?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper introduces the special edition on International Inequality. It contextualizes the papers against the background of the “new inequality literature”. This contains two broad strands: critics of the International Financial Institutions who focus on inequality between nations and those like Piketty who focus on with inequality within nations. These concerns have wider consequences, notably for scholars of the “Great Divergence” between the global South and North that followed the advent of capitalism; it is also theoretically damaging for neoclassical economics, whose standard models of Growth and Trade predict that the world market should reverse this Divergence. It identifies a number of lacunae in this literature. First, the literature does not address the relation between the two sources of inequality, though it is clear that the former has significant effects on the latter. Second, the literature does little to address the causes of inequality in general, confining itself to amassing a volume of empirical data. The contributions in this volume are dedicated to making good these absences. The introduction concludes with an analysis of the roots of the theoretical difficulties involved and calls for a concerted scholarly effort to construct superior alternatives.

The new inequality literature and the multipolar world

Inequality, in the early years of the second millennium, has acquired an iconic status, receiving the level of public attention once accorded to unemployment, growth, and inflation. Piketty’s (Citation2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the best-known contemporary manifestation, was preceded by a copious stream of criticism (Stiglitz Citation2002, Citation2017) of the policies of the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and others collectively known as the “International Financial Institutions” (IFIs).

We will refer to the resulting body of work as the “new inequality literature”. This special issue of Japanese Political Economy aims to promote discussion by situating this work in a wider theoretical, historical and geopolitical context.

The literature revives concerns with inequality that date from the origins of capitalism. In their modern form, they surfaced in controversies provoked by the impact of so-called “globalization” on world poverty and human development, and more widely on political and social stability.

Dramatic changes in the world economy, beginning in the 1980s, provoked two strands of writing. One, presaged by the Brandt Commission Report (Brandt Citation1980) popularized the terms “global North” and “global South”, the former mainly comprising the heartland nations in which capitalism was first established and accounting for about a fifth of the world’s population, the latter comprising the rest.Footnote1 At that time, the North’s average income was 11 times greater than that of the South, already twice as large as in 1950. Within six years, this gap doubled.

Discussion on the consequences was ignited by a landmark paper from Pritchett (Citation1997) entitled Divergence, Big Time. Supported by a wealth of empirical evidence, Pritchett frontally challenged the received view that the South was “converging” with the North as capitalism spread to the latecomers. Reinert (Citation2004), Wade (Citation2018), Hickel (Citation2018), King (Citation2019), Freeman (Citation2019b) and others then contributed a mass of evidence that Convergence was not taking place.

This strand is most concerned with differences between nations. The second strand, best known for Piketty’s findings that a “super-rich” class has risen in tandem with an especially poor “under-class”, concerns differences within nations. This too was presaged by earlier work. Wilkinson and Pickett (Citation2010) Spirit Level showed that inequality is correlated with a wide range of welfare indicators ranging from life expectancy to crime rates. Milanovic (Citation2005, Citation2016) and the “Povcal” team at the World Bank offer the third position. They argue that under so-called globalization, within-nation differences are of no consequence, so we need only study inequality across the world as a whole. The resulting concept of “household inequality” treats the whole world as if it were a single nation—a view strongly criticized by Desai (Citation2013).

Historical origins of the modern inequality debate Stiglitz (Citation2002) was one of the earliest officially recognized writers to acknowledge that poverty and inequality had both increased substantially under the neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatization, and free capital flows known as the Washington Consensus.

These policies, and their effect on the global South, originated in the 1979 “Volcker shock” (Desai and Hudson Citation2021) when the USA sharply raised interest rates on dollar loans, at one point as high as 20 percent. Ostensibly designed to rein in inflation, this was provoked by the burgeoning US trade debt and the persistent outflow of dollars from the USA, a trend which has opened early in the postwar years became especially severe following Nixon’s 1971 abandonment of dollar convertibility and the 1974 Great Slump (Mandel Citation1976).

Many Southern countries had amassed large debts in the ambitious expansion programs of the preceding “Development Decades”, on the naïve assumption that the USA would simply accommodate their needs for finance at the low rates which then prevailed. They now found themselves facing unsustainable debt burdens. The IFIs, as suppliers of dollar loans, were positioned to supply the resultant pressing need for credit but used this lever to impose “conditionalities” for debt relief, compelling sovereign governments to re-organize their economies in line with the extra-territorial requirements of the supplier of their trading currency. This policy shift was accompanied by a parallel theoretical shift which Todaro (Citation1995) dubs the “neoclassical counterrevolution”, now widely described as “neoliberalism”.

The concern with international inequality was far from new, figuring in Marxist and Liberal criticisms of the “New Imperialism” from 1890 on, persisting in the postwar development literature (Prebisch Citation1950; Singer Citation1950; Kuznets Citation1955; Reinert and Jomo Citation2005), and hotly followed by the Dependency school (Gunder Frank Citation1966; Amin Citation1979, Citation2010). Whilst most early Developmentalists optimistically assumed the world economy would converge over some undefined historical period, their ranks divided between those who said socialist measures would be needed to bring it about, and those, following Rostow’s (Citation1960) Stages of Economic Growth (subtitled a “Non-Communist Manifesto”) claimed this would happen naturally under capitalism.

The new literature responded to the disturbing fact that convergence was not taking place. Pritchett showed that the gap between the richest and poorest nations systematically grew throughout the 20th Century, implying that Divergence was not a response to the neoliberal shock but an established historical trend, in which the neoliberal years were a mere episode. These concerns intersected with new debates among economic historians on “The Great Divergence”, a phrase attributed to Huntington ([Citation1996] 2011) and popularized by Pomeranz (Citation2000), to describe the gap in living standards which emerged during the Industrial Revolution between the core nations of Europe and those of the rest of the world.

The issue of within-nation inequality was likewise not new, being for example the main concern of the interwar welfare state literature (Tawney [Citation1931] Citation1983). In the aftermath of World War II, it became widely accepted that the state should cater for human and social needs that capitalism failed to address, especially in Europe, whose capitalists accepted the US view that welfarism was (in their countries) a necessary if temporary concession to stave off Communism.

The new literature responded to the shock of losing these welfarist protections. Neoliberal policies thus operated on two fronts: their principal effect was a successful assault on the postwar gains of the developmentalist global South, but they became better known in the global North for their effects on the working and popular classes in the heartlands. As the state retreated, many indicators of social wellbeing retreated with them, including public health, elderly care, homelessness, vulnerability, access to justice, and, of course, freedom from poverty.

The field then divided: inequality between nations was addressed by IFI critics, whilst Piketty and others addressed that within nations. In fact the two are indissolubly connected; the division has hence impoverished the theory.

