Abstract

Most American women wanting to avoid pregnancy use contraception, yet contraceptive failures are common. Guided by the Health Belief Model (HBM), we conducted a secondary qualitative analysis of interviews with women who described experiencing a contraceptive failure (n = 69) to examine why and how this outcome occurs. We found three primary drivers of contraceptive failures (health literacy and beliefs, partners and relationships, and structural barriers), and we identified pathways through which these drivers led to contraceptive failures that resulted in pregnancy. These findings have implications for how individuals can be better supported to select their preferred contraception during clinical contraceptive discussions.

Introduction

Contraception is an important tool that helps peopleFootnote1 to realize autonomy in decisions about whether, when, and how often to become pregnant. However, while most American women trying to avoid pregnancy use contraception (Kavanaugh & Pliskin, Citation2020), many experience contraceptive failure: Nearly half of unintended pregnancies occur among women who were using contraception in the month when they became pregnant (Finer & Henshaw, Citation2006). Method-specific contraceptive failure rates, which represent the risk of becoming pregnant among users of each method, are considered vital to individual decision-making about contraception and are heavily relied upon in clinical contraceptive discussions (Hatcher, Citation2018; Sundaram et al., Citation2017). Improving understanding of how and why contraceptive failures occur will ultimately contribute to a stronger evidence base from which clinicians and individuals themselves can draw to select their preferred contraception in alignment with their personal life circumstances.

Factors Influencing Contraceptive Behaviors, Broadly

In order to understand and explain the persistent gap between pregnancy desires and outcomes, decades of research have theorized and examined influences on contraceptive behavior, often within existing social-cognitive frameworks. One such framework, the Health Belief Model (HBM), posits that people will not enact a health-related behavior unless they perceive themselves to be susceptible to the “threat” of a health condition or illness (in this case, pregnancy) and they believe there is an efficacious treatment that will be worth the costs incurred by obtaining it (Becker et al., Citation1977). The less proximate factors comprising the “threat” interact with internal and external cues to action and cost-benefit analyses; these are further modified by a host of factors, including individual-level characteristics and experiences, as well as structural and social issues.

The HBM has been successfully adapted to explain contraceptive decision-making, although tests of the model’s validity when applied to a variety of contraceptive behaviors have had mixed results (Brown et al., Citation2011; Hester & Macrina, Citation1985; Roderique-Davies et al., Citation2016). Hall’s review concludes that despite its limitations, “the HBM provides a framework for predicting and explaining the complex systems of modern contraceptive behavior determinants and for promoting strategies to improve family planning outcomes” (Hall, Citation2012).

Indeed, most research on influences on contraceptive behavior explores domains of the HBM, even if that model did not explicitly guide the study design. Past research has identified several direct and indirect influences on contraceptive use, such as health beliefs and knowledge, partner relationships and dynamics, and structural factors. Perceptions of susceptibility to pregnancy and literacy in sexual and reproductive health have been shown to influence contraceptive use. Women may report a low susceptibility to pregnancy due to perceived invulnerability to pregnancy without contraceptive use, perceptions of subfecundity, inattention to the possibility of conception, and perceived protection from their current contraceptive use (Frohwirth et al., Citation2013; Kaye et al., Citation2009; Lawley et al., Citation2022; Polis & Zabin, Citation2012).

Research examining relationship dynamics has found that, during the initial or casual stage of a relationship, people are more likely to use less effective methods such as condoms, both in general and in a more consistent manner (Lansky et al., Citation1998; Macaluso et al., Citation2000). As relationships become closer and more established, a common “normative contraception transition script” leads people to switch from coital methods that are linked to a specific act of sex to more effective hormonal methods. Establishment of a long-term relationship may lead to a general relaxation of contraceptive use, particularly but not exclusively condom use (Gibbs et al., Citation2014; Nettleman et al., Citation2007), but a less stable relationship (one with many breakups and reconciliations) may lead to less-robust contraceptive use (Barber et al., Citation2019).

Considerations of sexual pleasure have also been shown to affect contraceptive decision-making. Women and men who feel that condom use diminishes their pleasure are more likely to use withdrawal (Higgins & Wang, Citation2015). The feeling of being “caught up in the heat of the moment” is a clear reason for the nonuse of a coital method (Nettleman et al., Citation2007). Finally, reproductive coercion, including behaviors such as unprotected forced sex, attempts to impregnate, contraceptive sabotage, and condom manipulation (Miller & Silverman, Citation2010; Moore et al., Citation2010), is a type of intimate partner violence involving both pregnancy promotion and abuse (Black et al., Citation2010) linked to both unintended pregnancy (Cizmeli et al, Citation2018; Samankasikorn et al., Citation2019) and decreased self-efficacy in condom negotiation (Jones et al., Citation2016).

Structural barriers to reproductive health care, and their effect on contraceptive use, are also well documented. Transportation, childcare, insurance, and appointment availability are all structural factors that affect people’s access to and use of contraception (Biggs et al., Citation2012). Insurance coverage is significantly associated with use of most-effective and moderately effective contraceptive methods in the United States (Kavanaugh et al., Citation2020), but even women with insurance face high out-of-pocket costs for contraception (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Citation2015). Grindlay and Grossman (Citation2016) found that a third of U.S. women who have ever tried to obtain prescription contraception faced several of these structural barriers, plus others, such as clinics’ requirements for visits, exams, or Pap smears; lack of a regular doctor or clinic; and difficulty accessing a pharmacy. Women affected by structural racism, such as immigrants and members of racial and ethnic minorities, have been shown over time to have limited access to the sexual and reproductive health care that they need (Dehlendorf et al., Citation2010).

Examining Contraceptive Failure as a Unique and Distinct Outcome of Contraceptive Use

Health beliefs, relationships, and structural factors demonstrably impact contraceptive behaviors. However, most of the literature documenting these and other influences on contraceptive use within these key domains of the HBM has not explicitly delved into the specific phenomenon of contraceptive failures to understand how they happen and what causes them. Contraceptive failure is most commonly expressed in terms of two types of method-specific failure rates. “Perfect use” failure rates refer to how frequently users become pregnant when a method is used consistently and correctly and often are measured through clinical trials (Trussell, Citation2011). “Typical use” rates refer to failures under typical conditions, including incorrect or inconsistent use, and generally draw on data from population-based surveys of actual users’ experiences. Differences between perfect use and typical use failure rates for any method are interpreted as indicative of how difficult a method is to use (Guttmacher Institute, Citation2020), but evidence on the complexity of behaviors and circumstances that influence this gap is limited.

To address these gaps, we apply the HBM to qualitative data containing in-depth descriptions of contraceptive behaviors that lead to pregnancies and examine the ways in which health beliefs, behaviors, and context contribute to contraceptive failure. Our objective is to understand how and why “typical use” contraceptive failures occur, with specific attention to key HBM domains of influence that have been identified in the literature for contraceptive behavior more generally, and to describe the specific pathways by which these domains manifest as the “incorrect” and “inconsistent” use of methods that result in pregnancies that people try to prevent.

