Abstract

Suffering of the underachievers and misdiagnosed cases brought a group of educators at Srinakharinwirot University to start a pilot project in 1980. This project led to the discovery of many issues on identification, programming, and school evaluation among experts. Questions raised from parents and teachers were in need of the right answers. Thus, many attempts have been made under the limitation of support and understanding on the needs and problems of the gifted. Rights of the gifted in education were assured for the first time by the Educational Act in 1999. Many pieces of research, fieldworks, and handbooks have been developed to enhance teachers and parents of the gifted after 1980. Although special programs and special schools have been established across the country for decades, a lot of work is still required in order to blend a supportive system into the formal education effectively: identification instruments, personnel training, research and development, including the integration of traditional wisdom into formal education.

Keywords:

Public Interest Statement

Providing appropriate service for the gifted is always a challenge in every country, due to the complication of human intelligence. Transforming from the traditional education to meet the needs of such a heterogeneous group as the gifted is not an easy task, especially within an inflexible educational system. While programs for the gifted require effective identification and enhancement, but resources, supports, and understanding seem to be limited in Thai’s society. Experiences from conducting research and development to create learning opportunities for those who have overweight mind and intelligence presented in this paper have contributed to many different solutions in the field of education for the gifted in the country. Many efforts of the experts in different fields have discovered ways to ignite and nurture their potentials in order to use their giftedness for their society and the world.

1. Introduction

“Investments in social capital benefit society as a whole because they help to create the values, norms, networks, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation geared toward the greater public good” (Renzulli, Citation2003, p. 77). Development of education for the gifted is usually connected with the development of social demand and social capitals. Investment and support in each period is different depending upon the social values and social demand at that time. The development of Thai gifted education is also related to works of Thai predecessors and various cultures.

Education for the gifted in Thailand has been transformed along the changes of different factors related with social demands and social capitals in the country. Key factors that underpin the intellectual roots of the country and the conceptions and education of giftedness in the Thai culture need to be understood from a number of perspectives, including the development of the Thai history and its juxtaposition with the outside world (Anuruthwong, Citation2007). This paper will discuss the following issues: historical background related to the development of giftedness, social value, conceptions of giftedness and belief toward giftedness, developing the gifted, difficult issues in providing programs and services for gifted learners, the most important act and research contributions to gifted education that have been made in the country in the Thais’ view. The future directions for research and program development are also included in the paper.

2. Historical background related to the development of giftedness

Thailand is located between India and China. The topography of the country made it an important route for trade for over a thousand years. Many aspects of activities were impacted. The Thais have developed, adopted, and absorbed civilizations from various cultures: Chinese, Indian, Persian, Arabian, and European. Chinese civilization has played an important role in politics and trade, while that of India has had a strong influence on cultural aspects such as religion, performing arts, and language (Anuruthwong, Citation2007).

Most of the Thai creations are related to Buddhism and monarchy: arts, architecture, poetry, spiritual activities, literature, agriculture, and the way of life. Other abilities had been developed from being at the cross-road: multi-language abilities, translation, and international trading system, social skills, diplomatic skills, and other-related activities. Knowledge and wisdom were offered in temples, Royal Palaces and in their families as an informal education. The gifted in those areas were selected by keen persons for particular tasks with the supports of the royal families and Buddhist temples around the country (Anuruthwong, Citation2007, Citation2013).

Thai educational system significantly changed twice:

The first time was after the early of 1900s. The Thai traditional way of selecting and training a person became a new way of education called “modernization”. Like many countries around the world, local wisdom and Thai traditional knowledge were replaced by western knowledge. Many new occupations formed the major economic structure, such as lawyer, physician, economist, engineer, teacher. The modernization had a significant impact on the present life of people in Thailand (Association of South East Asian Nations, Citation2000). Good students were selected as the gifted by teachers from their achievement in school instead of experts or specialists from the palaces or from their communities. Values, conception, and belief of giftedness gradually shifted from the original culture to the western aspect. With the new educational system, social values and supportive systems, including the expectations toward the younger generation, have also changed (Anuruthwong, Citation2007).

The second time was near the end of the twentieth century when the change of the educational system took place under the influence of new technology, rapid growth of population, and new economic system. These factors played an important role in changing the world into the new era of human history—“Globalization”. Demand of society on human resources has significantly turned into a new system. There is a great need to develop a new education for “global community” in an increasingly interdependent world. The Global community has a direct impact on human resource preparation (Anuruthwong, Citation2007, Citation2013).

During the 1970s–1990s, a handful of research and evidence from field works indicated that the traditional formal education misfit the nature of human learning and new social demands, especially to those students who needed special care. Many children were misdiagnosed from “the one size fits all concept”. The numbers of children deviated from the norm because of their intelligence, physical condition, brain functioning, mental condition, language barrier, different culture, or poverty. Assessing children’s potentials or problems required appropriate instruments by specialists. Mismeasurement in children with special needs was often found due to the lack of both instrument and specialist. Results from IQ testing and grade point average (GPA) were used as cut-off criteria for diagnosis or judgment in many situations (Anuruthwong, Citation2011; Center for the Gifted/Talented, Citation2000; The Office of the National Education Commission, Citation1998; The Office of the National Primary Education, Citation2000).

