ABSTRACT

This paper presents a new ethics by design tool: The Moral-IT Deck. The deck is a set of physical cards that prompt reflection on normative aspects of technology development. Coupled with our Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board, they help technologists to reflect on how to address emerging ethical risks and implement appropriate safeguards. We present the card deck, their development and our empirical evaluation. The cards and board enable designers to reflect on challenges posed by their system and plan how to act in response. Our key findings relate to three themes, namely: the value of our cards as a tool, their impact on the technology design process, and how they structure ethical reflection. Key lessons and concepts conclude the paper, documenting how the cards level the playing field for debate; enable ethical clustering, sorting and comparison; provide appropriate anchors for discussion, and highlight the intertwined nature of ethics.

Part I: Introducing the Moral-IT Deck

Introduction

Building ethical technologiesFootnote1 can be difficult and we believe better practical tools are needed to support the role of technologists in addressing ethical issues during system design. In response, our objective in this project (‘Moral-IT: Enabling Design of Ethical and Legal IT Systems' research project funded by the Horizon Digital Economy Research Institute under EPSRC Grant EP/M02315X/1) was to develop a practical tool and methodology to support reflection by technologists on normative aspects of technology development, particularly at the early stages of design. To do this, we designed, tested and evaluated The Moral-IT Deck and Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board. The Moral-IT Deck is a set of physical cards that pose questions to teams of designers about the technology they are creating. Drawing together human computer interaction, computer ethics and design perspectives, the cards present questions and concepts in four suits (ethical, legal, privacy and security ). These raise awareness of ethics in design by questioning the values and practices being embedded into their systems. They are used with the Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board, which provides a streamlined process for a team to collaboratively discuss and map out emerging risks, likelihood of occurrence, appropriate safeguards and challenges of addressing these. This process results in a plan for the team that will support them in building a more ethical system.

Our practical approach to ethics by design is novel insofar it combines a tool for reflection (the deck) and process for mapping out appropriate responses and plans for action (the board). The development process adopted a multidisciplinary approach to considering design, norms and strategies for action, with information technologies primarily in mind, further adding to their value.

In this paper, we document how these cards have been developed and then tested within 5 workshops with 20 participants from both research and commercial settings. The cards pose questions requiring critical reflection and situated judgements on how best to proceed with value judgements. They were tested in this case with the Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board to structure and manage deliberation on ethical responsibilities. This combination is novel and seeks to combine reflection with a strategy for action, by requiring technologists to reflect on the ethical tensions raised by the cards for their technology and to respond.

The structure of this paper starts by mapping out the field in relation to cards and ethics. We do this by considering the turn to the role of technologists in ethical deliberation, particularly how the normative dimensions of their role sit alongside functional dimensions of system design. This shift highlights the need for practical support to enable creators to consider, engage with, and address their responsibilities, so we analyse the existing mechanisms for bringing ethical reflection into design. We then unpack the value of our tool and why cards are a useful medium for reflection on complex ethical issues.

We then introduce the content of the Moral-IT cards, documenting key features of our card design, background on the content, and the process for using them. In reasoning around practical approaches to doing ethics by design, we assimilate perspectives from Science and Technology Studies (STS), IT Law, Human Computer Interaction (HCI), and Computer/Engineering Ethics. We also examine the sources that informed our impact assessment process board, before discussing our methodology for the workshops, use cases and discussion of our key findings. These are clustered around three overarching themes: the value of our cards as a tool, their impact on technology design, and how they structure ethical reflection practices. Lastly, we provide a series of empirical reflections on how card based tools can be used and the value of our tool for doing ethics by design. This includes how the cards level the playing field for debate; enable participants to navigate issues through ethical clustering, sorting and comparison; provide appropriate anchors for discussion around ethical issues and highlight the intertwined nature of ethics in practice.

Ethics by design

Our approach to ‘ethics by design’ is novel insofar as it brings together varied interdisciplinary perspectives, provides a practical card-based process for collaborative reflection, and a mechanism for mapping their plans for action, namely a structured impact assessment board. Literature with the label of ‘ethics by design’ is emerging, with recent examples focused on AI. For example, Dignum et al. (Citation2018) explore how to build agent based and artificially intelligent systems that can reason about ethical issues. Similarly, recent EU Horizon 2020 projects have engaged with ethics by design in creating requirements for building ethical robotics (SIENNA) or AI and big data systems (SHERPA), (e.g. Brey et al. Citation2020). Concurrently, law and policy initiatives increasingly turn to design to address normative issues posed by information technologies. For example, Articles 25 and 32 of the EU General Data Protection Regulation 2018 require those collecting personal data to utilise organisational and technical safeguards to support ‘data protection by design and default’ and ‘security by design’, respectively (European Data Protection Board Citation2019). Thus, we argue there are many approaches to doing ‘ethics by design’, often using different labels and going beyond the current AI focus. In Part 1, we provide insights that have motivated and shaped our approach to ‘ethics by design’ through the Moral-IT Deck.

We start with perspectives on the interface of ethics and design. Winner (Citation1978) recognised that technology design has normative impacts, stating ‘technology in a true sense is legislation. It recognizes that technical forms do, to a large extent, shape the basic pattern and content of human activity in our time’ (323). This influenced our desire to focus on the creators of technology, recognising the power they exert over human behaviour and making ethical value judgements. Latour (Citation1992) and Akrich (Citation1992) showed us how this power manifests. Latour observed that technology design involves normative decision making that delegates power to non-human entities to permit or prohibit user behaviours, stating ‘the distance between morality and force is not as wide as moralists expect, or more exactly, clever engineers have made it smaller’ (174). This builds on Akrich (Citation1992) who recognised designers embed ‘scripts’ of their world view into a system, which inscribes certain value judgments into a system. These science and technology scholars highlight the need to think critically about both values in technology and how these come to be embedded, with respect to the key role technology designers play.

This aligns with concerns from technology ethics scholars too. For example, Verbeek (Citation2006) has stated ‘engineering design is an inherently moral activity’ (368) and similarly, Millar (Citation2008) states ‘in effect, engineers ought to be considered de facto policymakers, a role that carries implicit ethical duties’ (4). In responding to this role, a sense of ‘moral overload’ is a risk for technologists (Van Den Hoven, Lokhorst, and Van der Poel Citation2012). Our cards, coupled with the impact assessment board, provide a means of working through difficult, practical moral decisions involving value trade-offs and balancing competing interests during design. Other ethical approaches such as anticipatory ethics (Brey Citation2012) and the ETICA approach (Stahl Citation2011), have also emerged to insert technology ethics thinking into value judgements during design. This often entails social scientists collaborating with, assessing and engaging with scientific processes and stakeholders, which can be time consuming, constrained by setting and conflict driven (Fisher, Mahajan, and Mitcham Citation2006; Felt, Fochler, and Sigl Citation2018, 205). This might not always be feasible, depending on scale of project resources or access for researchers or scale of work planned, e.g. start-ups; smaller projects. Accordingly, the relatively lightweight impact on resources (both in time and cost) that are offered by the cards and impact assessment board provides a valuable mechanism for structured reflection and action by technologists.

Our cards also draw on the Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) approach of finding mechanisms for thinking about ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI) of innovation (Zwart, Landeweerd, and van Rooij Citation2014). RRI unpacks the meaning of responsibility by calling into question who is responsible, for what and reflects on wider impacts of innovation (Von Schomberg Citation2013). It has different framings but fundamentally requires four key steps of anticipation, reflection, engagement and action (EPSRC Citationn.d.). Driven by EU policymakers and funding councils (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017), it encourages scientists and innovators to take ‘care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1570). As opposed to RRI being someone else's problem (Felt, Fochler, and Sigl Citation2018, 202) the cards and board support RRI by anticipating ethical issues, encouraging reflection on their implications, prompting responses, and mandating action (by asking questions of technologists that require them to formulate practical responses and plans).

