ABSTRACT

We investigate opening up, a crucial aim of responsible innovation, in the situation of companies initiating sector-wide change in order to take societal responsibility. Two case studies in agriculture were conducted, using a framing perspective that enlightens how issues are (re-)defined and acquire meaning in conversations. For both industry-led innovation initiatives, this showed when and how the initiatives’ issue frames opened up and closed down. The results suggest that the inclusion of actors is not the panacea for opening up the innovation processes, given that responsiveness seemed more relevant. Furthermore, we confirm that closing down may occur simultaneously with opening up and as such is an inherent part of responsible innovation processes. Hence, in addition to the advocated opening up, the question of how to balance it with closing down in order to arrive at collaborative action deserves full attention.

Introduction

In both the policy and scientific literature on responsible research and innovation (RRI), inclusion or inclusiveness is considered to be a crucial element of this new governance philosophy. It seeks ‘ … a rise in the inclusion of new voices in the governance of science and innovation as part of a search for legitimacy’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1571). In practice, this means that participatory, tailor-made techniques for public dialogues are used to include the public, NGOs and other stakeholders that are usually absent from science, development and innovation, with the aim to open up the innovation process. The subject of the deliberations in among others consensus conferences, multi-stakeholder partnerships, public juries and other more or less structured forms of participation, not only concerns the anticipated potentially negative societal impacts of new technologies, like in Risk Assessment, but also the motivations for and goals of their development (Stirling Citation2008; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013).

Most RRI studies concern emerging, highly contested technologies such as nanotechnology and geoengineering (Pandza and Ellwood Citation2013). Innovation however, mainly takes place in and around private companies in innovation networks of producers, consumers, education institutes and intermediaries, in which scientists and governments often play a distant role (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015). Private companies are dependent on other actors when they want to take societal responsibility for their production processes. In the past decades, some have sought the cooperation with public organisations and NGOs and vice versa (van Tatenhove and Goverde Citation2002; Van Huijstee and Glasbergen Citation2010). These forms of inclusive governance indicate that the industry has an important role to play in responsible innovation. Hence, there is a growing body of studies on responsible innovation in a business context. They explore to what extent and how RRI frameworks are relevant for and can be applied to innovations instigated by private actors operating in a competitive market (Scholten and Blok Citation2015).

As in RRI literature, responsible innovation (RI) approaches tend to presume that inclusion of stakeholders and the wider public is crucial. Brand and Blok (Citation2019) critically examine whether deliberative engagement is suitable for innovation in industry given tensions between among others transparency and competitive advantage. They suggest to modify the ideal of inclusion and make it more realistic in terms of what companies could achieve, by focusing on outcomes in addition to or even instead of procedural criteria.

Generally, the expected outcome of the involvement of actors as a feature of a R(R)I-process is framed as an opening up of the research, innovation and development process with regard to issues that contest dominant assumptions, values and interests. This outcome subsequently informs science and innovation policy specifically and/or the innovation process in general (see e.g. Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe (Citation2012)). This perspective on RRI is problematic for several reasons. First, the assumption about the positive relation between inclusion of actors and opening up has been debated. Public participation by invitation in workshops and similar settings does not necessarily help to challenge assumptions underlying scientific choices and normative issues (Jamison and Wynne Citation1998; Wynne Citation2007). It is also doubted whether participatory approaches, such as forms of public appraisal or stakeholder involvement, are the only way to facilitate opening up. They are not by definition more effective than traditional expert analyses (Stirling Citation2008; van Mierlo et al. Citation2012).

Secondly, the assumption of opening up being the desirable outcome of a responsible innovation process, can be questioned. According to several scholars both opening up and closing down are needed to direct change processes towards socially desirable ends. As opening up is basically a widening of the problem, the solutions space and/or the governance system, closing down can be understood as reducing complexity and ambivalence. In light of these criticisms, the key challenge for responsible innovation can be reformulated as identifying ways to combine and balance processes of opening up and closing down (Voβ, Bauknecht, and Kemp Citation2006). The aim of this article is to investigate empirically in what situations and how actors identify such combinations and whether opening up and closing down are indeed balanced since few people have taken up this challenge thus far (Regeer Citation2009; Westling et al. Citation2014).

In this article, we analyse two case studies in the agricultural sector, for instigating a wider debate on the need of opening up and its relation with inclusion of actors and other dimensions of R(R)I. We do so by investigating how groups of companies that want to take societal responsibility in a co-evolutionary innovation process, shape and reshape problem definitions and solutions. This is done from a framing perspective that enlightens how issues are defined and acquire meaning in conversations. The two case accounts at the core of the study are initiatives for sustainable development. In these initiatives, entrepreneurs and companies collaborate with other actors and strive for structural change in agro-food chains in order to guarantee their own future by taking societal concerns into account. By scrutinising the assumed relation between actor involvement (inclusion) and the opening up of issue frames, we shed new light on the importance and the role of inclusion in responsible innovation, and, in doing so, on the relation between opening up and closing down, while contributing to the wider discussion about the latter.

Theoretical perspective

Opening up and the efficacy paradox of complexity

At its core, opening up concerns creating a greater variety of options, in order to prevent incumbents’ interests, established policy and overriding values to dominate the innovation process. The concept is often used in the context of complexity, asserting that opening up means the revealing of silenced voices, uncovered opportunities, ignored uncertainties, neglected issues, unexpected possible solutions, and the like. It could hence result in a greater diversity of innovation pathways. In his ground-breaking article on opening up Stirling (Citation2008, 280) states that technology appraisals leading to an opening up would result in:

… plural and conditional policy advice … . This involves systematically revealing how alternative reasonable courses of action appear preferable under different framing conditions and showing how these dependencies relate to the real world of divergent contexts, public values, disciplinary perspectives, and stakeholder interests … . Although the results may be correspondingly ambiguous or equivocal about what constitutes the single best way forward, the openness of the process renders those courses of action that are positively evaluated and all the more collectively robust.

Voβ, Bauknecht, and Kemp (Citation2006) are among the first to choose a radically different approach. According to them, while being contradictory, opening up (a widening of the problem, the solutions space and/or the governance system) and closing down (reducing complexity and ambivalence in order to keep focus in action) are both needed for socio-technological systems to develop towards sustainability. This perspective helps extending the view of responsible innovation from the design and decision making in research and development to other types of innovation-related processes that are also driven to tackle complex societal and ethical concerns.

Regarding opening up and closing down as opposite processes, Voβ, Bauknecht, and Kemp (Citation2006, 431) speak of the efficacy paradox of complexity:

Opening up of the discussion of future societal development towards a broader set of considerations and wider system boundaries in terms of levels of policy, geographical boundaries and the inclusion of future generations goes hand in hand with increasing difficulties to act.

To overcome the tension between opening up and closing down, Grin and Weterings (Citation2005) argue that selective openings should be sought for; particular rules embedded in social systems should be opened up, not all. They describe potential forms of closing down that are valuable for system innovation towards a sustainable development. This would be the case if exploration with scenarios would be closed with normative future visions; dialogues would be closed down in an action-oriented coalition, and anticipation would be followed up by the closure of embedding novelties in a socio-technological system.

