Abstract

This article describes the findings of a mixed-methods study aimed at understanding young women’s retrospective perceptions and experiences of menstrual health education in school settings in England. Data from surveys (N = 140) and eight in-depth interviews were analyzed using statistical methods and thematic analysis. Widespread inadequacies were identified in educational practices which often left participants lacking basic knowledge and feeling unprepared. While 90.0% of survey respondents reported receiving education about menstruation in school, 92.9% stated that it should have been better. Lessons typically focused on biological information and lacked practical content needed to help students manage menstruation and menstrual health, with long-term health impacts reported. Better-quality education is needed to provide sufficient knowledge and support for women to manage their menstrual health physically, emotionally and socially.

Introduction

A regular and functioning menstrual cycle is an important indicator of most women’s reproductive and holistic health, with long-term implications for physical, mental, and social well-being (Critchley et al., Citation2020). For many adolescent females, the menstrual cycle is associated with a variety of physical and mental changes such as fatigue, mood changes, and pain (Bruinvels et al., Citation2021; Critchley et al., Citation2020; Parker et al., Citation2010). For example, it is estimated that 80% to 90% of women experience physiological premenstrual symptoms (NICE, Citation2019). While the majority of these changes have only a minor impact on women’s lives and are not considered as ill health, in some cases more difficult menstrual experiences can become debilitating and indicative of underlying health issues (Motta et al., Citation2017). Menstrual health disorders are common yet often under-researched and underdiagnosed. For instance, endometriosis—a condition characterized by heavy and painful periods—affects 10% of women and takes, on average, 8 years to diagnose in the United Kingdom (APPG on Endometriosis, Citation2020). The severity and experience of symptoms for menstrual health issues varies by individual and can have far-reaching impacts on a person’s education, career, relationships, and mental health. As well as being an indicator for reproductive pathology, menstrual cycle characteristics can be indicative of wider health issues including bone and heart health and cancer (Solomon et al., Citation2002; Popat et al., Citation2008; Y.-X. Wang et al., Citation2020; S. Wang et al., Citation2022). For this reason, the menstrual cycle may be considered as “the fifth vital sign” (AAP & ACOG, Citation2006; Hillard, Citation2014). However, differentiating between normal and abnormal menstrual experiences can be difficult, especially when medical research in this area is limited and clinicians as well as patients may lack knowledge about menstrual health. We therefore suggest the importance of supporting menstrual health literacy from a young age for monitoring and managing both general and reproductive health.

Menstrual Health and Sustainable Development

In addition to the health impacts, there are many sustainable development challenges linked to menstruation, both in the United Kingdom and globally. Menstruation is regarded as a key issue for gender equality (UN Women, Citation2019; UNGA, Citation2021; Winkler & Roaf, Citation2014) and, although not mentioned explicitly in the targets, has a number of implications for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Loughnan et al., Citation2020; Sommer et al., Citation2021). For example, limited access to sanitation and resources for managing menstruation can cause girls to miss time at school or even drop out entirely (UNESCO, Citation2014; World Bank, Citation2016). This can lead to substantial socioeconomic disadvantages, by creating barriers to education or employment, as well as a greater risk of abuse and threats to health and human rights (Girls Not Brides, Citation2017; Tull, Citation2019; UNFPA, Citation2021; UNGA, Citation2021). While much of the research undertaken has been within the Global South, in the United Kingdom, at least 10% of girls are affected by period poverty (Plan International, Citation2018) and more than half have missed school due to menstruation (phs Group, Citation2019). Research shows there are long-term impacts, with over a third of girls believing they are disadvantaged compared to boys because of menstruation (phs Group, Citation2019) and 25% of women and people who menstruate feel that taking time off work because of their menstruation has impacted their career progression (Bloody Good Period, Citation2021). For a detailed overview on the numerous and complex links between menstrual health and sustainable development, refer to Sommer et al. (Citation2021).

Menstrual Health Education

Historically, there has been a lack of consensus in both the literature and public understanding in what is meant by the term “menstrual health” (Hennegan et al., Citation2021). Recognizing the need for consistent language to facilitate more unified action across policy, practice, and research, Hennegan et al. (Citation2021) developed the following definition: “Menstrual health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in relation to the menstrual cycle.” Such recent developments are representative of a rapidly growing global menstrual movement; however, public awareness about menstrual health and related disorders appears to be low. For example, research by Endometriosis UK found that 54% of people do not know what endometriosis is (increasing to 62% of women aged 16–24) (Endometriosis UK, Citation2020), despite the fact that it affects 1 in 10 women (Rogers et al., Citation2009). It may be especially challenging for young people who lack access to information or support to determine the severity of any menstrual changes or discomforts and whether medical attention should be sought. Menstrual health education could play a significant role in helping to increase awareness about the symptoms of menstrual disorders as well as what is normal, including the variety of menstrual-related changes, and empower young people to better manage their health (Haque et al., Citation2014; Randhawa et al., Citation2021; Santhanakrishnan & Athipathy, Citation2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of health-promoting schools that provide education that enables girls to manage menstruation with dignity and informs them of their sexual and reproductive rights (UN, Citation2021). School menstrual health education, which takes place at the start of a person’s reproductive life, would seem particularly pertinent.

