Abstract

Students often say they hate group projects, because they don’t want their grade held hostage by someone else’s effort (or lack thereof) and/or because they’ve had the experience previously of having to do other people’s work for them. For the instructor, the challenge is to figure out how to provide students with the valuable lessons and learning experience of collaborative work while avoiding the common pitfalls. How should one, and how can one, balance individual accountability—one’s grade is a reflection of one’s own work—with the shared responsibility of meaningful collaborative work—one’s grade is a reflection of the group’s effort and ability to work together? To answer this question, this essay offers a tripartite ethical framework with which to critically evaluate the design of group projects and assignments. Building upon the foundation provided by the ethical philosophies of Emmanuel Levinas and Mikhail Bakhtin, and supplemented by a generalized account of accountability, this essay will argue that a fully effective collaborative assignment should implement strategies designed to foster three poles of ethicality: responsibility, answerability, and accountability. To clarify and illustrate this tripartite ethical framework, three principal best practices will be discussed: the assignment of precisely defined individual “captainships,” a requirement for students to complete a qualitative self-assessment, and the inclusion of a detailed “non-compliance policy.” Finally, a required peer-assessment, mandatory rehearsal presentation, and meta-cognitive classroom activity will also be discussed, both in terms of how they fit within the tripartite framework and how they complement and reinforce the aforementioned strategies.

Public Interest Statement

Students often say they hate group projects because they don’t want their grade to suffer from another student’s lack of effort or because they don’t want to have to do other students’ work for them. For the instructor, the challenge is to determine how to provide students with the valuable lessons and learning experience of collaborative work while avoiding the common pitfalls. How can individual accountability (and individual assessment) be effectively balanced with the shared responsibility (and collective assessment) of meaningful collaborative work? This essay offers a tripartite ethical framework with which to critically evaluate the design of group projects and assignments. Specifically, this essay (1) asserts that a fully effective collaborative assignment should implement strategies designed to foster three poles of ethicality: responsibility, answerability, and accountability, and (2) shares some best practices to achieve that goal, including assigned “captainships,” a qualitative self-assessment, and the inclusion of a “non-compliance policy.”

1. Introduction

Every semester, when I first announce that there will be a group project, I can hear groans emanating from the class. Many students complain about how much they hate group projects. Yet, at the end of the semester, when I conduct a last-day-of-class discussion session in which I solicit their feedback about the course, a majority of students report that they “actually” enjoyed the group project, and a surprising number report that it was their favorite part of the course. This is admittedly due, in part, to the fact that many students were fortunate to have worked in a functional group of good students, all reasonably diligent in their work and responsible to other members of the group. That surely contributes to a positive experience. But I believe that these positive end-of-semester reports are also due to the way in which I have designed the group project assignment.

In my experience, the primary causes for students’ resistance to and dislike for group projects—often bordering on hatred—seem to be that (i) students are worried that their own grade in the course will suffer because of another student’s poor work or lack of concern for their grade, and/or (ii) with their increasingly hectic schedules, students do not want the added burden of needing to do additional work to compensate for what other members of the group fail to complete. If an instructor is to remain committed to collaborative assignments, built on the belief that such experience is beneficial to, if not indispensable for, the students’ ongoing academic and lasting professional success, they must find a way to mitigate, at least to some degree, these dangers, which seem inherent to group work. Above all, the instructor must find a way to balance individual accountability with the shared ownership and responsibility of meaningful collaborative work. In other words, students who do more or less work should earn a higher or lower grade while simultaneously having their success or failure depend upon the level of collaboration of the group as a whole. If the scales tip too much in one direction, animosity and resistance can ensue. If they tip too much in the other direction, the result can be what is essentially an individual rather than group experience. Admittedly, this is not an easy balance to strike.