The acknowledgment of the occurrence as well as the need of closing down is useful. Such presentations of the efficacy paradox however, still build firmly on normative frameworks. Opening up and closing down are regarded as separate phases. Moreover, closing down is merely supposed to follow a phase of opening up. The critique to such accounts of the efficacy paradox can best be phrased by quoting Walker and Shove (Citation2007). They state that such descriptions play down: ‘the important point that forms of opening also represent moments of closure (and vice versa). In addition, it supposes that debates, problems and questions can be ‘opened’ and closed at will’ (Walker and Shove Citation2007, 222–223). Thus, an empirical orientation rather than a normative framework, seems of great importance in the further investigation of the roles and forms of opening up and closing down in (responsible) innovation and how they are instigated by features of the innovation process. In this regard, framing theory provides an interesting lens.

Opening up and closing down in issue framing

The framing perspective ‘ … starts from the observation that people seek to comprehend complex situations and make sense of ambiguous issues in and through conversations … ’ (Dewulf and Bouwen Citation2012, 170). Framing is essentially a process of making an issue salient by selecting certain aspects of a situation or event and leaving others out (Gray Citation2003; Dewulf et al. Citation2009). Technological and social innovations acquire meaning through the process of people engaging in everyday conversations, holding formal gatherings and exchanging written messages. This happens often in for technology developers, unexpected ways, because people’s responses depend not only on technical specifications, but also their own established practices and preferences (Veen et al. Citation2011; Bouwman et al. Citation2009). Framing serves social purposes related to the issue at stake, such as putting an issue on the political agenda, mobilising supporters, and presenting specific solutions as self-evident. People communicate differently about issues in different contexts, depending on their conversation partners, presumed target groups, the responses, the location, the timing et cetera.

The associated complexity of responsible research and innovation underscores the role of selective framing. In situations in which complexity abounds and uncertainties and controversies are inherent, framing a problem or innovation is by definition selective, no matter how many actors are included in the dialogue. When diverse actors meet, they bring along different issue frames. Hence, frame diversity exists in every gathering of diverse actors. Involving more actors will increase the diversity of issue frames. However, an important conclusion of framing studies is that the inclusion of actors does not necessarily mean that all concerns become part of an integrated frame. Alternative outcomes of actor involvement are connections between the frames as well as frame polarisation (Dewulf and Bouwen Citation2012).

Another important lesson is that issue framing influences who will be involved in a decision making or innovation process. Specific issue frames imply the inclusion and exclusion of specific actors. van Lieshout et al. (Citation2013, 38) for instance show how in a regional conflict the use of the frame of ‘sustainability at a higher level’ by politicians excluded the concerns of local citizens who framed the issue as an ‘accumulation of local developments’. Hence, actor involvement and issue framing mutually influence one another.

As any framing involves selecting salient aspects in and leaving other aspects out, we could assume that opening up and closing down take place simultaneously. The analysis of the framing and reframing of the integrated issues of responsible innovation initiatives hence provides a good starting point to study how opening up and closing down are related.

The role of R(R)I dimensions

In RRI, the assessment of the responsibility of innovation as well as the promotion of responsible innovation tend to build on process criteria. As explained in the introduction opening up is generally seen to require processes in which stakeholders and/or the public participate. According to Stirling (Citation2008) whether opening up takes place is not related to the type of tool (a participatory one versus a technical analysis) but to the way it is used. Both participatory approaches and technical analyses can be used alternatively to open up or close down. Hence, inclusion of actors is not necessarily a requirement for opening up.

In addition, Brand and Blok (Citation2019) state that in responsible innovation demands of participation and deliberation cannot be as high in business settings as in RRI policy or research settings because of the specific tensions in the context of commercial markets. This means that it is relevant to pay attention to other dimensions suggested in RRI-literature, such as mutual responsiveness, transparency, collective responsibility, a focus on grand challenges and flexibility or adaptability (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017; Von Schomberg Citation2014; Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; Tassone et al. Citation2018; Wickson and Carew Citation2014). In practice, we may find that other dimensions than inclusion of actors through participatory methods, are more important in innovation processes instigated by industry aiming to take responsibility for wider societal goals.

The core research question in this article is how opening up and closing down are related and induced in innovation initiatives. We approach this question by studying how issue frames of innovation initiatives change over time and how such reframing is influenced by inclusion of new actors and other dimensions of responsible innovation. In other words: we are interested in whether the efficacy paradox indeed is paramount to complex socio-technical change, and, if so, how this takes shape in real-world cases.

Research design

Two case studies

The Dutch food production system characterised by industrialisation and high export volumes, encountered severe problems of emissions to air, and surface and ground water, soil quality, concerns about animal welfare, and more recently its contribution to climate change. These and other issues have been reason for the agricultural sub-sectors to strive for sustainable innovation. Currently, there is a trend of private companies and entrepreneurs taking the lead in endeavours to align the developments in the sector with the concerns of citizens and consumers while ensuring economic viability for the sector.

Our research builds on two cases of such initiatives to contribute to societal goals in the agricultural sector. The first is the programme Sustainable Dairy Chain (in Dutch: ‘Duurzame Zuivelketen’). Dairy processing companies, represented by NZO (the Dutch Dairy Association) and the farmers’ organisation LTO Nederland, have initiated and participate in the programme ‘Sustainable Dairy Chain’. The second initiative is Market-Driven Greenhouse Sector (in Dutch: ‘STAP, STichting versterking Afzetpositie Producenten van glasgroenten in Nederland), initiated and supported by greenhouse growers. Both cases involve a coalition of companies and entrepreneurs, suggesting a minimum of inclusion of actors. However, they differ in composition and strategy. The Sustainable Dairy Chain is composed mainly of representative bodies and has organised inclusion in the form of an advisory body. The Market-Driven Greenhouse Sector initiative consists of individual growers, that is, small and medium-sized enterprises. In that regard, the two cases are both representative of responsible innovation by entrepreneurs, but also offer diversity with regard to opening up.

Analytical framework

Opening up in responsible innovation literature is primarily associated with the process, that is, the inclusion of actors and issues that challenge entrenched assumptions and commitments. The quality of a dialogue in terms of intensity, diversity and quality for instance is used as an indicator of opening up. In line with scholars downplaying the relevance and suitability of inclusion of actors, we analyse opening up as an (intermediate) outcome in an innovation process (Brand and Blok Citation2019; Pellé Citation2016). Ely, Van Zwanenberg, and Stirling (Citation2014) suggest that with opening up the results would be (1) more rigorously analysed (presenting feasible options under conditions for instance), and (2) democratically more legitimate, meaning that issues that otherwise would have been marginalised, are integrated in the framing of problem and solution. In line with this perspective, we analyse opening up as issue reframing (see 2.2) that is, if novel perspectives have become integrated. Hence, we analyse the frames of the initiatives and how they change over time. Whether this selection process to make a (re)framed issue salient is a matter of opening up or closing down, will be judged in light of the framing in an earlier phase of the initiative. Additionally, we explore the role of the efficacy paradox. See Box 1 for the operationalisation of the concepts used to investigate the (intermediate) outcomes.

Reframed issue: A fundamental change of the issue frame of the initiative: what is the perspective on the issue, what aspects are in- or excluded regarding problem definitions, issues, directions of solutions and (potential) partners and affected actors.

Opening up/ closing down: Increase or decrease of the diversity of perspectives in the reframed issue, broadening and more variety of integrated aspects, like ethical or social arguments.

