ABSTRACT

The operationalisation of Responsible Research and Innovation is increasingly associated with ethical toolkits. However, scholars remain critical of those toolkits, often referring to them as theoretically problematic, toothless, or too instrumental. Moreover, toolkits imply ideological commitments that are not necessarily made explicit. In this scoping review, we analyse 127 tools designed for technology ethics as part of the RRI Project. We find that (1) these tools tend to frame responsibility as general training or aimed at the development phase of technologies, while monitoring is underrepresented. (2) These toolkits often lack substantive conceptualisations of ethics ignoring contested paradigms. (3) Emerging digital and biotechnologies are over-represented in relation to other socio-technical infrastructures, and (4) there is a risk of a PDF-ization of ethics, as most toolkits are materially constructed as reading material and checklists. We conclude by presenting prompt questions to reflectively reconsider how we design ethical toolkits for technology.

Introduction

Ethical toolkits have become essential tools for putting Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) into practice and ensuring the legacy of funded projects (Buchmann et al. Citation2023; Stahl and Bitsch Citation2023). This is partly because the study of the intended and unintended consequences of technologies is usually accompanied by the expectation that it should be at some point translated into useful tools for the benefit of science and technology governance (van Lente, Swierstra, and Joly Citation2017). However, in practice, applied technology ethics principles have been described as ‘abstract and toothless’ (Green Citation2021, p. 212), often adopting an overly individual focus on ethics that is subsumed into corporate logics and incentives (Green Citation2021). Moreover, in organisational settings, it is often the case that companies develop novel technologies first and try to understand how to fit them into ethical principles and standards second (Ibáñez and Olmeda Citation2022). Companies themselves agree that there is a gap between practice and principles of technology ethics (Ibáñez and Olmeda Citation2022).

Broadly speaking, technology ethics is a specific application of moral philosophy or ethical theory (Copp Citation2007) to the field of technology. Ethical theory is a historically and conceptually rich field of philosophical thought in which ideas of deontology, value ethics, consequentialism, and ethics of care among other grand ethical theories are debated and contested (Copp Citation2007). However, current discourse around applied technology ethics is better described as a sort of ‘practising ethics’, understood as social research used to ‘capture the practices of doing ethics in R&I [research and innovation] under consideration in their broadest possible sense’ (Reijers et al. Citation2018, p. 1438). In this sense, discourse around applied technology ethics tends to focus more on social practices rather than philosophical debates.

The problem of the application of technology ethics goes beyond an adoption gap and into the operationalisation of ethics itself. Methods and tools used to operationalise technology ethics often rely on a checklist approach and formalised steps that reify ethics into fixed rules, and ignore how technologies can help to shape new forms of morality (Kiran Citation2012). Moreover, these checklist style tools typically involve universalistic ethical frameworks that overlook how the cultural context can help to explain and address unforeseen and unanticipated ethical consequences (Kiran Citation2012).

This ‘cultural’ critique can be further strengthened by the fact that technology produces different types of impact (Boenink, Swierstra, and Stemerding Citation2010). Hard impacts (i.e. those usually associated with risks to the environment, health or safety) range from exposure to biohazards, to risking personal rights, to privacy. However, technology can also affect our cultural norms, moral routines and subjectivation processes (soft impacts). These impacts are often underrepresented in social discourse and are framed in such ways that they seem to be outside the sphere of control of technology creators and administrators (Jasanoff, Citation2016).

The framework of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’ (RRI) can be interpreted as a social and conceptual critique to previous Technology Assessment (TA) methods that have downplayed the normative aspects of technology (van Lente, Swierstra, and Joly Citation2017). However, without careful critical reflection it is not clear that it will necessarily overcome the challenges of operationalising ethical principles into culturally sensitive, ‘toothed’ tools for practice. In fact, some researchers are sceptical of standardisation of RRI through ‘toolification’ (Völker et al. Citation2023), as transformation of practices are always negotiations with pre-existing institutional orders and relationships. In this sense, the very idea of toolkits is contested in RRI.

For context, ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’ (Owen et al. Citation2013) has arisen as a framework in which scientific research and technology development ought to take responsibility for its social consequences. In general terms, this means the responsibility to avoid ‘harm’, the responsibility to do ‘good’ and the responsibility to govern technology development in ways that achieve both those goals (Voegtlin and Scherer Citation2017). Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) is often centred around the guiding principles of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness throughout the innovation process (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). A review conducted by Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste (Citation2017) suggests that the principles of care and sustainability have also been at the centre of responsible innovation literature. Historically speaking, RRI has extended and dominated policy discourses of technology ethics (Stahl et al. Citation2014) and established a dialogue between humanities and social sciences to address the ethical and social implications of technologies (Stahl et al. Citation2021). In this sense, RRI also captures the normative turn in Science and Technology Studies (Lynch Citation2014) that seeks to turn sociotechnical analysis into advice about ‘right thing to do’.

RRI is not the first conceptual framework aimed at incorporating ethics in technology development. As mentioned, it can be understood as a response to previous institutional attempts, such as Technology Assessment (TA) or the Ethical, Legal and Social Aspects (ELSA) framework for emerging sciences and technologies (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). As van Lente, Swierstra, and Joly (Citation2017) have argued, RRI should not be necessarily interpreted as a continuation of TA, but rather as a critique on the basis of arguments for stakeholder involvement and against the downplaying of normative aspects of technology. In this sense, it stems more directly from the idea of ‘anticipatory governance’ (Guston Citation2014), broadly understood as a societal capacity to use multiple perspectives in order to govern emergent technologies while they are still governable (Guston Citation2014). At its best, responsible innovation has the potential to unify and provide political momentum to a longstanding tradition of ethical concerns about technology policy (Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar Citation2017).