In further understanding how technologists can respond to ethical requirements, we needed deeper insights from a technology design community. We looked to Human Computer Interaction, finding a body of work engaging with normative issues in design (Shneiderman Citation1990). For example, Flanagan, Howe, and Nissenbaum (Citation2008) note there are challenges of terminology and methodologies where

even conscientious designers, by which we mean those who support the principle of integrating values into systems and devices, will not find it easy to apply standard design methodologies, honed for the purpose of meeting functional requirements, to the unfamiliar turf of values. (323)

Lazar et al. (Citation2012) mirror these concerns. Value Sensitive Design (Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2008) and reflective design influenced our cards in finding practical routes forward to support technologists thinking about values in design. With the latter, designers need to consider their role and impacts on users to ‘bring unconscious aspects of experience to conscious awareness, thereby making them available for conscious choice’ by highlighting and questioning assumptions, ideologies, and beliefs of design (Sengers, Boehner, and Kaye Citation2005, 50). This includes reflecting on their position, knowledge and impact on users (Grimpe, Hartswood, and Jirotka Citation2014). Our cards support this process of reflection by asking probing questions that prompt answers and action. We build from Nissenbaum’s (Citation2001) point that ‘systems and devices will embody values whether or not we intend or want them to. Ignoring values risks surrendering the determination of this important dimension to chance or some other force’ (119). Having mapped out how different disciplines have informed our cards and board, we now briefly discuss background ethical design tools and explore why we chose cards.

The Moral-IT Deck approach

There have been numerous attempts to support virtuous behaviour by technologists (Volkman Citation2018) with work from the ACM, British Computer Society (BCS Citation2020), IEEE and many other industry, third sector and governmental stakeholders (Field and Nagy Citation2019). To provide context, is a (non-exhaustive) list of tools that use different mechanisms to support development of ethical systems. For example, codes of conduct provide high level principles that an organisation requires adherence to. Similarly, a standard provides a mechanism to operationalise ethical design at scale, often regionally or globally. Our cards align with the overarching motivations of many of these existing tools, namely to practically support technologists to be aware of and address their ethical responsibilities. We reassert that the novelty of our approach to ‘ethics by design’ is providing the combination of a creative, reflective, physical artefact (the cards) with an accessible, collaborative process for mapping out a plan of action early in the design stage (the board). We now unpack the question of ‘why cards?’ and ‘why an impact assessment board?’’ as key elements of our approach.

Table 1. Example ethics tools.

Why a deck of cards?

In part, these cards build on one author's experiences with card-based tools, particularly for data protection governance (Luger et al. Citation2015). However, card-based tools have a history in design and computing going back to early uses by Neilsen (Citation1995) and Muller (Citation2001), so it is valuable to contextualise the value of cards as a research tool more widely.

In unpacking the value of cards, Roy and Warren (Citation2019) reviewed the use of cards in design research and found that they had been used to serve a variety of purposes. Focusing on the subject matter and content of the cards, this includes (p137):

‘creative thinking and problem solving’

‘systematic design methods’

‘human centred design’

‘domain specific design’

‘futures thinking’

‘collaborative working’

Felt, Fochler, and Sigl (Citation2018) examine how cards function and state that their IMAGINE RRI cards provide a ‘narrative infrastructure’ as a tool to help discuss issues around RRI (203), i.e. to ‘stimulate researchers’ capacity to reflect on the social and ethical aspects of their work and can be applied and adapted relatively widely with limited effort.’ (205). Similarly, Luger et al. (Citation2015) found their ‘privacy by design ideation cards’ helped designers engage with data protection law and challenge the idea that law is something remote to their role and only for specialists. Instead, the cards showed designers how to have a regulatory role and the value of tools that support engagement in a creative manner.

Roy and Warren (Citation2019) document the key strengths of card-based tools as providing clear information delivery and enabling communication. Other studies (e.g. Carneiro, Barros, and Costa Citation2012; Casais, Mugge, and Desmet Citation2016) show this is enabled through cards providing a summarised format for information presentation, the physical nature of cards, and their ability to consolidate ideas in novel ways. Cards can structure discussion (Sutton Citation2011; Hornecker Citation2010), whilst also playing a role in unpacking issues through channelling attention and enabling tangible uses such as ranking/ordering/classifying (Kitzinger Citation1994). Card-based tools are not perfect however, with issues including; providing ‘too much’ or ‘oversimplified’ information, being difficult for users to use, and the lack of scope to change/update the physical cards (Roy and Warren Citation2019, 131).

Our analysis showed longstanding assertions that playful, game-like tools are valuable as ‘having objects at hand to play with is important as it speeds up the process and help participants to focus. As design material game pieces and props create a common ground that everybody can relate to and at the same time they act as ‘things-to-think-with’ (Papert Citation1980; Brandt and Messeter Citation2004, 129). Cards also act as physical anchors for discussion where they ‘afford actions such as pointing, grabbing, grouping, and sorting. Cards support participants in externalizing design rationale and analysis, thus making ideas more concrete and accessible to themselves and to their partners’ (Deng, Antle, and Neustaedter Citation2014, 8). We draw on and further develop this notion of cards as anchors throughout this article.

Whilst literature points to the novelty and utility of card-based tools, there is little consideration paid to what cards are as a medium, with more attention being paid to their content. One exception is Altice (Citation2016) who surveys cards in games to identify five common characteristics that make up playing cards as a ‘platform’. He contends that cards are:

Planar – they are two dimensional and lay flat,

Uniform – in size and shape,

Ordinal – in terms of having order and ranking between card,

Spatial – where the layout and interaction with them in space is significant

Textural – Optimised for handling and touch and ‘hands’ to interact with and enable other characteristics.

Much of the appeal of card-based tools appears to draw from the familiarity with these aspects, which in turn are drawn from card games (an aesthetic we played with in our study). These characteristics suggest why cards differ from simple pieces of paper, post-its or information being delivered and manipulated in a different media. Indeed, there has been a range of card-based tools developed over the years, as documents. We provide this as an illustrative, but non-exhaustive list, to further situate our cards in the wider field. They are often given different names, e.g. ideation (Golembewski and Selby Citation2010), method (IDEO Citation2003), pattern (Wetzel Citation2014), or envisioning (Friedman and Hendry Citation2012) cards.

Table 2. Example decks of cards.

This survey of the nature of cards and card-based tools shows that a set of physical cards are well suited for being an adaptable ethics by design tool. Drawing on the familiarity of cards, as game tools and more widely, the tool can be more immediately understandable and engaging. More importantly, this enables users to grasp (both physically and mentally) the medium of cards themselves, and devote their attention to consideration of their content. This avoids the distraction of users undergoing any period of familiarisation with the tool and its rules of use, which may divert from the objective of facilitating engagement with ethical considerations. We return to participant perspectives on the value of cards in our findings, but now we turn to discuss in more detail on our creation of the Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board.

Why an impact assessment board?

In order to test and evaluate the cards in our workshops we developed a complementary mechanism to support use of the Moral-IT Deck. We created a streamlined ‘impact assessment’ to structure collaborative discussion, keep the discussion focused on distinct steps, and to help the team develop a plan of action that builds on their reflective engagement with the cards. The board helps to visualise and map discussions, enabling collective discussion and deliberation on how to act, and address ethical challenges in a targeted manner. In part, by constraining the deliberation process to specific steps, it ensures that discussions of ethics remain bounded, reducing scope for users feeling overloaded by the diversity of issues they need to engage with. Also, the board is reusable to enable the team to work through risks one at a time, reusing cards in different ways to develop a range of strategies to address the range of challenges faced. Our Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board identifies 4 key stages pertinent to ‘ethics by design’ namely: identifying possible risks; assessing significance or importance of the risk and its likelihood of occurring; establishing suitable safeguards to these risks; and exploring practical implementation challenges. This process helps to plan the safeguards that might be appropriate, and challenges that need to be overcome to implement them.

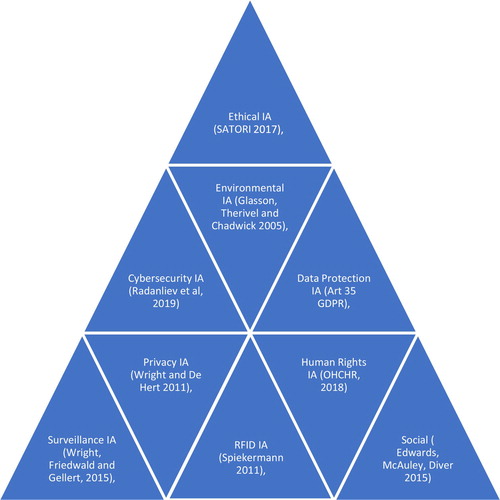

Impact assessments for new technologies are a popular tool in forecasting issues and designing strategies for action in a structured manner. For example, a privacy impact assessment is a ‘systematic process for evaluating the potential effects on privacy of a project, initiative or proposed system or scheme and finding ways to mitigate or avoid any adverse effects’ (Wright Citation2011). shows a variety of IAs we were inspired by in this work.

