ABSTRACT

This article focuses on how collective improvisation, as a play with situational affordances and constraints, can facilitate or elicit luck in social innovation processes. We propose the improvisation perspective to offer a means to move from ungovernable to governable serendipity in innovation. Furthermore, the article presents Trasformatorio, an innovation methodology based on the living lab approach, that takes innovation-through-improvisation as its premise. Following an analysis of Trasformatorio’s social innovation efforts, we conclude that while governing serendipity may be a challenge, improvisation provides an opportunity to innovate responsibly. Improvisation refocuses ideas about unexpectedness and anchors the unforeseen to a process approach. This, in turn, leads to insights about how responsible social innovation can be governed by means of (1) situation awareness; (2) collective brokering; and (3) explicit reflection about how product and process, here conceptualised as part of a Design Space and Narrative Space respectively, interrelate.

Introduction

How can innovators make more productive use of luck? When is something considered lucky in an innovation trajectory? Do things sometimes just happen? And are there certain predictors or indicators, affordances or constraints, that more readily facilitate or even elicit luck in innovation processes? In this article, we discuss how luck, in the guise of serendipity, has not only been observed in one particular innovation approach – the living lab – but also propose a tested living lab methodology that takes the productive collective embracing of serendipity as a starting point to social innovation processes: the Trasformatorio method. While social innovation is defined in many different ways (see e.g. Avelino et al. Citation2019) we follow Dawson and Daniel’s definition who see it as ‘the process of collective idea generation, selection and implementation by people who participate collaboratively to meet social challenges’ (Citation2010, 16). Social innovation often involves citizen participation and ‘encourages self-organisation of citizens’ (Edwards-Schachter, Matti, and Alcántara Citation2012, 675) to ‘[contribute] to the welfare of society and improving social capital’ (Dawson and Daniel Citation2010, 15). As a social innovation practice, Trasformatorio is a site-specific performance research lab that aims to ‘work on real world problems with real people in a real location’ (Van Kranenburg Citation2019) to connect ‘innovative technical and artistic content’ and create performances that aim at ‘inclusivity, respecting the environment and human elements [within it]’ (Trasformatorio Citation2020). A key component of the Trasformatorio method is collaborative, site-specific, improvisation to generate serendipitous socio-technical discoveries. In a recent European project called LEDGER, the project coordinators employed the Trasformatorio method to allow LEDGER-participants to realise social innovation with local communities in Giampilieri, Sicily.

We argue that framing serendipitous processes as improvisation helps address the problem of seeing serendipity as non-governable. Improvisation, literally something that is unforeseen (Montuori Citation2003), is at its core a practice of play with structures: with contextual, socio-technical information. The term improvisation can be associated with makeshift solutions to a (sudden) problem or obstacle, but is also seen as a virtuosic use of skill as in jazz performance (Sawyer Citation2000). To improvise is therefore to play with elements in a given situation in such a way that a goal is reached, even if that goal is to play. We use the example of the Trasformatorio method to argue that framing technological innovation in social innovation processes as an improvisation practice enables one to (1) draw contextual, situated expertise into ideas about serendipitous, ‘lucky’ discoveries, (2) underline the collective nature of (technological) innovation processes by drawing attention to the brokering work involved in seemingly lucky innovation processes to (3) ultimately connect ideas about serendipitous innovation to recent ideas about responsible innovation for instance Timmermans et al.’s discussion of the importance of social labs that offer spaces where experts and stakeholders can do ‘social experiments in a practical context […] without being constrained by predetermined project plans (…) [and] without knowing exactly how to proceed [Hassan Citation2014]’ (Timmermans et al. Citation2020, 3). Our central argument rests on the idea that retrospectively recognised serendipitous insights are the outcome of complex socio-technical improvisation practices, and that these improvisation practices can be systematically facilitated and even governed in social innovation processes through methods like Trasformatorio.

In order to make our case we draw on literature from management and organisation studies, media studies, as well as innovation studies. This article engages with the Journal of Responsible Innovation’s special issue’s goals and themes by considering how, through improvisation, social innovation processes can productively facilitate and embrace serendipity. Furthermore, besides a more theoretical focus on reframing serendipitous occurrences as improvisation practices, the article presents a methodology that is based on the notion that, through the Trasformatorio method, improvisation can guide and govern social innovation practices. Trasformatorio facilitates something referred to as situation awareness throughout its collective improvisation efforts. During this collective improvisation participants in the Trasformatorio method collaborate within the methodology’s created Design space and Narrative space to collectively design location-based social innovations. We discuss how the Trasformatorio method was used in the recent European project, LEDGER, to support the assertion that sustainable improvisation is a way forward; to see serendipity not as ‘merely’ a case of ‘getting lucky’ but as part of a social innovation methodology that can, in fact, be governed responsibly.

This article consists of 4 sections. In the next section we discuss how improvisation and serendipity relate and contextualise discussions about serendipity and improvisation in socio-technical innovation methodologies by discussing the example of the living lab approach that seeks to situate innovation in real-life settings to elicit ‘the unforeseen’. We draw on insights about the role of serendipity in technological innovation practices organised within living labs to argue that a productive way to reposition ideas about serendipity is to view it as part of an improvisation practice; one that can be governed responsibly in living lab innovation processes. In section 2, we therefore focus on the theoretical step from serendipity to improvisation to demonstrate what this shift implies in terms of ideas about governing serendipity in technological innovation practices. One of the main opportunities of this seemingly mere semantic shift is that it has great implications in terms of the agency of both ‘the unforeseen’ as well as of collaborators within innovation practices. Serendipity seems to happen in particular conditions; improvisation is a practice that explicitly works with uncertainty and anchors ‘the unexpected’ to the innovation process.

In Section 3, we subsequently present the Trasformatorio methodology and show how it takes improvisation as its starting point in social innovation practices. We first discuss how this methodology facilitates and elicits serendipity by guiding collaborating partners in the Trasformatorio process by means of governed improvisation. We then provide preliminary insights from a most recent empirical application, when the Trasformatorio methodology was applied in July 2019 during the Horizon 2020 project, LEDGER. These insights are based on the authors’ grounded analysis of official LEDGER documentation, consisting of project documents, websites, as well as audio-visual recordings and field notes collected during LEDGER’s application of the Trasformatorio method. The material was analysed to deduce how Trasformatorio participants collaborated in the social innovation process and what this collaboration indicates about the role of improvisation and serendipity in social innovation. Section 4 concludes by discussing the implications of reframing serendipity as improvisation, from occurrence to process, and what this means for ideas about responsible governance of innovation trajectories.

