Abstract

This study used interviews, observations and documentary evidence to analyze the professional learning of sixteen elementary school English teachers and two expert teachers during the pre-observation conference, observation, and post-observation conference from three-step teaching demonstrations. This study has the following major findings. First, the knowledge and competence that participants gained the most, was pedagogical knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. Participants demonstrated “seeing as” and “seeing in” during observations but not “seeing that.” Second, six major factors influenced teachers’ professional learning including the use of handbooks for observations, the host or hostess’s expertise, the observed teachers’ expertise, the observers’ discussions, location, and training workshops. These findings provide a theoretical framework and guidelines for elementary school English teachers to gain professional learning through the demonstrations.

Public Interest Statement

Teachers giving demonstrations and teachers observing other teachers have been regarded as a form of collaborative professional development and this type of professional development can be used to improve teachers’ classroom practice and students’ performance (Grimm, Kaufman, & Doty, Citation2014; Lam, Citation2001). This study used interviews, observations and documentary evidence to analyze the professional learning of sixteen elementary school English teachers and two expert teachers during the pre-observation conference, observation, and post-observation conference from three-step teaching demonstrations in Taiwan.

1. Introduction

Teachers giving demonstrations and teachers observing other teachers have been regarded as a form of collaborative professional development and this type of professional development can be used to improve teachers’ classroom practice and students’ performance (Grimm et al., Citation2014; Lam, Citation2001). Teachers are engaged in reflective professional dialog about their work and they can receive focused instructional support. Moreover, teachers who give teaching demonstrations can construct and reconstruct knowledge, competence, experience, and expertise from peers and experts who understand classroom practice (Estyn., Citation2014; Jang, Citation2008; Zepeda, Citation2012).

The Ministry of Education (Citation2014) mandates that from 2017, principals and teachers from elementary schools, through to senior high schools, should give at least one teaching demonstration in each academic year. Such teaching demonstrations involve the three-step process. First, during a forty-minute pre-observation conference the teacher who is giving the demonstration is invited to describe his or her lesson plans, the learners’ background, activity designs, or teaching philosophy. An expert teacher, a colleague, or a professor invited by the school administrators, hosts the pre-observation conference, explains the observation tools, and states the purpose and focus of the observation. A maximum of fifteen teachers can attend the teaching demonstration either voluntarily or because they are obliged to do so. Second, during the observation, these fifteen observers observe the teacher’s forty-minute teaching demonstration and take notes on the students’ performance and interaction. Finally, the teacher who taught the lesson shares how she or he feels about the demonstration and the host invites the observers to share their observations and to ask the teacher questions based on their observations.

Based on a number of three-step teaching demonstrations that were conducted with English teachers in an elementary school in New Taipei City in Taiwan, this study explores both the observers and the teachers’ professional learning. In so doing, the study asks the following two questions. First, what did elementary school English teachers gain in terms of their professional learning and the development of their reflective skills from the teaching demonstration? Second, how did elementary school English teachers gain professional learning and develop reflective skills from the teaching demonstration? Suggestions about the effective design of the pre-observation conference, the observation of the teaching demonstration, and the post-observation conference in terms of the professional development of elementary school English teachers are discussed.

2. Literature review

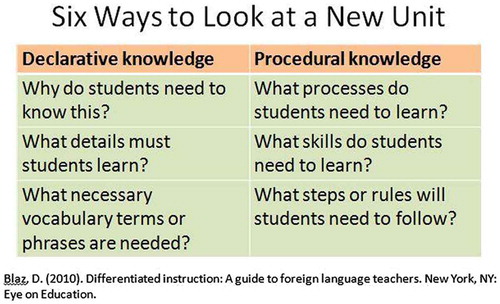

Shulman (Citation1987) identifies seven categories in the knowledge base for teachers, of which he emphasizes the pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), because it is the combination of content and pedagogy. Scholars have constructed different knowledge bases covering language teacher education as in Table . Language teachers can gain knowledge base and professional learning through observations.

Table 1. Different knowledge bases of language teacher education

The following literature review discusses issues and analyzes empirical studies related to teaching demonstrations in terms of pre-observation conferences, the observation itself, and post-observation conferences.

2.1. Pre-observation conferences

A workshop or training session on observations should be given to teachers prior to taking part in an observation (Goe, Biggers, & Croft, Citation2012; Tzotzou, Citation2014). In a study of five language teacher instructors in a Saudi Arabian University, conducted by Shah and Harthi (Citation2014), respondents reported that having observers who lacked experience, training, and qualifications in the field of language teacher education made their comments and feedback sound ridiculous and irritating. During the training, the trainer can discuss and practice various observation and conferencing techniques as recommended by scholars in the literature (Stillwell, Citation2008). The three Greek EFL teachers in Tzotzou’s (Citation2014) study were exposed to various issues regarding the observation during the workshops arranged prior to the observation.

During pre-observation conferences, teachers and observers should have time to discuss the lesson, focus of the classroom observation, and acquire contextual information about the learners and the class (Estyn, Citation2014; Grimm et al., Citation2014; Richards & Farrell, Citation2011; Tzotzou, Citation2014; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009). As shown in Table , observations can focus on different aspects of classroom practice such as classroom management, teachers’ use of language, and students’ use of language (Barocsi, Citation2007; Richards & Farrell, Citation2011; Zepeda, Citation2012). The pre-observation conference is important because it is used to build trust between the observers and the observed, something that is crucial for the later discussion about the lesson and instructional strategies (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009).

Table 2. Observation focus (Richards & Farrell, Citation2011, pp. 90–91)

2.2. During observation

Orland-Barak and Leshem (Citation2009) used Kvernbekk’s (Citation2000) “seeing as,” “seeing in,” and “seeing that,” to analyze 30 Israeli EFL student teachers’ observation entries. They concluded that “observation constituted a site for making assumptions, for taking a stance, for articulating new insights, for triggering connections in teaching and learning, and for confronting educational beliefs” (p. 31). Whilst “seeing as” is defined as “identifying similarities and differences” and “seeing in” as “developing practical wisdom,” “seeing that” refers to “interpreting beyond a particular case” (pp. 35–37).

Classroom observation should have a clear focus and such structured observation can raise the observers’ awareness of classroom practice (i.e. Barocsi, Citation2007). It has been suggested that observation sheets, checklists, seating charts, or observation tasks should be provided for observers to systematically focus on the area(s) of concern and reflection (Akbari, Samar, & Taijk, Citation2006; Richards & Farrell, Citation2011; Tzotzou, Citation2014; Wajnryb, Citation1992; Wallace, Citation1991).