Impact assessments have uses in a variety of domains and despite benefits, they can be very resource and time intensive (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2015). We were particularly concerned that individuals and organisations sometimes lack the resources or motivation to engage with ethical issues in the first place, and thus a more streamlined tool could help. Technology SMEsFootnote2 and start-ups face difficulties in dealing with legal/ethical concerns (Norval et al. Citation2019) and there is value in low-cost card-based tools to support them (Urquhart Citation2016, Citation2020). We need to learn from criticisms against older impact assessments and similar processes, e.g. constructive technology assessment (Rip and Te Kulve Citation2008) that they can be time intensive and do not always generate wider solutions (Felt, Fochler, and Sigl Citation2018). Furthermore, there are concerns from the wider RRI and technology ethics communityFootnote3 around the need to capitalise on researcher knowledge (as opposed to just ethicists) (Brey Citation2000). There is a need to foreground their perspectives in ethical deliberations (Le Dantec, Poole, and Wyche Citation2009, 1141; Borning and Muller Citation2012, 1125; Reijers et al. Citation2018, 1455). Reijers et al, for example, state that tools for ‘ethical technology design should focus more on the integration of ethics in the day to day work of R and I Practitioners … ’ (Reijers et al. Citation2018, 1457). Similarly, Felt, Fochler, and Sigl (Citation2018) have argued for the need to include researchers in a collaborative arrangement, not outsourcing to them at convenient times in the project and avoiding a ‘new bureaucracy of virtue’ with RRI as series of tick box exercises (Felt, Fochler, and Sigl Citation2018, 202). Considering both the value and critique of impact assessments, we saw the value in testing the cards with an impact assessment but in a quicker, more flexible and accessible manner that could be integrated into the day to day work of technology development. We designed the Moral-IT Deck and Board as amenable to integration with technologists’ working practices without stopping them ‘getting on’ with the doing of the research and development. We now turn to the cards, before examining how they were used in our workshops through discussion of our findings.

Introducing the Moral-IT Deck

Card content

As a design probe (Sharp, Rogers, and Preece Citation2019; Wallace et al. Citation2013)Footnote4 the cards provoke discussion around practical ethical questions at early stages of the design process. They are inspired by Verbeek's argument that ethical decisions are mediated and answered through design practice (Verbeek Citation2005). For engineers and designers, ethical dilemmas and resolutions occur at a grounded, practical level (Millar Citation2014; Verbeek Citation2006), and we were interested in observing those deliberations, as opposed to focusing on formulating more abstract, absolute framings of ethical practice (as codes of ethics often do). As mentioned, the cards provide an anchor to consider ‘ethical’ issues (broadly framed) and think about what ‘ought’ to be done to design more responsible systems.

contains our overview of the Moral-IT deck.Footnote5 We do not claim the ethical groupings or issues on these cards are exhaustive or definitive (if that can ever be claimed) and instead these are starting points for discussion. The cards reflect the authors’ multidisciplinary training primarily in computing, technology law, human computer interaction, STS and critical theory. We also provided blank cards within the deck so participants could add their own or flag any missing concepts, in itself helping us test the robustness of our suggestions. For example, whilst consent is contained within cards such as ‘Special Categories of Data’, some participants wanted a specific ‘consent’ card or one for ‘data misuse’. If recurrent issues keep arising then this would indicate that a specific new card may need to be added to the deck. We also have a series of ‘narrative’ cards which are an alternative mechanism to the Board for using cards. These are valuable when hypothetical scenarios are needed, users are doing the activity independently or looking for a shorter approach, e.g. in teaching. The narrative cards require users to construct a technology scenario and assess its risks using cards. We do not provide analysis on them here, focusing instead on ‘real life’ examples and the process Board, but see for reference to narrative card content.

Table 3. List of Moral-IT cards.

In part, the breadth of issues covered is inspired by Moor's framing of computer ethics as questioning ‘the nature and social impact of computer technology and the corresponding formulation and justification of policies for the ethical use of such technology’ (Moor Citation1985, 266). Many issues can come under the remit of IT ethics and the cards sensitise technologists to a variety of ethical issues to encourage critical discussions and ultimately help develop a questioning mindset. We are also sensitive to criticisms faced by Friedman, Kahn, and Borning (Citation2008) in their envisioning cards and value sensitive design work. Le Dantec, Poole, and Wyche (Citation2009) and Borning and Muller (Citation2012) questioned how they formulated their ‘values with ethical import’, i.e. ‘what a person or group of people consider important in life’ (70). Valid critiques of whose perspectives are around what is being prioritised and why, with one angle stating they prioritise Western democratic ‘liberal’ values such as privacy, justice, autonomy for example. The values in our cards are not to be seen as an exclusive or absolute list of principles. They are a mechanism to begin a conversation and to then critique if these are indeed the right values both for the cards, or for the technology being considered. As they use questions, the responses to those act as a starting point for further reflection on the merits of the value. The open questions can be tested, rejected, replaced or refined by the groups – they are not static or immutable, even if the medium (e.g. cards) make this appear to be the case. As we shall see, there is interpretive flexibility of the cards, borne out in the workshops. Using them as a probe, we were able to test them with different groups and obtain their feedback. We clustered our principles under suits of security, ethics, privacy and law (see table above), and these suits capture many of the legal, ethical and social concepts we deem important when designing (information) technologies. Below we unpack the rationale behind one card, as an example of the thought process which underpins the design and creation of each card in the deck.

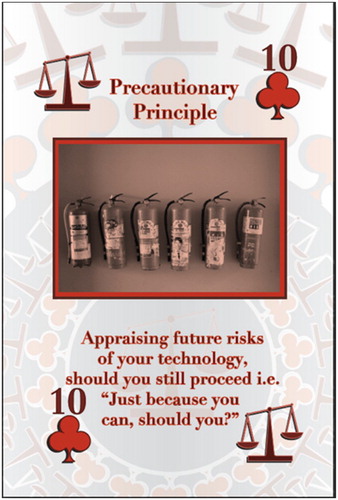

Adopting the precautionary principle () is often both legal and ethical best practice when uncertainty persists around risks from a new technology (Fisher, Jones, and Schomberg Citation2006). It is particularly popular in Europe where ‘command and control’, state led regulation of emerging technologies often takes precedence. Data protection laws for IT, labelling rules for nanotech and limitations on biotech all shape emergence of new innovations. (European Commission Citation2017; EDPB Citation2019) In environmental law specifically, the precautionary principle is prescriptive around preventing harm from pollution or environmental disaster (UN Citation1992). This principle also aligns with more anticipatory forms of governance which seek to guard against future harms and intersects with RRI concepts of stewardship and anticipation.

Card Style: We developed a traditional ‘playing card’ deck style to embrace a game orientated aestheticFootnote6, but also to constrain the number of substantive cards (52) and to force us to formulate 4 suits to cluster our ethical questions. The card text was designed to be provocative and the use of a direct but open question was intended to ensure that the principle could not be dismissed easily, instead requiring an explanation to be formulated to promote engagement. The openness also enabled conceiving of the card flexibly, for example as both a risk and safeguard, e.g. a risk of trustworthiness could be a safeguard for meaningful transparency. Our questions are focused on ‘technology’, as opposed to just ‘computing’ or ‘systems’, to broaden utility.Footnote7 We designed playful suit markers alongside traditional club, heart, diamonds and spadesFootnote8 with a padlock for security; eye for privacy; scales of justice for law; and a globe for ethics. With our 4 Ace cards, inspired by Eno and Schmidt’s (Citation1975) ‘oblique strategy’ card work, we posed some more abstract, provocative questions, e.g. ‘what is the most embarrassing thing about your technology?’ Images are important in card design, for triggering thought processes or emotional reactions, in addition to aesthetic reasons (Friedman and Hendry Citation2012). We chose the images to illustrate the principles in a variety of literal or abstract ways, which was intended to provoke questioning and reflection and promote discussion. We also chose imagesFootnote9 to enable machine readability of cards for future compatibility with a related project, the Cardographer augmented reality platform that tracks use of physical card decks (Darzentas et al. Citation2019). This addresses a limitation of card based approaches. A mobile application or a website has digital modularity which enables easier updating (especially when dealing with normative frameworks like law and ethics where values shift). In contrast, once text is committed to the cards, and printed, it is harder to change these (although workarounds such as blank cards, stickers or writing on them in pen or adding booster decks)Footnote10 The compatibility with Cardographer gives us greater flexibility to add digital information and enabling at a distance workshops, e.g. during the global Covid-19 Pandemic.

