ABSTRACT

Heightened stress levels are experienced and reported by social work practitioners worldwide and issues such as secondary traumatic stress, burnout and compassion fatigue are terms increasingly being used in the context of social work practice. This study sought to investigate factors that influence compassion fatigue as well as compassion satisfaction in social workers. It was conducted in two cities in south India with a sample of 73 social workers. Standardized instruments were administered to assess compassion fatigue as well as compassion satisfaction besides measures to identify the manifestation of stress and resilience in the respondents. Findings indicate high levels of stress and resilience and significant manifestation of compassion fatigue and burnout levels in the sample studied. It was also observed that the interaction effect between resilience and stress significantly explained the manifestation of compassion fatigue but not that of compassion satisfaction. Implications of these findings have been discussed in terms of influencing individual and organizational factors to enhance resilience, deal more effectively with work-related stress, and reduce burnout and compassion fatigue. This will in the long run bode well for the wellbeing of social workers besides potentially impacting the quality-of-service provision.

Practice Points

Social work organizations need to promote measures to ensure manageable workloads, role clarity, adequate resources, and workplace support to employees.

The importance of self-care measures and timely help-seeking is a message that needs to be unequivocally conveyed.

Stress management and resilience-building measures need to be incorporated within the work culture of organizations that employ social workers.

Social work practice in India is considerably different in nature and scope than the regulated, organized and clearly defined functions that characterize it as a profession in Western and developed countries. Social work in India does not enjoy the professional standing, acceptance, and recognition that it does in the West. In fact, some even consider it to only be a “semi-profession” owing to the lack of awareness among the general public and lack of recognition from key stakeholders, including the government (Nair, Citation2015). The absence of an apex regulatory body to oversee practice standards; the lack of a policy for the mandatory licensing of practitioners; and the lack of standardized education are some factors responsible for the rather feeble professional status accorded to social work (Baikady et al., Citation2021). The majority of social workers practice in third-sector organizations in areas relating to mental health, women, and child welfare, working with older people, people with disabilities and community development projects in urban slums and villages (Stanley, Citation2006). The working conditions for social workers by and large tend to be arbitrary, with poor pay scales, lack of progression opportunities, and irregular hours of work. The lack of a clearly specified job profile often demands involvement in sundry activities that are strictly not within the remit of professional social work (Stanley & Mettilda, Citation2016). The social worker functions in an atmosphere characterized by resource constraints and often does not enjoy much autonomy in decision-making. It must be noted that while this is not the situation in all work settings and organizations, it tends to be the predominant scenario in practice. Despite such working conditions that are far from ideal, social workers perform their roles and functions with a high degree of commitment and take pride in the contribution that they make in improving the life of the people and communities that they serve (Stanley et al., Citation2021).

Social work in India as elsewhere is a high-stress profession that involves exposure to vicarious trauma owing to working with people who experience considerable adversity and circumstantial distress. Stress is considered to arise from the disparity between perceived environmental or organizational demands and the individual’s ability to meet and cope with them (Collins, Citation2008; Lazarus and Folkman, Citation1984). Stress experienced in social work practice can be attributed to multiple factors. This could be owing to the characteristics of the individual practitioner, work related or organizational factors and those that relate to the nature of people served and the issues faced by them, or a combination of these. Practitioner attributes include aspects such as resilience, adaptive functioning, organization skills and coping strategies that are deployed in dealing with stressful situations. Work related factors that generate stress for social workers include excessive workloads, working overtime, dealing with role ambiguity/conflict, ethical dilemmas, having to manage unmet personal expectations and negative public perceptions besides low levels of control and poor managerial support (Lloyd et al., Citation2002, Solomonidou & Katsounari, Citation2022).

The issue of resilience becomes important against this background. Emotional resilience has been construed as being the emotional capacity that enables better adaptation to a range of external and internal stressors (Klohen, Citation1996). It has been considered to be the ability to experience negative emotional experiences and to “bounce back” from them by adapting to the changing demands of stressful situations (Tugade and Frederickson, Citation2004). It is believed that resilience is often underestimated in populations that are exposed to adverse events (Bonanno, Citation2004). This then would be true of social workers who are frequently exposed to crises and trauma as routine events in their professional lives.