Materials and Methods

Data

Amplified, supplementary analysis of existing qualitative data has been shown to be an efficient method for exploring related topics (Heaton, Citation2008; Long-Sutehall et al., Citation2011). Here, we combine data from two past studies carried out by our institution to conduct such an analysis. One data set, collected in 2008, consisted of in-depth interviews conducted with 49 women aged 18 to 44 years who were obtaining abortions at clinics in Texas, Connecticut, and Washington. Three researchers, two of whom were authors of the initial study, conducted the interviews; respondents were recruited from abortion clinics and received $35 cash for their time. The study focused on women’s abortion experiences and decision-making. (More detail on study methods can be found in the primary analysis of the original study [Moore et al., Citation2011].) The other data set, collected in 2014, contains information from in-depth interviews with 35 women aged 25 to 44 years in Connecticut and Oklahoma who had had a child 1 to 4 years prior to the interview and who indicated during screening that their pregnancies were unintended. Respondents were recruited to that study using recruitment firms and Craigslist and received $100 in cash; interviews were conducted by four researchers, all of whom were authors of the initial study. These data were used to study impacts of unintended pregnancy on parents’ lives. (More detail on study methods can be found in the primary analysis of the original study [Kavanaugh et al., Citation2017].)

Although these data were collected for studies not focused on contraceptive use or failure, respondents were asked about contraceptive methods they had used prior to their pregnancies, the consistency and correctness of their use, episodes and periods of nonuse, underreported methods such as withdrawal and fertility awareness–based methods (FABMs), and their perceived likelihood of pregnancy. Both data sets also included information about respondents’ desire to avoid pregnancy and their discussions with partners about contraceptive use. Finally, both data sets have information on other factors included in the HBM, such as respondents’ cost-benefit assessments of particular methods and modifying or enabling factors (e.g., demographic, social and psychological characteristics, and reproductive experiences).

Data were transcribed verbatim, cleaned of errors, and stripped of identifying information as part of the original studies. Data collection and design of the two previous studies were approved by the Guttmacher Institute’s federally registered Institutional Review Board; this study was considered exempt.

Analysis

To guide our inquiry, we developed and applied a coding scheme for the transcripts based on Hall’s application of the HBM to explain contraceptive decision-making (Hall, Citation2012). Our codes corresponded to the factors or groups of similar factors (or domains) identified by Hall as potential influences on contraceptive use. The coding team of six researchers (all of whom are authors) coded all transcriptsFootnote2 using this coding scheme in NVivo12 (QSR International) and periodically assessed and resolved coding discrepancies through discussion. Our finalized coding scheme included deductive nodes from the HBM and other inductive nodes that emerged empirically from the data.

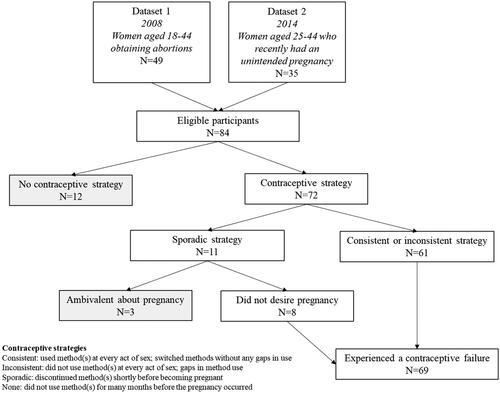

All 84 respondents in our input data sets experienced a pregnancy (). To identify which narratives described the experience of a contraceptive failure, we examined nodes related to two key components of that phenomenon—contraceptive behaviors and pregnancy desire (Hall, Citation2012). We classified the consistency of each respondents’ contraceptive strategy using a 4-point scale (consistent, inconsistent, sporadic, no strategy); respondents who indicated that they used any form of contraception at or around the time that they became pregnant and had a consistent or inconsistent contraceptive strategy were included in our sample. Among respondents who described using a more sporadic contraceptive strategy, or discontinuing a method or methods around the time of becoming pregnant, those who indicated that they did not desire a pregnancy at that time were also included. Sixty-nine of the original 84 respondents were classified as having experienced a contraceptive failure and were therefore included in our analytic sample; we resolved classification disputes through discussion.

Cross-case analysis was conducted to identify themes and concepts and to explore similarities and differences (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Key relevant topics were summarized via textured description and illustrated using direct quotes from respondents (Moustakas, Citation1994).

Based on coding frequency, we identified key domains of the HBM and potential factors within those domains that may have influenced respondents’ experiences of contraceptive failure. We also applied Frohwirth et al.’s (Citation2016) concept of contraceptive mechanisms, or granular use practices, to further understand the pathways by which influencing factors translated into specific contraceptive behaviors or practices within these narratives describing contraceptive failures. Quotes are presented verbatim (with information added for clarity provided in brackets) and identified by a randomized number, to avoid inherent assumptions from assigned pseudonyms (Allen & Wiles, Citation2016). When we paraphrase or illustrate respondents’ contraceptive behavior without using direct quotes, our descriptions reflect how respondents themselves reported these experiences.

Results

Among the 69 respondents identified as having experienced a contraceptive failure, more than one-third were non-Hispanic White, about one-third were Hispanic, and more than one-fifth were non-Hispanic Black (). Almost three-quarters had a low income (with incomes lower than 200% of the federal poverty level) and were younger than 30 years. Most had completed high school or some college. More than half had children and were not married or cohabiting.

Table 1. Number and percentage of respondents by demographic characteristics.

Our respondents described using a wide range of contraceptive methods, though all could be categorized as “moderately effective” or “least effective” methods (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2014). Condoms and pills were among the most common methods used, and nearly half of respondents used withdrawal; many of these methods were used in combination. Less frequently mentioned methods were injectables, the contraceptive ring, FABMs, emergency contraception, abstinence, sterilization, suppositories, foam, and diaphragms. No one who described using FABMs in our sample was using any formal method, and none had received any training or instruction; they relied on tracking apps and their own understanding of fertility within their menstrual cycles. No respondent described using the contraceptive patch, an intrauterine device (IUD), or a contraceptive implant.

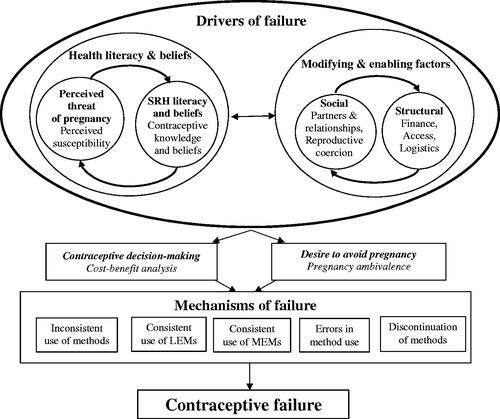

Within our respondents’ narratives, three main drivers of the experience of contraceptive failure mapped onto the HBM’s key domains: health literacy and beliefs (present within HBM construct of “threats”), partners and relationships, and structural barriers (both falling within the modifying and enabling factors in the HBM). Most respondents’ experiences were driven by factors from multiple domains.

