ABSTRACT

In 2014, the Swedish innovation agency Vinnova set up the program ‘Gender and Diversity for Innovation’, which has its roots in norm-critical innovation. In line with rationales for responsible innovation, a central aim of the program is to identify and challenge discriminatory norms to develop more inclusive and equal innovation processes. This article presents the findings of an in-depth analysis of 34 projects funded under the program. It explores how norm-critical innovation has been practiced and performed in various empirical settings and whether norm-critical innovation practices could be a way forward for the implementation of responsible innovation. Using a qualitative research design, we identify the most common activities and outputs in the projects and carve out the core characteristics of norm-critical innovation practice. Furthermore, the paper explores the value and limitation of norm-critical approaches for fostering responsible innovation and addressing societal challenges more broadly.

Introduction

Innovation has long been understood to be a driving force of economic growth and, by extension, social welfare. However, in recent decades, this dominant innovation policy paradigm has met increasing critique as we have gained insights into how technology and innovation can be both beneficial and detrimental to societal and environmental developments (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Additionally, innovation policy has come under scrutiny regarding its function to address grand challenges such as climate change, equality, and poverty (Kuhlmann and Rip Citation2014; Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018; Mazzucato Citation2018). As a response, a movement of scholarly ideas and policy initiatives has emerged. Internationally, this entails the concepts of responsible innovation (RI) and responsible research and innovation (RRI) that highlight the need to identify in advance potential unwelcomed impacts and align innovation to the values, needs and expectations of society (Bessant Citation2013; Owen et al. Citation2013; Owen and Pansera Citation2019).Footnote1

RI principles, such as transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation, and responsiveness (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020), have had a considerable impact in terms of widening the perspectives for guiding knowledge development and utilization processes (Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021), mainly related to including broader social and environmental aspects in areas such as ICT (see e.g. Urquhart and Craigon Citation2021), healthcare (see e.g. Demers-Payette, Lehoux, and Daudelin Citation2016), nanotechnology (see e.g. Heltzel et al. Citation2022) neurotechnology (Aicardi, Reinsborough, and Rose Citation2018) and synthetic biology (Pansera et al. Citation2020). However, despite significant efforts to operationalize RI principles in various areas, the context-specific nature of innovation requires further insights into how RI principles are put into practice in diverse real-life contexts (Owen and Pansera Citation2019; Urquhart and Craigon Citation2021). Moreover, RI initiatives have a tendency to focus on improving the alignment of innovation with societal values and are therefore usually set up as parallel add-ons to innovation processes, sometimes as detached external impositions, rather than as integrated parts of the innovation process (Stahl et al. Citation2021). Consequently, RI initiatives tend to disregard the need to transform the normative underpinnings of innovation per se, replacing a growth and competition paradigm with a more socially and environmentally desirable imperative (Cuppen, van de Grift, and Pesch Citation2019; van Oudheusden Citation2014). Although RI was initially developed around what has been described as shared European values, such as environmental protection, social inclusion, and democracy (von Schomberg Citation2013), the last decade of RI research and practice has provided little support for understanding the role of RI in enabling the normative change that the manifestation of these values obligates (Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021; Pansera et al. Citation2020). Indeed, gender equality and social inclusion were highlighted in the RI movement's establishment (von Schomberg Citation2013), yet gender perspectives are seldom the focus of the current RI literature (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017).

Against these shortcomings, we aim to explore the connection between generic RI principles and practices of normative change. We do so by means of an in-depth qualitative analysis of the activities and outputs of projects funded through the norm-critical innovation (NCI) program of the Swedish innovation agency Vinnova. Sweden’s long tradition of gender equality work has brought forward the notion of NCI that centers around the idea of identifying problematic social norms (i.e. institutionalized rules and practices concerning gender, ethnicity, disability, religion or age) with the objective of challenging them through innovation as well as ensuring that future innovations do not perpetuate them.

Vinnova launched the program ‘Gender and Diversity for Innovation’ in 2014. It has been running for six years and has funded 115 projects with approximately 10 million Euros. The NCI projects funded within the program attempt to intervene in existing contexts by identifying, critically reflecting on and challenging norms to create more inclusive and equal societies. NCI embraces reflective practices that question the underlying meaning of innovation, how innovations are developed and established, for whom and for what aim. As such, NCI bears essential resemblances to the idea of RI in that they share a critical and reflective approach to the dynamics and relationships between science, innovation, politics and society and the ambition of directing innovation to the values, needs, and expectations of society at large. We thus see these NCI projects as attempts to embrace inclusive and reflective guiding principles as the fundamental rationale for innovation and unique endeavors to operationalize and translate rather abstract RI principles into tangible practices. Consequently, examining the program gives us a valuable opportunity to gain insights into a real-world application of RI principles as an integrated part of an innovation process that targets normative change.

The paper is structured as follows. We first provide a discussion of the conceptual framing of this paper related to the connection between the concepts of NCI and RI. Next, we present our methodology and the empirical setting of NCI in Sweden and at Vinnova. We then show our results and conclude by discussing how insight into practices induced by norm-critical thinking contribute to our understanding of RI practice and its potential impact.

Norm-critical innovation and its connection to responsible innovation

Norm-critical innovation and its conceptual background

In the context of this paper, NCI is defined as a process of identifying problematic social norms (i.e. institutionalized rules and practices) with the objective of challenging them through an array of process, product, or service innovations. The concept of norm-criticality originates from anti-oppressive and queer theories that aim to shed light on how norms intersect to create social power structures of exclusion and discrimination (Butler Citation1993; Freire [Citation1970] Citation2000; Kumashiro Citation2002, Citation2015). Social exclusion is a multidimensional process involving the lack of or denial of products, services, resources, or human rights, which affect the quality of life of individuals (Levitas et al. Citation2007). Norms function as stable underlying rules for how we behave and are often difficult to change. In everyday language, norms usually refer to what is considered normal or natural. Following the Swedish Discrimination Act (Discrimination Act, 2021), norms are deemed problematic and discriminatory if they enforce social exclusion based on any of the seven grounds of discrimination covered by Swedish law (sex, transgender identity or expression, ethnicity, religion or other belief, disability, sexual orientation, and age). A norm-critical perspective analyses social structures and critically challenges normative behavior and assumptions. It departs from the question of who benefits and who is disadvantaged from a particular social structure. This question highlights why and how norms are reproduced and how they can be changed through our actions. Norm-critical theories and frameworks are generally considered to be value-based. Compared to a descriptive theory that explains how things are, a value-based theory looks at how things should be and how we can get there.

Norm-critical perspectives have received particular attention in the field of design. Design is a conscious process of thinking and acting with the intention of creating desired outcomes (Friedman Citation2000; Nilsson and Jahnke Citation2018). The time and economic constraints of conventional commercial design processes leave no room for questioning the embedded norms, which has led to a perpetual reconstruction of existing social norms and values. This is visible, for instance, in the many products that are gendered through the choices of shape, color, material, and names (Ehrnberger et al. Citation2017), with severe implications for a large amount of the population. For instance, even though women represent half of the car drivers in Sweden, crash test dummies have until recently been designed based on an average adult male body type (Eikeseth and Lillealtern Citation2013). At the same time, women are three times more likely to suffer from whiplash injuries than men (Krafft et al. Citation2003). Norm-critical design has emerged as a critique of the status quo of many design practices. But the aim is not to solve existing problems through a new and improved product but to call things into question and problematize existing discourses and boundaries (Isaksson et al. Citation2017; Dunne and Raby Citation2013). Norm-critical design attempts to overcome pre-configured ideas of products, practices, and users through norm-critical practices in and between organizations that encourage a more collaborative and critical inquiry into different societal needs.