It is acknowledged that direct practice with those who are suffering, poor, vulnerable, or underprivileged has adverse psychological consequences for the help providers themselves (Steinheider et al., Citation2019). The work-stress literature has generated a whole set of terminologies such as vicarious trauma (VT), compassion fatigue (CF), secondary traumatic stress (STS), and burnout (BO) to refer to the negative outcomes of exposure to indirect trauma frequently experienced through the population that social workers seek to serve. It would be relevant to examine some of these terms as there seems to be a considerable overlap in their meaning and the tendency to use them interchangeably. Vicarious trauma refers to affective and cognitive symptoms that result from prolonged exposure to traumatized clients and manifests in low levels of motivation, efficacy, empathy, self-esteem, self-perception, and reduced feelings of intimacy, safety, and trust (Baird & Kracen, Citation2006, McCann & Pearlman, Citation1990). Secondary traumatic stress (STS) results from vicariously experiencing trauma through association with those directly encountering the traumatic event(s) (Simon et al., Citation2005). The symptoms of STS resemble those of PTSD and include feeling emotionally numb, reliving the trauma experiences of clients, developing panic-like symptoms when thinking about them outside of work and experiencing increased irritability and difficulty in concentration (Bride et al., Citation2004, Ewer et al., Citation2015). It has also been reported that those experiencing higher STS have poorer physical and emotional health, higher burnout, lower compassion satisfaction and practised fewer self-care behaviors (Shepherd & Newell, Citation2020). Survey data collected from 1,053 public child welfare workers in the US reports that STS is negatively associated with workers’ intention to remain (Kim et al., Citation2024).

“Burnout” as a term has been a popular concept explored in the stress literature of the helping professions including social work and is a state of emotional weariness or physical exhaustion caused by prolonged exposure to stressful or difficult situations (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1982). It has been defined as a feeling of failure and exhaustion or weariness resulting from excess demands on energy, personal resources or workers’ spiritual strength and is characterized by feelings of exhaustion, disenchantment, and a lack of interest in one’s job (Freudenberger & Richelson, Citation1980). Burnout is a three-dimensional syndrome that involves emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and poor personal accomplishment (Gomez-Garcıa et al., Citation2020). The empirical literature on social work burnout has identified a range of work-related factors such as heavy caseloads, low wages, limited resources, time constraints and deadlines, conflict within work climate, ethical predicaments, low work autonomy, role ambiguity, and structural organization of the workplace (Diaconescu, Citation2015; Iacono, Citation2017; McFadden et al., Citation2015; Willis and Molina, Citation2019).

The organizational theory on burnout considers it to be a consequence of organizational and work stressors as well as deficient coping strategies at an individual level (Golembiewski et al., Citation1983). Organizational stressors or risk factors, such as work overload or role ambiguity, precipitate burnout resulting in a decrease in the individual’s organizational commitment and feelings of depersonalization. This is then experienced as low work-related personal fulfillment and emotional exhaustion. It is seen that both the organizational structure as well as the organizational culture negatively impact the organization’s response to employees’ trauma-related distress (Jirek, Citation2020). Other theories such as the demand-resource theory likewise hold burnout to be a consequence of the imbalance between job demands and supportive resources (such as social relationships, and supportive leadership) available at work (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017).

Stamm’s (Citation2002, Citation2009) conceptualization has been used in this study to assess the professional quality of life (ProQOL) in social work practitioners. ProQOL comprises two components: compassion fatigue (CF) which reflects the negative aspects of dealing with trauma and compassion satisfaction (CS) which refers to the positive elements and experiences associated with caring. Larsen and Stamm (Citation2008) likened CS to a sense of fulfillment and gratification experienced by therapists owing to a feeling of having done their work well. CS is made up of three elements: (1) the level of job satisfaction experienced by a practitioner (2) a sense of professional competence and control in dealing with trauma and (3) the level of structural and functional social support available to the practitioner (Stamm, Citation2002). In line with Stamm’s conceptualization, organizational theory holds that burnout is a consequence of organizational and work stressors combined with inadequate individual coping strategies (Golembiewski et al., Citation1983).

Stamm (Citation2010) considers compassion fatigue (CF) to include burnout and STS. While negative outcomes such as exhaustion, frustration, anger, and depression are typical of burnout, negative feelings stemming from fear related to work-related trauma are more typical of STS. Compassion fatigue involves the experience of emotional and physical fatigue due to the chronic use of empathy when dealing with people who experience a significant amount of suffering and distress (Newell & MacNeil, Citation2010). CF may lead to negative psychological consequences for those in the helping professions and is characterized by feelings of fatigue, disillusionment, and worthlessness (Circenisa and Millerea, Citation2011). Resilience has been found to have a significant negative correlation with compassion fatigue and a significant positive correlation with compassion satisfaction (Burnett & Wahl, Citation2015).