Inclusion: Inclusion in the governance of the innovation process by involving new actors in deliberations regarding the prospective innovation. Inclusion means involving actors in the innovation initiative that were not involved earlier. In that sense, we do not define new actors in general as in RRI; the public and stakeholders that are usually not involved in technology development. We are also not very strict regarding the methods of involvement. In this research this is an empirical issue, ranging from full collaboration, to dialogues, to indirect input. The opposite is exclusion, meaning that actors formerly involved in the process are left out by the initiators.

Anticipation: Exploration and acknowledgement of potential consequences of the (endeavoured) strategy/ approach/ solution of the initiative.

Responsiveness: Responding to significant events outside the initiative or unexpected results of the initiative’s own actions.

Efficacy paradox: The requirement to simultaneously maintain openness and close down to retain the ability to act. Opening up risks losing an action perspective, while the risk of closing down is to be blind towards relevant considerations, ambiguity and controversies.

The anticipation-inclusion-reflexivity-responsiveness (AIRR) model (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), which defines four distinctive key features of RI, serves as an analytical framework for the supposed relations between responsibility features of the innovation process and the opening up and closing down of issue framing. We excluded reflexivity, because this concept is also better regarded as an outcome and is conflated with the activity of reflecting on assumptions and values (Beers and van Mierlo Citation2017). Moreover, while we could have replaced it with reflection, data for analysing such intimate activity were not available. Box 1 presents our operationalisation of the three applied RRI process dimensions: inclusion, anticipation and responsiveness.

Data collection

An important source of knowledge about the initiatives’ frames is provided in the ‘naturalistic setting’ of the communication in and around the initiatives, like in regular project team meetings, public presentations, informal bilateral communication and via press releases. In order to study whether and how actor inclusion, anticipation and responsiveness led to opening up of issue framings and when and why closing down takes place, we monitored the developments with regard to this topic in the two cases. We collected data through participant observation of the meetings of boards and other groups and interviewed key actors. We also collected all press releases and reports related to the cases.

Regarding the Sustainable Dairy Chain, nine participants of the steering committee and liaison committee were interviewed and over half a dozen meetings with the project coordinator attended in the period of September 2012 until February 2015. In addition, the third author of this paper attended five steering committee meetings, four liaison committee meetings, two project seminars and one public seminar. The liaison committee meetings and interviews were audio recorded and extensive written notes were made of the other meetings. Additional documentation consisted of among others press releases and over a hundred documents for the agenda.

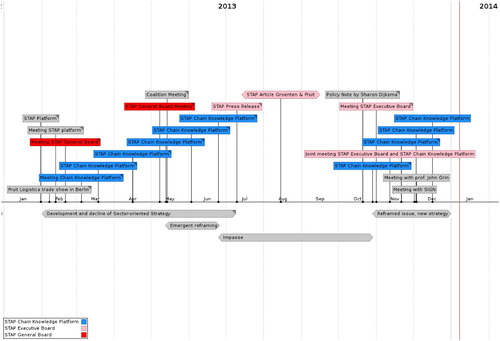

In STAP, the second author attended meetings of the general and executive boards and of the chain knowledge platform in the period December 2012–December 2013, see . Furthermore, he had several direct email exchanges with the two most active members of the executive board. We made use of complete transcripts of three meetings, extensive notes on six meetings and the minutes of nine meetings in total, including the attended meetings. We also collected documents written in the name of the initiative (including some of our own). Finally, we had access to the documents that were distributed in preparation for the meetings.

Analysis

The data analysis consisted of the following steps:

-

Defining the changes in the initiatives’ framing of the issue compared to earlier framings. This concerns the framing in the name of the initiative. This resulted in a sequential analysis of the initiatives general issue frames present in their communication in order to investigate changes over time. The case descriptions are structured by phases of (re)framing.

-

Assessing whether the issue reframing can be seen as an opening up or a closing down.

-

Exploring how the contents of reframing are related to the inclusion or exclusion of actors in the period preceding the reframing, and if possible analysing whether there is an obvious connection with new issues brought in by actors. Also defining the type of engagement of these actors.

-

Exploring the relation with the other RI dimensions, anticipation and responsiveness.

-

Exploring how the efficacy paradox seems to have played a role in the phase preceding the reframing.

Sustainable dairy chain

Baseline: collaborative initiative to address sustainability issues (2008–2010)

In 2008, the Sustainable Dairy Chain (SDC) initiative was established by the Dutch Dairy Association (henceforth: NZO), which represents the dairy processing companies that process 98% of Dutch milk and the Dutch Federation of Agriculture and Horticulture (henceforth: LTO) which represents 70% of Dutch dairy farmers. SDC wanted to act proactively, because societal resistance was expected to arise in the future due to further intensification of the sector. Establishing the SDC was itself a first reaction to the increasing amount of cows housed per farm and the milk production per cow. The intensification was feared to be strengthened by the EU decision in 2005 to abolish the milk quota system in 2015. The cap on the maximum amount of milk produced per country kept the rate of intensification of dairy farms relatively low in comparison with other Dutch husbandry sub-sectors (e.g. pigs and poultry). Policy, business and research expected that the end of the milk quota system would increase the Dutch stock of cattle and thus increase the amount of manure and greenhouse gases (Reijs et al. Citation2013). Several NGOs, political parties, government, dairy farmers and advisors had signalled to individual dairy processing companies of NZO, and LTO, that actions had to be taken to counteract these undesirable developments. This instigated NZO and LTO to set up and collaborate in the initiative. For an account of how the innovating incumbents of SDC question which actions contribute to a sector transformation, see [self-citation, excluded for anonymity].

In the first phase, SDC framed the main issue as follows:

Dairy farmers, processing companies, NZO and LTO have been active on sustainable production for many years. However, we can do better. Sustainability requires commitment from all parties. That’s why the dairy farmers and the dairy sector joined forces in July 2008 to make it more sustainable together through the Sustainable Dairy Chain initiative. (Sustainable Dairy Chain Citation2010, 2)

Reframing: setting goals to enable action (2011–2012)

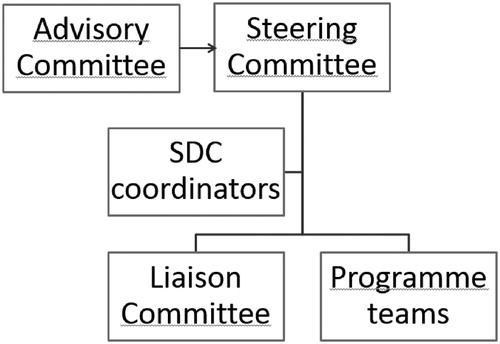

In 2010, the coordinator who had newly become involved in the project, argued that a programme organisation had to be installed and collective goals were needed to set things in motion. shows the resulting organisational structure of SDC:

-

The steering committee, which primarily discusses political and strategic matters, consists of representatives of both the dairy companies (i.e. NZO) and the dairy farmers (i.e. LTO).

-

An advisory committee consisting of representatives of the government, business, civil-society organisations and the scientific community, which is to meet biannually to provide feedback to the steering committee.

-

The liaison committee, consisting of the processing companies’ sustainability managers, responsible for the development and implementation of each dairy factory’s sustainability programme.