In the United Kingdom, the topics of menstruation and menstrual health may be part of the science curricula or taught within Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) as part of Personal, Social, Health, and Economic (PSHE) education (Department for Education, Citation2020a, Citation2015). Before a recent overhaul of PSHE in 2020 (Department for Education, Citation2020b), schools were teaching RSE under guidelines from 2000 (Department for Education, Citation2000). At the time, these guidelines represented the first of their kind in the United Kingdom and were lauded as a milestone for health education (Sex Education Forum, Citation2021). However, schools were required to create their own RSE policies without obligations to deliver any content on menstrual health or indeed teach any RSE content at all (Department for Education, Citation2000). Although education about the menstrual cycle is included in the key stage 3 (11–14 years) science curriculum (Department for Education, Citation2015), it is not mandatory for all schools. For example, academies—state-funded schools which are run by an academy trust and represent 35% of primary and 77% of secondary schools in the United Kingdom (Office for National Statistics, Citation2021)—and private schools are exempt. Moreover, considering that the average age at menarche (the onset of menstruation) is 12, and may be as young as 8 (NHS, Citation2019), waiting until key stage 3 to teach about menstruation, if it is taught at all, is too late for many young people. In addition, the curriculum focuses on the science of menstruation rather than providing the practical support that girls need to cope with menstruation physically and emotionally.

Existing Research Into Menstrual Health Education

Menstruation is persistently stigmatized in society (ActionAid, Citation2018), and researchers have argued that this has led to inadequate coverage of menstrual health issues in schools (Holmes et al., Citation2021). Others also argue that education could be a powerful tool for promoting body literacy and health equity by empowering women to make informed choices regarding their sexual and reproductive health (Hahn & Truman, Citation2015; Lutz, Citation2018; Najmabadi & Sharifi, Citation2018; Rusakaniko et al., Citation1997). Despite its potential, experiences of menstrual education in England are currently poorly understood. In a cross-cultural (United Kingdom included) thematic synthesis of young people’s experiences of sex education, researchers found widespread feelings of vulnerability and lessons that were out of touch with young people’s lives (Pound et al., Citation2016). However, menstruation was not discussed at all in this analysis, suggesting that even within the field of sex education research, it is a neglected topic.

In recent years, the topic does seem to have gathered interest. For example, a more recent analysis of biology and sex education curricula in England identified significant gaps that included the topics of menstrual cycles and women’s health more generally (Maslowski et al., Citation2022). In 2018, the humanitarian organization Plan International conducted research into girls’ experiences of menstruation in the United Kingdom (Plan International, Citation2018). They found that 25% of girls felt unprepared and 14% did not understand what was happening to them during their first menstruation. One UK study, investigating beliefs around menarche in adolescent girls, covered education in more depth and found that many felt their education lacked sufficient detail (Wigmore-Sykes et al., Citation2021). However, this was a pilot study greatly limited by its small sample size of just 11 students from one school in Warwickshire. A study by Brown et al. (Citation2022) provided insight into some of the challenges faced by teachers in delivering menstrual cycle education in UK schools. A lack of time, teacher confidence, and resources were reported as the main barriers for delivery. While this study did not include the views of students, it does highlight the potential practical challenges and suggest actions for improvement from another stakeholder’s perspective.

Study Aims

Education about menstrual health could be fundamental in addressing some of the health, social, economic, and environmental challenges linked with menstruation. Lack of available data regarding young women’s experiences of menstrual health education in the United Kingdom is an important gap in knowledge. This paper contributes to the literature by exploring the perspectives of young women aged 18 to 24, seeking to understand the experiences they had during their time at school in England, across different school settings, and establish whether they felt they were adequately prepared. It explored the effectiveness of the content delivered, including that relating to health literacy, as well as the attitudes and approaches of the educators. The timing of this study coincides with a recent update in the United Kingdom’s RSE curriculum which, for the first time, specifically includes menstrual health as a compulsory topic (Department for Education, Citation2020a). This study explored the experiences of those taught under the previous RSE guidelines delivered from the year 2000.

Research questions:

What and how has information about menstrual health been delivered in schools?

What are young women’s thoughts and feelings about their educational experiences?

Have young women been sufficiently prepared to manage their menstrual health?

Methods

This study utilizes a mixed-methods approach to provide information about participants’ experiences of education, collecting both qualitative and quantitative data (Morse & Chung, Citation2003). Qualitative data add depth and richness to the quantitative descriptive statistics, providing detailed individual accounts of experiences. This enables in-depth exploration of certain research questions to ascertain the nuances in personal experiences and the meanings attached to these within a social context, which could not be captured by quantitative data alone (Agius, Citation2013; Hall & Harvey, Citation2018). This study collects views from a wide range of young women living across England and produces summary statistics about the practices within education using survey data, while also providing rich detail of participants’ experiences through interviews and open-ended survey questions. In June 2021, an online survey was shared, containing a mixture of open-ended and multiple-choice questions. At the end of the survey, respondents were given the opportunity to register their interest to take part in a virtual interview where more in-depth discussions about the themes raised in the survey could take place. All participants were aged between 18 and 24 and consented to participate. The research undertaken was granted full ethical approval by Anglia Ruskin University’s ethics approval panel.

Sampling

This study was targeted toward women, who represent the majority of people who experience or are expected to experience menstruation and were most likely to have been regarded as girls at school. This reasoning was explained in the recruitment posts and participants were generally understanding. For the purposes of this research, it was decided to focus on women between the ages of 18 and 24 years. Although a wider age range would have provided insights into how menstrual health education has evolved, it was important to gather views from people who had received schooling more recently to assess its relevance in a modern context. This age group included individuals who were likely to have been menstruating for several years (NHS, Citation2019) and had a chance to learn about menstrual health from sources outside school and reflect on their experiences with maturity, while having recent memories of the education they had received on the subject. Additionally, since the RSE curriculum changed in 2020, participants in this age bracket should have received education from the same 2000 RSE curriculum.

Many decisions on school curricula in the United Kingdom are devolved to its four nations (England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Island) and regulations vary by country (Raffe et al., Citation1999), including RSE (Department for Education, Citation2020a). Because of these differences, it was decided to limit this research to participants who lived and had received their education in England.

Data Collection

All research activities took place online to reach as many participants as possible and adhere to the university’s research guidelines during COVID-19. Due to the pervasive stigma surrounding the topic, anonymous online surveys were used to help encourage as many people as possible to take part and feel comfortable sharing their views. The software Online Surveys was selected for being compliant with UK data protection rules, including recent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) changes resulting from Brexit (Online Surveys, Citation2020).

