Abstract

Despite three decades of policy to promote community participation of people with intellectual disabilities, many remain socially excluded. There is limited evidence about effective strategies to support community participation and programs seldom make the central proposition or the program logic explicit. This study aimed to describe the program logic and outcomes of a program that aimed to support community participation through increasing participants’ sense of identity and belonging to the Arts community. A case study design was used. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews with 5 participants, 6 staff and 5 family members of participants, non-participant observation, review of program documents, and completion of part 1 of the short form Adaptive Behavior Scale. The data were analysed qualitatively using a program logic as the framework. The program created studio space staffed by professional artists who used a hand in glove method to support art practice of people with intellectual disabilities. Individual outcomes for participants were threefold: development of positive identities as working artists; a sense of belonging to an art community, and; connections to a locality and peer friendships. This descriptive case study made explicit the program’s underpinning logic, and the design components that led to outcomes for individual service users. Understanding the logic of effective programs such as this will assist in scaling up and development of similar programs, and help people with intellectual disabilities and their families to assess the programs on offer.

Promoting community participation of people with intellectual disabilities is a long standing policy aim that has been difficult to achieve (Amado, Stancliffe, McCarron, & McCallion, Citation2013; Gray et al., Citation2014). Community participation is a slippery concept, which may be conceptualised quite differently by the programs aiming to support it (Clifford Simplican, Citation2019; Overmars‐Marx, Thomése, Verdonschot, & Meininger, Citation2014; Simplican, Leader, Kosciulek, & Leahy, Citation2015). A scoping review identified three types of programs (Bigby, Anderson, & Cameron, Citation2018). These were: 1) programs that conceptualised community participation as social relationships and supported people with intellectual disabilities to develop and maintain social networks, friendships and relationships either with peers or people without disabilities (Harlan-Simmons, Holtz, Todd, & Mooney, Citation2001; Heslop, Citation2005; Ward, Windsor, & Atkinson, Citation2012, Ward, Atkinson, Smith, & Windsor, Citation2013), 2) programs that conceptualised community participation as convivial encounter and created opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to have social interactions with people without disabilities in community or commercial places based around shared activities and purpose (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2015; Craig & Bigby, Citation2015; Lante, Walkley, Gamble, & Vassos, Citation2011; Stancliffe, Bigby, Balandin, Wilson, & Craig, Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2015); and, 3) programs that conceptualised community participation as having a sense of belonging and identity, and created opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to develop their interests and a related identity that acted as a catalyst for contact with others, both with and without disability, with similar identities. (Darragh, Ellison, Rillotta, Bellon, & Crocker, Citation2016; Harada, Siperstein, Parker, & Lenox, Citation2011; McClimens & Gordon, Citation2009; Stickley, Crosbie, & Hui, Citation2012; Tedrick, Citation2009). Outcomes of all three types of programs were commonly framed as: personal development such as skills, self-esteem or confidence; increased social networks, or; subjective experiences such as enjoyment or happiness.

The reform of Australia’s disability service system through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS, Citation2013) introduced individualised funding packages for the ‘reasonable and necessary’ disability related supports of eligible participants. A significant proportion of funding for adult participants (23.5%) is directed towards supporting community participation (NDIS, Citation2019). The largest study of the NDIS to date found that people with intellectual disabilities gained less clear benefits around social participation compared to other groups of people with disabilities (Mavromaras et al., Citation2018). In contrast, a smaller internal survey of participants at the time of initial plan preparation and follow up review found that, adults with Down Syndrome were more likely to have increased their community and social participation but this was in disability specific rather than mainstream groups (NDIS, Citation2018). No data were available about the type of disability specific groups attended or associated outcomes for participants. There is debate about the role of disability specific groups in furthering community participation with some commentators perceiving them as furthering segregation rather than social inclusion (Cummins & Lau, Citation2003; Renwick et al., Citation2019).

Individualised funding enables people with intellectual disabilities to choose the type of community participation and associated support they prefer. In order to do this they require clear information about aims and outcomes of different types of programs. In turn disability support organisations must be able to articulate the rigor and the program logic that underpins the support they offer and intended outcomes, for the people who purchase them.