Implications for theory

The new literature not only raised a range of new issues of economic and policy theory narrowly defined but engaged the rest of the social sciences, especially the disciplines of sociology, political science, history and geography, over which the debate on convergence cast a particularly ominous shadow. In keeping with Rostow, many writers supposed that Divergence arose from delays in acquiring a fully capitalist internal economic system or “late development”. Economic laws would, over time, obliterate this problem nation by nation. Yet, the evidence strongly suggested, this was not happening.

This shadow became yet darker when it fell on the foundations of neoclassical economics, because of the centrality within it its theories of Growth and Trade. The neoclassical counterrevolution, based on these foundations, predicted that the world market would equalize wages and profit rates as shown by Samuelson’s (Citation1948) famous theorem, supported by the Heckscher-Ohlin trade theory (Heckscher Citation1991) which became the neoclassical standard.

Yet more disturbingly, both theories rested on the paradigm of General Equilibrium which had come to dominate economics, including in its Marxist variants, in the postwar era (Freeman Citation2007, Freeman, Chick, and Kayatekin Citation2014). The bedrock on which the mainstream rests was, in summary, increasingly called into question by the facts.

The resulting discordance provoked Endogenous Growth theory (Romer Citation1994), a significant revision of neoclassical growth theory, whilst stronger dissenting voices came from the Dependency School (Gunder Frank Citation1966) and from protagonists of Uneven and Combined Development (Mandel Citation1976; Desai Citation2013), who rejected the neoclassical framework altogether.

This was not a purely abstract discussion about theoretical foundations; it had profound practical policy consequences, as Stiglitz noted in 2002, and again in 2017. Inequality called into question the Washington consensus, structural adjustment, deregulation, market liberalization, and shock therapy. Opposition to these policies crystallized not just among intellectual élites but on the streets, unleashing IMF riots, Jubilee 2000 and the “occupy Wall Street” movement, and provoking state-level changes with profound consequences for the “New World Order” which the USA triumphantly but prematurely announced following the USSR’s collapse: a striving among poor countries for economic independence, the Latin American Pink Tide, Putin’s rise, the BRICS, and not least China’s decisive commitment to an independent, state-led and avowedly socialist economic path.

As it became clear that China’s success owed as much to its departure from the Washington Consensus as to “Globalization”, two issues came to the fore: was China, through some hitherto-untried combination of state-led and market-based policies, breaking out of the subordinate status accorded the global South in the Great Divergence? And was its meteoric rise purchased at the expense of internal inequalities, or did it lay the basis for their future elimination?

These controversies go well beyond minor disputes on the margins of economics, to the heart of the question “how far can we trust the market?”

How do the relations between nations affect inequality within them?

The new literature as noted straddles two inquiries—but this is not all. Citizens of any nation are concerned about their relationship to other persons. However, their governments are also concerned about their relations with other nations. These are of course not the same thing; however, an obvious question arises: what is the relation between the two?

Such a relationship is certainly to be expected. The capitalist world remains divided between a small group of well-off former colonial powers, a large mass of their substantially poorer former colonies or semi-colonies, the former socialist countries, and China.

This produces profound pressures at both ends of the social and class spectrum. It generates, among the élites of the South, the aspiration to emulate the living standards of the North. But Northern countries are some twenty times better off than the South, placing an enormous distance between these élites and their fellow citizens, leading to the permanent structural instability expressed, for example, in Bolsonaro’s controversial interregnum.

Conversely, a large world pool of cheap labor exerts downward pressure on the wages of the North, polarizing the Northern labor force. There are many other potential mechanisms of transmission between ‘international’ and ‘national’ inequality. These, however, are not explored in the new inequality literature.

The literature thus divides neatly into two narratives, neither of which addresses the above key question. The Piketty team in essence study only differences within-nations. They pay almost no attention to differences between nations, except insofar as to compare, for example, inequality in the USA with inequality in Africa. But this sheds no light on whether the relation between the USA and Africa has anything to do with inequality within either of them. The reduction of all forms of inequality to differences between ‘individuals’ became especially prominent under the impact of the ‘Globalization’ mania of the neoliberal years (Desai Citation2013).

Thus Milanovic (Citation2005) promotes “household inequality” in no uncertain terms as superior to conventional concepts of international inequality. He presents three possible measures of it: “concept 1” calculates a conventional indicator, such as the Gini or Theil index, of the dispersion of GDP per capita between nations. “Concept 2” applies population weights to GDP per capita, correcting an important potential distortion.

Milanovic then, however, takes a third step. In his “concept 3” measure. differences between nations disappear altogether, and we compare only differences between the households that live in them:

Concept 2 [population-weighted international inequality] is perhaps the least interesting … its main advantage is that it approximates well Concept 3 inequality [incorporating household inequality] … once Concept 3 is available, however, Concept 2 inequality will be (as the saying goes) history. (Milanovic Citation2005, 10).

Relations between nations are expunged. The issue of North-South relations, which rightly preoccupied the theorists of the fifties and sixties, are in the Piketty account left aside and in the household inequality approach, ruled out of court.

The effects of China’s rise are likewise accorded no recognizable status. To illustrate, consider and , taken from the data page of the Piketty team’s World Inequality Database (WID).Footnote2 summarizes the evolution of the share in national income of the bottom 50% of the population of a country, generally taken as a good indicator of within-nation inequality.

Table 1. Share in national income of bottom 50% of the population.

Table 2. National Income per adult, US$.

If we pay no attention to between-nation differences, the worst performers are the Russian Federation, China and South Africa, for which this indicator has fallen by 41%, 43% and 56% respectively.

But then we encounter a puzzle. The share of the lowest 50% of the World has risen by a stellar 66 percent. Yet this share has fallen in all major countries except Turkey, Nigeria, Mexico and Spain, whose combined population is less than 6% of the world. Moreover, the worldwide share has risen by more than three times the largest improvement in within-nation share. Within-nation improvements cannot possibly explain the worldwide improvement.

How can this be? As shows, the share of China’s bottom 50% in China’s national income has fallen somewhat, but their share in world national income has dramatically improved. China’s national income has grown by a factor of over six. In consequence, the income of China’s bottom 50%, relative to the world’s income, is at least three times bigger.

The share of these 700,000,000 humans in world income has, in short, almost certainly trebled. By this measure, inequality has significantly fallen as a result of China’s national growth. But Milanovic terms this a “concept 2” change—a “between-nation” difference. Dismissing this as a historical relic wipes out the most significant improvement in history in the income of one of the largest groups of the poorest people in the world.

And if like the Piketty team, we pay no attention to inter-nation differences, we report figures that we simply cannot explain.

Whatever happened to dependency?

