Abstract

The role of social media in communicating emerging environmental issues has received little attention. One such issue is ocean acidification (OA), the process by which carbon dioxide (CO2) acidifies oceans. Although scientists consider OA to be as dangerous as climate change (CC) and both problems are caused by excess CO2 emissions, public awareness of OA is low. We investigated public discussions about CC and OA on Twitter, identifying frames and tweeter characteristics. Tweeting patterns before and after President Trump’s 1 June 2017 announcement of the U.S.’s withdrawal from the international Paris Climate Agreement were compared because of the potential for diverse framing of this globally communicated event. For CC tweets, Political/Ideological Struggle (PIS) and Disaster (DS) frames were prevalent, with PIS frames increasing threefold after Trump’s announcement. DS, Settled Science (SS), and Promotional frames were prevalent among OA tweets, with SS decreasing and PIS increasing after the announcement. Our findings suggest that Trump’s decision sparked discourse on CC and facilitated expressions of politicized opinions on Twitter. We conclude that with a careful understanding of issue familiarity among its publics, social media can be effective for disseminating information and opinion of established and emerging environmental issues, complementing traditional media outlets.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Ocean acidification (OA) is the process by which carbon dioxide (CO2) dissolves into and acidifies the world’s oceans. Scientists consider OA to be just as dangerous a problem as climate change (CC) and both problems share the same main cause (excess CO2 emissions), but most non-scientists are unaware of OA. We investigated how people discuss the well-known problem of CC and the lesser-known problem of OA on Twitter. We also compared CC and OA tweeting patterns before and after President Trump’s announcement of the U.S.’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement. The results suggest that Trump’s withdrawal decision sparked debate of CC on Twitter and that tweets about CC usually have a political bent or incorporate disaster themes. OA tweets also invoke disaster themes, but also tend to be “promotional” in nature (e.g. announcing a conference on OA) and are less political.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

There are over 3 billion social media users worldwide (Kemp, Citation2017). Social media applications include collaborative projects (e.g. Wikipedia), blogs, content communities (e.g. YouTube), social networking sites (e.g. Facebook), virtual social worlds (e.g. Second Life), and virtual gaming (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010). While Facebook is the most-used platform, use of other social media platforms such as the microblogging service Twitter has steadily increased worldwide: as of the second quarter of 2017, there are 328 million monthly active Twitter users (Statista, Citation2017). This rising popularity is one of the reasons that Twitter is of particular interest to scholars who study online communication.

Social media has played an important role in climate change (CC) communication (Schäfer, Citation2012). Social network analysis of CC discussions on Twitter show that users can be classified into climate “activist” and “skeptic” groups and that these groups more often interact among themselves in “echo chambers,” which tend to increase polarization on the topic (Williams, McMurray, Kurz, & Lambert, Citation2015). However, some between-group interactions (e.g. open forums) do occur, which can stimulate debate on CC (Williams et al., Citation2015). These discussion dynamics on social media have practical implications for offline CC communication because social media can influence mainstream media on scientific issues and because social media may have a greater influence on individuals’ perceptions of issues due to its public, participatory nature (Williams et al., Citation2015).

Despite active discussions of CC on social media, its role in communicating lesser-known environmental issues has not been well-studied, including issues that are closely related to CC. One example is ocean acidification (OA), which is the process by which carbon dioxide (CO2)—primarily produced from fossil fuel burning—acidifies the world’s oceans. OA is similar to CC in that both problems are caused by excessive CO2 emissions from human activities and thus the solution to both problems centers on emissions reduction strategies. The passage of the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act by U.S. Congress in 2009 and the introduction of additional OA legislation in 2017 demonstrates that politicians are aware of the problem. Although scientists consider OA to be just as “dangerous” a problem as CC (Monaco Declaration, Citation2008) with negative economic impacts already evident in some regions such as the U.S. Northwest Pacific Coast, public awareness of OA has been low (Capstick, Pidgeon, Corner, Spence, & Pearson, Citation2016; The Ocean Project, Citation2012). This may result in less conversation about the issue and little knowledge to take necessary actions among the public. OA may therefore be described as an “emerging” environmental issue in the public mindset (Yates et al., Citation2015).

The purpose of this study is, therefore, to compare how Twitter users communicate about CC and OA and to compare the content framing and external URL sources of tweets of these two interrelated issues before and after a major global event—U.S. President Donald Trump’s announcement on 1 June 2017 that he is withdrawing the U.S. from the 2015 Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement is a multi-national agreement concerning carbon emissions reductions within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This study also broadens our understanding of social media and environmental issues by shedding light on how different actors (e.g. scientists, politicians, activists, the general public) tweet about an established contested issue (CC) in comparison to an emerging issue (OA). A comparison of how the two issues are discussed on social media and who is engaging in the discourse could be useful for scientists and other advocates aiming to increase public awareness of OA. Furthermore, given that OA may be an effective frame for increasing support for carbon emissions reduction policies (Mossler, Bostrom, Kelly, Crosman, & Moy, Citation2017), it may be valuable to examine if and how Twitter users connect the two issues when thinking about anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

1. Social media, framing, and environmental issues

Social media has emerged as an important tool for advocacy, information dissemination, and protest of critical issues such as risk, health, and environmental communication. Although environmental issues are less personal than these other issues and more “psychologically distant” (Schuldt, McComas, & Byrne, Citation2016), people nevertheless use Twitter and other social media platforms to communicate about environmental topics. When the topics are contentious, discourse on social media may become segmented among users with varying opinions on the issue, as was shown in a Twitter analysis of hydraulic fracturing, a generally well-known and controversial method of extracting natural gas (Hopke & Simis, Citation2017). Most of the social media discourse on the publicly contentious issue of CC tends to occur within like-minded user groups, although some discussion between groups with differing perspectives does occur (Pearce, Holmberg, Hellsten, & Nerlich, Citation2014; Williams et al., Citation2015). Twitter can also be used as an organizing mechanism for collective environmentalism, as demonstrated by its use in two major CC protests related to the 2009 United Nations climate talks in Copenhagen (Segerberg & Bennett, Citation2011). Social media also has a potential use in dialogic communication of environmental issues, enabling scientists to communicate directly with the public rather than relying on journalists (Lee, VanDyke, & Cummins, Citation2017).

