Abstract

In 2016, Dr. Martin Reinhardt and Dr. Jioanna Carjuzaa produced a series of three webinars concerning Indigenous language immersion programs. The first webinar focused on broad curriculum development ideas including core relationships, guidelines and principles for effective pedagogy, and models. The second webinar focused on the elements of lesson planning. The third and last webinar focused on assessments and the use of rubrics aligned with Indigenous language standards. The content of the webinars has been transposed into the following chapter with certain modifications.

Keywords:

Public Interest Statement

The ideas presented here are intended to assist Indigenous language immersion educators as they engage in curriculum development and assessment. The broad concepts and examples provided will help situate Indigenous language immersion programs in relation to general education concerns. The references included represent current and ongoing discussion and research in this area.

1. Introduction

In her report Native American Language Immersion: Innovative Native Education for Children & Families, Janine Pease-Pretty On Top (Citationn.d.) provided an overview of the history and status of Native American language immersion schools and projects. She also included a broad and inclusive discussion of the principles and benefits of such programs. Richard Littlebear states in the introduction, that “this report will be of tremendous value to those people who teach, strive to speak, or otherwise seek to acquire their Native languages, mostly as a ‘second language’ now, coming behind their years of learning English” (p. 5). Littlebear goes on to explain that “this study provides … a wealth of research on Native American language immersion programs and the remarkable benefits that derive from them” (p. 5). Given the incredible amount of background knowledge that has been amassed by Pease-Pretty On Top and others surrounding Indigenous language immersion programs in general, rather than duplicate their efforts, this chapter focuses on a few key areas in the relationship between Indigenous language immersion programs and the general education curriculum.

2. Curriculum development

In 2012, the Windwalker Corporation and the Center for Applied Linguistics conducted a literature review regarding Indigenous language immersion programs (Fredericks, Citation2013). They were examining “how to introduce or maintain the heritage language of [Indigenous] students in an educational setting while ensuring a meaningful and useful education with improved educational outcomes” (Fredericks, Citation2013, p. 11). In order to begin to answer this question, we first need to understand the core relationships of Indigenous Language immersion programs.

The special knowledge that is at the very core of these programs is the Indigenous languages themselves. The broad goal of Indigenous language programs is to impart this knowledge to the language learners.

Indigenous language teachers are the carriers of Indigenous languages. Some of these teachers are first speakers (individuals who speak their Native language as their primary or first language), and some are advanced Indigenous language learners. Although it is possible, it is rare to find that first speakers or advanced learners are also certified general education teachers.

While uncommon, it is very beneficial when general education teachers take part in Indigenous language immersion programs. The combination of their general education knowledge and Indigenous language knowledge can help these teachers fill the role of linguistic and cultural border crosser (Aikenhead, Citation1996). The conceptual gap between linguistic and cultural communities can act as a major barrier to student learning if they are unable to navigate their way through the complex maze of differences, or even if it feels too difficult to begin, continue, or complete the journey (Table ).

Table 1. The core relationships of Indigenous language immersion programs

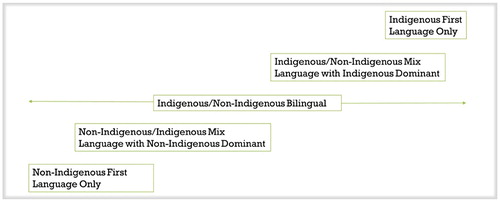

It is important to know where Indigenous language learners fall on a continuum, whether they are non-Indigenous first language only at one end, or Indigenous first language only at the other. This model assumes that either type of learner can attain bilingual status in the middle. Unfortunately, most learners will fall closer to the non-Indigenous first language only end of the continuum. Very few younger people are what would be considered First Speakers today. Obviously, we will need to develop a curriculum that is responsive to the needs of students wherever they fall on the continuum (Figure ).

