ABSTRACT

Fluctuations in cultural and racial demographics of communities require leaders to consider the changing needs and expectations of stakeholders. Combining systems theory, theories of organizational change, and the literature on cultural humility and competence, this paper proposes a culturally responsive leadership framework (CRLF) for public sector and human service leaders to improve organizational outcomes equitably. Central to this framework are three elements: considering the socio-cultural aspects of an organization; creating inclusive environments to help facilitate distributed decision making; and a leader’s willingness to learn from all people to mitigate gaps in service delivery that are inadequate and inequitable.

Combining theories of organizational change, cultural humility, and cultural competence, we propose a culturally responsive leadership framework (CRLF) for human service leaders to help create inclusive environments for increasingly diverse stakeholders. A culturally responsive leadership framework has the promise of improving organizational outcomes, such as promoting workforce retention and satisfaction (Pittman, Citation2020), greater workplace productivity (Sabharwal, Citation2014), treatment innovation (Fitzgerald, Ferlie, McGivern, & Buchanan, Citation2013, and mobilization for change (Canterino, Cirella, Piccoli, & Shani, Citation2020). As such, CRLF is a critical framework as a response to our changing demographics. According to the United States Census Bureau, by 2060, the United States will comprise multiple ethnicities creating a no majority population (Colby & Ortman, Citation2015). Besides changes in demographics, public discourse, policies, and litigation also spur a change in decision-making around diversity. Increased attention to issues around diversity ignites “debates about how worth, access, and power both shape public opinions, and how it informs policy decisions” (Lopez-Littleton & Blessett, Citation2015, p. 559) and leadership response to this dynamic environment.

Recently, the unjustifiable death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black citizen, sparked public discourse regarding policing and activated protests of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement across the globe. BLM was created in response to the continual perpetuation of anti-Black sentiment in policing and the state-sanctioned, unjustifiable killings of unarmed Black citizens with little to no recourse. Although BLM primarily demands justice and accountability through police reform, BLM also calls for the reallocation of community resources by re-investing in mental health centers, affordable housing, homeless shelters, substance use treatment centers, and workforce programs that strengthen communities. Particularly salient in BLM is the demand for culturally responsive systems, policies, and practices that promote the dignity and worth of all human beings. Public sector and human service leaders are increasingly tasked with recognizing and validating the cultural experiences of a diverse workforce and clientele. Changing expectations provide an opportunity for integrating public and human service values. Human service values promote client and community well-being when we advocate for social justice, act with integrity, and honor self-determination and cultural diversity (National Organization for Human Services, Citation2015). Similarly, public service values promote “community governance, such as accountability, responsibility, justice, transparency, and improving welfare” (Raffel, Maser, & McFarland, Citation2007, p. 2). Raffel and colleagues believe community governance to be important in creating and supporting a multicultural/multiracial organizational culture.

Many human service organizations, especially in the public sector, suffer from rigid cultures, which can result in making decisions that are not aligned with the needs and expectations of a changing society. To change this outcome, one must better understand the assumptions, values, and beliefs that distinguish the organization’s culture as a fluid process. Cummings and Worley (Citation2009) assert that this process should “start by diagnosing the organization’s existing culture to assess its fit with current or proposed business strategies” (p. 523). After examining one’s organizational culture, leaders may evaluate their decisions differently, particularly in agencies that provide services directly to stakeholders. Public and human service leaders’ chances of success may increase when they intentionally incorporate elements of cultural responsiveness into their leadership and subsequent decision-making practices. In the following section, we define leadership, organizational culture, and introduce a culturally responsive leadership framework for enhancing cultural leadership practices.