Although most social media platforms tend to be less textually developed and content-rich compared to traditional forms of communication, it is possible to identify frames in social media postings, including in tweets (Twitter postings well-known for their 140 character limit). The ability to hyperlink to other online sources and utilize hashtags (searchable keywords that are hyperlinked to other tweets with the same hashtag) enhances how a Twitter user can frame their message. Framing refers to making selected aspects of a perceived reality more salient in order to “promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman, Citation1993, p. 52). Although a frame may not perform all of these functions (defining a problem, diagnosing causes, making moral judgments, and suggesting solutions), a text that performs just one of these actions is increasing the salience of a selected piece of information (Entman, Citation1993). Framing, therefore, is a central concept to the field of communication because it helps researchers understand the influence of a communicating text (Entman, Citation1993). The effect of a frame can vary because it depends on how a receiver interprets a communicator’s text. But for many frames a “dominant meaning” can be discerned—that with the highest probability of being noticed by most people (Entman, Citation1993). Framing analysis can take a number of methodological approaches including, for example, developing a framing schema and then systematically and quantitatively applying (i.e. coding) that schema to some texts of interest (Kitzinger, Citation2007). Other approaches, however, are more of a qualitative rhetorical or discourse analysis (Kuypers, Citation2010).

Several studies have examined the framing of CC related messages on Twitter. An analysis of tweets in response to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fifth Assessment ReportFootnote1 found that the most common frame used was “Settled Science,” which acknowledges the scientific consensus on CC and focuses on the validity of scientific findings (O’Neill, Williams, Kurz, Wiersma, & Boykoff, Citation2015). This contrasts with print media coverage, for which the dominant frame in response to the IPCC report was “Political or Ideological Struggle,” which focuses on policies and other strategies to address CC and the conflicts surrounding those strategies (O’Neill et al., Citation2015). A study of geographic differences in CC frames on Twitter found that “hoax” frames (asserting that CC is not real) are more prevalent in the U.S. compared to the U.K., Australia, and Canada and in “red” states versus “blue” states (Jang & Hart, Citation2015). Other frames identified were “real” (asserting that CC is really happening), “cause” (discussing the causes of CC, including human activities), “impact” (emphasizing effects of CC), and “action” (messages about policies and other actions to combat CC), which was the most common of the five frames (Jang & Hart, Citation2015). Collectively, these framing analyses indicate that there is a high degree of frame contestation in CC Twitter dialogue—that is, one or a few frames dominating the discourse among multiple competing frames—as opposed to frame parity, where all frames are equally prevalent (Entman, Citation2003). Broadly speaking, frame contestation tends to be the norm, at least in the news media (Entman, Citation2003).

Studies of online communication of CC have also examined how users engage with traditional versus new media in their messages. An analysis of the “media ecology” of 60,000 CC tweets found that mainstream media comprised the majority of URLs shared and that there was a lack of source diversity (Veltri & Atanasova, Citation2015). Similarly, tweets in response to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report primarily cited mainstream media sources, although new media sources such as blogs and science news websites comprised over 40% of the URLs (Newman, Citation2016). On the other hand, tweets with hashtags related to two CC protests mostly contained links to “middle media” sources (e.g. alternative news media, NGOs, climate information sites) rather than mainstream media (Segerberg & Bennett, Citation2011).

2. Established vs. emerging issues: Climate change and ocean acidification

The way that individuals engage with, process information about, and ultimately make sense of a particular issue is affected by their level of familiarity with the topic (Marcu, Uzzell, & Barnett, Citation2011; Moscovici, Citation2000). We define a particular topic as “established” if there is high public awareness of the issue and if individuals have—to borrow from terminology used in the Risk Information Seeking and Processing theory (RISP)—a high perceived level of information sufficiency regarding the topic (Griffin, Dunwoody, & Neuwirth, Citation1999). In contrast, an “emerging” issue has low awareness and high unfamiliarity among the public, which corresponds to lower levels of information sufficiency when individuals are confronted with the issue. According to the RISP model, information sufficiency is the amount of information people believe they need to deal with a given risk, and it is a key factor that influences information seeking intentions and behaviors (Griffin et al., Citation1999). The RISP theory could be broadened beyond information seeking intentions about risks to posit that the way individuals seek information about, engage with, and communicate about a specific issue will depend on one’s awareness and information sufficiency regarding the issue. Therefore, it could be posited that people may process information and communicate about established and emerging issues in different ways.

When comparing communication of established and emerging issues, it is important to note that low awareness and low information sufficiency do not necessarily mean that people do not have opinions about emerging issues. For example, although polling data indicate that Americans know little to nothing about nanotechnology, they nevertheless form opinions on the topic that appear to be shaped by their value systems (such as religious beliefs) and heuristic cues (such as media representations) (Runge et al., Citation2013). Experimental work suggests that the ideological context in which individuals encounter an unfamiliar topic influences their willingness to seek information about the topic from countervailing sources (Yeo, Xenos, Brossard, & Scheufele, Citation2015). Specifically, people exposed to information without clear ideological cues on the unfamiliar topic of nanotechnology were more likely to seek further information only from sources consistent with their ideological value predispositions (Yeo et al., Citation2015). For established issues, on the other hand, people already have ideological frameworks in place that help them process new information about the issue (Yeo et al., Citation2015), and thus the context of the new information is not as influential.

Regarding our study topics, CC is clearly an established issue, at least in the developed world where CC awareness is over 90% (Lee, Markowitz, Howe, Ko, & Leiserowitz, Citation2015). In contrast, public awareness of OA in the U.S. and Europe is very low (Capstick et al., Citation2016; Gelcich et al., Citation2014; The Ocean Project, Citation2012) despite scientists’ views that this problem is just as critical as CC and despite the fact that, like CC, OA is caused by excessive anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Consistent with the topic’s low public awareness, OA receives much less coverage in the mainstream and social media compared to CC. To illustrate, a search of the ProQuest database on 18 July 2018 of the terms “climate change” or “global warming” yielded over 2.6 million results within non-scholarly media sources (e.g. newspapers, magazines, wire feeds, blogs, podcasts, websites), whereas a search of “ocean acidification” within the same sources yielded just over 15,000 results. One consequence of CC’s prevalence in the popular media is that media use plays an important role on people’s information sufficiency on CC (Ho, Detenber, Rosenthal, & Lee, Citation2014).

