Abstract

Despite providing objective, benchmark statistics on the condition and progress of U.S. education since 1867, the National Center for Education Statistics has been the center of scrutiny over the last dozen years for its lack of resources and agility as well as for its diminished stature and autonomy. Motivated by the COVID-19 pandemic exposure of NCES’ bureaucratic hurdles, Congress’ interest in reauthorizing the agency and its umbrella organization, and the 2022 National Academies’ report, A Vision and Roadmap for Education Statistics, we explore legislative changes and attendant administrative actions that would contribute to building the trust of respondents who provide data to NCES and users who depend on the agency’s products; our article offers recommendations to that end.

Statistics on the condition of American education were never more needed than during the COVID-19 pandemic; timely and granular data on the reactions of the nation’s schools, teachers, and students as the pandemic unfolded would have been immensely valuable for federal, state, and local governments and the public. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the federal statistical agency with the mission to report on Pre-K-12 and higher education, was not able to respond in a timely way to the new pandemic-generated data needs due to longstanding bureaucratic hurdles, operational inefficiencies, and resource challenges. Not until 18 months after the pandemic’s start with funds provided by Congress did NCES launch the School Pulse Survey to begin meeting the new data demands. Despite the utility of this new survey, NCES still lacks the agility and authority necessary to provide granular, timely, and frequent data on changing educational conditions to inform parents, teachers, students, and policymakers.

Put more starkly, NCES lacks the authority, autonomy, and resources to fully and efficiently carry out the four responsibilities mandated for federal statistical agencies in the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 (hereafter the Evidence Act):

produce and disseminate relevant and timely statistical information;

conduct credible and accurate statistical activities;

conduct objective statistical activities; and

protect the trust of information providers by ensuring the confidentiality and exclusive statistical use of their responses.

Congress and the Administration have the opportunity to address these problems through reauthorization of the 2002 Education Sciences Reform Act (ESRA) and the annual appropriations processes. In this article, the authors (who are former NCES leaders and others with experience in the federal statistical system) urge that Congress act promptly to provide NCES with the resources and authorities it needs to be effective and trusted in producing relevant statistics on education.

Section 1 of our article provides background on NCES and the challenges it has faced historically and continues to confront. Section 2 provides the framework for our recommendations, which are rooted in the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) “Statistical Policy Directive No. 1” and similar statements about the need for federal statistical agencies to be independent and objective. In Section 3, we make three sets of recommendations to facilitate NCES fulfilling its mandated, four fundamental responsibilities, and thereby better provide granular, timely, and frequent education statistics. For the first, we endorse the recent report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Citation2022), especially for NCES to develop a strategic plan, keep abreast of changes in data sources, and be relevant to user needs. In the second set, we make specific recommendations for Congress to provide NCES the authority and professional autonomy to enable NCES to perform fully as a federal statistical agency consistent with OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 1 and the Evidence Act, change the form of appointment of the NCES Commissioner, and authorize a high-level advisory body in a manner determined by the Commissioner. We also recommend the Department of Education take steps to implement these provisions through internal operating procedures. Finally, in our third set of recommendations, we urge measures so that NCES has the resources and wherewithal to effectively and efficiently carry out its work as it relates to staffing levels while also being protected against improper outside influence. Action by Congress and the Administration on our recommendations and those of the National Academies could go a long way toward bolstering NCES’ capabilities to serve the nation. Appendices provide additional background on the federal statistical system and NCES.

1 NCES as a Principal Statistical Agency

NCES is one of 13 principal federal statistical agencies that, along with some 100 other agencies that administer specialized statistical programs, comprise the federal statistical system (see Appendix A).

As with all federal statistical agencies, NCES functions in accord with OMB standards, issued under the legislative authority of the director of OMB, to coordinate the statistical functions that are decentralized across the federal government. A particularly important standard, Statistical Policy Directive No. 1, issued in 2014 and codified in the Evidence Act, requires statistical agencies to produce and disseminate relevant and timely information; conduct credible and accurate statistical activities; conduct objective statistical activities; and protect the trust of information providers by ensuring the confidentiality and exclusive statistical use of their responses (see Section 2). The Directive emphasizes that statistical agencies “must be able to conduct statistical activities autonomously” and must be “clearly separate and autonomous from the other administrative, regulatory, law enforcement, or policy-making activities within their respective Departments.” This directive also requires federal departments to “enable, support, and facilitate federal statistical agencies and recognized statistical units as they implement these responsibilities.” Regrettably, NCES does not have sufficient independence, capabilities, or departmental support to live up to the full responsibilities of a statistical agency.

1.1 Historical Overview

NCES’ history dates to 1867 legislation establishing a “department” whose sole function was to gather statistics and facts needed to report the “condition and progress” of education in the United States. For a century, the agency collected and published data about public schools from states and about higher education from colleges and universities. It missed out, however, on the advances in statistical and survey science that had a major positive impact during the 1930s–1950s on the staffing and functions of such agencies as the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). NCES began a move toward state-of-the-art statistical procedures only in the late 1960s and early 1970s with its development of the longitudinal study, “National Longitudinal Study of the High School Class of 1972,” and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), also known as the “Nation’s Report Card.” NCES, however, continued to lag behind other statistical agencies in internal capacity for design and conduct of surveys and other important statistical functions, relying heavily on external contractors.

In 1986 the National Academies released a study of the Center concluding that it was so deficient as a statistical agency, it should be substantially reformed and, if not, then terminated, and its responsibilities transferred to other government agencies. The report focused the attention of the Department of Education, the statistical community, NCES friends, and the Congress on the need to revitalize the agency (National Research Council Citation1986). The department set out new statistical review procedures in a Secretarial directive; NCES developed new standards to guide the technical quality of its work; and Congress enacted several key provisions in the Hawkins-Stafford Act of 1988 intended to strengthen the agency in line with the National Academies’ recommendations. Those concerns for NCES, the legislative changes made in the Hawkins-Stafford Act, and subsequent legislative changes (mostly weakening NCES professional autonomy and stature) are summarized in Appendix B, The Strengthening and Weakening of NCES.

Since then, NCES’ statistical program responsibilities have grown enormously. It is third largest in terms of funding among the 13 principal federal statistical agencies, with an annual budget totaling around $300 million. However, it has never recovered from its deficit of in-house staff capacity that other statistical agencies developed long ago, and it has always lacked adequate control over the technology services needed for its statistical procedures. Moreover, the enactment of the Education Sciences Reform Act (ESRA) of 2002 and related executive decisions made in implementation of ESRA have diminished NCES’ abilities to conduct its work in a professionally autonomous manner (Elchert and Pierson 2020). Congress’ action in 2011 removing Senate confirmation of the Director’s appointment (Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act, Citation2012) further diminished the agency’s stature, in the view of some observers (Elliott Citation2015).

These changes, and additional ones from operational practices of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES or Institute hereafter) and the department, have once again—as found in the 1986 Academies’ report—placed NCES at risk of falling behind. The recent evidence of NCES’ tardy and inadequate reporting of data relevant to policymakers about the impacts on schools and students of the COVID pandemic should be taken as an urgent warning. Congress, the Executive Branch, and NCES’ friends need to coalesce, as they did in 1987–1988, to help make NCES stronger. It is especially timely that the new National Academies’ report has framed a “vision” for NCES over the next seven years that describes new data opportunities, ways that NCES can strategically plan for its future, and outreach to data suppliers and users that can ensure greater relevance in a changed information environment (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2022). Once again, as with the National Academies’ evaluation in 1986, the 2022 report can serve as an impetus for action.