For the past several years, my general solution has been to design major group projects and assignments with (i) a balance between individual assessment and group assessment so that an individual student’s grade is not entirely hostage to other members of their group (see Johnson & Johnson, Citation2004, p. 32), and (ii) a mechanism of individual accountability by which students simultaneously have specific duties within the group while not feeling compelled to fulfill the duties of other members of the group. The first part of this solution has been relatively simple. For any major group project or assignment in my courses, approximately half of each student’s grade is for individual work—typically submitted as draft stages toward the final group product(s)—with the other half for the final group product(s), such as a group presentation or co-authored report. Dealing with the second part of this solution has been more challenging. The most positive results, to my estimation, have come from the incorporation of “Captainships” and a “Non-Compliance Policy” into major group assignments. While these will be discussed in greater detail below, as well as illustrated in Appendices A and C, for now the following definitions may suffice: the “Captainships” assign each member of a group specific responsibilities, such as being the Team Manager (responsible for submitting initial proposals, setting up meetings, reminding everyone of deadlines, etc.) or the Presentation Captain (responsible for scheduling a rehearsal, coordinating any audio/visual equipment needs, etc.); and the “Non-Compliance Policy” provides a protocol by which a group can essentially fire a particular member of the group from any aspect of the project if he/she is not doing his/her work, thereby protecting their own grades from that member’s lack of effort and without having to do that member’s work for them.

My informal observations in the classroom indicate that these two strategies have helped to (1) make students more cognizant of their responsibilities to other group members by explicitly assigning and defining those responsibilities, and (2) ensure that any group dysfunction that occurs rises to an explicit point of discussion within the group, forcing students to consciously consider options and reflect upon their own complicity. Indeed, although these strategies are not intended to increase the incidence of dysfunction within student groups, they do force confrontation with various aspects of group dynamics. For example, instead of a student (or students) simply doing the work that another student (or students) has failed to do, these strategies invite the first student(s) to consider their various options and compel the second student(s) to acknowledge the impact of their behavior upon the group. Moments of minor or major group dysfunction thereby become teachable moments rather than mere opportunities for students to reaffirm their hatred of group projects. The explicit responsibilities of the Captainships and protocol of the Non-Compliance Policy have seemed to increase the likelihood that individual students will at least be aware of, if not actually fulfill, their individual roles in the group and contributions to the group’s performance.

In sum, and despite any formal empirical study to validate these impressions, this approach to the aforementioned challenges of group projects seems to have been working quite well, in terms of both increasing the quality of student work (as demonstrated by students’ grades on group projects) and decreasing the level of student discontent (as revealed in students’ end-of-semester feedback). However, as I continued to work to improve the students’ experience and their level of engagement and learning, I sought theoretical models of student responsibility and accountability that might illuminate the dynamics of the students’ group project experience. I wanted not just to share “best practices” with colleagues (which I have done, both within my department and at professional conferences), but also to develop a better theoretical understanding of how and why these strategies were working, as I believed they were (and continue to believe they are). I wanted to move from best practices reporting to a richer theoretical framework and articulation of how and why those strategies have been effective. To do that, I required a theoretical model that would confirm (or contradict) my suspicions regarding the how and why of the effectiveness of those best practices of my group assignment design. Unfortunately, I did not find the sort of theoretical framework which I sought in either the existing pedagogical literature on student group work with which I was familiar or in any cursory search of philosophical literature on moral responsibility. [And the model of (student) responsibility and accountability that I would eventually deploy would, as it turns out, both confirm and contradict different aspects of those best practices].

In short, although there is a body of pedagogical literature on student collaboration and group work—see Section 2—that literature does not provide a theoretical model of student responsibility (within the context of collaborative work) sufficient to illuminate how students simultaneously come to (i) acknowledge their responsibilities to other students and (ii) take ownership for their own actions. Similarly, although there is a body of philosophical literature on different types of accountability—see Section 2; most notably Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) work distinguishing attributability, answerability, and accountability as the “three distinct conceptions of responsibility” necessary for a “comprehensive theory of moral responsibility” (p. 602)— that literature distinguishes after-the-fact levels of (a person’s) culpability or blameworthiness rather than revealing the before-the-fact dynamics of (a student’s) acknowledgment and ownership of their moral obligations. In short, this body of literature concerns different ways in which a person might be “held responsible” (Shoemaker, Citation2011, p. 602) by others for their actions. This might be characterized as an adjudicatory framework. By contrast, what I sought was a pedagogical framework: a theoretical model that would illuminate the ways in which students come to understand their moral obligations to classmates and come to accept ownership for their satisfaction of, or failure to fulfill, those obligations. In other words, I sought not a philosophical model for the adjudication of moral infractions—whereby one might assess, for example, whether a particular individual can be held fully accountable, only answerable, or minimally attributable for a specific moral infraction—but instead a pedagogical model for the examination of how students (a) recognize, understand, and respond to their obligations to other students, and (b) recognize, understand, and “own up to” their actions. Stated differently, as an instructor I am not concerned primarily with judging students’ moral infractions—indeed, Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) taxonomy might prove extremely useful to those who serve on an honor council—but in facilitating students’ growth as moral agents. The latter requires me to attend to the (as stated above) before-the-fact dynamics of a student’s acknowledgment and ownership of their moral obligations. Consequently, I sought a theoretical model which would illuminate those dynamics, and such a model seemed lacking in both the pedagogical and philosophical literatures.

