ABSTRACT

This study provides a comparative qualitative case study on two welfare-to-work (WTW) offices with a different understanding of equity and equality. By analyzing organizational documents (n = 27), manager interviews (n = 10), observations of worker-client interactions (n = 13) and worker interviews (n = 13), we find cross-case and within-case variation on frontline worker practices. In the equality-oriented organization, workers acknowledge structural differences, but their practices are more focused on gender- and color-blind equality in treatment. In the equity-oriented organization, we find that more workers implement equity practices. Our findings suggest that organizational context interplays with the practices and beliefs of frontline workers; hence, shaping the fairness of client treatment.

Practical points

Since concepts of equity embedded in organizations appear to affect the frontline context, we recommend introducing equity concepts through guidelines, trainings, and monitoring systems.

To help workers implement equity into their work practices, we recommend personal development practices such as workshops, coaching and mentorship.

We also recommend introducing organizational practices such as mandatory requirements addressing workplace discrimination in WTW workshops and individual interviews with WTW clients.

Overall, our findings suggest that introducing more worker autonomy could be accomplished through clearer equity guidelines and trainings to make racial biases more conscious and to minimize the unintended effects of discretion.

Introduction

Welfare-to-work (WTW) program implementation at the frontline affects the lives of clients and may contribute toward fairness in client treatment. Our study addresses the following research questions: How do organizational discourses and practices on equity (i.e., providing differential treatment, due to structural disadvantages faced by clients; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a) and equality (i.e., gender- and color-blind equal treatment of all clients; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a) shape the practices of frontline workers? Are there gaps between the organizational context and practices among frontline workers? How can managers and workers in social service organizations contribute to social equity among clients?

The U.S welfare reform of 1996 introduced Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF), which aims for the fast work-integration of clients, through lifetime limits for benefits, work requirements, and sanctions for noncompliance policies. The U.S. government grants considerable discretion to states and counties in program design and implementation (Chang et al., Citation2020; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020; Fording et al., Citation2007). Earlier literature suggests race and gender stereotypes being present both in the welfare reform legislation (Monnat, Citation2010; Wacquant, Citation2009) and in the implementation of welfare practices. For example, states with a higher proportion of BlackFootnote1 and Hispanic recipients have less generous benefits and stricter policies (Chang et al., Citation2020; Fording et al., Citation2011; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a; Soss et al., Citation2011).

In addition to having state- and county-level discretion, frontline workers are granted discretion in how workers implement WTW sanctions or service delivery practices in WTW plans. Thus, the practices, perceptions, norms, and beliefs of frontline workers shape the lives of their clients (Frisch-Aviram et al., Citation2018; Gilson, Citation2015; Siddhartha & Winter, Citation2017). Since the WTW process and WTW rules can be too complex for clients, they need to be explained and simplified by the workers (Anderson, Citation2002; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020b). When frontline workers stereotype specific groups of clients, the discretion granted to workers can result in the biased treatment of clients. Studies suggest that white clients receive more services such as childcare, in comparison to Black and Hispanic clients, while the latter groups have higher chances of being sanctioned (Chang et al., Citation2020; Soss et al., Citation2011). Another study suggests subtle differences in e-mail tones toward Hispanic clients, as their housing applications were 20 percentage points less likely to be greeted by name, than were their black and white counterparts (Einstein & Glick, Citation2017).

A recent study suggests that conservative street-level bureaucrats expressed significantly more support for administrative burden policies, arguing that these policies prevent fraud and demonstrate client deservingness while liberal bureaucrats justified opposition to administrative burden by arguing that the requirements undermine social equity (Bell et al., Citation2021). Thus, street-level political ideologies may shape interpretations of administrative burden and perceptions of client deservingness.

Frontline workers are further embedded in an organizational context in which work practices may be shaped by the organizational discourse and practices on equity and equality concepts, measures, guidelines, or trainings. However, few studies have contributed to understand the factors shaping the equity beliefs and practices of the frontline workers. Larkin (Citation2015) suggests how relationship-based model of social work is essential to prevent practitioners from falling back into social discourses or emotional responses. Gunaratnam and Lewis (Citation2001) suggest that it is important to consciously recognize the irrational and unconscious aspects of racial dynamics, which can produce anger, fear, and shame, since emotions are intrinsic to social work (O’Connor, Citation2019).

There is a lack of research focusing on cultural knowledge in social work narratives (Gunaratnam, Citation2011), the effectiveness of racial equity and cultural competency training for workers (Jesús et al., Citation2016), as well as ways to address racism in organizations, such as “white racial affinity groups” (Blitz & Kohl, Citation2012). Hence, social work practice and goals of social equity have not received sufficient attention in policy evaluation and broader social policy literature (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012).

In this study, we aim to fill this gap by broadening the understanding of how organizational discourses and practices shape the practices and beliefs of frontline workers, ultimately affecting the fairness of client treatment. Our study provides a qualitative comparative case study of two WTW offices with different organizational discourses and practices on equity and equality. While social equity has many dimensions, we mainly focus on equity for race and gender.

This study contributes to literature on street-level bureaucrats in human service organization and on welfare implementation literature by adding a conceptual and methodological framework on how to analyze the perceptions and practices of frontline workers in interaction with organizational discourses that perpetuate or reduce social inequities. Understanding these mechanisms has a practical relevance, as it contributes to the understanding of how and where equal treatment at the organizational- and at the frontline-level can be initiated. This understanding can open a dialogue on how both managers and workers at different levels in social service organizations can contribute to social equity among clients.

Conceptual background

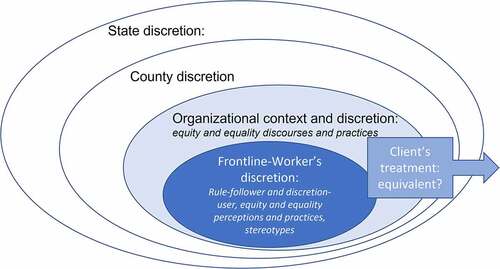

The discretion that is exercised by actors at different policy implementation levels influences how a client is treated. Discretion has reemerged as an issue of central importance for welfare scholars over the last two decades (Evans, Citation2016). In this study, we aim to understand how organizational discretion and context interplay with the discretion of frontline workers and influence the fairness of client treatment. Below, presents the key concepts of our study that reflects aspects of the organizational context of frontline worker discretion, client treatment, and the context of state- and county discretion that shapes U.S. welfare policy.

State and county discretion

Although policies are implemented at different levels in every welfare state, local governments exercise more discretion in federalist and decentralized welfare programs (Lanfranconi & Valarino, Citation2014; Rice, Citation2013). The U.S. government grants considerable discretion to states in TANF program design and implementation. Furthermore, 14 states, including California, passes responsibility down to the counties by giving them discretion and authority over local spending and sanction practices (Chang et al., Citation2020; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a; Fording et al., Citation2007, see two outer circles in ).

Organizational context and discretion: discourses and practices on equity and equality

Local WTW organizations, specifically directors and managers in human service organizations, have more discretion on the implementation of the TANF programs. Organizational context influences both organizational processes and interpersonal interactions within organizations (Khademian, Citation2002). For this study, we are interested in organizational discourses and practices on equity and equality that are manifested through concepts, measures, guidelines, and trainings (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a).

