Abstract

The study examines the impact of professional development on the topic of poverty in one high poverty school community located in a small city in southern Ontario, Canada. It considers narrative-based experiences of teachers’ collaborative inquiry on literacy practices after a significant amount of professional development was provided to reinterpret teachers’ stereotypical conceptualizations of students and families living in poverty. Findings illuminate how professional development on poverty and education resulted in the enactment of literacy teaching practices from the vantage point of teachers’ reformed narratives of student poverty, with literacy themes including: global citizenship, inferencing, and social justice literacy.

Public Interest Statement

Poverty has become an international issue in our current world economy. Progressive research on poverty and schools has shown there are other ways, other than standardized testing, to measure success of students: school climate, attitude, beliefs and values of teachers and students’ worth in society, hope and dreams for the future, literacy practices that speak to human relationship and global citizenship. Deficit conceptualizations of students living in poverty is a matter that must be consciously addressed in schools in order to understand what it means to be a citizen in the world. Challenging stereotyping by intervening where deficit-based assumptions are left unchallenged, is one way to begin to offer hope, to believe that poverty is not destiny, and that it must begin with educators’ beliefs, values, and hopes of the same. In fact, it rightfully may be a moral duty to do so in today’s schools.

1. Introduction

1.1. Patrick’s rant: A narrative reveal

Everyday you’re parenting kids, you’re parenting parents. Yesterday I had a run-in, and intentional run-in with a parent … [my student] hadn’t been here for three weeks—I really wanted her to be aware … He has every excuse in the book, and that’s why I really wanted to call her on it yesterday. Apparently he has medical issues, a sleeping disorder—which I think is just a cop-out for her. It gives her an excuse not to bring her kids to school. However, I asked her if she worked, and she said no. I said then your job is to get your kid to school every morning. That’s all. That’s all you have to do. Get him to school on time. That’s the only thing you have to do! She had every excuse in the book why she couldn’t do this, so then I started to get ticked off at her because she would just think of anything to justify what she was doing to her kid. He’s already three years behind and he’s eight years old. He’s functioning at a four or five year old level. What’s going to happen when he’s in grade 8 and later on in high school? He’s going to be so far behind that he’s going to drop out, and that’s the future that you’re providing your son right now, and amazingly she said “Well I know my son doesn’t have much of a future.” I couldn’t believe it. It blew me away, that a mother would say that about her eight year old son.

We may have come across educators, like Patrick, who live in tension between their life as teachers and understanding the lived experiences of students and families that live in contexts unlike their own. The tensions may cause teachers to default to biased notions of what it means to live in poverty. Blaming parents for the condition of their own poverty, or presupposing that a parent is not telling the truth, or that conditions are not what they seem, can all be considered deficit conceptualizations (Dudley-Marling, Citation2007). Many of us have been guilty of incorporating such deficit stereotypes, especially when situations are very complex and problematic. But that is not an excuse for our everyday teaching dilemmas. We need to consider why Patrick feels the way he does as a teacher, his frustration with his student’s parent, how he feels and lives in tension with the mega-narrative (Craig, Citation2003) of school policies (for example, getting students to school on time, needing his student to be in attendance so that he can teach him how to read) vs. the small lived out narrative of the sleeping disorder his student’s parent relays back to him, which Patrick believes is a “cop out.” Patrick’s deficit (i.e. negative) language as evidenced when he remarks, “He has every excuse in the book,” or, “I started to get ticked off at her because she would just think of anything to justify what she was doing to her kid,” illustrates deeply rooted stereotyping and deficit language inherent as a narrative reveal (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2013). That is, by revealing Patrick’s biases, we can begin to work toward understanding the intersecting narratives between how Patrick views his student’s life and how his student’s parent views her son’s life. We wonder if there will be a time that Patrick will come to a narrative revelation (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2013), or awareness of his biases, while living a middle-class notion as a teacher working in a school affected by poverty.

1.2. The problem, question, and purpose of the study

The problem that informs this study is: What can educators do about the stark reality of unequal situations in which children grow up? For educators in our current economic reality, this problem presents a difficult challenge. Milner (Citation2013) explains how deficit ways of thinking become engrained in our everyday living:

[E]ducators may embrace the idea that their own, their parents’, and their students’ success and status have been earned. They may believe that failure emanates solely as a result of making bad decisions … many educators believe that their own success is merited because they have worked hard … and made the right choices and decisions. They have little or no conception of how class and socioeconomic privilege and opportunity manifest. (p. 35)

The research questions which guide this study are: How does professional development on poverty impact literacy practices via school team collaborative inquiry? How does professional development on poverty shape teacher narratives and reformation of mindset? Oftentimes, teachers mistakenly understand and take up curriculum expectations (especially literacy acquisition skills) as middle-class notions (Dudley-Marling, Citation2007; Gorski, Citation2012) of what it means to succeed in school, without particular regard to context, place, social conditions and, most critical, how to deeply understand students’ family living (Pushor & Murphy, Citation2004). Patrick, who lived such tensions, at the intersection of teaching his students how to read, to struggling to make sense of why there was little success, defaulted to biased notions of his students and their parents’ plight of poverty. His preconceived and lived experience of “how to read and be in school” came from a transmission place of curriculum and of middle-class societal rules—all of which vastly contrasted his student’s family experience. This is where the dilemma begins.

The primary purpose of this article is to examine the impact of professional development on the topic of poverty in one high poverty school community located in a small city in southern Ontario, Canada. It considers narrative-based experiences of teachers’ collaborative inquiry on literacy practices after a significant amount of professional development was provided not on how to teach test driven high stakes reading, writing and vocabulary acquisition skills but, rather, how to reinterpret teachers’ own stereotypical conceptualizations of students and families living in poverty.

A school team consisting of five elementary teachers and one administrator were participants in the study. They received a three-day professional development series (PDS) on poverty and schooling spanning over one year. Qualitative research was conducted during the PD series as well as two full day follow-up visits to the school site to investigate the impact of the professional development on literacy teaching practices and collaborative inquiry over a two-year period.

Field text for this article is drawn from a larger research program, the Ontario Poverty Project.Footnote 1 In Ontario, where this research originates, poverty is at an all time high (a detailed discussion of poverty and education in Canada will be taken up in a following sub-section). Zeroing in on one school site, this article presents data not previously reported on, in order to capture poverty and schooling as it relates particularly to literacy practices, narrative reformation of mindset, and collaborative inquiry of one high poverty school community. In this manner, the study seeks to move to the next step, to take action, for teachers like Patrick and for practicing educators, who struggle with understanding what it means to teach literacy in high poverty school contexts and possibly how to begin to disrupt deficit conceptualizations of students and families living in poverty. The study illustrates how professional development on poverty links action to narrative reformation of mindset. Ciuffetelli Parker (Citation2013) explains,

Connelly and Clandinin’s narrative inquiry terms living, telling, retelling, and reliving are useful terms to help describe the process of how teachers can burrow deeply into narratives of experience, as stories are told and retold, in order to make new meaning of their knowledge-in-practice and ultimately to use narratives as a way to help reveal hidden biases, as well as to help make newly formed narrative revelations worthy of further interrogation for future practice [e.g. narrative reformation of mindset and practice] … [N]arrative revelation is excavated through lived and storied experience—the living and the telling. In this living and telling, and with every new retelling, the complexities of poverty and schooling are understood at a deeper level.

