ABSTRACT

Anticipation of the future use of innovative technologies and of their respective societal impact is at the core of technology assessment and responsible research and innovation. Stakeholder and user involvement is often thought to be important for broadening the design and specification of technology before its use; meanwhile, demand analysis is typically used to determine which type of already developed technology is best suited to adequately meet a particular societal demand. Thus, we ask whether the process of demand analysis can be used to enable stakeholders and users to envision and assess future technologies. This question will be answered regarding assistive technologies for people with dementia by focusing on the respective care-giving arrangement, an area where up to now no or only low-level technologies have been in use. The demands of these people for support are typically expressed in nontechnical terms. We find that the involvement of technology developers helped these participants to begin imagining more specific potential technical solutions and to assess them with respect to their future desirability.

1. Introduction

Caring for the ill and the aged is today seen as a high moral obligation that is based on a broad consensus in many societies. For this reason, it is hardly surprising that there are demands for ethical reflection to be conducted precisely for technological developments in the field of health care and especially for providing care. The daily practice of helping patients to lead a dignified and self-determined life (§ 2 Para. 1 German Social Code XI [Sozialgesetzbuch XI]) poses a particular challenge (BMG Citation2013). In this sense, the care sector can be considered as a sphere of social action in which responsible research and innovation (RRI) is particularly desirable since RRI is linked with the aspiration of being able to achieve better innovations by means of stronger ethical reflection by organizing the innovation process as

a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view on the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability, and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society). (von Schomberg Citation2011, 9)

With regard to the methodological implementation of this high goal, von Schomberg noted at an early point that both technology assessment (TA) and technology foresight represent core components of RRI. There are two reasons for this. First, it is impossible to judge which technologies can be assumed to be socially desirable without an accompanying consideration of their possible impacts. Second, it is also impossible to avoid making reference to the future in the context of the problematic circumstances being described or of the technical options for resolving the problems (von Schomberg Citation2012). In this way, RRI relies on existing procedures for reflecting on technology such as technology foresight, which aims to explore possible futures in order to allow decisions to be made that are likely to promote desirable states (Cuhls Citation2003), and technology assessment, which refers to assessment of the potential impact of technological advance in the sense of RRI (Grunwald Citation2011). In the introductory editorial to the founding issue of the Journal of Responsible Innovation (Guston et al. Citation2014), technology assessment is named as one of the traditional concepts – in addition to risk assessment – that responsible innovation draws on. This editorial reminds readers that technological innovation and social innovation must be considered jointly. On the one hand, humans are technological beings who have developed as individuals and as societies under the influence of technological innovation. On the other hand, equal consideration must be given to cultural influences, e.g. to

our abilities to care, create and cooperate, to love, laugh and learn, and to find and make meaning. Just as our tools shaped our hands, our cooperative hunting behaviour yielded the calories that fed the growth of our brain. We are more than technological beings; to forget either aspect is to limit ourselves, drastically. (Guston et al. Citation2014, 1)

The approaches currently employed in TA address these issues by becoming more participatory and reflexive. In other words, these approaches broaden technological development by including more aspects and more actors and doing so at an earlier stage. The ideal goal is to achieve better technology in a better society, as Schot and Rip (Citation1997) put it with regard to constructive TA (Rip, Misa, and Schot Citation1995). The intention is to feed societal and political concerns directly into on-going innovation development with the help of sociotechnical scenarios in which different consequences for society and technological alternatives are analyzed (Rip and Te Kulve Citation2008). Other TA approaches address, furthermore, the technical innovation process in order to realize ‘soft intervention, attempting to modulate ongoing sociotechnological developments’ (Rip and Te Kulve Citation2008, 50) such as real-time technology assessment (Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002), value sensitive design (Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2002), and midstream modulation (Fisher and Mahajan Citation2006). In general, ‘constructive dialogues’ between innovators and interested or relevant stakeholders are initiated in order to help ensure that the values and opinions of these stakeholders are taken into consideration in the innovation process (see, for example, Litz Citation2008; Flipse and Puylaert Citation2017). This is a core concept of RRI (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), which underlines the need to include stakeholders and their viewpoints and to be responsive to their thoughts and ideas by actively incorporating them in innovation development.

To better understand how these aspects can be implemented in a concrete RRI project and to develop tools for this purpose, the European Commission has funded a variety of projects through the Horizon 2020 Research Program that tend to be aimed at addressing ‘grand challenges’ including challenges related to health and well-being.Footnote1 While some of these projects focus on specific technologies and strive for a medium level of abstraction (e.g. the ETICA project;Footnote2 cf. Stahl Citation2011; Stahl, Jirotka, and Eden Citation2013), the project presented in this paper, in contrast, strives for the lowest level of abstraction at which technologies have already been specified. It asks how RRI projects oriented towards societal challenges can be assisted by such ‘micro-level’ TA practices in order to achieve the declared goal of ‘science for society, with society’ as well as to have ‘the right impacts’ in a very concrete sense and in a specific context of action (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012). Given that the aspect of anticipation is particularly emphasized within frameworks for RRI (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), we employ a demand-based procedure in which anticipation already occurs since participating actors have to imagine future forms of technology in the context of action, in order to create a basis on which to assess their possible desirability. This imagining is, we suggest, easier to do if such technology is already specified and is now being employed in an action context in order to support incremental modifications or to extend it by using supplementary technology. The challenge is greater, however, if there is no technological support or only very little available in this context of action. This is the case in the action context considered in this case; namely, caring for people suffering from dementia.Footnote3 The research question is thus, Can we as TA practitioners help stimulate actors to productively imagine options for desirable technological futures in a specific action context?