Besides their ability to speak Indigenous languages, educators must also consider other aspects of their students. Age, grade level, ability, cultural background, availability of educational resources, time in class, and additional exposure to the language all play a role in fostering language learning success. Students in Kindergarten, at 5–6 years old, cannot be expected to perform at the same level as middle school students or high school students. Students also come to our classrooms with varying abilities for speech in general, or for physical activity, we must consider how we are going to provide all of our learners with an Indigenous language curriculum that is responsive to their needs which may be different based on their cultural background and other aspects of student diversity. All of this must also be weighed against the amount and type of resources educators have to work with, and the time they get to spend with them in their Indigenous language classrooms.

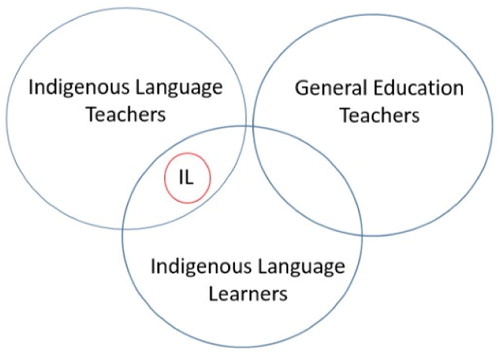

Scenario A presents a situation where Indigenous language teachers and general education teachers both have important jobs of imparting knowledge to our children, but only the Indigenous language teachers provide exposure to Indigenous languages. This is often the most common scenario we see in our schools today (Figure ).

Although it is great to have Indigenous language teachers in our schools, this scenario has the potential to create a rift between equally important areas of knowledge. Students may start to see one as area as being more important than the other, especially if they don’t see their teachers working together.

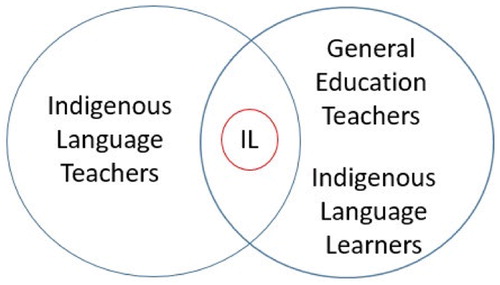

Scenario B presents a somewhat different situation, in this case, the general education teachers are also language learners. Although it is less common than scenario A, it is something that we are seeing more and more in our schools. The encouragement from school leadership for general education teachers to participate in Indigenous language learning is important to foster this type of interaction, and it is something that should be explored as part of general education teacher’s ongoing pre-service and in-service professional development requirements (Figure ).

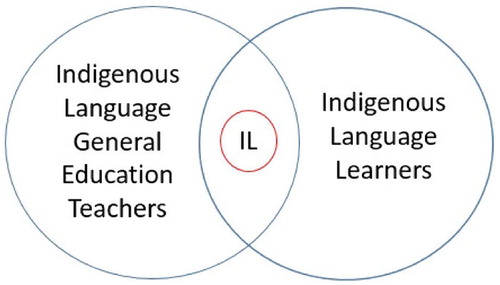

Scenario C presents the least common but most beneficial situation for Indigenous language immersion. In this case, the Indigenous language teachers are also general education teachers, so the students receive instruction in core subjects in the Indigenous languages. Encouraging Indigenous language teachers to pursue teaching degrees in general education is one method that has worked to the advantage of some schools as they move forward toward their immersion goals (Figure ).

In addition to the great amount of diversity among our language learners and teachers, we also know that there is a vast array of approaches to the idea of Indigenous language immersion itself. Approaches range from total onsite immersion multi-year programs to online immersion one-hour sessions. While each of these approaches have their unique value, the approach does impact the outcomes. We simply cannot expect to have the same outcomes from an online immersion session that we would from an onsite multi-year experience.

It is also worth noting that different tribes may approach Indigenous language immersion differently based on local cultural and linguistic traditions. There are almost 300 Indigenous languages still spoken in North America (Moseley, Citation2010), and there are currently 567 federally recognized tribes in the United States (United States, Federal Register, Citation2016). Given the great amount of diversity in tribes and tribal languages, we should expect to see nuances between these programs. Even within tribal groups, we see differences in dialect and local preferences for some terms or expressions over others.