It took until the summer of 2011 before SDC had decided on specific goals, because the priorities of the dairy processing companies had to be aligned with one another, their constituencies and with LTO’s priorities (Sustainable Dairy Chain Citation2012). The goals, to be realised by 2020, now focussed on climate & energy, animal health & animal welfare, grazing and biodiversity & the environment. Comparing these goals with the three themes from SDC’s first annual report shows that a reframing in the form of an opening up had occurred with regard to the issue of grazing. In the first annual report, grazing was only mentioned as an aspect of animal welfare. The reframing did not visibly lead to a closing down towards other aspects; the earlier goals all remained part of the issue framing.

After the goals had been set in 2011, the initiative succeeded in stopping the decline of the percentage of cows grazing among others by financially rewarding farmers (Doornewaard et al. Citation2018). They received a reward from the dairy processing companies if the farmers applied grazing (Sustainable Dairy Chain Citation2015). So why and how did grazing appear so prominently on the agenda? It was well known by the project managers that grazing of cows is much appreciated in the Netherlands. Dutch citizens have a positive view of dairy farms, if they are family businesses with not too many cows (Onwezen et al. Citation2013). Especially the grazing of cows in meadows (from spring until autumn) has a high cultural status in the Netherlands. For example, each year the national news stations broadcast videos of skipping cows on the first day of grazing after a winter of staying indoors. Several NGOs value grazing as it is associated with the natural behaviour of cows (Driessen Citation2014). Moreover, according to them, dairy farms with grazing cows can, to some degree, close the local nutrient loop if the manure of the cows is applied as natural fertiliser on grassland. And grass absorbs the nutrients of the manure better than crop fields like corn, hence reducing the leaking of nutrients into groundwater and surface water.

The case data suggest that in this context, the opening up to grazing was triggered by concerns of SDC with the ongoing trend of decline in grazing based on studies showing a decline of grazing. In the Netherland in 2001 90% of the dairy cows grazed, in 2007 this dropped to 80% and in 2012 to 70% (Van Den Pol-Van Dasselaar et al. Citation2015). On the basis of knowledge about the public’s appreciation of grazing and the declining trend, SDC expected that a further drop in grazing would harm the dairy sector’s license to produce. The opening up towards grazing by SDC can be perceived as anticipation to an even further decline of grazing as the consequence of not intervening. It was not the result of actor inclusion, because no new actors had been consulted or provided input otherwise.

Reframing: introducing a vision and adapting the goals (2013 onward)

In 2013, SDC reframed its issue for the second time when developing a vision of Dutch dairy farming and adjusting its goals. NZO and LTO jointly presented a future vision of family farms with grazing land for responsible development of the Dutch dairy sector. The vision incorporated several new concrete measures like the introduction of a tool to improve nutrient management, and, as a consequence, manure management. Every year independent manure monitoring and reporting would take place. The sector would thus apply an ‘early warning’ system to monitor the phosphate ceiling. The sector also planned to take measures in case the dairy sector would exceed the nitrogen and phosphate limits. Suggested measures involved reducing animal feed phosphate levels, more extensive application of the Annual nutrient cycle assessment (KringloopWijzer) as a dairy farm management tool and, if possible, implementing maximum phosphate levels per farmer (instead of animal quota; NZO and LTO Citation2013)Footnote 1 (opening-up).

Another novel issue addressed in this new phase of the SDC concerned the so-called ‘unwanted business types’; for intensive farms with closed barns and without grazing and feed from the nearby environment there was no place in the vision of NZO and LTO (opening-up). In line with this vision, some individual dairy companies decided not to buy or process milk from new farms that did not comply with the desired vision of the future. In addition, SDC requested local governments to apply similar norms when granting permits to new and expanding dairy farms.

The adapted goals of the SDC were made public at the end of 2014 (Sustainable Dairy Chain Citation2014). The issue reframing consisted of integrating long-term goals regarding values of the dairy farmers such as work pleasure and profits (opening up), while the earlier goals focused predominantly on environmental and animal issues. Among the adapted goals was the statement:

Through the Sustainable Dairy Chain, dairy organizations (NZO) and dairy farmers (LTO) work together towards a dairy sector that is future proof and responsible, that is, a sector in which work is fulfilling and safe; where one can earn a good living; that produces high-quality food; that respects animals and the environment; a sector that is appreciated. (Sustainable Dairy Chain Citation2014)

In practice however, some issues received less attention in 2013 among others due to the high priority and action undertaken on the manure issue. This presents a clear case of the efficacy paradox. Closing down took place regarding the issues of sustainable energy production and biodiversity. The goal of 30% reduction of greenhouse gasses changed to 20% reduction. The earlier goal no longer seemed realistic, due to the changes regarding subsidies for reducing CO2-emissions and hence lost some of its political momentum. The goal regarding biodiversity was downsized from ‘improving biodiversity’ to ‘no net loss of biodiversity’ because the issue was hard to operationalise.Footnote 2

The opening up towards manure happened in response to the Minister for Agriculture who asked the dairy sector to develop and implement a plan to ensure that growth of the dairy sector would not result in too much manure production thereby exceeding the European limit of phosphate and nitrogen production in January 2013. She warned that if the sector would fail to keep manure production below the annual cap of 504 million kilograms of nitrogen and 173 million kilograms of phosphate, the government would have to intervene and the dairy sector would face restrictions on the total amount of animals allowed (Ministry of Economic Affairs Citation2013). On April 23, this message was publicly repeated at a SDC symposium. Here the Minister of Agriculture gave a speech in which she praised the dairy sector for its sustainability efforts and results while raising attention for the manure surplus agreements that she had made with the dairy sector before:

You (authors: the dairy sector) came to me and proposed: let us realise manure management – and drop those other complicated legislations so that we can solve the issue ourselves. So I did just that, like you wanted me to. I do add one thing: you need to keep your promise. (transcript)

The dairy sector had already been working on a manure plan but in response to the revived attention to manure and other issues, the steering committee assigned a working group to draft a discussion note for NZO and LTO with suggestions for a future vision for Dutch dairy farming and goal adjustments if necessary. As a result, at the end of 2013, the Ministry decided to exempt the dairy sector from animal quota, in contrast with other Dutch animal sectors (Dijksma Citation2013). This meant that dairy farms were allowed a limited degree of expansion, provided they kept within nitrogen and phosphate limits, had sufficient land to use the manure, or were able to process manure surpluses. Thus, the SDC responded to the ministry’s request and opened-up to manure issues and developed a manure plan.

With the reformulation of goals and formulation of a vision, SDC also reacted to its advisory committee, of which some members expressed worries about the growth of dairy farms during a meeting in 2013. The representatives of a consultancy and the Animal Protection Agency expressed a similar risk of increasingly ‘closed’ dairy farms (that is, among others, no grazing). They emphasised that this could result in public resistance against the dairy sector, similar to what had happened to the intensive livestock farming sectors of poultry and pigs in the Netherlands. This issue was not only voiced by members of the advisory committee. Interviews revealed that NGOs, farmers, retailers and other stakeholders issues also shared issues with members of the SDC informally. Also at the symposium, politicians, NGO representatives, and dairy sector organisations were given the floor to express their ideas and ask questions to SDC members. The reframing of the issue hence took place after both internal (such as the advisory committee) and external (such as dairy advisors and NGOs) communication. Hence, while we cannot fully judge which actors that provided input were new, it seems that the inclusion of new actors also contributed to the issue reframing.