It is important to note that the presented insights about the Trasformatorio methodology are preliminary; while the methodology was devised in 2013, its goal of realising social innovation through facilitated improvisation is developed as more experience is gained. As such, Trasformatorio is a living lab methodology that functions through learning-by-doing. The authors intend to continue tracing how Trasformatorio’s facilitated, collective improvisation and focus on situation awareness can be enhanced for responsible innovation.

Background: serendipity and improvisation in the living laboratory as a means to elicit the unforeseen

Improvisation literally means something that is unforeseen. In organisational theory and in management studies, the concept is used to describe the way in which people navigate with(in) structures (Montuori Citation2003). Hadida, Tarvainen, and Rose define it as ‘dealing with the unforeseen without the benefit of preparation’ (Citation2015, 6) and ‘the conception of unhindered action as it unfolds by an organisation or its members, often (yet not exclusively) in response to an unexpected interruption or change in activity’ (Citation2015, 7). This activity takes the shape of a constant orientation or positioning with respect to situations that are ‘complex, ambiguous, and ill defined’ (Drazin, Glynn, and Kazanjian Citation1999, 287). Likewise, Seham (Citation2001) refers to this positioning as a mixture of ‘making do’ and ‘letting go’, thereby drawing attention to both generative and spontaneous characterisations of the concept. Montuori (Citation2003) and Sawyer (Citation2000) furthermore describe gradations of improvisation. They relate ‘virtuosity’ to improvisations exemplified by collaborating jazz musicians to provide an alternative reading to definitions that characterise improvisation as ‘makeshift’; a temporary solution to problems brought on by unforeseen circumstances. One must know how to play an instrument properly to be able to engage in (group) jazz improvisations. Similarly, Weick (Citation1998) and Hadida, Tarvainen, and Rose (Citation2015, 19) also draw attention to how spontaneous practices of improvisation require a ‘high level of competence’; improvisation is a craft.

While improvisation is literally connected to dealing with the unforeseen, improvisation practices can be – and often are – facilitated, whether in a performance setting (jazz, theatre), or in organisational change processes. Orlikowski, for instance, applies the concept to grasp organisational transformations occurring in response to ICT adoption (Orlikowski Citation1996). She foregrounds the role of flexibility, self-organising and learning, instead of analysing change in terms of stability, bureaucracy and control. Viewing technologies-in-practice in terms of improvisation enables the articulation of how ‘situated innovations’ are realised in response to an unexpected opportunity or challenge’ (Orlikowski Citation2000, 411). Improvisation thus stresses the situated emergence of products, processes and practices through different forms of makeshift and virtuosic actions. Cultural anthropologists Ingold and Hallam (Citation2007) even propose that the concept of improvisation catches the interrelatedness of creativity and innovation. They harness creativity to improvisation to articulate how practices unfold, instead of seeing innovative products as the result of creativity. This unfolding may be spontaneous, but as Hadida, Tarvainen, and Rose (Citation2015) argue, in the analysis of organisational improvisation processes more attention should be paid to the role played by managerial moderating effects on improvisation: the efforts made by organisations to facilitate flexibility and learning in innovation trajectories for instance.

Facilitating improvisation in innovation processes requires an openness to the unforeseen, which means that perspective is important: for something to be deemed unforeseen, there needs to be an expectation of the foreseen. This aligns with ideas about perspective and perception in studies about innovation. Innovation, according to the European Commission’s Oslo Manual, ‘is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations’ (Statistical Office of the European Communities Citation2005, 47). This definition stipulates that to be innovative, a product, process or method needs to be new or improved. Garcia and Calantone (Citation2002, 113) highlight the role of perception in recognising innovation, as one must account for the perspective from which a product or process is new. This parallels descriptions of experiences of serendipity; Cunha for instance underlines that serendipity is a recognised fruitful coincidence, or ‘the accidental discovery of something valuable’ (Citation2005, 4). Of course, one can only deem a discovery valuable if one recognises it as such. In line with this, De Rond argues that serendipity is not about events, but about capability – the capability to identify ‘meaningful pairings of two or more observations, events or fragments of information that can be put to practical or strategic use’ (De Rond Citation2014, 343). He elaborates that to ‘see bridges, or “matching pairs”, is to creatively recombine events based on the appearance of a meaningful rather than causal link’ (De Rond Citation2014, 351).

Seen this way, improvisation and serendipity are alike in that they both draw attention to combining knowledge or practices creatively. Yet whereas improvisation focuses on the practice of combining, serendipity concentrates on the retrospective realisation that one has accidentally made creative, and perhaps innovative, combinations. Serendipity, while therefore experienced after the fact, is therefore not a passive experience. Indeed, as Martin and Quan-Haase (Citation2016), serendipity depends to a large extent on human agency and competence to recognise fruitful information encountering. Copeland (Citation2017, 2386) also challenges its perceived accidentalness, and stresses that serendipity is more emergent, on the intersection of luck and skill, and describes it as ‘the oblique relationship between the outcome of a discovery process and the intentions that drove it forward’. Improvisation, then, we argue, is part of the fabric of the emergent serendipitous process, in that it is the practice of skillfully adjusting intentions as the discovery process unfolds.

The focus on the unforeseen and discovery of both improvisation and serendipity can be closely linked to perceptions of newness, and by extension to ideas about innovation, innovativeness, and creativity. In product development literature, Garcia and Calantone argue that product innovation originates in invention: ‘invention becomes innovation through [iterative] production and marketing tasks’ (Citation2002, 112). Similarly, in organisation studies the diffusion or adoption process of something new is also stressed; innovation is defined as ‘the adoption of any device, system, process, problem, program, product or service that is new to the organisation’ (Cunha, da Cunha, and Kamoche Citation1999, 311). Innovation contrasts with creativity, which is viewed as ‘the creation of a valuable, useful new product, service, idea, procedure or process by individuals working together in a complex social system’ (Cunha, da Cunha, and Kamoche Citation1999). In this framework, innovation as a process primarily adopts – rather than creates or invents – the new.

While it is not our goal to redefine the relationship between innovation and creativity in order to pinpoint where serendipity and improvisation reside, we do think it is worthwhile to take a closer look at how creativity is framed in innovation processes as it will clarify how improvisation and serendipity are perceived in this body of literature. How does creativity work? And when does one become inspired: are there certain ‘traits’ that make some people more inspired than others? For instance, when they look into the nature of novelty, Martin and Wilson note that while ‘we have identified how a creative engine works [we] lack explanation of the combustion within’ (Citation2017, 417–418). As they state in their conclusion: ‘The implication is that greater understanding of discovery processes will directly enhance creative abilities and training in awareness (…) [to] enhance sensitivity to discoveries being made’ (Citation2017, 423). Other researchers also grapple with the problem of how to systematically analyse creativity as a process; by for instance delineating different ‘creativity types’ (Unsworth Citation2001) or by developing models that provide indicators for inspiration (Wartiovaara, Lahti, and Wincent Citation2019). What these studies have in common with serendipity research is a focus on identifying those indicators that would suggest a prepared mind to recognise creative insights. Yet what we argue is that focusing on innovation and serendipitous insights from the perspective of improvisation offers a way to understand this prepared mind as something that emerges and is facilitated in context. This processual understanding of serendipity can subsequently help to some extent govern serendipity in social innovation processes.

