ABSTRACT

The theoretical lens of translation as activism underscores the ways translation has been used to make social change happen. Despite the growing interest in activist translation, few studies have been carried out on translation and activism in the context of China. This study examines the translator as an activist through a case study on Yan Fu (1854–1921), a pioneer activist translator in the late Qing. It investigates Yan Fu’s activist agendas manifested in the prefaces to his translations. It is found that Yan’s activist agendas in translation include saving the nation, opposing autocratic monarchy and strengthening the country, which are closely related to the historical context of the late Qing. Furthermore, this study discusses the interactive and cyclical relationship between translation and activism through the case of Yan Fu, which goes a step further than the one-way conceptualisation of translation as a tool of activism. As the activist side of Yan Fu’s translation has not received much attention previously, this study offers new insights into Yan’s translation practice from the activist perspective.

1. Introduction

The perspective of translation as activism underlines the ways translation has been used to promote cultural, ideological, and social change. In general, activism refers to “intentional action whose aim is to bring about social, political, economic, or environmental change” (Brownlie Citation2010, 45). The area of translation and activism has attracted a burgeoning body of scholarship in recent years, covering topics such as activist translation communities (Baker Citation2006), translation and language-related activism (Koskinen and Kuusi Citation2017), and translation and cyberactivism (Pérez-González Citation2010). As Tymoczko (Citation2010) suggests, the concept of activism can shed new light on the translators in China at the turn of the twentieth century. Despite the growing worldwide interest in activist translation, few studies (Cheung Citation2010; Gao Citation2020) have been carried out on translation and activism in the context of China.

The current study fills this gap by examining the translator as an activist through a case study on Yan Fu (1854–1921), a pioneer activist translator in the late Qing. This study investigates Yan Fu’s activist translation practice by addressing the following research questions: 1) What activist agendas did Yan Fu aim to achieve in his translation practice? 2) How did Yan Fu manifest his activist agendas in the prefaces to his translations? The following sections will start with introducing the theoretical perspective of translation as activism and reviewing the existing literature in this area. Prefaces to Yan’s translation works will then be analysed to examine the activist agendas he set out to achieve in translation. A discussion will follow to explore the relationships among Yan’s agendas and the interaction between translation and activism.

2. Literature review: the theoretical perspective of translation as activism

The current study is based on Tymoczko’s (Citation2000; Citation2007; Citation2010) theoretical perspective on translation and activism. Activism as an umbrella term for various social interventions is not limited to dramatic demonstrations but many other forms of political involvement. This study adopts the definition of activism as “action taken to challenge the status quo” and “to effect change” (Cheung Citation2010, 240). Tymoczko (Citation2010) associates translation with activism and underlines the ways translation has been used instrumentally to promote cultural, ideological, and social change in target cultures. Tymoczko (Citation2007, 213) conceptualises translation as a form of activism – “translations that are forms of speech acts associated with activism: translations that rouse, inspire, witness, mobilise, and incite to rebellion.” The activist agendas are the “motivations and purposes of activism,” varying from cultural nationalism, to self-determination of peoples, to national independence, which are highly subject to the cultural and political contexts (Tymoczko Citation2010, 15).

The studies of translation and activism are influenced by Toury’s (Citation1985, 19) statement of the importance of “the target system.” Descriptive translation studies correlated the translation shifts within the historical, social and political contexts of the target culture, which made the active role of translators more evident. In the 1990s, there was rising awareness of translators’ visibility and agency. For example, Venuti (Citation1995) called for translators to be involved in cultural and political struggles. The notion of “resistance” associated with Venuti (Citation1995) suggests resisting the opponent’s force. Tymoczko (Citation2007, 210; Citation2010, 10) argues that resistance is only “a reactive view of activism rather than a proactive one.” Besides resistance, the other concept in translation and activism is “engagement,” which implies a variety of enterprises initiated by the activists and suggests a more proactive stance (Tymoczko Citation2010).

The research area of translation and activism covers a wide range of studies with various understandings of activism. In some scenarios, activism in translation is investigated with historical cases. In the liberation movement in Hispanic America, translation played the activist role of transmitting revolutionary ideas (Bastin, Echeverri, and Campo Citation2010). Similarly, in Islamic Marxist movements in Iran, translation served to transfer new knowledge to society, promoting social reform and political change (Ghessimi Citation2019). During the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the Palestinian people’s armed struggle was reframed as resistance through translation (Dubbati and Abudayeh Citation2018). In other cases, contemporary activist translators and interpreters are studied, including activist translation communities (Baker Citation2006, Citation2016; Boéri Citation2008), minority language translators (Taronna Citation2016; Koskinen and Kuusi Citation2017), gender and sexuality in translation (Baer and Massardier-Kenney Citation2016; Norma Citation2015) and queer activism and translation (Baer and Kaindl Citation2017; Baldo, Evans, and Guo Citation2021). With the emergence and rapid development of the internet, translation and cyberactivism has attracted increasing scholarly attention (Susam-Sarajeva Citation2010, Citation2017; Pérez-González Citation2010), marked by the use of electronic communication technologies.

