ABSTRACT

The study focuses on a government-initiated project designed to implement the Systemic Practice Model (SPM) in Finland. The SPM is an adaptation of the UK Reclaiming Social Work (RSW) model, which aims to deliver systemic practice in children’s services. Interviews with key change agents were used to examine how and why the RSW model was adapted to Finland and the potential factors influencing its implementation at system and organizational levels. The findings indicate that challenges associated with central government’s adaptation and dissemination of the model percolated down to implementing agencies. The results emphasize careful preparation and academic-practice-collaboration in future initiatives.

PRACTICE POINTS

Careful preparation, including identifying potential barriers to change, and high-quality implementation support are crucial for achieving the desired change in practice.

Considering the need for adaptation before implementing new innovations is important; more specifically, it is necessary to identify which components can be altered and which should never be modified.

Active collaboration between intervention developers, practice stakeholders, and researchers can improve the quality of implementation processes.

Change efforts should begin with small-scale testing and proceed to wider implementation only if supported by evaluation results.

Identifying outer context factors, such as large service reforms, that might impede change in local settings is important.

Introduction

The past few years have seen rapid advances in the field of implementation research within human and social service organizations (Bunger & Lengnick-Hall, Citation2019; Cabassa, Citation2016; Metz Albers et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, despite the growing body of research, implementation studies often focus on the delivery of research-supported interventions in discrete organizations without examining the larger external environment and relationships among organizations that also influence implementation (Bunger & Lengnick-Hall, Citation2019). Indeed, only a small number of studies have investigated the implementation-related decision making and policy-level actions that influence implementation processes (Willging et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, previous studies have analyzed public-private partnerships in implementation (McBeath et al., Citation2019; Willging et al., Citation2018), but less is known about collaboration between central government and local agencies in such change efforts. Regarding change at the organizational level, implementation studies in child welfare demonstrate the central importance of rigorous implementation support, such as training, coaching, and engaging organization leaders for change (Albers & Shlonsky, Citation2020, Garcia et al., Citation2020; Rijbroek et al., Citation2017). However, many studies exclude the views of senior stakeholders, i.e., leaders and trainers, on implementation efforts.

This study builds on previous implementation research on the roles of key change agents (Garcia et al., Citation2019; Glisson, Citation2015; Metz et al., Citation2021; Weeks et al., Citation2022) and seeks to provide a multi-perspective view on a government-initiated implementation initiative in public social services in Finland by utilizing the qualitative interviews of stakeholders in central government and local agencies. The initiative in question aimed to improve the quality of Finnish child welfare through the nationwide adoption of the Systemic Practice Model (SPM) in multiple agencies between 2016 and 2018. The SPM is an adaptation of the UK-based Reclaiming Social Work (RSW) model (Goodman & Trowler, Citation2012), and it aims to deliver systemic social work practice in children’s services. This study adopts a retrospective view on the SPM’s adaptation process while examining the system and organizational contextual factors (von Thiele Schwarz et al., Citation2019) potentially influencing the model’s initial implementation. The objectives are:

to investigate how and why the UK Reclaiming Social Work model was adapted to Finland

to examine possible implementation barriers and facilitators based on the perceptions of leaders and change agents in central government and local agencies.

Previous implementation studies on system and organizational contextual factors in child welfare

In terms of factors external to organizations, a systematic review by Weeks (Citation2021) concluded that funding (i.e., limited resources and a lack of time and flexibility in funding) constituted one of the most substantial implementation barriers in child welfare settings. Another important key determinant was found to be collaboration between organizations, including external partners, government/state and local-level authorities, and academic-practice partnerships. A study by Willging et al. (Citation2015) on the experiences of policymakers (i.e., state and county government employees) of implementing evidence-based practice also highlighted state and county leadership, proactive planning, and legal, legislative, and political pressures.

In turn, previous research on implementation determinants at an organizational level in child welfare stress the importance of leadership and stakeholder involvement to increase the organizational buy-in (Garcia et al., Citation2019; Lambert et al., Citation2016; Rushovich et al., Citation2015; Sanclimenti et al., Citation2017; Willging et al., Citation2018). For example, Garcia et al. (Citation2019) found that directors lacked both the readiness to assess the burden on practitioners of implementing interventions and the skills and knowledge necessary to inform them adequately about forthcoming interventions. Sanclimenti et al. (Citation2017), by contrast, emphasize the importance of aligning parallel implementation initiatives. Previous evaluations also stress the role of a supportive organizational climate in successful implementation (Garcia et al., Citation2019; Lambert et al., Citation2016), while an unaccommodating organizational climate has been linked to limited resources (Garcia et al., Citation2019). In addition, a study by Lambert et al. (Citation2016) noted that “change fatigue” in the organization may hamper implementation efforts.

Furthermore, a systematic review by Albers et al. (Citation2021) identified 18 implementation strategies used by implementation support practitioners (ISPs) to help leaders and practitioners working in human and social services and related fields implement research-supported interventions. The review found that multiple terms for ISPs exist, such as facilitators, consultants, technical assistance (TA) providers, coaches, and intermediaries. The strategies identified by the review included training and educating stakeholders, using evaluative and iterative strategies, developing stakeholder interrelationships, and adapting and tailoring strategies to context. Previous studies on TA in child welfare settings indicate that a clear implementation vision and roles, coaching to reinforce training, fostering implementation knowledge and skills as well as the alignment between TA and evaluation can enhance the success of the TA experience (Rushovich et al., Citation2015; Sanclimenti et al., Citation2017). In addition, Rushovich et al. (Citation2015) found that change was facilitated by reciprocal relationships between providers and recipients and mutual understanding of needs, whereas both provider and recipient turnover hindered the implementation of new initiatives.

Finally, although implementing promising interventions in new contexts has been seen as more efficient than developing totally new interventions for each context, achieving a good fit to the host setting is also crucial (Fendt-Newlin et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2021). When transporting interventions from one country or cultural context to another, the need for adaptation might emerge for several reasons, including differences related to culture, legislation, population, economics, as well as political and service systems. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that welfare services are organized differently around the world depending on their overall ideology and orientation (Schnurr & Slettebø, Citation2015). Current literature focuses on transporting evidence-based, i.e., well-defined, manualized interventions (such as parenting interventions) (Baumann et al., Citation2015; Gardner et al., Citation2016; Schoenwald, Citation2008; Sundell et al., Citation2014), while less is known about adapting non-manualized interventions (such as the RSW and other practice models) that allow for more adjustment and transformation. However, it is important to note that this kind of flexibility can increase the complexity of the implementation (Skivington et al., Citation2021).

Government initiative to implement the systemic practice model (SPM)

While social services in the United States are delivered within various contractual and collaborative networks between public, nonprofit, and for-profit agencies (Smith, Citation2012), in a Nordic country such as Finland, social services are primarily organized by local municipalities (from 2023, by new wellbeing services counties) with government support. However, in Finland, the relationship between central government and local municipalities is complex, as the system aims both to support freedom and democracy at the local level and also to harmonize and regulate services centrally in order to promote the equality of all citizens (Kröger & Burau, Citation2011).

