Abstract

Culturally Responsive Education has been widely proposed as a mechanism to improve the academic achievement of minority and Indigenous populations. Instruction in heritage languages has been shown to produce desirable outcomes both on linguistic and academic measures. However, culturally responsive and immersion instruction faces a number of challenges; among them a lack of materials that (a) reflect and accurately represent ancestral knowledge and worldview, (b) are linguistically appropriate to elementary students, and (c) are aligned with state mandated outcomes in the content areas. In this paper we report on a university–school collaborative project, designed to develop Yup’ik language and cultural materials for elementary level Yup’ik-immersion and Yup’ik/English Dual Language schools in Southwest Alaska. Beginning with an overview of what we view as essential elements contributing to a strong and sustainable immersion program in K-12 education, we then discuss the process of the collaboration and tensions that arose during the course of the materials development project. Finally, we present two books developed as a result of this collaborative process.

Keywords:

Public Interest Statement

Children learn best when they see themselves and their culture represented in materials used in school instruction. However, particularly for Indigenous populations, few authentic materials are available. And those that are culturally appropriate are many times written in English. Even materials in the Indigenous language are oftentimes translated Western stories from basal readers. Materials created by Indigenous educators for Indigenous children are an essential element for successful Indigenous immersion schools. In this paper, we share what we have learned during a collaborative project involving Alaska Native educators and non-Native university faculty. We introduce what we view as essential elements for strong and sustainable Indigenous immersion programs, discuss the process of the collaborative project and present two books as examples of successful development of immersion materials.

1. Introduction

Culturally Responsive Education has been widely proposed as a mechanism to improve the academic achievement of minority and Indigenous populations. Furthermore, instruction in heritage languages has been shown to produce desirable outcomes both on linguistic and academic measures. In order to support language maintenance and revitalization, many Indigenous communities across the world are choosing immersion education (Hinton & Hale, Citation2001; Hornberger, Citation2008; Kipp, Citation2000). However, culturally responsive and immersion instruction face a number of challenges, among them a lack of materials that (a) reflect and accurately represent ancestral knowledge and worldview, (b) are linguistically appropriate to elementary students, and (c) are aligned with state mandated outcomes in the content areas.

This paper discusses what we consider essential elements of strong immersion programs with an emphasis on materials development. Specifically, we report on a university–school collaborative project, designed to develop Yup’ik language and cultural materials for elementary level Yup’ik-immersion and Yup’ik/English Dual Language schools in Southwest Alaska. We begin with an overview of what we view as essential elements contributing to a strong and sustainable immersion program in K-12 education. Next, we discuss the process of the collaboration and tensions that arose during the course of the materials development project; followed by a presentation of two books developed as a result.

2. Essential elements of strong immersion schools

The growth of immersion and dual language programs in the United States in general and schools seeking to revitalize and/or maintain Alaska Native/American Indian heritage languages in particular, is paralleled by a growing need for immersion teachers. This need for teachers becomes more complex with the added layer of training and experience required for teaching both content and the target language. While many university teacher education programs have tried to meet these needs, there is a serious lack of comprehensive education programs for immersion and dual language teachers in the United States (Cody, Citation2009; Walker & Tedick, Citation2000). In addition, while there are attempts by school districts and even post-secondary continuing education programs to provide professional development to in-service teachers, much of this training does not specifically address immersion pedagogy or theories of second language acquisition and teaching. There is also a lack of ongoing development of teachers’ knowledge of the language of instruction, which can present challenges for teachers trying to balance the teaching of the content and the target language (Fortune, Tedick, & Walker, Citation2008; Lyster, Citation2007; Met, Citation2008). This is a particularly critical challenge for those Indigenous Alaska Native/American Indian teachers who may themselves be “learners” of their heritage languages while at the same time being responsible for using it as the medium of instruction in their own classrooms.