3. U.S. Paris Agreement withdrawal announcement and political polarization in Twitter

It has been argued that science communication is equivalent to political communication, especially on polarizing topics such as CC, and thus it is important to understand the political context in which communication of scientific topics takes place (Scheufele, Citation2014). This is particularly true for communication on Twitter because it is a platform where politically segregated communication networks may form (Conover et al., Citation2011; Gruzd & Roy, Citation2014). Furthermore, Twitter is a powerful medium for real-time discourse on global events (Becker, Naaman, & Gravano, Citation2011) and is a useful tool for gatewatching: monitoring newsworthy organizations for items of interest to a user who selects and disseminates (and may comment on) the chosen information (Bruns, Highfield, & Lind, Citation2012).

Since the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, his administration’s approach toward science and environmental issues has proved to be a critical turning point for many of these issues. This may be best exemplified by Trump’s decision concerning the 2015 Paris Agreement, which is a non-binding agreement signed by 195 nations. The agreement centers on carbon emissions reductions within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Citation2017). It is also known as COP21 because it was developed at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which—with 179 nations represented—was one of the largest gatherings of world leaders in recent history (World Economic Forum, Citation2016). Each country that signed and later ratified the agreement has pledged to reduce their carbon emissions by amounts that the country specified. The U.S., which is the global leader in per capita carbon emissions, agreed (under the Obama administration) to reduce their emissions 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2025 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Citation2016).

During his candidacy in 2016, Trump declared his intentions to withdraw from the Paris Agreement if elected (McGrath, Citation2016), but there was disagreement on this issue among some of his advisors in the early months of his presidency (Davenport, Citation2017). Furthermore, even some energy industry leaders argued that remaining in the agreement would be best for U.S. energy interests (Volcovici, Citation2017). However, on 1 June 2017, Trump formally announced his decision to withdraw the U.S. from the agreement. The announcement sparked responses worldwide in traditional and social media outlets, including Twitter (Jain, Citation2017). This global political event is a driving force to discuss CC support and could potentially translate into thinking more about closely related but lesser known issues such as OA, for which the Paris Agreement has critical implications (Magnan et al., Citation2016). More importantly, this political event could further politicize the discourse of CC, especially on Twitter where CC discussions are already segmented (Williams et al., Citation2015). In other words, regarding frames on Twitter, the Paris Agreement announcement could result in frame changing, which is the tendency of frames used in news coverage of a momentous issue to change over time, resulting in different aspects of the issue being emphasized at different points in time (Houston, Pfefferbaum, & Rosenholtz, Citation2012). The present study, therefore, examines Twitter discussions on CC and OA before and after the Paris Agreement withdrawal announcement in an effort to identify effects of this political event.

4. Hypotheses and research questions

Given that CC is more established and politically contested than OA, it is reasonable to expect that CC tweets receive more attention from the public and their contents and argument tones tend to be more diverse and abundant compared to OA tweets. Also, a wide range of different media sources often discusses CC, while we predict that more narrowly focused science and environmental news outlets discuss OA. We assume that this applies to Twitter, hypothesizing that CC tweets will include links from more diverse media sources, including mainstream media, than OA tweets. Moreover, we want to examine if CC Twitter users would differ from users who tweet about OA regarding their professional background and the level of involvement in the issue. Because OA is a lesser-known issue relative to CC, we assume that more involved issue publics and/or experts such as scientists or environmental journalists will tweet about OA more than the general publics (Lotan, Graeff, Ananny, Gaffney, & Pearce, Citation2011; Vis, Faulkner, Parry, Manyukhina, & Evans, Citation2013). The main content characteristics (e.g. content frames, additional external links) of CC and OA tweets are, therefore, examined under H1, and the main user characteristics (e.g. topical influencers, user types) of CC and OA tweets are explored under H2.

H1: CC tweets will encompass (a) a greater diversity of content frames and (b) more mainstream external media sources, compared to OA tweets.

H2: CC Twitter (a) users as well as (b) topical influencers will exhibit a greater diversity of user characteristics, compared to OA users, which will likely be more experts.

Further, as the core investigative focus of this study, we explore potential changes in different characteristics of CC and OA tweets before and after Trump’s announcement of leaving the Paris Agreement. We also examine if CC and OA Twitter users would mention the Paris Agreement withdrawal announcement and if so, their positions on it. Therefore, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ1: What CC and OA content characteristics are prevalent before and after President Trump’s withdrawal announcement?

RQ2: What CC and OA user characteristics are prevalent before and after President Trump’s withdrawal announcement?

RQ3: Will CC and OA Twitter users form different attitudes (e.g. supportive, neutral, oppose, no mention) concerning support of the Paris Agreement before and after President Trump’s withdrawal announcement?

5. Methods

5.1. Data collection

Relevant tweets were collected over six weeks in May and June of 2017 (5/7/2017–6/15/2017) using DiscoverText, which is online text analytical software that retrieves Twitter data through Application Programming Interface (API)-based search (Shulman, Citation2011). The time window was chosen to capture communication patterns of the public on CC and OA and their reactions to Trump’s decision on the Paris Agreement withdrawal on 1 June 2017. Hashtags #climatechange and/or #globalwarming were used for identifying CC tweets and a hashtag #oceanacidification was used to search for OA tweets.

A total of 221,668 CC tweets and 1,104 OA tweets were collected. To prepare the data for further analysis, all of the retweets (tweets with RT in the beginning of text) and exact duplicates were deleted. When deleting duplicates, we kept one tweet with the highest influence score (follower/following ratio) among all the duplicates. After deletion, 71,098 CC tweets (20,441 tweets before Paris Agreement withdrawal and 50,657 after the withdrawal) and 359 OA tweets (251 before Paris Agreement withdrawal and 108 after the withdrawal) remained.

Because there was huge discrepancy in tweet volume for CC and OA topics, we chose a random sampling approach. To have an equal number of tweets in each coding category (100 each for before and after Trump’s announcement for CC and OA), 400 tweets were randomly selected for further coding and analysis. Previous literature has used random selection of subsets (e.g. Segerberg & Bennett, Citation2011; Veltri & Atanasova, Citation2015) or used purposive sampling such as influence rating (O’Neill et al., Citation2015) or retweet frequency (e.g. So et al., Citation2016) as a systematic way to choose sub-tweets. It was essential for this study to employ the random selection method since we were particularly interested in how the general public—not influencers or opinion leaders on the issues—would communicate and discuss CC and OA in Twitter. After excluding irrelevant and deleted accounts at the time of coding, a final sample of 396 tweets (n = 198 each) was included in the analyses. Although the final sample size seems relatively small, random sampling ensures a fair comparison of content and user characteristics of CC and OA tweets. This analysis, therefore, offers an exploratory “snapshot” of OA and CC Twitter dialogue and may be considered a case study that provides good insights into how a key event can shape the framing of established and emerging issues.