1.2 Impediments for NCES

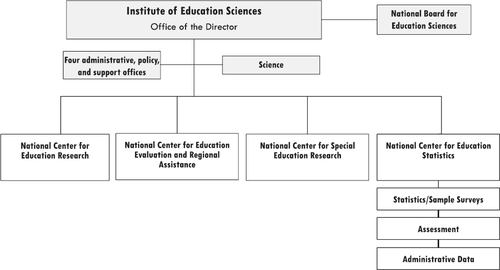

A principal NCES challenge is that the agency cannot use its appropriated funds to hire in-house staff. Instead, staffing is funded by a separate account managed by the IES, the immediate umbrella entity for NCES within the Department of Education (ED). See . The department practice of using a separate account for staff and overhead, which is managed by the Institute or department-wide, may be appropriate for many department functions focused on making grants, providing financial aid to students, or establishing regulations. NCES is different with its mandate to gather, analyze and report information to the public, a more labor-intensive function; moreover, NCES—not grantees, and not contractors—is directly accountable to the public for its products.

Fig. 1 The IES organizational chart, adapted from the IES website (https://ies.ed.gov/help/ieschart.asp).

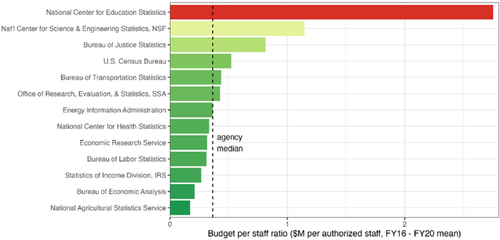

The long-standing curtailment of in-house staff capability has made NCES overly dependent upon contractors for its work. With its limited staff (95 people in total in FY 2021, compared with some 875 employed through contractors as illustrated in (Woodworth Citation2021)), NCES has little flexibility to reassign staff from one project to another or take on new responsibilities. Its budget to staff ratio is nearly $3 million per FTE, which is eight times the median for the principal federal statistical agencies (see ). In addition, the hiring process, which must involve Institute and department actions or approvals, often results in lengthy delays in replacing experienced staff. For example, the NCES unit that is home to the Condition of Education and other major reports and was staffed with ten people in 2015, currently employs only five staff, none of whom has more than three years of tenure in the unit.

Fig. 2 NCES has nine full-time equivalent contractors (red) per employee (green) Source: 2021 presentation of NCES commissioner Lynn Woodworth to Quarterly Meeting of Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics. The data include the long term contractors for NAEP, but do not include the short term field staff used during administration of NAEP.

Fig. 3 NCES budget to staff ratio is eight times the typical federal statistical agency. Source: Data compiled from “Statistical Programs of the United States Government,” an annual publication of the Office of Management and Budget.

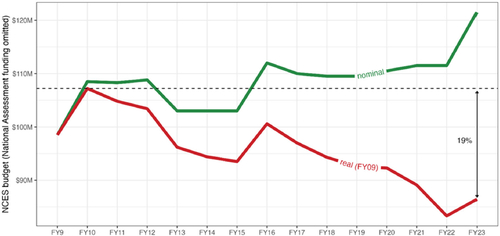

This situation, along with a flat budget for NCES’ survey programs since 2010 (a 19% loss in purchasing power—see ) and the necessary negotiations for appropriate contracts, led agency leadership to forego timely data on the pandemic’s effect on school operations and personnel. As of this writing, NCES does not have staffing (agency or contractor staff) for the Fast Response Survey System or School Survey on Crime and Safety.

Fig. 4 The NCES statistics budget (60% of the NCES total FY23 budget of $306 million, omitting assessment funding) is down 19% since a FY10 high after adjusting for inflation. Source: Nominal budget compiled from “analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government,” an annual publication of the Office of Management and Budget. Real budget calculated with GDP deflator data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (Bureau of Economic Analysis Citation2023).

New IES initiatives further burden NCES operations as well as its standing as an autonomous federal statistical agency. For example, following congressional direction in the 2023 omnibus appropriations act (FY2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act Citation2022), IES proposed the National Center for Advanced Development in Education within the National Center for Education Research, an education research version of “DARPA,” the storied advanced research facility of the U.S. military (Department of Education Citation2023). Staffing it, however, must be done using the IES program administration budget set in the annual appropriations process. Unless that line item is increased, staffing new IES entities or increasing the number of staff for one IES entity means decreasing staff for another. With more staff than the rest of IES combined, NCES has often been the offset.

NCES faces conflicting demands in its efforts to meet federal government-wide norms for confidentiality protection as set out in the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (2022) (CIPSEA). Strong protections that were part of the Hawkins-Stafford legislation in 1988 were transferred from NCES to IES, but in a weaker form under the Education Research Sciences Act of 2002. Also, NCES was singled out in the Patriot Act of 2001 to permit the Attorney General’s access to individually identifiable information that is relevant to an authorized investigation concerning national or international terrorism (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001 Citation2002). While this authority has never been invoked, it still requires that the Center affirm appropriately worded exceptions in its pledges of confidentiality—overseen by OMB—under these laws, which were enacted for important purposes but are not compatible with CIPSEA. To the extent that NCES cannot fully promise survey respondents adherence to the confidentiality requirements set forth for a statistical agency, its foundation for garnering public trust may be endangered.

NCES also faces name-recognition challenges resulting from a marketing campaign to raise the IES profile. Under current practice, NCES does not have its own logo, and its name is secondary to IES on its webpage and in other products. In addition, NCES not only lacks its own advisory body (that it had under 1988 and earlier legislation), it does not even have advice from the National Board for Education Sciences, authorized in ESRA to “consider and approve priorities proposed by the (IES) Director,” because, as of summer 2023, that body has held no meetings since 2016 and currently had no members. Finally, unlike the Census Bureau, NCES staff experts do not have authority to communicate directly with Congress—all such communications are required to go through the Department of Education Office of Budget Service or the Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs (OLCA). So, for example, when Congress does request information from NCES or requires NCES input, NCES provides a response through budget or OLCA but does not review or see what is transmitted to Congress. And, importantly, NCES cannot directly communicate with Congress to hear their data needs, so a critical input to NCES’ data agenda development is lost.

2 Attributes of Effective and Trustworthy Federal Statistical Agencies

This section discusses Statistical Policy Directive No. 1, briefly described in section 1 above, in greater depth—in particular, its prescriptions for a statistical agency to be effective and trustworthy. This OMB standard underlies all the recommendations in our report. We also provide excerpts from documents that demonstrate consistency in perceptions of the link between trust in federal statistical agencies and professional autonomy to perform their statistical functions.

2.1 Effectiveness

Statistical Policy Directive No. 1 (Office of Management and Budget Citation2014) addresses responsibilities and practices for federal statistical agencies so they can be effective in carrying out their mission to

disseminate relevant and timely information that “inform(s) decision-makers in governments, businesses, institutions, and households”:

Federal statistical agencies and recognized statistical units must be knowledgeable about the issues and requirements of programs and policies relating to their subject domains. This requires communication and coordination among agencies and …In addition, Federal statistical agencies and recognized statistical units must seek input regularly from the broadest range of private- and public-sector data users, including analysts and policy makers within Federal, State, local, tribal, and territorial government agencies; academic researchers; private sector businesses and constituent groups; and non-profit organizations.