In practice, responsible innovation has been implemented through changes in regulatory and technological governance practices, such as the EU Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) policy built into the Horizon 2020 programme (de Saille Citation2015). The Horizon 2020 programme incorporated RRI as an overarching theme and operationalised it through six ‘keys’, namely, public engagement, open access, gender, science education, governance, and ethics.

Responsible innovation can also have a more ‘educational’ implementation, through the monitoring of responsible innovation practices and the development and dissemination of ‘tools’ (Genus and Iskandarova Citation2018). These tools are designed to help practitioners embody the sort of moral values and/or specific social behaviours promoted by responsible innovation literature. Overall, responsible innovation typically aims at public engagement, encouraging researcher reflection, dealing with legal/ethical consequences and institutionalising responsibility through policy (Schuijff and Dijkstra Citation2020). Responsible innovation research started with concerns about emergent technologies, such as nanotechnologies, biomedical, geoengineering and information technologies (Genus and Iskandarova Citation2018). However, researchers have sought to broaden its scope to include the development and implementation of technologies within a wider spectrum (Genus and Iskandarova Citation2018).

Despite its apparent growth in popularity, the implementation of responsible innovation has its limitations. Without critical awareness, responsible innovation runs the risk of serving as virtue signalling without substantive results (de Hoop, Pols, and Romijn Citation2016). The risks are especially high when factors such as power differences, vulnerabilities and conflicting interests are not accounted for (de Hoop, Pols, and Romijn Citation2016; Kerr, Hill, and Till Citation2018). On the other hand, responsibility is typically incorporated through tools defined as complementary or additionally steps, not as a foundational aspect of design processes (Hernandez and Goñi Citation2020). In this sense, responsible innovation has not substantially altered how practitioners conceive the design process itself (Hernandez and Goñi Citation2020), that is, the common sequence of procedures used to conceive design solutions.

This is particularly critical as responsible innovation literature has emphasised a processual view of responsibility more than an outcome-based view (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). In other words, more attention is supposedly given to how emergent technologies are governed through responsible processes than to achieve certain societal outcomes. Nonetheless, accusations of ‘ethics washing’ by scholars have highlighted the way ethics is narrowly operationalised into tools (Bietti Citation2020). Ultimately, there is a need for a more critical approximation to the idea of ‘tools’, especially because as Wong, Madaio, and Merrill (Citation2023) put it: ‘toolkits, like all tools, encode assumptions in their design about what work should be done and how’. As cultural-historical psychologist Lev Vygoysky (Citation1987; Vygoysky Citation1997; Wertsch Citation1985) argued, this sort of psychological tools mediate behaviour in ways that not only regulate it, but that also shape our understanding of the world itself.

In sum, the growth in interest around technology ethics toolkits has been followed by controversy around its potential for narrow operationalisation and ethics washing. Yet, no systematic review of the different available tools exists in the literature that would allow critics to assess the extent to which these problems are reflected in the majority of the publicly available tools. Against this background, our research question is: How is technological responsibility addressed in the current landscape of publicly available RRI tools? In that sense, our study seeks to ground the current scepticism about the operationalisation of technology ethics through toolkits in a more systematic review and comparison of the available tools.

More specifically, in this article, we conduct a scoping review (Arksey and O‘Malley Citation2005) and discuss the implementation of responsible innovation through the development of ‘tools’. In particular, we review the RRI tools compiled as part of the RRI Tools project, the largest publicly available repository of tools for responsible innovation.

The RRI tools project

This project (https://rri-tools.eu/) was funded by the European Union and ‘la Caixa‘ Banking Foundation in Spain to advance RRI throughout the EU under Horizon 2020 (Groves Citation2017). Its goal was to assemble and curate in an online portal a vast set of educational resources designed to promote responsible innovation by different stakeholders (Groves Citation2017). Overall, the project hosts a wide range of educational resources (García, Zuazua, and Perat Citation2016, p. 3):

Library elements to inform on RRI and its various facets;

Projects on RRI and closely related fields to build upon and collaborate with;

Good practices to inspire and adapt in various contexts; and

Tools to plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate a more socially responsible research and innovation.

According to the project‘s coordinators, tools are

intended to help users implement specific actions on a particular topic, such as designing and putting in practice a plan to generate structural change in an institution, selecting a participatory method to conduct an activity, or deciding in which open repository should be published the data and results of a project (García, Zuazua, and Perat Citation2016, p. 14).

Methodology

In this article, we adapt Arksey & O‘Malley‘s (Citation2005) process for scoping reviews. Scoping reviews are a form of academic aggregation or synthesis. Contrary to systematic reviews, in scoping reviews no pre-determined analysis criteria are expected, as the purpose is to map the body of work, rather than to respond to an empirical question (Arksey and O‘Malley Citation2005). In this sense, as a mapping effort, scoping reviews are helpful for revealing key factors and underpinning concepts on a topic of interest (Munn et al., Citation2018), and in doing so, helping in the creative reinterpretation of the material (Levac, Colquhoun, and O‘Brien Citation2010).

Arksey and O‘Malley (Citation2005) suggest the following five steps in structuring a scoping review.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Stage 3: study selection

Stage 4: charting the data

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

In the following sections, we describe each of these stages. Although originally designed for academic articles, previous research has already shown the applicability of this framework for mapping practical toolkits (Barac et al. Citation2014). In this work, we extend that effort by looking at non-academic repositories of toolkits that more closely reflect communities of practice.

Identifying the research question

The main research question of this article is: How is technological responsibility addressed in the current landscape of publicly available RRI tools?

This question was framed in a broad way to fit the overall mapping aspirations of scoping reviews (Arksey and O‘Malley Citation2005). Through this question, we seek to explore how responsibility is ‘designed’ or conceived by RRI tools and describe how their intended audiences and technological concerns are presented and justified. Specifically, we operationalised the main research question of our study into four guiding questions (Kross and Giust Citation2019):

When does responsibility end?

What do designers mean by ethics?

What emerging technologies are worrying designers the most?