Following a pilot, the survey was shared across the social media platforms Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter. An Instagram account and associated website with FAQs were created for participants to learn more about the project and eligibility criteria as the information that could be conveyed through social media posts was sometimes limited (Taylor, Citation2021). Non-response bias may have impacted the data, since some individuals are more likely to choose to take part than others. Bias is introduced when these individuals share particular values, such as those found in menstrual activism. To counteract these effects, surveys and interviews were kept short and informal. Simple language was used so that participants did not feel that they had to be experts in the subject and the focus was on their thoughts and feelings about their own experiences. Thank you messages were shared publicly on social media to show appreciation to participants and acted as a prompt to remind others to take part.

Distributing the survey online, the minimum target of 50 respondents was achieved after a few days, and the survey was closed 2 weeks after launching, having reached 140 responses. The survey was designed to provide an overview of what and how menstrual health education was delivered while providing an opportunity for respondents to reflect upon and share their thoughts and feelings about these experiences. Opportunities to collect more detailed accounts for richer data were provided with each section of closed-ended questions ending with an open-ended question for further comments: “Use this space if you would like to add any further information about your responses to the questions on this page.” A full list of survey questions can be found in Online Appendix A. Eight individual interviews also took place to explore some of the research questions in more depth. Responses from these were anonymized through the assignment of a numerical identifier and kept confidential. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured style, leaving the researcher free to explore new ideas that had not been previously considered (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019; DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006), and questions were asked under three broad themes: (1) What interviewees thought about their educational experiences, (2) what roles they thought schools should play, and (3) looking to the future, whether and how education could be improved. See Online Appendix B for a full list of interview questions.

Data Analysis

Quantitative responses to the online survey were predominantly analyzed through Online Surveys Software and Microsoft Excel to produce key descriptive statistics regarding respondents’ experiences. Qualitative data from interview transcripts and open-ended survey questions were analyzed through thematic analysis using NVivo software. This involved a process of data familiarization; generating initial codes; searching for, reviewing, and refining themes; and finally selecting and contextualizing compelling extracts that related to the research questions, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). These qualitative datasets were analyzed together but tagged so that the source (survey or interview) could be identified at any stage. While there is an abundance of research data from low-income contexts, due to the lack of available data from high-income contexts in which to ground the research, an inductive coding approach was adopted and themes were identified from the data themselves (Patton, Citation1990). During the coding process, 1,577 pieces of information were coded across 91 nodes. These were then organized into sub-themes and finally five overarching themes that relate to the study’s main research questions to cover participants’ key sources of menstrual health information, approaches and attitudes in education delivery, and participants’ feelings about their educational experiences and subsequent preparedness for managing menstrual health. Refer to Online Appendix C for an outline of the thematic framework. Note that herein “survey respondents” refers to survey participants, while “interviewees” refers to interview participants and “participants” refers to both survey respondents and interviewees.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents

A total of 140 young women participated in this study, 99.3% of whom had experienced menstruation. The mean age of survey respondents was 21.9 (SD ± 1.8) years. Further, 89.3% of survey respondents attended a state-funded primary school (with 10.7% private), and 82.9% attended a state-funded secondary school (with 17.1% private). Finally, 50.7% attended a religious school and 46.4% attended a non-religious school.

Schools as a Source of Information

The vast majority (90.0%) of survey respondents reported receiving at least some menstrual education during their time at school, while 5.0% said they did not receive any and 5.0% could not remember. Of those who did not receive education, 42.9% stated that the school did not offer any and the remaining 57.1% were unsure of a reason. These results suggest that most schools are choosing to teach about menstrual health, which is consistent with findings from other research (Brown et al., Citation2022; Maslowski et al., Citation2022).

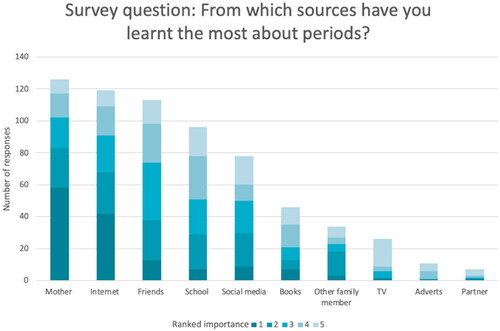

From a list of 10 options, 5.0% of survey respondents ranked school as the source from which they learned the most about menstruation. In comparison, 29.8% of respondents rated the internet as the most important source, with a further 6.4% specifically top-ranking social media. These results (see ) suggest the importance of self-generated knowledge. During the interviews and in the free-text options within the questionnaires, participants reinforced this with, for example, one interviewee explaining that “I've learned more from social media as an adult than I ever did at school.” This is backed up by further survey comments such as “it makes me sad I had to use the internet,” indicating that participants were disappointed that they had to rely on their own research and felt that schools should play a bigger role.

Teacher Attitudes Toward Menstrual Health Education

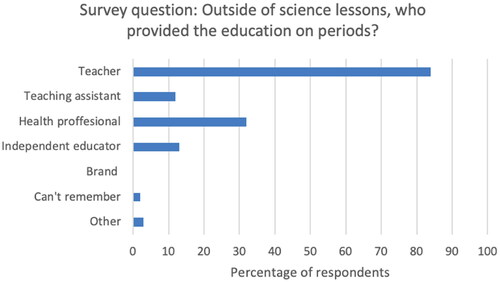

Survey respondents received menstrual health education from a variety of people in school, most commonly (83.7%) a teacher, with around a third (31.7%) being taught by a health professional, usually a school nurse (see ). Participants reported both positive and negative feelings regarding how teachers approached the subject of menstruation and the level of support they offered. For example, one interviewee described their teacher as “super caring” following a menstrual leaking incident. However, several reported experiences in which negative teacher attitudes—including obvious discomfort in teaching the subject, jokes, and sexist remarks—caused pupils to feel awkward and prevented them from being able to ask questions or discuss openly. For example, one interviewee shared:

Figure 2. Persons responsible for providing education. Responses were to the online survey question: “Outside of science lessons, who provided the education on periods?” Survey respondents were asked to tick all that apply, and figures show the percentage of respondents who selected each answer option (e.g., 100% would represent that all this question’s respondents chose that option). “Health professional” includes school nurses, and “Brand” refers to educators from menstrual product companies.