Moreover, The Office of the National Primary Education (Citation2000) stated that many educators and parents of gifted and talented students apprehended that educational services provided in schools and outside of schools were inappropriate for the students. The ONPE also affirmed that there was evidence of highly gifted students dropping out of schools. Some students who were placed in a program for the gifted realized that their interest and real potentials were not met and decided to withdraw from the program. Feedback from former students who stayed until the end of the program seemed to be successful, for example, they graduated from top 10 universities or world class universities. In spite of that positive report, they were not happy with their career because they did not have opportunity to use their potentials and knowledge. This information was an important issue for the planning, provision and nurturing of the gifted/talented. The ONEC responded to the concern by providing fund for research to develop a substantive law regarding gifted education into the Educational Act in 1999. Rights of the gifted were first affixed with children with special needs in Chapter 2, Section 10, “… the education of gifted children shall be provided in appropriate forms in accord with their potential” (The Office of the National Education Commission, Citation1999, p.11).

To implement an appropriate education for the gifted and talented in the educational system has become a responsibility of all schools after the Educational Act was promulgated. Information on school readiness before setting up the educational policy has become of necessity. A survey study was conducted to evaluate the basic conception and school’s readiness of the practitioners before making plans for the special program.

3. Thai concept, value, and beliefs on giftedness

In Anuruthwong’s study “A survey study for developing educational policy in gifted education in Thailand” (Citation2008), the purposes of the study were to: (1) manifest conceptions on gifted education and (2) develop a policy on education for the gifted and talented. The 415 participants of the study were representatives of teachers, administrators from the new 63 schools for the gifted, and representatives of parents of the gifted across the country. They were purposely selected for the study. A set of questionnaires provided to all participants consisted of 30 questions. Only 12 schools were purposely selected for an in-depth interview. Both questionnaire and interview focusing on important processes related to gifted education: policy, definition, identification, programming, and supporting were used as instruments of the study. Information gathered from the questionnaire and interview on their concepts, beliefs, comments, and suggestions were presented in a focus group discussion which consisted of experts in the field of education for the gifted. The conclusion made by the experts during the focus group discussion process. Comments and suggestions were used to develop a policy on gifted education in Thailand. Information from the survey and interview can be found as follows:

In terms of conceptions on definition, there were more than 15 words related to giftedness adopted from the different background of Thai people such as, Me weaw (มีแวว—Person with divine gift, inborn talented, talented performance from natural endowment), and Chalard (ฉลาด—Smart, bright, intellectual person, person with high IQ. They use those words in different situations related to their belief, value, or judgment on the characteristics of a person or impression perceived.

Information from the interview showed that the conception and beliefs impact on program management. Confusion over the criteria and characteristics and phenomena of giftedness were shown during the interview. Incongruity between gifted and talented students with the regular educational system was also discovered. Thus, the word “Kwam Samart Piset” which refers to “giftedness” defined by the ONEC in Citation1999 was recommended to use as a formal definition in the educational system at present.

Other conceptions related to nurturing the gifted/talented indicated that misconceptions toward the education for the gifted reflected the common beliefs found in all countries such as:

| • | Gifted students will make it on their own. | ||||

| • | The gifted will show their potentials without any help or opportunity to discover their potentials. | ||||

| • | The gifted were born to be the gifted, so they will be the gifted without any special program. | ||||

| • | The main role of education is to provide for the majority of students, not constructing a special program for the minority of students. | ||||

| • | Acceleration will lead to failure in the future. | ||||

| • | The term gifted used in most educational contexts refer to their school achievement abilities. | ||||

| • | Gifted students are the ones who perform excellence in all areas. They are perfect. They also have good behavior, social skills, and emotional skills. | ||||

| • | The gifted are the privileged group. It would be favoritism if we treated them with a special program. | ||||

| • | Drill and practice are the most important ways to nurture giftedness. | ||||

Those myths have remained in Thai society for decades which make it more difficult to provide a different method of education. Ignorance on each student’s needs came from the belief in the traditional way of teaching. Those myths also explained roots of mismeasurement and misplacement in our educational system.

From the school management aspect, it was also found that special class is one of the most favorite choices for educating the gifted. However, awareness has been raised on providing the diverse and flexible education to meet both educators and parents’ expectations. This belief has gradually enhanced the development of giftedness indirectly (Anuruthwong, Citation2008). Results of all the information were used as important evidence to develop an appropriate guideline for educational policies. In 2008, the Bureau of Educational Invention Development, the researcher developed an educational policy for the education of the gifted/talented in school settings as follows:

| (1) | Plan for teacher training. | ||||

| (2) | Plan for research and development. | ||||

| (3) | Plan for school management, programming and other services for enhancing the gifted/talented. | ||||

| (4) | Plan for parent education. | ||||

| (5) | Supportive system for the gifted/talented. | ||||

| (6) | Creating networking. | ||||

Descriptions for each topic were provided for all schools.