These characteristics are reflected in the context of the SPM. Following the high-profile death of an 8-year-old girl subject to child protection plan in 2012, the Finnish government launched a comprehensive children’s service reform that was to be implemented in 2016–2018. The key stakeholders in the central government perceived the RSW model as a promising solution in reforming child welfare and the model was initially implemented as part of the reform. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health funded the initiative, while Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (henceforth, the Institute) was responsible for creating the Finnish adaptation and supporting its initial implementation, for example, by organizing a seven-day training of trainers (ToT) and four coaching sessions as well as seminars and support materials targeted at local trainers and leaders. The purpose of the ToT was to offer free training to a select number of participants who would, in turn, train the local teams. Approximately half the trainers were social work practitioners, whereas the other half were family therapists. In turn, 31 municipal children’s service sites (henceforth, agencies) located in 14 of the 19 Finnish regions aimed to implement the model in practice between the autumn of 2017 and the summer of 2018 among 52 teams.

The SPM is a Finnish adaptation of the RSW model (Goodman & Trowler, Citation2012), which incorporates systemic family therapy into child and family social work. In addition to the RSW and SPM, other examples of practice models include Solution Based Casework from the US and Signs of Safety from Western Australia. During the past two decades, practice models that are embedded in a particular theory and practice approach, have become increasingly popular in multiple countries, e.g., the US, Australia, and the UK and other European countries (e.g., Gillingham, Citation2018; Laird et al., Citation2018). Simultaneously, more structured EBPs are increasingly being adopted in child welfare in many countries (Gilbert et al., Citation2011). The RSW model was developed at the Hackney children’s service agency in London from 2008. The original model initiated a whole system change that completely redesigned who does what within the agency to improve the quality of practice (Goodman & Trowler, Citation2012).

While conventional child protection teams consist primarily of several social workers and a team manager, the RSW model involves the restructuring of teams to include a social worker(s), a systemically trained family therapist as a clinician, a consultant social worker (CSW) as a team leader, and a unit coordinator, who manages the team’s administrative tasks. This systemic team holds weekly team meetings, i.e., supervision sessions, in which practitioners reflect on family cases with systemic thinking and techniques (e.g., drawing a genogram) as well as plan interventions to conduct more purposeful practice with families. Moreover, social work practitioners are expected to apply systemic techniques to their practice, for which they receive training and coaching. In the UK, CSWs and social workers received separate and longer trainings in systemic practice (e.g., 9 days for CSWs in Bostock et al., Citation2017), whereas in Finland these practitioners received a joint team-based training for six days. Previous research indicates that the RSW model, particularly high-quality systemic supervision, improves the quality of direct social work practice (Bostock et al., Citation2019; Forrester et al., Citation2013). However, to date, there is no evidence of the effectiveness of the model in improving outcomes for children and families (Isokuortti et al., Citation2020).

In terms of system-contextual factors related to the RSW model’s implementation in the UK, both Bostock et al (Citation2017, Citation2022). and Laird et al. (Citation2018) have identified tensions between the therapeutic-oriented RSW and the overall child protection service environment, as the latter contains adversarial and coercive elements. Regarding the organizational context, previous research has shown that stability in leadership can help sustain the achieved change (Bostock & Newlands, Citation2020; Bostock et al., Citation2017). By contrast, a lack of clarity over responsibilities between intermediary organizations and service leaders (Bostock et al., Citation2017) as well as managers’ differing knowledge of the model and a failure to adjust the initiative to other organizational practices and available resources (Laird et al., Citation2018) have been found to impede RSW implementation.

Finally, a previous evaluation of the SPM by Isokuortti and Aaltio (Citation2020) focusing on implementation at team and family levels found high variability in fidelity (i.e., the extent to which the intervention was delivered as intended) across 23 implementation sites in Finland. The results indicated that a lack of clarity over systemic social-work practice, insufficient training, and inadequate resources and leadership had hindered the implementation, whereas coaching and positive experiences of the SPM were facilitating factors. The current study provides an opportunity to investigate similarities and differences in the views of Finnish leaders and social workers and compare and contrast the system and organizational context factors affecting the model’s implementation in Finland and the UK.

Materials and methods

Study design and theoretical frameworks

In order to analyze the implementation process and related stakeholder views in-depth, the study adopted a qualitative approach. The research was influenced by realist evaluation (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997), a theory-driven form of evaluation embedded in realist philosophy of science that seeks to understand how and why programs work in different contexts. Realist evaluation embraces the complexity of implementation processes and suggests that the mechanisms of a given program will only operate in the right context. Furthermore, Pawson (Citation2013) stresses that this context is highly complex and involves multiple layers that interact and influence each other. The current study focuses on the system and organizational context of the SPM.

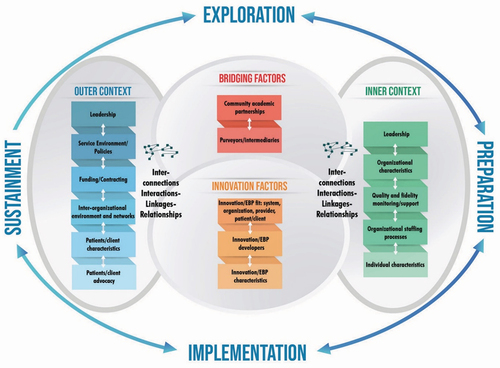

In order to investigate different contextual factors in detail and guide data analysis, the study used the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) Framework. Originally developed by Aarons et al. (Citation2011), the EPIS framework is a widely known conceptual model, which illustrates the key factors that influence the implementation of empirically, supported interventions in publicly funded settings serving children and families. The revised framework, which is based on a systematic review on the use of the EPIS by Moullin et al. (Citation2019), comprises four key components (four implementation phases, inner and outer context factors, innovation factors, bridging factors), described below in .

Figure 1. The revised EPIS framework by Moullin et al. (Citation2019).

According to Moullin et al. (Citation2019), the framework outlines four phases of the implementation process: exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment. In the exploration phase, the implementers aim to identify a suitable innovation for implementation that can address recognized needs. After deciding on the innovation, the implementers move to the preparation phase, which focuses on planning and preparing the change effort (i.e., identifying potential barriers to change, developing an implementation plan, and preparing implementation supports). In the implementation phase, the actual implementation begins as the innovation is introduced to the system and/or organization along with the planned implementation supports, such as training. Finally, the sustainment phase concerns maintaining the innovation with fidelity over time. The current study spans from the exploration to initial implementation phase and refers to the “implementation process or effort” when describing the whole process.

Furthermore, the EPIS framework identifies contextual levels and factors comprised of the outer system context and the inner organizational context. These outer factors (i.e., the external environment and inter-organizational relationships between entities) and inner factors (i.e., intra-organizational characteristics) may affect the implementation process across multiple phases. According to Moullin et al. (Citation2019), the outer context involves six constructs: service environment/policies, funding/contracting, leadership, inter-organizational environment and networks, patient/client characteristics, and patient/client advocacy. In turn, the inner context contains the following five constructs: organizational characteristics, leadership, quality and fidelity monitoring/support, organizational staffing processes, and individual characteristics. The interplay between outer and inner contexts reflect the complex, multilayered, and highly interactive nature of the implementation environment of public services.

