Abstract

The study aimed at identifying specific giftedness patterns that teachers discriminate against, and for, when nominating gifted students and focused on the identification of implicit theories adopted by teachers on the topics of intelligence, giftedness, and creativity in light of their specialization and experience. The study examined the differences between the effect of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on students’ performance. Profiles for types of gifted students were created, and implicit theory scales and performance assessment scales were implemented. The results showed that regardless of teachers’ specialization and experience, they tended to increasingly nominate students who are intellectually, creatively, and academically gifted. On the other hand, they are strongly biased against students who were gifted in visual arts, psychomotor, and leadership fields, as well as gifted underachievers. Gifted students’ teachers tended to incremental theories in all fields, compared to classroom teachers who tended to entity theories. The results revealed that differences exist in the effectiveness of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs, as gifted students’ performance was favorable in summer enrichment programs. Results showed that trainers’ experience with giftedness programs was a factor on students’ performance, and was dependent on the type of program, age of students, number of students, and trainers’ qualifications.

Public interest statement

This manuscript describes and analyses the system of identification and education of gifted and talented children in Saudi Arabia by focusing on an important topic in the field which is the implicit theory and its impact on the effectiveness of nomination of the gifted students and providing appropriate services that meet their needs. Moreover, it aims at studying the factors which effect on the enrichment programs. The outcome of this report might be of interest to policy-makers, educators, and teachers of gifted students.

1. Introduction

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has seen important changes in the perception and focus on gifted education over the course of the past decade. The process of the identification of gifted students received heightened interest, and the procedures of identification and encouragement of gifted students was a widely discussed topic that occupied the minds of students, teachers, and parents. Students identified as gifted students received programs and additional services regular students did not. In this context, several questions arose about the concept of “gifted,” how teachers can identify gifted students procedurally in regard to the patterns of the implicit theories for intelligence, giftedness, and creativity. The quality of the enrichment programs provided to the gifted, and the contributions of factors related to programs in gifted students’ performance were further factors in need of analysis.

The concept of giftedness is one of the endlessly debated issues among researchers in the field of giftedness in general (Callahan & Miller, Citation2005; Van Tassel-Baska & Brown, Citation2005), and educators and teachers of the gifted in particular. Topics discussed include their impact on formulating the policy and methods of identification of gifted students. The selection of students to be enrolled in the giftedness programs is dependent on the beliefs and concepts of the educators who organized the programs—based on their concept of giftedness—and the sorting and screening process more so than the instruments and scales used in the identification of gifted students.

Perhaps the most common problems related to the process of teachers’ nominations lies in the lack of a specific concept for gifted or creative students (Fleith, Citation2000; Lee, Citation1999; Smutny, Citation2000). Is the gifted or creative student the most intelligent or the most creative? What are the behaviors that reflect the creative gifted student? What about students with private giftedness in a specific field, such as linguistics, leadership, art, and psychomotor giftedness, or those who have high mental abilities, but average to low academic achievements? Which of these of students, exhibiting the above patterns of behaviors, deserves to be enrolled in gifted programs more from a teachers’ viewpoint?

Teachers’ nominations are one of the widely used procedures when selecting gifted students to join enrichment programs (Brown et al., Citation2005; Davis, Rimm, & Siegle, Citation2011; Hunsaker, Finley, & Frank, Citation1997; Renzulli, Siegle, Reis, Gavin, & Reed, Citation2009). These nominations are often used to form what is known as talent pool, which contains approximately 5–10% of the total number of students. These 5–10% are later tested to reduce the number down to the best 2–5% of students, who are admitted to enrichment programs. Students who are excluded at this stage lose the opportunity to join the services and programs of the chosen gifted students.

The stereotypes that were built by teachers about gifted students may be related to the beliefs they formulate about the concept of giftedness and the associated concepts of intelligence and creativity (Sak, Citation2004). In spite of that, the Saudi Ministry of Education had adopted a definition derived from the definition of Marland (Citation1972), which contains varied patterns of giftedness, focusing not only on mental giftedness. In contrast, in the field of education, both the identification and enrichment programs focus primarily on mental giftedness. These practices directly support or indirectly configure the stereotypical image of the gifted student for teachers for whom giftedness can be equated with a high level of intelligence, and/or high academic achievement.

Some researchers have suggested that the behaviors and attitudes of teachers are affected by their beliefs about the nature of intelligence (Deemer, Citation2004; Dupeyrat & Mariné, Citation2005). Lee (Citation1996) found that teachers who believe that intelligence is an entity-fixed trait treated their students differently from teachers who believe that intelligence is an incremental trait. Lee’s research found that teachers with entity beliefs are more focused on students’ abilities, and see failure as barriers. Conversely, teachers with incremental beliefs are more inclined to focus on strategy and effort in learning, and they see failure as opportunities to learn.