Leadership, culture, and organizational culture

Yukl (Citation1989) defines leadership as “individual traits, leader behavior, interaction patterns, role relationships, follower perceptions, influence over followers, influence over tasks and goals, and influence on organizational culture” (p. 252). Cohen (Citation1990) notes that leadership comes with astonishing authority and influence that can make the difference between success and failure. To achieve success, leaders must possess the ability to accomplish their goals through the actions of others (Cohen, Citation1990). A leader must have the conditions or situations to lead and the motivation to do so (Popper, Citation2005). Winning the minds and trust of the individuals around them is a fundamental requirement for a leader’s success (Williams, Citation2013). As a result, we suggest that today’s thriving public sector and human service leader will want to use greater empathy and humility while employing a culturally responsive lens. Culturally responsive leadership helps to create inclusive environments for key stakeholders from ethnically and culturally diverse backgrounds (Santamaria, Citation2013), especially needed in today’s workplace.

Culture can be defined as a “group’s individual and collective ways of thinking, believing, and knowing, which includes their shared experiences, consciousness, skills, values, forms of expression, social institutions, and behaviors” (Tillman, Citation2002, p. 4). Specific to organizations, Glisson, Green, and Williams (Citation2012) define culture as “the expectations and priorities in an organization that determine the way work is done” (p. 622). CRLF facilitates the accrual and integration of cultural knowledge within the context of organizational leadership. It is essential to consider whether leaders have the cultural knowledge to accurately interpret and validate the diverse experiences of their employees and stakeholders. As learners, leaders must integrate new information with prior knowledge and experiences that are culturally based (Tillman, Citation2002).

Culturally responsive leadership involves philosophies, practices, and policies that are flexible and responsive to change. In the public sector, some organizations ascribe to the competing values approach (Quinn, Citation1988). This model proposes a process of examination that places the organization in a position to pivot based on the current internal and external context. Greater flexibility or boundary spanning and human relations skills are required for agencies to adapt to competing values and changing demographics. To position one’s organization for change, organizations must have high expectations for service delivery and incorporate the history, values, and cultural knowledge of the organization and their client base to be effective.

A culturally responsive leadership frame arguably allows agency leaders to make decisions aligned with stakeholder needs and expectations concerning the implementation of programs or services. Organizations engaging in culturally responsive change efforts recognize the role of low-power actors in assessing stakeholder needs (Simpson & Macy, Citation2004), especially in smaller agencies (Hyde, Citation2018). In larger agencies, where shared power is limited, culturally responsive change efforts should focus on flattening their hierarchical structure and engage in shared decision-making processes (Hyde, Citation2018). Culturally relevant leaders have organizations that (1) successfully reach their goals; (2) provide opportunities to improve cultural competence; and (3) ensure decisions connect to a broader social, political, and cultural awareness (Ladson-Billings, Citation1995).

Culturally responsive leadership framework

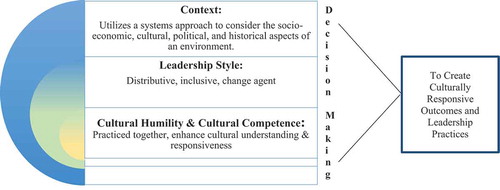

In this framework, the authors focus on leadership and the interdependent nature of relationships. The first component of the framework refers to context, specifically the socio-cultural, political, and historical context. The second component underscores the importance of leadership practices, specifically a distributive leadership style that is inclusive and transformative. The third component focuses on the importance of cultural fluency achieved through cultural humility and cultural competence to enhance leadership within a more diverse workplace and environment (see ). Together these components, in practice, strengthen an organization’s ability to meet the changing needs of employees and client systems.

Context

When examining the context of agencies, it is vital to consider the socio-cultural, political, and historical aspects of an environment. A systems approach presents a framework for making the connection between each component of an organization and the processes and interdependent relationships that exist in them (Senge, Citation2006). Through the systems approach, we can examine organizations and the impact that external forces have on varying parts of that system. Some examples of environmental factors to consider for any organization include the historical context of the environment, the socio-economic conditions around the organization, the role of both the private and public sectors in the community, and the public’s perception of the organization within the community. A more specific example is a Point of Service (POS) agency for the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (IDCFS) refusing to allow gay and lesbian couples to adopt children despite an increased need to place children and increased public acceptance and legislation. The American Civil Liberties Union (Citation2011) legally challenged a POS agency to prevent agencies from discriminating against unmarried and same-sex couples in fostering and adopting children. The court granted IDCFS the right to terminate its contract with said POS agency by the court to prevent discrimination in the provision of services. In this example, the POS agency chose to adhere to their original religious values rather than those of a changing society by no longer serving as a POS agency for IDCFS. As a result, this agency has limited its capacity to achieve culturally responsive outcomes based on internal socio-cultural, political, historical, and in this particular instance, religious context.