Aims

This article presents a case study of a program that aimed to support the sense of belonging and identity of participants, namely the third type of community participation program, identified by Bigby et al. (Citation2018). The program chosen was perceived as being a “promising” or a successful example of this type of program. The aim of the study was to describe the program logic and participant outcomes of this program and in doing so make explicit the implicit program logic and identify components of a successful program of this type. A program logic is the central proposition about the way a program will achieve its aims, and the strategies or actions important to its success (Clement & Bigby, Citation2011; Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011; Rossi, Lipsey, & Freeman, Citation2004). It can be likened to a design blueprint that enables replication or evaluation of similar programs. Making explicit the program logic of promising programs will also assist people with intellectual disabilities and their families to exercise choice and appraise community participation programs.

Method

Arts Project was identified by the project reference group that comprised representatives from across the disability sector as a “promising” program of high quality. A case study method was chosen as it had the potential to enable an in depth understanding of a particular social phenomenon, in this case the Arts Project program (Richards & Morse, Citation2012). A case study involves the collection of different type of data and data from multiple sources, to enable a richer picture to be developed than would occur by relying on any one single source (Yin, Citation2009). The different types of data in this study included perspectives of participants, their families, staff and managers, as well as formal written information about the program in the form of annual reports, program and job descriptions and policies.

Recruitment and consent

The program director was approached and agreed to participate in the study. She circulated information about the study to staff, participants and their families. The study was explained further by the researchers to those interested before they were invited to sign a consent form. A family member was involved in the consent process for participants who normally had this type of support for decision making. The study was approved by the University Human Ethics Committee. All names have been changed and disguised to ensure anonymity, however with permission of the Director the program name has not been changed.

Data collection and participants

Data about the program design, perspectives of different stakeholders about it and the impact on participants’ lives were gathered using semi structured interviews with 5 participants, 6 staff, 5 parents or primary carers of participants and from review of program documents and reports. The first author spent 12 hours over several days in the studio as a non-participant observer and attended two gallery events. Detailed field notes were written after the observations. In addition, a family or staff member who knew a participant well completed the short form of the Adaptive Behavior Scale (SABS) Part 1 (Hatton et al., Citation2001) to provide an indication of the person’s level of intellectual disability.

Data analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. A template approach to analysis was used which meant both deductive and inductive coding was used (King, Citation2012). A program logic model provided the initial analytical framework (Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011) and data were extracted from transcripts, field notes and documents about key program assumptions and components. Data were also analysed inductively which provided opportunity for development of descriptive codes, particularly around outcomes and specific strategies. NVivo 10 software was used to manage and code the data. The full-scale score for Part 1 of the ABS was estimated from the SABS using the formula provided in Hatton et al. (Citation2001). All data were collected during the period October 2016 to February 2017, as the NDIS was being implemented in Victoria.

Findings

The 5 participants were aged between 30–50 years, 2 were male. They all had a mild intellectual disabilities with scores on the Adaptive Behaviour Scale ranging from 180–277 with an average of 249 (a score of below 151 is commonly used to differentiate people with more severe intellectual disability). They all used words to communicate and had English as their first language. All had regular contact with family, could name an advocate, and 4 out of 5 said they had regular contact with friends. The first part of the findings describes the program logic of Arts Project, which was pieced together from the document review and interviews, and the second part, the outcomes for participants.

Program logic model

Central proposition

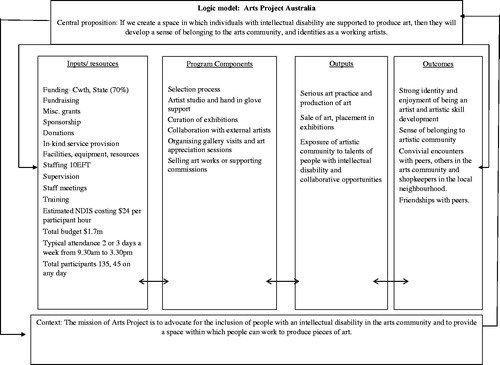

sets out the logic model of the program. Its central proposition was that “if a space is created in which individuals with intellectual disabilities are supported to produce art, then they will develop a sense of belonging to the arts community, and identities as a working artists.”