1.3. Poverty, education, and professional development informing this Canadian study

The Ontario Poverty ProjectFootnote 2 on poverty and schooling in Ontario (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2012; Ciuffetelli Parker & Flessa, Citation2011) examined successful schools in high poverty areas. “Issues such as school climate, school community connections, and teachers’ collaborative engagement in the process of school change do not appear on any exam. However, they are also ways to measure success” (Ciuffetelli Parker & Flessa, Citation2011, p. 15). That is to say, educators’ voices were added to the conversation about serving students living in poverty; and, schools that were researched were chosen for reasons beyond a limited definition of success that may have been garnered from high standardized test scores. Nonetheless, preconceived notions and assumptions that educators sometimes have about children living in poverty were findings from the earlier research in Ontario schools.

Professional development on the topic of poverty itself, and how poverty is positioned and thought about in our society and in schools, has had great potential for reforming negative stereotyping and deficit conceptualizations about students and families living in poverty. The research shows that it is necessary to understand the more deeply-rooted issues of poverty, and schools need the support to do this (Faltis & Abedi, Citation2013; Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO), Citation2012; Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2012). The bottom line is that it is vital to the well-being and learning success of children that they are not viewed as othered by teachers. Ultimately, educators need to work toward resisting deficit-based conceptualizations of students and their families and avoid derogatory stereotyping of what it means to live in poverty (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2015). This article illuminates how professional development on poverty and education resulted in successful literacy teaching practices from the vantage point of teachers’ reformed narratives of students and families living in poverty with the literacy themes of: global citizenship, inferencing, and social justice literacy. Detailed information on the PDS will be explained in the context/methodology section.

1.4. Child poverty in Canada

Ontario, Canada faces considerable problems of child poverty. Campaign (Citation2000), a respected advocacy group, calculates one in seven children in the province lives in poverty (Campaign, Citation2000, 2013). With deterioration of social assistance benefits, and lack of inflation protection, these statistics will remain and likely continue to grow. Three groups that are vulnerable to such statistics are: new immigrants, single parents, and people with disabilities. Among new immigrants to Canada, poverty has risen 60% over the last 20 years. In Ontario, 47% of children in new immigrant families are considered poor. Likewise, 32% of children in racialized families also are considered poor. These groups, and the statistics associated with them, tell but a small part of the picture of the stark realities of children and their families living in challenging circumstances. Child poverty is complex and requires the attention of policy-makers as well as practitioners if there is any hope to alleviate persistent poverty (Campaign, Citation2000, Citation2013; Nelson, Martin, & Featherstone, Citation2013; People for Education, Citation2013). In Canada, for more than 20 years, there have been many public declarations which have supported the elimination of poverty, in particular child poverty. Despite many promises over the years, the child poverty rate has not improved. Canada’s Campaign 2000 (the year that child poverty was to have been eradicated) provides the latest statistics in its 2012 report card on child and family poverty in Canada, a summary portion of which reads:

Nearly one in seven children lives in poverty because their family lives in poverty. Many youth carry huge debt burdens from pursuing post secondary education while the youth unemployment rate is double the overall rate. Aboriginal people are the fastest growing group in Canada but one in four First Nations children lives in poverty. Immigrants and newcomers face child poverty rates more than 2.5 times higher than the general population. The persistence of poverty even in families with two parents working full time and recent limits on Old Age Security limit families’ prospects of relief from poverty through hard work or Canada’s social safety net. (Campaign, Citation2000, Citation2012, p. 2)

Despite Canada being a very rich nation, it is ranked in 24th place out of 35 OECD industrialized nations when comparing child poverty, and “Campaign 2000 and its partner – UNICEF Canada – believe that poverty is one line that we want our kids to cross” (Campaign, Citation2000, Citation2012, p. 5).

In Canada, forty-five percent of children living below the poverty line have at least one parent working full time, full year, yet the average low-income family lives $7,000 per year below the poverty line. Poverty is statistically defined in the research reported in this study from the low income cut off -LICO- line determined by Statistics Canada. LICOs vary by family size and by community size. This statistic speaks particularly to the notion of persistent poverty and its effect on society and school communities. For example, while the economy has doubled in size in Canada, the incomes of families in the lowest financial categories have remained stagnate, resulting in a wider gap between wealthy and poor families (Campaign, Citation2000, Citation2013). Incomes for the bottom 40% of workers keep falling while incomes for those in the middle have stood still or fallen too. The only significant gains have been made by the wealthiest income earners, a global trend which has seen consistency since the economic crash of 2009. Further reported in a policy brief about poverty in Ontario, Canada:

Every month, 770,000 people in Canada use food banks with 40% of those relying on food banks for children. In Ontario there are over 148,000 children whose families depend on this social service. The gap between low income and high income earners has increased which has led many Ontarians to work longer hours … This seems to be leading to the disappearance of the middle class. (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2012, p. 1)

Eradicating child poverty is complex, filled with the need for political will to formulate actions plans that will work. Our society’s continued notion of a “culture of poverty,” which blames people living in poverty rather than blaming the conditions that create and sustain poverty in Canada and world-wide, is a serious dilemma. This dilemma will be discussed throughout as it relates to this study. For policy-makers as well as teachers and educators in schools, it requires that we begin to push against dominant white middle-class notions of socioeconomic class and stereotyping on what it means to be poor. This can begin within schools.

2. Literature review

Much of the North American literature is US based on socioeconomic class to explain deficit conceptualizations from a societal viewpoint as well as how and why schools still need to strive for equality of education, especially regarding political and practical discourses around the education of low income students (see for example Hooks, Citation2000; Milner, Citation2013). I want to emphasize with this in mind, and further to important US literature cited herein, that the Canadian education system varies widely from the US system of publically funded as well as popular charter schools for example, and how US schools obtain funds for resources, faculty, lunch programs, special programs, etc.