4. Development of education for the gifted in Thailand

Like most countries, drives in contemporary education for the gifted and talented in Thailand derive from the notion that children with high potentials are likely to make great contributions for the society. In real life, however, most gifted students are bored with schooling and lack motivation in their real life; some are misdiagnosed; some displayed psychosocial issues; others are frustrated because their gifts are not valued. Very few could become the gifted ones (Anuruthwong, Citation2013). These concerns had caught a group of scholars’ and educators’ attention. The Foundation for the Promotion of the Gifted was established in 1980 at Srinakharinwirot University (SWU), Bangkok, to support gifted education in Thailand. The pioneer group’s attempt was to ignite the idea of gifted education into Thailand’s educational system, both in regular schools and special schools. With cooperation of experts in different fields, especially in science and technology, several governmental and non-governmental organizations commenced projects in order to nurture Thai gifted children such as the founding of Development and Promotion of Science and Technology Talent Foundation in 1991, and the establishment of Promotion of Academic Olympiad and Development of Science Education to support the gifted in science and technology in 1998.

Special schools for the gifted and talented were established during the 1990s. The first Science high school for the gifted and talented, Mahidol Wittayanusorn School, was established in 1991. Later, 12 more science schools located in all regions of Thailand were founded. Kamnoetvidya Science Academy is the newest science school founded in 2013. Gifted students in sports are also supported under the Ministry of Tourism and Sports. The first sport school, Suphanburi Sport School, was established in 1993. After that, 13 special schools in sports were founded. Matthayom Sangkeet Wittaya School, which is the only one school in music, was founded in 1993.

There was also a collaboration between parents of the gifted and professionals who work in the field of giftedness. The Parent Club for the Gifted, which was a non-profit organization, was established in 1989 to support parents, educators, and gifted individuals in talent development, conduct research in gifted education and collaborate with other organizations related to the education for the gifted and talented locally and internationally at Srinakharinwirot University. It became the Association for Developing Human Potentials and Giftedness in 2000, located at Thammasat University and a number of participating parents, professionals and educators have accordingly increased (Center for the Center for the Gifted/Talented, Citation2010).

However, transforming from the traditional education that focuses on “the one size fits all concept” to an appropriated learning program to meet the needs of each student is not an easy task, especially with a heterogeneous group like the gifted. Thus, the Ministry of Education set up a committee and appointed working groups in science and arts to work as a coordinate body for schools and experts as well as set out policies to support the gifted.

Attention to and awareness of gifted and talented students in formal education increased among educators after the 7th Asia-Pacific Conference on Giftedness: Igniting Children’s Potential held in Bangkok in 2002. The first Declaration of gifted education was announced. An important massage of the Bangkok Declaration was to provide education for the gifted with morality and fairness. The declaration was agreed by Thailand’s Minister of Education and all national representatives from many countries (see Attachment No. 1).

The conference inspired leaders of the government, educators, and experts in various fields to support the gifted. Education provision for the gifted has increased both in special schools and in regular schools. Most of the famous schools in every province set up special classes or pull-out programs for the gifted and talented in different areas: arts, music, or science. The curriculum and educational management of each organization are differing (Table ).

However, schools that are considered “the advanced schools” have continued to attract a large number of highly outstanding students for decades. Schools generally select students based on their academic achievement. The best students would be first placed in “the King class” and second “the Queen class;” the rest are in regular classrooms. This has led to a phenomenon in which students willingly spend hours in tutoring classes. They drill and practice after school in order to pass the entrance exam and be eligible for high ability classes in famous schools or universities. Activities which may help students discover their interest or develop other essentials such as physical, psycho-emotion, communication skills, or life skills have become their second priority. This has posed one of the major problems in Thai education (The Office of the National Primary Education, Citation2010, Table ).

Table 1. Timeline summary

Table 2. Number of students selected in each subject

4.1. Research for gifted education programming design in schools

The pioneer of the program for the gifted was conducted at Prasanmit Elementary Demonstration School, Srinakharinwirot University in 1980–1981. Teacher nomination, school achievement, IQ test, and student performances were used as main criteria for the identification process. A pull-out, and enrichment program were integrated into five main subjects: mathematics, language, social science, arts, and music. About 40 first grade students were selected to attend the enrichment activities. Results of the program indicated that students receiving the training had impressive changes in a short period of time (three months). Nevertheless, many questions in identifying gifted students and psychological impacts from the program were raised from parents in the school. For example, “My kid is the best. Why was she not selected?”, “What is her IQ score?”, “Is he a genius?”