All the staff interviewed had a clear understanding of the aims of the program. For example, Katherine, said, “our mission is to promote, support and advocate… Support artists with a disability, promote their work and advocate their inclusion, and that’s the bottom line.” The studio manager saw the mission simply as “for people with an intellectual disability to make art.” Staff were also clear about what the program did not provide, and its difference from other programs that might at first glance appear similar;

We’re not trying to fix people, we’re trying to supply a space where artists can work, so if you need support in other areas, you go somewhere else. (Fiona, staff)

… the organisation is about the artist having a serious arts practice. It’s not just a leisure activity. (Lesley, staff)

…so, we don’t do dance lessons, and we don’t do cooking… from where we are, it’s about helping artists develop relationships with artists that don’t work here, other artists, external artists, curators and gallerists. (Katherine, staff)

The Executive Director summed up the program:

We’re not a disability organisation, we’re an arts organisation, where the artists happen to have a disability. That’s how I prefer to look at it. So, we don’t bang on about the disability, we bang on about the art.

Program inputs

The NDIS was being progressively implemented at the time of the study and funding was in transition to a user pays model funded from participants’ NDIS plans. Prior to this, the program had been funded by Commonwealth and State governments and from the sale and lease of art and merchandise, memberships and one-off grants. It had been a hybrid funded neither as an employment or day program. A few volunteers provided free labour in the studio or as one-off in-kind contributions. For example, an architect had designed the studio and gallery, and some professional artists acted as mentors or curators of exhibitions. The building was fully owned by the program, and included was purpose built and well-equipped studio space and ground floor exhibition space. The overall annual budget in 2018 was $1.7 m with the estimated cost per participant hour as $24.

There were the equivalent of 10 full time staff; 4 full time, 16 part time and 3 casual. As well as staff artists, there was a management team of an Executive Director, Business Manager, Studio Manager and Gallery Manager and administration staff. All the staff had a bachelor’s degree and staff artists who worked with participants in the studio were required to have a Bachelor of Fine Arts or equivalent. Few had any form of training or education about disability. As one staff member said;

We have a few staff who do have some disability training, or background, but if you look at the position description, it’s nice, but not required…the requirement, is that you have to have a fine arts degree. And, we try to avoid people with arts therapy background, even though we do have one staff member who does have arts therapy background, but she recognises the difference between what we do at Arts Project and what she’s been trained to do, and she’s very good at making sure she doesn’t bring that with it. (Fiona, staff)

On average, staff had worked in the programme for 4–5 years, with the longest serving member having been there for 12 years. Staff were strongly committed to their work, as one explained;

I feel like the staff are all passionate and engaged in the work they do. They’re all here for the right reasons…staff artists will go above and beyond in a kind of unpaid capacity…it tells me that they’re interested just beyond coming here as a day job. (Stephen, staff)

Staff participated in regular training on disability service standards, first aid, and managing complex and challenging behaviours. Regular staff meetings and daily “studio debriefings” were also scheduled.

Program components

Selection and attendance

The program was open to anyone with intellectual disabilities who is interested in art. Two or three potential participants enquired about the program every week. They were invited for a tour of the studio and gallery and to talk with the studio manager about their interest. If there was a vacancy, then an interested applicant would be invited to attend for a trial period.

I just want to see that they want to make a commitment to being a studio artist here. And then we have an enrolment process, and then we’ll give them a probationary period, which generally will just then turn into a prolonged enrolment in the studio. (Stephen, staff)

Several of the staff noted that slowly introducing people into the program and carefully checking their interest in making art had led to few people being asked to leave the program;

There have been times when we’ve asked people to leave, but it’s very, very rare and it’s usually to do with their behaviour which indicates that they’re not happy at Arts Project. (Fiona, staff)

The program does not provide support with activities of daily living such as eating lunch or using the toilet. If this type of support was needed then it had to be organised and funded separately by the participant.