We also identified five distinct categories of contraceptive mechanisms closest to the pregnancy, which we call “mechanisms of failure”: inconsistent use of methods (n = 27); consistent use of less effective methods (n = 20); consistent use of moderately effective methods (n = 10); early discontinuation of methods around the time of pregnancy (n = 8); and challenges in executing method guidance (n = 4).

Below we illustrate why and how contraceptive failures occurred in our data by presenting factors within the domains of the HBM that we identified as drivers of contraceptive failure for our respondents, and we show how these factors manifested through specific mechanisms of failure.

Health Literacy and Beliefs

Two main factors within the domain of health literacy and beliefs impacted respondents’ risk of contraceptive failure: perceptions of susceptibility to pregnancy and erroneous health beliefs about the functioning of contraceptive methods. These two factors were explicitly drawn out in the interview guides and therefore were present in all of the respondents’ narratives.

Perceptions of susceptibility to pregnancy often drove contraceptive failures through the mechanism of consistent use of less effective methods. This respondent believed she was subfertile, which drove her decision to use only withdrawal:

If I knew I could’ve gotten pregnant, I probably would have used protection, have him use protection, you know, me try to take birth control pills and him use a condom, but I was like, I can’t get pregnant. (Respondent 55)

Perceptions of subfertility also led to the mechanism of early contraceptive discontinuation. Respondents described doing so because they thought they were subfertile and then became pregnant within a few weeks or months of having stopped. Such discontinuation was often based on feelings about specific medical conditions. Respondent 1 had been using pills, but she was told by a doctor that she had polycystic ovarian syndrome, which she felt made it unlikely that she could become pregnant. She stopped taking the pill after an unrelated illness and did not start or substitute any other method based on this perception as well as on a belief that hormonal contraceptive use provides long-acting protection even after discontinuation:

I know it only takes one time, but you never think that “oh it will happen to me” […] And I guess I kind of forgot that issue for a second, or naively thought that since I had been taking it [the pill] for so long, what are the odds that it’s really going to affect me this month? And so we had unprotected sex.

Respondent 1’s contraceptive failure was driven by a combination of perceptions of subfertility and another factor within the domain of health knowledge and beliefs: low sexual and reproductive health literacy. Erroneous beliefs about how contraception affects the body were also associated with the mechanism of inconsistent method use. Respondent 32 used pills but did not take them every day, believing that it did not matter if she skipped a day:

I just thought they were like since I was on them, they were like magic. If I missed it one day, it wouldn’t really matter; “I am on the pill,” and it was just so stupid, I didn’t think it all the way through of course.

Other respondents, who experienced contraceptive failure while consistently using moderately effective methods such as pills, injectables, and the ring, often described health beliefs that allowed them to explain what happened. Although switching methods without a gap should not expose a person to pregnancy, respondents who used their hormonal methods consistently often believed that the act of switching may have been why the method failed:

I think—they had changed from one [pill] to another because of me being that age, they didn’t like the side effects it was giving me, so they changed me to another one. And I think when the change happened, the change of medication, that either I did something wrong, or it just wasn’t strong enough or something, and I ended up being pregnant. (Respondent 29)

This respondent questioned the strength of the pill, a health belief expressed by several other consistent users of hormonal methods trying to make sense of how their pregnancies occurred.

Other consistent users of moderately effective methods perceived that the pregnancy was the result of failing to switch methods, because of a perception that using one (hormonal) method for too long leads to it becoming ineffective:

And I have taken the Depo shot faithfully every three months, however, the percentage chance, which is like one, or whatever percent chance that you have of becoming pregnant, I did, or I possibly became immune to the fact that I used the contraceptive for too long […] So that’s pretty much what I think led to [the pregnancy]. (Respondent 19)

The domain of health beliefs and literacy also drove the contraceptive failures of all four respondents whose failures occurred due to the mechanism of challenges in executing method guidance. Misunderstandings of how to track and interpret cyclical fluctuations in fertility led directly to errors in the use of FABMs for three respondents, none of whom had been formally trained to use these methods:

For us, it was—I mean, [withdrawal] was—basically working. What I actually did is, you know how they come—the rhythm—and you try to count the days, so I'm like, okay, I'm going to go ahead and let you do that [ejaculate inside the vagina] […] That wasn’t the best decision. (Respondent 57)

Partners and Relationships

Several factors drove contraceptive failure within the partners and relationships domain: relationship stage and stability; sexual pleasure; and reproductive coercion. As with health literacy and beliefs, all respondents described the influence of this domain on their experience of contraceptive failure because this discussion was elicited in the interview guides.

The stage or length of a partnership appeared to drive the experience of contraceptive failure through consistent use of less effective methods (at least one method at every act of sex), including coital methods such as withdrawal, FABMs, barrier methods, and emergency contraception. Several respondents described newly initiated or early-stage relationships and explicitly connected the length or development of their relationship to their use of such methods:

He was wearing a condom and I wasn’t on any form of birth control. I hadn’t been in a relationship in a very long time […] I am sure if we had been dating longer, I would have considered getting on something. (Respondent 2)

Relationship stage also drove contraceptive failures through the mechanism of inconsistent use. Several respondents described how the deepening of their relationship over time led to a less fastidious use of withdrawal:

And we started pulling out first, and then as we got into the relationship, it was he stayed in […] There was one time that we didn’t [use withdrawal], which I am pretty sure is the time that I got pregnant. (Respondent 36)

Relationship instability also drove contraceptive failure; just over half of our respondents depicted unclear or unstable relationships or reported conflict or infidelity. These unstable relationships often led to contraceptive failures via inconsistent method use. Respondent 46 and her husband used condoms, but not at every act of sex. They were separated, but resumed their sexual partnership spontaneously:

We weren’t occasionally seeing one another, but it happened to be that we were still talking and discussing the problems we had in a relationship, and all that kind of stuff. … So it was just one of those things that just happened. It wasn’t planned.

Respondents’ sexual pleasure was also an influence on their contraceptive behaviors and therefore drove their contraceptive failures. Many cited being “caught up in the moment” with their partner as a factor in inconsistent method use. Respondent 45 discontinued condoms because she and her partner did not like how they felt and switched to inconsistent withdrawal and informal FABMs. She describes being chiefly concerned with sexual pleasure and not wanting to think about “consequences” (pregnancy), leading her partner to sometimes forgo using withdrawal:

There was a part of me every time that would get scared, probably half and half, but you don’t really have a straight head when you are in the peak of it […] the height of sexual, your peak of your sexual, the climax when you are ready to get it on. So, you just want it and you go for it and not really think about the consequences.