Many researchers (Dweck, Citation2012; Dweck, Chiu, & Hong, Citation1995; Runco & Johnson, Citation2002; Schroth & Helfer, Citation2009) confirmed that the implicit theories adapted by teachers about the concepts of giftedness, intelligence, and creativity were likely to act as reference criteria that can be used to judge the behavior of students, which leads to specific expectations. Those expectations in turn lead to practices that have significant effects on students’ behavior. Teachers’ expectations about the children’s abilities and their giftedness will determine how to respond to them and the type of opportunities that they will provide to the child. Some studies (Ngara & Porath, Citation2007) mentioned that the environmental and cultural context had an important role in the formation of these beliefs. These beliefs occupied a great importance when determining the gifted and creative students (Sak, Citation2004), and this was probably one of the reasons for the underrepresentation for some gifted students descended from different cultural categories or gifted low achievement students in gifted programs (Endepohls-Ulpe & Ruf, Citation2005; Moon & Brighton, Citation2008).

In regard to the importance of teachers’ nominations in the procedures of the identification of gifted students, it was important to study to what extent these nominations were affected by beliefs and concepts that teachers previously held on giftedness, creativity, intelligence, and personality. The current study addressed two main issues. Firstly, to identify the patterns of giftedness that teachers discriminated between when they nominated students to enrichment programs on the primary school level in various regions of Saudi Arabia and the influencing factors on this (specialization and experience). Secondly, to identify the nature of the implicit theories adapted by teachers about the concepts of giftedness, creativity, intelligence, and personality, and the ability of these theories to predict teachers’ nominations for gifted students.

Some researchers (Davis et al., Citation2011; Karnes & Bean, Citation2009) identified varied forms of enrichment opportunities in which they can provide special care for gifted students, including boarding schools and academies for the gifted, full day schools for the gifted students, special classes, pull out programs, and learning resource room, summer enrichment programs, school enrichment programs, weekend programs, and evening programs. Educators could provide enrichment programs that vary in depth according to the needs of gifted students and the sources of available support through these diverse forms.

Perhaps the most popular programs among those alternatives are school enrichment programs and summer enrichment programs (Coleman & Cross, Citation2005). In Saudi Arabia, the summer enrichment programs are considered as an important factor for fostering gifted students, and such services are spread across most areas of Saudi Arabia. Moreover, they are characterized by continuity as they held annually. The first of these programs began in 2000 through the establishment of 9 programs for male and female students, and the number of these programs continued to increase till they become 51 programs for male and female students in the summer of 2015 (King Abdulaziz & His Companion Foundation for Giftedness & Creativity, Citation2015).

In light of the increased interest in the summer enrichment programs, the current study aimed at studying the differences between the impact of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on students’ performance. The study aimed at measuring the direct effects of various factors on the gifted students’ performance (program type, gender, age of the students, the number of students in the program, the qualifications of the trainers, the number trainers’ participation in gifted programs).

2. The history of gifted education in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia tends to follow modern trends in education with regard to educational approaches and methods for regular students in general, and for gifted students in particular. These gifted students constitute a significant proportion of the schools in the Kingdom, whether they are in public or private schools. Thus, in order to achieve this vision of the best possible education for those gifted and talented students, the public policy gives gifted and talented education a priority.

The first summer enrichment programs for gifted students within Saudi Arabia were launched in the summer of 2000 by establishing nine programs for students, including both part-time and full-time programs in science and technology. These programs were conducted in collaboration with a group of government and private agencies. About 300 high school students were nominated for these programs (Aljughaiman & Ayoub, Citation2012). In addition, the King Abdulaziz and His Companions Foundation for Giftedness and Creativity (MAWHIBA) has established other specialized programs in addition to summer camps, including mentorship and enrichment as part of regular classroom instruction.

Another prominent activity of MAWHIBA to achieve its mission was the organization of scientific exhibitions for Saudi inventors to display their inventions and to connect them with investors and businessmen in the Saudi community. Moreover, the foundation held the first Regional Scientific Conference for Giftedness and Creativity in the Arab world in August of 2006, which hosted a group of specialists in giftedness and creativity. By the end of 2008, the foundation had created a long-term strategy, including the following five main initiatives. First, partnerships with distinguished schools were formed, including (1) the selection of schools and training of students, teachers and managers, and (2) the development of specific curricula for gifted education, as well as support strategies for parents. Second, enrichment activities were employed, including after-school programs, summer programs, competitions, and awards. Third, the “Young Leaders” program was established, which included scholarships, temporary training jobs, mentorship, and skills-building programs. Forth, creative environments were built, strategies for raising the awareness of educators for the needs of gifted students were implemented (e.g. training and workshops), and materials regarding best practices for gifted education were developed. Fifth, activities were organized to raise public awareness (e.g. the meaning of giftedness, creativity, and other related terms) via social media. Table contains a historical summary of the major developments and milestones in gifted education in Saudi Arabia over the past 25 years.