2. Literature review

First, let us examine some of the pedagogical literature on student collaboration and group work. In the widely regarded work of Johnson and Johnson (Citation2004), although they provide a thorough and detailed account of how the “group” itself functions as an entity—particularly useful is chapter one, “The power of cooperative groups” (pp. 1–22)—they provide far less detail and insight regarding how the “individual” functions within the group. In discussing ways to structure individual accountability into group assignments, Johnson and Johnson (Citation2004) state that “everyone has to do his or her fair share of the work” and that “holding all members accountable” is crucial (p. 29). Lacking is a closer examination of fairness and accountability in terms of how those concepts interact in shaping ethical responsibility at the individual level. Similarly, in discussing how five basic elements of cooperation should inform the intentional design of group assignments, Johnson and Johnson (Citation2004) note that both group accountability and individual accountability must be assessed for a group assignment to function well (p. 32). But here too, lacking is a more extensive investigation of what individual accountability means and how an individual student might understand their accountability to themselves (intra-personally), to other members of the group (inter-personally), and to the group as a whole (collectively). To be fair, none of what I found lacking (for my own purposes) was necessarily part of the authors’ explicit scope or objective, but it did signal a common weakness in the literature. Generally speaking, existing literature on student group work appears to focus on the articulation of best practices, operating out of a model of (reciprocal) student–student interaction that does not interrogate the dual ethical posture of the individual student as always already (and simultaneously) both agent and team member. What I sought was an ethical framework that would help illuminate the inner dynamics of the individual student’s ethical responsibility.

Second, let us examine some of the philosophical literature on the related concepts of responsibility, attributability, answerability, and accountability. Perhaps most prominent is Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) examination of attributability, answerability, and accountability as “three distinct conceptions of responsibility” which together provide a “comprehensive theory of moral responsibility” (p. 602; see also Shoemaker, Citation2015). As stated above, these concepts delineate three different assessments of an individual’s culpability or blameworthiness for their actions. For example, Shoemaker (Citation2011) considers it imperative that any comprehensive theory of moral responsibility (qua assignation) be able to account for “the difficult case of the psychopath” (p. 602)—or alternatively, children, persons with cognitive deficiencies, etc. Shoemaker builds his theoretical framework in response to the work of Scanlon (Citation1998, Citation2008) and Smith (Citation2005, Citation2007),Footnote 1 and seeks to answer (practically) and distinguish (theoretically) questions concerning what it means for a person to be attributable for an action, what it means for a person to be answerable for an action, and what it means for a person to be accountable for an action. Without going into all the details of these scholars’ various lexicons, the point is that it is morally significant to acknowledge that a person may be physically responsible for an action (i.e. attributability) without needing to apologize for it (i.e. answerability)—for example, when a “good Samaritan” accidentally harms a person they are trying to assist—or that a person may need to “take responsibility” for an action (i.e. answerability) without being required to make reparation for it (i.e. accountability)—for example, a child who, without meaning to, hurts another child and needs to “check on them” by asking “Are you okay?” and saying “I’m sorry you got hurt.”