Facilitating the experience of serendipity as well as the practice of improvisation involves ‘providing an environment where unintentional events can occur’ (De Rond Citation2014, 354). In addition to this, the above clarifies that both require a kind of mental preparedness or mental space as well. In order to trace, in practice, how one such an environment can be offered in social innovation practices, we now turn to an innovation approach and methodology that attempts to situate innovation in a physical and mental environment where unintentional events are facilitated and where participants are primed to recognise serendipitous insights through collective improvisation: the living laboratory, or living lab.

The living lab approach is an open innovation approach that has a multi-levelled character: on the organisational level, living labs are characterised as collaborations between public, private, and civic partners; on the methodological level, living labs engage in open innovation (Chesbrough Citation2003) and employ diverse design methods that place the innovation’s foreseen end user at the centre of design processes (see Pallot et al. Citation2010 for a comprehensive overview of living lab methodologies); on the situational level, living labs operate in daily life settings (Dell’Era and Landoni Citation2014), in order to design, develop and test innovations in a real life setting instead of in a Research and Development (R&D) laboratory. The term living lab was arguable coined by Mitchell when he described MIT’s Placelab (Eriksson, Niitamo, and Kulkki Citation2005). Living labs are growing in numbers; in 2006, the European Network of Living Labs was founded, which currently includes over 150 living labs across the world (European Network of Living Labs Citation2020). Living labs invite the unforeseen by opening up the innovation process to different views and practices of different actors (such as citizens) and by situating the innovation process in daily life environments to arguably uncover ‘knowledge in the wild’ (Hutchins Citation1995). We argue that they do so in order to facilitate improvisation with technologies-in-the-making, and serendipitous insights.

Living labs can thus be defined as public-private-civic partnerships that aim to realise ICT innovation by facilitating user-centred design in daily life contexts. Ballon and Schuurman (Citation2015) synthesise different definitions of the concept and describe it as ‘both a methodology and a milieu for organising user participation in innovation processes (Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. Citation2009)’. Living labs situate their practices in the uncontrollable dynamics of daily life (Boronowsky et al. Citation2006) to gain insights about unexpected uses and users of technologies (Almirall and Wareham Citation2008, 43). ICT users, in turn, are not only primarily included in their role of user, but also in guises mostly associated with those involved in the ICT development process, for instance as designers, co-creators, and as evaluators or testers (Sauer Citation2013). Granting users explicit agency to influence design practices reverses top R&D processes in favour of bottom-up innovation, often referred to in terms of co-creation (Almirall, Lee, and Wareham Citation2012; Van Der Walt et al. Citation2009). End users are explicitly included to discover unexpected uses of technology and to validate new products (Følstad Citation2008). Living labs can thus be said to adhere to a promise that seeks to unlock serendipity: to expect the unexpected. Or, as Grove argues, living labs work to create ‘designed serendipity’, that ‘[occurs] naturally when ideas, questions, data, or tools are broadcast to a large group of people in a way that allows everyone in the collaboration to discover what interests them, and react to it easily and creatively’ (Grove Citation2018, 100).

Not all living labs use the same user-centred design tools and methods to uncover the unforeseen. Leminen and Westerlund (Citation2017) identify different living lab archetypes that use iterative, tailoring, mass customisation or linearising innovation processes and tools to innovate. The authors also argue that those living labs that employ more iterative innovation processes in combination with customised tools are more readily deemed to discover and develop novel insights (as opposed to labs that use standard tools and engage in a linear innovation processes). This suggests that living labs that seek to realise designed serendipity facilitate more iterative forms of innovation. Especially this notion that serendipity can in some way be facilitated is interesting, also in the light of observations by Copeland (Citation2017), Makri and Blandford (Citation2012), and McCay-Peet and Toms (Citation2010) who underline that serendipity is not something that just happens, but that can be characterised as collective, processual and part of learning processes. The idea that serendipity occurs when one has a ‘prepared mind’ (Lawley and Tompkins Citation2008) or when one is – in the case of information-seeking behaviour – a ‘super encounterer’ (Erdelez Citation1999) suggests that one may prepare to experience serendipity. This echoes ideas about how, through facilitation, organisations can open themselves up to improvisation. In line with this, it is possible to argue that there are certain innovation contexts that afford serendipity more readily than others, as these prime innovators to experience serendipity.

Living labs provide such an innovation context. The living lab focus on eliciting the unexpected by including foreseen end users of technologies in innovation processes as well as by situating these processes in daily life environments matches ideas about facilitating serendipitous insights, as it seeks to open up collective innovation practices to include end users’ situated expertise in a daily life setting (Sauer Citation2013). However, generating serendipitous insights is not the same as subsequently implementing these insights into innovation processes. This is also one of the challenges identified by Hossain, Leminen, and Westerlund (Citation2019). They note, that ‘living labs face some challenges, such as temporality, governance, efficiency, user recruitment, sustainability, scalability and unpredictable outcomes’ (Citation2019, 2). As Sauer (Citation2013) argues, the unforeseen is often ‘mangled out’ (Pickering Citation1995) of living lab experiments when insights are translated into more concrete (ICT) design solutions. This may be due to project and solution push – the need to meet overarching project goals and aims, such as the drive to provide an ICT solution to a (societal) problem within a set timeframe. To maximise the usefulness of serendipitous insights in living labs, Sauer formulates guidelines that include opening up the innovation process to improvisation and recognising improvisation in the daily life setting as situated expertise (Sauer Citation2013). By doing so, living labs will be able to incorporate – often only retrospectively recognised (McCay-Peet and Toms Citation2015) – serendipitous insights throughout the innovation process.

We argue that a focus on improvisation practices in innovation processes helps govern serendipity in these processes. Reframing occurrences of serendipity as part of improvisation practices works to highlight how innovators may collaborate to create those conditions that elicit serendipitous insights. This idea aligns with recent living lab literature about how to optimise channelling ‘the unexpected’ in the living lab approach in innovation processes that suggests to employ an ‘Innovatrix methodology’ – an innovation framework that offers a way to manage the innovation process, mapping specific ‘uncertainties’ which are subsequently translated into ‘testable assumptions’ (Schuurman et al. Citation2019, 68). Furthermore, there have been experiments that successfully induce serendipitous matchmaking between living labs (Pallot et al. Citation2014). Using an online serendipity service, Pallot et al. show that while in information system’s literature much attention is paid to serendipity in information connection, there is less attention for serendipitous ‘people encountering’ or networking. Furthermore, Grove argues that it could be possible to evaluate serendipitous design using Makri and Blandford’s model of serendipity (Citation2012) that looks at serendipitous moments in terms of their unexpectedness, insightfulness, and the value added as a result of the serendipity (Grove Citation2018, 101). This is especially interesting in the context of living lab research itself, as the approach seeks to bring together different public, private and civic partners in daily life environments to open up the laboratory to stimulate unforeseen, and serendipitous insights (Coenen, Coorevits, and Lievens Citation2015); facilitating serendipitous networking and interaction is therefore key to living lab success.