Table 1. Mean and standard deviations for teachers’ nominations to different patterns of gifted students

There are only two governmental institutions that foster gifted education in Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Education and MAWHIBA. The differences between the goals of the two institutions lie in the target groups for the services. While the Ministry of Education is responsible for creating special gifted programs, the MAWHIBA aims to provide services to the entire population of Saudi Arabia, working in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and universities in providing programs for gifted students. The main goals of the Ministry of Education regarding gifted education are set up as follows: the first goal is to establish an appropriate education policy in Saudi Arabia regarding the education of gifted children, adolescents, and adults. The second goal based on this policy is to create educational environments that allow gifted individuals to capitalize on their strengths and develop their giftedness. The third goal is to develop educational opportunities in schools and beyond to foster students’ giftedness. The fourth goal is to implement activities pertaining to prepare and train teachers and supervisors on methods of identification as well as finding ways to enhance the strengths of all students in all school subjects. The fifth goal is to provide a variety of educational opportunities for all students to identify and capitalize on their potential strengths.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

The participants in this study were 195 teachers from primary, middle, and high schools from different areas of KSA. The sample was divided according to specialization (gifted students’ teachers, n = 89; class teachers, n = 106) and years of teaching experience (>5 years, n = 98; <5 years, n = 97). While, the other sample consisted of 241 students their ages ranged from 13 to 15 years (M = 14.63 years, SD = 2.35). The sample was divided to (summer enrichment programs, n = 122; school enrichment programs, n = 119).

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. The profiles of gifted students

The researchers developed eight profiles that showed different patterns of giftedness behavior, with the function of identifying the type of student more likely to be nominated by teachers for gifted programs. The researcher asked the teachers to identify which students deserve to be nominated for gifted programs by using Likert and the estimates ranging from (1) I never agreed to his nomination to 7 fully agreed on his nomination. Moreover, they informed teachers that the students who achieve higher scores would be more likely to be accepted to the program. Each profile included a number of characteristics that referred to a specific type of giftedness pattern. None of these profiles included information about student’s grades on standardized cognitive tests or any other information about student’s grades on standardized cognitive tests. Teachers were given a general description of the performance and interests of each student. In light of the expectation of different teachers’ choices depending on teachers’ gender, an equivalent copy had been drafted to refer to different patterns of giftedness. Eight of these cases were as follows: a student had a high mentality but suffered in situations that require a non-traditional performance (mental field). A student had the ability to think in an authentically and unconventional manner, but he/she had a non-equivalent capabilities in the field of academic study in the classroom (the creative field). A student who had a very clear leadership characteristics, but he/she is not among the top 10% students in achievement (leadership field). A student had a clear talent in writing short stories (linguistic academic field). A student had a talent in mathematics (academic field in mathematics). A student had a very distinctive psychometric capabilities (psychometric field), but his/her achievement was average. A student had a distinctive artistic talent (visual arts fields), but his achievement was average. A student seemed to have a high mental abilities, but his/her achievement was low.

To test the validity of the content of these cases, the eight cases were exposed to a panel of seven professors who are specialized in giftedness and creativity. The panel identified each case in congruence with the model’s predictions, and they stated the accuracy of describing these eight cases. The test–retest reliability coefficient was (0.81). Teacher’s nominations of students were biased towards students who achieved high grades, while students who achieved low grades were disregarded.

3.2.2. Implicit theories scales

The researchers developed three measures for implicit theories in the light of Dweck theory (Dweck, Citation2000). These scales are: implicit theory for intelligence scale, implicit theory for giftedness scale, and implicit theory for creativity scale. Each scale consists of five items for assessing incremental theories and five items for assessing entity theories. The researchers used overall scores of scale. Participants were asked to report their agreement on a five-point Likert scale from agree strongly (5) to disagree strongly (1). As a result of the CFA, the items loading values were determined to range between 0.34 and 0.81. The fit indices of the implicit theory intelligence scale were χ 2/df = 1.59, RMSEA = 0.062, GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.91. These results indicated a good fit for the data. In the present sample, the Cronbach alpha was 0.78.

The researchers chose to deal with the total score of the scales of implicit theories rather than dealing with the incremental and entity dimensions in each scale. So that the high-grade on each scale referred to the tendency of the individual to the implicit incremental theory, while low-grade referred to the implicit entity theory.

