?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Church forests provide secured habitat for plants and animals, seed banks for native plants, source of food and medicines, income source and reduce soil erosion. They are threatened by livestock grazing, harvesting of timber and non-timber forest products, conversion to farmlands and the replacement of indigenous trees by economically important tree species. So, this study aimed to estimate households’ willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests using double-bounded contingent valuation method followed by open-ended questions. The study specifically aimed to assess the households’ willingness to pay decision, to elicit households’ willingness to pay in terms of cash and labor and to analyze factors affecting households’ maximum willingness to pay. A total of 300 households was selected using a multistage sampling technique followed by a probability proportional to sample size. The result indicated that the mean willingness to pay of the respondents in cash and labor is 178 ETB and 71.51 man-days per year, respectively. On the other hand, the model result indicated that annual income, social position, membership to mahiber/senbete and size of the land near to church forest had a significant and positive effect on the households’ willingness to pay, whereas dependency ratio had a significant and negative effect. The findings imply that policymakers as well as policies designed at national level should consider annual income, dependency ratio, social position, membership to mahiber/senbete and land size near to church forest variables to design conservation practices for church forests.

Public Interest Statement

In Ethiopia, significant forest patches are found in and around monasteries, graveyards, mosque compounds, churches and other sacred sites. Specially, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church has a long history of planting and protecting trees around churches to keep the forest cover of the church. But the forests are threatened by livestock grazing, harvesting of timber and non-timber forest products, conversion to farmlands and the replacement of indigenous trees by economically important tree species. Consequently, the forests are decreasing both in size and density, with visible losses in biodiversity. This indicates that shadow conservation of church forests is not enough in this era of high deforestation. So, this study assessed the participation of farm households’ in the conservation of their local church forests. This provides information for responsible bodies to take immediate action to stop loss of biodiversity and the forest cover of the church.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Forest covers about 31% of the world’s total land area; 93% of this is natural forest and only 7% planted (FAO, Citation2013). Aerts et al. (Citation2006) and Cardelús et al. (Citation2013) explained that sacred groves are the last remaining fragments of tropical Afromontane Forests.

Sacred groves, also known as church forests, fetish forests and sacred forests, are found in all over the world, including Japan, Morocco, India, Ghana and Ethiopia (Cardelús, Lowman, & Eshete, Citation2012; Cardelús et al., Citation2013; Dudley et al., Citation2010). In Ethiopia, significant forest patches are found in and around monasteries, graveyards, mosque compounds, churches and other sacred sites (FAO, Citation2012). The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has over 40 million followers, 500,000 clergies and 35,000 churches (Alemayehu and Demel, Citation2007; Bongers, Wassie, Sterck, Bekele, & Teketay, Citation2006) and has a long history of planting and protecting trees around churches (Alemayehu and Demel, Citation2007).

Although church forest is a place for worship, burials and mediating religious festivals, they also provide valuable often unique and secured habitat for plants and animals, source of wood for construction of church buildings, food and traditional medicines for monks, shade and conditioned atmosphere for religious festivals, classroom for traditional church school, give grace and esteem to churches, to make ink and dyes, income source, and provide sweet and pleasant smell around churches, conserve water, reduce soil erosion, serve as seed banks for native plants, rich in biodiversity and harbor pollinator species (Alemayehu, Citation2002; Bhagwat, Citation2009; Cardelús et al., Citation2012; Klepeis et al., Citation2016; Reynolds et al., Citation2017). But these sacred groves are threatened by free livestock grazing, harvesting of timber and non-timber forest products, population growth, conversion to farmlands, drought, construction of new churches and the replacement of indigenous trees by economically important tree species; as a result, decreasing deforestation and increasing forest cover is essential to minimize the loss of these forests (Cardelús et al., Citation2013).