In 2003, the late William Demmert & John Towner provided us with A Review of the Research Literature on the Influences of Culturally Based Education on the Academic Performance of Native American Students. Based on their analysis, they concluded that there are six critical elements of Culturally Based Education (CBE) for successful Indian education programs (pp. 9–10) (Table ).

Table 2. Demmert & Towner’s six critical elements of culturally based education

Recognition and use of Indigenous languages are included as a critical element, although it does allow for multiple approaches as to how that is accomplished. It is not enough to just include Indigenous languages in the curriculum, however, they concluded that we must also consider traditional cultural characteristics and adult–child interactions, teaching strategies are congruent with the traditional culture, recognition of the importance of Native spirituality, strong Native community participation, and knowledge and use of the social and political mores (customs, values, and traditions) of the community.

McCarty (Citation2014) suggests that Indigenous language programs should not be forced, should encourage parent and family participation, should draw on the students use of whatever their first language is as a strength. They should be full-day, or most of the day and that there should be continuity between the school year and summer activities. Similar to Demmert and Towner (Citation2003), McCarty (Citation2014) emphasizes that teachers should be engaging students in culturally appropriate education across the curriculum.

McCarty (Citation2014) goes on to explain that a government commission in New Zealand found that the stronger a child becomes in their Indigenous language the more likely they are to be successful in English. This is known as the “Language Interdependence Principle” (McCarty, Citation2014, p. 2). Thus, the learning of Indigenous languages can strengthen a student’s ability for other academics. The commission also found that immersion requires several years to demonstrate optimal results. We should not expect to go from zero Indigenous language to fluent speaker overnight.

The Center for Research on Education, Diversity & Excellence (Citation2011) Standards for Effective Pedagogy are also supportive of the idea of incorporating Indigenous language across the curriculum. Their standards reinforce scenarios B and C from earlier in that they would have teachers and students producing something together in an Indigenous language learning context. This is called a Joint Productive Activity. These standards are also conducive to the idea of conversational immersion in that they encourage an instructional conversation (Table ).

Table 3. CREDE standards for effective pedagogy

James Bank’s Stages of Multicultural Curriculum Transformation (Gorski, Citation2012) are also helpful to us as we develop curriculum in that they remind us about what the ultimate goal is, not simply to focus on discrete cultural elements like heroes and holidays, but to transform the curriculum and get our students to a point where they are able to make decisions on important Indigenous social issues like Indigenous language learning and take actions to help solve them. The students are not just recipients of education, but are empowered by it to make changes.

When we focus on the needs of our students, and we are responsive to those needs, it can be said that we are using a student-centered teaching and learning approach. In this approach, we want our students to be actively involved in their learning. They solve problems, ask and answer questions, and engage in lively discussions and debates. They also engage in cooperative learning activities where they work on group projects, but are also accountable for their individual contributions. Lastly, this approach is inductive. It presents the students with a challenge, and they learn as they attempt to solve the problem (Carjuzaa & Kellough, Citation2016; Felder, Citationn.d.).

It is important that we produce and/or deliver Indigenous language curriculum that is free from bias. Slapin and Seale’s (Citation2006) “How to Tell the Difference” in the book Through Indian Eyes: The Native Experience in Books for Children, and McClusky and Ferguson’s (Citation2015) Guide for Evaluating American Indian Materials and Resources for the Classroom and a host of others (Cubins, Citation2000; Lindala, Citation2013) provide us with good examples of good Indian education materials, as well as good examples of bad Indian education resources.

Issues of identity permeate American Indian education. It is vital that we pay attention to how labels come through in our work. Consider how different Indian is as compared to Anishinaabe. There may be times when it is appropriate to use one vs. the other, but many people haven’t been taught about these things. Since one is a pan-ethnic term, and one is a cultural-specific term, we need to explain to our students and others why we use them as we do.