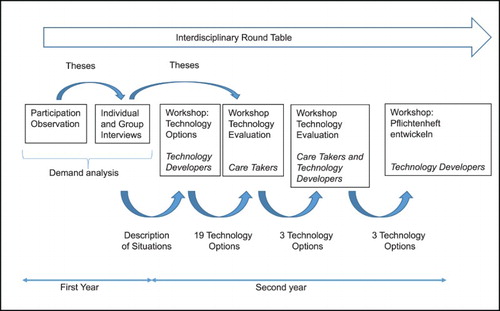

Conceptually, our project extends the constructive dialogue between technical innovators and users, and stakeholders in general, in the above-mentioned TA approaches. This project moved the start of this dialogue – which usually begins as early as possible in the technology development process – forward into the pre-phase of these projects. We asked the actors in a care-giving arrangement what kind of technology they imagined to be helpful in the arrangement. This task was necessary with respect to the call for projects, which focused on technology development. However, as we proposed technology development within the framework of RRI, the social aspects mentioned by caregivers and others were also included in the whole anticipatory process and put into practice in the round table discussion (see ). As such, one of the formal goals of the project was to identify, if possible, concrete technical solutions for use within this context. Such a pre-phase can be ideal preparation for TA projects as the identification of the technology to be developed is already organized in a discursive manner. The results of the pre-project initiated the TA and RRI process, which then further develops the sociotechnical change in the care arrangement.

In the following sections, the action context – the care-giving arrangement – is briefly presented (Section 2); then the methodological procedure is described regarding how the imagining of technological solutions was achieved (Section 3); finally, the results are presented (Section 4) and discussed (Section 5).

2. Action context: caring for people with dementia

The general situation of care-giving in Germany has already been described as precarious (e.g. Geyer Citation2015). Because of the increasing number of people suffering from dementia, the situation will presumably become even more so in the coming years. The number of people globally suffering from dementia is estimated to be 44 million (in 2014), and it is expected that this number will rise to 65 million in 2030 and to 115 million in 2050 (Ferri et al. Citation2005; Prince et al. Citation2014). Currently 1.2 million suffer from light to strong dementia in Germany.

As dementia becomes worse, there is an increasing loss of cognitive functions, including memory, thought, ability to learn, speech, and judgment. This is apparent, for example, in a decreasing capacity to solve everyday problems independently. There is similarly an increase in misperception, anxiety, and delusion. A life in memories and the increasing loss of spatial and temporal orientation lead to extreme restlessness, which can take the form of a strong urge to move (referred to as wandering). The combination of a loss of orientation and an urge to move can lead to a potential for self-endangerment, such as when a person going for a walk on their own cannot find their way back or fail to recognize dangers such as those posed by a heavily traveled street. Yet it is precisely mobility that is recommended as an intervention to activate brain function and to promote participation in social life. For instance, the authors of a set of official guidelines for dementia,Footnote4 when considering psychosocial intervention, recommend ‘regular physical movement and an active mental and social life.’ In this connection, the authors refer to studies that judge an active lifestyle that includes physical movement, sports, and social and mental activity to offer protection against the manifestation of dementia. Movement can thus be considered as an effective and efficient key component with few side effects in the various forms of care and assistance provided to people suffering from dementia. Associated with movement is motor, sensory, and social activation that can influence the subjective quality of life and the functional status of people with dementia as well as contribute to preventing falls, contractures, and bedsores. In this way, existing resources can be preserved as long as possible and the need for highly intensive care can be delayed.

Mobility – especially outside the institution – creates a dilemma, however, for caregivers, residents in a nursing home, and their relatives. On the one hand, the objective is to call for and promote the autonomy of people with dementia; on the other hand, depending on an individual’s daily status and cognitive capacity, caregivers and relatives may prioritize safety, which frequently correlates with forms of a deprivation of liberty. This leads to a situation in which a resident’s self-determination and autonomy, which are actually desired, are limited by considerations of safety and concerns about self-endangerment. The goal is consequently to organize outside activities according to the motto, ‘as much freedom as possible, and as much protection as necessary.’

3. Methodological approach

The project ‘A Mobile and Independent Way of Life for People with Dementia’ (or Movemenz, for short) pursued the goal of determining whether and – if so, in which form – it is possible for technological assistance to help people with dementia maintain their mobility. The context of action to be analyzed was the care-giving arrangement established for an individual with dementia, which consists of the person with dementia, his or her relatives, the professional caregivers in the nursing home, and the voluntary supporters (Krings et al. Citation2014).Footnote5 In this care-giving arrangement, no technology or only very simple forms of it (e.g. a rolling walker or rollator) are currently employed. Consequently, stimulating stakeholders’ ability to imagine systems of assistive technology that can provide support in this arrangement constitutes, in our view, a special methodological challenge. Although various technologies have been created,Footnote6 some of which are ready for the market and have even been assessed positively in relevant field tests, none have been able to establish themselves in the market and, thus, only a few exceptional items have made it into care-giving routines (e.g. Bieber and Schwarz Citation2011). This means that in this context of action we have a constellation in which technological offerings have not been made that are optimally congruent to specific social needs. The question is why this is the case.

From the perspective of some experts, there are various factors that play a role in this mismatch.Footnote7

Doubts as to efficacy

Lack of cost efficiency

Lack of familiarity with the technology and thus a lack of multipliers

Lack of a technology module in the training to become a caregiver

No or unresolved refinancing, legal insecurity, and technical problems

A brief excursus into the current literature in the field of ambient-assisted living (AAL), which can be seen as the general technology development path of our topic, reports these mismatches as well.