How is responsibility materialised?

Identifying relevant toolkits and toolkit selection

To our knowledge, RRI Tools is the single largest compendium of publicly available technology ethics toolkits. Additionally, we selected the RRI Tools as our primary source of data, because it was collaboratively developed with communities of practice and large civil society organisations (Groves Citation2017), thus providing some evidence of closeness to actual use. However, it must be stated that other repositories exist, also providing access to toolkits made by relevant communities of practice.

Some compilations have been made by private companies working in corporate responsibility. For instance, Tethix (https://tethix.co/ethics-tools-directory) provides a directory of tools, but by the time of writing this article only contains less than five self-described toolkits. Other third sector organisations have also produced alternatives, like for instance the Ethical Design Resources website (https://www.ethicaldesignresources.com/), or the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (https://oecd-opsi.org/toolkits/), but these are not oriented specifically towards technology ethics nor are they intended for a wide variety of users. Nonetheless, it is clear that selecting a specific database, in our case the RRI Tools, involves possible selection biases. For instance, since the RRI Tools is an EU-funded initiative, it is likely that we are overlooking relevant contributions from the Global South. With those limitations in mind, we assert that this review within the RRI Tools project can only be interpreted as a good representation of a particular RRI environment, which is mainly European.

The RRI Tools project provides a search engine with different filter options. This design structure allows for a review of the tools in a systematic and traceable manner. shows a screenshot of the site at the time of writing this article.

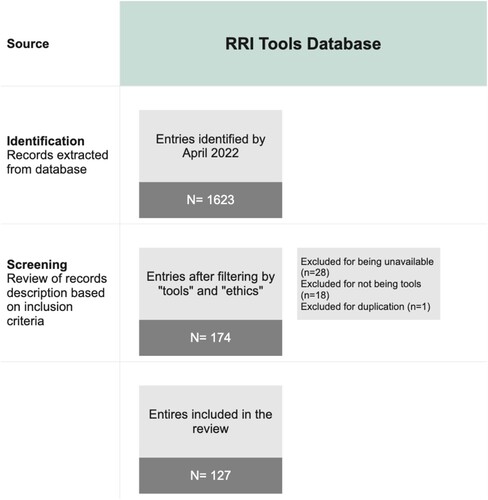

Our review took place from September 2021 to April 2022. By that time, the platform counted 1623 contributions made by the community.

To comply with the main objective of the article, we filtered projects that were flagged as ‘tools’ as well as addressing ‘ethics’. After the first filtering process, the database produced 174 entries.

In a second filtering process, we reviewed each abstract and its details one by one using the following inclusion criteria:

Being related to either research or innovation.

Being a tool in itself (that is, excluding search engines or RRI databases).

Having available information and working links to the source material.

Charting the data

To map the data we adopted a ‘descriptive-analytical’ approach (Arksey and O‘Malley Citation2005). This approach involves developing a common framework to organise the data and collecting standard information on each toolkit. Thus, each toolkit was analysed in a matrix comprising the following variables: year of publication, abstract, declared purpose or objective, intended user, definition of ethical concepts, technology involved, and cost. This information was extracted verbatim from the available links. In the case of definition of ethical concepts, we looked for verbatim descriptions of what was meant by ethics, responsibility or related concepts. In the case of the technology involved, we registered when a specific technology was identified as the main focus of the tool in the purpose statement. Additionally, two interpretative variables were introduced: tool type (describing the materiality or general form of use of the tool) and time of usage (describing at what point of the research and innovation process it is used). These variables were manually labelled by the research team, and discussed in team meetings to enhance investigator triangulation (Flick Citation2020).

The types of tools identified were the following:

Compilations and Lists (collections of cases, good practices, or other tools)

Guides (documents stating procedures or standards)

Application/App (software programme designed to run on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets, or on desktop computers)

Physical (printable content, such as worksheets, card games, board games, or other materials designed for non-digital use)

Multimedia (content that combines multiple forms of media, such as text, audio, images, video, or interactive elements)

Course (Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), or other educational offerings)

Preparation / formation: Tools aimed at training the user in key ethical principles and at identifying the main existing risks in the field of research and innovation ethics. They usually help to avoid breaching ethics principles but are situated beyond the actual research and innovation process.

Development: These tools are aimed at providing support for the user during the development of a new research or innovation project.

After delivery: These tools are aimed at measuring and reflecting on the impact of already developed research and technology.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

To re-interpret and discuss the toolkits, we followed a three-step reporting strategy similar as the one proposed by Arksey and O‘Malley (Citation2005). First, we attend to the basic numerical distribution of information across the identified comparison dimensions (Arksey and O‘Malley Citation2005). In practice, this involves descriptive analyses that can be summarised in frequency tables or mapped in visual graphs (Lehoux et al. Citation2023).

Then, we present exemplary cases of toolkits that illustrate the category. Examples and exemplary cases are a common feature of social research that help to showcase and communicate specific features of the social world (Morgan Citation2019). In this case, and following the principle of constant comparison in interpretive research (Boswell, Corbett, and Rhodes Citation2019), we provide examples of dominant categories, as well as minority categories in the data frame. Toolkits selected as examples were chosen for their quality as ‘typical’ or ‘representative’ cases of their category, drawing inspiration from the general guidelines of case-based research (Yin Citation2012). Exemplary cases were discussed in team meetings in order to generate investigator triangulation (Flick Citation2020).

Finally, each comparative dimension is discussed and re-interpreted drawing narratively from the scholarly literature on RRI and Science, and Technology Studies. Drawing from an interpretivist framework (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2013; Yanow Citation2014), we are able to reconnect the descriptive analysis with the analytical research question of this study. In order to make the connection more transparent, the Results section (below) is organised according to the guiding questions of the study.

Results

When does responsibility end?

