ABSTRACT

In 2014, Indonesia’s Ministry of Health established the Indonesian Health Technology Assessment Committee (InaHTAC) to prioritize evidence-based health care technology for inclusion in the national health insurance benefits package. This commentary provides an overview of the current state of the health care technology supply landscape in Indonesia, as well as the impact of HTA studies on priority-setting decisions. Indonesia’s decision-making process for health care technology approval and patient access involves multiple stakeholders and follows several evaluation principles. The licensing, inclusion, and evaluation of health care technology is complex and time consuming, however, requiring input from stakeholders with different roles and interests. Although efforts have been made to establish an HTA ecosystem by, for example, engaging in capacity-building activities and issuing guidelines, challenges remain, including a lack of infrastructure, financial resources, and technical capacity and inadequate stakeholder involvement. Additionally, the current position of the HTA unit, which is connected to the Ministry of Health (MOH), and political pressures from the pharmaceutical industry can result in delayed or ignored HTA recommendations. Therefore, the establishment of an independent and robust HTA body that can inform policy makers about health technology development, licensing, dissemination, and use, along with strong regulations to ensure harmonization and coordination among stakeholders, is necessary. This requires a step-by-step approach to address inadequate overall HTA resources.

Introduction

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) provides valuable evidence useful to decision making that will maximize health and enhance equity.Citation1–3 In light of the global trend toward universal health coverage, public payers worldwide increasingly use HTA to inform resource allocation decisionsCitation4,Citation5 and acknowledge the importance of explicit priority setting and evidence-based decision making.Citation2,Citation6 In 2014, Indonesia began taking steps toward encouragingCitation7 and institutionalizing HTA by establishing an Indonesian HTA Committee (InaHTAC).Citation8

While several publications have discussed the activities and outputs of HTA in Indonesia,Citation9–15 information is lacking about its adoption there to prioritize health interventions and its consequences for their supply chain and the demand for these health interventions. To bridge this gap, this commentary seeks to provide an overview of the evolution of HTA in Indonesia. The goal is not to conduct a new economic evaluation but, rather, to analyze the decision-making process with regard to health technologies in Indonesia by reflecting on the author’s involvement in the development of HTA. This commentary describes the HTA ecosystem, stakeholders, process and recommended methods for conducting assessments and appraisals. It highlights the use of these assessments and appraisals results for setting priorities on health technologies and the subsequent impact of those decisions on revising the national health insurance (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, JKN) benefits package and the demand for these benefits among the insured in Indonesia. Additionally, it identifies challenges posed by current HTA practices, and it suggests future directions to enhance the HTA process and support Indonesians and the wider community in making informed decisions about priorities pertaining to health technologies.

Landscape of Health Technology Supply

Ensuring Access to Essential Medicines, but Unintended Consequences Emerged

The Indonesian government introduced JKN in 2014, which led to the implementation of three policy instruments that have affected the supply of health technologies, especially drugs. These are the List of Essential Medicines (Daftar Obat Esensial Nasional, or DOEN), the National Formulary (Formularium Nasional, or Fornas),Citation16 and the Fornas procurement system.Citation17 Additionally, in 2015, the Ministry of Health (MOH) established an Indonesian HTA Committee (InaHTAC), comprising representatives from MOH, academia, clinical experts, and health economists.Citation7,Citation8

DOEN lists the drugs that are most needed in facilities according to their functions (e.g., prevention, diagnosis, treatment) and the levels of care they correspond to from primary to tertiary healthcare facilities. It is renewed biennially to keep up with the latest developments in science and technology, disease patterns, and programs. Fornas is a list of drugs judged by the National Fornas Committee to be the most efficacious, safe, and cost-effective, based on the latest evidence.Citation18 The National Public Procurement Agency supervises the utilization of electronic procurement or e-Purchasing through the e-Catalog, an electronic auction platform, for the acquisition of Fornas within the JKN program at healthcare facilities. InaHTAC evaluates health technologiesCitation8 and provides recommendations to the MOH regarding their inclusion in the JKN benefits package, issuance with restrictions, or provision with limited services.Citation19

While all of this reflects concrete efforts to ensure the population’s access to essential medicines, unintended consequences have occurred. The implementation of Fornas and the Fornas procurement system had a detrimental effect on the formulary, as it includes less than 15% of the total licensed products available in the country.Citation20 The result was a shortage of essential drugs, adversely affecting JKN patients’ access to the medications they need. To resolve, Fornas has undergone several revisions and seven extensive addendums.Citation21 The Fornas 2015 edition, for example, included 562 efficacious substances in 983 preparations or strengths, while the 2023 edition contains 672 substances in 1,132 preparations or strengths. Although Fornas 2023 represented an increase of 19.6% in efficacious substances and 15.2% in preparations and strengths compared with Fornas 2015, the revisions did not improve the market share of licensed drugs in the 2023 list, since the number of licensed drugs was also continuously increasing during this period.