Cultural and linguistic accuracy are extremely important to Indigenous language immersion programs, but can also present great complications. For instance, the preferences of one community of Anishinaabemowin speakers vs. another. One community may prefer the post-contact mixed Anishinaabemowin-English terms for mother and father, ni-mama and ni-papa, where another may prefer the pre-colonial terms, ngashe and Nos. We must be accurate and flexible at the same time if we are to respect the preferences of our language speaking and learning communities.

Historical accuracy is similar to cultural and linguistic accuracy in that it is tied to specific areas and cultural interactions. An example might be the absence of tomatoes in the Great Lakes Region prior to 1,600. Thus, if we see artistic renditions of pre-colonial harvest feasts that include tomatoes, we know that the artist didn’t do their homework.

Legality and authority concerns may stem from the identity of an artist or teacher. Is this teacher recognized by their tribe to teach this language, or does the artist qualify as an Indian under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act?

It is important for educators to draw on credible sources of information and to reference them as appropriate. Realizing that there are certain cultural protocols that must be respected and followed regarding oral historical data, it is still important that we have a mechanism to vet the information so we know it is coming from a source that is recognized as legitimate within the tribal community it is coming from.

Educators should be careful not to generalize things as being applicable to all Indian tribes or people. They should strive to be as specific as possible based on the content of their instruction. For instance, it would be inaccurate to say that Indian people in general have access to Indian Health Services facilities. In reality only those Indian people who are citizens of federally recognized tribes have this privilege.

Invisibility, tokenization, fragmentation, and isolation are all similar terms, but mean different things. According to Sadker (Citationn.d.), invisibility refers to “the complete or relative exclusion of a group.” Tokenization refers to the type of inclusion shown in the example on the slide, the inclusion of Indian references in a small and unimportant way so they can say that they had Indians in the curriculum. Sadker (Citationn.d.) also explain that fragmentation “emerges when a group is physically or visually isolated” in the curriculum. For instance, Indian stuff is always isolated to Indian units around Thanksgiving.

Indian stereotypes can be both positive and negative. Both can have negative impacts on our students and their educational experience. The example provided focuses on two stereotypes, the crying Indian, which is generally thought of as a positive stereotype based on the idea that Indian people are environmentally conscious, and the casino Indian, which is often portrayed as negative making Indians look like all we care about is money. It is easy to see how these two polemic stereotypes can cause harm to children who are trying to figure out their identity. We need to deliberately deconstruct these stereotypes so the students can see how they come to exist in the first place and help them see the positive and negative effects if any.

It is also important that we include Indian perspectives on things that are common to the general curriculum. For example, US independence from Great Britain may mean something quite different to Indian people than it does to non-Indian people. The ability of our Indian leaders to succeed in war or diplomacy against the US may also be seen as negative by non-Indian people.

Sadker (Citationn.d.) note that unreality is “the tendency of instructional materials to gloss over unpleasant facts and events in our history.” The example provided is Thanksgiving Day stories. These stories are more myth than reality. They are made to make us feel good about the colonization of Indigenous lands by non-Indian people. Not only are they historically inaccurate, but they try to sell us on a reality that empowers one group over another as a good thing.

The last component in the evaluation section focuses on using Indian friendly wording in our curriculum. Anti-Indian biased/loaded words appear often in mainstream curriculum materials. We need to filter these out and replace them with better choices (Table ).

Table 4. Indigenous curriculum materials checklist

The use of Indigenous Interdisciplinary Thematic Units (IITU) (when keeping to the above guidelines) can provide students with an enriched educational experience that cuts across academic disciplines, while making connections between the classroom and other classrooms, different grade levels, the school itself, and with tribal communities and families (Carjuzaa & Kellough, Citation2016; Roberts & Kellough, Citation2008). Finding the Indigenous in the curriculum, or alternately finding the curriculum rooted in the Indigenous are two paths that educators follow when developing these units. Finding the Indigenous in the curriculum is the preferred approach, but it is not always the easiest (Reinhardt & Maday, Citation2005).