We conceptualize discourses as institutionalized meanings that are constructed within a given context, such as the organizational context (Keller, Citation2011), and practices as routinized action exercised by actors, which can be institutionalized within an organizational context (Rass & Wolff, Citation2018, see the middle circle in ). Since we are particularly interested in discourses and practices on equity and equality, we can conceptualize equality as sameness of treatment by asserting the fundamental equality of all persons and equity as fairness, where individual or group circumstances are taken into consideration (Espinoza, Citation2007). Although achieving fairness can mean treating everyone the same in some cases, it can mean that different groups might get differential treatment based on their current or past inequities in other situations (Gooden, Citation2014).

Frontline workers: discretion, autonomy, practices and beliefs on equity and equality

Lipsky suggests that street-level bureaucrats are important policymakers due to the discretion they exercise and argues that these workers manifest relatively similar coping behaviors owing to their shared working conditions, characterized by chronically limited resources and non-voluntary clients (Siddhartha & Winter, Citation2017). Thus, frontline workers influence policy implementation, as they are granted discretion (Frisch-Aviram et al., Citation2018; Gilson, Citation2015; Siddhartha & Winter, Citation2017).

Nothdurfter and Hermans (Citation2018) claim the importance for the critical analysis and understanding of street-level work as a decisive factor in shaping policy outcomes by pointing out both positive and negative aspects of discretion and developing comprehensive frameworks to explain the use of discretion at the street-level (Nothdurfter & Hermans, Citation2018). The current study contributes to this claim by suggesting both positive and negative aspects of discretion for social equity of clients.

Street-level discretion has been defined as “the autonomy granted to frontline workers to adapt law to the circumstances of cases in a manner consistent with policy and hierarchical authority” (Maynard -Moody & Musheno, Citation2003, p. 4). Autonomy can be understood as “the freedom to make discretionary decisions” (Hupe, Citation2013, p. 434). Thus, we understand discretion as the autonomy granted by the authorities or the political system to frontline workers to interpret binding formal rules or legislation.

Within organizations such as welfare offices, street-level bureaucrats exercise their autonomy to adapt laws or rules to cases individually (Hupe, Citation2013). Adopting Oberfield’s (2009) distinction between rule followers and discretion users, we distinguish the frontline workers on this continuum. Further, being able to empathize with clients can influence frontline worker practices. We understand empathy as the ability to understand and share feelings of the client (Elliott et al., Citation2011).

According to Maynard‐Moody and Musheno (Citation2012), “(S)ocial equity comes to life in the interaction of public administrators and citizens because it is in this exchange that principle meets social reality.” In this study, we are interested in decisional judgments since frontline workers often make decisions under time pressure. They are also guided by schemas, defined as “learned cognitive frames that narrow perception, define our understanding of problems and solutions, and are often so embedded in our understanding that we are rarely conscious of their hold on our thinking and action” (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012, p. 19).

The decisions of frontline workers are based on practical knowledge, judgments as well as stereotypes about clients. A stereotype can be described as “a fixed (or oversimplified) idea about a type of person that is often unfair or untrue, but widely held” (Hinton, Citation2020). For example, stereotypes can be found in the idea of a “deserving poor” (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012). The aversion to and tolerance of street-level bureaucrats toward the client group is related to their use of coping (Siddhartha & Winter, Citation2017). Decisions are not only guided by judgments of clients, but they are also guided by the equity and equality perceptions that frontline workers hold, which can be shaped by organizational discourse and practices on equity and equality. We adopt the idea of stereotypes and equity-equality continuum for our analysis of the frontline workers (see inner circle in ).

Method

Case selection: CalWORKs

This paper is part of a broader study on “Social Equity in California’s WTW Program” (Chang et al., Citation2020; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2021, Citation2020b, Citation2020a). California’s TANF program, CalWORKs, provides temporary cash assistance to meet basic family needs, along with education, employment, and training (CDSS, Citation2019a). We selected CalWORKs as our case study for the following reasons:

A. Compared to other TANF programs, CalWORKs is more inclusive in term of the TANF-to-poverty ratio among 50 states’ programs nationwide. CalWORKs covers the most families living in poverty in comparison to the rest of the U.S. states (Floyd, Citation2020).

B. The program is racially diverse, influenced by the demographics of the state of California since it is the “home of the nation’s largest immigration population” (Reese, Citation2011).

C. It is also highly devolved, operated and administered by county welfare departments under the supervision of the California Department of Social Services (CDSS; Chang et al., Citation2020; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a).

D. For the research purposes of this paper, CalWORKs is further a critical case since the California Welfare Directors Association (CWDA) had within the last years prior to the fieldwork introduced a strategic initiative labeled CalWORKs 2.0, which grants more discretion to frontline workers. This new initiative “considers unique whole-family needs” (CalWORKs 2.0, Citationn.d.). New tools and resources for administrators, frontline workers and clients have been developed to be more client-focused and goal-oriented (Das, Citation2021; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2021).

However, there has not been a specific equity focus embedded in CalWORKs 2.0, which means that the program applies to all clients the same and there is not an embedded logic about treating specific groups of clients differently based on their gender, race, or others (interviews with heads at CWDA; CDSS, 2019; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a).

Research design: qualitative comparative case study on two contrasting WTW organizations in California

For our qualitative comparative case study, we selected two contrasting human service organizations implementing CalWORKs in two “most different” California counties.Footnote2 We named those counties Bay County and Central County for anonymity. Both Bay County (urban, tech-industry) and Central County (rural, agricultural-industry) share a high percentage of people of color while Bay County has a lower WTW sanction, poverty and unemployment rate compared to Central County.

Previous descriptive analysis (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a) of administrative WTW data reveals contrasting patterns of racial disparities in WTW sanctions and exemptions across both counties. We find strong race disparity patterns in Bay County: since Hispanic clients are overrepresented in WTW sanctions, their benefits are cut more often. In WTW exemptions, White clients are overrepresented, and Black clients are underrepresented, indicating that White clients do not have to fulfill work requirements to get benefits as often as other races. However, we find weaker race disparity patterns in Central County: while there is not a statistically significant race-based difference in WTW exemptions, Hispanic clients are underrepresented and White clients overrepresented in WTW sanctions.

A discursive analysis (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a) of organizational documents and interviews with each organization’s managers and directors shows contrasting discourses embedded in both organizational contexts: a race-blind equality discourse in Bay County and an equity discourse in Central County. As this suggests that the organizational context can shapes race outcome patterns, this paper aims to contribute to the understanding of this contrasting race patterns by focusing on the frontline level and how the frontline practices may be shaped by contrasting organizational discourses on equity and equality. We hypothesize that in the equity-oriented organization, we would find more equity perceptions and practices at the frontline level while in the equality-oriented organizations, we would expect to find more equality perceptions and practices at the frontline level.

Data source and collection

To understand how the practices and beliefs of frontline workers are shaped by different organizational discourses and practices, we triangulated data from different sources. Triangulation refers to combining different data and methods to the same phenomenon to get several perspectives that provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon (Jick, Citation1979).

To understand the organizational context, discourses, and practices in terms of discretion and equity-equality concepts, we analyzed:

Twenty-seven organization level CalWORKs documents, including CalWORKs annual reports, website pages, training materials, and frontline employee handbooks.