The project was the first example for school administration and management. The Dean of School of Education encouraged educators to pay more attention to gifted students who also needed special education. She supported many seminars and workshops for staff development on providing gifted education conducted by the School of Education, Srinakharinwirot University after the pilot project had completed. Questions often asked by teachers and administrators during those seminars were:

| • | What are the main purposes of providing education for the gifted? | ||||

| • | Who are the gifted? | ||||

| • | Why should we provide special education for them? | ||||

| • | How many of them are there in our society? | ||||

| • | How do we identify the gifted in each area? | ||||

| • | What should the school management system be in order to provide education for the gifted? | ||||

| • | How much budget have we used for the program? | ||||

| • | How can we change the educational act, or regulation for them? (Center for the Gifted/Talented, Citation1981) | ||||

4.2. Gifted program in special schools

Framework of the model has also been adopted in special schools for the gifted in different areas. However, each school has its exclusive objectives to nurture a particular group of students. The curriculum of special schools consists of two parts: the first part is the national curriculum for all Thai students, and the second part is a special program of each school. All special schools design their own program approved by the Ministry of Education. Enrichment and mentoring, acceleration, and mentoring program have been used in the special schools.

4.3. Research and development model for gifted education in regular schools

In order to promote education for the gifted, those questions mentioned above must be answered. Thus, the Office of the National Education Commission (ONEC) provided fund for research in order to devise a model for curriculum modification and programming for the elementary gifted/talented in regular private schools, Patai Udom Suksa School in 2001. The expectation of the project was to develop an educational model to provide services for the gifted and talented in school system effectively before extending the practice to other schools in the country.

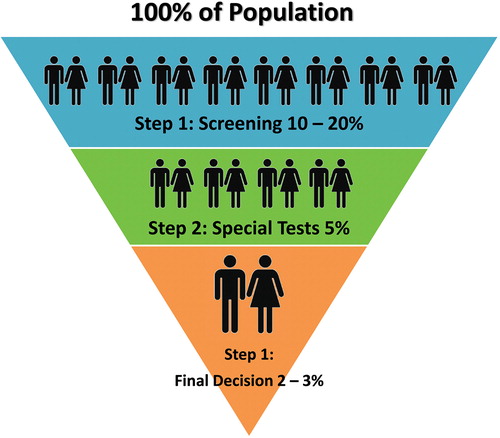

The research team consisted of 34 experts from different universities and school teachers in different areas: mathematics, Thai, English, music, arts, psychology and counseling, research methodology, and educational administrators. Information from reviewing literature was analyzed and synthesized to develop a model structure by the research team. A pilot project was employed with 55 third grade students at Prasanmit Elementary Demonstration School, Srinakharinwirot University. Results of the pilot study were analyzed and improved by the research team before implementing the model at the target school. Participants of the study were 530 third grade students generally of upper- to-middle-class economic status. A three-stage process was used to identify the gifted students in each content area (see Figure ).

4.4. Information gathered in the first stage

| (1) | Observations. Data were collected by the teacher’s observations at the Exploring Center. The Exploring Center is a self-access learning center that integrates and synthesizes knowledge from researches on brain and human learning, learning theory, and the development of thinking skills. It is also the place where children are enriched with academic and social skills. Records of students’ preferences in each subject area and their performance at the center were reported. | ||||

| (2) | Teacher and parent nomination. The checklist on characteristics of the gifted done by parents of the participants and classroom teachers who were familiar with the participants for over one academic year. | ||||

| (3) | Student nomination. Students were told that anyone who wanted to join the classes could do so (self-nomination), or they could nominate their friends into the project. | ||||

| (4) | Students’ performances. Information on performances, awards, or outside classroom activities. | ||||

| (5) | IQ testing. A group intelligence test was administered. | ||||

| (6) | School record. Student achievement in particular subjects was used instead of GPA. | ||||

| (7) | Personality test. House-tree-persons was used to assess students’ personality. | ||||

| (8) | Creative test. Test for Creative Thinking-Drawing Production (TCT-DP) was employed to estimate the participants’ creative thinking. | ||||

4.5. Information gathered in the second stage

All information from the first stage were analyzed by the team of each subject to select students into the second stage. After the first stage, 20% of the students in each area were selected to attend the activities in the second stage. At this stage, students participated in enrichment activities and took special tests designed by experts in each content area. Information from the first and the second was analyzed and used to select students into the third stage of identification process.

4.6. Information gathered in the third stage

In the third stage, multi-disciplinary teams in each subject area reviewed all records and decided which students to be selected into the program. In this stage, the experts from particular field were the most important part of the final decision.

Fifty-nine students or 11.13% from the total of 530 students were identified as the gifted/talented after the third step of identification was completed. Results surprisingly showed that 2–3% of the students in every area were selected as the gifted (see Table ). There are five students who were identified as the gifted in more than two subjects.