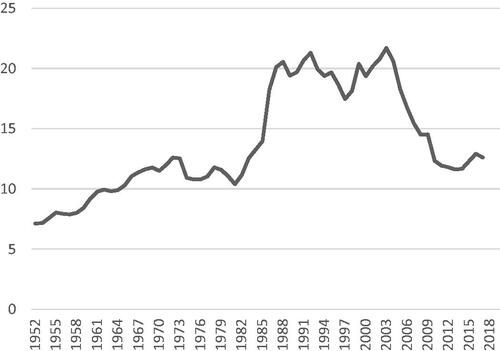

This lacuna in the new inequality literature has claimed a second theoretical victim: the original concept of a fundamental North–South antagonism ().

A simple chart illustrates the point, using an easily understood measure of between-nation inequality due to Kuznets (Citation1966). We measure the GDP per capita,Footnote3 loosely called average income, of two geopolitical blocs of nations: the global North and South. We then divide the North’s GDP per capita by the South’s to produce the “Monetary Inequality Index” (MII). This (Freeman Citation2019b) closely tracks the “Concept 2” Gini and Theil indices, so this result is not a statistical artifact.

Two points now emerge. First, the average nation of the South is now twice as badly off, compared to its Northern counterpart, as in 1950. In 2000 the MII attained a zenith three times worse than in 1950. It then fell for a decade, but this reversal bottomed out in 2012 at a worse level than in 1980, and all recent evidence (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh Citation2021) points—except for China and Vietnam—to a renewed widening of international differences.

The second point is the scale of the difference, rarely appreciated. By 2001, the average citizen of the South was 22 times worse off than her Northern counterpart. This difference is vastly greater than that within nations.

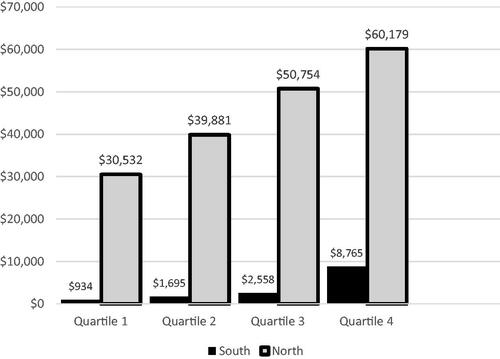

illustrates this point. It shows GDP per capita for each quartile of the South and the North in 2016. The average GDP of the wealthiest 25% in the South, at $8,765, was just over a quarter of the poorest quartile of the North at $30,352. Within-nation inequality does not mitigate the sheer scale of this difference: the average income of the poorest quintile in the USA,Footnote4 at $12,937, is 30% greater than the average GDP of the richest quintile of the South at $9,860.

Figure 1. The Monetary Inequality Index (MII): GDP per capita of the North divided by that of the South. Data source for all figures: World Bank, Geopolitical Economy (Citation2021) calculations.

What causes inequality?

A singular feature of the new literature is the puzzling lack of causal explanations for inequality, which Lee and Siddique (Citation2021) in this volume address.

There is no shortage of empirical data on inequality and indeed, this is one reason for the popularity of the work, which extends far beyond the narrow circle of cognoscenti who follow the obscure debates of the economists. Those who scan this cornucopia of numbers for policy fruit are, unfortunately, deprived of a critical piece of knowledge: why is this happening? As we analysts constantly repeat to our clients, data are not to be confused with information.

Of course, general scapegoats are not hard to find: it is “caused by globalization”, or perhaps capitalism, or neoliberalism. But, especially if we want policy remedies, we need theories—comprehensive explanations of phenomena, unearthing sufficient causal links to take appropriate action. The first step is to trace particular causal mechanisms. Lee and Siddique explore the important relationship between financialization, a major empirical feature of the modern evolution of the international economy, and inequality. As they note:

Financialization is likely to increase inequality in several ways. It could aggravate inefficient rent-seeking in the financial sector, and this generates excessive profit in the financial institutions and very high income for already wealthy financiers (Kaplan and Rauth, 2010; Philippon and Reshef, 2012; Zhang, 2017). It is reported that much of the increased inequality in the U.S. economy is associated with the growth in rent-seeking, partially associated with financialization (Stiglitz, 2015; 2016). Since the 1980s, many countries experienced lower growth and industrial investment and the rising power of finance and short-termism at the expense of workers. Financialization could raise income inequality by depressing investment and employment.

Financialization is one possible explanation for a feature of the recent evolution of the “industrialized” economies of the global North which contradicts the so-called “Kuznets curve” hypothesis. Kuznets (Citation1955) hypothesized that as an economy develops, economic inequality will first rise and then fall, producing an inverted U-shaped chart of inequality against income level.

In brief, Kuznets supposed that in the early stages of development, those who already hold wealth can increase it because there are many new investment opportunities, whilst urbanization holds down wages. However, once a certain level of average income is reached (on the important assumption that industrialized societies tend to democratize and evolve welfare states), increases in per-capita income begin to decrease economic inequality.

Kuznets’ reasoning concerned not the time-independent relation between income levels and inequality but their evolution over time. However, the Kuznets curve hypothesis is often cited in support of the controversial “trickle-down” claim that raising the income of the wealthy invariably raises the income of the entire nation.

Financialization clearly could act as a counter to the effects which Kuznets expected of a mature economy, because it provides an opportunity to accumulate wealth which, being essentially a form of rent, is not limited by the expansion of productive capacity. Using panel analysis, Lee and Siddique modify the Kuznets curve equation for a large sample of industrialized economies with terms to account for “financial rent”, market concentration and other indicators of financialization, showing that they significantly modify the inequality-income relationship.

What does the state do? Industrialization, welfare, and inequality

We already noted that many early scholars of the relationship between inequality and development assumed, understandably in the immediate postwar years, a kind of linear progression in the social care that society would undertake as it grew wealthier. The “Kuznets curve” thus rests on the assumption that mature industrial societies almost automatically develop at least a social safety net, and evolve toward the comprehensive welfarism that characterized both Britain’s post-Beveridge welfare state and the German Sozialstaat which evolved, with American consent, in the Adenauer years and beyond. Indeed, state-managed social welfare reached an apogee in the “Scandinavian models” of socialism, leading even to predictions of some kind of “social convergence” between capitalist and non-capitalist societies.

The state also played a critical role in the rapid growth of the “latecomer advanced economies”—South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, though scant few more—in a succession of “miracles” emerging as the postwar years unfolded (Page Citation1993, see also Krugman Citation1994; Bird and Milne Citation1999). But what, actually, is exceptional about the economic and social achievements of the so-called “advanced” industrial nations?

The Allied occupiers allowed, and even encouraged, the state to play a much more central role in the reconstruction of Germany and Japan than they found acceptable in their own countries. They had learned the lesson of Versailles: faced with the choice between the bogeys of capitalist statism and ungovernable revolutionary chaos, they opted unerringly for the lesser of the two capitalist evils.