Ten interviews at the organizational level: CalWORKs Directors, Deputy Directors, Managers, Supervisors, and Civil Rights Coordinator.

To understand the perceptions and practices of frontline workers, we analyzed:

Thirteen participant observations of frontline workers in interactions with clients in intake interviews and WTW workshops (seven in Bay County, six in Central County).

Thirteen semi-structured interviews with the same frontline workers after observations.

Frontline workers, called employment councilors in both organizations, were employed by the same agency of each respective County. In each agency, there was a total of about eighty workers in the function of an employment councilor. In each county, we observed five workers while doing an intake interview, and we observed another three workers while holding a WTW workshop.

While observing, we took notes based on a semi-structured observation grid. We were interested in a) observing the office or workshop environment and characteristics of the workers and clients (gender, race, age, etc.); b) worker-client interactions, level of engagement of both the worker and client through emotional expression and support as well as the level of empathy of workers; c) explicit references from the worker concerning the client’s characteristics (e.g., gender, race, age, etc.) or family status (e.g., motherhood or fatherhood); and d) any reference to fairness, equity, anti-discrimination, equality rules or procedures within WTW.

The interviews and observations were all conducted in the WTW offices by the first author in a supervisor’s office, which was granted by both agencies to the first author. The interviews lasted about 45 to 90 minutes, and were conducted based on a semi-structured interview grid. We asked the workers i) about their biographies and function in the program, ii) the CalWORKs process a client goes through, iii) the specific client-worker interaction observation we did before the interview, iv) thoughts on specific groups of clients, v) perceptions of equity or equality, and finally vi) their wishes and visions for the program.

The first author conducted the fieldwork in Central County in October 2019 and in Bay County in December 2019, right before the global pandemic of Covid-19 hit the U.S. The first author spent about two weeks in each of the agencies to complete the interviews and observations as well as to observe other important parts of organizational processes, discourses, and practices, such as observing a special Santa Claus event for clients and participating in a work meeting. For the observation of the workshops, a research assistant was also on site to provide a more comprehensive observation.

In the processes of selecting frontline workers for the observation and following interviews, we strictly followed the sample plan and looked for workers doing an intake or workshop on the days of fieldwork while finding workers and clients who would agree with the research observation. The study received IRB approval from the first author’s university, which was approved by both WTW organizations. To keep the confidentiality of our interviews and observations, we named the workers anonymously.

Data sample

Our final data sample consists of thirteen workers, all of whom we observed and interviewed. As per our qualitative sampling plan (Kelle & Kluge, Citation2010), the workers were very diverse in their level of seniority, their gender and race (see, ).

Table 1. Overview of the sample of frontline worker ’s, included in both observation and interviews.

Data analysis

After transcribing all the interviews that were recorded with informed consent, we used the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, MAXQDA, to code the observation notes and interviews through an inductive-deductive interplay (Kelle & Kluge, Citation2010). Three different research assistants were involved in coding the transcripts, after being carefully trained by the first author both on the general use of MAXQDA, as well as the specific understanding of the codes and the common rules on the creation of new sub-codes. The first author coded each first transcript simultaneously with the research assistants, to ensure a common understanding and interpretation. To further guarantee a common understanding of each sub-code, all research assistants and the first author discussed their interpretations during regular team meetings and used memos visible for all in the commonly used MAXQDA file of each sub-code.

We deductively generated a coding scheme of five master codes; a) equality (sameness in treatment) and equity (differential treatment of more deserving clients); b) differences (gender, race/ethnicity, age etc.); c) clients challenges; d) CalWORKs process and discretion (WTW sanction, WTW exemption, activities etc.); and e) actors (description of clients etc.). Using this system, we coded observation notes and interview transcripts, inductively generating various sub-codes out of the material.

To understand the organizational context, we analyzed the policy documents and manager interviews. We used critical discourse analysis (CDA; Bacchi, Citation2009; Turgeon, Citation2018; Van Dijk, Citation1993) to uncover implementation strategies of CalWORKs 2.0 and different equity-equality discourses and practices by drawing on the equity-equality frameworks (Espinoza, Citation2007; Gooden, Citation2014, see, Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a).To understand the frontline workers’ beliefs and practices, we conducted a case-by-case content analysis of each frontline worker with the MAXQDA exported quotes of the observations and interviews of the frontline workers in the following five dimensions:

Perceptions of worker autonomy in the CalWORKs process (WTW sanction, activities etc.) based on the interviews and practices of worker autonomy based on the observations, ranging from rule followers to discretion users (Oberfield, Citation2010). Someone was classified a rule-follower, if following strictly to the protocol and applying fix criteria e.g., in WTW sanctioning process or WTW plan developing process. Someone was classified as a discretion user, if frequently using their autonomy by adapting the rules differently in different context, e.g., in WTW sanctioning or WTW plan developing. An important characteristic of a discretionary user is to include clients in decision-making process.

Practice of empathizing or lack thereof based on the observations. Someone was classified as an empathetic worker, if they demonstrated warmth and understanding in their services and engagements with the client through observed body language as well as verbal interaction.

Stereotypes based on client race, ethnicity, gender, and age or negative client perceptions stemming from the idea of an undeserving poor or bad client (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012), based on both interviews and observations.

Perception of equity and equality (Espinoza, Citation2007) among workers based on the interviews. Someone was classified as holding equality perceptions, when talking about the importance to treat all clients the same, not making any differences between clients of different race or genders or neglecting gendered and race-based differences and discrimination. Someone was classified as holding equity perceptions when acknowledging structural and historical inequities of clients of different races or genders (e.g., labor market discrimination).

Practices of equity and equality among workers based on observations. Someone was classified as having equality practices if we observed non-differential treatment of clients based on their race or gender. Someone was classified as having equity practices if in the workshop or interview disadvantages based on race or gender were explicitly addressed to find strategies to overcome them. Workers were also classified as having equity practices when showing differential treatment of clients based on their race or gender to help specific clients to overcome structural and historical inequities.

After the case-by-case analysis of each frontline worker, we compared our findings to develop different types of workers based on these dimensions and the principle of “minimal variation within and maximum variation between cases” (Kelle & Kluge, Citation2010, pp. 108–112). To understand how beliefs and practices of frontline workers may be shaped by the organizational discourses, practices, and other factors, we analyzed the personal backgrounds of frontline workers based on their gender, race, seniority level, educational background, work history, and job motivation.

Findings: perceptions and practices among frontline workers in two contrasting organizations

In the following section, we first present the findings on each organizational discourses and practices and, second, the practices and perceptions of frontline workers. We lastly discuss the gaps between the organizational context and the practices and perceptions of the workers.

Bay county’s organizational discourse and practices: discretion and equality orientation

Bay County’s organizational discourses and practices can be characterized as being equality-orientated and granting discretion to the workers. A CDA-analysis of organizational CalWORKs document and interviews with managers and directors shows a dominant discursive pattern, classified as equality that can be defined as sameness in treatment and processes for all. About 70% of Bay County equality/equity codes at the organization-level pertain to the equality discourse (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a). The organizational culture of the Bay County office is blind for structural disadvantages of specific groups, e.g., to access the program such as African Americans or immigrant clients (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020b, Citation2020a) or inequalities such as discrimination faced on the labor marked by gender or race (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2021).

