ABSTRACT

Objects of responsibility reflections in responsible research and innovation (RRI) emerge at the intersection of projections about future technology and future society. They intersect in a more or less distant future that can be called ‘technology futures’. These are the main medium of assigning social, ethical, and cultural meaning to new and emerging science and technology (NEST) fields – and it is exactly this meaning which gives rise to public, political, and ethical debates on NEST. This assignment of meaning is, it is argued, the most upstream point reachable in RRI: it is simply the origin of respective debates and reasoning. As such, initial assignments of meaning can have high influence on subsequent debate, for example, in determining what is regarded as chance or risk. This perspective gives rise to a major conclusion concerning the scope of responsibilities in RRI. While usually the responsibility for the possible future consequences of NEST is made an issue to RRI, I will argue for extending the scope of responsibility: the assignment of meaning to NEST must itself be made an object of responsibility. This extension has consequences for the roles of technology assessment in RRI.

1. Motivation and overview

The debate on responsible research and innovation (RRI) (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; van den Hoven et al. Citation2014) has so far been focusing on a comprehensive understanding of innovation (Bessant Citation2013), on participatory processes to involve stakeholders, citizens, and affected persons in design processes and decision-making (Foley, Bernstein, and Wiek Citation2016; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013), on understanding responsibility in industry (Hemphill Citation2016; Iatridis and Schroeder Citation2016), and on ethical conceptions of responsibility (Gianni Citation2016; Grinbaum and Groves Citation2013; Pellé Citation2016). Furthermore, considerable effort has been spent to identify specific characteristics of RRI and to distinguish it from established approaches to reflection on science and technology, such as technology assessment (TA, Grunwald Citation2009), value sensitive design (van den Hoven Citation2013), science, technology, and society (STS) studies (Woodhouse Citation2014), and applied ethics (Chadwick Citation1997). Several analyses have been presented for profiling RRI among these approaches (Fisher et al. Citation2015; Grunwald Citation2011a; Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013; von Schomberg Citation2012).

These topics are without a doubt central to the further development of RRI. However, there are also other aspects which might be crucial and should not be neglected. A question that has attracted hardly any attention so far is how the issues and challenges to be analyzed, discussed, and reflected in RRI – in short, the objects of responsibility reflections – come into being. The main motivation for the analysis given in this paper is the supposition that this question hints at some uncharted territory for RRI which should be investigated because of both analytical and practical reasons. The goal of this paper is to undertake some first steps toward exploring this uncharted territory (Grunwald Citation2016).

The objects of responsibility reflections in RRI emerge at the intersection of two different prospective exercises. On the one hand, the technology-induced and prospective consideration of the scientific advance provides society with imaginaries of possible technologies of the future. On the other hand, there are prospective ideas, attitudes and perspectives but also expectations, hopes, and fears concerning the future of humans and society, e.g. in the context of the grand challenges or with respect to the further development of the economy, of law, and of social values. Both prospective trains of thought intersect in a more or less distant future, resulting in prospective considerations of possible innovation paths, of possible problem solutions provided by the technological advance, of possible products and services, and of possible implications and consequences of their diffusion, use, and disposal. This intersection is described by the concept of ‘technology futures’ which has been developed elsewhere (Grunwald Citation2012). These technology futures constitute the main medium by which social, ethical and cultural meaning is assigned to ongoing new and emerging science and technology (NEST) scientific research and development (van der Burg Citation2014) – and it is exactly this meaning which gives rise to ethical, political, and public debates (Sect. 2; cp. Grunwald Citation2016 for case studies).

Thus, the assignment of meaning is the most upstream point reachable in public and ethical debates on NEST at all – it is simply their origin. This perspective gives rise to a major conclusion concerning the scope of responsibilities to be made object of ethical reflections on NEST (Sect. 3). While responsibility for future consequences and impacts of NEST is often taken to be the starting point in RRI (Grinbaum and Groves Citation2013), I will argue for extending the scope of responsibility: the construction of the intersections mentioned above in form of technology futures and the correlated assignment of meaning as the origin of RRI issues and debates must also be made an object of responsibility (Grunwald Citation2016). This is because the creation and dissemination of meaning of NEST may heavily influence debates on NEST.Footnote1 The meaning assigned could, for instance, determine what will be regarded as chance or risk, what will be included and excluded in the debate, and which kind of innovation and application areas will be highlighted.

This conclusion results in an obligation to ask for the subjects of responsibility: which actors are responsible or could be made responsible for the assignment of meaning to NEST, how far does this understanding of responsibility extend, and what can be said about its limitations? Because a comprehensive analysis would go far beyond the scope of this paper, I will focus on the roles of TA in this respect (Sect. 4). If technology futures as means of assigning meaning to NEST are made object of responsibility, this has consequences for TA because TA frequently operates closely with technology futures. In this operation, different roles can be distinguished: TA as producer of technology futures, as user of technology futures and as observer of the production and communication of technology futures and their consequences. This diversification in turn reveals different roles of TA in debates on responsibility, and it suggests that there are different forms of accountability for TA itself. In this way, it is possible to develop a more differentiated picture of the relations between TA and RRI. The paper concludes with some proposals for next steps of research.