Yet this choice was political, not economic. In the wake of the “Second Slump” of 1974 (Mandel Citation1976), the inflationary crises of the 1970s and the inexorable decline of dollar domination (Desai and Hudson Citation2021), the Reagan-Thatcher coalition opted for the withdrawal of the state from both the economy and society and the neoliberal era began.

This sudden onset of a new economic policy paradigm, accompanied by an ideological anti-state and anti-Soviet offensive of unprecedented and unanticipated scope, rudely dashed the prevailing progressivist Weltanschauung of a general evolution toward a benevolent welfarist or developmentalist capitalism as an automatic consequence of economic progress. Anti-Keynesian, supply-side economics sounded the retreat from the evolutionary path which the earlier developmental economists (including Rostow himself, despite his anti-communism) took for granted.

Missing was an understanding of the extent of contingency that affects state involvement in a capitalist economy. The state is, in technical terms, we discuss later, exogenous to the economy. Its role in any given capitalist country, whether in development or welfare, is a product of class struggle, not automatic economic mechanisms. Where the capitalists were weaker or under threat—from their own workers, from other capitalist nations, or from Russia or China—the state played a correspondingly greater role, but once the capitalists felt confident of their political strength, they did not hesitate to revert to Victorian laissez-faire ideologies and practices.

In particular, the state’s social role has no automatic connection with its economic role. We do not at all mean there is no desirable connection: the very idea of a “developed” society which cannot take care of its people is oxymoronic. The point is that capitalism does not compel capitalists to behave either morally or rationally: its political order is fundamentally irrational. Inequality, COVID, and the burgeoning ecological emergency, are just the most visible expressions of this disjuncture.

A major consequence is the “varieties of capitalism” of the nations of the global North. The most emphatically neoliberal is, of course, the USA, though outside observers often fail to recognize the diversity and creativity of combative responses—often heroically so—to be found in this vast, sprawling, failure of a nation. Neither Martin Luther King, nor Malcolm X, nor George Floyd, nor the countless indigenous peoples who perished resisting the occupier of their lands, died in vain.

Almost every combination of state social and economic involvement barring Communism itself can be found within the Northern Nations if one delves deep enough in their history. The pluripolarity of these responses (to borrow a phrase from Hugo Chavez) provides, therefore, a rich laboratory for the social scientist.

Pascal Petit (Citation2021) in this volume enters this laboratory, scrutinizing the Piketty team’s empirical material through the lens of the geographical and historical influences on specific types of the state within the global North. “[V]arious statistical and analytical studies,” he writes,

have been carried out since 2011 on the initiative of Thomas Piketty and his colleagues in Paris and Berkeley, providing an impressive statistical picture of income inequality for more than 80 countries over a period from 1980 to 2016…

Nevertheless, these symptoms are difficult to interpret, as their impact on democracy or more precisely on the way society is made varies according to the time and the country. This does not mean that they are a kind of white noise, these signs manifest something, most often a deterioration, but in order to appreciate their lasting or reversible character and their extent, one is tempted to confront them each time with the prevailing political situations and the ideologies which structure them.

Petit analyses two sources of variation to be found in eleven industrial states which include the USA, a number of European states, Japan, and South Korea. He combines this geographical analysis with a historical study of the impact of the ‘exogenous shocks’ that have impacted the evolution and responses of their states.

Class: Inequality between whom and whom?

A further characteristic of the new literature is its recourse to purely Weberian income categories, which are quite different from both Marxian categories and the categories that appear in the national accounts. For Marx (Freeman Citation2019a) the determining characteristic of the evolution of the income of society’s various component parts is society’s property relations.

As Hashimoto (Citation2021) in this volume notes:

To analyze the current state of Japanese society in relation to class structure, it is necessary to establish a scheme of class structure and to develop procedures for operationalizing the concept of class and measuring the class locations of the respondents. In essence, this study is adopting an appropriate combination of several schemes of class structure and methods of empirical research that have been proposed in the 1970s and 1980s. Such methods were formulated from the perspective of structuralist and analytical Marxism.

The means to conduct a class-based analysis are fully available to scholars in the shape of the national accounts. For example, a driving force of inequality is the simple relation between employers and employees, recognized in the national accounts as sources of ‘factor income’. Though they do differ from Marx (and Ricardo) they nevertheless retain a structural relation to Marx which differentiates them from Weberian categories.

Capitalists and the owners of rented property are however treated, following Adam Smith, as producers of wealth. For Marx (Freeman Citation2019a) and his precursors the Ricardian socialists, the workers are the sole source of new value, whilst rent and profits are deductions from it. Nevertheless, because the national accounts provide at one and the same time a measure of income and a measure of expenditure, workers’ income is clearly presented.

Thus, a simple and revealing measure of inequality is the share of employment income in the social product, compared with profits, rent, and interest income. Such “property-based” measures of inequality are absent from the new literature, though they were a primary concern of the early welfare state literature of Tawney, Titmus, Beveridge and their counterparts in other countries.

Hashimoto undertakes a detailed property-based analysis of the structure of the income of the non-capitalist classes of Japan, in an attempt to account for the growth of what, in the mainstream literature, is referred to as the “underclass.” “The working class is considered the lower and largest exploited class in a capitalist society,” he writes.

However, regular workers, who constitute the majority of the working class, have been ensured relatively stable employment, especially in the manufacturing industry. In contrast, the rapidly increasing non-regular workers have precarious employment, and their wages are much lower than those of regular workers. In addition, as we will see later, it is difficult for them to marry and form a family, and they are constituting a group that is different from the traditional working class. For this reason, in this study, I will refer to non-regular workers, excluding married women, as the "underclass" and regard them as a different grouping from the regular working class, even though they are included in the working class in a broad sense.

Hashimoto develops a “five-class structure” to account for the distribution of income and class structure of modern Japan, which he divides into the Capitalist class, the “new middle class”, the Regular Working class, the Old Middle Class, and the underclass.

The underclass, he argues

is fundamentally different from other classes in terms of its extremely low income, vulnerability to the risk of poverty, difficulties in marriage and family formation, and large differences from other classes in consciousness and living conditions. Therefore, from the perspective of whether or not it is possible to maintain the general standard of living, the class structure of contemporary Japan can be regarded as being divided into underclass and other classes.

Given the attention that modern inequality literature devotes to the “underclass” this class-based approach is a salutary antidote.

Labour and international inequality

The issue of class, as should be expected, leads directly to the question: what role does labor play in explaining international inequality? This constitutes another lacuna in the new literature.