Regarding the context of China, most studies on activist translation are limited to cultural transformation instead of political and social change, either in translation history (Lu Citation2007; Lin Citation2002) or online activism in contemporary China (Kang Citation2015; Guo Citation2017; Yuan Citation2020). Some scholars go beyond mere cultural implications to discuss political activism realised by translators and translation activities in Chinese history. The concept of activism has been used to explore the translation practice in the late Qing period (1840–1911) (Cheung Citation2010; Liu Citation2020). The activist translators in the Chinese communist movement in the 1920s-30s are also addressed (Guo Citation2008). Moreover, the specific translator Lu Xun’s role as an activist in China’s turbulent twentieth century is discussed (M. Gao Citation2020). Although Yan Fu has been referred to in studies on the late Qing activism, his activism in translation remains to be examined in-depth. Following this line, this article focuses on the pioneer translator Yan Fu and his activist translation practice with a detailed paratextual analysis.

3. Data: the paratextual prefaces to Yan Fu’s translations

The present research focuses on the paratextual prefaces to Yan Fu’s translation works, which serve as a concentrated exhibition of Yan’s activist agendas. Paratexts are places where translators can “signal their agenda” (Hermans Citation2009, 33); prefaces serve as the first forum to manifest Yan’s agendas. In line with paratexts as places of “translator visibility” (Batchelor Citation2018, 32), prefaces exhibit Yan’s standpoint as a visible translator, compared with the subtle activist textual strategies such as addition. Moreover, prefaces are “an excellent locus” for translators to “disseminat[e] their understanding to readers” (McRae Citation2012, 80). The paratextual prefaces are a concentration of Yan’s thoughts and arguments, compared with commentaries and notes that are more dispersed throughout the text. Although translators’ prefaces are the most widely studied type of paratexts, the most common preface writers in translated works are not translators (Tahir Gürçağlar Citation2013, 91). The prefaces examined in this study include both the translator’s prefaces and the “allographic prefaces” or prefaces “written by [a] third party and accepted by the author” (Genette Citation1997, 9).

This study analyses Yan’s activist agendas by examining the prefaces to his translations. Among Yan’s translation works, six have been selected because they are relevant to political activism, and five of them have prefaces. The translation works examined by this study are 天演論Tianyan Lun (On Evolution) (1898), 原富Yuan Fu (On Wealth) (1902), 羣己權界論Qunji Quanjie Lun (On the Boundary between Self and Group) (1903), 社會通詮Shehui Tongquan (A General Interpretation of Society) (1904) and 羣學肄言Qunxue Yiyan (A Study of Sociology) (2nd edition) (1908). There are three kinds of prefaces to Yan’s translation works: the original prefaces, the translator’s prefaces and the allographic prefaces written by Yan’s mentor and friends. The original prefaces are beyond the scope of this study because it scarcely involves translators’ activist agendas.

The allographic prefaces written by Yan’s mentor and friends at the request of Yan are of equal importance to the translator’s prefaces. In the late Qing, the prefaces to translation works written by translators and other cultural agents were incredibly influential because they served as the “introduction” for readers unfamiliar with the foreign countries and the original works (Wong Citation2011, 78). In Yan’s case, his mentor and friends who wrote prefaces for his translations were important to him. After Wu Rulun, Yan’s mentor, died in 1903, Yan lamented: “From now on, will there be other people who can preface my translation in the world?” (Yan Citation1903a, 127). Although the allographic preface writers may digress from the text in support of their own causes (Tahir Gürçağlar Citation2013), Yan’s case suggests aligned ideological stances and similar activist agendas between the translator Yan and his mentor and friends as invited preface writers. The allographic preface writers often “have a more established literary position than the translators” (ibid., 98). For instance, Yan’s mentor Wu Rulun was a master in Tongcheng school, one of the chief literary schools in the late Qing. Another preface writer Xia Zengyou was in the same reformist group as Yan, and they started a newspaper Guowen Bao (National News) to disseminate new knowledge and advocate reform in 1897 in Tianjin. The case of Gao Fengqian, Yan’s friend and the head of the compiling and translation bureau in the Commercial Publishing House, is slightly different. Yan invited Gao to write the preface when his translation work was reprinted in the Commercial Publishing House in 1908, as seen in the title “Preface to amending Qunxue Yiyan.” This study examines both the allographic prefaces and Yan’s translator’s prefaces to discuss the activist agendas reflected in them. The prefaces selected for analysis in this study are summarised in .

Table 1. The paratextual prefaces to Yan Fu’s translation works analysed in this study:.

4. Analysis: Yan Fu’s activist agendas reflected in the prefaces to his translations

4.1 Saving the nation

Yan Fu’s activist agenda of saving the nation was associated with his patriotism in a time of national crisis. The decline of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the last imperial dynasty of China, was marked by political instability and social upheavals ignited by foreign imperialism. The process of foreign expansion began with the First Opium War (1839–1842) and intensified when Japan started the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). China’s defeat in the wars resulted in the “unequal treaties,” further conceding China’s territorial and sovereign rights (Ladds Citation2016). The escalating national crisis triggered a sense of patriotism or the willingness to defend their country among the intellectuals and students. Furthermore, the idea of patriotism at the time was associated with the concept of “保種” (preserving the race), with “種” (race) referring to China. Against the impending danger of foreign invasion, the appeal for patriotism or “loving the country” often appeared together with “preserving the race” (Z. Wu Citation2014).

Yan articulates the activist agenda of saving the nation in his preface to Tianyan Lun (On Evolution), which was translated from Thomas Henry Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics (1893) and “Evolution and Ethics Prolegomena” (1894). Yan upholds that Huxley’s book “repeatedly expresses the intention of self-strengthening and preserving the race” (Yan Citation[1898] 1986, 1321). Nevertheless, the concept of “preserving the race” has no basis in the source text, which implies the translator Yan’s intention. Similarly, in Yan’s mentor Wu Rulun’s preface to Tianyan Lun, the activist agenda of saving the nation is reiterated. Wu associates Huxley’s discourse with the survival of their country and race, as seen in the following excerpt.