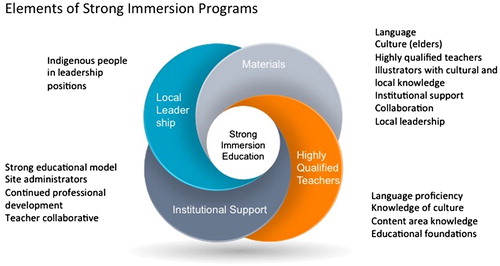

Yet, these challenges represent only one layer of a greater whole of the expertise and support network required for robust and sustainable immersion and dual language programs for K-12 education. It is the nested nature of the essential elements comprising this greater whole, which adds to the complexities of developing materials for immersion schools. The interrelated areas of highly qualified teachers, institutional support, local leadership and materials development work in conversation with one another in the macro socio-cultural and political contexts of the larger educational system and the micro-contexts (Walker & Tedick, Citation2000) of the individual and unique immersion and dual language classrooms.

In the age of The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), the status of being or becoming “highly qualified” received much attention both at the federal and state levels, elevating requirements for pre-service and in-service teachers. Yet, much of this attention was focused on how general classroom teachers could improve student achievement as measured by standardized test scores for the content areas of reading, writing, and math. For immersion and dual language teachers this focus presented a major gap in expectations for being “highly qualified.” Some states, like Alaska and Hawai’i, have instituted cultural standards to accompany curriculum standards. However, these standards alone do not address the need for expertise in second language acquisition and language teaching pedagogy. Specialized instruction in these areas is too often missing from pre-service and in-service teacher training. And, as stated previously, the notion of “proficiency” in the language is rife with complex issues that also encompass knowledge of orthography, grammar, academic/content vocabulary, etc.

However, while these components of language proficiency, cultural knowledge, content knowledge, knowledge of second language acquisition and pedagogy can be in many stages of development at any one time, they contribute to an ongoing process of “becoming” a highly qualified immersion or dual language teacher; and as such a critical element in the whole of a robust and sustainable immersion/dual language program. But, highly qualified teachers do not develop in a vacuum. They require help from two other essential elements: ongoing institutional support and local/community leadership.

Institutional support begins with a strong educational model. The Lower Kuskokwim School District (LKSD) for example, implements immersion and dual language programs. Both of these models are considered strong forms of bilingual education (Baker, Citation2006; Crawford, Citation1999), which promote additive bilingualism, foster positive attitudes toward the minority language and result in high levels of proficiency in both language and academic achievement. Both are supported through a strong empirical base and provide instruction through the medium of the minority language for a minimum of 50% of the day from Kindergarten to 6th grade.

These programs are developed and sustained through an active and knowledgeable personnel network—district office administrators and staff, site administrators and staff, teachers and aides—that collaboratively work together toward continued professional development and program improvement. In LKSD for example, a group of teachers in the Yup’ik immersion school approached their principal with the idea of starting a lesson study group to explore the problems of teaching reading in Yup’ik, using Storytown, an English-based basal reading program. The principal granted their request and integrated their meeting time into regular faculty development time; and the district office allowed the group to earn district professional development credits for their participation in the group. Thus, the institutional sanction (at the district and site administrative levels) allowed for the group to exercise local leadership, which could not have happened without buy-in and support from the district and site administrator.

In the next section, we will share what we learned as part of a university-school collaboration focusing on materials development for Yup’ik-medium schools.

3. Piciryaramta Elicungcallra teaching our way of life through our language

Central Yup’ik is the strongest of 19 extant Alaska Native languages. At the time of this writing, approximately 21,000 central Alaskan Yup’iks live in an area roughly the size of Arizona; 10,000 of whom have various levels of proficiency in their ancestral language (Marlow & Siekmann, Citation2013). According to Krauss (Citation1997), however, in only approximately one-quarter of all Yup’ik villages do children grow up speaking Yup’ik as their first language.

LKSD is the largest school district in the Yup’ik region serving approximately 4,200 students, the vast majority of whom are Yup’ik. A variety of program types have been employed in LKSD to support academic achievement and Yup’ik language maintenance and revitalization efforts, including, Ayaprun Elitnaurvik, a K-6 Yup’ik Immersion Charter School and several Yup’ik/English Dual Language schools. Since the 1970s, LKSD has undertaken numerous Yup’ik medium curriculum development efforts. Most pertinent here is the development of the K-3 Upingaurluta (Yup’ik cultural) thematic units. This framework consists of 12 thematic units, roughly structured around the six seasons that organize Yup’ik life, which are not, however, accompanied by sufficient materials and resources for teachers and students. The more recent implementation of Yup’ik/English Dual Language programs has furthermore highlighted the need for additional materials for meaningfully teaching Yup’ik language arts.

