Abstract

Coalition development is an important approach to the prevention of substance abuse. In addition, empowerment is considered a critical foundation of coalitions’ effectiveness. Few studies, however, have tested the characteristics of coalitions that predict empowerment and effectiveness in substance abuse prevention contexts. This study tested a path model that included organizational characteristics as predictors of members’ empowerment and ratings of coalition effectiveness. Participants (n = 138) were members of 11 coalitions. Leadership had an indirect effect on coalition effectiveness through its influence on opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system. Empowerment mediated the effect of social support on effectiveness.

INTRODUCTION

Coalitions often focus on creating changes in public policy or other environmental conditions that contribute to the prevalence of substance abuse in communities (Bunnell et al., Citation2012; Frieden, Citation2010; Gloppen, Arthur, Hawkins, & Shapiro, Citation2012; Linowski & DiFulvio, Citation2012; Wolfson et al., Citation2012). The present study contributes to the literature through an examination of community coalitions implementing a new federally driven substance abuse prevention framework. In particular, we test a conceptual model specifying organizational characteristics that are hypothesized as promoting empowerment among coalition members and their perceptions of coalition effectiveness. This social work investigation of coalition building within a substance abuse prevention context is an important step in increasing our understanding of empowerment-related processes and outcomes and how they can contribute to the effectiveness of groups working to improve quality of life through community-level interventions. Research that applies empowerment as a theoretical framework may contribute to our knowledge of strategies to improve social work practice in ways that build on the strengths of coalitions to effect social change, especially as it relates to preventing the harmful consequences of substance abuse in communities.

Empowerment is a fundamental concept within the social work profession. For example, the social work Code of Ethics emphasizes the need for social workers to facilitate the empowerment of vulnerable populations by addressing environmental barriers that negatively affect the health and well-being of people on a macro scale (National Association of Social Workers, Citation2008). Empowerment theory encourages researchers and practitioners to focus beyond the individual level of analysis and attend to environmental risk factors affecting the well-being of those most vulnerable. Tracing the field’s roots back to the settlement house movement, social workers have been reasserting for decades that community-level interventions are needed to help people and communities improve quality of life and achieve social justice (Hardcastle & Powers, Citation2004; Haynes, Citation1998; Maton, Citation2008; Specht & Courtney, Citation1995; Weil, Citation1996).

The purpose of this study was to test a path model in which perceptions of organizational characteristics of coalitions were hypothesized as influencing empowerment among coalition members and their ratings of coalition effectiveness. The article is organized in the following way. First, the context of substance abuse and the need for prevention through environmental strategies are described. Second, definitions and the theoretical framework of psychological and organizational empowerment are reviewed. The primary empowerment theories guiding this study were Zimmerman’s (Citation1995) psychological empowerment (PE) theory and Peterson and Zimmerman’s (Citation2004) theory of organizational empowerment (OE). In the third section, the methods and analysis are presented. Finally, the results of the study are presented, and the implications of our findings for social work practice and future research are discussed.

BACKGROUND

The prevention of substance abuse is a national priority in the United States (National Prevention Council, Citation2011; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Citation2011). The abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs, in particular, is significant in the United States, and problematic consumption patterns and behaviors contribute to a wide range of costly consequences, including motor vehicle crashes, suicides, interpersonal violence, unintentional injuries, and alcohol and drug poisoning (SAMHSA, Citation2012). These societal costs can negatively impact local communities, as well as the nation’s criminal justice and healthcare systems (U.S. Department of Justice, Citation2011). The consequences resulting from substance abuse underscore the need for effective preventive interventions as well as treatment.

A recent trend in substance abuse prevention is the adoption of models that are similar to a public health approach, which targets change across an entire population or community (Haggerty & Shapiro, Citation2013; Linowski & DiFulvio, Citation2012; Toomey, Lenk, & Wagenaar, Citation2007). Traditionally, preventive interventions have focused on the individual level of analysis, with the goal of changing knowledge, attitudes, and motivations. Alternatively, environmentally focused, community-level strategies target the conditions of a community or specific population, with the intention to reduce access or opportunities to consume alcohol or use illicit substances, reduce tolerance, and increase penalties for violating alcohol or other drug use laws (Holder, Citation2002; Pentz, Citation1998, Citation2000).

The goal of environmental strategies is to decrease the harmful consequences of substance abuse that impact communities, such as motor vehicle accidents or crime. Specific environmental strategies that have shown promise in reducing the consequences of alcohol use among young adult populations include, for example, the adoption of social host liability laws (Chaloupka, Grossman, & Saffer, Citation2002; Stout, Sloan, Liang, & Davies, Citation2000); enhanced identification checks by alcohol vendors; reduced illegal sales to minors through merchant training (Imm et al., Citation2007; Toomey et al., Citation2007); and the use of media campaigns to change to community norms that tolerate or foster underage drinking (DeJong & Langford, Citation2002; Imm et al., Citation2007; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], Citation2009; Patrick, Maggs, & Osgood, Citation2010; Toomey et al., Citation2007). Similar environmental strategies can be used to target consumption patterns and harmful consequences of other drugs (Dent, Grube, & Biglan, Citation2005; Freisthler, Kepple, Sims, & Martin, Citation2013; Friend & Levy, Citation2002, Holder, Citation2002, Krieger et al., Citation2013) and tobacco use (Bunnell et al., Citation2012).

Although research suggests that environmental strategies have the potential to prevent substance abuse and decrease the occurrence of harmful consequences, their implementation can require extensive collaboration and collective action among diverse stakeholder groups from multiple systems within a community. In an effort to assist communities with the implementation of environmental strategies, the U.S. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) has developed the Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) as a structured guide for the process of community change (Florin et al., Citation2012). The SPF model emphasizes the use of epidemiological data and the development of sustainable, community-based coalitions to implement environmental strategies (Buchanan et al., Citation2010). Typically, these coalitions emphasize the recruitment of multi-sector representatives, analysis of complex community needs, active participation of community members, and grassroots planning and decision making (Berkowitz, Citation2001). Coalitions have been shown to broaden participation within a community, leading to an increase in commitment, resources, and sustainability of an initiative (Gloppen et al., Citation2012; McMillan, Florin, Stevenson, Kerman, & Mitchell, Citation1995; Mizrahi & Rosenthal, Citation2001; Shapiro, Oesterle, Abbott, Arthur, & Hawkins, Citation2013; Wolff, Citation2001).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Empowerment represents a particularly relevant theory for understanding the development coalitions that are utilizing the SPF model to implement environmental strategies. Empowerment refers to a “social action process by which individuals, communities, and organizations gain mastery over their lives in the context of changing their social and political environment to improve equity and quality of life” (Minkler & Wallerstein, Citation1998, p. 40). The construct of empowerment has been studied across many disciplines. Besides the contributions from the field of social work (Gutiérrez, GlenMaye, & DeLois, Citation1995; Hardina, Citation2005; Itzhaky & York, Citation2003; Mano-Negrin, Citation2003; Peterson & Speer, Citation2000; Turner & Shera, Citation2005; Wallach & Mueller, Citation2006; Zippay, Citation1995) and international social work (Cheung, Lo, & Lui, Citation2012) to our understanding of empowerment processes, other disciplines that have paid considerable attention to analyzing empowerment, such as community psychology (Okvat & Zautra, Citation2011; Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004; Speer & Peterson, Citation2000; Rappaport, Citation1984, Citation1995; Zimmerman, Citation1995, Citation2000); nursing (Spence laschinger, Gilbert, Smith, & Leslie, Citation2010); and health care promotion studies (Anderson & Funnell, Citation2010; Mohajer & Earnest, Citation2009). Despite extensive investigations over the years, a unified definition is still missing. Further, empowerment can be conceptualized as occurring at the individual, organizational, and community levels. Hardina (Citation2005) suggested that nonprofit organizations should aim to adopt an empowerment-oriented approach with the goal of fostering empowerment at two levels: the organizational level among staff and the individual client level within the community. To date, empirical studies have not sufficiently tested all levels of this complex construct.