Direct social work practice with traumatized populations often has negative outcomes for practitioners in terms of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, vicarious traumatization, and compassion fatigue and hence these are aspects that merit comprehensive empirical investigation (Pryce et al., Citation2007). However, themes such as stress, anxiety, resilience, coping and burnout in social work practitioners are under-researched issues in the Indian context (Stanley et al., Citation2020). We conducted a search of the literature using keywords such as “stress”, “resilience”, “burnout” in “social workers in India” and came across only one study by Stanley et al (Citation2021) which was conducted with women social workers in India. Other studies were conducted with different populations (not specific to social work practitioners) such as social work students (Stanley and Mettildai, Citation2022) frontline healthcare professionals (Patel et al., Citation2021, Yadav and Sahu, Citation2022), human service professionals (Brown et al., Citation2003).

This study will hence add to the nascent literature on these issues within social work settings in India by providing an understanding of aspects relating to stress, burnout, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue and the potential role that resilience plays in terms of influencing the relationship between these variables.

From an organizational perspective, it is important for the management and leadership of social service organizations to gain a better understanding of the complex interplay between these variables in the context of frontline social work practice. This would enable the introduction of organizational initiatives geared toward stress reduction, and the building of resilience, thereby potentially reducing the incidence of compassion fatigue and heightening the experience of compassion satisfaction within practice settings.

This study was framed against this background and seeks to address the following questions:

What is the extent of stress and resilience manifested in social workers?

What is the extent of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction experienced by them?

What is the nature of the relationship among these key variables?

What role do stress, and resilience play in influencing compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction?

We expected to find a negative relationship between stress and compassion satisfaction and a positive relationship of stress with compassion fatigue. Our core hypothesis was that resilience would moderate the effect of stress on both compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction.

Method

Research design

This is a cross-sectional study, that used survey methodology for data collection. The study is of a comparative nature and comparisons have been made among different categories of respondents. The analytical methodology followed is predominantly correlational and the study uses a descriptive design.

Measures

Socio-demographic data and work-related information was collected from the respondents using a self-prepared questionnaire.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) by Cohen (Citation1994) is a widely used psychological instrument that measures the extent to which situations in one’s life are appraised as being stressful. The questions are of a general nature and are relatively free of content specific to any subpopulation group. The ten items in the PSS ask about feelings and thoughts experienced during the previous month and are scored on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “never” to “very often.” Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was computed to be .88, in this study which is considered to be “good” (George and Mallery, Citation2003).

Resilience Scale (RS), developed by Wagnild and Young (Citation1993) assesses an individual’s ability to withstand various stressors, to thrive in adverse situations and to make sense of various challenges. It is a 25-item self-report questionnaire that comprises of 5 sub-dimensions that assess: equanimity (a balanced perspective of one’s life and experiences); perseverance (persistence despite adversity or discouragement); self-reliance (a belief in oneself and one’s abilities); meaningfulness (the realization that life has a purpose); and existential aloneness (the realization that each person’s life path is unique) (Losoi et al., Citation2013). Respondents were asked to state the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with each item on a 7-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All items were positively scored with a score range of 25 to 175 with higher scores indicative of higher resilience. The Cronbach’s alpha of the RS computed in this study was .94 and this is considered as being “excellent” (George and Mallery, Citation2003).

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL; Stamm, Citation2009) is a 30-item instrument that measures the consequences experienced by those who work with others experiencing distressful circumstances and are exposed to suffering and trauma. The instrument has three component sub-scales that measure compassion satisfaction, STS (Secondary Traumatic Stress) and burnout. The latter two sub-dimensions together constitute compassion fatigue. Respondents are asked to rate how frequently they experienced certain feelings about their work over the previous 30 days. We computed the reliability coefficient for the ProQOL in this study as .87. This is considered to be “good” (George and Mallery, Citation2003).

Data collection

We contacted the District Social Welfare Board and obtained a list of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) registered with them in two cities of Tamilnadu in south India namely Tiruchirappalli and Thanjavur. We approached the heads of these organizations, explained the study, and sought permission to contact social workers employed in these agencies. Hard copies of the questionnaire were then given to the social workers who consented to participate in the study. Data was collected during the prevalence of COVID (January-September 2021) when restrictions were in place, and it was difficult to contact respondents. A time was agreed upon for the collection of completed responses. Of the 118 questionnaires thus circulated, 73 completed questionnaires were received and included for data analysis. We thus had a response rate of 62%. In many instances, we had to make repeated visits to collect the completed questionnaires. This was particularly difficult owing to the then-prevailing circumstances due to COVID.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical clearance from the Ethics Review Panel of PMIST (Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science and Technology), where one of the authors is based. A participant information sheet outlining the purpose and nature of the study was given to all potential respondents at the time of preliminary contact. They were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all of them. Respondents were given the option to drop out of the study at any point without any implications and were told that they would not be contacted thereafter. No personal identification data were collected, and the questionnaires were anonymized.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out with the use of SPSS version 25 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences; IBM Software, Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis involved the use of descriptive statistics besides Karl Pearson’s correlation to establish the association between variables. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses (enter method) were used to identify the predictors of Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue.