The Piciryaramta Elicungcalla grant is a collaboration between the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and two rural school districts serving predominantly Yup’ik children; LKSD and the Lower Yukon School District (LYSD). During the planning phase of the project (in 2009), a group of university faculty and local teachers held a series of meetings to discuss the most pressing needs facing Yup’ik medium schools in the region. The teachers were all Yup’ik women, all highly proficient in spoken and written Yup’ik, and all had extensive experience in Yup’ik medium classrooms (mainly in grades K-2). They represented a variety of communities, which are distinct in dialect and cultural practices. All participating teachers were also in the final stages of completing a Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics with an emphasis on Second Language Acquisition and Teacher Education (a grant funded project through the US Dept. of Education; see Marlow & Siekmann, Citation2013). Each had conducted teacher action research in their classrooms. Some relevant thesis titles are: Bridging Home and School: Factors that Contribute to Multiliteracies Development in a Yup’ik Kindergarten Classroom (Bass, Citation2010); Focus on Form through Singing in a First Grade Yugtun Immersion Classroom (Oulton, Citation2010); Yuraq: An Introduction to Writing (Samson, Citation2010); Focus on Form in Writing in a Third Grade Yugtun Classroom (Moses, Citation2010).

During the initial two-day planning meeting, these highly qualified and very experienced immersion teachers identified materials as the most pressing need they and their colleagues faced in their classrooms every day and was therefore selected as the main focus of the resultant grant. The teachers were excited to build on the existing materials, especially the Upingaurluta thematic units, as they are clearly linked to the Yup’ik way of life. In fact, the name they selected for their grant, Piciryaramta Elicungcallra, translates to “teaching our way of life through our language”. The teachers also mentioned concerns of linguistic and culture loss compared to the 1970s and 1980s; they were concerned that compared to when the thematic units were first developed, teachers and students are now less familiar with the concepts, practices and language of Upingaurluta and Yuuyaraq (Yup’ik epistemology). In particular, most children and even many of the younger teachers no longer engage in many of the traditional ritual and cultural events. Consequently, ceremonies and celebrations as well as traditional games and toys became two of the thematic units of the Piciryaramta Elicungcallra (PE) grant. Teachers expressed a sense of urgency to research and better understand these topics for themselves before adapting and integrating them into lesson plans and materials.

During the first year of the PE grant, teachers met regularly to select appropriate topics within each of the themes and to sequence them in age appropriate and culturally authentic ways. This process included many hours of interviews with respected elders as well as video recording and photographing seasonal cultural and subsistence activities such as hunting, fishing, and berry picking.

In 2009, as the PE grant got under way, LKSD adopted the Gomez and Gomez Dual Language Enrichment (DLE) program for communities choosing bilingual education (Gómez, Freeman, & Freeman, Citation2005). Except for the K-6 immersion school in Bethel, up to this point, most bilingual programs in the school district offered Yup’ik medium instruction only up to 2nd grade. The DLE model extended Yup’ik-medium instruction, particularly for social studies, science and language arts, through 6th grade. However, this time of restructuring of the Yup’ik medium instruction across the district lead to two interrelated tensions:

| (1) | The focus on academic rigor as defined by state standards, marginalizing cultural content, such as the Upingaurluta units. | ||||

| (2) | The need to develop Yup’ik reading curriculum to align with the English reading curriculum and extending it to 6th grade. | ||||

In response to these tensions, the PE stakeholders worked toward integrating Yup’ik cultural content into the core academic area of reading.