Part II: Methodology

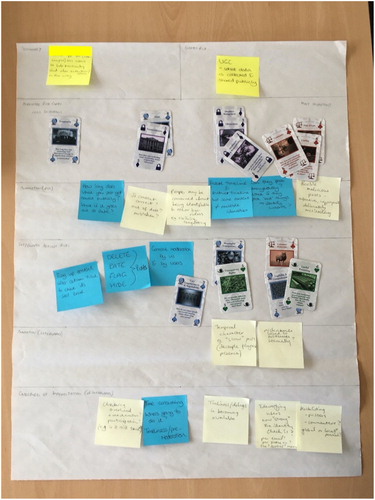

The cards were tested in a series of workshops with 5 groups, lasting an average of 2.5 h. 4 groups were working on the development of technology in a research setting; 1 group broadly worked in software and technology development in industry. Group demographics are summarised in . Whilst there were pre and post workshop questionnaires conducted, we focus on qualitative data from our groups using cards with the impact assessment board in a systematic manner, with a completed board provided below in . This provides a useful material artefact, making ethical deliberations visible, and demonstrates some of the card use practices, e.g. clustering, ranking.Footnote11 We will present other snapshots of boards in subsequent sections. The cards that were used by each of the groups and their order of ranking can be seen in . Participants followed this sequenceFootnote12:

Defining the technology – Summarising what their technology was and writing this on a post-it note at the top left of the physical impact assessment board. This could be a real or hypothetical system (depending on the group).

Defining the main ethical risk – Providing an overall ethical risk for their technology. Whilst multiple risks exist, choosing an overarching one helped focus discussion. This was written on a post-it note and placed on the top right.

Associated risks – They were advised to pick their most important 5 cardsFootnote13 from the Moral-IT deck that they felt were most associated with their overall ethical risk. The decision-making process was not prescribed and left to the group to decide.

Ranking – The groups were then asked to rank and arrange these (5) cards they had selected from least important (on the left) to most important (on the right) and place them in the row provided on the process board. ()

Annotating Risks – Participants were asked to annotate some of the reasoning behind their choice of cards on post-it notes and sticking these directly below the chosen card on the line marked annotations.

Safeguards – On the next line of the process board the participants were asked to use the cards to identify principles as safeguards that may mitigate the risks that they had identified and place them directly below the relevant risk on the line below. They were also encouraged to use post-it notes for this purpose if they did not think that any of the cards were suitable.

Annotating Safeguards – as previously the participants were encouraged to record the reasons for selecting certain card(s) as mitigations on post-it notes and place this on the line below.

Challenges of Implementation – Participants were asked to consider and document what practical elements might challenges the implementation of the safeguards e.g. legal/organisational/social/technical barriers and record these on post-it notes on the line below as previously.

Discussion – Groups were encouraged to discuss throughout the exercise with this forming the research data considered here. Following the completion of the IA process open summative discussions were held which included: reflection on the IA process, value of the cards as a reflective tool, substantive ethical questions that arose for their technology, impact on their future work.

Table 4. Table of participants.

These workshops were audio recorded, and IA sheets retained for analysis. The audio was anonymously transcribed, and then the researchers conducted detailed thematic analysis of the transcripts. Following best practice in thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), initial codes were formed inductively and then through reflexive debate and discussion, these were refined into the key themes presented here.

Part III: Results and discussion

A total of 20 participants across 5 workshops participated in the workshops described here (). All of the academic participants in groups IoT, ST, MR, and AC were previously known to each other as they were working together on the development of the technology that was the subject of the discussion in the workshop with these projects the reason for their recruitment. Of the final SD, non-academic group, 2 individuals came from the same organisation with the others from different organisations and they had not met prior to the workshop. At the outset of the workshop they agreed as a group the technology that would be the focus of their discussion. The following sections will discuss the value of our cards as a tool, their impact on the technology design and how they structure ethical reflection practices.

Cards as a tool

There was flexibility shown in how the cards enabled discussion, within the domain of the IA process. We observed three approaches for how participants selected cards as their ethical risks, which we frame as: ethical clustering, ethical sorting, and ethical replacement. We then explore how the cards had value as anchors for ethical discussion once they were chosen.

Ethical clustering

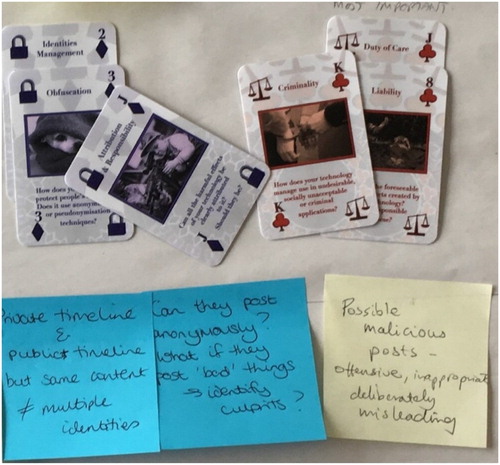

Many participants found sorting the relevant from irrelevant cards initially difficult, as they all could be applied to the technology under consideration to some extent. Utilising the affordance of the cards, we observed some groups doing what we term ‘ethical clustering’. Groups would cluster the cards together and construct associated risks as clusters of cards rather than individual principles. The combination of cards enabled more nuanced understandings of different aspects of risk approached through card combinations. We can see this in where linked issues around liability also tie into criminality and duty of care; or in thinking about identities management, they recognise the importance of both obfuscation strategies and that there are parties responsible for doing this. The importance of the physical arrangement of the cards is shown here () with the Attribution and Responsibility card serving to bridge between the two other clusters of cards.

One participant documented their team's choices and clusters, with card choices including obfuscation, identities management, secrecy, data breach management, and confidentiality as shown in the quote below.

I think most of mine are based on identity because our system requires users to essentially self-identify. So, we’ve got, for obfuscation how does your technology protect peoples’ identities? Does it anonymise or use anything like that? Identities management, does your technology enable systems to hold and manage more identities? Secrecy, does your technology keep secrets? That's kind of the same thing. Data breach management. I guess it is kind of separate. It's more about how securely and everything is stored. And confidentiality is kind of the same thing. Group MR

Ethical sorting

Are we going by suit or are we going by shuffling and dealing them out? . ..I’d say we shuffle them up. Group SD

PA3 – I don't know. I think we’ve ended up with just too many cards. We’ve got to narrow these down to five. I guess we just go through what we’ve got, right?

PA4 – Yes, and if you’ve got any one that's similar, we can choose between them, can't we?

Group SD

Ethical comparison and replacement

Let me read that one again. I think that probably puts it better than that one. Group SD

PA4 I’ve got data security. Does your technology protect from unanticipated disclosures? I was thinking about it’ll have all sorts of movements and locations and things like that.

PA2 Yes, location privacy.

PA4 Okay, so maybe that's more specific.

PA3 Because that could be a disaster, couldn't it, if you were sharing your family plan in your insurance and it's like, well, what are you doing in this area?

PA2 We don't ask those kinds of questions.

PA4 So is location, is that one more specific? Is that better?

PA1 I think it's a strong one. I think it's a very strong one. It should be, I think.