It is possible to stop and reverse the threats of the church forest by designing and implementing appropriate conservation practices. The conservation practices include construction of walls around the church forest, hiring permanent forest guards, fencing the forest using local resources (wood and stone), planting new trees, and weeding and watering of young planted trees. This could be done if and only if the households are willing to participate in the conservation practices. The participation could be in terms of cash payment, labor contribution, teaching the community to manage the forest and taking responsibility to stop illegal activities carried out in the forest. As a result, understanding the willingness to pay of the households plays a great role to realize these conservation practices. But almost all of the studies conducted regarding church forests focused on the biological aspects of the forest (Abiyou, Hailu, & Teshome, Citation2015; Alemayehu, Citation2002; Alemayehu and Demel, Citation2007; Alemayehu, Sterck, & Bongers, Citation2010; Alemayehu, Sterck, Teketay, & Bongers, Citation2009; Alemayehu, Teketay, & Powell, Citation2005; Cardelús et al., Citation2012, Citation2013; Cardelus et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, studies regarding social aspect are limited (Amare et al., Citation2016; Klepeis et al., Citation2016; Reynolds et al., Citation2017; Reynolds, Sisay, Shime, Lowman, & Wassie Eshete, Citation2015). Amare et al. (Citation2016) estimated households’ willingness to pay to restore church forests in northwestern Ethiopia using open-ended contingent valuation. But open-ended contingent valuation questions are unlikely to provide the most reliable valuations because responses to open-ended questions are erratic and biased (Arrow et al., Citation1993). Consequently, Arrow et al. (Citation1993) and Hanemann, Loomis, and Kanninen (Citation1991) recommended dichotomous contingent valuation format to assign a monetary value for environmental goods. Additionally, studies about the willingness of households (Amare et al., Citation2016) to participate in church forest conservation practice in terms of cash and labor are almost nil, specific in area coverage, methodology and objective. Particularly, households’ willingness to pay decision and determinants of households’ maximum willingness to pay in terms of cash and labor were not studied. As a result, this study was conducted to estimate the households’ willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests in South Gondar Zone, Ethiopia using double-bounded contingent valuation method (CVM) followed by open-ended questions. This research answers the following questions: are the households willing to pay for the conservation of their local church forest, how much are they willing to pay for the conservation of church forests and what are the factors that influence households’ maximum willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

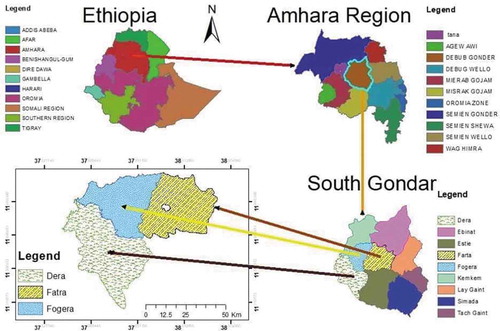

The study was conducted in South Gondar Zone of Amhara region particularly in Fogera, Dera and Farta woreda.Footnote1 Its geographical location is between 11°02ʹ- 12° 33ʹ N and 37°25ʹ-38° 41ʹ E with an altitude range of 1500–4231 m. The annual average rainfall varies between 700 and 1300 mm, with annual average temperature ranging from 9.3°C to 23.7°C (Figure ). South Gondar Zone has an area of about 14,300 km2. The total forest cover is 20,882 ha of which 16,660 ha of natural forest and 4,222 ha of man-made plantations. The forest covers accounting for only 1.4% of the total area of South Gondar Zone of which 50% is attributed to 1404 church forests (Alemayehu and Demel, Citation2007; Alemayehu et al., Citation2010, Citation2005). Depending on this information, South Gondar zone was selected as a study area based on three major reasons: different scholarly kinds of literature reported that the forests are threatened by man-made and natural factors; to fill information gaps of previous studies and different international projects have been attracted by the church forests found in South Gondar zone and the need of conservation practices.

2.2. Sampling technique and sample size

For a quantitative research, the probability sampling technique is appropriate as compared to a non-probability sampling technique because samples drawn by using probability sampling techniques are more representative than non-probability sampling techniques. Accordingly, a multistage random sampling technique was used for this study. In the first step, three woredas, namely: Dera, Fogera and Farta woreda of South Gondar zone were selected. In the second step, five church forests were randomly selected from each woreda. In the third step, sample respondents were stratified based on headship, i.e. male- and female-headed households. In the fourth step, 300 randomly selected households were allocated to the sample woredas, church forests and stratum using probability proportional to sample size. Finally, systematic random sampling was applied to draw sample respondents from each stratum.

2.3. Method of data collection

Quantitative primary data were gathered accompanied by a face to face interview. Focus group discussion and key informant interview were also made as part of data collection method for qualitative primary data. Moreover, secondary data were collected from journals, books and agriculture office of the Dera, Farta and Fogera woreda. Similarly, quantitative data were collected employing semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered in two sections. The first section incorporates demographic, socioeconomic and institutional variables, perception of respondents about the benefits of the forest, and forest rules and enforcement mechanisms. The second section contains contingent valuation scenario and household’s WTP for the conservation of church forests. The questionnaire was translated into the local language (Amharic) to ease the data collection process. Then, well-trained enumerators who have good experience in the survey were employed to gather the data required for this study. The actual survey was conducted between January and April 2017.

