Abstract

The contraceptive needs of women for whom the benefits of menstrual bleeding may outweigh its disadvantages have largely been overlooked, especially outside high-income countries. Some providers and researchers have assumed that users of nonhormonal birth control (non-HBC) are misinformed about the positive and negative effects of HBC and/or the need for menstrual bleeding. This study takes the position that many of those rejecting HBC in favor of methods that do not alter bleeding are, in fact, making informed decisions. Using questionnaire data from 4,255 contraceptive users in three countries, we compared current HBC users explicitly open to hormone use (“H-receptive”) and non-HBC users explicitly rejecting hormones (“H-averse”). To the extent that menstrual bleeding attitudes affect contraceptive choice, these two groups should have the greatest contrasts in those attitudes. This novel study design mitigates ambiguities arising from posing hypothetical scenarios to those ambivalent about using hormones or who are not currently using contraception. In all three countries, of those agreeing with the prompt, “I don’t want to change my natural menstrual cycle,” the fractions of H-averse and H-receptive users are disproportionally high and low, respectively (p ≤ .0026). Responses to other prompts varied across populations, revealing complex juxtapositions of multiple criteria, including bleeding preferences, that likely influence contraceptive choices. These patterns, reflecting personal and culturally salient values, highlight the necessity of not assuming that menstrual bleeding is undesirable or relying on a single criterion to ascertain clients’ contraceptive needs and preferences. Rather, acknowledging a client’s personal hierarchy of preferences regarding contraceptive attributes best serves their goals.

Introduction

This study addresses two significant gaps in current knowledge of the relationships between individual attitudes toward menstrual bleeding and contraceptive decision making:

The contraceptive preferences of those for whom the benefits of period bleeding may outweigh its costs have been largely overlooked. This study takes the position that many of those who eschew hormonal birth control (HBC) in favor of methods that do not change bleeding are, in fact, acting in accordance with their own best interests as they see them.

There is a relative paucity of relevant studies in populations outside North America or Europe. Our study was conducted in India, South Africa (SA), and the United States (US).

The study’s aim is to provide insight into the various aspects of menstrual bleeding that may influence an individual’s contraceptive decision making. A clearer and more nuanced understanding of these connections can inform efforts by health care providers, contraceptive developers, and researchers to better meet the array of contraceptive users’ expectations and needs.

Several large survey and smaller scale studies (in various countries but predominantly in Europe and North America) have reported that a large segment of study participants have negative views and experiences of menstrual bleeding (D’Souza et al., Citation2022; Fiala et al., Citation2017; Nappi et al., Citation2016; Polis et al., Citation2018; Szarewski & Moeller, Citation2013; Szarewski et al., Citation2012). Yet many of the same participants who expressed a desire to reduce period frequency, bleeding, and/or symptoms did not use HBC, despite its availability, to modify their periods. This seeming incongruity has raised the question, “What prevents most from doing so?” (Nappi et al., Citation2016; Szarewski et al., Citation2012). For the most part, investigators have proposed that ignorance about HBC options, or misconceptions about the necessity of menstrual bleeding and/or the dangers of hormones, have kept many womenFootnote1 from using HBC to modify their cycles.

Though these explanations may apply to some persons, it is also plausible that some consider menstrual bleeding to be beneficial even if bothersome (Newton & Hoggart, Citation2015). We suggest they may be willingly balancing various preferences and see a net gain in the trade-off between maintaining menstrual bleeding versus dispensing with its inconvenience. For example, in Europe and the Americas, views of healthiness that encourage more “natural lifestyles” tend to favor nonhormonal contraceptive methods that do not interfere with menstrual bleeding or other bodily functions (Le Guen et al., Citation2021). Also, for many women worldwide, menses is a cost-free conception monitor.

Most studies, especially large-scale surveys, have not been designed to detect and evaluate such nuances in how persons view and manage their menstrual bleeding. In some cases, study designs may have unintentionally introduced selection bias, hampering a better understanding of participants’ reasons for their decisions. For example, persons who stated that they would never use HBC have been excluded in some studies. Such exclusion undermines sample representativeness and casts doubt on claims that “most women” share some opinion or another. In addition, a common survey method (which we also used in this study) is to ask respondents to express their level of agreement/disagreement with a set of positive and negative statements (prompts) about menstrual bleeding. In studies in which only negative prompts about bleeding are presented to respondents, it can be difficult to ascertain whether there are favorable attitudes about bleeding that may influence contraceptive decisions. We avoided this problem by providing a mixture of negative and positive prompts about menstrual bleeding.

The construction of analytical samples may also preclude recognizing subtle but important distinctions in attitudes toward bleeding. Some analytical samples are composites of different states (e.g., persons using a non-HBC are combined with persons not using any contraception), and some analytical samples comprise both actual and hypothesized states (e.g., those who have ever or are currently using HBC are combined with those who are not currently using but say they would use HBC). In either case, unrecognized heterogeneity in the sample may confound interpretations of the data.

Individual attitudes toward menstrual bleeding are complex and sometimes even contradictory, perhaps no more so than when choosing a contraceptive. Untangling these intricacies is challenging and is particularly difficult using study designs that present hypothetical scenarios and ask study participants for their opinions or predictions. Although this is a fairly common approach in studies of contraceptive preferences and other aspects of human behavior, research on the “hypothetical bias effect” (the difference between what people say they will do and what they actually do) has revealed the inherent limits of such study designs (Tanner & Carlson, Citation2009).

The analytical samples in our study comprised current hormonal birth control users who explicitly expressed openness to using HBC (“H-receptive”) and current non-HBC users who explicitly expressed opposition to using HBC (“H-averse”). Each sample comprised only those respondents who were currently using a contraceptive method that aligned with their stated receptivity or aversion to using hormonal methods. In effect, these respondents are demonstrating, by their current behavior, the strength of their expressed opinion regarding the use of HBC. This novel study design mitigates the ambiguities that may arise in studies posing hypothetical scenarios, particularly when such questions are posed to persons who are ambivalent about using hormones or who are not currently using any contraceptive method.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to compare the responses from analytical groups of persons whose current method use aligns with their explicitly stated receptivity/aversion to the use of hormones. Insofar as menstrual bleeding attitudes affect contraceptive choice, these two groups would be expected to have the greatest contrasts in those attitudes. On the other hand, in a given population, if these two analytical groups do not differ in their bleeding attitudes, it suggests that opinions and experiences regarding menstrual bleeding may not be major predictors of contraceptive choice in that population.

Materials and Methods

Data were collected via questionnaire in three countries (India, SA, US) as part of a larger investigation of various aspects of reproductive health (Shea, Thornburg, & Vitzthum, Citation2023). These countries were selected because they represent three distinct global regions and have different population profiles of contraceptive use. Also, the selected mobile app to be used for data collection already had a sufficiently large user base in each country such that, given typical user click-through rates for app-based surveys, an adequate sample size for the intended analyses was likely to be achieved.

The questionnaire was distributed via a mobile menstrual health tracking application (Clue by Biowink GmbH) (https://helloclue.com/) that has been used successfully in several other scientific research studies (Alvergne et al., Citation2018; Gesselman et al., Citation2020; Graham et al., Citation2020; Shea, Wever, et al., Citation2023). Prior to study implementation, the questionnaire was first extensively tested in US English and Spanish speakers for comprehension and ease of completion using a mobile device. Evaluation methods included in-person and virtual user tests and a final round of unguided tests through the online testing platform, UserTesting (Teston Germany GmBH, Citationn.d.). Subsequent user testing in SA and India was conducted under the direct guidance of in-country experienced research consultants. The country-specific questionnaires were extensively tested for local suitability (e.g., ethnicity categories) and comprehension (e.g., locally colloquial language for types of contraceptives and for attitudes regarding menstrual bleeding).