The interconnectedness of the open system causes each part to be dependent on other parts; therefore, making a change to one part of the system affects other parts. In the example above, their revenue stream was affected by their break as a POS agency with IDCFS.

Using a culturally responsive lens, we highlight the connection that public and human service organizations have to the culture of the environments they occupy. As a result, effective leaders serving in public and human service agencies should consider how their organization interacts with the surrounding environment and adjust their decision-making accordingly. One example involves an organization needing immediate relocation. This organization served LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning, intersex, and ally) youth in a milieu setting (e.g., group-based social/recreational services and basic needs assistance). Due to the types of programs/services offered and partly due to the population served, the landlord issued a 30-day notice of non-renewal.

Leadership held a roundtable discussion with staff, followed by a meeting with clients during regularly scheduled drop-in hours to assess desired locations for a new space, identified necessary amenities, and preferred program and service offerings. After an initial proposal from leadership, both staff and clients expressed concerns regarding the safety of the proposed location. Consequently, leadership explored different locations that took into account the safety and accessibility concerns of those stakeholders. In the end, leadership and staff reached a consensus regarding a new location without compromising essential programs and services. The new landlord welcomed LGBTQIA youth and was open to the type of programming and services offered. This approach to leadership helped deepen trust between the organization, leadership, staff, and the community. Further, authentic engagement, openness for feedback, and giving staff a voice in improving practices can bolster workforce retention and trust (Pittman, Citation2020).

Regardless of how well-intentioned and politically aware leaders are, the agency structure has an impact on how well they adapt to changes. Consequently, the leader’s leadership style will influence their ability to create an environment where the organizational team buys into goals and plays an active role in achieving measurable outcomes.

Leadership style

Effective leaders must engage in practices that embrace shared responsibility through distributed leadership. Distributed leadership can occur between experts in the field, middle management, and other stakeholders leading to treatment innovations (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2013) and mobilizing change (Canterino et al., Citation2020). Through a distributed leadership lens, leadership practices are a byproduct of their interactions with their followers and their organizational environment (Spillane, Citation2005). It is process-oriented, requires the flexibility to envision change, and develop mutually agreed-upon expectations between leaders and employees that facilitate internal and external interactions (Brimhall et al., Citation2017; Cameron & Quinn, Citation2019; Quinn, Citation1988). Organizational leaders must also possess the ability to evaluate staff characteristics, assess contingency factors, and then shape organizational climate and culture to meet the needs of the organizational environment and use leader-member processes to affect change (Packard, Citation2009).

In general, control in public-sector organizations tends to be top-down, excluding other management levels and supporting staff from important decision-making. Many managers in the public sector view themselves as transactional leaders rather than change agents. They hold onto their jobs by not “rocking the boat” and maintaining a long-term agency perspective based on the long-standing political atmosphere (Boyne, Citation2003). We propose that culturally responsive managers can become leaders that are change agents within their organizations. Further, staff or low power actors can mobilize multicultural change efforts, although they are not in a formal position of authority (Brimhall et al., Citation2017). Shared leadership through a distributive process creates opportunities for culturally responsive practices.

Even organizations that have been quick to respond to marginalized communities’ needs continue to improve their decision-making processes. For example, one large nonprofit (i.e., a federally qualified health care center) organization serving the LGBTQIA community, made changes to their strategic plans to be more inclusive in their decision making. Originally, executive leadership developed a strategic plan from a top-down approach. Then, leadership invited staff to participate as members on advisory committees, but their recommendations were often not implemented. Over time, leadership recognized the importance of having front-line staff take on leadership roles on various decision-making committees as their lived experiences working directly with clients translated into relevant recommendations for practices and policies. Consequently, there was greater buy-in from staff for the implementation of change efforts. To be accountable to clients and staff, leaders must monitor and transparently evaluate change efforts.