Given the close association between design and innovation, norm-critical approaches have found their way into innovation discourses, particularly related to gender inequality (Lindberg Citation2010; Nyberg Citation2009). Innovation includes, by definition, some form of deviation from a status quo as it involves developing and disseminating something new that is different from the old. Despite the transformative capacity of innovation in some areas (e.g. technological breakthroughs), many innovations still perpetuate certain norms in other areas (e.g. gender). A norm-critical perspective on innovation thus entails a deliberate reflection of the normative underpinnings of innovation and an assessment of the directionality of innovation to reveal reinforced and perpetuated societal structures. The focus is on normative social behavior and practices on individual and group levels, intending to increase equality and equity on a systemic level. NCI focuses on understanding and challenging the norms that lead to social exclusion, which presupposes understanding the shared social context wherein the normative behavior patterns occur.

Connecting norm-critical and responsible innovation

For over a decade, a growing stream of policy and scholarly ideas and frameworks have gathered under the concept of RI aimed at emphasizing socially and ethically desirable aspects of technology and innovation (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021). RI emerged from aspirations to widen perspectives in technology assessments to include socio-technical aspects and anticipate the broader societal impact of emerging technologies (Owen and Pansera Citation2019; Felt Citation2018). The interpretation of this aspiration and the corresponding conceptual frames are diverse, as RI brings together various approaches to anticipatory and inclusive governance and design schemes (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020). These variations also pertain to significant differences between geographical framings. Although EU efforts have dominated, there are also approaches in the UK, USA, and other regions (Cuppen, van de Grift, and Pesch Citation2019). Yet they all share the aim to understand and respond to the social, ethical, environmental, and political entanglements, dilemmas, uncertainties, and risks that innovation presents (Owen et al. Citation2013; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). These schemes have revealed critical aspects of technological innovations at an early stage and shown how they can be embedded and addressed in research and innovation practices (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013; von Schomberg Citation2012; Owen and Pansera Citation2019).

Even though the Swedish innovation context has been colored by EU RI efforts, NCI originates from elsewhere. While RI builds on the foundations of responsibility in science, such as anticipatory governance and technology assessment, NCI departs from anti-oppressive and queer theories. Consequently, this leads to differences between the perspectives. While NCI often places gender and social equality at the heart of the innovation process, gender and social inclusion is only one of several pillars that lay the foundation for RI (Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021). It also follows that NCI lacks the clear focus on environmental impacts of innovation that RI schemes include (Cuppen, van de Grift, and Pesch Citation2019).

Further differences between the perspectives emerge upon a deeper consideration of RI features. A common distinction when comparing RI schemes concerns whether RI is seen as a process in terms of specific activities that innovators enact to align their innovative efforts with societal values or as an outcome of such activities in terms of a product (von Schomberg Citation2013). Following a synthesizing review, Fraaije and Flipse (Citation2020) present three qualifiers central to RI as a product – societal relevance (including ethical norms and equitable use), market competitiveness and scientific quality. NCI obviously resonates with the first of these qualifiers, while neither market competitiveness nor scientific quality are inherent aspects of the NCI scheme. On the contrary, NCI seeks to question the status quo of innovation, including conventional market logics and scientific standards, to challenge the norms that lead to social exclusion.

Fraaije and Flipse (Citation2020) also offer five qualifiers of RI as a process – transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation, and responsiveness. Transparency concerns openness and justification of assessment criteria and objectives for innovation, the role and distribution of responsibility among stakeholders, and the limitations and uncertainties (Sykes and Macnaghten Citation2013; Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Owen and Pansera Citation2019). This aspect of RI makes up a second difference since NCI is not as explicitly concerned with openness or transparency. However, transparency can be considered an enabling element to materialize other aspects of NCI, in the same way as transparency paves the way for creating inclusion and reflexivity (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020).

The four remaining qualifiers presented by Fraaije and Flipse (Citation2020) are adopted from a seminal framework of four key RI process dimensions offered by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013). It is mainly through these that the similarities between NCI and RI become visible. Inclusion, the first of these four, concerns opening up the visions, purposes, processes, and emerging impacts of science, technology, and innovation to inclusive deliberation. It involves inviting new voices, often the wider public, to innovation governance. This echoes the focus of NCI on creating societally desirable objectives for trajectories where problem-owners are involved in the innovation process. Reflexivity consists in reflecting on an innovation trajectory’s underlying purposes, motivations, and norms and their alignment with social values. It entails seeking answers to what is known and uncertain and identifying assumptions, areas of ignorance, and ethical dilemmas. Thus, RI involves raising awareness about the limitations of knowledge and about particular framings of innovation that may not be universal. In this way, RI resonates well with the norm-critical aspirations of NCI. Anticipation includes articulating potential intended and unintended outcomes of innovation. Indeed, a central dimension for both RI and NCI is shedding light on future consequences of resource, power and information asymmetries inherent in innovations and innovation processes (Ehrnberger Citation2017; van Mierlo, Beers, and Hoes Citation2020). Finally, responsiveness aims to ensure that broadly configured anticipatory, reflexive, and deliberative knowledge has a bearing on and shapes the purposes, processes, and impacts of innovation. It includes enacting responsibility by empowering social agency in choices relating to innovation and futures and keeping options open for coming generations. As such, this dimension of RI aligns with the emancipatory ambitions of NCI that seek to challenge problematic aspects of innovation trajectories through a novel approach to innovating.

As it appears, NCI and RI converge in critiquing the unconditional and inherent goodness of innovation and the commitment to redirect innovation processes towards more responsible and inclusive directions. In light of this, NCI may be regarded as a subset of the multifaceted schemes that make up RI. However, some contradictory differences may contend against this. RI schemes that build on conventional market logics and scientific standards may stand in contrast to the critique of the status quo that is fundamental to the NCI rationale. However, NCI can be seen as part of a movement within the RI realm that call for questioning the dominant growth and competition paradigms of innovation (Cuppen, van de Grift, and Pesch Citation2019; van Oudheusden Citation2014; Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021; Pansera et al. Citation2020).

Methodology

The exploratory nature of the study calls for an explorative, qualitative approach. We are interested in the specific processes through which principles of norm-critical innovation become operationalized and applied in projects funded by a norm-critical innovation program. However, we are not concerned with evaluating the impact of the program per se. The effect of applying a NCI approach on changing norms, perceptions, routines, and overall innovation practices often occurs with a substantial time lag. Correspondingly, we focus on the empirical identification of activities and outputs within the projects and, based on those, offer a tentative assessment about the potential impact of the projects for project participants themselves as well as the broader environment.