The depth and breadth of the IITU can be thought of in terms of vertical and horizontal alignment (also referred to as scope and sequence (Carjuzaa & Kellough, Citation2016). The relationship between different subjects or classrooms at the same grade level would be examples of horizontal alignment, whereas the relationship between multiple grade levels would be an example of vertical alignment. Both types of alignment are important for creating a more holistic, interrelated IITU.

The thematic unit approach begins with a focus on standards alignment, which includes tribal standards (Carjuzaa & Kellough, Citation2016). All tribes have the sovereign authority to create and implement their own standards, although many have not yet done so. In this situation, it may be that there are standards that exist with an oral tradition. Educators are much more familiar with state, Common Core, and national standards. The standards alignment process is something that most teacher education programs incorporate into pre-service education, and most veteran teachers have been exposed to these processes on multiple occasions. While this can be extremely tedious and time-consuming task, it should not be surprising to encounter resistance when trying to introduce new methods and materials into schools and classrooms like tribal standards (Table ).

Table 5. Seven essential steps for developing an Indigenous interdisciplinary thematic unit (As adapted from Roberts & Kellough, Citation2008)

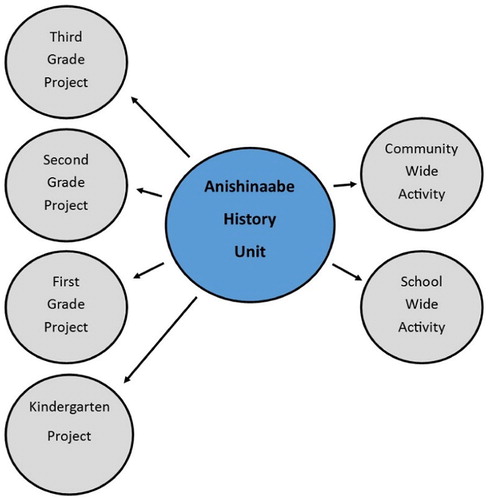

Another useful tool for helping students connect multiple big ideas in an IITU is the use of mind mapping. Some students enjoy drawing mind maps, but there are also several programs that can be used to do this. Having students create their own mind maps helps them visualize the relationship between different parts of the curriculum. The example in the illustration to the left is based on an Anishinaabe History Unit IITU that vertically aligns Kindergarten – Third Grades, and incorporates school wide and community components (Figure ).

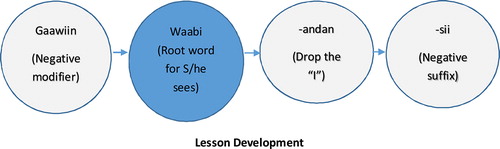

Using a mind map to map out linguistic relationships is another approach that has been helpful for teaching Indigenous languages. When combined with use of color coding, it can help students associate linguistic relationships with certain colors. In classrooms that do not incorporate a written tradition, the use of visual aids as reminders of sounds can still offer a tremendous advantage as students struggle with complex relationships between parts of speech like prefixes, suffixes, gender terms, and animacy. In the following example, a root word in Anishinaabemowin (the Native language of the Anishinaabe) is surrounded by additional parts of speech that modify the original word (Figure ).

3. Lesson development

IITUs must be operationalized through the development of lesson plans related to the theme. In the example unit above, it contains vertical grade level project components. The lesson plan example in this section is based on the third grade component and a hypothetical classroom in Gwinn, Michigan (Table ).