5.2. Coding procedures, categories, and reliability

The unit of analysis was each tweet. Metadata such as the date of creation; username; user description; number of followers, following (friends), and likes; and hashtag(s) were collected along with the number of retweets and tweet contents.

In terms of coding categories, content frames were adopted and updated from a study that examined framing in media responses to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report on CC (O’Neill et al., Citation2015). Table describes the frames in greater detail with examples. If included, external media sources (none, science news, mainstream media, new media, social media, government reports/academic articles, advocacy, images like cartoons, videos, or others)Footnote2 of CC and OA tweets were also coded. User characteristics were adapted from Hopke and Simis (Citation2017) and were coded into either the public, for profit business/industry, government agency/official, non-profit/foundation/advocacy, politician, celebrity, academic/scientist, journalist/media, individual activist, or unclear/don’t know. As for topical influencers for both CC and OA, an influence score of each user’s follower/following ratio was used to examine their characteristics. This score calculation method was adopted from previous studies (e.g. Anger & Kittl, Citation2011), as detailed in the Data Analysis section below. Finally, Paris Agreement support (pro-Paris, neutral, anti-Paris) was coded.

Table 1. Content frame descriptions and example tweets

Two coders discussed the meaning of each coding category and coded 10% of all chosen tweets. The initial intercoder reliability for content frame and user characteristics was somewhat low, so another round of in-depth discussions was performed. Approximately 8 h of in-person training, with detailed instructions, were devoted to reduce any discrepancies between the coders. The final intercoder reliability was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa. For CC tweets, content frame score was 0.97, user characteristics score was 0.90, and external media sources score was 1. For OA tweets, content frame score was 0.89, user characteristics score was 1, and external media sources score was 0.82. Any Kappa scores higher than 0.6 were considered good while scores above 0.75 were considered excellent (Bakeman, Citation2000).

5.3. Data analysis

This study used a content analysis of social media messages to investigate communication patterns of one established but contentious issue, CC, and one novel issue, OA. Comparisons were made before and after Trump’s announcement of leaving the Paris Agreement to examine potential changes in different content and user characteristics of CC and OA tweets.

SPSS version 24.0 was used for data analysis. A series of crosstab analyses were run, along with frequencies and descriptive statistics to test the proposed hypotheses and research questions. As for the topical influence score calculation, the follower/following ratio was chosen among different user performance indicators. The ratio enables a comparison of how many individuals have signed up to receive updates from User A with how many others User A has been following. The higher the ratio, the more individuals are attentive to User A’s Twitter updates, without having to subscribe to their updates first (Anger & Kittl, Citation2011). Although it is ideal if this ratio is considered with interaction ratios (e.g. the amount of retweets, mentions), the follower/following ratio still offers insights into the total amount of followers as well as the level of interest from others in a user.

Last, to offer more quantitative support, the diversity of frames and user characteristics of CC and OA tweets overall (H1a and H2a) and before and after the Paris announcement (RQ1 and RQ2) were measured by calculating the Shannon Diversity Index (H), a common metric of species diversity used in ecology. As a metric of frame parity, the Shannon Equitability Index (EH) was also calculated, which ranges from 0 (complete dominance of a single frame) to 1 (all frames used equally). EH is the ratio of H (the observed diversity in a sample of n species or content frames) to Hmax (the maximum possible diversity, which occurs when all n species or content frames are equally abundant).

6. Results

6.1. H1: Content characteristics

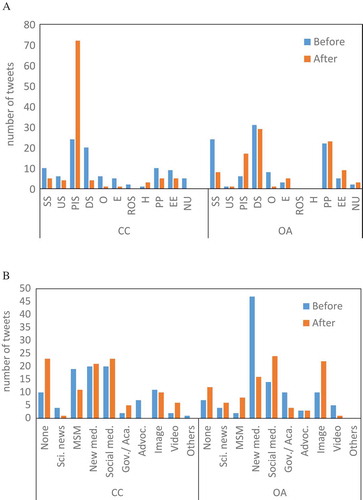

Results for H1a are presented in Table , which shows numbers and percentages of tweets using the different content frames. For CC tweets, Political/Ideological Struggles/Activism (PIS) was the most dominant frame, followed by Disaster/Security (DS) frame. For OA tweets, interestingly, different patterns emerged: DS was the most dominant frame, followed by Promotional/Piggybacking (PP) and Settled Science (SS). Overall, differences between CC and OA frames were statistically significant (χ2 (10, 396) = 93.23, p < 0.001). The given percentages indicate that CC tweets were more narrowly concentrated on just two frames (PIS and DS) than the OA ones. The diversity indices (H) of 1.78 for CC and 1.84 for OA frames support this interpretation.

Table 2. Frequencies and percentages of CC and OA tweets by content frame

The analyses also revealed that around 83% of CC and 90% OA tweets had external media links. Among them, CC tweets contained 21.9% social media links, followed by 20.9% new media, and 15.3% mainstream media links. OA tweets showed different patterns, such that 31.8% had new media external links, which included online-only media, 19.2% linked to social media, and 16.2% linked to external images or photos. Only around 5% of the OA tweets had mainstream media links. The differences between CC and OA tweet external media sources were statistically significant (χ2 (9, 394) = 26.37, p < 0.01). See Table for further details on H1b results.

Table 3. Frequencies and percentages of CC and OA tweets by external URL media sources

6.2. H2: User characteristics

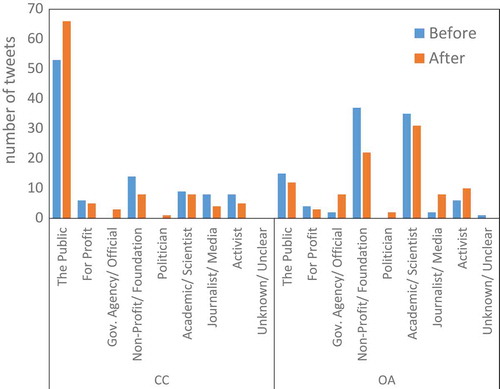

For H2a, crosstab analyses revealed that 60.1% of CC Twitter users were individual users (the public), followed by around 11% non-profit and 8.6% academics/scientists. For OA users, around 33% were academics/scientists, 29.8% were non-profit/advocacy/foundation, and 13.6% were individual users (the public). OA users were more diverse than CC users in terms of user type (H = 1.69 for OA and H = 1.36 for CC) and the differences between CC and OA users were statistically significant (χ2 (8, 396) = 110.29, p < 0.001). See Table for details.