In Canada, all schools are publically funded with many provinces, including Ontario, also funding Roman Catholic schools Kindergarten to Grade 12. There are private schools, but no charter schools. Funding is provided to public schools generally by student ratio and, in high poverty school communities, there may be additional extended funding provisions such as the Learning Opportunities Grant (LOG) for schools based on family income, lone-parent status, and parental education. Canada is a widely diverse country, with a multitude of cultures represented. Toronto, for example, was named the world’s most multicultural city by the United Nations. Yet, a discourse that relies solely on culture, albeit critically important to Canada’s make-up as it pertains to high poverty schools, is not the sole discourse that continues to explain all the problematic dilemmas and deficit ideology of poverty in Canada. In low income schools in Ontario, for example, students are more than twice as likely to be living in lone-parent households and they are four times more likely to be recent immigrants, and five times more likely to be of Aboriginal identity, while 25% of students in low income schools are classified as having special education needs, compared to 13% of those in high income schools (People for Education, Citation2013). Students in high poverty schools are more likely to be identified with language impairment, developmental disability, or behavioral issues. Furthermore, students in low income schools are also less likely to be formally identified, which would otherwise entitle them to services under the Education Act (People for Education, Citation2013). These statistics are troubling, there is no doubt, leaving Canada, like the US and other industrialized countries, with the undeniable conclusion that all children, no matter their living conditions or background, deserve an equal, valuable, and good education.

Milner (Citation2013) timely and recent US analysis of poverty, teaching, and learning, takes into account a solid literature review “to unpack, shed light on, problematize, disrupt, and analyze how systems of oppression, marginalization, racism, inequity, hegemony, and discrimination are pervasively … ingrained in … policies, practices, institutions and systems in education …” (Milner, Citation2013, p. 1).

Milner’s emphasis in his review is closely aligned to the emphasis of this paper, and what he refers as his permeating questions throughout:

But what about the role of schools … in being responsive to the outside-of-school realities that influence students who live in poverty? … In what ways does poverty influence and intersect with teaching and learning opportunities in schools? How can instructional practices be used to respond to the material conditions of those living in poverty? (Milner, Citation2013, p. 6)

Milner’s review is seminal and takes into account US-based literature on: outside of school influences (e.g. poverty); inside of school practices (e.g. literacy, curriculum policy); instructional practices and frameworks that are problematic and/or controversial because they feed into deficit ideology (e.g. blaming/condoning parents for students’ low literacy levels); instructional practices that are hopeful and bend toward reform pedagogy (celebrating family language/culture and the language and literacy customs students and families contribute to the curriculum).

This article examines the realities of poverty from professional development that was received by teachers, and then takes into account inside-of-school practices as recounted by teacher narratives as a result of the impact of professional development on poverty (the outside-of-school influence). In this manner, the data will illuminate how poverty, learning, and teaching are inter-related.

2.1. Disrupting deficit-based frameworks about poverty, language, and literacy

There has been considerable literature on poverty and schooling over the years, much has focused on deficit frameworks of a “culture of poverty” translated to mean that children and families are deficient, such as in their position in the “norm” of society, or attitudes and values, or linguistic aptitude (Hart & Risley, Citation1995; Lewis, Citation1966; Payne, Citation1996). However, in recent years there has been abundant literature that has taken action to disrupt and critique these previous deficit-based frameworks on poverty and education. This disruption first was conceptualized by Valencia (Citation1997) and subsequently taken up in detail by other progressive theorists (Dudley-Marling, Citation2007; Dudley-Marling & Lucas, Citation2009; Gorski, Citation2008, Citation2012; Hooks, Citation2000; Miller, Cho, & Bracey, Citation2005; Milner, Citation2013; Ng & Rury, Citation2006; Osei-Kofi, Citation2005; Yosso, Citation2005). The purpose is not to provide an extensive review of that literature but it is important to highlight particular works which frame where this article is positioned.

In Dudley-Marling (Citation2007) influential article “Return of the deficit,” the author discusses at length how implicating a “deficient” language of people living in poverty has been, “[P]erhaps the most persistent version of blaming the poor for their poverty … as the cause of their academic and vocation failures” (p. 4, online). Citing from as far back as 1776 on to the 60s (Bereiter & Engelmann, Citation1966), 70s (Bernstein, Citation1971) and 90s (Hart & Risley, Citation1995), Dudley-Marling’s claims are substantiated with a detailed sourced explanation of how powerful in particular Hart and Risley’s work was situated within American belief and political rhetoric which “linked differential language practices in professional and welfare families to cultural differences … [theorizing] that children living in poverty learn the vocabulary they need to get along … but not the vocabulary required for success in school” (Dudley-Marling, Citation2007, p. 5, online). The deficit-based research of Hart and Risley dominated enormously politics, media, and supported literacy early intervention programs from a middle class stance, paying little regard to the richness of literacy that students living in poverty could potentially offer. The deficit conceptualizations of children and families living in poverty also paralleled the “hidden rules” argument with, again, a middle-class notion of what it means to be linguistically successful (i.e. that if you work hard enough, you will earn the right to privilege and literacy success because poverty is the fault of weak work habits, not society’s condition). Today, unfortunately, this sort of “culture of poverty” deficit-based workshop continues to be offered to school districts all over North America (including Canada), with such frameworks as Ruby Payne’s work, which dangerously perpetuates the “quick fix” of language and children living in poverty, and deficit models of blaming families living in contexts of poverty and teaching practices which continue that mentality. There continue to be studies and programs that remain focused on literacy teaching practices based on reform initiatives that default to standardized middle-class notions of what it means to be successful, as discussed above. However, a continuance on high stakes language learning in North American high poverty schools (e.g. Eithne, Citation2010; Hart & Risley, Citation1995; Haughey, Snart, & da Costa, Citation2001; Neuman & Celano, Citation2012), or likewise literacy research programs that seek to teach parents about how to educate their children to be literate through projects which border, again, on “blame the parents” phenomenon (e.g. Barone, Citation2011), only continue to disenfranchise children living in poverty while perpetually, if not subconsciously, supporting deficit-based ideologies.

Debunking deficit conceptualizations of people living in poverty is difficult work. This professional development impact study helps to support literacy notions which, instead, advocates from research that “… over the last 40 years has emphasized the richness and complexity of language used by poor children and adults from theorists that, like Dudley-Marling, Gorksi, and Milner, continue to take up the difficult dialog in order to debunk deficit conceptualizations (e.g. Goodwin, Citation1990; Heath, Citation1983; Jackson & Roberts, Citation2001; Labov, Citation1972; Michaels, Citation1981)” (Dudley-Marling, and with citations, Citation2007, p. 6, online).

This article, therefore, supports progressive literacy advancements that seek to disrupt the tradition of the deficit (Gee, Citation2004; Miller et al., Citation2005). It considers narrative-based experiences of teachers in a high poverty school community and how they began anew to inquire further into their own literacy practices to better understand the contexts in which students live, how they learn, and what their families contribute to literacy and schooling.