Dichotomous choice format CVM studies are preceded by a pretest survey of the small sample population. The discussion by Hoyos and Mariel (Citation2010) indicated that pretest survey with open-ended questions can help to provide some information on the bounds of respondents’ WTP. As a result, the pretest survey was conducted before the actual survey. For this purpose, 15 households were randomly selected for pretest before the actual survey. In addition to the pretest survey, focus group discussion and key informant interview were held to determine initial bids in terms of cash and labor using open-ended contingent valuation format. As a result, 51, 102 and 153 Ethiopian BirrFootnote2 per annum and 24, 48 and 72 man-days per annum followed by open-ended questions were used as a starting bid for the actual survey. After the bids were designed, the respondents were asked a yes/no question to elicit their willingness to pay. If his/her answer was yes, the next higher amount was asked to state their answers. Finally, the respondents were asked their maximum willingness to pay both for the bounded and unbounded values using open-ended questions to state the maximum amount they are willing to pay. If his/her answer was no, the next minimum amount followed by open-ended question was also employed to solicit his/her maximum amount.

2.4. Method of data analysis

2.4.1. Contingent valuation method

CVM is among the stated preference valuation methods and is based on the direct expression of individuals’ willingness to pay or willingness to accept in compensation for any change in environmental quantities, qualities or both (Bogale and Urgessa, Citation2012; Kasaye, Citation2015). CVM asks people to directly state their willingness to pay for non-use values rather than inferring them from observed behaviors in regular marketplaces (Albertini and Cooper, Citation2000). In natural resources, contingent valuation studies generally derive values through the elicitation of respondents’ willingness to pay to prevent injuries to natural resources or to restore injured natural resources (Khalid, Citation2008). In order to elicit more reliable answers from respondents, researchers have developed several different methods of asking evaluative questions, for example, open-ended questions, bidding games, payment cards and dichotomous choice format (Chien, Huang, & Shaw, Citation2005).

Among the formats of CVM, dichotomous choice contingent valuation format (single bounded and double bounded) has gained popularity over the last several years due to their purported advantages in avoiding many of the biases known to be inherent in other formats used in the CVM (Arrow et al., Citation1993; Cameron and Quiggin, Citation1994). The dichotomous choice format involves a binary question for a given price and has been advocated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) panel protocol on CVM studies (Arrow et al., Citation1993).

Among the dichotomous choice formats, double-bounded contingent valuation format has the benefit of higher statistical efficiency than single-bounded contingent valuation format (Cooper, Hanemann, & Signorello, Citation2002; Hanemann and Kanninen, Citation1996; Hanemann et al., Citation1991). In double-bounded contingent valuation, the second price is set on the basis of the subject’s response to the first price. If the subject responds “yes” the first price, the second price is some amount higher than the first price; if the initial response is “no,” the second price is some amount lower (Cameron and Quiggin, Citation1994; Cooper et al., Citation2002; Hanemann and Kanninen, Citation1996; Hoyos and Mariel, Citation2010). Double-bounded CVM is used to identify both the bounded and unbounded willingness to pay of the respondents, but not the exact amount of respondents’ willingness to pay (Hanemann et al., Citation1991). Double-bounded CVM followed by an open-ended question provides strictly more information than a double contingent valuation format (Green, Jacowitz, Kahneman, & McFadden, Citation1998). As Marta-Pedroso, Marques, and Domingos (Citation2012) explained, the follow-up open-ended question is used to state the unbounded willingness to pay of respondents. Depending on the above explanation, this study employed double-bounded CVM followed by open-ended questions.

2.4.2. Statistical analysis

The collected data were fed into SPSS 22.0 and STATA 14 statistical software and analyzed using percentages, frequency, mean and Tobit econometric model. The nature of the dependent variable determines the type of econometric model. Consequently, the objective of this study was to examine the determinants of households’ maximum willingness to pay in the conservation practices of church forest. Double-bounded contingent valuation followed by the open-ended question was used to produce continuous values of the dependent variable, including zeros. So, this dependent variable had zero and non-zero values. According to Wilson and Tisdell (Citation2002), ordinary least square estimates become biased and inefficient depending on the number of zeros in relation to the number of observations in the data set. Following this, Stewart (Citation2013) explained that Tobit has been the predominant approach in more recent studies where some observations in the sample lacked data or had zero values for the dependent variable. This is particularly relevant for willingness to pay data set. Consequently, the Tobit model is the right model for such type of dependent variables. In line with this, the Tobit model was applied to analyze the determinants of households’ maximum willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests. The model is specified following random utility model (Alhassan, Donkoh, & Boateng, Citation2017; Missios and Ferrara, Citation2011; Thurstone, Citation1927; Wooldridge, Citation2002)

where, Y = the maximum willingness to pay in terms of cash and labor,

βi = coefficients of explanatory variables,

Xi = Explanatory variables and

Ui = Error term

The maximum willingness to pay in cash and labor is the dependent variable of the Tobit model. A literature review was undertaken to identify potential explanatory variables on the willingness to pay of the respondents. Based on this, explanatory variables were hypothesized on willingness to pay in cash and labor based on the information gleaned from the theoretical literature review of previous works (Abebe and Geta, Citation2014; Amare et al., Citation2016; Cho, Newman, & Bowker, Citation2005; Kalbali, Borazjani, Kavand, & Soltani, Citation2014; Kasaye, Citation2015; Mekdes, Citation2014; Tang, Nan, & ZandLiu, Citation2013; Zewdu and Yemsirach, Citation2004). The potential variables are listed in Table .

