits package offers an example of how to do this, with underlying principles of the HTA process to be participatory, as well as systematic, transparent, and evidence-based.Citation8

Conclusion

We suggest three institutional aspects that we believe are vital to TISP: 1) Begin topic selection with a clear link to health system feasibility, 2) Ensure legitimacy and impact through transparent TISP processes, and 3) Include the public from the start to embed patient and public engagement throughout HTA. In this commentary, we argue that the consideration of these factors in the institutionalization of TISP can support the implementation of HTA recommendations. We have highlighted lessons from more established HTA systems that can be drawn in this regard. South Africa offers an example of how to be explicit about linking the policy process to implementation. Transparency, through legal instruments and explicit decision-making processes, is evident in the HTA system of Slovakia. Finally, there is momentum to consider new ways to include the public in TISP. Thailand’s participatory approaches offer some useful lessons for countries looking to enhance the mechanisms to better represent public perspectives in HTA that are also relevant to topic identification. By strengthening TISP, HTA agencies can focus on topics that are of greatest importance to patients, citizens, and the health system. This approach supports fairer HTA decision-making and can have a significant impact on population health.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[1] The six steps 1) Specification of criteria for topic selection, 2) Identification of topics, 3) Short listing of potential topics, 4) Scoping of potential topics, 5) Scoring and ranking of potential topics, and 6) Deliberation and decision making on final topics for HTA.

References

- World Health Organization. A67/33 Health intervention and technology assessment in support of universal health coverage 67th World health assembly. Palais des Natons, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014 May 19–24.

- O’Rourke B, Oortwijn W, Schuller T. The new definition of health technology assessment: a milestone in international collaboration. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(3):1–7. doi:10.1017/S0266462320000215.

- Bertram M, Dhaene G, Tan-Torres Edejer T, Organization WH. Institutionalizing health technology assessment mechanisms: a how to guide. 2021. Report No.: 9240020667.

- World Health Assembly. Health intervention and technology assessment in support of universal health coverage. WHA Resolution. 2014;67/23:3.

- Peacocke EF, Frønsdal K, Heupink L, Chola L, Lauvrak V, Bidonde J. Technical guidance for health technology assessment in low-and middle-income countries. Oslo (Norway): Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2023.

- Qiu Y, Thokala P, Dixon S, Marchand R, Xiao Y. Topic selection process in health technology assessment agencies around the world: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1). doi:10.1017/S0266462321001690.

- Lauvrak V, Bidonde J, Peacocke EF. Topic identification, selection and prioritisation for Health Technology Assessment (HTA). A report to support capacity building for HTA in low and middle income countries. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Division of Health Services GHD; 2021.

- Leelahavarong P, Doungthipsirikul S, Kumluang S, Poonchai A, Kittiratchakool N, Chinnacom D, Suchonwanich N, Tantivess S. Health technology assessment in Thailand: institutionalization and contribution to healthcare decision making: review of literature. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(6):467–73. doi:10.1017/S0266462319000321.

- Mbau R, Vassall A, Gilson L, Barasa E. Factors influencing institutionalization of health technology assessment in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12913-023-09673-4.

- World Health Organization. Institutionalization of health technology assessment: report on a WHO meeting, Bonn 30 June–1 July 2000. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2001.

- Wilkinson T, Wilkinson M, MacQuilkan K. Health technology assessment methods guide (v1.2): to inform the selection of medicines to the South African national essential medicines list. Pretoria (South Africa): South African Ministry of Health; 2021.

- Nemzoff C, Shah HA, Heupink L, Regan L, Ghosh S, Pincombe M, Guzman J, Sweeney S, Ruiz F, Vassall A. et al. Adaptive health technology assessment: a scoping review of methods. Value Health. 2023;26(10):1549–1557. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2023.05.017.

- Heupink LF, Peacocke EF, Sæterdal I, Chola L, Frønsdal K. Considerations for transferability of health technology assessments: a scoping review of tools, methods, and practices. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1):e78. doi:10.1017/S026646232200321X.

- Center for Global Development. Estimating the return on investment of Health Technology Assessment India (HTAIn). CGD; 2023 [accessed 2023 Jun 8]. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/estimating-return-investment-health-technology-assessment-india-htain.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Health technology assessment and health benefit package survey 2020/2021. World Health Organization; 2022 [accessed 2022 Aug 17]. https://www.who.int/teams/health-systems-governance-and-financing/economic-analysis/health-technology-assessment-and-benefit-package-design/survey-homepage.

- Bidonde J, Lauvrak V, Ananthakrishnan A, Kingkaew P, Peacocke EF. Topic identification, selection, and prioritization for health technology assessment in selected countries: a mixed study design. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2024;22(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12962-024-00513-8.

- EUnetHTA. An analysis of HTA and reimbursement procedures in EUnetHTA partner countries. 2017.

- Cyr PR, Jain V, Chalkidou K, Ottersen T, Gopinathan U. Evaluations of public health interventions produced by health technology assessment agencies: a mapping review and analysis by type and evidence content. Health Policy. 2021;125(8):1054–64. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.05.009.

- Lauvrak V, Arentz-Hansen H, Di Bidino R, Erdos J, Garrett Z, Guilhaume C, Migliore A, Scintee SG, Usher C, Willemsen A. Recommendations for horizon scanning, topic identification. In: Selection and prioritisation for European Cooperation on health technology assessment, Norway: EUnetHTA; 2020. WP4 Deliverable 4.10. https://eunethta.eu/services/horizon-scanning/.