3.1. The tension between cultural and academic content

Research in the field of minority language education has shown that lesson plans building on students’ Funds of Knowledge (cultural background knowledge) result in higher overall learning outcomes as well as elevated language proficiency in both the ancestral language and English (Lipka, Citation1991; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, Citation1992; Moll & González, Citation1994). Models such as Culturally Responsive Schooling (Brayboy & Castagno, Citation2009; Hermes, Citation2007; McCarty, Citation2008), in particular, align closely with our Yup’ik materials development efforts. In Alaska, Culturally Responsive Schooling is often referred to as Place Based Education (Barnhardt & Kawagley, Citation1999), a term that emphasizes the importance of the local cultural, physical, and natural environment. More generally, the Continua of Biliteracy (e.g. Hornberger, Citation1989, 2003; Hornberger & Skilton-Sylvester, Citation2000) describe a framework for education in linguistically diverse settings that involves organizing mutually beneficial efforts in the areas of language planning, teaching and curriculum development, and research.

Unfortunately, as Hermes (Citation2007) points out, too often, there seems to be a distinction (be it explicit or tacit) between the cultural curriculum and its goals on the one hand, and the more general academic curriculum on the other hand. This distinction often results in a new set of problems, as Hermes (Citation2007) describes it in reference to the Ojibwe context:

Students interpret the split in curriculum (i.e. culture based curriculum versus academically or disciplined based curriculum) as an identity choice or dichotomy …. This disintegration of culture-based schooling presents a false dualism between academic success and cultural success. (p. 57)

In addition to the identity issues raised by Hermes, the separation of cultural and academic curricula also increases the vulnerability of the cultural curriculum. Programs and curricula that are not integrated into, or are not perceived by stakeholders (students, teachers, districts, and relevant communities) as the core elements of schooling, are more easily eliminated or relegated to positions of marginality.

During the first 10 years of the twenty-first century, NCLB-mandated high-stakes testing in English put pressures on, and in some ways marginalized, the use of the culturally based thematic units (Upingaurluta) in LKSD schools. As a result, teachers had to focus more of their classroom time and energy on standards-defined academic content, specifically reading, writing, and math. The Upingaurluta units, were not always viewed as directly addressing “academic” standards. This culturally based curriculum had to compete for time and acceptance with state and federal mandates. In fact, in the views of several of the teachers working on the grant, academic standards seemed to have pushed teaching based on Yuuyaraq to the very margins of education, even at the Yup’ik immersion school.

In the excerpt below (originally published in Siekmann et al., Citation2013), two Yup’ik immersion teachers talk about how the schedule changes were making it difficult to find the time to engage in place-based education.

Like, teaching the weather where I used to take the students out … And then going outside and then… observing and then listening to the weather, seeing it, touching it. I don’t do that anymore.

So why can’t you do that?

Well, I don’t know where I would put it in.

So tell me about that … why is that?

They have ELD [English Language Development] and then we have the R-CBMs [Reading Curriculum-Based Measurements]…

Reading, it’s supposed to be ninety minutes.

Reading, yeah.

Math is supposed to be ninety minutes, and writing.

And writing, and then I don’t know any other way to, to, where to put it [the Upingaurluta Yup’ik cultural knowledge units] in … unless there’s more added hours to school. (p. 9, 10)

T1 = Teacher 1.

T2 = Teacher 2.

I = Interviewer.

The authors conclude that: “Whether intended or not, at the time of this interview (summer 2010) academic standards seemed to have pushed teaching based on Yuuyaraq out of the classrooms even in the Yup’ik-medium schools” (p. 10). This supports the need to more fully integrate academic and cultural content into the overall curricular framework (Hermes, Citation2007), because if they are seen as separate, the cultural curriculum will likely be pushed aside in favor of the state mandated content.

As a result of this on-going tension, and because LKSD embarked on a major Yup’ik reading curriculum development project during the second year of the Piciryaramta Elicungcallra (PE) grant, stakeholders decided that participating in the development of Yup’ik books would best serve the need to integrate cultural and academic content. To be sure, PE teachers felt somewhat reluctant to shift the focus from the more overtly culture oriented social studies topics, so the more tightly controlled process of creating books that were aligned to state mandated standards and to the English reading curriculum. However, all agreed that the research conducted during the first year could be leveraged effectively to provide the content of books, whereas the reading standards (such as teaching plot and character, high frequency words and grammatical structures) could shape the genre and form of each book. Ultimately, creating reading materials that integrated cultural and academic content, rather than isolating Yuuyaraq epistemology from standards-based academic content, provided the opportunity for the creation of meaningful and culturally responsive materials in an area that lies at the heart of all elementary education.