Anchors – appropriate and inappropriate

Participants sought reference points with which to elucidate, explain and demonstrate their ideas. They drew these reference points from their own experience or from the cards in the workshop and used them to anchor the discussion. Whilst the cards were designed to spark, encourage and structure discussion through their open-ended questions, participants already came to the table with an understanding of the technology, its design and operation. This was now anchored in the ethical principles by the process of sorting and selecting cards. The role of the cards as anchors showed how they were used to complement existing understandings of the system, not reducing or closing off discussion but instead acting as valuable reference points, tying the discussion to principles which made ethical consideration and reflection more tractable, limiting its ability to shift and move. We characterise our cards as providing appropriate anchors for discussion which were in contrast to other inappropriate anchors used by the participants which we discuss below.

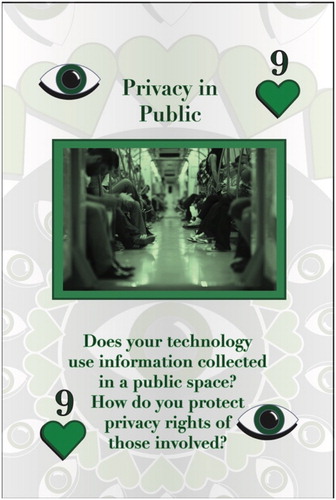

How the cards complemented and acted as anchors for existing knowledge can be seen by the material record of the discussion left on the IA process board. For example, one card had the flexibility to be interpreted and act as an anchor by different groups, for different technologies, in different ways. A good example is the ‘privacy in public’ card (see ) where three groups interpreted it, and used it to anchor their discussion, in different ways:

Group IoT used it to anchor their thinking about the ethical dimensions of consent for storing information collected in public where photographs, video and audio may capture both families and the general public.

This contrasts with Group SD who were talking about tracking for car insurance purposes and were concerned with the data that may be collected in public and how it may be misused for other unintended purposes.

Group MR used the card to anchor their discussions about the potentially public nature of the content associated with a gift and where and to whom this content may be revealed, potentially inappropriately. All three are pertinent ethical issues, and due to their interpretive flexibility, the cards are able to act as appropriate anchors that enable users to draw connections between ethical and legal principles.

In contrast, there can also be pre-existing inappropriate anchors. Here, we saw sensemaking strategies and tacit knowledge shaping ethical rationalising about best practice. This was particularly prominent in reference to large corporations for their good or bad actions, e.g. being a bit ‘Ben and Jerry’ in reference to socially responsible companies or ‘don't be evil’ in relation (albeit sarcastically) to Google's famous moniker. A good example is from Group AC discussing smart speaker data collection, where we see a blend of two notions of ethical good and bad. Amazon is suggested as an example of questionable ethical practice, but the notion of ‘Scout's honour’ could be positive, perhaps hinting that researchers feel they are held to different moral standards (and more trustworthy). What both examples have in common is that they are both anecdotal reference points based on partial considerations of ethics in different contexts. Generalising lessons from such examples to inform consideration of their technology could be seen as inappropriate reference points (anchors) for ethical reflection.

IE2 I’m trying to figure out how Amazon convinced people that Alexa doesn't actually record and is just ephemeral, here and gone. Because really it is sending that whole footprint over, it's not even keeping it there, so, how did they do that?

IE1 Maybe they just don't bother. So, we’re interested in transparency, Amazon aren't.

IE5 So, one of the solutions must be we tell them explicitly, right? So, that is the transparency solution, that doesn't necessarily solve the honest and trust bit, but at least then we’ve told them we’re not storing anything. Honestly. Scout's honour. Group AC

This is similar to the observations of Felt, Fochler and Sigl (Citation2018) who argue that cards provide rhetorical resources and a ‘narrative infrastructure’ to enable individuals to discuss issues that may previously be unfamiliar with. We contend that the Moral-IT cards serve to flexibly structure the discussions that were driven by the knowledge and understanding of the participants. They anchor these disparate interpretations and perspectives in a shared sensemaking experience aided by the cards. This led to improved communication, mutual understanding and a greater grasp on the pragmatic implications of the ethical considerations at hand. When compared to inappropriate anecdotal and partial anchors employed by the participants, the value of this emergent element of the cards is demonstrated. We can begin to understand how, through the cards, discussions are ‘anchored’ and provide insight into how more abstract principles are understood and employed in practice by technology developers.

Cards structuring ethical debate

We will now expand on how we observed cards impacting the ethical debates around design of new systems in more depth. We focus here on 3 key observations: (1) the cards levelled the playing field between participants in terms of ethical knowledge and engagement with discussions (2) that the cards provide insights into how participants view ethics, something we frame as ‘intertwined ethics’ (3) How the starting point for ethical discussions is significant and how the cards impact this.

Levelling the playing field on ethics

As we have seen, the Moral-IT cards structure discussion through the sorting, turn taking and negotiation process. We observed that this approach means each member of the group is enabled to participate, regardless of their knowledge, expertise and seniority within the group. The cards ask open questions and treat everyone equally in the face of the question, prompting an answer about how ‘your’ technology deals with this issue. This requires deliberation both as an individual and a group, encouraging an individual response to be generated which could then be shared with the group to start or continue the discussion. Furthermore, due to the collaborative structure of the impact assessment board, no single person has privileged access to all cards. They need to understand the other principles through listening to and negotiating with the others who have other cards, as this exchange below referring to a negotiation between the use of the bias and prejudice and autonomy cards, shows.

PA4 I feel like the bias is … I still think that's high, very high.

PA2 One group of people differently versus there's the autonomy we’ve got on top.

PA1 Those are two different ways of looking at the same thing. It's like autonomy is I decide where I’m going or what I’m doing, when I’m doing it. Bias and prejudice is the organisation that's providing my choice, deciding I’m allowed to do things or the groups of people are allowed to do.

PA4 And I feel like that is in ethical terms the worst.

PA1 I think she's trumped us.

PA2 I’m willing to yield. [Unclear].

PA3 Yes.

Group SD

We also observed the cards made ethical reflection less daunting by deferring responsibility for the judgement and questioning to the card itself and its authority. This enabled participants to put opinions across, not as their own ungrounded view, but instead supported by the card which mandated a response. The cards can empower participants to deliberate on ethics of technology (even if this is new territory for them) by providing valuable, provocative, discursive resources and a structured process of use.

Intertwined ethics

The cards produced insights into how the ethics of technology was viewed by the participants, something we call ‘intertwined ethics’. This includes discussion of elements such as their values as developers and designers, the rules or laws they had to follow, and their concern with the consequences of their technology and how others may use it. They were concerned with a wide range of ethical dimensions from managing their own intentions as developers, doing the ‘right thing’ and managing consequences of their technology being used in both intended and unintended ways. These elements all emerged in quick succession ‘intertwined’ with one another to such an extent that one particular perspective (e.g. a virtue or consequentialist perspective) could not be extracted as a dominant mode of assessing or designing an ethical system. For example, Group SD discussed if they make effort to build an ethical ML system, they have limited capacity as author to stop someone (mis)appropriating it.

It is that standing on the shoulder of a giant thing a little bit. I might write some software from a completely ethical point of view, what can I do to make sure that people who use my software use it in an ethical way? What I had in mind for it might not be what somebody sees and go, I know what I can use that for. So, if I write a nice little machine learning system, somebody can take that and do things that I wouldn't be agreeable to as the author. Group SD

Examples of how participants were concerned with the consequences and use of their technology included Group MR concerned about how their mixed reality technology could be misused by attaching unwelcome digital content (e.g. an embarrassing song)

it can be that they open it in a public space and something which they didn't intend to reveal, like them singing a song which they might feel they wouldn't want to happen in a public space, it will embarrass them leaking out in public … Group MR

“Is it fair then to say that one of our primary risks is actually gaining people's trust/understanding about what this is all about. Just the getting over misconceptions.” … “My own version of risk would be people not understanding the system and thinking that we’re doing all kinds of mean things with their data. Basically, them not necessarily trusting that we’re not using their data.” Group AC

Importance of the starting point

Of central importance to the intertwined considerations was the ethical starting point of the discussion. This showed how vital the context in which the developers were working is. The groups’ judgement of their own ethical position or status or how they may be constrained by the business priorities or legal context of their work all served to shape the following discussions. Whilst this element emerged through the workshop exercise, it was revealed as prior and foundational to the discussion, but also vital. For example, a business in a competitive marketplace may have less ability to develop ethical technology if it would impact the company's profitability. A group of technology developers who believe they are inherently ‘good’ people may also not be able to appreciate or engage with potential negative aspects of their work. Where the developers are starting from in terms of constraints and attitude is therefore a vital consideration in enabling the design of ethical technology.