Table 1. Definition and descriptive statistics of socioeconomic and demographic variables

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

Among 300 samples, 284 samples were used for statistical analysis. Sixteen observations were discarded from the analysis due to incomplete observation and discrepancy of the data.

Definition, expected sign and summary statistics of the variables included in the model are presented in Table . The summary statistics was computed for the total observation and compared with willing and not willing respondents. The average age of the respondents was 45 years. This figure was compared with the average age of willing and not willing respondents. The comparison indicated that willing households were younger than not willing households (Table ). Additionally, the result revealed that 86% of the respondents were males of which 76% and 10% of them were willing and not willing to pay for the conservation of church forests. About 57% of the respondents were literate households. Out of 163 literate households, 53% and 5% were willing and not willing to pay for church forest conservation practices. This result entails that literate households were more willing to pay for the conservation of church forests. The average dependency ratio, income and livestock ownership of the respondents were 0.92, 14,767 Birr and 4.51 TLU, respectively. The respondents owned 0.04 ha of land near to the church forests. The average distance from church forest was 25 min. As shown in Table , the home of the willing households were near to the forest as compared to not willing households. Likewise, about 52% of the respondents were credit users, and 97% of the respondents perceived the benefits of the church forests. Among 284 respondents, 50% of them got training about forest/other natural resource conservation. Out of 156 socially positioned respondents, 52% and 4% were willing and not willing to pay for church forest conservation.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church has its own punishment mechanisms to stop illegal activities performed by individuals or group of individuals, i.e. cutting trees from the church forest, collecting firewood, grass and free livestock grazing. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido ratified punsishment mechaniam (50 Birr per cattle) to stop illegal livestock grazing but still there is a gap to effectively apply this and related punishment mechanisms. So, the respondents were asked their perception about the importance of effective punishment in order to protect the forest cover of the church. Finally, 83% of the respondents confirm the role of effective punishment against unusual activities practiced in the church forest. Mahiber/Senbete is a common self-help religious organization established by the interest of the individuals who live in the same village or kebele. About 74% of the respondents were mahiber/senbete members, and 69% and 5% of mahiber/senbete members were willing and not willing to pay. From this, we can conclude that mahiber/senbete members are more willing than non-members.

3.2. Willingness to pay for church forest conservation

As Hanemann and Kanninen (Citation1996) recommended, prior to the elicitation question, individuals were asked if they would pay anything. As a result, yes or no questions were designed to assess the willingness to pay decision of the respondents in terms of cash and labor. The result indicated that 248 (87.3%) of sample respondents were willing to pay cash, labor or both for conservation practices; whereas, 36 (12.7%) of the respondents were not willing to pay anything at all. From willing respondents, 53 (18.7%), 20 (7%) and 175 (61.6%) were willing to pay cash only, labor only and both (cash and labor), respectively, for conservation practices.

As Hoyos and Mariel (Citation2010) explained efficiency in the elicitation of WTP can be increased if repeated questions are used. Following this, double-bounded CVM followed by open-ended question was used for this study. The result of the contingent valuation survey demonstrated that the willingness to pay of sample households ranges from 10 to 550 ETB annually towards conservation activities of church forests. As the figure below indicated, the number of respondents decrease if the bid gets higher and higher (Figure ). The mean and median of their willingness to pay is 178 ETB and 160 ETB, respectively. As the result indicated, the mean of the respondents was higher than the median. This implies that the respondents were willing to pay less than the average WTP.

Figure 2. Willingness to pay curve in terms of cash payment for church forest conservation in the study area.

In addition to the cash payment, labor was used as a payment vehicle to measure the willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests. After the end of the yes-no questions for each stated bid, the maximum contribution of man days for the conservation of church forests was elicited using open-ended questions. The result revealed that the respondents’ willingness to contribute labor ranges from 12 to 180 man-days per year. The mean and median of labor contribution was calculated based on the survey data. The result indicated that the mean and median of their willingness to contribute labor was 71.51 and 72 man-days per year, respectively. This result indicated that the respondents were willing to pay close to the average willingness to contribute labor per year, but the number of respondents decreased when the bid amount gets higher and higher (Figure ).

Figure 3. Willingness to pay curve in terms of labor contribution for church forest conservation in the study area.