以人持天,必究極乎天賦之能,使人治日卽乎新,而後其國永存,而種族賴以不墜 … … (Wu Citation[1898] 1986, 1317)

[For] man controlling nature, [we] must exhaust the talent endowed by nature so that governance of man is close to renewal day by day, and then their country can survive forever, and the race can depend on it and not decline … Footnote1

In the first paragraph of his preface to Tianyan Lun, Wu contends that “以人持天” (man controlling nature) is conducive to the survival of their country. Huxley’s discourse of “man controlling nature” is central to the source text and Yan’s translation. Yan Citation1898] 1986, 1321) states clearly in his preface that Huxley’s book aims to correct Herbert Spencer’s fallacy of “任天爲治” (letting nature rule). Wu advocates “man controlling nature” to realise the goal that his country survives and his race does not decline. At the end of his preface, Wu repeats this agenda of saving his nation and race.

抑嚴子之譯是書,不惟自傳其文而已,蓋謂赫胥黎氏以人持天,以人治之日新,衞其種族之說,其義富,其辭危,使讀焉者怵焉知變,於國論殆有助乎? (Wu Citation[1898] 1986, 1318)

Perhaps Yan’s aim in translating this book was not just to demonstrate his literary talents. Instead, he thought that Huxley’s theory of man controlling nature and defending their race by daily renewing governance of man would, because of its rich meaning and outright writing, make those who read it fearful and aware of the [need for] change. This would probably be helpful to the discussion on national issues.

In this quote, Wu highlights “defending their race” in his explanation of Huxley’s theory. He also speculates that Yan translated Huxley’s book to make readers “fearful and aware of the [need for] change,” which aligns with Yan’s advocate for reform and social change. “The discussion on national issues” implies his concern for their country and a sense of patriotism.

Moreover, Yan’s activist agenda of saving the nation is manifested in the preface to Shehui Tongquan (A General Interpretation of Society), his 1904 translation of Edward Jenks’ A History of Politics. In the preface written by Xia Zengyou, Yan’s friend and a reformer, one of the keywords is “救危亡” (saving [China from] danger and extinction). Xia contends that “變法” (changing the ways), a historical expression of reform in the late Qing period, aimed at “saving [China] from danger and extinction,” as seen from the following quote.

神洲自甲午以來,識者嘗言變法矣,然言變法者,其所志在救危亡,而沮變法者,其所責在無君父。(Xia Citation[1904] 1981, vi)

In the Divine Land since 1894, people of insight have attempted to talk about changing the ways. However, those who talk about changing the ways aspire to save [China] from danger and extinction, while those who resist changing the ways criticise the argument of no fatherly monarch.

In this except, Xia first discusses the growing advocacy for “changing the ways” since 1894, when the First Sino-Japanese War broke into the Divine Land, a poetic name for China. The activist agenda of saving the nation is exhibited as these efforts for reform and change were intended to “save [China] from danger and extinction.” Then Xia reveals that those against “changing the ways” or reform oppose the idea of “無君父” (no fatherly monarch). In his following discussion, Xia refutes this view by demonstrating that reform entails resisting absolute monarchy. The following section will unravel a detailed analysis of Yan’s activist agenda of opposing autocratic monarchy.

4.2 Opposing autocratic monarchy

The autocratic system existed in imperial China for over two thousand years (Hou Citation2005). Autocracy is defined as “government or control by one person who has complete power” (Collins English Dictionary). In the case of imperial China, power was centralised in the hand of the emperor. The primary political system in China was “autocracy centring the power of the emperor” from the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) (Hou Citation2005). Yan explicitly expresses his stance against autocracy in his political critique by accusing the emperor of “stealing the country from the people” (Yan Citation[1895] 1986, 35).

Yan’s activist agenda of opposing autocratic monarchy is manifested in the prefaces to his translation work Shehui Tongquan (A General Interpretation of Society). The two prefaces are written by Yan himself and Xia Zengyou, his reformist friend. As the autocracy in the late Qing features the emperor’s absolute power, opposition to autocracy is expressed in specific criticism of the monarchical power. Both Yan and Xia supported the constitutional monarchy, calling for restricting the monarchical power rather than eradicating the monarch. In the late Qing, the reformist appeal for limiting the emperor’s power was still rebellious and outrageous for the conservatives. As mentioned above, “無君父” (no fatherly monarch) is another crucial argument in Xia’s preface to Shehui Tongquan. The idea of “no fatherly monarch” refers to de-divinise the supreme fatherly monarch. In Xia’s preface to Shehui Tongquan, he elaborates on the link between saving China and opposing autocratic monarchy, as shown in the following quote.