Bay County implemented the CalWORKs 2.0 initiative a year before the fieldwork for this study. The managers and directors that were interviewed describe the change by referring to the implementation of more frontline worker discretion. They are trying different ways to help the workers integrate the 2.0 philosophy into practice by CalWORKs 2.0 webinar trainings and matching workers for mentorship. In Bay County, the concept of same or differential treatment of clients was not mentioned in any of the quotes about CalWORKs 2.0.

Bay County: practices among frontline workers

Two different groups of workers were found in our analysis: Three of seven workers observed and interviewed can be grouped as non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions while four can be grouped as empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions, but no equity practices.

Non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions

Three workers, named Ricky, Derrick and Marcus, have been classified as non-empathetic in their practices toward clients and by following strict rules. Additionally, all of them hold clear gender- and color-blind equality perceptions and one of the three workers holds clear negative stereotypical perceptions about some of the clients.

In our observations, the workers were not empathetic during their engagement with clients. For example, in the observed intake interview, Ricky starts directly with the paperwork without first asking the client how she feels. We observed both Ricky and the client to look uncomfortable in their body language and to talk very quietly with each other (Ricky, observation notes). Another worker, Derrick, also struggles with being emotionally supportive, as the client started to cry during the intake interview and Derrick just continued the paperwork.

These workers, based on our observation and their own description in the interviews, act rule-based and seldom use autonomy. When asked about the decision-making processes, Marcus for example, explained in a technical way how he comes up with decisions based on a standardized criterion: “If they (the clients) don’t come (to the mandatory meetings), we put them on non-compliance. If they still don’t come and participate, we send them a letter saying that, ‘We take away your benefits’” (Marcus, interview). Similarly, Marcus holds a strict criterion when it comes to finding an appropriate WTW activity for a client. In the observation, we noted: “The worker doesn’t check-in with the client if she agrees with the WTW plan” (Marcus, observation). When asked about why he didn’t check-in with the client about which WTW plan she would have liked, Marcus explains how he comes up with his decisions based on a fixed criterion:

I ask when the last time she worked. The last time she worked was 5 years ago. She needs to have vocational training to have skills before job placement. I get it after the initial screening (Marcus, interview).

All the three workers, besides being non-empathetic rule-followers, have gender- and race-blind sameness in treatment discourse (equality) of the Bay County agency embedded in their perceptions. Although Ricky observes gender difference among his clients, he tries not to act differently based on such differences:

I try to work with each individual the same way I work with everyone else … I don’t think I deviate too much from each client that I work with. (…) As they come in, I just meet them, interview them, go through the process, try not to place any of my own judgments or anything like that. Even if they happen to have any [particular] background, I don’t see them in a different light. (…). As long as they’re able to follow what’s required of them, then it’s all fine (Ricky, interview).

Furthermore, Derrick neglects race discrimination in the workplace:

I don’t think there are racial issues. I have been told (by a client) of some issues in payment, ‘Why do I get $16 and my co-worker gets $17.50?’ She might be taken advantage of by her supervisor or manager. This client is very sensitive about the race issue. She just thinks that in the workplace, people are not nice to her because she is African American (interview, Derrick).

Derrick further explains that it is hard for him to work with clients from different racial backgrounds and he wants to learn how to better work with them:

My thing with some clients is that if they are Black or Latin, they don’t really open up to an Asian worker. I would like to see, if there can be done something to make them more comfortable working with an Asian worker (interview, Derrick).

Ricky similarly explained how he often feels unsure: “I would prefer to have a coach or mentor (…) we don’t really have training” (Ricky, interview). Thus, these workers explicitly express their need to have more training, mentors, or guidelines on how to work with clients e.g., from different race to have a better relationship with them.

Marcus holds very negative perceptions of clients and remains suspicious of a possible welfare fraud. In the observed intake interview, Marcus was the only frontline worker to explicitly discourage welfare fraud, by reminding the client, that the different offices are allowed to share information with each other. Marcus seams to hold specific negative perceptions about men on welfare:

Most of them (WTW clients) experience drug and alcohol problems. They have criminal records that mess up their employment chances. Men and even some ladies don’t like to participate. They have challenges in working at structured environments, mostly men but women too (Marcus, interview).

Although Marcus would use discretion, he uses WTW sanctions much quicker for clients that he assumes to be “trying to trick the system”: “We have more discretion in our work with the client now (with CalWORKs 2.0). If you know the person and their personality, you might act quicker” (Marcus, interview).

Empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions, no equity practices

The other four Bay County workers Mariela, Amy, Damon, and Jessica combine empathy and discretion with an understanding of equity but without transforming this understanding into practice. The use of empathy and discretion in the client’s interest can be seen in Mariela’s understanding of being client-driven: “We have CalWORKs 2.0. It’s more about what the clients want because they will be more successful (…). It takes an open mind and flexibility. We cannot assume the person’s needs” (Mariela, interview). The practice of including clients in decision-making processes (e.g., WTW plan) contrasts sharply with the practices based on fixed criteria used by the rule followers (see above). Another sharp contrast can be seen in the use of sanction applied by the rule followers (see above), versus the flexibility in the use of sanction in the interest of the clients adopted by the discretion users, as e.g., described by Damon:

In terms of participation hours, we could try to find ways to increase participation hours, or we could approach them (the clients) and ask why they couldn’t do those hours. We try to do discussion and remind them to do their best to meet the hours (Damon, interview).

Jessica is another example of using discretion as she describes: “Sometimes – I don’t break the rules – but I bend the hell out of them. It’s for the client, I don’t do it capriciously. I advocate for my clients. (…) It’s about the worker’s direction” (Jessica, interview).

Although these workers hold equity-perceptions and they are more aware about disadvantages faced by clients from certain backgrounds than the rule followers (see above), they still struggle with implementing this awareness into their practice. For example, regarding race and employment, Mariela explains: “There is job discrimination among African American clients” (Mariela, interview). Although Mariela is aware about structural race discrimination in the labor market, she doesn’t know how she personally could help reducing these inequities in her work (Mariela, interview).

Similarly, Damon acknowledges the structural barriers based on gender, race, or immigration status, but he also doesn’t know strategies to help specific groups to overcome their barriers (Damon, interview). In the observation of a WTW workshop held by Damon, we observed that some clients talked about gender discrimination in the labor market and specific structural barriers for mothers in the work application process, but Damon did not expand on this issue during the workshop (Damon, observation, see, Lanfranconi et al., Citation2021).

Jessica is another worker that holds specific stereotypes against some client groups, as we could observe during several instances of the observation and interview session. In the interview, she mentions that she used discretion for a client based on the client’s physical characteristics:

Right now, I have somebody that’s waiting for her employment and she’s so pretty that she’ll get her employment. Instead of putting her on a job hub, below her skill level, I put her on ‘good cause’ (no activity and no sanction) and once it kicks in, she can’t be with us anymore. (…) If not, I’ll put her in an activity. That’s something that other people wouldn’t do. I do it (Jessica, interview).

Jessica also has fixed ideas on gendered parenting, as she explained to a male client in an intake: “But now, you are a family man. Now you need to take care of your wife, of the kids. You need to be the man in the family … ” (Jessica, observation). Additionally, the wife was sitting beside the client while Jessica was explaining her how to be a good mom.