Table 4. Frequencies and percentages of CC and OA Twitter users by user characteristic

For H2b, top 10 topical influencers for both CC and OA topics were explored by calculating an influence score of each user using the follower/following ratio (Anger & Kittl, Citation2011). For CC tweets, three of the top influencers were academics/scientists and two of them were individual journalists/the media, with an H of 1.70. For OA tweets, five of them were non-profit/advocacy/foundations and two were government officials/agencies, with an H of 1.36. Although the CC users were more diverse than the OA users, there were more academic/scientist influencers among the CC users. Therefore, H2b was partially supported. See Table for details.

Table 5. Top 10 topical influencers on CC and OA by follower/following ratio

6.3. RQ1—RQ3: Trump’s Paris agreement withdrawal impact on tweeting patterns

For RQ1, the most prevalent content frame of CC tweets for both before (24 out of 98; 24.5%) and after (72 out of 100; 72%) the Paris Agreement announcement was PIS. After the announcement, however, the frequency of the PIS frame almost tripled, which was reflected in a decline in H from 2.13 to 1.14 and a decline in EH from 0.89 to 0.52. In contrast, the diversity and parity of frames used in OA tweets changed very little after the announcement (H = 1.77 and EH = 0.81 before; H = 1.80 and EH = 0.82 after). The DS frame was the most prevalent among OA tweets both before (31 out of 102; 30.4%) and after (29 out of 96; 30.2%) the announcement. Also, SS-framed OA tweets decreased from 23.5% (24 out of 102) before the announcement to 8.3% (8 out of 96) after, and PIS tweets increased from 5.9% (6 out of 102) to 16.7% (17 out of 96). Overall, the content frame differences between before and after the announcement for CC tweets were statistically significant (χ2 (10, 198) = 53.77, p < 0.001), as well as for OA tweets (χ2 (8, 198) = 20.47, p < 0.01). For external media sources, there were statistically significant differences between time for CC (χ2 (9, 196) = 20.55, p < 0.05) and OA tweets (χ2 (8, 198) = 32.79, p < 0.001). For instance, CC tweets with no external links increased after the announcement (23 out of 100; 23%) compared to before (10 out of 96; 10.4%), and there were no advocacy-related external links after the announcement, compared to 7.3% before. For OA tweets, there were more mainstream media links after the announcement (8 out of 96; 8.3%), compared to before (2 out of 102; 2%), and there were more links to other social media postings after the decision (24 out of 96; 25%) than before (14 out of 102; 13.7%).

For RQ2, there were no statistically significant differences between before and after the announcement for CC Twitter users, which were mostly the public. For OA users, however, there were marginally significant differences ((χ2 (8, 198) = 15.57, p < 0.05), such that before the announcement, non-profit/advocacy/foundations (37 out of 102; 36.3%) comprised the plurality of tweeters, whereas after the announcement, academics/scientists (31 out of 96; 32.3%) comprised the plurality of tweeters. The diversity of OA user types also increased from H = 1.51 before the announcement to H = 1.80 after.

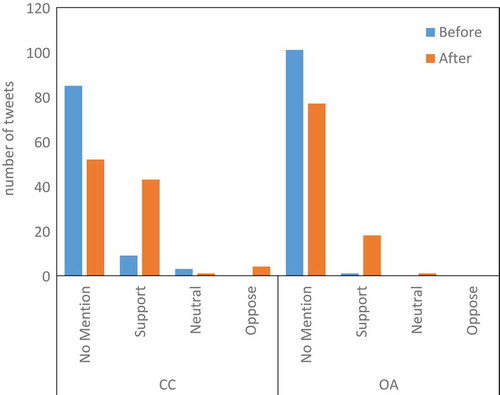

For RQ3, there were significantly more supportive tweets (43 out of 100; 43%) and also opposing tweets (4 out of 100, 4%) of the Paris Agreement among CC users after the announcement, compared to supportive (9 out of 97; 9.3%) and opposing (0 out of 97) tweets before the announcement ((χ2 (3, 197) = 35.14, p < 0.001). For OA users, there were significantly more supportive (18 out of 96; 18.8%) and less no-mention (77 out of 96, 80.2%) tweets after the announcement compared to supportive (1 out of 102; 1%) and no-mention (101 out of 102; 99%) tweets before the announcement ((χ2 (2, 198) = 19.28, p < 0.001). Please see Figures – for visualization of these findings.

Figure 1. Frames (A) and external URL media source type (B) of CC and OA tweets posted before and after President Trump’s Paris agreement withdrawal announcement. Frame codes are identified in Table ; External URL source codes are: Sci. news = Science news, MSM = Mainstream media, Social med. = Social media, Gov./Aca. = Government or academic website, Advoc. = Advocacy media.

7. Discussion

This study investigated how the public discusses significant and timely global environmental issues, CC and OA, on Twitter, specifically with what frames and by whom. In particular, we explored if CC tweets differed from OA tweets, the two being closely related topics with the same cause, in terms of content frame and inclusion of external media links. Specific Twitter user characteristics were also compared. Further, all these characteristics of CC and OA tweets were compared for potential differences before and after President Trump’s announcement on 1 June 2017 of the Paris Climate Agreement withdrawal, a decision that has implications for both CC and OA.

First, regarding content characteristics, PIS was the most dominant frame for CC tweets, whereas DS frame was the most dominant one for OA tweets. This pattern was consistent pre- and post- Trump’s withdrawal announcement, in that CC tweets used PIS frames regardless of timing. However, it was interesting to note that the number of CC tweets using the PIS frame almost tripled after the withdrawal announcement, indicating increased discourse on CC from political and ideological perspectives that likely reflected the controversial nature of President Trump’s political decision. OA tweets using the PIS frame also almost tripled following the announcement, which could suggest that this emerging issue is becoming politicized, but overall, PIS framed tweets only comprised 11.6% of all OA tweets. Instead, the DS frame was the most used among OA tweets, followed by the PP and SS frames. The PP frame occurs when a Twitter user discusses a topic as a means to promote his or her related agenda or events (e.g. professional conference, community workshop, demonstration or protest for a cause) (Fellenor et al., Citation2017). This frame can be used in Twitter as a convenient tactic to facilitate self-promotion and this was the case for OA tweets. DS, which was the most used frame for OA tweets (both pre- and post- Trump’s announcement) typically uses apocalyptic rhetoric, which can lead to labeling the communicators as alarmists and be counterproductive to efforts to promote awareness, concern, and action for the issue (Foust & O’Shannon Murphy, Citation2009). Although this type of frame may be effective to draw individuals’ attention to the issue initially, scientists and other advocates who aim to increase public awareness of OA in an honest and accurate manner should be mindful of using potentially counterproductive frames on Twitter and other types of media due to the possibility of evoking unnecessary fear or worry instead of increasing knowledge on the issue.