In an earlier paper on international trade, Yoshihara and Kaneko (Citation2016) explain some of the fundamental divisions in the theoretical treatment of inequality:

Understanding why some countries in the world economy are so rich while some are so poor is one of the most important issues in economics, as there are large inequalities in income per capita and output per worker across countries, increasing since 1820. Regarding this issue, the so-called dependence school recognizes the emergence of development and underdevelopment in the capitalistic world system as a product of exploitative relations between rich and poor nations. For instance, among others, Emmanuel (1972) discusses the generation of unequal exchange (UE) between rich and poor nations due to the core-periphery structure of international economies. He argued that, in the world economy characterized by customary disparity in wage rates among developed and undeveloped nations, the international trade of commodities and capital mobility across nations cause the transfer of surplus labor from poor nations with lower capital-labor ratios to wealthy nations with higher capital-labor ratios, which results in the impoverishment of poor nations and the enrichment of wealthy ones.

Yoshihara and Kaneko draw attention to what is arguably the greatest lacuna in the inequality literature, not to say neoclassical theory, namely that differences in wage levels are the greatest single statistical explanator of differences in income. The US minimum wage is $7.25 an hour. This is a floor, often overridden by city and state ordinances—the Washington, D.C. minimum is $13.69 per hour at the time of writing whilst activists have rallied around the “fight for the fifteen”. Contrast this with India, where Unni (Citation2005) estimates that the “predicted daily wage” [my emphasis — AF] of Indian workers ranges from Rs. 375.36 for “regular” urban male workers and Rs. 30.36 for rural female workers—$10 and $0.75 respectively. The vast majority of Indian workers could thus expect to earn less in a day—in the worst case ten times less—than the lowest-paid American worker in an hour.

The biggest prerequisite to correcting the gross inequities in international income is obviously, therefore, to raise the wage level of the average Indian worker to the level of the average American worker. Of course, this would require a substantial rise in the productivity of Indian labor. But given that China has multiplied the income level of its population by six on average, in a little under forty years, is this such an impractical suggestion? Were Indian income merely to grow at the Chinese rate of the past forty years, it would reach Korean levels by 2030 and American levels by 2040. Is that really so impractical?

Yet on productivity levels, the new inequality literature is also silent. The developmental discourse of the postwar years, when elevating productive capacity sat side by side with the eliminating inequalities of consumption, has virtually disappeared. This leads us to the greatest inequality gap of all: why is the productivity of labor so different, between one country and another? A variety of responses are to hand, all from outside the inequality literature.

In this respect, the comment of Yoshihara and Kaneko (op. cit.) is apposite. They note the objections to the theory of Unequal Exchange from within orthodox economics, as a result of which that theory is entirely absent from modern discussions:

Samuelson (Citation1976) argues that Emmanuel’s theory of UE is inconsistent with the theory of comparative advantage, which implies the existence of mutual gain from trade.

Samuelson failed to comment, however, on an important difference between Ricardo’s formulation of Comparative Advantage and its adaptation into neoclassical trade theory. Ricardo stated his theory in terms of the labor required to produce the output of each country. But Haberler (Citation1930) objected on the following grounds:

The theory of comparative costs was developed on the basis of the labor theory of value, and all theorists who accepted it have indeed assumed that it rests also logically on the labor theory of value. For the authors who reject the labor theory of value, the theory of comparative costs founders on the cliffs as the former, that is, on the fact that there simply exist no units of real cost, neither in the shape of days of labor nor in any other shape…

He then restated the theory as a factor allocation problem. This was a double switch: in place of goods – wine and cloth—countries now traded factors of production–capital and labor. And labor was no longer the source of value; capital not only contributed to value but functioned as a substitute.

A point critical to unequal exchange was thus is ignored: capital goods are produced by means of labor. Wine and cloth are not substitutes, nor can cloth be produced from wine, nor wine from cloth. Neoclassical theory thereby arrived at the notion, not deducible from Ricardo’s original theory, that to produce in the “most efficient” way a low-wage country should substitute labor for capital domestically and acquire capital goods abroad.

But a poor country has a third option: development. By dedicating at least part of its labor force to acquire and apply technical knowledge to raise the productivity of its capital goods sector, a country can change the quantity of labor it needs to produce more capital goods – exactly as the Dependency theorists proposed and as China, to the chagrin of Presidents Trump and Biden alike, has actually done.

A very simple statistic illustrates the point: what is the actual traded price of the product of one hour of labor, in each country of the world? In terms that Marx would have understood, why does forty hours of Indian labor exchange on the world market for one hour of American labor? In particular, why do the countries of the global South require much more labor to produce capital goods than commodities and raw materials? Not because their “Comparative Advantage” lies indefinitely in producing basics and labor-intensive products, but because the market deprives them of the ability to develop a competitive capital goods sector. Their lower productivity yields a value transfer—Marx’s “surplus profit” to advanced producers located in the North—with which they use to maintain a permanent monopoly of high technology.

The role of labor in production is thus a fundamental issue in understanding inequality between nations. Yoshihara (Citation2021) in this volume returns to the issues raised in Yoshihara and Kaneko (op. cit.) and other papers on international trade. “Recently”, he states,

a vast literature has analyzed the persistent, and widening, inequalities in income and wealth observed in the vast majority of nations, while some data show inequality in per-capita income between the richer developed countries and the poorer developing ones which has been expanding since 1820. Thus, the issue of the long-run distributional feature of wealth and income in the capitalist economy should be at the heart of economic analysis, as Piketty (Citation2014) emphasizes, and one of the central questions in economics should be to ask what the primary mechanism to generate such disparity persistently between the rich and the poor is.

However, he deals with the question at a more fundamental level: can a labor-value system serve as the basis for the analysis of international trade?

According to the standard Marxian view, the system of labor values of individual commodities can serve as the center of gravity for long-term price fluctuations in the pre-capitalist economy with simple commodity production, where no exploitative social relation emerges, while in the modern capitalist economy, the labor value system is replaced by the prices of production associated with an equal positive rate of profits as the center of gravity, in which exploitative relation between the capitalist and the working classes is a generic and persistent feature of economic inequality.

This view has been criticized because problems arise under ‘joint production’ in which a single capital is used to produce a multiplicity of outputs:

Some of the literature such as Morishima (1973, 1974) criticized this view by showing that the labor values of individual commodities are no longer well-defined if the capitalist economy has joint production.

Yoshihara responds to these criticisms:

Given these arguments, this paper firstly shows that the system of individual labor values can be still well-defined in the capitalist economy with joint production whenever the set of available production techniques is all-productive.

Secondly this paper shows that it is generally impossible to verify that the labor-value pricing serves as the center of gravity for price fluctuations in pre-capitalist economies characterized by the full development of simple commodity-production

This article thus underpins, theoretically, the conclusions reached in Yoshihara’s other works, by arguing that the method used there is not vulnerable to Morishima’s criticisms.