Unfortunately, these various distinctions and (partly competing) conceptual apparatuses all stem from a larger adjudicatory framework that is primarily interested in better understanding how to assess and assign blame for unethical behavior. In simplified layman’s terms, these concepts ask: how do we decide whether someone is morally responsible for their actions, and how do we decide whether they deserve punishment? But such questions are not—and I suspect should not be—the primary focus in the undergraduate classroom. They may become focal in cases of student misconduct or cheating, but not in the daily interactions that occur between students within the context of a group project. Rather, what is of primary concern in an educational context is the intentional facilitation of students’ abilities to (1) recognize the interpersonal/inter-professional obligations intrinsic to any collaborative endeavor and (2) take ownership of their own actions, behaviors, and patterns of conduct as they pertain to those obligations. Indeed, we might view these two abilities as “professional skills,” “habits of mind,” or “dispositions,” the development of which is central to our educational mission (see Costa & Kallick, Citation2014; Murray, Citation2016).

Having not found a fully satisfactory theoretical framework with which to conceptualize students’ acknowledgment and ownership of their moral responsibilities in either educational literature on group work or philosophical literature on responsibility, answerability, and accountability, I eventually turned to Murray’s (Citation2000) synthesis of the ethical philosophies of Emmanuel Levinas and Mikhail Bakhtin. That synthesis combined the insights of Levinas’s notion of “responsibility” and Bakhtin’s notion of “answerability” in order to yield a “fuller dialogical communicative ethics” (p. 133). At first glance, this self-proclaimed “communicative” model promised to give more attention to the interpersonal recognition of and dialogic responsiveness to moral responsibility of paramount concern in the classroom than to an adjudicatory framework seemingly more applicable in a courtroom. According to this model, responsibility to the Other and answerability for one’s own actions represent the two fundamental poles of (the axis of) ethical experience. For my purposes in the undergraduate classroom, the resulting Bipartite Model of Ethics promised to illuminate the inner dynamics and complementarity of the two central elements of my group project assignments, Captainships and a Non-Compliance Policy, by helping to reveal how those elements were facilitating both students’ acknowledgment of their obligations to classmates and students’ taking ownership for their behaviors and actions in and out of the classroom.

At first glance, the Captainships seemed to function at the pole of Responsibility and the Non-Compliance Policy at the pole of Answerability. In other words, the paired philosophies of Levinas and Bakhtin suggested that the synergy of these two strategies was largely responsible for their effectiveness. Specifically, the Captainships and Non-Compliance Policy powerfully combine two moral perspectives—outward-looking “responsibility” and inward-looking “answerability”—to heighten students’ acknowledgment of their roles and obligations within the group as well as their eventual acceptance of responsibility for their own actions. Upon closer inspection, however, this Bipartite Model of Ethics revealed three unexpected things about my group project design. First, I realized that the Non-Compliance Policy was not functioning the way I had initially suspected and that another mechanism was needed to fully address the dimension of Answerability. Second, I realized that the effectiveness of the Non-Compliance Policy suggested an extension of the Levinas-Bakhtin framework into a Tripartite Model of Ethics for the examination of student group projects. Third, I realized that additional elements of my group project assignments fit into the resulting Tripartite Model, thereby clarifying their role within the overall dynamics of student collaborative work.

In the remainder of this essay, I will provide a brief summary of Levinas’s notion of “responsibility,” Bakhtin’s notion of “answerability,” and the Bipartite Model of Ethics that results from the synthesis of those two theories. I will then discuss how the Captainships address the pole of Responsibility within the Bipartite Model, and how the Non-Compliance Policy suggests the addition of a third pole, Accountability, to yield a Tripartite Model of Ethics. Originally hypothesized to primarily concern Answerability, the reassignment of the Non-Compliance Policy to the (added) pole of Accountability simultaneously necessitates the incorporation of a Self-Assessment assignment to explicitly address the pole of Answerability. Finally, I will discuss how additional elements of the major group project assignment of my course, namely a Peer-Assessment, Rehearsal Presentation, and meta-cognitive group descriptions classroom activity, fit into the Tripartite Model of Responsibility/Answerability/Accountability.