The current study was guided by two central theoretical frameworks established in the existing empowerment literature, one framework at the individual level and one at the organizational level. The first framework is a model of PE proposed by Zimmerman (Citation1995). PE refers to empowerment at the individual level of analysis, which includes beliefs about one’s competence, attempts to exercise control, and an understanding of the socio-political environment (Zimmerman, Citation1995, Citation2000). This framework contains three components: (1) the intrapersonal component of PE, or how one thinks about oneself in terms of perceived control, self-efficacy, competence, and mastery; (2) the interactional component of PE, or one’s understanding of one’s community, which includes critical awareness, skill development, and resource mobilization; and (3) the behavioral component of PE, which refers to one’s actions, including community involvement, organizational participation, and coping behaviors (Zimmerman, Citation1995). This PE framework has been used to guide numerous studies of community-based participation and various health promotion interventions (Holden, Crankshaw, Nimsch, Hinnant, & Hund, Citation2004; Holden, Evans, Hinnant, & Messeri, Citation2005; Peterson, Lowe, Aquilino, & Schneider, Citation2005; Speer & Hughey, Citation1995). Most studies have focused on the intrapersonal component of PE; therefore, to align our work with previous research, we focused on intrapersonal PE.

The second theoretical framework is the model of OE proposed by Peterson and Zimmerman (Citation2004). OE was originally defined by Zimmerman (Citation2000) as organizational efforts that generate opportunities for members’ PE and the organizational effectiveness necessary for goal achievement. Peterson and Zimmerman (Citation2004) extended this definition to propose an OE framework containing three components: intraorganizational, interorganizational, and extraorganizational. The intraorganizational component of OE refers to the internal structure and functioning of groups or organizations. This component of OE was considered important because it can provide the infrastructure for members to engage in proactive behaviors that are needed to obtain goals. The interorganizational component includes the linkages among organizations, such as networking, collaboration, and resource procurement. The extraorganizational component includes efforts by community-based groups and organizations to influence the larger environment of which they are a part. Consistent with much of the previous empirical work in this area, our study will focus on the intraorganizational component of OE.

An important body of research has focused on how intraorganizational characteristics may affect the PE of members. These studies have emphasized how empowerment may be facilitated or hindered in organizational contexts (e.g., Hardina, Citation2011; Ohmer, Citation2008; Wilke & Speer, Citation2011). Of particular interest has been development of knowledge about empowerment processes at the boundary between organizational and individual levels of analysis. These studies have generally found that characteristics of community-based groups or organizations, across a wide variety of types, can affect the PE of individuals. Organizations, such as community-based coalitions engaged in substance abuse prevention, that cultivate activities and characteristics that facilitate PE among members have been described as “empowering organizations” (Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004). Characteristics identified as promoting PE have been termed “empowering organizational characteristics” and include features such as a group’s leadership, opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system. Hughey, Peterson, Lowe and Oprescu (Citation2008) expanded this framework to include sense of community (SOC) as an intraorganizational process of OE. In a study of community residents who participated in health promotion activities, Hughey et al. (Citation2008) showed that SOC was a distinct empowering organizational characteristic. Based on their research, SOC was included as an intraorganizational characteristic in the current study.

Few studies have investigated the effects of organizational characteristics of community-based coalitions on their members’ PE in substance abuse prevention contexts, and no study to date has empirically tested the mediating role of PE in the relationship between organizational characteristics and coalition effectiveness. The goal of the current study was to test a path model in which perceptions of organizational characteristics of coalitions were hypothesized as influencing intrapersonal PE among coalition members and their self-ratings of coalition effectiveness. Data from a statewide coalition development initiative were used to test the theories of PE and OE by examining whether five intraorganizational characteristics (i.e., leadership, opportunity role structure, social support, group-based belief system, and SOC) predicted intrapersonal PE and perceptions of coalition effectiveness among members of community-based coalitions implementing substance abuse prevention activities within the SPF model. Two specific questions guided our study. First, we asked whether the hypothesized path model provided a good fit to the data from the sample of coalition members. Second, we asked whether intrapersonal PE mediated the relationships between members’ perceptions of organizational characteristics and their ratings of coalition effectiveness. Addressing these questions could be useful to researchers and practitioners as they develop interventions that enhance the capacity of coalitions to prevent the harmful consequences of substance abuse in communities.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected in 2011 as part of a parent study that was designed to evaluate 11 community coalitions that were funded to implement the SPF model within a northeastern state. The state was awarded a Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant (SPF SIG) by CSAP in October 2006. This state became one of 16 states, territories, recognized tribes, and tribal organizations within CSAP’s SPF Cohort 3. The purpose of the state’s SPF SIG initiative was to develop and support a statewide, data-driven alcohol, tobacco, and other drug prevention prioritization, implementation, and evaluation infrastructure, which would guide and support communities across the state to implement evidence-based, culturally competent, and sustainable prevention programs, policies, and practices based on needs assessment and epidemiological analysis. Only 11 coalitions were awarded funding to implement the SPF model in this initiative; therefore, all 11 coalitions were invited to participate in the study.

The sampling frame for this study was the membership roster of each coalition. A census of each coalition was then attempted by recruiting survey participants who were coalition staff or members. Data were collected through self-administered, online surveys. The research team sent e-mails to the project coordinators of the coalitions, requesting their assistance in sending out the online survey to all individuals on their membership rosters. All project coordinators agreed to participate and sent their unique coalition survey to all their staff and coalition members. A total of 138 participants completed surveys. One coalition was unable to calculate a response rate; however, the response rates of the other coalitions ranged from 33% to 75%.

