Abstract

Do legislators get credit for working with the other party? Studies on this have been limited due to a lack of an appropriate counterfactual. This paper experimentally estimates the value of credit claiming on a small project that was produced with bipartisanship or with an uncooperative party. I argue that process does indeed matter. Specifically, I hypothesize voters will punish in-party partisans for working with the other side and punish out-party partisans when they do not work with their side. However, in-party partisans do not care whether their party works with the other side. Out-party partisans punish members for uncooperative legislating. Further, I argue and find that these effects are distinguishable from overall partisan effects, demonstrating that members can use distributional projects to gain out-party support in a polarized environment. These findings have important implications for lawmaking and polarization.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.Polarization in the United States is at an all-time high. Recently, the popular news blames polarization for the United States falling behind other countries in vaccination rates for COVID-19.1 People are less likely to get married to members of the opposite party now than in previous decades, and that increases political polarization (Huber and Malhotra, 2017; Iyengar, Konitzer and Tedin, 2018). Polarization has gotten so bad in America that talking about politics leads workers to view the workplace as “toxic” and turnover from toxic workplaces cost companies $223 billion from 2008 to 2014, according to reporting from Marketwatch.2 So, how do Members of Congress attract voters outside their own party?

Historically, one important method that Members of Congress have relied on to gain the favor of members of the other party is to give their districts appropriations, or pork. The way this works is that a member will provide their district with a benefit and then advertise through campaign material (e.g. press releases, campaign statements, advertisements, and so on) their role in bringing this benefit to the community. Credit claiming works to win over ideologically unsympathetic voters because receiving a benefit is a non-partisan issue (Mayhew, 1974). Voters from both parties can usually agree that fewer potholes are preferable to more potholes. Distributional projects also serve another critical purpose other than legislators’ electoral ends: building winning coalitions to pass important policy projects. Party leaders use distributional politics in order to persuade unsupportive members to vote for significant pieces of legislation (Evans, 2004).

However, given that polarization is so severe, has the effectiveness of this strategy changed? Specifically, given that people have such negative feelings towards out-partisans, can distribution be used to win unsympathetic voters? Do the effects of polarization spread to voters’ response to the legislative process itself? In this paper, I focus on voters’ evaluations of appropriations, focusing on whether voters reward or punish legislative cooperation, or bipartisanship. Specifically, I run a 2x2 factorial experiment where I present experimental subjects with a hypothetical campaign press release and vary member party and cooperative environment (bipartisanship or no cooperation). The key comparison is the interaction of treatment condition and respondent party on the respondent’s evaluations of the hypothetical member.

I argue that when one party works alone in producing appropriations, there is a clear line of credit to the party. Further, in the absence of cooperation, there are fewer compromises that have to be made. I expect in-partisans to prefer appropriations to come from a non-cooperative environment or without bipartisanship. Out-partisans will punish members who don’t include their own party when funding appropriations.

In-partisans are mostly unaffected by the level of cooperation. However, out-partisans punish members for producing appropriations without cooperating with their party. Further, in all conditions, the ratings of the member providing the appropriation will be higher than the ratings of the respondent’s out-party. Thus, credit-claiming is still an effective campaign strategy for legislators and is most effective when bipartisanship produces the policy the member is claiming credit for.

Credit Claiming in a Polarized Era

Focusing on discretionary spending, Levitt and Snyder (1997) find that “an additional effect of $100 per capita in spending is worth as much as 2 percent of the popular vote” (p 30). These effects are so large because spending within the district is broadly popular. This predicts large effects of district spending on a candidate’s ratings among their constituents. However, it is less clear whether these effects are homogeneous. One obvious source of heterogeneity is whether the Member of Congress providing the spending is a member of the same party as the voters. The reason co-partisanship is important, especially in the past decade is because there has been a rise in distrust and negative feelings towards the other party (Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015; Abramowitz and Webster, 2016).3 The declining importance of local issues in elections highlights voters’ disdain towards out-partisans where out-partisan politicians used to win votes (Lapinski et al., 2016; Abramowitz and Webster, 2018; Sievert and McKee, 2018). Research also shows voters are unwilling to support compromise, which has coincided with the rise in negative partisanship (Harbridge, 2015). Overall, research has shown a nationalization of politics which suggests that legislators do not win many voters on local (distributive) issues (Jacobson, 2015; Polborn and Snyder, 2017; Hopkins, 2018; Lee, Landgrave and Bansak, 2022).