For external links, CC tweets had more links containing mainstream media sources than OA tweets, as expected. For both topics, however, social and new media sources comprised the majority of external links. Overall, CC tweets contain slightly more diverse media links than OA tweets, possibly due to its well-known, contested nature. After the Trump announcement, OA tweets’ external media sources also became more diverse and inclusive of social, new, and mainstream media, compared to tweets mainly with new media external links before the announcement.

Regarding user characteristics, CC tweeters were mostly individuals both pre- and post- Trump decision. However, OA tweeters were mostly non-profit, advocacy, and foundations before the announcement, but were mostly academics and scientists after the announcement, with an increase in the diversity of user types after the announcement. Further, academics such as university professors or research scientists, as well as the media were topical influencers for CC, whereas 70% of the top 10 topical influencers for OA were non-profits, advocacy groups, foundations, and government agencies/officials. This was reflected in the relatively low diversity score for OA topical influencers compared to CC influencers. As hypothesized in H2, we did indeed find that relatively few public users tweet about OA, especially compared to CC, but specialized advocacy groups, rather than scientists, were the main OA influencers. Such issue publics or engaged groups likely have a mission to promote outreach and awareness on OA and may draw followers who are interested in broader ocean or environmental issues, not just OA, by disseminating information and promoting relevant activities.

Last, the Trump withdrawal announcement on 1 June 2017 appeared to make public opinion of the Paris Agreement more polarized: there was more support of as well as opposition to the Paris Agreement among CC tweeters after the announcement than before. For OA users, there was more support and more mention of the Paris Agreement after the withdrawal announcement compared to before. The response to this international political event on social media supports the notion of environmental communication as political communication (Scheufele, Citation2014), and these findings may suggest that as OA becomes more well-known, it could become a politically contentious issue, like CC.

Broadly, our findings suggest that individuals differ in the ways they communicate about established versus emerging issues on social media. The overall higher frame parity among OA tweets compared to CC tweets suggests that emerging issues may not be well known or salient enough for a particular frame (or few frames) to dominate the discourse. Additionally, the prevalence of the PIS frame in tweeting about CC suggests that ideology and its connection to activism are influential in shaping how people perceive and communicate about established contested issues, and Twitter, as one of the popular social media platforms, may be a good place to engage in or promote such conversations on established yet contested issues. On the other hand, the relatively lower frequency of the PIS frame among OA tweets suggests that people may be less likely or not yet equipped with knowledge to view emerging issues through an ideological lens. This is consistent with research showing the importance of ideological cues in how the public seeks further information on the emerging issue of nanotechnology (Yeo et al., Citation2015). The increase in polarized discourse of CC following Trump’s withdrawal announcement lends further support to the role of ideology in shaping discourse on established and emerging issues.

Our findings also provide insights into the effect of momentous news events on frame changing and frame parity on Twitter. Both topics experienced frame changing after the Paris withdrawal announcement that can largely be attributed to the increase in PIS frame dominance. This decrease in frame parity was much greater for CC tweets than for OA tweets, which is perhaps unsurprising given that CC is the core issue of the Paris Agreement. But the agreement also has important implications for OA (Magnan et al., Citation2016), a fact that appeared to be recognized by some OA tweeters, as there was an increase in OA tweets mentioning (and supporting) the agreement after the withdrawal announcement. But the finding of greater frame changing among the established issue of CC suggests that momentous news events may not be as influential on the framing of emerging issues on Twitter, even when the news event is highly relevant to the issue.

Although this study produced informative data on CC and OA social media interactions and framing, the study has some limitations. First, we examined tweets from 7 May to 15 June 2017, a six-week data collection period that enabled us to capture opinions closely preceding and following the Paris Agreement announcement. Although six weeks is not a short time frame, a longer time period could have allowed us to study if (and how) the tweeting patterns of CC and OA change both in the short term and in the long term. This event will be covered in the media over the next few years, as the U.S. cannot formally withdraw from the Paris Agreement until 2020 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Citation2017). This will give scholars ample opportunities to build upon our findings and further explore frame changing, especially if the Paris Agreement decision experiences Downs’ classic “issue-attention cycle,” in which an emerging issue initially receives high public attention that then wanes in salience over time (Downs, Citation1972). Second, although the follower/following ratio used in this study can capture the popularity and connectivity of a Twitter user, previous research (Anger & Kittl, Citation2011; Cha, Haddadi, Benevenuto, & Gummadi, Citation2010) suggests that this influence metric needs to be examined along with retweets and/or mentions—other metrics that are more content- and name-value driven—to accurately reflect other aspects of influence on Twitter such as active audience engagement. A third limitation is that our sample size was somewhat small, especially given the noisy and variable nature of Twitter data. Related to this is the fact that because CC tweets greatly outnumbered OA tweets, the randomly selected sample for OA tweets comprised a larger proportion of the total population of tweets than for CC, an issue that can be addressed in future studies using more robust statistical tools. Also, relevant tweets may have been missed because some Twitter users could have discussed CC and OA but with other hashtags not used in this study such as #climatedenial, #ParisAgreement, or #savetheocean to express their concerns on the same issues. Future research could use advanced computational methods such as machine learning technique to analyze a greater number of relevant tweets with a range of different hashtags, so that the complex nature and more nuanced patterns of CC and OA dialogue on Twitter can be understood.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide timely and important exploratory findings as well as theoretical and practical insights into the understanding of these environmental communications in Twitter, one of the most used social media platforms (Statista, Citation2017). Specifically, by investigating relevant frames of CC and OA tweets based on Entman (Citation1993, Citation2003)’s and O’Neill et al. (Citation2015)’s framing approach, the study can contribute to confirming and expanding the explanatory power of framing theory to the understanding of social media messages. PIS and DS frames were used the most to either put a political spin on the public understanding of CC or increase fear or worry associated with the issue to facilitate or discourage action. A fair amount of PP frames encouraging attendance for educational workshops or conferences was found for OA tweets. Understanding which frames are popular and prevalent for each issue in social media platforms such as Twitter can be essential for those who want to strategically use interactive media to further improve public awareness and seek support for these important environmental issues. Based on our results, with a careful understanding of different levels of issue familiarity among its publics, social media can be a potentially effective communication vehicle for disseminating information and opinion on both well-established and lesser-known, emerging environmental issues, complementing traditional and mainstream media outlets.