2. Creating and processing NEST meaning: the hermeneutic circle

The major issue of this paper is how topics and objects of responsibility reflections in RRI come into being, how the themes and questions are created and communicated, and how they might impact the subsequent debate and reasoning they motivated. The rationale is to ask for responsibilities and accountabilities in the earliest stage of the emergence of ethical, political, and public debates on NEST, as close as possible to their origin (Sect. 3). Analysis and conclusions are based on four observations:

(1) Ethical and public debates in the field of NEST do not focus on those sciences and technologies as such. A purely scientific breakthrough, a huge experimental success in lab research or a fast advance in engineering do not give rise to ethical and public debates per se. They may be scientifically or technologically fascinating but will not find resonance in ethics or in society unless a further step is taken: it is only the sociotechnical combination of scientific and technological advance or projections, on the one hand, and their possible societal consequences and impacts, on the other, that trigger debates on the responsibility of NEST (Grunwald Citation2016). For those debates to arise at all, the respective NEST developments such as synthetic biology, human enhancement, genome editing, or robotics must rather show relevant meanings (van der Burg Citation2014; cf. also Jasanoff and Kim Citation2015) in ethical, cultural, economic, social, or political respects.Footnote2 Only then will questions warise such as what might be in store for contemporary or future society, what might be at stake in ethical, political, or social terms, and what the NEST developments under consideration could mean in different respects for the future of humans and of society (e.g. Hurlbut and Tiroshi-Samuelson Citation2016). Thus, it appears obvious that there is a need for investigating explicitly the issue of how these sociotechnical meanings are created and assigned to specific NEST developments, what their contents are, how they are communicated and disseminated, what consequences such assignments of meanings have for the subsequent debates and possible consequences.

(2) A large body of recent literature (e.g. Fiedeler et al. Citation2010; Hurlbut and Tiroshi-Samuelson Citation2016; Jasanoff and Kim Citation2015; Zülsdorf et al. Citation2011) legitimates the view that a major mechanism of assigning meaning to NEST developments consists of telling stories about their possible future impact and consequences, including their expected benefits and risks regarding the future development of society, humankind, or individual life.Footnote3 In these futures, projections of new technology intersect with future images of humans and society, often in a purely hypothetical and thus also speculative manner:

Those anticipations are meaning-giving activities, and their function is to prevent choices being taken blindly, or on the basis of too narrow fantasies of future actions which focus only on a sub-selection of possible follow-up actions and ignore significant groups of stakeholders. (van der Burg Citation2014, 102)

(3) The assignment of meaning to a NEST development by relating it to future stories can take place at a very early stage of development. Thus it can strongly mold the debate’s further development by helping to set its initial framings. Whether, for example, enhancement technology is assigned the meaning of offsetting inequalities in the physical and mental attributes of different humans and thus of leading to more fairness, or whether it is supposed to be used to fuel the competition for influential positions in the sense of promoting super-humans, illustrates the great difference. This example suggests that the meaning associated with a technology – and therefore the assignment of that meaning – could heavily influence public debates and, furthermore, that it could be crucial to public perceptions and attitudes, for instance by highlighting particular framings of what is regarded as chance and what is regarded as risk.Footnote4 Another example is the assignment of meaning to synthetic biology by Craig Venter, who framed it in terms of solving the world’s energy problem. Such assignments of meaning can be viewed as interventions. Although such interventions rarely if ever fix the meaning of the NEST under consideration, since that meaning will be contested from the very beginning, they may nevertheless have a tremendous impact on how subsequent debates are conducted. As already indicated, they can potentially influence which arguments and framings are foregrounded, which fundamental distinctions are dominant, which application fields will be discussed, and so forth. At the end of the day, the influence that the assignment of meaning may have on subsequent and ongoing debates may even prove to be decisive for social acceptance or rejection of the technology in question, as well as for policy decision-making on the promotion or regulation of a particular form of research and development. Thus, the potentially high social and political impact of assigning meaning to NEST developments is what motivates this paper’s attempt to shed more light on the processes of creating, assigning, and communicating technology futures as meaning-giving entities as well as on the emerging controversies that may stem from these meanings. Such controversies are analogous to ‘contested futures’ (Brown, Rappert, and Webster Citation2000) in that the original and ongoing assignments of meaning will themselves be potentially contested. This observation thus extends the theoretical call for better understanding of how meaning is assigned to NEST given in the first observation above and it adds a second practical call.

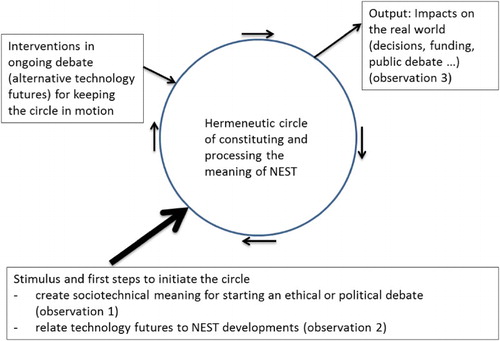

(4) Realizing both the theoretical and the practical call requires uncovering processes of assigning meaning to NEST developments, which involves considerable conceptual and methodological challenges. The assignments of meaning via techno-visionary futures involves interpretations, associations, and speculations, all of which are epistemologically precarious in nature and for which strategies of objective proof are lacking (Shelley-Egan Citation2011). For the most part, it is extremely difficult if not impossible to say anything about the validity and reliability of such meaning-giving propositions. This raises questions about how to provide well-reflected orientations for society and decision-makers involved in NEST debates and policies. While the provision of orientating knowledge is arguably at the core of RRI, when there is a lack of valid knowledge, traditional approaches based on consequentialist reasoning no longer work (Grunwald Citation2016) and may even lead to a paradox (Shelley-Egan Citation2011). Thus, for RRI and TA to substantially contribute ‘to achieve better technology in a better society’ (Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995) by analyzing meaning-giving processes, new approaches must be developed. The hermeneutic turn to meet this challenge (Grunwald Citation2014; cf. Nordmann Citation2014; van der Burg Citation2014) seeks to contribute to the development and application of a new type of reasoning in order to provide policy advice in debates on technology futures beyond traditional consequentialism. Its objective is to uncover the mechanisms and to investigate the functioning of the hermeneutic circle of processing the meaning of a specific NEST in emerging and ongoing ethical, political, and public debates on NEST (see ).

Figure 1. The creation of meaning for NEST in a hermeneutic circle, including its stimulus. (source: Grunwald Citation2016, modified).