2.2 Trust

Statistical Policy Directive No. 1 describes responsibilities of federal statistical agencies to conduct objective statistical activities that are intended to earn public trust and influence public perceptions of trust. Collecting data that the public perceives as impartial, clear and complete is essential. The Directive further states that to maintain credibility with data providers, data users, and the public, federal statistical agencies “must seek to avoid even the appearance that agency design, collection, processing, editing, compilation, storage, analysis, release, and dissemination processes may be manipulated”.

To further public trust and respect, professional practices undertaken by federal statistical agencies include (a) maximizing objectivity of information released “by making information available on an equitable, policy neutral, transparent, timely, and punctual basis”; (b) ensuring the credibility of federal statistics by assuring “that the selection of candidates for statistical positions is based primarily on their scientific and technical knowledge, credentials, experience, and integrity”; and (c) “maintaining and developing… in-house staff trained in statistical methodology” required “to properly plan, design, and implement core data collection operations and to accurately analyze their data.”

The directive also identifies essential conditions associated with professional autonomy for statistical responsibilities. Specifically, statistical agencies “must function in an environment that is clearly separate and autonomous from the other administrative, regulatory, law enforcement, or policy-making activities within their respective Departments.” This includes conducting “statistical activities autonomously when determining what information to collect and process, the physical security and information systems security employed to protect confidential data, which methods to apply in their estimation procedures and data analysis, when and how to store and disseminate their statistical products, and which staff to select to join their agencies”.

In addition to these excerpts from official government standards governing the federal statistical system, the effectiveness and trust themes are reinforced in a frequently cited resource from the Committee on National Statistics of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Box 1 presents highlights from two of the overarching principles stated in Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency.

Box 1. Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency (National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021)

Independence from political and other undue external influence. Federal statistical agencies must be independent from political and other undue external influence in developing, producing, and disseminating statistics.

“A statistical agency must be impartial and execute its mission without being subject to pressures to advance any political or personal agenda. It must avoid even the appearance that its collection, analysis, or reporting processes might be manipulated for political or other purposes. Only in this way can a statistical agency serve as a trustworthy source of objective, relevant, accurate, and timely information.”

Trust among the public and data providers. Federal statistical agencies must have the trust of those whose information they obtain.

“Nearly every day of the year, individuals, household members, businesses, state and local governments, and other organizations provide information about themselves when requested by federal statistical agencies. Without the cooperation of these data providers, federal statistical agencies could produce very little useful statistical information …. (M)ost of the data come from the voluntary cooperation of respondents. …Individuals and entities providing data directly or indirectly to federal statistical agencies must trust that the agencies will appropriately handle and protect their information.”

A recent article authored by several former statistical agency heads, ASA Science Policy staff, and other statistical leaders (Citro et al. Citation2023) identifies six measures of professional autonomy in federal statistical agencies:

Control over data collection and analysis

Control over data management and protection systems

Control over statistical data release and data products

Control over staffing (hiring authority and staffing levels)

Control over budget

Control over contracting, cooperative agreements, and grants

The authors used these six measures to evaluate the 13 federal statistical agencies. With regard to NCES, they concluded that NCES had no statutory protections for any of the six indicators of autonomy. Rather, NCES must rely on the IES and the Department of Education to respect its professional autonomy. The 2022 National Academies’ report A Vision and Roadmap for Education Statistics indicates they have not done so. Our second set of recommendations below, in Section 3, specifies how the six measures of autonomy in the paper by Citro et al. should be implemented for NCES specifically. Members of the Senate Appropriations Committee have also weighed in on the issue; the “chairman’s mark” report for fiscal 2023 appropriations asserted that “The Committee believes the Secretary, Commissioner, and Director of IES should take swift action to support NCES as an independent Federal statistical agency”. (Appropriations Subcommittee (majority) of the U.S. Senate 2022).

3 Recommendations

Based on the current status of the National Center for Education Statistics summarized in Sections 1 and 2, we conclude that:

NCES needs to keep abreast of changes in data sources and be relevant to user needs;

NCES lacks basic authority to perform fully as a federal statistical agency consistent with OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 1; and

NCES is severely at risk to continue even current activities due to the Department of Education’s failure to acknowledge its unique aspects as a federal statistical agency.

The recommendations for action that follow are organized to address these conclusions.

3.1 NCES Needs to Keep Abreast of Changes in Data Sources and Be Relevant to User Needs

In 2022, the director of IES requested that the National Academies’ Committee on National Statistics undertake a study aimed at setting a vision for NCES to achieve in the next seven years (National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). This study was to consider recent trends and future priorities and to suggest changes in NCES’ portfolio of activities and products, operations, staffing, and its use of contractors.

In its report, “A Vision and Roadmap for Education Statistics (National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022),” the Academies made recommendations in five areas:

NCES should develop a strategic plan, reflecting new types of data, drawing on wide and diverse communities of data users and suppliers.

The Center should provide leadership within the Department of Education so that evaluations can be well informed by statistics.

It should explore new sources of data from public and commercial sources.

It should extend its external engagement, outreach, and dissemination of data, building useful data linkage access, and connecting different users.

It should transform its internal structure and operations, and address overreliance on contractors.

Responding to the report is challenging for NCES. The report’s recommendations, in explicit response to the study’s charge, reflect the changing character of data and the need for federal statistical agencies to adapt; they reflect new demands from data users; and they acknowledge the increased need for collaboration among federal statistical agencies and both users and producers of other data products. All require in-house staffing; these are not activities that can be assigned to a contractor.

Recommendations Box for 3.1: NCES needs to keep abreast of changes in data sources and be relevant to user needs

In response to the Academies’ report:

We strongly recommend that NCES take positive steps to implement all the recommendations, although recognizing it will take dedicated staff resources to accomplish them and the recommendations will change the way that NCES has managed in recent years.

We particularly highlight the following recommendations from the Academies’ report that would restore NCES’ authority to function fully in its federal statistical role.

Regarding relevance of NCES’ statistical agenda and keeping abreast of new data sources:

Recommendation 2.1—NCES should develop and implement a bold strategic plan that incentivizes innovation and creative partnerships and that will produce relevant, timely and reliable statistical products to assist education decision makers at every level of government.

Recommendation 2.32—The Secretary of Education, Director of the Institute of Education Sciences, and NCES Commissioner should immediately take actions to enable the NCES Commissioner to most effectively fulfill the responsibilities of the statistical official delineated in the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 and to support evidence-building needs across the Department of Education.

Recommendation 2-2: The Secretary of Education, Director of the Institute of Education Sciences, and NCES Commissioner should collaborate to ensure that NCES is independent in developing, producing, and disseminating statistics.

Recommendation 2-5: To improve its efficiency, timeliness, and relevance, NCES should continually explore alternative data sources for potential use in data and statistical products, conduct studies on the quality of these sources and their fitness for use, and expand responsible access to data from multiple sources and linkage tools.