Given that voters and candidates are more focused on national policy issues, there are fewer gains to be made from a strategy focused on distributional policy. However, in an analysis of strategies Harden (2015) demonstrates that some state legislators emphasize their distributional accomplishments over any other “dimension” of representation.4 So, there seems to be a disconnect between legislative strategy and research on voters’ responses to cooperative distribution.

There are further considerations on distributional politics; scholars have found that legislators use district spending and then credit claiming, to avoid taking positions on polarized issues that would upset their constituents (Wichowsky, 2012; Grimmer, 2013). The value of spending is especially high for legislators in polarized constituencies, where position-taking over issues would upset many of their constituents. Still, credit claiming over district spending is a very common strategy used by legislators both in and outside an election to win votes. This suggests that legislators at least believe that providing district spending to their voters is a worthwhile endeavor to expand their base of support.

Thus, even in a polarized environment, legislators use multiple strategies of credit-claiming. However, the expectation that voters will reward legislators unconditionally seems less obvious in a polarized era. First, voters have preferences over the legislative agenda. Specifically, as Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison (2014) find in survey experiments voters do not prefer partisan cooperation. Instead, Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison finds that voters prefer their own party to work alone. In a later set of experiments Bauer, Yong and Krupnikov (2016) finds evidence that preferences for uncooperative legislators are heterogeneous. The authors find that women legislators are punished more than male legislators for uncooperative behavior, and the gender effect is conditional on issue type.

One reason we might expect legislators to not want to cooperate even on something that is popular, like district spending, is because, as shown by Fenno (1978), legislators must be readily able to explain their votes to their district. Given high levels of negative polarization, it is likely that these legislators do not want to explain compromising with the other party (Binder and Lee, 2015). The legislative process matters then because it signals to voters the legislative composition of the final bill. The act of compromise by legislators is likely to compromise the ideological output of a bill. This should be fairly intuitive; a bill that is passed with only members of the Republican Party is more likely to advance the Republican Party’s interests than a bill that is passed through consensus. Voters prefer their party to advance their interests. Specifically, a related experimental study finds subjects prefer legislation when their own party excludes the other party in experimental studies precisely because voters’ partisan identity is more important to them than any moral desire for bipartisanship (Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison, 2014).

Voters prefer legislation to ass when their own part receives credit. But this credit does not manifest constantly. For in-partisans, I propose they will prefer legislation to be passed without the other party. This is because it implies an ideological component to the bill. It shows that their party won over the other party. These are some mechanisms that drove the result in Huet-Vaughn (2019), where he looked at the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and found that Democrats received a vote share bonus for providing projects in their districts, but Republicans did not.

However, for out-partisans, I argue they will prefer legislation to be passed through bipartisanship. This is because it signals that their party is involved with the bill. Through bipartisanship, the bill is going to be viewed as fairly moderate as opposed to being ideological (Westwood, 2021). This is the opposite of a non-cooperative bill, which partisans will see as ideological.

Producing district spending is still a productive strategy for members of Congress. Even under polarization, voters still enjoy getting things that others do not. Polarization has not really changed that the public still finds fixing roads or other district-level spending as something that is very popular, even when attaching a party label.5 This should be manifest in comparison between the member giving the district spending and the party.

Protocol

On the broad question of what the electoral returns are for district spending, there are two main avenues of research. The first, more traditional design is to use observational data to get real-world estimates (Levitt and Snyder, 1997; Huet-Vaughn, 2019). However, with observational studies, it is hard to get all the dimensions that are needed to test my theory. For example, in one of the most relevant papers to the present paper, Huet-Vaughn (2019) uses a difference-in-difference design to estimate how voters respond to a partisan bill. So, he can get an estimate of how voters reward (or do not reward) members who are left out and compare them to members who were involved in the bill’s passage. While this is an extremely valuable study, it does not allow for the ability to look at individual voters and how they respond to the member as a function of their own partisanship.

Experimental designs, while lacking some of the realism of observational studies, allow researchers more control. However, there have been no experimental designs looking at the effect of the legislative process on the rewards for credit claiming for district spending.6 However, there are studies that look at the effect of the legislative process on the evaluation of legislators in other domains. Most relevantly, Bauer, Yong and Krupnikov (2016) look at how voters evaluate Members of Congress who are uncooperative across different issue domains (energy and education), and they also vary the gender of the legislator.