3.2. Extension of and alignment with Yup’ik reading curriculum

As mentioned previously, the implementation of the DLE model extended Yup’ik medium language arts instruction to the 6th grade. However, the majority of existing reading materials had been designed for grades K-2. In addition to creating additional materials for grades 3–6, books also needed to be aligned with the English reading curriculum, because starting in 2nd grade, students in DLE receive language arts instruction in both English and Yup’ik. This means that the two curricula need to be aligned in such a way that they can provide meaningful and somewhat cohesive language arts instruction for the students. The district selected the Storytown reading program and proceeded to develop a Yup’ik reading curriculum that would work seamlessly with Storytown.

In working side by side with the larger district wide curriculum development project, the PE teachers identified the following areas as most important. Books were needed that:

| (a) | impart cultural knowledge; | ||||

| (b) | are linguistically and culturally authentic; | ||||

| (c) | are appropriate to grades K-6; | ||||

| (d) | target specific grammatical structures of Yup’ik; | ||||

| (e) | can be used within lessons focusing on state mandated reading standards; | ||||

| (f) | are narrative rather than descriptive. | ||||

During the last two years of the PE grant, participant teachers created 38 Yup’ik medium books for grades K-6. Sixteen books are for use in Kindergarten and 1st grade, six for 2nd grade; six for 3rd grade, six for 4th grade and four for 6th grade. All books are available for download at https://www.uaf.edu/pe/materials/.

On the whole, it has to be acknowledged that teachers felt generally more comfortable creating books for the lower grades. This can be attributed in part to the fact that most teachers had been teaching in lower elementary grades for most of their professional careers (remember most Yup’ik-medium programs in LKSD were K-2 only). Another factor was that books for the higher grades require higher levels of proficiency, particularly in written Yup’ik and more complex grammar. Several of the teachers did not feel comfortable in their own proficiency and were therefore somewhat intimidated by creating chapter books in Yup’ik.

In order to overcome these self-perceived limitations, teachers worked closely with elders, the linguistic and cultural knowledge bearers, to create authentic and appropriate representations of Yup’ik culture. Teachers often commented on how much they, themselves, were learning through talking with the elders, many of whom were their relatives. The generosity and wisdom of the elders cannot be underestimated; elders graciously shared time and expertise and teachers thrived on the elders’ support for the project. Teachers, time and again, acknowledged the importance of the elders, and whenever appropriate specific elders are listed on the book cover in a place of honor with the author(s) and illustrator.

In the lower grades, while materials and resources were more abundant, the teachers noted a need to focus more on the grammatical structure of Yup’ik, in order to support both oral language development and teaching children how to read. For these books, the combination of text and images was of particular importance. While some books utilized photographs taken by the authors themselves, others required the creation of original artwork. We also owe a debt of gratitude to the wonderful illustrators who made so many of the books come to life. It was important for cultural authenticity to work with local illustrators who could represent Yup’ik people, practices and artifacts and who worked collaboratively with the authors.

Throughout the book creation process, teachers kept in mind how the books might be integrated into the classroom. Teachers developed and implemented lesson plans about ceremonies and celebrations. What they learned often resulted in a book to be used by others. In addition, teachers involved their students in sharing their learning with others through a series of newspaper articles featuring student compositions and descriptions of the lessons. Some articles are written largely in Yup’ik, without English translations (see https://www.uaf.edu/pe/in-the-news/).

3.2.1. Examples of successful Yup’ik immersion materials

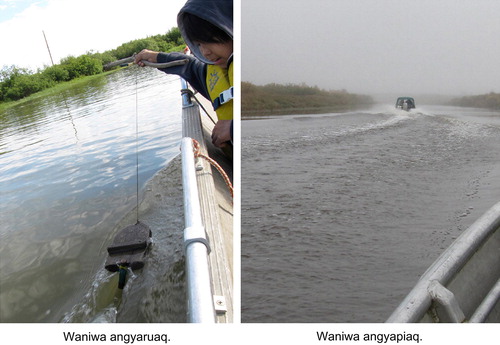

Next, we would like to share two examples from the Piciryaramta Elicungcallra project that we consider successful integration of cultural and academic content in materials development. The first example is a kindergarten book in the games and toys thematic unit, written by Sally Samson (Figure ), and the second example is a fourth grade book in the ceremonies and celebrations unit written by Catherine Moses (Figure ). For each, we first hear from the author herself followed by a brief discussion.