3.2.3. Performance assessment scale

To assess the gifted student’s performance, the researchers developed a scale in light of the scales of previous scholarship (e.g. Ayoub & Aljughaiman, Citation2016; King Abdulaziz & His Companion Foundation for Giftedness & Creativity, Citation2015; Lee & Olszewski-Kubilius, Citation2007; Van Tassel-Baska et al., Citation2003). This scale consisted of 30 items, and included eight subscales (scientific knowledge, scientific research, critical thinking, creative thinking, problem solving, leadership, motivation, and autonomy). Answers were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). The scale was administered to a sample of 247 students to measure the validity of performance assessment scale by confirmatory factor analysis. As a result of the CFA, the fit indices of the scale were observed to be at a good fit χ 2/df = 2.06, RMSEA = 0.071, GFI = 0.91, AGFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.92. The Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) of the scale were 0.84.

3.3. Procedures

To identify the giftedness patterns that teachers discriminate when nominating gifted students, and to identify the implicit theories adopted by teachers about intelligence, giftedness, and creativity, the researchers applied the giftedness profile and the scales of implicit theories on the sample in collaboration with the gifted education departments in various regions of Saudi Arabia in the academic year 2015–2016. Teachers were not given any criteria for the nomination of gifted students, so teachers can nominate students based on their own concepts and personality theories. To study the differences between the effect of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on students’ performance and to identify the direct effects of factors related to programs on performance, a performance assessment scale was applied. The participants were chosen randomly from summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs. The performance assessment scale was distributed to three teachers, who were asked to assess students’ performance during their participations in these programs.

4. Results

4.1. Patterns of giftedness

To identify the giftedness patterns that teachers discriminate when nominating gifted students, the two researchers calculated means for each category of teachers according to specialization (teachers of gifted students, and teachers of regular classes), and experience (more than 5 years’ experience, and less than 5 years’ experience). Table clarified the mean scores and standard deviations for teachers’ nominations to different patterns of gifted students.

Specialization: The results of Table indicated that teachers’ highest nominations were in favor of the mentally gifted students (M = 6.63), creative students (M = 6.47), and academically gifted students in math (M = 5.84), followed by linguistically gifted students (M = 5.52). The teachers’ nominations to gifted students in art (M = 5.12), psychomotor gifted students (M = 4.79), gifted students in leadership (M = 4.66), and the underachieving gifted students (M = 4.39) came at the bottom end of their nominations with narrow margins.

Teachers’ nominations in regular classes were most likely to creative students (M = 6.23), and for mentally gifted students (M = 6.04), while their nominations for academically gifted students in math (M = 5.72), and linguistically gifted students (M = 5.38) followed in a middle position with narrow margins. Whereas their nominations for gifted students in art (M = 4.71), gifted students in leadership (M = 4, 64), psychomotor gifted students (M = 4.56), and the underachieving gifted students (M = 4.36) came at the end of their nominations with equal degrees.

Experience: The results revealed that teachers experienced more than 5 years were more likely to nominate mentally gifted students (M = 6.46), creative students (M = 6.35), and academically gifted students in math (M = 5.77), linguistically gifted students (M = 5.43). While their nominations to gifted students in art (M = 5.05), gifted students in psychomotor (M = 4.91), the gifted students in leadership (M = 4.65), and underachieving gifted students (M = 4.32) were equally low. The highest nominations of teachers experienced less than 5 years were in favor of creative students (M = 6.23), followed by mentally gifted students (M = 5.96), and academically gifted students in math (M = 5.71), linguistically gifted students (M = 5.44). Gifted students in art (M = 4.85), and then psychomotor gifted students (M = 4.75), leadership students (M = 4.64), and finally gifted students in underachievement came at the end of their nominations (M = 4.24).

4.2. Teachers’ implicit theories

To identify the implicit theories adopted by teachers about intelligence, giftedness, and creativity, the means were calculated in light of specialization (gifted students teachers, regular classes teachers), and experience (more than 5 years’ experience, less than 5 years’ experience (Table ).

Table 2. Means and standards deviations for teachers’ implicit theories

The results in Table indicated that gifted students’ teachers were more likely to adopt incremental implicit theories in the field of intelligence, giftedness, and creativity (4.95, 4.56, 4.38, respectively), compared to teachers of regular classes who were more inclined to adopt entity implied theories in the three fields (2.13, 2.70, 2.71, respectively). Additionally, teachers who had more than five years’ experience were more inclined to the incremental implicit theories (4.93, 4.20, 4.51, respectively) compared to teachers who had less than five years’ experience. Teachers who had less than five years’ experience were more inclined to entity implicit theories (2.39, 3.12, and 3.16, respectively).

4.3. Summer enrichment program vs. school enrichment program

The independent samples t-test was carried out to evaluate the differences between the effect of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on students’ performance.