Conclusion

Over the years of its existence, the framing in the SDC changed from a more general notion of a future-proof and responsible sector with environmental and animal welfare themes to concrete sustainability goals that gave more priority to maintaining grazing (opening up). This first reframing assisted in overcoming the initial efficacy paradox: the concrete goals were followed by collaborative action, predominantly in the form of activities, instruments and agreements related to several goals. The second reframing was the result of the invitation of the Minister of Agriculture to develop a manure plan to avoid an animal quota system (responsiveness) as well as the inclusion of concerned actors. In addition to the goals adjustment in the form of more specific manure goals (opening-up) SDC opened-up to dairy farmers’ issues such as a viable income, work safety and work pleasure. The reframed goals were less ambitious with regard to green gases and biodiversity (closing down).

STAP; a sustainability initiative in the greenhouse sector

Baseline: a more competitive position for greenhouse growers

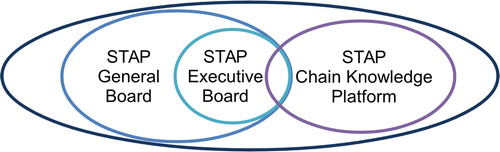

STAP, or in full, the Foundation for Strengthening the Sales and Marketing Position of Greenhouse Vegetable Producers, can be seen as an innovation network of various greenhouse growers, researchers, educational institutes and intermediaries (see ). At the beginning of our data collection (January 2013), STAP consisted of an executive board with three members and a larger general board, both consisting mainly of greenhouse growers. Some board members were also active as salespersons and traders. Meetings of the general board were also attended by representatives of the Dutch Federation of Agriculture and Horticulture. For both STAP boards, the main issue was the bad market position of greenhouse growers resulting from their preoccupation with trying to decrease production costs, their lack of market orientation and the low financial margins. STAP Exec: ‘The central issue: a more competitive position for greenhouse growers’ (2013-02-12). STAP’s position can therefore be seen as a reaction to the dominant production-oriented innovation strategy.

STAP was founded by greenhouse growers a few months after the so-called EHEC crisis in March 2011. An EnteroHemorrhagic Escherichia Coli (EHEC) contamination in vegetables had caused Haemolytic-Uremic Syndrome (HUS) in consumers, causing 53 people to die (mostly in Germany; EFSA Citation2012). Although Dutch produce was not infected with EHEC, the crisis strongly affected growers’ market positions when consumers turned away from tomatoes and cucumbers. For the STAP initiators, this momentum provided an opportunity to put their concerns about the greenhouse sector’s market position due to their lack of power as well as their lack of a market orientation on the public agenda. STAP’s initial goal was to improve the sector’s market innovation through market-oriented innovation. To that end, it stimulated more collaboration among growers in order to provide them with more power to stand up to the supermarkets. The initiators called this ‘horizontal bundling’. For an account of the social learning process and outcomes in this network, see [self-citation, excluded for anonymity].

During our study, we witnessed reframing of the innovation orientation and the kind of collaboration that would be needed. Below, we describe these reframings in detail.

Reframing: vertical bundling

Early 2013, STAP executive board members reflected on their efforts and results of the preceding one-and-a-half years (sources: board meeting data, CKP meeting data, informal conversations with board members). Both STAP boards concluded that they needed other, more effective strategies than horizontal bundling. The executive board concluded that it could not achieve such change on its own, because growers needed market knowledge from sales and trade parties to increase their consumer awareness. STAP realised it had to collaborate with other parties in the sector. Thus, a reframing of STAP’s strategy took place, from horizontal bundling to vertical bundling (collaboration between chain partners; opening up).

The data suggest that several experiences with responses to horizontal bundling led to the conclusion that the strategy of horizontal bundling did not yield results. This suggests that the reframing was the result of responsiveness:

-

Farmers did not want to participate in an initiative for horizontal bundling in sweet peppers.

-

50 STAP workshops with greenhouse growers did not convince the participants of the need to become more market oriented. Instead, growers continued to focus on cost-price reduction. As a CKP member said: ‘The first thing they do is develop a new package for their product’.

A step towards vertical bundling was to establish a platform of education and research institutes to provide knowledge in answer to questions of entrepreneurs and in this way stimulate the latter to innovate: the chain knowledge platform (henceforth: CKP). This platform was expected to have a catalysing effect on the innovative capacity of the sector as a whole. An Executive Board member met with several prospective partners of the knowledge platform. After these meetings, Inholland, a higher agricultural education institute, the Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Syntens, an institute that facilitates innovation, and Wageningen University (i.e. one of the authors of this article) decided to join the CKP. This inclusion of new actors hence seems to be the result of the reframing rather than a cause.

Additionally, STAP sought collaboration with traders and sales organisations and planned to form a coalition with the associations of the trade organisations (FrugiVenta) and sales organisations (DPA); the two main value chain organisations (inclusion). The CKP meeting data suggest however that STAP was ambivalent regarding these two organisations. On the one hand, they were seen as old-fashioned, as part of the problem and as opposing a better position for growers, suggesting that STAP was including incumbent voices rather than more innovative ones. On the other hand, the same persons also framed them as a necessary partner for a broad movement in the greenhouse sector. Moreover, since these organisations faced roughly the same challenges as the greenhouse growers, they were expected to take on a more innovative attitude; STAP Executive: ‘Even the biggest trader is starting to wonder about his future position, because everybody knows things are changing. I’m not worried about that’ (2013-02-20).

In bilateral meetings with STAP executives, the director of FrugiVenta indicated that they would join the coalition. STAP expected DPA to do so later. In addition, the chairperson of Greenport Holland International, an organisation that aimed to export Dutch knowledge and technology from the greenhouse sector, supported collaboration of STAP, DPA and FrugiVenta. Frugiventa’s position however, flip-flopped several times. This development also made the future and role of the CKP uncertain; why establish the CKP if it has no role to align co-operation among value chain actors?

STAP attempted to reach a breakthrough by issuing a position statement: ‘Lobbying is organised horizontally, by product chain links, whereas growers, consumers/citizens and the government increasingly want vertical and regional lobbying’ (STAP Board Citation2013). In response, at a follow-up meeting, Frugiventa and DPA and several other stakeholders in the sector stated that they supported STAP’s position statement. This implies that they supported the Chain Knowledge Platform and STAP’s vision to make the sector more consumer-oriented through innovation. Soon after, however, FrugiVenta withdrew their support, effectively ending the collaboration between DPA, FrugiVenta and STAP. This attempt at collaboration clearly had various stifling effects on the activities of STAP – what to do with the CKP? How to effect the new strategy for vertical bundling? In that sense, the failing attempts at including value chain actors exemplifies the efficacy paradox.

Reframing: experimentation with frontrunners

During a CKP meeting one month earlier (April 16), a discussion led to a second reframing. STAP’s key issue became framed as a necessary change towards a broad and societal orientation, with a long-term perspective, as opposed to the more consumer-oriented short-term market perspective of STAP’s general board. The associated innovation strategy was broadly framed as follows: the current situation requires radically new products, which the majority of growers cannot create on their own and hence calls for the creation and exchange of successful examples of innovation with a few frontrunners. A STAP executive of the CKP said (May 13, 2013): ‘Growers should think in much broader terms. They used to think that they were sustainable when they had a [gas-powered] combined-heat and power-installation’. Societal themes such as public health, food security, food waste and climate change were integrated in this reframed issue (opening up).