A pull-out program was used, along with a variety of program options, including enrichment, acceleration, and extension across subjects. Higher levels of thinking skills and psycho-emotional skills were integrated in all activities. Students in the programs attended two periods of a special class each week for one full academic term (15 weeks).

Multiple procedures, both quantitative and qualitative data: IQ test, creative test, personality test, pre- and post-test, classroom observations, students’ performances, assessment of student attitudes, and achievement tests in each subject, were used as the program evaluation.

All of the information was discussed by the research team. A multi-disciplinary team consisted of experts from each field, classroom teachers, and researchers collected, analyzed and evaluated the data. Reports of the research and handbooks for teachers were published.

The results of the research revealed that:

| (1) | Aptitudes, academic performance and psycho-social skills of the participants improved significantly. | ||||

| (2) | The program was fruitful for the gifted, teachers, and non-gifted students. | ||||

| (3) | The assessment focused on a continuing process more than a result from testing alone. Portfolios and other methods of authentic evaluation were relevantly used as the assessment process used in the regular program. | ||||

In addition, there were important recommendations for the implementation of the model in regular schools as follows:

| (1) | The identification process should evaluate not only the student’s performance or GPA, but psycho-social ability, and thinking skills should also be included in the program. | ||||

| (2) | The pull-out program was appropriate as an initial educational service option. Other types of provisions, such as acceleration and mentoring, should also be introduced and used in the program. | ||||

| (3) | More educational materials and handbooks for teachers and students needed to be developed. | ||||

| (4) | Experts and specialists should be involved in the program for the gifted. | ||||

| (5) | Positive attitudes of administrators and teachers were important to the success of the program. | ||||

| (6) | Parental involvement and support played a vital role in the implementation of the program. Therefore, feedback from parents was necessary for the effectiveness of the program. | ||||

| (7) | Regardless of the types of educational provision, curriculum modification is the utmost requirement for the education for the gifted. It should respond to students’ learning characteristics, needs, abilities, and interests (The Office of the National Education Commission (Citation2002). | ||||

4.7. Project’s implementation to the secondary and high schools

Results of the model implementation in elementary schools were discussed and improved by the focus group before it being expanded to 12 secondary schools in Bangkok and other regions in 2001–2003. Hard copies and electronic copies of full research papers in elementary and secondary levels including handbooks for teachers for the gifted were distributed to all educational sectors in Thailand. The model was used as guideline for special education in regular schools all over Thailand. This research had made good contributions to gifted education in Thailand by creating and making the theories into concrete processes.

4.8. Problems in applying gifted education in regular schools

The fieldwork and survey reports found that there had been problems in applying the program for the gifted/talented to school settings. Obstructing factors contributed to the inefficiency of such a program such as lack of enough skills and knowledge among implementers, and instruments for identification, and clear criteria for program evaluation. Therefore, the National Standard of Education for the Gifted/Talented was designed to help practitioners in administering and managing gifted education programs, especially to be used as a tool for planning, implementing and evaluating the effectiveness of the programs for the gifted. It also provides teachers and stakeholders with guidelines and benchmarks for developing and evaluating educational programs designed for gifted and talented students (The Office of National Council, Citation2009).

4.9. Research on developing the National Standard of Education for the Gifted/Talented

The National Standard of Education for the Gifted/Talented comprises four major categories.

| (1) | Policy and management. The agency must establish articulated written policies, appropriate administration and management, competent personnel and effective scheme evaluation. | ||||

| (2) | Identification processes. The agency must have a process of seeking and identifying gifted students using a variety of quality identification instruments based on individual differences, specific needs or the socio-cultural base of the students. | ||||

| (3) | Educating and programming. The agency must have a quality instructional management plan, a curriculum, education models, educational media that support the unique characteristics of gifted students and verifiable student performance evaluation. | ||||

| (4) | Services related to enhancing socio-emotional abilities. The agency must have a system to select or identify gifted students displaying socio-emotional difficulties to benefit from the socio-emotional development. | ||||

All of the standard categories consist of indicators which provide guidelines for educators and practitioners for the administration of the education for gifted and talented students (full details of the National Standard of Education for the Gifted/Talented are available on the Office of Educational Council website in Thai). (See the example on attached paper No. 2 in Appendix 1).

4.10. Issues that need to be addressed in order to provide appropriate programs and services for gifted learners

The National Standard was used to evaluate the program for the gifted across the country by the research team of the Center for the Gifted and Talented, Srinakharinwirot University. The research was conducted at the 40 gifted centers in schools located in all regions of Thailand funded by the Office of the Prime Minister in 2011. The objectives of the study were:

| (1) | to evaluate the gifted centers with regard to the physical and dynamic part, and | ||||

| (2) | to provide guidelines for improvement and suggestions for an expansion of the centers to other regions. | ||||