We identified that 69 out of the 127 tools (55%) are to be used at preparation / formation stage. This means that they aim at educating or training the user in terms of personal judgment but beyond the actual process of developing a new innovation or research. For instance, the Awful AI is a curated list that tracks misuses of AI organised around the following topics:

Discrimination

Influencing, disinformation, and fakes

Surveillance

Social credit systems

Misleading platforms, and scams

Autonomous weapon systems and military

Awful research

Considering the development stage, 54 out of the 127 tools (43%) target this level. This means that they provide support for users in the process of researching and innovating. Finally, only three tools are planned to be used once the delivery or development of the new research or innovation has taken place. For instance, the FRR Quality Mark for Robotics and AI (https://rri-tools.eu/-/frr-quality-mark-for-robotics-and-ai) is a consumer label certifying that a product has been evaluated by an independent external expert group on responsible robotics. In this sense, this tool follows products after they have been produced, and monitors their impact on their intended users. While the Awful AI and FRR Quality Mark both deal with existing technologies, their purpose within the innovation process differs. Awful AI aims at a broader social conversation through illustrative cases, while the FRR markings can be interpreted as a follow-up step after the innovation process of robotics and AI products.

Overall, these results point to the inclusion of ethics when the product is being developed without enabling critical reflection once the product is being used and has been diffused into ordinary life. This may reflect an intended (or unintended) consensus in the toolkits about responsibility ending the moment the product is delivered. Without considering how technologies change in practice, important emergent information might be missed. Looked at from the general framework of RRI, this could be seen as a breach in the fundamental principle of ‘responsiveness’, understood as ‘responding to new knowledge as this emerges and to emerging perspectives, views and norms’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, p. 1572).

In a sense, the predominant focus of preparation and formation could be indicative of the intent to keep innovators reflexive and responsive throughout the innovation process. However, training per se does not equate to the development of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (Monsonís-Payá, Iñigo, and Blok Citation2023). Monitoring involves the constant study and learning from artefacts as they are transformed once in use in ways that are relatively unpredictable during their inception (Hernandez and Goñi Citation2020).

This finding is consistent with previous literature criticising the design-centred approach to technology studies in which the importance of the transformation of technology during its use and diffusion is often underemphasised (Stewart and Williams Citation2005; Williams Citation2019). For instance, Fleck (Fleck Citation1993) coined the term ‘innofusion’ to describe how innovation occurs during the diffusion of new technologies. Other concepts and frameworks such as ‘domestication’ and ‘appropriation’ have also been employed to similar effect in order to assert the role of users in participating in the mutual shaping of technology (Williams Citation2019).

More recent work, for instance, the model of Value-Sensitive Design developed by Batya Friedman (Friedman Citation1997; Friedman et al. Citation2013; Citation2017) has devoted special attention to the processes of validating and empirically verifying the ethical implications of artifacts after their integration in current socio-technical systems. The Value-Sensitive Design model also expands the notion of design: design is thought of as a circular endeavour with no essential end point when it comes to responsibility. Alternatively, Hernandez and Goñi (Hernandez and Goñi Citation2020) have also proposed an ‘extended design’ model which calls for the constant revisiting of the design process through the monitoring of artifacts in use, based on the practical impossibility of fully anticipating the actual implications of new designs. Of course, a single agent (for example, technology companies) would have a hard time supporting a continuous process of monitoring and learning. For this reason, Hernandez and Goñi (Citation2020) assert that extended design involves extending responsibility as well. As the authors state: a distributed monitoring could involve individual users, communities, NGOs, Universities, and even governmental agencies depending on the complexity of the project (Hernandez and Goñi Citation2020, p. 14). This is consistent with the general push of RRI to frame responsibility as a collective process (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012).

These bodies of literature from technology studies point out the limitations of existing tools that do not illuminate how to scaffold (Wood, Bruner, and Ross Citation1976) responsibility after technology has been diffused into ordinary life. In this sense, how RRI is currently operationalised through toolkits is a challenge that will have to be addressed.

What do designers mean by ethics?

In our review, we observed that 77 toolkits (61%) did not define what frameworks underpin their usage of concepts such as ethics and responsibility. In some cases, although no specific frameworks or definitions were elaborated, a clear positioning can be inferred based on the toolkits’ design or characteristics. For instance, the Peer Review Card Exchange Game (https://rri-tools.eu/-/the-peer-review-card-exchange-game-that-can-be-used-as-an-introductory-activity-for-teaching-integrity-and-ethics-in-peer-review-training), is a tool that uses a card-based method to teach and train editors in peer review processes. For that task, the developers propose a series of discussion statements according to the following themes:

Responsiveness

Competence

Impartiality

Confidentiality

Constructive criticism

Responsibility to science

Other toolkits offer specific definitions, but they appear to lack a clear connection to ethical frameworks and literature. For instance, the Data Ethics Canvas (https://rri-tools.eu/-/the-data-ethics-canvas) gives a clear assertion of what ethics means in the context of that tool: ‘Ethics helps us to navigate what is right and wrong in the work we do, the decisions we make and the expectations we have of the institutions that impact our lives’. This definition opens more questions than those it addresses, as the definitions of right and wrong will greatly differ in different ethical traditions (Pirtle, Tomblin, and Madhavan Citation2021). For example, Vallor (Citation2016) has argued for the centrality of value ethics for technology ethics and operationalised ‘technomoral wisdom’ in terms of transversal human values such as honesty, courage and care. This perspective is different than the ones from posthumanists that propose a decentring from the ‘human’ as the main focal point (Nath and Manna Citation2021).