Negative consequences of CC and OA have been ongoing and confirmed by scientists and can be detrimental to the individual, societal, and economic health of the U.S. and the world (Cooley & Doney, Citation2009; Doney, Balch, Fabry, & Feely, Citation2009; Monaco Declaration, Citation2008). Since the political decision of Trump’s Paris Agreement withdrawal announcement sparked substantial CC discourse and facilitated social media use to express individuals’ opinions, this study can also provide timely recommendations to scientists, educators, and/or outreach professionals that effective environmental communication is essential but can only be achieved when understanding its complex, versatile nature in the context of current societal and political climates.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sojung Claire Kim

Sojung Claire Kim (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Madison) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at George Mason University. Her research interests broadly lie on intersections of interactive media, health and risk communication, and strategic messaging. Research contexts primarily concern challenging health and environmental issues such as cancer, addiction, and climate change, as well as verbal and nonverbal interplay of doctor-patient communication.

Sandra L. Cooke

Sandra L. Cooke (Ph.D., Lehigh University) is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Science in the Biology Department at High Point University. Primarily trained as an aquatic ecologist, her research interests include the effects of ultraviolet radiation and other stressors in freshwater systems, the ecology of aquatic invasive species, and the communication and public perception of critical issues in environmental science.

Notes

1. The IPCC comprises the work of thousands of scientists from 195 nations. It was established by the United Nations Environmental Program and World Meteorological Organization in 1988 to provide scientific assessments on climate change (IPCC, Citation2017b). Released in 2013, the Fifth Assessment Report is the IPCC’s most recent report that details the scientific, technical, and socio-economic aspects of climate change, including its causes, impacts, and potential solutions (IPCC, Citation2017a).

2. “Science news” refers to the websites of legacy journals such as Nature, legacy science magazines such as Scientific American, and environmental focused news websites such as Climate Central and Grist. “Mainstream media” refer to media outlets such as CNN or The Washington Post, as well as magazines such as The Atlantic or US News. “New media” refers to individual blogs as well as online-only media platforms, such as The Huffington Post or Buzzfeed. “Government/academic” refers to governmental agencies, such as NASA, as well as universities or research institutes. “Advocacy” refers to advocacy-oriented websites, such as Azaaz.org or Reality Drop, as well as environmental advocacy organizations, including Sierra Club.

References

- Anger, I., & Kittl, C. (2011). Measuring influence on Twitter. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Knowledge Technologies, Graz, Austria.

- Bakeman, R. (2000). Behavioral observation and coding. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 138–159). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Becker, H., Naaman, M., & Gravano, L. (2011). Beyond trending topics: Real-world event identification on Twitter. Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 11(2011), 438–441.

- Bruns, A., Highfield, T., & Lind, R. A. (2012). Blogs, Twitter, and breaking news: The produsage of citizen journalism. Produsing Theory in a Digital World: the Intersection of Audiences and Production in Contemporary Theory, 80, 15–32.

- Capstick, S. B., Pidgeon, N. F., Corner, A. J., Spence, E. M., & Pearson, P. N. (2016). Public understanding in Great Britain of ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change, 6(8), 763–767. doi:10.1038/nclimate3005

- Cha, M., Haddadi, H., Benevenuto, F., & Gummadi, P. K. (2010). Measuring user influence in twitter: The million follower fallacy. Icwsm, 10, 10–17.

- Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M. R., Gonçalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on twitter. Icwsm, 133, 89–96.

- Cooley, S. R., & Doney, S. C. (2009). Anticipating ocean acidification’s economic consequences for commercial fisheries. Environmental Research Letters, 4(2), 024007. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/4/2/024007

- Davenport, C. (2017, March 2). Top Trump advisers are split on Paris Agreement on climate change. New York Times, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/02/us/politics/climate-change-trump.html

- Doney, S. C., Balch, W. M., Fabry, V. J., & Feely, R. A. (2009). Ocean acidification: A critical emerging problem for the ocean sciences. Oceanography, 22(4), 16–25. doi:10.5670/oceanog

- Downs, A. (1972). Up and down with ecology: The “issue-attention cycle”. Public Interest, 28, 38–50.

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11. Political Communication, 20(4), 415–432. doi:10.1080/10584600390244176

- Fellenor, J., Barnett, J., Potter, C., Urquhart, J., Mumford, J. D., & Quine, C. P. (2017). The social amplification of risk on Twitter: The case of ash dieback disease in the United Kingdom. Journal of Risk Research, 1–21. doi:10.1080/13669877.2017.1281339

- Foust, C. R., & O’Shannon Murphy, W. (2009). Revealing and reframing apocalyptic tragedy in global warming discourse. Environmental Communication, 3(2), 151–167. doi:10.1080/17524030902916624

- Gelcich, S., Buckley, P., Pinnegar, J. K., Chilvers, J., Lorenzoni, I., Terry, G., … Duarte, C. M. (2014). Public awareness, concerns, and priorities about anthropogenic impacts on marine environments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(42), 15042–15047. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417344111

- Griffin, R. J., Dunwoody, S., & Neuwirth, K. (1999). Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 80(2), S230–S245. doi:10.1006/enrs.1998.3940

- Gruzd, A., & Roy, J. (2014). Investigating political polarization on Twitter: A Canadian perspective. Policy & Internet, 6(1), 28–45. doi:10.1002/1944-2866.POI354

- Ho, S. S., Detenber, B. H., Rosenthal, S., & Lee, E. W. J. (2014). Seeking information about climate change. Science Communication, 36(3), 270–295. doi:10.1177/1075547013520238

- Hopke, J. E., & Simis, M. (2017). Discourse over a contested technology on Twitter: A case study of hydraulic fracturing. Public Understanding of Science, 26(1), 105–120. doi:10.1177/0963662515607725

- Houston, J. B., Pfefferbaum, B., & Rosenholtz, C. E. (2012). Disaster news: Framing and frame changing in coverage of major US natural disasters, 2000–2010. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(4), 606–623. doi:10.1177/1077699012456022