Bay County: conform or resist to the organizational context

The first group of workers (Ricky, Derrick, and Marcus) differ from the organizational discourses and practices embedded in the Bay County’s WTW office, as they are not using the discretion granted to them, while the second group of workers (Mariela, Amy, Damon and Jessica) use their autonomy to advocate for their clients. The first group of workers is much less empathetic in their client engagement than the second group. We suggest the worker-client engagement is hindered by non-empathetic and rule-based treatment.

By analyzing the educational backgrounds of the workers, we found that all the workers from the first group (Ricky, Derrick, and Marcus) have a non-human-focused educational background, such as economics and technical science, while all the workers from the second group (Mariela, Amy, Damon, and Jessica) have a human-focused educational background, such as psychology, social work, or criminal justice.

These two groups of workers also differ in their perceptions about equity. While the first group does not acknowledge structural differences, the second group mostly acknowledges them.

However, all the workers observed and interviewed in Bay County mostly conform to the organizational discourse and practice of equality embedded in the Bay County organization and blindness for structural inequalities in concrete practices.

Based on these findings, we suggest, the prevailing equality discourse in Bay County’s WTW organization shapes frontline worker practices with the clients. The difference in their acknowledgment of structural inequities could be attributed to the differing educational backgrounds of the workers in the two groups. Some workers in the first group stated that they wish for more support (training, mentoring, etc.) in how to work with clients from different backgrounds, which thus far is not a part of Bay County’s context.

In each of both groups, there was one worker, Marcus, and Jessica, who made many of their decisions based on stereotypes of certain groups of clients. These findings suggest the organizational discourse of Bay County’s focus on equality and blindness for structural inequities may not prevent stereotypical schemes that workers may have.

Central county’s organizational discourses and practices: discretion and equity orientation

Central county’s organizational context can be characterized by an equity discourse and a focus on equity in practices as well as granting discretion to the workers. In Central County, the CDA of general CalWORKs documents and interviews show a discourse that pertains closer to equity (see, Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a). 60% of Central County equality-equity codes from the organization-level data pertains to the equity discourse. The organizational discourse of Central County can be summarized as recognizing much more group-specific disadvantages by gender or race.

Central County’s WTW office regularly organizes worker training on cultural competencies and implicit bias. Central County further has developed working groups for specific immigrant communities, which are committed to equitable access to programs for diverse populations through group-specific communication material that is not only translated but carried out in a culturally appropriate way. The working groups advertise actively for CalWORKs in specific immigrant communities to encourage access to the program for these populations (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a).

Central County, like Bay County, began implementing CalWORKs 2.0 about a year prior to the fieldwork, and they realized that the implementation takes a lot of time “because it is a huge shift in the culture” (Central County, Deputy director, 2019). The director over CalWORKs describes the main goal as to better engage with the clients and to give workers more discretion. To succeed in the implementation of 2.0, the deputy director further explains how they implement the new philosophy by consulting and coaching of the workers. Another tool that the Central County WTW office uses to implement 2.0 is making “fun stuff” (Central County, Deputy director, 2019), such as a comic or small video, to help the workers understand the philosophy. Unlike the Bay County, Central County’s WTW office linked the implementation of 2.0 with the question of equity in clients’ treatment, as the deputy director explained:

We did a few more trainings (on CalWORKs 2.0), and it became apparent to us that we needed to do some trainings on cultural competency and implicit bias (Central County, Deputy director, 2019).

Central county: frontline worker practices

We classified the six workers observed and interviewed in Central County into three different groups, two of them being same as in Bay County and the last one as differing along the following attributes: non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions, Empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions, no equity practices and Empathetic, discretion-users with equity perceptions and practices.

Non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions

We classified Lisa and Jackson as non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions, similarly to the first group of workers in Bay County. Lisa and Jackson would like to see clearer rules and criteria in the CalWORKs process to ensure sameness in treatment:

My background from science, we are all about procedure. With procedures here, there could be a checklist or a paper that we go to a client. (…) So that everyone knows the exact same topics and that the clients agree that they understand it too. (…) I’m a procedure person (Lisa, interview).

Jackson likes that there are strict, punitive rules in place to sanction clients:

If you (the clients) fail on your first semester grades, you are on probation. I think that’s good; we’re not letting our clients waste their time. In some ways, it’s better for them because they are not wasting their units, their financial aid (…). We want them to participate, knowing the consequences for not participating (Jackson, interview).

Jackson also would like to see more ways to penalize clients for misbehavior that could worsen their current financial conditions, such as having another baby:

I do wish we had more consequences for not participating or engaging. (…) We used to penalize people if they had babies on aid. To me, in a way, it’s not retroactive but it’s another reason that makes it hard for people to engage with us (Jackson, interview).

Both Lisa and Jackson believe there is equal opportunity for everyone to participate in the program, and they don’t see the need to treat clients differently based on their race or gender: “I don’t really look at race that much. They are all in the same situation, where we need to help them” (Jackson, interview).

Empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions, no equity practices

Janae and Alex combine empathy and use of discretion with equity perceptions without transforming into practice, similarly to the second group of Bay County worker.

Alex, for example, explains how he tries to help people help themselves: “To me, I work for them, they are my boss … I will do everything I can do to help them navigate in this system. It’s the idea of believing in someone” (Interview, Alex). Similarly, Janae talks about centering the clients’ needs to be the top priority: “Most of the time I don’t go with the mindset of, this is what I want my client to do. I ask her what is it that she wants to do that I can help facilitate that” (Janae, interview).

On the other hand, Janae wants to treat all clients in consideration of equity, but she struggles with her personal feelings and perceptions, which she is aware of as well, but still doesn’t know how to act differently. In the past, she had negative experiences with some of her African American clients:

I didn’t have many African Americans come through. The ones that did come through ended up in sanctions. I’m not sure why. (…) He (a black, male client, she talked earlier about) came in and listed all the things he needed. I was like, ‘calm down and let’s sit down first’. He was this big African American man, and I am this small Asian woman, I was thinking, ‘should I be worried about my safety?’ (Janae, interview).

Janae is aware of her negative feelings toward African American men, and she would like to help them more so that they don’t “end up in sanction.” However, she doesn’t have a concrete strategy or plan to accomplish this.

Alex mainly works with Latina clients and knows about their unique struggles. However, he explains that he would never differentiate based on race:

I don’t have a preference; person is a person” (…). Whether they are Black, White or Asian (…) I apply the same rules to everybody. I keep everybody in the same standard. They have something in common: they are all poor (Alex, interview).

Empathetic, discretion-users with equity perceptions and practices

Finally, two workers, Mark, a counselor and Anya, a workshop trainer, combine empathetic, client-driven treatment with both equity perceptions and equity practices. This is an example of Mark motivating his clients:

For me, this whole process is understanding how they understand themselves. From that, I’m using the motivation by giving them the motivation (…). They (the clients) need to have an introspection moment of, ‘What does my future look like? What does it look like when you are happy?’ That’s the goal because that is what’s going to motivate you (Mark, interview).

This was demonstrated in our observation notes from the intake interview of Mark with a client, where Mark asks her client what she wants when elaborating the WTW plan with her. Anya has different strategies to engage with her clients:

One of the things I try to do right away is learn their name. Because that helps me to remember who they are, their specific or special circumstances. Because I want them to feel special (Anya, interview).