- Lema LV, Del Carmen Maceira Rozas M, Prieto Yerro I, Arriola Bolado P, Asúa Batarrita J, Espallargues Carreras M, Armesto SG, López TM, Santamera AS, Serrano-Aguilar Vallés P, the working group PriTec. PriTec tool: adaptation for the selection of technologies to be assessed prior entry into the health care benefits basket.: servizo galego de saude. La Unidad de Asesoramiento Científico-técnico; 2018 [accessed 2023 Oct 13]. https://avalia-t.sergas.gal/Paxinas/web.aspx?tipo=paxtxt&idLista=4&idContido=774&migtab=774&idTax=12028.

- Canadian Agency For Drugs and Technologies in Health. Health technology assessment and optimal use: medical devices; diagnostic tests; medical, surgical, and dental procedures. Canadian Agency For Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2015;1:5.

- Hines P, Yu LH, Guy RH, Brand A, Papaluca-Amati M. Scanning the horizon: a systematic literature review of methodologies. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026764. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026764.

- Packer C, Simpson S, de Almeida RT. EuroScan international network member agencies: their structure, processes, and outputs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31(1–2):78–85. doi:10.1017/S0266462315000100.

- Specchia ML, Favale M, Di Nardo F, Rotundo G, Favaretti C, Ricciardi W, de Waure C. How to choose health technologies to be assessed by HTA? A review of criteria for priority setting. Epidemiol Prev. 2015;39(4 Suppl 1):39–44.

- WHO. Health technology assessment survey 2020/21: main findings. WHO; 2022 [accessed 2023 May 1]. https://www.who.int/data/stories/health-technology-assessment-a-visual-summary.

- Nye Metoder. For suppliers - information in English: Nye metoder [National system of managed introduction of new methods in the specialist health care service in Norway]. 2023 [accessed 2023 Oct 11]. https://nyemetoder.no/om-systemet/for-suppliers-information-in-english.

- Németh B, Csanádi M, Inotai A, Ameyaw D, Kaló Z. Access to high-priced medicines in lower-income countries in the WHO European Region. In: Oslo medicines initiative technical report. Access to Medicines and Health Products (AMP) Team, Division of Country Health Policies and Systems (CPS) Team. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. p. 67. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289058018.

- Campos PA, Reich MR. Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Syst. 2019;5(3):224–35. doi:10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251.

- Baltussen R, Jansen MP, Bijlmakers L, Tromp N, Yamin AE, Norheim OF. Progressive realisation of universal health coverage: what are the required processes and evidence? BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(3):e000342. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000342.

- Frutos Pérez-Surio A, Gimeno-Gracia M, Alcácera López MA, Sagredo Samanes MA, Jario P, Salvador Gómez, Del Puerto MMDT. Systematic review for the development of a pharmaceutical and medical products prioritization framework. J Of Pharm Policy And Pract. 2019;12(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s40545-019-0181-2.

- Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S. et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2016.

- Oortwijn W, Jansen M, Baltussen R. Evidence-informed deliberative processes for health benefit package design–part II: a practical guide. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2021.159.

- Treweek S, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Bossuyt PM, Brandt L, Brożek J, Davoli M, Flottorp S, Harbour R, Hill S. et al. Developing and evaluating communication strategies to support informed decisions and practice based on evidence (DECIDE): protocol and preliminary results. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-6.

- OECD. Trust and public policy: how better governance can help rebuild public trust. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2017.

- Dale E, Peacocke EF, Movik E, Ottersen T, Voorhoeve A, Evans D, Evans DB, Norheim OF, Gopinathan U. Criteria for the procedural fairness of health financing decisions: a scoping review health policy and planning. Health Policy Plan. 2023;38(Suppl 1):i13–35. doi:10.1093/heapol/czad066.

- World Health Organization. Voice, agency, empowerment–handbook on social participation for universal health coverage. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2021.

- Barnieh L, Manns B, Harris A, Blom M, Donaldson C, Klarenbach S, Husereau D, Lorenzetti D, Clement F. A synthesis of drug reimbursement decision-making processes in organisation for economic co-operation and development countries. Value Health. 2014;17(1):98–108. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2013.10.008.

- Tesar T, Obsitnik B, Kaló Z, Kristensen FB. How changes in reimbursement practices influence the financial sustainability of medicine policy: lessons learned from Slovakia. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:664. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.00664.

- National Institute for Value and Technologies in Healthcare (NIHO). Slovakia. How does the system of health technology reimbursement work in Slovakia? NIHO; 2023 [accessed 2023 May 1]. https://niho.sk/en/ako-funguje-system-na-slovensku/.

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Changes to entry conditions for medicines to the Slovak market. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2022 [accessed 2023 June 27]. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/health-systems-monitor/updates/hspm/slovakia-2016/changes-to-entry-conditions-for-medicines-to-the-slovak-market.

- IHSI. IHSI Mission: IHSI. 2023 [accessed 2023 Jun 29 2023]. https://ihsi-health.org/mission/.

- Leopold C, Lu CY, Wagner AK. Integrating public preferences into national reimbursement decisions: a descriptive comparison of approaches in Belgium and New Zealand. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05152-2.

- Abelson J. Patient engagement in health technology assessment: what constitutes ‘meaningful’and how we might get there. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2018. pp. 69–71.

- Bidonde J, Vanstone M, Schwartz L, Abelson J. An institutional ethnographic analysis of public and patient engagement activities at a national health technology assessment agency. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021;37(1):e37. doi:10.1017/S0266462321000088.