Recruitment was via an in-app message (i.e., an invitation to participate in the study with a link to the online questionnaire) sent to the app’s users in the three countries. Depending on the locale and language of the participant’s app settings, the country-specific questionnaire was in either English or Spanish (the second most spoken language in the US; US Census Bureau, Citation2022a). Although Hindi is one of the almost 20 languages available on the Clue app, all but a handful of Indian Clue users had set their app to English, the most spoken second language in India (Joseph, Citation2011; Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India, Citation1967). All SA Clue users had set their apps to English, which is one of 11 government-recognized languages (Mesthrie, Citation2006). Data were collected between November 12, 2020, and February 17, 2021.

Questionnaire sections relevant to the analyses presented here are study eligibility, current and prior contraceptive use, and menstrual bleeding attitudes (details given below). Respondents were also asked, “Why did you choose the method you relied on most?” and provided with a list of 24 options from which they could choose any or all options. Sociodemographic variables included age, education, community type (suburban, urban, rural), ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship status, parity, and the question, “Do you want (more) children in the future? (If pregnant, after your current pregnancy)” with response options “yes,” “not sure,” “no” (and not answered).

Data analysis used custom-developed software written in Perl (https://www.perl.org) (v5.32.1 and v5.36.0) and an online calculator hosted by Social Science Statistics (https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/chisquare2/default2.aspx).

Inclusion Criteria

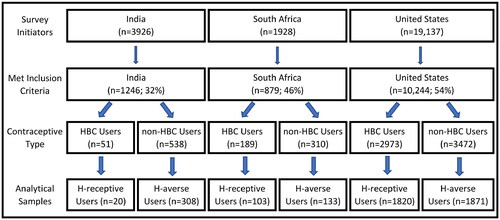

depicts the construction of analytical samples for each country. For inclusion in the present analyses, each respondent had to meet all of the following five criteria:

Figure 1. The construction of analytical samples for each country (see Materials and Methods for additional details). Of survey initiators, 32% (India), 46% (SA), and 54% (US) met the inclusion criteria. Eligible respondents were those currently using one of the specified HBC methods or using a non-HBC method. Of the eligible HBC users, those responding, “I would use hormonal birth control” were classified as H-receptive users, and of the eligible non-HBC users, those responding, “I don’t want to use any method of hormonal birth control” were classified as H-averse users.

Actively submitted their questionnaire (did not drop out before the final question).

Affirmatively stated “I took the survey seriously.”

Stated their age as between 18 and 45 years old (inclusive).

Stated that they lived in India, SA, or the US.

Reported the contraceptive method they had used most during the past 3 months.

Analytical Groups

Of those meeting the inclusion criteria, respondents were categorized as HBC users if their primary method for the past 3 months contained hormones that could influence bleeding patterns (i.e., injection, implant, hormonal intrauterine device [IUD], birth control pill, contraceptive patch, and vaginal contraceptive ring) or non-HBC users if their primary method was hormone-free and did not affect bleeding patterns (i.e., condom, fertility awareness method, diaphragm, and withdrawal). Respondents who relied primarily on female or male sterilization, copper IUDs, emergency contraception, lactational amenorrhea, or other unstated methods were excluded from these two analytical samples because their inclusion might bias the study outcomes (e.g., the copper IUD is a nonhormonal method that can influence menstrual bleeding patterns).

Respondents were asked, “How do you feel about using birth control that contains hormones (such as the pill, implant, injection, hormonal IUD)?” and selected one of the following four answers: “I would use hormonal birth control,” “I currently am or would use hormonal birth control, but I would prefer not to,” “I don’t want to use any method of hormonal birth control,” or “I’m not sure.” “H-receptive” users were defined as those HBC users who selected “I would use hormonal birth control,” and “H-averse” users were defined as those non-HBC users who responded, “I don’t want to use any method of hormonal birth control.” Thus, each of these two analytical samples comprised only those respondents who were currently using a contraceptive method that aligned with their stated receptivity or aversion to using hormonal methods (respondents who expressed ambivalence about the use of hormones were not included in either analytical sample).

Questions on Bleeding Attitudes

Bleeding attitudes were explored through a series of statements about the respondents’ experiences and preferences regarding menstruation. For each prompt (listed below), respondents indicated their degree of agreement/disagreement on a 5-point Likert scale from these options:

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Strongly disagree

The counts of (a) and (b) responses were grouped together and designated as “agreed” with the prompt. Likewise, the counts of (d) and (e) were grouped together and designated as “disagreed” with the prompt. Response (c) was designated as “neutral.”

All respondents were presented, in the order given below, with the following prompts:

“I need to have periods to be in good health.”

“The only thing my period is good for is to let me if know I’m pregnant.”

“I don’t want to change my natural menstrual cycle.”

“I feel empowered by my periods.”

“I wish I could take a break from having my period.”

“My period helps me keep in touch with my body.”

“My period represents fertility and potential motherhood.”

“I need to have periods because they cleanse my body.”

“My life is worse when I am on my period.”

“My period is an important part of my gender identity.”

“It is difficult to manage my period bleeding.”

“It is difficult to manage my period-related symptoms (such as cramps or mood changes).”

Respondents were also asked, “How often would you like to have your period?” Response options were:

Regular periods

Regular periods but being able to skip them sometimes.

Never having a period.

Not having periods except when I want to become pregnant.

For the US and SA samples, we used a 2 × 2 chi-square test (α = .05, two-sided) to evaluate statistical association between each pair of H-receptive/H-averse (HR/HA) groups and agree/disagree responses to the prompts on bleeding attitudes. Specifically, for each prompt, the query takes the form, “Is the fraction of H-receptive users among those agreeing with the prompt (HR agree/total agree) different from the fraction of H-receptive users among those disagreeing with the prompt (HR disagree/total disagree)?” If the fractions are significantly different, then the null hypothesis is rejected (i.e., the specific bleeding attitude is shown to be a significant factor in contraceptive choice). Note that one could equally well pose these comparisons in terms of the fractions who are HA. Because HR + HA = 100% of our sample, posing the comparisons in terms of fractions who are HA would give identical results to those presented here. For example, if the result of a comparison is “of those agreeing with a prompt, the fraction of H-receptive is disproportionally low,” we could equally say that “the fraction of H-averse is disproportionally high.” Note also that the results of a chi-square test, which is a test of association, are the same regardless of whether the numerical data are arranged in rows or columns.

In India, because of the small sample size, we evaluated the association between H-receptive/H-averse and agree/other, where other equaled the sum of disagree and neutral responses. In each of the three country samples, we evaluated the association between HR/HA and regular/other period frequency (where other equals the sum of the three alternative bleeding options: choices b, c, and d listed above).

Results

Sample Characteristics

United States

US H-receptive users comprised 718 using a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method (injection, implant, hormonal IUD), and 1,102 using a non-LARC method (birth control pill, contraceptive patch, vaginal contraceptive ring).

H-receptive users were younger than H-averse users () and, consistent with this age difference, fewer had ever married or had any children. Marital status of each sample was consistent with that of the US population: at ages 25 years and 29 years, 68% and 45% respectively of US women have not yet married (Yau, Citation2017). For their ages, these two study samples have fewer children than the general population of US women: at ages 25 years and 29 years, about 55% and 37%, respectively, of US women have no children (Yau, Citation2019). The smaller number of children in these analytical samples is likely largely attributable to their use of contraception. Education level, household income, and community type were similar in the two analytical groups. Ethnicity composition in both analytical samples was also similar to that of the US population (Shea, Thornburg, & Vitzthum, Citation2023; US Census Bureau, Citation2022b).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of US H-receptive and H-averse respondents.

Of the combined US sample of H-receptive and H-averse users, 95% identified as woman and 3.5% as queer/non-binary. Reported sexual orientation was 71% straight, 25% bisexual/pansexual, 1% lesbian/gay/homosexual, and 1% asexual.

India

Indian H-receptive users comprised 1 using a LARC method (injection, implant, hormonal IUD) and 19 using a non-LARC method (birth control pill, contraceptive patch, vaginal contraceptive ring).

