Abstract

The evolving social contract between science and society has led to increasing calls, inside and outside science, for greater public accountability on the part of scientists and engineers, which has focused more attention on their responsibilities to the larger society. Yet, there is no consensus on what those responsibilities are or should be. The American Association for the Advancement of Science has launched a project to inform global discussions of those responsibilities by gathering data on what scientists and engineers view as their broader responsibilities. Some results from a preliminary questionnaire are presented in this essay along with plans to build on this initial effort.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is engaged in a three-part effort to expand existing knowledge that addresses the social responsibilities of scientists and engineers. The first part has been completed (Wyndham et al. Citation2015), and the results are the focus of this essay. The second and third parts will be discussed at the conclusion of the paper.

Overview of the context of the study

During the past four decades, a considerable amount of professional and public attention and resources have been dedicated to examining the content and boundaries of researchers’ professional responsibilities. In the USA, legislation has been enacted, state and federal regulations have been implemented, research institutions have established policies on the conduct of research, and professional societies have adopted codes of ethics/conduct on what constitutes good and ethical research practices. Similar steps have been taken in other parts of the world and a number of international bodies have addressed the matter as well. Moreover, the field of “research on research integrity” has expanded, as funding for such research has become more widely available. As a result, there is a substantial body of scholarship about the factors affecting scientists’ responsibilities related to research practices.

The same cannot be said, however, with regard to the social responsibilities of scientists and engineers. There is no consensus inside or outside the scientific community on the nature of such responsibilities – what they are, how they can be operationalized, to whom they are owed and in what circumstances (Glerup and Horst Citation2014). Yet, calls for scientists and engineers to accept and fulfill such responsibilities are widespread, both from within and outside science and engineering. Consequently, the “negotiation of responsibility between practicing scientists, innovators and the outside world remains an important and contested area of debate to this day” (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1569). There is, however, sparse empirical work to guide those negotiations.

The search for and uses of scientific knowledge and innovation are not without consequences. People recognize the enormous power and influence of expert knowledge on their lives, and while they often look to scientists and engineers for authoritative answers to complex problems, they are also leery of the sometimes unwelcome effects new knowledge brings, leading to a growing recognition of the need to consider the societal benefits and risks/harms generated by knowledge and its applications. Furthermore, as noted by others,

science and society … have each invaded each other's domain, and the lines demarcating the one from the other have virtually disappeared … . Experts must respond to issues and questions that are never merely scientific and technical, and must address audiences that never consist only of other experts … . science must now be sensitive to a much wider range of social implications. (Gibbons Citation1999, C82)

Today “Science … has to meet a series of public expectations, not only about its products but also about its processes and purposes” (Jasanoff Citation2010, 696). Scientists and engineers are being held accountable not only for how they apply their knowledge and skills to social problems, but also for their decisions about what problems to address.

In this evolving science and society environment, no society can “afford to educate its future scientists to engage in research without ever understanding how the methods and techniques they use or the knowledge they generate can benefit [or harm others] or how to influence democratic decision making” (Declaration on the Civic Responsibility of Higher Education, Campus Compact Citation2000, 1). Others have stressed that, “If science is going to serve fully its societal mission in the future, we need to both encourage and equip the next generation of scientists to effectively engage with the broader society in which we work and live” (Leshner Citation2007, 161). The need for greater emphasis on social responsibility in the education and training of scientists and engineers is compelling, but it should be informed by more conceptual and empirical study of how scientists and engineers view their responsibilities to society and translate them into specific roles and responsibilities. This need is what drives the AAAS effort described below.

The empirical gap

The existing literature reviewed by the AAAS staff related to the social responsibilities of scientists and engineers can be characterized as follows: (1) editorials or opinion pieces on the authors’ views of the social responsibilities of scientists and/or engineers; (2) literature that attempts to probe the concept of “social responsibility” in depth, where the authors were mostly academic scholars; and (3) studies of what scientists or engineers believe are their broader responsibilities to society, using various methods to collect data. It is the third category that most closely mirrors the focus of this study.