Interlinked Stakeholders and HTA Principles

Indonesia’s health care technology supply landscape involves a range of stakeholders, including Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan (BPOM), the country’s FDA. The BPOM is responsible for issuing permits and certificates for product distribution and conducting drug and food testing to ensure compliance with legal provisions. The Fornas Committee is tasked with creating the Fornas, which comprises BPOM-approved drugs, while the InaHTAC evaluates whether the Fornas should be included or excluded from the JKN benefits package.

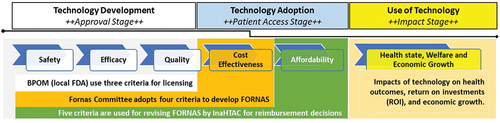

Each stakeholder has a specific responsibility in approving and providing access to health technologies, with different actors involved at each decision-making stage ().Citation22 The BPOM applies safety, efficacy, and quality principles to authorize the use of health technologies, including drugs, while the Fornas Committee assesses drugs based on the BPOM’s three principles and cost effectiveness to determine what will be included in the formulary. Meanwhile, InaHTAC evaluates Fornas based on the four so-called Fornas Criteria and a fifth criterion of affordability.

Figure 1. Existing criteria and actors involved in the priority decisions of health technology in Indonesia.

The health care technology supply chain in Indonesia is notably complex, leading to time-consuming navigation and significant social costs.Citation22 Streamlining the process is urgently needed to improve the system’s efficiency and reduce these costs. It is worth noting that even if a drug has been approved by the BPOM, being included in Fornas drug list by the Fornas Committee requires the pharmaceutical industry to undergo a submission process similar to the initial one for BPOM usage approval. Similarly, for InaHTAC to evaluate both the cost-effectiveness and budget implications of a registered drug listed in Fornas for potential inclusion in the JKN benefits package, it must undergo reevaluation from the licensing phase. This complex and redundant process involves time and cost implications that necessitated significant reform.

HTA Implementation and Impact on Demand

This section provides an overview of the creation of the HTA ecosystem culminating in the Indonesian HTA guideline, highlighting key stakeholders, processes, and crucial methods necessary for HTA implementation. Additionally, it delves into the evaluation of HTA evidence, which informs decision-making to enhance the JKN benefits package, and examines its impact on technology demand.

The HTA Ecosystem

Efforts to create the HTA ecosystem have been undertaken through collaboration with local, international, and development partners,Citation9,Citation23 including HITAP and iDSI, among others. In 2017, InaHTAC issued an Indonesian HTA guideline for researchers and stakeholders to facilitate economic evaluations.Citation19 The guideline describes the role, processes, and methods of HTA.

InaHTAC continued to develop methodologies and compiled them into a revised guideline to address previous limitations.Citation10,Citation24 The revision, which was released in 2022, included the adoption of new approaches, such as multi-criteria decision analysis for topic selection and appraisal, as well as an adaptive HTA for producing and assessment more quickly in the face of limited resources, such as data or time constraints. In addition, the update encourages the development of an HTA infrastructure that utilizes real-world data (RWD) to generate real-world evidence (RWE).

RWE is becoming increasingly important in HTA studies because evidence from randomized controlled trials conducted in other settings, which follow strict protocols, may not reflect real-world healthcare practices in the country. These disparities underscore the need for RWE to capture the true evidence of what occurs in the country. However, the quality of data from existing systems, including those collected from routine healthcare facilities in Indonesia is often inadequate for generating high-quality RWE, resulting in potentially flawed HTA conclusions. Furthermore, various analysis methods are available for generating RWE from RWD, and these must be selected based on sound scientific judgments. While acknowledging RWD and RWE as valid sources of information for HTA studies, InaHTAC recognizes the need for a separate technical guideline that is specific and flexible enough to keep up with scientific developments and requirements in HTA implementation. Such a guideline has not yet been made available, however.