The results of the independent samples t-test (Table ) indicated that there were significant differences between the effect of summer program and school program on scientific knowledge (t = 10.10, p < 0.01), scientific research (t = 8.52, p < 0.01), critical thinking (t = 8.90, p < 0.01), creative thinking (t = 6.45, p < 0.01), problem solving (t = 8.61, p < 0.01), leadership (t = 9.03, p < 0.01), motivation (t = 7.36, p < 0.01), autonomy (t = 11.10, p < 0.01), and total performance (t = 9.79, p < 0.01). All the differences were in favor of summer enrichment program. The values of effect size ranged from (0.15) to (0.34). These values referred to a high effect size.

Table 3. Independent samples t-test for the differences between the effect of summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on students’ performance

4.4. Structure equation model

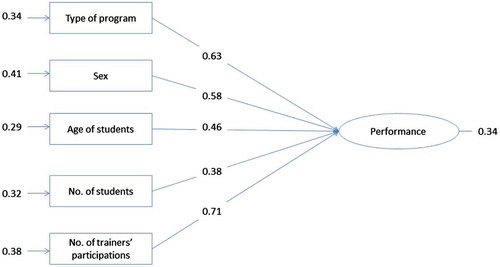

To identify the direct effects for each of: the type of program (part-time, full-time); sex (male, female); age of students (elementary, medium, secondary); number of students (less than 25 students, more than 25 students); trainers’ qualification (Bachelor, high studies); the number of trainers’ participations in the programs (≤1, ≥2) on the performance of gifted students were considered. Path analysis using LISREL software (Version, 8.8) was used to find the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The model is presented in Figure .

Standardized path coefficients and t values were observed to be between the type of program and students performance as 0.63, t = 7.24, p < 0.05, sex and performance as 0.58, t = 6.30, p < 0.05, age of students and performance as 0.46, t = 5.41, p < 0.05, number of students and performance as 0.38, t = 4.27, p < 0.05, trainers participations and performance as 0.71, t = 10.29, p < 0.05, between trainers qualifications and performance as 0.19, t = 1.73, p > 05, respectively.

These values indicated that the model fit the data adequately. Examining the fit indices, χ 2 = 164.03, df = 139, p > 0.01, χ 2/df = 1.18, values indicated that the model fit the data adequately. The RMSEA = 0.06, GFI = 0.94, AGFI = 0.93; NFI = 0.94, values indicated a good level of fitness. Additionally, predictor variables accounted for (72%) of the percent of the variance in performance. According to the findings, the model was verified and confirmed that the predictor variables had positive and significant effects on performance.

Furthermore, it is clear that the most powerful influences on performance were trainers’ participations, type of program, sex, age of students, number of students, and trainers’ qualifications respectively.

5. Discussion

The results of the current study suggested that teachers regardless of their specialization or years of experience in teaching biased in their nominations in favor of mentally, creatively, and academically (language and math) gifted students. In contrast, the teachers were clearly biased against underachieving gifted students and those gifted in art, psychomotor, and leadership. Conclusively, these last patterns of gifted students were most at risk of marginalization and loss of opportunity in the Saudi educational system. This result could be interpreted through two things: the educational practices are directed at mentally, creatively, and academically gifted students only, whereas little attention was directed at gifted students in other fields. These practices might have significantly contributed to the formation of concepts and beliefs such as the linking of the concept of giftedness to high mental ability, or intelligence quotient (IQ). Anyone who had followed the practices of the identification of gifted students in Saudi Arabia found that they mainly focused on the IQ and academic achievement. Thus, gifted students in other fields had fewer opportunities of joining a giftedness program. The cultural habits and values prevailing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia may not have given support to some kinds of giftedness, such as artistic, drawing, and musical giftedness as a result of the perception of teachers and parents, who discriminate against gifted students in these fields. A study of (Alamer, Citation2010) conducted on Saudi giftedness program nominations revealed that teachers and parents could not appreciate some behavioral characteristics for gifted students for religious and cultural reasons. Also, the appreciation of giftedness in the fields of music, visual arts, and leadership was marginal, especially for females. The result of the study was consistent with the study of Schroth and Helfer (Citation2009) which showed that teachers did not appreciate the giftedness in the motor, musical, and visual arts fields. Sternberg (Citation2007) confirmed that the ignorance of the cultural factors prohibiting the identification of gifted students might lead to a loss of a number of gifted students and the nomination of some non-gifted students. According to the implicit quintet theory, as suggested by Sternberg and Zhang (Citation1995), the standard of social value is one of the basic criteria in identifying giftedness.

Some teachers, especially gifted students’ teachers might be aware of such giftedness and their importance, but the existing practices and the utilized methods of identification did not provide the opportunity to gifted students with talents to join these programs. Enrichment programs are directed at the mentally and academically gifted students. As a result, teachers found that the nomination of mentally gifted students is preferable to nominating other students. This may clarify that gifted students’ teachers were biased in the most categories to nominate mentally gifted students more than the teachers of regular classes. Furthermore, this explained that the teachers with more experience biased more to mentally gifted students than less experienced teachers.