Regarding the building of public trust in NCES’ work, we endorse the following recommendations from the Academies report:

Recommendation 4-2: NCES should actively collaborate with other data-holding federal agencies and organizations to develop useful products and processes, including those that utilize data from alternative sources, to provide timely, policy-relevant insights.

Recommendation 4-1: NCES should deepen and broaden its engagement with current and potential data users, to gather continuing feedback about their needs and ways that NCES can meet those needs more effectively.

The authors of this article also support the other recommendations of the 2022 National Academies’ report on NCES (see Box above). At the same time, our view is that the remit of that panel did not extend to exploring legislative changes and attendant administrative actions that would contribute to building the trust of respondents who provide data to NCES and users who depend on the agency’s products. To that end, we offer recommendations intended to complement those in the National Academies’ report and focus on public trust and NCES’ capacity to earn that trust.

3.2 NCES Lacks Basic Authority to Perform Consistent with OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 1 for Federal Statistical Agencies

The Hawkins-Stafford provisions for NCES, as discussed previously, were purposeful actions by Congress as a response to a 1986 critical evaluation report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. However, the Education Sciences Reform Act (ESRA) of 2002 made critical changes in NCES statutory responsibilities that severely limit its ability to be a fully performing federal statistical agency as prescribed in Statistical Policy Directive No. 1. That Act removed NCES authority and professional accountability for review and release of its statistical reports; it substituted an added IES level of review that slowed availability of the data for the public and fostered questions as to the credibility of the data. It removed authority for an advisory “council” that could aid NCES in setting its agenda and ensuring that its work is of high quality. It reduced the status of the agency by placing it indistinguishably into a subordinate position within IES along with centers for research, evaluation, and regional laboratories. While it extended the Commissioner’s term from four years to six, that did not offset the significant restrictions otherwise made in ESRA. In 2011, congressional action removed Senate confirmation from the Commissioner’s appointment, leaving it simply as a Presidential appointment.

In summary, many provisions of Hawkins-Stafford were removed by the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002, and assigned, instead, to the Institute for Education Sciences. These changes are, in fact, crucial aspects of the current situation in which America’s education statistics agency is at risk and unable to fulfill the provisions of Statistical Policy Directive No. 1.

Recommendations Box for 3.2: NCES lacks basic authority to perform fully as a federal statistical agency consistent with OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 1 and the Evidence Act.

To address these conditions, we recommend:

That NCES’ authority and professional autonomy be strengthened to fulfill its statistical responsibilities:

Congress should authorize NCES control over design and conduct of data collection, analysis, review and dissemination of its statistical reports.

It should prohibit external review of NCES data acquisition and data release in a manner similar to a repealed Hawkins-Stafford provision that read:” No collection of information or data acquisition activity undertaken by the Center shall be subject to any review, coordination or approval procedure except as required by the Director of the Office of Management and Budget…” For NCES, this would supersede current provisions of ESRA establishing those functions at the IES level for all of its centers.

It should authorize direct NCES oversight for its IT functions, since these are an integral part of managing data collection and analysis.

It should ensure NCES authority over decisions on contracts and grants, and for oversight of work performed under those arrangements for statistical functions.

It should make explicit provisions in ESRA for NCES to be responsible (i) to formulate its budget needs and justify them before IES, the department and OMB; (ii) following decisions on the President’s budget, to participate directly in defending the budget before Congress; and (iii) following appropriation action, to have control, without intervention from IES or other officials, over decisions to manage its available funds, allocating them among NCES’ continuing and new responsibilities.

Following congressional action on items a and b, the Department of Education should implement these provisions in the form of internal operating procedures, as illustrated by the procedural guidelines on “Economic and Demographic Statistical Produce Releases” from the Commerce Department (https://www.osec.doc.gov/opog/dmp/daos/dao216_19.html). The department should frame and support specific responsibilities for NCES in the budget process, item e, as well as for IT and contracts and grants, items c and d.

There are two additional authorities of NCES that have been changed by law since Hawkins-Stafford. While these are not ones that impede NCES’ ability to follow Statistical Policy Directive No. 1, they are ones associated with building public trust. These relate to appointment of the Commissioner and to authority to establish an advisory group charged with maintaining statistical standards and with oversight of the Center’s statistical agenda.

First, the leader of the National Center for Education Statistics has had numerous titles and been appointed through a variety of procedures over the years. As part of the Hawkins-Stafford Amendments in 1988, the post was made a Presidential Appointment with Senate Confirmation. It was authorized at Executive Level IV, the customary assistant secretary level in government departments, and equivalent to the then assistant secretary overseeing research and statistics functions in the Department of Education. After establishment of IES as a more elevated home for department research-related activities in 2002, all heads of “centers” within IES were appointed at the Executive IV level, while the Director of the Institute for Education Sciences was set at the Executive II Level. In later legislation, Congress eliminated Senate confirmation for the NCES Commissioner as part of an effort to reduce confirmation workload for the United States Senate, retaining Presidential appointment; this is where it has remained.

The authors of this article believe that Presidential appointment without Senate confirmation is not a desirable option for this position. It does not contribute to trust in NCES, and in fact can engender suspicion about potential political influence over NCES. While some argue that appointment by the President would indicate stature and credibility for NCES, others see potential for partisan influence in the appointment: there is neither the check and balance that Senate approval conveys, nor the systematic review procedures associated with a career appointment.

Second, NCES had its own statutory advisory committee for many years prior to Hawkins-Stafford and that was both continued and modified by the 1988 legislation. That committee (later called a council) played a significant role in creating a favorable climate for public trust in NCES as it took steps to rebuild after the severely critical 1986 evaluation by the National Academies. The council had a broad, dual function for oversight of NCES quality and agency policy. ESRA replaced the NCES council with an IES-focused one, which, in turn, never paid much attention to NCES. Nor did it ever serve the trust-building purpose that the Hawkins-Stafford Council had demonstrated. A newly formed NCES advisory body would help the agency set data agenda priorities, keep abreast of methodological advances, and meet data users’ ever-changing needs while adhering to professional standards. These functions would be separate from scientific or technical advisory committees frequently established as a part of NCES data collection programs.

Recommendations Box for 3.2, continued

We further recommend:

That the form of appointment of the NCES Commissioner of NCES should either be a Presidential appointment with Senate confirmation restored, as ASA has consistently recommended for several years, or should be made a career appointment.

That Congress authorize a high-level advisory body in a manner determined by the Commissioner, with a charge to review the statistical activities of the Center to ensure maintenance of strong technical quality and of a relevant agenda to inform the public. The 2022 National Academies’ report on NCES contains a similar recommendation and describes a form for such a committee that the authors of this report endorse:

Recommendation 4.3—NCES should explore and establish creative models for a nimble, ongoing consulting body, supplemented by a pool of ad hoc consultants, to help NCES innovate and be accountable for progress on strategic goals.

To keep the consulting body nimble and flexible, the panel recommends that the body not be subject to Federal Advisory Committee Act (Citation1972) regulations. The body might contain a set of regular members with knowledge of the full scope of NCES’ activities, to provide strategic advice and accountability, along with additional and varying participants (see, e.g., National Institute of Statistical Sciences Technical Expert Panel Citation2018) depending on the particular expertise necessary at a given time. The consulting body would have moral but not statutory authority with regard to NCES, and might also at times provide backing when NCES faces difficult decisions.