Demographic information self-reported by survey respondents included age, gender, race, ethnicity, highest degree or level of school, and total household income. The survey sample was 57.4% female, 3.5% Hispanic or Latino, 90.2% Caucasian, 6.5% Black or African American, 2.4% Asian, and 0.8% American Indian or Alaska Native. The majority of respondents reported the completion of bachelor’s degrees (35.7%) or master’s degrees 34.9%), and 11.7% reported some college credits but no degree as the highest level of education completed. The mean age of respondents was 46 and the range of ages was 19–78 years of age. The average duration of membership of the coalition initiative for participants was 24.48 months (n = 133, SD = 19.05). The average duration of involvement in the alcohol and drug prevention field for participants was 12.24 years (n = 133, SD = 10.28).

Measures

The quantitative, self-administered survey contained 75 items across seven constructs: perceived effectiveness, intrapersonal PE, opportunity role structure, leadership, social support, group-based belief system, and SOC. All items were answered using a six-point, Likert-type scale rating system that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Intrapersonal Component of Psychological Empowerment

The current study used the Sociopolitical Control Scale-Revised (SPCS-R), developed and tested by Peterson, Speer, and Hughey (Citation2006), to measure intrapersonal PE. The SPCS-R was based on Zimmerman’s (Citation1995) model of PE and the investigation of the intrapersonal component of sociopolitical control (SPC) using the original Sociopolitical Control Scale (SPCS) (Zimmerman & Zahniser, Citation1991). The SPCS-R tests two dimensions of the intrapersonal component of PE: leadership competence and policy control. Peterson and colleagues (Citation2006) revised the SPCS to include all positively worded items, and it was found to be reliable (coefficient alpha for leadership competence = .78 and for policy control = .81). The present study included eight items from the SPCS-R (Peterson et al., Citation2006) to assess participants’ leadership competence, (i.e., self-perceptions of individuals’ ability to lead and organize a group of people). Example items included “I can usually organize people to get things done” and “I would rather have a leadership role when I’m involved in a group project.” The self-report survey also contained nine items from the SPCS-R to measure participants’ policy control (i.e., individuals’ self-perceptions of their influence on policy decisions within a community.) Example items included “I enjoy participation because I want to have as much say in my community as possible” and “It is important to me that I actively participate in local prevention efforts.” The SPCS-R variable was created by computing the mean of all 17 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .89). A higher score on this variable indicated higher levels of intrapersonal PE.

Organizational Characteristics

Three self-report measures were administered to measure empowering intraorganizational characteristics as proposed within the OE framework (Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004): opportunity role structure, leadership, social support, group-based belief system, and SOC.

Leadership, Opportunity Role Structure, and Social Support

Maton’s Organizational Characteristics Scale (Maton, Citation1988) used a Likert-type scale to measure perceptions of three organizational characteristics in community-based organizations: (a) leadership, (b) opportunity role structure, and (c) social support. First, the leadership subscale assessed the extent to which individuals with formal or informal responsibility within a group were interpersonally and organizationally talented, werer committed and dedicated to the organization, and supported and responded well to group members. Five items were used to measure participants’ perceptions of leadership. Example items included “The leaders are very committed and dedicated to the SFP SIG initiative” and “The leaders have strong organizational skills and know-how.” Second, the opportunity role structure subscale measured the extent to which members were encouraged to assume a variety of formal positions or roles within an organization and to take charge of different aspects of group functioning (Maton, Citation1988). The present study included five items to measure participants’ perceptions of opportunity role structure. Example items included “Different members of the SPF SIG are in charge of different aspects of its functioning” and “Positions of responsibility are spread among members of the group.” Third, the social support subscale measured the degree to which organizational members provided and received emotional and other types of support. Five items also were used to measure participants’ self-reported levels of social support. Example items of this subscale included “I receive as much support and help as I presently desire from SPF SIG” and “I provide as much support and help to the SPF SIG initiative as I presently desire.” In the present study, alpha reliability was .70 for leadership, .88 for opportunity role structure, and .80 for social support.

Group-Based Belief System

The present study administered select items from Quinn and Spreitzer’s (Citation1991) Competing Values Model of Organizational Culture Scale to measure the group-based belief system of organizations. Group-based belief system (GBBS) refers to the extent to which an organization’s values and culture focus on human relations, teamwork, and cohesion to inspire personal growth and shared vision among members. In this study, five items from this scale were used to measure participants’ self-reported group-based beliefs. Example items included “The SPF SIG initiative encourages participation and open discussion” and “There is a focus on human relations, teamwork, and cohesion within the SPF SIG.” Alpha reliability for this measure in the present study was .89.

Sense of Community

The revised version of the Community Organization Sense of Community (COSOC) scale (Hughey, Speer, & Peterson, Citation1999; Peterson et al., Citation2008) was administered in the present study to measure participants’ self-reported levels of connectedness. The COSOC items are oriented toward the level of community-based organizations, which fit the present study participants. The present study included four items from the COSOC. Example items included “Everyone on SPF SIG is moving in the same direction” and “Because of SPF SIG, I am connected to other groups in the state.” Alpha reliability for this measure in the present study was .87.

Perceived Effectiveness

The measure of perceived effectiveness was created using the framework of Sowa, Selden, and Sandfort (Citation2004). This framework, which was labeled the Multidimensional and Integrated Model of Nonprofit Organizational Effectiveness (MIMNOE), was developed to encompass two different dimensions of community-based organizations: management effectiveness and program effectiveness. The management dimension measures the managerial structure and process of managing. The program dimension measures the specific services, capacity of the program, and outcomes of the service interventions (Sowa et al., Citation2004). Example items in the subscale for perceived effectiveness included: “People who benefit from SPF SIG are satisfied with its activities” and “People within SPF SIG generally have the knowledge and resources they need to carry out their tasks.” In this study, this measure contained 12 items. Alpha reliability for this measure was .91.

RESULTS

The purpose of our study was to test a path model that included hypothesized relationships between perceived organizational characteristics, intrapersonal PE, and perceived effectiveness of community-based coalitions. Leadership served as the exogenous variable in the model and was hypothesized as having direct effects on the three organizational characteristics of opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system. These organizational characteristics were then hypothesized as having both direct and indirect effects on perceived effectiveness through their effects on sense of community and intrapersonal PE. Because no previous research has suggested a direction of effects between three organizational characteristics of opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system, the error terms were correlated as consistent with recommendations in the literature (MacCullum, Wegener, Uchino, & Fabrigar, Citation1993; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008).