As Moullin et al. (Citation2019) state, the framework also includes distinct innovation factors: innovation developers, innovation characteristics, and the innovation’s fit with the context. Finally, bridging factors concern the interconnectedness of and relationships between outer and inner context entities. This is constructed as community-academic partnerships and purveyors/intermediate stakeholders who aim to support the implementation process. The overall aim of the present study is to analyze the above-mentioned factors associated with the implementation process. In order to apply the EPIS framework precisely, this study seeks to analyze how Moullin et al. (Citation2019) EPIS factor constructs (i.e., operationalized definitions) are manifested in interviews with national and local stakeholders.

Participants and sampling

The research data consist of qualitative interviews and relevant policy and implementation documents. The sample (n = 31) is comprised of persons who led the implementation effort at the national level and at the local level in various agencies. The national stakeholders (n = 8) interviewed for the study were key actors in central government, such as government officials and model advocates, developers, disseminators, and ToT/TA providers. At the local level, the study focused on 23 stakeholders: service managers (n = 6), locally based, nationally trained trainers (n = 9), and consultant social workers leading systemic teams (n = 8). These local stakeholders were identified from three purposefully selected sites that granted a permission for the overall research project. The sites were large (<100 000 habitants in each site) but geographically disparate: site 1 was situated in Southern Finland, site 2 in Eastern Finland and site three in Central Finland. Sites 1 and 3 implemented the model in four teams, whereas site 2 performed the implementation in one team. Two interviewees performed dual roles in the process; thus, they participated in two interviews related to each group: one manager also worked as a consultant social worker, whereas one model developer also provided training at one site. Given that these individuals are included in both sub-samples, they are counted twice in the total sample. describes the study’s national and local-level participants.

Figure 2. Illustration of stakeholders interviewed for the study at the team, organization, and system levels. Note: CSW = a consultant social worker.

The documents (e.g., descriptions of the field visits to the UK, notes on the RSW model adaptation process, and government documents on the children’s service reform) provided helpful background information on, for example, the implementation timeline, aims, stakeholders, and funding, and thus supplemented the interview data.

Procedure

After interviewing the model developers and disseminators, the rest of the national stakeholders were identified by using a snowball technique (i.e., the researcher asked the interviewees who else participated in transportng, adapting, and disseminating the model). The local stakeholders were identified with the help of a research contact person (usually a manager) and invited to participate in the interviews.

Out of a total of 17 interviews, 8 were focus groups and 9 were individual interviews. While focus groups can be used to create interactions which provide deep insights into consensus and conflict in the views and experience of participants, individual interviews are useful when discussing more sensitive issues, or in situations where a group dynamic might prevent expression of different views (Moore et al., Citation2015). Principally for these reasons, local stakeholders such as managers, consultant social workers, and trainers were interviewed in groups of two to four along with their peers at the site, whereas individual interviews were used for national stakeholders. However, three exceptions were made. First, the leaders at site 1 were interviewed individually, because finding a mutual interview time appeared challenging. Second, given that site 2 involved only one implementation team, its consultant social worker was interviewed individually. Third, from the national stakeholders, the ToT providers were interviewed in a group as they worked as a team in contrast to other national stakeholders.

Ethical approval for the overall research project was granted by the National Institute of Health and Welfare Research Ethics Committee (2017–09). All the participants were informed about the research by e-mail as well as verbally in the interview. They also signed a consent form concerning their participation and the audio recording. The researcher designed the interview protocols and conducted all interviews with the participants in January – September 2018. With the exception of the trainers’ interview at site 1, which was conducted at the beginning of the implementation, the data were collected between five and seven months after the commencement of the implementation at the site. The interviews lasted between 65 and 153 minutes. All the interviews were conducted face-to-face and pseudonymized for the purpose of analysis. The interviews focused on the stakeholders’ experiences and views of, for example, the Finnish adaptation, preparing and planning the change effort, implementation supports, and the potential use of the model in the future (see supplementary materials for interview protocols).

The study tests the EPIS framework with this data. Examples of questions used in the analysis of outer and inner context were: “When and how was the decision regarding the model’s implementation made?,” How did you prepare for the implementation?,” “What has gone well in the implementation of the model?,” and “What has been challenging?” The questions concerning the model were generated from the Diffusion of Innovations theory (Rogers, Citation2003) and addressed the model’s relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. Finally, examples of questions addressing bridging factors were: “Could you describe the training of trainers that you received?” and “What kind of national support, training, and materials would support the implementation?”

Data analysis

The data were investigated using theoretical thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013), which involves the following six analytic steps: (1) familiarizing oneself with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. The qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti 9 was used in the analysis. First, all transcriptions were read and coded line by line. Second, initial codes were generated deductively based on the EPIS framework and complemented with inductively generated codes. When coding the material, quotations concerning potential factors influencing the implementation were grouped into 1) EPIS factors, 2) the EPIS phases mentioned above, and 3) either “facilitators” or “barriers.” Four EPIS factors (i.e., outer context, inner context, innovation factors, and bridging factors) functioned as the main themes.

Third, the coded text segments were re-read and checked with query and code co-occurrence tools. In particular, the systematic use of key EPIS factors throughout the material was reviewed and refined. Fourth, the codes referring to potential implementation determinants were analyzed and refined, and overlapping codes were merged or deleted with query and code-co-occurrence tools. Fifth, the codes were analyzed in thematic groups and connected to more detailed EPIS constructs defined by Moullin et al. (Citation2019, pp. 12–13) to determine sub-themes (see ). The purpose here was analyze which of the EPIS constructs emerged from the data and how this occurred. The author consulted other researchers when reviewing and defining the themes in order to advance consistent use of the EPIS framework in the analysis. Sixth, the themes identified in the analysis, together with relevant extracts, were reported, and the results were interpreted and reflected on with reference to the EPIS framework and previous research. The author translated the citations (reported within quotation marks) selected for this paper into English. To increase participant anonymity and the readability of the text, the interviewees’ identities are not marked within the in-text citations.

Table 1. Example of generating the theme “innovation factors” through thematic analysis.

Results

Across the EPIS domains, multiple factors influenced the SPM implementation at system and organizational levels. summarizes the identified EPIS constructs and key findings.

Table 2. EPIS constructs identified from the data.

Outer context

This section analyzes the implementation environment external to the agencies involved.

Service environment and policies

The interviewees discussed two topics related to service environment and policies: the political environment and the similarities and differences between Finnish and English child protection service systems.

Although all national stakeholders felt grateful to the government’s support, they perceived that the governmental term of office (four years) created a short timetable, with funding available only for this period. Nonetheless, they felt that politicians held high expectations of achieving “long-lasting change” during the initiative. Another challenge related to parallel change initiatives included in the government program. Although the national stakeholders acknowledged the benefits of an entire system change, some considered that the multi-component children’s service reform dominated the timetable and cut funding from other initiatives, such as the SPM implementation, as it seemed “just like a small part.” In terms of the even larger system social and health care reform, one interviewee worried that the combination of the reorganization of services and pressure to save costs would represent a “death sentence” for the implementation.