The literature search revealed a paucity of empirical research that probes scientists’ or engineers’ views about their social responsibilities, and where they do exist, the numbers of those studied were, with one exception, all in the hundreds or fewer. We found one study in 1998 and another in 1999 that explicitly asked about scientists’ social responsibilities. The study population of the former was “distinguished scientists” in Croatia cutting across six scientific disciplines, including engineering. A mail survey was sent to 769 persons, and 320 of the returned surveys were used for the analysis (Prpic Citation1998). The 1999 study interviewed 10 senior molecular geneticists based in New Zealand on “their perceptions of the ethical and social implications of genetic knowledge” (Nicholas Citation1999, 515). The largest of the studies in terms of subjects was one commissioned by the Wellcome Trust that was completed in 2000. It involved face-to-face interviews with a random sample of over 1500 research scientists in the UK. The study elicited views from scientists on their responsibility to “becoming involved in communicating their research to the public, and to increase dialogue on the social and ethical implications of this research” (MORI Citation2000, 3).

A study published in 2005 began with the premise that, “Knowing how scientists perceive their relationships with other stakeholders is of great importance in designing and evaluating strategies to facilitate the fruitful participation of all concerned”, and involved interviews with 20 academic geneticists (Matthews, Kalfoglou, and Hudson Citation2005, 161). A fourth study, reported in 2009, examined the views of 45 academic life scientists, including postdoctoral fellows and graduate students, about “accountability and the ethical and societal implications of research” (Ladd et al. Citation2009, 762). The methods used were one-on-one telephone interviews and focus groups. The final study referenced here was published in 2014, and involved a survey of 326 engineering students at four US universities. They were surveyed each year while enrolled until graduation and one final time 18 months after graduation, and were asked specifically about their attitudes toward four types of “public welfare” concerns, including “social consciousness” (Cech Citation2014, 51).

It is not possible to review in detail here the above studies. It is also not possible to confidently generalize from them – they reflect different understandings of “social responsibility” by those studied; the number of subjects per study is relatively small, with only one exceeding 350 scientists/engineers; some focus on a range of disciplines, while others include only a single discipline or a subset of a discipline; they use different data collection methods and their analyses focus on a range of research questions, some overlapping and some very different; none was intended to be global in the selection of subjects; and generalizing from a total of six studies scattered over 16 years, when much about the social context of science and engineering has changed, does not seem particularly useful. In light of this limited group of studies, the AAAS decided to conduct its own.

The AAAS project

Beginning in April 2013, an online questionnaire was posted to gather scientists, engineers and health professionals’ views on their responsibilities to society. The study sought to learn how they view the nature and scope of their “social responsibilities”, and to identify any apparent similarities and differences in perspectives according to multiple demographic variables. Because this was an exploratory study, a convenience sampling process, or non-probability sample, was used. This made sense in light of the mixed results of the few studies discussed in the previous section and the belief that one could not draw useful findings from them in the aggregate. By using convenience sampling, we sought to gather as many responses as possible over a predetermined period of time from our target group – scientists, engineers and health professionals. This was less costly and time-consuming than conducting a randomized probability sample of our target population – the global community of scientists, engineers and health professionals. Moreover, there is not an adequate literature on the topic of social responsibility to serve as a useful guide to designing such a study. That is why the AAAS is planning to follow up on the work reported here (see below). Of course, convenience sampling has critical limitations that we fully acknowledge. It is not representative of the target population writ large, so one cannot extrapolate from the sample to make generalizations about the larger population. But that was never a goal of this pilot. Convenience sampling is also inherently biased, in that it attracts respondents who are self-selected, inevitably leaving out members of the target population whose views are likely to be more diverse. This can lead to under- or overrepresentation of particular groups in the sample. In this study, for example, those responding were substantially over-represented from countries in the West, and certain disciplines were over-represented (the life and physical science constituted 68% of those responding) while others were under-represented (see Table A7). Nevertheless, for an exploratory study such as this, convenience sampling can be an effective tool for collecting some basic data that can subsequently guide the development of a more rigorous sampling methodology.