I just remember a woodwork teacher, someone literally saying “I need to go to the toilet because my period is leaking out of my underwear” because he said no multiple times and even then he was just saying, “oh God, this is why women shouldn’t be allowed to do woodwork classes.”

Several stated that these attitudes had a lasting impact on their own attitudes, as summed up in this interview response: “If they feel shame about it, why wouldn’t I?”

Sex Segregation

Sex segregation was a common feature of menstrual education, with 73.0% of survey respondents reporting that males and females were separated for at least some of their lessons on menstrual health. As a median average, survey respondents reported that they were separated for half of all their menstrual health education. This issue provoked much comment from participants as well as expression of a belief that lessons should be inclusive. In a word frequency analysis of responses to the survey question: “Please give up to five words to describe how you think the experience of period education in school should be,” the most common answers were (=1) inclusive, (=1) informative, (2) open, (3) detailed, (4) in-depth and (5) practical. The term “inclusive” was mentioned by over a fifth (21.6%) of survey respondents and was a common theme throughout. However, there were some differences in opinion around how this should be approached due the implications of stigma, LGBTQ + inclusivity, and access to safe spaces for female students. For example, the immaturity and shaming that came from their male peers was described as something that perpetuated the stigma and prevented others from engaging or asking questions. One survey respondent wrote, “it was always really embarrassing as the boys were in the same class and used to take the piss.” One interviewee explained the long-term impact of this shaming:

I think that’s where this sort of stigma around it came from for me personally, “cause you know, it was like well, boys are laughing at us because that’s what happens and it just stuck with me.”

Another interviewee added:

I think definitely the boys should be educated just as much as the girls … I had a conversation with a 26-year-old not last week who blocked his ears and was like “I can’t talk about this” and I'm like “you’re a grown up like for the love of God, like your girlfriend’s asked me a question.”

Menstrual Health and the School Curriculum

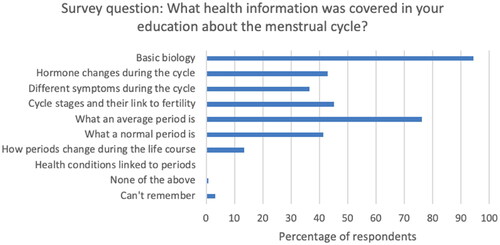

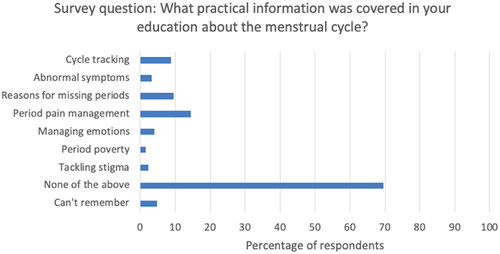

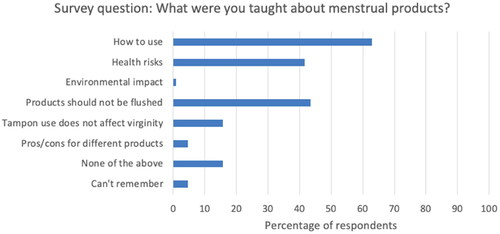

In a word frequency analysis of responses to the survey question: “Please give up to five words to describe your experience of period education in school,” the most common answers were (1) basic, (2) lacking, (3) brief, (4) scientific, and (5) limited. Participants frequently described their menstrual health education as being heavily science-based and lacking in practical information. Further, 94.4% of survey respondents reported that their education covered basic biological aspects of menstruation (see ) whereas, in response to the question, “What practical information was covered in your education about the menstrual cycle?” nearly 70% (69.6%) answered “none” (see ). Comments about the basic nature of lessons were common; one interviewee said that as a consequence, “you don’t end up going out of those lessons knowing your anatomy, knowing what should be happening during your period,” and several participants mentioned that lessons were only geared to prepare students for an examination.

Figure 3. Health information covered in school. Responses are to the online survey question, “What health information was covered in your education about the menstrual cycle?” Participants were asked to tick all that applied, and figures show the percentage of respondents who selected each answer option (e.g., 100% would represent that all this question’s respondents chose that option).

Figure 4. Practical information covered in school. Responses are to the online survey question, “What practical information was covered in your education about the menstrual cycle?” Survey respondents were asked to tick all that applied, and figures show the percentage of respondents who selected each answer option (e.g., 100% would represent that all this question’s respondents chose that option).

Information about health was especially lacking during school lessons. None of the survey respondents were taught about health conditions relating to menstruation, and just 3.2% reported learning about abnormal menstrual symptoms. Information about what was considered “normal” for menstruation was notably absent—an issue highlighted by previous researchers (Randhawa et al., Citation2021)—and was reported to cause fear and confusion. Several participants explained how this led them to believe something was wrong with them or, conversely, that their abnormal cycles were nothing to worry about. Some reported they felt discouraged from seeking medical advice and sometimes waited years for diagnoses of underlying health conditions. As an example, one survey respondent wrote:

Menstrual disorders/conditions were never mentioned, and that made me very confused because my periods didn’t fit what they described them as. I later found out I have endometriosis but didn’t get diagnosed until I was 20.