Shock, trend and the validity of theory

Public attention has been focused on the policy implications of inequality. It would be remiss, however, to conclude without reflecting on their implications for theory. These are not as remote from the policy as may be thought. For, if the facts stand in contradiction with the theories on which a policy is based, what grounds exist for consenting to that policy? Simply put, the conflict between the predictions of orthodox macroeconomics and the observed facts is so severe and has remained unaddressed for so long, that the economic theories which inform Northern policies can no longer be considered to rest on a scientific foundation.

This is not merely a failure of science but of democracy, uniformly recognized as founded on the informed consent of the governed. If policies are imposed based on theories inconsonant with the facts, then consent is not informed, because the theory does not justify the claim that the policies will produce the promised results. The question then posed is this: what exactly leads us to conclude that an economic theory conflicts with the facts? And how may we address the defects in the theory, and rectify the problems arising, thus addressing the adverse and harmful consequences of the theory?

The basic issue is a simple scientific matter. If the predictions of a theory conflict with the facts, which assumptions or methods lead to this conflict, what needs to be changed to open the way to theories from which the conflict is absent?

The method of science, which we characterize (Freeman Citation2020) as ‘inductive pluralism’, is quite simple: if a theory conflicts with the facts (as interpreted by the theory) we must first identify any assumptions or methods such that, if they are dropped, the conflict does not arise. Next, we must identify alternative assumptions that lead to predictions consonant with the facts.

The greatest inductive challenges facing modern economics arise from trends—notably historical trends. This is because economists suppose that though, observations may deviate from what a theory predicts, this does not conflict with the theory if the fluctuations remain within limits that can be plausibly explained as arising from chance.

We set aside, initially, the complex problem of distinguishing between chance and imperfect knowledge, to which both Marx and Keynes paid careful attention. We are concerned with the following inductive issue: accepting for the sake of argument the lax view that any deviation of observation from prediction may legitimately be attributed to chance, at what point does a conflict between theory and prediction oblige us to call the theory into question?

It is here that the timespan of any trend becomes paramount. It is one thing to maintain that owing to unforeseen circumstances, Convergence has been postponed for the time being. It is quite another to maintain it has been postponed indefinitely: this is just an underhand way of saying the theory does not apply. A law which never manifests itself is not a law but a doctrine. If we conclude, from the evidence, that as Pritchett suggests there is a long-term historical trend for the North to diverge from the South, or even (a more limited finding) that there is no long-term trend for them to converge, then since the theories of growth and trade predict the opposite, they are false. And to the extent that neoclassical macroeconomics relies on them, it too is false.

Historical reasoning is hence vital. At certain points, inequality between nations has risen. At others—not many, any impartial observer must concede—it has declined. Generally speaking, it has risen throughout capitalist history, above all if we abandon the fiction of a continuous spectrum of national conditions and recognize the empirically confirmed distinction between the global North and South.

But it has not grown monotonically. It fell somewhat in the 1970s, and sharply from 2002 to 2012. May we still speak of a trend?

Two points are relevant. First, the 2002–2012 correction to the exceptionally high levels of the neoliberal decades did not bring international inequality back to its 1980 level. And second, this correction, mainly caused by a steep temporary rise in commodity prices, ended in 2012, when inequality resumed its upward trend.

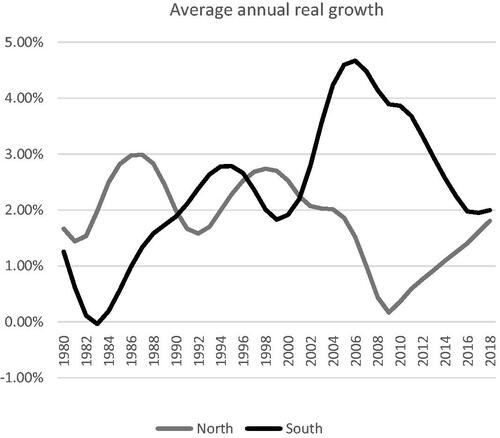

A 2012 paper by Kemal Derviş, World Bank Vice-President for Poverty Reduction and Economic Management in 2000, and briefly in 2001 Turkey’s Finance Minister, illustrates the point. Entitled ‘Convergence, Interdependence, and Divergence’, it proclaimed “a new convergence”, boldly forecasting 4.5% growth in the global South, compared to 2.5% in the North. No such forecast was justified, as shows.

The 2002–2012 reversal calls for caution in supposing a permanent trend in Divergence but is in no wise a proof of Convergence. The historical evidence is completely incompatible with Derviş’s claim. During only two decades since the dawn of capitalism has anything resembling Convergence taken place; each ended with inequality at a higher level than before its beginning; and Divergence in both cases resumed immediately after.

But this evidence decisively rules out accepting either the neoclassical theory of Growth or its theory of Trade, as valid explanations of reality.

What constitutes a valid alternative theory?

The above finding does not supply an alternative theory. Where should we look? Let us begin with a possible hypothesis: that divergence is caused by factors external to the market. The acceleration of international inequality in the 1980s owed much to conscious actions by actors that neoclassical theory treats as “exogenous”. Could we conclude that by disrupting economics’ notorious “ceteris paribus” clause, neoliberal policies—not the spontaneous functioning of the market—produced most of the divergence?

Though plausible, this explanation does not let neoclassical theory off the hook. The above measures claimed to restore the “free working” of a market disrupted by welfarist and developmentalist interventions. Indeed, the neoliberal years have arguably gifted economic science with the nearest to a laboratory-pure free market that the world is likely to experience. That Divergence reached world-historic highs in this period hardly confirms theories which predict that under these very conditions, the opposite should happen.

Another way to explain long-run disparities is by “endogenizing” variables previously considered exogenous such as human capital, innovation, and government policy, as in the “endogenous growth” theories associated with Romer. Their explanatory power is greater than standard theory, for sure. But there is a problem: if our endogenous variables include non-market variables like government policy, we are no longer testing whether the market produces Convergence or Divergence but whether it does so in combination with appropriate government action.

This shift in focus is of course welcome since we can study honestly and impartially study whether the optimum combination of government and market actions is to be found in India, China or the USA. It does not, however, explain the primary error in the theorems and prognostications which predict that a pure market system will produce Convergence.

In constructing an alternative, it is always essential to ask “an alternative to what?” Which particular assumption of any given theory is responsible for its predictive failure? This leads us to a distinction which most economic theories make but rarely scrutinize logically, between endogenous and exogenous factors.

A standard-issue economic theory assumes certain magnitudes to be given or known, externally to the theory itself. These “exogenous” magnitudes include consumer utility functions; the technological conditions of production and hence the Aggregate Production Function of neoclassical macro or the input-output relations of Linear Production Systems; and not least, the mysterious Solow residual.

