ABSTRACT

The concept of Responsible Research & Innovation (RRI) seems to gain initial momentum. The lack of collective meaning however, results in a plethora of publications, which describe RRI from ad hoc perspectives. To provide a robust foundation for scholars and practitioners seeking to implement RRI, we aim to integrate those perspectives through a literature review. We develop a practical framework for RRI, synthesized from earlier frameworks and ideas, that can be operationalized in research and innovation practice to help make RRI more tangible for scientists and engineers. We analyze policy papers, EU project proposals, and academic articles on RRI that appeared between 2011 and 2016 to identify common qualifiers of RRI. The resulting framework integrates a set of qualifiers that are central to the concept of ‘responsive’ research and innovation. The framework also allows identification of ‘RRI shortcuts’ to be avoided. We invite scholars to investigate the applicability of this framework as a means of shifting RRI from concept to practice.

Introduction

Research context

During the past years, more and more academic literature, policy documents and project proposal calls have appeared on the notion of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) and its cognates such as Responsible Innovation.Footnote1 One of the earliest and often cited descriptions of RRI was developed by Von Schomberg (Citation2011, 9):

RRI is a transparent, interactive process in which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view on the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technologies advances in our society).

In theory, therefore, RRI seeks to align scientific, economic and societal interests and delivers products (and services) that are socially desirable (cf. Ribeiro et al. Citation2018). In practice, however, RRI lacks definition and clarity as well as recognition and uptake (cf. Lubberink et al. Citation2017a). Koops (Citation2015, 2) identifies a wide range of definitions of responsible innovation and concludes that although it is a popular term in science and policy, ‘it is by no means clear what exactly the term refers to, nor how responsible innovation, once we know what is meant by this, can or should be approached’. In short, a lack of clarity on what good quality RRI entails appears to form one of the barriers to the implementation of RRI in practice. Or as de Jong et al. (Citation2015) put it: “If [R]RI is to be effective as a guiding principle in science, there needs to be a greater, common understanding of what it means in terms of concepts and methodologies.’

We proceed from the premise that more clarity in this respect would allow innovators to adopt more responsible practices. More specifically, we feel that a lack of clarity on how RRI qualities relate to one another forms a barrier to implementation in practice. Several studies have emphasized that RRI should be performed in an integrative manner. Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013, 1573) for example states that ‘[RRI dimensions] do not float freely but must connect as an integrated whole.’ They also acknowledge that some RRI dimensions may reinforce each other whereas others may conflict:

[f]or example, increased reflexivity may lead to greater inclusion or vice versa. But […] these dimensions may also be in tension with one another and may generate new conflicts. Anticipation can encourage wider participation, but … it may be resisted by scientists seeking to protect their autonomy, or prior commitments to particular trajectories.

As such, it is essential for an integrative implementation of RRI that not only RRI qualities are defined but also that the mutual relationships among those qualities are explicated, to further help innovators make practical sense of these theoretical concepts. A report commissioned by the European Commission to describe the current state of RRI in Europe called for a coherent framework of RRI criteria:

The key objective of EU action should be to develop a coherent approach among the EU Member States that defines processes, instruments and criteria for RRI that encourage researchers and innovative firms to consider ethical concerns and address societal needs. A framework for the operationalization of RRI entails (a) defining criteria for RRI, (b) defining processes for a successful application of RRI, and (c) Defining instruments to encourage RRI. (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013, 4)

This paper seeks to contribute to the development of a coherent practical approach to RRI, specifically by taking up the call to define criteria for RRI by means of identifying qualifiers (that is, indicators of quality) for implementing RRI.

Criteria to assess RRI?

Other studies have attempted to answer such general calls for clarity, by developing RRI frameworks and assessment rubrics (see e.g. Kupper et al. Citation2015; Wickson and Carew Citation2014; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). While these studies share overlapping features that suggest a set of core characteristics, they also diverge in perspectives. For example, Kupper et al. (Citation2015) call for ‘Openness and Transparency’ and Wickson and Carew (Citation2014) call for ‘Honest and Accountable’ research, characteristics that are not explicitly included in the oft-cited dimensions of ‘Anticipation, Inclusion, Reflexivity and Responsiveness’ identified by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013).Footnote2 The similarities and differences among existing RRI frameworks have not been systematically reviewed to date, and we share Wickson and Carew’s (Citation2014) insistence on the need to identify criteria that are shared across RRI studies to inform the emerging concept of RRI. Since numerous studies formulate or report on RRI criteria, a systematic review of the literature on RRI criteria is in order. We aim to support the development of a practical framework of RRI implementation qualifiers, based on a systematic review of the literature. A framework in this context first requires an overview of qualifiers and of the relationships among them, whereby a qualifier refers to any action, behavior or activity that a researcher or innovator can undertake to support responsible processes and products. We therefore develop an overview of ‘good quality’ RRI and how these qualities are thought to support each other. Such a framework may be used to facilitate the integrative implementation of RRI by providing more clarity on ‘what good quality RRI looks like’ (Wickson and Carew Citation2014) and on which activities should be performed (possibly in conjunction with one another) to help ensure that research and innovation is performed in a socially responsible manner.

Research approach

The meaning of RRI is negotiated in both academia and policy, so documents from both domains are included. Since we aim to develop qualifiers based on concepts related to RRI, we focus more on conceptual than on empirical work. Qualifiers for both responsible ‘processes’ as well as their resulting ‘products’ can be distinguished (cf. Thorstensen and Forsberg Citation2016). We note that ‘products’ can be physical or non-physical, such as services, and ‘in their widest sense’ include impacts and outcomes (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). Von Schomberg (Citation2011) distinguishes ‘the innovation process’ and ‘its marketable products’. Similarly, Pellé (Citation2016) distinguishes between RRI strategies that focus on ‘processes’ versus ‘outcomes’. We consider an RRI process as an activity that researchers or innovators can perform to support RRI, and an RRI product as the outcome of such research or innovation activities, including academic findings and (marketable) products.

Qualifiers for responsible processes are further specified along several process dimensions. These dimensions are partially adopted from an influential attempt to develop an RRI framework (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), which suggests that the four process dimensions together support RRI as a means to ‘take care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present’ (1570). In the current study, these four process dimensions form the grounds to, inductively, further specify process qualifiers. We also set out to explicate conceptually the interactions among those process dimensions. To this end the practical rationale of each process dimension – the reason to perform the activity in the light of RRI – is explicated and graphically presented.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the second section, we describe the literature review methodology. Subsequently, the results of the literature review are presented in a framework in the third section. Our framework is then presented and further developed in the fourth section. We discuss its value and limitations in the final section.

Methodology

In this section, the two-step methodology of our review is described. First, we sought any documents that could be relevant to the study produced between 2011 and 2015. Relevant documents were selected according to the criteria described below. Second, selected documents were systematically analyzed to identify a set of qualifiers on RRI products and processes. The two steps are described in more detail below.

Seeking and selecting relevant documents

As stated, we reviewed both academic and policy documents. In terms of academic documents, all chapters from Owen, Bessant, and Heintz (Citation2013) were reviewed as this was one of the first books on Responsible Innovation and summarizes the first academic thoughts on and attempts at its practice.

Furthermore, all chapters from the proceedings (van den Hoven et al. Citation2014; Koops Citation2015) were reviewed as these volumes are based upon work that was originally presented at the First and respectively Second International Conference on Responsible Innovation, hosted by the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) in 2011 and 2012. The conferences brought together the results of research projects under the NWO Research Program on Responsible Innovation, and other international research projects.