Richards and Farrell (Citation2011) also suggest that teachers should take field notes and produce a narrative summary of the observation. Whilst field notes consist of brief descriptions of key events that occurred throughout the session, a narrative summary is defined as “a written summary of the lesson that tries to capture the main things that happened during the course” (Richards & Farrell, Citation2011, p. 95). These notes, sheets, and tasks can be used to trigger professional conversations during the post-observation conferences (Barocsi, Citation2007; Goe et al., Citation2012; Salas & Mercado, Citation2010; Zepeda, Citation2012).

2.3. Post-observation conferences

At the start of the post-observation conferences, the teachers (the observed) should be given ample opportunity to talk about their lessons, guided by thoughtful open-ended questions (Richards & Farrell, Citation2011; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009). During the post-observation conferences, different roles can be assigned such as conductor or counselor, as shown in Table (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Wallace, Citation1991)

Table 3. Roles during the post-observation conferences (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Wallace, Citation1991)

The major purpose of the post-observation conference is to help teachers improve their classroom practice (Sweeney, Citation1983). In Kang and Cheng’s (Citation2014) study, Valen, a middle school English teacher in China, responded with “OK,” as feedback to her students. She became aware that this was a problem during the post-observation conference and modified her way of giving feedback in order to motivate her students to actively participate in classroom activities.

Observers’ feedback can be confirmatory, corrective, or constructive (Kurtoglu-Hooton, Citation2004). Whilst confirmatory feedback is used to praise the teacher who did well and to encourage this teacher to try to pursue new avenues and challenges, corrective feedback is given based on expected behaviors and it is “a gentle telling off” (Kurtoglu-Hooton, Citation2004, p. 3). Constructive feedback provides teachers with objective insights without criticizing them (Carroll & O-Loughlin, Citation2014; Kurtoglu-Hooton, Citation2004).

The oral and written feedback that four university supervisors and 30 cooperating teachers gave to 52 Turkish EFL student teachers during the post-lesson conferences, focused on common themes such as time management, target language use, classroom management, and improvement in the quality of teaching. Such feedback enriched student teachers’ learning and professional development (Akcan & Tatar, Citation2010). Finally, at the end of the conference, during the debriefing and follow-up, all teachers can be asked to reflect on the new insights they experienced and on their learning as a result of the observation (Tzotzou, Citation2014). Salas and Mercado (Citation2010) suggest that teachers should look for the bigger picture of the instruction and students’ learning. Hence, the facilitator who leads the post-observation conference could end it with a summary statement on the specific, reachable, comprehensive, and measurable goals for teachers’ further improvement (Sweeney, Citation1983).

2.4. The current study

Current empirical studies focus on either the pre-observation conference, the observation, or the post-observation conference among pre-service general education teachers (e.g. Jang, Citation2008); in-service general education teachers (e.g. Akcan & Tatar, Citation2010; Lam, Citation2001), pre-service English teachers (e.g. Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009), in-service English teachers (e.g. Kang & Cheng, Citation2014), or language teachers at tertiary levels (e.g. Carroll & O-Loughlin, Citation2014; Shah & Harthi, Citation2014). This study aims to analyze the elementary school English teachers’ professional learning during the three steps of the teaching demonstration: the pre-observation conference, the observations themselves, and the post-observation conference.

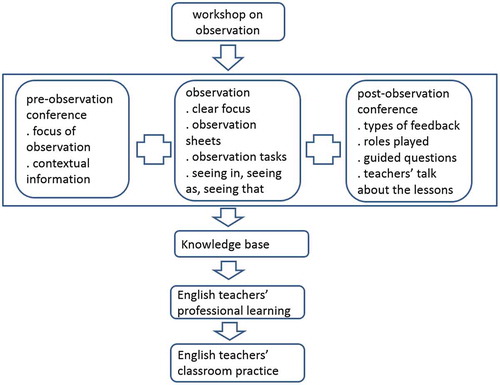

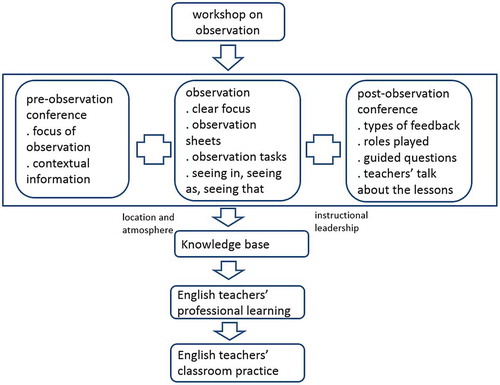

Based on the above empirical studies of classroom observations, the conceptual framework for this study is shown in Figure . The classroom observation process begins with the pre-observation conference and ends with the post-observation conference. A workshop should be provided to train elementary school English teachers to equip them with the expertise and competence to engage in the three steps of classroom observation. The focus for the observation and contextual information should be provided to observers during the pre-observation conference. During the observation, observers should have a clear observational focus when completing the observation tasks. Observations should allow observers to be able to experience “seeing as,” “seeing in,” and “seeing that.” In the post-observation conference, the teacher who gives the demonstration should be given the opportunity to talk about the lesson. A range of guided questions can be used to foster discussion and dialog during the post-observation conference. Observers can play different roles and provide various types of effective feedback. Such three-step classroom observations can help English teachers gain their different knowledge base, foster elementary school English teachers’ professional learning, and transform their learning into classroom practice.

3. Method

This is a qualitative case study. The case study was based on teaching demonstrations and the unit of analysis was English teachers’ learning and opinions about their learning during teaching demonstrations.

3.1. Settings and participants

English teachers who gave teaching demonstrations, English teachers who carried out classroom observations, and instructional coaches were selected for this study. A total of twenty participants were involved in this study and all of whom are elementary school English teachers in New Taipei City in Taiwan (as shown in Table ). The names are pseudonyms. The researcher observed four teaching demonstrations given by Ann, Elva, Gill, and Vic. Roughly fifteen English teachers attended and observed each demonstration. The researcher contacted these English teachers and invited them to participate in the study; twelve teachers were willing to take part. Moreover, two elementary school expert teachers (Mary, Lena) voluntarily joined the study. Dr Chen and Dr Lin are university professors and they were also invited to participate in the teaching demonstrations.