Perhaps it was stupendous that the category of leadership giftedness came at the end of all nominations. This result was consistent with the study of Brighton, Moon, Jarvis, and Hockett (Citation2007) which showed that the teachers did not direct more attention or more appreciation to gifted students exhibiting the characteristic of leadership. Their conclusion may be attributable to teachers’ belief that leadership giftedness cannot be identified objectively, particularly as the skill is difficult to develop.

Concerning the implicit theories, the results revealed that giftedness teachers were the most likely to adopt incremental implicit theories in the fields of intelligence, giftedness, and creativity compared to regular classes teachers. The teachers with more experience were more inclined to incremental implicit theories compared to less-experienced teachers who were more inclined to entity implicit theories. The results indicated that teachers of gifted students were more inclined to the formation of the incremental implicit theories in the field of intelligence, giftedness, and creative compared to regular classes teachers which were more inclined to adopt entity implicit theories. This result can be understood through the scientific background and the teaching practices for gifted students’ teachers that make them the most familiar with the nature of giftedness in general. The assumption could be made that teaching gifted students for several years can play an important role in the formation of these incremental beliefs. This may raise a dialectic issue about whether the educational practices were the reason behind the formation of these beliefs, or that the adapted beliefs by teachers and organizers of giftedness programs were responsible for such practices. The relation seemed to be reciprocal, as that beliefs can guide practices, and practices can support the formation of beliefs.

Regarding the impact of experience, the results revealed that teachers with more than five years of experience were more inclined to incremental implicit theory in the field of intelligence, whereas teachers with less than five years of experience were more inclined to entity implicit theories. The cumulative results which they had as a result of teaching practices helped to form more mature beliefs about the viability of mental characteristics to be modified over time through experience and learning. However, there were no differences in the fields of giftedness, creativity, and personality.

Regarding the differences between summer enrichment programs and school enrichment programs on the gifted students’ performance, the results indicated that there were differences in performance in favor of summer enrichment programs. Several studies Hughes (Citation2003) Neihart, Reis, Robinson, and Moon (Citation2002), Tieso (Citation2005) agreed that summer enrichment programs provided beneficial services, opportunities, and experiences for gifted students to work with others with the same interests and abilities in the program. Teachers benefited from the freedom of the curriculum, through which they could propagate the development of desirable social traits among students through forming flexible groups within the activities.

Additionally, trainers’ participations, type of program, sex, age of students, number of students, and trainers’ qualifications, respectively, had a discernable influence on students’ performance. The results of these studies agreed with Aljughaiman and Ayoub (Citation2013); Aljughaiman et al. (Citation2009), Cannon, Broyles, Seibel, and Anderson (Citation2009), King Abdulaziz & His Companion Foundation for Giftedness & Creativity (Citation2014).

6. Conclusion

Identifying the different kinds of giftedness that teachers biased against made us more aware of which gifted students were most likely to be marginalized and passed over in the current system. The results of the study lead us to profess the need for teachers to be increasingly aware of certain types of gifted students, so they cease being passed over during the nomination process. Additionally, there is a need to pay increased attention to underserved talents in the future while planning talented programs in general and procedures of identification in particular. Work must be done to raise awareness among teachers through in-service training to lead them to recognize marginalized talents; talents at risk of loss as a result being overlooked in the screening stage. Teachers should be trained to focus on students’ strengths more than on their weaknesses in the nomination of students in gifted programs. The recognition that no single definition for gifted students, fit for all programs, can exist must be made, as well as the realization that students may be gifted in different ways. A student may be gifted in one program, but not in another. Implicit theories about giftedness, intelligence, and creativity concepts can have numerous educational implications not only on the identification process of gifted students, but also on the development of gifted students’ education.

Those who are in charge of planning enrichment programs are encouraged to pay attention to the importance of developing appropriate programs to include those gifted students that may have been marginalized or deprived from years of participation in gifted programs (Aljughaiman & Ayoub, Citation2012). Any committee responsible for developing a program for gifted students should firstly care about the determination of what a “gifted” student is, followed by how to recognize them procedurally, and then connect all of this with the nature of the programs that will be provided for them. It is important to think about all of these issues in order to build a policy that can be defended in the field of gifted education.