H-receptive users were younger than H-averse users () and, consistent with this age difference, fewer had ever married. Nonetheless, similar percentages of the two user groups reported not having any children. Compared to H-receptive, H-averse users were more likely to report wanting more children and much less likely to report not wanting more children. Education level, ethnicity composition, and community type were similar in the two analytical groups; household incomes in both groups spanned the five-category income range but are only roughly similar due to the small number of H-receptive users. Compared to national demographics (International Institute for Population Sciences & ICF, Citation2022; Shea, Thornburg, & Vitzthum, Citation2023), this study sample overrepresented the younger, higher educated, urban/suburban population. The sample also underrepresented Scheduled Caste (SC) and Other Backward Class (OBC), which are a majority of the population (Sahgal et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of India H-receptive and H-averse respondents.

Of the combined Indian sample of H-receptive and H-averse users, 98% identified as woman. Reported sexual orientation was 92% straight and 6% bisexual/pansexual.

South Africa

SA H-receptive users comprised 21 using a LARC method (injection, implant, hormonal IUD) and 82 using a non-LARC method (birth control pill, contraceptive patch, vaginal contraceptive ring).

H-receptive users were younger than H-averse users (), had a lower marriage rate, and were 11% more likely (p ≤ .05) to not have had children. Compared to H-receptive, H-averse users were less likely to report wanting more children and 1.5 times more likely to report not wanting more children. Education level, household income, ethnicity composition, and community type were similar in the two analytical groups. Compared to national demographics (National Department of Health et al., Citation2019; Shea, Thornburg, & Vitzthum, Citation2023), this study sample overrepresented the younger, higher educated, urban/suburban population.

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of SA H-receptive and H-averse respondents.

Of the combined SA sample of H-receptive and H-averse users, 99% identified as woman. Reported sexual orientation was 83% straight and 15% bisexual/pansexual.

H-Receptive Versus H-Averse Responses to Prompts

Maintaining the Natural Cycle Versus Reducing Bleeding Frequency

In all three countries (), of all prompts posed to respondents, “I don’t want to change my natural cycle” (prompt A) elicited the highest agreement from H-averse users (India: 96%, SA: 72%, US: 77%). In the US and SA, this same prompt elicited the lowest agreement of all prompts from H-receptive users (India: 4.3%, SA: 28%, US: 23%). The association between H-receptive/H-averse and agree/disagree on not changing their natural cycle was significant at p < .0001 in SA and the US and at p < .0026 in India. However, other than these similar responses to this specific prompt, response patterns to the other prompts differed across the three countries.

Table 4. India.

Table 5. South Africa.

Table 6. United States.

In SA and the US (but not in India), a majority of the samples agreed with, “I wish I could take a break from having my period” (prompt B). In SA and India, the fractions of H-receptive users did not differ significantly between those who agreed and those who disagreed with the prompt. In the US sample, the fraction of HR was disproportionally high (p < .001) among those agreeing with the prompt (58%) compared to the fraction of HR among those disagreeing with the prompt (29%).

In every country, H-averse users preferred to have regular periods as opposed to other options (prompt N): India (234/308, 76%), SA (82/133, 62%), US (1,132/1,871, 61%). About half of H-receptive users in India (11/20, 61%) and SA (47/103, 46%) also preferred to have regular periods. In the US, only 28% (513/1,820) of H-receptive users preferred to have regular periods as opposed to other options.

Periods, Fertility, and Pregnancy

Majorities in all three countries agreed that “my period represents fertility and potential motherhood” (prompt H). Nonetheless, in India and SA, the fractions of H-receptive users did not differ significantly between those agreeing and those disagreeing with the prompt. In the US, the fraction of H-averse users was significantly higher (p < .0001) among those agreeing with the prompt (61%) than among those disagreeing (34%).

In the US (p < .0001) and India (p = .03), those agreeing that “the only thing my period is good for is to let me know if I’m pregnant” (prompt C) were disproportionally H-receptive; those disagreeing were disproportionally H-averse. In SA the relative proportions of HR and HA did not differ by agree/disagree responses to this prompt.

Periods and Health

Majorities in India and SA agreed that “I need to have periods to be in good health” (prompt F), but the relative proportions of HR and HA did not differ by agree/disagree. In contrast, only 42% of the US respondents agreed with this prompt but, of those agreeing, there was a disproportionally higher fraction of H-averse users (p < .0001).

Likewise, only a minority (32%) of the US sample agreed that “I need to have periods because they cleanse my body” (prompt J) and, of these, there was a disproportionally higher (p < .0001) fraction of H-averse users. In India, a majority agreed with the prompt, but there was no significant association with H-averse versus H-receptive (which may be attributable to the small sample size). In SA, neither a majority agreed with the prompt, nor was there a significant association between HR/HA groups and agree/disagree groups.

Majorities in all three countries agreed that “my period helps me keep in touch with my body” (prompt G). Of those in the US and SA agreeing, the fraction of H-averse users was disproportionally high (US: p < .0001, SA: p = .003). In India, agreement was not associated with HR/HA groups.

Periods and Psychosocial Health

“My period is an important part of my gender identity” (prompt D) was not a majority opinion in any of the three countries and was not significantly associated with H-receptive/H-averse in either India or SA. In the US, however, the fraction of H-averse users was disproportionally high in those agreeing with this prompt (p < .0001).

A slim majority of Indian respondents agreed with the statement, “I feel empowered by my periods” (prompt E), but there was no association with HR/HA groups. Only minorities of SA and US respondents agreed with this prompt. However, association with HR/HA groups was significant in the US (p < .0001): those agreeing with the prompt were disproportionally H-averse.

Period-Associated Problems

Only a minority in each country agreed that “it is difficult to manage my period bleeding” (prompt K). Nonetheless, of those in the US who agreed with this prompt, there was a disproportionally high fraction of H-averse users (p < .0001). In India and SA there was no association between HR/HA groups and agree/disagree responses for this prompt.

In each of the three countries, two-thirds majorities of the H-receptive and H-averse samples agreed that “it is difficult to manage my period-related symptoms” (prompt L). However, there were no significant associations between agree/disagree and HR/HA groups in any of these samples. (Note that some of the H-receptive users who agreed with this prompt may be referring to period-related problems experienced before they adopted HBC rather than, or in addition to, any problems they are currently experiencing.)

Reasons for Choosing Contraceptive Method

The reasons for selecting a method and the counts in each country are listed in .

Table 7. Responses to the question, “Why did you choose the method you relied on most?” (select all that apply).

The top reasons for choosing HBC given by H-receptive users in all three countries included “It is easy to use,” “I can stop using it whenever I want,” and “It makes my period more predictable (comes at the same time every month).” Half or more of H-receptive users in SA and the US selected, “It decreases bleeding during my period” and “My health care provider recommended it”; in India, fewer than half selected either reason.

The most commonly reported reasons given by H-averse users for selecting a non-HBC method included (all reasons listed here were selected by at least 50% of respondents in at least one of the three countries): lack of side effects, lack of hormones, easy to use, easy to buy/get, noninvasive, does not impact fertility, and no need for a prescription.

Discussion

The goal of this study is to enhance health care providers’ ability to meet clients’ health needs and contraceptive preferences. Our specific objective is to expand and clarify understanding of current contraceptive users’ experiences and opinions of menstrual bleeding and how these factors may relate to a user’s selection of a contraceptive. Although contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes per se are recognized as an important consideration in contraceptive decision making, insufficient attention has been given to the breadth of user beliefs and concerns about periods that may (consciously or unconsciously) inform a user’s contraceptive choice (Le Guen et al., Citation2021; Polis et al., Citation2018). Moreover, most studies have been in European and North American countries, which represent only a minority of the human population who desire effective and safe contraception that meets their diverse needs.

Below we first discuss the country-specific patterns that emerged from analyses of the questionnaire data and the possible reasons for those patterns. We then consider the implications of these findings for contraceptive counseling and for research on user needs, providers’ assumptions, and contraceptive methods more broadly. We also examine the advantages and limitations of our study and how these may be improved upon in future work.