Table depicts the joint response of sample households for the first and the next minimum or maximum bids. The result indicated that 135 (47.5%) and 107 (37.7%) of the respondents were willing to pay the maximum amount beyond the stated bids (yes-yes) in cash and labor, respectively. On the other hand, 97 (34.2%) and 96 (33.8%) of the respondents refused to pay both the first and the next minimum bid (no-no) in cash and labor, respectively. A total of 30 (10.6%) and 32 (11.3%) of sample respondents were willing to pay the first offered amount and refused to pay the next maximum amount in cash and labor; on the other hand, 22 (7.7%) and 49 (17.2%) of the respondents refused the first bid but agreed to pay the next minimum bid in cash and labor (Table ).

Table 2. Joint responses to stated bids

3.3. Determinants of maximum willingness to pay

Fourteen explanatory variables were included in the model to predict the maximum willingness to pay of the respondents in cash and labor contribution. The marginal effects of the variables were computed following the Tobit estimation. Table shows the sign, magnitude, statistical tests and significance level of each explanatory variable. Out of the 14 variables hypothesized to influence the maximum willingness to pay of the respondents in terms of cash, 3 variables were statistically significant at less than 1% significant level. These variables are annual income, membership to mahiber/senbete and social position. In addition to factors affecting the amount households’ are willing to pay in terms of cash, this study also analyzed the determinants of the households’ maximum willingness to pay in terms of labor for church forest conservation. The result of the model indicated that membership to mahiber/senbete was significant at less than 1% significant level . On the other hand, social position and size of the land near to the church forest were significant at less than 5% significant level. Conversely, dependency ratio had statistically significant and negative effect on willingness to contribute labor at less than 10% significant level.

Table 3. Result of the Tobit model

4. Discussion

As expected, annual income had a statistically significant and positive effect on the households’ willingness to pay in terms of cash (Table ). This implies that the higher the income of the respondents, the maximum amount they are willing to pay for the conservation of church forests. This also proves that the amount high-income respondents are willing to pay for church forest conservation is expected to be more in comparison to lower income respondents. This is because having more income increases the purchasing power of sample respondents. The result of the model indicates that as the income of the respondents’ increases by one ETB, his/her willingness to pay will increase by 6.25% (Table ). This result is congruent with the findings of previous studies (Abebe and Geta, Citation2014; Cho et al., Citation2005; Mekdes, Citation2014; Tang et al., Citation2013).

As hypothesized, dependency ratio had a statistically significant and negative effect on willingness to pay in terms of labor. The result demonstrated that a large number of dependents within the household decreases the willingness of households to contribute labor for conservation activities because an increase in the number of dependents put pressure on active family members to fulfill their basic needs. In support of the finding, Nigussie, Adisu, Desalegn, and Gebreegziabher (Citation2016) confirmed that households with high dependency ratio might not be able to participate in programs and projects due to time, labor and/or financial constraints. Additionally, Kumar and Srivastava (Citation2017) explained that an increase in dependency ratio increases the number of dependents which leads to shortages of working hands to generate income from diversified activities to fulfill basic needs of household members. The marginal effect of the model indicated that the willingness to pay of the respondents decreases by 10.15% for a unit increase in the number of dependents. This finding is in line with the result of the previous study (Zewdu and Yemsirach, Citation2004).

The social positionFootnote3 of the respondents was hypothesized to have a positive effect on the households’ willingness to pay. As expected, the variable had a statistically significant and positive effect on willingness to pay of respondents. This is due to the fact that the position of the respondents in their society has a vital role in natural resource conservation activities because it is the responsibility of positioned individuals to motivate and order the society to engage in conservation activities. Those individuals have the power to penalize non-participants at the time of conservation activities. This may create the chance for the society to involve in conservation activities. The probability of willingness to pay of sample households’ in cash and labor will be increased by 6.05% and 10.26% if the household head has his/her social position. This result is similar to the findings of a previous study (Gebremariam, Citation2012).

The size of the land near to the church forest had a statistically significant and positive effect on the households’ willingness to pay for the conservation of church forests. This means that the higher the land size owned by the respondents near to the church forest, the more amount they are willing to pay to conserve their local church forests. The reason for this relationship is that church forests provide important benefits to their land, i.e. dead parts of the forest serve as compost for the land, protection of erosion and source of rainfall. This result is consistent with the finding of Amare et al. (Citation2016), who found that people in the local communities who own land are more willing to pay compared to people who do not own land near to the church forest. This indicates that respondents who benefited from church forests are eager to contribute to the conservation of church forests. The probability of willingness to pay increases by 10.03% if the size of the land near to the church forest is increased by one hectare.