Deliverables from the European research project RRI Tools (see www.rritools.eu) were also identified for review.

In addition, all peer-reviewed, original research articles and reviews published in the Journal of Responsible Innovation were included. Policy documents, representing European guidelines on RRI, were included for review as well. We also included Dutch policies, since the Netherlands was one of the first European countries to establish a program in RRI (Fisher and Rip Citation2013).Footnote3

These sources were complemented with a database search on Scopus, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar. The titles and abstracts of peer-reviewed articles and reviews were searched for combinations of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’ or ‘Responsible Innovation’ and ‘indicators’, ‘criteria’, ‘requirements’. Finally, potentially relevant documents were added through examination of the reference lists of the initial source base.

Roughly 225 documents were identified in this way. These were then reviewed based on their titles and abstracts (or the introduction when an abstract was missing). Documents were retained if they were found to propose criteria for implementing RRI. We looked explicitly for arguments that addressed, developed or commented on the practical implementation of RRI. While this focus led us primarily to consider theoretical papers, some empirical studies were also included. For instance, although derived through discussions with RRI practitioners, Wickson and Carew (Citation2014) were retained because it proposes a coherent and elaborate framework of quality criteria and indicators for RRI. Similarly, although based on an intervention-oriented approach, Schuurbiers (Citation2011) was retained because it elaborates on enhancing an RRI dimension during research activities, namely reflexivity. In addition to having a focus on implementation, all retained documents had to be of normative rather than descriptive nature, so that normative goals and recommendations could be derived from them. Finally, we limited the documents retained to those with a focus on Western RRI practice and that were written in Dutch or English. Based on these criteria, 21 academic and 8 policy documents were retained.

Analyzing documents

Qualifiers were derived using the following process: First, recommendations for implementing RRI were identified in the retained documents and these qualifiers were then distributed over process and product criteria. Second, the process criteria were then further grouped according to the process dimensions described by Owen, Bessant, and Heintz (Citation2013, see ).

Table 1. Examples of coded text per process dimension.

shows the results of the initial coding analysis. It shows which qualifiers were associated with which RRI dimension, and by which article(s). For example, to ‘Diversify values’ was attributed to Inclusion in various sources, namely Sykes and Macnaghten (Citation2013), Blok (Citation2014), and van den Hoven et al. (Citation2013).

Table 2. Results of initial coding: qualifiers per RRI dimension.

After initial coding, we observed that various qualifiers appeared in more than one process dimension (see ). In-depth review of these ‘overlapping’ qualifiers suggested that in each case, one dimension related to and supported another dimension, highlighting potential relations among the concepts. ‘Define desirable outcome’, for example, appeared in both inclusion and anticipation: in anticipation, since it was represented in the literature as a critical element of anticipatory processes; in inclusion, since inclusion was represented in the literature as a critical element of defining desirability. Thus, inclusive processes were found to support anticipatory processes, leading to a more robust and a more relevant definition of desirable outcomes.

Table 3. Various qualifiers in the initial codes were associated with more than one RRI dimension (right).

This analysis resulted in a separation of qualifiers pertaining to the rationale and the implementation of a given process dimension. The rationale of a process dimension refers to any reasons that a researcher or innovator may have to apply the dimension. These were the qualifiers that were thought to support another RRI dimension, originally the ‘overlapping’ qualifiers described above. The implementation of a dimension refers to the remaining qualifiers, which were thought to determine the extent of the dimension’s success.

Framework development

We aimed to find factors that indicate quality in responsible processes and products (qualifiers) and synthesize a framework on implementing RRI. In this section the results of our literature review are presented in two sections: first we describe the qualifiers of RRI processes, second the qualifiers of RRI products. Qualifiers at the process level describe what type of research and innovation processes precede these outcomes and how these processes should be implemented in practice. The section on responsible processes is presented in five sub-sections, each pertaining to one of the following responsible process dimensions: transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation and responsiveness. For each dimension, we discuss the reasons that a researcher may have to use this dimension (rationale for place in the framework) as well as the factors that may determine its success (implementation in RRI practice). Under the rationale, we also discuss the ways in which a given process dimension is thought to influence other dimensions. Qualifiers at the product level describe the desired outcomes of RRI, including academic findings and marketable products. For a graphic representation of all interactions in our framework, see ; for a summary of our analysis, see .

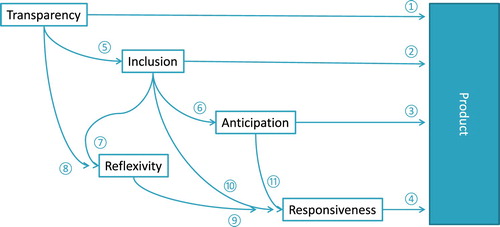

Figure 1. Interactions among RRI dimensions as inferred from the reviewed literature. All interactions presented in this overview are positive relationships, e.g. transparency was thought to support inclusion. Interactions ① to ⑪ are discussed under the rationales of the corresponding process dimension.

Table 4. Summary of process and product qualifiers thought to support responsible research and innovation per RRI dimension.

Responsible processes

To accommodate the focus of many innovation practitioners on products, qualifiers at the process level describe the processes that precede and lead to responsibly produced products. These may apply to any research or innovation process phase, including proposal writing, designing, validating and submitting research results.

Five process dimensions were found to contribute to the delivery of responsible products that are described below: transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation and responsiveness. For each, an overview of the reasons to apply (rationale) and the strategies to implement (implementation) are given. Some recommendations regarding the implementation of responsible processes concern more than one dimension, and are therefore summarized under ‘general recommendations’ at the bottom of this section.

Transparency

Activities that contribute to process transparency communicate the bases of decisions, including assessment criteria, and the distribution of the responsibilities to stakeholders and publics. Below, we discuss the rationale for this qualifier and its possible implementation options as described in the reviewed literature. Unlike other potential additions to the four process dimensions associated with RRI – such as ‘accountability’ (de Campos et al. Citation2017), transparency had relatively broad support in the reviewed literature, largely because of the various roles it can play in relation to the other RRI dimensions, as described below.

Rationale

Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) do not include Transparency as one of the process dimensions in RRI. This is possibly because they define process dimensions that support the responsiveness or ‘collective stewardship’ of innovation, and therewith focusing on substantive and forward-looking responsibility; how can decisions can be taken such that they lead to ‘better’ decisions? Transparency in this sense might be considered a backward-looking aspect of responsibility – providing justification and clarity on decisions that were taken already – and does therefore not contribute to the quality of those decisions. As such, one could argue that transparency cannot contribute to responsiveness directly in a forward-looking perspective, but only afterwards.

Indeed, the literature does not suggest that transparency can support responsiveness directly; however, it does present it as supporting other process dimensions and therefore as supporting responsiveness indirectly. Transparency is thought to support inclusive and reflexive processes and so contribute to responsiveness indirectly, in a forward-looking way. Transparency supports inclusive processes ⑤, since it is a requirement for meaningful dialogue (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013; Kupper et al. Citation2015) and trust between stakeholders (Kupper et al. Citation2015). Prior to any inclusion activity, all stakeholders should be properly informed about the issue at hand, since ‘societal actors can only appraise technological developments if they know about them first’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013). Transparency can also support reflexive processes ⑧, as being open about the bases of decisions allows others to challenge those bases (Wynne Citation2011).

Furthermore, transparency was found to support the delivery and adoption of responsibly produced products ①, as it could help to gain public support for research and innovation products (Sutcliffe Citation2011; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013) and so support the usability and market performance of a product.