Results

Respondents’ background profile

The age of the respondents ranged from 22 to 59 years (M = 34.3; SD = 7.7). The majority of them were married (57.5%) women (54.8%). Their work experience ranged from one to 36 years (M = 9.8; SD = 7.1). The size of their family ranged from having 1 to 9 members (M = 3.6; SD = 1.8). The work profile of the respondents is depicted in . It is seen that the majority of the social workers are employed in the private sector (non-governmental organizations, hospitals, educational institutions) and very few in the non-statutory sector. They work in a range of projects such as rehabilitation programmes, counseling services and community development projects.

Table 1. Distribution of respondents by their work profile (n = 73).

Profile of respondents on key variables

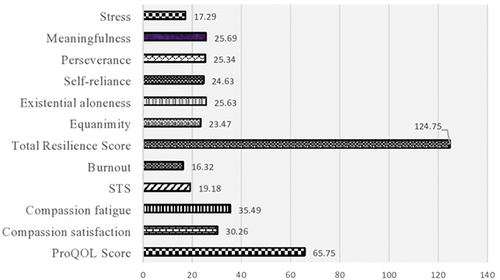

depicts the mean score profile of the respondents on all the key variables of the study. The minimum and maximum scores along with their mean and Standard Deviation are portrayed in . The respondents were placed in the “high” and “low” categories on each variable based on its mean score for the sample.

Table 2. Mean score profile of respondents on key variables (n = 73).

Bivariate relationships among variables

Karl Pearsons correlation coefficients were computed for the various variables of the study to examine bivariate relationships among them (). It needs to be noted that while these correlations are not indicative of cause-effect relationships among the variables, they do indicate a tendency to mutually influence one another positively or negatively. As expected, the sub-dimensions of various key variables correlated significantly among themselves and with the total score (e.g., Total resilience score with its sub-dimensions). It is important to note that three of the background variables (age, years of work and family size) did not enter into significant correlations with any of the other key variables of the study. Further, in line with our hypothesis, the total stress score showed a positive correlation with compassion fatigue. However, we did not obtain a significant correlation between the stress scores and those of compassion satisfaction. Also, the stress scores did not enter into any significant correlation with the total resilience and ProQOL scores (or any of their sub-dimensions). CF scores also correlated negatively with the existential aloneness sub-dimension of resilience. CS scores correlated positively with the total resilience score and all its sub-dimensions. Finally, the table indicates that the ProQOL score correlated positively with the total resilience score and its sub-dimensions of meaningfulness and equanimity.

Table 3. Correlation matrix for key variables and select demographic factors.

Mean score comparison based on gender and living status

The respondents were then compared among themselves based on their gender and living status {(living with a spouse versus those who were single (unmarried, widowed, divorced)} on the key variables of the study. Results indicated a significant difference between male and female respondents only on stress levels (Male: Mean = 16, SD = 4.5; Female: Mean = 18.21, SD = 3.9; t = 2.19, p < .05) but not on any of the other key variables. The mean scores indicate higher stress levels in female respondents. Further, it was seen that in terms of their living status, there was no statistically significant difference between those living with their spouses and respondents who were single.

Predictors of compassion fatigue

To ascertain the extent to which stress and resilience influenced the manifestation of compassion fatigue in the respondents, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was carried out. In the first step compassion fatigue was treated as the dependent variable and both stress and resilience entered as independent variables in the model. The two independent variables were standardized (z scores) to avoid spurious results owing to multicollinearity. The resulting model was not significant (R2 = .08, F(2, 70) = 3.09, p = .05). To test if the interaction effect between the two independent variables explained the manifestation of compassion fatigue, a moderator variable was then created. This was computed by multiplying the standardized stress and resilience scores. In the next step of the regression analysis, this interaction term was added to the previous regression model. This model demonstrated strong evidence of being statistically significant (R2 = .17, F(3, 69) = 4.83, p < .01). While the direct effects of both stress and resilience did not attain statistical significance, it was noted that there was strong evidence that the interaction effect between the two was statistically significant (b = 3.48, SE = 1.25, β = .31, t = 2.78, p < .01). The increased R2 value in the second model indicates that this increased variance can be attributed to the interaction term (stress-by-resilience) introduced in this model. The three long straight arrows in the path diagram () indicate the standardized beta coefficients while the curved arrows on the left show bivariate correlations. Overall, this analysis indicates that stress and resilience by themselves do not explain the manifestation of compassion fatigue in the respondents, however when the two interact together, they significantly explain the extent to which compassion fatigue is experienced.