Case selection and data collection

In Sweden, research and politics have a long tradition of critically analyzing and changing norms, in particular when it comes to gender structures in organizations and innovation (Fürst Hörte Citation2009; Lindberg Citation2010; Nyberg Citation2009; Wahl et al. Citation2011). The program ‘Gender and Diversity for Innovation’, which is the subject of this analysis, was launched by Vinnova in 2014, following a range of rather narrow gender-related initiatives (Andersson et al. Citation2012; Balkmar and Nyberg Citation2006). The program broadened the scope to advance equality and equity in relation to all seven protected grounds of discrimination in Sweden (sex, transgender identity or expression, ethnicity, religion or other belief, disability, sexual orientation, and age). Between the years 2014 and 2019, the program announced seven calls and received 640 applications, 115 of which were funded. All calls share the overall objective that a norm-critical perspective needs to be applied to advance equality or equity, but also differ regarding their emphasis on method development (first three calls), sustainable growth and triple helix engagements (number 4), companies (number 5), sustainable development goals (number 6 and 7) or international collaborations (number 7).

Our study builds on the triangulation of data from multiple sources related to the program, including interviews, documents, and workshops with a reference group. All projects must issue a report that summarizes their context, activities and outputs, but they often lack a description of how the project came about and unfolded over time. Therefore, we also conducted 25 semi-structured interviews with project participants. The selection of the interviewees was based on a sampling of 34 projects. We strived to balance the different calls, types of actors, sectors, and innovations. The interviewees all had central roles in at least one project, some were active in several projects. Some of the studied projects were still ongoing at the time of the interview. In addition, we interviewed the program managers at Vinnova, and held two workshops with a reference group to clarify, discuss, confirm, and revise preliminary findings. The complete list of analyzed projects can be found in Appendix. gives an overview of the data and its purpose and gives more detail on the interviews.

Table 1. Collected data and application.

Table 2. Distribution of projects covered by interview.

Data analysis

In line with our explorative approach, the analysis has been data-driven in a bottom-up, inductive process, focusing on the identification and interpretation of the following three categories:

Activities: All the actions conducted by the project participants as a part of the project that contributed to the operationalization, representation, and realization of norm-critical innovation.

Outputs: All the tangible results being created during the project duration that are representing and realizing norm-critical innovation. Outputs are a consequence of project activities.

In addition, we collected and analyzed data relating to a third category, namely the impact of activities and outputs:

Impact: The broader effects that the activities and outputs of a project had for the project participants themselves as well as the broader environment.

Due to the fact that impacts, such as a change in norms, are not necessarily causal and straightforward and often take time to unfold (results might be seen years after project endings), we refrain from a detailed analysis of the impact of the studied innovation program. Instead, we offer a more general discussion on the particularities of activities and outputs in norm-critical innovation projects and theorize about their potential effect for RI practices and goals.

Results

We present our results in three steps. We put forward a review and classification of the main activities and outputs that occurred across all projects. Following this, we provide a tentative assessment of the impact of the projects for project participants as well as the broader environment in relation to the goals of NCI.

Recurring activities in norm-critical innovation projects

The in-depth analysis of the 34 projects revealed a range of recurring activities and outputs that account for the bulk of available time and resources in the projects. We grouped them into five categories: Fostering reflexivity, collaborating inclusively, sharing knowledge, staging interventions, and advocating. provides a comprehensive overview.

Table 3. Activities in norm-critical innovation projects.

Fostering reflexivity refers to activities that aim at enhancing the potential to reflect upon the status quo as well as make the imagination of an alternative future possible. These activities are closely related to the essence of the program, namely, to be norm-critical, i.e. to identify discriminatory and excluding norms and challenge them. Many projects thus spend a lot of time on developing methods to go about seeing and understanding norms, but also on finding ways to create, envision, experience, and present an alternative future. Projects often work with ethnographic methods, such as participant observations, and qualitative methods more generally, e.g. interviews, focus groups, workshops or text analysis. But also more graphic methods are uses, such as simulations and visualizations as well as the building of prototypes. The project Norm creativity in Smart housing Småland, for instance, used the methodology metadesign, a conceptual framework originally developed by Dutch designer Andries Van Onck in 1963 at Ulm School of Design. In a nutshell, the aim is to design an interdisciplinary interaction infrastructure that brings people together in a way that can bring forward solutions that were previously unthinkable. Today, this methodology is applied by various consultancies as well as in the context of living labs. Another example for activities to foster reflexivity comes from the project Open norm critical innovation for relational inclusion (ONCIRI). The purpose of the project was to develop sports equipment for children with and without disabilities. The project activities included researchers filming, interviewing, and observing children in a school environment and based on that develop prototypes (e.g. Kids Sand Glove with an instruction folder and a Paralympic Bench) that could then be shown to the children for suggestions for improvement.

Collaborating inclusively is encompassing activities that are geared towards building up structures that allow for an inclusive and collaborative design process. In general, many of the studied projects put an emphasis on including and having dialogs with a diverse range of actors, within and beyond the project. The majority of projects have involved stakeholders from different societal sectors (the public sector, civil society, private firms and/or higher education institutions) to include a wide variety of perspectives and knowledge bases when addressing a shared problem. Of particular importance for collaboration are problem owners as well as users and consumers. Facilitating inclusive development and design processes among such a wide variety of actors that often lack a common background and understanding can be challenging. Thus, many projects have put significant efforts into setting up structures for enabling these processes, such as designing participatory and interactive research, building arenas for wide stakeholder dialogs, conducting internal courses and lectures, and arranging conferences. The project Powerup! Participatory design of accessible video games had the aim to provide preconditions for the gaming industry to make games more inclusive for people with disabilities. The project activities included workshops where actors from the gaming industry, the public sector and NGOs working with disabilities were invited to discuss how to make games more inclusive and comply with legislation. Another example is the project The whole of Hallonbergen – a norm-creative design process of a park lane, where the purpose was to explore how a suburb in Stockholm can be developed with a focus on making the public space safer for girls and women. The project activities included popups alongside the park lane, built together with female young residents from the area.

Sharing knowledge encompasses activities that contribute to the dissemination of knowledge to different audiences. Knowledge sharing is vital for the project internally to bridge cultural gaps and differences in life experience and backgrounds, but they are also crucial in order to have an impact beyond the immediate boundaries of the project. Many of the projects thus spend a large share of their time on organizing network days and conferences, holding workshops and presentations, and writing reports, academic publications, and contributions to media outlets. While these activities are considered rather traditional outreach of innovation projects, we also found a range of activities that are more creative in nature, such as curating exhibitions and allowing the public into spaces to have a real experience. In addition, some projects also engage in developing education, such as courses and lectures. One example thereof is from the project Norm-creative Visualization in Urban Development. The aim of the project was to contribute to an inclusive city development process. Their pre-study showed that visualizations in these processes are often stereotypical when it comes to age, gender or ethnicity. So the project applied norm-critical approaches to the visualization process. The team then developed a handbook and a guide as educational material for people who want to work norm-critically when doing visualizations in architecture and city development. The handbook provides different tactics – such as shifting perspectives, provoking, collaborating – that gives the designer tools for thinking and acting differently in the visualization process.