Improvisation is a useful concept to study the unforeseen in living lab social innovation practices for several reasons. First of all, it explicates routes taken as processes and products emerge, in terms of a creative unfolding (Ingold Citation2010), instead of placing the emphasis on outcomes. Secondly, because improvisation draws attention to situatedness, it is useful to investigate the role played by the daily life setting in innovation processes. It emphasises situated innovation where collaborating actors may make virtuosic use of knowledge of everyday situations to engage with technologies-in-the-making. When the unforeseen is anchored to improvisation, it gains meaning throughout innovation processes. Thirdly, what connects improvisation to the living lab-idea of combining knowledge from different actors is the goal of harnessing local participants’ knowledge. This local knowledge can be referred to as a kind of tacit knowledge that informs technological development practices. Interestingly, while living labs include end users who may lack expertise in the development of ICTs, they are expected to possess and express situated knowledge; ‘knowledge embedded in a physical site or location’ (Sole and Edmondson Citation2002, 20). Living lab framing of users’ situated knowledge positions them as experts of the setting, and contributors of situated expertise.

Improvisation underlines emergent practices; it draws attention to the unforeseen, to practices as they unfold, interpreted as a (virtuosic or makeshift) play with structures. Here the concept helps specify how serendipitous insights are shaped in living lab-practices and what this implies in terms of the responsible governance of social innovation. To make our claims about the relationship between serendipity and improvisation in social innovation processes more concrete, we now turn to a real-life example. In the next section we discuss a particular living lab methodology that seeks to realise social innovation through facilitated improvisation and the recognition of local actors as situational experts: the Trasformatorio methodology.

Governing serendipity in innovation: how to prevent the ‘mangling out’ of the unforeseen in social innovation processes

The Trasformatorio methodology

Trasformatorio (2013-present) is an annual living lab for performative arts in remote communities in Sicily. It has been organised in Montelbano Elicona (province Messina, Italy), Scaletta Zanclea, and Giampilieri. Trasformatorio seeks to develop ‘innovative site-specific performances and theatre installations, in close connection with the landscape, history and traditions of the people’ (Trasformatorio Citation2020). Each Trasformatorio laboratory, a group of international artists and technologists is invited and selected to take part in co-creation workshops and initiate projects together with the local community. The main challenge for the artists is:

to go ‘back’ to the basic questions of performative arts in this specific place: ‘what can we be aware of here and transform into a vital work; a work that shares/communicates a pure reflection on what is present for us here?’. (Trasformatorio Citation2020)

The ‘transformations' that are sought, are meant to enrich the cultural exchange of both the local people and the visiting artists. Artistically reading a place means in our project: taking care of the place. Therefore, we explicitly connect research of sustainability in site-specific performative arts to the artistic research. (Trasformatorio Citation2020)

Stakeholders in the Trasformatorio methodology share knowledge to realise sustainable design, initiate and promote initiatives with local communities, and involve new businesses and investments in remote areas or between marginal(ised) groups. It combines site-specific and bottom up innovation practices with artistic research methods. It is structured in innovation phases, supplemented by sprint-denominated labs, which means that participants collaborate in short, intense, sessions to develop locally-relevant social innovations. During these sessions, all involved participants openly shape a process that is considered successful when it positively transforms the existing context, or situation. Furthermore, participation in Trasformatorio is geared at self-representation through artistic forms of expressions. The methodology is advocated in those cases where an innovation goal is the representation and empowerment of a marginalised community, and where the solution is developed in open dialogue with the local community. As such, Trasformatorio relies on bottom-up initiatives to build relevance and innovation. By means of continuous communication and feedback, the methodology seeks to realise iterative sustainable social innovation.

In practice, Trasformatorio involves post-dramatic theatrical and performance practices, book sprints (Barker, Campbell, and Hawksey Citation2013), illustration, gamification, learning by doing environments, and happenings achieve the early integration of local need analysis. These practices work as on-site tools to allow the desired cross-fertilisation between technical and artistic practices and the local community. The outcome of collaborations between local community members, artists and technicians is referred to as the Narrative. Trasformatorio seeks to catalyse energies and set a shared goal for the involved actors to develop an active community with efficient use of resources by developing the Narrative of the situation itself together with the elaboration of technology and design prototypes.

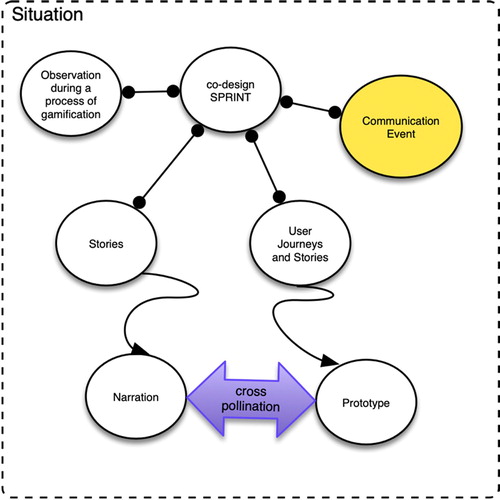

As illustrates, the basic conceptual element of a transformation is a situation. After assessing the situation, a co-design session is organised within the community. This session, or sprint, ends with a showcase event that presents the results to a general local audience. This allows the inclusion of the communication effort as a part of the sprint and enlarges the local community awareness of the work done. This showcase event parallels artistic methodologies, such as Boal’s theatre of the oppressed in which audience members become participants in performances (Boal Citation2006).

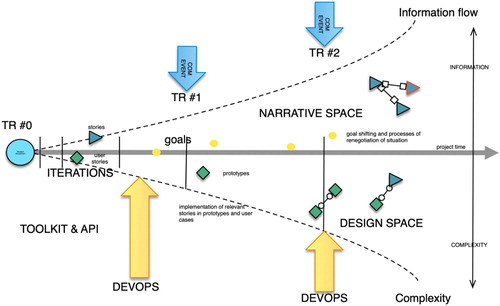

In the first sprint (T#0 in ) the outcome is a first situation assessment and includes (1) the creation of the first group of (local) agents; (2) the delimitation of the community and its territory; (3) the refinement of project objectives, and (4) the analysis and implementation of technologies and practices to fulfil the objectives of the project. The outcome of a sprint is measurable: number of stories, relevance, number of co-designers involved, qualitative analysis of problem, use cases, prototype acceptance and use, analysis documents, and participation.