Nurturing positive and meaningful interactions between leaders and employees strengthens overall workplace inclusion (Brimhall et al., Citation2017), which is especially important for organizations and leaders with an increasingly diverse workforce and clientele. Moreover, inclusive leadership and practices are associated with decreased conflict and greater innovation and job commitment (Pittman, Citation2020). To be culturally responsive, leaders must eschew the old stale regime and become open to diverse opinions, values, and beliefs. Developing cultural competence and cultural humility is critical to the development of a culturally responsive leadership style.

Cultural humility & cultural competence

Changes in the U.S. demographics and political environment make it necessary to understand people from diverse backgrounds. Three concepts aid in equity and inclusion: (1) leadership humility, (2) cultural humility, and (3) cultural competence. Leadership humility encompasses: (a) a manifested willingness to view oneself accurately, (b) a displayed appreciation of others’ strengths and contributions, and (c) “teachability” or a willingness to learn from all people (Owens, Johnson, & Mitchell, Citation2013, p. 1518). Cultural humility, along with cultural competence, suggests a way of knowing and behaving to enact culturally responsive leadership practices. Both cultural competence and cultural humility are fluid processes. Cultural competence nestled within cultural humility serves as a lens to explore self-awareness and engage in critical self-reflection. Cultural humility involves an open and fluid process of self-reflection, consideration for diverse experiences, and shared power; it is a lifelong learning process that must be exercised daily with “kindness, civility, and respect” for all (Foronda, Baptiste, Ousman, & Reinholdt, Citation2016, p. 214). Scholars generally agree that cultural competence is a process of becoming more culturally aware, skillful, knowledgeable, and inclusive of others (Campinha-Bacote, Citation2002; Carrizales, Zahradnik, & Silverio, Citation2016). The practice of cultural competence is grounded in the values of equity, diversity, ethics, and effectiveness (Carrizales et al., Citation2016).

Cultural conflict may occur in newly inclusive environments as a result of differing values. Hence, this requires leaders to be mindful of how their practices and decisions affect different stakeholders. Mayeno (Citation2007) highlights how organizational leaders are required to be change agents to “overcome resistance from staff members and forces in social, institutional, and organizational environments that reinforce the status quo” (p. 7). Thus, leaders who embrace cultural competency consider the cultural context in which they have to execute their leadership.

Similarly, a culturally responsive leader must be proactive in considering the political climate and how it impacts their employees, staff, clients, and the organization as a whole. Organizations committed to providing immigration services, during shifts in federal governance, are hard hit when federal funds are reduced, and immigration policies penalize non-citizens for accessing services. Under the new “public charge” rule, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can deny an immigrant a visa based on their potential need to use public benefits such as temporary assistance for needy families (Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Citation2020). The culturally responsive leader acting preemptively and inclusively would schedule meetings with key stakeholders to identify expectations during changing times. The culturally responsive leader should examine potential challenges to service delivery, past solutions attempted, and discuss possible changes to the culture, environment, policies, and procedures with an understanding of the historical-political climate.

In Illinois, as a result of a vast coalition of service providers appealing the “public charge” rule, it was temporarily placed on hold (Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Citation2020). Leadership creates opportunities for engagement through shared decision-making, as in the case of the public charge rule. In other words, a culturally responsive leader uses what they know about engaging multicultural groups in a shared decision-making process to better adapt to the changing political climate, impacting client services.

Leaders and helping professionals must take steps to critically evaluate their own “individual biases which affect their ability to engage, join with, and relate to … [clients] … within their culturally varied life experiences” (Quinn & Grumbach, Citation2015, p. 205). It is essential to create a safe space for individual staff to engage in critical self-reflection and where multiple cultures can develop together professionally and collaborate effectively (Horsford, Grosland, & Gunn, Citation2011).