Implementation

The literature asks researchers and innovators to be open about the drivers behind their decisions, or ‘the key commitments driving and structuring science’ (Wynne Citation2011). Specifically, authors emphasize transparency about the assessment criteria used, the role of stakeholders involved and any limitations that the researchers may experience with regard to transparency.

Transparency about assessment criteria asks researchers and innovators to be open to other stakeholders about the assessment criteria that they use for their decisions. In the literature this is referred to as ‘the values which underpin their work’ (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013) or ‘the social and ethical bases of R&D decisions’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013). Overall it seems that innovators are asked to communicate what advantages caused them to prefer one solution over another.

Transparency about the role of stakeholders asks researchers and innovators to be open about the role of stakeholders involved. This includes transparency about which stakeholder groups are involved in the decision-making process (Grunwald Citation2011; Kupper et al. Citation2015) and what is done with their input (Kupper et al. Citation2015).

Transparency about limitations acknowledges that full transparency about drivers is not always possible – intellectual property rights may prevent innovators from sharing the bases of their decisions. In this case Kupper et al. (Citation2015) recommends innovators to be also transparent about their limitations in this respect.

Inclusion

Inclusive processes are meant to take in the societal aspects of an innovation, often by engaging stakeholders. Of all the dimensions, we find that inclusion receives most emphasis in the RRI literature. The literature describes numerous reasons for being inclusive (rationale) and refers to a wide variety of processes as ‘inclusive’ (implementation).

Rationale

Inclusion is thought to contribute to more responsible outcomes in three ways: it can be used to (1) earn public support for a product, (2) learn from (the experience of) lay experts, and (3) share responsibilities for addressing a societal issue with stakeholders.

Earn public support asks stakeholders to be involved and enthusiastic about a product and is in no way geared towards altering or improving the product itself as a result of this interaction. Sutcliffe (Citation2011) for example proposes that under RRI citizens should be seen as co-creators of innovation to get ‘the buy-in’ of customers right at the start. Since public support contributes to both market competitiveness and acceptable usability by society, which are both product qualifiers of RRI, inclusion for public support may be seen as a partial means to responsible outcomes ②. It is important to note, however, that this type of inclusion does not require the innovator to respond to societal perspectives and is therefore not necessarily responsive (cf. Anon Citation2014a).

Learn from (the experience of) lay experts helps to reveal social and ethical aspects so as to inform decision-making during product development. Stakeholders are seen as experts (with experience from practice), whose opinion is valued and used to improve the future product. In this type of inclusion, the expertise of a research group is diversified (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Kupper et al. Citation2015), not only leading to a richer discussion (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013), but also to ‘better’ decisions (Stahl Citation2013).

As an enriching and informative experience, this type of inclusion is thought to support each of the other responsible processes. Through this type of inclusion, the purpose of and drivers behind research and innovation may be discussed (Von Schomberg Citation2013; Blok Citation2014), contributing to reflexivity ⑦. Such inclusive deliberation may also include underlying values, purposes and ideals, therefore moving beyond enriching or information provision to a more collective inquiry into the interactions of science and technology with public values and morality. From an innovation perspective, this type of inclusion can also help to identify risks (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013; Anon Citation2014b) and new possible routes to desired outcomes (Sutcliffe Citation2011; van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Blok Citation2014), supporting anticipatory processes ⑥. This type of inclusion is also thought to support responsiveness ⑩ directly. This is important, because according to (Anon Citation2014a), inclusion is not responsible unless a direct relationship with responsiveness can be shown. This type of inclusion may support responsiveness by adjusting research projects to the needs and concerns of citizens and stakeholders (Anon Citation2014b) or more precisely, by using these considerations as ‘non-functional’ design requirements (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013). This type of inclusion may support responsiveness by helping to ‘keep various options open’, to prevent ‘innovation lock-in and path dependency’ and to enhance corrigibility (Blok Citation2014).

Furthermore, this type of inclusion is thought to contribute to more responsibly-produced products ②. Through this type of inclusion, products are thought to become more relevant (Klaassen et al. Citation2014), ‘relevant to policy’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013) and socially desirable (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012) as well as more widely used and accepted (Correljé et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, this type of inclusion is thought to contribute to the scientific quality of outcomes (Anon Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015), because it benefits research planning, stimulates creativity and helps setting more worthwhile research goals (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013).

Share responsibilities with stakeholders serves to distribute the responsibilities for solving a societal challenge among stakeholders. In this type of inclusion there is no single innovator or researcher who includes or involves others – the group operates as a cross-disciplinary and inter-organizational team to solve a societal challenge at a systems level. This is described in the literature as ‘societal actors becom[ing] co-responsible’ (Von Schomberg Citation2013) and stakeholders becoming ‘mutually responsive’ (Von Schomberg Citation2011, Citation2013). This type is based on the idea that societal challenges, such as social inequality and global warming, are ‘wicked’ issues and can therefore not be solved by a single stakeholder (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015). Instead, as Klaassen et al. (Citation2014) put it, the ‘responsibility for our future is shared by all people and institutions affected by and involved in research and innovation practices’. This type of inclusion supports RRI, since it aims to develop and deliver products that are relevant to society ②.

All three of these types of inclusion intend to contribute to responsibly-produced products in one way or another. Yet the reviewed RRI literature also reports a fourth, completely different reason for being inclusive. Both the Dutch call for RRI proposals and the original RRI framework stress that researchers and innovators may have normative (often democratic) reasons for inclusion (Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013; Anon Citation2014a; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013), meaning that inclusion is on principle the right thing to do. In this context, studies stress that governments have a ‘moral responsibility’ (Sutcliffe Citation2011) and citizens may have ‘the right’ to be involved (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013). Similar to transparency, this type of inclusion does not necessarily contribute to responsibly-produced products, but is seen as a responsible act in its own right.

Implementation

Inclusion can only drive responsiveness effectively when it elicits meaningful contributions and allows the product or process to change as a result. Qualifiers for both of these aspects are listed below. First, qualifiers to elicit meaningful contributions are described.

Include many, diverse and fundamentally different stakeholders. For inclusion to effectively inform responsiveness, the relevant societal voices must be heard. Stakeholders should be drawn from the ‘right publics’ (Kupper et al. Citation2015) and represent ‘all relevant views’ (Balkema and Pols Citation2015; Anon Citation2014a). Since these norms are context-specific (Correljé et al. Citation2015), the literature reports on approaches to ensure that relevant voices are heard. The simplest and crudest way to make sure all relevant voices are heard is to include many perspectives or persons (Kupper et al. Citation2015). A somewhat more advanced method is to include a diverse set of stakeholders (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013). In the literature this is reported as a variety of stakeholder groups that should be engaged (Kupper et al. Citation2015), a range of stakeholders that should be included (Wickson and Carew Citation2014), or the wide configuration of deliberation in general (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). Stakeholders can furthermore enhance self-criticism and social learning if they are fundamentally different (Blok Citation2014). Cross-disciplinary inclusion may compose such fundamental differences; Von Schomberg (Citation2013) asks for a multidisciplinary approach and Kupper et al. (Citation2015) prompts researchers to move beyond engagement with stakeholders to include members of the wider public (transdisciplinary approach). Most specific are the criteria of Wickson and Carew (Citation2014), which prioritize transdisciplinary over interdisciplinary, interdisciplinary over multidisciplinary and multidisciplinary over monodisciplinary practices.