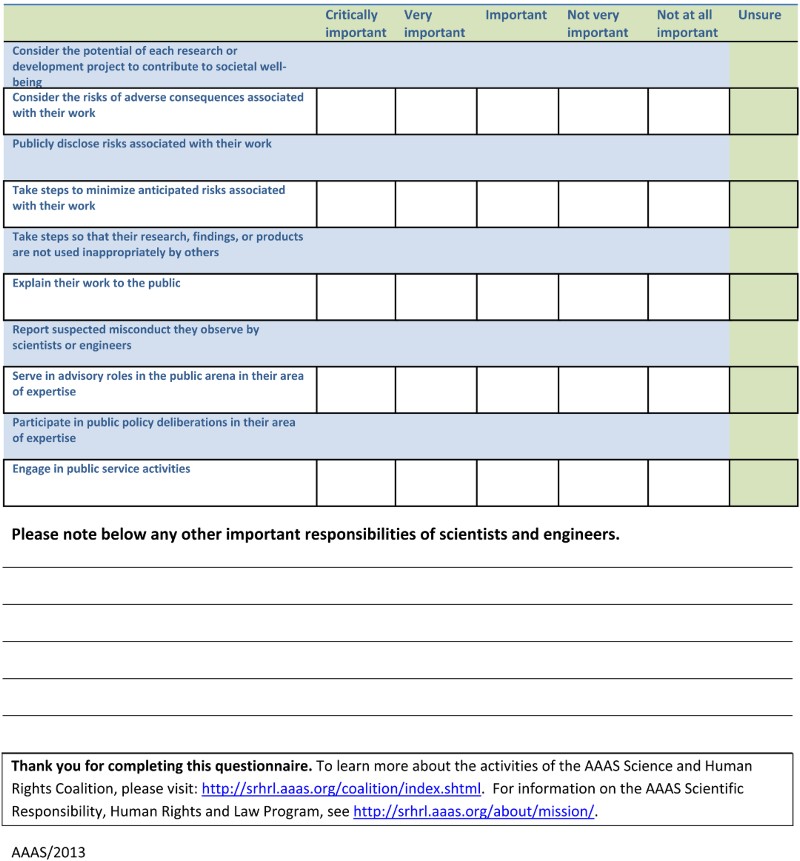

The questionnaire (see Appendix 1) began with a set of background/demographic questions intended to explore links between demographic variables and how respondents defined and assessed their responsibilities and also to help determine how effectively our dissemination effort captured the views of a diverse global group of scientists, engineers and health professionals. The seven demographic questions covered: field or discipline of work; sector of work; primary source of funding; gender; age; the country in which respondents received their highest degree and the country in which they spent most of their professional career (some descriptive data are included Appendix 2). In total, 2670 completed questionnaires were received, and after data clean-up, we ended up with 2153 useable responses, including 509 (23.7% of the total) who answered an open-ended question – “Please note below any other important responsibilities of scientists and engineers”.

Following the demographic questions, respondents were asked to rate how important they considered specific behaviors using a 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from “Critically important” to “Not at all important”, and included an option for “Unsure”. Each behavior could be considered a responsibility of scientists and engineers, and is commonly addressed as such in the extant literature. The 10 behaviors were:

consider the potential of each research or development project to contribute to societal well-being;

consider the risk of adverse consequences associated with their work;

publicly disclose risks associated with their work;

take steps to minimize anticipated risks associated with their work;

take steps so that their research, findings or products are not used inappropriately by others;

explain their work to the public;

report suspected misconduct they observe by scientists or engineers;

serve in advisory roles in the public arena in their area of expertise;

participate in public policy deliberations in their area of expertise;

engage in public service activities.

The responses are reported in Table A8 (Appendix 3). The range of importance attributed to the 10 behaviors went from a low of 82.4% to a high of 95.8%. What stands out is that more than three quarters of the 2153 respondents rated all 10 of the behaviors as important. However, since this was a convenience sample, where anyone with access to the Web could complete the questionnaire, it is likely that the numbers reflect a tendency on the part of those responding to be especially interested in/committed to a critical role for social responsibility as it pertains to the behavior of scientists and engineers.

A selection of findings

Among other findings revealed by the data collected are the following:

Gender did not produce any significant differences across each of the 10 behaviors.