Culturally responsive leaders must also be equity-minded in their hiring and retention practices. For example, hiring staff with lived experiences similar to those of the target population and developing intentional pathways into leadership roles. For diverse staff to feel included in an organization, it is important to commit to strong retention practices, routine training of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and provide professional development and mentoring opportunities. The meaningful inclusion of diverse staff requires listening to diverse voices and opinions and honoring the skills and expertise of a diverse workforce. It may be necessary for some organizations to seek consultation from diverse experts and forge community collaborations with key stakeholders to provide culturally relevant services.

Summary

Utilizing a culturally responsive leadership framework promotes mutual opportunities for cultural growth and engagement. Culturally responsive leadership is not a strategy, but a framework useful for organizing leadership practices that enrich and affirm each person’s culture in the workplace. Public sector and human service leaders who operate from a culturally responsive leadership framework (1) seek to understand the socio-cultural, political, and historical context, (2) engage in a distributive leadership style that is inclusive and transformative, and (3) take actions that lead to equity and effectiveness through cultural humility and cultural competence. Toward that end, CRLF supports the literature that emphasizes the need for leaders to consider context (Glisson et al., Citation2012), act as trust builders (Pittman, Citation2020), engage others in decision making (Brimhall et al., Citation2017; Hyde, Citation2018), and place diversity, equity, and inclusion at the center of their framework and practices (Canterino et al., Citation2020; Carrizales et al., Citation2016; Santamaria, Citation2013).

When leaders’ values, beliefs, and actions go unexamined, their leadership styles remain stagnant, leaving little room for change. Leaders must recognize and be critical of how their lenses may not be inclusive of the breadth and depth of a diverse society.

Making decisions in human service organizations has become increasingly complex as many leaders are dealing with changing demographics and interrelated systems. To exact effective leadership, culturally responsive leaders must create opportunities for employees and other stakeholders to play an active role in achieving mutual goals. Successful implementation of the culturally responsive leadership framework will allow public sector and human service leaders to remain dynamic and able to pivot based on today’s changing internal and external context. Culturally responsive leadership practices not only take into account how changing context affects inclusion and diversity within their organizations but also how these factors influence their decision-making.

We provide organizational leaders with a valuable perspective to make informed decisions and enhance the opportunity for culturally competent leadership. The culturally responsive leadership framework may mitigate the gap of inadequate and inequitable treatment of marginalized communities by being more inclusive and equitable in the administration of their organization. Culturally humble and culturally competent leaders should acknowledge historical and present-day missteps around equity (e.g., racial, gender, sexual orientation, ability, class) and engage in restorative actions for greater inclusion.

Disclosure statement

This editorial introduces a theoretical framework for culturally responsive leadership. No data was collected for this editorial.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2011). Catholic Charities V. DCFS. Retrieved from https://www.aclu-il.org/en/cases/catholic-charities-v-dcfs

- Boyne, G. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(3), 21–27. doi:10.1093/jpart/mug027

- Brimhall, K. C., Mor Barak, M. E., Hurlburt, M., McArdle, J. J., Palinkas, L., & Henwood, B. (2017). Increasing workplace inclusion: The promise of leader-member exchange. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 41(3), 222–239. doi:10.1080/23303131.2016.1251522

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2019). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Campinha-Bacote, J. (2002). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 181–184. doi:10.1177/10459602013003003

- Canterino, F., Cirella, S., Piccoli, B., & Shani, A. B. R. (2020). Leadership and change mobilization: The mediating role of distributed leadership. Journal of Business Research, 108, 42–51. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.052

- Carrizales, T., Zahradnik, A., & Silverio, M. (2016). Organizational advocacy of cultural competency initiatives: Lessons for public administration. Public Administration Quarterly, 40(1), 126–155. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24772945

- Cohen, W. A. (1990). The art of the leader. Prentice Hall.