Artists attended the studio between 1 and 5 days per week, with most attending for 3 days. There were no limits the period they could attend and one had been with Arts Project for 23 years.

A “hand in glove” approach to support

Staff artists created a “nurturing” environment where artists chose the type of art they wanted to make, explored different mediums and developed their skills. One staff member explained the difference between an art class and the art studio approach of the program;

…the artists are seen as people that have their own distinct style and they are developing a strong arts practice of their own, alongside their peers, the mainstream artist peers in the wider community. So rather than it being like a classroom situation, where we are all doing the same thing today, it’s about them having their own arts practice in an arts studio, and we are just facilitators who are supporting them. It’s not about directing them so much. It’s about being a nurturing environment … (Lesley, staff)

Staff described their support for artists as ‘hand in glove.”

We expect the staff artists to engage with and support people as they are making art. Not to be hands on, interfering, but supporting and sometimes being available to share specialist knowledge…about materials, techniques… (Stephen, staff)

The gallery manager described staff as “opening up the worlds” of participants through collaboration, support and advocacy. The participant observations in the studio and gallery spaces saw affirmative and warm interactions between artist and staff, that often had an element of humour. There were positive reinforcements about progress on pieces of art from all the staff and gentle but direct approaches to managing disruptive or anti-social behaviours. The studio was a work-like environment in which all were engaged in production and as workers. People attended on set days and at set times, and there were features of it being a workplace, such as tea and lunch breaks, offices and managers.

Exhibitions and collaborations

An annual gala show featured exhibits by all the 135 artists and during the year other shows and solo exhibitions featured some of the more experienced artists. A small number of the artists participated in a group called the “Northcote Penguins” that explored art history and appreciation through talks, gallery visits and tours.

The commitment to providing a place for individuals to produce art and to be included in the creative but commercially competitive arts community meant that whilst everyone made art in the studio, not all were selected to exhibit their work in solo exhibitions or take part in other activities.

I think it’s treating the people as adults in this community and not being tokenistic about what we do. Not everybody gets a poster for participating. We think that’s part of being an artist, and you don’t always have success, and you don’t always get recognised, and sometimes you get pushed down and down and down again and again and again, and so long as we’re there to make sure that we support them through that process, it’s an important part of being an artist, I think. So, avoiding that tokenism that you can get in a lot of disability services… (Fiona, staff)

Collaborations with external artists and galleries were an important activity which the studio manager described as being of benefit both to the artists at Arts Project and the external artists:

A lot of the feedback we’ve had is it’s a two-way learning process. So, the external contemporary artist will come in and either work in the studio amongst our guys, or they’ll go to their studio, but either way, they’ll let us know that it actually helped their own practice as well. They got some things from the way the artists they worked with worked and thought about things, that they are taking on to their own way of working. (Stephen, staff)

Through its exhibitions and collaborations with external artists, Arts Project had developed a strong profile, nationally and internationally as a provider of supportive space in which people with intellectual disability could produce art and as a centre of excellence for “outsider art.”

Program outputs

The primary output was the production of pieces of art using various mediums, which included curated various exhibitions of participants’ art work during the year that not only displayed but also sold the art. Pieces were also placed in external exhibitions, such as the Museum of Everything exhibition held at the Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania in November 2017. The exposure of the art community and the general public to the artistic talents of people with intellectual disabilities might also be considered as an output.

Program outcomes

Staff, family members and artists gave similar examples of the multifaceted outcomes of participation. These included: development of positive identities as working artists, a sense of belonging to a wider community of artists, and friendships and connections to a community of peers and a locality.