As noted above, Group AC shaped their discussion around the communication of the operation of their technology, partly as they acknowledged the perception that ‘Computer vision people are not worried about people being creeped out.’ They wanted to set themselves apart from their view of the community through their ‘virtuous’ ethical practice by designing in user privacy and control from the start. Their discussion then focused on how to communicate with the user about how the system operates, in contrast to their view of the computer vision community who were not worried about ‘creeping people out’. From such a starting point, the challenge was one of communication in addition to the development of the system itself.

A similar starting point was shown in other groups who insisted that they were ‘good boys’ or perhaps tongue in cheek saying ‘Scouts Honour’. This appeared to signify a recognition that such assurances of good intentions and virtue have to be taken on faith as there was no guarantees when faced with the pragmatic reality of the constraints and expectations in which the technology operates.

Our commercial group SD highlighted that for them, ethics were secondary to legal constraints as the starting point for what a company was allowed and not allowed to do. As one participant stated ‘So where I’ve worked in ethics before we usually start with the law, then we work down to policy and then you work down to the cases covering them. So, it’s like a hierarchy, it goes … down from law.’ The priority of the financial bottom line and the law contrasts with concerns our academic technology developers raise, who are less sensitised to the practical necessity of making a profitable product and profitable company. This suggests that ethics by design tools need to align with and ideally enhance the business practices of a company. For our group they also raised the fact that not all businesses begin from the same starting point, and indeed may use differences as their competitive advantage. They were concerned with how to resolve the tension that if they took measures to ensure ethical practice, as a responsible company, that there would be potential for a disruptive competitor to undercut them by not incurring any cost of producing more ethical technology. As they state

just because you can do something doesn't mean you should do it, but there will always be somebody who is willing to do it. And that's a worry because they can come in and they have access to exactly the same markets and might not be as scrupulous as we are.

Potential impact of the Moral-IT cards on technology design

In thinking about ethics by design, we conclude by discussing how the cards structured our participants thinking around technical design choices, and we do this with one detailed example from Group AC. They focused on the challenge of communicating how their system worked. They sought appropriate metaphors to demonstrate what data it collected and how this was stored, shared and deleted under user control. Whilst these measures speak to a number of ethical principles represented on the cards such as transparency and user control, the discussion went onto highlight how the method of conveying the operation of the system could be considered to be ethically problematic in itself.

So, to sum that up, I’ve written visualisation as a challenge of implementation. Which is essentially it, isn't it? And is it a visualisation as something that represents what's happening or is it a view onto actually what is happening, is the challenge there. I don't know if it was a thing or just a design, the USB stick that swelled up as it became full of data, and you plug it in and it's slim because it's empty and as you put files on it, it goes …

So, that's clearly not a reality, it's a visual trick.

So, do we need something like that, water, liquid, or is it somehow you the actual process at work because it's transparent? We’re not facilitating this.

Group AC

The group did not reach a conclusion as to what constituted an appropriate explanation of how a system worked but the discussion raised the pragmatic issue that ethical practice, in this example, attempts to explain a system were hindered by a lack of an appropriate method. Metaphors of demonstration such as filling and emptying may be appropriate for mechanical systems, but they were not deemed to be for a computational system. Cards like meaningful transparency can start a discussion, which is valuable, but that does not mean the cards will provide the solution. As a reflective tool, there is still significant value in provoking these discussions and thinking about what it means for technology design. It involves critique of the appropriateness of the language used to discuss it, the expectations this can raise, and how this may impact its operation. This is just one example of how the cards surfaced issues and prompted consideration which could then influence design decisions of technology. Without such a probe and process these issues would likely remain unconsidered, pointing to how the cards work towards the goal of ‘ethics by design’.

Part IV: Conclusions

This paper has documented the rationale, development process, and substantive detail on a new ethics by design tool: The Moral-IT Deck and Moral-IT Impact Assessment Board. It has also provided insights into how this tool works in practice, documenting key empirical findings and insights into doing ethics by design in practice using the cards. We conclude by pulling out some key takeaway findings from the development, evaluation and testing of this design probe.

The cards embed thinking about ethical issues in design, as opposed to moving this to external, outside assessment from ethicists or social scientists. They require technologists to reflect on and take responsibility for their design choices. Furthermore, the board enabled structured, rich reflection on the issues and proved a valuable tool for making the subject matter more accessible to technologists to plan routes forward. We found it interesting that issues such as temporality emerged as a dimension of responsibility for participants, for example in the IOT Group example of how they’d manage legacy data from the system. The discussion of finding mechanisms to demonstrate how a new technological system works (as opposed to how people think it works), was highlighted in the AC Group. This showed that the cards pose questions that enable reflection on topics such as system legibility and appropriate metaphors. However, there remains a lot of work to find strategies that best answer the quandaries posed.

Cards are a valuable medium for communicating complex ideas and structuring practical discussions. We observed the physicality of cards is valuable for enabling ethical clustering; sorting; and comparison, making ethical deliberations material, the choreography of their use to use in the words of Felt et al. (Citation2014). That physicality can be a weakness too, as once cards are printed, they can be harder to change and it is time consuming to create such a high-fidelity physical prototype. They provide appropriate anchoring points of discussion, and help navigate what may be inappropriate tacit anchors too. Importantly, for group deliberations, they help to level the playing field and enable collaborative deliberation on ethics in a way similar to that found by Felt et al. (Citation2014) where cards replaced expert voices but contained expert knowledge increasing the confidence of participants to feel competent to deal with issues, in our case the ethical consideration of technology. This corresponds with Felt, Fochler, and Sigl (Citation2018) observation of how ‘unavoidable hierarchies … are, in our experience strongly moderated by the card-based format.’ (213) or Brey’s (Citation2017) desire for ‘serious moral deliberation under conditions of equality’. We argue collaborative card-based methods can serve to democratise ethical deliberation and discussion processes. We also found that our cards showed how ethical frameworks in design are intertwined in practice, and not neatly separated into distinct forms. On one side, we observed participants acting virtuously by going through the IA process, but also raised concerns about consequences over time and impact of their work. Beyond the practicalities, we received feedback that the medium and aesthetic is viewed as fun.

For example, a participant from Group SA stated

I think it's fascinating these cards because I’ve been doing software forever and we generally get these things applied retrospectively … It can be you were sitting around with the development team and you’re like, okay, we’re going to have a session this afternoon, we’re going to bring these cards in and before you’d even start on the system you’re going over these things and you’re building in from the get go. I can just see how great it is.

Acknowledgements

Funded by EPSRC Grant EP/M02315X/1. We also want to thank Dr Dimitrios Darzentas for his contribution to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lachlan D. Urquhart

Dr Lachlan D. Urquhart is a Lecturer in Technology Law at the University of Edinburgh and Visiting Researcher at Horizon Digital Economy Research Institute, University of Nottingham. He has a multidisciplinary background in computer science (PhD) and law (LL.B; LL.M). He has published over thirty papers across computing and law venues. His main research interests are in human computer interaction, ubiquitous computing, data protection, computer ethics and cybersecurity. He has been Co-I on funded projects totalling over £5m from EPSRC, ESRC, AHRC, Universitas 21, Impact Accelerator Funds, and Research Priority Funds. This includes projects on regulating trustworthy autonomous systems, building more secure smart homes, and examining ethical aspects of Emotional AI in smart cities in Japan and the UK. See https://lachlansresearch.com/ for more information.

Peter J. Craigon

Dr Peter J. Craigon is a Research Fellow in Ethics, Legislation and Engagement in Food and Agricultural Innovation within the Future Food Beacon of Excellence at the University of Nottingham. He is working on developing tools to encourage ethical engagement and regulatory responsiveness for researchers working in food and agricultural innovation and beyond. He previously worked at the Horizon Digital Economy Research Institute at the University of Nottingham developing tools to enable ethical design of IT based technologies and also at the University of Nottingham School of Veterinary Medicine and Science researching dog behaviour, particularly guide dogs.