Finally, there are toolkits better focused on ethical frameworks. This is the case with tools that are based on the RRI framework itself, such as the NewHoRRIzon Societal Readiness (SR) Thinking Tool and the TERRAIN tool for teaching responsible research and innovation. The NewHoRRIzon Societal Readiness Thinking Tool (https://rri-tools.eu/-/the-newhorrizon-societal-readiness-sr-thinking-tool) states: ‘At its core, responsible research and innovation (RRI) is about aligning scientific knowledge production with broader societal needs and expectations. It confers new responsibilities on scientists by committing them to reflect carefully upon the societal implications of their work. Building on key contributions in the RRI literature, the thinking tool distinguishes two interrelated approaches to responsibility: conditions and keys’. This definition does seem to provide more insight for users in terms of the foundations of its design, but not much nuance regarding the designers’ ethical and political assumptions is offered. As Sengers et al. (Citation2005) argue, there is a need for a more reflective design that brings to light the intricacies of the designers’ values which end up propagating into our decisions.

Overall, these results point to a seemingly disconnect between the literature on ethics and the documentation of the toolkits. This, in turn, impacts the ability of users to understand the underlying assumptions that have guided the design decisions behind the toolkit and its theory of change.

What emerging technologies are worrying designers the most?

Most toolkits are either focused on basic research or aim at a broad spectrum of technological applications. Yet, when a particular technology was singled out in a toolkit‘s purpose statement, it was almost always referring to a digital technology (26 entries). Specifically, most tools directed at technology tackle the issue of Artificial Intelligence (AI) ethics. Examples of this are The Business Case for AI Ethics, Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI, and ALTAI – The Assessment List on Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. These types of tools aim at integrating ethics, trust and transparency into the application of AI in diverse settings.

According to Vinsel and Russell (Citation2020), the dominance of the ‘digital’ in technology discourse is ubiquitous. It has permeated our very conception of technology by its association with the notion of ‘tech’ as a synonym of digital applications. When public opinion and media refer to ‘big tech’ or ‘tech startups’ they are primarily referring to digital technologies (e.g. Google, Uber, Facebook). And, this association tends to overlook the relevance of our non-digital infrastructure. As Vinsel and Russell (Citation2020) argue:

it‘s misleading to use “tech” as a proxy for “technology.” The term is too narrow. Technology, as a human phenomenon, is much broader and deeper—it encompasses all of the materials and techniques contrived by human civilization, including non-digital technologies such as guns, sidewalks, and wheelchairs. When we reduce “technology” to “addictive digital devices and their applications,” we discount thousands of years of ingenuity and effort, and needlessly focus our attention and resources on a very small band of human experience (p.42).

Overall, the dominance of the digital is clear. This is followed by concerns regarding healthcare and health-related biotechnologies. It would be interesting to further explore what technologies are not made visible by these toolkits. As a governance framework, RRI was developed to tackle emergent technology through anticipation (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013b). However, not all emerging technologies produce the same amount of media hype, and that does not mean we should not aim to anticipate them responsibly as well (Bareis, Roßmann, and Bordignon Citation2023). There are exciting new developments in many areas of work beyond digital and biotechnologies, that new tools could help visualise. These range from vertical farming, to arcology, to new optoelectronics, bioplastics or airless tyres.

On the other hand, the RRI toolkit community should also be mindful of not blindly reproducing a culture of novelty and disruption, without sufficient attention to care. Since its origin, RRI has pushed for a ‘kind of innovation that privileges collaboration, empathy, humility and care’ (Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021, p. 228). Yet, the ethics of care are widely recognised as activities of repair, maintenance and continuation (Tronto Citation1993). In this sense, RRI practitioners should reflectively ‘balance the hype for novelty with a culture of maintenance, repair and recycling’ (Joly Citation2019, p. 36).

How is responsibility materialised?

The various toolkits differ in the way they intend to implement ethics in the research and innovation process. This ranges from checklists (e.g. COMPASS responsible innovation self-check tool), online search engines (e.g. Ethics Tools and Techniques Directory), card-based games (e.g. Cards for the Future), guides (e.g. Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI), manuals (e.g. KARIM Responsible Innovation Criteria) and Apps (e.g. The Dilemma Game: Professionalism and Integrity in Research).

As stated in the methodology section, we identified six different types of tools in this review. The distribution of entries in these categories is the following:

As shows, the majority of tools can be classified as ‘Guides’. In practice, most of these guides are PDF files displaying information about a topic related to RRI. For instance, the tool AI Ethics: What Leaders Must Know to Foster Trust and Gain a Competitive Edge is a 9-page document with information for strategic arguments for AI Ethics in a corporative setting. In fact, 25 entries are PDF files (about 1/5 of total entries).

Table 1. Distribution of entries per type of tools.

Besides informational PDFs, some PDF-based guides are ethical checklists. The Academic Integrity Checklist, the COMPASS Responsible Innovation Self-Check Tool, the Recommended Checklist for Researchers, the Responsible Innovation Diagnosis in ICT, or the In Fieri Assessment Tool for Responsible Innovation in Health, constitute good examples. In these tools, ethics are parametrised in discrete options aimed typically at assessing processes or guiding self-reflection. This observation is consistent with previous reviews in AI Ethics showing the prevalence of documents and checklists as the dominant operationalisation of impact assessment (Ayling and Chapman Citation2022). Still, as Rességuier and Rodrigues (Citation2020) argue, this ‘legalistic’ view is, in part, responsible for the shared feeling of ‘toothless’ technology ethics. As they assert, ethics tools should allow for ever-expanding critical thinking and a ‘continuously renewed process of questioning the world’ rather than just deontic pre-defined outcomes.

In contrast, other tools are designed in a way that engage the users in a more active manner. That is the case of card-based games such as IMAGINE RRI | A card-based method for reflecting on responsibility in life science research (https://rri-tools.eu/-/imagine-rri-a-card-based-method-for-reflecting-on-responsibility-in-life-science-research); or the simulation game The Lab: Avoiding Research Misconduct | Interactive Movie on Research Misconduct in which the user is presented with ethical scenarios, chooses a character to play, and makes active decisions. This pathway seems to promise a more complex, situated and evolving view of ethics in which there is no pre-defined view of a correct answer. Additionally, as constructivist psychology has extensively argued (Piaget Citation1976; Vigotsky Citation1987), people need active interpersonal interaction in order to truly change their cognitions. In this sense, just reading PDFs is, at face value, not sufficient scaffolding to support profound learning experiences.