3. Context and methodology

Teacher narratives of reformed mindset and practices from a PDS, entitled Possibilities: Poverty and Education Series, on the topic of poverty are illustrated using qualitative narrative methods. Research text is derived from reviewing and analyzing field notes, conversations, and interviews, as well as from observed professional development and classroom practices by the researcher.Footnote 3 In addition to narrative being the research method, it is also how the research is presented, drawing on storied experiences of teachers and students (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). Thus, the method can also be described as narrative inquiry for school-based research (Xu & Connelly, Citation2010). The research text further illustrates a close-to-the-ground look at teachers’ collaborative inquiry on literacy work in a high poverty school through narrative reveals, revelations, and reformations (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2013) of mindset, knowledge, and practice.

3.1. The professional development series (PDS)

Developed by the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO, Citation2012), the PDS that teachers received was developed “to encourage a change in mindset among elementary educators” (ETFO, Citation2012, p. 4). By addressing teachers’ own assumptions, beliefs, and practices, the PDS provided the impetus for meaningful teaching practice reform when school teams gathered back at their school sites to develop new implementation plans based on collaborative inquiry amongst members.Footnote 4 The PDS took place throughout a two term span at a local teacher association conference site with three half days in total, and the impact analysis research took place over a two-year span at the school site.

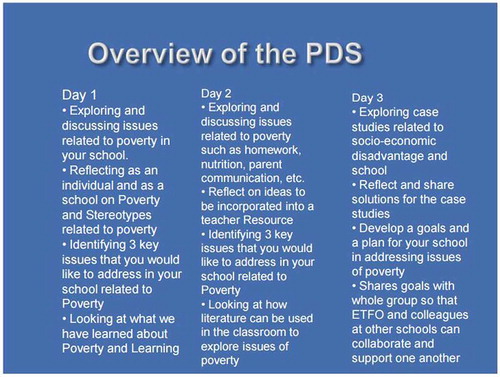

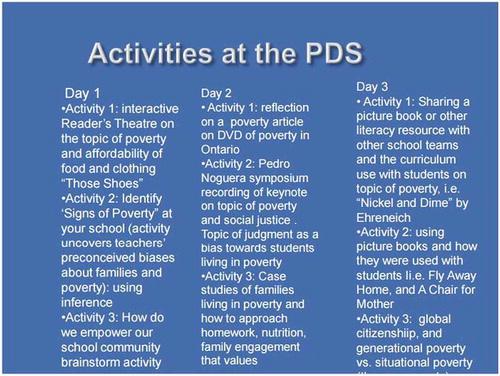

The PDS explored issues on outside-of-school influences related to poverty and inside-of-school influences related to curriculum practices. It addressed issues of bias and deficit conceptualizations of students and families living in poverty, explored topics such as subject matter, nutrition, parent engagement, value of family in school practices, and communication links to outside agencies as well as respectful parent engagement. Figure provides details of the PDS topics addressed. Figure provides details of the PDS activities which took place with three topics/themes that highlight literacy practices taken up in this study: global citizenship, inferencing, and social justice literacy.

School teams then engaged in professional learning back at school sites via a teaching and learning pathway in order to identify areas of concern from an inside-of-school perspective (i.e. subject matter and curriculum delivery), as well as from an outside-of-school perspective (i.e. community, geography, resources to the community, outside agencies, etc.). Case studies were explored, possibilities for solutions were reflected on, and goals were set for addressing poverty from both perspectives. Thus, the professional development was not top down scripted or mandated curricula for teachers’ literacy skill set training but, rather, professional development that was based on: (a) awareness, understanding, and action; (b) addressing stereotypes and how to move forward as a teaching community, and; (c) changing mindsets of deficit-based notions of what poverty entails, and using literacy to do so.

3.2. Collaborative inquiry: The teaching and learning critical pathway

The Teaching and Learning Critical Pathway (TLCP) is an instructional framework used widely in Ontario schools; school teams build toward teaching capacity as well as leadership capacity through a process of collaboration and collegial inquiry. It is a model that is aligned to Fullan, Hill and Crevola’s (2009) framework which focuses on cycles of formative assessment, personalization, and instructional practice in literacy (Fullen, Hill, & Crevola, as cited in Reach Every Student, Citation2009, p. 3). Building on the notion of improving collaboration in schools within school teams, the TLCP model was a good framework to use for teams after the PDS because each school team was invited to set goals and design action plans that reflected what they had learned from the PDS. The co-construction of collaborative approaches amongst teachers for professional practice was part of the data that was collected for the topic of literacy in this article, as it pertained to teacher knowledge, mindset, and literacy practice.

3.3. Research method

This study used qualitative methods that included case study method (Yin, Citation2003), use of narrative telling (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006), and narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). Case studies have several strengths, including their ability in addressing a variety of viewpoints (Merriam, Citation1998). Data collection was extensively prepared before each school visit, including the use of multiple sources of data, open-ended protocol questions, systematic routine to triangulate the data sources (as well as member checking the themes and categories which emerged from the data sources), theoretical propositions via follow-up field notes and organization for the framework for the case of the school (Yin, Citation2003). Interpretations were reflective so as to represent uniquely the school site (Stake Citation1995).

Narrative inquiry (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006) relies on stories as powerful tools for understanding experience in education (Dewey, Citation1938), teacher knowledge, and teacher inquiry. Educators’ practice and knowledge is understood over time by studying their experiences as narratives or stories. Places, people, and things in the context of schools are complex forces (Craig, Citation2003) that attribute to the narrative or story of literacy success. This was viewed as an important phenomenon during the data collection. The study identified and analyzed the narratives of five teachers and one administrator which illuminated awareness, understanding, and action after professional development on the topic of poverty was provided. Collected narratives from teachers offered retrospective accounts of their experiences with the professional development and how the professional development related back to their teaching and learning of literacy practices. The focus of data collection was from narrative telling (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006) on literacy practices by zeroing in on: the place of school and community; on the temporality, or past present and future, via teachers’ experienced knowledge in working with children and parents in the context of poverty, and; on the sociality and conditions of school climate and culture, inside-the-school and outside-the-school, and on relationships formed with students, parents, community workers/agencies and other educators. Through this approach, the three-dimensional inquiry space of narrative inquiry is integrated (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006). That is, the stories were analyzed, and careful attention was paid to: (a) temporality of happenings in the school community and how the temporal past, present, and future assist in shaping the stories of participants based on their lived experiences both in and out of school; (b) sociality, or interactions with people and situations, which help to deeply understand each particular story, and; (c) place, or the scene where events take place, aiding in concretizing each narrative further (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006).