Frame discussion together with stakeholders. At the beginning of any inclusion activity, the stakeholders should be involved to frame the discussion together. In this way a broad spectrum of issues is defined (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013), which prevents important topics from remaining undiscussed as well as empowering stakeholders in the process. Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) emphasizes that these frames should not only concern characteristics of the product, but also the participation process itself. This view is shared by Kupper et al. (Citation2015), who suggests that research methods should also be a topic of conversation: ‘As complex issues might call for new methods or a synthesis of methods used in different disciplines, methodologies should be topic of deliberation within the practice.’

Empower stakeholders to contribute in order that they may act as effective drivers of learning and be able to contribute to the discussion. This means that all stakeholders should feel ‘empowered’ to challenge directions of research and innovation (Kupper et al. Citation2015). Therefore, power differences among parties should be compensated for to ‘create a level playing field’ (Balkema and Pols Citation2015) in which stakeholders feel free to express themselves. To this end, stakeholders could be trained to make meaningful contributions. Furthermore, researchers should support participants to develop their arguments and claims (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013), to make scientific contributions (Kupper et al. Citation2015) or to make persuasive and ‘rational arguments’ (Balkema and Pols Citation2015).

Besides making sure that stakeholders make meaningful contributions, researchers and innovators should make sure they are themselves adequately equipped to use the contributions and to allow the product or process to change in response to them. Below, three such qualifiers are described.

Include stakeholders from the outset. Policy documents generally emphasize that inclusion should be performed ‘from the outset’ (Anon Citation2014a) ‘at an early stage’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Anon Citation2014b). The rationale for this approach is pragmatic – the earlier the stage of development, the more ‘degrees of freedom’ available to change the direction of a new development (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013) and the longer the part of the trajectory that can still benefit from its results (Kupper et al. Citation2015). In the most extreme case, this means that stakeholders are included in the definition of the research objectives and priorities (Von Schomberg Citation2013).

When inclusion is used to support anticipation however, the preferred ‘earliness’ of inclusive activities should be balanced with other considerations around the timing of anticipatory activities (see ‘Anticipation’, below).

Include for normative or substantive reasons. If a product or service under development is to improve as a result of inclusion, inclusion should be based only on normative or substantive reasons (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013; Anon Citation2014a). The idea is that researchers with an instrumental reason (i.e. to gain public support for the product) to involve stakeholders cannot be receptive towards feedback because it was never their intention to change the product in response to the feedback. This constitutes a further critique of inclusion efforts aimed solely at gaining public support.

Be receptive towards feedback. Furthermore, during a discussion, researchers and innovators should adopt a receptive attitude towards learning, since ‘only because stakeholders can hear the voice of the other and can take the perspective of the other, they can become mutual responsive’ (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015). Blok (Citation2014) further states that the primary goal of dialogue in RRI should be to become critical towards ‘ourselves, i.e. towards our own interests and value frames’ rather than to ‘self-express’ in order to convince others. Similarly, Wickson and Carew (Citation2014) prefer the ‘active’ encouragement of mutual learning over simply being ‘open’ to mutual learning or even being ‘defensive in the face of counter-views or stakeholder questions’.

Reflexivity

Reflexive processes can help researchers and innovators to recognize which factors determine decision-making in a research and innovation process, and to understand the social and ethical effects of those decisions.

Rationale

Reflexivity is never mentioned as a means to produce responsible products directly, only indirectly through increasing responsiveness ⑨. Increased understanding of the factors that influence decision-making is thought to help prevent researchers and innovators from pursuing problematic influencing factors. In other words, reflection can affect ‘R&D practice, feeding back into ongoing research practices’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013) and shape ‘technological trajectories’ (Schuurbiers Citation2011), while the reproduction of ‘problematic underlying ethical, social and political commitments of the science’ (Wynne Citation2011) may be prevented or at least mitigated.

Implementation

Reflexive processes should help researchers and innovators to recognize what factors influenced their own decision-making and to challenge those drivers accordingly. Furthermore, researchers and innovators may gain a deeper understanding of the social and ethical implications of their actions.

Recognize own drivers. According to the literature, reflexive processes should help researchers and innovators to recognize three types of factors that influence his or her own decisions. First of all, researchers should learn how their own personal values can affect decision-making. These are referred to as ‘their own ethical, political or social assumptions’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013), ‘the values which underpin their work’ (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013), the ‘social and ethical bases for R&D decisions’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013) or the ‘value-based socio-ethical premises that drive research’ (Schuurbiers Citation2011). Next to their personal values, researchers should also learn how scientific norms influence their decisions. These norms are referred to as ‘the assumptions of research’ (Stahl Citation2013), ‘the methodological norms of the research culture, and the epistemological and ontological assumptions upon which science is founded’ (Schuurbiers Citation2011) and ‘the public justifications of science as impartial and innocently curiosity-motivated’ (Wynne Citation2011). Finally, the ‘institutional and contextual limitations’ of the research should also be identified and taken into account (Wickson and Carew Citation2014).

Challenge drivers. According to the literature, reflexive processes do not contribute to responsiveness if researchers and innovators do not question and challenge the drivers identified. This is indicated by the emphasis on a critical attitude in reflexivity, for example in Schuurbiers (Citation2011) ‘to critically reflect’, in Anon )Citation2014a) ‘to question’, in Wynne (Citation2011) ‘to challenge’ or most explicitly in Wickson and Carew (Citation2014) ‘with an effort to improve upon these conditions’. Being open (transparent) about the bases of decisions allows others to challenge those bases (Wynne Citation2011) and can therefore support reflexivity.

Understanding of how products impact society. Reflexivity should furthermore help researchers to understand the impacts of the product on society. In the literature this is referred to as ‘to understand ethical issues’ (Stahl Citation2013), to gain understanding of ‘social and ethical context’ (Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013) or to understand ‘what shapes society in the name of science’ (Wynne Citation2011). The difference with inclusive and anticipatory activities is that these reflexivity activities focus on gaining an understanding of, rather than only identifying societal issues.

Understanding how framing impacts the inclusion process. Yet researchers should not only reflect on how their products impact society, they should also reflect on how they themselves impact the inclusion process. van den Hoven et al. (Citation2013) e.g. emphasizes that through reflexivity, researchers should learn to recognize the importance of ‘framing issues, problems and the suggested solutions’ in public dialogue.

Anticipation

During decision making, anticipatory processes provide an overview of the choices available through an exploration of impacts and alternative routes to those impacts.

Rationale

The wide exploration of impacts and alternative routes is thought to support responsiveness ⑪, for a solid overview of choices supports the making of responsible decisions. Following de Jong et al. (Citation2015), anticipating potential impacts helps to ‘intervene on the basis of this acquired knowledge in the design stage’.

Anticipation is also thought to contribute to responsible products directly ③, for it is thought to result in products that are more ethically acceptable (see product qualifier usably by society, above) as they are more ‘resilient’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013) and ‘socially robust’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013).Footnote4

Implementation

Anticipatory processes help researchers and innovators to identify the societal impacts of innovation as well as the alternative routes towards and from those impacts.

Identify societal impacts. Where reflexive processes aim to gain a deeper understanding of outcomes and impacts, anticipatory processes simply help to identify them. By asking ‘what if … ?’ (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013) anticipatory processes help to identify impacts that may otherwise ‘remain uncovered and little discussed’ (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). Although the impacts explored should have a societal focus, these impacts can include social (Sutcliffe Citation2011), environmental (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Sutcliffe Citation2011; Kupper et al. Citation2015), ethical (Sutcliffe Citation2011; Anon Citation2014a) as well as economic (Kupper et al. Citation2015) aspects.