I prefer the experimental approach because it allows me to estimate an appropriate counterfactual. For example, in Bauer, Yong and Krupnikov (2016), they can compare a woman legislator who does not compromise on education policy with a man who does not compromise on education policy. And then compare that difference between a woman who does not compromise on energy policy to a man who does not compromise on energy policy and they can do all of this while minimizing confounding factors. In the present study, I am interested in comparing the effects of credit claiming when one party produces a bill to the effects when both parties produce a bill. Then, how the partisan identity of the voter mediates this relationship. For this, I need to compare apples to apples. If I were to compare multiple real-world bills, I would run into the issue that legislator’s credit claiming behavior is strategic; legislators are trying to maximize their chances of re-election and are going to behave strategically for re-election. Further, many bills pass over a legislative session, thus it is hard to attribute the effect of just one bill or just a few bills to variances in voter evaluations of their representatives.

In late July 2021, the survey sampling firm Lucid recruited 1,283 subjects to participate in my study. The experimental subjects were told they would be participating in a study on political representation. After consenting to take part in the study and verifying that they were over the age of 18, subjects took a short survey asking basic demographic information. The subjects then encountered a signposting page where they read that the following survey would ask about “how people form opinions about their representatives.”

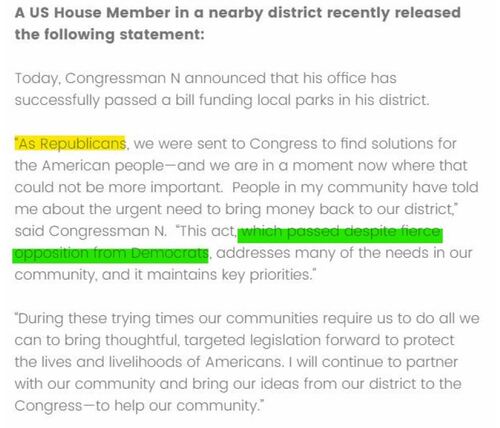

Once the experimental subjects continued past the signposting paragraph, they received the experimental prompt. In the press release claiming credit for funding for a public park as seen in Figure 1, the member mentions their own party (As Republicans/As Democrats) and then explains the legislative process (which passed despite fierce opposition/which passed with bipartisan support).

The experimental subjects rated the Member of Congress on a 100-point scale, along with each party in Congress, Congress itself, and their feelings towards the passage of the bill on a 7-point scale. Finally, the subjects assigned credit for the passage of the bill to either party or both. The main comparison is an interaction between the subject’s party and the member’s party within each coordination condition.

Voters’ Responses to Cooperation on District Spending

To analyze how people respond to federal spending in their district, I first collapsed my 7-point party identification rating to a binary scale of Republican and Democrat. Using simple arithmetic, I then compute a co-partisan variable with the respondent party identification and the party of the treatment that the respondent saw in the experiment. This variable represents when a survey respondent saw a member of the same party. I then run an OLS regression where I interact co-partisanship with the legislative process. In this regression, the dependent variable is the respondent’s feelings towards the member. Theoretically, there should be no variation between each of these conditions; funding for parks is not a partisan issue, so voters should not care which party is funding the parks or the process through which the park is being funded.7 These results can be found in Table 1.

The expectations were that co-partisans would view the non-cooperative member higher than the cooperative member, and that the out-partisans would view the non-cooperative member lower than the cooperative member. This is because credit is easily traced from the legislator to the outcome. In Table 1 I find this general pattern holds. Respondents who were from a different party than the hypothetical legislator and did not see a cooperation condition rated the hypothetical legislator the lowest. The largest substantive change was when the respondents shared partisanship with the legislator. Partisans prefer members of their own party. This makes sense. But that begs the question: How much does the legislative process matter? Out-partisans strongly prefer the legislation be passed through bipartisanship, or cooperation. But those effects disappear for co-partisans. Substantively, this has important implications for American Politics. While the main driver of the evaluation was co-partisanship, just working with the other party decreases the gap between out-party and in-party evaluations by half.8

These results show that the legislative process matters. Out-partisans are punishing the members for leaving their side out of the process, while in-partisans prefer their side work without cooperating with the other side. This shows that providing goods, especially through bipartisanship, is a useful strategy for legislators to win new voters.