During conversations, interviews, and classroom observations, data was collected on how teachers “lived out” their prior narratives about their literacy teaching and how these narratives were enacted via their literacy teaching with students in class. Ciuffetelli Parker (Citation2013) Narrative reveal, narrative revelation, and narrative reformation (3Rs) was a framework used to deconstruct further the research text, which offered particular insight into the impact of the professional development on teachers’ reformation of mindset.

3.4. Participants and setting

Fallsview is a small elementary K-8 school with approximately 250 students. Enrollment is declining due to transient issues. The demographic of student population is described as: a majority of White working poor families with approximately 11% Muslim, and 13% Vietnamese and Korean families also living below the poverty line. There are six Aboriginal Students in dire need. Fallsview is located in a small city in Southern Ontario. Close in proximity to a major tourism area, the contrast of war houses and subsidized apartments surrounding the immediate school community to the glitz and lights of the casinos and tourist area one kilometer away, paints a picture of the effects of tourism, seasonal dependence on work, and the recession which has closed down surrounding industrial factories, causing once middle income families now to live far below the poverty line. The schoolyard surrounds the older neighborhood, with a very large playground space. A breakfast and lunch club is operated by teachers on a daily basis, with food free of charge and teachers’ volunteering this service. Outside agencies such as the Lion’s Club have introduced character education to the school, and the Boys and Girls Club offer free bussing for some children.

In total, 15 teachers comprise the faculty at Fallsview. Five teachers were part of the team that received the PDS, and consequently the focus group for this study. Sharon, a Grade 4/5 teacher and the school librarian has been at the school for six years while teaching for seven years. Jake is a Grade 5/6 teacher and has been at the school for six years, with fifteen years teaching experience. Marcia is a Grade 4 to Grade 8 French teacher (French is a mandatory curriculum subject in Ontario schools) who also teaches Grade 2 at Fallsview. She has been at the school for two years with a total of three years teaching experience. Mandy is a Grade 7/8 veteran teacher with seven years at Fallsview. Jane is a special education teacher with many years experience. The principal of the school is Sam Hardy who has been an administrator for approximately ten years, four of which have been at Fallsview. Sam expressed that his teaching staff is committed to students and to collaboration. Teachers made several positive comments about Sam and about his impact on the school community.

3.5. Data collection

As the principal investigator of the project, I took extensive field notes with a team of two researchers and one research assistant after each school site visit, as well as after each professional development session. Follow-up visits with additional teacher and principal interviews as well as unobtrusive classroom visits helped the research team focus on a recurring theme generated from the first phase of the project, namely, that of the impact of poverty professional development and collaborative inquiry on literacy practices. In sum, there were three phases of this study where data was collected. Specifically:

| (1) | The PDS (3 half days): The PDS which the five teachers and the administrator from Fallsview attended on three separate occasions over two terms, provided the school team with collaborative inquiry-based knowledge about school planning for communities affected by poverty as well as extensive professional development on poverty and schooling, deficit conceptualizations, and reforming mindset and practice (see Figures and ). Data collected during this phase included field notes, and summary reflections of activities, and conversations and insights highlighted by the ETFO two member workshop presenters to the school team. | ||||

| (2) | School site visit one: The five teachers and principal team then participated in a school research focus group several months following the PDS at Fallsview. The focus group came together for two hours and included in depth conversations about the professional development received and impact of the professional development program for school planning and instruction, including literacy instruction. A separate two hour interview was conducted with the principal of Fallsview. Focus groups and interviews were audio-taped for later transcription and analysis. Additional data collected during this phase included field notes and narrative summary reflections of the school visit. | ||||

| (3) | (a) School site visit two: During the second school visit to Fallsview after one year had passed, teachers were unobtrusively observed teaching in their classrooms, to determine how teachers “lived out” their knowledge acquisition from the professional development they had received and/or whether their literacy practices had shifted. During the classroom observations, no recordings took place. Field notes were recorded following the classroom observations which focused on the effectiveness of the professional development as it related to the participants’ literacy classroom practices. No data was collected on any of the students. (b) School site visit two: A second research focus group and interview were conducted with the same teachers observed in classes, as well as a second interview with the administrator of school team. Follow-up information on the impact of the professional development was provided by respondents, including the collaborative inquiry of the TLCP on literacy practices. Focus groups and interviews were audio-taped for later transcription and analysis. Additional data collected during this phase included field notes and narrative summary reflections of the school visit. | ||||

During the data collection, the overarching question was asked: how has the professional development on poverty your school team received impacted your work/practices in school? Other examples of focus group questions that generated responses, which illuminated the discussion of reformation of mindset about children and families living in poverty through collaborative inquiry, social justice literacy practices, and narratives shared included:

How did/do teachers teach differently because of the professional development program on poverty and education?

How have your views reformed or reshaped how you think about students and families living in poverty?

What literacy resources or implementations have helped you to more effectively service the students at your school?

3.6. Data analysis

A bottom-up approach was used to analyze the data (transcripts, narrative reflections, field notes) by culling all sources, reading and coding the issues, coding the issue-relevant meanings as patterns, and then collapsing the codes into themes (Creswell, Citation1998, Citation2005). The themes that emerged are represented as a narrative form of text. Likewise, narrative responses in recorded focus groups, interviews, and conversations, offered both varied and similar recurring patterns of storied experience from participants, which consolidated the themes generated.

This study was a qualitative but not a comparative study on the impact of professional development on issues related to poverty on other school sites. Thus, it is acknowledged that the practices used at Fallsview may or may not be similar from schools elsewhere (in high poverty contexts or not), or that practices may or may not resemble those in schools where poverty professional development was not received. What is important to consider for this school case is that the narratives both represent the phenomenon of success in the schools studied in the larger impact project,Footnote 5 and gives storied practice as well to the phenomenon of collaborative inquiry and literacy practices.

Following, the findings discuss the literacy practices taken up as themes generated from the analysis of data. The themes illuminate teacher narratives and their work with students and families living in poverty as well as reformation of mindset and practice. The literacy themes discussed are: global citizenship; the value of inferencing for students and teachers; social justice literature.