Samson about Waniwa Naanguat

The teachers in the materials development grant, Piciryaramta Elicungcallra, chose three themes to develop our books and lessons: ceremonies and celebrations, games and toys, and survival. Those were the biggest areas that were lacking books and materials. We used cameras and camcorders to capture our way of life in our area. Several teachers interviewed and recorded elders in their area. We used the photos and interviews to create books for our students.

Waniwa Naanguat was created for kindergarten students. I took photos of my students and also people and objects around our area to create the book. I wanted to showcase the different postbases that we use for real objects (-piaq) and pretend or fake objects (-ruaq). For example in one page a kindergarten student is dressed in a police outfit and he his imagining driving a police car as he pushes a lego piece on the floor. Under the photo is written tegusteruaq (a pretend police officer). On the next page is a photo of a police officer standing next to a police car. Below the photo is written tegustepiaq (a real police officer). Another set of pictures (see Figure ) shows a boy playing with a toy boat with the caption angyaruaq (a pretend boat); followed by a picture of real boat with the caption angyapiaq (a real boat). This book allows my immersion students to notice in the postbases. Most of the books do not showcase those changes.

Through repeating the pattern of noun+postbase and juxtaposing the two contrasting postbases (−ruaq and –piaq), students’ attention is drawn to both the meaning and the structure of the Yup’ik language. This allows even young learners to notice the salient features of the linguistic input provided through the text. According to some second language acquisition theories (Schmidt, Citation1993), noticing is one of the key processes underlying language development, especially in content-based instruction such as immersion education. This book, then, is an example par excellence of how teachers can focus on form (Long, Citation1991) within immersion education. As Swain (Citation1985, 1995, 2000) and others have pointed out, immersion education does not always lead to the levels of oral proficiency or linguistic accuracy desired and expected by stakeholders. Form focused instruction (Doughty & Williams, Citation1998), has been suggested as a mechanism to overcome the limitations of instruction relying solely on comprehensible input.

Moses about Uqiqurnariuq

One book I wrote is titled Uqiqurnariuq, with beautiful illustrations by Susie Moses. This book is about seal parties (uqiqut), a traditional community sharing event, usually held during springtime. This is still currently practiced in Nelson Island and nearby villages. I wrote it with elementary students in mind, specifically third and fourth grade students.

Because some rules pertaining to seal parties are complex, from my own experiences, I found that they are better understood when presented through similar age groups. With that in mind I decided to write about a young girl living in a typical village environment who has grandparents and other extended family. Within the story, a grandmother is making a grass basket and is listening to her grandchildren do a pretend seal party. Afterwards she sits her grandchildren near her and recounts her own childhood experiences and relates some rules pertaining to its practice. My hope is that this event will continue to be held each time when it is uqiqurnariuq (It is time for seal party).

The first illustration describes how seal parties have evolved to include celebrating certain events such as a baby’s birthday. The second illustration depicts the grandmother in the story as she is reminiscing about her own childhood experiences. In this way she relates to the joy felt by her grandchildren and feels compelled to share her knowledge and pass on that information.

This book makes a very complex and profound cultural practice accessible to elementary students. Rather than presenting the information through a non-fiction account, it is portrayed as realistic fiction. In reviewing existing materials that would be appropriate for 4th–6th grade students, teachers discovered a lack of books in the narrative genres. At the same time, many of the 4th–6th grade reading standards are based on the conventions of narrative texts, such as character, plot, dialog, and setting. In order to fill this gap, Moses created a narrative structure involving a grandmother and granddaughter who is about the same age as the children who are the target-audience of the book. The beautiful illustrations support the text through authentic representations. In comparison to the kindergarten book discussed above, it is apparent how much more complex the language is which is used in this book. The images are associated by paragraph length text consisting of multisyllabic words. It should be noted that Yup’ik is a polysynthetic language, meaning that several suffixes (also called postbases) and endings are attached to base word. This means that some Yup’ik words express the meaning of an entire sentence in English. When leveling Yup’ik books, teachers often referred to the number of postbases contained in the words to establish the complexity and difficulty level of a text.