Table 4. Participants’ demography

Table shows the four teaching demonstrations in terms of the observed teachers, host or hostess, and the invited professors. Dr Chen was the invited guest for three of the teaching demonstrations.

Table 5. Four teaching demonstrations

3.2. Data collection

Data collection lasted for one academic year from September 2014 to June 2015. The data collected included observation fieldnotes, documents, and interviews. In order to ensure the credibility of the study, these multiple sources were collected, compared, and cross-checked.

The first source of data derived from the researcher’s attendance and observations of four rounds of the three-step process of teaching demonstration including pre-observation conferences, observations, and post-observation conferences. Documents were the second source of data and these included the teachers’ lesson plans, worksheets, teaching materials, the host’s PowerPoint slides, observational tools, and written accounts of the participating teachers’ reflections. Documents were copied or scanned for later analysis.

Participants were interviewed following the teaching demonstration. Each participant was interviewed for forty to sixty minutes. An interview protocol was designed. The first part of the interview was related to participants’ educational and teaching background and their experience of giving or attending teaching demonstrations. The second part of the interview was about their professional learning from teaching demonstration as well as their attitude toward, and recommendations for teaching demonstrations. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed for later analysis.

3.3. Data analysis

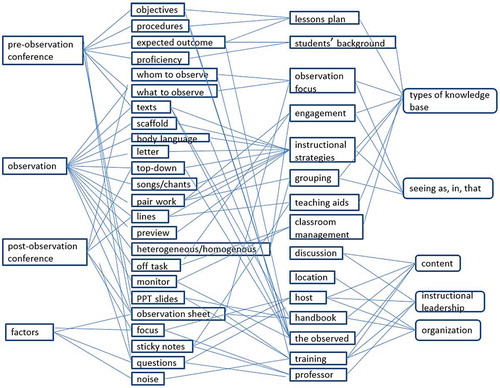

All observations, pre-observation conferences, post-observation conferences, and interviews were transcribed verbatim, and these transcriptions were reviewed by four teachers from each observation setting. Data were labeled, for example, as objectives, procedures, etc. The data were read several times in order to find commonly emerging themes. The themes were listed and then grouped into similar categories. The categories (e.g. lesson plans, students’ background) that emerged were used for the analysis of the data. Finally, the categories were sorted based on the research questions, such as, types of knowledge-base or “seeing in” as in Figure .

4. Results and analysis

Based on the research questions, the results and analysis of the study are discussed in terms of participants’ professional learning from pre-observation conferences, observations, post-observation conferences, and other factors (i.e. location, host).

4.1. Professional learning from pre-observation conferences

At the pre-observation conference stage, participants reported that they gained the most professional learning from “objectives and teaching procedures of the lesson” (n = 8), followed by “observational focus” (n = 6). Other professional learning included “students’ background,” (n = 2), “class atmosphere” (n = 1), and “instructional materials” (n = 1). Of all different knowledge base coined by Shulman (Citation1987), participants gained knowledge about general pedagogical approaches, curriculum development, pedagogical content, and knowledge of the learners and their characteristics.

Dale said, “I clearly knew students’ learning conditions, the curriculum structure, and classroom atmosphere. I also knew how to observe the class.” In the observation note #1, Ann briefly described her physical condition, students’ learning and performance, her lesson, objectives, and activities. Observed teachers, such as Ann, are given the opportunity to explain their decision-making and to provide a rationale for why they did what they did in the classroom.

Observation note #1:

Welcome to Ann’s teaching demonstration. First, Ann will briefly explain her lesson.

I lost my voice today, so I may have trouble controlling the lower graders. My students cannot do group work. We have done group work before but they began to have fun instead of learning, so I will not use a learner’s learning community today. Today’s teaching is more teacher-centered. The objective of the lesson is on recognition of words and alphabet letters. In this lesson, you will not see games, only activities.

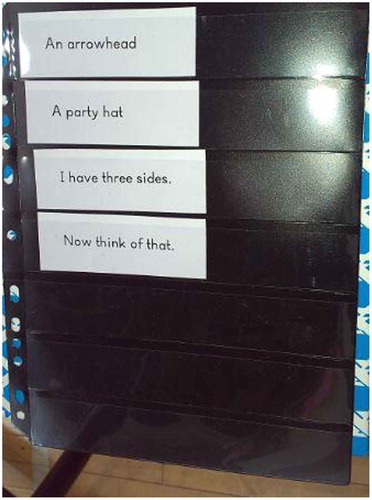

In the pre-observation conference, while the teacher being observed introduced the teaching procedure, participants could read through the lesson plan provided in the handbook (as shown in Figure ). One observer claimed that she did not clearly know what the learning outcomes would be from the pre-observation conference. Lena said, “I was curious about the learners’ academic performance before and after this lesson. The teacher did not explain what she did before this lesson and her expected learning outcomes.”

4.2. Professional learning from observation

At the observation stage, participants reported that they gained the most professional learning from “instructional strategies” (n = 9), followed by “students’ engagement in class activities” (n = 6) and “the interaction between the teacher and students or among students” (n = 4). Other learning included “teaching aids” (n = 2), “seating arrangement” (n = 1), “teaching aids and tiered assignments” (n = 1). With regard to the knowledge-base, participating teachers acquired general pedagogical knowledge and PCK.

With respect to instructional strategies, Fay reported, “I taught alphabet letters to lower graders. I learned a new idea to use top-down to teach alphabet letters. I can use songs and chants to teach alphabet and word recognition.” Fay demonstrated her “seeing as” because she identified the differences and similarities in alphabet instruction between her methods and Ann’s. She also demonstrated her “seeing in” because she developed the practical wisdom of integrating top-down instruction and songs and chants into the teaching of the alphabet. However, she did not demonstrate “seeing that” because she did not interpret the alphabet instruction beyond her own and Ann’s instruction.

The following observation note is related to Ann’s alphabet instruction using the chant “Rain, Rain, Go Away.”

Observation Note #2: Ann’s chant instruction

Take out your worksheets. Finger point each word. Ready, go. Rain, rain, go away.

(Finger point) Rain, rain, go away.

Circle the word “away.”

(Circle the word away).

(Point to a) Is this a big or small a?

Small.

(Point to w) Have we learned this letter before?

No.