The Trasformatorio methodology creates two macro environments throughout its innovation process (): the Narrative space, where events and observations are organised as stories, and the Design Space, were stories are re-shaped as use cases and organised in user journeys and prototypes are devised (together with a software developer team, referred to as Devops in ), implemented and tested. The project stories become the general Narrative space of self-representation developed by the project in the target community. These stories are also tightly integrated into the dissemination and the documentation of the project, making it possible to reflect on how the formation of the Narrative and Design space unfold in practice.

The Trasformatorio methodology can subsequently be resumed starting from its components: (1) establish a core activity within all the partners and stakeholders that helps transform a situation with active action evolving into a positive local narrative; (2) catalyse processes of co-design and self-representation integrating art practices; (3) allow and curate positive feedback cycles to appear, and design, implement and disseminate at the same time. As the design process develops, the complexity of the solution is supported by the implementation of a Trasformatorio toolkit. This toolkit is explicitly ‘unfinished’ (Smyth and Helgason Citation2017), open to adaptation through negotiation, and reshaped by shifting project goals in a process of self-adaptation to maintain a level of usability and general acceptance. The toolkit adjusts in line with participants’ needs, for instance if more or less technical support is required.

In line with living lab practices of placing users at the centre of innovation practices, the Trasformatorio methodology aims to stimulate the seeding of user communities in a sustainable and open way with a bottom-up approach. Improvisation practices in Trasformatorio focus on treating local knowledge shared by the local population as situated expertise. This implies that as an innovation methodology Trasformatorio enrols citizens as innovators and opens up ideas about what it means to do social innovation to unforeseen situated experience that is local – tacit – knowledge, and unique to the specific citizens’ community.

In the next section we present a recent Trasformatorio project example to illustrate how Trasformatorio governs serendipity in social innovation processes by facilitating improvisation practices. It is important to note that insights are based on audio-visual material and field note data that was collected by one of the authors about participants’ activities and experiences. This data was subsequently analysed using grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2006) to ascertain how participants’ experiences of serendipity and improvisation shaped the social innovation process. Applying grounded theory here helps understand the experience of improvisation and serendipity in participants’ own words. In section 3.3 we discuss what the implications are of this example and its reframing of serendipity as an occurrence in terms of an improvisation practice for the governance of social innovation processes, and how this relates to ideas about responsible innovation.

Trasformatorio 2019: improvisation and serendipity in social innovation

As part of the overarching Horizon2020 LEDGER project (https://ledgerproject.eu) that runs between November 2018 and July 2021, 32 social innovation start-ups (16 between 2019 and 2020 and 16 between 2020 and 2021) take part in a number of innovation workshops that are part of the project’s 12-month ‘venture builder’ program. LEDGER ‘empowers people to solve problems using decentralised technologies such as blockchain, peer to peer or distributed ledger technologies’ (LEDGER Citation2020). Each start up team, comprising of different combinations of engineers, (graphic) designers, coders, as well as a number of anthropologists, takes active part in project workshops and sprints ().

One of these workshops applies the Trasformatorio methodology to realise social innovation through on-site improvisation with local communities; in October 2019 members of the first 16 start-upsFootnote 1 travelled to Sicily for 1 week to co-design human-centric social innovation solutions together with the local community, with each other, and with available materials. The challenge was to apply Trasformatorio’s design principles to formulate a social innovation project in collaboration with the local community.

In this particular Trasformatorio week, this meant that the start-up groups collaborated with each other and with local actors such as a local beer cooperative (Synergy team), high school students (Decentralised Science and Consento teams), owners of electronics repair shops (Ereuse team), health clinics (OneHealth team), food markets (Food Data Market team), and the more general population (AIUR, Heimdall, Unified Science and Merits teams) to connect to the seeds of different ‘innovation communities’ (Van Oost, Verhaegh, and Oudshoorn Citation2009).

Although the start-up teams freely explored the local situation and community needs, the week itself was structured: on day 1, the teams had an ‘observation day’ to assess the situation, talk with local people and groups, and map their surroundings; on days 2 and 3 the teams analysed their observations, in order to, on day 4 present their ideas in an open setting. In all cases, the start-up teams started collecting innovation ideas by talking and listening to the local community. As one team member states: ‘by opening up the question to the community instead of bringing a solution, rather open a conversation with them to see what that can inspire’ (Decentralised Science team). This also meant opening up ideas about technological solutions to the ideas and concerns of local citizens. As one of the team members of start-up team AIUR states: ‘Immigration [as an issue] was the idea. As we talked to the local community, we realised that there is much more that we can do here. More than debunking immigration’s negative perception’. Doing bottom-up research with local citizens also brought other questions to the surface, such as thoughts about ‘the ethical implications of being strangers. What needs are there?’ (Heimdall team).

The different start-up teams sought connections to different communities and even the built environment, such as an abandoned train station, as they realised that those empty spaces told stories too. Stories related to perceived issues with a lack of sustainable tourism, environmental concerns about how to reduce plastic waste in the sea, and feelings of worry about the possible recurrence of flash floods in the area. These stories inspired ideas to build connections between communities to for instance start setting up local clean-up groups, introduce electric buses to transport tourists to and from the harbour, and organise a local network of people who can be alerted by sensors in case of an impending flood.

All these ideas grew out of conversations with the local population, and out of what one of the Trasformatorio facilitators calls situation awareness:

Situation awareness is more valuable than the information that you bring with you. The exercise of extracting information taught us a lot of lessons, about expectations, about where we take our information, about the different types of information you get (…) if you speak the [Italian] language and if you don’t speak the language, if you have contacts or no contacts. There were lots of different strategies that were put into place. (LEDGER Citation2020)

Situation awareness is a term used across different disciplines, ranging from military theory, air traffic control and design theory to describe ‘to know what is going on’ (Choi and Park Citation2018, 624). Here, it requires an openness to unexpected insights: letting an abandoned train station inspire ideas about improving transportation, or thinking about a communal alert system to warn the general population about flood danger.