The experiences of contraceptive failure described by our respondents in this domain were also driven by reproductive coercion. One-third of our sample (n = 23) reported that they experienced some form of reproductive coercion around the time that they became pregnant, including pregnancy promotion, contraceptive sabotage, and sexual violence. This factor manifested through several mechanisms of failure: inconsistent use of methods, consistent use of less effective methods, and method discontinuation. Respondents talked about pregnancy promotion and contraceptive sabotage by their partners leading to inconsistent use of coital methods:

I: So were you guys sort of pulling out sometimes?

R: Yeah, that’s what I always tell him, but it didn’t always work, maybe like a couple of times …

I: So you feel like it was kind of him not doing what he was supposed to do?

R: Right. […]

I: So what was his response to when you would say this kind of thing?

R: He’ll do it, he swears he’ll do it the next time.

I: Do you think he wanted you to be pregnant?

R: I think so. (Respondent 34)

Reproductive coercion was also associated with consistent use of less effective methods. Respondent 20 and her partner used condoms at every act of sex. When reflecting on how their strategy might have failed her, she speculated that it might have been the result of pregnancy promotion and condom manipulation by her partner:

[We used condoms] every time. That’s why I was like, wait, how is that possible? But he told me he had history, like, with one of his other kids where the condom—he had a condom on, but somehow she got pregnant, and I was like, the condom busted? He was like, he is not sure. So I don’t know, I am a little skeptical. He probably poked a hole in it, you never know.

This respondent’s experience illustrates that even consistent users may be exposed to the possibility of contraceptive failure through reliance on less effective methods over which their male partners have direct control.

Structural Barriers

Respondents also described how structural barriers drove their contraceptive failures. Specifically, financial and logistical barriers contributed to contraceptive failures when methods were too difficult or inconvenient to access and use. This domain was not explicitly elicited during interviews, yet for more than one-third of respondents (n = 25) it directly or indirectly drove their contraceptive failures through the mechanisms of discontinuation, consistent use of less effective methods and inconsistent contraceptive use.

Respondents who had relied on consistent use of less effective methods were mostly doing so because structural barriers had led them to discontinue methods that were more effective but more difficult to access. Respondent 9 lost access to her doctor for both financial and logistical reasons and did not resume pill use as a result:

Well, you have to go to the doctor first to get [a] prescription, and I haven’t seen my doctor in years, and I don’t have one here in [city]. It’s a lot of money, and my dad’s insurance kicked me off, and my plan is basically there in case I get really, really hurt, so I guess, you know, it’s a lot of money.

Her discontinuation of pills was followed by the consistent use of less effective coital methods; she and her partner used condoms inconsistently, but always used withdrawal if they did not use a condom.

Logistical and financial barriers also led to contraceptive failure for respondents who used methods inconsistently. Many described either losing access to a method or being prevented from starting a method they wanted due to financial or logistical obstacles. They then turned to a second-choice method or a combination of methods, which they used inconsistently. As previously described, Respondent 45 and her partner discontinued condoms and used withdrawal inconsistently because those methods interfered with their sexual pleasure. She expressed a desire to use a noncoital method but was confronted by logistical and financial barriers:

I really want to get on the IUD, but I want one without hormones. I don’t know. I am so busy, like, I am in school and with my kids, I never take time for myself to go do that, and I should […] But I don’t know, because I am low-income, if I can get it for $500, or can get it for free.

Structural barriers such as termination of insurance coverage often interfered with respondents’ ability to obtain and use a preferred method:

When my insurance ended, I wasn’t able to get more of [the] birth control pill. (Respondent 67)

Other structural barriers arose when respondents experienced extreme stress from financial responsibilities and the need to work long hours, which led to method discontinuation. Respondent 65 discontinued her use of the injectable and could not find time to replace it:

You go and get [injections], like, every three months, and it had been, like, five, and I just took over a new business, and I am working like 90 hours a week […] So, I completely didn’t even think about it, I mean we don’t even really have sex all that often anymore. I mean, it’s like, when I am going 90 hours a week, I am waitressing, bartending and trying to take over [a] coffee shop and not really thinking about like sleeping with him.

Intersecting Domains and the Particular Role of Structural Factors

Just as a person’s contraceptive behaviors often include multiple methods and mechanisms of use, contraceptive failures may also be driven by numerous overlapping factors from each of the three domains identified above. Specifically, because structural factors were not explicitly discussed in every interview, examples of narratives containing factors from this and other domains may help to illustrate the accumulation of influences in people’s experiences.

Assessing how this domain intersects with factors associated with other domains reveals the ways in which structural barriers may exacerbate other driving factors. Respondent 37 was initially a pill user who discontinued use because of structural barriers, specifically related to her financial, insurance, and immigration statuses. She and her partner then switched to a combination of condoms and withdrawal, neither of which was used at every act of sex:

R: We had to use condoms. I mean, I had taken … pills, but I stopped taking it because I just simply didn’t have a time to come to [the clinic] or something. And I don’t have insurance because I am not a citizen here, so I was just not willing to come to [a] hospital of any sort, so I stopped taking the pill. And after that, we just used condoms.

I: Did you ever have sex where you were not using condoms and he would pull out?

R: Well, sometimes, he would; sometimes, he wouldn’t. And so yeah, we had unprotected sex.

She further described the loosening of strict control over coital method use as a function of being in an established relationship, where they no longer had to worry about exposure to sexually transmitted infection:

He was asking me if he could [have sex without a condom], and I was constantly saying no because I was afraid, both in a way I could get pregnant, and I didn’t know what this person had. I know that, like, neither one of us didn’t have [an] STD or anything now, but I wasn’t sure, like, at the first if he was safe. But as time passes by, it’s not that I was comfortable [with] not using any type of protection, but I just went with it and it started like that.

For Respondent 37, structural barriers intersected with relational ones. Increased trust within the relationship drove irregular condom use and acquiescing to occasional nonuse became normalized. Once she lost access to the pill, this inconsistent use resulted in her pregnancy.

Respondent 41 described her partner’s inconsistent use of withdrawal and her lack of control over his contraceptive behavior:

Well, most of the time, he [pulls out]. But sometimes he doesn’t, so there is only like once in a blue that he doesn’t, and it makes me so upset.

Similarly, Respondent 41’s proximal mechanism of failure was inconsistent withdrawal use, and its proximal driver was her partner’s coercion. However, this respondent had not wanted to rely on withdrawal and desired a tubal ligation. Her need to work and care for her kids meant that she could not find time to get to a doctor's appointment:

I have got a boy and a girl, so I am all set. I want to get operated, but I just, you know, my work schedule, and now I have to move, and a whole bunch of stuff that’s going on, I haven’t had the time to, like, take out to call my doctor and set up the appointment and all that. But yeah, I want to get operated; I don’t want any more. … I am constantly working, and when I am not working, I am home with the kids. I am just always so beat.

Further, the doctor had limited availability, creating an additional hurdle:

And I try … to make an appointment with my doctor, but she is so backed up for months that it’s ridiculous…, you know. So… by the time the date comes, I forgot, I am at work. My alarm is going off on my phone that, “Oh now is your date for your doctor’s appointment.” [But] I can't go now.