As someone who had abnormal periods and has now been diagnosed with endometriosis, it would have been very helpful for me to have been educated on what is considered not normal and informed that you shouldn’t just get on with cramps if they are debilitating.

Figure 5. Menstrual product information covered in school. Responses are to the online survey question, “What were you taught about menstrual products?” Survey respondents were asked to tick all that applied, and figures show the percentage of respondents who selected each answer option (e.g., 100% would represent that all this question’s respondents chose that option).

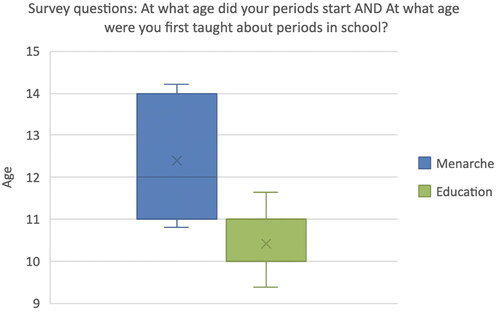

Timing of the Delivery of Menstrual Health Education

On average, survey respondents reached menarche at age 12.5 (SD ± 1.7) years, although this varied quite considerably, with an age range of 9 to 18. The age at which survey respondents were first taught about menstrual health at school ranged from 8 to 15, with a mean age of 10.5 (SD ± 1.1) years, often during the final year of primary school (see ). Quantitative data analyzed from the survey reveals that most respondents (78.6%) were taught about menstruation prior to menarche. However, 12.2% did not receive education until after the onset of menarche, and a further 9.2% were taught the same year they began menstruating, but it is unclear whether this occurred before or after menarche. Thus, overall, up to one in five (21.4%) survey respondents did not receive education until after menarche.

Figure 6. Timing of menarche and education. Box plot shows distribution of survey respondents’ age when menarche occurred and when they first received education about periods at school. Error bars (calculated to 1 standard deviation) are shown, and the “X” depicts the mean average for each dataset.

For those who did receive their education after the onset of menarche, they often commented on it, expressing a preference for earlier information, ahead of menarche, in order to help them and their peers prepare for this forthcoming aspect of their lives. One survey respondent noted, “I don’t think period education happens early enough, I had menstruated for 3 years before we had any sort of education.” Another interviewee added, “it would have been helpful to have that information earlier.”

Summary of Participants’ Experiences and Perceptions

At the end of the questionnaire survey, respondents were asked to rate the effectiveness of their school education in preparing them for dealing with menstruation. The ratings were mainly negative, with 62.4% of survey respondents giving a rating of “poor” or “very poor.” From the responses to this question, no respondents gave a rating of “very good,” and just 7.2% rated their education as “good.” Of those who received education, 92.9% agreed that they would have liked more or better education about menstruation at school. Although several participants noted that schools did not have to be the only source of menstrual health information, the high level of agreement with the aforementioned statement suggests that they thought that this source should be prioritized. This was backed up by comments made during the interviews. For example, one interviewee emphasized the importance of information being available at school for those lacking support at home or access to other sources, stating that it is “the place where most children go” and, for some children, the only place as for them “there was nothing else.”

Participants’ feelings regarding their menstrual health education were largely negative and may be summarized by this survey comment: “We are hugely let down by the education system.” Comments including “there needs to be much more education” from an interviewee and “I wish we had been better taught” from a survey respondent indicated that participants felt this was an important but under-discussed topic and demonstrated a clear desire for change. The majority left education without the practical information they needed to manage their menstrual health. Sometimes information about menstruation was lacking altogether, and in one extreme case, the interviewee was so underprepared for menarche that they thought they were seriously ill:

When I first had my period, I thought I was dying … I sat on the toilet and there was blood all over my legs, all over my pants, all into the loo, and I was sobbing, so I screamed for my mum.

I didn’t know that it lasted more than 1 day. I thought it was like a drop, and then that’s it for a month … when it carried on for more than 1 day, I was like, “oh my god, what’s going on? Am I ill?” So that was … actually quite scary.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand perceptions and assess the effectiveness of menstrual health education, as experienced by young women during their time at school in England. The findings suggest that for many, the menstrual health education they received failed to prepare them physically, mentally, or socially for the onset of menarche or for other aspects of their menstrual health, for a number of reasons. This included, for some, the lateness in the receipt of menstrual health education and, for many, its content and the approach taken in its delivery. Lessons caused a variety of feelings largely centered around fear, shame, and embarrassment. Participants reported that their school education had left them with a lack of awareness about abnormal symptoms, with evidence that this had long-term negative impacts for their health and well-being.

Findings from the present study evidence the need for greater menstrual health education in schools, as 10.0% of survey respondents reported that they did not receive or recall receiving any. This contrasts with findings from a study by Brown et al. (Citation2022) that showed that 37% of schools were not providing any menstrual education, although it did demonstrate that most schools are providing some. This difference highlights discrepancies in reported levels of provision and requires further research. For those who did receive education on this subject, its effectiveness in preparing students was rated poorly and 92.9% agreed it should have been better. Suggestions for improvement include earlier education with more informative, practical content that relates to dealing with menstrual health in day-to-day life, better guidance on what is considered normal and when to seek advice, and more inclusive lessons that are free from taboo. Broadly, these suggestions can be categorized under four key themes: attitudes, inclusivity, practical content, and timing of delivery. Research by Maslowski et al. (Citation2022) identified similar themes when analyzing student responses to a question regarding how sex education could be improved: LGBTQ + inclusivity, topic variety, logistical improvements, attitudes toward sex, gender equality, and applicability to real life. Although this study applied to a wider range of educational topics, the similarity demonstrates consistency within the literature, emphasizing young people’s desires for more relatable and inclusive reproductive health education.