Staging interventions refers to a particular kind of activity that is used among several projects to try to enable a shift in perspective. Some of these activities have the explicit ambition to disrupt existing doctrines and have a provocative function to create equal and inclusive spaces, items, and practices. Projects put substantial efforts into intervening with normative structures and practices by contextualizing new knowledge through utilization activities. Sometimes their goal is to trigger an emotional reaction that can help understand the issue at hand. Very often, there is a visual and material component to it, for instance when using visualizations or arranging exhibitions so that people get a more holistic experience. Also, the use of concrete spaces in the city or the setting up of living labs is a common occurrence, as well as the use of provotypes, i.e. of thought-provoking artefacts that incite discussions among a variety of audiences. This was especially visible in the project FIRe – Future Inclusive Rescue Service. The team worked with provotypes to make visible and critique norms hindering a more inclusive development within the fire service. These included two different types of changing rooms as well as a new product, i.e. a kind of underwear-uniform for firefighters. Both served as topics for discussions where employees could reflect on how inequality is expressed in both social interaction and the physical environment.

Advocating entails activities that are political in nature and contribute to raising awareness of an issue more generally. Considering the disruptive nature of many of the projects, these activities are quite common and include collaborating with policy makers, professional associations, or businesses as well as writing news articles and popular science pieces and participate in panel talks and organize seminars. In the project Trucks for everyone: Development of norm-critical innovation at Volvo, the goal was to increase a norm-consciousness within Volvo innovation processes. The project activities included several national and international academic presentations, two published articles and three submitted for publication. Another example is from the project Women on Wheels with the objective of making bicycling accessible and attractive for groups who do not bicycle today. The team has worked extensively with advocacy in the policy domain. After the project ended, parts of the Swedish project team created a consultancy that offers education, workshops, process management, and inspirational lectures. They consult with municipalities when improving or creating new bicycle infrastructure. One of the main task is to translate more theoretical concepts such as norm-criticality and intersectionality to a rhetoric that is understood by city planners.

Recurring outputs in norm-critical innovation projects

Many of the activities described above are not only process-related actions but also result in tangible outputs. Sometimes activities and outputs are two sides of the same coin and outputs can be understood as a result of the project activities. Given the scope of the projects, only completed step 2 projects provide sufficient conditions for project outputs to emerge. Thus, when identifying project outputs, we departed from the 14 step 2 projects studied in-depth. From these, six main categories can be identified. provides an overview.

Table 4. Main outputs of norm-critical innovation projects.

Guidelines are one of the most prevalent outputs of the studied projects. They take the form of documents, toolkits, handbooks, or policies, sometimes web-based and digital, that give instructions on how to approach a norm-critical design and development process and how to incentivise norm-critical behavior. One examples of a guidebook for norm-creative visualization practices in urban development was mentioned above. Another interesting example is the toolbox created by Equalisters Media Project that worked to create more equal and inclusive spaces. Based on the experiences of the project activities, they developed clear guidelines and a corresponding toolbox on how to increase inclusivity in public spaces in four steps: Disturb – Support – Spread – Self-generate. These four steps, with their respective practices, can be applied by any actors in any type of public space to increase inclusivity.

Visualizations and materializations are another common type of output. They encompass the visual and material creation of artifacts that contribute to enhancing reflexivity and awareness. Prototypes/provotypes, computer generated models, exhibitions, scenarios, or simulations are good examples. They represent norm-critical ideas or provide opportunities for imagination and experience. A reoccurring sort of prototype developed with that intention is the so-called provotype. It is a design object that is not representing any realistic product but rather challenges the status quo and enables debates. The changing rooms at the fire station or the new underwear for fire fighters mentioned above are examples of provotypes. Another one was developed in the project Norm-conscious rooms for play and learning in preschool, where the team deliberately built a 3D provotype of an exclusive pre-school in order to reveal the underlying problematic standards and biases common in many preschools in Sweden today. Simulation was used by the project Preclinical learning center with norm critical focus – a new way of caring. Project outputs included an interactive education in a clinical simulation environment. The material developed for the education is based on norm-critical pedagogy where students develop more conscious approaches in a patient care situation. The project outputs also include a norm-inclusive photo exhibition in the education center.

Interactive spaces can also be interpreted as a project outcome. The category refers to outputs that create physical spaces to increase inclusive collaboration and design. A prime example thereof is living labs. Living labs have become particularly popular in urban areas where they provide interactive spaces where actors get together to experiment, test, design, and learn in real time. Living labs thus function as an arena for stakeholder engagement and co-creation processes. One project which can be considered to have built something similar to a living lab is The whole of Hallonbergen – a norm-creative design process of a park lane The City. Sundbyberg, close to Stockholm, has drawn attention to the fact that women have been underrepresented in public spaces in specific districts, whereupon the project has begun to explore norm-creative solutions for an equal urban space. Together with young people from the area, the team has built temporary installations which have served as a basis for discussion for possible permanent functions. The spaces were evaluated to learn under which conditions (different colors, forms, functions, activities) women and other groups, such as the elderly or families with small kids, are using public spaces in this district.

Education can be seen as another type of output that enables knowledge-sharing and learning. Several projects have developed courses (for internal and external participants) as well as lectures and other kinds of presentation. The project Swedish Voices, for instance, has been involved in starting six local media labs. The project team has developed methods and tools for producing productions with norm-critical perspectives. Over 500 young people have participated in the project activities, 250 productions have been published in social and traditional media and reached half a million people. One production was #jagröstar, in collaboration with the local public service channel SVT Umeå, concerning young people voting.

An output category that is rather traditional is publications. The projects have generated a significant number of publications covering various disciplines. First and foremost, they are of an interdisciplinary and practice-oriented nature and concern social sciences and humanities, which is rather unique in innovation projects. Publications have frequently included practice-oriented reports targeting policymakers or practitioners or been aimed at the public at large. These publications have included sector-specific outlets covering issues of interest for a narrow audience, as well as popular science publications for a broader mass of societal actors.

Products and services represent the final category of outputs. While this type of outcome is expected in Vinnova-funded projects, it is considerably less common in this program due to the aims of many projects usually revolving around changing organizational practices and routines rather than creating and implementing new products and services. However, several projects developed digital applications or new types of services for a specific target group or industry. One such example is from the project Expecting a child in Arabic and Swedish! Norm-critical innovative design for interactive antenatal care, where one of the outputs is the mobile app SADIMA that works as a dialogue support in antenatal care. The app is used by midwives in contact with Arabic-speaking women and helps them to inform them about antenatal care in Sweden. Another product that was developed in the project User-driven service innovation for a car independent, inclusive and resourceful waste management system is a bicycle built for transporting bulky waste. This product directly challenged the car norm as well as the services of the municipality who were prone to use the car as the main option for transport services.

A tentative assessment of the impact of norm-critical innovation projects

In this section, we present some of our results that highlight the broader impact of activities and outputs for project participants as well as the broader environment by discussing five projects in more depth further below. Due to the nature of the projects and their duration (one and two years, some still ongoing), this assessment is tentative. However, our data shows that it is possible to detect impacts in at least three areas: Development of new interventions; changes in organizational practices and routines; building capacity for equality and inclusion.