Even after years of research, innovation, and development in the field of health care and life support, there is still a lack of good practices on how to improve the market uptake of AAL solutions, how to commercialize laboratory results and prototypes and achieve widely accepted, mature solutions with a significant footprint in the European market. (Hmida and Braun Citation2017, 182)

The findings of this review clearly show that until now the AAL domain neglects the view of the entire AAL ecosystem. Furthermore, the proposed solutions seem to be tailored more on the basis of the available existing technologies, rather than supporting the various stakeholders’ needs. Another major deficiency that this review points out is the lack of an adequate evaluation of the various solutions. Finally, it seems that, as the domain of AAL is pretty new, it is still in its incubation phase. Thus, this review calls for moving the AAL domain to a more mature phase with respect to the research approaches. (Calvaresi et al. Citation2017, 239)

The methodological approach in Movemenz was developed to overcome this incongruence to the care-giving arrangement. The procedure involves identifying the needs in the care-giving arrangement and discussing the possible approaches to a technological solution before deciding on a specific technological solution ().

This methodological procedure was initiated by conducting a general observation of the activities and processes in a home. Methodologically, this followed the idea of participant-observation, although we only managed to achieve a two-week period of observation. In this phase, three to four observers were present as silent observers at different stations and during different actions in the nursing home from morning until evening. The knowledge that the project team gathered in this phase was edited into theses that subsequently served as the basis for the substantive preparation of the individual and group interviews with the various actors in the care-giving arrangement.

Individual interviews were conducted both with the people with dementia since their physical and mental conditions prevented them from being in a position to participate adequately in group interviews, as well as with the management and the administrators since the distribution of roles in the home gave each of them a special perspective towards activities, leading them to mention different needs. Group interviews in the form of focus groups were conducted separately with professional caregivers, volunteers, and relatives of those with dementia. Here, group interviews were preferred to numerous individual interviews since group interviews offered the advantages that the connections between arguments can be seen since they are typically developed by the group in a discussion and that other participants in a discussion often provide an initial evaluation of the given arguments. In the semi-structured group and individual interviews, each of the interview partners first gave an introductory description of themselves, which was then followed by questions as to the general need for assistance in care-giving. They concluded with a concrete discussion of the need for assistive technology from an individual and vocational perspective.

Both the needs for assistance, which were formulated in general terms, i.e. not yet in terms of technical specifications, and the technically formulated possibilities for assistance were subsequently discussed with technology developers at a separate brainstorming workshop. For this purpose, the needs were prepared as brief descriptions of scenes, which provided impulses in the discussion with the technology developers. The workshop with the technology developers was supplemented by a discussion block in which the developers for their part could make suggestions regarding assistive technology in the context of the keywords dementia, mobility, home care, and adaptive systems. Among the types of technology that were suggested were some that had already been developed as well as some for possible solutions that did not yet exist.

The systems of assistive technology suggested at this workshop were then discussed with the professional caregivers and the relatives. A selection process was linked with this discussion. This means that the actors in the care-giving arrangement evaluated the suggested technological solutions on the basis of their own activities and that only those solutions were pursued further that were considered both possible to implement and desirable from the perspective of the stakeholders.

In the next step, it was the technology developers’ turn once again. They worked out the remaining technical possibilities in greater detail and drafted the first functional specifications. These were discussed one last time with the professional caregivers and relatives before detailed specifications were prepared for the systems of assistive technology, which in turn can be referred to as the basis for future technology development projects.

To give some numbers that underpin the process, 10 individual interviews were conducted with people with dementia and the representatives of the ‘neighborhood’; three were with exploratory focus groups consisting of professionals, voluntary caregivers, and relatives; and another five workshops with caregivers and technology developers. In all, the workshops were held in the following order: workshop technology developers, workshop caregivers, workshop technology developers, workshop caregivers/technology developers, and workshop technology developers.

The whole process was accompanied by a round table discussion among an interdisciplinary expert group. The round table met six times and had several tasks in the pre-project. It gave feedback on the (interim) project results. The results both of the demand analysis and from the workshops with technical experts and caregivers were discussed at the round table. Experts from each participating scientific discipline (technical, legal, social, and ethical) reported their discipline-related reflection on the context of the anticipated solution. Here, they incorporated all the results from the empirical phase (nontechnical demands) as well as those in the general recommendations for the subsequent technology development process. This is indicated by the arrow in , pointing in the direction of the follow up project.

In summary, the methodology used in the Movemenz project can be described as (1) proceeding from the needs expressed by the members of the care-giving arrangement and formulated in a nontechnical manner, (2) that these needs were discussed with technology developers, and (3) that those results were subsequently discussed with the participants in the care-giving arrangement to obtain their approval. This interplay took place several times (see above), with the possibilities for technical solutions being elaborated in more and more detail. (4) The whole process was accompanied and reflected on by the interdisciplinary round table discussion.

4. ResultsFootnote9

4.1. Need assessment

Substantively stimulated by the theses that were prepared by the project team on the basis of their silent observations, the first round of individual and group interviews were strongly oriented around the boundary conditions (both those general in nature and those resulting from care-giving policy) of the care-giving activities. The topics discussed were the caring relationships and the resulting demands on time, with additional questions being raised as to whether the introduction of assistive technology is more likely to destroy jobs. These factors were given further consideration in the research project, but are not a topic of consideration in this paper. Yet they do document the assumption that in a nontechnical context possible needs may be made a topic in a nontechnical manner. In the following, the results of the interviews will be presented in greater detail in order to demonstrate the overall situation in the care-giving arrangement from different perspectives. At the end of each of these presentations, we consider the concrete questions regarding potential technical solutions, although only a few statements were made in this connection, and they were vague, such as the following by the institution’s director:Footnote10

I believe that you always have to look from the user’s point of view and ask what the individual needs in order to live as free and mobile as possible in his part of town. And technology can provide support; technology might not replace the caregiver or human attention, not just might not but 100% certainly cannot replace human attention. But technology can help people to continue to live a life in as self-determined and self-responsible a manner as possible despite their limitations. There will not be a technology that is suitable for everyone; it must always be adaptable to the individual, i.e. offer a bundle of opportunities.