The process of assigning meaning to NEST and of developing this meaning further in corresponding debates can be modeled as a hermeneutic circle (). The first ideas that relate technology futures to ongoing research and development constitute the initial stimulus which starts processing this circle (Sect. 3). The circle continues to move through a series of communicative events, by which the meanings proposed are communicated, controversially discussed, supplemented, or modified. The debate on nanotechnology (Grunwald Citation2011b) has been used as an example for illustrating such a hermeneutic circle and its development over 10–15 years. The focus and novel perspective of this paper is on the first steps which motivate and initiate the circle. For nanotechnology, Richard Feynman’s famous lecture (Citation1959) or the book Engines of Creation (Drexler Citation1986) might have been such first steps or at least very early steps in creating meaning for nanotechnology and in starting the respective hermeneutic circle.

According to philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer (Citation1975), the hermeneutic circle is an iterative process. By processing the circle it is possible to gain a new understanding of the issue under consideration. Understanding in this sense happens in the medium of language and through conversations with others. Thus, the meaning of a specific NEST under consideration will change during processing the circle. At a specific point in time and within a particular discourse community, an agreement might be reached that represents a new understanding. However, this new meaning will again be subject to further challenges by interventions from other authors. Thus, the circle develops as a spiral of ongoing change, continuous modification, and learning.

emphasizes the high influence of an initial stimulus.Footnote5 At the very beginning of respective debate, facts are created that can advance communication and provide guidance. The meaning and framing given in the stimulus can decisively mold the ensuing debate while the first framing can, it is argued here, only be gradually modified by proposing alternative meanings in the subsequent turns of the hermeneutic circle. By bringing technology futures together with technological research and development, the latter are placed in a social frame of meaning, which develops its own dynamics in the hermeneutic circle. This process can be self-reinforcing and lead, for example, to initial research funding and sometimes eventually to massive investments being made in the affected field, and in this way to important real consequences for the agenda and the research process of science. Alternately, the framework of meaning that was initially advanced may of course be challenged, strongly modified, or even changed into its opposite, leading to social resistance and rejection. Self-fulfilling as well as self-destroying narratives (Merton Citation1948) about technology futures are the extremes of possible developments which could emerge out of the hermeneutic circle.

Clarification of the workings and mechanisms of the hermeneutic circle (Gadamer Citation1975), in particular of its beginnings, is therefore a central task to allow to better understand the real output and its dependence on the inputs as well as on the respective status of the circle in as transparent a manner as possible, for instance, in the framework of ethical and public debates on NEST. This observation leads to a proposal for new avenues of future research (Sect. 5).

Focusing on the initial stages of the hermeneutic circle in this paper means reaching the endpoint of the ‘upstream’ movement in STS, philosophy of technology, and TA which can be observed over the last approximately 10–15 years. Just as the RRI process is metaphorically understood as a river or stream in development from its source to its mouth, so has the focus of analysis, investigation, and assessment of NEST shifted from the end of the innovation process to its earlier stages (e.g. Liebert and Schmidt Citation2010; Macnaghten, Kearnes, and Wynne Citation2005). In this paper, the movement is pushed further upstream to the source of the ethical and public debates on NEST, thus completing it by considering its very first steps: the creation of sociotechnical meanings of NEST developments. Further movement upstream is not possible: there is simply no space further upstream to go.

3. Extending the scope of responsibility in RRI

While responsibility in RRI is generally understood as responsibility for the consequences of NEST developments that might arise later for humankind and society (Grinbaum and Groves Citation2013) now the assignment of meaning via technology futures enters the focus of responsibility – because, according to the preceding analysis, this assignment could have major impact. The point here is not what consequences NEST could have in the distant future and whether these consequences might be regarded responsible, but how a responsible handling of the creation and assignment of meaning can look today. This turn is similar to what Horner (Citation2007, 64) proposed: ‘Forecasters are accountable for their forecasts in the same way I may be held accountable for my promises’.

This consideration closes the circle in the hermeneutic approach. Instead of dealing with the anticipation of distant consequences in a more or less speculative mode (Nordmann Citation2007, Citation2014), the issue is how, why and wherefore, and on the basis of which diagnoses and ethical evaluations sociotechnical meaning of NEST is currently being created, assigned, and communicated. The proposal of extending the scope of responsibility in ethical and public debates on NEST accordingly is the major conclusion of combining the observations presented above. Obviously, it needs some more in-depth consideration.

The very idea of responsibility and responsibility ethics follows Max Weber’s distinction between the ethic of responsibility (Verantwortungsethik) and the ethic of ultimate ends (Gesinnungsethik) (Citation1946). In this distinction, responsibility is intimately related to a consequentialist approach. Taking over responsibility or assigning responsibility to other persons, groups, or institutions indispensably requires the availability of valid and reliable knowledge, or at least of a plausible picture of the consequences and impact of decisions to be made or of actions to be performed. The familiar approach of discussing responsibilities is to consider future consequences of an action (e.g. the development and use of new technologies) and then to reflect on these consequences and their impacts from an ethical point of view. This is also the customary understanding of the object of responsibility in RRI:

The first and foremost task for responsible innovation is then to ask what futures do we collectively want science and innovation to bring about, and on what values are these based? (Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013, 37)

The consequences of NEST that might occur in the future and that are the objects of consideration and assessment in RRI are frequently epistemologically precarious (e.g. Grunwald Citation2016; Shelley-Egan Citation2011), to a great extent, even bordering on speculation (e.g. Hansson Citation2016; Nordmann 2007). The lack of knowledge limits the possibility of drawing valid conclusions for responsibility assignments and assessments. Many, perhaps almost all, responsibility debates on NEST issues consider narratives about possible future developments involving visions, expectations, fears, concerns, and hopes which can hardly be assessed with respect to their epistemological validity (Grunwald Citation2016). It thus appears questionable whether consequentialism applied to more or less speculative consequences is at all sensible for NEST (Swierstra and Rip Citation2007). Consequentialism understood in this way threatens to fail because of the unavailability of reliable knowledge about the consequences.