3.3 NCES is Severely at Risk to Continue Even Current Activities Due to Department Failure to Acknowledge Its Unique Aspects as a Federal Statistical Agency

Like many of its sister federal statistical agencies, NCES is an anomaly in the Department of Education. The principal functions of that department are the award of grants and financial aid, at the elementary, secondary, and higher education levels, and the conduct of regulatory oversight of civil rights legislation. Indeed, even the immediate NCES home, the Institute of Education Sciences, was created to award grants for research, evaluation, regional laboratories, and related purposes, but not to conduct in-house research.

By contrast, NCES has a direct federal function—the gathering and reporting of statistics to inform the nation about the condition and progress of education. Responsibility for developing and administering statistical activities and analyzing and disseminating data requires a government agency to make decisions—this function cannot be delegated. An operational function is fundamentally different in character from a grant award or regulatory function. The appropriate recognition of NCES’ responsibilities and its direct accountability to the public has not just been intentionally neglected by the department, but fostered by it in the interests of treating its various components “equally.” This long-standing practice needs to change.

The most glaringly egregious manifestation of failure to recognize NCES’ direct responsibility to inform the American public, and its direct accountability for what it does, is in the staffing constraints imposed on the Center. Just a few illustrations of NCES’ activities underscore the point: determination of specifications for a statistical study to meet government needs; making decisions about the type of analyses appropriate for data releases and subsequent publications; oversight of contractors to ensure that government statistical design specifications are followed and that there is value for the cost to the government; and developing ways to work collaboratively with states. These are inherently governmental functions. All imply in-house staff.

The NCES website lists some 56 studies and ongoing tasks, including 26 elementary and secondary collections, 13 higher education collections, and 2 domestic and 8 international assessments of student and adult learning (NCES, Citation2023). This is a demanding workload to support, and current NCES staffing levels impede the agency’s ability to carry out these responsibilities. The National Academies’ 2022 report provided additional information about the NCES employment situation:

Even as NCES’ staffing declined, the scope of the Center’s work increased substantially. For example, the Common Education Data Standards and the Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS) Grant Program did not exist in 2003. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System have undergone substantial expansion since 2003, and EDFacts was a large addition to NCES’ work in 2013. “(p. 21) In fiscal year 2010, NCES had 124 full time equivalent staff on board. By fiscal 2021, that had declined to 90, a decline of 27%. (p. 191). “NCES’ annual turnover rate since FY 2018 has ranged from 9 to 11 percent… and is an indicator of the risk for further staff (and knowledge) loss.” (p. 21)

As noted in Section 1.2, NCES’ budget to staff ratio is eight times the median of all federal statistical agencies (with only 95 NCES employees in the comparison year compared with 875 contractor employees). The effects of this in-house staffing shortage are myriad. During COVID-19, NCES’ performance in gathering critical data needed by education policy officials and others about practices and conditions in education during the pandemic was far below the standard one should expect from a principal federal statistical agency. The NCES-provided information was tardy and its coverage thin; the analyses were missing or inadequate. This is not just “a problem.” We view this as an alarming indicator that the staff resources of NCES are stretched beyond reason. This view is further buttressed by a finding in the 2022 National Academies’ report about loss of specific studies:

… at least 12 NCES programs have been discontinued and/or put on hiatus, citing lack of staff (e.g., there are no staff to oversee the contractors). These facts suggest that, if NCES is to successfully fulfill its promise and vision, additional support is needed to curb a deteriorating staffing situation. (p. 117)

When we review the recommendations of the 2022 National Academies’ report—important recommendations to keep NCES up to date technologically and relevant to data users—it is clear that all require additional staff activity: undertaking an ambitious strategic plan, closer work with contractors, reaching out to data providers, connecting different data suppliers, managing an advisory group, and more. The additional recommendations made in this report also carry staffing implications for things that NCES does, such as reviewing reports, making budget choices, and managing confidentiality protections. Our conclusion is that this long-standing problem must be addressed.

Recommendations Box for 3.3: NCES is severely at risk to continue even current activities due to the Department of Education’s failure to acknowledge its unique aspects as a federal statistical agency.

We recommend:

1. That Congress take these actions on use of NCES appropriations:

specify that statistics and assessment appropriations can be used for necessary salaries and expenses, including staffing levels, for those functions, and

transfer the portion of IES program administration funding and staff allocations currently used for statistics and assessment to each of the respective NCES accounts.

This combination of legislative changes would make NCES budgeting more similar to the norm for other statistical agencies (such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis). It would also be similar to the department’s budgeting practice for the Office for Civil Rights and the National Assessment Governing Board, as well as for the administrative costs of IES.

2. That the Department of Education follow the suggestion of the 2022 National Academies’ report that more flexible ways of using contractors be devised.

“In the short term, NCES’ contracting model may provide valuable opportunities because contracts are useful for getting new things done quickly. If used appropriately, contractors could make NCES much nimbler. For example, capitalizing on opportunities provided by 21st-century advances in data collection, both within and outside the federal government (e.g., web scraping, natural language processing, social media, data linking), will require skilled personnel who are dedicated to these functions. “NCES has a profound shortage of data scientists and other staff; therefore, without the use of contractors, NCES may not realistically be able to rapidly increase its capabilities or capacity in areas that require sampling statisticians, assessment development experts, survey methodologists and statisticians, and data analysts and scientists.” (pp. 117, 118)

NCES should consider ways to leverage contractors and other external partners to build and maintain institutional knowledge and in-house innovation. NCES should also partner with contractors to create and revise templates for all steps of the data pipeline—from data-use agreements to presentation graphics style—to embed innovations across the Center and its contractors.” (p. 118)

Less egregious, perhaps, but equally prejudicial to NCES’ capabilities, are those department operating procedures that prevent routine conversations between NCES staff experts and Members of Congress, congressional staff, and departmental officials. These members, staff, and department officials should have the option to speak directly with the NCES experts about statistical findings and analyses, in addition to their usual practice of receiving such information from their own staff. While not of the same magnitude, one last example of the department’s persistent failure to recognize the unique and direct responsibilities of its statistical agency is the IES practice disallowing an identifiable NCES logo.

We believe that Congress should authorize conversations with NCES experts among Members of Congress and their staffs to address education statistics topics for which NCES has relevant data. Typically, all communications with Congress are transmitted through the department’s Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs, or on appropriation matters, through budget officers. The direct conversations we envision should be focused and recurring, at least for the annual Condition of Education report, and for topical studies requested by Congress, and also should be scheduled as appropriate for other education topics about which NCES gathers relevant statistics. The department should enable the congressional data discussions through written internal operating procedures, so that everyone can be informed about expectations for data discussions with NCES. Department leaders should routinely participate in briefings by NCES on key data products and findings. In addition, they should seek out NCES experts to inform themselves directly about statistical data relevant to issues under consideration, supplementing what they learn routinely from briefings by their own staff.

Such data discussions would facilitate exchanges between Congress and NCES, and between department leadership and NCES, serving at least two purposes:

One is that these exchanges would directly inform Members of Congress and their staffs, as well as the leadership of the department, avoiding filters from intervening layers that could lead to questions about possible political influence on the data and their relevance. In turn, they would provide a continuing means by which NCES staff can keep informed about requirements and questions that Congress and the department have, helping to ensure that planning of future statistics is kept abreast of government needs.