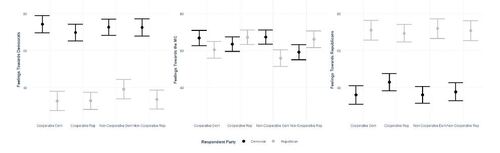

Providing district spending still improves the member’s standing among out-partisans relative to the party. The average rating of out-party partisans for the legislator was much higher than the rating for the legislator’s party. This is true for both parties; a graphical display of this can be found in Figure 2. The range of ratings on a 0-100 scale for the Democratic Party by Republican respondents was 32–41, compared to Democratic members being rated between 55-60 by Republican respondents. The same pattern holds for the feelings of democratic respondents. The Republican Party was rated between 36-44 by democratic respondents, while Republican members were rated between 60 and 63 by democratic respondents. These effects are substantially large, as are shown in Figure 2.9

Of note, the only reliable predictor of party feelings is respondent party. On the other hand, party is not always the largest substantive predictor of feelings towards the legislator in the experiment (even for out-partisans). This shows that providing district services greatly improves members’ standing in their own districts. However, this strategy might not be a reliable party strategy as the effects are limited to the member providing the benefits and not to the party at large.

Next, I test whether members cooperating has any effect on polarization. I do this by subtracting the respondents’ feelings towards Republicans from the respondents’ feelings towards Democrats, and then take the absolute value. This creates a measure of polarization; as the absolute difference grows, then respondents have more polarized views.

I then use this value in an OLS regression to test whether cooperation among Members of Congress affects feelings towards bipartisanship. In Table 2, there is no statistical effect of cooperation. However, the effect shows that cooperation leads to over a 2 and a half percent decline in polarization. When considering co-partisanship, these effects disappear. However, none of these effects are precise enough to reach statistical significance. These results show that providing services do not affect affective polarization as a whole even given the previous results showing that providing services do change voters’ opinions towards an individual member.

Overall, there is a very large effect in terms of the benefit that members receive for credit claiming. In Figure 2 the point estimate of feelings towards the out-party member crosses 50 in each case, suggesting that the experimental subjects at least did not harvest animosity towards out-partisan members. This, combined with the negative effect on cooperation in Table 2 is good news for democratic governance; even under polarization, legislators can still appeal to members of the other side by providing them with local-level services.

Further, these results shed light on research on voters’ preferences for bipartisanship. While voters prefer less ideological compromise on outcomes, they still reward legislators for providing them with positive outcomes, regardless of the legislative process. Here, in-party partisans do not give a boost (relative to the party) regardless of the legislative process, but out-party partisans give a boost to legislators, especially when there is bipartisanship.

While voters prefer bipartisanship, this paper cannot make claims about how bipartisanship translates into a change in vote share. The reason for this is that vote share is multi-factorial; a candidate’s final vote share is dependent on the turnout of (generally) two opposing candidates running campaigns against one another. In these campaigns, the candidates are raising funds to get their message out, trying to attract members of their own party to turn out to vote. They are also trying to persuade members of the opposing party to cross-party lines to vote for them. It stands to reason that the favorability of a candidate (along with the favorability of the opposing candidate) can affect the candidate’s success in each of these stages. Further research must be done to see how all these factors relate to one another.

Conclusion

This paper asks a simple question: What are the limits of credit claiming? I proposed a theory that voters would prefer legislative outputs that have as much of their own party’s influence on it as possible. I predicted voters would prefer in-party legislators who do not work with the out-party. Out-party voters prefer legislators to work with members of their own party. I then predicted that even these partisan biases would not overwhelm the positive effects of credit claiming.

To test my theory, I provided experimental subjects with a 2x2 factorial experiment that randomized the member’s party and the level of cooperation. I then tested how people view a hypothetical Member of Congress, along with each party. A few results stand out from my analysis. First, in-party partisans prefer their legislators to work alone, while out-party partisans prefer their legislators to build coalitions. This result is driven by credit for the party being clear when there is no cooperation. Then, I analyze the parties and find that these ratings are driven largely by partisan attitudes, while the ratings of the members are driven in response to the spending. Finally, I test to see if cooperation influences polarization. I do not find any evidence thereof, but I find a substantially large negative effect. Overall, this shows that credit claiming is a viable strategy for candidates, especially those hoping to attract voters from the out-party.

Appendix

Credit Claiming of District Spending in the Wild

Figure 1 shows one such example from Democratic Congresswoman Lizzie Fletcher from Houston Texas. In the example, Congresswoman Fletcher is claiming credit for her role in getting a very large grant from the Department of Transportation to fund improvements in the metro system in the city of Houston. In this example, Congresswoman Fletcher is claiming credit for spending that will both help out her own district, but the city more broadly.10 She also invokes her positions on the committee assignment to show that she was important to the passage of the bill.