Country Profiles

India

Reflecting the low national level of HBC use in India (International Institute for Population Sciences & ICF, Citation2022; Kapasia et al., Citation2022), the use of HBC in our study sample was also low (only 8% of those specifying a method). Moreover, only 39% of these HBC users explicitly expressed agreement with using HBC (i.e., were classified as H-receptive; ).

A reluctance to use HBC is consistent with the Indian respondents’ attitudes toward menses. Most, including large majorities of both H-receptive and H-averse users, did not want to change their natural cycle (, prompt A) and wanted regular periods (prompt N) even though a large fraction (80% of HR, 60% of HA) found it difficult to manage their period-related symptoms (prompt L). Such high rates of impaired menstrual health are consistent with the findings of several studies in India (Anand et al., Citation2018).

Majorities of H-averse users agreed with various prompts (E, F, G, H, J) that express the benefits of menstrual bleeding. Of these same prompts, at least half of H-receptive users agreed with prompts E, F, G, and H. Particularly notable are the large majorities of both groups (85% of HR, 83% of HA) that agreed, “I need to have periods to be in good health” (prompt F).

Somewhat counterintuitively, a majority of H-receptive users did not want to change their natural cycle yet had chosen to use HBC and were open to using HBC in the future. An examination of their specific HBC choices may explain this seeming paradox. Of the 20 H-receptive respondents, 12 did not want to change their natural cycle. Of these, only 1 was using a LARC and 11 were using the pill. This suggests that at least some, perhaps all, of these 11 do not distinguish menstrual from withdrawal bleeding. Although some may not recognize this difference, it is also likely that some consider both types of bleeding to be functionally equivalent as regards health benefits and as a signal of pregnancy (similar views have been reported by US and English women; DeMaria et al., Citation2019; Newton & Hoggart, Citation2015). This interpretation of the responses is consistent with the findings that 85% (17/20) of Indian HR users agree that periods are necessary for good health (, prompt F) and that 55% of Indian HR users chose their method because, among other reasons, “it makes the period more predictable” ().

Only 20% of H-receptive respondents selected their method because it decreases bleeding (), suggesting that menstrual regularity is a more salient concern for these users than bleeding per se. With foreknowledge, an Indian woman may be better able to hide her menses and avoid the imposed restrictions and extreme stigmatization meted out when bleeding (Sukumar, Citation2020).

A majority of H-receptive users (60%) agreed that “the only thing my period is good for is to let me know if I’m pregnant” (prompt C), but only 36% of H-averse users agreed with this prompt, suggesting that H-averse users likely recognize other benefits of regular natural periods (e.g., majorities of H-averse users agreed that periods are necessary for good health [prompt F] and for cleansing the body [prompt J]). None of the other prompts were significantly associated with HR/HA, suggesting that the opinions of menstrual bleeding presented to the respondents were not strong determinants of contraceptive choice in this Indian sample. The low number of H-receptive users, however, precluded observing more modest differences in opinions between H-receptive and H-averse users.

Majorities of both groups agreed with “my period represents fertility and potential motherhood” (, prompt H). H-averse users were, however, more likely to report wanting more children and much less likely to report not wanting more children than were H-receptive users (). Furthermore, half of H-averse users selected “It doesn’t affect my ability to become pregnant when I want to” as a reason for choosing their current non-HBC method (). Collectively, these response patterns suggest that the widely held (88%, 270/308) reluctance of H-averse users to change their cycle (prompt A) is principally related to concerns that hormones negatively impact their ability to conceive in the future. Such concerns appear to be less in the H-receptive group, in which the percentage of those who do not want more children is double that of H-averse users and there is a significantly (p = .037) greater preference for fewer periods (prompt N) than among H-averse users.

Overall, in these samples of women in India, periods (whether menstrual or withdrawal bleeding) are seen as necessary for good health (prompt F), representing fertility (prompt H), and facilitating staying in touch with one’s body (prompt G). Majorities did not report difficulties managing their menstrual bleeding (prompt K) but do (or did) have difficulties managing their period-related symptoms (prompt L). Majorities of H-averse users also see psychosocial benefits (prompts D and E) from their period. Only minorities of both groups thought that periods made their lives worse (prompt M). Maintaining regular bleeding is highly preferred (prompt N), ostensibly because bleeding signals not having conceived (especially among H-receptive users) and at the same time also signals (especially among H-averse users) that future fertility is not impaired.

South Africa

SA has a very different national contraceptive use profile than either India or the US. About half of the women aged 15 to 49 are currently using a modern contraceptive method (National Department of Health et al., Citation2019). Of these, more than half are using a hormonal method, principally 2- and 3-month injectables and the pill.

Yet there were very few significant differences between SA HR/HA groups in their responses to the prompts on menstrual bleeding (). Specifically, SA H-averse users were significantly more likely than H-receptive users not to want to change their cycle (prompt A), to prefer regular cycles over other options (prompt N), and to agree that “my period helps me keep in touch with my body” (prompt G).

Many H-receptive respondents also did not want to change their natural cycle (prompt A). However, of the 42 HR users agreeing with this prompt, 3 relied on 2- or 3-month injectables, 6 had hormonal IUD/implants, and 33 were using the pill. As with the Indian sample, at least some of the pill users may not distinguish menstrual from withdrawal bleeding and/or they see these different types of bleeding as functionally equivalent. In SA and elsewhere, regular menstruation is commonly believed to cleanse the body of “dirty” blood. Amenorrhea is seen as blood that is “blocked” inside the body, which could have negative consequences (e.g., infertility, a “tired womb,” harboring HIV; Glasier et al., Citation2003; Laher et al., Citation2010; Padmanabhanunni & Fennie, Citation2017; Polis et al., Citation2018). Withdrawal bleeding may also be perceived by SA H-receptive users as achieving the needed cleansing that is provided by menses, particularly if bleeding reliably occurs each month. This inference is consistent with the findings that 52% (54/103) of SA HR agree that periods are necessary for good health (prompt F) and that 65% of SA HR users chose their method because, among other reasons, “it makes the period more predictable” ().

Predictability may also be helpful to SA women seeking to conceal menses to avoid curtailment of their activities (e.g., participating in religious activities; Padmanabhanunni et al., Citation2018) and pervasive stigmatization. Focus group discussions with young men in a small city in southeastern SA revealed their denigration of menstruating women (who are seen as out of control, dirty, disgusting) and elevation of non-menstruating women (who meet ideals of femininity and are also sexually available; Macleod et al., Citation2023). These men often distanced themselves not only from talk about menstruation but also knowledge of it to retain their position in a gendered hierarchy.

Although there were no significant associations between agree/disagree and H-receptive/H-averse users in the responses to nearly all prompts on menstrual bleeding, majorities of the combined sample of HR/HA agreed with prompt F (I need to have periods to be in good health), prompt H (My period represents fertility and potential motherhood), and prompt L (It is difficult to manage my period-related symptoms). These response patterns suggest wide agreement, regardless of contraceptive preferences, on the necessity and costs of periods. H-receptive users were more likely to want additional children than H-averse users, but the difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that HR users are not concerned that hormones may affect future fertility.

The main reasons H-averse users chose their nonhormonal method () were “doesn’t have side effects,” “doesn’t have hormones,” “is easy to use,” “is not invasive,” and doesn’t negatively impact fertility. The top reasons H-receptive chose their HBC method were “makes my period more predictable,” “health care provider recommended it,” “can stop using it whenever I want,” “is easy to use,” and “it decreases bleeding.”

Collectively, these findings suggest that in this sample of SA H-receptive users, openness to using HBC is motivated in part by a desire to control the regularity and lessen the volume of bleeding. Aversion to the use of HBC reflects, at least in part, a desire not to change the occurrence and frequency of menstrual bleeding. Whether H-averse or H-receptive, these users are logically choosing the method type that meets their respective goals as regards menstrual bleeding.