Both Mark and Anya hold clear equity perceptions, and they are highly aware of structural inequities in the society and believe that there is a need for differential treatment of more disadvantaged clients. Mark explains how he learned to cope with his emotions and overcome his negative implicit biases to engage and help clients from different races and genders:

You come in as a white, male and you don’t want to overstep and there’s potentially trauma there, especially within the African American community. To me, I subconsciously within myself trying to be not that person. African American ladies for me tend to appear confrontational. I’m reflecting on it, maybe because I’m unfamiliar with the communication styles? When I first started doing the intake interviews, I was like, ‘Okay why are you yelling at me?’ The cases where I can develop some sort of rapport encouraging them with job search, that the real world is hard especially harder for a Black man, that’s bad. There is not a lot I can do personally because it’s a systematic thing. (…). There was a 6ʹ7 African American client who was just intimating to start with and he works as a security guard/bouncer stuff like that. It was just a matter of how I show that I am on your side and I’m not like those other people that I am sincere with my intent to help you (…). Within college, I’ve done cultural humility and racial reconciliation stuff. (…) The understanding I got out of that the African Americans felt like, ‘You’ll give me the job as long as I act white.’ That’s the truth and it sucks (interview, Mark).

Mark is highly aware of his own feelings and (negative) emotions toward clients from different race and gender as well as his own position in society, as e.g., he explained how first it was the most challenging for him – as a white man – to work with the “African American Ladies.” He actively worked on overcoming these feelings and fears and develop specific strategies to engage with all clients. He also acknowledges and addresses discrimination in the labor market and the society within the interaction with clients (“the real world is hart, especially harder for a black man” and “’You’ll give me the job as long as I act white’. That’s the truth and it sucks”). He explained how cultural humility and racial reconciliation training have helped him develop as a frontline worker.

Anya is very conscious about structural gender inequities and shares how a training on stereotypes of men and women’s roles in society changed her biases and practices:

I saw him (a trainer on societal stereotypes about men) speak live and when he was talking about, about how society has expectations that we put on men, it blew my mind because I realized I have a son and I thought, ‘I’m doing this to him as well’. You know, all the expectations that we put on men (…): ‘Don’t be a sissy, don’t cry, don’t show your emotions’. (…). If there’s females in the classroom (in the WTW workshop) and they start talking about, ‘oh, my deadbeat dad, my deadbeat husband’, you know. I go: ‘Well, hold on’, you know. And sometimes that’s when I start bringing out ‘men roles’, like: ‘let’s think about this, what are men going through and what do we not consider when we’re speaking about them’ (interview, Anya).

Anya explains how she brings up the talk about societal expectation on men and women into her workshops. Such addressing of gender roles can help clients reflect their own roles as well as roles they put on husbands, men, or sons and how to overcome such roles. Anya got these reflections out of a training offered at the human service organization.

Frontline worker practices: conforming or resisting the organizational context?

Our analysis of Central County workers reveals three different groups of workers, the first two of them being the same as the two groups identified in Bay County and only the last one as differing from them.

The first group of workers resist both important parts of the organizational context, which is client-driven and equity-oriented. On the contrary, these workers can be characterized as rule-based and equality-oriented. These workers describe their educational background as being more about rules, both having an educational background in a less human-oriented science, helping to understand why they may resist the organizational discourses and practices.

The practices of the workers in the second group seem to be shaped by the organizational context in the use of discretion as well as in the discourse on equity, as they do see structural inequities and reflect upon their implicit biases. However, both workers still struggle in implementing this discourse in practice.

The third group of workers combines the use of discretion and empathy with awareness for inequities experienced by different client groups; these workers translate the organizational discourse on equity into practice. Hence, they treat certain groups of clients differently to help them succeed in the program by acknowledging and addressing structural disadvantages and societal roles based on gender, and race as well as by reflecting on their own position in society and their own emotions and feelings toward specific client groups.

One of the workers of the last group comes from a more human services-focused educational background and his equity perceptions are, based on his explanation, influenced by this educational background along with the organizational discourse and practices of equity. For the other worker, the organizational context plays a critical role, as she refers explicitly to the county’s specific trainings on cultural competency and gender norms in society.

Discussion and policy recommendations: toward social equity at the frontline

Based on a comparative case study design, this paper helps to understand how the interplay of the organizational discourses with the practices and beliefs of frontline workers may help to perpetuate or reduce social inequities. Both WTW organizations chosen for the case study have recently introduced more frontline worker autonomy for a more client-centered approach. The two organizations differ in their embedded understanding of equality and equality, with corresponding guidelines and trainings.

The current study poses a few limitations and avenues for further research. The first limitation is that the sample size of workers observed and interviewed was small (13 workers out of two county WTW offices). However, both counties as well as workers were selected based on a purposive sampling as per clear criteria (Kelle & Kluge, Citation2010). The study further contains rich data and combines both frontline worker observations with interviews as well as rich data on the organizational context. With this limited but rich qualitative sample we can provide hypothesis that can be explored further in subsequent research projects. A second limitation is that we observed further organizational practices, such as team meetings, supervisions and interaction between managers, supervisors, and workers. Future studies could focus systematically on such practices to get a more nuanced picture of how organizational practices and discourses shape frontline workers beliefs and practices toward clients.

Overall, our study displays both cross- and within-organization variation, as shown through the categorization of different groups of workers in each organization. The variety in the types of frontline workers showcase how much the type of frontline worker a client is assigned to may influence the kind of treatment they will receive.

In our limited sample, we find two types of workers in both organizations: non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions, and empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions but no equity practices. We discovered the third type of workers only in the more equity-oriented organization: empathetic discretion user with equity perceptions and practices. Through in-depth description of different types of workers, this paper could serve as a starting point to develop further training-material to discuss unconscious emotional responses with frontline workers.

From the findings of the non-empathetic rule followers with equality perceptions, we suggest that non-empathetic and rule-based treatment of clients may hinder engagement with clients. If this treatment is combined with the neglect of the structural disadvantages of some groups of clients, such as workplace discrimination, we suggest these workers may reproduce social inequities instead of addressing them and helping the client to overcome future discrimination. It is important to note that several frontline workers expressed their need to have more training, mentors, or guidelines on how to work with clients from different races and how to develop a better relationship with clients. Thus, we recommend trainings on implicit biases and cultural awareness as well as on gender roles and disadvantages, specifically for this group of workers. We further recommend the exploration of tools that translate the theory of equity into practice, such as pairing workers who have effective strategies toward equity practices with other workers who struggle in implementing it through shadowing or coaching to overcome generalized social discourses or unconscious emotional responses (Blitz & Kohl, Citation2012; Gunaratnam, Citation2011; Gunaratnam & Lewis, Citation2001; Jesús et al., Citation2016; Larkin, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2019). A recent study finds that frontline workers are likely to need a flexible system of support including peer, organizational and professional support (Billings et al., Citation2021).