The director’s comments about technologies offering solutions became more specific when he considered the daily situation in care. For example, in his opinion, location systems are a promising topic:

But it would be great if the rollator could send a signal to the caregivers, ‘Resident is on a familiar route.’ She goes there, and they know that she will come back after being there.

That can go so far, to continue with the rollator, when someone moves through the neighborhood that in the bakery the message appears on the baker’s screen, ‘Here comes Mrs. U., who would like to be greeted personally. She is coming from the nursing home.’ And then the baker would know that he would be paid later.

Topics raised in the group interview with the caregivers centered on the considerable challenges posed in providing care and taking responsibility for older people in general and for people with dementia in particular. Important factors mentioned were that the length of a resident’s stay at a nursing home was short (in this study the average was 1.8 years), that it furthermore was the last station in the life of the residents, and even that they frequently do not agree to ‘coming here and that is perhaps not how they wanted it to be.’ Furthermore, relatives would interfere much more than for example in a hospital and that it was difficult in general to achieve the goal of ‘feeling well’ that is prescribed by the care-giving plan: ‘We cannot overlook that; we have to answer it, to think about what would make this person feel better, and that is difficult, especially so if they have dementia.’ The caregivers were in agreement on the fundamental challenge: ‘to retain the individual quality despite having a system that has to function.’ The residents would express their desires very clearly, but they could not always be satisfied. An example is the time at which the evening meal is served. Some want to eat at 5:30 pm, while others not until 7:30 pm. That is simply not possible. With regard to the tasks that were a consequence of dementia, the following fundamental challenge was mentioned:

And what is really old stuff, like really old traumas, let’s say, that simply come out again at an older age, in dementia in any case, and to find out about it and perhaps even that it can be resolved, in other words that we might find a point at which it can be really worked on and resolved.

Yes, such limits are simply given, where we do not have the time, and it often hurts. That simply he now needs just a little, but then the bell rings and there are still four or five in bed and they want out too. And yes because every person, that makes me feel sorry, simply needs a little longer at the sink, but things simply have to move on. That is over 12 hours, sometimes 13, 14, 15 hours that he stays in his room; I mean that you isolate a person in that way in their own four walls.

Ultimately this leads, first, to the fact that the pressure to provide physical care becomes dominant. This is where technology, according to the statements of the caregivers, could actually provide some relief; yet the caregiver should always also take into consideration that, ‘it is not that I send a robot and it does what I tell it, but I am with it and have some technological assistance.’ Then they could approach the person in an entirely different manner because they, according to a caregiver, would be much calmer since they would have to bear significantly less pressure. One caregiver was very explicit and imagined technological assistance for the following situation from her daily work:

That is often so difficult – another cushion here, a cloth there, so that he can lie really comfortably. Then I image a kind of a mat that adjusts to a resident’s body, the entire person, where I am there as the caregiver and can control it, always with regard to the person, individually. I could imagine that something – because ultimately the point is for the resident to lie properly – I have to support and prop up each irregular part of the body as needed so that a leg can simply lie there and relax.

In the course of the discussion in the focus group, the topic of mobility came up. At this point, the caregivers were self-critical: ‘Mrs. R. was the same; at some point she was restrained because we did not have enough time and yet she was able to walk quite well if she was not alone’; or

But we don’t have the time for that any more, and now there is no one who can go walking with her even though it would not have been anything special to at least walk with her and her rollator to breakfast after hygiene.

In their group interview, the volunteers emphasized that good care cannot be given to elderly people without the support of volunteers since it is hardly possible for personal attention, contact, and much more to be provided in a nursing home. One volunteer described it in these words, ‘I think the staff does its best. But today we simply have these targets, or they have these standards to achieve all of this in a certain amount of time … ’ However, precisely with regard to physical mobility, this time is lacking: ‘It is naturally possible that [walking with the rollator] only takes a quarter of an hour, but I think it’s important and above all that they get out a little.’ This leads to the situation that the residents sit too much and are alone in their rooms too frequently. Asked about assistive technology to promote mobility among people with dementia and in nursing, the volunteers expressed conflicting opinions. One volunteer could not imagine technology providing any assistance in dementia. Another described an immediate solution for certain situations:

I have an idea, but it is completely rejected … Once again an old woman has disappeared from the home, and they have been looking for her for at least six hours, with an airplane, with everything. Where is she? Naturally they are not being locked in; they are free to go out … Today they can locate anyone by finding their cell phone. Well, I think that they can locate every old person [with such a tracking device].

But here in the home we have two or three persons that like to go out and run away. We know who they are. We know precisely who they are. You don’t need it for everyone. So, with 180 rooms, not all of them that can go out will be checked.

In their focus group, the relatives brought up the topic of the transitional phase from living at home to living in a home. What led an individual to make the decision to move to a home? What were the most obvious changes in behavior in the home? Both positive and negative examples were documented.

In the further course of the group discussion, the issue was to gather relatives’ estimates of the value of technological aids in care-giving. The relatives could readily imagine technological aids being used to ease or to support their care-giving work, such as incremental advances made to the rollator and wheel chair.

And further develop in the direction that a wheel chair or a rollator is improved. We had once already said that what bothers me most about the rollator is the location of the brake tubes. They shouldn’t be running on the outside on the left and right. You walk past a bush and get stuck. They could be placed differently; Or that you can technically modify a wheel chair or can add something to help [lift] a rollator so that it is easier to get it onto a sidewalk. A rollator has to be lifted up by hand, for example.