Repeat after me “w” ([ˋdʌblju]).

“w” ([ˋdʌblju]).

Show me your fingers.

(Raise their hands).

Let’s write “w.”

(Write w).

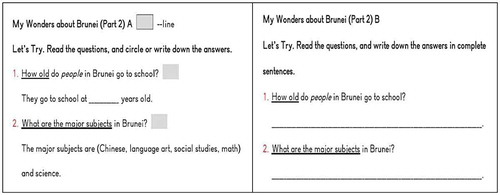

Nora noted that, “The teacher used two types of worksheets. Students with lower proficiency levels can practice English by circling the words. Advanced learners could also learn. The teacher let students discuss with their homogeneous groups first and then in heterogeneous groups.” Figure is an example of a tiered assignment. Whilst A, on the left, is for students with lower proficiency levels, B is for the advanced learners. Nora demonstrated her “seeing as” because she identified the differences in Vic’s instruction by using tiered assignments.

Cara said, “From Elva’s teaching demonstration, I found that the inner pages of stamp booklets could be a good teaching aid, so I went out and purchased them immediately and used them in sentence teaching. I observed Gill’s students using highlighters to mark the important points and answers, so I implemented this strategy in my next class.” Figure is an example of an inner page of a stamp booklet. Cara demonstrated “seeing in” because she developed practical skills in adopting different teaching aids and instructional strategies in her own classroom practice that she had observed in the teaching demonstration.

As for learners’ interaction and engagement, Alice observed that four students discussed the past tense in their small groups. They asked one another “‘Is this a verb?’ ‘How many verbs are there?’” Joy shared her observation, “Students were on task and quiet. They practiced reading through different activities.” Both Alice and Joy shared their observations but they did not demonstrate “seeing as,” “seeing in” or even “seeing that.” Alice and Joy’s remarks revealed that they understood the teachers’ instructional strategies and knew how to teach these kinds of lessons, but nothing new happened.

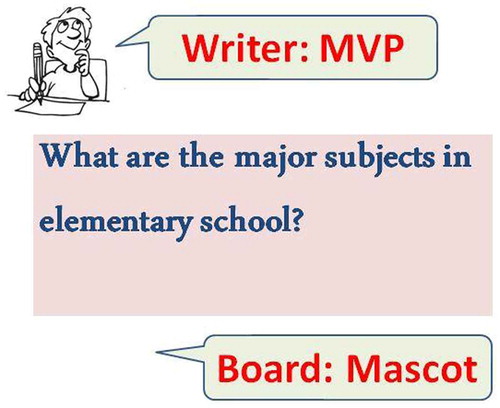

Observation note # 3 reveals the interactions in students’ group discussions. Vic asked students to read the question from the PowerPoint slide as shown in Figure . In groups, students first discussed the answer. The most valuable player (MVP) was assigned to write the answer on the worksheet and the Mascot was asked to attach the answer to the board and share it with the whole class.

Observation Note #3: Vic’s instruction on my wonders about Brunei:

(Shows the PowerPoint slide) Please read the first question together.

What are the major subjects in elementary school?

Chinese

(Writes Chinese)

English

(Writes English)

math

(Writes math)

Observation #4 is Elva’s instruction to her students in the form of a poem. Student A in group 1 dominated the group activity and the rest of the students did nothing.

Observation Note #4: Elva’s poem instruction

(Gives students sentences and an inner page of a stamp booklet) A pizza, a clock

(Puts the sentence, A pizza, a clock, on the first row of the inner page of the stamp booklet)

(Look at the sentences)

A bicycle wheel

(Puts the sentence, A bicycle wheel, on the second row of the inner page of the stamp booklet)

(Look at the sentences)

Responding to this demonstration, Mary said, “The teacher and the students had no tacit understanding. She was not clear about the learners’ English proficiency levels. She used the new genre ‘poem’ to teach a new concept ‘shape.’ Students were static. Students were not engaged in discussion in the first thirty minutes. Students had no sense of security and did not share their ideas.” Mary demonstrated her “seeing as” when she compared the similarities and differences between Elva’s instruction and her expectations of interactions between learners and teachers as well as among learners.

4.3. Professional learning from post-observation conferences

The participants gained most professional learning from discussion in the post-observation conferences on “instruction strategies” (n = 10), followed by “classroom management issues” (n = 7). As for the knowledge-base, participating teachers obtained both general pedagogical knowledge and PCK from the post-observation conferences.

Observation #5 focused on group discussions of Ann’s alphabet instruction. Mary identified Ann’s strengths in her interaction with the learners. Lena also talked about the warm-up activities in Ann’s class. Both Lena and Ruby had the same question about using the lines used for alphabet instruction. Ruby said, “At first I thought, why did Ann not ask students to write the alphabet on the four lines. The professor had the same doubts like me. But she changed her mind because the purpose of writing the alphabet was for recognition and practice, not for accuracy. I like the professors’ comments and suggestions on alphabet instruction. I will try the instructional strategies provided by Ann and the professors.”

Observation Note #5: Group discussion of Ann’s alphabet instruction

I saw a lot of interaction between the teacher and students. Ann used gestures to show “good” and students expected her signals. First graders were willing to be engaged in class activities.

I agree with you. My first wow was the students were led to recite alphabet letters and finger point. Students were ready for the class. The teacher monitored the whole class. I have one question, “Why did Ann ask students to write the alphabet letters on four lines?”

I had the same question, too.

Maybe our group can ask her this question.

Lena and Ruby demonstrated their “seeing as” by identifying the similarities and differences about the alphabet instruction, classroom management strategies, and general content knowledge between Ann’s instruction and their expectations or experience.

With regard to classroom management strategies, Zara said, “Our group discussion focused on students’ learning, particularly those who could not concentrate in class. We discovered Ann monitored in class, gave stickers to students who were on task, signaled students to take out worksheets from the drawer, etc. She tried to help students but it was hard to take care of all thirty students. First graders are easily put off task.” Zara demonstrated her “seeing as” by comparing and contrasting Ann’s group members with her own teaching experience of classroom management.

Bess commented, “In my group discussion, I asked questions about the seating arrangement, grouping, and students’ engagement in group discussion.” Observation 6 refers to the discussions about Gill’s reading instruction.

Observation Note #6: Discussion of Gill’s reading instruction

Students did not talk very loud in group discussion. They did not have loud voices.

