ABSTRACT

Responsible research and innovation (RRI) has been the preferred idiom for interrogating the social, ethical and political dimensions of science, technology and innovation for roughly a decade. The uptake of RRI into prominent policy organisations has resulted in a proliferation of policy frameworks as policy makers have attempted to articulate what it means for them to enact RRI. Here, we draw on our experience developing an RRI framework in the ERA Cofund on Biotechnology. We discuss three ways that treating RRI as a form of knowledge production has allowed us to engage with the institutional dimensions of science: as research within scientific projects; as administrative knowledge; and as methodological knowledge. We argue that Science and Technology Studies' concern with knowledge making offers a valuable route to approach RRI within research funding organisations, and reflect on how this approach might be developed in the next European Commission Framework Programme.

For roughly the past decade, and at least from the vantage point of those working in science and technology studies (STS), broad discourses about the need to strengthen the governance of science, technology and innovation have manifested in an idiom of responsible research and innovation (RRI). This term is shorthand for a set of arguments that understand science as a fundamentally social activity, see scientific change and social order as inherently interwoven, and note how few opportunities there are to debate the public value of science within contemporary societies (Felt et al. Citation2007; Macnaghten Citation2020; Wilsdon, Wynne, and Stilgoe Citation2005). Proponents of RRI thus argue for active forms of governance that create spaces to interrogate the means and ends of science, technology and innovation.

As science administrators, politicians and academics attempt to translate these ideas into policy settings, a range of policy frameworks have been built (see Doezema et al. Citation2019; Owen Citation2014; Rip Citation2016). In many respects, these frameworks are contiguous with established ideas about how to strengthen the relationships between science and its publics through, for instance, the co-funding of research into the ethical, legal and social dimensions of a field, the use of technology assessment or public participation methodologies. But advocates of such frameworks also suggest that responsible research and innovation demands something new (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013).

The novelty we think RRI can offer is an attention to institutions – the rules, norms, organisational configurations and routine ways of thinking that shape how science and technology are governed (Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar Citation2017). This is not a simple proposition because institutions are shaped by interlocking social practices that build over time, making them difficult to illuminate, interrogate and challenge (Bickerstaff et al. Citation2010; Marris and Calvert Citation2020). Nevertheless, learning how to build new institutional practices is vital if we are to care about the governance of science, technology and innovation (Joly Citation2015). Those doing RRI must be concerned with how these routines emerge, are sustained and might be otherwise in different settings.

Here, and against this backdrop, we offer a perspective on the development of one policy framework, ERA CoBioTech’s Agenda for Responsible Research & Innovation, developed over a year-long period from November 2017. Our intention is not to offer a summary of the agenda, which can be accessed elsewhere (see Smith Citation2019). Instead, we focus on the usefulness of one particular proposition within it, that RRI is best thought of as a form of knowledge production, accessible through collaboration. As we explain below, foregrounding knowledge production has offered a route to start grappling with the institutional dimensions of science within the setting of an active funding programme. After a brief description of the funding programme and its RRI Framework, the article emphasises three moves that this proposition has enabled: unequivocally valuing the work it takes to care about science and society; opening-up established administrative practices; and, giving meaning to the concept within a unique institutional context.

ERA CoBioTech and its RRI framework

The ERA-NET Cofund on Biotechnology, ERA CoBioTech, is a life science funding programme constituted by several regional and national funding organisations, and supported under the European Commission Framework Programme (Grant Agreement 722361). Its stated aims are to unify previous ERA-NET funding programmes in systems biology, synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology; to leverage these fields and their inventions as technology drivers for a bio-based economy; and to do this in a way that demonstrates the public benefit of the life sciences. Between 2016 and 2021 the programme will disburse about €45m to multinational research consortia through its funding calls. However, the programme is constituted not just by its scientific research projects but also by a cluster of work packages through which the funders attempt to create space for the exchange of administrative knowledge. As part of this backstage work, the UK Research and Innovation Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (UKRI-BBSRC) led the development of a Strategic Innovation and Research Agenda (Berndt and Dayman Citation2018) with an associated Agenda for RRI (Smith Citation2019), delivered through a consultancy contract.