Notes

1 We follow Verbeek’s (Citation2006) framing of ethics as a question of ‘how to act’, and the importance of technology design in giving material answers to how to act. Our cards help designers assess ethical impacts of their system and how they can mediate lives of users. As Verbeek states:

There are two possible ways to take technological mediation into account during the design process. A first, minimal option is that designers try to assess whether the product they are designing will have undesirable mediating capacities. A second possibility goes much further: designers could also explicitly try to build in specific forms of mediation, which are considered desirable. Morality then, in a sense, becomes part of the functionality of the product’ (368)

2 Small and Medium Sized Enterprises.

3 As Felt, Fochler, and Sigl (Citation2018) state

any successful RRI activity must find a way of making RRI a core element in research practice, despite competing values. If this can be achieved, RRI related work potentially play the role of a ‘moral glue that holds the often simultaneous yet potentially contradictory promises of economic, societal and scientific benefits together

4 Sharp, Rogers, and Preece (Citation2019, 399) where they state ‘design probes are objects whose form relates specifically to a particular question and context. They are intended to gently encourage users to engage with and answer the question in their own context’.

5 See full deck available here too online, as downloadable PDF – https://lachlansresearch.com/the-moral-it-legal-it-decks/

6 In past research with cards, we often found researchers wanted thought they were a game, hence with this deck we adopted this aesthetic.

7 NB they were designed in a computing context, used in workshops with projects utilising embedded sensors, affect sensing, location tracking, tangible and mobile computing, mixed media repositories etc.

8 Retaining these enables gameplay with cards as traditional decks.

9 We used contextually appropriate images from Pixabay (for intellectual property reasons) and matched these to the text.

10 We had blank cards in our deck.

11 Such artefacts would be a useful ongoing record and working document that groups could refer to, update and amend as they progressed through the development of their technology, much like a privacy impact assessment can be an organic document.

12 This sequence of steps can be seen as the ‘rules’ for completing the impact assessment that the participants followed. This was presented to them, with a worked example at the outset of the workshops, with the authors present to facilitate the discussion and process. In non-facilitated sessions such processes would need to be formalised into a rulebook of suggested use processes and scenarios, so users can select one as a starting point according to their needs. We would recommend that such ‘rules’ are seen as a starting point and are interpreted flexibly so as to make the cards as useful as possible across contexts and stages of the design process. The development and testing of such use processes is the subject of ongoing and future work.

13 This was a guide and not a prescribed figure, some clustered more cards under 5 themes, some picked less as we see in the results.

14 Due to Covid-19, we are unable to get further data at this time, as this data physically held at University, for anonymity purposes.

References

- ACM. 2018. “ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.” https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics.

- Akrich, M. 1992. “The De-scription of Technological Objects.” In Shaping Technology / Building Society, edited by W. E. Bijker, and J. Law, 205–224. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Altice, N. 2016. The Playing Card Platform in Analog Game Studies: Volume 1 2016 http://analoggamestudies.org/2014/11/the-playing-card-platform/.

- Astrachan, O. “Bubble Sort: An Archaeological Algorithmic Analysis.” Accessed June 2020. https://users.cs.duke.edu/~ola/bubble/bubble.html.

- Barnard Wills, D. 2012. Privacy Game, VOME at http://vome.org.uk/2012/05/03/privacy-game-now-available-todownload-under-a-creative-commons-license/.

- BCS The Chartered Institute for IT. 2020. “Code of Conduct for BCS Members.” https://www.bcs.org/media/2211/bcs-code-of-conduct.pdf.

- Belman, J., et al. 2011. “Grow A Game: A Tool for Values Conscious Design and Analysis of Digital Games.” DIGRA ‘11. Think Design Play at http://www.tiltfactor.org/wp-content/uploads2/Digra2011-GrowAGameTool-BelmanNissenbaumFlanaganDiamond.pdf.

- Belmont Report. 1979. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research (1979) “The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research.” https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html.

- Borning, A., and M. Muller. 2012. “Next Steps for Value Sensitive Design.” Proceedings SIGCHI Conference Human Factors in Computer Systems (CHI’12), 1125–1134. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Brandt, E., and J. Messeter. 2004. “Facilitating Collaboration Through Design Games.” In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Participatory Design: Artful Integration: Interweaving Media, Materials and Practices – Volume 1 (PDC 04), 121–131. doi:10.1145/1011870.1011885.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brey, P. 2000. “Disclosive Computer Ethics; The Exposure and Evaluation of Embedded Normativity in Computer Technology.” ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society 30 (4): 10–16.

- Brey, P. 2012. “Anticipatory Ethics for Emerging Technologies.” Nanoethics 6: 1–13. https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/4321-brey-panticipatory-ethics-for-emerging.

- Brey, P. 2017. “Ethics of Emerging Technologies.” In Methods for the Ethics of Technology, edited by S. O. Hansson. Rowman and Littlefield International. https://ethicsandtechnology.eu/wp-content/uploads/downloadable-content/Brey-2017-Ethics-Emerging-Tech.pdf.

- Brey, P., et al. 2020. An Ethical Framework for the Development and Use of AI and Robotics Technologies. SIENNA Deliverable 4.7.

- Burget, M., E. Bardone, and M. Pedaste, eds. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19.

- Carneiro, G., G. Barros, and C. Z. Costa. 2012. I0 Cards: A Tool to Support the Design of Interactive Artefacts. DRS 2012 Bangkok.

- Casais, M., R. Mugge, and P. Desmet. 2016. “Using Symbolic Meaning as a Means to Design for Happiness: The Development of a Card Set for Designers.” DRS 2016 Brighton.

- Darzentas, D., R. Velt, R. Wetzel, P. J. Craigon, H. G. Wagner, L. D. Urquhart, and S. Benford. 2019. “Card Mapper: Enabling Data-Driven Reflections on Ideation Cards.” ACM SIGCHI. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3290605.3300801.

- Deng, Y., A. Antle, and C. Neustaedter. 2014. “Tango Cards: A Card-based Design Tool for Informing the Design of Tangible Learning Games.” In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (DIS ‘14), 695–704. doi:10.1145/2598510.2598601.

- Denning, T., B. Friedman, and T. Kono. 2013. The Security Cards: A Security Threat Brainstorming Toolkit at http://securitycards.cs.washington.edu/assets/security-cards-informationsheet.pdf.

- Denning, T., A. Lerner, A. Shostack, and T. Kono. 2013. “Control Alt Hack: The Design and Evaluation of a Card Game for Computer Security Awareness and Education.” In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC conference on Computer & communications security (CCS '13), 915–928. New York: ACM.

- Dignum, V., et al. 2018. “Ethics by Design: Necessity or Curse?” In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES '18), 60–66. New York: ACM.

- Edwards, L., D. McAuley, and L. Diver. 2016. “From Privacy Impact Assessment to Social Impact Assessment.” 2016 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Jose, CA, 2016, 53–57.

- Eno, B., and P. Schmidt. 1975. Oblique Strategies. http://stoney.sb.org/eno/oblique.html.

- EPSRC (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council). n.d. “Framework For Responsible Innovation.” Accessed June 2020. https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/index.cfm/research/framework/.

- European Commission. 2017. The Precautionary Principle: Decision Making Under Uncertainty. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/precautionary_principle_decision_making_under_uncertainty_FB18_en.pdf.

- European Data Protection Board. 2019. “Guidelines 4/2019 on Article 25 Data Protection by Design and Default.” https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/edpb/files/consultation/edpb_guidelines_201904_dataprotection_by_design_and_by_default.pdf.

- Fedosov, A., M. Kitazaki, W. Odom, and M. Langheinrich. 2019. “Sharing Economy Cards.” ACM SIGCHI ‘19. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3290605.3300375.

- Felt, U., M. Fochler, and L. Sigl. 2018. “IMAGINE RRI. A Card-Based Method for Reflecting on Responsibility in Life Science Research.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1080/23299460.2018.1457402.

- Felt, U., S. Schumann, C. G. Schwarz, and M. Strassnig. 2014. “Technology of Imagination: a Card-Based Public Engagement Method for Debating Emerging Technologies.” Qualitative Research 14 (2): 233–251. doi:10.1177/1468794112468468.

- Field, J., and A. Nagy. 2019. Principled Artificial Intelligence: Mapping Consensus in Ethics and Rights Based approaches to Principles for AI. https://cyber.harvard.edu/publication/2020/principled-ai.