The national stakeholders, in particular, noted that they had familiarized themselves with the original RSW model in Hackney and the English system. Many felt that “the basic problems [were] the same” in English and Finnish child protection services. The perceived similar problems were, for example, increased bureaucracy, working alone, and an excessively reactive and juridical approach. For this reason, the national stakeholders especially supported the model’s whole system approach. In turn, the differences identified in the interviews related to legislation, social work education, service culture, and demographics. However, as discussed further, the adaptation process did not include a clear needs and fit assessment to guide the intervention selection.

Funding and contracting

According to the interviews, both national and local stakeholders operated in a context of highly limited resources, which they felt impeded the implementation. Many interviewees, however, seemed so accustomed to the current context of austerity that they could not even imagine another kind of situation. Based on the interviews, it seemed central government had invited only a small number of staff members to participate, and they were able to spend only part of their work time on the initiative (maximum 30%). Furthermore, staff turnover reflected these limitations and illuminated the vulnerability of the system, in which large projects become the responsibility of a few individuals. Likewise, several agency managers struggled with a “continuous lack of resources” and worried that high caseloads would sabotage the whole change effort. Nevertheless, many felt powerless to change these circumstances because funding decisions were primarily political and often conflicted with other priorities. Considering the limited resources available from central government, the national stakeholders considered obtaining the ToT from private stakeholders a cost-effective solution, as it could achieve a large impact at a relatively low cost.

As noted in the interviews and government documents, because the ministry offered funding to interested agencies within the broader children’s service reform, agencies were required to implement three other child-protection-related change efforts in addition to the SPM to receive funding for improving child protection services at all. Given that the description of the Finnish adaptation had not been published at the time the agencies sought funding, these local stakeholders possessed little information about the model and were thus unaware of what they had agreed to. Many managers interviewed for the study also criticized the tight schedule of the government initiative and unclear information on funding allocation.

Leadership

Based on the interviews, challenges in planning, preparing, and monitoring the nationwide implementation initiative appeared to be connected to the “actions and skills” of the implementation leadership and also to the “massiveness” of the broader children’s service reform and to limited central government resources. Essentially, one key stakeholder noted, “we have not done enough planning or, in general, did not allocate enough resources for it.” When asked about specific implementation structures, the national stakeholders explained that central government lacked a detailed implementation plan, clear support structures at the beginning of the project, such as a national steering group for the model’s implementation, and a risk analysis of potential implementation barriers. As one key stakeholder remarked, “we have just gone with the flow.” This strategy resulted in “emergent” implementation leadership, meaning that the national stakeholders were required to react to emerging issues and specify the model along the way.

Initially, the key stakeholders were prepared for significantly fewer SPM implementation sites but ultimately disseminated the model widely throughout the country. On one hand, several stakeholders considered that if the model had been implemented at only a few sites, it would have lacked nationwide impact and might soon have been forgotten after the project. On the other hand, many of them felt that the extensive nature of the SPM implementation effort impeded their ability to support and monitor the implementation in the agencies involved.

Overall, many national and local stakeholders described the “terrible hurry” associated with the initiative, which hampered preparation work. One national stakeholder argued that the overall implementation process appeared “jerky” with inconsistent “speed up and slow down” periods that created the feeling that there was no “permission to stop and make long-term plans”. Based on the local stakeholders’ interviews, it seemed that this kind of leadership style originated at the government level and eventually created the impression in local agencies that it was “unplanned.” As one trainer observed, “if it starts a certain way, it tends to remain that way in the system”. The interviewees hypothesized that the problems at the national level had “trickled down” to the agencies and created a vicious cycle that generated new implementation barriers.

Despite the challenges, most national stakeholders felt positive about the initiative and considered that it was important to proceed “boldly” with it. One key stakeholder interviewed for the study stressed that the change initiative was “an experiment” and that “all experiences were important,” as it provided local practitioners with “a feeling of what it would be like to work differently.” Some felt that the SPM implementation initiative provided “a window of opportunity” for the whole child protection field, while others felt that these expectations were “messianic” and a fantasy and that the implementation was incapable of solving all the problems related to child welfare.

Inter-organizational environment and networks

In terms of relationships between governmental entities, most stakeholders interviewed for the study understood their roles clearly and hoped for even closer relationships to aid the process. In turn, to share best practices and align implementation efforts, several managers and trainers sought to promote active collaboration between agencies.

The Finnish stakeholders also collaborated with the RSW model developers and Hackney local authority practitioners, who described the model and its potential implementation barriers and best practices. Despite the knowledge acquired from this collaboration, one interviewee felt frustrated that Finnish implementers had failed to acknowledge both these barriers and warnings about “cherry picking” UK practices without sufficient attention to implementation issues in Finland. The key stakeholders also noted that they did not collaborate with the original developers when modifying the model to the Finnish context. Some interviewees suggested that adapting the original English training sessions to the Finland context might have provided better training outcomes, as the English practitioners had refined their training package over a number of years: “I just keep wondering why we are trying to reinvent the wheel here in Finland.”

Innovation factors

Innovation developers and disseminators

Based on the documents and interviews related to initial encounters with the original model, one field visit to London by an NGO-initiated project seemed particularly influential, as it resulted in enthusiasm and persistent advocacy to advance the model’s implementation in Finland. The RSW model was received positively among Finnish stakeholders, as illustrated by one interviewee: “it suddenly struck me that this [the RSW model] is what we need.” According to several national stakeholders, the model seemed to spark general interest and appeal among key stakeholders who could influence decision-making at the national level, and eventually a government agency “grabbed” the model. When a funding opportunity emerged, they suggested that it be integrated into the government initiative. Given that the model was “something the government want[ed],” the decision was confirmed, and “no other models were seriously considered,” as one key stakeholder noted. Another interviewee remarked that “I could not tell you why it was precisely this model; it was just that needs and opportunity matched.”

Subsequently, the Finnish adaptation, the SPM, was created and documented in a collaborative, government-led workshop process involving 19 participants – primarily model advocates, child welfare practitioners, and experts but also a small number of service users and academics. One of the key stakeholders produced a description of the Hackney model and related research that was utilized in the creation of the SPM. In addition, the interviewees mentioned utilizing, for instance, Goodman and Trowler’s (Citation2012) description of the RSW model and workshop participants’ “background experiences and understanding” when preparing the model for implementation. The government-led working group then published a definition of the SPM adaptation, which one interviewee called “a general level description” of the model, including its basic principles and preconditions.

The interviews indicate that the SPM was intentionally structured to be flexible in terms of its further adaptation to local contexts. Many reasoned that inclusion and adherence to “the basic principles” of the RSW model was important, because endless adaptation would be confusing and counterproductive. However, when asked about the most important elements, the key stakeholders named different features. As a matter of principle, most national stakeholders were hesitant to introduce procedures that would support the fidelity of the model (e.g., adhering to a specific team structure). They noted that the Institute could not demand a specific structure from the municipal agencies, who held legal responsibility for child protection cases, and thus were forced to accept potential variation in the delivery. Some stakeholders also predicted that Finnish child welfare agencies would oppose a mandated structure, whereas a flexible structure would encourage them to implement the model. Furthermore, one key stakeholder explained that the Finnish adaptation was in the development phase and thus “not yet finished.” Moreover, several stakeholders found the related evaluation research important and believed that the evaluators “could compare which version work[ed] best.”