The Trasformatorio team facilitated and brokered idea development with the local community, for instance by working with the local press to inform the community that groups participating in Trasformatorio would be in the area. This attracted positive responses from the community. Apart from organising the workshop itself, the Trasformatorio team recorded the 16 start-ups process of developing and reflecting upon their social innovation ideas. At the end of the workshop, the teams presented their ideas. On reflecting on their experiences, one participant notes that:

If you form a team it is always the same process. It is forming, norming, storming and performing. And then you end up in equilibrium. When that equilibrium is tested you always end up in the same process, forming, norming, storming, performing. And every single pivot is on that point, that stresses your team to the limit. Some leave, split (…) Really not coming [here] with a solution, but hearing out what are the conditions has been one of the most rewarding experiences I have ever had in my life. (team member Unified Science)

Trasformatorio helped stimulate an awareness in the design teams that hands-on listening to the situated expertise of local, potential innovation communities is invaluable to social innovation processes. Apart from this awareness, Trasformatorio also had outcomes that helped strengthen social innovation in the local community: specific teams continued their collaborations to realise particular ideas. An example of this includes the Unified Science team’s flood awareness system, which the team is planning to donate to the community in the summer of 2020. To realise this system, the start-up team is collaborating with the local community, and with Trasformatorio facilitating team. One of the other teams, Synergy, devised a possible collaboration between two local cooperatives (one cooperative in beer production, the other in grain production), to locally produce malt. Admittedly, these outcomes are yet to be finalised, but originated in ‘lucky’ connections that were made during the week.

Trasformatorio: serendipity and improvisation in action

Essentially, the Trasformatorio methodology facilitates collaboration between actors – in this case start-up teams and local communities – in a way that foregrounds and takes as its point of departure situation awareness. Situation awareness opens up the social innovation process to unforeseen ideas, spaces, and local expertise. In other words, it helps participants to embrace change and chance. While this mirrors more general living lab approach ideas about incorporating daily life contexts into innovation processes, Trasformatorio further enriches the living lab approach by making openness to situations and ‘unexpectedness’ part of its facilitated methodology, thereby purposefully inviting the occurrence of serendipitous insights. This is realised by making collaborating actors not only listen to local communities’ ideas and concerns, but by simultaneously making teams reflect on how the act of listening shapes their awareness (of communities, problems, ideas, possible solutions). In this way, the start-up teams’ and community experiences were part of the construction of both the Narrative as well as the Design spaces. As part of the construction of these spaces, the team members played with structures in the setting, be these structures social (e.g. how communities respond to the teams), environmental (the role of the sea in the communities), physical (empty buildings) or psychological (how community members reflect on the role of immigrants, and tourists). Playing with structures, as a definition of what it means to improvise, characterised their experiences, and formed the social innovation process.

Brokering, as a form of negotiation between actors, plays an important role in this improvisation and innovation practice. Creating stories together is part of the Trasformatorio methodology; as these stories not only form the innovation community, but also inform design solutions. This is also where attention can be drawn to the responsible governance of serendipity of social innovation. Fraaije and Flipse (Citation2019) clarify that Responsible Research & Innovation literature underlines the importance of transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation and responsiveness as contributing factors to responsible product development. More specifically, Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013, 1571) note that in scientific laboratories that try to work towards being more reflexive, efforts are made to ‘include social scientists as well as philosophers in order to raise awareness to the socio-ethical context’ of laboratory work. Trasformatorio’s focus on social innovation through situation awareness and improvisation, as a play with(in) structures, embraces anticipation and responsiveness, while simultaneously facilitating reflexivity – here exemplified by participants’ reflections on their own design process – inclusion and transparency within the innovation community. What furthermore happens in recognising improvisations within Trasformatorio as informed by situated expertise, is that all innovation actors (be they from the local community, the start-up team or the facilitating Trasformatorio team) become innovation owners of both the innovation process and product. In other words, as a living lab wherein public, private, and civic partners become owners of the social innovation process and product, Trasformatorio works to challenge top down design power structures that are observed to limit responsible innovation (De Hoop, Pols, and Romijn Citation2016).

Serendipity, as a deemed lucky occurrence or insight, is readily part of the approach; yet, fortuitous things that ‘just happen’ are seen as part of the improvisation practice and are therefore not treated as lucky, but rather as part of the methodology’s premises. Luck is embedded in cultivating situation awareness as a kind of ‘prepared mind’; in seeing where the Narrative space and Design space do or do not overlap. Key to embracing improvisation as a starting point in social innovation is the awareness that contextual constraints and affordances shape socio-technical interactions (Sauer and de Rijke Citation2016). Within Trasformatorio’s Narrative space for instance, improvisation may be governed by collaborative goal-setting, shared information, and even language use. In the Design space possible improvisation can be material (technological, physical environment) or immaterial (visualisations, ideas about how to design using e.g. a toolkit, prototypes, performance, events). Collaborating actors can experience serendipity as they navigate these spaces, governed by the improvisation practices that form the starting point of the methodology.

Conclusion: serendipity as part of responsible innovation through governed improvisation

The central argument of this article is that retrospectively recognised serendipitous insights are the outcome of complex socio-technical improvisation practices. Furthermore, based on the examples of the living lab approach and the Trasformatorio methodology, we argue that improvisation practices can be governed within social innovation trajectories by making the play with structures or affordances and constraints not merely part of the innovation process but by ensuring an explicit focus on reflection on how this play informs the innovation process.

This requires a rethinking of what these affordances and constraints entail. In the example of the Trasformatorio methodology, these take the shape of the Narrative and Design spaces respectively; both spaces call for situation awareness. Situation awareness, as a kind of context-sensitivity, moves beyond the living lab ideas of situating design in a daily life context (as a test bed for instance). Instead, context-awareness, together with the openness to collaborate through improvisation, form the starting points of Trasformatorio.

The shift from thinking about luck in innovation in terms of a recognised outcome of serendipitous insights to thinking about luck as the outcome of (collective) improvisation is more than merely semantic or conceptual. While it does suggest a shift from thinking about serendipity as an occurrence to a process, research into serendipity has underlined processual serendipity before (Copeland Citation2017; Makri and Blandford Citation2012). What the improvisation perspective offers is a means to start thinking about how the step can be made between ungovernable serendipity and governed improvisation in responsible innovation processes.

As the example of Trasformatorio clarifies, practicing the responsible governance of improvisation processes means (1) organising social innovation as collective innovation in which (2) all actors contribute situated expertise and where (3) the innovation process or trajectory is recognised as one characterised by brokering activities that help practitioners explicitly reflect on situation awareness and on how the process shapes the product or process outcome. What this means is a move away from seeing serendipity as something that just happens and away from ‘mangling out’ (Pickering Citation1995) unforeseen ideas, processes, practices or opinions, towards seeing serendipity as something that is facilitated by a play with(in) structures, and by improvisation practices.