Development of strong positive identities as working artists

John, one of the artists, when asked what benefit he got from attending the program, said: “I am an artist. People like my stuff. They buy my stuff. Mum likes it. It’s a better place than other places I’ve been in the past. Now I am an artist.” The notion of developing a career as an artist and being supported to be a working artist was echoed by both staff and family members. The business manager described conversations about gaining an identity as an artist with the parents of several participants;

I got to sit down with [Ian, artist] and his mum and dad and I asked Ian, “Are you an artist?” He says, “Yes, I think I am. Yes, I am. I’m an artist”, which was really quite nice. And his parents told me when he’s at home, his language about coming to Arts Project is, “I’m off to work. I have to go to work.” (Fiona, staff)

The mother of one of the artists commented that Arts Project had, over many years “mentored, supported and nourished” her daughter’s sense of herself as an artist and that this had transformed her confidence and happiness.

Artists who had sold or shown art often expressed a great sense of pride, which was shared with peers and staff;

I just enjoy those small moments of success, just when someone has a little breakthrough, or when someone’s spent a long time trying to accomplish a goal of theirs and they achieve that. (Stephen, staff)

…I get paid for what I’m good at…When someone buys it, I know that someone loves it more than I do! (John, artist)

I had a solo show. I’ve been doing my art for years. (Elisabeth, artist)

A sense of belonging to an art community

Some participants had also gained a sense of belonging to the wider arts community through exhibitions of their work at the Arts Project gallery and in other galleries in Australia and overseas. This was recognised by both parents and staff.

Artists like [Dan] have their work in the National Gallery, people collect his work, he is acknowledged as an artist by other artists (Katherine, staff)

…it’s being able to be part of the wider community by her work being displayed in the exhibition centre or Fed [Federation] Square it sort of heightens the level of participation that normally she wouldn’t be able to access… (Kate, parent)

Commenting on her son’s sense of belonging to an art community, Connor’s mother said with a laugh, “he just fits into that art wanker world.” Participants’ own art was the vehicle for building connections to a community of those interested in art. As one staff member said, “so, it is very much – it’s the studio that people come to, and make art, and that goes out into the community and people come in.”

Connections to a locality and peer friendships

Artists also had a sense of belonging to the small community built around the program which comprised peers and others in the neighbouring locality. Only one of the artists interviewed described having social interactions with other Arts Project artists outside the program, but all spoke enthusiastically about the supportive and positive relationships they had developed with staff and other artists;

I’ve got good friends here and we all love doing our art. They are very understanding of my problems. I feel comfortable… (Elisabeth, artist)

We are artists when we are here. I think my stuff is pretty good. Other people say good things about it. (Connor, artist)

I like being here and being around my friends. (Carol, artist)

Connections to the locality had developed over the long period of time that the organisation has been based there. The artists described a level of comfort and safety in that community which they saw as a “friendly place” where convivial encounters took place. The staff described the connection and positive regard of the local community for the artists as grounded in recognition of them as part of Arts Project and as individual artists. Artists had developed a sense of belonging which had engendered a “sense of confidence” about “moving about in the world” (Emma, staff). The studio manager commented that, “from our point of view, it’s just trying to have the artists engage with the broader community, but in an unforced way.”

Vignette

This vignette illustrates outcomes for one participant:

Elisabeth, a 37-year-old artist has worked in the Arts Project studio for 20 years, currently four days a week. She lives with her mother, and travels the 15k to the studio alone by tram and train. She began working with acrylics but found them “too messy” so experimented with other media. Currently, she enjoys drawing landscapes and working with ceramics. She has had a solo show in the Arts Project gallery and her work has been displayed in other exhibitions. She has worked on several collaborations with other artists and said she was “really happy” with her work. She has sold several pieces which she says was “very exciting” but “strange” that someone she has never met had bought them.

Elisabeth said that the staff make her feel “safe and comfortable” and it “feels good” to know they are always available for a chat. She has 3 close friends in the studio and, although she doesn’t see them outside the studio, says that they are good to talk to and eats lunch with them each day. Elisabeth contrasted the comfort and safety she feels at Arts Project with the discomfort she sometimes feels on public transport, where people “pick up” that she has an intellectual disability and are rude which makes her “get very upset.” Elisabeth described the Arts Project locality as “friendly,” saying that the café staff “know all the artists” and are “kind.” Elisabeth says that the supportive staff at Arts Project and her friends and family have helped her to manage “things that are very hard” and to be confident about trying new things and enjoying them.