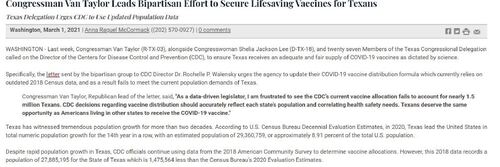

Van Taylor a conservative Republican from Plano, Texas also participates in a very similar type of credit claiming as is seen in Figure 2. In this situation, Representative Taylor is claiming credit for getting the CDC to send more vaccines to the state of Texas. One important thing to note in the two provided examples is that Congresswoman Fletcher does not mention any type of process that produced the funds for the Houston METRO, she just asserts her credit by saying that she is on the transportation and infrastructure committee. Representative Taylor, on the other hand, does not actually produce any legislation but he mentions the process several times. In the title of the press release, he mentions that getting additional vaccines was a “Bipartisan Effort” and then in the first line he mentions that “Sheila Jackson Lee and twenty seven members” from Texas helped him secure the vaccines.

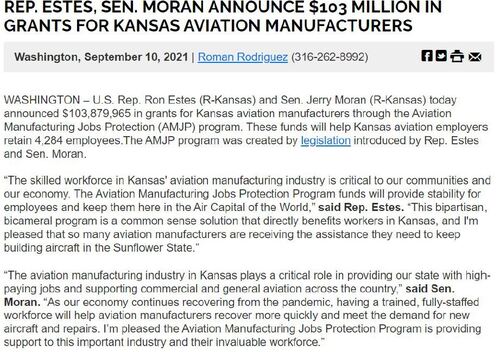

It is rare for a legislator to mention the opposing party being uncooperative while credit claiming for district spending. This is likely due to norms of universalism surrounding distributional politics (Weingast, 1979). Instead, they will reserve these mentions while talking about policy. However, legislators will still give ideological cues in their credit claiming, such as House of Representative members mentioning that the work was a joint effort with a prominent senator in the state or will mention the president. By a House members aligning themselves with party figures who are recognizable to voters as, it helps to cue an ideological shift to the policy–even if the policy is largely devoid of ideology. This is what Representative Ron Estes, a Republican from Kansas, is doing in Figure 3. Here, Congressman Estes is connecting Senator Jerry Moran who is a longtime Kansas Republican party figure, to an aviation grant for companies in Wichita, Kansas. Importantly, All the companies who received the grant that Estes are located in his district, a constituency that Senator Moran has never represented until he became a Senator in 2011, despite being an elected official since 1989.

Respondents by Condition

Additional Analyses

Tables to Make Figure 2 in Main Text

In the main text Figure 2 shows the predicted values of the analysis in Table 2. As is shown in the main text, the only variable that can reliably predict feelings towards the parties is the respondents party. On the other hand, treatment assignment has a large influence over the feelings towards the hypothetical legislator. Additionally, regardless of treatment assignment both party members liked the legislator more than they liked the other party even they did not share partisanship with them.

Feelings Towards Congress

Feelings towards Congress was included in the survey to test whether bipartisanship increased feelings towards Congress as an institution. Given that I did not expect my treatment to move the individual parties, I did not have strong expectations that I would be able to move feelings of the institution. Indeed, as is shown in Table 3 I am not able to move feelings towards Congress.

Who Gets Credit for the bill?

Next, I analyze which party respondents believe deserve credit for the passage of the bill. Here I expected in the cooperative condition for respondents to give credit to both parties and to give credit to the party that passed the bill in the non-cooperative conditions. I find in Table 4 co-partisan republicans match to expectations perfectly, but other than that, the results go against expectations.

Notes

3 But heterogeneity in rewards to members is not new in distributional politics; in a seminal paper on district spending Stein and Bickers (1994) finds legislators receive the most rewards among the most attentive voters.

4 This can be seen by members of Congress, too. Members use different strategies, including emphasizing the legislative process. See Appendix for examples.

5 For a short write-up with recent public opinion data see: https://bit.ly/3P7Xy7b

6 One exception would be Westwood (2021) however his dependent variable is overall support for the legislation, as opposed to support for the legislator.

7 Issues were tested in a pre-test on a student sample in Spring 2020 to avoid any partisan biases with the project type.

8 Predicted support for Co-Partisans is 68.82 in the no-cooperation condition and 67 in the cooperation condition, while predicted support for out-partisans is 57 in the no-cooperation condition and 62.17 in the cooperation condition.

9 Figure 2 displays the predicted values of three regressions where feelings towards the relevant party are the dependent variable and then an interaction between treatment assignment and respondent party. I do not use the co-partisan value above because it is a function of member party which is randomized.