4. Findings/Results

4.1. The narrative of global citizenship: From the nobody doll to how to be in the world

After the PDS, teachers at Fallsview School collaboratively decided that their TLCP topic area would be global citizenship. Their awareness of social justice and advocacy was strongly highlighted for them as a team during the professional development on poverty alongside other school teams. To do this, they decided to organize language programming around a broad social justice literacy idea. Mandy, A Grade 8 teachers, explains:

Well one of the things that we’ve done as a whole school is focus on global citizenship. So, we’ve taken character education really to the next step. As individual classes and as a whole school we’ve done the Who Is Nobody project (http://www.whoisnobody.com/), where a doll moves from class to class and then each child gets to decide what is important to them and then from there the doll takes on an attribute. So the children do fundraising for their cause, they do advertising for their cause. Since September specifically with that we’ve helped the Salvation Army. The children donated 6 barrels of gently used toys. We’ve helped the Humane Society, we’ve helped Jump Rope for Heart, the World Wildlife Federation. So we continue to instill in the children that, no matter what your circumstances are, we are positive that you can make a difference in this world for them to be aware that they are important, and this doll helps them to understand that the idea is to change the doll from “Nobody” to “Somebody.” At the end of Nobody moving from class to class, the doll will have character traits represented physically on him/her. For example, Nobody has a dog tag for helping the Humane Society, he has a hat with a crushed can because one of the classes decided recycling was important to them …

I think the TLCP did provide us a framework and it gave us the time to get together as a group, and say this is what we want the theme to be and this is how we are going to succeed and these are the curriculum expectations that we are going to focus on.

Jane, the special education teacher, also added about the collaboration on this literacy practice:

In my experience, teachers need to have a buy-in and if they don’t then immediately whatever you’re trying to present as an initiative will fail. In this community, I think we’re all equal partners in that so it’s really easy to bring in an initiative or some theme that is going to better our children’s chances of success because we are already there. It doesn’t matter who it comes from, because we’re already there as partners. If it’s brought in as an initiative from the board through the principal and there isn’t that buy-in from staff, it’s not going to happen.

Sam Hardy, the principal of the school, consolidated the need for teachers’ collaborative inquiry that is site based rather than top down driven, and that focuses on teachers as professionals who need first to understand context before attending to action. He says of his teaching staff, “They’re the professionals. I’m not half the instructors that they are.” He adds about literacy and the collaborative inquiry as it relates to the PDS:

With [collaborative inquiry]—I think they really just needed the time to sift through their understanding and really they needed time to sit with it and play with it and get better at it … and it still comes back to a theme, it still comes back to relevant and engaging … Of course the first reaction of everyone is now we’re teaching [children] how to be people too. Yes, we are. We are supposed to do that.

4.2. The narrative of inferencing: Literacy for students and teachers

During the TLCP collaborative inquiry process, the principal and teachers at Fallsview also focused on the literacy practice of inferencing, based on school results from formative assessment data. The narrative below illustrates the complexity of standardized test scores juxtaposed with real-life application of what students need, to be successful. Sharon, the school librarian, first explains,

I think we just try to prepare our kids in a way that is meaningful for them. We try to appeal to their interests, their schema and things they know about and what we know about them in order to teach them skills for the test, not only are you teaching the curriculum expectations but you can also bring in their own interests to help the students be interested in what they’re learning.

Mandy agrees,

The test is not the be all and end all and I think the students understand that as well, and of course we want them to do well on the test, but what kind of person are you that’s taking the test? That’s my perspective, that I’m able to breathe much better in a school where the performance of the poor child is not the be all and end all, and there are many more elements to the child. It’s more complicated.

Principal Hardy had this to say about inferencing and how bringing in the literacy framework of the TLCP after the PDS helped to consolidate what was important for students and teachers’ new insights at Fallsview:

Often a significant barrier in schools like ours is schema. When you look at the way [students] are evaluated large scale, it requires schema. In order to have inferences and connections, you need to have something to draw from. We’ve talked a lot about connections, making connections versus just connections. “We read a story about a dog, well so-and-so has a dog, I’ve read a story about a dog. How does that make you understand the text?” There are just connections, versus good connections. Again, the ability to infer [is important]. It requires kids to have previous experiences … we’re trying to be very intentional about the need to get better at inferencing and connections. Not the kids, the staff! And that’s how I sold the idea of TLCP [to my staff]. “It’s not the kids that need to change, it’s us that need to change! The data historically tells us that we’re falling apart in our ability to make connections. Who needs to change? Us or the kids? We need to change our understanding.”

4.3. The narrative of social justice literacy

While consolidating the choice to concentrate on the literacy strategy of inferencing, Sharon also shared how making connections and inferencing tied directly to the theme of social justice and how the PDS influenced directly the school’s literacy goals toward this end:

I think I feel more of an awareness. When I have expectations for the kids, I am more aware of their circumstances. Not that I wasn’t before but [I am] more sensitive to it now [after the PDS]. So [when] we decided on a theme of global citizenship in order to teach those two things [inferencing and making connections], I know personally, all the literature that I was exposed to going to at the [PDS] workshops, the picture books, [changed] my decisions [of what library books to incorporate in classes. The [social justice books] have become so helpful with this because I’ve been able to use some of the picture books, and the novels [throughout the school]. I just found out that we were approved, I had applied for subsidy from the writers union and Rebecca Upjohn is coming in April and she’s the [author] who writes Lily and the Paper Man.

I think it’s made me more aware of having an ongoing dialogue with the children. Like when we were doing global citizenship, two of the books were called Those Shoes and Tight Times, and that was one that we used, and specifically we were working on inferencing and connections and with that story, every single child in grade 7/8 had a story about shoes and making that connection. So, that book was very powerful. Another thing we’ve used in intermediate is Craig Kielburger and the Me to We literature and just this past week I was telling Sam that one of our children, a very high functioning autistic child said to the class, “What this has made me realize is that no matter how poor I am there are children all over the world who are poorer than I am and I can make a difference.”

Sharon further shares:

We found too within our TLCP that Mandy, using Me to We, not only saying [it] is a great book, but [sharing] how she used it, and how you can use a picture book in a junior or intermediate class. Here’s what it’s about and here’s what I did with my kids. Here are some of the results that I’ve got from it.

5. Significance

The study of professional development and its impact on teachers’ narrative reformation of mindset is significant because of the collaborative inquiry (TLCP) and how it was carried out in classrooms using literacy practices related directly to the context of teachers’ newly lived awareness and deeper understanding of students’ lives. It is a study of teacher narratives and reformed mindset on students living in poverty as seen through purposeful literacy practices that focused on the child’s world. In other words, this is not a study of high stakes standardized testing, or literacy preparation, or student literacy scores in a high poverty school. Nor is it a study that instructs practitioners on how to “teach to the poor,” which would have reduced it altogether to another deficit conceptualization of poverty and schooling. Unlike other research projects (Neuman & Celano, Citation2012) or workshop strategies (Payne, Citation1996), which focus on such ideas as “information capital” or “frameworks of poverty,” this study contributes the lived stories of teachers, and students, and families—their narratives of experience of what it means to teach and live in challenging circumstances. It goes further to grapple with this complexity by inquiring deeply into literacy practices that burrow beneath the surface and into understanding as much as we can about the human condition, and about of our students’ way of understanding their world. Like Milner (Citation2013) inside-of-school and outside-of-school factors, which help to bridge the context of curriculum to the context of personal living, this study’s significance on teacher narratives and reformation of mindset is evidenced by the kind of literacy practices that are taken up after receiving professional development that challenged teachers’ thinking about students living in poverty.