Another is that these exchanges would create situations in which the congressional or department members being briefed are encouraged to ask for clarifications and elaboration so they can understand the interpretations and limitations of the data. A particularly critical audience would be the department’s Chief Evaluation Officer.

On the issue of an identifiable logo, the reason to recommend one is to make public the source and sponsorship of products from NCES. That simple identification would help build trust with outside users that there has not been political or other undue external influences over NCES products and would also hold NCES accountable for the contents of those products. Currently, Department of Education practice obscures NCES’ name, making it secondary to that of its umbrella organization, IES. This is unlike the practice in most other statistical agencies. Because trust in a statistical agency’s products is paramount, it is critical that the agency name be known and associated with its products. Such trust is necessary for potential survey respondents, who are more receptive to responding to questions from a recognized statistical entity. Ultimately, policy makers and the public need to recognize easily that the data they are receiving comes from a federal statistical agency that adheres to professional standards.

Recommendations Box for 3.3, continued

We further recommend that:

Congress authorize conversations with NCES experts among members of Congress and their staff to address education statistics topics for which NCES has relevant data. The conversations should be focused and recurring, at least for the annual Condition of Education Report, and for topical studies requested by Congress and also should be scheduled as appropriate for other education topics about which NCES gathers relevant statistics.

The department enable the congressional data discussions through written internal operating procedures, so that everyone can be informed about expectations for data discussions with NCES.

Department leaders routinely participate in briefings by NCES on key data products and findings and seek out NCES experts to be better informed about issues under consideration.

The department ensure that NCES products and its website are clearly identified with its name and logo.

4 Conclusion

As a concluding note, we call attention to the trend since the passage of ESRA to have NCES be led and administered like the other three IES centers, all of which have the very different mission of funding research. Unless this trend is reversed, NCES’s autonomy, accountability, and stature will continue to diminish and its ability to produce timely, objective, and relevant statistics will continue to be undermined. NCES will not be able to fulfill its role and responsibilities as a principal federal statistical agency under the Evidence Act, Statistical Policy Directive No. 1, and the forthcoming regulation on Fundamental Responsibilities of Recognized Statistical Agencies and Units, nor will it be able to implement the National Academies’ recommendations to the fullest.

Acknowledgments

Auerbach, Citro, and Pierson gratefully acknowledge the support of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AugustusHawkins-Robert, T. (1988), “Stafford Elementary and Secondary School Improvement Amendments of 1988 Pub. L. 100-297,” available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/5

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2023), “Table 1.1.9. Implicit Price Deflators for Gross Domestic Product,” available at https://www.bea.gov/itable/national-gdp-and-personal-income (Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Citro, C. F., Auerbach, J., Evans, K. S., Groshen, E. L., Steven Landefeld, J., Mulrow, J., Petska, T., Pierson, S., Potok, N., Rothwell, C. J., Thompson, J., Woodworth, J. L., and Wu, E. (2023), “What Protects the Autonomy of the Federal Statistical Agencies? An Assessment of the Procedures in Place to Protect the Independence and Objectivity of Official U.S. Statistics,” Statistics and Public Policy, 10. DOI: 10.1080/2330443X.2023.2188062.

- Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (CIPSEA), Pub. L. 107-347. (2002), https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-bill/5215.

- Department of Education. (2023), “Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Request,” available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget24/justifications/y-ies.pdf.

- Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 (as amended), Pub. L. 107–279. (2002), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-747/pdf/COMPS-747.pdf.

- Elchert, D., and Pierson, S. (2020), “National Center for Education Statistics Faces Program Cuts,” Amstat News. American Statistical Association. Available at https://magazine.amstat.org/blog/2020/06/01/nces-faces-program-cuts/ [March 2022].

- Elliott, E. (2015), “For Trust in Education Statistics,” The Hill. Available at https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/education/232223-for-trust-in-education-statistics/. See also, https://community.amstat.org/sciencepolicy/blogs/steve-pierson/2015/01/29/former-federal-statistical-agency-heads-urge-stronger-nces-as-senate-panel-advances-bill-to-weaken-it.

- Federal Advisory Committee Act, Pub. L. 92–463. (1972), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title5/title5a/node2{/&}edition=prelim

- Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, Pub. L. 115-435. (2019), https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ435/PLAW-115publ435.pdf

- FY2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act. (2022), “Division H-Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2023,” available at https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Division{/%}20H{/%}20-{/%}20LHHS{/%}20Statement{/%}20FY23.pdf.

- High School and Beyond. A NCES longitudinal survey, available at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/hsb/.

- Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies, U.S. Senate (2022), Explanatory Statement for Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2023. Available at https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/LHHSFY23REPT.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021), Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency: Seventh Edition, eds. C. F. Citro and B. A. Harris-Kojetin, Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022), A Vision and Roadmap for Education Statistics, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. DOI: 10.17226/26392.

- National Assessment of Educational Progress, NCES, available at https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/.

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2023), https://nces.ed.gov/(accessed April)

- National Education Statistics Act of 1994, Pub. L. 103–382. (1994), https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/6/text/statute.

- National Institute of Statistical Sciences Technical Expert Panel. (2018), “Integrity, Independence, and Innovation: The Future of NCES,” available at https://www.niss.org/sites/default/files/NISS_report_R4_single4_page.pdf.

- National Research Council. (1986), Creating a Center for Education Statistics: A Time for Action, Washington, DC The National Academies Press. DOI: 10.17226/19230.

- Office of Management and Budget (Multiple years), Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government.

- Office of Management and Budget (Multiple years), Statistical Programs of the United States Government, multiple years.

- Office of Management and Budget. (2014), “Statistical Policy Directive No. 1: Fundamental Responsibilities of Federal Statistical Agencies and Recognized Statistical Units,”

- Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011, Pub. L. 112-166. (2012), https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/679/text

- Strengthening Education through Research Act. (2014), “H.R. 4366, 113th Congress,”available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4366/text.

- Strengthening Education through Research Act. (2015), “S. 227, 114th Congress,” available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/227/text/is.

- Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001,” (2002), “commonly called the USA Patriot Act, Pub. L. 107-56,” available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-bill/3162.

- Vinovskis, M. A. (1998), “Overseeing the Nation’s REPORT CARD The Creation and Evolution of the National Assessment Governing Board (NAGB),” available at https://www.nagb.gov/content/dam/nagb/en/documents/publications/95222.pdf.

- Woodworth, J. (2021), Presentation of NCES Commissioner Lynn Woodworth to quarterly meeting of Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics.

Appendix A:

Principal Agencies in the Federal Statistical System*

Bureau of the Census

Bureau of Economic Analysis

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Transportation Statistics

Economic Research Service, USDA

Energy Information Administration

National Agricultural Statistics Service

National Center for Education Statistics

National Center for Health Statistics

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics

Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, SSA

Statistics of Income Division

*Table 9-1, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2024.

Appendix B:

The Strengthening and Weakening of NCES

Sections

B1: Hawkins-Stafford Act

B2: National Education Statistics Act of 1994

B3: USA Patriot Act

B4: Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 (ESRA)

B5: Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011

B6: Strengthening Education through Research Act (SETRA)

B7: FY21 Administration Statutory Change Requests

The last 35 years have been dynamic for NCES’ autonomy and stature. Five laws have iteratively altered autonomy and stature provisions, along with at least two more bills introduced in separate congresses and FY21 administration proposals proposing to alter autonomy and stature provisions. One might expect legislative changes that adjust NCES autonomy and stature provisions in an oscillating fashion between more and fewer protections and between higher and lower stature as they are tuned toward the desires of a particular Congress or administration. For NCES, however, the trajectory is a steep initial rise followed by subsequent notching down of its authority and autonomy across several decades.