Innovation characteristics

Altogether, the model was largely accepted by the interviewees. The national stakeholders reported that the following features of the model supported its utility in Finland: 1) positive experiences and previous research from Hackney child welfare (Forrester et al., Citation2013; Munro & Hubbard, Citation2011), 2) the focus on relationship-based practice and a therapeutic approach instead of case management, 3) sharing case responsibility to support social workers’ work-related well-being, 4) the comprehensiveness of the model, and 5) the possibility of standardizing social work practice. Likewise, the local-level implementers found the model useful and particularly emphasized its relationship-based approach and shared decision-making.

Based on the analysis, the interviewees differed in their views on the clarity of the model. While one national stakeholder wondered, “how such a clear model could result in so many different versions,” another noted that it would be important to “clarify what those core components are.” In general, it seemed that the model was clear in theory but challenging to implement in real-world settings. Moreover, while several managers were concerned about the continuous evolution of the model, some trainers and consultant social workers were unsure about how best to integrate systemic family therapy into real-world child protection practice. Furthermore, many consultant social workers interviewed for the study felt that their own role and that of the coordinator in the systemic team were somewhat unclear, whereas all interviewees perceived that the clearest element in the model was the clinician’s involvement. Altogether, most local stakeholders were critical about the limited availability of information describing the model and the consequent need to address this lack of clarity locally.

Innovation fit

Innovation fit generated divergent results in the interviews. As many national stakeholders found that the underlying problems in two systems were similar, they felt that the model would fit well in Finland. In turn, one trainer stressed that “one cannot bring an English version directly to Finland.” However, although some local stakeholders questioned whether the model could work with all social workers and service users, most interviewees at all levels largely accepted the integration of a therapeutic approach into child protection social work. Thus, hesitancy about the model’s fit seemed to relate merely to its aim to guide all stages and aspects of practice and to its particular structure instead of to possible contextual differences. Yet, some believed that the therapeutic approach might be too intense for those practitioners with a case management focus, whereas others felt that the model would mean returning to a form of social work practice used decades ago.

According to the model developers and advocates, the primary difference between the SPM and the original RSW model was the implementation of a team-based model (Finland) in contrast to the introduction of systemic change in the whole organization (Hackney). Some also remarked that the RSW units involved fewer social workers than the Finnish teams; moreover, the coordinators in Finland had often completed a higher education degree in social services. Furthermore, in Finland, social workers, rather than consultant social workers, were responsible for cases, while UK practitioners had received longer training in systemic practice. Based on the interviews, the model also evolved during the initial implementation. For example, the Finnish systemic teams began to invite families to the team meetings, which were used as practitioners’ reflective spaces in the UK. Essentially, some national stakeholders mentioned that Finnish family therapists were more familiar with this kind of dialogical approach.

Bridging factors

In the context of this study, the Institute aimed to serve as a purveyor that provided the ToT and coaching for the trainers and leaders. On one hand, many national stakeholders were “optimistic” about the ToT and stressed the importance of bringing together like-minded “early adopters”. On the other hand, several identified several challenges to the delivery connected to limited planning, wide dissemination, and the vague description of the model. Indeed, one key stakeholder in central government remarked that “we lacked a clear understanding of the content of the trainers’ training and we did not have enough time to think about it;” therefore, they were forced to adopt “an optimistic, here we go” mentality and delegate the main responsibility for planning to the ToT providers.

Nonetheless, while the ToT providers were prepared for a smaller initiative and intimate “process training” they ended up groups containing as many as 40 participants. Moreover, the key stakeholders presumed that the agencies would have been better-prepared for the initiative, but, as discussed further, local stakeholders, including trainers, possessed very little information about the model in the preparation phase. As the model was in the development phase, the ToT providers noted that they were unsure “how to integrate family therapy/the systemic side into this [child protection practice], so it probably remained a separate thing for the social work trainers.”

Based on the experiences of trainers, the problems in the ToT were related to “disjointed” and changing training content, a hectic learning atmosphere that felt like “uncontrollable chaos,” and insufficient training materials. In addition, many felt that the model’s core elements, with their underlying theories and practice applications were unclear, especially the integration of systemic family therapy into social work practice.

Finally, most managers regarded the workshops, i.e., TA provided by the Institute, as a useful way of collaborating and learning about the experiences of other agencies. However, many wished they had received more support, especially when preparing for the initiative. One manager also argued that the Institute should have involved the local stakeholders more in planning the overall initiative, as it implied a new approach to practice.

Inner context

The focus now shifts to analyzing the implementation processes in the local agencies.

Organizational characteristics and leadership

In particular, the importance of organizational readiness for change emerged strongly from the interviews. For instance, some interviewees stressed that other organizational changes, such as moving to new offices, might negatively affect the practitioners’ motivation. Furthermore, leaders’ engagement with and vision of the change effort were recurring topics. From the three agencies participating in the study, site 2 stood out in terms of strong leadership commitment, a long-term vision for change, careful preparation, and close collaboration between trainers and practitioners, which the latter experienced as “warm support”. In turn, at other sites, some agency managers felt distant from the implementation effort, whereas some consultant social workers and trainers experienced the high pressure associated with the practical delivery of the model without sufficient support or a proper plan from senior staff.

The interviews also indicated that ongoing collaboration between managers, practitioners and trainers and a practical approach to training were associated with higher satisfaction. In turn, a lack of these features seemed to engender the opposite effect. Some interviewees felt that the training ought to have been longer, while others were satisfied with six days. Some consultant social workers maintained that they should have been provided with separate training to facilitate systemic supervision.

Quality and fidelity monitoring and support

Principally, the interviewees shared two differing views of fidelity to the model. For some, it signified the effort to standardize social work practice, while, for others, it involved allowing a highly flexible approach to implementation. Most interviewees at both the national and local level understood that a shared way of working could increase consistency, thereby allowing the same quality service to be provided for all service users. Indeed, many were concerned about high variation in preexisting service quality and noted that practice was often based on a “gut feeling” instead of evidence. Despite these views, several national and local stakeholders emphasized the advantages of free modification of the model because “organizations and teams are different.” Some also highlighted flexibility as one of the model’s benefits.

Given that no manuals were available for implementing the model, the agencies relied on the description of the Finnish adaptation and implementation support from central government. Many local trainers ultimately constructed most of their own training materials, as no fixed training package existed and they received nationally coordinated material too late. One national stakeholder mentioned that tailoring training “might not be a bad thing” if it aimed to increase its fit with the context but suspected that the trainers had solved “the mess” as best they could. However, this situation was highly stressful for the trainers:

We actually started to become worried that we would not receive any material, no training program, that training would be different at all the sites, and the idea that we were now doing this kind of national change in social work, and this kind of model would be disseminated, and each trainer had to invent it. (Trainer, site 2)

Despite the challenges, all the trainers interviewed for the study felt that they had been able to share new insights with the participants and integrate systemic family therapy theories into social work practice. Simultaneously, they acknowledged that teaching some key tools and techniques, such as formulating hypotheses, was not sufficiently covered in the training. In turn, many managers mentioned the constant need to balance between the ideal model and that allowed by limited funding, which required continuous negotiation with both practitioners and decision-makers.