However, this way of understanding responsibility tends to assume a consequentialist perspective that cannot answer to the uncertainty that characterizes the development of innovative techniques and technologies. RRI’s crucial issue, the one for which we make use of the criterion of responsibility, is exactly to provide an answer to the uncertainties that are implied in the complex relations between individual actions, social relations, and natural events. (Gianni Citation2016, 36)

(2) The creation and assignment of sociotechnical meaning to NEST takes place primarily at the beginning of or even before ethical and public debates occur and therefore can strongly influence them (). The history of the nanotechnology debate (Grunwald Citation2011b) clearly demonstrates the high impact of meaning-assigning activities involving speculative futures (such as the possible emergence of grey goo, of nanobots, and loss of human control over technology (Joy Citation2000)). For this reason, meaning-giving actions have to be viewed from the perspective of responsibility, independent of the uncertainty of our knowledge of the consequences. Assignments of meaning and its communication are communicative facts and interventions into a particular social constellation. This is also demonstrated by considering assignments of meaning by using technology futures from the viewpoint of action theory (Grunwald Citation2016):

assignments of meaning themselves are actions; the technology futures used in this context do not arise on their own but are constructed in social processes and have authors;

authors pursue their own goals and purposes: something is supposed to be achieved by creating and communicating technology futures for assigning meaning (cp. the debate on visioneering as an example, Cabrera Trujillo Citation2014);

realizing these goals and purposes requires appropriate means: texts, narratives, diagrams, images, works of art, films, etc. which have to be used in communicating the technology futures;

using these means constitutes an intervention in the real world and can have more or less far-reaching consequences (see observation 3 in Sect. 2 above), intended or unintended.

Obviously, the assignment of meaning by relating pictures of a societal future to the prospects of NEST is not independent from the content of the sociotechnical futures under consideration. However, the hermeneutic turn frees one from having to make assumptions of the probability or plausibility of those futures to eventually become reality. The ethical aspect concerning responsibility does not emerge from the fact that the debated futures might become reality, but rather merely from the fact that they are used to create and assign meaning. This difference might be difficult to understand and will have to be investigated further.

Technology futures are thus regarded not only as stories and narratives of possible future developments but also as expressions of today’s assignments of meaning according to today’s knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, diagnoses, and concerns – as today’s assignments with consequences for ongoing debates and decision-making (Grunwald Citation2014). The Control Dilemma (Collingride Citation1980; Liebert and Schmidt Citation2010) becomes relativized if we take the difference pointed to in the previous paragraph seriously – in that case, we would not talk about responsibility today for more or less speculative future consequences but rather we would consider consequences and impacts of meaning-giving activities for current practices. This extended view on responsibility does not fall under the dilemmatic structure and provides an additional perspective.

However, some relativizing thoughts quickly enter this argumentation. What does the assignment of meaning by attaching societal futures to technological prospects mean in the absence of consequentialist thinking in the traditional mode of TA? If the Control Dilemma really becomes obsolete, does the challenge it refers to perhaps only migrate to another place in ethical, political, and public debates on NEST? Is it sensible to discuss assignments of meaning via futures in the absence of assumptions about their plausibility or probability? Answering these questions and others will need more investigation and deliberation.

Another issue of concern might be the extent to which an author of techno-visionary futures assigning meaning to some NEST could be made responsible for consequences of his/her intervention. Obviously, such an author (please think, as an example, of Eric Drexler opening up dystopian views of nanotechnology or Bill Joy (Citation2000) re-opening and accentuating those views) cannot fully oversee the consequences of his/her intervention. All the authors of the hermeneutic tradition of reasoning mention this point. According to ongoing processes in the hermeneutic circle (), many things may happen and affect and modify the meaning assigned in an unforeseeable way and uncontrollable by the initiating author. However, responsibility as a concept is not only to be applied in case of full knowledge about consequences of an intervention. Rather, also in a field of (possibly high) uncertainty about consequences we can speak of responsibility in a meaningful way. However, we have to take into account the specific circumstances of assigning meaning to NEST. Because of the high uncertainty involved, modeling this type of responsibility in the tradition of virtue ethics has already been proposed (Sand Citation2016). This might be a conceptual solution; however, further research and reasoning seems to be needed to make this type of responsibility fully transparent.

Regardless, attributions of meaning and the communicative acts involved in them should accordingly be taken up as objects of responsibility reflections in RRI in addition to the possible or presumed consequences of NEST. While the traditional consequentialist picture focuses on possible future consequences of NEST it excludes another dimension of responsibility of RRI which this paper would like to shed more light on. The talk is about the responsibility for the manner in which sociotechnical meanings are created and attributed to the NEST fields. This extension of the object of responsibility is in line with the hermeneutic circle (): searching for meaning and its further development by processing the circle shows consequences not only in far futures but also during present debates and in present decision-making.

But in order to become able to do this we have to better understand how meanings are created, communicated, and attributed. We have to understand what is meant by these sociotechnical meanings and which associations they permit. In other words, we need a hermeneutic enlightenment of the production, attribution, dissemination, and deliberation of sociotechnical meaning in the hermeneutic circle and, in particular, of its inception and the initial stimulus ().

The following consideration shall illustrate this conclusion. In the customary self-descriptions of RRI as well as of TA, it is often stated that the benefits and risks of NEST have to be recognized as early as possible and made the object of reflection in order to be able to develop and use options for shaping developments. The purpose is to make the positive expectations come true and to minimize or avoid the negative ones (e.g. Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013). Such statements, however, assume that it has already been clarified what is regarded an opportunity and what is diagnosed being a risk of certain NEST. In order to be able to look for strategies achieving opportunities and minimizing risks, a relation must have already been established between some properties of the NEST under development and its potentials, on the one hand, and social issues which allow speaking of opportunities and risks, on the other. But how are such relations established, how do they emerge out of complex communication and debate, and on what do they depend? According to the first observation given in Sect. 2 above, the assignment of sociotechnical meaning by attaching technology futures to ongoing research is decisive here. This opens up the door for a new field of investigation (Grunwald Citation2014, Citation2016).