6. Implications/Conclusion

What happens to teachers like Patrick, whose narrative reveal opened this study? Would he do well to receive further professional development on poverty and schooling? Patrick did receive further support in learning more about the context of his students’ lives, and he did reframe his way of thinking, it may surprise the reader. However, it was his own lived experience that may have shifted and ultimately reformed his teaching practices. This did not happen overnight. With passing time, Patrick became a new father of triplets; he began taking note of the lived experiences of his students; he began respecting the parents and felt accepted as a teacher and, following much reflection and shared lived experiences of learning alongside his students, the respect was reciprocated by students and parents alike. We can say, in essence, that life and narrative intersected in a place for Patrick that brought both revelation of how he had once understood his students’ lives and a new narrative reformation and changed mindset of living alongside his students and their families with a deeper understanding of his teaching life. He humbly explains,

There’s a respect [now] and it’s something [students] don’t have for everybody and you just have to show some interest in their lives, and what they’re going through and show a little empathy, and a little understanding, and just show them that you care about what they’re going through… If I were to come in everyday and just look at curriculum, and teach what I have to teach—I don’t know if I’d still be teaching. Building relationships. Establishing relationships, absolutely … For me it’s … seeing [poverty] here every day, and now that I have kids…teaching here has really helped me become a better father, a better husband … We’re here to better [children’s] lives … I think you have to strip everything down, and start again … so instilling in [our students and everyone] that they can do anything, giving them a little credibility.

One lesson is that dialog through school practices such as collaborative inquiry can be difficult to sustain. When asked explicitly what impact the professional development had on Fallsview, the consistent reply had almost always to do with dialoguing more with colleagues, and with bringing the focus of poverty to the forefront, which ultimately validated teachers’ intuitive sense to be curriculum makers (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1988) for the benefit of students’ success at Fallsview. Teachers did not want the professional development to end. And, there is evidence that professional development does indeed help sustain and guide future success (Reach Every Student, Citation2009). A grass roots level of the collaborative inquiry, supported by outside professional development, means that it is important for schools, such as Fallsview, to trust their vision of curriculum making as a school team, for what is best for themselves as developing teachers and as students in that community. School issues are context specific and student specific. But, in order to know what is best for students, teachers at Fallsview also needed to be open to understand better the context in which their students and their families lived. With this comes the knowledge, trust, and value embedded aspect of school climate and culture too, which teachers such as Jane referred to. Dialoguing, in this regard, is a cyclical and reforming practice, and it takes constant engagement to keep the collaborative inquiry piece sustainable.

A second lesson and implication is that school leadership and resisting deficit-based explanations of students living in poverty depends on the quality of leadership present in schools.

Success at Fallsview was not formulated by attaining the highest standardized test scores in the province, to be sure. Research on poverty (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2011; Dudley-Marling & Lucas, Citation2009; Milner, Citation2013) has shown other ways to measure success: school climate, attitude, beliefs and values of students and teachers and their worth in society, hope and dreams for the future, and literacy practices that speak to the theme of relationship and global citizenship. Principal Sam Hardy imbedded leadership amongst teachers, to ensure that deficit conceptualizations of students living in poverty was a matter that was consciously addressed as teachers continued their literacy practices based on social justice issues of what it meant to be a citizen in the world. Sam expected his teaching staff to challenge stereotyping and bias and to intervene in professional conversations where deficit-based assumptions were left unchallenged. In fact, it rightfully may be a moral duty to do so in today’s schools.

A third lesson is this: hope for students’ literacy success rests within school walls, and is affected by school climate, belonging, and reformation of educators’ mindset of children and families living in poverty. The underlying philosophy at Fallsview School, from conversations with the teaching staff, the principal, and from classroom observations, is that there was always hope. The school climate at Fallsview was such that the students were not students of just one teacher, but of all teachers, as a community. The library furniture was built by Sharon’s father, installed as a community, for instance, where all students felt comfortable to be and learn. Belonging is pivotal. Mandy offered the sentiment of hopes and dreams, that every student deserves, and to close off succinctly, Jane says:

Poverty is not an excuse … we look at how we can enrich [students’] lives [to] ensure that these students are successful in life. There is a [line] Sharon and Mandy say all the time about when others aren’t around you: “How do you act when there’s no one watching?” I like that. Poverty is not an excuse.

To offer hope, to have students’ resiliency carry them forward, to believe that poverty is not destiny, must begin with teachers’ beliefs, values, and hopes of the same. It has to do with changing the narrative by which we live and how we enact teaching practices in order to narratively reform those practices. The PDS offered to Fallsview created a space for deep and meaningful reflection on literacy practices, and with it the ability for collaborative inquiry to reform the school’s literacy program. What also reformed along the way was teachers’ mindset on students’ ability to be successful through the use of progressive literacy practices that focused on global citizenship, inferencing about the world, and social justice literacy.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Darlene Ciuffetelli Parker

Darlene Ciuffetelli Parker is an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at Brock University. Her poverty research and method of narrative inquiry are intricately interwoven, publishing and fostering deeper understanding of educators’ use of narrative in areas of: poverty, literacy, mental health, and various diverse issues in education. Ciuffetelli Parker continues to research and write on poverty and schooling as she advances partnerships to support deeper knowledge. She readily is an invited keynote/speaker, providing impactful talks to various organizations. Ciuffetelli Parker was a school administrator, literacy resource-consultant, and elementary teacher in Toronto before joining the faculty of education at Brock University. She is widely published and has received the Early Career Award of the Narrative Research Special Interest Group in the American Education Research Association, the Award for Excellence in Teaching at Faculty of Education at Brock University, and the Brock University Award for Distinguished Teaching.

Notes

1. The Ontario Poverty Project was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Education and the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO) to investigate successful school practices in high poverty areas as well as the impact of professional development on poverty on school practices. Funds for a four-year case study project as well as a two-year impact professional development project were provided to the author of this article by ETFO. In total, 16 schools were researched with over 100 teacher, administrator, parent, and community worker participants.

2. The author would like to acknowledge the generous research funding provided by the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. Select notions, citations, and results of this paper were generated from the author’s work and publication from the larger research project (see Ciuffetelli Parker & Flessa, Citation2011). The topic of this paper, however, is new and its material, data sources, or results have not been previously published.

3. A research team consisted of the principal investigator (author of this article) as well as a faculty collaborator and graduate research assistant.