Overall, these findings highlight the risk of ethics being operationalised either as a passive activity or as being based in bureaucratic designs, such as checklists and informational documents. In other words, there is a risk that these tools promote the ‘PDFization’ of ethical reflection, in the sense that they may encourage a reductionist parametrisation or inadequate support for enhancing critical thought.

If we need tools to produce and sustain critical thought about the ethical impact of technology, it is because it is hard to make abstract ideas of responsibility engaging and concrete (Tomblin and Mogul Citation2020). Yet, it is equally hard to imagine how reading a PDF checklist or ‘tips’ could facilitate that learning process. Designers of ethics tools should, therefore, be mindful of how effective their scaffolding is in helping people navigate the cognitive and affective difficulties of conceptual change. This concept, coined by Wood, Brunner and Ross (Citation1976) and inspired by psychologist Lev Vygotsky argues that learning involves more than observing and being transmitted information. On the contrary, learning requires external cultural and social support structures that actively help, feedback and motivate the transformation of cognition (Wood, Bruner, and Ross Citation1976). In that sense, toolkit designers would benefit from experimenting and engaging with more complete scaffolding techniques that address the cognitive, affective, and motivational dimensions of learning.

Discussion

Ethical tools are increasingly seen as a central component of the governance of technology, especially because previously dominating ethical frameworks are now considered too abstract and difficult to translate into practice (Prem Citation2023). However, toolkits are now criticised for they risk they pose of offering too narrow an operationalisation of responsibility and ethics washing. In that sense, more critical analysis is needed to consider under what conditions can a tool-based approach to technology ethics overcome those criticisms and create substantive impact in practice. In this article, we reviewed the largest online repository of responsible research and innovation toolkits, the RRI Tools Project. Throughout our review, we found that:

Responsibility is primarily framed as formation/preparation and focused on the development phase, while the monitoring and learning from technology already in use is underrepresented.

Toolkits tend to lack substantive conceptualisations of ethics. In so doing, their theories of change become weaker for the purpose of driving action in a world of contested paradigms.

Emerging digital technologies and biotechnologies dominate discourses of technology ethics, while other essential technologies of our socio-technical infrastructures tend to be overlooked.

There is a risk of promoting the PDF-ization of ethics, as most toolkits are materially constructed as reading material and checklists. This reinforces the view that current approaches are legalistic and lacking interactivity.

STS scholars have a crucial role to play in collaborating with communities of practice in the development of an in-built reflexive ethos (Nowotny Citation2007) when it comes to the operationalisation of ethical principles. A similar phenomenon occurred in Public Engagement with Science and Technology (PEST) when a reaction to the so-called deficit model drove a plethora of dialogue initiatives, most of which failed to avoid the pitfalls of deficit (Simis et al. Citation2016). Because of this, Irwin (Citation2021) suggested the development of a third-order thinking (after deficit and dialogue) that emphasises critical reflection and reflection-informed practice about the wider cultural and political context of participation, while also acknowledging and confronting uncertainty.

Just like Irwin‘s (Citation2021) suggestion of a third-order thinking does not equate to prescribing a new and defined set of governance practices, our call for reflection is not a call for a checklist on how to design better toolkits. A new ‘thinking order‘ of technology ethics tools should support communities to delve into deeper questions about the design of toolkits rather than to offer off-the-shelf tools for tool-making. Some of the questions we have asked in this review may serve as a starting point but they are not, by any stretch, definitive. These questions are: how is responsibility framed, for who and by whom? what are the ethical underpinnings of toolkits and what is their theory of change? what technologies are being paid attention to and what are being overlooked? how is learning being supported and materialised?

We hope our review incites more conversations about toolkits and the logic of tooling with ethics. However, our own work is not without limitations. Firstly, we are aware that there are other repositories of tools and toolkits that represent other communities of practice. Our choice of repository likely over-represents European epistemologies and geographies. Secondly, our review is time-bounded. By the time this review is read, more and different toolkits will have been developed and made available, likely addressing some of the concerns we have expressed here. Finally, our review did not include the contextual elements of the toolkits, limiting the scope of a more situated analysis. Future research should indeed look into the designs of these toolkits from the perspective of their time and place.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (195.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 LIVING INNOVATION define themselves as ‘one of the first industry driven initiatives on Responsible Innovation in Europe’ (https://www.living-innovation.net/explore).

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O‘Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Ayling, J., and A. Chapman. 2022. “Putting AI Ethics to Work: Are the Tools Fit for Purpose?” AI and Ethics 2 (3): 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00084-x.

- Barac, R., S. Stein, B. Bruce, and M. Barwick. 2014. “Scoping Review of Toolkits as a Knowledge Translation Strategy in Health.” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 14 (1): 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-014-0121-7.

- Bareis, J., M. Roßmann, and F. Bordignon. 2023. “Technology Hype: Dealing with Bold Expectations and Overpromising.” TATuP - Zeitschrift Für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie Und Praxis 32 (3 SE-Special topic [all articles]): 10–71. https://doi.org/10.14512/tatup.32.3.10.

- Bietti, E. 2020. “From Ethics Washing to Ethics Bashing: A View on Tech Ethics from within Moral Philosophy.” Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1145/3351095.3372860

- Boenink, M., T. Swierstra, and D. Stemerding. 2010. “Anticipating the Interaction Between Technology and Morality: A Scenario Study of Experimenting with Humans in Bionanotechnology.” Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology 4 (2), https://doi.org/10.2202/1941-6008.1098.