Define desirable societal impacts. Although it may be tempting to assume that anticipatory activities only support responsible research and innovation as long as potential risks are identified with them, multiple studies stress that anticipation should be used to identify potential desirable outcomes as well. The range of scenarios explored should be intended as well as unintended and desirable as well as problematic (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Kupper et al. Citation2015; Wickson and Carew Citation2014; Sutcliffe Citation2011). In this view, the key to implementing RRI is to see ethical and moral aspects of innovations as an inspiration rather than an obstacle. In the words of Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe (Citation2012), responsible innovation ‘seeks to consider not only what we do not want science and innovation to do, but what we do want it to do’. According to Zwart, Landeweerd, and van Rooij (Citation2014), this is implemented by asking what would be the right impacts and the right processes towards those impacts, rather than what impacts should be avoided.

Identify alternatives routes. Furthermore, anticipation aims to identify alternative routes to and from these impacts. In the literature, this process is referred to as ‘to think through various possibilities’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013), ‘to explore other pathways to other impacts’ (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013), to reveal ‘new opportunities’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), to ‘conceive of … a variety of R&D trajectories’ (Nordmann Citation2014), to ‘think through various options’ (Kupper et al. Citation2015), or to ‘assess and prioritize opportunities’ (Sutcliffe Citation2011).

Choose timing wisely. While the ‘correct’ timing of anticipatory activities is not a theme in the literature – since determining ‘the right moment’ for an intervention amounts to ‘technoscientific hubris’ (Nordmann Citation2014) – it is nevertheless clear that consideration needs to be given to timing of anticipatory processes. RRI discourses attempt to move beyond the well-known Collingridge dilemma of intervening too early or too late (e.g. Flipse, van der Sanden, and Osseweijer Citation2013; Nordmann Citation2014; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013) but what this means in practice is difficult to specify. Determining how to ‘well-time’ anticipatory processes cannot be done with a general formula; rather, context-specificity is necessary so that they are early enough to be constructive but late enough to be meaningful (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Kupper et al. Citation2015). One important timing consideration is captured by the idea of repetition in which anticipatory activities are carried out multiple times throughout the process (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Wickson and Carew Citation2014).

Responsiveness

Responsive processes concern the making of responsible decisions in research and innovation.

Rationale

The rationale for responsiveness is to support production of responsible outcomes and the delivery of responsibly produced products ④. In this sense, responsiveness supports responsible decision-making (Stahl Citation2013), thus leading to better products.

Implementation

According to the literature, substantial changes to research and innovation products or processes can support responsible innovation if they respond to societal perspectives as they emerge.

Respond to societal perspectives. Responsible processes respond to the social and ethical aspects of research and innovation. These aspects are variously described as ‘societal needs’ (Von Schomberg Citation2013), ‘the views, perspectives, and framings of others – publics, stakeholders’ (Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013), ‘societal and ethical implications’ (Anon Citation2014a), ‘public values’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013), ‘perspectives, views and norms’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), ‘stakeholder needs/interests/values/perceptions’ and ‘contextual changes (e.g. results by competing R&I groups; judicial changes, etc.)’ (Kupper et al. Citation2015). This suggests that responsible processes should be based on decisions that ‘[take] into account’ (Schuurbiers Citation2011) the norms, values and perspectives of both society at large and of specific stakeholders.

Respond to changing circumstances and perspectives. Yet values, norms and perspectives are subject to change, for instance, within ‘a changing information environment’ (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). Therefore, researchers and innovators should keep options open (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013) and respond to new knowledge as it emerges (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Kupper et al. Citation2015), ‘when the evidence of harm is uncovered’ (Sutcliffe Citation2011) or ‘when it becomes apparent that the current developments do not match societal needs or are ethically contested’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013).

Respond with substance. A response is only considered responsible when it has the potential for a substantial effect on research and innovation process. Responsible responses have ‘a material influence on the direction and trajectory of innovation itself’ (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013), adjusting courses (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), changing directions (Sutcliffe Citation2011), redirecting the innovation process (Anon Citation2014a), changing the direction or shape of innovation (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013) or changing the methods in ‘the course of the research and innovation practice’ (Kupper et al. Citation2015).

One way to enhance substantive capacity is to take societal values into account as non-functional requirements alongside the already existing functional requirements of the system (such as storage capacity, bandwidth, etc., van den Hoven Citation2014). Another way to enhance substantive capacity is to design research and innovation processes such that they allow periodic changes and ‘incremental adjustment’ (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013). According to Wickson and Carew (Citation2014), there should be ‘clear avenues for embedding responses’ to RRI activities and ‘evidence of potential to adapt’ in response to feedback. In particular, Wickson & Carew emphasize the repetition of both anticipatory and reflexive activities. To respond to potential societal considerations as they emerge, researchers should carry out RRI process activities ‘at various points’ throughout research and innovation processes rather than at ‘limited points’ or at only one point (see also Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Schuurbiers Citation2011). Thus, Wickson and Carew suggest that exemplary reflexive practice involves ‘periodic’ reflection, while great practice involves ‘occasional’ and good practice involves ‘one-off or ad hoc’ reflection.

General recommendations for implementation

Recommendations regarding the implementation of responsible process that concern more than one dimension are summarized here.

Couple inclusive, reflexive and anticipatory activities. Responsible decisions can only follow from a preparatory process consisting of inclusive, reflexive as well as anticipatory activities. These processes should be coupled and integrated (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), meaning that one process should be used to inform another and vice versa.

Repeat reflexive and anticipatory activities. Both anticipatory and reflexive activities should be repeated throughout research and innovation processes (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Schuurbiers Citation2011; Wickson and Carew Citation2014).

Apply established methods. Several studies stress the use of existing, tested and often formal methods for they offer a certain rigor and robustness. They are mentioned specifically in the context of anticipatory processes, where they support systematic thinking and overall resilience (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Wickson and Carew Citation2014), and reflexive processes, where they support a structured or semi-structured, analytic and explicit review of underlying considerations (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013; Schuurbiers Citation2011; Stahl Citation2013; Wickson and Carew Citation2014).

Combine methods. Furthermore, the methods should be used in combination so as to prevent the ‘technological determinism’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013) that a single method may provoke when applied too narrowly.

Responsibly produced products

Qualifiers at the product level concern the outcomes of research and innovation, including both its academic findings and the marketable products. Three product qualifiers were found in the literature (also see ): societal relevance (including acceptability and desirability), market competitiveness and scientific quality.

Societal relevance

All sources stress that a product can be considered responsibly produced only if it has the potential to make a relevant and valued contribution to society. Although some stress intentionality (Owen, Bessant, and Heintz Citation2013), most authors characterize the societal relevance of a product by a combination of the relevance of its outcomes and the acceptability of its form.

Relevant outcomes

‘Responsible outcomes’ are both relevant to and valuable for society as a whole or in ways that do not harm other aspects of society. Such outcomes have been described as ‘socially desirable’ impacts (Von Schomberg Citation2013; Klaassen et al.Citation2014; Stahl Citation2013), when they align with grand or ‘societal challenges’ (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013), take into account ‘societal objectives’ (Von Schomberg Citation2014) or contribute to the ‘public or collective good’ (de Jong et al. Citation2015). de Jong et al. (Citation2015) suggest that responsible outcomes may be relevant or valuable for ethical, social, environmental, scientific, health-related, legal, cultural or political reasons. The resolution of vexing social issues and the contribution to sustainable development receive particular emphasis in the literature and are addressed below.