She felt that sterilization was the right method for her, but she was unable to obtain it because of multiple structural barriers. Instead, she had to rely on a less effective method that was used inconsistently because of her partner’s refusal; the intersection of structural and relational factors resulted in her unwanted pregnancy.

Discussion

Many people experience contraceptive failure, and there is a breadth of evidence on the correlates of contraceptive failure across a variety of settings (Black et al., Citation2010; Bradley et al., Citation2019; Sundaram et al., Citation2017), yet research investigating exactly how and why this outcome continues to be a common one in the United States is limited. Despite a plethora of research on influences on contraceptive behaviors, especially those identified as likely to result in pregnancy such as inconsistent use, this is the first study we are aware of that explicitly examines the experience of contraceptive failure. We applied a modified HBM to narratives of this experience and identified domains within that model (health literacy and beliefs, relationships and partners, structural barriers) that drive the behavioral mechanisms of contraceptive use (inconsistent use of methods, consistent use of less and moderately effective methods, early discontinuation of methods and challenges in executing method guidance) closely associated with the phenomenon.

Our findings indicate that people who experience contraceptive failure often navigate a complex constellation of factors that impact their fertility experiences. We capture this confluence by situating our findings on the factors and behavioral mechanisms that contribute to contraceptive failures within Hall’s (Citation2012) modified HBM (see ), which lays out factors in specific domains that influence contraceptive decision-making. Our findings extend this model, documenting how these domains drive behavioral mechanisms associated with the experience of contraceptive failure as the key outcome of interest.

Our evolution of Hall’s (Citation2012) HBM adaptation seeks to emphasize the interconnectedness of the domains as well as to highlight the mechanisms that emerged as most salient to contraceptive failure. This adaptation illustrates how overlapping factors in the HBM that may impact contraceptive behavior can also combine to drive the specific mechanisms that cause contraceptive failure.

In the domain of health literacy and beliefs, factors documented as impacting contraceptive behavior (Frohwirth et al., Citation2013; Kaye et al., Citation2009; Polis & Zabin, Citation2012) also drove the more specific experience of contraceptive failure. Respondents described how feeling protected from the threat of pregnancy because they thought they were subfertile led them to discontinue methods and to use them inconsistently. A more limited body of work has examined people’s perceptions of how contraceptives work in the body (Shedlin et al., Citation2013) and of how cyclical fertility fluctuations function (Guzman et al., Citation2013); this has shown some impact of these perceptions on contraceptive use (Frost et al., Citation2012). Our findings illustrate how these perceptions and understandings motivate mechanisms of contraceptive failure.

Our adaptation of the HBM emphasizes the influence of health beliefs and desire to avoid pregnancy on contraceptive behaviors; Hall’s (Citation2012) modified HBM, which is focused on general contraceptive behaviors, placed these factors more in the background. Although this domain reflects individual-level perceptions and knowledge and, in our data, includes instances of some individuals placing the fault for the failure squarely on their own shoulders, it is shaped by larger, structural systems. Lack of access to accurate, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education is endemic to educational systems in the United States (Santelli et al., Citation2017) and thus functions as a social determinant of contraceptive failure.

In Hall’s (Citation2012) adaptation of the HBM, relationships and structural barriers serve to modify the influence of other elements; our findings indicate that, when the result ends with a contraceptive failure, these domains influence contraceptive behaviors in their own right. Relationship context can directly and indirectly influence contraceptive use: During the initial or casual stage of a relationship, less effective methods are more likely to be used (Lansky et al., Citation1998; Macaluso et al., Citation2000); our findings reveal that even consistent use of less effective methods can be a mechanism of failure. Inconsistent use of methods has been shown to occur in some relationships as they progress and strengthen (Gibbs et al., Citation2014; Lansky et al., Citation1998; Macaluso et al., Citation2000); we found that inconsistent use driven by relationship progression also manifested in contraceptive failure.

Our findings also support other research demonstrating the ways in which unstable or “churning” relationships (those with many breakups and reconciliations) may lead to inconsistent contraceptive use (Barber et al., Citation2019). Within sexual relationships, both consistent use of less effective methods and inconsistent use of coital methods were associated with the foregrounding of sexual pleasure, extending other research examining these connections to the phenomenon of contraceptive failure (Higgins & Wang, Citation2015; Nettleman et al., Citation2007). Finally, our findings highlight behavioral mechanisms of failure driven by reproductive coercion. Gendered violence and belief systems that support it enable the reproductive coercion driving multiple mechanisms of failure in our data and inform the themes of relationship stability and prioritization of male sexual pleasure that we saw driving the mechanism of inconsistent use.

Structural barriers to reproductive health care, which were articulated by our respondents as being primarily financial and logistical, directly impacted their ability to obtain or use their preferred contraceptive methods and therefore led to their experiences of contraceptive failure, corroborating others’ research (Potter et al., Citation2017). In our findings, financial and logistical barriers were most often cited as the reason for the gap between their desires and their contraceptive practices. Structural barriers that mediate individuals’ ability to access care and their preferred contraceptive methods are often considered to be issues of “convenience.” However, convenience matters when people are forced to prioritize necessities and to make choices with a limited or constrained range of options in the context of such realities as housing location and physical access to health facilities. For our respondents, as in other studies (Biggs et al., Citation2012; Grindlay & Grossman, Citation2016; Holt et al., Citation2020; Kavanaugh et al., Citation2020), discontinuing a contraceptive method, switching to a less effective method, and using methods inconsistently were all different manifestations of struggling to overcome structural barriers.

Additionally, although our data include a time period before the contraceptive coverage mandates included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010 were in effect, various loopholes mean that people still incur costs for contraception even with this protective legislation (Guttmacher Institute, Citation2021). When a health care system does not provide free and broadly accessible essential care, conditions are ripe for failure of more effective contraceptive methods that require frequent, regular contact with the health care system. By limiting the type and quality of health insurance available to people with marginalized identities, such as immigrants and people who are not employed, the U.S. health care system exacerbates inequity and perpetuates oppressive systems, including racism and classism (McGovern, Citation2014; Sonfield et al., Citation2020).

Though many factors and mechanisms discussed in these findings have been previously identified as associated with contraceptive behavior and failure (Black et al., Citation2010), this analysis illustrates how these associations actually work within people’s lives. Our evolution of Hall’s (Citation2012) modified HBM for the specific outcome of contraceptive failure provides just one example of how this model may prove useful in guiding further inquiry into, and reflections about, the variety of factors at play in influencing both this specific outcome as well as a range of other contraceptive behaviors and outcomes.

Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

Our findings on the complexity and nuance of contraceptive failures have implications for future research, both in terms of how to understand contraceptive failure and of how to measure it. Our findings indicate that the concept of “mechanisms” of use (Frohwirth et al., Citation2016) deserves more attention; potential future quantitative research could attempt to measure the extent to which the mechanisms of failure seen in our sample of patients undergoing abortion and parents of children born from unintended pregnancies are present in broader populations of individuals.