- Colby, S. L., & Ortman, J. M. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060 population estimates and projections. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009). Organizational development & change (10th ed.). Cengage.

- Fitzgerald, L., Ferlie, E., McGivern, G., & Buchanan, D. (2013). Distributed leadership patterns and service improvement: Evidence and argument from English healthcare. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.10.012

- Foronda, C., Baptiste, D., Ousman, K., & Reinholdt, M. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217. doi:10.1177/1043659615592677

- Glisson, C., Green, P., & Williams, N. J. (2012). Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of child welfare systems: Implications for research and practice. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(9), 621–632. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.002

- Horsford, S. D., Grosland, T., & Gunn, K. M. (2011). Pedagogy of the personal and professional: Toward a framework for culturally relevant leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 21(4), 582–606. doi:10.1177/105268461102100404

- Hyde, C. A. (2018). Leading from below: Low-power actors as organizational change Agents. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 42(1), 53–67. doi:10.1080/23303131.2017.1360229

- Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. (2020, February 10). Public charge. Retrieved from https://www.icirr.org/publiccharge

- Ladson-Billings, G. J. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Education Research Journal, 35(3), 465–491. doi:10.3102/00028312032003465

- Lopez-Littleton, V., & Blessett, B. (2015). A framework for integrating cultural competency into the curriculum of public administration programs. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 21(4), 557–574. doi:10.1080/15236803.2015.12002220

- Mayeno, L. Y. (2007). Multicultural organizational development: A resource for health equity. In Organizational development and capacity in cultural competence. CompassPoint Nonprofit Services; and the California Endowment. Retrieved from https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/Mayeno.pdf

- National Organization for Human Services. (2015). Ethical standards for human services professionals. Retrieved from https://www.nationalhumanservices.org/ethics

- Owens, B. P., Johnson, M. D., & Mitchell, T. R. (2013). Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organization Science, 24(5), 1517–1538. doi:10.1287/orsc.1120.0795

- Packard, T. (2009). Leadership and performance in human services organizations. In The handbook of human services management (pp. 143–164). SAGE.

- Pittman, A. (2020). Leadership rebooted: Cultivating trust with the brain in mind. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(2), 127–143. doi:10.1080/23303131.2019.1696910

- Popper, M. (2005). Leaders who transform society: What drives them and why we are attracted. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

- Quinn, C. R., & Grumbach, G. (2015). Critical race theory and the limits of relational theory in social work with women. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 24(3), 202–218. doi:10.1080/15213204.2015.1062673

- Quinn, R. E. (1988). Beyond rational management: Mastering the paradoxes and competing demands of high performance. Jossey-Bass.

- Raffel, J., Maser, S., & McFarland, L. (2007). NASPAA standards 2009: Public service values, mission-based accreditation. White paper. NASPAA.

- Sabharwal, M. (2014). Is diversity management sufficient? Organizational inclusion to further performance. Public Personnel Management, 43(2), 197–217. doi:10.1177/0091026014522202

- Santamaria, L. J. (2013). Critical change for the greater good: Multicultural perceptions in educational leadership toward social justice and equity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(3), 347–391. doi:10.1177/0013161X13505287

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

- Simpson, B., & Macy, M. (2004). Power, identity, and collective action in social exchange. Social Forces, 82(4), 1375–1411. doi:10.1353/sof.2004.0096

- Spillane, J. P. (2005). Distributed leadership. The Educational Forum, 69(2), 143–150. Taylor & Francis Group. doi:10.1080/00131720508984678

- Tillman, L. C. (2002). Culturally sensitive research approaches: An African-American perspective. Educational Researcher, 31(9), 3–12. doi:10.3102/0013189X031009003

- Williams, H. E. (2013). The formula for Good Public-Sector Managers: An Exploratory sequential study using the most valuable performer survey data to test the competencies and behaviors of human service managers (Publication No. 3569819) [Doctoral dissertation, Benedictine University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Yukl, G. (1989). Managerial leadership: A review of theory research. Journal of Management, 15(2), 251–289. doi:10.1177/014920638901500207