政治與宗敎旣不可分,於是言改政者,自不能不波及於改敎,而救危亡與無君父二説,乃不謀而相應 … … (Xia Citation[1904] 1981, viii)

Since politics and the revered teaching are inseparable, those who spoke of changing politics could not but involve changing the revered teaching. The two arguments of saving [China] from danger and extinction and no fatherly monarch coincide …

The main argument in Xia’s preface is that the two appeals of “saving [China] from danger and extinction” and “no fatherly monarch” agree with each other. According to the preceding text, saving the nation from peril is a political issue, and eliminating the monarch is related to “宗敎” (the revered teaching), specifically Confucianism. By revealing that Confucius’ philosophy was in favour of maintaining the monarchical power, Xia directly appeals for changing Confucianism and opposing autocratic monarchy. In the following excerpt, Xia discloses the philosophy and mechanism behind “君權” (the monarchical power):

孔子之術,其的在於君權,而徑則由於宗法,蓋藉宗法以定君權,而非借君權以維宗法。(Xia Citation[1904] 1981, vii)

Confucius’ way is for the monarchical power through the patriarchal clan system. It is to establish the monarchical power by using the patriarchal clan system, not to maintain the patriarchy by the monarchical power.

According to Xia, Confucianism and “宗法” (the patriarchal clan system) aim to establish monarchical power. Citation[1904] 1981, vii) further explains that monarchical power has existed for as long as the patriarchal clan system. In line with Xia’s objection to the monarchical power, Yan calls for changing the patriarchal clan system. In the translator’s preface to Shehui Tongquan, Yan (Citation[1904] 1981, ix) demonstrates that the general evolutionary trend of societies in the world is from “圖騰” (the totemistic society) to “宗法” (the patriarchal clan society) to “國家” (nation). After reviewing Chinese history, Yan (ibid., ix–x) accuses the patriarchal clan system of “existing in China for over four thousand years.” By depicting the general trend of social evolution, Yan calls for Chinese society to end the patriarchal stage.

Moreover, Yan explicitly opposes “专制之治” (autocratic rule) and advocates for people’s liberty in the preface to Qunji Quanjie Lun 群己权界论 (On the Boundary between Self and Group) translated from John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. Yan Fu starts by discussing three types of people who strive for liberty under different systems of rule: aristocracy, autocracy and constitutional democracy. Discussion on the struggle against autocracy is as follows.

專制之治,則民對君上而爭自繇 … … (Yan Citation[1903b] 1981, ix)

Under the autocratic rule, the people fight for liberty against monarchs …

然其所論,理通他制,使其事宜任小己之自繇,則無間君上貴族社會,皆不得干涉者也。(Yan Citation[1903b] 1981, ix)

However, his argument also applies to other systems. It makes the issue of individuals’ liberty a thing that cannot be interfered with in either a monarchical or an aristocratic society.

Among the political systems where people seek liberty, the rule of autocratic monarchy is the most relevant to the late Qing. Although Mill originally wrote about the British context, Yan extends Mill’s discussion to other contexts by declaring that Mill’s argument also “applies to other systems.” Considering the late Qing context, Yan presumably advocates for the Chinese people fighting for liberty, especially against the autocratic monarchy.

4.3 Strengthening the country

The agenda of strengthening the country was under the influence of “自強運動” (the self-strengthening movement) (1861–1895), a government-led modernisation movement. After China’s defeat in the Second Opium War (1856–1860), the government officials, exemplified by Li Hongzhang (1823–1901), realised China’s military and technological backwardness and initiated the self-strengthening movement (Jiang Citation2006). The movement aimed to strengthen China by learning modern science and technology from Western countries. Despite the failure of this movement, the idea of self-strengthening and making progress gained popularity among the late Qing scholar-officials. In the preface to Tianyan Lun (On Evolution), Yan manifests his activist agenda of strengthening the country. As discussed above (See Section 4.1), Yan upholds that Huxley’s book “repeatedly expresses the intention of self-strengthening and preserving the race.”

National wealth and prosperity are crucial elements in strengthening the country, as addressed in Yan’s preface to Yuan Fu (On Wealth), translated from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. In this preface, Yan notes the importance of economics to “黃種之盛衰” (the prosperity and decline of the yellow race) as follows.

夫計學者,切而言之,則關於中國之貧富; 遠而論之,則係乎黃種之盛衰。(Yan Citation[1902] 1981, 13)

The economics, in the short term, is about the wealth and poverty of China; in the long term, [it] concerns the prosperity and decline of the yellow race.

This quote illustrates Yan’s activist agenda of promoting national development by translating this vital book about economics. Yan also explains his understanding of “wealth” and “prosperity:” short-term and long-term goals. The two topics are central to Yan’s activist translation practice, as Schwartz (Citation1964) noticed in his book In Search of Wealth and Power.

Similarly, “盛衰” (prosperity or decline) is a keyword in the preface to Yan’s translation work Qunxue Yiyan (A Study of Sociology), rendered from Herbert Spencer’s The Study of Sociology. By describing the study object of sociology as clarifying the reasons behind good governance and disorder as well as prosperity and decline, Yan reveals his activist agenda of improving social governance and pursuing national prosperity.

羣學者,將以明治亂、盛衰之由 … … (Yan Citation[1908] 1981, vii)

Those who study sociology will clarify the causes of good governance and disorder and prosperity and decline …

As Yan describes, good governance and prosperity are interrelated. According to the traditional Confucian values, scholars should be concerned with improving the country’s governance. The agenda of strengthening the country is also manifested in achieving governance progress. In the allographic preface to Qunxue Yiyan written by Yan’s friend Gao Fengqian, “羣治” (governance of society) is a central concept that occurs eight times within the four short paragraphs. Gao points out the general concern of governance in the society:

無怪乎人人言羣治,日日言羣治,而羣治終不進也。(F. Gao Citation[1908] 1981, vi)

It is no wonder that everyone talks about the governance of the society, and it is talked about every day, but the governance of the society has never advanced.