HTA Stakeholders

According to the Indonesian HTA guideline (henceforth the guideline), responsible decision making in HTA requires the involvement of stakeholders in the decision-making process. Unlike expert consultants, HTA stakeholders can provide input without being requested by the InaHTAC. Stakeholders include any person, group, or community with an interest in or involvement with the HTA process, as well as those affected by its results. They may comprise government agencies and public legal entities, such as the MOH, health offices, and the Social Security Administrator for Health (BPJS Kesehatan), as well as medical device and medicine manufacturers, health service providers, practitioners, research institutions, patient organizations, and international agencies.

Diverse entities, such as the MOH, universities, research institutions, and hospitals, act as HTA agents to perform the HTA assessment process, as assigned by the InaHTAC. To qualify as an agent, an institution must demonstrate it has a competent workforce and a history of conducting thorough HTA studies. The assessment process involves a research team comprising experts in pharmacoeconomics, modeling, epidemiology, health economics, and other pertinent disciplines.

The guideline also mentions that stakeholder involvement is a crucial component of the HTA process, encompassing several stages. First, InaHTAC collaborates with numerous organizations to propose HTA topics, spanning drugs, medical devices, and programs, which are then prioritized for study. Stakeholders involved at this stage may include professional organizations, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, various units within the MOH, and BPJS Health. Second, HTA agents and an expert panel conduct the assessment under the supervision of InaHTAC. Third, a panel comprising professional organizations and relevant experts not actively involved in the assessment process is appointed to appraise the findings of the assessment. Finally, InaHTAC produces interim decisions based on the assessment and appraisal results and disseminates to all stakeholders involved. These stakeholders can provide comments and objections to InaHTAC’s interim decisions.

HTA Process

The HTA process comprises six stages: topic selection, assessment, appraisal, policy recommendations, submission, and publication. At the outset, health technology proposals for HTA topics are scrutinized and prioritized based on such criteria as volume, cost, impact on health, policy priorities, cost savings, and public acceptance. The volume criterion pertains to the utilization of health technology, measured either as a percentage of services used in the health insurance program or as a percentage of estimated disease burden.

Collaboration among HTA agents from various institutions, including the MOH, universities, research institutions, and hospitals, is crucial during the assessment stage. The InaHTAC and the expert panel work in tandem to ensure the questions posed are unambiguous and comprehensive. They cover aspects such as the target population, technology or intervention being assessed, the standard of care interventions or usual care interventions in clinical practice as comparators for the proposed technology under assessments, and outcomes.

The main agendas of the appraisal process are twofold; in addition to the appraisal of the assessment results conducted by HTA agents, an appraisal is conducted of other aspects of health technology that are pertinent to answering policy questions but not part of the ongoing assessment process. The assessments are used to make decisions regarding health technologies, including listing, delisting, price negotiations, or restrictions. In formulating these recommendations, InaHTAC adheres to the principles of transparency, accountability, and participation.

The final determination of whether a technology provides value for money hinges on the results of the assessment and appraisal stages. The appraisal results are documented in a recommendation note disseminated to stakeholders. Any objections are entertained for 30 calendar days, and a hearing is organized, if required. The final policy recommendation note is then submitted to the Ministry of Health through an audience and is utilized to determine policy action. Last, the outcomes of the HTA process are published on public platforms to ensure accessibility and promote awareness. A detailed account of the six stages of the Indonesian HTA process is available elsewhere.Citation24

HTA Methods

The guideline provides a thorough framework for assessing the economic viability of different health care interventions. The range of economic evaluation methods available includes cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis, and cost-minimization analysis. Selection of the method hinges on the nature of intervention being evaluated as well as the availability and types of outcome measures. This includes considering the units used to measure outcomes, spanning from natural units or specific clinical endpoints to aspects relating to both the quality and quantity of life gained.

The guideline recommends using the cost-utility analysis method for conducting health technology assessments. The measure of outcomes is Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY), which is evaluated using EQ-5D-5 L instruments from the EuroQol Group with an Indonesian value set.Citation24 The analysis considers the societal perspective, and the target population determines the focus of health care interventions. If required, a subpopulation analysis may also be conducted. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical evidence for health technologies or interventions are included in the assessment. Real-world data should be used as well to describe the local context, and the time horizon should be long enough to cover all relevant aspects. The cost calculations should include direct medical and nonmedical costs and indirect costs from a societal perspective. A discount rate of 3% is applied to both clinical outcomes and costs. If necessary, a decision tree analysis or Markov model can be used. Sensitivity analyses should be conducted using deterministic and probabilistic methods.