Table 6. Anishinaabe medicine wheel history and geography lesson plan

Bilash (Citation2009) suggests that when “planning speaking activities, teachers need to decide whether students need high structure (for example drills and controlled practice) [or] low structure (for example role plays, simulations)”. She also suggests that teachers ask themselves the following questions:

| • | Is it necessary to review the language to be used in a task? | ||||

| • | Will the learners work in pairs or small groups? | ||||

| • | How will learners be monitored as they complete task? | ||||

| • | How will teachers provide feedback to students? | ||||

4. Indigenous language immersion assessment

It is beneficial for Indigenous language immersion teachers to use a variety of assessment strategies in their classrooms as they attempt to meet their intended outcomes. Some strategies may incorporate highly structured activities, and some may incorporate less structured activities, or a combination of both.

As Indigenous language teachers are developing, or redeveloping, their assessment strategies, it is important to consider how the strategies align with the language of instruction. If students are at a point in their Indigenous language learning that they are receiving instruction in Indigenous language, then it is wise to assess them in that language if they are also able to comprehend the questions being asked. It is also important for teachers to consider how the assessment aligns with the student’s reality. If the questions are reflective of their daily lives, they will be much more likely to answer the questions in a meaningful way.

The Center for Applied Linguistics provides examples of rubrics that can be used for assessing oral and written language skills development (Arlington County, Citation1997). Depending on how educators are approaching their instruction, these rubrics can provide a starting point for them to develop their own rubrics. These rubrics focus on comprehension, fluency, vocabulary, and grammar when assessing oral skills, and focus on composing, style, sentence formation, usage, and mechanics when assessing written skills. Educators will want to adapt these rubrics to better fit what they are doing in their classrooms.

Table shows an example of an Oral Language Immersion Assessment Rubric for Grade 1 (Arlington County, Citation1997). All components of the rubric incorporate a scale from 1 to 5 to provide an overall numerical value for where a student is at, based on grade level intended outcomes.

Table 7. Oral language immersion assessment rubric

Under Comprehension, the rubric is concerned with how often the student comprehends speech at a normal rate of speed, and if they do so with or without non-verbal cues. Under Fluency, they are concerned with how well a student is speaking in the language. It is based on a continuum from using Native-like flow of speech at the high end, and using one-word/two-word utterances or silence at the other end. In order to use such a continuum for assessment, the students should have had an opportunity to learn how to use Native-like flow of speech on several occasions. There may also be reasons that a student would be silent other than not knowing how to speak. This should be considered when using such a continuum.

Under Vocabulary, the rubric is concerned with how a student incorporates different terms into their language use. At the top end they would expect a student to use varied and descriptive language, possibly including Native-like phrasing and/or idiomatic expressions, whereas at the bottom end, they would expect that a student would use only the language that they already know vs. the language they are trying to learn. Ironically, they refer to the student’s first language as their Native language. Obviously this does not refer to what we would call Indigenous languages.

Under Grammar, this rubric would score a student higher if they make less mistakes using basic grammar. They provide a checklist of possible areas that students may make mistakes in. Included are oral production (meaning a student knows how to both speak and understand what is being spoken), tenses (past, present, and future), complex verbal structures (substituting one way of saying something for another, for instance, “the girl ran to the lake” vs. “the lake was where the girl ran to”), gender agreement (which may be quite different in certain languages than it is in English), singular/plural, subject-verb agreement, negations, adjective placement, direct object pronouns, prepositions, and articles. Again, it is important for Indigenous language instructors to be familiar with the grammar rules of the language they are teaching and to apply the rules at an appropriate age level similar to what is presented here.

Due to the great diversity between Indigenous language immersion programs, there are some that focus on oral language skills, whereas others incorporate both oral and written. Table is another example of a table from the Center for Applied Linguistics that is focused on Written Language Immersion Assessment for Grade 1.

Table 8. Written language immersion assessment rubric

Under Composing, the rubric is concerned with a range of composition skills ranging from the top end where a student is able to develop a story or topic with supporting details, whereas at the bottom end, the student may only be able to draw something related to the topic. Notice that in this rubric they do not include assessment strategies for style at this grade level.