The younger the respondents, the greater their concern to “explain their work to the public”; the older the respondents, the greater their concern to “report suspected misconduct they observe by scientists or engineers”.

Pattern of responses to the scaled questions was generally similar among those in the health sciences and social/behavioral sciences relative to responses between any of the other disciplines.

Respondents in the health sciences were most likely to consider a responsibility “important”; engineers were least likely.

Responses to the scaled questions were similar among respondents from Europe, North America and the Pacific; respondents from Africa, Arab States, Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean answered questions similarly to each other but differently from respondents in the previously mentioned regions.

In the open-ended question, an area not covered by the scaled questions – teaching and mentoring – was mentioned by 23% as a responsibility with societal implications.

In the open-ended question, those in the education sector were most likely to respond; students/post-docs were least likely.

In the open-ended question, respondents answering were most likely to be over the age of 50 (53%), with the response rate decreasing as the age of respondents decreased.

Next steps

As noted, the results cannot be generalized beyond the study sample. Nevertheless, the results do suggest potential research questions and, as such, offer guidance for the development of a more robust survey. The second part of the AAAS effort is to design and pre-test a survey to generate data that will enable us to generalize broadly about the views of scientists and engineers on their social responsibilities. The third part will be to launch the survey globally in late 2016.

One of the shortcomings of this pilot effort is that while it addresses what scientists and others view as their social responsibilities and the level of importance they ascribe to them, it does not reveal anything about why they hold those views. Hence, it has pointed to a set of questions to incorporate in the follow-up survey. These include the following:

For scientists who give little weight/great weight to their responsibilities to society, what influences that decision?

What are the sources of scientists’ views of their social responsibilities and how do they differ across demographic variables?

What factors in their professional work (e.g. institutional structures, national legal and ethics frameworks, disciplinary codes of ethics) influence scientists’ perceptions of their social responsibilities?

How are scientists’ understanding of their social responsibilities shaped by how they view their relationship to the larger society – local, national or global?

In ranking the importance respondent give to the 10 behaviors listed in the questionnaire, they were all rated as particularly important. That is a very coarse finding that needs further refinement, which should presumably occur when a larger probability sample is surveyed. In that context, a new question to be asked is:

How do scientists establish priorities among their professional and social responsibilities?

Finally, based on the responses to the open-ended question, we will likely expand beyond the 10 behaviors used in this study to include questions related to teaching, mentoring and others. We also believe it would be of value to increase our understanding of what factors stand in the way or facilitate scientists’ ability to pursue and carry out those responsibilities they identify as most important, leading to the following question for the new survey:

What opportunities and challenges do scientists identify as affecting their ability to fulfill their social responsibilities effectively?

The results of the survey and analysis should inform discussions among scientists and engineers about the normative forces that underlie their social responsibilities, leading, perhaps, to greater reflection on the place of social responsibility in professional codes of ethics and similar such documents. It may help to clarify public expectations about the role of scientists and engineers in societal matters. The data might even provide a major “data point” for considering specific recommendations on the nature and scope of those responsibilities, resulting, perhaps, in statements of principle and/or best practices. For those interested in the oversight of science and technology as a policy matter (e.g. policy-makers, legal scholars, scholars in research policy), the data may be useful for informing the evaluation of options for exercising such oversight. Finally, the study may point to ways that social responsibility can be integrated into the education and training of scientists and engineers.

[This essay summaries and relies heavily on the full study report that can be accessed and downloaded at http://www.aaas.org/report/social-responsibility-preliminary-inquiry-perspectives-scientists-engineers-and-health.]

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jessica Wyndham and Josh Ettinger for their assistance in reviewing this manuscript.

Notes on contributor

Mark S. Frankel is director of the Scientific Responsibility, Human Rights and Law Program at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). He leads the Association's work related to ethics, law and human rights.

References

- Cech, Erin A. 2014. “Culture of Disengagement in Engineering Education?” Science, Technology and Human Values 39: 42–72. doi: 10.1177/0162243913504305

- Declaration on the Civic Responsibility of Higher Education, Campus Compact, 2000, pp. 1–2. The Campus Compact is a coalition of nearly 1,200 U.S. college and university presidents. Accessed July 15, 2015. http://www.compact.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/Presidents-Declaration.pdf.