Data on the key components for calculating typical use failure rates, contraceptive method use, and pregnancy come from a population-based survey, the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraceptive use is measured using a recoded variable representing the single most effective method used by a respondent in the month they reported a pregnancy (Sundaram et al., Citation2017). Our findings highlight that contraceptive failures involve not only individual methods but also frequent and complex method combinations (Frohwirth et al., Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2014; Kavanaugh et al., Citation2021). Multimethod use is crucial for measuring and understanding the phenomenon, both because this kind of use affects the calculation of failure rates for individual methods that must be accounted for and because it affects a person’s true exposure to the risk of pregnancy. Newly designed studies (Jones et al., Citation2014), as well as analyses of the NSFG (Polis & Jones, Citation2018), show that complexity in measurement is possible; these techniques could be incorporated into calculations of method failure rates. In addition, attributing the occurrence of a pregnancy around the time of method use to contraceptive failure, while expedient, fails to account for the spectrum of people’s feelings about pregnancy; some pregnancies occurring while a woman uses contraception may not be totally unwanted, and some may even be desired (Aiken et al., Citation2016; Barrett & Wellings, Citation2002).

Our findings also point to the possibility of extending the timeframe under investigation when exploring the phenomenon of contraceptive failure. Many of our respondents described a lengthy process of discontinuing a series of methods before experiencing a failure. Previous work supports the notion that these women experienced contraceptive failures despite not using a method in the time immediately preceding their pregnancies or that methods used outside of this timeframe could be considered to have failed these users (Daniels et al., Citation2020; Frost et al., Citation2007; Guttmacher Institute, Citation2020). Although method-specific rate calculations must center on the month in which a pregnancy occurred, other examinations of contraceptive failure could expand the timeframe under scrutiny to better understand this cascade.

Our findings also may inform understanding of the societal level at which the drivers of contraceptive failures occur. Social and individual-level factors have received a great deal of attention in applications of the HBM to contraceptive behaviors (Barber et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2011; Frohwirth et al., Citation2013; Frost et al., Citation2012; Hester & Macrina, Citation1985; Higgins & Wang, Citation2015; Kaye et al., Citation2009; Moore et al., Citation2010; Polis & Zabin, Citation2012; Roderique-Davies et al., Citation2016; Shedlin et al., Citation2013). However, it is important to recognize the unequal distribution of contraceptive failure in the United States, with higher rates among historically oppressed population groups (Sundaram et al., Citation2017), who also experience higher rates of unintended pregnancies (Guttmacher Institute, Citation2019) and abortions (Jerman et al., Citation2016). These persistent disparities across sexual and reproductive outcomes highlight the importance of accounting for the ways in which factors present at the societal and structural level can act as barriers or enablers of overall sexual and reproductive well-being (Dehlendorf et al., Citation2021). Our findings, based on a sample of mostly poor and low-income women of color, support the idea that reproductive and sexual health equity will not be achieved without ameliorating the social and structural factors that produce these inequities in the first place, as individual-level behaviors that lead to contraceptive failures sit within, and interact with, larger systems.

Clinicians can—with caution—use these findings on the mechanisms and potential drivers of contraceptive failure to provide individualized and collaborative care that attends to the contexts of people’s lives. People design their contraceptive strategies to meet a host of needs; effectiveness is only one consideration among many, and preferences for features of methods may vary (Frohwirth et al., Citation2016; Jackson et al., Citation2016; Reed et al., Citation2014). Previous syntheses have identified both contraceptive behaviors and factors associated with contraceptive failure (Black et al., Citation2010; Guttmacher Institute, Citation2020); contraceptive methods with little room for user error, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives are often proposed as the solution to the problem of contraceptive failure. Just as other researchers and clinicians have called for balancing contraceptive counseling informed by tiered effectiveness charts with a more holistic approach to patient preferences (Brandi & Fuentes, Citation2020; Gomez et al., Citation2014; Gomez & Wapman, Citation2017), our identification of mechanisms of failure should not be interpreted as evidence that patient preferences for less effective methods or moderately effective methods should not be respected. Patient-centered contraceptive counseling approaches (Dehlendorf et al., Citation2010; Holt et al., Citation2020) can help ensure that individuals’ needs, including the need for effective contraceptive strategies, are met holistically. In these approaches, the use of less effective methods is not a problem to be solved by promoting long-acting reversible contraceptives, but a valid choice that deserves respect and attention from clinicians.

Limitations

We conducted secondary data analysis, and the original studies’ interview guides were not designed to address this study’s research focus on contraceptive failure. Although factors that emerged as relevant to contraceptive failure in our study align with common influences on contraceptive behavior in the literature, it is possible that a study designed specifically to examine contraceptive failure through the lens of the HBM would have yielded richer, or different, results.

Given that our sample comprised women obtaining abortions and women who classified their births as unintended, it is not surprising that most described a strong and unequivocal desire to avoid pregnancy at the time of pregnancy. Our rubric for selection into the analysis allowed for women to be designated as having experienced contraceptive failures if their desire to avoid pregnancy was ambiguous but they were using contraception to prevent pregnancy. It is possible that their experiences of contraceptive failure are distinct from those of respondents who expressed clear desires to avoid pregnancy, but our analysis was not able to detect this.

Respondents in data set 2 were interviewed between 1 and 4 years after the birth of their last child. Therefore, their recollections of the circumstances of their lives and their contraceptive behavior around the time that they became pregnant are likely subject to some recall bias. None of our respondents used highly effective long-acting reversible methods, most likely because contraceptive failure is rare among users of these methods. This may reflect the time period in which our data were collected; at the national level, the proportion of all contraceptive users who used long-acting reversible methods increased from 6% to 14% between 2008 (data set 1) and 2014 (data set 2) (Kavanaugh & Jerman, Citation2018). The contraceptive method mix among our respondents may also have influenced the drivers of contraceptive failure identified in these data; for example, although discontinuation due to bleeding side effects has been documented among long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) users more recently (Villavicencio & Allen, Citation2016), this particular driver of contraceptive failure did not emerge as salient within our sample of non-LARC users. We posit that our findings within the domain of structural barriers, especially, would be most applicable to understanding contraceptive failures associated with today’s most commonly used methods, especially some of the most and moderately effective methods that were less commonly used at the time of these data and are often some of the most expensive (Kavanaugh & Pliskin, Citation2020). Additional examination of the extent to which the domains of health literacy and beliefs and partner relationships lead to contraceptive failures of these most and moderately effective methods, in particular, is warranted.