4. In all, five school teams took place in the larger PDS impact study with six participants from each school, a total of 30 participants. This article reports on one of the school teams, Fallsview School (pseudonym) from data, field text, and analysis not previously reported on or published. The study was funded by the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario.

5. In fact, two studies on 16 schools in Ontario reported successful strategies that were often related to literacy strategies that focused on collaborative inquiry, community agency, character education, family awareness, and respectful parent engagement (Ciuffetelli Parker, Citation2010, Citation2011).

References

- Barone, D. (2011). Welcoming families: A parent literacy project in a linguistically rich, high-poverty school. Early Childhood Education Journal , 38 , 377–384.10.1007/s10643-010-0424-y

- Bereiter, C. , & Engelmann, S. (1966). Teaching disadvantaged children in preschool . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bernstein, B. (1971). Class, codes and control . London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203014035

- Campaign . (2000). Needed: A federal action plan to eradicate child and family poverty in Canada . Toronto: Family Service Toronto.

- Campaign 2000 Report Card. (2012). 2012 Report card on child and family poverty . Toronto: Campaign Ontario 2000.

- Campaign 2000 Report Card. (2013). Beyond austerity: Investing in Ontario’s future . Toronto: Campaign Ontario 2000.

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. (2010). Possibilities: An impact analysis of schools working with children and communities affected by poverty . Toronto: Report for Elementary Teachers' Federation of Ontario.

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. (2011). Related literacy narratives: Letters as a narrative study inquiry method in teacher education. In J. Kitchen , D. Ciuffetelli Parker , & D. Pushor (Eds.), Narrative inquiries into curriculum making in teacher education (pp. 131–149). Bingley: Emerald.

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. (2012). Poverty and education: A Niagara perspective (8 pages). St. Catharines, ON: Policy Brief, Niagara Community Observatory.

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. (2013). Narrative understandings of poverty and schooling: Reveal, revelation, reformation of mindsets. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education (IJCDSE) , 3 (2). ISSN 2042 6364. Retrieved from http://www.infonomics-society.org/IJCDSE/

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. (2015). Poverty and schooling: Where mindset meets practice. What works: Research into practice series (4 pages). Ontario Association of Deans of Education (OADE) and the Ontario Ministry of Education.

- Ciuffetelli Parker, D. , & Flessa, J. (2011). Poverty and schools in Ontario: How seven elementary schools are working to improve education . Toronto, ON: Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario.

- Clandinin, D. J. , & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Connelly, F. M. , & Clandinin, D. J. (1988). Teachers as curriculum planners: Narratives of experience . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Connelly, F. M. , & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green , G. Camilli , & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in educational research (pp. 477–489). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- Craig, C. (2003). Narrative inquiries of school reform: Storied lives, storied landscapes, storied metaphors . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . New York, NY: Collier Macmillan Publishers.

- Dudley-Marling, C. (2007). Return of the deficit. Journal of Educational Controversy , 2 (1). Retrieved from http://www.wce.wwu.edu/Resources/CEP/eJournal

- Dudley-Marling, C. , & Lucas, K. (2009). Pathologizing the language and culture of poor children. Language Arts , 86 , 362–370.

- Eithne, K. (2010). Improving literacy achievement in a high-poverty school: Empowering classroom teachers through professional development. Reading Research Quarterly , 45 , 384–387.

- Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO) . (2012). Possibilities: Addressing poverty in elementary schools . Toronto: ETFO.

- Faltis, C. , & Abedi, J. (2013). Extraordinary pedagogies for working within school settings serving nondominant students. Review of Research in Education , 37 , vii–xi.10.3102/0091732X12462989

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . New York, NY: Herder and Herder.

- Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Goodwin, M. H. (1990). He-said-she-said: Talk as social organization among Black children . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Gorski, P. C. (2008). The myth of the “culture of poverty”. Educational Leadership , 65 , 32–36.

- Gorski, P. C. (2012). Perceiving the problem of poverty and schooling: Deconstructing the class stereotypes that mis-shape education practice and policy. Equity & Excellence in Education , 45 , 302–319.10.1080/10665684.2012.666934

- Hart, B. , & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children . Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Haughey, M. , Snart, F. , & da Costa, J. (2001). Literacy achievement in small grade 1 classes in high-poverty environments. Canadian Journal of Education , 26 , 301–320.10.2307/1602210

- Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hooks, B. (2000). Where we stand: Class matters . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jackson, S. C. , & Roberts, J. E. (2001). Complex syntax production of African American preshcoolers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research , 44 , 1083–1096.

- Labov, W. (1972). The language of the inner city . Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lewis, O. (1966). The culture of poverty. Scientific American , 215 , 19–25.10.1038/scientificamerican1066-19

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study research. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication , 40 , 182–196.

- Michaels, S. (1981). Sharing time: Children's narrative styles and differential access to literacy. Language in Society , 10 , 423–442.

- Miller, P. J. , Cho, G. E. , & Bracey, J. R. (2005). Working-class children’s experience through the prism of personal storytelling. Human Development , 48 , 115–135.10.1159/000085515

- Milner, H. R. (2013). Analyzing poverty, learning, and teaching through a critical race theory lens. Review of Research in Education , 37 , 1–53.10.3102/0091732X12459720

- Nelson, J. , Martin, K. , & Featherstone, G. (2013). What works in supporting children and young people to overcome persistent poverty? A review of UK and International literature . Belfast: Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minster (OFMDFM).

- Neuman, S. B. , & Celano, D. C. (2012). Giving our children a fighting chance: Poverty, literacy, and the development of information capital . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Ng, J. , & Rury, J. (2006). Poverty and education: A critical analysis of Ruby Payne phenonmenon . Teachers College Record. Retrieved from http://www.tcrecord.org

- Osei-Kofi, N. (2005). Pathologizing the poor: A framework for understanding Ruby Payne’s work. Equity & Excellence in Education , 38 , 367–375.10.1080/10665680500299833

- Payne, R. (1996). A framework for understanding poverty . Highlands, TX: Aha! Process.

- People for Education . (2013). Poverty and inequality . Annual report on Ontario’s publically funded schools. Toronto: People for Education.

- Pushor, D. , & Murphy, B. (2004). Parent marginalization, marginalized parents: Creating a place for parents on the school landscape. Alberta Journal of Educational Research , 50 , 221–235.

- Reach Every Student . (2009). The use of the teaching and learning critical pathway. A research report published by the LNS research and evaluation management team , Ministry of Education of Ontario, Toronto.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Valencia, R. R. (1997). The evolution of deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice . London: Falmer Press.

- Xu, S. & Connelly, M. (2010). Narrative inquiry for school-based research. Narrative Inquiry , 20 , 349–370.10.1075/ni.20.2

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education , 8 , 69–91.10.1080/1361332052000341006