The proposed extension of the scope of responsibility does not make the established view of the future consequences of NEST obsolete. The imperative continues to be to gain an idea of the possible long-term effects of today’s RRI (Jonas Citation1984) and to reflect on the results according to the ethical standards of responsibility, inasmuch as this does not fall victim to the ‘epistemological nirvana’ mentioned previously. This traditional, consequentialist mode of RRI continues to be important, but according to the analysis given a further mode must be put alongside it: directing our view to the source of ‘socializing’ NEST by assigning sociotechnical meaning, which is a prerequisite for new technology becoming an interesting field to RRI in the first place.

4. Conclusions for TA

Scientific policy advice on science and technology issues has been provided for more than 50 years now. TA has been developing since the 1960s as an approach to explore possible unintended and negative side effects of technology, to elaborate strategies for dealing with them, and to provide policy advice (Bechmann et al. Citation2007; Bimber Citation1996; Grunwald Citation2015), to support shaping technology (Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995), and to contribute to public dialogue. Many concepts have been proposed, developed and, in some cases, put into practice. The issue of anticipatory governance (Barben et al. Citation2008) and the concept of real-time TA (Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002) have emerged at the borderline between TA and ‘science, technology and society studies’ (STS) which over the past decades have developed in more or less separate ways. More recently, many of these approaches have met in the conceptual debate on RRI and have brought in their different perspectives and experiences (e.g. Grunwald Citation2011a; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; van den Hoven et al. Citation2014; von Schomberg Citation2012).

Although these approaches share some similarities, there are also differences, one of them concerning the role of self-perception: do they view themselves as distant observers or as part of the game and pushing their own interventions? The traditional view of STS and the sociology of science has been characterised as follows:

The sociology of science is often accused of sitting on an epistemological fence (…). Although fence-sitting is still an honourable epistemic tradition, many in the field today enjoy camping out, not on fences, but on ‘boundaries’. (Webster Citation2007, 458)

TA has initially been conceptualized as policy advice (Bimber Citation1996; Grunwald Citation2009), which is still a strong motivation of large parts of TA.Footnote6 The objective is to support policy-makers (parliaments, ministries, authorities) with advice concerning political measures which could either influence the further development and use of technology or which themselves could be influenced by new technological developments and achievements. Frequently, policy advice in this sense is about adequate regulation (e.g. environmental or safety standards), changes in research and development funding (e.g. in the NEST fields), and political strategies towards sustainable development.

Participatory TA has developed approaches to involve citizens, consumers and users, actors of civil society, stakeholders, the media, and the public in different roles at different stages in technology governance (Joss and Belucci Citation2002), according to normative ideas of deliberative democracy. Participative TA procedures are deemed to improve the practical and political legitimacy of decisions on technology and should contribute to more robust decisions on technology facing divergent normative convictions and interests.

Building on empirical research on the genesis of technology (Bijker, Hughes, and Pinch Citation1987), the idea of shaping technology according to social expectations and values emerged. It motivated the development of several approaches, with Constructive TA (CTA) being the most influential one (Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995). The general idea is to address groups directly involved in the ‘making of technology’, such as engineers, developers, and planners in companies and publicly funded research and development centers. Ethical issues and social desires shall, according to this approach, be implemented in technology by enriching and orientating decision-making processes in the design and development phase of new technological systems, products, and services.

In each of these directions TA is not an external observer but part of the game – the advice provided being meant to help ‘achieve better technology in a better society’ (Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995). In particular, a shared conviction in TA and related activities is, based on early considerations of the relation between technology, society, and the public (Habermas Citation1970), that TA shall contribute to making technology and decisions on technology in a more democratic manner (e.g. von Schomberg Citation1999). Taking this seriously suggests that assigning meaning to NEST fields should also be subject to deliberative democratic debate given that it could have far-ranging consequences as stated above. Assigning meaning to NEST must neither be delegated to scientists or the science system alone nor to political decision-makers. On the contrary, there are strong arguments for the early involvement of societal actors, stakeholders, and citizens in order to expand the responsibility for RRI into a co-responsibility shared between science and society (e.g. Barben et al. Citation2008; Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995).

For our issue of the construction of meaning of NEST developments, this implies that the assignment of meaning should ideally be co-created and co-processed. The hermeneutic circle () of the process of creation and assignment of meaning should in other words be participatory, deliberative, and open to persons and groups with different perspectives. If, in this picture, the activities of visioneers (McCray Citation2013) constitute a stimulus that gets the hermeneutic circle started, then independent considerations and deconstructions as well as bringing alternative proposals for assigning meaning into the game should also be given impetus. Instead of narrowing down the assignment of meaning to a specific intervention, related e.g. to a specific vision, processing the circle should add criticisms of the initial vision and develop alternative proposals. This effect of widening the debate by bringing in alternative proposals to assign meaning by using other technology futures would seem to be necessary in order to allow a more democratic and open deliberation.

TA has been involved in NEST debates from their very beginning. It has and continues to contribute to several hermeneutic circles on the meaning of specific NESTs. For example, the Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag (TAB) conducted studies for the parliament on nanotechnology, brain research, synthetic biology, the converging technologies, human enhancement, and human-machine interaction. Each of these studies includes considerations of the meaning of the respective NEST for society. This meaning usually was closely related to technology futures – the intersections between projections of future technology and ideas of future society as described above. This small observation raises the question for the responsibility of TA in using assignments of meaning to NEST in its advising business. To come closer to answers to this question it seems useful to distinguish between roles of TA in creating NEST meaning by assigning technology futures:

TA as producer of technology futures, in order to gain orientation thereof. By generating technology futures as intersections of technological and societal projections and by outlining possible ways there, including their implications, advice for and enrichment of public debate and political decision-making are provided. This is a familiar approach of TA predominantly in more mature fields where building scenarios is possible (e.g. in the energy sector) while in NEST fields TA usually does not create its own futures.

TA as user of technology futures which were brought into the debate by other actors (e.g. by research institutes or think tanks). These could be used, e.g. in assessment processes to provide orientation as mentioned above. However, this has to happen in a cautious way to avoid the unquestioned adoption of implicit and opaque values and interests hidden in the futures used.