This does align with ideas about serendipity occurring when one has a prepared mind, in the sense that the innovation approach itself is organised to ‘be prepared’; organised in such a way as to be opened up to unforeseen insights (by e.g. using the approach of Smyth and Helgason to design toolkits for negotiation (Citation2017)). This, in other words, is part of the methodology’s agenda. This also connects well to current ideas about the governance of responsible innovation. As Fraaije and Flipse (Citation2019) show, responsible innovation literature highlights the importance of ‘transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation and responsiveness’, which are concepts that Trasformatorio embraces in its situated awareness approach, and in its combining of different, interacting, innovation spaces.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the LEDGER project and its participants for sharing their experiences, and would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful suggestions throughout the review process. The authors also thank Dan Leberg for feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Sabrina Sauer is an assistant professor at the University of Groningen's Research Centre for Media and Journalism Studies. She has an M.A. in Media Studies from the University of Amsterdam and a Ph.D. in Science and Technology Studies from the University of Twente. She has published about audiovisual narrative creation, user research, exploratory search, and serendipity. Her current research focuses on the use of Big Data in media production practices, social innovation, interdisciplinary brokering, and digital humanities.

Federico Bonelli is an independent researcher and artist. He has training in philosophy of science, history of mathematics and arts. Bonelli is not only an explorer of aesthetic forms, but also an empirical researcher. He previously worked with Philips Research and other artists on realising the Protoquadro (2003): a deterministic techno-pictorical object in constant change, never equal to itself and unpredictable. Since 2012 he directs the international site-specific laboratory ‘trasformatorio’ he founded.

Notes

1 For a complete overview of the 16 start-ups, please see https://ledgerproject.eu/2019/05/30/ledger-selects-16-human-centric-projects-working-on-decentralised-technologies-to-enter-its-venture-builder-programme/.

References

- Almirall, Esteve , Melissa Lee , and Jonathan Wareham . 2012. “Mapping Living Labs in the Landscape of Innovation Methodologies.” Technology Innovation Management Review 2 (9): 12–18.

- Almirall, Esteve , and Jonathan Wareham . 2008. “Living Labs and Open Innovation: Roles and Applicability.” eJOV: The Electronic Journal for Virtual Organization & Networks 10: 21–46.

- Avelino, Flor , Julia M. Wittmayer , Bonno Pel , Paul Weaver , Adina Dumitru , Alex Haxeltine , and Tim O’Riordan . 2019. “Transformative Social Innovation and (dis) Empowerment.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145: 195–206.

- Ballon, Pieter , and Dimitri Schuurman . 2015. “Living Labs: Concepts, Tools and Cases.” Info 17 (4): 1–11.

- Barker, Phil , Lorna M. Campbell , and Martin Hawksey . 2013. “Writing in Book Sprints.” In Proceedings of OER13: Creating a Virtuous Circle. Nottingham, England. Accessed January 3, 2020. http://publications.cetis.org.uk/2013/764 .

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, Birgitta , Carina Ihlström Eriksson , Anna Ståhlbröst , and Jesper, Svensson. 2009. “A Milieu for Innovation – Defining Living Labs.” Presented at the 2nd ISPIM Innovation Symposium, New York, December 6–9.

- Boal, Augusto. 2006. The Aesthetics of the Oppressed . London : Routledge.

- Boronowsky, Michael , Otthein Herzog , Peter Knackfuß , and Michael Lawo . 2006. “Wearable Computing – An Approach for Living Labs.” In 3rd International Forum on Applied Wearable Computing 2006, 1–8. VDE.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis . London : Sage Publications Ltd.

- Chesbrough, Henry William. 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting From Technology . Boston, MA : Harvard Business School Press.

- Choi, Byounghyun , and Woojin Park . 2018. “Applying a Theory of Situation Awareness to Idea Generation: Mitigation of Design Fixation.” In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018), edited by Sebastiano Bagnara, Riccardo Tartaglia, Sara Albolino, Thomas Alexander, and Yushi Fujita, 622–628. Cham: Springer.

- Coenen, Tanguy , Lynn Coorevits , and Bram Lievens . 2015. “The Wearable Living Lab: How Wearables Could Support Living Labs.” In Open Living Lab Days, Istanbul, 25–28 August.

- Copeland, Samantha. 2017. “On Serendipity in Science: Discovery at the Intersection of Chance and Wisdom.” Synthese 196 (6): 2385–2406. doi:10.1007/s11229-017-1544-3.

- Cunha, Miguel. P.E. 2005. “Serendipity: Why Some Organizations are Luckier Than Others”. Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Ed.), FEUNL Working Paper Series .

- Cunha, Miguel. P.E. , Joao Vieira da Cunha , and Ken Kamoche . 1999. “Organizational Improvisation: What, When, How and Why.” International Journal of Management Reviews 1 (3): 299–341.

- Dawson, Patrick , and Lisa Daniel . 2010. “Understanding Social Innovation: A Provisional Framework.” International Journal of Technology Management 51 (1): 9–21.

- De Hoop, Evelien , Auke Pols , and Henny Romijn . 2016. “Limits to Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 110–134. doi:10.1080/23299460.2016.1231396.

- De Rond, Mark. 2014. “The Structure of Serendipity.” Culture and Organization 20 (5): 342–358.

- Dell’Era, Claudio , and Paolo Landoni . 2014. “Living Lab: A Methodology Between User-Centred Design and Participatory Design.” Creativity and Innovation Management 23 (2): 137–154.

- Dougherty, Dale. 2012. “The Maker Movement.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 7 (3): 11–14.

- Drazin, Robert , Mary Ann Glynn , and Robert K. Kazanjian . 1999. “Multilevel Theorizing About Creativity in Organizations: A Sensemaking Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 24 (2): 286–307.

- Edwards-Schachter, Mónica E. , Cristian E. Matti , and Enrique Alcántara . 2012. “Fostering Quality of Life Through Social Innovation: A Living Lab Methodology Study Case.” Review of Policy Research 29 (6): 672–692.

- Erdelez, Sanda. 1999. “Information Encountering: It’s More Than Just Bumping Into Information.” Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 25 (3): 26–29.

- Eriksson, Mats , Veli-Pekka Niitamo , and Seija Kulkki . 2005. State-of-the-Art in Utilizing Living Labs Approach to User-Centric ICT Innovation-a European Approach . Lulea : Center for Distance-spanning Technology.

- European Network of Living Labs . 2020. “What are Living Labs.” Accessed July 26, 2020. https://enoll.org/about-us/ .

- Følstad, Asbjørn. 2008. “Living Labs for Innovation and Development of Information and Communication Technology: A Literature Review.” eJOV 10: 99–131.

- Fraaije, Aafke , and Steven M. Flipse . 2019. “Synthesizing an Implementation Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/23299460.2019.1676685.

- Garcia, Rosanna , and Roger Calantone . 2002. “A Critical Look at Technological Innovation Typology and Innovativeness Terminology: A Literature Review.” Journal of Product Innovation Management: An International Publication of the Product Development & Management Association 19 (2): 110–132.

- Grove, Wouter. 2018. “Living Labs and Designed Serendipity: Collaboratively Discovering the UDUBSit & Mfunzi Emerging Platforms.” Afrika Focus 31 (1): 91–113.