From the findings of the second group, empathetic discretion users with equity perceptions but no equity practices, we suggest that even an empathic use of discretion together with an acknowledgment of structural disadvantages may not result in equity practices. Most workers of this group struggle with emotions such as anger, fear, or shame (O’Connor, Citation2019) about specific groups of clients. We suggest that these workers may reproduce existing inequities among different groups of clients, which shows lack of recognition of structural differences without transferring this understanding into practice. These workers may also benefit from the trainings or mentoring programs as described for the first group of workers (Blitz & Kohl, Citation2012; Gunaratnam, Citation2011; Gunaratnam & Lewis, Citation2001; Jesús et al., Citation2016; Larkin, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2019). We also preliminarily recommend including organizational processes, such as mandatory addressing the topic of workplace discrimination based on race and gender as well as the topic of reconciliation of work and family for WTW clients into the WTW workshops and individual interviews (see, Lanfranconi et al., Citation2021).

Finally, the findings of the third group of workers, the empathetic discretion user with equity perceptions and practices, suggest that it is important for workers to be aware of their feelings and (negative) emotions toward clients from different races and genders as well as to reflect and be aware of their position in society. We suggest that the third group of workers should contribute more equity within WTW through equitable practices that are combined with empathy and discretion. Thus, we preliminarily add to existing literature on trainings on generalized social discourses or unconsidered emotional responses (Blitz & Kohl, Citation2012; Gunaratnam, Citation2011; Gunaratnam & Lewis, Citation2001; Jesús et al., Citation2016; Larkin, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2019) the importance of reflecting about the workers’ own positioning in society and privilege. Further, it is important to find strategies to overcoming negative feelings and fears and to develop specific strategies to engage with all clients. These strategies should be discussed in supervisions and team meetings. As a further concrete practice, we identify the importance of acknowledging and thematizing discrimination in the labor market and the society in the interaction with clients to help clients to understand these societal mechanisms and to develop clients’ strategies of how to cope with potential future situations of discrimination and structural disadvantages. Thus, we recommend trainings on how workers can help clients to overcome structural barriers. Finally, the workers of the third group explicitly talk about how they learned and trained their equity perceptions and practices in either their education or organizational trainings, which shows the importance of trainings in education and in further organizational development.

Although our sample is limited, we develop hypotheses about the between-county variation, which should be tested in a broader study. In the equality-oriented, race- and gender-blind organization, we find workers’ characterization seems to play out stronger. Workers that use their discretion to help clients in an empathetic way and have equity perceptions tend to have a human-focused educational background, such as social work or psychology. The less empathetic and rule-following workers, who are more oriented toward equality perceptions and practices, have a less human-focused education. Thus, we draw the preliminary assumption that in such an equality context, the educational background of the frontline workers may strongly influence their perceptions and practices. As they have less trainings within the organization on implicit biases, the perceptions of fair treatment in the sense of equity are mostly available for workers, who know about these issues through their education or personal background or work experience. This assumption would need to be tested in a broader, partly quantitative study.

In the equality-oriented organization, we find in each of the two groups of workers, one worker who has stereotypes of specific clients. We draw the preliminary conclusion that each worker, no matter his or her background, can have or develop such stereotypes in an organization that does not recognize and thematize structural inequities. This assumption needs to be tested in a broader study. We suggest, consistent with previous literature, that practitioners need to be prevented through relationship-based models (Larkin, Citation2015), cultural competency trainings (Jesús et al., Citation2016) and white racial affinity groups (Blitz & Kohl, Citation2012) from falling back onto generalized social discourses or unconsidered emotional responses (Gunaratnam, Citation2011; Gunaratnam & Lewis, Citation2001). When frontline worker autonomy and flexibility are exercised through a gender- or color-blind organization discourse, there is a risk of reproducing existing inequities in society. Although CalWORKs 2.0 may be successful in including more clients back to the labor market, this does not guarantee that it “approximates the standards of justice demanded by social equity” (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012, p. 22).

The findings from the equity-oriented organization suggest a different picture. Although there are some stereotypes present in the descriptions of the workers, the workers actively reflect upon them. This may be interpreted in the direction that frontline workers in this organization are shaped by their organizational discourses and practices of equity. In this organizational context, where equity regulations and practices such as cultural competencies trainings are embedded, worker characteristics seem to play a less important role based on our sample. A preliminary conclusion could be that even workers without a human-focused educational background can learn through organizational discourses and practices such as through trainings about implicit biases and cultural competency on perceptions and practices to better implement equity in daily work practice. This assumption should also be tested through subsequent research.

Our findings contribute to an understanding of the different racial disparity practices in WTW sanction and exemptions at the county level, which seems to be shaped by the organizational discourses and practices in an interplay with the beliefs and practices of frontline workers as well as their educational background. The racial pattern observed in the equality-oriented organization (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a) was that Hispanics are overrepresented in WTW sanctions, and Whites are over-represented, and Blacks are underrepresented in WTW exemptions. This shows the clients of color are treated less favorably, which can be understood by the color-blind equity discourse embedded in the equality-oriented organization, but also by its frontline workers who either have equity perceptions without acting accordingly or have equality perceptions and practices that reproduce existing inequities. The race pattern observed in the equity-oriented organization shows no race differences in WTW exemptions, and an underrepresentation of Hispanics, and an overrepresentation of Whites in WTW sanction (Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a). The pattern seems to be shaped by both the organizational discourse and practices of equity, but also of its frontline workers implementing equity practices or having at least equity perceptions. Nonetheless, broader studies should test these assumptions.

Overall, our findings suggest the perceptions and beliefs of frontline workers are shaped by the organizational discourses and practices of equity and equality. Therefore, we would encourage that human service organizations develop and affirm a more standardized conceptualization of equity as well as a monitoring system, which should be implemented at the highest policy level (Chang et al., Citation2020; Lanfranconi et al., Citation2020a). The more discretion street-level bureaucrats have, the more judgment is involved, and the more social inequities are potentially reproduced (Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2012). Therefore, we recommend that introducing more worker autonomy should be accomplished by clearer equity guidelines and trainings to minimize the unintended effects of discretion.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the literature on street-level bureaucrats in public human service organizations as well as on welfare implementation literature in several important ways. We are adding a conceptual and methodological framework on how to analyze workers’ perceptions and practices in interaction with organizational discourses. As proposed by Nothdurfter and Hermans (Citation2018), we point out both positive and negative aspects of discretion for social equity of welfare clients and develop a framework to understand the use of discretion at the street level.

We are further providing a comparative case-study design in two contrasting organizations that recently implemented a cultural shift toward more worker autonomy and client focus but that differ in equity and equality discourses, with contrasting race disparity practices within WTW that have been observed. We systematically include both the organizational context and frontline workers’ understandings and practices into the analysis, to gain a deeper understanding of how organizational discourses and practices interplay with workers’ perceptions and practices toward social equity.

Finally, we identify the different orientations of frontline workers toward equity practices, by triangulating both observations and interviews of these workers and by considering the personal characteristics of workers. This material can be used for further broader quantitative analysis and to develop case materials to include into the training of frontline workers about implicit biases among workers and promoting more social equity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the terms Hispanic, White, Asian, and Black as used by CDCC (e.g., CDSS, 2019a).

2 The counties have been selected based on a cluster-analysis of five key programs and sociodemographic characteristics (WTW exemption, WTW sanction, nonwhite population, poverty rate, and political ideology) across 58 counties in California. For detailed information on the county selection process see, Chang et al. (Citation2020).

References

- Anderson, S. G. (2002). Ensuring the stability of welfare-to-work exits: The importance of recipient knowledge about work incentives. Social Work, 47(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.2.162

- Bacchi, C. L. (2009). Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be? Pearson Australia.