Survey respondents in the present study also highlighted the need for education to be delivered earlier, with as many as 21.4% only learning about the topic in school after the onset of menarche. The timing of menstrual education has previously been highlighted by Ofsted (Ofsted, Citation2013) and others (Brown et al., Citation2022; Plan International, Citation2018; Wigmore-Sykes et al., Citation2021). The lateness in delivery is particularly concerning, especially considering the trend toward earlier menarche seen in recent decades (Posner, Citation2006; Sørensen et al., Citation2012). In 2000, RSE guidelines outlined the importance of preparing girls for menstruation in recognition that “about a third of girls are not told about periods by their parents” (Department for Education, Citation2000); thus, ensuring that information about menstrual health is delivered prior to menarche in schools seems imperative. Despite this, evidence suggests that schools are failing to prepare students in time.

There was also a focus on biological content within lessons (reported by 94.4%) (), while teachings on practical or health-related aspects—which could help young women to manage their menstrual health and well-being—were limited. Brown et al. (Citation2022) similarly highlighted that education in UK schools was scientifically focused on examinations and lacked information about symptom management or lived experiences.

Across the world, many girls begin menstruating unprepared, without the information they need or knowledge of where to seek help (Chandra-Mouli & Patel, Citation2017; Plan International, Citation2018). Reports also suggest that adults, including teachers, are ill informed and uncomfortable discussing the topic (Chandra-Mouli & Patel, Citation2017), highlighting an ongoing knowledge deficit. Despite growing recognition of menstrual health as an important public health issue (Babbar et al., Citation2022; Sommer et al., Citation2015), many gaps remain in the evidence to inform policy or programming (Critchley et al., Citation2020). While much of the research focuses on interventions in the Global South, this study demonstrates important educational gaps within a high-income context, and further research is needed to explore the educational practices and experiences within the UK and other high-income countries.

Study Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was the lack of input from teachers, which would have provided insight into the challenges schools face in delivering content about menstruation and menstrual health, including their views on the guidance and support that is offered. It was beyond the scope of this study to explore the perspectives of teachers. For example, Brown et al. (Citation2022) found that 80% of teachers felt that receiving training would be beneficial to them improving menstrual education. It is important that future research considers the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as teachers, parents, and policymakers, to inform recommendations for improvement.

This study asked participants aged between 18 and 24 years to report on their experiences retrospectively. While this meant that they were able to provide insight into the long-term impacts of their experiences, data collection relied on participants recalling information from their childhood, which may have been inaccurate due to memory loss and recall bias (Coughlin, Citation1990; Pipe et al., Citation1999) and may have been influenced by post-schooling experiences. Additionally, the reported experiences, particularly from older participants, may not reflect current practices. In September 2020, a revised RSE curriculum—which includes the topic of menstrual well-being—was introduced (Department for Education, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Further research is needed to explore the experiences of students who are currently in the schooling system and to understand whether and how practices have changed.

While the majority of young women who took part in this research did receive some menstrual health education, they reported that their male peers received roughly half as much, demonstrating an important inequality. If we are to eradicate menstrual stigma—as the UK government aims to achieve by 2030 (Government Equalities Office, Citation2019)—it will be important to include everyone, including male politicians and policymakers, in the effort. Future research should aim to include the perspectives of other young people, such as male and LGBTQ + students, to establish whether and how gender impacts the experience of menstrual health education.

Recommendations for Menstrual Health Education

The evidence from this study suggests that some schools in England may have in the past failed to fully prepare young women for managing their menstrual health and is therefore an issue for gender equality. While this research indicated that schools were one of many sources of information on menstrual health to which young women turn, it was an important one, and increasing the amount and quality of school-based menstrual health education—especially for those with limited opportunity to discuss the topic at home—is essential. This may help reduce the risk of them seeking inaccurate and possibly dangerous information elsewhere. Young women often felt “let down” and underprepared for their reproductive lives by the menstrual health education they received at school. There was also a clear desire by the participants for this to change. The key suggested features for improvement are summarized as follows:

Delivered earlier—Begin delivering menstrual health education from an earlier stage to ensure that more are informed before menarche and also supported subsequently.

Inclusive—Teach all students (regardless of sex or gender identity) about menstruation and menstrual health to improve understanding and reduce stigma.

Practical—In addition to biological information, provide practical information so that students know what is considered normal and are equipped to manage their menstrual health.

Conclusion

Inadequate education about menstrual health has the potential to have long-term detrimental impact on young people’s health and well-being. This mixed-methods study of 140 individuals aged 18 to 24 years found widespread inconsistencies and shortcomings in the educational practices they received while in school in England. These often left participants lacking basic knowledge and feeling unprepared. Quantitative analysis of survey responses revealed important evidence about missing menstrual health content, lateness in delivery, and negative feelings about educational experiences, while the qualitative thematic analysis of interviews and open-ended survey questions highlighted examples of stigmatized attitudes, considerations for inclusivity, and the consequences of poor preparation. In some cases, poor awareness about abnormal symptoms or menstrual disorders created barriers to accessing healthcare, as young women delayed seeking medical attention. Menstrual health literacy can empower young women with the tools they need to manage their menstrual health physically, emotionally, and socially. To advance gender equality, we must ensure that everyone who menstruates is properly supported to enjoy optimal health and have equal access to socioeconomic opportunities. Despite educational guidelines on the inclusion of menstrual health within the school curriculum, there is much more that can be done to ensure that consistent and appropriate learning takes place within schools.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.4 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank all those who participated in this research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- AAP, & ACOG. (2006). Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics, 118(5), 2245–2250. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2481

- ActionAid. (2018). More than one in three UK women face period stigma. https://www.actionaid.org.uk/latest-news/more-than-one-in-three-uk-women-face-period-stigma

- Agius, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research: Its value and applicability. The Psychiatrist, 37(6), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.113.042770