The other determinant variable is membership to mahiber/senbete.Footnote4 As expected, the variable had a statistically significant and positive effect on the households’ willingness to pay at less than 1% significant level. The result of the model indicated that the probability of the households’ willingness to pay in cash and labor will be increased by 13.75% and 16.97% if the household head is a member of mahiber/senbete. This implies that the more the numbers of mahiber/senbete members, the more the amount the respondents are willing to pay for the conservation of the church forests. This is because mahiber/senbete members celebrate their ceremony at home or inside the church forest. The main purpose of mahiber/senbete is to get blessing from God. To get this spiritual blessing, they discuss different issues of the church and its surrounding. According to Amare et al. (Citation2016), church forests are given core values as entities for religious and community social service places like mahiber/senbete. His explanation indicates that the members gather together at church so as to pray together, discuss their problems and further share information. This creates awareness for the members to participate in the conservation of church forest.

5. Conclusion

Sacred forests are found all over the world, including Ethiopia. Specially, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church has a long history of planting and protecting trees around churches. The conservation of these church forests has multidimensional benefits. But these patches of natural forest have survived as a result of the traditional conservation (spiritual beliefs, and social rules and norms) effort of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Churches but the involvement of the church only is not sufficient to protect the forest from degradation. In light of this information, this study estimated households’ willingness to pay in terms of cash and labor for the conservation of church forests.

The result of the CVM survey indicated that the willingness to pay of the respondents ranged from 10 to 550 ETB and 12 to 180 man-days per year. The mean willingness to pay in terms of cash and labor is 178 ETB and 71.51 (1787.75 ETB) man-days, respectively. This entails that the cash equivalent of the mean willingness to pay in terms of labor contribution is higher than cash contribution. So, it is better to focus on labor contribution to assess the household’s willingness to pay for the conservation of the church forest.

Tobit model was employed to answer the question “what are the factors that influence households’ maximum willingness to pay for the conservation of church forest.” The result of the model indicated that annual income, social position and membership to mahiber/senbete had a statistically significant and positive effect on households’ willingness to pay in terms of cash. This implies that the above variables increase the willingness to pay of respondents unlike negatively related variables. In addition to social position and membership to mahiber/senbete, the size of the land near to the church forest had significant and positive relationship with willingness to pay in terms of labor days, but dependency ratio had significant and negative relationship with labor contribution.The following core ideas are drawn depending on the findings of this study.

The increment of the annual income of the respondents increases their willingness to pay towards conservation practices of church forests. So, the forest policy of Ethiopia, particularly South Gondar zone should design strategies to diversify income sources of the households so as to realize the conservation of church forests.

Membership to mahiber/senbete and willingness to pay had a significant and positive relationship. This entails that the more the number of individuals who have a mahiber/senbete, the higher the willingness to pay of the respondents. So, it is better to push nonmembers to join mahiber/senbete membership to increase the number of participants in conservation practices. In addition to this, church clubs need to be established, promoted and supported to minimize the threats of the forest. Both governmental and nongovernmental organizations should support mahiber/senbete members by providing training to increase their awareness about church forests.

The size of the land near to the church forest had a significant and positive relationship with willingness to pay in terms of man-days. This indicates that the respondents with the small size of the land near to church forest are less willing to pay for conservation practices. This needs further research to design suitable conservation practices to address this particular issue.

Acknowledgements

First and for most, we would like to thank Colgate University, Bahir Dar University and the Ethiopian Ministry of Education for financial sponsorship of this project. The authors also extend thanks to Dera, Fogera and Farta woreda agriculture office heads and respondents.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Birara Endalew

Birara Endalew joined Agriculture and Environmental Sciences College of Bahir Dar University in 2014 after he holds his bachelor degree in Agricultural Economics from Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine College of Jimma University, Ethiopia. After 1-year work experience, he got in-country scholarship in Bahir Dar University. Now, he holds his master degree in Agricultural Economics on 20 December 2017. He is now engaged in teaching, research and community service. Specially, measurement and modeling of willingness to pay, food security, value chain analysis, livelihood analysis and poverty analysis are the author’s interest area of research.

Beneberu Assefa Wondimagegnhu

Dr. Beneberu is an Assistant Professor and chair for rural livelihoods and sustainable development research at the department of rural development and agricultural extension in Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia.

Notes

1. Woreda is the third level administrative divisions of Ethiopia. It is further subdivided into the smallest unit of local government (Kebele).

2. Ethiopian Birr is a paper money, silver coin and monetary unit equal to 100 cents. $1 = 27.39 ETB.

3. Social position refers to the responsibility of an individual in a given society and culture given by the society, local government or the church.

4. Mahiber/Senbete is a self-help religious organization established by the common interest of members.

References

- Abebe, M. B., & Geta, E. (2014). Farmers willingness to pay for irrigation water use: The case of Agarfa District, Bale Zone, Oromiya National Regional State. Haramaya: Haramaya University.