Predictors of compassion satisfaction

A similar regression analysis was carried out this time with CS as the dependent variable and stress and resilience as independents (). The resulting model demonstrated very strong evidence of statistical significance (R2 = .22, F(2, 70) = 10.01, p < .001). While the total stress score was not extracted as a significant predictor of CS in this model, very strong evidence of statistical significance was obtained for the total resilience score as a predictor of CS (b = .13, SE = .03, β = .47, t = 4.43, p < .001). To test if the interaction effect between the two independent variables, explained the manifestation of compassion satisfaction, a moderator variable was then created. This was computed by multiplying the standardized stress and resilience scores. In the next step of the regression analysis, this interaction term was added to the previous regression model. This model also presented very strong evidence of being statistically significant (R2 = .26, F(3, 69) = 8.08, p < .001). However, in this model, none of the independent variables (stress, resilience) or the moderator (stress x resilience) were extracted as significant predictors. Overall, the results of these regression analyses show that while resilience in itself significantly determines the manifestation of CS, its interaction with stress does not in any way influence CS.

In line with our core hypotheses, it was seen that resilience moderates the influence of stress on CF. However, contradictory to our hypothesis, stress does not in any way influence the manifestation of CS.

Discussion

High levels of stress were noted in the majority of the respondents. This is consistent with studies that have explored stress in social workers (e.g., Lloyd et al., Citation2002; Schraer, Citation2015; Stanley et al., Citation2021). As pointed out earlier the typical Indian social worker functions in an atmosphere that lacks clarity, deals frequently with non-responsive bureaucratic systems and lacks resources and the authority to make and/or influence decisions. These factors and others could manifest in the high levels of stress experienced by the majority. It was also seen that the stress score showed a positive correlation only with compassion fatigue. The literature indicates that CF tends to be a reaction to stress.

A positive finding in this study was that the majority of the respondents were placed in the high resilience category. Except for equanimity (a balanced perspective of one’s life and experiences), the majority of the respondents are in the “high” category on all the other sub-dimensions of resilience. This suggests that the high levels of resilience could potentially buffer the adverse effects of the high-stress levels experienced by the majority of the respondents. While we did not obtain a statistical correlation between the overall stress and resilience scores, it appears that despite high levels of stress experienced, most social workers tend to function (and perhaps survive) among harsh conditions of practice. Compassion satisfaction scores correlated positively with the total resilience score and all its sub-dimensions, indicating the mutual influence that CS and resilience exert on one another. While the overall quality of life was low in the majority, we also observed that the ProQOL score correlated positively with the total resilience score. This suggests that resilience plays a key role in the overall perception of one’s professional quality of life. Almost half the sample experienced high burnout levels and the rates of STS, CS and CF were also high in a significant number of the sample. These findings suggest the importance of intervention strategies to deal with stress, burnout, and CF and to undertake initiatives that could enhance CS and thereby ultimately impact positively on the overall professional quality of life.

It was also seen that gender influences levels of stress, more so in female practitioners. This finding is consistent with that of a study by Choi (Citation2011) that reports a marginally significant relationship between gender and secondary traumatic stress (STS) levels in Australian social workers and also indicated that female social workers are more likely to have higher levels of STS than their male counterparts. In the Indian socio-cultural context, the female social worker functions in a highly patriarchal society and is expected to manage domestic commitments as well as balance these with the demands of her work.

Age, years of work and family size did not enter into significant correlations with any of the other key variables in this study and thus do not seem to be important. For instance, while one would expect that with increasing age and years of experience, perceived stress levels would potentially be low, this has not been borne out by our data. This is consistent with the finding that the relationship between age and shared traumatic stress in social workers is negligible and statistically insignificant (Tosone et al., Citation2015). Marital status also did not make a difference in terms of stress, resilience or the adverse consequences experienced. While we expected the marital relationship to provide a buffer against stress, this has not been borne out by our data.

It was also seen that while stress and resilience by themselves did not explain the manifestation of compassion fatigue in the respondents, the interaction between the two determines the extent to which CF is experienced. On the other hand, while the interaction between resilience and stress does not determine the manifestation of compassion satisfaction, resilience by itself is a significant contributor of CS. This suggests a complex interplay between stress and resilience vis-à-vis the experience of both CF and CS. While the organizational theory considers two sets of factors (organizational and individual) in relation to the manifestation of burnout, this study indicates that it is the interaction between the two (stress in interaction with resilience) that determines the outcome of CF and not each by itself. This we feel is a significant finding that adds to our understanding of the dynamic interplay between stress, resilience and the adverse consequences experienced.