- APPG on Endometriosis. (2020). Endometriosis in the UK: Time for change. All Party Parliamentary Group. https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/sites/default/files/files/Endometriosis%20APPG%20Report%20Oct%202020.pdf

- Babbar, K., Martin, J., Ruiz, J., Parray, A. A., & Sommer, M. (2022). Menstrual health is a public health and human rights issue. The Lancet Public Health, 7(1), e10–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00212-7

- Bloody Good Period. (2021). Periods and menstrual wellbeing in the workplace—The case for change. Bloody Good Period. https://e13c0101-31be-4b7a-b23c-df71e9a4a7cb.filesusr.com/ugd/ae82b1_66bbbfefcf85424ab827ae7203b2c369.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, N., Williams, R., Bruinvels, G., Piasecki, J., & Forrest, L. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions and experiences of menstrual cycle education and support in UK schools. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 3, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.827365

- Bruinvels, G., Goldsmith, E., Blagrove, R., Simpkin, A., Lewis, N., Morton, K., Suppiah, A., Rogers, J. P., Ackerman, K. E., Newell, J., & Pedlar, C. (2021). Prevalence and frequency of menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with availability to train and compete: A study of 6812 exercising women recruited using the Strava exercise app. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(8), 438–443. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102792

- Chandra-Mouli, V., & Patel, S. V. (2017). Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0293-6

- Coughlin, S. S. (1990). Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 43(1), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3

- Critchley, H. O. D., Babayev, E., Bulun, S. E., Clark, S., Garcia-Grau, I., Gregersen, P. K., Kilcoyne, A., Kim, J.-Y J., Lavender, M., Marsh, E. E., Matteson, K. A., Maybin, J. A., Metz, C. N., Moreno, I., Silk, K., Sommer, M., Simon, C., Tariyal, R., Taylor, H. S., Wagner, G. P., & Griffith, L. G. (2020). Menstruation: Science and society. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(5), 624–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.004

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000057. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Department for Education. (2000). Sex and relationship education guidance. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/283599/sex_and_relationship_education_guidance.pdf

- Department for Education. (2015). Statutory guidance: National curriculum in England—Science programmes of study. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-science-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-science-programmes-of-study

- Department for Education. (2020a). Relationships education, relationships and sex education (RSE) and health education. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908013/Relationships_Education__Relationships_and_Sex_Education__RSE__and_Health_Education.pdf

- Department for Education. (2020b). Statutory guidance: Physical health and mental wellbeing (Primary and secondary). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/physical-health-and-mental-wellbeing-primary-and-secondary

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

- Endometriosis UK. (2020). Endometriosis awareness month launches to tackle the fact 54% don’t know about endometriosis. Endometriosis UK. https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/blog/endometriosis-awareness-month-launches-tackle-fact-54-don%E2%80%99t-know-about-endometriosis

- Girls Not Brides. (2017, May 26). Periods and child marriage: What is the link? Girls Not Brides. https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/articles/periods-child-marriage-link/

- Government Equalities Office. (2019, March 4). Penny Mordaunt launches new funds to tackle period poverty globally. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/penny-mordaunt-launches-new-funds-to-tackle-period-poverty-globally

- Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731415585986

- Hall, R., & Harvey, L. A. (2018). Qualitative research provides insights into the experiences and perspectives of people with spinal cord injuries and those involved in their care. Spinal Cord, 56(6), 527–527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0161-4

- Haque, S. E., Rahman, M., Itsuko, K., Mutahara, M., & Sakisaka, K. (2014). The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open, 4(7), e004607. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004607

- Hennegan, J., Winkler, I. T., Bobel, C., Keiser, D., Hampton, J., Larsson, G., Chandra-Mouli, V., Plesons, M., & Mahon, T. (2021). Menstrual health: A definition for policy, practice, and research. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29(1), 1911618–1911638. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1911618

- Hillard, P. J. A. (2014). Menstruation in adolescents: What do we know? And what do we do with the information? Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 27(6), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.12.001

- Holmes, K., Curry, C., Sherry, Ferfolja, T., Parry, K., Smith, C., Hyman, M., & Armour, M. (2021). Adolescent menstrual health literacy in low, middle and high-income countries: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052260

- Loughnan, L., Mahon, T., Goddard, S., Bain, R., & Sommer, M. (2020). Monitoring menstrual health in the Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 577–592). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_44

- Lutz, W. (2018). Education empowers women to reach their personal fertility target, regardless of what the target is. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 1, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2017s027

- Maslowski, K., Biswakarma, R., Reiss, M. J., & Harper, J. (2022). Sex and fertility education in England: An analysis of biology curricula and students’ experiences. Journal of Biological Education, 19, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2022.2108103

- Morse, J. M., & Chung, S. E. (2003). Toward holism: The significance of methodological pluralism. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200302

- Motta, T., Laganà, A. S., Valenti, G., LA Rosa, V. L., Noventa, M., Vitagliano, A., Chiofalo, B., Rapisarda, A. M., Rossetti, D., & Vitale, S. G. (2017). Differential diagnosis and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescence. Minerva Ginecologica, 69(6), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4784.17.04090-4

- Najmabadi, K. M., & Sharifi, F. (2018). Sexual education and women empowerment in health: A review of the literature. International Journal of Women’s Health and Reproduction Sciences, 7(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.15296/ijwhr.2019.25

- NHS. (2019). Starting your periods. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/periods/starting-periods/

- NICE. (2019). Premenstrual syndrome. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/premenstrual-syndrome/

- Office for National Statistics. (2021, February 2). Schools, pupils and their characteristics academic year 2019/20. GOV.UK. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- Ofsted. (2013). Not yet good enough: Personal, social, health and economic education in schools. Ofsted. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413178/Not_yet_good_enough_personal__social__health_and_economic_education_in_schools.pdf

- Online Surveys. (2020, May 7). Terms and conditions. https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/terms-and-conditions/