First, we found that activities and outputs that foster reflexivity have been very influential for the re-formulation of the problem space and subsequently for the design of interventions that enable change in a variety of contexts. Interventions were based on the critical examination and engagement in different ways of observing, which in turn lead to different actions. Second, the results of those interventions is most clearly visible in changes of organizational practices and routines, such as new business models, services, innovation processes or internal education. Changing routines might be a starting point for further changes in technologies, policies, and cultural mindsets. Third, our analysis shows that by engaging with and implementing norm-critical principles many projects contribute to building overall capacity for increasing equality and inclusion in their organization. Norm-critical approaches can be both, an analytical method or a hands-on tool for deconstructing limiting norms and developing creative solutions that contribute to societal development. In the coming subchapters, we briefly introduce 5 projects in order to exemplify what kind of impact could be generated through norm-critical reflections and practices.

RIKA 3.0/RICHER: norm-critical innovation in banks’ credit processes

Project description and problem formulation: Both projects are led by the same teams and focus on equal access to public and private funding for entrepreneurs, and on credit assessment algorithms. The background to the project is that banks have been faced with new dilemmas through the digitalization of funding processes. Most small- and medium-sized enterprises are funded privately and by banks, which makes it important that the assessment models based on human decisions and algorithms are built upon norm-critical analyses. Without a norm-critical approach towards the development of algorithms, there is a risk that gender bias will be built into the credit assessment model, which can have a negative impact on women entrepreneurship, emancipation, and the economy as a whole.

Norm-critical reflection: A project member explains the missed opportunities taking place when the funding models are unequal:

The banks are becoming more and more aware that they are missing out on business, because if you talk to the banks about the fact that they are unequal in their assessment process, they completely ignore it, it's not their [concern], instead they are thinking about, are we investing in the right party, do we lend to the right entrepreneurs, do we have the right approach to conduct the best business? When you show that women and men perform equally well and have the same growth and take the same risk, then it is strange that women despite everything don’t have loans, and manage just as well, so then the banks understand that they are missing out, through that insight you can be involved and influence by helping them rather than poking around.

The projects have gained impact on several levels. The research findings gained academic recognition internationally and have been presented at several international conferences, in academic papers and at conferences directed towards banking institutes. The projects have had impact on a strategic level at Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth and have worked closely with major banks by providing knowledge on equality and funding. The project team have expressed that there is a great willingness to improve at the highest management levels in the collaborating banks.

Women on wheels

Project description and problem formulation: Women on Wheels has worked with the objectives of making bicycling accessible and attractive for groups who do not bicycle today and developing services that increase equality within bicycling. To reach these objectives, the project team worked on increasing mobility, improving access to social functions and changing societýs perception of what women should and should not do.

Norm-critical reflection: How do we increase bicycling among traffic-marginalized groups? A project member explains how they struggled with many different grounds of discrimination and therefore shifted focus from gender to norms more generally:

When we started the project, we had a lot of focus on gender and norms which then revolved around women's cycling. We had it as the main norm, the gender norm, when we went into the project and then the longer it went on the more complex it became. Fairly soon, we realized that this is a lot about culture as a norm and that culture is informed quite a lot by ethnicity and religion and so maybe we should position the project in the seven protected grounds for discrimination. Then we started to think about age, for example, there are very big differences in cycling when you look at different connections to different age groups and gender and ethnicity.

In a suburb to Stockholm there was a fairly large group of older women with a non-European background, mainly from the Middle East and Africa, who had very limited mobility. They were transported by their husbands, and they may not have bus passes but instead they walked and moved within a very limited area outside the home. This is transport marginalization and then you could see how a group like this could benefit from the bike being made available to them. The same thing in Indonesia when we map poor groups’ access to various transports – in these areas there are groups that have very low access to mobility and so then it was these groups that we chose to focus on.

User-driven service innovation for a car independent, inclusive, and resourceful waste management system

Project description and problem formulation: The project aimed at challenging the car norm and creating a more inclusive waste management system in a suburb of a middle-sized city in Sweden. Sweden has a very efficient waste management system in large parts due to a high degree of individual waste sorting and a low degree of landfill and incineration. Still, it has been indicated that it is difficult to increase the degree of sorted waste among private citizens and the debate concerning this issue is often focused on the residents’ lack of sufficient knowledge of the waste management system or that they are assumed to be negligent when sorting their waste.

Norm-critical reflection: How do we create a more inclusive and participatory waste management system? A project member describes the norms built into the waste management system:

We have a waste system that is built on the basis of car ownership and car access and also on the basis that those who work in the system are themselves truck drivers who come and collect things, so that their job should be acceptable and good. It is a lot like this, we are going to add this recycling station so that you can get there by truck but it doesn’t really have to be a good place for the residents to easily get to. After all, we built it to make it easy to pick up garbage, not to make it easy to leave garbage.

The whole system thinking, and how easy it is to design for us who own the system, and not for them to use the system, and how important it is with a norm-critical approach and a design practice to be able to access it. Get an understanding of it and be able to actually do something different, not be stuck in a ‘this is bad but well yeah … ’

Norm-creative visualization in city development

Project description and problem formulation: The idea of the project originated in a lack of critical reflection regarding who and what is visualized in concept images, and especially regarding what is not shown in city development. The visualizations are shaped by specific perspectives and experiences, which in themselves presents a worldview of what should or should not be part of a vision of future city development.

Norm-critical reflection: How do we create more norm-inclusive visualizations? A project member describes some of the discussion topics that are part of the handbook that the project developed:

It's a lot about who is seen in the picture? Who makes the space visible and what kind of people are visible in a picture? For example, it can be a person in a certain context that makes it look a little out of the ordinary, for example adding an older man who swings instead of a child. Who is allowed to be seen in this picture and is it only people around who look and act like me, are they white 30 plus, athletic and sitting on an outdoor terrace? Another aspect is changing perspective – from whose point of view, for instance from a wheelchair perspective, or when you have a skate picture there is a lot of focus on the guys, what does the only girl in the picture think, what does this place look like from her perspective? One simply shifts one's own perspective.

Expecting a child in Arabic and Swedish! Norm-critical innovative design for interactive antenatal care

Project description and problem formulation: An exposed group in the Swedish care system is immigrant women, with an increased mortality rate for mother and child during pregnancy and delivery. A study on maternal mortality between the years 1988 and 2010 found several flaws in the healthcare system that affected both Swedish- and foreign-born women, but more so those who were foreign-born. The results show a correlation between maternal mortality and communication barriers. A professional interpreter had not been consistently used, which led to delays in diagnostics and treatment. The issue of using professional interpreters has since the early 2000s been flagged as a necessary step for improvement in maternity care. The project has responded to the problem of communication barriers and developed a mobile app to improve communication between midwives and patients.

Norm-critical reflection: How do we address the problem of communication between midwife and patient? The researchers, the midwives and the Arabic-speaking women for which the mobile app is designed for have different perceptions of what it means to give birth and this is taken into consideration in the development of the mobile app. A project member explains the double reflexivity addressed in their project:

They [the midwives] told us you must have a double reflexivity in this because this is a Swedish way of giving birth to children, we can’t ignore that. […] There is one thing that we realized, which I think is an important thing, when we have studied this and have conducted field studies, and that is, that a parallel care discourse has been created. You might understand that because in Syria you go to a doctor, you don't go to a midwife. Midwives there have very little medical education and they do not have the Swedish specialized [education] at all. This is special in the world because our midwives are allowed to use sharp instruments and so, you don't get that anywhere else. What happens then, for them [the women] to feel, you know this feeling that I have received good care, is that they want one ultrasound every month.