In contrast, quantities of goods produced or consumed, and their prices, are “endogenous”, by which economists mean that their magnitudes can be calculated once the exogenous variables are known. This gives rise to the standard-issue “problem” of high economic theory: taking the exogenous variables as given over some set of points in time, determine the values of the endogenous variables over the same set. This is the “prediction” of the theory.

Mathematically, denote the k variables of the system by a vector Since these variables are changing over time, let us also add a time subscript, writing

In general, at any one time depends on its values at previous points in time. We can write this either as a differential equation in discrete time (Goldberg Citation1986), or a differential equation in continuous time.Footnote5 Engineers and natural scientists generally use continuous time, but economists, who have not deviated from period analysis since Sismondi introduced it early in the 19th Century, habitually use discrete-time.Footnote6 The most general relation is then

(1)

(1)

where f is a function encapsulating the theory. This states that Y at time t depends on whatever Y was at all previous points in time, and on time itself.

Two common simplifications, presupposed by almost all economic theories, don’t affect the argument but make it clearer: the system is “autonomous”, which means time doesn’t enter explicitly; and there are no lags, so Y depends only on what it one period earlier. This yields

(2)

(2)

It is easy to show, as in undergraduate mathematics textbooks (e.g. Grimshaw Citation1990, 65) that such an equation always has a unique solution given the ‘initial conditions’ which specify Y at some arbitrary starting point.

The General Equilibrium paradigm that now dominates all economics makes an adaptation which constitutes a special case of (2). Y is partitioned into two groups; n endogenous variables and m exogenous variables by

n + m = k. EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) then becomes the slightly more complicated

(3)

(3)

The exogenous A is supposed to be determined independently of the endogenous X. The technology, the accelerator, propensity to consume, psychological preferences, government spending, central bank interest rate—everything the economist considers fixed in some sense “external to the market” are “known” or “given” and treated as independent variables. This is the mathematical meaning of the term “exogenous”.

There are then two possible ways to think about solving (2). The most general, the temporal or non-equilibrium solution, is the standard solution given by Grimshaw. This solution yields, for any A, a determinate and unique X. This method also figures in schoolbook solutions to the multiplier-accelerator model, in Harrodian growth dynamics, and so on. It is generally adopted by the post-Keynesians (Chick Citation1983) and scholars of the Temporal Single System Interpretation (TSSI) of Marx (Kliman Citation2007; Freeman and Carchedi Citation1996). We designate this

(4)

(4)

Since this gives X at all points in time we can drop the time superscript, giving

(4a)

(4a)

X here figures, technically, as a functional, mapping f, for any given A, to a corresponding X. In plain language, for any set of exogenous variables specified throughout time, (4a) tells us what the endogenous variables will be throughout the same time.

The General Equilibrium approach, also still adopted by many Marxists, expresses the problem in this way: suppose X does not change between t–1 and t, that is

(5)

(5)

There is then a unique solution, under the conditions expressed in the Brouwer fixed-point theorem (Sobolev Citation2001) for in terms of

This gives the different solution

(6)

(6)

In general, the type (4) solution X does not coincide with the type (6) solution X*. This provides an adequate means to test, empirically, which of the two solutions best explain the facts, for any particular set of phenomena. In some cases, X may be an attractor for X*; in others, it is not.

Trends are especially relevant to any empirical test of whether this is the case, since if there is any tendency for X and X* to diverge from each other, generally speaking, the longer the time interval considered, the more evident this tendency will be.

In at least one case—persistent long declines in the profit rate observed during capitalist history—X explains the observed historical trend (Freeman Citation2000, Citation2019c) whilst X* does not: as Okishio (Citation1961) proves, X* predicts a rising historical trend. As Okishio (Citation2001) himself notes, this is because his theorem assumes equilibrium: it is a type (6) solution.

Should we expect an analogous difference in explaining the long-run trend of rising international inequality? This is, as yet, an open question. However, since neoclassical theory rests on an equilibrium approach, we should expect it to predict decreasing inequality: if prices or technology in one location differ from those in another, the system cannot be in equilibrium. There are thus strong a priori grounds for supposing that the error lies in the equilibrium method.

As noted, of course, if non-market factors are made endogenous, it may be possible to explain this trend by other means. But then we no longer address the pure neoclassical theory which informs current policy, namely that independently of exogenous constraints, the world market will produce Convergence. In consequence, we may fail to identify the sources of error in this theory.

We, therefore, suggest a hypothesis for further research:

The endogenous divergence hypothesis:

if the only endogenous factors are the market variables of prices realized and quantities produced and consumed, the persistent observed long rising trend in inequality may be explained by a temporal solution.

under these conditions, no equilibrium solution will explain this trend.

This is a hypothesis, not a proven fact: to prove or disprove it, proponents of temporal and equilibrium approaches will have to exhibit theoretical predictions conforming to the observed long-term trends. It is, however, the most critical hypothesis to test if we wish to take seriously the central claim made by Marx himself: that the origin of capitalism’s difficulties is the capitalist system itself, and that therefore, these difficulties may only be finally overcome by replacing that system by something superior.

Notes

1 All measures of income refer to GDP per capita in current US dollars at market exchange rates. The Brandt Report global North included the USSR, Yugoslavia and the Warsaw Pact countries, and China in the global South. Here, these countries are treated as distinct blocs from both the South and the North.

2 https://wid.world/data/. (Alvaredo et al. Citation2018)

3 measured in current US dollars at market exchange rates. Technically, as Piketty notes, income is not identical to GDP. However (Freeman Citation2019b) , the difference is small compared to that between nations; I use the most widely available data.

4 The World Bank supplies quintiles of income for individual nations. Quartiles for the North and South are calculated using population-weighted GDP per capita for every nation in a bloc, to ensure no nation is omitted.

5 Grimshaw (Citation1990), a classic work, illustrates using the accelerator-multiplier model, on page 5. Here the multiplier, the accelerator, and Government spending are exogenous whilst consumption and investment are endogenous.

6 Freeman (Citation2020) shows that if price and value are additive (the price of two baskets of goods is equal to the price of the combined basket) and exchange consistent (the money paid by the purchasers of any good is equal to the money received by the sellers), any arbitrary discrete time system may be expressed in continuous time.

References

- Alvaredo, F., L. Chancel, T. Piketty, E. Saez, and G. Zucman. 2018. “World Inequality Report.” World Inequality Lab 2018.

- Amin, S. 1979. Imperialism and Unequal Development. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Amin, S. 2010. The Law of Worldwide Value. 2nd ed. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Bird, G., and A. Milne. 1999. “Miracle to Meltdown: A Pathology of the East Asian Financial Crisis.” Third World Quarterly, 20 (2):421–437. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599913839.

- Brandt, W. 1980. North-South: A Programme for Survival: Report of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues. London: Pan.