I noticed this too.

In my class, I have voice volume signals. Students know when and what voice volume they should use. They do not talk very loud, but freely and calmly.

I also wonder how the advanced learners are willing to work with low achievers.

I do not want to label students. My students are given four different roles: coach, MVP, GM, and Mascot. When the coach answers the question correctly, he/she gets one point. When the GM answers the question correctly, he/she gets two points. They try to help one another in small groups.

4.4. Major factors in the three-step teaching demonstration

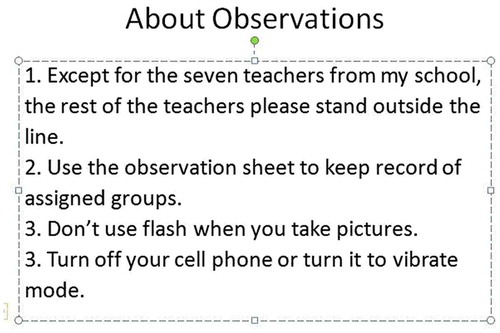

Six major factors were identified for effective three-step teaching demonstrations. First was the provision of handbooks and PowerPoint slides. Joy commented, “During the pre-observation conference, the handbook and PowerPoint slides clearly told me where I should stand, what I should observe, whom I should observe, and tips on observation.” Figure is an example of PowerPoint slides in observation notes. However, Tess looked at the observation sheet provided for Ann’s teaching demonstration and said, “There are too many items for us to take notes. I think the observation sheet should be simplified.”

Second, the way that the hostess led the three-step teaching demonstration was another factor. The hostess’s strengths, identified by the participants, included “focus” (n = 4), “guided questions” (n = 3), “supplementary materials” (n = 3), “summary of the discussions” (n = 2), “provision of the theoretical framework” (n = 2), and “grouping and teachers” (n = 2). Therefore, in general, the hosts or the hostesses are school leaders such as principals, administrators, or teacher leaders.

Vic reflected on his own experience: “The professor’s guided questions and the teachers’ questions led me to reflect on my practice. Were my students too quiet? How was their performance different from the regular classroom?” Mary said, “The hostess’s (the professor) guided questions were crucial because these questions helped us to focus on our observation and group discussion.”

Joy commented, “I like to have the professor (the hostess) in the post-observation conference because she used theories and curriculum frameworks to analyze the teaching and gave different comments.” Figure contains a list of the guide questions proposed by Dr Chen for Elva’s post-observation conference.

Cara responded to the use of guidance questions by saying that, “The hostess clearly identified the areas for discussion and reflection, so we had a focus for the group discussion.” Sara said, “The hostess summarized the main ideas from each group’s discussion and shared these by using small whiteboards and sticky notes. I am a visual learner, so such visual presentations helped me a lot.” In observation 7, Dr Chen summarized Cara’s main points and posted a question for the teacher.

Observation Note # 7: Post-observation conference

I am from Group 3. Our group conducted an observation of one girl. At the beginning of the class she went to other groups to talk to other kids. Elva did not stop her behavior. During the group discussion that girl made a mistake. The rests of the group members dared not correct her but they refused to accept her answer either.

Your group’s question is about classroom management. (Write down “classroom management” on a sticky note). How should the teacher correct students’ behavior and monitor the whole class, too? (Write down “correction” and “monitor” on the same sticky note).

Yes.

In group discussions, participating teachers in this study did not play different roles as revealed in Table (Tzotzou, Citation2014). They mainly shared their observations and questions about the observation. Instead, the hostess in this study played the roles of initiator who triggered discussion by asking key questions, conductor who fostered group discussions among participating teachers, informant who provided the theories behind curriculum development, and counselor who made comments or suggestions.

A third factor concerns the way in which the observed person introduced his or her lesson plans and teaching procedure during the pre-observation conferences and how s/he responded to the observers’ questions. Cara remarked that, “After the group discussion and sharing, the teacher (the observed) responded to each question, so our doubts could be clarified.” Zara also said, “Ann answered all our questions. She shared what she had done before, the problems she faced and the modifications she had made. This kind of sharing is crucial.” Elva reflected on her own experience by saying, “I asked myself how I could explain my teaching by using bullet points so that teachers could clearly understand my lesson and get ready for the observation.”

A fourth factor that influenced English teachers’ professional learning relates to the discussions that take place during the pre- and post-observation conferences. Alice said, “I enjoy having discussion with teachers from different schools with different expertise and competence.” Fay said, “Group discussion was great. If only certain teachers shared their ideas, the discussion would be narrow. Teachers discussed in the small groups and shared their findings with all the teachers. The discussion was in-depth and broad.” Observation notes 5 and 6 are examples of group discussions.

Fifth, the location was another important factor. Ann complained about the location as “The pre- and post-observation conferences were held in an auditorium. It was noisy.” Lena was also critical stating, “Never hold the conferences in the auditorium. It was too noisy. I could hardly hear the hostess, the observed, and other teachers.”

The sixth factor was that participants thought that training workshops should be provided for teachers to help them to learn how to observe and discuss. Elva suggested, “English teachers should be trained to observe and discuss. The comments given by teachers who do not know how to observe and discuss are useless.” Ann also said, “English teachers should practice discussing the lessons with other English teachers so they will not be confined to a one-way discussion.” Moreover, English teachers should spend more time planning lessons.

5. Discussion

Based on the above data analysis of documents, interviews, and observations, this study reports the following major findings. With regard to the first research question—What did elementary school English teachers gain in terms of their professional learning and the development of their reflective skills from the teaching demonstration?—participating teachers gained general pedagogical knowledge and PCK from the three-step teaching demonstrations, particularly, instructional strategies and classroom management. During the pre-observation conferences, the observers’ understanding of the contextual information of the observation can make the observation meaningful and successful (Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009).

During the observation, the “seeing as” observations help teachers such as Nora in this study to learn from observation and to improve their competence by drawing similarities and differences between their classroom practice about mixed-level classes, their understanding of theories, and their observed action (Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009). Moreover, “seeing as” helps teachers like Mary to see teaching practices that are already familiar to them during their observation. Teachers’ sense-making can be directed and constructed by their assumptions about classroom management (Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009).

When English teachers observe particular classrooms and lessons, the “seeing in” observations can help them to gain perceptual and practical skills. They can gain these practical skills in terms of instructional strategies, activities, and classroom behavior (Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009). However, teachers like Alice and Joy in this study, may not see beyond their perceptual level and connect their observation to their past teaching experience and conceptual level (Kvernbekk, Citation2000; Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009).