- Fisher, E., J. Jones, and R. Schomberg. 2006. Implementing the Precautionary Principle. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fisher, E., R. L. Mahajan, and C. Mitcham. 2006. “Midstream Modulation of Technology: Governance from Within.” Bulletin of Science Technology and Society 26 (6): 485–496.

- Flanagan, M., D. Howe, and H. Nissenbaum. 2008. “Embodying Values in Technology: Theory and Practice.” In Information Technology and Moral Philosophy, edited by J. Van Den Hoven, and J. Weckert, 322–353. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Forsberg, E. M. 2007. “Pluralism, the Ethical Matrix and Coming to Conclusions.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 20: 455–468.

- Friedman, B., and D. Hendry. 2012. “The Envisioning Cards: A Toolkit for Catalyzing Humanistic and Technical Imaginations.” In ACM CHI ‘12, 1145–1149. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2207676.2208562.

- Friedman, B., P. Kahn, and A. Borning. 2008. “Value Sensitive Design and Information Systems.” In The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics, edited by K. Himma, and H. Tavani, 69–101. New York: Wiley and Sons.

- Glasson, J., R. Therivel, and A. Chedwick. 2013. An Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment. Oxford: Routledge.

- Golembewski, M., and M. Selby. 2010. “Ideation Decks: A Card Based Design Ideation Tool.” In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (DIS '10), 89–92. New York: ACM.

- Gotterbarn, D. 1991. “Computer Ethics: Responsibility Regained.” National Forum: The Phi Beta Kappa Journal 71: 26–31.

- Grimpe, B., M. Hartswood, and M. Jirotka. 2014. “Towards a Closer Dialogue Between Policy and Practice: Responsible Design in HCI.” In Proceedings of CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computer Systems, (CHI ‘14.). New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Groves, C. 2017. “Review of RRI Tools Project, Http://www.rri-Tools.eu.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (3): 371–374.

- Hornecker, E. 2010. “Creative Idea Exploration Within the Structure of a Guiding Framework: The Card Brainstorming Game.” In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI ‘10), 101–108. doi:10.1145/1709886.1709905.

- IDEO. 2003. “Method Cards.” https://www.ideo.com/post/method-cards.

- IEEE. 2018. “IEEE Launches Ethics Certification Program for Autonomous and Intelligent Systems.” https://standards.ieee.org/news/2018/ieee-launches-ecpais.html.

- IEEE Ethics in Action. n.d. “IEEE Ethics in Action.” Accessed June 2020. https://ethicsinaction.ieee.org/.

- IEEE Code of Ethics. n.d. “7.8 IEEE Code of Ethics.” Accessed June 2020. https://www.ieee.org/about/corporate/governance/p7-8.html.

- Ikonen, V., et al. 2015. “Human-driven Design of Micro- and Nanotechnology Based Future Sensor Systems.” Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 13 (2): 110–129.

- Innovate UK. 2016. “Horizon Sustainable Economy Cards.” Accessed June 2020. https://www.slideshare.net/WebadminTSB/innovate-uk-horizons-sustainable-economy-framework.

- Kitzinger, J. 1994. “The Methodology of Focus Groups: The Importance of Interaction Between Research Participants.” Sociology of Health and Illness 16 (1): 103–121.

- Know Cards. (2016). “Know Cards.” Accessed June 2020. https://know-cards.myshopify.com/.

- Lane, G., A. Angus, and A. Murdoch. 2018. “UnBias Fairness Toolkit.” https://unbias.wp.horizon.ac.uk/fairness-toolkit/https://zenodo.org/badge/DOI/10.5281/zenodo.2667808.svg.

- Latour, B. 1992. “Where are the Missing Masses? – The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artefacts.” In Shaping Technology / Building Society, edited by W. E. Bijker, and J. Law, 205–224. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Lazar, J., J. Abascal, J. Davis, V. Evers, J. Gulliksen, J. Jorge, T. McEwan, et al. 2012. “HCI Public Policy Activities in 2012: A 10 Country Discussion.” Interactions May/June, 78–81.

- Le Dantec, C., E. Poole, and S. Wyche. 2009. “Values as Lived Experience: Evolving Value Sensitive Design in Support of Value Discovery.” In Proceedings SIGCHI Conference Human Factors in Computer Systems (CHI’09), 1141–1150. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Lucero, A., and J. Arrasvuori. 2010. “PLEX Cards: A Source of Inspiration When Designing for Playfulness.” In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games (Fun and Games '10), 28–37. New York: ACM.

- Luger, E., L. Urquhart, T. Rodden, and M. Golembewski. 2015. “Playing the Legal Card: Using Ideation Cards to Raise Data Protection Issues Within the Design Process.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 457–466. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- McStay, A., and P. Pavliscak. 2019. “Ethical Guidelines for Emotional AI.” https://drive.google.com/file/d/1frAGcvCY_v25V8ylqgPF2brTK9UVj_5Z/view.

- Mepham, B., M. Kaiser, E. Thorstensen, S. Tomkins, and K. Millar. 2006. Ethical Matrix Manual. The Hague: LEI.

- Millar, J. 2008. “Blind Visionaries: A Case for Broadening Engineers’ Ethical Duties.” IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society, ISTAS 2008.

- Millar, J. 2014. “Technology as Moral Proxy: Autonomy and Paternalism by Design.” 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Science, Technology and Engineering, Chicago, IL, 2014, 1–7. doi:10.1109/ETHICS.2014.6893388.

- Moor, J. 1985. “What is Computer Ethics: A Proposed Definition.” Metaphilosophy 16 (4): 266–275.

- Morrison-Saunders, A., A. Bond, J. Pope, and F. Retief. 2015. “Demonstrating the Benefits of Impact Assessment for Proponents.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 33 (2): 108–115. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.981049.

- Muller, M. J. 2001. “Layered Participatory Analysis: New Developments in the CARD Technique.” In CHI 2001 – Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 90–97. doi:10.1145/365024.365054.

- Neilsen, J. 1995. Usability Testing for 1995 Sun Microsystems Website https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-testing-1995-sun-microsystems-website/.

- Nissenbaum, H. 2001. “How Computer Systems Embody Values.” Computer March, 118–120.

- Norval, C., et al. 2019. “Data Protection and Tech Startups: The Need for Attention, Support, and Scrutiny.” Working Paper on SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3398204.

- ODI (Open Data Institute). 2019. “The Data Ethics Canvas.” https://theodi.org/article/data-ethics-canvas/.

- Papert, S. 1980. Mindstorms – Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. New York: Basic Books Inc. Publishers.

- Play Decide. 2018. “Play Decide.” Accessed June 2020. https://playdecide.eu/.

- Radanliev, P., D. De Roure, R. Nicolescu, M. Huth, R. M. Montalvo, S. Cannady, and P. Burnap. 2018. “ Future Developments in Cyber Risk Assessment for the Internet of Things.” Computers in Industry 102: 14–22.

- Reijers, W., D. Wright, P. Brey, K. Weber, R. Rodrigues, D. O’Sullivan, and B. Gordijn. 2018. “Methods for Practising Ethics in Research and Innovation: A Literature Review, Critical Analysis and Recommendations.” Science and Engineering Ethics 24: 1437–1481. doi:10.1007/s11948-017-9961-8.

- Rip, A., and H. Te Kulve. 2008. “Constructive Technology Assessment and the Socio Technical Scenarios.” In Presenting Futures Fisher, Selin. Wetmore Dorecht Springer.

- Roy, R., and J. P. Warren. 2019. “Card-based Design Tools: A Review and Analysis of 155 Card Decks for Designers and Designing.” Design Studies, 125–154. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X19300171.

- Royal Academy of Engineering n.d. “Engineering Ethics.” Accessed June 2020. https://www.raeng.org.uk/policy/supporting-the-profession/engineering-ethics-and-philosophy/ethics.

- RRI Tools. n.d. “RRI Tools.” Accessed June 2020. https://www.rri-tools.eu/about-rri#.

- SATORI. 2017. “Outline of An Ethics Assessment Framework.” Accessed June 2020. https://satoriproject.eu/media/D4.1_Proposal_Ethics_Assessment_Framework.pdf.