Under Sentence Formation, the rubric is concerned with students being able to use all types of sentences effectively. Thus, it requires that the instructors and students be familiar with the different types of sentences. For instance, in English there are declarative, imperative, interrogative, and exclamatory sentences, but there are also simple, compound, complex, and complex-compound sentence types (the type is based on the presence of independent and dependent clauses). Under Usage, the rubric includes similar items to the grammar section in the oral language section. For instance, it is concerned with correct singular/plural noun formations, correct gender formations, and article noun agreement (a/an and the).

Under Mechanics, the rubric is focused on the student’s ability to demonstrate their knowledge or ability to use sound-symbol correspondence (phonics), use capital letters at beginning of sentences, use capital letters with proper nouns, and uses correct final punctuation. As with many of the other examples shown in this rubric, it may be similar or radically different for Indigenous languages. For instance, in Ojibway syllabics, we would have completely different symbols, but we have sounds that are similar, or the same, as English sounds.

In 2009, the Oceti Sakowin Education Consortium published a workbook containing standards for Dakota/Lakota/Nakota language for fluent Native language speakers. Their focus was on oral language immersion. The workbook separates the standards into the following grade level groupings: K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12 (Oceti Sakowin Education Consortium, Citation2009, pp. 122–125). Table shows the standards for the K–2 grouping.

Table 9. Dakota/Lakota/Nakota language standards Grades K–2

In Table , the Dakota/Lakota/Nakota (DLN) language standards for K–2 are aligned with the Center for Applied Linguistics rubrics for oral language immersion for Grade 1. Although the table shows only the highest scoring level, Indigenous language teachers may want to show the lower scoring levels as well in a fully developed rubric for Indigenous language immersion classrooms. This alignment does not include a cross comparison for DLN standard 1.K‐2.5.1. which requires that the learner: “Speak appropriate vocabulary needed for simple conversation according to developmental age.” Since vocabulary is a category that is assessed for each standard and indicator under the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL) rubrics, it is not treated separately.

Table 10. Standards and rubrics alignment table

The alignment of the DLN standards with the CAL rubric is just one example of how Indigenous language immersion standards might be integrated into a general education assessment context. The nuances of other languages and preferences are certain to influence the exact nature of any relationship between general education assessment strategies and tribal standards.

5. Conclusion

The introduction and maintenance of Indigenous languages into the schools that serve Indigenous children and their peers should be handled with the utmost respect and care for the languages themselves, and for those who give and receive this very special knowledge. This chapter was intended to provide educators with ideas and examples surrounding the relationship between Indigenous language immersion and general education programs. The Indigenous Interdisciplinary Thematic Unit approach, evaluative tools and guidelines, lesson plan template, and standards alignment with assessment rubrics included in this chapter, were all carefully selected and presented. As Indigenous language immersion programs continue to grow and develop, it may be more commonplace to see a great deal of integration between these programs and general education. The revitalization of tribal education systems will no doubt be measured by the strength of Indigenous languages at its center.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided in part by the Region VIII Equity Assistance Center [grant number 81 FR 15665].

Acknowledgments

Chi-miigwech (many thanks) to Dr. Jan Perry Evenstad and the staff at the Region VIII Equity Assistance Center for their support of the Indigenous Language Immersion webinars development, and to Dr. Jioanna Carjuzaa for her never ending energy and commitment to the revitalization of Indigenous education systems (See https://www.montana.edu/carjuzaa/cbme/cbme.html).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martin Reinhardt

Dr Martin Reinhardt is an Anishinaabe Ojibway citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians from Michigan. He is a tenured associate professor of Native American Studies at Northern Michigan University, and serves as the president of the Michigan Indian Education Council. His current research focuses on revitalizing relationships between humans and Indigenous plants and animals of the Great Lakes Region. He is a former research associate for the Interwest Equity Assistance Center, and the former vice president for diversity and research for Educational Options, Inc. He has a PhD in Educational Leadership from the Pennsylvania State University, where his doctoral research focused on Indian education and the law with a special focus on treaty educational provisions. Martin has previously served as: the primary investigator for the Decolonizing Diet Project; Chair of the American Association for Higher Education American Indian/Alaska Native Caucus; Co-Primary Investigator for the Michigan Rural Systemic Initiative; and as an external advisor for the National Indian School Board Association (See https://www.montana.edu/carjuzaa/cbme/cbme.html).