Discussion

The essence of norm-critical innovation practice

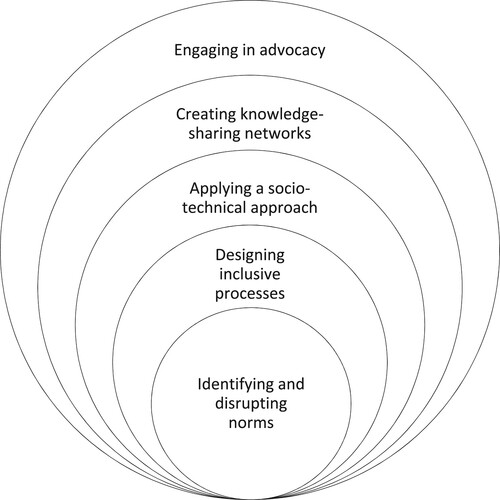

In this paper, we studied how projects funded by Vinnova’s program ‘Gender and Diversity for Innovation’ have put principles of norm-critical innovation into practice and what kinds of activities, outputs, and tentative impacts this has generated. While the 34 projects that we have analyzed in-depth represent a variety of sectors (e.g. health care, urban planning, education, culture and media), actors (e.g. universities, businesses, NGOs, municipalities) and innovations (e.g. digital applications, services, business models, products), it was still possible to identify several commonalities in terms of how project participants practiced norm-critical innovation. We thus argue that our analysis enables to pinpoint the essence of norm-critical innovation practices that can be classified into five main categories: Identifying and disrupting norms; Designing inclusive processes; Applying a socio-technical approach; Creating knowledge-sharing networks; Engaging in advocacy. These categories represent the main characteristics of norm-critical innovation projects, i.e. the essence of what differentiates them from more traditional innovation projects.

At the heart of most of the projects lies the task of identifying and disrupting existing norms. Projects have engaged in several activities (e.g. ethnographic and qualitative methods) and produced a variety of outcomes revolving around this task (e.g. handbooks and toolkits). Frequently, designing inclusive processes was necessary to be able to work with norms. Stakeholder involvement, arenas and interactive spaces for dialogue were a vital aspect of it. However, the co-creation process often went beyond the traditional meetings and instead incorporated the application of a distinctly socio-technical approach. This refers to the very prominent role of visualizations and materialization (e.g. prototypes, exhibitions, living labs) as well as the development of socio-technical solutions which integrate user perspectives, business models and general questions of societal relevance when designing a product or service. Furthermore, norm-critical innovation projects often also to create inclusive knowledge-sharing networks that enhance the understanding of normative issues and contribute to the re-framing of the problem and solution space. In addition, several projects actively engaged in political advocacy and awareness raising among incumbent actors, such as policy makers, professional associations, and large firms. All of these five characteristics are interdependent and can re-enforce each other. In order for projects to attain their aims, it was important to have successful activities and outputs in these five broader categories. provides a comprehensive overview of the categories with their associated activities and outputs from our empirical analysis. is a graphic representation thereof that portrays these characteristics as being nested and layered like an onion as well as interdependent.

Table 5. Five characteristics of norm-critical innovation projects.

We would like to highlight a few particularities of these characteristics. First, it is remarkable how much time and resources went into the development of methods and processes for the identification of norms. While the goal of NCI clearly lies in the disruption of norms through innovation, which is its own challenge, it is not at all a given that the identification of norms, even the excluding and problematic ones, is a straightforward matter. To the contrary, we argue that findings ways to make norms visible and critically examine them can be regarded one of the major contributions of many projects in the program. Besides the time, dialogs, interactions, and collaborations it takes with a diverse range of actors, our results also point to the important role of artefacts, visualizations and holistic experiences in making norms come to life. This is especially crucial when trying to convey exclusion or discrimination to actors that do not experience it to the same extent (e.g. explaining the female experience to men). Provotypes, prototypes, exhibitions or living labs seemed to be a vital resource to express inequality through a more holistic experience that goes beyond language alone. Once there is a general understanding of exclusion also by actors that are not the direct problem owners, it becomes possible to start thinking about alternative futures.

Second, and related to the previous point, is the importance of systemic and socio-technical thinking. The co-evolution of the social and the material and their interdependence with other elements in the system is what makes current structures so stable even if they are problematic, but it is also what will change them. Norms are embedded in many facets of our material life, which is why the creation of new artifacts always brings the possibility of change. Taking a norm-critical approach to innovation thus allowed many projects to think more integrated about the products and services they were to develop, and rarely did we observe the development of a technology that not also entailed a business model or user perspective.

Third, advocacy and the raising of awareness more generally is probably more common in NCI projects that in traditional innovation projects. This is related to the fact that whatever NCI projects aim to achieve or produce, it will be somewhat uncomfortable for the status quo due to the disruptive and challenging nature. It is thus not enough to identify and disrupt problematic norms, but it is equally important to convincing others that there is, in fact, a normative issue at hand and that changing it will have benefits. This kind of advocacy is a time-consuming, but crucial work. Experimenting with powerful storylines and framings as well as different methods of engaging outsiders to experience other realities is thus a vital part of NCI projects.

Norm-critical innovation as a way forward for responsible innovation?

Responsible innovation advocates for anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, responsiveness, and openness in the innovation process in order to achieve desirable social values. At the beginning of the paper, we have raised the issue that because many RI initiatives are set-up as add-ons to innovation projects with the aim to align innovation with societal values, they tend to disengage from proactively contributing to the more fundamental normative change needed for achieving values such as inclusivity, equality or environmental sustainability. We have thus raised the question if NCI and its associated practices could be seen as a way forward to increase the impact of RI principles in practice.

Looking at the results of our study, we argue that the practice of NCI, as we have seen it here, might constitute a tool to operationalize and implement certain RI principles in a more targeted way. The focus on the visualization and materialization of alternative futures through prototypes, simulations, or living labs seems to be a very powerful way to work with anticipation, reflexivity, and responsiveness. Since many normative changes seem impossible and unthinkable at first, it is telling that a lot of NCI projects are situated in settings with a high number of designers, architects or other forms of artists that can visualize current inequalities or exclusions and through that make people experience them that are not usually impacted by them. They are also capable of bringing a vision of the future into some form of tangible reality that triggers discussion and reflection and makes assessments of future impacts possible. The same can be said regarding the application of socio-technical thinking, which forces innovators to be mindful of the systemic impacts of their products and services.

Our results also show a plethora of activities that foster reflexivity, many of which rooted in qualitative methodologies of social science that are not common practice in traditional innovation projects. While many NCI projects have developed guidelines, handbooks, and toolkits for increasing reflexivity, it remains an open question if these outputs are transferrable to other projects and sectors. To our knowledge, only one toolkit, the NOVA card box that entails 52 method cards for norm-creative innovation, has been used across several NCI projects in this program (Alves Silva et al. Citation2016). However, mainstreaming such methodology and applying it at the core of the innovation project, not just as an add-on exercise, could be a starting point to a more impactful implementation of RI more generally.