During the post-observation conferences, “seeing as” allows teachers and practitioners such as Lena and Ruby in this study to have awareness of new teaching problems and scenarios, therefore, this can become a form of observation that goes beyond their sensory perception (Kvernbekk, Citation2000). Moreover, teachers, like Zara, can make sense of their observation by identifying similarities and differences between their own teaching experiences and classroom practice and the newly observed instructional practice. Such “seeing as” can be recognized and judged against previous teaching experience and competence. (Kvernbekk, Citation2000; Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009).

With regard to the second research question—How did elementary school English teachers gain professional learning and develop reflective skills from the teaching demonstration?—six major factors influenced teachers’ professional learning including the use of handbooks for observations, the host or hostess’s expertise, the observed teachers’ expertise, the observers’ discussions, location, and training workshops. In terms of instructional leadership, the hosts or hostess must be familiar with the instructional standards, the procedure of the three-step teaching demonstration process, observation focuses, observation sheets, and tasks. Moreover, they should also lead productive discussions with teachers and create a learning environment that supports teachers’ professional development (Goe et al., Citation2012).

In order to identify the gap between observation and teachers’ own classroom practice, as well as to explicitly explain what teachers have learned, Orland-Barak and Leshem (Citation2009) suggest that guided questions or prompts should be provided for teachers. They suggest examples such as, “I was surprised to discover that … because I had initially thought that …” (pp. 32–33). Kvernbekk (Citation2000) argues that observation is primarily a theory-laden undertaking. Teachers’ observations should move beyond “seeing as” and “seeing in.” Teachers should be able to use the theories to observe, so that they will be able to recognize the instruction practice beyond the single case. By so doing, they can be aware of the differences between perceptions and make theoretical and pedagogical judgments. The observed teachers must learn to communicate clearly with the other teachers during the pre-observation and post-observation conferences (Goe et al., Citation2012). Language teachers should also be able to explicitly articulate their knowledge and competence about learning and learners (e.g. language learning development), content knowledge, or instructional practice (e.g. assessment, lesson planning (Goe et al., Citation2012; Shulman, Citation1987).

Discussions during the post-observation conferences provide good opportunities for effective feedback and reflective practice for teachers. In this collaborative learning environment teachers are encouraged to respond to one another and to interact. Through peer support and companionship, teachers can collaboratively encounter knowledge of learning theories, experiment with them, and reflect on their effectiveness (Tzotzou, Citation2014).

Moreover, the physical feature of the location affects the effectiveness of the pre- and post-observation conferences. The ideal location should be a private and quiet setting (Ovando & Harris, Citation1993). Finally, effective training is essential for teachers. Teaching standards, procedures of observation, observation tools and focus, and recording of the evidence should be introduced into the training. Through the training, both the observed teachers and the observers will gain a better understanding of the purpose and expectations of the three-step teaching demonstration process (Goe et al., Citation2012).

The conceptual framework, shown in Figure , provided guidance for analyzing elementary school English teachers’ professional learning through the three-step teaching demonstration process. Second, the focus of observation and contextual information about learners and classroom atmosphere was provided in the pre-observation conference. Third, a clear observation focus and observation sheet facilitated participating teachers during their observation. English teachers demonstrated more “seeing as” than “seeing in,” but they did not demonstrate “seeing that.” Moreover, no specific observation tasks were provided in these four teaching demonstrations. Observers provided both confirmatory and constructive feedback during the post-observation conferences. However, participating teachers did not play different roles, but the hostess played the roles of an initiator, controller, informant, and conductor. Finally, the hostess guided questions and led the discussion about teachers’ effectiveness during the observed lesson and the post-observation conference.

Based on the above data analysis, Figure is revised and reformulated in Figure . The location, the atmosphere, the observed teachers and observers’ knowledge and competence, as well as the instructional leadership of the host or hostess, influence the elementary school English teachers’ professional learning through the three-step teaching demonstration. The discussion below considers the importance of teaching demonstrations for teachers’ professional learning and focuses on four issues: the’ observation as seeing beyond; elements of workshops and training for teaching demonstrations; the selection of appropriate locations and the fostering of a respectful atmosphere; and the hosts or hostesses’ instructional competence and leadership.

5.1. Importance of teaching demonstrations for teachers’ professional learning

The traditional professional development model is the transmission model which regards learning as the acquisition of knowledge and skills where theoretical knowledge is passed down from educational experts to teachers who then apply this knowledge in their classrooms (Johnson & Golombek, Citation2011). Traditional workshops and professional development do not affect teachers’ classroom practice because teachers are not involved in selecting the topics for their own professional development. Moreover, it is difficult for teachers to transfer what they have learned from outside experts in the workshops into their classroom practice. Furthermore, teachers are not given opportunities to practice and refine their instructional strategies in the limited time available in the workshops (Borko, Citation2004; Feiman-Nemser, Citation2001; Grimm et al., Citation2014; Richardson, Citation2003).

Observations and the three-step teaching demonstrations address the limitations of traditional professional development. They can empower teachers and refine their teaching practice through gathering and analyzing classroom data. The observed teacher is placed as the leader and primary learner in the observation process (Grimm et al., Citation2014). The three steps of the teaching demonstration—pre-observation conferences, observation, and post-observation conferences—can be used as part of teachers’ continuous professional development because they provide an excellent opportunity for teachers to share effective classroom practice, to share learning and collaborative development, to develop particular or innovative teaching techniques, skills or methods, or to construct competences together with other teachers within a professional learning community (Estyn, Citation2014; Harper & Nicolson, Citation2013).

5.2. Observation as seeing beyond

Observation should not be limited to “seeing only” or “seeing as” but “seeing in” and even “seeing that.” Kvernbekk (Citation2000) argues for “helping them learn to see beyond what everyone sees; to widen their vision and make it more flexible through seeing with theory” because “seeing is … learned in practice” (pp. 369–370). Observations should be structured and organized in order to encourage teachers to identify the gaps between what they have been, and their assumptions, as well as to articulate the gaps in their professional learning. Therefore, in order to challenge teachers’ insights, Orland-Barak and Leshem (Citation2009) call for contextualized questions and prompts to be used to assist teachers to identify different or similar gaps across various observed scenarios. From the observations, these questions and prompts can help to raise teachers’ awareness of their deficiencies.