HR and HA do not appear to differ significantly in their views of the benefits and costs of menstrual bleeding, which suggests that there are other reasons for the differences in their contraceptive preferences. It is notable that 76% of H-averse users reported choosing a non-HBC method because of a concern with hormone-associated side effects (however, this concern may not have been the primary reason for their decision). Side effects are a widely expressed reason for HBC discontinuation in many countries (Alvergne et al., Citation2017; R. Stevens et al., Citation2022; Vitzthum & Ringheim, Citation2005; Watt Rothschild et al., Citation2022). Although there has been a tendency to dismiss the issue of HBC side effects in some circles, these concerns are in need of much more investigation (R. Stevens et al., Citation2023).

United States

In the US, about 65% of women aged 15 to 49 years old are using contraception; 26% are using HBC, and about 10% use LARCs (National Center for Health Statistics, Citation2018).

In the US samples, those who agreed with prompts expressing a possible benefit from menstrual bleeding (, prompts A, D, E, F, G, H, J) were disproportionally H-averse users (p < .0001 in each case). Likewise, prompts reflecting the disadvantages of bleeding (prompts B, C, and M) had disproportionally high agreement from HR users and disproportionally low agreement from HA users (p < .0001 in each case). In addition, those who agreed with prompts reflecting the disadvantages of bleeding (prompts B, C, and M) were disproportionally H-receptive users (p < .0001 in each case).

Consistent with the H-receptive majority opinion that the only use for a period is as a signal of not conceiving, a majority of HR reported that life is worse when having their period (prompt M) and only minorities of HR connected periods to good health (prompt F). A preponderance of negative views of menses has been reported by many studies in the US and other European and European-descendant (EED) populations (Fahs, Citation2020; Ryan et al., Citation2020) even though these countries ostensibly lack any formal system that constrains activities while menstruating. Nonetheless, negative messaging of the menstruating body is pervasively communicated through various media and the medicalization of otherwise natural and healthy cyclical changes in the female reproductive system (Harris & Vitzthum, Citation2013). A growing body of evidence suggests that these cultural cues contribute to menstrual and body shaming that may be embodied as premenstrual distress (Ryan et al., Citation2020).

In contrast to H-receptive users and consistent with the H-averse majority opinion that the period is more than a “pregnancy test,” majorities of HA respondents reported positive connections between menstruation and good health (prompt F), body awareness (prompt G), and future fertility (prompt H). US HR and HA did not differ in their desire to have more children (half of respondents in each group) or in their desire to not have more children (a quarter of each group), indicating that in contrast to India, but similar to SA, most individuals in the US did not connect hormone use with future fertility.

Significant majorities of US H-averse users did not want to change their natural cycle (prompt A, 70%) and preferred “regular periods” (prompt N, 61%). The intersection of the responses to these two statements reinforces the importance to US H-averse users of maintaining natural cycling (); 51% (946/1,871) of H-averse users did not want to change their natural cycle and wanted regular periods. Nonetheless, 30% (280/946) of this segment of H-averse users still wanted to take a break from their period (prompt B). Furthermore, of those H-averse users who did not want to change their natural cycle, 27% (358/1,305) wanted fewer periods, and 81% (291/358) of this group wanted to take a break from menstrual bleeding (). These seemingly incompatible perspectives are considered further in the section, Preference Hierarchies and Trade-Offs.

Figure 2. Intersections of the responses by US H-averse respondents (n = 1871) and US H-receptive respondents (n = 1817) to three prompts: A, “I don’t want to change my natural menstrual cycle”; B, “I wish I could take a break from having my period”; N, “How often would you like to have your period?”. Findings for prompt A depicted in headers at top, and for B and N in stacked bars (from left to right). (a) 70% (1305/1871) of H-averse respondents did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle; of these, 72% (946) wanted regular cycles (sum of green bars); of these, 30% (280/946, dark green bar) wanted to take a break from their cycle. The remaining 358 respondents who didn’t want to change their natural cycle (sum of yellow bars), wanted fewer periods; of these, 81% (291/358) wanted to take a break from their cycle (dark yellow bar). In total, 44% [(291+280)/1305] of H-averse respondents who did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle still wanted to take a break from their cycle. (b) 30% (566/1871) of H-averse users were not opposed to changing their cycles; of these, 67% (380/566) wanted fewer periods (sum of yellow bars); 74% (332+88 = 420, sum of dark yellow and dark green bars) wanted to take a break from their periods; 33% wanted regular periods (sum of green bars). (c) 22% (397/1817) of H-receptive users did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle; of these, 58% (230) wanted regular cycles (sum of green bars); 22% (87/397, dark green bar) wanted to take a break from their cycle. The remaining 167 respondents who didn’t want to change their natural cycle (sum of yellow bars) wanted fewer periods; of these, 82% (136/167) wanted to take a break from their cycle (dark yellow bar). In total, 56% [(136+87)/397] of H-receptive respondents who did not want to change their natural cycle still wanted to take a break from their cycle. (d) 78% (1420/1817) of H-receptive users were not opposed to changing their cycles; of these, 80% (1137/1420) wanted fewer periods (sum of yellow bars); 82% (1016+142 = 1158, sum of dark yellow and dark green bars) wanted to take a break from their periods); 20% wanted regular periods (sum of green bars).

![Figure 2. Intersections of the responses by US H-averse respondents (n = 1871) and US H-receptive respondents (n = 1817) to three prompts: A, “I don’t want to change my natural menstrual cycle”; B, “I wish I could take a break from having my period”; N, “How often would you like to have your period?”. Findings for prompt A depicted in headers at top, and for B and N in stacked bars (from left to right). (a) 70% (1305/1871) of H-averse respondents did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle; of these, 72% (946) wanted regular cycles (sum of green bars); of these, 30% (280/946, dark green bar) wanted to take a break from their cycle. The remaining 358 respondents who didn’t want to change their natural cycle (sum of yellow bars), wanted fewer periods; of these, 81% (291/358) wanted to take a break from their cycle (dark yellow bar). In total, 44% [(291+280)/1305] of H-averse respondents who did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle still wanted to take a break from their cycle. (b) 30% (566/1871) of H-averse users were not opposed to changing their cycles; of these, 67% (380/566) wanted fewer periods (sum of yellow bars); 74% (332+88 = 420, sum of dark yellow and dark green bars) wanted to take a break from their periods; 33% wanted regular periods (sum of green bars). (c) 22% (397/1817) of H-receptive users did not want to change their natural menstrual cycle; of these, 58% (230) wanted regular cycles (sum of green bars); 22% (87/397, dark green bar) wanted to take a break from their cycle. The remaining 167 respondents who didn’t want to change their natural cycle (sum of yellow bars) wanted fewer periods; of these, 82% (136/167) wanted to take a break from their cycle (dark yellow bar). In total, 56% [(136+87)/397] of H-receptive respondents who did not want to change their natural cycle still wanted to take a break from their cycle. (d) 78% (1420/1817) of H-receptive users were not opposed to changing their cycles; of these, 80% (1137/1420) wanted fewer periods (sum of yellow bars); 82% (1016+142 = 1158, sum of dark yellow and dark green bars) wanted to take a break from their periods); 20% wanted regular periods (sum of green bars).](/cms/asset/4d8df5a4-b779-4a7f-b54d-c32dcd178ef3/uwrh_a_2267533_f0002_c.jpg)

A minority of US H-receptive users did not want to change their natural cycle (397/1,820 = 22%). Of these, 69% were using the pill (274), 22% were using hormonal IUD (58) or implants (31), and 9% were using the patch (5), ring (23), or injectables (6).

The most widely shared opinion of US H-receptive users was the desire to take a break from their period (prompt B, 76% = 1,381/1,820; , ). H-receptive users were much more likely than H-averse users (72% = 1,307/1,820 versus 39% = 739/1,871) to want alternative bleeding patterns (skipping periods or eliminating periods entirely). Even among those H-receptive users who did not want to change their natural cycle and who wanted regular cycles, 38% (87/230) wanted to take a break from menstrual bleeding.