Resolution of social issues. Responsibly produced products are particularly relevant when they help resolve social issues. Since social issues are defined in terms of underlying norms and public values, responsible products and outcomes in this case should advance these often neglected norms and values. The Dutch program for responsible innovation, for example, calls for projects that focus on supporting justice, equality and autonomy (Anon Citation2014a). The Treaty of the European Union similarly calls for social justice and equality (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Von Schomberg Citation2014; Von Schomberg Citation2013; Zwart, Landeweerd, and van Rooij Citation2014). ‘Grand challenges’ are another common representation of social issues that must be addressed (e.g. Von Schomberg Citation2014). It is important to note that the ‘responsible outcomes’ qualifier does not in itself answer the question of which processes, products or services would help resolve specific social issues. Rather, such resolution of social issues will depend heavily on social contexts and can take various forms in different research contexts. Given that different stakeholders will have different ideas about what qualifies as ‘responsible’ for each of these possible contexts, the value of this RRI implementation qualifier is in pointing to the need for dialogue, debate and reflection on diverse values and stakeholder perspectives.

Contribution to sustainable development. Responsible products are considered particularly relevant when they contribute to sustainable development. In contrast to the WWF, which focuses on the environmental aspects of sustainability (Owen, Stilgoe et al. Citation2013), RRI literature tends to emphasize that sustainable development should balance environmental with social and economic interests (Von Schomberg Citation2013; Sutcliffe Citation2011; van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Koops Citation2015; Von Schomberg Citation2014).

Viable forms

Even the most socially relevant products cannot achieve their goals if they are not acceptable and used. For this reason, the literature stresses that a responsible product should not only aim for certain impacts and outcomes, but also be embodied in viable – that is, in acceptable and usable – forms. To be viable, a product needs to be ethically acceptable, sufficiently concrete and – to be feasible in current economies – also market competitive.

Ethically acceptable. Multiple sources stress that responsible outcomes should be ethically acceptable. Research and innovation outcomes should comply with fundamental rights such as the right for privacy (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Koops Citation2015; Von Schomberg Citation2014; Von Schomberg Citation2013; Klaassen et al. Citation2014; Kupper et al. Citation2015) and should be safe (Von Schomberg Citation2013; Zwart, Landeweerd, and van Rooij Citation2014; van den Hoven et al. Citation2013; Von Schomberg Citation2014). But, although widely accepted, human rights lack specificity and need to be translated into more applicable norms: to this end, Stahl (Citation2013) mentions several specific norms which may be appropriate for RRI, such the UNESCO Draft Code of Ethics for the Information Society. This includes a code on how every person, irrespective of where they live, their gender, education, religion, or social status, should e.g. ‘be able to benefit from the Internet’. Which codes are relevant in which contexts, should be discussed case by case.

Concrete products. Responsible outcomes should also be sufficiently concrete. Wickson and Carew (Citation2014) for example call for placing higher value on ‘a successful solution’ than on ‘the creation of decontextualized knowledge’. A similar call is made by the Dutch program for responsible innovation, which requires a research project to make tangible contributions to innovation (Anon Citation2014a).

Viable in economic context. Von Schomberg (Citation2013) states that although responsible innovation should go beyond market competitiveness, competitiveness remains a necessity for the viability of responsible products in contemporary economies. In his view a socially relevant product cannot achieve its goals if it does not sell, otherwise it will not be used.

Market competitiveness

In contrast to Von Schomberg (Citation2013), who sees viability in the current market economy as a precondition for social relevance, policy documents portray market competitiveness as a goal of responsible innovation on its own. Here, responsible products should strengthen the (inter)national economy and make research funding more efficient. This seems to have been the primary drive of the European Commission to institutionalize RRI; an evaluative report issued by the European Commission described the motives for institutionalizing RRI as follows:

there are many examples in which the outcomes of research has been contested in society, because societal impacts and ethical aspects have not adequately been taken into consideration in the development of innovation. In many cases, the related research funding is wasted … RRI has the potential to make research and innovation investments more efficient, while at the same time focusing on global societal challenges. (van den Hoven et al. Citation2013, 16)

Scientific quality

According to one government report (Anon Citation2014b), the promise of high-quality scientific outcomes is one of the primary reasons for the Dutch government to promote RRI. The view that responsible research should also lead to high-quality scientific research is shared by Wickson and Carew (Citation2014), who include various indicators of scientific quality in their framework (repeatability, reliability, novelty and elegance).

Discussion and conclusion

Framework summary

The normative, theoretical and empirical literature reviewed described both product and process qualifiers. This review distinguished five process qualifiers of RRI (transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation and responsiveness) and three product qualifiers (societal relevance, market competitiveness and scientific quality) (see for a summary). Furthermore, this review explicated the interactions among RRI dimensions (see ). Transparency, inclusion, anticipation and responsiveness are each thought to contribute directly to the delivery of responsible products. Inclusion, reflection and anticipation are thought to support responsiveness, while inclusion is thought to support reflexivity and anticipation, and transparency in turn is thought to support inclusion and reflection.

Comparing the RRI implementation framework with other RRI frameworks

Since we based our framework on early RRI literature (published between 2011 and 2015), we compared our framework with RRI frameworks published since 2015 (Foley, Bernstein, and Wiek Citation2016; Jirotka et al. Citation2016; Lubberink et al. Citation2017b; Macnaghten, Owen, and Jackson Citation2016; Mejlgaard, Bloch, and Madsen Citation2018; Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar Citation2017; Silva et al. Citation2018; Stahl and Coeckelbergh Citation2016; Stahl et al. Citation2017; Tait Citation2017; Van de Poel et al. Citation2017).

Like our framework, most frameworks published since 2015 aimed to make RRI more concrete to support its implementation in practice (Foley, Bernstein, and Wiek Citation2016; Lubberink et al. Citation2017b; Mejlgaard, Bloch, and Madsen Citation2018; Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar Citation2017; Silva et al. Citation2018; Stahl et al. Citation2017; Van de Poel et al. Citation2017). Foley, Bernstein, and Wiek (Citation2016) for example add the dimension ‘coordination’ to make more explicit how the other dimensions, especially engagement, should be performed, Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar (Citation2017) present an overview of RRI approaches and methods and Stahl et al. (Citation2017) propose a maturity model, showing how implementation of RRI in industry should develop over time.

While several of these frameworks emphasize that responsible processes do not guarantee responsible products (e.g. Lubberink), hardly any of the frameworks specified under which conditions responsible processes may or may not lead to responsible products. In fact, very few frameworks specified the relationships between processes and products. Instead, many frameworks adopted either a product approach, which adheres to the European Commission’s RRI ‘keys’ (e.g. Mejlgaard), or a process approach, which builds on the process dimensions introduced by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013). The frameworks that did explicitly connect processes with products were in line with the relationships that we found. For example Jirotka et al. (Citation2016) proposed to specify product, process, purpose and people aspects for each of the four dimensions, whereby each of these four p’s centers on one specific challenge within ICT research. As such, it emphasized that each of the process dimensions has the potential to contribute to responsible outcomes (i.e. products and purposes), and that ‘people’ matter for all process dimensions. This is in line with our framework, which argues that almost all processes contribute to responsible products directly and that inclusion drives the other processes, and it enriches our framework by attending more explicitly to intentionality (see section ‘Societal relevance’) and actors (see ‘Inclusion’).