The Agenda positions RRI as one manifestation in a much longer trajectory of concern about the place of emerging science and technology in democratic societies (Hilgartner, Prainsack, and Hurlbut Citation2016). It aims to build capacity to better understand the relationships between science, technology and society; to reflect on the dominant framings of these relationships; and to develop institutional innovations, for instance in the form of altered administrative practices, in response. What kind of bio-based economy should be built? Who will benefit? Who should decide? Can the programme develop methodologies to give colour to the kinds of social, political and environmental relationships that it is supporting? These are the kinds of questions that ERA CoBioTech’s RRI Agenda is concerned with.

In short, the framework treats RRI as being concerned with social learning across an innovation system (Rayner Citation2004; Stilgoe Citation2018). Its aim is to use research policy as a means to improve the governance of emerging technologies and we have focused on four targets, roughly transecting the programme’s lifespan: agenda setting and call design; research consortia; spaces for knowledge exchange; and, monitoring and evaluation processes. In November 2018, the programme voted to fund four experimental collaborations around these targets, work which will be completed in 2021. Our work around each target is guided by a tranche of 13 actor- and site-specific recommendations. However, one of these, treat RRI as research is overarching (Smith Citation2019, 13).

What taking knowledge production seriously does

The recommendation to treat responsible research and innovation as research might at first sound like a tautology, but in our experience treating RRI as a form of research – or perhaps less tautologically, as a form of knowledge production – proved a productive way to give meaning to what to administrators and academics alike often seem to consider an inchoate sensibility. As we have developed the framework, we have noticed three ways in which knowledge production has become central to ERA CoBioTech’s understanding of RRI: as research within a scientific project; as institutional knowledge that shapes scientific cultures; and as methodological knowledge that allows us to articulate what it means to practice RRI.

Valuing unequivocally

To build the RRI Agenda we analysed several prominent policy frameworks that funders have used to account for the social, political, ethical and environmental dimensions of the life sciences. We also conducted qualitative interviews with staff in ERA CoBioTech-affiliated funding organisations and academics with experience of RRI in the life sciences. In this analysis, we saw one dominant vision about how RRI could be operationalised at scale: by delegating responsibility to researchers in projects using mandated ‘ELSA components’ or interdisciplinarity (see Hilgartner, Prainsack, and Hurlbut Citation2016; Strathern, 2005). We also saw that when making these demands of researchers, funders have been equivocal in the way they value the labour required to do this work, framing it as adjunct to ‘the scientific research’ (Rabinow and Bennett Citation2012).

There is a thicket of widely reported tensions with enacting RRI at the level of a research project, many of which can be traced to this adjunctive framing. If RRI is an accompaniment to the core scientific endeavour then it becomes one more imposition in an already crowded workspace (Felt et al. Citation2017). It is something to be taken care of – by doing some workshops, perhaps – rather than cared about (Evans and Frow Citation2016). And those doing RRI are frequently interpreted as fulfilling service roles as opposed to doing research, even though they are often academic researchers (Viseu Citation2015).

Advancing an understanding of RRI as research was an attempt to avoid some of the challenges associated with this logic. When we wrote the overarching recommendation, we thought of it primarily as a way to reframe RRI from being an adjunct to scientific practices to being precisely concerned with those practices. This framing does not demand a particular methodology such as interdisciplinary collaboration – a point which is important because the funding programme funds researchers from a wide range of epistemic and national cultures, with access to a wide range of resources. Instead, we are asking researchers to bring – and demonstrate – substantive consideration of the economic, environmental, ethical, political or social dimensions of their project as part of that funded research and for administrators to do the same. Positioning RRI as research was intended to signal that the funding programme was committed to, and valued, the ideas behind the term.

Opening up administrative practices

Being unequivocal about the framing of RRI and treating it as equivalent to other aspects of a scientific research project has brought a series of institutional considerations into view. For instance, taking seriously the claim that RRI should be a form of research opens up a range of administrative practices to reflection and modification.