Discussion

This program should not be mistaken for a segregated program that teaches art to people with intellectual disabilities. Rather it had been designed around the specific conceptualisation of community participation as belonging and identity. Its program logic was based on the proposition that providing a space and the right kind of support to produce art for people with intellectual disabilities interested in art would generate identities as working artists and a sense of belonging to the wider arts community. The community that the program aimed to support participants to be part of was the wider arts community. Close relationships and collaborations occurred in what might be seen as a segregated studio environment but also further afield through collaborations with external artists. Incidentally, the program also generated peer friendships within the confines of the studio and connections to the locale in which was situated. Its program logic reflected similar creative arts programs reported in the literature, though these have been described in much less detail (Darragh et al., Citation2016; Stickley et al., Citation2012).

This descriptive case study indicates a purposeful and skilled approach to supporting community participation. Staff used a skilled microlevel practice of a hand in glove method to support art practice of participants. This facilitative and supportive practice rather than a directive and supervisory approach helped to build working relationships and a sense that all were artists working together in a studio. Staff used their connections to the art world to facilitate collaboration and inclusion of artists with intellectual disabilities and their work in the broader arts community. Identifying the design components of a promising program such as this, particularly the skills required for staff, provides possibilities for replication and informed choice by consumers rather than relying on the personalities of charismatic leaders to make judgements about programs. This and other similar programs, illustrate the way that programs solely for people with intellectual disabilities, can create a sense of social identity and recognition that acts as a catalyst for a sense of belonging to broader mainstream communities (Renwick et al., Citation2019). In some respects this reflects the subtle radicalism of self-advocacy programs identified by Anderson and Bigby (Citation2017), whereby membership of a segregated group creates possibilities for people with intellectual disabilities to assume a positive identity which acts as a catalyst for inclusion and belonging in the broader community.

Conclusion

Arts Project is a promising example of a program which supports community participation for people with intellectual disabilities. Its focus on developing individual skills and building identity challenges narrow conceptualisations of and strategies for supporting community participation that often privilege simpler understandings of inclusion as programs or places where people with and without disabilities engage together. In the scaling up of individualised funding to support community participation, as is currently occurring in Australia, there is potentially much to learn from programs such as Arts Project that facilitate and support a range of social interactions for participants with their peers, with local community members and with other artists with and without disabilities who are working in other studios in Australia and around the world. The framing of the program as an “art” rather than a “disability” program was crucial to the way it was regarded by staff, participants and those in the broader communities. Arts Project was a workplace for working artists, not a day program, and enabled participants like John to say with great satisfaction “I am an artist.”

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the Australian Government managed by the Disability Research and Data Working Group, the contribution of Dr Nadine Cameron to the research and the partnership with NDS that managed the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amado, A., Stancliffe, R., McCarron, M., & McCallion, P. (2013). Social inclusion and community participation of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(5), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.5.360

- Anderson, S., & Bigby, C. (2017). Self-advocacy as a means to positive identities for people with intellectual disability: “We just help them, be them really”. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(1), 109–120.

- Bigby, C., Anderson, S., & Cameron, N. (2018). Identifying conceptualizations and theories of change embedded in interventions to facilitate community participation for people with intellectual disability: A scoping review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12390

- Bigby, C., & Wiesel, I. (2015). Mediating community participation: Practice of support workers in initiating, facilitating or disrupting encounters between people with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12140

- Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2011). The development and utility of a program theory: Lessons from an evaluation of a reputed exemplary residential support service for adults with severe intellectual disability and challenging behaviour in Victoria. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24(6), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2011.00634.x

- Clifford Simplican, S. (2019). Theorising community participation: Successful concept or empty buzzword? Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 6(2), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2018.1503938

- Craig, D., & Bigby, C. (2015). “She’s been involved in everything as far as I can see”: Supporting the active participation of people with intellectual disability in community groups. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.977235

- Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. L. (2003). Community integration or community exposure? A review and discussion in relation to people with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00157.x