There is no general answer to that. If I heard monitoring for my mother, then my hair would stand on end. That is a big topic and I clearly say ‘No.’ But if I would now experience my mother in the state of some of the other residents here, and I live 30 kilometers away, and my mother were to be picked up on the street, … I don’t know how I would then decide.

With GPS, I consider it very positively. You don’t have to take it; you can leave it up to the people. If someone says, ‘No, I don’t want my mother to be monitored,’ then the thing is not turned on. And another person is happy and says, ‘It’s fine with me. If something happens, then they will find her.’

The relatives were quickly in agreement, however, about their general assessment of the importance of limiting the use of technology in care-giving, as the following quotation shows:

But a bit of a person should naturally still be left at the end, not that a robot suddenly comes into the room.

With respect to people with dementia, who would typically be considered the ‘users’ of assistive technology, it was only possible for us to determine their needs to a very limited degree in this study. At the home we studied, the manifestations of dementia were very specific to the individual, depending on the stage of dementia and on the individual’s personal composure. Furthermore, the residents of this home were very elderly, between 84 and 96, and with very few exceptions were in a later stage of dementia. We were only able to conduct six individual interviews with persons with dementia. This limitation in the number of persons interviewed was based on the fact that – according to the judgement of the home’s director and the nursing care management – a dialogue with further demented persons would not be possible because of the course of their dementia. In these interviews, as in all the other individual and group interviews, we first asked the persons with dementia in general about their needs as they perceive them living in the home. No concrete comments were made, whether in general or with regard to needs that could be addressed technically. This confirmed the assumption previously expressed by the staff that it would be very difficult or even impossible for these six persons with dementia to think hypothetically about their needs and any assistive scenarios that might be linked to them. With regard to possible technological assistance, there were answers but they were very general in nature. For two interviewees, it was even impossible for them to imagine any technological assistance. Another person said that she did not need any technological assistance. The rest of those interviewed were able to consider technological assistance in general and responded reticently yet positively to suggestions about technology that could, for example, help them while walking and make it easier for them to find their way back.

4.2. Discursive development of need-related technology options

These results from the requirements analysis have been presented in detail to demonstrate that these requirements were expressed in a general way, while it was only possible for a few concrete possibilities for technical solutions to be vaguely outlined. Against this backdrop, the second phase of the project (cf. ), during which technical options to meet the needs that were identified were supposed to be developed, began with a workshop to which the technology developers were invited. The fundamental idea was to present the needs that were identified in the nursing home and to ask the participants which technical options they saw on this basis to meet these needs. The methodological challenge to overcome was presenting the needs in a form corresponding to the objectives of this workshop.

This challenge was addressed by presenting concrete situations that we were able to describe on the basis of the participatory observations, or to be more specific, situations that suggested a need for technical assistance. Among these situations were several that lacked an immediate reference to mobility, where mobility is taken in both a physical and a mental sense. These inputs were classified into categories by the project team and were also associated with a concrete reference to technology, e.g. recursively to traditional assistive means of mobility. These descriptions were passed on to the technology developers, who were requested to note what associations they had from their technical perspective. For the sake of brevity, only the categories, which we divide into ‘technical’ and ‘nontechnical’ categories, are listed in . In most cases, the descriptions were supported by direct quotations from talks noted during the participatory observations and the individual interviews.

Table 1. Categories used to classify descriptions of the situations.

For the sake of illustration, the following description was categorized as ‘mobility’:

Description of situation: One of the residents needs a very long time to go from her room to her place in the dining room. Since the caregiver did not have the time to wait for her to arrive, she places the resident in a wheel chair and pushes it instead of encouraging the resident to move on her own. At the same time, the movement from the wheel chair to a chair at the dining table is also avoided. The lack of time thus leads to a loss of mobilization.

Illustrative quotation: ‘The same is true of Mrs. R. She was restrained just for a lack of time, and she was still able to walk well when she wasn’t alone.’

The technology developers were furthermore requested to freely suggest technical options to the keywords ‘home,’ ‘dementia,’ ‘mobility,’ and ‘neighborhood’ and to develop them further in the group if they considered them to be promising. The following ideas on technical approaches originated from these two threads:

An RFID bracelet that opens or closes doors

Sensing rooms (to calm down)

A symbol that lights up when a resident approaches a room or a rollator

Sonification of how close a person is to his or her room or to an object

Navigation system in hallways to aid orientation

Technology that reminds one to drink

Technology that stimulates one to play if it recognizes interest

Assistance systems that stimulate a person to go walking in general or to take bigger steps

Modified rollators and wheel chairs that function as fitness equipment

Illuminated footprints on floors to stimulate a person to take bigger steps

Rollators with a ‘bring and pick-up’ function

Rollators with a ‘call and follow’ function

Wheel chairs with a swarm function (a number of wheel chairs can follow one caregiver)

Autonomous patient care carts with a call function and autonomous refilling

Airbags on rollators or elsewhere for safety

Rollators/wheel chairs that avoid obstacles, use sensors to recognize dangers, and call for help or provide assistance

A robotic ‘dog’ or assistant that can call for help and actively provide assistance as needed when outdoors

An exoskeleton made up of sensors and motors worn on the body to promote the use of a person’s remaining strength and to provide assistance to ensure that sufficient strength is available or that a person does not lose their balance

A ‘bumblebee’ or miniature quadrocopter or octocopter that accompanies people with dementia outdoors and detects emergency situations or offers caregivers a minimum level of supervision