- Chandrasekhar, C. P., and J. Ghosh. 2021. ‘Is Emerging Asia in Retreat?’ Real World Economic Review. https://rwer.wordpress.com/2021/07/13/is-emerging-asia-in-retreat/?utm_source=pocket_mylist

- Chick, V. 1983. Macroeconomics after Keynes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Desai, R. 2013. Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire. London: Pluto Press.

- Desai, R., and M. Hudson. 2021. “Beyond the Dollar Creditocracy: A Geopolitical Economy.” Valdai Discussion Club Paper 116. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://valdaiclub.com/files/34879/

- Freeman, A. 2000. “Marxian Debates on the Falling Rate of Profit – A Primer.”ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/2588.html

- Freeman, A. 2007. “Heavens above: What Equilibrium Means for Economics.” In Equilibrium in Economics: Scope and Limits, edited by V. Mosini. London: Routledge.

- Freeman, A. 2019a. “Class.” In The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx, edited by M. Vidal, Tomas Rotta, Tony Smith, and Paul Prew. Oxford: OUP.

- Freeman, A. 2019b. Divergence, Bigger Time: The Unexplained Persistence, Growth, and Scale of Postwar International Inequality. Manitoba: GERG.

- Freeman, A. 2019c. The Sixty-Year Downward Trend of Economic Growth in the Industrialised Countries of the World. Manitoba: GERG.

- Freeman, A. 2020. “A General Theory of Value and Money (Part 1: Foundations of an Axiomatic Theory).” World Review of Political Economy 28–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.11.1.0028.

- Freeman, A., and G. Carchedi, eds. 1996. Marx and Non-Equilibrium Economics. Aldershot and London: Edward Elgar.

- Freeman, A., V. Chick, and S. Kayatekin. 2014. “Whig History and the Reinterpretation of Economic History.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 38 (3):519–529. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beu017.

- Geopolitical Economy Data Laboratory. 2021. https://github.com/axfreeman/MacroEconomic-History-Server-Builder/tree/master/DATA/EXPORT/2020%20Updates

- Goldberg, S. 1986. Introduction to Difference Equations, with Illustrative Examples from Economics, Psychology and Sociology. New York: Dover.

- Grimshaw, R. 1990. Nonlinear Ordinary Differential Equations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gunder Frank, A. 1966. The Development of Underdevelopment. Somerville, MA: New England Free Press.

- Haberler, G. 1930. “Die Theorie der komparativen Kosten und ihre Auswertung für die Begründung des Freihandels.” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv. 32 (1930):349–370. [Translated and reprinted in Anthony Y. C. Koo, ed. Selected Essays of Gottfried Haberler. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hashimoto, Kenji. 2021. “Transformation of the Class Structure in Contemporary Japan.” The Japanese Political Economy doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/2329194X.2021.1943685.

- Heckscher, E. F. 1991. “The Effects of Foreign Trade on the Distribution of Income.” In Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory, edited by Harry Flam and June Flanders, p. 38. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hickel, J. 2018. The Divide: Global Inequality from Conquest to Free Markets. New York and London: W. W. Norton.

- Huntington, S. P. [1996]. 2011. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- King, S. 2019. “Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism Today: The Global Divide between Monopoly and Non-Monopoly Capital.” PhD thesis. Victoria University, Melbourne.

- Kliman, A. 2007. Reclaiming Marx’s Capital: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Krugman, P. 1994. “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle.” Foreign Affairs 73 (6):62–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/20046929.

- Kuznets, S. 1955. “Economic Growth and Income Inequality.” American Economic Review 45 (March):1–28.

- Kuznets, S. 1966. Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure and Spread. New Haven, CT. Yale University Press.

- Lee, Kang-Kook, and M. Siddique. 2021. “Financialization and Income Inequality: An Empirical Analysis.” The Japanese Political Economy. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/2329194X.2021.1945465.

- Mandel, E. 1976. Late Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Milanovic, B. 2005. Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Milanovic, B. 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Okishio, N. 1961. “Technical Changes and the Rate of Profit.” Kobe University Economic Review 7(1):85–99.

- Okishio, N. 2001. “Competition and Production Prices.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 25 (4):493–501. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/25.4.493.

- Page, J. 1993. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. New York, NY: World Bank/Oxford University Press.

- Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA; London: Belknap Press.

- Pomeranz, K. 2000. The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, MA: Princeton University Press.

- Prebisch, R. 1950. The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems. Lake Success, NY: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America.

- Pritchett, L. 1997. “Divergence, Big Time.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (3):14.

- Petit, Pascal. 2021. “Income Inequality: Past, Present and Future in a Political Economy Perspective.” The Japanese Political Economy.

- Reinert, E., ed., 2004. Globalization, Economic Development and Inequality: An Alternative Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Reinert, E. S., and K. S. Jomo. 2005. The Origins of Development Economics: How Schools of Economic Thought Have Addressed Development. London: Zed Press.

- Romer, P. M. 1994. “The Origins of Endogenous Growth.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 8 (1):3–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.1.3.

- Rostow, W. W. 1960. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Samuelson, P. A. 1948. “International Trade and the Equalisation of Factor Prices.” The Economic Journal 58 (230):163–184. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2225933.

- Samuelson, P. A. 1976. “Illogic of Neo-Marxian Doctrine of Unequal Exchange.” In Inflation, Trade and Taxes: Essays in Honour of Alice Bourneuf, edited by D. A. Belsley, E. J. Kane, P. A. Samuelson and R. M. Solow. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Singer, H. W. 1950. “The Distribution of Gains between Investing and Borrowing Countries.” American Economic Review 15 (Reprinted in Readings in International Economics. London, George Allen and Unwin, 1968).

- Sobolev, V. I. 2001. Brouwer Theorem’, Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Berlin: EMS Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E. 2002. Globalization and Its Discontents. New York and London: WW Norton.

- Stiglitz, J. E. 2017. The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do about Them. New York and London: WW Norton.

- Tawney, R. H. [1931]. 1983. Equality. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Todaro, M. 1995. Economic Development. 5th ed. New York, NY: Longman.

- Unni, J. 2005. “Wages and Incomes in Formal and Informal Sectors in India.” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 48 (2):311–317.

- Wade, R. H. 2018. “The Developmental State: Dead or Alive?” Development and Change 49 (2):518–546. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12381.

- Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2010. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin Books.

- Yoshihara, N., and S. Kaneko. 2016. “On the Existence and Characterization of Unequal Exchange in the Free Trade Equilibrium.” Metroeconomica 67 (2):210–241. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/meca.12125.

- Yoshihara, Naoki. 2021. “On the Labor Theory of Value as the Basis for the Analysis of Economic Inequality in the Capitalist Economy.” The Japanese Political Economy.