- Darragh, J., Ellison, C., Rillotta, F., Bellon, M., & Crocker, R. (2016). Exploring the impact of an arts‐based, day options program for young adults with intellectual disabilities. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2015.1075416

- Funnell, S. C., & Rogers, P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gray, K., Piccinin, A., Keating, J., Taffe, J., Parmenter, T., Hofer, S., Einfeld, S., & Tonge, B. (2014). Outcomes in young adulthood: Are we achieving community participation and inclusion? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(8), 734–745. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12069

- Harada, C., Siperstein, G., Parker, R., & Lenox, D. (2011). Promoting social inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities through sport: Special Olympics International, global sport initiatives and strategies. Sport in Society, 14(9), 1131–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.614770

- Harlan-Simmons, J., Holtz, P., Todd, J., & Mooney, M. (2001). Building social relationships through valued roles: Three older adults and the community membership project. Mental Retardation, 39(3), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2001)039<0171:BSRTVR>2.0.CO;2

- Hatton, C., Emerson, E., Robertson, J., Gregory, N., Kessissoglou, S., Perry, J., Felce, D., Lowe, K., Noonan Walsh, P., Linehan, C., & Hillery, J. (2001). The adaptive behavior scale-residential and community (part I): Towards the development of a short form. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00072-5

- Heslop, P. (2005). Good practice in befriending services for people with learning difficulties. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2004.00310.x

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research. Sage.

- Lante, K., Walkley, J., Gamble, M., & Vassos, M. (2011). An initial evaluation of a long‐term, sustainable, integrated community‐based physical activity program for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 36(3), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2011.593163

- Mavromaras, K., Moskos, M., Mahuteau, S., Isherwood, L., Goode, A., Walton, H., Smith, L., Wei, Z., & Flavel, J. (2018). Evaluation of the NDIS. Final report. National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University.

- McClimens, A., & Gordon, F. (2009). People with intellectual disabilities as bloggers: What’s social capital got to do with it anyway? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 13(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629509104486

- National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. (2013). Commonwealth acts. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2013A00020

- National Disability Insurance Scheme. (2018). NDIS participant outcomes.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme. (2019). Quarterly reports – Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/quarterly-reports.

- Overmars‐Marx, T., Thomése, F., Verdonschot, M., & Meininger, H. (2014). Advancing social inclusion in the neighbourhood for people with an intellectual disability: An exploration of the literature. Disability & Society, 29(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.800469

- Renwick, R., DuBois, D., Cowen, J., Cameron, D., Fudge Schormans, A., & Rose, N. (2019). Voices of youths on engagement in community life: A theoretical framework of belonging. Disability & Society, 34(6), 945–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1583551

- Richards, L., & Morse, J. M. (2012). Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. Sage.

- Rossi, P., Lipsey, M., & Freeman, H. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach. (7th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Simplican, S., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.008

- Stancliffe, R., Bigby, C., Balandin, S., Wilson, N., & Craig, D. (2015). Transition to retirement and participation in mainstream community groups using active mentoring: A feasibility and outcomes evaluation with a matched comparison group. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59(8), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12174

- Stickley, T., Crosbie, B., & Hui, A. (2012). The Stage Life: Promoting the inclusion of young people through participatory arts. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40(4), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2011.00703.x

- Tedrick, T. (2009). Growing older in Special Olympics: Meaning and benefits of participation—Selected case studies. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 33(3), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924780903148169

- Ward, K., Atkinson, J., Smith, C., & Windsor, R. (2013). A friendships and dating program for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A formative evaluation. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.01.022

- Ward, K., Windsor, R., & Atkinson, J. (2012). A process evaluation of the friendships and dating program for adults with developmental disabilities: Measuring the fidelity of program delivery. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.016

- Wilson, N., Stancliffe, R., Gambin, N., Craig, D., Bigby, C., & Balandin, S. (2015). A case study about the supported participation of older men with lifelong disability at Australian community‐based Men’s Sheds. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(4), 330–341. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1051522

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. (4th Ed.). Sage.