- Parker, M., Sneddon, A., & Arbon, P. (2010). The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: Determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG, 117(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x

- Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- phs Group. (2019). Lifting the lid on period poverty: Period poverty research. phs Group. https://www.phs.co.uk/media/2401/phs_periodpovery-whitepaper.pdf

- Pipe, M.-E., Gee, S., Wilson, J. C., & Egerton, J. M. (1999). Children’s recall 1 or 2 years after an event. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.781

- Plan International. (2018). Break the barriers: Girls’ experiences of menstruation in the UK. Plan International UK. https://plan-uk.org/file/plan-uk-break-the-barriers-report-032018pdf/download?token=Fs-HYP3v

- Popat, V. B., Prodanov, T., Calis, K. A., & Nelson, L. M. (2008). The menstrual cycle: A biological marker of general health in adolescents. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1135(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1429.040

- Posner, R. B. (2006). Early menarche: A review of research on trends in timing, racial differences, etiology and psychosocial consequences. Sex Roles, 54(5-6), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9003-5

- Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ Open, 6(9), e011329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

- Raffe, D., Brannen, K., Croxford, L., & Martin, C. (1999). Comparing England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland: The case for ‘home internationals’ in comparative research. Comparative Education, 35(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050069928044

- Randhawa, A. E., Tufte-Hewett, A. D., Weckesser, A. M., Jones, G. L., & Hewett, F. G. (2021). Secondary school girls’ experiences of menstruation and awareness of endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 34(5), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2021.01.021

- Rogers, P. A. W., D’Hooghe, T. M., Fazleabas, A., Gargett, C. E., Giudice, L. C., Montgomery, G. W., Rombauts, L., Salamonsen, L. A., & Zondervan, K. T. (2009). Priorities for endometriosis research: Recommendations from an international consensus workshop. Reproductive Sciences, 16(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719108330568

- Rusakaniko, S., Mbizvo, M. T., Kasule, J., Gupta, V., Kinoti, S. N., Mpanju-Shumbushu, W., Sebina-Zziwa, J., Mwateba, R., & Padayachy, J. (1997). Trends in reproductive health knowledge following a health education intervention among adolescents in Zimbabwe. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/12087

- Santhanakrishnan, I., & Athipathy, V. (2018). Impact of health education on menstrual hygiene: An intervention study among adolescent school girls. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health, 7(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijmsph.2018.0307920032018

- Sex Education Forum. (2021). Our history—30 years of campaigning. https://www.sexeducationforum.org.uk/about/our-history-30-years-campaigning

- Solomon, C. G., Hu, F. B., Dunaif, A., Rich-Edwards, J. E., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., Speizer, F. E., & Manson, J. E. (2002). Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 87(5), 2013–2017. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471

- Sommer, M., Hirsch, J. S., Nathanson, C., & Parker, R. G. (2015). Comfortably, safely, and without shame: Defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1302–1311. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525

- Sommer, M., Torondel, B., Hennegan, J., Phillips-Howard, P. A., Mahon, T., Motivans, A., Zulaika, G., Gruer, C., Haver, J., & Caruso, B. A. (2021). How addressing menstrual health and hygiene may enable progress across the Sustainable Development Goals. Global Health Action, 14(1), 1920315. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1920315

- Sørensen, K., Mouritsen, A., Aksglaede, L., Hagen, C. P., Mogensen, S. S., & Juul, A. (2012). Recent secular trends in pubertal timing: Implications for evaluation and diagnosis of precocious puberty. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 77(3), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336325

- Taylor, P. (2021). Menstrual education research project. Planet Period. https://planetperiod.wixsite.com/research

- Tull, K. (2019). Period poverty impact on the economic empowerment of women. K4D Helpdesk Report 536. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

- UN. (2021, June 22). Link between education and well-being never clearer, UN pushes for ‘health-promoting’ schools. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/06/1094552

- UN Women. (2019). Social protection systems, access to public services and sustainable infrastruture for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. 2019 Commission on the Status of Women. Agreed Conclusions. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/CSW/63/Conclusions63-EN-Letter-Final.pdf

- UNESCO. (2014). Puberty education & menstrual hygiene management. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226792

- UNFPA. (2021). Menstruation and human rights—Frequently asked questions. United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/menstruationfaq

- UNGA. (2021, July 5). Menstrual hygiene management, human rights and gender equality. Human Rights Council 47th Session. https://undocs.org/A/HRC/47/L.2?fbclid=IwAR19nmHd6pOjaUebY-nNl_v8hskAuf2D3qSb4rRD0_uymt1ITOCDEo8kRGM

- Wang, S., Wang, Y.-X., Sandoval-Insausti, H., Farland, L. V., Shifren, J. L., Zhang, D., Manson, J. E., Birmann, B. M., Willett, W. C., Giovannucci, E. L., Missmer, S. A., & Chavarro, J. E. (2022). Menstrual cycle characteristics and incident cancer: A prospective cohort study. Human Reproduction, 37(2), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deab251

- Wang, Y.-X., Arvizu, M., Rich-Edwards, J. W., Stuart, J. J., Manson, J. E., Missmer, S. A., Pan, A., & Chavarro, J. E. (2020). Menstrual cycle regularity and length across the reproductive lifespan and risk of premature mortality: Prospective cohort study. BMJ, 371, m3464. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3464

- Wigmore-Sykes, M., Ferris, M., & Singh, S. (2021). Contemporary beliefs surrounding the menarche: A pilot study of adolescent girls at a school in middle England. Education for Primary Care, 32(1), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1836678

- Winkler, I., & Roaf, V. (2014). Bringing the dirty bloody linen out of the closet—Menstrual hygiene as a priority for achieving gender equality (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2575250). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2575250

- World Bank. (2016, June 27). Globally, periods are causing girls to be absent from school. https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/globally-periods-are-causing-girls-be-absent-school