Ease of use was the only reason for choosing their preferred contraceptive method that was cited by majorities of both US H-receptive and US H-averse users (). The most commonly reported reasons given by H-averse users for selecting non-HBC methods were lack of side effects, lack of hormones, ease of use, noninvasiveness of the method, and no need for a prescription. Lack of impact on fertility was also important to many. The reasons given by majorities of H-receptive users were ease of use, affordable, very effective at preventing pregnancy, decreases period bleeding, can stop at any time, recommended by health care provider, and makes the period more predictable.

A Bother or a Benefit? Contrasting and Shared Experiences and Perceptions of Menstruation

As noted earlier, some researchers have expressed surprise and concern that among those persons who would like to modify their period bleeding and symptoms there is a substantial fraction who have chosen not to use HBC. This seeming incongruity is all too often attributed to potential users’ “misconceptions” about HBC safety and/or the necessity of menstrual bleeding (L. M. Stevens, Citation2018; R. Stevens et al., Citation2023). Such assumptions about contraceptive users’ motivations neglect to consider the myriad sources of information and array of experiences (some contradictory) that shape an individual’s preference hierarchy, and thus decisions, regarding their own bodies.

Every culture has its own concepts of the range of “normal” (often equated with “common” and sometimes with “healthy”) human biology (Cullin et al., Citation2021). Such constructs of normalcy are shared among individuals based, to varying degrees, on daily observations of others in a community, family guidance, experience of one’s own body, stories from friends and media, and advice from authoritative persons and institutions. The measure of credence given to each of these sources varies across communities and persons.

In the arena of human female biology, there is no one unassailable model of “normal” reproductive functioning, not even within Western biomedicine (Vitzthum, Citation2020; Vitzthum et al., Citation2021). The long-standing unresolved debates on the definition, or even existence, of luteal phase deficiency exemplifies the various different perspectives in the scientific community (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Citation2015). Although such debates are a necessary part of the scientific process of generating more accurate knowledge of human biology, and ultimately better care, they may not engender confidence among clients. Along similar lines, noting the diverse views on the necessity of monthly bleeding in current and potential contraceptive users, Polis et al. (Citation2018) cautioned providers to “be aware that some individuals may be skeptical about medical advice regarding what is ‘safe’ or ‘normal’”. (p. 13).

For example, in Europe and North America, there are contesting models of healthiness that differentially focus attention on the bother or the benefits of menstrual bleeding. On the one hand, some favor a lifestyle unfettered by menstruation. Contraceptive-induced changes, such as decreased menstrual bleeding, greater period predictability, and even amenorrhea, are seen as acceptable or even desirable (Fiala et al., Citation2017; Nappi et al., Citation2016; Polis et al., Citation2018; Szarewski et al., Citation2012). Hormonal contraceptives may thus be viewed as both a method to prevent pregnancy and an empowering opportunity to manage other aspects of health such as menstrual bleeding and some gynecological conditions. For persons not wishing to become pregnant, menstrual management (possibly including complete suppression) may represent an appealing option, particularly for those with gynecological conditions such as heavy menstrual bleeding (Lin & Barnhart, Citation2007; Shea, Wever, et al., Citation2023; Uhm & Perriera, Citation2014).

On the other hand, models favoring natural lifestyles tend to value limited interference with natural bodily functions, including menstruation. Nonhormonal methods are logically more compatible with this perspective. A 2021 systematic review (Le Guen et al., Citation2021) of studies on HBC rejection in EED populations linked a growing demand for nonhormonal methods with desires for natural practices that are thought to better maintain bodily functions and avoid unwanted side effects, including altered physical and mental health, negative impacts on sexuality, and changes in menstrual bleeding. Concerns about future fertility and potential long-term health effects are also linked to the rejection of hormonal methods that may interfere with natural biology.

Consistent with these divergent perspectives, in our study, US H-averse and H-receptive users significantly differed in their responses to every prompt except “it is difficult to manage my period-related symptoms.” US H-averse users tended to have more positive associations with their periods than did H-receptive users, were more likely to associate menstruation with health and fertility, and preferred methods that do not disrupt natural menstrual cycles. US H-receptive users were more likely to view their periods as having no use other than as pregnancy signals and were more likely to prefer alternative bleeding patterns such as fewer or no periods.

Although these opinions on the utility of menstruation are often framed in terms of healthiness, historically they emerged from and reflect US political as well as medical arenas of discourse. Rather than necessarily being at odds, both health models imbue feminist and idealized American cultural values of choice and freedom (e.g., the choice to menstruate without shame or restrictions, freedom from pain and bloody clothing). In liberal New York City in the 1960s, menstrual products were typically available only at pharmacies, prewrapped by the store in plain brown paper. It was not until late in the decade that “feminist spiritualist menstrual activists” recast period stigma as period power (Bobel & Fahs, Citation2020, p. 1003) and another decade until Steinem (Citation2019) reimagined a world where men’s menstruation was glorified, bringing home the point that patriarchy, not menstruation, is the problem.

Nearly 50 years later in the US, a vast array of menstrual products are openly sold just about everywhere, although this may have as much to do with commercial shamelessness as any reduction in the shame of menstruating. Contemporary US menstruators still experience stigma, minimization of negative menstrual symptoms, inadequate health care, deficient hygiene facilities at work and in public spaces, restrictions on their activities, lost wages, and other impairments to their quality of life (Liu et al., Citation2007; Marsh et al., Citation2014; Shea, Wever, et al., Citation2023; L. M. Stevens, Citation2018). These inequitable conditions and costs (which currently include sales tax on menstrual products in 36 US states; Zraick, Citation2018) are exacerbated among those with less means and/or autonomy.

Widening access to affordable menstrual products and health care (including incarcerated, unhoused, and low-income persons), eliminating the “tampon tax,” and teaching fact-based menstrual/reproductive health classes in schools and communities are a few of the current foci of US menstrual activists (Zraick, Citation2018). Hard at work as well are reactionary efforts to eliminate, for example, reading materials, instruction, and even discussion of menstruation in public schools (Weiss-Wolf, Citation2023), a tactic that can be expected to increase the sense of shame surrounding menstrual bleeding. In some states, efforts to ban abortions and some contraceptive methods have limited menstruators’ options. These political actions intersect with inconsistent, even conflicting, medical discourse (e.g., “periods are unnecessary unless seeking to conceive” versus “regular periods are necessary to health and longevity”) to shape the environment within which US women evaluate their own menstrual experiences and make their contraceptive decisions.

The findings from the Indian and SA samples suggest somewhat different pictures of the associations between contraceptive choices and individual views of menstrual bleeding. In all three study countries, there is a significantly higher preference among H-averse users than among H-receptive users not to change their menstrual cycle. However, unlike the US sample, in India and SA there is little difference between H-averse and H-receptive groups in their opinions on the benefits or costs of menstrual bleeding. Also, the proportion of H-receptive users who do not want to change their cycle is significantly (p < .0001) higher in India (12/20 = 60%) and SA (42/103 = 41%; India and SA are not statistically different) than in the US (397/1,820 = 21%).

In India, social hierarchy (caste), patriarchy, and menstruation intersect to create multiple axes of stigmatization and exclusion (A. J. Singh, Citation2006; M. Singh, Citation2023; Sukumar, Citation2020). Menstrual taboos, embedded within Hinduism and supported by the state, help to maintain a social order predicated on male domination of inherently inferior females, who are considered too filthy during their menstrual years to enter the sacred Sabarimala temple (Manorama & Desai, Citation2020; Sukumar, Citation2020).

A review (Manorama & Desai, Citation2020) of India’s health care policies over the past 60 years revealed the scant attention given to women’s health needs other than in their roles as reproducers and child caretakers. The authors noted that although the trajectory of India’s health policies is promising, implementation falls far short of rhetoric. There continues to be little discussion of menstrual or reproductive health (and their links to women’s physical and psychosocial health) and few programs to promote more widespread knowledge of these basic health matters.