In the subsequent workshop with caregivers, these possible technical options were judged according to their suitability in the care-giving arrangement. This took place in the second part of the workshop. In the first part, the theses developed from the observation were discussed with the caregivers, in part to verify them. In a questionnaire completed prior to the workshop, the participants were asked to estimate whether a thesis was accurate or not. Of the 41 theses, 37 were considered to be accurate; the remaining four controversial ones were discussed during the workshop. This was, at the same time, preparation for the discussion about the technical options. The criteria mentioned in this connection were utility, applicability, acceptance, general concerns, and institutional implementability. Since for several options first prototypes of technical solutions had already been developed or products were already available on the market, modifications to these prototypes or products were discussed. A technical solution was only pursued further if such an improvement could be described in concrete terms. The following three options for technical solutions that were intended to be pursued further resulted from this selection process:

Rollator to promote mobility

Bumblebee

Wheel chair with a swarm function

These were then the basis for a joint workshop with technology developers and caregivers. During the workshop, participants evaluated how well these solutions addressed the needs of stationary care, the target group of people with dementia, and local factors at the nursing home, and discussed the initial requirements of the technology in light of what was deemed to be technically feasible. A final workshop with the technology developers was then held to formulate the concrete functional specifications for the technical planning of the possible solutions, which could serve as the basis for a subsequent technology development project.

5. Discussion

Against the backdrop of these results, it is possible to provide a positive answer to the question posed in this study as to whether we as TA practitioners might help actors in an existing (in this case, care-giving) arrangement productively imagine options for future desirable technological solutions (i.e. that are aligned with their needs). However, it was necessary for us to invest considerable methodological effort to achieve this objective. Initially, our study confirmed the assumption that an assessment of the needs expressed by the participants in a care-giving arrangement would produce nontechnical demands. Even if the participants were explicitly asked about possible technical solutions, there were very few answers and those given were vague. The methodological approach adopted here was to proceed initially with a division of labor, leaving the task of identifying specific technological options to technical experts. To this end, the needs that were identified had to be made comprehensible to the technology developers. The descriptions of situations portraying individual contexts of behavior that were developed for this purpose in turn proved to be useful for generating technical options. It was possible, on the one hand, to convey the context of action in care-giving, and on the other, for the problematic aspects of the action to be emphasized by the quotations. At any rate, the participants in the technical workshop felt they were in a position to identify demand-based technical options and responded by suggesting options that had already been envisaged as part of the general technical developments in this field.

It was also possible to then easily convey the technical options that resulted to the caregivers during a subsequent workshop. It proved helpful that the topics from the need gathering phase were discussed again at this workshop so that the caregivers were aware of the respective situations. At any rate, in discussing the technical options they were in a position to imagine the technology in the respective contexts of behavior and also to judge whether the options should be viewed as helpful or desirable in the care-giving arrangement. They concluded that three of the technical options that were initially generated by the developers should be pursued further.

The joint workshop of caregivers and technical developers that subsequently took place was organized at the request of the technology developers. This workshop – which is literally a constructive dialog in the sense of TA and RRI – was viewed by all the participants as being extremely instructive and productive because it brought the supply and demand sides together at a point in time at which there were only three options under discussion, so that there was sufficient time to discuss them in a very detailed manner. As a result of this workshop, the technology developers felt that they were immediately in a position to complete the functional requirements for the technology development at the final workshop.

From the general perspective of RRI, in which the inclusion of stakeholders and users is considered a necessary conceptual measure, as well as from that of demand-based technology assessment, which methodologically expects a similar inclusion of users, it is necessary to interpret these results in such a way that the imagining of technology futures represents a special methodological challenge. This challenge is associated with the need-based procedure or with the orientation on the grand challenges of the future. In these cases, one first identifies situations exhibiting a social problem in a behavioral context, and it is completely open as to which kind of technology might be of assistance in this context. It is even open as to whether it is at all possible to imagine technology contributing to solving the problem. This openness makes it a particular challenge to imagine potential technical solutions. The Movemenz project successfully showed, if only in an exemplary manner, that this challenge can be solved by involving technology developers who themselves have experience in developing technical options. The methodological challenge is then shifted so that the needs that are identified have to be translated in such a way that they can then serve as a basis for the technology developers to consider them. The descriptions of the situations that were employed in this project satisfied this objective.

The resulting technology options provided, conversely, the basis for the caregivers to be in the position to imagine and evaluate the options within their care-giving arrangement. This means that one approaches the challenges from two sides. Experts for the development of technical options are involved, which makes it necessary for the needs situation that is identified to be presented in an appropriate manner. It is then possible to discuss with the actors in the care-giving arrangement whether any adjustment of the suggested technology developments is necessary in order to better meet the actual needs.

Consideration of the entire care-giving arrangement together with all of its participants is particularly important for need assessment. Both the relatives of the people with dementia and volunteers are regular members of this arrangement, and they express demands on the quality of the caring accordingly. These demands can naturally also be transferred to technological assistive systems to be used in care-giving. The broadly designed need analysis, which ultimately formed the basis that made development of the theses possible that in turn were the foundation for the development of the technology options, represents the key to the success of the project. It was precisely the joint consideration of the needs by all the participants in the arrangement that permitted a comprehensive description of the requirements, since conflicting statements can be encountered in this context. For instance, the relatives stated that they would like to see as many activities as possible take place outside the home. Meanwhile the professional caregivers stated that they already had to make trade-offs given the constraint of limited time. On the other hand, it contradicts one of the few statements that we were able to take from the interviews with the people with dementia. The latter namely indicated that their relatives do not like to see them go out to the street alone because it is too dangerous.

The people with dementia are also actors in the care-giving arrangement; indeed, they are at its focus. Yet their cognitive limitations made it impossible for us to have them participate in the determination of the requirements to the extent originally intended. The challenge posed by conceiving potential technology options and then judging their consequences in the care-giving arrangement significantly exceeded their capabilities. For this reason, we were only able to gather references from these interviews that were rather anecdotal. This reference proved to be incorrect when it was discussed with the relatives in the group interview. The relatives were quite aware of the dangers but judged the advantages of movement outdoors to outweigh the dangers:

And she herself is responsible for herself when she goes out with her rollator, stands in the middle of the street and looks where she is. I can’t do anything about it; I can’t lock her up. I am glad that she can still walk and move.