This quote manifests Gao’s focus on improving social governance, a common appeal shared by Yan and the Confucian intellectuals, which is also in line with Yan’s activist agenda of strengthening the country. Both Gao and Yan’s prefaces explain that achieving the good governance of society and promoting their country’s prosperity are the reasons for translating this book on sociology.

5. Discussion: Yan Fu’s interrelated activist agendas in translation paratexts

Against the late Qing context of social turmoil and political upheaval, Yan’s activist agenda could be summarised as change and reform. More specifically, his activist agendas include saving the nation, opposing autocratic monarchy and strengthening the country. In line with the definition of activism adopted by this study as “action taken to challenge the status quo” and “to effect change” (Cheung Citation2010, 240), the three activist agendas uniformly underscore challenging the status quo. Despite the threat of foreign imperialist aggression, the majority of literati officials in the late Qing failed to realise the impending danger. After losing the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, the whole of China was shocked because the “great power” they thought they were was beaten by Japan, the “small country” in their mind (Z. Wu Citation2014). This shock indicates the arrogance and complacency that Yan endeavoured to challenge by advocating the activist agenda of saving the nation. Similarly, the agenda of strengthening the country aimed to change the backwardness of the late Qing, and opposing autocratic monarchy challenged the long-standing autocratic system.

What is noteworthy is the complex interrelation among Yan Fu’s three activist agendas. Through the close examination of prefaces to Yan’s translation works, this study finds that his three agendas are also closely intertwined. Saving the nation can be regarded as the central agenda, considering it was the goal of opposing autocratic monarchy and strengthening China. As discussed above, saving the nation involves throwing away autocracy, as suggested by the argument that changing politics involves changing the revered teaching in the preface to Shehui Tongquan (A General Interpretation of Society). Defending the country is also realised through improving the governance or self-strengthening, as implied in the preface to Tianyan Lun (On Evolution). Furthermore, the interrelated activist agendas display different temporal orientations. Saving the nation is the urgent and short-term agenda considering the imminent danger of the aggressive imperialist power. In contrast, strengthening the country is the ultimate long-term goal, as improving the governance of society and achieving prosperity remains a constant concern for Confucian scholars like Yan Fu. Schwartz’s (Citation1964, 18) seminal work concentrates on Yan’s long-term goal of strengthening the country or, in his words, “in search of wealth and power,” while scarcely deals with the short-term agenda of preserving the country, which he mentioned as “preservation of the state.” Opposing autocracy could be understood as dealing with historical issues, as Yan repeatedly suggests that this system has existed in China for too long compared with its Western counterparts. To summarise, the three agendas of opposing autocratic monarchy, saving the nation and strengthening the country exhibit different temporal orientations towards the past, present and future, respectively.

Through the analysis of Yan Fu’s translation paratexts, this study has found that the activist agendas are more explicitly demonstrated in the allographic prefaces written by Yan’s mentor and friends compared with Yan's own. In the analysis regarding saving the nation and opposing autocratic monarchy, both Wu Rulun, Yan’s mentor and Xia Zengyou, Yan’s reformer friend, articulate their arguments more directly. Similarly, in the case of Qunxue Yiyan (A Study of Sociology), Gao Fengqian’s preface expresses his concern about improving social governance more evidently. In contrast, Yan’s translator’s preface focuses on introducing the source text author and devotes more than half of the preface to an exquisite summary of each chapter. Presumably, Yan's allographic preface writers were influential figures and could have more discourse power and willingness to appeal for social change. This aligns with previous research that allographic preface writers are often important figures in the target culture with a high degree of symbolic capital (Tahir Gürçağlar Citation2013). Given that the allographic prefaces come before the translator’s prefaces, the evident activist agendas reflected in them may leave the readers with a profound impression.

Besides dealing with the texts that they accompany, prefaces reflect the translators’ and preface writers’ agendas. In the case of Yan Fu, the aligned activist agendas manifested in the translator’s and allographic prefaces to Yan’s translations epitomise the common pursuit of Confucian intellectuals in a time of national crisis. Genette (Citation1997) associates two functions with allographic prefaces in addition to original prefaces: presenting and recommending the text. In the case of Yan Fu, the first function of presenting the text, or providing information about the work, is often realised through his own prefaces. On the contrary, the prefaces written by his mentor and friends mainly carry out the function of recommending the text. Typically, the recommendation is made by a writer “whose reputation is more firmly established than the author’s” (Genette Citation1997, 268). Intriguingly, the recommendation of Yan’s work is strongly associated with the activist agendas conveyed in the prefaces. In the preface to Qunxue Yiyan (A Study of Sociology) by Gao, he highly praises the book by relating sociology to good governance and prosperity, implying the purpose of strengthening the country. Similarly, Yan’s own recommendation of Yuan Fu (On Wealth) also concerns the wealth and prosperity of his country. The underlying pursuit of national strength may be the driver for Yan to select these books to translate.