CKP members shared several observations regarding the earlier actions of STAP, about how most famers had great difficulty in making the leap to a market orientation, let alone a societal one (responsiveness): ‘Nine out of ten will not be able to take that step’; and: ‘The traders should come along, but the executives are stuck thinking about cost efficiency’. In response, the CKP decided to discuss its role and uncertain position in the initiative and reflected on how the CKP might best serve STAP and the greenhouse sector in general. This discussion was also triggered by a television programme featuring a transition management scholar earlier that week, which several CKP members had watched. The group spent a long time discussing sector issues in light of ‘transitions’.

The next CKP meeting took place on June 3. While not yet official, it had already transpired that DPA and FrugiVenta would withdraw their support for STAP and the CKP. This can be seen as exclusion of actors (albeit of their own choice). In response, in a press release July 10, 2013, STAP announced to be ‘less active’ temporarily, blaming Frugiventa and DPA of a lack of willingness to cooperate and sense of urgency (Stichting STAP Citation2013). The press release also stated that in addition to growers, the trade organisations would be affected negatively if growers and traders failed to collaborate more closely. A three-month period of inaction ensued.

Notwithstanding the announcement to become more passive, developments accelerated with the release of the Horticulture letter of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs on 20 October 2013. It announced the start of a horticulture chain innovation programme of one million euros. The minister wanted this programme to support entrepreneurs to address challenges regarding sustainability, safe and healthy foods, and a healthy environment. This programme offered a window of opportunity for the reframed issue of STAP (responsiveness). Thus, when at the CKP meeting of October 28 the main question was whether the CKP should continue at all, and if so, how, the meeting reached a positive conclusion about continuation. Societal issues were confirmed to be squarely on the CKP agenda. The members developed a plan including a short-term strategy of developing new business models for sustainability and society, experimentation aimed at consumers, and a long-term strategy aimed at society as a whole. In this way, the CKP confirmed the broader issue framing and strategy for STAP. The STAP executive board discussed the plan and, concluding that it was interesting, decided to discuss it further in a joint meeting with the CKP. At this point, at the end of 2013, societal issues were an integral part of the STAP initiative. The government funds directed at chain innovation created space for action notwithstanding the exclusion of value chain actors.

While the new issue framing can be seen as an opening up, the reframing occurred without the inclusion of associated actors. Again, responsiveness seems to have been more influential. The developments suggest that opening up of the issue frame did not go hand in hand with less action perspective, and instead created space for action in this specific case (efficacy paradox)

Conclusion

The case history shows two phases of issue reframing of the main challenges facing the greenhouse sector. The first reframing concerned a value chain-wide strategy to address growers’ bad market positions instead of horizontal bundling. This reframing came about through responsiveness regarding STAP’s initial strategy: fostering horizontal collaboration between producers had largely failed to make greenhouse growers more market-oriented. The concrete actions had consisted only of workshops with farmers. The reframing led to the inclusion of trade organisations and sales organisations. This reframing was both a closing down (of horizontal bundling) and opening up (of vertical bundling)

The second issue reframing started in the CKP. The new issue frame incorporated more societal issues than the former one (opening up). While earlier the growers were said to be turning their backs on the market, they were now said to turn their backs on society. As a consequence of this new problem definition, ‘societal’ issues became central in the framing.

It is interesting to see how societal issues slowly came to the fore, although citizens and NGOs were not directly involved in STAP. Rather, the combination of transition thinking, introduced mainly by a television programme, the CKP member from Syntens and one of the authors of this article, and the original assumption within the CKP that the greenhouse sector lacks innovation capacity, gave way to the consideration of a long-term strategy including societal issues. This latter opening up happened without inclusion of actors, and without the efficacy paradox occurring. Quite the contrary, it co-occurred with the exclusion of the chain partners. When some months later similar issues were mentioned in the policy letter, this offered a way out of STAP’s impasse.

Discussion

In this discussion, we reflect on our findings in the context of responsible innovation and discuss their implications for this emerging field. The emphasis in responsible innovation literature on opening up seems to coincide with disregard of its companying partner; closing down. In line with the basic assumption in framing theory, our findings confirm that opening up and closing down should not be regarded as separate phases in a process of innovation. The focus on issue reframing was helpful to discern opening up from closing down in the very same phase. They took place hand in hand in several occasions of reframing when decisions were taken about future directions and concrete measures and actions of the initiatives. This means that innovation is not a single process in which opening up proceeds or needs to proceed closing down as is proposed by e.g. Roberts and Geels (Citation2019). It also means that there is no need to discern specific hybrid forms of opening and closing down as identified by Voβ, Bauknecht, and Kemp (Citation2006). Instead, opening up and closing down alternate regularly and coincide over time. It hence seems that opening up as the sole ultimate goal of responsible innovation does not necessarily provide a useful normative guideline. It could be replaced with the suggestions of striking a balance between opening up and closing down as suggested by Voβ, Bauknecht, and Kemp (Citation2006).

The two cases show that inclusion of new actors can have many forms: discussing options for collaborative action, advising, organising a symposium and informal communication with all kinds of relevant actors as well as negotiation processes behind the scenes. This reflects the suggestion of De Hoop, Pols, and Romijn (Citation2016) to investigate how people become involved in and modify an innovation process. We found that the inclusion of new actors is not the panacea for opening up the innovation process in initiatives of private partners. First of all, inclusion may also follow upon opening up instead of the other way around, as we saw in the first reframing in the STAP case. In this case, we even observed the opposite, when in the second reframing inclusion had a paralysing effect (see also De Hoop, Pols, and Romijn Citation2016). This raises the question of how the efficacy paradox should be understood: is it indeed a feature of opening up or a dilemma related to inclusion of new actors?

Secondly, not inclusion, but responsiveness to external developments such as changing governmental priorities seemed to be the key trigger for opening up in both industry-led cases. Opening up hence clearly is not necessarily the result of including new voices in dialogues and deliberations. This is in line with long-standing criticisms to the high expectations of formally organised public dialogues in many different (national) contexts (Wynne Citation2007; Jamison and Wynne Citation1998; Cooke and Kothari Citation2001).

In the current literature on responsible innovation, a major argument for inclusion of actors is to acknowledge distributed knowledge and resources and open up towards diverse and possibly contrasting values. The notion that inclusiveness is needed for collaborative action, as is the case in the two initiatives studied, is hardly recognised. The literature on system innovation and sustainability transitions stresses that, for new technologies and other innovations to be put into practice, new rules and relations, that is, new systemic properties need to be developed by a diversity of actors (Schot and Geels Citation2008). Applying such notions to the contested emerging technologies which are at the core of responsible innovation literature sheds new light on the resistance against and contestation of emerging technologies. They may be fed by uncertainties and the risk of negative unanticipated effects, but also by the new technologies’ path-breaking character vis-à-vis incumbent systemic properties (Arkesteijn, van Mierlo, and Leeuwis Citation2015). Given that responsible innovation aims to help tackle societal issues or the ‘grand challenges’ (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012), its further conceptualisation may well benefit from the sustainability transitions literature. Scrutiny of the rules and assumptions in which normal practices are embedded could be promising, as well as adopting principles of reflexive governance.

The findings raise the question of how to regard closing down and deal with its potential negative effects, if not by public dialogue. Obviously, the decisions taken in the initiatives studied may not have the far-reaching implications of path-dependency compared to the choices about new emerging technologies discussed in the responsible innovation literature. However, the cases confirm that the governance of a transformative change process requires finding a balance between opening up and closing down to deal with the efficacy paradox of complexity (Grin and Weterings Citation2005). An initiative that aims to contribute to substantive change in a sector needs to address opening up as well as closing down and set priorities. Although responsible and desirable, a continuous situation of deliberation that allows contestation would hardly result in change.