7. Challenges and planning for the future

In sum, we perceive a number of challenges and opportunities for gifted education in Saudi Arabia. A current key challenge for gifted education in Saudi Arabia A current key challenge for gifted education in Saudi Arabia is an orientation towards a worldwide “knowledge community,” which requires an increase in attention to gifted education, excellence, innovation, and creativity. The increase in sharing knowledge about tools and services requires considerations of scientific, technological, administrative as well as technical areas, which in turn requires increased attention for giftedness, excellence, and creativity. Similarly, there is a global competition in various aspects of life that is based on excellence and innovation. This trend becomes evident in that most Arab countries joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) over the past 10 years. The growing global competition to attract and recruit high able people has prompted many highly able individuals to leave the Arab world in order to pursue a global career. However, the Saudi Arabian economy in particular is in need of diversification based on providing excellence, scientific, and technical leadership.

The opportunities include: (1) a firm conviction plus a large and comprehensive awareness among the leaders of Saudi Arabia about the importance of educating and supporting gifted students; this is shown through their personal interest in talent institutions, initiatives, and ideas provided by experts in this field; and (2) a general acknowledgment of the need to develop gifted and talented programs in Saudi Arabia, and the acknowledgment of the existence of a big gap compared to developed countries in this field. Thus, this acknowledgment provides an opportunity because it is the main motivation to pursue the development of these programs in the first place. The needs of gifted students are diverse. In addition to academic needs, individual needs, social needs, and thinking needs, the power of self-fulfillment is also important. Effective ways to meet the needs of gifted students involve applying different methods that will lead to academic acceleration, enrichment, and other experiences. However, programs for gifted students are inadequately effective unless they are carefully planned, adequately prepared, and conscientiously implemented in schools. Furthermore, the programs for gifted students need to be flexible, as well as capable of development and adaptation by teachers to meet the needs of the individual students. In this regard, gifted education in Saudi Arabia still has a long way to go.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdullah M. Aljughaiman

Abdullah Aljughaiman is a full professor at the Special Education Department, Education College in King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. He is currently a member of the Saudi Parliament and the president of the International Research Association for Talent Development and Excellence (IRATDE). The primary focus of Prof Aljughaiman’s professional activities is the development and education of gifted and talented students. He has published books, book sections, and peer-reviewed articles on the identification of and services for gifted children.

Alaa Eldin A. Ayoub

Alaa Ayoub is a full professor at the Gifted Education Department, College of Graduate Studies, Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain. He has published many studies, and articles on the field of educational psychology and the identification of gifted students. He has made many contributions in preparing scientific scales and tests. He is also the coauthor and the translator of some specialized books. His research interests are in the identification of gifted students and statistical programs.

References

- Alamer, S. (2010). Views of giftedness: The perceptions of teachers and parents regarding the traits of gifted children in Saudi Arabia (Unpublished PhD). Monash University, Clayton.

- Aljughaiman, A. M. , & Ayoub, Alaa E. A. (2012). The effect of an enrichment program on developing analytical, creative, and practical abilities of elementary gifted students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted , 35 , 153–174.10.1177/0162353212440616

- Aljughaiman, A. M. , & Ayoub, Alaa E. A. (2013). Evaluating the effects of the oasis enrichment model on gifted education: A meta-analysis study. Talent Development & Excellence , 5 , 99–113.

- Aljughaiman, A. , Ayoub, A. , Maajeeny, O. , Abuoaf, T. , Abunaser, F. , & Banajah, S. (2009). Evaluating gifted enrichment program in schools in Saudi Arabia . Riyadh: Ministry of Education.

- Ayoub, A. , & Aljughaiman, A. (2016). A predictive structural model for gifted students’ performance: A study based on intelligence and its implicit theories. Learning and Individual Differences , 51 , 11–18.10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.018

- Brighton, C. M. , Moon, T. R. , Jarvis, J. M. , & Hockett, J. A. (2007). Primary grade teachers’ conceptions of giftedness and talent: A case-based investigation (RM07232). Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut.

- Brown, S. W. , Renzulli, J. S. , Gubbins, E. J. , Zhang, W. , Siegle, D. , & Chen, C. H. (2005). Assumptions underlying the identification of gifted and talented students. Gifted Child Quarterly , 49 , 68–79.10.1177/001698620504900107

- Callahan, C. M. , & Miller, E. M. (2005). A child-responsive model of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 38–51). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511610455

- Cannon, J. G. , Broyles, T. W. , Seibel, G. A. , & Anderson, R. (2009). Summer enrichment programs: Providing agricultural literacy and career exploration to gifted and talented students. Journal of Agricultural Education , 50 , 27–38.

- Coleman, L. J. , & Cross, T. L. (2005). Being gifted in school: An introduction to development, guidance, and teaching . Waco, TX: Prufrock.