6. Implications: interaction between translation and activism

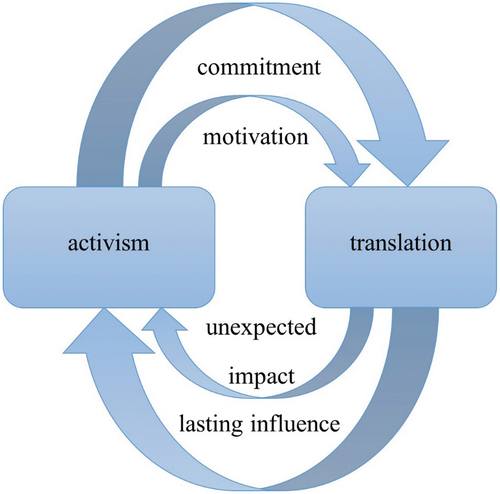

The relationship between translation and activism is not one-way but is “characterised by interaction, reciprocity and mutual reinforcement” (Cheung Citation2010, 253). The present study unravels how Yan Fu attempted to pursue his activist agendas in translation. However, translation is not simply understood as “a tool of activism” or “a catalyst for change” (ibid.). Instead, the thriving activism may also encourage the translation practice in turn. Translation and activism have a cyclical relationship with interaction and mutual reinforcement. At the turn of twentieth-century China, translation functioned not as a tool of activism but as a site where the change took place, as manifested in the passion of intellectuals and writers engaged in translating and the equal passion of the public reading the translations (ibid.).

Yan Fu’s trajectory exemplifies the interaction between translation and activism, as shown in . At first, Yan’s activism influenced his translation practice by motivating Yan to initiate translation as activism. This unintended motivation to start translation as activism is common among contemporary activists (Cheung Citation2010). Then, the unexpected success of Yan’s first translation work Tianyan Lun (On Evolution) may, in turn, encourage him to pursue activism through translation. The wide readership of Tianyan Lun and the far-reaching implications were beyond Yan’s expectations. Inspired by such success, Yan was more committed to translation as the channel for social change. He translated a series of seminal works to transmit Western thinking to China. As a result, Yan’s translations continued to exert a lasting influence on the political and social activism in the late Qing.

The unexpected trajectory of Yan Fu also indicates the difficulty of predicting the results and impact of activist translation practice. Besides the unexpected successes, like Tianyan Lun, the activist ideas and values could be deliberately misinterpreted or re-interpreted to various ends. In other words, people may borrow the newly translated ideas and interpret them in their ways. For example, Yan’s discourse on nationalism in Shehui Tongquan (A General Interpretation of Society) was manipulated to criticise revolutionaries (Wang Citation2005). This unpredictability makes it more necessary to study the dynamics of translation by taking into account various “domestic and international, contextual and circumstantial” factors that “might interact with or impinge upon” the translation work (Cheung Citation2010, 254).

Besides promoting activism through translation, Yan initiated multiple forms of activism complementary to translation. Yan’s activist practice was especially prominent after China’s failure in the First Sino-Japanese War. Besides translating, Yan wrote political articles, attended political events, and started newspapers to realise his activist agendas. Yan’s activist orientation is under the Confucian tradition of “經世” (statecraft), which suggests a concern with problems of state and society (Schwartz Citation1964). Yan articulates his worries about China’s circumstances in a letter to his son: “The current situation is dangerous and dreadful to think of” (Yan Citation[1894] 1986, 779). When thinking about his country in peril, Yan even woke up at midnight and cried (Yan Citation[1897] 1986, 521). With the social and political concerns, Yan pursued activism through translation and other complementary forms.

In the case of Yan Fu, translation seems a safer channel for realising activism compared with other activist practices such as writing political critiques. Within the three months after the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Yan wrote five political critiquesFootnote2 published in Zhi Bao (Straight News). The activist agendas reflected in the prefaces to Yan’s translation works align with the agendas in his political critiques. As previously mentioned, Yan criticises autocracy sharply in his article “Pi Han” (Refuting Han Yu) by accusing the monarch of stealing the country (Yan Citation[1895] 1986). However, the form of writing political critique was more likely to incur danger compared with translation. When Yan’s “Refuting Han Yu” was reprinted on Shiwu Bao (Chinese Progress), this article exposed Yan to danger. Zhang Zhidong (1837-1909), a relatively conservative high-ranking official, asked his staff to write an article refuting Yan and even considered harming Yan (H. Gao and Wu Citation1992, 141). In comparison, the translation channel seems safer than writing original articles in the late Qing context. Considering his famous xin-da-ya principles, Yan claims that translation conveys the source text’s ideas faithfully, which to some extent disguises his activist agendas in translation.

7. Conclusion

This study investigated Yan Fu’s activist agendas manifested in the prefaces to his translations. It found that Yan’s activist agendas in translation include saving the nation, opposing autocratic monarchy and strengthening the country, which are interrelated in the historical context of the late Qing. Furthermore, this study discusses the interactive and cyclical relationship between translation and activism through the case of Yan Fu, which goes a step further than the one-way conceptualisation of translation as a tool of activism.

Although translation and activism have attracted growing scholarly attention, few studies have examined translation as a channel for political and social change in the context of China. This study fills this gap through a case study on the pioneer activist translator Yan Fu in the late Qing. In line with paratexts as places of signalling the translators’ agenda (Hermans Citation2009), the present research examines how Yan’s activist agendas are demonstrated in the paratextual prefaces to his translation works. Overall, this study explores the often-ignored activist side of Yan Fu and offers new insights into Yan’s translation practice from the activist perspective.

Due to space constraints, this study only examines the paratextual prefaces to Yan’s translation works, which leaves room for future research. A more complete picture of Yan Fu as an activist translator will surely emerge from further diachronic studies on the activist agendas in Yan’s translation practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xiaorui Wang

Xiaorui Wang is a PhD candidate in Translation Studies at the University of Leeds. Her PhD project is “Translation as Activism: The Case of Yan Fu as a Pioneer Activist Translator in China at the Turn of the Twentieth Century”. Her research interests include translation and activism, translation history and the sociology of translation.