4. Conclusion

For immersion educators, especially those teaching Indigenous languages, the process of materials development is essential, since materials cannot be purchased from national publishers. Creating meaningful materials is challenging, on-going, and requires sophisticated engagement with cultural and academic content. In short, while materials are among the elements of strong immersion programs, the creation of materials requires all the other elements (Figure ).

The creation of materials for immersion programs is generally undertaken by immersion teachers themselves, who need sufficient linguistic and cultural knowledge as well as expertise in the content areas, state mandated standards, second language acquisition and teaching and literacy development. Teachers need to be supported through meaningful professional development and need to have the institutional support of knowledgeable site administrators and district office personnel. Materials development takes time and money. School districts need to create opportunities for collaboration among teachers and communities as well as collaboration across schools and school districts. Ultimately, in order for truly culturally responsive education to be sustainable, local stakeholders need to move into leadership positions at all levels of the educational system. It is only through a series of overlapping long-term collaborations between the university, school districts, classroom teachers, elders, and community members that we were able to create what we feel are materials that support high-quality Yup’ik-medium schools throughout the regions. The tensions between English linguistic and cultural dominance and the need for strengthening Yup’ik language and culture remain, but we will continue to engage these issues collaboratively to give students an opportunity to learn their way of life through their language.

Funding

The work presented here was funded in part through two US Department of Education Piciryaramta Elicungcallra [grant number S356A090066]; Improving Alaska Native Education through Computer Assisted Language Learning [grant number S356A120055].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the other members of the Pugtallgutkellriit collaborative Agatha Panikgaq John-Shields and Sheila Cingarkaq Wallace for their contributions to our research collaborative. The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of all the teachers who participated in the Piciryaramta Elicungcallra grant.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sabine Siekmann

Pugtallgutkellriit is a Participatory Action Research Collaborative consisting of four Alaska Native PhD students and two non-Native faculty advisors. The PhD students are all Yup’ik women working to improve education of Yup’ik children in public schools in Alaska. All are highly proficient in their ancestral language (Yugtun), and each has many years of experience teaching in Yup’ik medium schools, such as Immersion, Yup’ik First Language, and Dual Language Education. Samson is completing her dissertation, Lesson Study in Yup’ik immersion reading instruction. Moses’ dissertation topic focuses on students’ language choice (either English or Yugtun) as they work on collaborative research projects in her Dual Language 3rd grade classroom. Parker Webster is an ethnographer whose research focuses on multiliteracies and multimodalities in Indigenous contexts. Siekmann’s research focuses on second language teaching and learning in Alaska Native contexts.

References

- Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism . Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Barnhardt, R. , & Kawagley, O. (1999). Education Indigenous to place: Western science meets Indigenous reality. In. G. Smith , & D. Williams (Eds.), Ecological education in action (pp. 117–140). New York, NY: SUNY Press.

- Bass, S. (2010). Bridging home and school: Factors that contribute to multiliteracies development in a Yup’ik kindergarten classroom ( Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks.

- Brayboy, B. , & Castagno, A. E. (2009). Self‐determination through self‐education: Culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous students in the USA. Teaching Education , 20 , 31–53.10.1080/10476210802681709

- Cody, J. (2009). Challenges facing beginning immersion teachers. American Council on Immersion Education Newsletter , 13 (3), 1–8.

- Crawford, J. (1999). Bilingual education: History, politics, theory, and practice . Los Angeles, CA: Bilingual Educational Services.

- Doughty, C. , & Williams, J. (1998). Focus-on-form in classroom second language acquisition . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fortune, T. W. , Tedick, D. J. , & Walker, C. L. (2008). Integrated language and content teaching: Insights from the immersion classroom. In T. W. Fortune , & D. J. Tedick (Eds.), Pathways to multilingualism: Evolving perspectives on immersion education (pp. 71–96). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Gómez, L. , Freeman, D. , & Freeman, Y. (2005). Dual language education: A promising 50–50 model. Bilingual Research Journal , 29 , 145–164.10.1080/15235882.2005.10162828

- Hermes, M. (2007). Moving toward the language: Reflections on teaching in an Indigenous-immersion school. Journal of American Indian Education , 46 , 54–71.