Descriptive statistics and correlations are shown in . Results showed strong correlations among the study variables; however, because the correlations were less than or equal to a value of .70, we concluded that these correlations were not strong enough to suggest multicollinearity (Grewal, Cote, & Baumgartner, Citation2004; Mason & Perreault, Citation1991). The first research question asked if the hypothesized path model fit the data from a sample of coalition members implementing an innovative substance abuse prevention framework. To test the fully saturated model, we performed structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures with observed variables using IBM AMOS 20.0 (Arbuckle, Citation2011). The variance-covariance matrix was analyzed with maximum likelihood estimation. The analysis is similar to traditional path analysis; however, SEM allows for simultaneous estimation of equations rather than a series of regression equations.

TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of the Study Variables

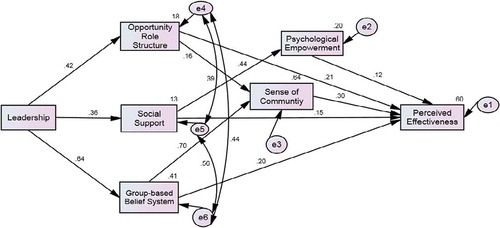

The over-identified model presented in shows only significant paths. The path coefficients presented are statistically significant standardized beta weights. According to the goodness-of-fit measures, the model was found to fit well for the sample, x2 (7) = 11.63, p = .11; Goodness-of-Fit Index = .98; Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index = .91; Comparative Fit Index = .99; and Tucker-Lewis Index = .96. The model accounted for 60% of the variance in perceived effectiveness, 64% of the variance in sense of community, 20% of the variance in intrapersonal PE, 41% of the variance in group-based belief system, 13% of the variance in social support, and 18% of the variance in opportunity role structure.

FIGURE 1 Final path model predicting coalition members’ perceived effectiveness.

As seen in , intrapersonal PE and SOC had direct, positive effects on perceived effectiveness. These findings indicate that individuals with higher scores on the measures of intrapersonal PE tended to perceive higher levels of effectiveness. Similarly, individuals with greater SOC tended to perceive higher levels of effectiveness. Leadership was found to predict perceived effectiveness indirectly through its relationships with opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system. Individuals who perceived stronger leadership within their coalition were more likely to rate their coalition as having a stronger opportunity role structure, and individuals who perceived a stronger opportunity role structure tended to view their coalitions as more effective. Individuals who perceived stronger leadership within their coalition tended to have greater levels of social support, and individuals with greater levels of social support tended to view their coalitions as more effective. Similarly, individuals with stronger leadership characteristics tended to have a greater system of group-based beliefs, and individuals with a greater system of group-based beliefs tended to have higher levels of perceived effectiveness. Leadership was not found to predict perceived effectiveness directly.

Opportunity role structure was found to predict perceived effectiveness directly, as well as indirectly through its relationship with SOC. Individuals who had higher scores representing perceptions of a stronger opportunity role structure tended to perceive higher levels of effectiveness. Additionally, individuals who perceived a stronger opportunity role structure tended to have a greater SOC, which led to higher levels of perceived effectiveness. Social support was found to predict perceived effectiveness directly and indirectly through its relationship with intrapersonal PE. Individuals with greater levels of social support tended to have higher levels of perceived effectiveness. Furthermore, individuals with greater levels of social support tended to have higher levels of intrapersonal PE, and individuals who were more empowered tended to perceive their coalitions as more effective. Group-based belief system was found to predict perceived effectiveness directly, as well as indirectly through its relationship with SOC. Individuals with a greater system of group-based beliefs tended to have higher levels of perceived effectiveness. Finally, individuals with a greater system of group-based beliefs tended to have a greater SOC, which also predicted higher levels of perceived effectiveness.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the literature by testing a model of the relationships between empowering organizational characteristics and intrapersonal PE, and their impacts on coalition members’ perceived effectiveness. Previous research on individual empowerment and OE has not included the relationship to self-reported effectiveness. The findings supported the hypothesis that the suggested path model fit the study data. Several key direct and indirect relationships were found from the path analysis as hypothesized from the literature and guiding theories. As expected, individuals with higher levels of intrapersonal PE tended to perceive higher levels of effectiveness. Similarly, individuals with greater SOC tended to perceive higher levels of effectiveness. These findings expand the existing knowledge about intrapersonal PE and SOC, as previous studies did not look at outcomes such as perceived effectiveness. Some of our findings regarding SOC, however, were not consistent with previous studies. Prior research found SOC to be an important predictor of intrapersonal PE (Hughey et al., Citation2008; Peterson & Reid, Citation2003; Speer, Peterson, Armstead, & Allen, Citation2013). In the present study, participants’ SOC was not found to be a unique predictor of intrapersonal PE.

Two of the organizational characteristics were found to predict perceived effectiveness directly, as well as indirectly through SOC. Individuals with perceptions of stronger opportunity role structure tended to have higher perceived effectiveness. Individuals with perceptions of stronger opportunity role structure tended to have a greater SOC, which led to higher perceived effectiveness. Similarly, a group-based belief system was found to predict perceived effectiveness directly, as well as indirectly through its relationship with SOC. While the prediction of higher levels of perceived effectiveness is a new finding, the other piece of this result is consistent with theory and a recent finding in which organizational characteristics predicted an increase in SOC within a community organization (Wilke & Speer, Citation2011).

Leadership was found to predict perceived effectiveness indirectly through its relationships with opportunity role structure, social support, and group-based belief system. Interestingly in the current study, leadership was not found to predict perceived effectiveness or intrapersonal PE directly. In previous studies, leadership has been found to be an organizational characteristic that predicted PE (Maton, Citation2008; Minkler, Thompson, Bell, & Rose, Citation2001). More consistent with the current study’s finding of the indirect relationship between leadership and intrapersonal PE, Hardina (Citation2005) argued that empowerment-oriented leadership allowed for more staff opportunities and social support and, then related to such outcomes as improved service delivery and successfully advocating for social change.

Social support was found to predict perceived effectiveness directly, as well as indirectly through its relationship with intrapersonal PE. Previous literature on the relationship between organizational characteristics such as social support as a predictor of intrapersonal PE is limited but has been found (Maton & Salem, Citation1995; Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004; Wilke & Speer, Citation2011). This finding extends this literature, as the current study found that individuals with stronger social support tended to have higher levels of intrapersonal PE and those who were more empowered tended to perceive their coalitions as more effective.

The findings of the current study expand existing knowledge about organizational effectiveness through the examination of coalition members’ perceived effectiveness. As noted recently, there is very limited empirical evidence on the measurement of effectiveness within nonprofit organizations and a lack of a unified conceptualization of effectiveness and validated measures (Cho, Citation2007; Lecy, Schmitz, & Swedlund, Citation2012). There is a gap in the effectiveness research that focuses primarily on coalitions and community-based work. Additionally, there is a gap in the empowerment literature on the relationship between empowerment at all levels and perceptions of organizational effectiveness.