The guideline also recommends conducting a budget impact analysis (BIA) alongside the economic evaluation. The BIA provides a robust framework for evaluating the economic feasibility of health care interventions and can be used by policy makers and health care providers to make informed decisions about health technology investments. The BIA should include only direct medical costs for a period of five years and should be calculated from the payer’s perspective. The calculation does not consider discounting.

Also presented in the guideline is a framework for evaluating health technologies using cost-effectiveness thresholds (CETs) that align with the alternative thresholds proposed by the World Health Organization. These CETs range from one to three times Indonesia’s gross domestic product per capita and are intended to determine the cost effectiveness of a health technologyCitation23–26 through a comparison of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of the technology with the GDP per capita. A technology with an ICER of less than or equal to the value of the GDP per capita is considered very cost-effective, while one whose ratio is between one and three times the GDP per capita is considered cost-effective.Citation24

Experts have, however, cautioned against using GDP-based CETs as the sole decision rule,Citation27,Citation28 as they are used in the absence of locally established thresholds and were never intended to determine the CETs.Citation29 They are generally utilized to value health in benefit-cost analyses to advocate for allocation of resources to health instead of other sectors.Citation30 They are not directly related to a country’s health care budget, technical capacity, population preferences, or social values.Citation31 For this reason, the revised 2022 guideline emphasizes that decision making should be based on threshold values calculated specifically for the Indonesian context, recommending the use of such locally established CETs to ensure the cost-effectiveness of health technologies is evaluated accurately and in line with the needs and values of the Indonesian population.

Evidence Appraisal, Decision Making, and Impact

The methods for conducting HTA are typically more established and systematic for drugs than for other technologies. Recent studies have been focused on interventions included in the JKN benefit packages, specifically high cost medications, medical devices, and medical care programs. provides list of all HTA studies conducted from 2015 to 2019. They cover fourteen health interventions, consisting of nine (64.3%) pharmaceutical and five (35.7%) surgical or therapeutic procedures.

Table 1. HTA studies conducted by InaHTAC and HTA Agent* during 2015 to 2019 in Indonesia.

The following examples illustrate how the assessment and appraisal practices of HTA in Indonesia strongly influence policy decisions regarding revisions to the JKN benefits package. These decisions involve incorporating interventions with limitations or excluding interventions into the formulary, thereby influencing their use and costs. Specifically, the recommendations derived from four HTA studies concentrating on targeted therapies, such as bevacizumab, cetuximab, rituximab, and trastuzumab, are detailed. Their consequences on priority setting and demand are assessed in , measured in terms of the utilizations of the interventions assessed (Panel A) and their costs (Panel B).

Table 2. The utilization and costs of selected interventions assessed in HTA studies, 2015–2019.

Bevacizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor, was introduced into metastatic colorectal cancer chemotherapy regimens in Indonesia in 2006.Citation15 However, based on the recommendation of an HTA study and appraisal, the Fornas Committee decided to remove this drug from the formulary, as stated in the Fornas Addendum 2018, and this decision came into effect in 2019. Consequently, the utilization and cost of bevacizumab have decreased significantly since 2019. As shows, for example, the annual average utilization of bevacizumab in 2017 and 2018 was 8,487 tablets, at a cost of IDR 26.8 billion (USD 1.7 million) per year. In 2019, however, both utilization and cost declined by 62.7%, with only 3,163 tablets used and IDR 10 billion (USD 641,923) spent.

The study of cetuximab, a targeted cancer treatment for metastatic bowel cancer and head and neck cancers, suggested excluding it from the formulary since it was found not to provide value for money.Citation12 In response to this recommendation, the Fornas Committee produced the Fornas Addendum 2018, which was enforced the following year. The addendum limited the use of cetuximab, restricting it solely to squamous head and neck cancer indications. Consequently, the use of cetuximab declined by 63.5%, from an average of 3,828 tablets per year in 2017 and 2018 to 1,396 tablets in 2019. The decrease resulted in a notable reduction in annual expenditure, from IDR 8.9 billion (USD 577,072) in 2017 and 2018 to IDR 3.2 billion (USD 209,977) in 2019.