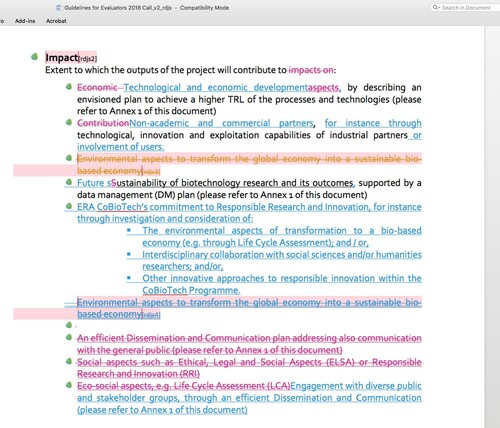

One, early, set of questions turned around call design: If RRI is research, what does this mean for the structure of funding calls? Should applicants have an ‘RRI section’ to complete? What guidance should be provided by the programme? Likewise, what does it mean for the evaluation of funding proposals? How should ‘it’ be scored? And what expertise is required to do this evaluation effectively? Do evaluators need training? To answer these questions, programme administrators have had to consider their own, often quite technical, administrative practices. Many of these practices are taken for granted; inherited from prior funding programmes or imported based on the preferences of one funding agency. They are codified in guidelines, scoring systems and in standardised software portals where design decisions have already been made. In very small and mundane ways, they are resistant to change.

Similar questions were also asked of the programme’s approach monitoring and evaluation. In each instance, being unequivocal about treating RRI as research has acted as a wedge to reopen these decisions, consider what a ‘good’ proposal looks like and how administrative practices might support or inhibit that idea of good. Although it seems trite to say, if RRI remained nothing but an adjunct, the administrators could simply ask applicants for an extra page of responsibility prose and leave them to get on with it. These practices would then remain closed.

Domesticating inchoate sensibilities

It has been noted that many of the phrases populating contemporary research policy are one-sided (Flink and Kaldewey Citation2018); it would be hard to come up with folk theorisations in support of the extractive economy, irresponsible stagnation or unsustainable regression goals (Guston Citation2015). But while attractive, these terms are also issue-less: in the abstract, they seem to express desirable sentiments, but it is only through context that they become meaningful (Marres Citation2007). Context is vitally important for responsible research and innovation because it is this context that shapes the boundaries of what is possible and what is not; in effect what RRI is allowed to mean. In the process, things may be twisted, added and jettisoned and the result will be a meaning of RRI that may or may not resonate with the location from which it came (Rothstein Citation2013; Wynne Citation2007).

This, in some respects, is a banal point to make for the interpretive social sciences. Of course context matters! But it is important to take it seriously. What, precisely, would it mean for your agenda-setting process if RRI was embraced throughout? What does it look like now? How would it change? While the answers to these kinds of questions can be gestured to from academia, they can only be addressed within the confines of an existing funding programme. And working within the confines of a funding programme means that it will be one part of an administrator’s job, to be completed in a set number of person months, from a background that may or may not have provided you with any head-start on interpreting social theory.

The final way, then, that treating RRI as a form of research has been helpful, is as a vehicle to produce methodological knowledge about what it means, and what it does not, to practice RRI within a given institutional setting. In this light, we have tried to approach the work from the position of an academic–practitioner collaboration that created answers together rather than a consultancy that outsourced the work of distilling universal best-practices and implanted them in ERA CoBioTech. Knowledge in this sense is both knowledge of how to articulate why RRI might be of value in a given context but also to suggest what it might look like in very practical terms. It is about learning how to read a situation and articulate with one another to produce workshop plans, tweaks to call text, and other subtle reformulations that may or may not be laden with subtext (). It is about learning what not to say (Fitzgerald et al. Citation2014). And it is about building the necessary trust to have such conversations that are part of the art and craft of governance (Macnaghten Citation2016; Zhang Citation2013).

The limits of learning

We have advocated for a particular approach to RRI and sketched out how it is helpful in one particular funding programme. Treating RRI as a form of knowledge production that spans the lifecycle of ERA CoBioTech is a way to start being clear about the value placed on it by administrators; it is a way to open-up administrative practices and build institutional reflexivity; and has been a way to build methodological knowledge about what RRI can mean within a given institutional configuration.

This approach is distinct from the European Commission’s Five Pillars framework, which emphasises a set of pre-ordained issues (education, engagement, ethics, gender, and open access) that closely mirror the different strands of the Science in Society funding programmes (Macq, Tancoigne, and Strasser Citation2020; Rip Citation2016). It is also distinct from EPSRC’s Anticipate, Reflect, Engage, Act (AREA) framework, which offers a process but no pre-defined activities to orient around (Owen Citation2014). However, ERA CoBioTech’s approach is not incommensurate with either; the European Commission’s issues may emerge as central concerns for the actors of ERA CoBioTech, and like the AREA framework, ERA CoBioTech’s framework is fundamentally concerned with questions of innovation governance. It is perhaps most clearly connected to the Norwegian Research Council’s approach, which framed RRI in terms of Argyris and Schön’s (Citation1978) seminal notion of organisational learning (Egeland, Forsberg, and Maximova-Mentzoni Citation2019).