Political history and ill-conceived “population control” programs have likely also contributed to the higher rates of reluctance to use or consider using hormonal methods (Craig et al., Citation2016; Dhanraj, Citation1991). Programs in India to reduce population growth in the 1970s included enforced sterilization and injections; community exposure to those policies has been linked to a contemporary elevated hesitancy to be vaccinated (Sur, Citation2021) and may likewise be contributing to an ongoing reluctance to use any hormonal methods that require interactions with the health care system.

In SA, particularly in rural regions, contraception is highly stigmatized and considered sinful due to the influence of Christianity and/or older traditional cultural practices such as magadi-lobola (“bride price”; Malesa, Citation2022). A study of rural SA teenagers documented a high prevalence of menstrual disorders, most of which went undiagnosed and undertreated, with negative impacts on school attendance and learning (Oni & Tshitangano, Citation2015) and potentially also on their future well-being and fertility. Although HBC could help to alleviate these health problems for at least some young persons, limited resources and cultural attitudes may preclude such treatments.

In many parts of SA, postmenarcheal teenagers and adults are defined by their capacity to bear children. Even before marriage, proof of fertility may be demanded by a prospective husband before he is willing to pay magadi-lobola (Todd et al., Citation2011). As the head of household, and having paid this dowry, a husband’s preferences regarding number and timing of offspring hold sway; wives are obligated to conform. Magadi-lobola is widely practiced throughout SA, but its interpretation varies across the country’s myriad cultural subpopulations. Although not without controversy, in KwaZulu-Natal province, female virginity became desirable concurrently with rising HIV prevalence (Todd et al., Citation2011; Vincent, Citation2006), but this shift in practice does not necessarily bode a change in male hegemony. In any case, many other mutually supporting sociocultural mechanisms continue to bolster hegemonic masculinity in SA (and globally), including demeaning chatter among men about menstruating women (Macleod et al., Citation2023) and restricting certain activities (e.g., cooking, hunting) to one gender (Ratele et al., Citation2010).

Particularly in rural SA, the containment of menses is often a challenge with inadequate infrastructure and hygiene (Scorgie et al., Citation2016). Disposable products are most commonly used; there is mixed advice and capability for their disposal, mostly owing to the lack of attention paid by sanitation workers and authorities. The limited capacity of pit latrines is a serious concern; hygiene and privacy of managing menses are consequently negatively impacted. A comparative study of three schools with different economic resources (two urban—high- and low-middle-income—and one rural low-income) shed light on the challenges faced by adolescents lacking the means to adequately manage their menses (Fennie et al., Citation2023). The high-income school had enough toilets, running water, and soap and provided sanitary products if needed; facilities at the rural school were in poor condition and inadequate. Of note, only female teachers participated in this study. Invited male teachers declined, indicating discomfort with the topic, a response consistent with Macleod et al.’s (Citation2023) observation that one mechanism by which men retain their higher social status is by distancing themselves from discussions of menstruation.

High HIV prevalence adds yet another dimension to the devaluation of women’s bodies. Although the risk from vaginal sex is higher for male-to-female than female-to-male HIV transmission, the visibility of menstrual blood is a potent reminder of the possible risk to other family members (Polis et al., Citation2018). At the same time, contraceptives that suppress bleeding can be perceived as trapping HIV in the menstruator’s body (Laher et al., Citation2010; Todd et al., Citation2011), and some hormonal contraceptives may have undesirable interactions with antiretroviral therapies (Haddad et al., Citation2014; Krishna & Haddad, Citation2020). Reports of sterilization without proper consent of women with HIV (Sguazzin, Citation2020) reinforces reluctance about contraceptive methods that require interaction with the health care system or that suppress the monthly evidence of her potential fertility, especially in societies that value women only for producing children.

Preference Hierarchies and Trade-Offs: Variation in Menstrual Bleeding Preferences within US H-Receptive and H-Averse Groups

The nearly equal proportions of H-averse and H-receptive users in the US sample, and the many significant differences between these two groups in their views of menstrual bleeding, make it unequivocally evident that there is no single predominant model of the ideal contraceptive in US users’ minds. Furthermore, the diverse opinions within either the US H-receptive or H-averse group reveal interesting patterns that both reinforce the interpretations of the between-group comparisons and bring to light the nuanced complexity of users’ opinions regarding the benefits and costs of menstrual bleeding.

In , it is apparent that far more H-receptive users want to change, or are open to changing, their natural cycle (, n = 1,420), that most of these want to have fewer periods (sum of yellow bars, n = 1,137), and that almost all of these would like a break from their periods (dark yellow bar, n = 1,016). This suite of expressed preferences regarding bleeding can be met by the use of hormonal contraception but not by the use of nonhormonal methods. Although it is possible that some of these respondents have rationalized their use of HBC by claiming that the sequelae of HBC use are the effects these users desire, it is more parsimonious to infer that these desired effects on menstrual bleeding contributed to these users’ selection of a hormonal method.

A minority (22%) of US H-receptive users do not want to change their natural cycles (, n = 397). Pill use is high (69%) in this subgroup and, as appears to be the case in SA and India, at least some of these users may perceive menses and withdrawal bleeding as functionally equivalent.

Intriguingly, about 5% of H-receptive users do not want to change their natural cycles and want regular periods but also would like to take a break from their period, a combination that appears internally inconsistent and also incompatible with these respondents’ current use of, and openness to using, HBC. However, these patterns are not necessarily inconsistent if, as is likely for many people, the preferences do not all have equal weight in a user’s choice of a method. For example, it may be that, despite their preference not to change their natural cycle, these H-receptive respondents are using HBC for medical treatments or to ensure a very low risk of pregnancy, goals that take precedence over other preferences. Similarly, the wish to take a break from periods may have a low priority over other goals. A hierarchy of preferences would also explain the sizable minority (136/397 = 34%, dark yellow bar) of H-receptive users who do not want to change their natural cycle but do want fewer periods and also want to take a break from their periods.

A hierarchy of menstrual bleeding preferences may also explain some patterns observed in the sample of H-averse users. Half (946/1,871 = 51%) of these users do not want to change their natural cycles () and do want regular cycles (n = 946, sum of light and dark green bars), preferences that are consistent with their aversion to hormone use. But 30% (280/946, dark green bar) of these would like to take a break from their period, which is not achievable using non-HBC methods. Given that these users have chosen non-HBC, it is likely that maintaining natural bleeding patterns is more important to them than taking a break from bleeding. In other words, they recognize the unavoidable trade-off between these two options and are making the choice they consider to be the best for themselves.

These patterns highlight the critical necessity of evaluating multiple criteria to ascertain the contraceptive needs and preferences of a client. A suite of questions that reveals a client’s personal hierarchy of preferences regarding contraceptive attributes, and which trade-offs they are most comfortable with, is necessary to best serve the client’s goals.

Implications of Findings for Contraceptive Counseling

Menstruation is closely tied to an individual’s concerns about health and fertility in all three study countries, but the ways in which these aspects of female biology are perceived and managed vary within and between these populations, in part because of country-specific historical and contemporary sociocultural and political contexts.

Our findings suggest that there are clusters of contraceptive users in each population who have differing perspectives on the costs and benefits of menstrual bleeding and the related advantages and disadvantages of HBC. In the US, H-receptive users have a range of attitudes about changing their cycles and are more likely to view menstrual bleeding as an inconvenient bodily function with limited personal significance, which can be managed by HBC (this potential for management is likely an additional benefit of HBC for those whose primary goal is to avoid pregnancy). US H-averse users are more likely to view menstruation as an integral part of overall health and fertility, and thus its natural functioning should be preserved. This latter perspective is much more widely shared in both India and in SA, regardless of receptivity/aversion to hormones. Furthermore, hormone aversion was somewhat more common than hormone receptivity in SA (56% versus 44%) and by far the majority opinion in India (94% of our sample).