Although rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, was considered a cost-effective for treating patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in combination with chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in Indonesia, its inclusion in the JKN benefits package had significant financial implications.Citation14 InaHTAC agreed to keep it in the JKN benefits package but restricted on its use. Now, the prescription of rituximab must be supported by a complete panel examination test that includes the diagnostic markers CD45, CD20, and CD3. Currently, rituximab is listed in Fornas but restricted to use just in response to a positive CD20 test result, because analysis for CD45 and CD3 can only be conducted by certain laboratories, and the costs of these tests are quite high. Since its implementation in 2020, this restriction has reduced the demand for rituximab. Its annual average utilization of 12,482 tablets in 2017–19 dropped to 4,399 tablets in 2020 (a decrease of 35.2%) and 4,221 tablets in 2021 (a decrease of 33.8%). The average claim cost for rituximab in 2017–19 of IDR 42 billion (USD 2.7 million) per year decreased by IDR 10.8 billion (USD 690,669) in 2020 (25.8%) and IDR 10.1 billion (USD 646,786) in 2021 (24.1%). This brought the total savings for 2020 and 2021 to about IDR 21 billion (USD 1.34 million).

Trastuzumab, a key biologic drug for treating HER2-positive breast cancer, has been included in the Fornas formulary since 2014, despite being quite expensive. The evolving evaluation of trastuzumab by InaHTAC led to rapid responses from the pharmaceutical industry, resulting in the introduction of more affordable biosimilar alternatives alongside the original formulation. Although it was initially excluded in 2018 as per InaHTAC’s suggestion, originator trastuzumab was reinstated in the Fornas formulary in 2020, aligning with the available of the biosimilar version. By 2021, both original and biosimilar variants were priced similarly.

As illustrated in , the utilization dynamics of trastuzumab and its associated costs reveal a multifaceted relationship shaped by regulatory shifts, market fluctuations, and patient needs. The use of the original version of trastuzumab lay dormant from 2017 to 2019 due to its exclusion from the formulary. However, its reinstatement in the formulary in 2020 led to a surge in utilization to 1,292 tablets, followed by a decline to 807 tablets due to price parity with biosimilar alternatives in 2021. These utilization trends mirrored in claim costs, which climbed to 9,086 million IDR (USD 577,833) in 2020, then decreased to 5,675 million IDR (USD 360,922) in 2021. Similarly, the use of biosimilar trastuzumab exhibited fluctuating patterns, starting at 6,464 tablets in 2017, declining to 1,622 in 2020, and then rising to 4,994 in 2021, increasing by 208% from 2020. Claim costs for biosimilar trastuzumab decreased from 37,081 million IDR (USD 2.36 million) in 2017 to 9,305 million IDR (USD 591,773) in 2020, then rose significantly to 28,649 million IDR (USD 1.82 million) in 2021, reflecting the utilization trend.

The utilization patterns of trastuzumab, whether in its original or biosimilar formulations, exemplify the intricate interplay between regulatory decisions and market dynamics. This complex relationship holds significant sway over total JKN spending. The combined utilization of trastuzumab underscores the substantial financial resources required for treating breast cancer. Over five years, expenditures reached a staggering 115.5 billion IDR (USD 7.34 million) for treating JKN patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer alone, with an average yearly expense of 23 billion IDR (USD 1.47 million) from 2017 to 2021.

HTA Challenges and Future Directions

Challenges and Their Consequences

Column 1 in highlights the challenges related to HTA in Indonesia. One main challenge presented during the process is the lack of HTA infrastructure, such as local data on costs, clinical information, and health outcomes. This issue is further compounded by inadequate funding and limited technical capacity, such as a lack of human resources or personnel, to meet the growing demand for HTA. Another challenge is the inadequate involvement of stakeholders in the HTA process, especially during the early stage of implementation. These challenges are common in Asian countries, including Indonesia.Citation32

Table 3. Identified HTA related-challenges, their consequences and future directions.

Additionally, Indonesian policy makers and practitioners are discouraged from using HTA findings for reasons that include the lack of transferability. This encompasses issues related to the relevance, generalizability, and applicability of the underlying evidence and real-world data to provide real-world evidence. This and other factors result in the HTA recommendations that are expected to play a critical role in priority setting often being neglected, delayed in policy actions, or even rejected.

In one case, for example, a policy recommendation made in 2016 to increase the coverage of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)Citation13 for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients was delayed in policy actions until 2019, when it entered the pilot stage in West Java. Even to date, however, the recommendation has not been fully implemented.Citation33 The reasons for this delay are twofold. First, clinicians are less likely to switch ESRD treatment modalities from hemodialysis to CAPD, as the latter modality reduces their income due to decreased patient visits within the DRGs payment, known as Indonesian Case Based Groups, applied in the JKN system. This underscores that while economic evaluations affirm CAPD’s cost-effectiveness, the decision to switch from hemodialysis to CAPD is significantly swayed by the financial incentives offered to clinicians. Second, the supplier of peritoneal dialysis fluid has attempted to negotiate with the MOH to increase the price once this treatment becomes the preferred one, while the supplier holds monopoly power and recognizes that entering the peritoneal dialysis fluid in the market takes time.