- Hinton, L. , & Hale, K. (Eds.). (2001). The green book of language revitalization in practice: Toward a sustainable world . San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Hornberger, N. (1989). Continua of biliteracy. Review of Educational Research , 59 , 271–296.10.3102/00346543059003271

- Hornberger, N. (Ed.). (2008). Can schools save Indigenous languages? Policies and practices on four continents . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillam.

- Hornberger, N. H. (Ed.). (2003). Continua of biliteracy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research, and practice in multilingual settings . Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Hornberger, N. , & Skilton-Sylvester, E. (2000). Revisiting the continua of biliteracy: International and critical perspectives. Language and Education , 14 , 96–122.10.1080/09500780008666781

- Kipp, D. (2000). Encouragement, guidance, insights, and lessons learned for Native language activists developing their own tribal language programs . Browning, MT: Piegan Institute.

- Krauss, M. E. (1997). Indigenous languages of the North: A report on their present state. In. H. Shoji , & J. Janhunen (Eds.), Northern minority languages: Problems of survival. Senri ethnological studies (Vol. 44, pp. 1–34). Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology.

- Lipka, J. (1991). Toward a culturally based pedagogy: A case study of one Yup’ik Eskimo teacher. Anthropology & Education Quarterly , 22 , 203–223.10.1525/aeq.1991.22.3.05x1050j

- Long, M. (1991). Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K. D. de Bot , R. Ginsberg , & C. Kramsch (Eds.), Foreign language research in cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 39–52). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/sibil

- Lyster, R. (2007). Learning and teaching languages through content: A counterbalanced approach . Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Co.10.1075/lllt.18

- Marlow, P. , & Siekmann, S. (Eds.). (2013). Communities of practice: An Alaska native model for language teaching and learning . University of Arizona Press.

- McCarty, T. L. (2008). Schools as strategic tools for Indigenous language revitalization: Lessons from Native America. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Can schools save Indigenous languages? Policy and practice on four continents (pp. 161–179). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230582491

- Met, M. (2008). Paying attention to language: Literacy, language and academic achievement. In T. W. Fortune , & D. J. Tedick (Eds.), Pathways to multilingualism: Evolving perspectives on immersion education (pp. 49–70). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

- Moll, L. C. , Amanti, C. , Neff, D. , & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice , 31 , 132–141.10.1080/00405849209543534

- Moll, L. C. , & González, N. (1994). Lessons from research with language minority students. Journal of Reading Behavior , 26 , 439–456.10.1080/10862969409547862

- Moses, C. (2010). Focus on form in writing in a third grade Yugtun classroom ( Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks.

- Moses, C. (2013). Uqiqurnariuq . Bethel: Lower Kuskokwim School District.

- Oulton, C. (2010). Focus on form through singing in a first grade Yugtun immersion classroom ( Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks.

- Samson, S. (2010). Yuraq: An introduction to writing ( Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks.

- Samson, S. (2013). Waniwa Naanguat . Bethel: Lower Kuskokwim School District.

- Schmidt, R. (1993). Awareness and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics , 13 , 206–226.

- Siekmann, S. , Thorne, S. , John, T. , Andrew, B. , Nicolai, M. , Moses, C. , … Bass, S. (2013). Supporting Yup’ik medium education: Progress and challenges in a university-school collaboration. In S. May (Ed.), LED2011: Refereed conference proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Language, Education and Diversity (pp. 1–25). Auckland: The University of Auckland.

- Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass , & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235–256). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Swain, M. (1995). The functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook , & B. Seidhofer (Eds.), Principles and practice in the study of language: Studies in honour of H.D. Widdowson . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In J. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97–114). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, C. , & Tedick, D. (2000). The complexity of immersion education: Teachers address the issues. The Modern Language Journal , 84 , 5–27.10.1111/modl.2000.84.issue-1