The research consisted of two phases:

| (1) | The first phase was to collect quantitative data from 40 centers. The sample size for this phase was 1,102 subjects comprising head of the center, teachers of the center, administrators of the school; students participating at the center, teachers, parents, and students from network schools. Observation, interview, documentation related to the program, and questionnaires were used as the data collection of the context, input, process, output, and outcome of the center using observation, interview, and questionnaires. | ||||

| (2) | The second phase was a collection of qualitative data from nine centers selected from the best practices representing each school type. The sample comprised head of the center, teacher of the center, administrators of the school; students participating at the center, and teachers. The semi-structured interview and observation were used as data collection on the school policy on gifted education, principles and objectives of the project, school management, identification process, programming, and program evaluation as well as the school policy and administration. The CIPP Model was deployed as research methodology to evaluate and analyze the data (the CIPP Model is an evaluation model that requires the appraisement of context, input, process and product of the program for program evaluation). Results revealed that all centers must be improved to meet the minimum standard level especially the methods and instruments used in the identification process. Psycho-social aspect and cultural differences should be included in the services. In addition, the program evaluations of all centers were under the standard level and must be improved to meet the objectives of the program evaluation and the evaluation design. In contrast, the output of centers as perceived by a number of school networks were at high level. | ||||

4.11. Problems found in schools setting, and suggestions done by the research team for improvement were

4.11.1. Problems on programming

| (1) | Administrators need a clear policy and continuing support from the Ministry of Education. | ||||

| (2) | Teachers need more training on how to develop a curriculum, teaching strategies, and options for conducting the program. | ||||

| (3) | There is a lack of clear guideline on how to evaluate such program as administrators and teachers. | ||||

| (4) | There is a lack of appropriate facilities, budgeting, and teaching materials and handbooks. | ||||

| (5) | Experts are needed for program activities and program evaluation. | ||||

4.11.2. Suggestions

| (6) | The Ministry of Education should provide a standard of practices or a guideline for educational activities for gifted children, and an evaluation manual for program evaluation, and training for all staff. | ||||

| (7) | Schools should establish collaborative network with local universities. | ||||

| (8) | The Ministry of Education should provide a standard of practices and indicators for center management. | ||||

| (9) | Schools should plan for an evaluation of activities of the program and regularly report the result to all parties. | ||||

4.11.3. Problems on the identification process

| (10) | Teachers need more training on characteristics and factors contributing to the phenomenon of giftedness. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (11) | There is a lack of understanding among teachers and parents on definitions of the gifted. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (12) | Teachers need more clear criteria on the identification process. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (13) | There is a lack of appropriate instruments used in the program. Problems in using instruments are:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

4.11.4. Suggestions

| (14) | There should be a core unit to provide standards of identification processes, training for teachers and staff on characteristics of gifted children, process of identification, and use of appropriate instruments. | ||||

| (15) | The Ministry of Education should provide new instruments for regular Thai students, disadvantaged students, students with special needs, and provide a systematic collection of instruments used in identification, and research based knowledge from expert practices. | ||||

| (16) | The Ministry of Education should provide standards for practices in all steps including student pools, use of instruments, parental informed consent, and, evaluation result information. | ||||

| (17) | The Ministry of Education should provide training for instrument used for disadvantaged or differently cultural students and should carry on a need assessment on this issue. | ||||

In addition, there were suggestions for training on programming and curriculum design within school settings, and how to select schools to implement the project. Another important issue was how to use education of the gifted to raise quality for every school (Yolao, Kaseamnet, Harnkajornsuk, & Sakveerakul, Citation2012).

Another research project that aimed at evaluating the efficiency program for the gifted with various types of schools located across the country was also done by the research team at Center for the Gifted, SWU in 2012. Results of the study revealed that there had been more efforts and supports from different organizations to promote gifted education compared to the prior project. However, difficulty in conducting the program for the gifted stills remained. There were problems needed to be unlocked in educational system: improve the national policy and law for gifted education (Panyamaethekul, Piboonchol, & Wiriyachitra, Citation2012).

In order to assist the identification process in the schools, the Office of the National Primary Education (ONPE) provided research fund to the Association for developing Human Potentials and giftedness to develop a screening instrument for school teachers. This instrument has been used for teacher training after the project was completed (The Office of the National Primary Education, Citation2013).

4.12. The future directions for research and program development

Although education for the gifted has been adopted into educational system since 2000, improvements in all aspects must still be improved or developed. There are needs for future research in many aspects:

| (1) | Policy-making. | ||||

| (2) | Supportive system. | ||||

| (3) | Accreditation system. | ||||

| (4) | Teaching strategies for the gifted. | ||||

| (5) | Developing instruments for the identification of giftedness. | ||||

| (6) | The effectiveness of programming. | ||||

| (7) | Integrating the psycho-emotion and moral education into gifted programming. | ||||

| (8) | Cross-cultural research. | ||||

Expansion of the program for the gifted would be based on those aforementioned areas for the future development. In addition, integration of local wisdom and cooperation among international partners are also important for the future plan.