- Abiyou, T., Hailu, T., & Teshome, S. (2015). The contribution of Ethiopian orthodox Tewahido church in forest management and its best practices to be scaled up in North Shewa Zone of Amhara Region. Ethiopia Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 4, 123–137. doi:10.11648/j.aff.20150403.18

- Aerts, R., Van Overtveld, K., Haile, M., Hermy, M., Deckers, J., & Muys, B. (2006). Species composition and diversity of small Afromontane forest fragments in Northern Ethiopia. Plant Ecology, 187(1), 127–142. doi:10.1007/s11258-006-9137-0

- Albertini, A., & Cooper, J. (2000). Application of contingent valuation method in developing countries. Economic and social development paper (Vol. 146). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/X8955E/x8955e00.htm

- Alemayehu, W., Sterck, F. J., Teketay, D., & Bongers, F. (2009). Effects of livestock exclusion on tree regeneration in church forests of Ethiopia. Forest Ecology and Management, 257(3), 765–772. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.07.032

- Alemayehu, W. E. (2002). Opportunities, constraints and prospects of the Ethiopian orthodox Tewahido churches in conserving forest resources: The case of churches in south Gonder, Northern Ethiopia. Wondo Genet College of Forestry, Ethiopian MSc in Forestry Programme Thesis Report No. 2002:63.

- Alemayehu, W. E., & Demel, T. (2007). Ethiopian church forests: Opportunities and challenges for restoration ( Ph. D. Thesis). Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Alemayehu, W. E., Sterck, F. J., & Bongers, F. (2010). Species and structural diversity of church forests in a fragmented Ethiopian highland landscape. Journal of Vegetation Science, 21(5), 938–948. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2010.01202.x

- Alemayehu, W. E., Teketay, D., & Powell, N. E. I. L. (2005). Church forests in North Gonder administrative zone, northern Ethiopia. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 15(4), 349–373. doi:10.1080/14728028.2005.9752536

- Alhassan, H., Donkoh, S. A., & Boateng, V. F. (2017). Households’ willingness to pay for improved solid waste management in Tamale Metropolitan area, Northern Ghana. UDS International Journal of Development, 3(2), 70–84.

- Amare, D., Mekuria, W., T Wold, T., Belay, B., Teshome, A., Yitaferu, B., & Tegegn, B. (2016). Perception of local community and the willingness to pay to restore church forests: The case of Dera district, northwestern Ethiopia. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 25(3), 173–186. doi:10.1080/14728028.2015.1133330

- Arrow, K., Solow, R., Portney, P. R., Leamer, E. E., Radner, R., & Schuman, H. (1993). Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Federal Register, 58(10), 4601–4614.

- Bhagwat, S. A. (2009). Ecosystem services and sacred natural sites: Reconciling material and non-material values in nature conservation. Environmental Values, 18, 417–427. doi:10.3197/096327109X12532653285731

- Bogale, A., & Urgessa, B. (2012). Households’ willingness to pay for improved rural water service provision: Application of contingent valuation method in Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Human Ecology, 38(2), 145–154. doi:10.1080/09709274.2012.11906483

- Bongers, F., Wassie, A., Sterck, F. J., Bekele, T., & Teketay, D. (2006). Ecological restoration and church forests in northern Ethiopia. Journal of the Drylands, 1(1), 35–44.

- Cameron, T. A., & Quiggin, J. (1994). Estimation using contingent valuation data from a “dichotomous choice with follow-up” questionnaire. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 27(3), 218–234. doi:10.1006/jeem.1994.1035

- Cardelús, C. L., Lowman, M. D., & Eshete, A. W. (2012). Uniting church and science for conservation. Science, 335(6071), 915–916. doi:10.1126/science.335.6071.915

- Cardelús, C. L., Scull, P., Hair, J., Baimas-George, M., Lowman, M. D., & E Alemaheyu, W. (2013). A preliminary assessment of Ethiopian sacred grove status at the landscape and ecosystem scales. Diversity, 5(2), 320–334. doi:10.3390/d5020320

- Cardelus, C. L., Scull, P., Wassie, E., Alemayehu, W., Carrie, L., Klepeis, P., … Orlowska, I. (2017). Shadow conservation and the persistence of sacred church forests in northern Ethiopia. Biotropica, 49(5), 577-760.

- Chien, Y.-L., Huang, C. J., & Shaw, D. (2005). A general model of starting point bias in double-bounded dichotomous contingent valuation surveys. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 50(2), 362–377. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2005.01.002

- Cho, S.-H., Newman, D. H., & Bowker, J. M. (2005). Measuring rural homeowners’ willingness to pay for land conservation easements. Forest Policy and Economics, 7(5), 757–770. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.03.007

- Cooper, J. C., Hanemann, M., & Signorello, G. (2002). One-and-one-half-bound dichotomous choice contingent valuation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(4), 742–750. doi:10.1162/003465302760556549

- Dudley, N., Bhagwat, S., Higgins-Zogib, L., Lassen, B., Verschuuren, B., & Wild, R. (2010). Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. London: Earthscan.