10 Though, she does not point that much of the money from this grant will go outside of her district.

Table 1 Experimental Respondents by Condition

Table 2 Testing for Spillover Effects

Table 3 Effect of Legislative Process on Feelings towards Congress

Table 4 Which Party Deserves Credit for the Passage of the Bill?

Table 1 Feelings towards Member Giving Federal District, by Co-partisanship and Process

Table 2 Effects of Cooperation on Polarization

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (87.9 KB)References

- Abramowitz, Alan I. and Steven W. Webster. 2018. “Negative Partisanship: Why Americans Dislike Parties But Behave Like Rabid Partisans.” 39:119–135.

- Abramowitz, Alan I. and Steven Webster. 2016. “The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century.” Electoral Studies 41:12–22.

- Bauer, Nichole M., Laurel Harbridge Yong and Yanna Krupnikov. 2016. “Who is Punished? Conditions Affecting Voter Evaluations of Legislators Who Do Not Compromise.” Political Behavior 39(2):279–300.

- Binder, Sarah and Frances Lee. 2015. Solutions to Political Polarization in America. Cambridge University Press chapter Making Deals in Congress, pp. 240–262.

- Evans, Diana. 2004. Greasing the Wheels: Using Pork Barrel Projects to Build Majority Coalitions in Congress. Cambridge University Press.

- Fenno, Richard F. 1978. Home Style: House Members in Their Districts. Little Brown.

- Grimmer, Justin. 2013. “Appropriators not Position Takers: The Distorting Effects of Electoral Incentives on Congressional Representation.” American Journal of Political Science 57(3):624–642.

- Harbridge, Laurel. 2015. Is Bipartisanship Dead?: Policy Agreement and Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives. Cambridge University Press.

- Harbridge, Laurel, Neil Malhotra and Brian F. Harrison. 2014. “Public Preferences for Bipartisanship in the Policymaking Process.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 39(3):327–355.

- Harden, Jeffery J. 2015. Multidimensional Democracy: A Supply and Demand Theory of Representation in American Legislatures. Cambridge University Press.

- Hetherington, Marc J and Thomas J Rudolph. 2015. Why Washington won’t work. University of Chicago Press.

- Hopkins, Daniel J. 2018. The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized. The University of Chicago Press.

- Huber, Gregory A. and Neil Malhotra. 2017. “Political Homophily in Social Relationships: Evidence from Online Dating Behavior.” The Journal of Politics 79(1):269–283.

- Huet-Vaughn, Emiliano. 2019. “Stimulating the Vote: ARRA Road Spending and Vote Share.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11(1):292–316.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Tobias Konitzer and Kent Tedin. 2018. “The Home as a Political Fortress: Family Agreement in an Era of Polarization.” The Journal of Politics 80(4):1326–1338.

- Jacobson, Gary C. 2015. “It’s Nothing Personal: The Decline of the Incumbency Advantage in US House Elections.” The Journal of Politics 77(3):861–873.

- Lapinski, John, Matt Levendusky, Ken Winneg and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 2016. “What Do Citizens Want from Their Member of Congress?” Political Research Quarterly 69(3):535–545.

- Lee, Nathan, Michelangelo Landgrave and Kirk Bansak. 2022. “Are Subnational Policymakers' Policy Preferences Nationalized? Evidence from Surveys of Township, Municipal, County, and State Officials.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 48(2):441–454.

- Levitt, Steven D. and James M. Snyder. 1997. “The Impact of Federal Spending on House Election Outcomes.” Journal of Political Economy 105(1):30–53.

- Mayhew, David R. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. Yale University Press.

- Polborn, Mattias K. and James M. Snyder. 2017. “Party Polarization in Legislatures with Office-Motivated Candidates.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(3):1509–1550.

- Sievert, Joel and Seth C. McKee. 2018. “Nationalization in U.S. Senate and Gubernatorial Elections.” 47(5):1055–1080.

- Stein, Robert M. and Kenneth N. Bickers. 1994. “Congressional Elections and the Pork Barrel.” The Journal of Politics 56(2):377–399.

- Weingast, Barry R. 1979. “A Rational Choice Perspective on Congressional Norms.” American Journal of Political Science 23(2):245.

- Westwood, Sean J. 2021. “The Partisanship of Bipartisanship: How Representatives Use Bipartisan Assertions to Cultivate Support.” Political Behavior .

- Wichowsky, Amber. 2012. “District Complexity and the Personal Vote.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 37(4):437–463.