Organizational staffing processes and individual characteristics

Based on the interviews, most local stakeholders considered successful recruitments and staff retention key to successful implementation. In particular, many argued that choosing motivated teams to launch the initiative and hiring knowledgeable clinicians with an understanding of child protection practice enhanced the functioning of the systemic team. Conversely, many interviewees were concerned about the influence of staff turnover on maintaining the change and about disseminating the model to other less motivated teams. Finally, although internal trainers possessed valuable knowledge about their organization and implementation teams, some noted that their other work responsibilities continued during the implementation period, resulting in a significantly increased overall workload.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the reasons and strategies the RSW model’s adaption to Finland and explore the system and organizational factors associated with its implementation. Both barriers and facilitators in multiple EPIS domains (outer and inner context, innovation and bridging factors) were identified from the analysis. Essentially, most national and local stakeholders interviewed for the study widely accepted the model itself and displayed high motivation for its implementation. Although the government initiative succeeded in rapidly disseminating the model around the country, particular challenges were related to the Finnish adaptation and its national implementation strategy.

Disseminating a vaguely described model that allowed high flexibility in implementation without the well-defined, high-quality ToT resulted in extremely variable local training and, presumably, wide variation in the practical implementation of the model (Isokuortti & Aaltio, Citation2020). This strategy also conflicted with the initiative’s aims to standardize practice to provide high-quality services to all families involved with child welfare. As Meyers et al. (Citation2012) note, unless practitioners possess in-depth understanding of an intervention’s core components and its effective implementation, they require carefully designed support and guidance in adapting it to new contexts. This is crucial because a failure to implement the core components as intended ultimately influences the intervention’s effectiveness (Durlak & Dupre, Citation2008). Furthermore, limited planning and preparation of an extensive initiative like the SPM with inadequate resources during a single term of office formed a problematic outer implementation context. Moreover, its success was further hampered by the need to manage several parallel change efforts. Altogether, such an ad hoc approach understandably created challenges for the ToT and diminished the local agencies’ ability to succeed in the model’s implementation.

The study indicated that these implementation barriers percolated down from central government to the local agencies, thereby creating multiple unintended outcomes. Because the expansion of the initiative and the lack of clarity of the model challenged the development and delivery of the ToT, responsibility for translating the model into real-world settings remained with the trainers, who eventually felt unequipped to train the systemic teams. The managers, in turn, struggled with the same challenges faced by central government while aiming to organize the minimal resources available for their teams. Consequently, the consultant social workers felt that the responsibility for actual change ultimately remained with the teams, in particular with the clinician striving to integrate systemic family therapy into the team’s practice. Taken together, these findings reveal the long “implementation chains” through which interventions proceed before eventually impacting service users’ every day lives (Pawson, Citation2013, pp. 35–36). Thus, they also provide a potential explanation for social workers’ implementation-related stress and limited change in practice (Isokuortti & Aaltio, Citation2020).

One unanticipated finding was that the interviewees identified relatively little conflict arising from the introduction of an innovation from another service system. This finding may reflect the interviewees’ positive perceptions of the model’s basic principles or their openness to testing new approaches in general. It also suggests that only minor adaptation from the original model and its training might be necessary. For this reason, undertaking moderate modifications in the initial phase and considering further adaptations based on the research results would have been helpful (see also Moore et al., Citation2021). In particular, modification of systemic supervision should be performed carefully, as previous research has found a statistically significant relationship between supervision quality and the overall quality of direct practice (Bostock et al., Citation2019). Essentially, if the intervention core components have been identified, the current implementation literature recommends that adaptations should preserve these components to maintain the fidelity to the intervention (Meyers et al., Citation2012).

Furthermore, the findings are contradictory to UK evaluations which have indicated high satisfaction with systemic training (Bostock et al., Citation2017; Laird et al., Citation2018). Simultaneously, it is important to note that the agency leaders and practitioners in the UK received training and coaching from a social enterprise, whose founders led the systemic change in Hackney (Bostock et al., Citation2017). Although the current research and previous evaluations stress the importance of the clinician’s support (Bostock et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2022; Isokuortti & Aaltio, Citation2020), the findings also indicate that systemic change cannot solely rely on their expertise.

One surprising difference related to discussions of risk adversity in England and Finland. While previous studies in the UK (Bostock et al., Citation2017, Citation2022; Laird et al., Citation2018) have found that maintaining systemic practice is challenging in a broader child protection system that remains risk adverse and punitive, such difficulties were not highlighted in either the present study or the previous Finnish evaluation (Isokuortti & Aaltio, Citation2020) as such. It is possible, therefore, to hypothesize that the risk-focused “child protection” (e.g., UK) and support-focused “family service” (e.g., Finland) orientations identified in previous research (Gilbert, Citation1997; Gilbert et al., Citation2011) still exist to some extent.

Many of the implementation determinants identified in the study, such as careful preparations, intervention clarity, stakeholder engagement, sufficient resourcing, and ongoing support are aligned with the key implementation determinants identified by earlier studies (Albers & Shlonsky, Citation2020; Lambert et al., Citation2016; Sanclimenti et al., Citation2017; Weeks, Citation2021). Given that achieving change in human services is challenging, many interventions encounter implementation problems that diminish the intervention’s desired effect (Durlak & Dupre, Citation2008). Regarding the RSW, while Bostock et al (Citation2017, Citation2019). found evidence of a change in practice, a longitudinal study by Bostock and Newlands (Citation2020) highlighted the difficulty of retaining the model as it was originally intended. As such, the findings of this study are not unique. While the demand for empirically supported and cost-effective practices has considerably advanced the international transportation of social interventions (Newlin & Webber, Citation2015; Schnurr & Slettebø, Citation2015; Sundell et al., Citation2014), the current research emphasizes the importance of comprehensive support for achieving purposeful and long-lasting change in real-world settings. In particular, the findings, although preliminary, have important implications regarding large-scale implementation efforts in human services in various systems that will be discussed in the following section.

Implications for policy and practice

Implementation research provides the means to improve service outcomes; therefore, the field should utilize this research to improve their implementation knowledge and skills (Albers et al., Citation2021; Bunger & Lengnick-Hall, Citation2019; Metz et al., Citation2021; Weeks et al., Citation2022). Implementation frameworks, such as the EPIS, can be used in designing and longitudinally evaluating future change initiatives throughout all phases of their implementation (Moullin et al., Citation2019).