But in suggesting that taking knowledge production seriously is a way to begin to unearth and then grapple with the institutional dimensions of science, we should also note that the approach exposes its own limits. Perhaps the most obvious of these is the broader institutional configuration of which ERA CoBioTech is a part – European Science, constituted by bureaucratic projects with grant agreements, pre-arranged timeframes and deliverables to be completed.

This project-driven way of organising a funding programme creates some perversities. Organisationally, ERA CoBioTech’s framework is located at its heart. From the outset, it was intended to be integrated and inform strategic decisions, was to come with clear guidance for its funded researchers, and was to be embedded within the programmes evaluation processes (European Commission Citation2016). It has been embraced by the funding partners and embedded into their on-going and future activities. But for an ERA-NET programme to be created, decisions about how to frame its purpose, what tasks are important, who should do them and even what the first funding call should be must already have been taken. Person-hours have been allocated and timescales defined. Because of the project form, the precise work of formulating what RRI might mean for ERA CoBioTech must happen after the first and largest funding call. In this configuration of research policy, funding programmes – seen by many as a way to move RRI beyond the constraints of the research project (Wynne Citation2011) – are subject to many of the same dynamics as the research projects they are envisioned to transcend (Aicardi, Reinsborough, and Rose Citation2018).

There are also regular points of renegotiation where the precise parameters of the programme are changed. ERA CoBioTech has a lineage that extends back to 2002 (EC Framework Programme 6) but this has also been punctuated by a series of breaks as administrators move from one Framework Programme to the next. Each is a moment of renegotiation and reinvention as administrators’ discourses are aligned with the policy vocabulary of the day. The move from FP7 to Horizon 2020 produced narratives of integration: the integration of systems biology, synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology, each previously with their own funding programme, as drivers for ‘the bio-based economy’; the integration of diverse administrative practices from across Europe; and the integration of prior approaches to addressing the environmental, ethical, legal, political and social dimensions of biotechnology into a new approach, RRI. And the most recent move – from Horizon 2020 to Horizon Europe – has reinvented the rhetoric of the endeavour, giving momentum to phrases such as mission-oriented innovation, circularity and open science. The ERA-NET mechanism has also been reimagined and the place of dedicated biotechnology funding programmes with their concern for RRI is in question in this future landscape (European Commission Citation2019). While the concern with ‘science’ and ‘the public’ is perennial, in this new landscape it remains unclear to us which aspects of the more fragile experiments we have embarked on will be allowed to travel.

What might this broader context mean for ERA CoBioTech’s RRI Agenda? From our perspective, as administrators and academics, we can foresee at least two possibilities. The first is that the work we have embarked on remains a policy experiment and subject to the project form. The desire to make sense of a new, opaque, term created a policy window for STS to collaborate with science administrators. Through this collaboration, we have moved the concept of RRI beyond a broad procedural idea (Macnaghten Citation2020) and beyond a set of specific issues (see Rip Citation2016) to specify concrete sites for research funders to focus on. Some of the methods we developed will be written up and the implications for science policy shared. RRI frameworks might quietly recede into the background as we continue with our jobs. The ideas and lessons created in this moment would be indirectly carried forward but with a new gloss provided by any number of buzzwords – circularity, co-creation, missions, open science, or transformative innovation. This is perhaps too glib a suggestion to conclude with. But it emphasises the longer trajectory of STS engagement in research policy and the importance of ‘hooks’ that can start the conversation. Taking context seriously means being aware of the currency given to particular policy concepts. If RRI no longer offers something to orient around then even a very recent history would suggest there are alternatives that will allow the social sciences to work collaboratively with practitioners, saying similar things in slightly different ways (see Felt and Wynne Citation2007; Wilsdon, Wynne, and Stilgoe Citation2005).