Furthermore, our results indicate several activities and outputs that enable the design of inclusive processes, in particular referring to the integration of stakeholders and problem owners by setting up participatory and interactive research sites, such as urban living labs, as well as arenas for stakeholder dialogs, courses, and workshops. An important aspect is that communication shall take place through a diverse range of media that goes beyond language in spoken and written form but includes other forms of expressions such as role play, art, physical activity, or films.

From this perspective, NCI accompanies RI schemes that aim to go beyond monitoring innovation processes to integrate and embed inclusive and responsible perspectives in innovation governance. However, NCI practices have the potential to exceed innovation governance if they are placed at the core of an innovation project. Rather than only changing the normative underpinnings for innovation, or aligning the innovation developed by others to societal values, the innovation itself can become a means for normative change. This distinction between innovation process and outcome, which we elaborated on in the chapter two, is an essential one in order to understand the degree of impact that NCI and RI principles can have. We argue that in order for innovation to not only comply with societal values, but also contribute to realizing them, it is vital that the process of creating the innovation as well as the final product is scrutinized through a norm-critical lens. In this way, NCI offers a promising opportunity to go beyond managing the public accountability of innovation and drive the normative change that is needed to increase the contribution of innovation to meeting grand societal challenges.

Although our study illustrates the many useful and powerful activities and outcomes of norm-critical projects, it also reveals some of their limitations. First and foremost, we observed some challenges for projects to move from insight to implementation as well as to generate an impact beyond the boundaries of the project. In our tentative assessment, we mentioned that projects had some success in changing organizational practices and routines as well as generally building up capacity to deal with questions of inequality. However, most of them were very situational and project specific and we currently lack a follow-up study on whether any of those implemented changes lasted beyond project duration. In addition, several of our interviewees have stated that they consider the activities and outputs during the project phase to be the end result and that they have no interest or intention to scale-up or develop their project further. While this might be in line with the description and goals of Vinnova’s program, it is problematic in terms of generating a broader, long-lasting impact. In cases where project participants were interested to continue the work, we observed that it often failed due to a lack of capacity and capability in terms of scaling-up the norm-critical ambition beyond the analytical and prototyping phase. Furthermore, many projects mentioned that as soon as they leave this phase, they run into conflicts with existing regulations and standards and experience a general push-back by incumbent actors. This suggests that there is still a lack of knowledge when it comes to designing and managing the diffusion and implementation of norm-critical innovation beyond project boundaries.

Related to this, it is also telling that Vinnova has created a separate program on NCI innovation, which is small in relation to their other programs, such as the Strategic Innovation Program or Challenge-driven Innovation Program. We argue that in order to make these latter programs comply with RI principles and increase their transformative potential, NCI practices should be fully integrated into them and not run as a niche program on the side. Learning how to integrate NCI practice into mainstream innovation programs can thus be regarded as an essential task for future program design.

Another challenge of norm-critical practice is that it runs the risk of becoming a normative concept in and of itself that dictates how to see and define ‘problematic norms’. On the one hand, many projects use similar methods and approaches, and the researchers are often schooled in related theories of gender, design, diversity, and innovation. On the other hand, the project owners are rarely the ones subjected to discrimination themselves, so they need to make sure to create an active participation of and collaboration with the actual problem owners. This set-up is often a result of the lack of resources and capability on the part of problem owners. However, it does mean that there is a risk of developing yet another top-down definition of inequality. Many of the project teams are aware of this issue and attempt to avert it by involving problem owners and implementing a reflective, situated, participatory approach.

Conclusion

This article presented the findings of an in-depth analysis of 34 projects funded by the Swedish innovation program ‘Gender and Diversity for Innovation’. It explored how norm-critical innovation has been practiced and performed in various empirical settings and whether norm-critical innovation practices could be a way forward for the implementation of responsible innovation.

Our analysis identified the most common project activities and outputs and in so doing carved out the core characteristics of norm-critical practice, which are the identification and disruption of norms, the design of inclusive processes, the application of a socio-technical approach, the creation of knowledge-sharing networks, and advocacy. These characteristics are arguably relevant for the implementation of RI practices, which is why we argue that NCI could be seen as an important building block to foster RI principles in all kinds of innovation processes.

Our findings also offer empirical insights into a novel type of innovation practice that targets societal change rather than economic growth and competitiveness. As such, it bears a lot of potential for addressing societal challenges that go beyond questions of equality and equity. We argue that NCI principles could be applied in all kinds of projects where the aim is to challenge existing systems and where deep-structural change is needed. System change requires a deeper understanding of the norms, values and belief systems that built them. In order to create transformative change, we need to understand and challenge the dominant mindsets. NCI practices might thus be an interesting instrument for fostering all kinds of sustainability transitions and they could also inform future innovation policy that aims at societal or industrial change, such as transformative innovation policy or mission-oriented innovation policy (Schot and Steinmüller Citation2018; Mazzucato Citation2018; Kuhlmann and Rip Citation2018).

Further studies are needed that trace the impact of NCI projects beyond the project duration in order to learn more the mechanism through which NCI enables change as well as to determine how to better support these types of projects in future programs.

Ethics declarations

We confirm that we have obtained appropriate informed consent from the participants of the study. The study has not been subjected to a review by an ethics committee as it does not meet the conditions specified in the Act on Ethical Review of Research relating to Humans in Swedish Law.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lea Fuenfschilling

Lea Fuenfschilling is associate senior lecturer at CIRCLE, Lund University. She holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Basel. She is a member of the board of the Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN) and the platform coordinator of the Swedish Transformative Innovation Policy Platform (STIPP). She has recently been awarded an ERC Starting Grant for the project ‘ENDINGS – Towards a theory of endings in innovation studies’.

Linda Paxling

Linda Paxling is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Design Sciences and CIRCLE, Lund University. Her current research focuses on diversity and inclusive innovation towards more sustainable and inclusive societies in Sweden. She holds a PhD in Technoscience Studies from Blekinge Institute of Technology and a M.Sc. in Culture, Society and Media Production from Linköping University. Linda's research background is in technology design and ethics within the fields Information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) and media technology. Linda also works with cluster development in Tanzania and Bolivia for Sustainability Innovations in Cooperation for Development (SICD).

Eugenia Perez Vico

Eugenia Perez Vico is an Associate Professor in Innovation Sciences at Halmstad University and an affiliated researcher at CIRCLE, Lund University. She holds a PhD in environmental systems analysis from Chalmers University of Technology. Her research interest lies in the area of research and innovation policy with a focus on universities’ collaboration with the surrounding society as well as their impact. She has significant experience from combining scholarly work with hands-on policy development, mainly through her employment at (2005–2013) and collaboration with Vinnova through which she has participated in several Swedish government commissions and working parties at the OECD.

Notes

1 Although RI and RRI are distinct, particularly as RI has attracted more scholarly interest while RRI has drawn the attention of policy (Owen and Pansera Citation2019), we maintain that these concepts are similar concerning aspects of relevance to the scope and aim of this paper. For the sake of readability, we refer to these principles as RI throughout the remainder of the paper.

References

- Aicardi, C., M. Reinsborough, and N. Rose. 2018. “The Integrated Ethics and Society Programme of the Human Brain Project: Reflecting on an Ongoing Experience.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (1): 13–37.