5. Conclusion

Gifted education in Thailand today is totally different from what was previously done. Although the educational system was replaced by the western system, some local wisdom has still been supported by local or other government sectors rather than education. Some Thai wisdom still continues and is passed down from generation to generation. A dual system in nurturing giftedness is going on in the country. One is offered by the local Thai wisdom as “informal education” and the other one by the educational system as “formal education”. Thus, gifted education always faces a number of challenges: conception of people toward the gifted, supportive system, educational system and such.

In addition, results from the research and fieldwork reports presented in this paper illuminate many factors contributing to the limitations of program development in all steps of the formal education. The identification process is the first step and it is the most difficult step to understand and implement. Lack of resources, both materials and human, have a great impact on identifying giftedness and programming. Although education for the gifted/talented in Thailand is not new, it still needs a lot of improvement. It is a still big challenge for educators to find a way to provide appropriate opportunities for them. Integrating the Thai traditional process into that of the formal education might be one of the challenges in the future research. All areas of research and development in identification, programming, and program evaluation are needed for further implementations.

Dedication

May the author humbly dedicate this article to H. M. King Bhumibol the Great (5 December 1927–13 October 2016), who was a true all-round genius as witnessed and recognized throughout the world. His creative achievements in art, music, science, literature, agriculture, irrigation, religion, education, and government stand as monuments of his deeds throughout 70 years of his reign. Loved by his people for his dedication to his duties as their King, his perseverance and insights into how to turn problems into assets and opportunities and alleviate their suffering. Thus, he became and shall remain a mentor and an everlasting light to our nation.

Acknowledgment

The work of this book represents development of education for the gifted in Thailand from the past to present. Information presented in this article was collected from important pieces of research which had made impacts to gifted education society in Thailand. Special thanks go to many researchers who have spent time and effort conducting studies presented in this article. The author would like to give my gratefulness to Prof. Dr. Aree Sanhachawee, the former Dean of Education who was the pioneer of gifted education in Thailand. I also would like to express my appreciation to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Arunee Wiriyachitra, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sumarng Hiranburana, Assoc. Prof. Sonthida Keyuravong, and Mrs. Praoranuj Chantrasomboon for helping me to shape my thoughts and editing the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Usanee Anuruthwong

The author has worked in the field of gifted education in Thailand with various groups of researchers from different fields since the beginning of the first research project of the country in 1980 until today. The main supporting research involved is: The Development of Model on Gifted Education, creating the Exploring center, research for identification instruments and process in identification, the National Standard for Education for the Gifted/Talented, research for the national plan for nation policy and national law. Additional main work related to promoting the gifted includes: writing 15 books for parents and teachers of the gifted/talented and numbers of articles, including promoting knowledge about nurturing giftedness using mass media.

References

- Anuruthwong, U. (2007). Thai conceptions of giftedness. In S. N. Phillipson & M. McCann (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness: Sociocultural perspectives (pp. 99–126). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Anuruthwong, U. (2008, July). A survey study for developing educational policy in gifted education in Thailand . Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Federation of the World Council for Gifted and Talented Children. Seoul, Korea.

- Anuruthwong, U. (2011). Education for the gifted/talented . Bangkok: Association for Developing Human Potentials and Giftedness.

- Anuruthwong, U. (2013). Identification for the gifted/talented . Bangkok: Inthanon Publishing Limited.

- Association of South East Asian Nations . (2000). South East Asia a passage through time . Hong Kong: Ringier Contract Publishing Ltd.

- Center for the Gifted/Talented . (1981). Study on programming for gifted education in primary school . Bangkok: Srinakharinwirot University.

- Center for the Gifted/Talented . (2000). Annual report on identification and programming for the gifted/talented . Bangkok: Srinakharinwirot University.

- Center for the Gifted/Talented . (2010). Report on Thai gifted education . Bangkok: Srinakharinwirot University.

- Panyamaethekul, S. , Piboonchol, C. , & Wiriyachitra, A. (2012). A study on program follow up and program evaluation on gifted Education . Bangkok: The Office of National Council (ONC), Ministry of Education.

- Renzulli, J. (2003). Giftedness and social capital. In N. Colangelo & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (p. 77). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- The Office of the National Education Commission . (1998). Education in Thailand: Education reform . Bangkok: Author.

- The Office of the National Education Commission . (1999). The national act of education . Bangkok: Author.

- The Office of the National Education Commission . (2002). The development of model for gifted education . Bangkok: Author.

- The Office of National Council . (2009). The national standard of education for the gifted/talented . Bangkok: Ministry of Education.

- The Office of the National Primary Education . (2000). Education reform . Bangkok: Ministry of Education.

- The Office of the National Primary Education . (2010). Report on educational reform . Bangkok: Ministry of Education.

- The Office of the National Primary Education . (2013). The development of screening instrument for the gifted/talented . Bangkok: Ministry of Education.