TA as a critic of existing assignments of meaning. In order to strengthen thinking about alternatives, TA often has to question specific assignments of meaning and to confront them with different proposals. These sometimes come from civil society organizations but sometimes have to be provided by TA itself. The role as critical analyst of proposals for assigning meaning (e.g. by visioneers) might be the most important one in the field of NEST.

TA as an observer of the production and communication of technology futures and their consequences, so to say as a neutral observer of technology debates to learn from them about, e.g. societal perceptions. In this mode of operation, TA considers the hermeneutic circle from outside and aims at learning from this position of an external observer. TA then can inform its audiences about the status of the respective debates and may draw conclusions against the expectations of its audiences.

This diversification reveals different roles for TA in debates on responsibility, with different forms of accountability for TA itself. In this way it is possible to develop a differentiated picture of the relation between TA and RRI. A more in-depth differentiation of types of responsibility and accountability of TA would be of high importance to the further conceptual and methodological development of TA in NEST fields.

5. Further perspectives – investigating the hermeneutic circle

At the heart of this paper is the hermeneutic circle () where NEST meaning is created and processed showing real-world consequences. Making the postulate of extending the scope of responsibility in RRI (Sect. 3) operable and clarifying the responsibility of TA in this context in a more in-depth manner needs scrutiny and empirical investigation. Two perspectives for future research will be highlighted in this concluding section: (1) research on biographies of NEST meaning, and (2) enlightenment of the hermeneutic constellation.

Biographies of NEST meanings and related technology futures are being processed in the hermeneutic circle – they are not well understood as yet (e.g. Groves et al. Citation2016). Their construction, communication, dissemination, assessment, adaptation to new framing conditions, public deliberation, and real-world impact raise a huge variety of research questions which can only be answered by giving interdisciplinary consideration to these aspects (Grunwald Citation2016). Investigating their emergence and dissemination by means of different communication channels and their possible impact on decision-making in the policy arena and other arenas of public communication and debate involves empirical research and reconstructive understanding as well. Innovative formats for improving communicative practice and for making it more transparent should be developable on the basis of this knowledge. Different and dynamic biographies of techno-visionary futures as assignments of NEST meaning can be analyzed taking recent NEST developments as cases of study. In particular, the story of the nanotechnology debate raises several questions and offers various opportunities for further research. There was a phase of unchallenged positive expectations followed by a phase of dystopian fears which then was followed by a phase of ‘defuturization’ (Lösch Citation2010) or ‘normalization’ (Grunwald Citation2011b). Uncovering the dynamics of these dramatic fluctuations in assigning meaning to nanotechnology could contribute to a deepened understanding of the social dynamics dealing with issues of meaning of NEST and of the creation and emergence of those meaning-giving narratives.

The hermeneutic constellation is the set of actors, objects, and framing condition which drives the hermeneutic circle. An analysis of this constellation in NEST fields seems promising for better understanding the functioning of the circle. It would include the analysis of the actor constellation (which actors, individuals as well as collectives belong to the authors; which perspectives, motives, and diagnoses motivate them; to which contexts, networks, policy groups, pressure groups, etc. can they be assigned?); the reconstruction of the purpose for which a specific technology future was designed; which diagnoses, values, and interests were being mobilized; and which utensils other than text (art work, diagrams, films, etc.) played a role in assigning meaning (Grunwald Citation2016). The recent history of synthetic biology provides some material for this type of research. There have been massive interventions by the mass media, in particular by activist Craig Venter, assigning specific meaning to this NEST field by relating it to the world’s energy crisis. Other stories focus on the ‘playing God’ or ‘dominion over nature’ issues related to the prospect of creating artificial life. It is still not transparent what these issues really mean and what they contribute to ongoing debate. Investigating these issues (and also others, e.g. the huge wave of films and movies which have been presented around synthetic biology in recent years) should help understanding how and why specific meanings are assigned by whom to NEST developments, how and why specific technology futures have been chosen and why specific utensils have been selected.

Researching these questions can partially build on existing work. Numerous analyses of the different NEST stories of the past 15 years have been published, and much data and insights are available. This allows for the conduct of meta-studies on the biographies of NEST using existing material. However, in order to better understand the hermeneutic circle and for TA and RRI to learn from this knowledge requires bringing together many pieces of knowledge that already exist under the presented conceptual perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Prof. Dr Armin Grunwald has been Full professor at Karlsruhe Technical University since 2007. He studied physics, mathematics and philosophy at the universities of Munster and Cologne, and obtained Diploma of Physics in 1983. He did his Graduate studies at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Cologne during 1983–1987. He received his Habilitation at the faculty of social sciences and philosophy of the Philipps-University Marburg in 1998.

He served as Systems engineer and project manager at Systems Research Laboratories GmbH (Cologne) during 1987–1991 (Software Engineering), and as Scientist at the Department of Systems Analysis of the German Center for Aerospace (DLR) during 1991–1995 (Technology Assessment). He also served as Vice director of the European Academy Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler during 1996–1999. He has been Director of the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis at the Research Centre Karlsruhe and full professor at Freiburg university since 1999, and Director of the Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag (TAB) since 2002. His research interests include: Concepts and methods of Technology Assessment, Ethics of Technology, Philosophy of Science, and Sustainable Development.

Notes

1. The recent debate on ‘Visioneering’ (McCray Citation2013; Sand Citation2016) has raised the question of the responsibility of the visioneers (Cabrera Trujillo Citation2014), which has a close relation to the issues of this paper.

2. While the concept of ‘sociotechnical imaginaries’ (Jasanoff and Kim Citation2015) considers the role of science and technology in collective visions of good and attainable futures that are then often used by policymakers (e.g. to legitimate research funding), the perspective in this paper is different. It looks at how societal visions, expectations, concerns or fears contribute to the assignment of meaning to new science and technology, which then can give rise to an ethical or political debate.

3. A further mechanism of the creation and assignment of meaning to NEST is how new sciences and technologies are defined and characterized. This mechanism is not addressed in this paper (see Grunwald Citation2016, Ch. 4).