Regarding purveyors and model developers in all countries, developing a clear intervention description (including providing a foundation for adaptations) as well as high-quality training, coaching and a manual are important in implementing empirically supported interventions in human service organizations (e.g., Meyers et al., Citation2012). Above all, applying the program theory (i.e., a clear description of an intervention’s core components and mechanisms that produce desired outcomes) consistently in the training and support material is likely to result in consistency in its application at the level of practice. Regarding the SPM, clarifying the ToT contents and the Finnish adaptation (i.e., systemic supervision and systemic practice), developing materials to guide practice, and establishing fidelity criteria for the model would aid its implementation and evaluation in the future.

In turn, leaders, policymakers and other stakeholders in decisive roles ought to devote time and effort to intervention selection and early preparation as these increase the likelihood of successful implementation (Meyers et al., Citation2012; Saldana et al., Citation2012). As illustrated in the present study, the implementation decision-making is complex and may be influenced by various stakeholders and sources. Although public concern over tragic events, such as child deaths, may create pressure to develop quick solutions (Holmes & Mcdermid, Citation2013; Willging et al., Citation2015), decision-makers and implementers should aim to select research-supported interventions or fund research-informed intervention development conducted in collaboration with researchers to achieve sustainable change (see also Carnochan McBeath et al., Citation2017; Skivington et al., Citation2021). Careful decision-making is particularly essential in government initiatives, as these implementation processes potentially exert long-lasting and large-scale effects on practice.

To achieve best possible outcomes, leaders and policymakers should assess the intervention’s research evidence, fit to the host context with diverse stakeholders and the overall feasibility of implementation is important prior to taking the implementation decision (see also Meyers et al., Citation2012; Moore et al., Citation2021). Therefore, strengthening the decision-makers’ research literacy and working with researchers is important. Obtaining buy-in from key stakeholders in early stages is also crucial as local leaders and frontline implementers eventually take the decision to change their practice or maintain the status quo. Furthermore, extending academic practice collaboration to cover the entire process from the initial planning phase to full evaluation could enable all members to buy into the research project, thereby providing a more complete perspective on the conducting of research and the interpretation of findings (see, for example, Moran et al., Citation2020). Intermediary stakeholders may also play a role in aiding decision-making and supporting adaptation and implementation (Albers et al., Citation2021).

When transporting interventions to new contexts, as in the present study, implementers should also carefully assess whether the intervention requires modification and utilize adaptation frameworks to achieve a good fit with the host setting (e.g., Fendt-Newlin et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2021, Stirman et al., Citation2019; Sundell et al., Citation2014). Regarding adaptation, Moore et al. (Citation2021) stress the importance of (1) assessing the rationale for the intervention and considering the intervention-context fit of existing interventions, (2) planning for and undertaking adaptations, (3) planning for and undertaking piloting and evaluation, and (4) implementing and maintaining the adapted intervention at scale. Working with diverse stakeholders is seen as a cross-cutting principle (Moore et al., Citation2021). Thorough operationalization and assessment of adaptations is also crucial, or else the nature of new innovation is likely to remain unclear (Meyers et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, working with the original developers can facilitate the implementation of the intervention as intended in the new setting. Such collaboration not only aids the identification of core components but also integration of other key practice tenets and ontological assumptions of the intervention to the host context. Overall, adaptation research is a new and developing field that has a potential to support decision-makers and human service leaders by offering systematic approaches and guidance to adaptation (see also Copeland et al., Citation2022).

Regarding the organizational level, the study emphasizes the importance of aligning project goals with available resources as well as avoiding several parallel initiatives targeted at the same service providers (see also Albers et al., Citation2021; Garcia et al., Citation2019; Lambert et al., Citation2016; Sanclimenti et al., Citation2017). For this reason, it seems necessary to prioritize change initiatives, i.e., to implement fewer but higher quality initiatives. In order to promote an organizational culture and climate that aid improvement efforts, Glisson (Citation2015) concludes that organizations should aim to utilize the experience of direct service providers, form a psychologically safe work environment, create a transparent process for improvement by allowing constructive criticism, and maintain a focus on improving service users’ well-being. Furthermore, to increase their implementation capacity, organizations should consider forming internal implementation support teams or collaborating with intermediary organizations specialized in implementation support (Albers et al., Citation2021).

In 2021, the SPM was used in 18 of the 19 regions in Finland (Yliruka & Tasala, Citation2022). Although some interviewees in this study mentioned that one of the reasons for choosing the model was that research about it already existed, evidence of its effectiveness is still lacking (Aaltio, Citation2022; Isokuortti et al., Citation2020). In order to avoid adverse effects, future change efforts in human services should proceed carefully from small-scale testing to wider implementation if evaluation results provide evidence that implementation is worthwhile. In other words, implementers need to remember that mainstreaming the intervention should not occur until the last stages in the development and evaluation process (Skivington et al., Citation2021).

Limitations and future research

The present study has shown that implementation research should not only assess actual implementation in frontline practice, but also analyze implementation decision-making and preparation as well as examine the potential outer-context factors that shape implementation outcomes. Although achieving change takes time, the results encourage to carefully examining the early stages of the process. Simultaneously, it is important to collect rigorous follow-up process data from different stakeholders. Regarding the SPM, high-quality process and outcome evaluations are required to test and refine the initial program theory (Aaltio & Isokuortti, Citation2022).

Although an advantage of this study was the collection of data from multiple stakeholders, one challenge concerns the small sample size of government officials and ToT providers. To ensure the participants’ anonymity, the above-mentioned interviewees were grouped with other national stakeholders whenever it was unnecessary to distinguish their specific roles. Moreover, for this reason, interviewee information was not provided in the interview extracts. It should also be noted that the participants spoke freely about implementation-related difficulties and referred to the confidentiality of the interviews. While this trust is highly valued, it is important to acknowledge that critical observations cannot be excluded from the analysis. Another potential limitation was that the same researcher was responsible for both gathering and analyzing the data. Nonetheless, in order to limit potential bias, the interpretation of the results was reviewed by senior researchers. Furthermore, the precise and operationalized definitions of EPIS factors used in the study can increase the rigor and objectivity of the evaluation. Finally, although the anticipated positive results of the change effort and the stakeholders’ varied perceptions may have created certain expectations about the findings, the current study aimed to approach the data with the maximum possible level of objectivity.

Conclusion

This study has shown that thorough preparation, a clear intervention description, and high-quality implementation support are crucial for achieving the desired change in practice. By contrast, limited planning and the implementation of an evolving intervention heightens the risk of adverse outcomes. Improving implementation skills and knowledge as well aiming for active collaboration between intervention developers, practice stakeholders, and researchers can improve the quality of implementation processes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Mirja Satka, Nelli Hankonen, Maija Jäppinen, Michael J. Austin and Elina Aaltio for their critical comments and edits to the manuscript. I am also grateful to Matthew Billington for help with language revision and to Joanna Moullin for advice with the application of the EPIS framework. Finally, I would like to thank all study participants who contributed to this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2024.2304897

References

- Aaltio, E. (2022). Effectiveness of the Finnish Systemic Practice Model for Children’s Social Care. A Realist Evaluation (JYU Dissertations 571, 2022: 131) [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Jyväskylä. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-9224-8

- Aaltio, E., & Isokuortti, N. (2022). Developing a programme theory for the systemic practice model in children’s social care: Key informants’ perspectives. Child & Family Social Work, 27(3), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12896

- Aarons, G., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

- Albers, B., Metz, A., Burke, K., Bührmann, L., Bartley, L., Essen, P., & Varsi, C. (2021). Implementation support skills: Findings from a systematic integrative review. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(2), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520967419

- Albers, B., & Shlonsky, A. (2020). When policy hits practice - learning from the failed implementation of MST-EA in Australia. Human Service Organisations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(4), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1779893

- Baumann, A. A., Powell, B. J., Kohl, P. L., Tabak, R. G., Penalba, V., Proctor, E. K., Domenech-Rodriguez, M. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2015). Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent-training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Children & Youth Services Review, 53, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.025

- Bostock, L., Forrester, D., Patrizo, L., Godfrey, T., Zonouzi, M., Bird, H., Antonopoulou, V., & Tinarwo, M. (2017). Scaling and deepening reclaiming social work model: Evaluation report. Department for Education.