Overall, many of the frameworks published since 2015 call for more insights into the workings of RRI in practice and several have called for more insights into the links between responsible processes and products. Our framework contributes to this discussion by making explicit how responsible processes are thought to contribute to each other and to responsible products.

Discussion of framework

Although the reviewed documents differed greatly in terms of terminology, orientation, depth and emphasis, we could identify three common product dimensions and five common process dimensions, indicating that these documents indeed share some core characteristics. While the documents represent more than one ‘flavor’ of RRI (Stahl Citation2013), we combine these flavors into a framework, by explicating RRI qualifiers and dimensions that are found in RRI studies and policy documents.

A framework of such widely supported RRI qualifiers may support implementation of RRI by providing clarity on ‘what good quality RRI looks like’ (Wickson and Carew Citation2014). Such clarity supports research funding bodies that seek to select RRI research proposals and researchers and innovators who seek to develop and exercise their capacity to undertake toward RRI or who want to improve the societal relevance alongside the performance of their work.

Next to developing a set of qualifiers, this review explicated and visualized which interactions the normative, theoretical and empirical literature reviewed expects, among RRI dimensions. This is an answer to Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013), who emphasize that dimensions should be carried out together in an integrative manner and that dimensions could reinforce each other. Explicating the theoretical interactions in our framework can facilitate the implementation of RRI, as it justifies productive coupling among specific dimensions, allowing each interaction to be monitored, tested and further developed and discussed.

This study does not include all theoretical or empirical work on RRI. A complete review of all such work was beyond the scope of this study, which focused on a select set of documents produced over a pre-defined time period. At the same time, we acknowledge that an entire review of the RRI literature would be of tremendous value for enhancing the implementation framework, and that a fuller review of empirical studies in particular would likely provide a basis for additional concrete indicators of quality and insights emerging from concrete interactions rather than from the more theoretical literature we primarily focused on. One advantage to our more limited study was that it explicates how RRI dimensions can support each other, since only qualifiers of RRI were reviewed. The framework should be applied in case studies to indicate whether the theoretical workings of RRI as presented here are feasible in practice. For a follow-up study, one point of attention could be to elicit which dimensions conflict with each other in practice, for example, among transparency, high-quality science, and market viability (see Brand and Blok Citation2019).

‘RRI short-cuts’

Three process dimensions were found to contribute to the delivery of responsible products directly, according to some literature, and so bypassed the dimension of ‘responsiveness’ (interactions 1–3 in ). In our study, responsiveness was described as the making of substantial changes in response to consideration of societal perspectives. As such, these ‘bypassing interactions’ may not improve product characteristics, only improve public perception of a product. In other words, they can contribute to the usability and competitiveness of a product that may or may not already be responsible, but they can neither create a responsible product nor justify an irresponsible one. These are serious considerations, especially since Owen, Bessant, and Heintz (Citation2013) describe responsiveness as ‘key’ to RRI and some (Anon Citation2014a; Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013) consider any ‘instrumental’ reasons to include stakeholders (such as to improve the perception of a product) by definition to not be responsible. This kind of RRI ‘window dressing’or ‘responsibility-wash’ (Randles et al. Citation2015) can be discouraged from the perspective of responsible practices. It seems that direct interactions with product qualities, without being integrated with the other RRI process dimensions, puts transparency, inclusion and anticipation at risk of being used as ‘short-cuts’, ways to seemingly responsibly develop products without having to actually change the product in response to societal perspectives.

Outlook

Although limited in its scope, this literature review combined a set of widely supported RRI qualifiers that may be central to the concept of socially responsive research and innovation into a framework that could help operationalize RRI in practice. We explicated and graphically represented interactions among RRI dimensions as described in the literature. These suggest productive combinations of RRI dimensions that contribute to responsiveness and raises questions about the use of dimensions in ways that fail to contribute to responsiveness. We call for new empirical research to investigate the applicability of this conceptually derived framework in practice as well as studies of this framework against the background of empirical studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Aafke Fraaije is a PhD student at the Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The Athena Institute studies the dynamics between science and society with the aim to enrich science with increased societal legitimacy. Aafke’s personal research project aims to involve citizens in smart city developments through art and science fiction.

Steven M. Flipse is assistant professor in Science Communication at the Delft University of Technology. The Science Communication research group studies communication design in support of innovation practice. Steven’s personal research focusses on interaction design for the stimulation of responsible innovation.

ORCID

Aafke Fraaije http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0994-4553

Steven M. Flipse http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7400-1490

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Owen and Pansera (Citation2019) note that RRI is often more closely linked with European policy funding categories than with academic discourses. While we acknowledge their point, we refer to a more encompassing notion of RRI throughout this article for the sake of simplicity and accessibility.

2 Foley, Bernstein, and Wiek (Citation2016) and also call for adding “Accountability” to the framework developed by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013).

3 For this review the following publications were included: a governmental publication on Dutch research policy (Anon Citation2014b), the call for proposals by NWO for their funding program “Responsible Innovation” (Anon Citation2014a) and the European Work Program 2014–2015 for Horizon 2020 (Anon Citation2015).

4 We acknowledge also the broad range of empirical literature with experiences in design thinking, scenario workshops, foresight activities and other technology assessment methods. However, we do not go into detail here with regard to the findings of these papers since they did not appear in our literature search.

References

- Anon. 2014a. Call for Proposals MVI, Den Haag. http://www.nwo.nl/binaries/content/documents/nwo/algemeen/documentation/application/gw/maatschappelijk-verantwoord-innoveren—call-for-proposals/Call+for+Proposals_MVI2014-pdf.pdf.

- Anon. 2014b. Wetenschapsvisie 2025, Den Haag. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/rapporten/2014/11/25/wetenschapsvisie-2025-keuzes-voor-de-toekomst/wetenschapsvisie-2025-keuzes-voor-de-toekomst.pdf.

- Anon. 2015. Horizon 2020 – Work Programme 2014–2015. http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2014_2015/main/h2020-wp1415-swfs_en.pdf#14.

- Balkema, A., and A. Pols. 2015. “Biofuels: Sustainable Innovation or Gold Rush? Identifying Responsibilities for Biofuel Innovations.” In Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches, and Applications, edited by B.-J. Koops, I. Oosterlaken, H. Romijn, T. Swierstra, and J. van den Hoven, 283–303. Cham: Springer.

- Blok, V. 2014. “Look Who’s Talking: Responsible Innovation, the Paradox of Dialogue and the Voice of the Other in Communication and Negotiation Processes.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.924239.

- Blok, V., and P. Lemmens. 2015. “The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation - Three Reasons Why It is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches and Applications, 19–35. Cham: Springer.

- Brand, T., and V. Blok. 2019. “Responsible Innovation in Business: A Critical Reflection on Deliberative Engagement as a Central Governance Mechanism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (1): 4–24.

- Correljé, A., E. Cuppen, M. Dignum, U. Pesch, and B. Taebi. 2015. “Responsible Innovation in Energy Projects: Values in the Design of Technologies, Institutions and Stakeholder Interactions.” In Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches and Applications, edited by B.-J. Koops et al., 183–200. Cham: Springer.

- de Campos, A. S., S. Hartley, C. de Koning, J. Lezaun, and L. Velho. 2017. “Responsible Innovation and Political Accountability: Genetically Modified Mosquitoes in Brazil.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (1): 5–23.

- De Hoop, E., A. Pols, and H. Romijn. 2016. “Limits to Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 110–134. doi:10.1080/23299460.2016.1231396.