- Boswell, J., J. Corbett, and R. A. W. Rhodes. 2019. The Art and Craft of Comparison. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108561563

- Buchmann, T., M. Dreyer, M. Müller, and A. Pyka. 2023. “Editorial: Responsible Research and Innovation as a Toolkit: Indicators, Application, and Context.” Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 8: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2023.1267951.

- Burget, M., E. Bardone, and M. Pedaste. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1.

- Collective, C. J., G. Molina León, L. Kirabo, M. Wong-Villacres, N. Karusala, N. Kumar, N. Bidwell, et al. 2021. “Following the Trail of Citational Justice: Critically Examining Knowledge Production in HCI.” Companion Publication of the 2021 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 360–363, Virtual Event USA. October 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3462204.3481732

- Coller, B. S. 2019. “Ethics of Human Genome Editing.” Annual Review of Medicine 70 (1): 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-112717-094629.

- Copp, D., ed. 2007. The Oxford Handbook of Ethical Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195325911.001.0001

- de Hoop, E., A. Pols, and H. Romijn. 2016. “Limits to Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 110–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2016.1231396.

- de Saille, S. 2015. “Innovating Innovation Policy: The Emergence of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 2 (2): 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2015.1045280.

- Fleck, J. 1993. “Innofusion: Feedback in the Innovation Process.” In Systems Science, edited by F. A. Stowell, D. West, and J. G. Howell, 169–174. Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2862-3_30

- Flick, U. 2020. “Triangulation.” In Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie, edited by G. Mey, and K. Mruck, 185–199. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26887-9_23

- Friedman, B. 1997. Human Values and the Design of Computer Technology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, B., D. G. Hendry, and A. Borning. 2017. “A Survey of Value Sensitive Design Methods.” Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction 11 (2): 63–125. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000015.

- Friedman, B., P. H. Kahn, A. Borning, and A. Huldtgren. 2013. “Value Sensitive Design and Information Systems.” In Early Engagement and New Technologies: Opening up the Laboratory, edited by N. Doorn, D. Schuurbiers, I. van de Poel, and M. E. Gorman, 55–95. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7844-3_4

- García, D., E. Zuazua, and B. Perat. 2016. The RRI Toolkit. Barcelona. https://rri-tools.eu/documents/10184/107098/RRITools_D3.2-TheRRIToolkit.pdf/178901f1-6946-4c28-bf1d-a5e910006d82

- Genus, A., and M. Iskandarova. 2018. “Responsible Innovation: Its Institutionalisation and a Critique.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 128: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.029.

- Green, B. 2021. “The Contestation of Tech Ethics: A Sociotechnical Approach to Technology Ethics in Practice.” Journal of Social Computing 2 (3): 209–225. https://doi.org/10.23919/JSC.2021.0018.

- Groves, C. 2017. “Review of RRI Tools Project.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (3): 371–374. http://www.rri-tools.eu

- Guston, D. H. 2014. “Understanding ‘Anticipatory Governance.” Social Studies of Science 44 (2): 218–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713508669.

- Harding, S. 1995. “‘Strong Objectivity’: A Response to the New Objectivity Question.” Synthese 104 (3): 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01064504.

- Hernandez, R. J., and J. Goñi. 2020. “Responsible Design for Sustainable Innovation: Towards an Extended Design Process.” Processes 8 (12): 1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8121574.

- Hurlbut, J. B., S. Jasanoff, K. Saha, A. Ahmed, A. Appiah, E. Bartholet, F. Baylis, … C. Woopen. 2018. “Building Capacity for a Global Genome Editing Observatory: Conceptual Challenges.” Trends in Biotechnology 36 (7): 639–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.04.009.

- Ibáñez, J. C., and M. V. Olmeda. 2022. “Operationalising AI Ethics: How are Companies Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Principles? An Exploratory Study.” AI & SOCIETY 37 (4): 1663–1687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01267-0.

- Irwin, A. 2021. "Risk, Science and Public Communication: Third-Order Thinking About Scientific Culture." In Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, edited by M. Bucchi & B. Trench, 147–162. Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003039242

- Jasanoff, S. 2016. The Ethics of Invention: Technology and the Human Future. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Jasanoff, S., J. B. Hurlbut, and K. Saha. 2019. “Democratic Governance of Human Germline Genome Editing.” The CRISPR Journal 2 (5): 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1089/crispr.2019.0047.

- Joly, P.-B. 2019. “Reimagining Innovation.” In Innovation Beyond Technology, edited by S. Lechevalier, 25–45. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9053-1_2

- Kerr, A., R. L. Hill, and C. Till. 2018. “The Limits of Responsible Innovation: Exploring Care, Vulnerability and Precision Medicine.” Technology in Society 52: 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.03.004.

- Kiran, A. H. 2012. “Responsible Design. A Conceptual Look at Interdependent Design–Use Dynamics.” Philosophy & Technology 25 (2): 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-011-0052-5.

- Kross, J., and A. Giust. 2019. “Elements of Research Questions in Relation to Qualitative Inquiry.” The Qualitative Report 24 (1): 24–30. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3426.

- Kwon, D. 2022. “The Rise of Citational Justice: How Scholars are Making References Fairer.” Nature 603 (7902): 568–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00793-1.

- Lehoux, P., L. Rivard, R. R. de Oliveira, C. M. Mörch, and H. Alami. 2023. “Tools to Foster Responsibility in Digital Solutions That Operate with or Without Artificial Intelligence: A Scoping Review for Health and Innovation Policymakers.” International Journal of Medical Informatics 170: 104933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104933.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. K. O‘Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lynch, M. 2014. “From Normative to Descriptive and Back: Science and Technology Studies and the Practice Turn.” In Science After the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and Social Studies of Science, edited by L. Soler, S. Zwart, M. Lynch, and V. Israel-Jost, 93–113. New York: Routledge.

- Monsonís-Payá, I., E. A. Iñigo, and V. Blok. 2023. “Participation in Monitoring and Evaluation for RRI: A Review of Procedural Approaches Developing Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanisms.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 10: 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2023.2233234.