It is also a matter of concern that in terms of burnout, STS, and CF a sizable number of respondents in this study have been placed in the “high” category, indicating that a sizable population of social workers experience these adverse consequences associated with exposure to stressful events. It has been suggested that CF, burnout, VT, and STS constitute a homogenous group of negative outcomes related to secondary exposure to stressful situations (Voss Horrell et al., Citation2011).

Implications

In a nutshell this study indicates that there is a need to deal with high stress levels in social workers, take steps to enhance their resilience and promote a better quality of professional life by decreasing compassion fatigue and enhancing levels of compassion satisfaction. This is important as compassion satisfaction is associated with heightened work performance, positive attitudes to work, enhanced sense of worth, and greater hope for positive outcomes (Kulkarni et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, CF can take a toll on both; the caregiving professional as well as the workplace, causing decreased productivity, sickness absenteeism, and higher practitioner turnover (Potter et al., Citation2010). Burnout plays a key role in disengagement among front-line social workers (Travis et al Citation2016) and social workers who are less stressed and burnt out will be able to provide better care, be more productive and be better able to connect emotionally with their clients (Maslach & Goldberg, Citation1998).

As demonstrated by this study the interaction between stress and resilience is responsible for the manifestation of CF and hence a combination of strategies at the personal and organizational levels would be the best approach for the promotion of professional resilience (Shepherd & Newell, Citation2020). What is required are efforts to deal with these issues using a simultaneous two-pronged approach. First, there is the need to strengthen practitioner characteristics through the provision of better training and job orientation programs particularly in terms of problem-solving approaches and crisis intervention techniques. The importance of self-care and seeking help are messages that need to be strongly conveyed. Meditation, yoga, mindfulness, and other stress management procedures could ease the pressure experienced by practitioners and there is evidence in the literature that attests to their benefits. Spirituality has also been shown to insulate against the effects of workplace stress, to aid resilience and to contribute to overall well-being (Brelsford & Farris, Citation2014, Collins & Long, Citation2003).

Second, there is tremendous scope for organizations to take steps to improve the work ethos and ensure that adequate resources and support are made available. This includes the provision of regular supervisory guidance, updated technological systems, clearly defined job roles, opportunities for training, upgradation of skills and career advancement to name a few. Only a multi-pronged effort will ensure good mental health and well-being in social workers and ensure that their morale remains high and that they are able to provide their best to people who require their services.

Further, employees’ perceptions and evaluations of stress are influenced by their interaction with those in leadership positions (Culbertson et al., Citation2010). An authentic leadership has been considered to affect the sense of prosperity experienced by employees by providing them with a healthy and ethical work environment and can also affect individual vitality by expressing empathy (Mortier et al., Citation2016). A transformational leadership style has been associated with positive thriving at work (Hildenbrand et al., Citation2018). Such a leadership style includes elements of expectation and motivation and can influence employees’ perception and appraisal of stress and other characteristics of their work situation (Cavanaugh et al., Citation2000, Gong et al., Citation2009).

Limitations

The findings of this study need to be viewed against the cultural context of professional social work practice in India, which varies within the country, and across organizational settings and so the scope for generalizing the findings is fairly limited.

Data was collected during the prevalence of COVID-19 when conditions of practice were significantly altered. We were however unable to delineate the extent to which our findings reflect the impact of Covid in terms of the variables studied.

This study does not specifically assess stress associated with particular life domains (e.g., work or family life) and the Perceived Stress Scale that we have used is a fairly generic measure of an individual’s perception and feelings of how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives to be (Cohen et al., Citation1983). As such it would be erroneous to attribute the manifestation of CF and burnout to entirely work-related factors. However, we also maintain that at an individual level, it may not always be possible to parse out stress associated with specific life domains (work, family) and as such the use of a generic stress scale is justified.

The cross-sectional nature of this study reflects the attitudes and opinions of the respondents at the point of data collection, and as such does not capture the dynamics associated with changing job requirements and the dynamic nature of social work practice over time.