4. This argument is in line with Cabrera Trujillo (Citation2014) stating that visioneering should be made the object of responsibility exactly because engineered visions could have huge consequences.

5. The activities of visioneers (McCray Citation2013) is one specific category of such a stimulus which gained specific awareness under responsibility aspects (Cabrera Trujillo Citation2014; Sand Citation2016; Simakova and Coenen Citation2013).

6. See, for examples, the activities of the members of the European Parliamentary Technology Assessment Network EPTA (www.eptanetwork.org).

References

- Barben, D., E. Fisher, C. Selin, and D. Guson. 2008. “Anticipatory Governance of Nanotechnology: Foresight, Engagement, and Integration.” The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies 3: 979–1000.

- Bechmann, G., M. Decker, U. Fiedeler, and B.-J. Krings. 2007. “TA in a complex World.” International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy 1: 4–21.

- Bessant, J. 2013. “Innovation in the Twenty-First Century.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 1–26. Chichester: Wiley.

- Bijker, W. E., T. P. Hughes, and T. J. Pinch, eds. 1987. The Social Construction of Technological Systems. New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technological Systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bimber, B. A. 1996. The Politics of Expertise in Congress: the Rise and Fall of the Office of Technology Assessment. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Brown, J., B. Rappert, and A. Webster, eds. 2000. Contested Futures. A Sociology of Prospective Techno-Science. Burlington: Ashgate.

- Cabrera Trujillo, L. 2014. “Visioneering and the Role of Active Engagement and Assessment.” Nanoethics 8 (2): 201–206. doi: 10.1007/s11569-014-0199-5

- Chadwick, R. F. 1997. Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics. London: Academic Press.

- Coenen, C. 2010. “Deliberating Visions: The Case of Human Enhancement in the Discourse on Nanotechnology and Convergence.” In Governing Future Technologies. Nanotechnology and the Rise of an Assessment Regime, edited by M. Kaiser, M. Kurath, S. Maasen, and C. Rehmann-Sutter, 73–88. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Coenen, C., and E. Simakova. 2013. “STS Policy Interactions, Technology Assessment and the Governance of Technovisionary Sciences.” Science, Technology & Innovation Studies 9 (2): 3–20.

- Collingride, D. 1980. The Social Control of Technology. London: Pinter.

- Decker, M., and M. Ladikas, eds. 2004. Bridges between Science, Society and Policy. Technology Assessment – Methods and Impacts. Berlin: Springer.

- Drexler, K. E. 1986. Engines of Creation – The Coming Era of Nanotechnology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Feynman, R. P. 1959. “Lecture held at the Annual Meeting of the American Physical Society, California Institute of Technology, December 12, 1959.” http:www.zyvex.com/nanotech/feynman.html.

- Fiedeler, U., C. Coenen, S. R. Davies, and A. Ferrari, eds. 2010. Understanding Nanotechnology: Philosophy, Policy and Publics. Heidelberg: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Fisher, E., M. O’Rourke, R. Evans, E. B. Kennedy, M. E. Gorman, and T. P. Seager. 2015. “Mapping the Integrative Field: Taking Stock of Socio-Technical Collaborations.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 2 (1): 39–61. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.1001671

- Foley, Rider W., Michael J. Bernstein, and Arnim Wiek. 2016. “Towards an Alignment of Activities, Aspirations and Stakeholders for Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 209–232. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2016.1257380

- Gadamer, H.-G. 1975. “Hermeneutics and Social Science.” Philosophy Social Criticism / Cultural Hermeneutics 2 (4): 307–316. doi: 10.1177/019145377500200402

- Gianni, R. 2016. Responsibility and Freedom. The Ethical Realm of RRI. London: Wiley.

- Grinbaum, A., and C. Groves. 2013. “What is “Responsible” about Responsible Innovation? Understanding the Ethical Issues.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 119–142. Chichester: Wiley.

- Groves, C., K. Henwood, F. Shirani, C. Butler, K. Parkhill, and N. Pidgeon. 2016. “The Grit in the Oyster: Using Energy Biographies to Question Socio-technical Imaginaries of ‘smartness’.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3: 4–25. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2016.1178897

- Grunwald, A. 2009. “Technology Assessment.” In Philosophy of Technology and Engineering Sciences, edited by A. Meijers, 1103–1146. Vol. 9 of the Handbook of the Philosophy of Science. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Grunwald, A. 2011a. “Responsible Innovation: Bringing Together Technology Assessment, Applied Ethics, and STS Research.” Enterprise and Work Innovation Studies 7: 9–31.

- Grunwald, A. 2011b. “Ten Years of Research on Nanotechnology and Society – Outcomes and Achievements.” In Quantum Engagements: Social Reflections of Nanoscience and Emerging Technologies, edited by T. B. Zülsdorf, C. Coenen, A. Ferrari, U. Fiedeler, C. Milburn, and M. Wienroth, 41–58. Heidelberg: AKA GmbH.

- Grunwald, A. 2012. Technikzukünfte als Medium von Zukunftsdebatten und Technikgestaltung. Karlsruhe: KIT Scientific.

- Grunwald, A. 2014. “The Hermeneutic side of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (3): 274–291. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.968437

- Grunwald, A. 2015. “Technology Assessment and Design for Values”. In Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design, edited by J. van den Hoven, P. Vermaas, and I. van de Poel, 67–86. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6970-0.

- Grunwald, A. 2016. The Hermeneutic Side of Responsible Research and Innovation. London: Wiley-ISTE.