- Gibbons, Michael. 1999. “Science's New Social Contract with Society.” Nature 402: C81–C84. doi: 10.1038/35011576

- Glerup, Cecilie, and Maja Horst. 2014. “Mapping ‘Social Responsibility’ in Science.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1: 31–50. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.882077

- Jasanoff, Sheila. 2010. “Testing Time for Climate Science.” Science 328: 695–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1189420

- Ladd, J. M., M. D. Lappé, J. B. McCormick, S. M. Boyce, and M. K. Cho. 2009. “The ‘How’ and ‘Whys’ of Research: Life Scientists’ Views of Accountability.” Journal of Medical Ethics 35: 762–767. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.031781

- Leshner, Alan I. 2007. “Outreach Training Needed.” Science 315: 161. doi:10.1126/science.1138712.

- Matthews, Debra J. H., Andrea Kalfoglou, and Kathy Hudson. 2005. “Geneticists’ Views on Science Policy Formation and Public Outreach.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 137A: 161–169. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30849

- MORI. 2000. “The Role of Scientists in Public Debate.” Accessed July 15, 2015. www.ipsos-mori.com/Assets/Docs/Archive/Polls/wellcome-exec.pdf.

- Nicholas, B. 1999. “Molecular Geneticists and Moral Responsibility: ‘Maybe If We Were Working on the Atom Bomb I Would Have a Different Argument.” Science and Engineering Ethics 5: 515–530. doi: 10.1007/s11948-999-0052-3

- Prpic, K. 1998. “Science Ethics: A Study of Eminent Scientists’ Professional Values.” Scientometrics 43: 269–298. doi: 10.1007/BF02458411

- Stilgoe, Jack, Richard Owen, and Phil Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Poicy 42: 1568–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

- Wyndham, J. M., R. Albro, J. Ettinger, K. Smith, M. Sabatello and M. S. Frankel. 2015. Social Responsibility: A Preliminary Inquiry into the Perspectives of Scientists, Engineers and Health Professionals. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. Accessed July 19, 2015. doi:10.1126/srhrl.aaa9798.

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

Scientists’ and engineers’ perspectives on their responsibilities

The purpose of this short questionnaire is to learn how scientists and engineers view the nature and scope of their responsibilities. The questionnaire is anonymous and should take no more than 5–10 minutes to complete. The data gathered will be used to inform an in-depth survey to be conducted later this year. Your willingness to provide input is greatly appreciated.

This is a joint activity of the Ethics and Human Rights Working Group of the AAAS Science and Human Rights Coalition and the AAAS Program on Scientific Responsibility, Human Rights and Law.

To complete this questionnaire online, go to: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/SciEngResponsibilities-Questionnaire. Paper copies may be mailed to Jessica Wyndham, AAAS Scientific Responsibility, Human Rights and Law Program, 1200 New York Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20005, USA

Background Information

A. In which field or discipline do you work? (e.g. astrophysics, mechanical engineering, psychiatry) _____________________________________________________________________________________

B. In what sector do you work?

□ Not currently employed

□ Student/Post-doc

□ Education (all levels)

□ Government

□ Industry/Commercial sector

□ Non-profit

□ Independent practice/Self-employed

□ Other _____________________

C. What is the primary source of funding for your work?

□ Government

□ Non-profit (e.g. Foundation)

□ Industry/Commercial sector

□ Not applicable

□ Other _____________________

D. Gender: __Female __Male

E. Age: __under 35 __35–50 __ over 50

F. In what country did you receive your highest degree? _______________________________________

G. In what country have you spent most of your professional career? __________________________

Questionnaire

Please indicate with an “x” in the relevant box how important you believe the following responsibilities are in the work of scientists and engineers:

Appendix 2. Questionnaire responses – demographics

Table A1. Sector.

Table A2. Funding.

Table A3. Age.

Table A4. Gender.

Table A5. Region of Highest Degree.

Table A6. Region of Professional Career.

Table A7. Discipline.

Appendix 3. Importance of the 10 Behaviors

Table A8. Ratings of the importance of the 10 behaviors.