The five laws affecting NCES autonomy and stature since the late 1980s are the Hawkins-Stafford Act of 1988 (Hawkins-Stafford), National Education Statistics Act of 1994 (NESA), USA Patriot Act, Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002, and Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 (PAESA), which we cover in chronological order. We also include in this appendix the unsuccessful attempts—starting in 2014—to reauthorize IES in multiple congresses through the Strengthening Education through Research Act (SETRA) and two proposals by the administration in its fiscal year 2021 (FY21) budget request.

B.1 Hawkins-Stafford Act

The August F. Hawkins-Robert T. Stafford Elementary and Secondary School Improvement Amendments of 1988 (Hawkins-Stafford) dramatically elevated NCES’ stature and its protections to ensure objective and reliable education statistics. The motivation for these provisions was profound concern for the quality, relevance, and impartiality of NCES’ products to inform the country’s interest in education reform.

It codified essential protections for NCES, as listed in . Among other provisions, Title III of Hawkins-Stafford ensured the NCES commissioner would be “appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate” to serve a four-year term (item #1 in ). The same title empowered the commissioner to appoint ad hoc advisory committees (#2), enter contracts (#3a), prepare and publish relevant information and documents (#3), establish inter-agency agreements (#3b), and “select, appoint, and employ” personnel to carry out agency functions (#3d). Hawkins-Stafford also included many provisions to ensure NCES data quality (#5 & 6), facilitate data provider cooperatives (#7–9), protect the confidentiality of individual data (#10), and establish a data agenda (#11–15).

Table B.1 Public Laws Authorizing NCES, 1988 and 2002.

The Hawkins-Stafford protections for NCES were motivated by the 1986 National Academies’ report, Creating a Center for Education Statistics: A Time for Action, which bluntly addressed NCES’ substantial and long-standing problems:

We wish to emphasize the seriousness with which we view the center’s problems. We believe that there can be no defense for allowing the center to continue as it has for all too long. If, indeed, “the nation is at risk” in the area of education, it is past time for those in positions of responsibility to acknowledge the risks and dangers of perpetuating the myriad and continuing problems of the center (p. 4).

The report expounded on the extent of NCES’ long-standing problems, including issues relating to the quality of its data collections, its antiquated approach to analyzing data, and a lack of timeliness in reporting. The panelists concluded that: “…for the most part, the center lacks written standards to guide many, if not all, of its technical activities, including those concerned with collecting data, monitoring contracts, and publishing reports” (p. 15).

To remediate these problems, the NAS panel provided multiple recommendations with the ultimate goal of ensuring that NCES’ principal responsibility should be “the integrity of the numbers, not responsiveness to political needs” (p. 13). In turn, they recommended that the Congress “demonstrate its support for the center and its mission through its budget actions…” (p. 55). Relating to the agency’s mission, the panel wrote, the mission of the Center for Statistics, as stated in statute should “be strengthened to clearly establish and define the role of the center in assisting the Secretary of Education in determining the data needs for assessing the condition of education in the United States, and for accepting responsibility and accountability for ensuring the availability of the necessary data” (p.55).

The panel continued by emphasizing the need for NCES to be “nonpartisan” and to serve as the Department’s “functional agency responsible for coordination and technical review of all data collection” (p. 55). Panelists wrote that the secretary should designate NCES as “the focal point of releasing statistical information on education.” In another recommendation, the distinguished group indicated that the center’s existing Advisory Council on Education Statistics should be modified to focus on providing technical oversight. As a joint action, the agency was to create an “Office of Statistical Standards and Methods,” chaired by a chief statistician, to “establish and maintain statistical standards throughout the center” (p. 58).

As stated by the panelists, there was “ample” existing precedent to bolster NCES’ strength:

…the actions we propose, to a large extent, are inherent elements in the operating philosophies that guide such respected statistical organizations as the Bureau of the Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Center for Health Statistics, and the Energy Information Administration. In essence, we seek to institute changes at the Center for Statistics for which there is ample precedent (p. 3).

The influence of the NAS report on the ESEA provision for NCES is plainly evident in the opening line of the NCES section of the report language for the House Committee on Education and Labor, where NCES autonomy and stature provisions originated. It reads, “the bill strengthens the [NCES] … in accordance with” the NAS report (p. 96). The report seems to justify the autonomy and stature provisions with the following language:

The Committee notes that it is necessary to monitor the education industry and its contribution to our economy by supporting a strong National Center for Education Statistics. In 1987, education was the second-largest industry in the Nation. It is supported overwhelmingly by public tax dollars thus making it crucial that adequate data be available to determine its efficiency and progress in providing educational services to the American people.

The public needs the assurance that the Center’s reports are nonpartisan, unbiased and consistent with the quality evident in the demographic, health, and labor statistics reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Bureau of the Census and the National Center for Health Statistics” (p. 96).

…Fundamental to the trust the public has in the truthfulness of an agency’s statistics is the belief that the data are not biased toward any particular ideology. (p. 98)

The House NCES professional autonomy and stature provisions were vigorously opposed by some members of the Reagan administration (Vinovskis Citation1998). In a letter to Representative Augustus F. Hawkins (D-CA), then Chairman of the House of Representatives Education and Labor Committee, Secretary of Education William Bennett decried such NCES provisions:

More deeply objectionable are the establishment of a Presidentially-appointed Commissioner of Education Statistics and a separate authorization for the Center for Education Statistics. In large measure, the Secretary reorganized the Office of Educational Research and Improvement (OERI) in 1985 to resolve conflicting lines of authority (posed principally by the Presidentially-appointed Director of the National Institute of Education and the policy-making National Council on Educational Research). In enacting Pub. L. 99–498 Congress, in effect, ratified the rationalized and streamlined management structure of the current OERI; the amendment, on the other hand, would reintroduce the type of bifurcated authority that led to the reorganization in the first place (history of NAEP, p. 77; Letter of Secretary William Bennett to Representative Augustus F. Hawkins, April 20, 1987, p. 13).

B.2 National Education Statistics Act of 1994

Six years after Hawkins-Stafford, Congress undertook reauthorization of ESEA. The National Education Statistics Act of 1994 (NESA) affirmed the Hawkins-Stafford autonomy and stature provisions for NCES—including Presidential Appointment and Senate Confirmation (PASC) for the commissioner, publishing and contracting authority, confidentiality protections—and further strengthened them by extending the commissioner’s publishing scope to align with recognized statistical practices.

B.3 USA Patriot Act

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, the United States Congress dramatically altered its approach to protecting citizens’ privacy and confidentiality. This is perhaps best exemplified by the “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001,” commonly called the USA Patriot Act (Public Law 107-56). Quickly signed into law by President George W. Bush on October 26th, the Patriot Act weakened NCES’ existing data privacy and confidentiality protections by facilitating a means for a designated federal officer to use NCES data for non-statistical purposes in instances involving domestic or international terrorism. The action undermined the confidentiality protections of Hawkins-Stafford, NESA, and the Privacy Act of 1974, which makes illegal the release of citizens’ personally identifiable information without prior consent in agencies across the federal government.