- Bostock, L., & Newlands, F. (2020). Scaling and deepening the reclaiming social work model: Longitudinal follow up. Evaluation report. Department for Education.

- Bostock, L., Patrizio, L., Godfrey, T., & Forrester, D. (2022). Why does systemic supervision support practitioners’ practice more effectively with children and families? Children and Youth Services Review, 142, 106652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106652

- Bostock, L., Patrizo, L., Godfrey, T., & Forrester, D. (2019). What is the impact of supervision on direct practice with families?. Children and Youth Services Review, 105, 104428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104428

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. A practical guide for beginners. SAGE Publications.

- Bunger, A., & Lengnick-Hall, R. (2019). Implementation science and human service organizations research: Opportunities and challenges for building on complementary strengths. Human Service Organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance, 43(4), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1666765

- Cabassa, L. (2016). Implementation science: Why it matters for the future of social work. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(Suppl 1), S38–S50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1174648

- Carnochan McBeath, B., Austin, M. J., & Austin, M. J. (2017). Managerial and frontline perspectives on the process of evidence-informed practice within human service organizations. Human Service Organisations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 41(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2017.1279095

- Copeland, L., Littlecott, H. J., Couturiaux, D., Hoddinott, P., Segrott, J., Murphy, S., Moore, G., & Evans, R. E. (2022). Adapting population health interventions for new contexts: Qualitative interviews understanding the experiences, practices and challenges of researchers, funders and journal editors. British Medical Journal Open, 12(10), e066451–e066451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066451

- Durlak, J. A., & Dupre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

- Fendt-Newlin, M., Jagannathan, A., & Webber, M. (2020). Cultural adaptation framework of social interventions in mental health: Evidence-based case studies from low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019879943

- Forrester, D., Westlake, D., McCann, M., Thurnham, A., Shefer, G., Glynn, G., & Killian, M. (2013). Reclaiming social work? An evaluation of systemic units as an approach to delivering children’s services. University of Bedfordshire.

- Garcia, A. R., DeNard, C., Morones, S., & Eldeeb, N. (2019). Mitigating barriers to implementing evidence-based interventions: Lessons learned from scholars and agency directors. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.005

- Garcia, A. R., Myers, C., Morones, S., Ohene, S., & Kim, M. (2020). It starts from the top”: Caseworkers, supervisors, and TripleP Providers’ perceptions of implementation processes and contexts. Human service organizations: Management. Leadership & Governance, 44(3), 266–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1755759

- Gardner, F., Montgomery, P., & Knerr, W. (2016). Transporting evidence-based parenting programs for child problem behavior (age 3-10) between countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1015134

- Gilbert, N. (1997). Combatting child abuse: International perspectives and trends. Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (2011). Child protection systems: International trends and orientations. Oxford University Press.

- Gillingham, P. (2018). Evaluation of practice frameworks for social work with children and families: Exploring the challenges. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 12(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2017.1392391

- Glisson, C. (2015). The role of organisational culture and climate in innovation and effectiveness, human service organisations: Management. Leadership & Governance, 39(4), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1087770

- Goodman, S., & Trowler, I. (2012). Social work reclaimed: Innovative frameworks for child and family social work practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Holmes, L., & Mcdermid, S. (2013). How social workers spend their time in frontline children’s social care in England. Journal of Children’s Services, 8(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-03-2013-0005

- Isokuortti, N., & Aaltio, E. (2020). Fidelity and influencing factors in the systemic practice model of children’s social care in Finland. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105647

- Isokuortti, N., Aaltio, E., Laajasalo, T., & Barlow, J. (2020). Effectiveness of child protection practice models: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108, 104632–104632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104632

- Kröger, T., & Burau, V. (2011). Retuning the Nordic welfare municipality. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 31(3/4), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443331111120591

- Laird, S. E., Morris, K., Archard, P., & Clawson, R. (2018). Changing practice: The possibilities and limits for reshaping social work practice. Qualitative Social Work, 17(4), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325016688371

- Laird, S. E., Morris, K., Archard, P., & Clawson, R. (2018). Changing practice: The possibilities and limits for reshaping social work practice. Qualitative Social Work : QSW : Research and Practice, 17(4), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325016688371

- Lambert, D., Richards, T., & Merrill, T. (2016). Keys to implementation of child welfare systems change initiatives. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(2), 132–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2015.1113226

- McBeath, B., Chuang, E., Carnochan, S., Austin, M. J., & Stuart, M. (2019). Service coordination by public sector managers in a human service contracting environment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0899-1

- Metz, A., Albers, B., Burke, K., Bartley, L., Louison, L., Ward, C., & Farley, A. (2021). Implementation practice in human service systems: Understanding the principles and competencies of professionals who support implementation. Human Service Organisations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 45(3), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2021.1895401

- Meyers, D., Durlak, J., & Wandersman, A. (2012). The quality implementation framework: A synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

- Moore, G., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. UK Medical Research Council (MRC).

- Moore, G., Campbell, M., Copeland, L., Craig, P., Movsisyan, A., Hoddinott, P., Littlecott, H., O’Cathain, A., Pfadenhauer, L., Rehfuess, E., Segrott, J., Hawe, P., Kee, F., Couturiaux, D., Hallingberg, B., & Evans, R. (2021). Adapting interventions to new contexts—the ADAPT guidance. BMJ, 2021(374), n1679. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1679

- Moran, N., Webber, M., Dosanjh Kaur, H., Morris, D., Ngamaba, K., Nunn, V., Thomas, E., & Thompson, K. J. (2020). Co-producing practice research. The connecting people implementation study. In L. Joubert & M. Webber (Eds.), The routledge handbook of social work practice research (pp. 353–367). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429199486

- Moullin, J., Dickson, K. S., Stadnick, N. A., Rabin, B., & Aarons, G. A. (2019). Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science : IS, 14(1), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6

- Munro, E., & Hubbard, A. (2011). A systems approach to evaluating organisational change in children’s social care. The British Journal of Social Work, 41(4), 726–743. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr074

- Newlin, M., & Webber, M. (2015). Effectiveness of knowledge translation of social interventions across economic boundaries: A systematic review. European Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 543–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2015.1025710

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. In the science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. SAGE.