- FAO. (2012). The state of forest genetic resources of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Institute of Biodiversity Conservation.

- FAO. (2013). Global plan of action for the conservation, sustainable use and development of forest genetic resources. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3849e.pdf

- Gebremariam, G. (2012). Households’ willingness to pay for soil conservation practices in Adwa Woreda. Ethiopia: a contingent valuation study.

- Green, D., Jacowitz, K. E., Kahneman, D., & McFadden, D. (1998). Referendum contingent valuation, anchoring, and willingness to pay for public goods. Resource and Energy Economics, 20(2), 85–116. doi:10.1016/S0928-7655(97)00031-6

- Hanemann, W. M., & Kanninen, B. (1996). The statistical analysis of discrete response CV data (Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics Working Paper No. 798). Berkeley: University of California.

- Hanemann, W. M., Loomis, J., & Kanninen, B. (1991). Statistical efficiency of double-bounded dichotomous choice contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(4), 1255–1263. doi:10.2307/1242453

- Hoyos, D., & Mariel, P. (2010). Contingent valuation: Past, present and future. Prague Economic Papers, 4(2010), 329–343. doi:10.18267/j.pep.380

- Kalbali, E., Borazjani, M. A., Kavand, H., & Soltani, S. (2014). Factors affecting the willingness to pay of Ghorogh forest park visitors in Iran. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences, 4(3), 368–373.

- Kasaye, B. (2015). Farmers willingness to pay for improved soil conservation practices on communal lands in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University.

- Khalid, A. R. (2008, March 24–28). Economic valuation of the goods and services of coastal habitats. The Regional Training Workshop, March 24 – 28, 2008. Samut Songkram Province, Thailand.

- Klepeis, P., Orlowska, I. A., Kent, E. F., Cardelús, C., Scull, L., Peter, E., … Woods, C. (2016). Ethiopian Church forests: A hybrid model of protection. Human Ecology, 44(6), 715–730. doi:10.1007/s10745-016-9868-z

- Kumar, D. U., & Srivastava, S. K. (2017). A study on livelihood determinant at farm households of Kumaun Hills. Indian Research Journal of Genetics and Biotechnology, 9(1), 155–116.

- Marta-Pedroso, C., Marques, G. M., & Domingos, T. (2012). Willingness to pay and demand estimation for guaranteed sustainability labelled beef. Retrieved from https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/3779578408974/Marta-Pedroso%20et%20al.%20(2012)%20Willingness%20to%20pay.pdf

- Mekdes, T. (2014). Analysis of visitors willingness to pay for recreational use value of”Menagesha Suba”forest park: Application of contingent valuation method. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University.

- Missios, P., & Ferrara, I. (2011). A cross-country study of waste prevention and recycling. Land Economics, 88(4), 710-744.

- Nigussie, A., Adisu, A., Desalegn, K., & Gebreegziabher, A. (2016). Agricultural extension for enhancing productivity and poverty alleviation in small scale irrigation agriculture for sustainable development in Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 11(3), 171–183. doi:10.5897/AJAR2015.9541

- Reynolds, T., Collins, C. D., Wassie, A., Liang, J., Briggs, W., Lowman, M., & Adamu, E. (2017). Sacred natural sites as mensurative fragmentation experiments in long‐inhabited multifunctional landscapes. Ecography, 40(1), 144–157. doi:10.1111/ecog.02950

- Reynolds, T., Sisay, T., Shime, K., Lowman, M., & Wassie Eshete, A. (2015). Sacred natural sites provide ecological libraries for landscape restoration and institutional models for biodiversity conservation. Policy Brief for the U.N. Global Sustainable Development report.

- Stewart, J. (2013). Tobit or not Tobit? Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 38(3), 263–290.

- Tang, Z., Nan, Z., & ZandLiu, J. (2013). The willingness to pay for irrigation water: A case study in Northwest China. Global Nest Journal, 15(1), 76–84. doi:10.30955/gnj.000903

- Thurstone, L. L. (1927). A law of comparative judgment. Psychological Review, 34(4), 273. doi:10.1037/h0070288

- Wilson, C., & Tisdell, C. A. (2002). OLS and Tobit estimates: When is substitution defensible operationally?. University of Queensland, School of Economics. Economic Theory, Applications and Issues, Working Paper No. 15.

- Wooldridge, J. R. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. London, MA: The MIT Press Cambridge.

- Zewdu, B., & Yemsirach, A. (2004). Willingness to pay for protecting endangered environment: The case of Nechsar National Park. Social Science Research Report. Addis Ababa. Retrieved from https://www.africaportal.org/publications/willingness-to-pay-for-protecting-endangered-environments-the-case-of-nechsar-national-park/