5.3. Elements of workshops and training for teaching demonstrations

Observations can be used as effective professional development for teachers when they are trained with the skills of classroom observation and competence in giving professional and effective feedback on the observation (Estyn., Citation2014). A training model should be designed to prepare teachers for observations. First, during the pre-observation phase, teachers should have hands-on experience with various observation and conferencing techniques through reading articles or watching videotapes of classroom observations (Carroll & O-Loughlin, Citation2014; Danielson, Citation2011; Tzotzou, Citation2014). When teachers and colleagues have been exposed to the issues related to observation and established a friendly and trusting relationship, they can begin the observation process. Second, they have to set the goals of observation and develop an observation schedule (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009). They should also select the observation instruments or protocols and become familiar with them (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009). The observed teachers should also provide a classroom map and observation form outlining their teaching methodology, materials, or activities (Tzotzou, Citation2014; Williamson & Blackburn, Citation2009). The observed teacher should practice clearly describing the classroom map and form.

During the observation, the observed teacher delivers the lesson and the observers complete the observation sheet. During the post-observation phase, participating teachers can be trained to play different roles, as noted in Table (Tzotzou, Citation2014). The teacher and observers can be trained to discuss the predetermined areas of interest regarding the delivery of the lesson through guided questions and prompts (Orland-Barak & Leshem, Citation2009; Tzotzou, Citation2014). At the end of the process, the trainer can review the discussions and identify behaviors for reflection and improvement (Tzotzou, Citation2014).

5.4. Selections of appropriate locations and fostering a respectful atmosphere

Ovando and Harris (Citation1993) study found that the preferred location for holding pre-observation conferences, observations and post-observation conferences was the teacher’s own classroom. Since the physical and psychological features of the location affect the effectiveness of these activities, this location must be in a private, quiet, and comfortable setting. From a psychological perspective, the pre-observation and post-observation conferences should take place in a positive, non-threatening atmosphere. The environment must be respectful, too. Teachers prefer to discuss their observations in a collegial, informal, but professional atmosphere (Ovando & Harris, Citation1993).

5.5. Hosts’ or hostesses’ competence and instructional leadership

In this study, the hosts’ or hostesses’ competence and instructional leadership, particularly on guided questions, was identified as one of the factors that influenced the participating teachers’ professional learning during the pre- and post-observation conferences. Therefore, the hosts or hostesses can serve as leaders who facilitate communities of learning where knowledge and competence is discussed and constructed in order to enhance learners’ learning (Crowther, Ferguson, & Hann, Citation2009). These teacher leaders can work collaboratively with their colleagues to develop clear classroom observation policies and practices that all staff understand and apply. They engage in professional dialog with teachers after the observation (Estyn., Citation2014). Teacher leaders’ interaction with their colleagues and with external experts or professors increases their engagement in reflective practice and reinforce and develop content knowledge and pedagogical skills. Teachers work together via the three-step teaching demonstrations: planning instruction, discussing the observation, and analyzing students’ work or behavior. Such job-embedded, collaborative learning experience gives teachers ownership and receives built-in support (Collay, Citation2011; Hunzicker, Citation2012).

6. Conclusion

This study has used interviews, observations and documentary evidence to analyze the professional learning of sixteen elementary school English teachers and two expert teachers during the pre-observation conference, observation, and post-observation conference from three-step teaching demonstrations. The study has the following major findings. First, the knowledge and competence that participants gained the most, was pedagogical knowledge and PCK. Participants demonstrated “seeing as” and “seeing in” during observations but not “seeing that.” Second, six major factors were identified that influenced elementary school English teachers’ professional learning. These included handbooks for the observation, the host or hostess’s instructional leadership, the observed teachers’ expertise, the observers’ discussions, the location of pre- and post-observation conferences, and the provision of workshops prior to the three-step teaching demonstration. These findings provide a theoretical framework and guidelines for elementary school English teachers to gain professional learning through the demonstrations. Such a framework can be recommended for language teacher education and for the educational organization of in-service elementary school English teachers’ professional development.

This study has two major limitations. First, data in this study included documents, interviews and observation fieldnotes. The observers’ notes on observation sheets or handbooks were not available because the observation sheets were compiled for the observed teachers’ personal reflection and for the schools’ records. However, the triangulation of this data could still explore elementary school English teachers’ professional learning through the three-step teaching demonstrations.

Second, the study was conducted during four teaching demonstrations held in large and urban elementary schools in the northwest of Taiwan. No data was collected from elementary schools in rural or remote areas. For a potential further research study, elementary school English teachers’ professional learning could be investigated using larger samples from schools of different sizes and locations. This could result in developing an effective framework for teachers to gain professional learning through the three-step teaching demonstrations.

Third, three of the hosts and hostesses in these four three-step teaching demonstrations were colleagues in the same school and the teacher’s learning community. Their instructional leadership varied due to their different teaching experience and expertise. These hosts and hostesses are called upon to become the teacher leaders during the three-step teaching demonstration. Their responsibilities include creating conditions of trust that promote dialog, affirming the observed teacher’s strengths, assisting the observed teachers in identifying areas of instruction that need improvement, guiding the observers to be familiar with the observation process, tools, and tasks, and encouraging reflection among the teachers (Zepeda, Citation2012). A further study could explore the influence of the hosts or hostesses’ instructional leadership on elementary school English teachers’ professional learning from the pre- and post-observation conferences.

Funding

The author received no direct funding for this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chin-Wen Chien

Chin-Wen Chien received her Doctor of Education degree from the University of Washington (Seattle, USA). She is an associate professor in Department of English Instruction of National Tsing Hua in Taiwan. Her research interests include language education, language teacher education, and curriculum and instruction.