A second, perhaps more ambitious, possibility would be to take seriously our initial claim that RRI demands new spaces within an institutional landscape to debate the means and ends of science. Building on the nascent knowledge, relationships and trust that has been sparked by a desire to ‘have’ RRI during the last decade, it may be possible to build infrastructures that transcend the project form by creating fora for not just for researchers in scientific projects but also for administrators and STS scholars to experiment with the governance of science, technology and innovation. Over time, through collaboration with ‘world-making projects, mutual worlds – and new directions – may emerge’ (Tsing Citation2015, 34).

One institutional context to prioritise is the reimagined set of partnerships envisaged under Horizon Europe. In parallel to the work of ERA CoBioTech, we have watched several other ERA-NETs develop their own approaches to RRI. Like ERA CoBioTech’s approach, none of them mobilise extant RRI frameworks in any straightforward way but has made sense of the ideas behind responsible innovation in ways that suit their context. This patchwork of organisations with their guidelines, events, and policy experiments has built practitioner knowledge of the social, political, environmental and ethical intricacies of research policy in multiple national funding organisations. Actively building connections between the people behind these (to date) distinct approaches would consolidate their knowledge, and continue the learning begun in Horizon 2020 beyond 2021. It would require further resources and commitments from funding agencies, and it would require people who care. But then, perhaps that is precisely the point.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all ERA CoBioTech staff who participated in the research informing this perspective. Thanks also to two anonymous reviews and the special issue editors, who helped us to clarify our argument. Kamwendo and Smith were supported by the ERC Project, ‘Engineering Life;’ 616510. Smith was supported by the following awards: EP/JO2175X/1 and BB/MO18040/1. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the authors, and not necessarily to the author's employer, organization, committee or other group or individual.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert D.J. Smith

Robert Smith is a research fellow at Science, Technology & Innovation Studies, School of Social & Political Science, The University of Edinburgh. His research examines the social, political and policy dimensions of biological engineering.

Zara Thokozani Kamwendo

Zara Thokozani Kamwendo is a research fellow at St John's College, Durham University. Her research examines the sociology of scientific knowledge and the sociology of religion.

Anja Berndt

Anja Berndt is a senior portfolio manager at the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK Research and Innovation. She was previously BBSRC programme manager for ERA CoBioTech.

Jamie Parkin

Jamie Parkin is Strategy and Policy Manager, Technologies and Infrastructure at the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK Research and Innovation.

References

- Aicardi, C., M. Reinsborough, and N. Rose. 2018. “The Integrated Ethics and Society Programme of the Human Brain Project: Reflecting on an Ongoing Experience.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (1): 13–37.

- Argyris, C., and D. A. Schön. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Berndt, A., and E. Dayman. 2018. ERA CoBioTech Strategic Agenda - A Vision for Biotechnology in Europe. Swindon: European Research Area Network Cofund for Biotechnologies.

- Bickerstaff, Karen, Irene Lorenzoni, Mavis Jones, and Nick Pidgeon. 2010. “Locating Scientific Citizenship: The Institutional Contexts and Cultures of Public Engagement.” Science, Technology & Human Values 35 (4): 474–500.

- Doezema, Tess, David Ludwig, Phil Macnaghten, Clare Shelley-Egan, and Ellen-Marie Forsberg. 2019. “Translation, Transduction, and Transformation: Expanding Practices of Responsibility Across Borders.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (3): 323–331.

- Egeland, C., E.-M. Forsberg, and T. Maximova-Mentzoni. 2019. “RRI: Implementation as Learning.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (3): 375–380.

- European Commission. 2016. Grant Agreement Number: 722361 — Cofund on Biotechnologies (CoBioTech). Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General Research & Innovation.

- European Commission. 2019. Orientations Towards the First Strategic Plan for Horizon Europe. Brussels: DG Research and Innovation.

- Evans, S.W. and E.K. Frow. (2016) Taking Care in Synthetic Biology. In Absence in Science, Security and Policy: From Research Agendas to Global Strategy, edited by B. Balmer and B. Rappert, 132–153. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Felt, U., et al. 2017. “‘Response-Able Practices’ or ‘new Bureaucracies of Virtue’: The Challenges of Making RRI Work in Academic Environments.” In Responsible Innovation 3, edited by L. Asveld, 48–68. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Felt, U., B. Wynne, M. Callon, M. E. Goncalves, S. Jasanoff, M. Jepsen, P-B. Joly, Z. Konopasek, S. May, C. Neubauer, A. Rip, K. Siune, and A. C. Stirling. 2007. Taking European knowledge society seriously: Report of the expert group on science and governance to the Science, Economy and Society Directorate, Directorate-General for Research, European Commission. Luxembourg: European Commission.