Notes

1. The gloss in the article is the author’s own translation.

2. The five political critiques are “Lun Shibian zhi Ji” [On the Speed of World Change], “Yuan Qiang” [On Strength], “Pi Han” [Refuting Han Yu] “Yuanqiang Xupian” [A Sequel to “On Strength”] and “Jiuwang Juelun” [On Rescuing China from Destruction].

References

- Baer, B. J. and K. Kaindl, eds. 2017. Queering Translation, Translating the Queer: Theory, Practice, Activism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Baer, B. J. and F. Massardier-Kenney. 2016. “Gender and Sexuality.” In Researching Translation and Interpreting, edited by C. V. Angelelli and B. J. Baer, 83–96. London and New York: Routledge.

- Baker, M. 2006. “Translation and Activism: Emerging Patterns of Narrative Community.” The Massachusetts Review 47 (3): 462–484.

- Baker, M. 2016. “The Prefigurative Politics of Translation in Place-Based Movements of Protest.” The Translator 22 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/13556509.2016.1148438.

- Baldo, M., J. Evans and T. Guo. 2021. “Introduction: Translation and Lgbt+/Queer Activism.” Translation and Interpreting Studies 16 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1075/tis.00051.int.

- Bastin, G. L., Á. Echeverri and Á. Campo. 2010. “Translation and the Emancipation of Hispanic America.” In Translation, Resistance, Activism, edited by M. Tymoczko, 42–64. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Batchelor, K. 2018. Translation and Paratexts. London and New York: Routledge.

- Boéri, J. 2008. “A Narrative Account of the Babels vs. Naumann Controversy: Competing Perspectives on Activism in Conference Interpreting.” The Translator 14 (1): 21–50. doi:10.1080/13556509.2008.10799248.

- Brownlie, S. 2010. “Committed Approaches and Activism.” In Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Y. Gambier and L. van Doorslaer, 1 vols, 45–48. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Cheung, M. P. Y. 2010. “Rethinking Activism: The Power and Dynamics of Translation in China During the Late Qing Period (1840-1911).” In Text and Context: Essays on Translation and Interpreting in Honour of Ian Mason, edited by M. Baker, M. Olohan, and M. C. Pérez, 243–264. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.

- Dubbati, B. and H. Abudayeh. 2018. “The Translator as an Activist: Reframing Conflict in the Arabic Translation of Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza.” The Translator 24 (2): 147–165. doi:10.1080/13556509.2017.1382662.

- Gao, F. [1908] 1981. “Dingzheng Qunxue Yiyan Xu” [Preface to Amending Qunxue Yiyan]. In Qunxue Yiyan [A Study of Sociology], edited by H. Spencer. Translated by Fu Yan, vi. Beijing: Commercial Press

- Gao, M. 2020. “‘The Pen is Mightier Than the Sword’: Exploring the ‘Warrior’ Lu Xun from 1903 to 1936.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Activism, edited by R. R. Gould and K. Tahmasebian, 461–478. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gao, H. and C. Wu. 1992. Fanyi Jia Yan Fu Zhuanlun [The Translator Yan Fu]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

- Genette, G. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, edited by J. E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ghessimi, H. 2019. “Translation and Political Engagement: The Role of Ali Shariati’s Translations in Islamic Marxists Movements in Iran in the 1970s.” Babel 65 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1075/babel.00073.ghe.

- Guo, T. 2008. “Translation and Activism: Translators in the Chinese Communist Movement in the 1920s-30s.” In Translation and Its Others: Selected Papers of the CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2007, edited by P. Boulogne. http://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/files/guo.pdf

- Guo, T. 2017. “The Role of Chinese Translator and Agent in the Twenty-First Century.” In The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Translation, edited by C. Shei and Z.-M. Gao, 553–565. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hermans, T. 2009. The Conference of the Tongues. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.

- Hou, J. 2005. “Fengjian Zhuyi Gainian Bianxi” [A Discussion of the Concept of ‘Fengjian’]. Social Sciences in China 26 (6): 173–188.

- Jiang, T. 2006. Zhongguo Jindai Shi [Modern Chinese History]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

- Kang, J.-H. 2015. “Conflicting Discourses of Translation Assessment and the Discursive Construction of the ‘Assessor’ Role in Cyberspace.” Target 27 (3): 454–471. doi:10.1075/target.27.3.08kan.

- Koskinen, K. and P. Kuusi. 2017. “Translator Training for Language Activists: Agency and Empowerment of Minority Language Translators.” Trans-Kom: Zeitschrift Für Translationswissenschaft Und Fachkommunikation 10 (2): 188–213.

- Ladds, C. 2016. “China and Treaty-Port Imperialism.” In Vol I of The Encyclopedia of Empire, edited by J. M. MacKenzie, 480-486. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Lin, K. 2002. “Translation and a Catalyst for Social Change in China.” In Translation and Power, edited by M. Tymoczko and E. Gentzler, 160–183. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Liu, K.-Y. 2020. “Late-Qing Translation (1840–1911) and the Political Activism of Chinese Evolutionism.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Activism, edited by R. R. Gould and K. Tahmasebian, 439–640. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lu, L. 2007. “Translation and Nation: Negotiating ‘China’ in the Translations of Lin Shu, Yan Fu, and Liang Qichao.” PhD diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- McRae, E. 2012. “The Role of Translators’ Prefaces to Contemporary Literary Translations into English: An Empirical Study.” In Translation Peripheries: Paratextual Elements in Translation, edited by A. Gil-Bardají, P. Orero, and S. Rovira-Esteva, 63–82. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Norma, C. 2015. “Catharine MacKinnon in Japanese: Toward a Radical Feminist Theory of Translation.” In Multiple Translation Communities in Contemporary Japan, edited by B. Curran, N. Sato-Rossberg, and K. Tanabe, 79–98. London and New York: Routledge.