Conclusions

Contraceptive failure is a complex phenomenon, occurring as an outcome of specific behavioral mechanisms of method use. We identified five behavioral mechanisms that individuals themselves closely associated with their own experiences of method failure: inconsistent use of any method, consistent use of less effective methods, consistent use of moderately effective methods, early discontinuation, and challenges in executing method guidance. Each of these mechanisms was driven by a host of interconnected factors related to health literacy and beliefs, partner relationships, and structural barriers that limited method choice and use. Our findings indicate that the drivers of contraceptive failure occur at different levels that are all nested within systemic and social structures. These findings and our adaptations of the HBM may inform further work to identify the specific correlates of contraceptive failure as well as indicate opportunities for improving clinical practice in contraceptive encounters. Ultimately, an improved understanding of contraceptive failure among individuals, clinicians, educators, and administrators will contribute to people’s enhanced ability to leverage this information in service of enacting their contraceptive preferences to realize this aspect of reproductive autonomy.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the commitment and participation of the study participants. We would also like to thank Kathryn Kost and Isaac Maddow-Zimet of the Guttmacher Institute for their thoughtful and thorough review.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The consent forms signed by research participants for the input data sets do not allow for public sharing of these data.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 People of all gender identities use contraception, and we prioritize using gender-neutral language in this manuscript to reflect that reality. In instances where we cite other research that describes more narrowly defined populations and samples, such as women or contraceptive users, we reflect the terminology used in those studies.

2 The size of the coding team was due to staff turnover during the analytic period; when coding tasks transitioned between coders, the final coder reviewed all of the previous coders’ work to ensure comparability and to confirm that all subsequent coding updates had been incorporated.

References

- Aiken, A. R. A., Borrero, S., Callegari, L. S., & Dehlendorf, C. (2016). Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: Unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 48(3), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1363/48e10316

- Allen, R. E. S., & Wiles, J. L. (2016). A rose by any other name: Participants choosing research pseudonyms. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 13(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2015.1133746

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2015). Committee on health care for underserved women: Access to contraception [Committee Opinion No. 615]. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/01/access-to-contraception

- Barber, J. S., Miller, W., Kusunoki, Y., Hayford, S. R., & Guzzo, K. B. (2019). Intimate relationship dynamics and changing desire for pregnancy among young women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 51(3), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12119

- Barrett, G., & Wellings, K. (2002). What is a “planned” pregnancy? Empirical data from a British study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 55(4), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00187-3

- Becker, M. H., Haefner, D. P., Kasl, S. V., Kirscht, J. P., Maiman, L. A., & Rosenstock, I. M. (1977). Selected psychosocial models and correlates of individual health-related behaviors. Medical Care, 15(5 SUPPL), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-197705001-00005

- Biggs, M. A., Karasek, D., & Foster, D. G. (2012). Unprotected intercourse among women wanting to avoid pregnancy: Attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs. Women's Health Issues, 22(3), e311–e318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2012.03.003

- Black, K. I., Gupta, S., Rassi, A., & Kubba, A. (2010). Why do women experience untimed pregnancies? A review of contraceptive failure rates. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 24(4), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.02.002

- Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2010). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary report (p. 124). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Bradley, S. E. K., Polis, C. B., Bankole, A., & Croft, T. (2019). Global contraceptive failure rates: Who Is most at risk? Studies in Family Planning, 50(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12085

- Brandi, K., & Fuentes, L. (2020). The history of tiered-effectiveness contraceptive counseling and the importance of patient-centered family planning care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222(4S), S873–S877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1271

- Brown, W., Ottney, A., & Nguyen, S. (2011). Breaking the barrier: The Health Belief Model and patient perceptions regarding contraception. Contraception, 83(5), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2010.09.010

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Effectiveness of family planning methods. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/UnintendedPregnancy/PDF/Family-Planning-Methods-2014.pdf

- Cizmeli, C., Lobel, M., Harland, K. K., & Saftlas, A. (2018). Stability and change in types of intimate partner violence across pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, and the postpartum period. Women's Reproductive Health, 5(3), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2018.1490084

- Daniels, K., Ahrens, K., & Pazol, K. (2020). Refining assessment of contraceptive use in the past year in relation to risk of unintended pregnancy. Contraception, 102(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.009

- Dehlendorf, C., Akers, A. Y., Borrero, S., Callegari, L. S., Cadena, D., Gomez, A. M., Hart, J., Jimenez, L., Kuppermann, M., Levy, B., Lu, M. C., Malin, K., Simpson, M., Verbiest, S., Yeung, M., & Crear-Perry, J. (2021). Evolving the preconception health framework: A call for reproductive and sexual health equity. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 137(2), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004255

- Dehlendorf, C., Rodriguez, M. I., Levy, K., Borrero, S., & Steinauer, J. (2010). Disparities in family planning. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(3), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.022

- Finer, L. B., & Henshaw, S. K. (2006). Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.38.090.06

- Frohwirth, L., Blades, N., Moore, A. M., & Wurtz, H. (2016). The complexity of multiple contraceptive method use and the anxiety that informs it: Implications for theory and practice. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2123–2135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0706-6

- Frohwirth, L., Moore, A. M., & Maniaci, R. (2013). Perceptions of susceptibility to pregnancy among U.S. women obtaining abortions. Social Science & Medicine, 99, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.010

- Frost, J. J., Lindberg, L. D., & Finer, L. B. (2012). Young adults’ contraceptive knowledge, norms and attitudes: Associations with risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 44(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1363/4410712

- Frost, J. J., Singh, S., & Finer, L. B. (2007). U.S. women’s one-year contraceptive use patterns, 2004. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1363/3904807

- Gibbs, L., Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2014). Qualities of romantic relationships and consistent condom use among dating young adults. In L. Bourgois & S. Cauchois (Eds.), Contraceptives: Predictors of use, role of cultural attitudes & practices and levels of effectiveness (pp. 157–182). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Gomez, A. M., & Wapman, M. (2017). Under (implicit) pressure: Young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception, 96(4), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.007

- Gomez, A. M., Fuentes, L., & Allina, A. (2014). Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1363/46e1614

- Grindlay, K., & Grossman, D. (2016). Prescription birth control access among U.S. women at risk of unintended pregnancy. Journal of Women's Health, 25(3), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5312

- Guttmacher Institute. (2019). Unintended pregnancy in the United States. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/unintended-pregnancy-united-states

- Guttmacher Institute. (2020). Contraceptive effectiveness in the United States. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/contraceptive-effectiveness-united-states.pdf

- Guttmacher Institute. (2021). The federal contraceptive coverage guarantee: An effective policy that should be strengthened and expanded. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/contraceptive-coverage-guarantee

- Guzman, L., Caal, S., Peterson, K., Ramos, M., & Hickman, S. (2013). The use of fertility awareness methods (FAM) among young adult Latina and black women: What do they know and how well do they use it? Use of FAM among Latina and black women in the United States. Contraception, 88(2), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.015

- Hall, K. S. (2012). The health belief model can guide modern contraceptive behavior research and practice. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 57(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00110.x

- Hatcher, R. A., Nelson, A. L., Trussell, J., Cwiak, C., Cason, P., Policar, M. S., Edelman, A., Aiken, A. R. A., Marrazzo, J., & Kowal, D. (2018). Contraceptive technology (21st ed.). Managing Contraception LLC.