- IPCC. (2017a). IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Activities. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/activities/activities.shtml

- IPCC. (2017b). IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Organization. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/organization/organization.shtml

- Jain, S. (2017, June 2). Twitter heats up after Donald Trump exits Paris climate agreement. Retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/twitter-heats-up-after-donald-trump-exits-paris-climate-agreement-1706926

- Jang, S. M., & Hart, P. S. (2015). Polarized frames on “climate change” and “global warming” across countries and states: Evidence from Twitter big data. Global Environmental Change, 32, 11–17. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.02.010

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kemp, S. (2017). Number of social media users passes 3 billion with no signs of slowing. Retrieved from https://thenextweb.com/contributors/2017/08/07/number-social-media-users-passes-3-billion-no-signs-slowing/

- Kitzinger, J. (2007). Framing and frame analysis. In E. Devereaux (Ed.), Media studies: Key issues and debates (pp. 134–161). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Framing analysis from a rhetorical perspective. In P. D’Angelo & J. A. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 286–311). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lee, N. M., VanDyke, M. S., & Cummins, R. G. (2017). A missed opportunity?: NOAA’s use of social media to communicate climate science. Environmental Communication, 1–10. doi:10.1080/17524032.2017.1308407

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014. doi:10.1038/nclimate2728

- Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., & Pearce, I. (2011). The Arab spring| The revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5, 31.

- Magnan, A. K., Colombier, M., Billé, R., Joos, F., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Pörtner, H.-O., … Gattuso, J.-P. (2016). Implications of the Paris agreement for the ocean. Nature Climate Change, 6(8), 732–735. doi:10.1038/nclimate3038

- Marcu, A., Uzzell, D., & Barnett, J. (2011). Making sense of unfamiliar risks in the countryside: The case of Lyme disease. Health & Place, 17(3), 843–850. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.03.010

- McGrath, M. (2016, May 27). Donald Trump would ‘cancel’ Paris climate deal. BBC News, Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-36401174

- Monaco Declaration. (2008). Second international symposium on the ocean in a high-CO2 world. Monaco, Retrieved from https://www.iaea.org/nael/docrel/MonacoDeclaration.pdf

- Moscovici, S. (2000). Social representations: Explorations in social psychology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Mossler, M. V., Bostrom, A., Kelly, R. P., Crosman, K. M., & Moy, P. (2017). How does framing affect policy support for emissions mitigation? Testing the effects of ocean acidification and other carbon emissions frames. Global Environmental Change, 45, 63–78. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.04.002

- Newman, T. P. (2016). Tracking the release of IPCC AR5 on Twitter: Users, comments, and sources following the release of the working group I summary for policymakers. Public Understanding of Science, 26(7), 815–825. doi:10.1177/0963662516628477

- O’Neill, S., Williams, H. T., Kurz, T., Wiersma, B., & Boykoff, M. (2015). Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC fifth assessment report. Nature Climate Change, 5(4), 380–385. doi:10.1038/nclimate2535

- The Ocean Project. (2012). America and the Ocean: Ocean acidification. Retrieved from http://theoceanproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Special_Report_Summer_2012_Public_Awareness_of_Ocean_Acidification.pdf

- Pearce, W., Holmberg, K., Hellsten, I., & Nerlich, B. (2014). Climate change on Twitter: Topics, communities and conversations about the 2013 IPCC working group 1 report. PloS one, 9(4), e94785. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094785

- Runge, K. K., Yeo, S. K., Cacciatore, M., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., Xenos, M., … Li, N. (2013). Tweeting nano: How public discourses about nanotechnology develop in social media environments. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 15(1), 1381. doi:10.1007/s11051-012-1381-8

- Schäfer, M. S. (2012). Online communication on climate change and climate politics: A literature review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 3(6), 527–543.

- Scheufele, D. A. (2014). Science communication as political communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(Supplement 4), 13585–13592. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317516111

- Schuldt, J. P., McComas, K. A., & Byrne, S. E. (2016). Communicating about ocean health: Theoretical and practical considerations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371(1689), 20150214. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0214

- Segerberg, A., & Bennett, W. L. (2011). Social media and the organization of collective action: Using Twitter to explore the ecologies of two climate change protests. The Communication Review, 14(3), 197–215. doi:10.1080/10714421.2011.597250

- Shulman, S. (2011). DiscoverText: Software training to unlock the power of text. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 12th annual international digital government research conference: Digital government innovation in challenging times., New York, NY, USA.

- So, J., Prestin, A., Lee, L., Wang, Y., Yen, J., & Chou, W.-Y. S. (2016). What do people like to “share” about obesity?: A content analysis of frequent retweets about obesity on Twitter. Health Communication, 31(2), 193–206. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.940675

- Statista. (2017). Number of monthly active Twitter users worldwide from 1st quarter 2010 to 3rd quarter 2017 (in millions). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2016). NDC registry (Interim): United States of America. Retrieved from http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/pages/Party.aspx?party=USA

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2017). The Paris agreement. Retrieved from http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

- Veltri, G. A., & Atanasova, D. (2015). Climate change on Twitter: Content, media ecology and information sharing behaviour. Public Understanding of Science, 26(6), 721–737. doi:10.1177/0963662515613702

- Vis, F., Faulkner, S., Parry, K., Manyukhina, Y., & Evans, L. (2013). Twitpic-ing the riots: Analysing images shared on Twitter during the 2011 UK riots. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt, & C. Puschmann (Eds.), Twitter and Society (pp. 385–398). New York: Peter Lang.

- Volcovici, V. (2017). U.S. coal companies ask Trump to stick with Paris climate deal. Reuters, Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-coal/u-s-coal-companies-ask-trump-to-stick-with-paris-climate-deal-idUSKBN1762YY

- Williams, H. T., McMurray, J. R., Kurz, T., & Lambert, F. H. (2015). Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 32, 126–138. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006

- World Economic Forum. (2016). What is the Paris agreement on climate change? Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/09/what-is-the-paris-agreement-on-climate-change/

- Yates, K. K., Turley, C., Hopkinson, B. M., Todgham, A. E., Cross, J. N., Greening, H., … Johnson, Z. (2015). Transdisciplinary science: A path to understanding the interactions among ocean acidification, ecosystems, and society. Oceanography, 28(2), 212–225. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2015.43

- Yeo, S. K., Xenos, M. A., Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2015). Selecting our own science: How communication contexts and individual traits shape information seeking. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 172–191. doi:10.1177/0002716214557782