We propose to regard opening up and closing down neither as the characteristics of specific types of participatory tools for including new voices, nor just as a feature of the innovation process (Stirling Citation2008). Instead, we have analysed opening up and closing down as intermediate outcomes of an innovation process in the form of issue reframing. Rather than by merely stimulating the direct inclusion of actors to contest the decisions taken and choices made, responsible innovation may be served by stimulating innovation initiators to be more responsive and anticipative. In addition, it seems useful if they reflect on the issue reframing in the decision making process to see in what respects it entails an opening up and in what others a closing down, and more specifically on the ethics in the arguments and values when setting priorities and making choices between issues and options for action.

Conclusion

The main aim of responsible (research and) innovation is to open up research, innovation and development processes to issues that contest dominant assumptions, values and interests. Following criticisms regarding the effectivity of participatory tools in opening up an innovation process, we set out to investigate the importance of opening up in relation to closing down and the role of actor inclusion in two cases of companies initiating value chain-wide change in order to take societal responsibility. The results suggest that the inclusion of actors is not the panacea for opening up the innovation processes. In the industry-led cases responsiveness was more relevant for opening up; an RRI-dimension that has hitherto received little attention.

Opening up and closing down are identified as intermediate outcomes of an innovation process in the form of reframing of the initiative’s core issue. They can occur simultaneously and are inherent parts of an innovation process. Normative frameworks regarding a particular desirable order hence seem of little use for concrete innovation initiatives. Hence, in addition to the advocated ‘opening up’, the question of how to balance it with closing down in order to arrive at collaborative action deserves full attention.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), as part of the programme Responsible Innovation (MVI) under Grant 313-99-016. We are thankful for the fruitful exchange with the innovators in the Sustainable Dairy Chain and STAP, in particular Peter Duijvestijn, Peter van der Sar and Petra Tielemans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Barbara van Mierlo is associate professor, studying processes of transformative, systemic change towards sustainability and their intersection with everyday social practices. Being actively engaged in these processes, special interests include the significance and features of interactive learning and discursive strategies, the value of change-oriented evaluation, emergence of reflexivity, responsible innovation, and transdisciplinary collaboration.

PJ Beers is senior researcher at DRIFT (Erasmus University Rotterdam) and professor of applied science at HAS University of Applied Science (Den Bosch, The Netherlands). He studies and facilitates initiatives towards transition primarily in the fields of agriculture and education with a specific interest in learning and monitoring. His recent work concerns the development of new, transition-oriented business models for agriculture.

Anne-Charlotte Hoes is an action-researcher at Wageningen Economic Research. Her expertise in (system) innovation, stakeholder engagement, reflexive monitoring and communication enables Anne-Charlotte to assist multi-actor initiatives to improve their strategy and realise transformative change.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In 2015 the Dutch government stated that it would indeed introduce phosphate rights as a way to limit the growth of the Dutch dairy sector.

2 During the writing of this article, greenhouses gases and biodiversity are again high on the political, and agricultural policy agenda.

References

- Arkesteijn, Marlèn , Barbara van Mierlo , and Cees Leeuwis . 2015. “The Need for Reflexive Evaluation Approaches in Development Cooperation.” Evaluation 21 (1): 99–115.

- Beers, Pieter J. , and Barbara van Mierlo . 2017. “Reflexivity and Learning in System Innovation Processes.” Sociologia Ruralis 57 (3): 415–436.

- Blok, Vincent , and Pieter Lemmens . 2015. “The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation. Three Reasons Why it is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation.” Responsible Innovation 2: 19–35. Springer.

- Bouwman, Laura I , Hedwig Te Molder , Maria M Koelen , and Cees MJ Van Woerkum . 2009. “I Eat Healthfully but I am Not a Freak. Consumers’ Everyday Life Perspective on Healthful Eating.” Appetite 53 (3): 390–398.

- Brand, Teunis , and Vincent Blok . 2019. “Responsible Innovation in Business: A Critical Reflection on Deliberative Engagement as a Central Governance Mechanism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (1): 4–24.

- Burget, Mirjam , Emanuele Bardone , and Margus Pedaste . 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19.

- Cooke, Bill , and Uma Kothari . 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London : Zed Books.

- De Hoop, Evelien , Auke Pols , and Henny Romijn . 2016. “Limits to Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 110–134.

- Dewulf, A. , and R. Bouwen . 2012. “Issue Framing in Conversations for Change: Discursive Interaction Strategies for ‘Doing Differences’.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 48 (2): 168–193. doi:10.1177/0021886312438858.

- Dewulf, A. , B. Gray , L. Putnam , R. Lewicki , N. Aarts , R. Bouwen , and C. van Woerkum . 2009. “Disentangling Approaches to Framing in Conflict and Negotiation Research: A Meta-Paradigmatic Perspective.” Human Relations 62 (2): 155–193. doi:10.1177/0018726708100356.

- Dijksma, S. A. M. 2013. Letter from Secretary of State of Economic Affairs. Kamerstukken II 2013/14, 33 037, nr. 80, https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-33037-80.html .

- Doornewaard, G.J. , J.W. Reijs , A.C.G. Beldman , J.H. Jager and M.W. Hoogeveen . 2018. Sectorrapportage Duurzame Zuivelketen; Prestaties 2017 in perspectief [ Sector Report Sustainable Dairy Chain, Preformance 2017 in Perspective]. Wageningen : Wageningen Economic Research Report 2018-094. https://edepot.wur.nl/466401

- Driessen, C. 2014. “Animal Deliberation: The Co-Evolution of Technology and Ethics on the Farm.” PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) . 11 July 2012. “E. coli: Rapid Response in a Crisis”. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20181224083524/https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/120711 .

- Ely, Adrian , Patrick Van Zwanenberg , and Andrew Stirling . 2014. “Broadening Out and Opening Up Technology Assessment: Approaches to Enhance International Development, Co-Ordination and Democratisation.” Research Policy 43 (3): 505–518.

- Gray, B. 2003. “Framing of Environmental Disputes.” In Making Sense of Intractable Environmental Conflicts. Frames and Cases , edited by R. J. Lewicki , B. Gray , and M. Elliott , 11–34. Washington/Covelo/London : Islands press.

- Grin, John , and Rob Weterings . 2005. “Reflexive Monitoring of System Innovative Projects. Strategic Nature and Relevant Competences.” 6th Open Meeting of the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change Research Community, University of Bonn, 9–13 October 2005.

- Irwin, A. , Jensen, T. , and Jones, K. 2013. “The Good, the Bad and the Perfect: Criticizing Engagement Practice.” Social Studies of Science 43: 118–135.

- Jamison, Andrew , and Brian Wynne . 1998. “Sustainable Development and the Problem of Public Participation.” In Technology Policy Meets the Public, edited by Andrew Jamison, 7–17. Aalborg, Denmark: Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University.

- Ministry of Economic Affairs . 2013. Voornemen verdere behandeling wijziging meststoffen [ Procedure to Change Manure Policy]. The Hague: Ministry of Economic Affairs.