- Heaton, J. (2008). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: An overview. Historical Social Research, 33(3), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.33.2008.3.33-45

- Hester, N. R., & Macrina, D. M. (1985). The health belief model and the contraceptive behavior of college women: Implications for health education. Journal of American College Health, 33(6), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.1985.9935034

- Higgins, J. A., & Wang, Y. (2015). The role of young adults’ pleasure attitudes in shaping condom use. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1329–1332. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302567

- Holt, K., Reed, R., Crear-Perry, J., Scott, C., Wulf, S., & Dehlendorf, C. (2020). Beyond same-day long-acting reversible contraceptive access: A person-centered framework for advancing high-quality, equitable contraceptive care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222(4S), S878.e1-S878–e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1279

- Jackson, A. V., Karasek, D., Dehlendorf, C., & Foster, D. G. (2016). Racial and ethnic differences in women’s preferences for features of contraceptive methods. Contraception, 93(5), 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.010

- Jerman, J., Jones, R. K., & Onda, T. (2016). Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients in 2014 and changes since 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/characteristics-us-abortion-patients-2014

- Jones, K. A., Cornelius, M. D., Silverman, J. G., Tancredi, D. J., Decker, M. R., Haggerty, C. L., De Genna, N. M., & Miller, E. (2016). Abusive experiences and young women’s sexual health outcomes: Is Condom negotiation self-efficacy a mediator?: Confidentiality of adolescent family planning in FQHCs. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 48(2), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1363/48e8616

- Jones, R. K., Lindberg, L. D., & Higgins, J. A. (2014). Pull and pray or extra protection? Contraceptive strategies involving withdrawal among US adult women. Contraception, 90(4), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.016

- Kavanaugh, M. L., & Jerman, J. (2018). Contraceptive method use in the United States: Trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception, 97(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.003

- Kavanaugh, M. L., & Pliskin, E. (2020). Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F&S Reports, 1(2), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Kavanaugh, M. L., Douglas-Hall, A., & Finn, S. M. (2020). Health insurance coverage and contraceptive use at the state level: Findings from the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Contraception: X, 2, 100014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conx.2019.100014

- Kavanaugh, M. L., Pliskin, E., & Jerman, J. (2021). Use of concurrent multiple methods of contraception in the United States, 2008 to 2015. Contraception: X, 3, 100060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conx.2021.100060

- Kavanaugh, M. L., Kost, K., Frohwirth, L., Maddow-Zimet, I., & Gor, V. (2017). Parents' experience of unintended childbearing: A qualitative study of factors that mitigate or exacerbate effects. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.024

- Kaye, K., Suellentrop, K., & Sloup, C. (2009). The Fog Zone: How misinterpretations, magical thinking and amibvalence put young adults at risk for unplanned pregnancy. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. https://powertodecide.org/sites/default/files/resources/primary-download/fog-zone-full.pdf

- Lansky, A., Thomas, J. C., & Earp, J. A. (1998). Partner-specific sexual behaviors among persons with both main and other partners. Family Planning Perspectives, 30(2), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991666

- Lawley, M. E., Cwiak, C., Cordes, S., Ward, M., & Hall, K. S. (2022). Barriers to family planning among women with severe mental illness. Women’s Reproductive Health, 9(2), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2021.2016139

- Long-Sutehall, T., Sque, M., & Addington-Hall, J. (2011). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: A valuable method for exploring sensitive issues with an elusive population? Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987110381553

- Macaluso, M., Demand, M. J., Artz, L. M., & Hook, E. W. (2000). Partner type and condom use. AIDS, 14(5), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200003310-00009

- McGovern, L. (2014, August 21). The relative contribution of multiple determinants to health. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20140821.404487/full/

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications.

- Miller, E., & Silverman, J. G. (2010). Reproductive coercion and partner violence: Implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 5(5), 511–515. https://doi.org/10.1586/eog.10.44

- Moore, A. M., Frohwirth, L., & Miller, E. (2010). Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 70(11), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009

- Moore, A. M., Frohwirth, L., & Blades, N. (2011). What women want from abortion counseling in the United States: A qualitative study of abortion patients in 2008. Social Work in Health Care, 50(6), 424–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2011.575538

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412995658

- Nettleman, M. D., Chung, H., Brewer, J., Ayoola, A., & Reed, P. L. (2007). Reasons for unprotected intercourse: Analysis of the PRAMS survey. Contraception, 75(5), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.011

- Polis, C. B., & Jones, R. K. (2018). Multiple contraceptive method use and prevalence of fertility awareness based method use in the United States, 2013–2015. Contraception, 98(3), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2018.04.013

- Polis, C. B., & Zabin, L. S. (2012). Missed conceptions or misconceptions: Perceived infertility among unmarried young adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 44(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1363/4403012

- Potter, J. E., Coleman-Minahan, K., White, K., Powers, D. A., Dillaway, C., Stevenson, A. J., Hopkins, K., & Grossman, D. (2017). Contraception after delivery among publicly insured women in Texas: Use compared with preference. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002136

- Reed, J., England, P., Littlejohn, K., Bass, B. C., & Caudillo, M. L. (2014). Consistent and inconsistent contraception among young women: Insights from qualitative interviews. Family Relations, 63(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12058

- Roderique-Davies, G., McKnight, C., Jonn, B., Faulkner, S., & Lancastle, D. (2016). Models of health behaviour predict intention to use long acting reversible contraception use. Women’s Health, 12(6), 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745505716678231

- Samankasikorn, W., Alhusen, J., Yan, G., Schminkey, D. L., & Bullock, L. (2019). Relationships of reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence to unintended pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 48(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2018.09.009

- Santelli, J. S., Kantor, L. M., Grilo, S. A., Speizer, I. S., Lindberg, L. D., Heitel, J., Schalet, A. T., Lyon, M. E., Mason-Jones, A. J., McGovern, T., Heck, C. J., Rogers, J., & Ott, M. A. (2017). Abstinence-only-until-marriage: An updated review of U.S. policies and programs and their impact. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.031

- Shedlin, M., Amastae, J., Potter, J. E., Hopkins, K., & Grossman, D. (2013). Knowledge and beliefs about reproductive anatomy and physiology among Mexican-origin women in the U.S.A: Implications for effective oral contraceptive use. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.766930

- Sonfield, A., Frost, J., Dawson, R., & Lindberg, L. D. (2020, August 3). COVID-19 job losses threaten insurance coverage and access to reproductive health care for millions | Health affairs. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20200728.779022/full/

- Sundaram, A., Vaughan, B., Kost, K., Bankole, A., Finer, L., Singh, S., & Trussell, J. (2017). Contraceptive failure in the United States: Estimates from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth: Contraceptive failure rates in the U.S. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 49(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12017

- Trussell, J. (2011). Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception, 83(5), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021

- Villavicencio, J., & Allen, R. H. (2016). Unscheduled bleeding and contraceptive choice: Increasing satisfaction and continuation rates. Open Access Journal of Contraception, 7, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S85565