We also acknowledge that the work experience of social workers is influenced by organizational factors such as work ethos, supportive arrangements, caseloads, and other such aspects, potentially influencing the variables we have studied. However, these specific work-related factors and their influence on the variables we have studied have not been considered.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution in helping to understand factors experienced by professional social work practitioners in India, as similar previous investigations have not included the range of variables that we have included in this study. It specifically contributes to our understanding regarding the manifestation of stress, resilience, and burnout in social workers. Our findings suggest that ameliorative measures need to be taken to reduce work stress, strengthen resilience and reduce compassion fatigue in order to enhance the mental health and well-being of social workers in practice. This will certainly improve the benefits that accrue to the clientele that they serve.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baikady, R., Sheng-Li, C., & Channaveer, R. M. (2021). Eight decades of existence and search for an identity: Educators perspectives on social work education in contemporary India. Social Work Education, 40(8), 994–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1773780

- Baird, K., & Kracen, A. (2006). Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: A research synthesis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070600811899

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

- Brelsford, G. M., & Farris, J. R. (2014). Clinician’s guide to self-renewal. In R. Wicks & E. A. Maynard (Eds.), Religion and spirituality: A source of renewal for families (pp. 355–365). Oxford University Press.

- Bride, B. E., Robinson, M. M., Yegidis, B., & Figley, C. R. (2004). Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731503254106

- Brown, N. C., Prashantham, B. J., & Abbott, M. (2003). Personality, social support and burnout among human service professionals in India. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 13(4), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.734

- Burnett, H. J., Jr., & Wahl, K. (2015). The compassion fatigue and resilience connection: A survey of resilience, compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among trauma responders. Faculty Publications, 17(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.4172/1522-4821.1000165

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

- Choi, G.-Y. (2011). Organizational impacts on the Secondary Traumatic Stress of Social Workers assisting family violence or sexual assault survivors. Administration in Social Work, 35(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2011.575333

- Circenisa, K., & Miller, I. (2011). Compassion fatigue, burnout and contributory factors among nurses in Latvia. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2042–2046.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1994). Perceived stress scale. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists, 10, 1–2.

- Collins, S. (2008). Statutory social workers: Stress, job satisfaction, coping, social support and individual differences. British Journal of Social Work, 38(6), 1173–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm047

- Collins, S., & Long, A. (2003). Too tired to care? The psychological effects of working with trauma. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00526.x

- Culbertson, S. S., Fullagar, C. J., & Mills, M. J. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and wellbeing. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020720

- Diaconescu, M. (2015). Burnout, secondary trauma and compassion fatigue in social work. Revista de Asistenta Sociala, 14(3), 57–63.

- Ewer, P. L., Teesson, M., Sannibale, C., Roche, A., & Mills, K. L. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of secondary traumatic stress among alcohol and other drug workers in a ustralia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(3), 252–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12204

- Freudenberger, H., & Richelson, G. (1980). Burnout: The high cost of high achievement. Anchor Press.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference(4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Golembiewski, R. T., Munzenrider, R., & Carter, D. (1983). Phases of progressive burnout and their work site covariants: Critical issues in OD research and praxis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 19(4), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/002188638301900408

- Gómez-Galán, J., Lázaro-Pérez, C., Martínez-López, J. Á., & Fernández-Martínez, M. D. M. (2020). Burnout in Spanish security forces during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238790

- Gong, Y., Huang, J. C., & Farh, J. L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Academic Management Journal, 52(4), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43670890

- Hildenbrand, K., Sacramento, C. A., & Binnewies, C. (2018). Transformational leadership and burnout: The role of thriving and followers’ openness to experience. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000051

- Jirek, S. L. (2020). Ineffective organizational responses to workers’ secondary traumatic stress: A case study of the effects of an unhealthy organizational culture. Human Service Organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(3), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1722302

- Kim, J., Barbara Pierce, B., & Park, T. K. (2024). Secondary traumatic stress and public child welfare workers’ intention to remain employed in child welfare: The interaction effect of job functions. Human Service Organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance, 48(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2023.2263518

- Klohen, E. (1996). Conceptual analysis and measurement of the construct of ego resiliency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 1067–1079. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.1067

- Kulkarni, S., Bell, H., Hartman, J. L., & Herman-Smith, R. L. (2013). Exploring individual and organisational factors contributing to compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout in domestic violence service providers. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 4(2), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2013.8

- Lacono, G. (2017). A call for self-compassion in Social Work Education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(5), 454–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2017.1377145

- Larsen, D., & Stamm, B. H. (2008). Professional quality of life and trauma therapists. In S. Joseph & P. Linley (Eds.), Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress (pp. 275–293). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lloyd, C., King, R., & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11(3), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230020023642

- Losoi, H., Turunen, S., Wäljas, M., Helminen, M., Öhman, J., Julkunen, J., & Rosti-Otajärvi, E. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Finnish version of the resilience scale and its short version. Psychology, Community & Health, 2(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5964/pch.v2i1.40

- Maslach, C., & Goldberg, J. (1998). Prevention of burnout: New perspectives. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 7(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80022-X

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1982). Burnout in health professions: A social psychological analysis. In G. Sanders & J. Suls (Eds.), Social psychology of health and illness (pp. 227–251). Erlbaum .

- McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140

- McFadden, P., Campbell, A., & Taylor, B. (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systemic literature review. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1546–1563. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct210

- Mortier, A. V., Vlerick, P., & Clays, E. (2016). Authentic leadership and thriving among nurses: The mediating role of empathy. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(3), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12329

- Nair, T. K. (2015). Social work in India: A semi-profession. Niruta Publications. Bangalore.

- Newell, J. M., & MacNeil, G. A. (2010). Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue: A review of theoretical terms, risk factors, and preventive methods for clinicians and researchers. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(2), 57–68.

- Patel, B. R., Khanpara, B. G., Mehta, P. I., Patel, K. D., & Marvania, N. P. (2021). Evaluation of perceived social stigma and burnout, among health-care workers working in COVID-19 designated hospital of India: A cross-sectional study. Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior, 4(4), 156–162.

- Potter, P., Deshields, T., Divanbeigi, J., Berger, J., Cipriano, D., Norris, L., & Olsen, S. (2010). Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14(5), E56–62. https://doi.org/10.1188/10.CJON.E56-E62

- Pryce, J. G., Shackelford, K. K., & Pryce, D. H. (2007). Secondary traumatic stress and the child welfare professional. Lyceum Books.

- Schraer, R. (2015). ‘Social workers too stressed to do their job according to survey’, Community Care. Available at: http://www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/01/07/stress-stopping-job-social-workerssay/

- Shepherd, M. A., & Newell, J. M. (2020). Stress and health in social workers: Implications for self-care practice. Best Practices in Mental Health, 16(1), 46–65.

- Simon, C. E., Pryce, J. G., Roff, L. L., & Klemmack, D. (2005). Secondary traumatic stress and oncology social work: Protecting compassion from fatigue. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 23(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1300/J077v23n04_01

- Solomonidou, A., & Katsounari, I. (2022). Experiences of social workers in nongovernmental services in Cyprus leading to occupational stress and burnout. International Social Work, 65(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872819889386

- Stamm, B. H. (2002). Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion satisfaction and fatigue test. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 107–119). Brunner-Routledge.

- Stamm, B. H. (2009). Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue version 5 (ProQOL). www.proqol.org

- Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale (2nd ed.). Eastwoods, LLC.

- Stanley, S. (2006). Social work education in Tamilnadu: Issues of concern. In M. Thavamani (Ed.), Issues in higher education. (pp. 22–32). Bharathidasan Univ. Pub .

- Stanley, S., & Mettilda, G. B. (2016). Reflective ability, empathy, and emotional intelligence in social work students: A cross-sectional study from India. Social Work Education, 35(5), 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1172563

- Stanley, S., Mettilda, G. B., & Arumugam, M. (2020). Predictors of empathy in women social workers. Journal of Social Work, 20(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318794280

- Stanley, S., Mettilda, G. B., & Arumugam, M. (2021). Resilience as a moderator of stress and burnout: A study of women social workers in India. International Social Work, 64(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818804298

- Stanley, S., & Mettildai, G. B. (2022). Do stress and coping influence resilience in social work students? A longitudinal and comparative study from India. International Social Work, 65(5), 927–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820905350

- Steinheider, B., Hoffmeister, V., Brunk, K., Garrett, T., & Munoz, R. (2019). Dare to care: Exploring the relationships between socio-moral climate, perceived stress, and work engagement in a social service agency. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(3), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2019.1575324

- Tosone, C., McTighe, J. P., & Bauwens, J. (2015). Shared traumatic stress among Social Workers in the aftermath of hurricane katrina. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1313–1329. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43687907

- Travis, D. J., Lizano, E. L., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2016). ‘I’m so stressed!’: A longitudinal model of stress, burnout and engagement among social workers in child welfare settings. British Journal of Social, Work, 46(4), 1076–1095. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct205

- Tugade, M., & Frederickson, B. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320

- Voss Horrell, S. C., Holohan, D. R., Didion, L. M., & Vance, T. G. (2011). Treating traumatized OEF/OIF veterans: How does trauma treatment affect the clinician? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022297

- Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 65–78.

- Willis, N. G., & Molina, V. (2019). Self-care and the social worker: Taking our place in the code. Social Work, 64(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swy049

- Yadav, P., & Sahu, S. (2022). Perceived stress, burnout and compassion fatigue among frontline health workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatric Social Work, 13(1), 32–38.