B.4 Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 (ESRA)

The next major legislation affecting NCES’ autonomy and stature was the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 (ESRA), Title I of Public Law 107-27(H.R. 3801). By organizing IES’ four centers to be parallel, ESRA made NCES susceptible to additional diminution as evidenced by several attempts to further undermine its stature and autonomy in the years since. ESRA repealed NESA and replaced NCES’ parent organization, the Office of Educational Research and Improvement (OERI), with the Institute of Education Sciences (IES). ESRA chipped away at many NCES autonomy provisions enacted in Hawkins-Stafford, as documented in , and also maintained the awkward power dynamic of keeping the presidentially-appointed and Senate-confirmed NCES commissioner, under another PASC administrative layer, that is, the IES director. Such PASC layering has long drawn questions about, if not opposition to, the NCES commissioner being PASC.

Briefly, ESRA transferred NCES to IES and replaced the OERI entities—including five National Research Institutes, the ten university-based national education Research and Development Centers, and the Office of Reform Assistance and Dissemination along with its various programs—with three IES centers: the National Center for Education Research, the National Center for Education Evaluation, and the National Center for Knowledge Utilization in Education. Like the Assistant Secretary of OERI, an executive level IV position, ESRA mandated that the IES director also be presidentially-appointed and Senate confirmed albeit at an executive level II.

In attempting to equalize the four centers under IES, ESRA weakened NCES autonomy with the following provisions:

The IES “Director shall: (a) administer, oversee, and coordinate the activities carried out under the Institute, including the activities of the National Education Centers; and (b) coordinate and approve budgets and operating plans for each of the National Education Centers for submission to the Secretary.”

“The duties of the Director shall include…To advise the Secretary on research, evaluation, and statistics relevant to the activities of the Department.”

“The Director may prepare and publish (including through oral presentation) such research, statistics (consistent with part C), and evaluation information and reports from any office, board, committee, and center of the Institute, as needed to carry out the priorities and mission of the Institute without the approval of the Secretary or any other office of the Department.”

“The Director shall provide the Secretary and other relevant offices with an advance copy of any information to be published under this section before publication.”

The transfer of these responsibilities away from the NCES Commissioner along with myriad other changes are documented in the last column of . The Table also notes what Hawkins-Stafford provisions were maintained.

Just as concern for the quality of education statistics seemed to strongly motivate the 1988 Hawkins-Stafford NCES provisions, the primary motivating factor for the dismantling of OERI and the creation of IES seemed to be concern for the quality of and apparent ideological influence over education research. The just-enacted education reauthorization bill No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 (NCLB) was likely a key driver for the interest in the quality of education research and its potential use in policymaking. Representative Michael Castle (R-DE), the House champion for ESRA and lead H.R. 3801 sponsor, commented on the May 2002 House passage of the bill:

…H.R. 3801 makes long overdue changes to the Office of Education Research and Improvement. I urge my colleagues to support this bipartisan common sense legislation and send a strong message to the other body that the successful implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act requires a Federal office that can deliver a high quality education research product (p. H1739).

Independence and objectivity seemed fundamental to yielding high-quality research in the minds of those commenting in the Congressional Record. Representative Howard Phillip McKeon (R-CA) stated as much, saying ESRA would replace OERI with “a new, more independent Institute of Education Sciences”, and that the [conferenced House ESRA bill] “H.R. 5598 establishes quality standards that will put an end to trends in education that masquerade as sensible science.” In the same speech he went on to say that ESRA “also makes certain that research priorities focus on solving key problems and are informed by the needs of teachers, parents and school administrators, rather than political pressure.” Similarly, Representative Castle said the [original House ESRA bill] H.R. 3801” ensures that tried and true scientific information, not fads or fiction, form the basis for setting education policy and improving education practice” and that it “attempts to address what I have come to know as serious shortcomings in the fields of education research, including the creeping influence of short-lived partisan or political operatives.” Senator Gregg (R-NH) stated, “Yet the need for sound, rigorous education research that is free of political bias and useful to educators has never been more important.”

Turning specifically to the ESRA’s NCES autonomy and stature provisions, the original House-passed ESRA bill, H.R. 3801, implicitly removed PASC for the NCES commissioner, with the following section 117 statement: “each of the National Education Centers shall be headed by a Commissioner appointed by the Director.” During its consideration, the Senate maintained PASC for the NCES Commissioner, highlighting the need for NCES autonomy. Indeed, during Senate consideration of his floor speech in support of [the companion] S. 2969, Senator Kennedy highlighted this component, saying, “Our bill also maintains the autonomy of the National Center on Statistics, and makes sure that the National Assessment of Education Progress stays out of the political arena.” Senator Gregg did the same, highlighting as one of eight points that the bill “increases the independence of the research and evaluation functions of the Department, while preserving the independence and quality of the current National Center for Education Statistics.” Senators Kennedy’s and Gregg’s statements echoed the explicit report language for S. 2969 on this point:

Each of the National Centers will be headed by a commissioner appointed by the Director, except the Commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics. The committee feels strongly that it is important to maintain the current status of the Statistics Commissioner—being presidentially appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate, in order to maintain the independence of statistical collection and analysis (p. 5).

ESRA’s creation of an independent education research institute to support high-quality education research along with the Senate’s strong support for a PASC NCES head to ensure independence of NCES statistics resulted in compromises in power for both positions. The Senate attempted to exempt the NCES commissioner from the IES director’s supervision, as stated in section 117(d):

SUPERVISION AND APPROVAL.—Each Commissioner, except the Commissioner for Education Statistics, shall carry out such Commissioner’s duties under this title under the supervision and subject to the approval of the Director (p. 1953).

In practice, we have seen little effect of this provision’s direction to exclude the NCES commissioner from the Director’s supervision and approval.

B.5 Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011

The next major legislation affecting NCES autonomy and stature was S.679, or the Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 (PAESA). This law removed SC of the NCES commissioner, along with SC of the director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and hundreds of other PASC positions.

The law’s rationale, as articulated in Senate report 112-24, was to cull the rising number of PASC votes. At the beginning of the Obama administration, for example, over 1,200 such positions existed in the federal government, leading to high costs, hearing delays, vacancies for key positions, and inefficiencies in government operations. The bill’s writers provided four criteria for which appointments to target, with the fourth one applying to the NCES and BJS heads: “Directors, Administrators, Commissioners or other positions at or below the Assistant Secretary level that report to a Senate-confirmed Assistant Secretary or other Senate-confirmed position and/or are responsible for a relatively small office.” A layered organizational structure similar to NCES and IES existed at BJS, with its director reporting to an Assistant Attorney General for Justice Programs (AAG), also a PASC.

Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY) introduced PAESA on March 30, 2011, but the NCES stakeholder community did not become aware of its effect on the commissioner until late April of 2011, after it had been reported out of the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee. During a meeting with NCES stakeholders a few weeks later, attended by a coauthor of this manuscript, the chief counsel for then-chair of the Committee on Rules and Administration Charles Schumer confirmed that SC status was removed for NCES and BJS because the agencies were the lowest of three consecutive PASC determined positions.