In the US and other EED populations, the acceptance of two idealized health models (one supporting a “natural lifestyle,” the other supporting a “bleeding-free lifestyle”) serves a broad range of personal preferences regarding bodily functioning. With hormonal methods, health can be maintained, and even improved, and future fertility can be concurrently protected, while also choosing whether or not to bleed (with the pill, a user can have predictable monthly bleeding, delivering the reassurance of not having conceived). For those persons favoring hormone-free options, the natural lifestyle model supports their preference to maintain and protect their health and fertility by avoiding methods that can have unwanted, even intolerable, side effects including the loss of menses. Periodic bleeding for these menstruators is a sign of healthiness, not having conceived, and future fertility; these benefits outweigh whatever bother bleeding may entail.

Alternative health models that elevate the virtues of not bleeding do not appear to be present to any significant degree in either SA or India. Advancing menstrual hygiene needs and destigmatizing menstruation are high priorities (Patkar, Citation2020). Despite stigmatization, myriad positive connections between menses and personal well-being are highly salient in both countries. These values likely contribute to the low LARC usage in the respective H-receptive samples in each.

Rather than attempting to “educate” potential users on the superior benefits of some method or another, contraceptive counseling is most effective when the client’s values are honored. The considerable focus on women’s purported and demonstrable misconceptions regarding contraception or vaginal bleeding has not yet been sufficiently matched by critical evaluations of the implicit assumptions that may underlie providers’ thinking on the links between menstruation, well-being, and contraceptive options. It is time to turn the tables.

To satisfactorily meet the contraceptive needs of a broad spectrum of clients, including those with a range of priorities regarding menstrual management, may require providers to rethink the criteria for recommending a method. For example, clients indicating that they do not want to change their natural cycle are not necessarily best served only by nonhormonal methods. If their priority is predictable bleeding, which is a top reason for choosing hormonal methods in all three study countries, a hormonal method that produces regular bleeding may be a suitable option. Meeting client goals likely requires some probing into why a person wants predictability. A provider is ethically obligated to explain the differences between withdrawal and menstrual bleeding, but some clients may be unconcerned about the physiological nonequivalence of these processes. If both types of bleeding can serve the same goals (e.g., conception status; facilitate concealment and scheduling activities, including sexual intercourse; cleansing the body; efficacious in maintaining health), some HBC and non-HBC methods may be assessed as functionally equivalent as far as the client is concerned. The client’s viewpoint is not necessarily a “misconception” that needs to be “corrected.” Rather, the client’s criterion may be one of functionality rather than physiology. The responses in our study suggest that many H-receptive respondents in the three countries see this biological technicality (withdrawal bleeding versus menses) as a distinction without a difference.

Biomedicine has its own misconceptions of the female body. Cycle length in healthy non-contraceptive-using women is known to be highly variable, both between women and between cycles of a given individual (e.g., Arey, Citation1939; Foster, Citation1889; Fraenkel, Citation1926; Harlow et al., Citation2000; Treloar et al., Citation1967). Recognizing this biological reality, the criteria for a “normal” cycle length encompass a broad range of days (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, Citation2017; Munro et al., Citation2022); however, some experts consider these criteria still too narrow (Harlow et al., Citation2000).

Women’s bodies are not clocks. Yet canonical depictions of a clock-like 28-day cycle remain ubiquitous in health providers’ offices, in textbooks and lay literature, in classrooms, and in the media—constant reminders of biomedical norms, even if such idealized cycles are not, in fact, all that common (Shea & Vitzthum, Citation2020; Vitzthum et al., Citation2021). Such messages may, consciously and unconsciously in the minds of providers and clients alike, prompt unwarranted concerns that could undermine the appropriate use of LARCs and, on the other hand, perhaps also prompt the use of non-LARC HBCs to unnecessarily regulate cycles.

In addition, reconciling seemingly contradictory messages from biomedical experts can be challenging for health care providers and clients alike. In our study samples, many respondents (42% in the US, 57% in SA, 88% in India) agreed with the prompt, “I need to have periods to be in good health,” an opinion that logically implies that they would consider most LARCs antithetical to good health. Yet, in the context of contraceptive counseling, women (even those requesting device removal) may be told that LARCs are their best option and/or that periods are unnecessary except for those who want to conceive (Brandi & Fuentes, Citation2020; DeMaria et al., Citation2019; Fiala et al., Citation2017; Gomez et al., Citation2014; Higgins et al., Citation2016). This provider stance contradicts some clients’ own opinions (and perhaps experiences) and also does not readily align, for better or worse, with the promotion, principally in the US, of the menstrual cycle as a “vital sign” (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Citation2021).

Vital signs are a small set of indicators (pulse rate, temperature, respiration rate, blood pressure) of life-sustaining bodily functions (Sapra et al., Citation2023). The healthy ranges for these vital signs are well established and do not vary greatly across humans; values outside these ranges usually indicate serious illness and/or injury. It is clear why the processes that these four vital signs reflect are essential to maintaining life. Comparably reliable ranges for a “healthy” cycle length remain to be determined; it is an open question as to what these would be and what (if any) deleterious outcomes are reliably associated with values outside these ranges, notwithstanding extreme outliers. Efforts to address this gap include statistical analyses of large data sets to probe for associations between cycle length and various diseases; a specific mechanism that might underlie any examined association is rarely proposed. Such analyses can be a useful first step, but the old maxim that “correlation does not equal causation” applies.

For example, it was recently reported that irregular and long cycles are associated with elevated mortality from external causes (e.g., accidents; Wang et al., Citation2020). Because it is implausible that such deaths are an outcome of cycle variability, it can be tempting to ignore this specific finding and concentrate on the other reported associations that are more plausible. However, the implausible finding may be an indication of a limitation in the study design (e.g., reliance on recalled adolescent cycle length that was reported from 1 to 3 decades later) that potentially undermines the study’s other findings.

These and other contested biomedical claims can be confusing, annoying, and worrisome to clients, especially if a health care provider minimizes menstrual-related symptoms, dismisses concerns regarding hormonal side effects, or exaggerates the risks of HBC even in cases where HBC is a good fit to the client’s stated contraceptive needs and preferences (D’Souza et al., Citation2022; Shea, Wever, et al., Citation2023; L. M. Stevens, Citation2018; R. Stevens et al., Citation2023). Providers would benefit themselves and clients alike by examining their own biases and being forthright about contraceptive benefits and side effects (Brandi & Fuentes, Citation2020). HBC use can have insurmountable costs for some clients. For example, there is abundant evidence that the natural concentrations of reproductive hormones (progesterone and estrogens) are variable between women within the same population and, on average, naturally lower in some non-EED populations than in EED populations (reviewed in Vitzthum, Citation2009; Vitzthum et al., Citation2004). Thus, HBC formulations designed for EED populations may produce more and more severe side effects in some women and populations (Alvergne & Stevens, Citation2021; Goldzieher, Citation1989; Vitzthum & Ringheim, Citation2005) and raise the risk for breast cancer more widely (Lovett et al., Citation2017).

Because contraceptive counseling tools (e.g., screening questionnaires) may not provide enough emphasis or detail on menstrual bleeding changes, counseling sessions should be tailored to individual client concerns and be responsive to a range of preferences (Brandi & Fuentes, Citation2020; Polis et al., Citation2018; Rademacher et al., Citation2018). Providers should not assume that menstrual bleeding is undesirable or rely on a single criterion to ascertain clients’ contraceptive needs and preferences. Rather, a suite of questions that reveals a client’s personal hierarchy of preferences regarding menstrual bleeding and the specific attributes of contraceptive options (including but not exclusively focused on contraceptive efficacy) is necessary to best serve the client’s reproductive and quality of life goals.

Meeting the needs of people in differing cultures and settings requires acknowledging both a client’s personal priorities and the diversity of those priorities within and between populations.

Advantages and Limitations of the Study