Another such case involves an HTA study recommendation to exclude trastuzumab from the formulary for treating JKN patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer The exclusion was approved initially,Citation34 but after cancer patients, clinicians, and industry representatives voiced their opposition during a parliamentary meeting, the recommendation was rejected and now remains on the list.Citation23,Citation35

These two examples could be attributed to the current HTA agency’s lack of autonomy. The agency connected to the MOH has limited authority and does not have a direct mandate to utilize the recommendations of HTA as explicitly stated by the law. Currently, its role is limited to providing policy recommendations to the MOH.Citation19,Citation24 This situation creates an opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry to influence the approval of their products in the country. Drug manufacturers have, for instance, requested clinicians to question the HTA studies and have organized cancer patients to speak up during parliamentary meetings. Public media have also been used to spread inaccurate information regarding health technology already assessed.

Future Directions

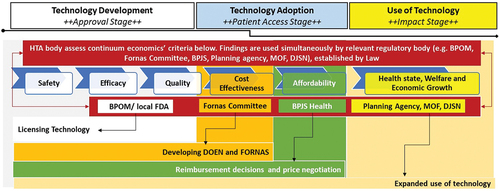

To address these challenges and protect public health from unsafe, ineffective, or unnecessary technology, Indonesia needs a robust and independent HTA body that can provide policy makers with information on the development, licensing, dissemination, and use of health technologies. The proposed body, a new idea that needs to be tested, would bridge research activities, evidence production, and decision making by different stakeholders at the approval, patient access, and impact stages of HTA (). Placing it at the border between research and policy formulation would also allow for more informed, transparent, and legitimate decisions, enabling stronger societal participation. For the body to function effectively, strong regulations are needed to ensure harmony and coordination among stakeholders.

Figure 2. Proposed HTA Body to provide evidence adopted by actors for priority decisions in Indonesia.

The use of HTA findings to incorporate health technologies into policy determinations, such as licensing for market approval, deciding whether to include them in the formulary with or without restrictions or exclude them from the formulary, and price negotiations, will depend on the political and institutional framework of the HTA body.Citation36 The body should, therefore, have a direct regulatory role established by law, with clear links defined between HTA recommendations and decision making. The regulations should explicitly outline how the recommendations generated by the body are to be utilized in shaping policy decisions. Additionally, stakeholders outside the producing body can utilize these recommendations to address the complexities of the current health technology supply chain, as depicted in . For instance, these recommendations can inform licensing considerations by BPOM, inclusion in Fornas by the Fornas Committee, and price negotiations efforts by BPJS Health. This explicit legislation could facilitate the acceptance and adoption of HTAs into policy decisions.

Finally, the scope of HTA studies should expand beyond solely generating evidence for technologies within the JKN benefits package, which typically encompass curative treatments. It should also encompass public health measures for disease prevention and innovative health technologies. While existing HTA experiences can be optimized to expand the studies, inadequate resources (in terms, for example, of personnel, financial support, organizational structure, infrastructures, networking, and decision mechanisms) need to be addressed gradually. To overcome barriers to HTA adoption due to lack of personnel in the country, Indonesia should continue to focus on capacity-building activities, academic research, and the production of public goods. The government should ensure full financing for HTA activities by allocating sufficient funding from its budget or providing the majority of its funding. The organizational structure should be a standalone, independent agency connected to the health care system. The HTA infrastructure should be developed, especially the role of local data, which translates to the extended use of local patient registries linked to payers’ databases. To minimize duplication of HTA-themed studies, international collaboration should be strengthened and integrated into the national HTA implementation. Finally, Indonesia needs to set fixed CETs for the country’s context to increase the policy-decision mechanism.

Conclusion

This commentary delves into the health care technology supply landscape in Indonesia, with a particular focus on the implementation of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and its impact on priority-setting decisions and the demand for health technology in the country. Additionally, this article explores the challenges that current HTA practices face and provides recommendations to enhance the process, which can aid health care professionals in making well-informed decisions about priority setting.

In light of the high demand for health interventions and resources but limited funding for health policy makers in Indonesia, this analysis holds great significance. It contributes to the existing literature on the subject and presents valuable insights to health policy makers and practitioners in Indonesia and other low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, this analysis is expected to inspire further research and reform on this topic, ultimately leading to improved decision-making processes regarding health technologies in Indonesia and other countries with similar contexts.