- Eden, G., M. Jirotka, and B. Stahl. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation: Critical Reflection into the Potential Social Consequences of ICT.” In IEEE 7th International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), 1–2. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

- Fisher, E., and A. Rip. 2013. “Responsible Innovation: Multi-level Dynamics and Soft Intervention Practices.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 165–183. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Flipse, S. M., M. C. A. van der Sanden, and P. Osseweijer. 2013. “The Why and How of Enabling the Integration of Social and Ethical Aspects in Research and Development.” Science and Engineering Ethics 19 (3): 703–725.

- Foley, Rider W., Michael J. Bernstein, and Arnim Wiek. 2016. “Towards an Alignment of Activities, Aspirations and Stakeholders for Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 209–232.

- Grunwald, A. 2011. “Responsible Innovation: Bringing Together Technology Assessment, Applied Ethics, and STS Research.” Enterprise and Work Innovation Studies 7: 9–31.

- van den Hoven, J., N. Doorn, T. Swierstra, B.-J. Koops, and H. Romijn, eds. 2014. Responsible Innovation 1: Innovative Solutions for Global Issues. Dordrecht: Springer.

- van den Hoven, J. 2014. “Responsible Innovation: A New Look at Technology and Ethics.” In Responsible Innovation 1: Innovative Solutions for Global Issues, edited by J. van den Hoven, N. Doorn, T. Swierstra, B. J. Koops, and H. Romijn, 3–13. Dordrecht: Springer.

- van den Hoven, J., K. Jacob, L. Nielsen, F. Roure, L. Rudze, J. Stilgoe, and K. Blind. 2013. Options for Strengthening Responsible Research and Innovation. Brussels: European Union.

- Jirotka, M., B. Grimpe, B. Stahl, G. Eden, and M. Hartswood. 2016. “Responsible Research and Innovation in the Digital age.” Communications of the ACM. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:b8d67d60-6115-4ed0-b8d8-15d5d501b1f5.

- de Jong, M., F. Kupper, A. Roelofsen, and J. Broerse. 2015. “Exploring Responsible Innovation as a Guiding Concept - the Case of Neuroimaging in Justice and Security.” In Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches and Applications, 57–84. Cham: Springer.

- Klaassen, P., F. Kupper, M. Rijnen, S. Vermeulen, and J. Broerse. 2014. D1.1 Policy Brief on the State of the Art on RRI and a Working Definition of RRI. RRI Tools: Fostering Responsible Research and Innovation. Netherlands: Athena Institute, VU University Amsterdam.

- Koops, B.-J. 2015. “The Concepts, Approaches and Applications of Responsible Innovation - An Introduction.” In Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches and Applications, 1–15. Cham: Springer.

- Koops, B. J., I. Oosterlaken, H. Romijn, T. Swierstra, and J. Van Den Hoven. 2015. Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches, and Applications. Cham: Springer.

- Kupper, F., P. Klaassen, M. Rijnen, S. Vermeulen, and J. E. W. Broerse. 2015. D1.3 Report on the Quality Criteria of Good Practice Standards in RRI. RRI Tools: Fostering Responsible Research and Innovation. Netherlands: Athena Institute, VU University Amsterdam.

- Lubberink, R., V. Blok, J. Van Ophem, and O. Omta. 2017a. “Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices.” Sustainability 9 (5). https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/5/721.

- Lubberink, R., V. Blok, J. van Ophem, and O. Omta. 2017b. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: Lessons From Responsible-, Social-and Sustainable Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation 3, 181–207. Cham: Springer.

- Macnaghten, P., R. Owen, and R. Jackson. 2016. “Synthetic Biology and the Prospects for Responsible Innovation.” Essays in Biochemistry 60: 347–355. doi:10.1042/EBC20160048.

- Mejlgaard, N., C. Bloch, and E. B. Madsen. 2018. “Responsible Research and Innovation in Europe: A Cross-Country Comparative Analysis.” Science and Public Policy 46 (2): 198–209.

- Nordmann, A. 2014. “Responsible Innovation, the art and Craft of Anticipation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.882064.

- Owen, R., J. Bessant, and M. Heintz. 2013a. Responsible Innovation - Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society. Chichester: Wiley.

- Owen, R., P. Macnaghten, and J. Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760.

- Owen, R. and Pansera, M., 2019. Responsible Innovation and Responsible Research and Innovation. In Handbook on Science and Public Policy, 26–48. Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Owen, R., J. Stilgoe, P. Macnaghten, M. Gorman, E. Fisher, and D. Guston. 2013b. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 27–50. Chichester: Wiley.

- Pellé, S. 2016. “Process, Outcomes, Virtues: the Normative Strategies of Responsible Research and Innovation and the Challenge of Moral Pluralism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 233–254.

- Randles, S., J. Edler, C. Gough, P. B. Joly, N. Mejlgaard, N. Bryndum, A. Lang, R. Lindner, and S. Kuhlmann. 2015. Lessons from RRI in the Making. Res-AGorA Policy Note# 1.

- Ribeiro, B., L. Bengtsson, P. Benneworth, S. Bührer, E. Castro-Martínez, M. Hansen, and P. Shapira. 2018. “Introducing the Dilemma of Societal Alignment for Inclusive and Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (3): 316–331.

- Ribeiro, B. E., R. D. J. Smith, and K. Millar. 2017. “A Mobilising Concept? Unpacking Academic Representations of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23: 81–103. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9761-6.

- Schuurbiers, D. 2011. “What Happens in the Lab: Applying Midstream Modulation to Enhance Critical Reflection in the Laboratory.” Science and Engineering Ethics 17 (4): 769–788.

- Silva, H. P., P. Lehoux, F. A. Miller, and J. L. Denis. 2018. “Introducing Responsible Innovation in Health: a Policy-oriented Framework.” Health Research Policy and Systems 16 (1): 90.

- Stahl, B. C. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation: The Role of Privacy in an Emerging Framework.” Science and Public Policy 40 (6): 708–716.

- Stahl, B. C., and M. Coeckelbergh. 2016. “Ethics of Healthcare Robotics: Towards Responsible Research and Innovation.” Robotics and Autonomous Systems 86: 152–161.

- Stahl, B. C., G. Eden, and M. Jirotka. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation in Information and Communication Technology: Identifying and Engaging with the Ethical Implications of ICTs.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, M. Heintz, and J. Bessant, 199–218. London: Wiley.

- Stahl, B., M. Obach, E. Yaghmaei, V. Ikonen, K. Chatfield, and A. Brem. 2017. “The Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Maturity Model: Linking Theory and Practice.” Sustainability 9 (6): 1036.

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733313000930.

- Sutcliffe, H. 2011. A Report on Responsible Research & Innovation. http://www.matterforall.org/pdf/RRI-Report2.pdf.

- Sykes, K., and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Responsible Innovation – Opening up Dialogue and Debate.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 85–108. London: Wiley.

- Tait, J. 2017. “From Responsible Research to Responsible Innovation: Challenges in Implementation.” Engineering Biology 1 (1): 7–11.

- Thorstensen, E., and E.-M. Forsberg. 2016. “Social Life Cycle Assessment as a Resource for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (1): 50–72.

- Van de Poel, I., L. Asveld, S. Flipse, P. Klaassen, V. Scholten, and E. Yaghmaei. 2017. “Company Strategies for Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI): a Conceptual Model.” Sustainability 9 (11): 2045.

- Von Schomberg, R. 2011. Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/mep-rapport-2011_en.pdf.