- Alves Silva, M., K. Ehrnberger, M. Jahnke, and Å Wikberg Nilsson. 2016. NOVA Tools and Methods for Norm-Creative Innovation. VR 2016:06. Stockholm: Vinnova.

- Andersson, S., K. Berglund, J. G. Torslund, E. Gunnarsson, and E. Sundin. 2012. Promoting Innovation – Policies, Practices and Procedures. Stockholm: VINNOVA.

- Balkmar, D., and A.-C. Nyberg. 2006. Genusmedveten tillväxt och jämställd vinst: om genus och jämställdhet i ansökningar till VINNOVAs VINNVÄXT-program 2005. Stockholm: VINNOVA. http://pure.ltu.se/portal/files/1027891/Genusmedveten_tillv__xt_och_j__mst__lld_vinst.pdf.

- Bessant, J. 2013. “Innovation in the 21st Century.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 1–25. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Burget, M., E. Bardone, and M. Pedaste. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19.

- Butler, J. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. New York: Routledge.

- Cuppen, E., E. van de Grift, and U. Pesch. 2019. “Reviewing Responsible Research and Innovation: Lessons for a Sustainable Innovation Research Agenda?” In Handbook of Sustainable Innovation, edited by F. Boons and A. McMeekin, 142–164. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Demers-Payette, O., P. Lehoux, and G. Daudelin. 2016. “Responsible Research and Innovation: A Productive Model for the Future of Medical Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 188–208.

- Dunne, A., and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Ehrnberger, K., M. Räsänen, E. Börjesson, A.-C. Hertz, and C. Sundbom. 2017. “The Androchair: Performing Gynaecology Through the Practice of Gender Critical Design.” The Design Journal 20 (2): 181–198.

- Eikeseth, U., and R. Lillealtern. 2013. “Gender Equality for Crash Test Dummies, Too.” ScienceNordic. http://sciencenordic.com/gender-equality-crash-test-dummies-too.

- Felt, U. 2018. “Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Handbook of Genomics, Health and Society, edited by Sarah Gibbon, Barbara Prainsack, Stephen Hilgartner, and Janette Lamoreaux, 108–116 London: Routledge.

- Fraaije, A., and S. M. Flipse. 2020. “Synthesizing an Implementation Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 113–137.

- Freire, P. (1970) 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Friedman, K. 2000, September. “Creating Design Knowledge: From Research into Practice.” In IDATER 2000 Conference (pp. 5–32). Loughborough: Loughborough University.

- Fürst Hörte, G. 2009. Behovet av genusperspektiv - om innovation, hållbar tillväxt och jämställdhet. VINNOVA: VR 2009:16.

- Heltzel, A., J. Schuijer, W. Willems, F. Kupper, and J. E. W. Broerse. 2022. “‘There is Nothing Nano-Specific Here’: A Reconstruction of the Different Understandings of Responsiveness in Responsible Nanotechnology Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2022.2040779.

- Isaksson, A., E. Börjesson, M. Gunn, C. Andersson, and K. Ehrnberger. 2017. “Norm Critical Design and Ethnography: Possibilities, Objectives and Stakeholders.” Sociological Research Online 22: 232–252.

- Krafft, M., A. Kullgren, A. Lie, and C. Tingvall. 2003. “The Risk of Whiplash Injury in the Rear Seat Compared to the Front Seat in Rear Impacts.” Traffic Injury Prevention 4 (2): 136–140.

- Kuhlmann, S., and A. Rip. 2014. The Challenge of Addressing Grand Challenges: A Think Piece on How Innovation Can Be Driven towards the ‘Grand Challenges’ as Defined under the Prospective European Union Framework Programme Horizon 2020. European Research and Innovation Area Board (ERIAB). https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/the-challenge-of-addressing-grand-challenges-a-think-piece-on-how.

- Kuhlmann, S., and A. Rip. 2018. “Next-Generation Innovation Policy and Grand Challenges.” Science and Public Policy 45 (4): 448–454.

- Kumashiro, K. 2002. Troubling Education: Queer Activism and Antioppressive Pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

- Kumashiro, K. 2015. Against Common Sense: Teaching and Learning Toward Social Justice. New York: Routledge.

- Lindberg, M. 2010. “Samverkansnätverk för innovation: en interaktiv och genusvetenskaplig utmaning av innovationspolitik och innovationsforskning.” PhD diss., Luleå University of Technology.

- Levitas, R., C. Pantazis, E. Fahmy, D. Gordon, E. Lloyd-Reichling, and D. Patsios. 2007. The Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Social Exclusion. Bristol: University of Bristol.

- Mazzucato, M. 2018. Mission-oriented Research & Innovation in the European Union. Brussels: European Commission.

- Nilsson, A. W., and M. Jahnke. 2018. “Tactics for Norm-Creative Innovation.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 4 (4): 375–391.

- Nyberg, A.-C. 2009. “Making Ideas Matter: Gender, Technology and Women's Invention.” PhD diss., Luleå University of Technology.

- Owen, R., and M. Pansera. 2019. “Responsible Innovation and Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Handbook on Science and Public Policy, edited by Dagmar Simon, Stefan Kuhlmann, and Julia Stamm, 26–48 Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Owen, R., J. Stilgoe, P. M. Macnaghten, M. Gorman, E. Fisher, and D. Guston. 2013. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 27–50. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Owen, R., R. von Schomberg, and P. Macnaghten. 2021. “An Unfinished Journey? Reflections on a Decade of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 217–233.

- Pansera, M., R. Owen, D. Meacham, and V. Kuh. 2020. “Embedding Responsible Innovation Within Synthetic Biology Research and Innovation: Insights from a UK Multi-Disciplinary Research Centre.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 384–409.

- Schot, J., and W. E. Steinmueller. 2018. “Three Frames for Innovation Policy: R&D, Systems of Innovation and Transformative Change.” Research Policy 47 (9): 1554–1567.

- Stahl, B. C., S. Akintoye, L. Bitsch, B. Bringedal, D. Eke, M. Farisco, Karin Grasenick, et al. 2021. “From Responsible Research and Innovation to Responsibility by Design.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 175–198.

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42: 1568–1580.

- Sykes, K., and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Responsible Innovation – Opening up Dialogue and Debate.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 85–108. London: Wiley.

- Urquhart, L. D., and P. J. Craigon. 2021. “The Moral-IT Deck: A Tool for Ethics by Design.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (1): 94–126.

- van Mierlo, B., P. J. Beers, and A.-C. Hoes. 2020. “Inclusion in Responsible Innovation: Revisiting the Desirability of Opening Up.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 361–383.

- van Oudheusden, M. 2014. “Where are the Politics in Responsible Innovation? European Governance, Technology Assessments, and Beyond.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 67–86.

- von Schomberg, R. 2012. “Prospects for Technology Assessment in a Framework of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Technikfolgenabschätzen lehren: Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methoden, edited by M. Dusseldorp, and R. Beecroft, 39–61 Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Von Schomberg, R. 2013. “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 51–74. Chichester: Wiley.

- Wahl, A., C. Holgersson, P. Höök, and S. Linghag. 2011. Det ordnar sig alltid: Teorier om organisation och kön. Lund: Studentlitteratur.