- Hadida, Allègre L. , William Tarvainen , and Jed Rose . 2015. “Organizational Improvisation: A Consolidating Review and Framework.” International Journal of Management Reviews 17 (4): 437–459.

- Hassan, Zaid. 2014. The Social Labs Revolution: A New Approach to Solving Our Most Complex Challenges . First Edition. San Francisco, CA : Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

- Hossain, Mokter , Seppo Leminen , and Mika Westerlund . 2019. “A Systematic Review of Living lab Literature.” Journal of Cleaner Production 213: 976–988.

- Hutchins, Edwin. 1995. Cognition in the Wild . Cambridge, MA : MIT Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 2010. “The Textility of Making.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (1): 91–102.

- Ingold, Tim , and Elizabeth Hallam . 2007. Creativity and Cultural Improvisation . Oxford : Berg.

- Lawley, James , and Penny Tompkins . 2008. Maximising Serendipity: The Art of Recognising and Fostering Potential. Esitetty tilaisuudessa The Developing Group.

- LEDGER . 2020. The Venture Builder for Human Centric Solutions. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://ledgerproject.eu .

- Leminen, Seppo , and Mika Westerlund . 2017. “Categorization of Innovation Tools in Living Labs.” Technology Innovation Management Review 7 (1): 15–25.

- Makri, Stephann , and Ann Blandford . 2012. “Coming Across Information Serendipitously–Part 1: A Process Model.” Journal of Documentation 68 (5): 684–705.

- Martin, Kim , and Anabel Quan-Haase . 2016. “The Role of Agency in Historians’ Experiences of Serendipity in Physical and Digital Information Environments.” Journal of Documentation 72 (6): 1008–1026. doi:10.1108/JD-11-2015-0144.

- Martin, Lee , and Nick Wilson . 2017. “Defining Creativity with Discovery.” Creativity Research Journal 29 (4): 417–425.

- McCay-Peet, Lori , and Elaine G. Toms . 2010. “The Process of Serendipity in Knowledge Work.” Proceedings of the third symposium on Information interaction in context, 377–382.

- McCay-Peet, Lori , and Elaine G. Toms . 2015. “Investigating Serendipity: How it Unfolds and What may Influence it.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66 (7): 1463–1476.

- Montuori, Alfonso. 2003. “The Complexity of Improvisation and the Improvisation of Complexity: Social Science, art and Creativity.” Human Relations 56 (2): 237–255.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. 1996. “Improvising Organizational Transformation Over Time: A Situated Change Perspective.” Information Systems Research 7 (1): 63–92.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. 2000. “Using Technology and Constituting Structures: A Practice Lens for Studying Technology in Organizations.” Organization Science 11 (4): 404–428.

- Pallot, Marc , Alex Alishevskikh , Thomas Holzmann , Piotr Krawczyk , and Rudolf Ruland . 2014. “CONEX: Creating serendipitous connections among Living Labs and horizon 2020 Challenges.” 2014 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE), 1–7.

- Pallot, Marc , Brigitte Trousse , Bernard Senach , and Dominique Scapin . 2010. “Living Lab Research Landscape: From User Centred Design and User Experience towards User Cocreation.” First European Summer School “Living Labs”, Inria (ICT Usage Lab), Userlab, EsoceNet, Universcience, Aug 2010, Paris, France.

- Pickering, Andrew. 1995. The Mangle of Practice: Time, Agency, and Science . Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

- Sauer, Sabrina. 2013. “User Innovativeness in Living Laboratories: Everyday User Improvisations with ICTs as a Source of Innovation.” PhD diss., University of Twente.

- Sauer, Sabrina , and Maarten de Rijke . 2016. “Seeking Serendipity: A Living Lab Approach to Understanding Creative Retrieval in Broadcast Media Production.” Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 989–992.

- Sawyer, R. Keith. 2000. “Improvisational Cultures: Collaborative Emergence and Creativity in Improvisation.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 7 (3): 180–185.

- Schuurman, Dimitri , Aron-Levi Herregodts , Annabel Georges , and Olivier Rits . 2019. “Innovation Management in Living Lab Projects: The Innovatrix Framework.” Technology Innovation Management Review 9 (3): 63–73.

- Seham, Amy E. 2001. Whose Improv is it Anyway? Beyond Second City : Univ. Press of Mississippi.

- Smith, Thomas S.J. 2017. “Of Makerspaces and Hacklabs: Emergence, Experiment and Ontological Theatre at the Edinburgh Hacklab, Scotland.” Scottish Geographical Journal 133 (2): 130–154. doi:10.1080/14702541.2017.1321137.

- Smyth, Michael , and Ingi Helgason . 2017. “Making and Unfinishedness: Designing Toolkits for Negotiation.” The Design Journal 20 (1): 3966–3974. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1352899.

- Sole, Deborah , and Amy Edmondson . 2002. “Situated Knowledge and Learning in Dispersed Teams.” British Journal of Management 13 (2): 17–34.

- Statistical Office of the European Communities . 2005. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data 4, Publications de l'OCDE.

- Stilgoe, Jack , Robert Owen , and Phil Macnaghten . 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580.

- Timmermans, Job , Vincent Blok , Robert Braun , Renate Wesselink , and Rasmus Øjvind Nielsen . 2020. “Social Labs as an Inclusive Methodology to Implement and Study Social Change: The Case of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation . doi:10.1080/23299460.2020.1787751.

- Trasformatorio . 2020. “Trasformatorio #0: White Paper and Report”. Accessed January 2, 2020. http://trasformatorio.net/?page_id=2702 .

- Unsworth, Kerrie. 2001. “Unpacking Creativity.” Academy of Management Review 26 (2): 289–297.

- Van Der Walt, Jacobus S. , Albertus A.K. Buitendag , Jan J. Zaaiman , and Joey Jansen Van Vuuren . 2009. “Community Living Lab as a Collaborative Innovation Environment.” Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology 6 (1): 421–436.

- Van Kranenburg, Rob. 2019. “NGI Ledger Opens Up for Second Round of Funding.” Edgeryders.eu, November 19. https://edgeryders.eu/t/ngi-ledger-opens-for-second-round-of-funding/11346 .

- Van Oost, Ellen , Stefan Verhaegh , and Nelly Oudshoorn . 2009. “From Innovation Community to Community Innovation: User-Initiated Innovation in Wireless Leiden.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 34 (2): 182–205.

- Wartiovaara, Markus , Tom Lahti , and Joakim Wincent . 2019. “The Role of Inspiration in Entrepreneurship: Theory and the Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 101: 548–554.

- Weick, Karl E. 1998. “Introductory Essay – Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis.” Organization Science 9 (5): 543–555. doi:10.1287/orsc.9.5.543.