- NZO and LTO . 2013. “Zuivelsector kiest voor grondgebonden melkveehouderij [Dairy Sector Choose for Land Bound Dairy Farms] Press Release.” Accessed September 3, 2015. https://www.lto.nl/actueel/nieuws/10838261%2FZuivelsector-kiest-voor-grondgebonden-melkveehouderij .

- Onwezen, M. C. , H. M. Snoek , M. J. Reinders , and J. Voordouw . 2013. De Agrofoodmonitor: maatschappelijke waardering van de Agro & Food sector . Wageningen : LEI Wageningen UR.

- Owen, R. , P. Macnaghten , and J. Stilgoe . 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs093.

- Pandza, K. , and P. Ellwood . 2013. “Strategic and Ethical Foundations for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (5): 1112–1125. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.02.007.

- Pellé, Sophie. 2016. “Process, Outcomes, Virtues: The Normative Strategies of Responsible Research and Innovation and the Challenge of Moral Pluralism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 233–254.

- Regeer, Barbara J. 2009. “Making the Invisible Visible. Analysing the Development of Strategies and Changes in Knowledge Production to Deal with Persistent Problems in Sustainable Development.” PhD Study. Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit.

- Reijs, J. W. , C. Daatselaar , J. Helming , J. Jager , and A. Beldman . 2013. Grazing Dairy Cows in North-West Europe. Economic Farm Performance and Future Developments with Emphasis on the Dutch Situation . Wageningen : LEI, Wageningen UR, LEI Report 2013-001.

- Roberts, Cameron , and Frank W. Geels . 2019. “Conditions and Intervention Strategies for the Deliberate Acceleration of Socio-Technical Transitions: Lessons from a Comparative Multi-Level Analysis of Two Historical Case Studies in Dutch and Danish Heating.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 31 (9): 1081–1103.

- Scholten, VE , and V Blok . 2015. “Foreword: Responsible Innovation in the Private Sector.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 15 (2): 101–105.

- Schot, Johan , and Frank W. Geels . 2008. “Strategic Niche Management and Sustainable Innovation Journeys: Theory, Findings, Research Agenda, and Policy.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 20 (5): 537–554.

- Stilgoe, J. , R. Owen , and P. Macnaghten . 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Stirling, A. 2008. “‘Opening Up’ and ‘Closing Down’ – Power, Participation, and Pluralism in the Social Appraisal of Technology.” Science Technology & Human Values 33 (2): 262–294. doi:10.1177/0162243907311265.

- STAP Board . 2013. “Urgentie document Versterking marktpositie glasgroente producenten [Urgency Document Strengthening Market Position Greenhouse Vegetable Producers].” STAP Foundation, Honselersdijk, The Netherlands: Stichting STAP.

- Stichting STAP . 2013. “Persbericht: Gebrek aan urgentiegevoel stokt transitie verse voedingsketen [Press Release: Lacking Sense of Urgency Stymies Transition Fresh Foods Chain].” Accessed July 11, 2013. https://www.eenheidinvers.nl/nieuws/20130711-persbericht-gebrek-aan-urgentiegevoel-stokt-transitie-verse-voedingsketen .

- Sustainable Dairy Chain . 2010. “Verder op weg naar een duurzame zuivelketen verslag 2009 [On the Road to Sustainable Dairy Chain Report 2019].” Accessed July 6, 2016. https://www.duurzamezuivelketen.nl/files/jaarverslag-2009-dzk.pdf .

- Sustainable Dairy Chain . 2012. “Duurzame vooruitgang verslag 2011 [Sustainable Progress Report 2011].” Accessed July 6, 2016. https://www.duurzamezuivelketen.nl/files/jaarverslag-2011-dzk.pdf .

- Sustainable Dairy Chain . 2014. “Herijking doelen Duurzame Zuivelketen [Goals adjusted Sustainable Dairy Chain].” Accessed September 3, 2015. https://www.duurzamezuivelketen.nl/nieuws/herijking-doelen-duurzame-zuivelketen2? p=5.

- Sustainable Dairy Chain . 2015. “Meer melkveebedrijven met koeien in de wei [More Dairy Farms with Grazing Cows].” Accessed July 8, 2016. https://www.duurzamezuivelketen.nl/nieuws/meer-melkveebedrijven-met-koeien-in-de-wei2? p=2.

- Tassone, Valentina C. , Catherine O’Mahony , Emma McKenna , Hansje J Eppink , and Arjen EJ Wals . 2018. “(Re-)designing Higher Education Curricula in Times of Systemic Dysfunction: A Responsible Research and Innovation Perspective.” Higher Education 76 (2): 337–352.

- Van Den Pol-Van Dasselaar, A. , P. W. Blokland , T. J. A. Gies , G. Holshof , M. H. A. De Haan , H. S. D. Naeff , and A. P. Philipsen . 2015. Beweidbare oppervlakte en weidegang op melkveebedrijven in Nederland [Grazing grounds and grazing on dairy farms in the Netherlands]. Wageningen : Wageningen Livestock Research Report 917. https://edepot.wur.nl/362949.

- Van Huijstee, Mariette , and Pieter Glasbergen . 2010. “Business–NGO Interactions in a Multi-Stakeholder Context.” Business and Society Review 115 (3): 249–284.

- Van Lieshout, M. , A. Dewulf , N. Aarts , and C. Termeer . 2013. “Framing Scale Increase in Dutch Agricultural Policy 1950–2012.” Njas-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 64–65: 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2013.02.001.

- Van Mierlo, Barbara , Arni Janssen , Ferry Leenstra , and Ellen van Weeghel . 2012. “Encouraging System Learning in Two Poultry Subsectors.” Agricultural Systems 115: 29–40.

- Van Tatenhove, Jan P. M. , and Henri J. M. Goverde . 2002. “Strategies in Environmental Policy. A Historical Institutional Perspective.” In Greening Society. The Paradigm Shift in Dutch Environmental Politics , edited by P. J. Driessen and Pieter Glasbergen , 47–63. Dordrecht : Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Veen, M. , B. Gremmen , H. T. Molder , and C. van Woerkum . 2011. “Emergent Technologies Against the Background of Everyday Life: Discursive Psychology as a Technology Assessment Tool.” Public Understanding of Science 20 (6): 810–825. doi:10.1177/0963662510364202.

- Von Schomberg, René . 2014. “The Quest for the ‘Right’ Impacts of Science and Technology: A Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation 1. Innovative Solutions for Global Issues , edited by J. van den Hoven , N. Doorn , T. Swierstra , B. J. Koops , and H. Romijn , 33–50. Dordrecht, NL : Springer.

- Voβ, Jan-Peter , Dierk Bauknecht , and René Kemp , eds. 2006. Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development . Cheltenham, UK / Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Walker, G. , and Shove, E. 2007. “Ambivalence, Sustainability and the Governance of Socio-technical Transitions.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 9 (3–4): 213–225.

- Westling, Emma L , Liz Sharp , Marta Rychlewski , and Chiara Carrozza . 2014. “Developing Adaptive Capacity Through Reflexivity: Lessons from Collaborative Research with a UK Water Utility.” Critical Policy Studies 8 (4): 427–446.

- Wickson, Fern , and Anna L Carew . 2014. “Quality Criteria and Indicators for Responsible Research and Innovation: Learning from Transdisciplinarity.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (3): 254–273.

- Wynne, Brian. 2007. “Public Participation in Science and Technology: Performing and Obscuring a Political–Conceptual Category Mistake.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 1 (1): 99–110.