- Morgan, M. S. 2019. “Exemplification and the use-Values of Cases and Case Studies.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 78: 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2018.12.008.

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Nath, R., and R. Manna. 2021. “From Posthumanism to Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.” AI & SOCIETY 38: 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01274-1.

- Nowotny, H. 2007. “How Many Policy Rooms Are There?” Science, Technology, & Human Values 32 (4): 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907301005.

- Owen, R., P. Macnaghten, and J. Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs093.

- Owen, R., J. Stilgoe, P. Macnaghten, M. Gorman, E. Fisher, and D. Guston. 2013. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 27–50. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch2

- Owen, R., R. von Schomberg, and P. Macnaghten. 2021. “An Unfinished Journey? Reflections on a Decade of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1948789.

- Piaget, J. 1976. “Piaget‘s Theory.” In Piaget and His School, edited by B. Inhelder, H. H. Chipman, and C. Zwingmann, 11–23. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-46323-5_2

- Pirtle, Z., D. Tomblin, and G. Madhavan. 2021. “Reimagining Conceptions of Technological and Societal Progress.” In Engineering and Philosophy. Philosophy of Engineering and Technology (vol. 37), edited by Z. Pirtle, D. Tomblin, and G. Madhavan, 1–21. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70099-7_1.

- Prem, E. 2023. “From Ethical AI Frameworks to Tools: A Review of Approaches.” AI and Ethics 3: 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00258-9.

- Reijers, W., D. Wright, P. Brey, K. Weber, R. Rodrigues, D. O‘Sullivan, and B. Gordijn. 2018. “Methods for Practising Ethics in Research and Innovation: A Literature Review, Critical Analysis and Recommendations.” Science and Engineering Ethics 24 (5): 1437–1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9961-8.

- Rességuier, A., and R. Rodrigues. 2020. “AI Ethics Should not Remain Toothless! A Call to Bring Back the Teeth of Ethics.” Big Data & Society 7 (2): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720942541.

- Ribeiro, B. E., R. D. J. Smith, and K. Millar. 2017. “A Mobilising Concept? Unpacking Academic Representations of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9761-6.

- Schuijff, M., and A. M. Dijkstra. 2020. “Practices of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 26 (2): 533–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00167-3.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., and D. Yanow. 2013. Interpretive Research Design. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203854907

- Sengers, P., K. Boehner, S. David, and J. “Jofish” Kaye. 2005. “Reflective Design.” Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing between Sense and Sensibility - CC ‘05, 49. https://doi.org/10.1145/1094562.1094569

- Simis, M. J., H. Madden, M. A. Cacciatore, and S. K. Yeo. 2016. “The Lure of Rationality: Why Does the Deficit Model Persist in Science Communication?” Public Understanding of Science 25 (4): 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516629749.

- Stahl, B. C., S. Akintoye, L. Bitsch, B. Bringedal, D. Eke, M. Farisco, K. Grasenick, et al. 2021. “From Responsible Research and Innovation to Responsibility by Design.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 175–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1955613.

- Stahl, B. C., and L. Bitsch. 2023. “Building a Responsible Innovation Toolkit as Project Legacy.” Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2023.1112106.

- Stahl, B. C., G. Eden, M. Jirotka, and M. Coeckelbergh. 2014. “From Computer Ethics to Responsible Research and Innovation in ICT.” Information & Management 51 (6): 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.01.001.

- Stewart, J., and R. Williams. 2005. “The Wrong Trousers? Beyond the Design Fallacy: Social Learning and the User.” In Handbook of Critical Information Systems Research, edited by D. Howcroft, and E. M. Trauth, 195–221. Munich: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781845426743.00017

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Tomblin, D., and N. Mogul. 2020. “STS Postures: Responsible Innovation and Research in Undergraduate STEM Education.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (sup1): 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2020.1839230.

- Tronto, J. C. 1993. Moral Boundaries, a Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: New York University Press.

- Vallor, S. 2016. Technology and the Virtues. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190498511.001.0001

- van Lente, H., T. Swierstra, and P.-B. Joly. 2017. “Responsible Innovation as a Critique of Technology Assessment.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (2): 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1326261.

- Vigotsky, L. 1987. “Thinking and Speech.” In The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 1), edited by R. W. Rieber, and A. S. Carton, 39–285. New York: Plenum Press.

- Vinsel, L., and A. L. Russell. 2020. The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession with the New Has Disrupted the Work That Matters Most. New York: Currency.

- Voegtlin, C., and A. G. Scherer. 2017. “Responsible Innovation and the Innovation of Responsibility: Governing Sustainable Development in a Globalized World.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (2): 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2769-z.

- Völker, T., M. Mazzonetto, R. Slaattelid, and R. Strand. 2023. “Translating Tools and Indicators in Territorial RRI.” Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2022.1038970.

- Vygoysky, L. S. 1997. "The Problem of Consciousness." In The Collected Works of L. S. Vigotsky, Vol. 3, (Original work published 1933)). New York: Plenum Press.

- Wertsch, J. V. 1985. Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Williams, R. 2019. "The Social Shaping of Technology (SST). Chapter." In Science, Technology, and Society: New Perspectives and Directions, edited by Todd L. Pittinsky, 138–62. Cambridge: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316691489.006

- Wong, R. Y., M. A., Madaio, and N. Merrill. 2023. “Seeing Like a Toolkit: How Toolkits Envision the Work of AI Ethics.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 7 (CSCW1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579621.

- Wood, D., J. S. Bruner, and G. Ross. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

- Yanow, D. 2014. “Interpretive Analysis and Comparative Research.” In Comparative Policy Studies: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges, edited by I. Engeli, and C. R. Allison, 131–159. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314154_7

- Yin, R. K. 2012. “Case Study Methods.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, edited by H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, 141–155. Washington: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-009.