Implications for Social Work Administration and Practice

The current study draws on the theoretical model of empowerment at the organizational level developed by Peterson and Zimmerman (Citation2004) that details three levels of constructs that could promote organizational members’ empowerment and possibly influence the effectiveness of the organizational work accomplished. The present study provides an example of the use of the OE framework and the importance of focusing on different levels of organizational processes and outcomes to strengthen the foundation on which communities can create change. Numerous practical and theoretical implications can be drawn from this study.

The prevalence of substance abuse contributes to serious and costly consequences impacting our communities, including motor vehicle crashes, suicide, interpersonal violence, injuries, and negative effects on productivity and our healthcare system (SAMSHA, Citation2012). The SPF proposed by CSAP has begun to show increased coalition capacity (Nargiso et al., Citation2013) and a decrease in problem consumption patterns and related consequences of substance abuse when the model is fully implemented (Imm et al., Citation2007; Buchanan et al., Citation2010), and was included as an effective model in the recently released report to the U.S. Congress on underage drinking prevention efforts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2013). This model relies on the work of coalitions. By identifying ways to improve individual empowerment among coalition members and ultimately create empowered coalitions, the result could lead to a stronger impact on the communities, especially in the areas of substance abuse consequences. The current findings could reach beyond substance abuse prevention to contribute to the development or fostering of coalitions working on improving health, decreasing obesity, decreasing violence against women, and other social issues that can be tackled through a coalition approach. This social work investigation of coalition building within a substance abuse prevention context is critical to increasing our understanding of the ways in which certain characteristics can foster empowerment at an organizational level and result in improved effectiveness of the groups, therefore increasing the impact within their communities. The systems-based approach of the SPF and other community-based prevention models is a collaborative approach among several sets of stakeholders including funders, community partners including community researchers and community agencies, and participants (Institute of Medicine, Citation2012), and therefore all of these sectors will benefit from the continued examination of coalition functioning, member empowerment, and ultimately effectiveness.

The many aspects of the OE and intrapersonal PE theories studied here can contribute to practical skills of social work administrators within community agencies and coalitions to improve their internal structure and functioning, as well as the processes they carry out. For example, such intraorganizational processes as opportunity role structure and leadership should be integral to building capacity within substance abuse prevention coalitions. These processes could be incorporated into technical assistance and training and can be essential to coalition-building activities. Teaching about how to encourage coalition members to take on leadership roles or participate within subcommittees will improve these organizational characteristics.

The organizational characteristic of social support is another concept that should be integrated into these coalitions. Coalition members with high levels of social support reported feeling supported by other members and felt they supported other members. This is an important empowering organizational process characteristic that should be adopted as an essential characteristic of a coalition’s internal structure. Coalitions should assess how well the work responsibilities are spread out among its members, as well as how the combined skills of all members contribute to an environment of strong leadership. Additionally, coalitions could consider improving their incentive management. Incentives help to maintain capacity and decrease interruptions from constant member turnover. Another internal function to improve is how coalitions work through ideological conflict. It is just as important to have a process for conflict resolution as it is to have clear roles for members.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this research adds to the body of current literature, several limitations to this study are noteworthy and could direct areas for future research. First, the sampling technique may be limiting. Purposeful and snowball sampling was used to identify participants, guided by the intent of the original study, which was an evaluation. Selection bias may be an issue due to the study’s sampling methods. However, due to the relationship to the evaluation and their investment in the initiative, participants might have been more accurate and truthful in their answers. Second, this study was cross-sectional in design, limiting causal interpretation of the data. Further research that examines coalition members over time and controls for rival explanations might better examine the relationships suggested in the current model. Additionally, longitudinal study might better examine some of the organizational process and outcome characteristics that may take some time to show a trend. For example, Peterson and Zimmerman (Citation2004) proposed that the process of coalitions participating in alliance-building activities with other organizations is an example of an interorganizational process related to OE that has been found to facilitate collaboration (Foster-Fishman, Salem, Allen, & Fahrbach, Citation2001; Itzhaky & York, Citation2002), an example of an interorganizational outcome related to OE. These interorganizational characteristics may take some time to develop within new coalitions, and future longitudinal examinations could provide better consideration.

Third, the sample in the present study was not diverse in several demographic categories. The survey sample consisted mostly of participants who self-identified as White (90.2%) and not Hispanic or Latino (96.5%). The number of participants who self-identified within different minority groups was very small (e.g., Asians: 2.4%, Pacific Islanders: .8%, Black or African American: 6.5%, and Native American or Alaska Native: 4.3%). Caution is taken regarding the generalizability of the findings due to the diversity issue. Because coalitions did not record demographic data for members, we were unable to compare the demographics of our final sample of survey respondents to non-respondents. Future studies should consider a brief survey of non-respondents to assess the representativeness of those who participated in the survey. A final and important point regarding limitations concerns the unique nature of the coalitions that participated in this study. The coalitions in this study were all funded through a competitive process to support their implementation of the SPF model as they engaged in substance abuse prevention activities. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to all coalitions addressing issues beyond substance abuse and those which are not implementing the SPF model. It may be that other organizational characteristics, which were not included in our study, may be uniquely important for coalitions in particular community contexts. Nevertheless, the study contains several key findings about the ways in which organizational characteristics can be identified and strengthened to help build the capacity of coalitions and still be able to remain distinct in their local activities. Similar types of coalitions or community-based organizations can use the findings as benchmarks for analyzing organizational characteristics, intrapersonal PE, and effectiveness within their groups.

Based on the major findings of this study, as well as the limitations discussed, there are other potential areas for future research. Several studies have been conducted on the OE model, but tested only certain components (Griffith et al., Citation2008, Citation2010; Hardina, Citation2011; Ohmer, Citation2008; Perkins et al., Citation2007; Speer et al., Citation2013). The complete model of OE (Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004) remains largely untested and provides an opportunity to test the processes and outcomes within the three components of OE. While the current study explored some features of OE, the constructs were limited to the intraorganizational component. The interorganizational and extraorganizational components need further testing.