Acknowledgments

This commentary was funded by the NIHR 133252: Global Health Research Unit: Health financing for UHC in challenging times: leaving no-one behind using UK international development funding from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed are of the author and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government. The guest editors of this special issue reported funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1202541).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Using health technology assessment for universal health coverage and reimbursement systems. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2015 Nov 2 [accessed 2024 Apr 1]. hta_november_meeting_report_final.pdf(who.int).

- Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Marten R, Vega J, Teerawattananon Y, Tritasavit N, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Seiter A, Kieny MP, Hofman K, et al. Priority-setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 June 1;94(6):462–10. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.155721.

- Chalkidou K, Li R, Culyer AJ, Glassman A, Hofman KJ, Teerawattananon Y. Health technology assessment: global advocacy and local realities comment on “priority setting for universal health coverage: we need evidence-informed deliberative processes, not just more evidence on cost-effectiveness. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017 Apr 1;6(4):233–36. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.118.

- Teerawattananon Y, Painter C, Dabak S, Ottersen T, Gopinathan U, Chola L, Chalkidou K, Culyer AJ. Avoiding health technology assessment: a global survey of reasons for not using health technology assessment in decision making. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021 Sep 22;19(1):62. doi:10.1186/s12962-021-00308-1.

- MacQuilkan K, Baker P, Downey L, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, Prinja S, Zhao K, Wilkinson T, Glassman A, Hofman K. Strengthening health technology assessment systems in the global south: a comparative analysis of the HTA journeys of China, India and South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1527556. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1527556.

- Pitt C, Vassall A, Teerawattananon Y, Griffiths UK, Guinness L, Walker D, Foster N, Hanson K. Foreword: health economic evaluations in low- and middle-income countries: methodological issues and challenges for priority setting. Health Economics. 2016 Feb;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):1–5. doi:10.1002/hec.3319.

- Peraturan Presiden No. 12/2013 junto No. 82/2018 tentang Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional. Jakarta, 2013 and 2018.

- Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan No.171/Menkes/SK/IV/2014 junto No. 01.07/MENKES 6192/2020 tentang Komite Penilaian Teknologi Kesehatan (KPTK). Jakarta, 2014 and 2020.

- Sharma M, Teerawattananon Y, Luz A, Li R, Rattanavipapong W, Dabak S. Institutionalizing evidence-informed priority setting for universal health coverage: lessons from Indonesia. Inquiry. 2020 Jan;57:46958020924920. doi:10.1177/0046958020924920.

- Chavarina KK, Faradiba D, Sari EN, Wang Y, Teerawattananon Y. Health economic evaluations for Indonesia: a systematic review assessing evidence quality and adherence to the Indonesian Health Technology Assessment (HTA) guideline. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023 Mar 31;13:100184. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100184.

- Chavarina KK, Faradiba D, Teerawattananon Y. Navigating HTA implementation: a review of Indonesia’s revised HTA guideline. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023 Sep 11;17:100280. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100280.

- Putri S, Saldi SRF, Khoe LC, Setiawan E, Megraini A, Santatiwongchai B, Nugraha RR, Permanasari VY, Nadjib M, Sastroasmoro S, et al. Cetuximab as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): a model-based economic evaluation in Indonesia setting. BMC Cancer. 2023 Aug 8;23(1):731. doi:10.1186/s12885-023-11253-y.

- Putri S, Nugraha RR, Pujiyanti E, Thabrany H, Hasnur H, Istanti ND, Evasari D, Afiatin. Supporting dialysis policy for end stage renal disease (ESRD) in Indonesia: an updated cost-effectiveness model. BMC Res Notes. 2022 Dec 6;15(1):359. doi:10.1186/s13104-022-06252-4.

- Putri S, Setiawan E, Saldi SRF, Khoe LC, Sari ER, Megraini A, Nadjib M, Sastroasmoro S, Armansyah A. Adding rituximab to chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients in Indonesia: a cost utility and budget impact analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Apr 25;22(1):553. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07956-w.

- Kristin E, Endarti D, Khoe LC, Taroeno-Hariadi KW, Trijayanti C, Armansyah A, Sastroasmoro S. Economic evaluation of adding bevacizumab to chemotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC) Patients in Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021 June 1;22(6):1921–26. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.6.1921.

- Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan No. HK.02.02/MENKES/523/2015 tentang formularium nasional. Jakarta; 2015.

- Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan No. 63/2014 tentang Pengadaan Obat Berdasarkan Katalog Elektronik (e-Catalogue). Jakarta; 2014 Sep.

- Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan No. HK.02.02/MENKES/524/2015 junto HK.02.02/MENKES/636/2016 tentang Formularium Nasional. Jakarta, 2015 and 2016. PERATURAN (kemkes.go.id).

- Indonesia Health Technology Assessment Committee (InaHTAC). Health Technology Assessment (HTA) guideline. Jakarta: Ministry of Health; 2017.

- Kajian kebijakan pengadaan obat untuk program Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional 2014-2018. TNP2K. 2020.

- Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan 2197/2023 tentang Formularium Nasional. Jakarta; 2023.

- Situational analysis of health technology as the first step to develop HTA roadmap in Indonesia. Depok: CHEPS UI, MOH and WHO; 2021.

- Health Technology Assessment Indonesia: Annual review 2022. Pusat Kebijakan Pembiayaan dan Desentralisasi Kesehatan, Badan Kebijakan Pembangunan Kesehatan, Kementerian Kesehatan. Jakarta; 2022.

- Suryawati S, Nadjib M, Hidayat B, Syam FA, Purwantyastuti A, Kristin E, Thobari At J, Syarkati A, Fortuna HP, Siti ML, et al. General guideline for health technology assessment in Indonesia.Wiweko B, Suryawati S, editors. Jakarta: Health Policy Agency Publishing Company (BKPK Publishing Company); 2022. p. 74.

- World Health Organization Commission on Macroeconomics and Health: Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development (who.Int). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001 [accessed 2024 May 6].

- Hutubessy R, Chisholm D, Edejer T. Generalized cost-effectiveness analysis for national-level priority-setting in the health sector. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2003 Dec 19. 1(1):8. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-1-8.

- Leech AA, Kim DD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Use and misuse of cost-effectiveness analysis thresholds in low- and middle-income countries: trends in cost-per-DALY studies. Value In Health. 2018 Jul;21(7):759–61. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.016.

- Bertram MY, Lauer JA, De Joncheere K, Edejer T, Hutubessy R, Kieny MP, Hill SR. Cost-effectiveness thresholds: pros and cons. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Dec 1;94(12):925–30. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.164418.

- Chi YL, Blecher M, Chalkidou K, Culyer A, Claxton K, Edoka I, Glassman A, Kreif N, Jones I, Mirelman AJ, et al. What next after GDP-based cost-effectiveness thresholds? Gates Open Res. 2020 Nov 30;4:176. doi:10.12688/gatesopenres.13201.1.

- Robinson LA, Hammitt JK, Chang AY, Resch S. Understanding and improving the one- and three-times GDP per capita cost-effectiveness thresholds. Health Policy Planning. 2017 Feb;32(1):141–45. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw096.

- Marseille E, Larson B, Kazi DS, Kahn JG, Rosen S. Thresholds for the cost-effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches. Bull World Health Organ. 2015 Feb 1;93(2):118–24. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.138206.

- Teerawattananon Y, Teo YY, Dabak S, Rattanavipapong W, Isaranuwatchai W, Wee HL, Luo N, Morton A. Tackling the 3 big challenges confronting health technology assessment development in Asia: a commentary. Value Health Reg Issues. 2020 May;21:66–68. doi:10.1016/j.vhri.2019.07.001.

- Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan RI No. HK.01.07/MENKES/274/2018 tentang Uji Coba Tata Laksana Penyakit Ginjal Tahap Akhir dalam Rangka Peningkatan Cakupan Pelayanan CAPD.

- Alasan BPJS Kesehatan Hapus Obat Kanker Trastuzumab. CNN Indonesia. 2018 [accessed 2024 Apr 2]. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20180717102756-78-314718/alasan-bpjs-kesehatan-hapus-obat-kanker-trastuzumab.

- Trastuzumab Masuk dalam Daftar Obat Kanker pada Fornas 2024. Media Indonesia 2024. accessed 2024 Apr 2]. https://mediaindonesia.com/humaniora/659574/trastuzumab-masuk-dalam-daftar-obat-kanker-pada-fornas-2024.

- Novaes HM, Soárez PC. Health technology assessment (HTA) organizations: dimensions of the institutional and political framework. Cad Saude Publica. 2016 Nov 3;32Suppl 2(Suppl 2):e00022315. English, Portuguese. doi:10.1590/0102-311X00022315.