- Fitzgerald, Des, Melissa M Littlefield, Kasper J Knudsen, James Tonks, and Martin J Dietz. 2014. “Ambivalence, Equivocation and the Politics of Experimental Knowledge: A Transdisciplinary Neuroscience Encounter.” Social Studies of Science 44 (5): 701–721.

- Flink, T., and D. Kaldewey. 2018. “The New Production of Legitimacy: STI Policy Discourses Beyond the Contract Metaphor.” Research Policy 47 (1): 14–22.

- Guston, D. H. 2015. “Responsible Innovation: Who Could be Against That?” Journal of Responsible Innovation 2 (1): 1–4.

- Hilgartner, S., B. Prainsack, and J. B. Hurlbut. 2016. “Ethics as Governance in Genomics and Beyond.” In The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies (4th ed.), edited by U. Felt, R. Fouché, C. A. Miller, and L. Smith-Doerr, 1043–1091. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Joly, P.-B. 2015. “Governing Emerging Technologies? The Need to Think Outside the (Black) Box.” In Science and Democracy: Making Knowledge and Making Power in the Biosciences and Beyond, edited by S. Hilgartner, C. A. Miller, and R. Hagendijk, 133–155. New York: Routledge.

- Macnaghten, P. 2016. The Metis of Responsible Innovation. Inaugural Lecture upon Taking the Post of Personal Professor in Technology and International Development at the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation Chair Group at Wageningen University on 12 May 2016. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Macnaghten, P. 2020. The Making of Responsible Innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Macq, H., É Tancoigne, and B. J. Strasser. 2020. “From Deliberation to Production: Public Participation in Science and Technology Policies of the European Commission (1998–2019).” Minerva 58: 1–24.

- Marres, N. 2007. “The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy.” Social Studies of Science 37 (5): 759–780.

- Marris, C., and J. Calvert. 2020. “Science and Technology Studies in Policy: The UK Synthetic Biology Roadmap.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 45 (1): 34–61.

- Owen, R. 2014. “The UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council’s Commitment to a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 113–117.

- Rabinow, P., and G. Bennett. 2012. Designing Human Practices: An Experiment with Synthetic Biology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rayner, S. 2004. “The Novelty Trap: Why Does Institutional Learning About New Technologies Seem so Difficult?” Industry and Higher Education, 18 (6): 349–355.

- Ribeiro, B. E., R. D. Smith, and K. Millar. 2017. “A Mobilising Concept? Unpacking Academic Representations of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 81–103.

- Rip, A. 2016. “The Clothes of the Emperor. An Essay on RRI in and Around Brussels.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 290–304.

- Rothstein, H. 2013. “Domesticating Participation: Participation and the Institutional Rationalities of Science-based Policy-making in the UK Food Standards Agency.” Journal of Risk Research 16 (6): 771–790.

- Smith, R. D. J., et al. 2019. An Agenda for Responsible Research and Innovation in ERA CoBioTech. Swindon: Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

- Stilgoe, J. 2018. “Machine Learning, Social Learning and the Governance of Self-driving Cars.” Social Studies of Science 48 (1): 25–56.

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580.

- Tsing, A. L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Viseu, A. 2015. “Caring for Nanotechnology? Being an Integrated Social Scientist.” Social Studies of Science 45 (5): 642–664.

- Wilsdon, J., B. Wynne, and J. Stilgoe. 2005. The Public Value of Science: Or How to Ensure That Science Really Matters. London: Demos.

- Wynne, B. 2007. “Dazzled by the Mirage of Influence?: STS-SSK in Multivalent Registers of Relevance.” Science, Technology & Human Values 32 (4): 491–503.

- Wynne, B. 2011. “Lab Work Goes Social, and Vice Versa: Strategising Public Engagement Processes.” Science and Engineering Ethics 17 (4): 791–800.

- Zhang, J. Y. 2013. “The Art of Trans-Boundary Governance: The Case of Synthetic Biology.” Systems and Synthetic Biology 7 (3): 107–114.