- Yolao, D. , Kaseamnet, L. , Harnkajornsuk, S. , & Sakveerakul, T. (2012). An evaluation of gifted programming . Bangkok: Office of the Prime Minister.

Appendix 1

Attachment paper No. 1

Bangkok Declaration on the Gifted and Talented

Bangkok Declaration on the Gifted and Talented

We, the Participants of the 7th Asia-Pacific Conference on Giftedness, meeting in Bangkok, August, 2002 and representing 20 countries, intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations, private sectors and members of civil partnerships worldwide, hereby commit ourselves to a global partnership to protect and promote the gifted and talented.

The Challenges

| (1) | Many individuals and groups at all levels of society have roles to play in the full and harmonious development of the gifted and talented. We take into account the importance of the traditions and cultural values of each person for the protection and development of the individual. The gifted and talented need to develop their potentials in an atmosphere of happiness and understanding and to live in and shape the society in a spirit of peace, dignity, responsibility, tolerance, freedom, equality, and solidarity. | ||||

| (2) | Every child is entitled to the right of a free and appropriate education. This is reaffirmed by the Convention of the Rights of the Child, an international legal instrument of universal significance. State are required to recognize the rights of the child to an education on the basis of equal opportunity and agree that the education of the child shall be directed to the development of the child’s morality, personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential for the benefit of humankind and themselves. The principle of the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration in all actions concerning children, and their rights are to enjoyed without discrimination of any kind. | ||||

| (3) | Individuals can be gifted ad talented in many different ways. Professional teams can identify their potentials and abilities using multiple and various types of assessment, dynamic assessment, performances, and portfolios. | ||||

| (4) | The identification of gifted and talented with learning difficulties and/or disabilities is important. Their needs require appropriate provisions. | ||||

The Commitments

For the benefit of humankind and the gifted and talented, the Participants of the 7th Asia-Pacific Conference on Giftedness have come together to:

| (1) | Provide opportunities and supportive systems for the gifted and talented (who are individuals with high abilities and talents.) | ||||

| (2) | Give priority to action for the full and harmonious development of the gifted and talented. | ||||

| (3) | Create differentiate educational programs in order to fully develop their potential. | ||||

| (4) | Advocate and mobilize educational support specifically for the teacher education and to ensure that adequate financial and non-financial resources are available to promote appropriate education for the gifted and talented. | ||||

| (5) | Increase knowledge and improve practices for the gifted and talented through encouraging and supporting the establishment of research and resource centers. | ||||

| (6) | Encourage and support centers, institutions, and associations for the gifted and talented. | ||||

| (7) | Enhance the role of the family, including that of the child, especially in the social, emotional, and moral development of the gifted and talented. | ||||

| (8) | Adapt or modify procedures for identification, teaching methods, and programs for special populations of gifted and talented, such as those in isolated and/or rural areas. | ||||

| (9) | Review and revise, where appropriate, laws, regulations, policies, programs, and practice necessary to meet the needs of the gifted and talented. | ||||

| (10) | Mobilize political and other partners, national and international communities, including intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organization and private sectors, to assist countries by by means of cooperation, networking and exchange of knowledge and information, to develop and to implement plans and programs for the gifted and talented. | ||||

Attached Paper # 2

Example of one Standard taken from the Category 2 of the National Standard: Identification Process.

Standard 2: The agency has a comprehensive, appropriate, and varied process for student referral and assessment.

| 2.1 | The procedures are in place for student referral and assessment. | ||||

| 2.2 | The criteria are in place for soliciting referrals and assessment. | ||||

| 2.3 | The personnel responsible for soliciting referrals and assessing potentially gifted students exist. | ||||

| 2.4 | Handbooks of student identification are distributed to the assessment personnel and all staff concerned. | ||||

| 2.5 | The procedures are in place for soliciting referrals from all levels. | ||||

| 2.6 | The procedures are in place for soliciting referrals from underachieving students, and/or students with special needs, and/or lower socio-economic students. | ||||

| 2.7 | The procedures for student referral and assessment are comprehensive, appropriate, and varied. | ||||

| 2.7.1 | The assessment personnel attend the informational meetings on a basis of each referral procedure. | ||||

| 2.7.2 | Parents are provided information regarding the procedures of student referral and assessment. | ||||

| 2.7.3 | The written procedures for student referral and assessment exist for parent appeals. | ||||

| 2.7.4 | Various and continual information is used to identify gifted students for entering the program. | ||||

| 2.7.5 | Existing the notification of results showing that the identified gifted students are classified in the area of giftedness consistent with their abilities, loves, interests, and aptitudes. | ||||

| 2.7.6 | Parents are provided information regarding the process for the requirement of refusing or reviewing the assessment team report. | ||||

| 2.7.7 | Written assessment team reports exist. | ||||

| 2.7.8 | Recommendations for gifted instructional management plan are provided to parents and others concerned. | ||||

| 2.7.9 | Parents are provided informed consent regarding the student reassessment and exiting the program. | ||||