- Bell, E., Ter-Mkrtchyan, A., Wehde, W., & Smith, K. (2021). Just or unjust? How ideological beliefs shape street-level bureaucrats’ perceptions of administrative burden. Public Administration Review, 81(4), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13311

- Billings, J., Abou Seif, N., Hegarty, S., Ondruskova, T., Soulios, E., Bloomfield, M., Greene, T., & De Luca, V. (2021). What support do frontline workers want? A qualitative study of health and social care workers’ experiences and views of psychosocial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0256454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256454

- Blitz, L. V., & Kohl, B. G. (2012). Addressing racism in the organization: The role of white racial affinity groups in creating change. Administration in Social Work, 36(5), 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2011.624261

- CalWORKs 2.0. (n.d.) CalWORKs 2. 0 | next generation. http://calworksnextgen.org/background/

- CDSS, California Department of Social Services (2019a). CalWorks. Annual Summary. March . Retrieved from: www.cdss.ca.gov/Portals/9/DSSDB/CalWORKsAnnualSummaryMarch2019.pdf.

- Chang, Y.-L., Lanfranconi, L. M., & Clark, K. (2020). Second-order devolution revolution and the hidden structural discrimination?: Examining county welfare-to-work service systems in California. Journal of Poverty, 24(5–6), 430–450. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10875549.2020.1728010

- Das, A. (2021). Interorganizational collaboration and policy reform: Moving young families on welfare out of poverty. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 45(2), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2021.1875943

- Einstein, K. L., & Glick, D. M. (2017). Does race affect access to government services? An experiment exploring street-level bureaucrats and access to public housing. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12252

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022187

- Espinoza, O. (2007). Solving the equity-equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educational Research, 49(4), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880701717198

- Evans, T. (2016). Professional discretion in welfare services: Beyond street-level bureaucracy. Routledge.

- Floyd, I. (2020). Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families. Downloaded at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families.

- Fording, R. C., Soss, J., & Schram, S. F. (2007). Devolution, discretion, and the effect of local political values on TANF sanctioning. Social Service Review, 81(2), 285–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/5179

- Fording, R. C., Soss, J., & Schram, S. F. (2011). Race and the local politics of punishment in the new world of welfare. American Journal of Sociology, 116(5), 1610–1675. https://doi.org/10.1086/657525

- Frisch-Aviram, N., Cohen, N., & Beeri, I. (2018). Low-level bureaucrats, local government regimes and policy entrepreneurship. Policy Sciences, 51(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9296-y

- Gilson, L. L. (2015). Michael Lipsky, street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Public Policy and Administration. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199646135.013.19

- Gooden, S. T. (2014). Race and social equity. A nervous area of government. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315701301

- Gunaratnam, Y. (2011). Cultural vulnerability: A narrative approach to intercultural care. Qualitative Social Work, 12(2), 104–118 https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325011420323.

- Gunaratnam, Y., & Lewis, G. (2001). Racialising emotional labour and emotionalising racialised labour: Anger, fear and shame in social welfare. Journal of Social Work Practice, 15(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650530120090593

- Hinton, P. R. (2020). Stereotypes and the construction of the social world. Routlege.

- Hupe, P. (2013). Dimensions of discretion: Specifying the object of street-level bureaucracy research. Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management, 6(2), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.3224/dms.v6i2.10

- Jesús, A. D., Hogan, J., Martinez, R., Adams, J., & Lacy, T. H. (2016). Putting racism on the table: The implementation and evaluation of a novel racial equity and cultural competency training/consultation model in New York city. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 25(4), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2016.1206497

- Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392366

- Kelle, U., & Kluge, S. (2010). Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92366-6

- Keller, R. (2011). Diskursforschung. Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen [Discourse research. An introduction for social scientists]. VS Verlag.

- Khademian, A. M. (2002). Working with culture: The way the job gets done in public programs. CQ Press.

- Lanfranconi, L. M., Aditi, D., Joy, S., & Patricia, M. (2021). Becoming job-ready? Narratives of local welfare-to-work programs and client experiences across differing economic contexts in California. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 104438942110484. https://doi.org/10.1177/10443894211048451

- Lanfranconi, L. M., Chang, Y.-L., & Basaran, A. (2020b). At the intersection of immigration and welfare governance in the United States: State, county and frontline levels and clients’ perspectives. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform, 66(4), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1515/zsr-2020-0019

- Lanfranconi, L. M., Chang, Y.-L., Das, A., & Simpson, P. J. (2020a). Equity versus equality: Discourses and practices within decentralized welfare-to-work programs in California. Social Policy & Administration, 54(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12599

- Lanfranconi, L. M., & Valarino, I. (2014). Gender equality and parental leave policies in Switzerland: A discursive and feminist perspective. Critical Social Policy, 34(4), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018314536132

- Lanfranconi, L. M., Yu-Ling, C., Aditi, D., & Simpson, P. J. (2020a). Equity versus equality: Discourses and practices within decentralized welfare-to-work programs in California. Social Policy & Administration, 54(6), 883–899. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/spol.12599

- Larkin, R. (2015). Understanding the ‘Lived experience’ of unaccompanied young women: Challenges and opportunities for social work. Practice, 27(5), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1070817

- Maynard‐Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2012). Social equities and inequities in practice: Street-level workers as agents and pragmatists. Public Administration Review, 72(1), 16–23 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41688034#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2003). Cops, Teachers, Counselors: Stories from the Front Lines of Public Service. University of Michigan Press.

- Monnat, S. M. (2010). Toward a critical understanding of gendered color-blind racism within the U.S. Welfare institution. Journal of Black Studies, 40(4), 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934708317739

- Nothdurfter, U., & Hermans, K. (2018). Meeting (or not) at the street level? A literature review on street-level research in public management, social policy and social work. International Journal of Social Welfare, 27(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12308

- Oberfield, Z. W. (2010). Rule following and discretion at government’s frontlines: Continuity and change during organization socialization. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(4), 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mup025

- O’Connor, L. (2019). How social workers understand and use their emotions in practice: A thematic synthesis literature review. Qualitative Social Work, 19(4), 645–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325019843991

- Rass, C., Wolff, F. (2018). What Is in a Migration Regime? Genealogical Approach and Methodological Proposal. In: Pott, A., Rass, C., Wolff, F. (eds) Was ist ein Migrationsregime? What Is a Migration Regime?. Migrationsgesellschaften. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-20532-4_2

- Reese, E. (2011). They Say Cutback, We Say Fight Back! Welfare Activism in an Era of Retrenchment. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Rice, D. (2013). Street-level bureaucrats and the welfare state: Toward a micro-institutionalist theory of policy implementation. Administration & Society, 45(9), 1038–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399712451895

- Siddhartha, B., & Winter, S. C. (2017). Street-level bureaucrats as individual policymakers: The relationship between attitudes and coping behavior toward vulnerable children and youth. International Public Management Journal, 20(2), 316–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2016.1235641

- Soss, J., Fording, R. C., & Schram, S. (2011). Disciplining the poor: Neoliberal paternalism and the persistent power of race. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos155

- Turgeon, B. (2018). A critical discourse analysis of welfare-to-work program managers’ expectations and evaluations of their clients’ mothering. Critical Sociology, 44(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516654555