That is really something when the caregivers do not even notice that someone is missing. But that does not mean that they are negligent; it simply shows the kind of situation they are in. That was the middle of the day and it was pandemonium from front to back.

In summary, we can state that it is possible to conduct a need-based form of RRI, one that is ultimately oriented towards grand societal challenges, when one succeeds in identifying a corresponding social context of behavior. Depending on the level of abstraction at which it is analyzed, there can be different methodological challenges to generating knowledge about the future, within the limits of the latter’s epistemological uncertainty. At the microlevel of a care-giving arrangement for maintaining the mobility of people with dementia in a nursing home, which is the object of consideration in this paper, it becomes clear that it is necessary first to break down one of the grand challenges to one that can be handled. In the realm of demographic change, and proceeding from the future social challenges to providing care for elderly people, this means that the need for providing care for people with dementia will increase. It is considered desirable for people with dementia to retain their mobility to the best possible degree because this exerts a positive influence on their overall state of health and the progression of the dementia. In the area of assistive mobility, the focus is on people with dementia living in a home and their opportunities to be mobile outside. It is necessary to traverse this stepwise extraction of a behavioral context from the grand challenge posed by demographic change in order to consider a behavioral context that can be studied. In this care-giving arrangement, we succeeded in having the participants imagine different technological assistive systems that one can assume will meet the actual needs of participants in this arrangement. One assumption that is made is that the care-giving arrangement in other nursing homes will appear similar inasmuch as the needs there will also be similar. This assumption must still be examined since, on the one hand, it was mentioned in the interviews that the needs of people with dementia for technological support vary from individual to individual, and on the other, it can be assumed given the large and continuously increasing overall number of such individuals that a sufficient number of similar care-giving arrangements will have to be established.

From a methodological perspective, the results of our pre-project set the stage for up to three technology development projects – as three technologies have been identified here as promising – which offer an opportunity to continue the constructive dialog in the sense of TA and RRI. The empirical work, the professional reflections by the round table of experts, and the results from the workshops reported here can provide the groundwork for a responsible innovation process. Currently, we are discussing such a technology development project with the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, which launched the original call for these pre-projects. If successful, we hope to show that it was possible to employ the assistive technology systems suggested here and to demonstrate that they represent a desirable technical innovation in the long term in the sense of responsible research and innovation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the entire team of the project Movemenz ‘A Mobile and Independent Way of Life for People with Dementia’ in which the results presented here were gathered. Our special thanks go to Silvia Woll, Claudia Brändle, and Marcel Krüger.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Prof. Dr Michael Decker did his PhD in Physics at the University of Heidelberg and obtained his habilitation (Technology Assessment) at the University of Freiburg in 2006. Since 2004, he has been a member of the directorate of ITAS and, since 2009, professor for technology assessment at KIT. He has headed the division ‘Informatics, Economics, and Society’ at KIT since 2015.

Nora Weinberger studied environmental engineering and process engineering at the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus. The focus of her work is on ‘water’ and ‘soil’ (Diplom). Since 2007, she has worked as a scientist at ITAS dealing with technology monitoring and technology assessment in care-giving arrangements.

Dr Bettina-Johanna Krings studied political science, sociology, and anthropology (MA) at the University of Heidelberg and did her PhD in sociology at University of Frankfurt/Main. Since 1995, she has worked as a scientist for ITAS dealing technological innovations and their impacts on working structures. She heads the ITAS research area ‘knowledge society and knowledge policy.’

Johannes Hirsch studied computer science at KIT, main focus were assistive technologies for elderly, especially for people with dementia (Diplom). Since 2015, he has worked as a scientist at ITAS dealing with constructive technology assessment in care taking arrangements.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/societal-challenges. For detailed information: https://www.rri-tools.eu/; http://engage2020.eu/; http://www.great-project.eu/; http://www.livingknowledge.org/projects/perares/; http://www.progressproject.eu/; http://res-agora.eu/news/; http://responsibility-rri.eu/.

3. The action context is thus chosen from among the seven fields of social needs mentioned above, in this case demographic change, for which the EU hopes that explicit solutions will be found on the basis of RRI.

4. See the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN); Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN) (eds.): S3-Leitlinie ‘Demenzen.’ Empfehlung 95 http://www.dgn.org/leitlinien/3176-leitlinie-diagnose-und-therapie-von-demenzen-2016. Last Accessed: 31 August 2016.

5. In the care-giving arrangement, it is possible to consider other actors such as the operator of the nursing home and the corporate body responsible for it. This study focused only on the narrower context of action since the question was initially which assistive technology would be acceptable to the actors without considering the ability of the institution to implement it.

6. See on this https://www.wegweiseralterundtechnik.de.

7. See for greater detail in Weinberger and Decker (Citation2015, pp. 37ff).

9. Only some of the results of the Movemenz project are reported here to support the line of argument pursued in this paper. The comprehensive report of the results is to be published soon at KIT Scientific Publishing.

10. All quotes from the interviews are colloquial speech in German, translated by the authors.

11. German long-term care insurance levels.

References

- Bieber, D., and K. Schwarz, eds. 2011. Mit AAL-Dienstleistungen altern. Nutzerbedarfsanalysen im Kontext des Ambient Assisted Living. iso-Institut: Saarbrücken.