- Davis, G. , Rimm, S. , & Siegle, D. (2011). Education of the gifted and talented (6th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Deemer, S. (2004). Classroom goal orientation in high school classrooms: Revealing links between teacher beliefs and classroom environments. Educational Research , 46 , 73–90.10.1080/0013188042000178836

- Dupeyrat, C. , & Mariné, C. (2005). Implicit theories of intelligence, goal orientation, cognitive engagement, and achievement: A test of Dweck’s model with returning to school adults. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 30 , 43–59.10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.01.007

- Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality and development . Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

- Dweck, C. S. (2012). Implicit theories. In P. A. M. Van Lange , A. W. Kruglanski , & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 43–61). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.10.4135/9781446249222

- Dweck, C. S. , Chiu, C. , & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgment and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry , 6 , 267–285.10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

- Endepohls-Ulpe, M. , & Ruf, H. (2005). Primary school teachers’s Criteria for the identification of gifted pupils. High Abilities Studies , 16 , 219–228.

- Fleith, D. S. (2000). Teacher and student perceptions of creativity in the classroom environment. Roeper Review , 22 , 148–153.10.1080/02783190009554022

- Hughes, P . (2003). Autonomous learning zones . Paper presented at the 10th Conference of the European Association for Learning and Instruction, Padova, Italy.

- Hunsaker, S. L. , Finley, V. S. , & Frank, E. L. (1997). An analysis of teacher nominations and student performance in gifted programs. Gifted Child Quarterly , 41 , 19–24.10.1177/001698629704100203

- Karnes, F. A. , & Bean, S. M. (2009). Methods and materials for teaching the gifted (3rd ed.). Waco, TX: Prufrock.

- King Abdulaziz & His Companion Foundation for Giftedness and Creativity . (2014). Measuring quality summer enrichment programs . Riyadh.

- King Abdulaziz & His Companion Foundation for Giftedness and Creativity . (2015). Definition of enrichment programs . Riyadh.

- Lee, K. (1996). A study of teacher responses based on their conceptions of intelligence. Journal of Classroom Interaction , 31 , 1–12.

- Lee, L. (1999). Teachers’ conceptions of gifted and talented young children. High Ability Studies , 10 , 183–196.10.1080/1359813990100205

- Lee, S. , & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2007). The effects of a service-learning program on the development of civic attitudes and behaviors among academically talented adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted , 31 , 165–197.10.4219/jeg-2007-674

- Marland, S. P., Jr . (1972). Education of the gifted and talented: Report to the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Commissioner of Education . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Moon, R. R. , & Brighton, C. M. (2008). Primary teacher’s conceptions of giftedness. Journal for the Education of the Gifted , 31 , 447–480.10.4219/jeg-2008-793

- Neihart, M. , Reis, S. , Robinson, N. , & Moon, S. (2002). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

- Ngara, C. , & Porath, M. (2007). Ndebele culture of Zimbabwe’s views of giftedness. High Ability Studies , 18 , 191–208.10.1080/13598130701709566

- Renzulli, J. , Siegle, D. , Reis, S. , Gavin, M. K. , & Reed, R. E. (2009). An investigation of the reliability and factor structure of four new scales for rating the behavioral characteristics of superior students. Journal of Advanced Academics , 21 , 84–108.10.1177/1932202X0902100105

- Runco, M. A. , & Johnson, D. J. (2002). Parents’ and teachers’ implicit theories of children’s creativity: A cross-cultural perspective. Creativity Research Journal , 14 , 427–438.10.1207/S15326934CRJ1434_12

- Sak, U. (2004). About creativity, giftedness, and teaching the creatively gifted in the classroom. Roeper Review , 26 , 216–222.10.1080/02783190409554272

- Schroth, S. T. , & Helfer, J. A. (2009). Practitioners’ conceptions of academic talent and giftedness: Essential factors in deciding classroom and school composition. Journal of Advanced Academics , 20 , 384–403.10.1177/1932202X0902000302

- Smutny, J. F. (2000). How to stand up for your gifted child: Making the most of kids’ strengths at school and at home . Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing Inc.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2007). Cultural concepts of giftedness. Roeper Review , 29 , 160–165.10.1080/02783190709554404

- Sternberg, R. J. , & Zhang, L. F. (1995). What do we mean by giftedness? A pentagonal implicit theory. Gifted Child Quarterly , 39 , 88–94.10.1177/001698629503900205

- Tieso, C. (2005). The effects of grouping practices and curricular adjustments on achievement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted , 29 , 60–89.10.1177/016235320502900104

- Van Tassel-Baska, J. , Avery, L. , Struck, J. , Feng, A. , Bracken, B. , Drummond, D. , & Stambaugh, T. (2003). The William and Mary classroom observation scales- revised . Williamsburg, VA: Center for Gifted Education, The College of William and Mary-School of Education.

- Van Tassel-Baska, J. , & Brown, E. F. (2005). An analysis of gifted education curricular models. In F. A. Karnes & S. M. Bean (Eds.), Methods and materials for teaching the gifted (2nd ed., pp. 75–105). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.