To further understand the dynamic nature of coalitions and the characteristics that might foster individuals’ empowerment, social work researchers might consider testing all components of the PE model. In a recent study on participation and SOC, Speer and colleagues (Citation2013) included gender, income, and both interactional and intrapersonal components of PE in their investigation. Their findings included nuances between emotional or interactional PE and cognitive or interactional PE in relation to gender and income as well as SOC (Speer et al., Citation2013). It might be important to look at the relationships between the different components of PE within different subgroups of coalition members. Further, Peterson (Citation2014) addressed the critical need to test alternative empowerment models with effort given to investigating empowerment, individual or organizational, as a higher-order multidimensional construct. This suggested that new course for empowerment theory should be considered in future studies related to the current findings. Another possible and important direction for future research is to develop an independent measure of effectiveness in order to look beyond self-reported effectiveness and examine the relationships among PE, organizational characteristics, and actual outcomes. This might best begin with a qualitative exploration of coalition staff and management, as well as coalition members, to identify definitions of effectiveness to see if the definition varies depending on roles within the organizational structure.

The current study of a community-based model intended to impact communities by decreasing the negative and harmful consequences of substance abuse contributes to promising social work practice and policy. More specifically, this model of coalitions is an important addition to community-based social work interventions that have shaped the field throughout its history. The public health approach of the SPF model will be an important contribution to social work macro practice and policy in an effort to positively impact communities or populations through the empowerment of groups. Zippay (Citation1995) advised the social work field to be aware of who is defining empowerment, especially in political and policy environments. History has shown evidence of how politics may impact policy by the adoption of a conservative notion of “empowerment” that might move this concept away from a macro approach to social problems and therefore negatively impact individuals. Therefore, social work researchers need to continue to define and test empowerment at all levels as it relates to a systems approach towards social justice. As Addams (Citation1910) strived for, so long ago, and Specht and Courtney (Citation1995), Haynes (Citation1998), Zippay (Citation1995), and other social work researchers have argued, macro social work practice through empowered groups and organizations are necessary in the effort toward improving communities, celebrating diversity, fighting for social justice, and overcoming social problems. This study contributes to the literature by advancing knowledge of empowerment theory. The variables included in this study may be useful targets of intervention for social workers who are attempting to build the capacity of coalitions to prevent the harmful consequences of substance abuse in communities.

REFERENCES

- Addams, J. (1910). Twenty years at Hull House. New York, NY: Macmillian.

- Anderson, R.M., & Funnell, M.M. (2010). Patient empowerment: Myths and misconceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 79(3), 277–282. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.025

- Arbuckle, J.L. (2011). Amos 20 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation. Retrieved from ftp://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/documentation/amos/20.0/en/Manuals/IBM_SPSS_Amos_User_Guide.pdf

- Berkowitz, B. (2001). Studying the outcomes of community-based coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 213–227. doi:10.1023/A:1010374512674

- Buchanan, R.M., Edwards, J.M., Flanagan, S.P., Flewelling, R.L., Kowalczyk, S.M., Sonnefeld, L.J., … Orwin, R.G., (2010). SPF SIG national cross-site evaluation phase I final report. Rockville, MD: Westat. Retrieved from https://www.spfsig.net/public_folder/Reports/Final%20Report/SPF_SIG_Phase-I_Final_Report_6_09_10.pdf

- Bunnell, R., O’Neil, D., Soler, R., Payne, R., Giles, W.H., Collins, J., & Bauer, U. (2012). Fifty communities putting prevention to work: Accelerating chronic disease prevention through policy, systems and environmental change. Journal of Community Health, 37, 1081–1090. doi:10.1007/s10900-012-9542-3

- Chaloupka, F.J., Grossman, M., & Saffer, H. (2002). The effects of price on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Research & Health, 26(1) 22–34. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh26-1/22-34.pdf

- Cheung, C., Lo, T.W., & Liu, S. (2012). Measuring volunteering empowerment and competence in Shanghia. Administration in Social Work, 36(2), 149–174. doi:10.1080/03643107.2011.564722

- Cho, S.M. (2007). Assessing organizational effectiveness in human service organizations—an empirical review of conceptualization and determinants. Journal of Social Service Research, 33(3), 31–45. doi:10.1300/J079v33n03_04

- DeJong, W., & Langford, L.M. (2002). A typology for campus-based alcohol prevention: Moving toward environmental management strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, S14, 140–147. Retrieved from http://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/media/Journal/140-DeJong&Langford.pdf

- Dent, C.W., Grube, J.W., & Biglan, A. (2005). Community-level alcohol availability and enforcement of possession laws as predictors of youth drinking. Preventive Medicine, 40, 355–362. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.014

- Florin, P., Friend, K.B., Buka, S., Egan, C., Barovier, L., & Amodei, B. (2012). The interactive systems framework applied to the strategic prevention framework: The Rhode Island experience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3/4), 402–414. doi:10.1007/s10464-012-9527-5

- Foster-Fishman, P.G., Salem, D.A., Allen, N.A., & Fahrbach, K. (2001). Facilitating interorganizational collaboration: The contributions of interorganizational alliances. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 875–905. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11800511

- Freisthler, B., Kepple, N.J., Sims, R., & Martin, S.E. (2013). Evaluating medical marijuana dispensary policies: Spatial methods for the study of environmentally-based interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1/2), 278–288. doi:10.1007/s10464-012-9542-6

- Frieden, T.R. (2010). A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 590–595. doi:10.2105/Ajph.2009.185652

- Friend, K. & Levy, D.T. (2002). A computer simulation model of mass media interventions directed at tobacco use. Health Education Research, 17(1), 85–98. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0808

- Gloppen, K.M., Arthur, M.W., Hawkins, J.D., & Shapiro, V.B. (2012). Sustainability of the Communities that Care prevention system by coalitions participating in the Community Youth Development Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 259–264. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.018

- Grewal, R., Cote, J.A., & Baumgartner, H. (2004). Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: Implications for theory testing. Marketing Science, 23(4), 519–529. doi:10.1287/mksc.1040.0070

- Griffith, D.M., Allen, J.O., DeLoney, E.H., Robinson, K., Lewis, E.Y., Campbell, B., Morrel-Samuels, S., Sparks, A., Zimmerman, M.A., & Reischl, T. (2010). Community-based organizational capacity building as a strategy to reduce racial health disparities. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 31–39. doi:10.1007/s10935-010-0202-z

- Griffith, D.M., Allen, J.O., Zimmerman, M.A., Morrel-Samuels, S., Reischl, T.M., Cohen, S.E., & Campbell, K.A. (2008). Organizational empowerment in community mobilization to address youth violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(3S) S89–S99. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.015

- Gutiérrez, L., GlenMaye, L., & DeLois, K. (1995). The organizational context of empowerment practice: Implications for social work administration. Social Work, 40(2), 249–258. doi:10.1093/sw/40.2.249

- Haggerty, K.P., & Shapiro, V.B. (2013). Science-based prevention through Communities that Care: A model of social work practice for public health. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3/4), 349–365. doi:10.1080/19371918.2013.774812