- Pérez-González, L. 2010. “‘Ad-Hocracies’ of Translation Activism in the Blogosphere: A Genealogical Case Study.” In Text and Context: Essays on Translation and Interpreting in Honour of Ian Mason, edited by M. Baker, M. Olohan, and M. C. Pérez, 259–287. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.

- Schwartz, B. 1964. In Search of Wealth and Power: Yen Fu and the West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Susam-Sarajeva, Ş. 2010. “Whose ‘Modernity’ is It Anyway? Translation in the Web-Based Natural-Birth Movement in Turkey.” Translation Studies 3 (2): 231–245. doi:10.1080/14781701003647483.

- Susam-Saraeva, Ş. 2017. “In Search of an ‘International’ Translation Studies: Tracing Terceme and Tercüme in the Blogosphere.” Translation Studies 10 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1080/14781700.2016.1219273.

- Tahir Gürçağlar, Ş. 2013. “Agency in Allographic Prefaces to Translated Works: An Initial Exploration of the Turkish Context.” In Authorial and Editorial Voices in Translation 2: Editorial and Publishing Practices, edited by H. Jansen and A. Wegener, 89–108. Quebec: Éditions québécoises de l’oeuvre.

- Taronna, A. 2016. “Translation, Hospitality and Conflict: Language Mediators as an Activist Community of Practice Across the Mediterranean.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 15: 282–302.

- Toury, G. 1985. “A Rationale for Descriptive Translation Studies.” In The Manipulation of Literature: Studies in Literary Translation, edited by T. Hermans, 16–41. London: Groom Helm.

- Tymoczko, M. 2000. “Translation and Political Engagement.” The Translator 6 (1): 23–47. doi:10.1080/13556509.2000.10799054.

- Tymoczko, M. 2007. Enlarging Translation, Empowering Translators. Manchester: St Jerome Publishing.

- Tymoczko, M., eds. 2010. Translation, Resistance, Activism. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Venuti, L. 1995. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London and New York: Routledge.

- Wang, X. 2005. Yuyan, Fanyi Yu Zhengzhi: Yan Fu Yi Shehui Tongquan Yanjiu [Language, Translation and Politics: Yan Fu’s Translation of A History of Politics]. Beijing: Peking University Press.

- Wong, L.-W.-C. 2011. Fanyi Yu Wenxue Zhijian [Between Translation and Literature]. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press.

- Wu, R. [1898] 1986. “Wu Xu” [Wu’s Preface to Tianyan Lun (On Evolution)]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 1317–1319. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Wu, Z. 2014. Zhongguo Jindai Xiaoshuo Guannian Yanjiu [Research on Perceptions of Modern Chinese Novels]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.

- Xia, Z. [1904] 1981. “Xu” [Preface]. In Shehui Tongquan [A General Interpretation of Society], edited by J. Edward. Translated by Fu Yan, viviii. . Translated by Fu Yan, viviii. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

- Yan, F. [1894] 1986. “Yu Zhangzi Yan Qu Shu” [Letter to My Son Yan Qu]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 779–780. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Yan, F. [1895] 1986. “Pi Han” [Refuting Han Yu]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 32–35. Beijing:Zhonghua Book Company

- Yan, F. [1897] 1986. “Yu Wu Runlun Shu” [Letter to Wu Rulun]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 520–522. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Yan, F. [1898] 1986. “Zi Xu” [Preface to Tianyan Lun (On Evolution)]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 1319–1321. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Yan, F. [1902] 1981. “Yishi Liyan” [General Remarks on Translation]. In Yuan Fu [On Wealth], edited by A. Smith and F. Yan, 7–14. Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Yan, F. [1903a] 1986. “Yi Yu Zhuiyu” [Redundant Remarks After Translating The Study of Sociology]. In Yan Fu Ji [Collected Works of Yan Fu], edited by S. Wang, 125–127. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Yan, F. [1903b] 1981. “Yi Fanli” [General Remarks on Translation]. In Qunji Quanjie Lun [On the Boundary Between Self and Group], edited by J. S. Mill. Translated by Fu Yan, viix. . Translated by Fu Yan, viix. Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Yan, F. [1904] 1981. “Yizhe Xu” [The Translator’s Preface]. In Shehui Tongquan [A General Interpretation of Society], edited by J. Edward. Translated by Fu Yan, ixx. . Translated by Fu Yan, ixx. Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Yan, F. [1908] 1981. “Yi Qunxue Yiyan Xu” [Preface to Translating The Study of Sociology]. In Qunxue Yiyan [A Study of Sociology], edited by H. Spencer. 2nd Ed. Translated by Fu Yan, viiix. Translated by Fu Yan, viiix. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

- Yuan, M. 2020. “Ideological Struggle and Cultural Intervention in Online Discourse: An Empirical Study of Resistance Through Translation in China.” Perspectives 28 (4): 625–643. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2019.1665692.