References

- Aikenhead, G. (1996). Science education: Border crossing into the subculture of science. Studies in Science Education , 27 , 1–52.10.1080/03057269608560077

- Arlington County . (1997). VA Spanish partial-immersion program rubrics for writing and speaking in English and Spanish for Grades 1–5 . Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED421895

- Bilash, O. (2009). Oral production (speaking) in the second language classroom . Retrieved from https://www.educ.ualberta.ca/staff/olenka.bilash/best%20of%20bilash/speaking.html

- Carjuzaa, J. , & Kellough, R. (2016). Teaching in the middle and secondary schools (11th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

- Center for Research on Education, Diversity & Excellence . (2011). CREDE ECE-7 Rubric: An instrument to measure use of the CREDE standards in early childhood classrooms . Retrieved from https://manoa.hawaii.edu/coe/crede/sample-page/#rubric

- Cubins, E. (2000). Techniques for evaluating American Indian websites . Retrieved from https://www.u.arizona.edu/~ecubbins/webcrit.html

- Demmert, W. , & Towner, J. (2003). A review of the research literature on the influences of culturally based education on the academic performance of Native American students . Portland, ME: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

- Felder, R. (n.d.). Student-centered teaching and learning . Retrieved from https://www4.ncsu.edu/unity/lockers/users/f/felder/public/Student-Centered.html

- Fredericks, L. (2013). Research on culturally based education for Native American students. Part II of culturally based education for indigenous language and culture: A national forum to establish priorities for future research . Forum briefing materials. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ana/cbeforindigenouslanguageforum.pdf

- Gorski, P. (2012). Stages of multicultural curriculum transformation . Retrieved from https://www.edchange.org/multicultural/curriculum/steps.html

- Lindala, A. (2013). NAS 320 American Indians: Identity and media images (Course materials). Marquette: Northern Michigan University, Center for Native American Studies.

- McCarty, T. (2014, September 1). Teaching the whole child: Language immersion and student achievement. Indian Country Today . Retrieved from https://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/09/01/teaching-whole-child-language-immersion-and-student-achievement-156685

- McClusky, M. , & Ferguson, L. (2015). Evaluating American Indian materials and resources for the classroom . Montana Office of Public Instruction, Indian Education Division. Retrieved from https://opi.mt.gov/pdf/IndianEd/Resources/EvalAmIndianMaterials.pdf

- Michigan Department of Education . (2007). Social studies grade level content expectations: Grades K-8 . Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/mde/0,4615,7-140-28753_38684_28761—,00.html

- Moseley, C. (Ed.). (2010). Atlas of the world’s languages in danger (3rd ed., Memory of the peoples series). Paris: UNESCO.

- Oceti Sakowin Education Consortium . (2009). Dakota/Lakota/Nakota language workbook .

- Pease-Pretty On Top, J. (n.d.). Native American language immersion: Innovative native education for children & families . A project of the American Indian College Fund. Retrieved from https://www.collegefund.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ImmersionBook.pdf

- Reinhardt, M. , & Maday, T. (2005). Interdisciplinary manual for American Indian inclusion . Marquette: Northern Michigan University, Center for Native American Studies.

- Roberts, P. , & Kellough, R. (2008). A Guide for developing interdisciplinary thematic units (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Sadker, D. (n.d.). Some practical ideas for confronting curricular bias . Retrieved April 2, 2017, from Myra Sadker Foundation website https://www.sadker.org/curricularbias.html

- Slapin, B. , & Seale, D. (2006). Through Indian eyes: The Native experience in books for children . Berkley, CA: Oyate.

- United States, Federal Register . (2016). Vol. 81, No. 86/Wednesday, May 4, 2016/Notices.