- Hardcastle, D.A., & Powers, P.R. (2004). Community practice: Theories and skills for social workers (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hardina, D. (2005). Ten characteristics of empowerment-oriented social service organizations. Administration in Social Work, 29(3), 23–42. doi:10.1300/J147v29n03_03

- Hardina, D. (2011). Are social service managers encouraging consumer participation in decision making in organizations? Administration in Social Work, 35(2), 117–137. doi:10.1080/03643107.2011.557583

- Haynes, K.S. (1998). The one-hundred year debate: Social reform versus individual treatment. Social Work, 43(6), 501–509. doi:10.1093/sw/43.6.501

- Holden, D.J., Crankshaw, E., Nimsch, C., Hinnant, L.W., & Hund, L. (2004). Quantifying the impact of participation in local tobacco control groups on the psychological empowerment of involved youth. Health Education & Behavior, 31(5), 615–628. doi:10.1177/1090198104268678

- Holden, D.J., Evans, W.D., Hinnant, L.W., & Messeri, P. (2005). Modeling psychological empowerment among youth involved in local tobacco control efforts. Health Education & Behavior, 32(2), 264–278. doi:10.1177/1090198104272336

- Holder, H.D. (2002). Prevention of alcohol and drug “abuse” problems at the community level: What research tells us. Substance Use and Misuse, 37(8–10), 901–921. doi:10.1081/JA120004158

- Hughey, J., Peterson, N.A., Lowe, J.B., & Oprescu, F. (2008). Empowerment and sense of community: Clarifying their relationship in community organizations. Health Education & Behavior, 35(5), 651–663. doi:10.1177/1090198106294896

- Hughey, J., Speer, P.W., & Peterson, N.A. (1999). Sense of community in community organizations: Structure and evidence of validity. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(1), 97–113. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199901)27:1<97::AID-JCOP7>3.0.CO;2-K

- Imm, P., Chinman, M., Wandersman, A., Rosenbloom, D., Guckenburg, S., & Leis, R. (2007). Preventing underage drinking: Using getting to outcomes with the SAMHSA strategic prevention framework to achieve results. Technical Report, RAND Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2007/RAND_TR403.pdf

- Institute of Medicine. (2012). An integrated framework for assessing the value of community-based prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/An-Integrated-Framework-for-Assessing-the-Value-of-Community-Based-Prevention.aspx

- Itzhaky, H., & York, A.S. (2002). Showing results in community organizations. Social Work, 47, 125–131. doi:10.1093/sw/47.2.125

- Itzhaky, H., & York, A.S. (2003). Leadership competence and political control: The influential factors. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 371–381. doi:10.102/jcop.10054

- Krieger, J., Coveleski, S., Hecht, M.L., Miller-Day, M., Graham, J.W., Pettigrew, J., & Kootsikas, A. (2013). From kids, through kids, to kids: Examining the social influence strategies used by adolescents to promote prevention among peers. Health Communication, 28(7), 683–695. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.762827

- Lecy, J.D., Schmitz, J.H.P, & Swedlund, H. (2012). Non-governmental and not-for-profit organizational effectiveness: A modern synthesis. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(2), 434–457. doi:10.1007/s11266-011-9204-6

- Linowski, S.A., & DiFulvio, G.T. (2012). Mobilizing for change: A case study of a campus and community coalition to reduce high-risk drinking. Journal of Community Health, 37, 685–693. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9500-5

- MacCallum, R.C., Wegener, D.T., Uchino, B.N., & Fabrigar, L.R. (1993). The problem of equivalent models in applications of covariance structure analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 185–199. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.185

- Mano-Negrin, R. (2003). Spanning the boundaries. Administration in Social Work, 27(3), 25–45. doi:10.1300/J147v27n03_03

- Mason, C.H., & Perreault, W.D. (1991). Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 268–280. doi:10.2307/3172863

- Maton, K.I. (1988). Social support, organizational characteristics of empowering community settings: A multiple case study approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 631–656. doi:10.1007/BF02506985

- Maton, K.I. (2008). Empowering community settings: Agents of individual development, community betterment, and positive social change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1), 4–21. doi:10.1007/BF02506985

- Maton, K.I., & Salem, D.A. (1995). Organizational characteristics of empowering community settings: A multiple case study approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 631–656. doi:10.1007/BF02506985

- McMillan, B., Florin, P., Stevenson, J., Kerman, B., & Mitchell, R.E. (1995). Empowerment praxis in community coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 699–727.

- Minkler, M., Thompson, M., Bell, J., & Rose, K. (2001). Contributions of community involvement to organizational-level empowerment: The federal healthy start experience. Health Education & Behavior, 28(6), 783–807. doi:10.1177/109019810102800609

- Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. B. (1998). Improving health through community organization and community building: A health education perspective. In M. Minkler ( Ed.), Community organizing and community building for health (pp. 30–52). Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

- Mizrahi, T., & Rosenthal, B.B. (2001). Complexities of coalition building: Leaders’ successes, strategies, struggles, and solutions. Social Work, 46(10), 63–78. doi:10.1093/sw/46.1.63

- Mohajer, N., & Earnest, J. (2009). Youth empowerment for the most vulnerable: A model based on the pedagogy of Freire and experiences in the field. Health Education, 109(5), 424–438. doi:10.1108/09654280910984834

- Nargiso, J.E., Friend, K.B., Egan, C., Florin, P., Stevenson, J., Amodei, B., & Barovier, L. (2013). Coalition capacities and environmental strategies to prevent underage drinking. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 222–231. doi:10.1007/s10464-012-9536-4

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2008). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: NASW Press. Retrieved from http://www.naswdc.org/pubs/code/code.asp

- National Prevention Council. (2011). National Prevention Strategy, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/initiatives/prevention/strategy/report.pdf

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2009). A developmental perspective on underage alcohol use. Alcohol Alert, No. 78. Rockville, MD: NIAAA. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AA78/AA78.htm

- Ohmer, M.L. (2008). The relationship between citizen participation and organizational processes and outcomes and the benefits of citizen participation in neighborhood organizations. Journal of Social Service Research, 34, 41–60. doi:10.1080/01488370802162426

- Okvat, H.A., & Zautra, A.J. (2011). Community gardening: A parsimonious path to individual, community, and environmental resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(3/4), 374–387. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9404-z

- Patrick, M.E., Maggs, J.L., & Osgood, D.W. (2010). LateNight Penn State alcohol-free programming: Students drink less on days they participate. Prevention Science, 11, 155–162. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0160-y

- Pentz, M.A. (1998). Preventing drug abuse through the community: Multicomponent programs make the difference. In Z. Sloboda & W.B. Hansen (Eds.), NIDA Research Monograph (#98-4293) (pp. 73–86). Retrieved from http://archives.drugabuse.gov/meetings/CODA/Community.html