- Guston, D. H., and D. Sarewitz. 2002. “Real-time Technology Assessment.” Technology in society 24 (1–2): 93–109. doi: 10.1016/S0160-791X(01)00047-1

- Habermas, J. 1970. Toward a Rational Society: Student Protest, Science, and Politics. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Hansson, S. O. 2006. “Great Uncertainty about Small Things.” In Nanotechnology Challenges: Implications for Philosophy, Ethics and Society, edited by J. Schummer and D. Baird, 315–325. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Hansson, S. O. 2016. “Evaluating the Uncertainties.” In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis, Logic, Argumentation & Reasoning, edited by S. O. Hansson and G. Hirsch Hadorn, 79–105. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Hemphill, T. A. 2016. “Responsible Innovation in Industry: A Cautionary Note on Corporate Social Responsibility.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (1): 81–87. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2016.1178896

- Horner, D. S. 2007. “Digital Futures: Promising Ethics and the Ethics of Promising.” ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society 37 (2): 64–77. doi: 10.1145/1327325.1327330

- Hurlbut, J. B., and H. Tiroshi-Samuelson, eds. 2016. Perfecting Human Futures. Transhuman Visions and Technological Imaginations. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Iatridis, K., and D. Schroeder. 2016. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry. The Case for Corporate Responsibility Tools. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Jasanoff, S., and S.-H. Kim, eds. 2015. Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Jonas, H. 1984. The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (German Original: Das Prinzip Verantwortung: Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M., 1979).

- Joss, S., and S. Belucci, eds. 2002. Participatory Technology Assessment – European Perspectives. London: Westminster University Press.

- Joy, B. 2000. “Why the Future Does not Need Us.” Wired Magazine, no. 8.04, p. 238–263.

- Liebert, W., and J. Schmidt, eds. 2010. “Collingridge’s Dilemma and Technoscience.” Poiesis & Praxis, 7, 55–71. doi: 10.1007/s10202-010-0078-2

- Lösch, A. 2010. “The Defuturization of the Media: Dynamics in the Visual Constitution of Nanotechnology.” In Governing Future Technologies. Nanotechnology and the Rise of an Assessment Regime, edited by M. Kaiser, M. Kurath, S. Maasen, and Ch. Rehmann-Sutter, 141–155. Dordrecht: Springer Science.

- Macnaghten, P., M. B. Kearnes, and B. Wynne. 2005. “Nanotechnology, Governance, and Public Deliberation: What Role for the Social Sciences?” Science Communication 27 (2): 268–291. doi: 10.1177/1075547005281531

- McCray, P. 2013. The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Merton, R. 1948. “The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy.” The Antioch Review 8 (2): 193–210. doi: 10.2307/4609267

- Nordmann, A. 2007. “If and Then: A Critique of Speculative Nanoethics.” NanoEthics 1 (1): 31–46. doi: 10.1007/s11569-007-0007-6

- Nordmann, A. 2014. “Responsible Innovation, the Art and Craft of Future Anticipation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 87–98. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.882064

- Owen, R., J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, eds. 2013. Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society. Chichester: Wiley.

- Owen, R., J. Stilgoe, P. Macnaghten, M. Gorman, E. Fisher, and D. Guston. 2013. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 27–50. Chichester: Wiley.

- Pellé, S. 2016. “Process, Outcomes, Virtues: the Normative Strategies of Responsible Research and Innovation and the Challenge of Moral Pluralism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 233–254. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2016.1258945

- Rip, A., T. Misa, and J. Schot, eds. 1995. Managing Technology in Society. London: Pinter.

- Roache, R. 2008. “Ethics, Speculation, and Values.” NanoEthics 2 (3): 317–327. doi: 10.1007/s11569-008-0050-y

- Sand, M. 2016. “Responsibility and Visioneering – Opening Pandora’s box.” NanoEthics 10 (1): 75–86. doi: 10.1007/s11569-016-0252-7

- Selin, C. 2008. “The Sociology of the Future: Tracing Stories of Technology and Time.” Sociology Compass 2: 1878–1895. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00147.x

- Shelley-Egan, C. 2011. “ Ethics in practice: responding to an evolving problematic situation of nanotechnology in society.” PhD thesis (doc.utwente.nl/79247/1/thesis_C_Shelley-Egan.pdf; Accessed March 31, 2017).

- Simakova, E., and C. Coenen. 2013. “Visions, Hype, and Expectations: a Place for Responsibility.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 241–266. Chichester: Wiley.

- Swierstra, T., and A. Rip. 2007. “Nano-ethics as NEST-ethics: Patterns of Moral Argumentation about New and Emerging Science and Technology.” NanoEthics 1: 3–20. doi: 10.1007/s11569-007-0005-8

- Sykes, K., and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Responsible Innovation – Opening Up Dialogue and Debate.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 85–108. Chichester: Wiley.

- van den Hoven, J. 2013. “Value Sensitive Design and Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 75–84. Chichester: Wiley.

- van den Hoven, J., N. Doorn, T. Swierstra, B.-J. Koops, and H. Romijn, eds. 2014. Responsible Innovation 1. Innovative Solutions for Global Issues. Dordrecht: Springer.

- van der Burg, S. 2014. “On the Hermeneutic Need for Future Anticipation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 99–102. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.882556

- Vig, N., and H. Paschen, eds. 1999. Parliaments and Technology Assessment. The Development of Technology Assessment in Europe. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- von Schomberg, R., ed. 1999. Democratizing Technology. Theory and Practice of a Deliberative Technology Policy. Hengelo: International Centre for Human and Public Affairs.

- von Schomberg, R. 2012. “Prospects for Technology Assessment in a Framework of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Technikfolgen abschätzen lehren: Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methoden, edited by M. Dusseldorp and R. Beecroft, 39–62. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- von Schomberg, R. 2013. “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 51–74. Chichester: Wiley.

- Weber, M. 1946. “Politics as a Vocation.” In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, edited by H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, 77–128. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Webster, A. 2007. “Crossing Boundaries: Social Science in the Policy Room.” Science, Technology and Human Values 32: 458–478. doi: 10.1177/0162243907301004

- Woodhouse, E. 2014. Science, Technology and Society. San Diego, CA: University Readers.

- Zülsdorf, T. B., C. Coenen, A. Ferrari, U. Fiedeler, C. Milburn, and M. Wienroth, eds. 2011. Quantum Engagements: Social Reflections of Nanoscience and Emerging Technologies. Heidelberg: AKA GmbH.