- Blackman, S., C. Matlo, C. Bobrovitskiy, A. Waldoch, M. L. Fang, P. Jackson, A. Mihailidis, L. Nygård, A. Astell, and A. Sixsmith. 2016. “Ambient Assisted Living Technologies for Aging Well: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Intelligent Systems 25 (1): 364–369. doi: 10.1515/jisys-2014-0136

- BMG (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit). 2013. Unterstützung Pflegebedürftiger durch technische Assistenzsysteme. Abschlussbericht: Berlin.

- Calvaresi, D., D. Cesarini, P. Sernani, M. Marinoni, A. F. Dragoni, and A. Sturm. 2017. “Exploring the Ambient Assisted Living Domain: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 8: 239–257. doi: 10.1007/s12652-016-0374-3

- Cuhls, K. 2003. “From Forecasting to Foresight Processes – New Participative Foresight Activities in Germany.” Journal of Forecasting 22 (2/3): 93–111. doi: 10.1002/for.848

- De Hoop, E., A. Pols, and H. Romijn. 2016. “Limits to Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 110–134. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2016.1231396

- Ferri, C., M. Prince, C. Brayne, H. Brodaty, L. Fratiglioni, M. Ganguli, K. Hall, et al. 2005. “Global Prevalence of Dementia: A Delphi Consensus Study.” Lancet 366: 2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

- Fisher, E., and R. L. Mahajan. 2006. “ Midstream Modulation of Nanotechnology Research in an Academic Laboratory.” ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, IMECE2006. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

- Flipse, S. M., and S. Puylaert. 2017. “Organizing a Collaborative Development of Technological Design Requirements Using a Constructive Dialogue on Value Profiles: A Case in Automated Vehicle Development.” Science and Engineering Ethics: 1–24.

- Friedman, B., P. Kahn, and A. Borning. 2002. “ Value Sensitive Design: Theory and Methods.” University of Washington Technical Report, 02–12.

- Geels, F. W. 2004. “From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-technical Systems Insights about Dynamics and Change from Sociology and Institutional Theory.” Research Policy 33: 897–920. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

- Geyer, J. 2015. “Einkommen und Vermögen der Pflegehaushalte in Deutschland.” DIW-Wochenbericht 82 (14/15): 323–328.

- Grunwald, A. 2011. “Responsible Innovation: Bringing Together Technology Assessment, Applied Ethics, and STS Research.” Enterprise and Work Innovation Studies 7: 9–31.

- Guston, D. H., E. Fisher, A. Grunwald, R. Owen, T. Swierstra, and S. van der Burg. 2014. “Responsible Innovation: Motivations for a New Journal.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 1–8. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2014.885175

- Guston, D. H., and D. Sarewitz. 2002. “Real-Time Technology Assessment.” Technology in Society 24 (1): 93–109. doi: 10.1016/S0160-791X(01)00047-1

- Hmida, H. B., and A. Braun. 2017. “Enabling an Internet of Things Framework for Ambient Assisted Living.” In Ambient Assisted Living, edited by R. Wichert and B. Mand, 181–196. Switzerland: Springer International.

- Krings, B.-J., K. Böhle, M. Decker, L. Nierling, and C. Schneider. 2014. “ITA-Monitoring ‘Serviceroboter in Pflegearrangements’.” In Zukünftige Themen der Innovations- und Technikanalyse. Lessons Learned und ausgewählte Ergebnisse, KIT Scientific Reports, edited by M. Decker, T. Fleischer, J. Schippl, and N. Weinberger, 63–122. Karlsruhe: KIT Scientific.

- Litz, F. T. 2008. Toward a Constructive Dialogue on Federal and State Roles in US Climate Change Policy. Arlington, VA.

- Moschetti, A., L. Fiorini, M. Aquilano, F. Cavallo, and P. Dario. 2014. “Preliminary Findings of the AALIANCE2 Ambient Assisted Living Roadmap.” In Ambient Assisted Living, edited by S. Longhi, P. Siciliano, M. Germani, and A. Monteriu, 335–342. Switzerland: Springer International.

- Owen, R., P. Macnaghten, and J. Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scs093

- Prince, M., E. Albanese, M. Guerchet, and M. Prina. 2014. Dementia and Risk Reduction. An Analysis of Protective and Modifiable Factors. World Alzheimer Report 2014. Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Rip, A., T. J. Misa, and J. Schot, eds. 1995. Managing Technology in Society. The Approach of Constructive Technology Assessment. New York: Pinter.

- Rip, A., and H. Te Kulve. 2008. “Constructive Technology Assessment and Socio-technical Scenarios.” In Presenting Futures, edited by E. Fisher, C. Selin, and J. M. Wetmore, The Yearbook of Nanotechnology in Society, Vol. 1, 49–70. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Schot, J., and A. Rip. 1997. “The Past and Future of Constructive Technology Assessment.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 54 (2/3): 251–268. doi: 10.1016/S0040-1625(96)00180-1

- Stahl, B. C. 2011. Pathways Towards Responsible ICT Innovation. Policy brief of STOA on the ETICA project. Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA) Report. Publication Office of the European Parliament.

- Stahl, B., M. Jirotka, and G. Eden. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation in Information and Communication Technology: Identifying and Engaging with the Ethical Implications of ICTs.” In Responsible Innovation, 1st ed., edited by R. Owen, M. Heintz, and J. Bessant, 199–218. London: John Wiley.

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

- von Schomberg, R., ed. 2011. Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. Accessed August 31, 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/mep-rapport-2011_en.pdf.

- von Schomberg, Rene. 2012. “Prospects for Technology Assessment in a Framework of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Technikfolgen abschätzen lehren: Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methode, edited by M. Dusseldorp and R. Beecroft, 39–61. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Weinberger, N., and M. Decker. 2015. “Technische Unterstützung für Menschen mit Demenz? Zur Notwendigkeit einer bedarfsorientierten Technikentwicklung.” Technikfolgenabschätzung – Theorie und Praxis 24 (2): 36–45.