- Pentz, M.A. (2000). Institutionalizing community-based prevention through policy change. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(3),257–270. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200005)28:3<257::AID-JCOP3>3.0.CO;2-L

- Perkins, D.D., Bess, K.D., Cooper, D.G., Jones, D.L., Armstead, T., & Speer, P.W. (2007). Community organizational learning: Case studies illustrating a three-dimensional model of levels and orders of change. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(3), 303–328. doi:10.1002/jcop.20150

- Peterson, N.A. (2014). Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher-order multidimensional constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 96–108. doi:10.1007/s10464-013-9624-0

- Peterson, N.A., Lowe, J.B., Aquilino, M.L., & Schneider, J.E. (2005). Linking social cohesion and gender to intrapersonal and interactional empowerment: Support and new implications for theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(2), 233–244. doi:10.1002/jcop.20047

- Peterson, N.A., & Reid, R.J. (2003). Paths to psychological empowerment in an urban community: Sense of community and citizen participation in substance abuse prevention activities. Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1), 25–38. doi:10.1002/jcop.10034

- Peterson, N.A., & Speer, P.W. (2000). Linking organizational characteristics to psychological empowerment: Contextual issues in empowerment theory. Administration in Social Work, 24(4), 39–58. doi:10.1300/J147v24n04_03

- Peterson, N.A., Speer, P.W., & Hughey, J. (2006). Measuring sense of community: A methodological interpretation of the factor structure debate. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(4), 453–469. doi:10.1002/jcop.20109

- Peterson, N.A., Speer, P.W., Hughey, J., Armstead, T.L., Schneider, J.E., & Sheffer, M.A. (2008). Community organizations and sense of community: Further development in theory and measurement. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(6), 798–813. doi:10.1002/jcop.20260

- Peterson, N.A., & Zimmerman, M.A. (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1/2), 129–145. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040151.77047.58

- Preacher, K.J., & Hayes, A.F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Quinn, R.E., & Spreitzer, G.M. (1991). The psychometrics of the competing values culture instrument and analysis of the impact of organizational culture on quality of life. In R.W. Pasmore & W.A. Pasmore ( Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (pp. 115–142). Greenwich, CT: JAI

- Rappaport, J. (1984). Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prevention in Human Services, 3, 1–7. doi:10.1300/J293v03n02_02

- Rappaport, J. (1995). Empowerment meets narrative: Listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5) 795–807. doi:10.1007/BF02506992

- Shapiro, V.B., Oesterle, S., Abbott, R.D., Arthur, M.W., & Hawkins, J.D. (2013). Measuring dimensions of coalition functioning for effective and participatory community practice. Social Work Research, 37(4), 349–359. doi:10.1093/swr/svt028

- Specht, H., & Courtney, M.E. (1995). Unfaithful angels: How social work has abandoned its mission. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Speer, P.W., & Hughey, J. (1995). Community organizing: An ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 729–748. doi:10.1007/BF02506989

- Speer, P.W., & Peterson, N.A. (2000). Psychometric properties of an empowerment scale: Testing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains.Social Work Research, 24(2), 109–118. doi:10.1093/swr/24.2.109

- Speer, P.W., Peterson, N.A., Armstead, T.L., & Allen, C.T. (2013). The influence of participation, gender, and organizational sense of community on psychological empowerment: The moderating effects of income. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1/2), 103–113. doi:10.1007/s10464-012-9547-1

- Spence laschinger, H.K., Gilbert, S., Smith, L.M., & Leslie, K. (2010). Towards a comprehensive theory of nurse/patient empowerment: Applying Kanter’s empowerment theory to patient care. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(1), 4–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01046.x

- Sowa, J.E., Selden, S.C., & Sandfort, J.R. (2004). No longer unmeasurable? A multidimensional integrated model of nonprofit organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(4), 711–728. doi:10.1177/0899764004269146

- Stout, E., Sloan, F., Liang, L., & Davies, H. (2000). Reducing harmful alcohol-related behaviors: Effective regulatory methods. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(3), 402–412. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10807211

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). Report to Congress on the prevention and reduction of underage drinking 2012. Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Report-to-Congress-on-the-Prevention-and-Reduction-of-Underage-Drinking-2012/PEP12-RTCUAD

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Leading change: A plan for SAMHSA’s roles and actions 2011–2014. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4629. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA11-4629/01-FullDocument.pdf

- Toomey, T.L., Lenk, K.M., & Wagenaar, A.C. (2007). Environmental policies to reduce college drinking: An update of research findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(2), 208–219. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17286339

- Turner, L.M., & Shera, W. (2005). Empowerment of human service workers. Administration in Social Work, 29(3), 79–94. doi:10.1300/J147v29n03_06

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Report to Congress on the prevention and reduction of underage drinking. Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//PEP13-RTCUAD/PEP13-RTCUAD.pdf

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2011). National drug threat assessment 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center, Product No. 2011-Q0317-001. Retrieved from www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CEIQFjAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.justice.gov%2Farchive%2Fndic%2Fpubs44%2F44849%2F44849p.pdf&ei=LqwbUeMF5PHTAemygYgD&usg=AFQjCNGhmhMOsRHVFDjExhdPtzyGqQz_6Q&bvm=bv.42261806,d.dmQ

- Wallach, V., & Mueller, C.W. (2006). Job characteristics and organizational predictors of psychological empowerment among paraprofessionals within human service organizations. Administration in Social Work, 30(1), 95–115. doi:10.1300/J147v30n01_06

- Weil, M.O. (1996). Community building: Building community practice. Social Work, 41(5), 481–499. doi:10.1093/sw/41.5.481

- Wilke, L.A., & Speer, P.W. (2011). The mediating influence of organizational characteristics in the relationship between organizational type and relational power: An extension of psychological empowerment research. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(8), 972–986. doi:10.1002/jcop.20484

- Wolff, T. (2001). A practitioner’s guide to successful coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 173–191.

- Wolfson, M., Champion, H., McCoy, T.P., Rhodes, S.D., Ip, E.H., Blocker, J.N.,… DuRant, R.H. (2012). Impact of a randomized campus/community trial to prevent high-risk drinking among college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(10), 1767–1778. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01786.x

- Zimmerman, M.A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–599. doi:10.1007/BF02506983

- Zimmerman, M.A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman ( Eds.), Handbook of community psychology ( p. 43–63). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Zimmerman, M.A., & Zahniser, J.H. (1991). Refinements of sphere-specific measures of perceived control: Development of a sociopolitical control scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 189–204. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199104)19:2<189::AID-JCOP2290190210>3.0.CO;2-6

- Zippay, A. (1995). The politics of empowerment. Social Work, 40, 263–267. doi:10.1093/sw/40.2.263