References

- Akbari, R. , Samar, R. G. , & Taijk, L. (2006). Developing a classroom observation model based on Iranian EFL teacher’s attitude. Journal of Faculty of Letters and Humanities , 49 (198), 1–37. Retrieved from http://www.sid.ir/en/VEWSSID/J_pdf/874200619801.pdf

- Akcan, S. , & Tatar, S. (2010). An investigation of the nature of feedback given to pre-service English teachers during their practice teaching experience. Teacher Development , 14 , 153–172.10.1080/13664530.2010.494495

- Barocsi, S. (2007). The role of observation in professional development in foreign language teacher education. WoPaLp , 1 , 125–144. Retrieved from http://langped.elte.hu/WoPaLParticles/W1Barocsi.pdf

- Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher , 33 , 3–15. Retrieved from https://cset.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/files/documents/publications/Borko-Professional%20Development%20and%20Teacher%20Learning.pdf 10.3102/0013189X033008003

- Carroll, C. , & O-Loughlin, D. (2014). Peer observation of teaching: Enhancing academic engagement for new participants. Innovations in Education & Teaching International , 51 , 446–456.10.1080/14703297.2013.778067

- Collay, M. (2011). Everyday teacher leadership: Taking action where you are . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Crowther, F. , Ferguson, M. , & Hann, L. (2009). Developing teacher leaders: How teacher leadership enhances school success . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Danielson, C. (2011). Evaluations that help teachers learn. Educational Leadership , 68 , 35–39. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/dec10/vol68/num04/Evaluations-That-Help-Teachers-Learn.aspx

- Day, R. , & Conklin, G. (1992). The knowledge base in ESL/EFL teacher education. Paper presented at the 1992 TESOL Conference , Vancouver.

- Estyn . (2014). Effective classroom observation in primary and secondary schools . Cardiff: Author.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strength and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record , 103 , 1013–1055. Retrieved from http://www.brandeis.edu/mandel/questcase/Documents/Readings/Feiman_Nemser.pdf 10.1111/tcre.2001.103.issue-6

- Fradd, S. H. , & Lee, O. (1998). Development of a knowledge base for ESOL teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education , 14 , 761–773.

- Freeman, D. , & Johnson, K. E. (1998). Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly , 32 , 397–417.

- Glisan, E. (2002). New directions: K-12 foreign language teacher preparation. Basic Education , 46 , 8–12.

- Goe, L. , Biggers, K. , & Croft, A. (2012). Linking teacher evaluation to professional development: Focusing on improving teaching and learning . Denver, CO: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

- Grimm, E. D. , Kaufman, T. , & Doty, D. (2014). Rethinking classroom observation. Professional Learning: Reimagined , 71 , 24–29. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may14/vol71/num08/Rethinking-Classroom-Observation.aspx

- Harper, F. , & Nicolson, M. (2013). Online peer observation: its value in teacher professional development, support and well-being. International Journal for Academic Development , 18 , 264–275.10.1080/1360144X.2012.682159

- Hunzicker, J. (2012). Professional development and job-embedded collaboration: How teachers learn to exercise leadership. Professional Development in Education , 38 , 267–289.10.1080/19415257.2012.657870

- Jang, S. J. (2008). The effects of integrating technology, observation and writing into a teacher education method course. Computers & Education , 50 , 853–865.10.1016/j.compedu.2006.09.002

- Johnson, K. E. (2006). The sociocultural turn and its challenges for second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly , 40 , 235–256.

- Johnson, K. E. , & Golombek, P. R. (2011). The transformative power of narrative in second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly , 45 , 486–509.

- Kang, Y. , & Cheng, X. T. (2014). Teacher learning in the workplace: A study of the relationship between a novice EFL teacher’s classroom practices and cognition development. Language Teaching Research , 18 , 169–186.10.1177/1362168813505939

- Kurtoglu-Hooton, N. (2004, July). Postobservation feedback as an instigator of teacher learning and change. International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language TTED SIG E-Newsletter . Retrieved from http://www.ihes.co/ttsig/resources/e-newsletter/FreatureArticles.pdf

- Kvernbekk, T. (2000). Seeing in practice: A conceptual analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research , 44 , 358–370.

- Lam, S. F. (2001). Educators’ opinions on classroom observation as a practice of staff development and appraisal. Teaching and Teacher Education , 17 , 161–173.10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00049-4

- Ministry of Education . (2014). 1–12 National basic education curriculum guideline . Taipei: Ministry of Education.

- Morain, G. (1990). Preparing foreign language teachers: problems and possibilities. ADEFL Bulletin , 21 , 20–24.

- Orland-Barak, L. , & Leshem, S. (2009). Observation in learning to teach: Forms of “seeing”. Teacher Education Quarterly , 36 , 21–37.

- National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). (2008). Professional standards for the accreditation of teacher preparation Institutions . Washington, DC: Author.

- Ovando, M. N. , & Harris, B. M. (1993). Teachers’ perceptions of the post-observation conference: Implications for formative evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education , 7 , 301–310.10.1007/BF00972507

- Richards, J. C. , & Farrell, T. S. C. (2011). Practice teaching: A reflective approach . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139151535

- Richardson, V. (2003). The dilemmas of professional development. Phi Delta Kappan , 84 , 401–406.10.1177/003172170308400515

- Richards, J. (1998). The scope of second language teacher education. Beyond training: Perspective on language teacher education (pp. 1–30). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Roberts, J. (1998). Language teacher education . London: Arnold.

- Salas, S. , & Mercado, L. (2010). Looking for the big picture: Macrostrategies for L2 teacher observation and feedback. English Teaching Forum , 48 , 18–23. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ923467

- Shah, S. R. , & Harthi, K. A. (2014). TESOL classroom observations: A boon or a bane? An exploratory study at a Saudi Arabian University. Theory and Practice in Language Studies , 4 , 1593–1602.

- Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of new forms. Harvard Education Review , 57 , 21. Retrieved from http://people.ucsc.edu/~ktellez/shulman.pdf

- Stillwell, C. (2008). The collaborative development of teacher training skills’. ELT Journal , 63 , 353–362.

- Sweeney, J. (1983). The post-observation conference: Key to teacher improvement. High School Journal , 66 , 135–140.

- Tzotzou, M. D. (2014). Designing a set of procedures for the conduct of peer observation in the EFL classroom: A collaborative training model towards teacher development. Multilingual Academic Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 2 , 15–27. Retrieved from http://blogs.sch.gr/mtzotzou/files/2015/02/MY-MAJESS-ARTICLE-SOS.pdf

- Wajnryb, R. (1992). Classroom observation tasks: A resource book for language teachers and trainers . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Williamson, R. , & Blackburn, B. (2009). One teacher at a time. Principal Leadership , 9 , 44–47.

- Yates, R. , & Muchisky, D. (2003). On reconceptualizing teacher education. TESOL Quarterly , 37 , 135–146.

- Zepeda, S. J. (2012). Informal classroom observations: On the go . Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.