3. Responsibility and answerability: A Bipartite Model of Ethics

In “Bakhtinian answerability and Levinasian responsibility: Forging a fuller dialogical communicative ethics,” Murray (Citation2000) sought to “contribute to our understanding of the dialogical nature of human existence and the ethics of communication by examining the inner structure of the relationship between self and Other” (p. 133). In that work, Murray (Citation2000) suggested that:

the combination of Emmanuel Levinas’s notion of the call to responsibility and Mikhail Bakhtin’s notions of dialogism and answerability provides a more complete account of human dialogue and the ethical dimension of the communicative encounter. It does so by theorizing the respective functions of self and Other within the interhuman dialogue. As an extension of dialogical ethics, the synthesis of Bakhtin and Levinas demonstrates that ethics is itself a dialogical phenomenon. Ethics is a conversation between one’s own-most answerability and the calls to responsibility of Others. (p. 133)

In other words, Murray (Citation2000) sought to differentiate “the inner dynamics” and “originary structure” of dialogical ethics (p. 134), a differentiation which promises now to illuminate the dynamics of the student group project experience. More specifically, the Bipartite Model resulting from the synthesis of Levinas’s notion of “responsibility” and Bakhtin’s notion of “answerability” theorizes the respective ethical postures of self and Other within the interhuman dialog. As Murray (Citation2000) argued, “the self is called into responsibility by the Other—whose very presence is the originary source of the ethical imperative—and the self retains its freedom of ethical response through its answerability for its actions” (p. 134). Moreover, because ethics is itself a dialogical phenomenon, ethics is itself comprised of two poles, with each pole corresponding to the respective role that each participant plays within the dialogical encounter (p. 135). In other words, Bakhtin and Levinas are describing two different but interdependent dimensions of the ethical encounter, which is itself dialogical in nature (p. 136).

From this starting-point, this essay can now discuss in greater detail the first pole of the Bipartite Model of Ethics, Responsibility. As Murray (Citation2000) argued, the ethical philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas continues that of Bakhtin. Levinas’s notion of “the call to responsibility” is a supplement to Bakhtin’s notions of answerability. Because the call of ethics originates from the Other, according to Levinas, ethics is consequently not a pre-existent attribute of the self. Rather, the self is “summoned” into its responsibility to the Other by the Other (p. 136). Ethics is conceived by Levinas as a relationship of responsibility for the Other. But it is a responsibility that belongs to the Other and emanates from the “call” of the Other’s “face.” “The Other becomes my neighbor precisely through the way the face summons me, calls for me, begs for me, and in so doing recalls my responsibility, and calls me into question” (Levinas, Citation1989a, p. 83). It is not a responsibility that originates in me or that I bring to my relation with the Other. “Responsibility for my neighbor dates from before my freedom in an immemorial past” (Levinas, Citation1989a, p. 84). According to Levinas (Citation1989b), a person’s responsibility for another human being does not come from an ethical principle or moral imperative—though it may be described by such. Rather, a person’s responsibility to another human being resides within the very relationship with that other being, a relationship in which one can be concerned with another human being without having to “assimilate” them (p. 254). Summarizing this reconception, Handelman (Citation1989) states that ethics is “not conceived as a determinate set of beliefs or practices but the most original ‘ontological’ structure which is the very ‘relation to the other’” (p. 145). The revolutionary insight offered by Levinas is his location of the “drive” for altruism outside the self in the “call” and “face” of the Other: “[E]thics as responsibility for the Other is not an ontological feature of the self, but is rather the foundational feature of the Other within the self-Other architectonic” (Murray, Citation2000, p. 141).

For Levinas, this means that subjectivity itself is called into question by responsibility. As DeBoer (Citation1986) illuminated the implication of Levinas’s position, “I am not ‘constituted’ by the other, for in my joyous existence I was already an independent being; rather, I am judged by the other and called to a new existence. The encounter with the other does not mean the limitation of my freedom but an awakening to responsibility …. I owe to the other [not my existence, but] my responsibility” (p. 110) (See Figure ).

Figure 1. Levinas’s notion of responsibility. Responsibility originates in the Other indicated by all CAPS; focus on my responsibility to the Other indicated by

Similarly, with this understanding of the first pole, this essay can now discuss in greater detail the second pole of the Bipartite Model of Ethics, Answerability. According to Bakhtin, “the architectonic of the actual world” consists of “I, the other, and I-for-the-other” (Citation1993, p. 54), and answerability can be understood, therefore, as a description of the nature and function of the ‘I’ within that architectonic (Murray, Citation2000, p. 136).Footnote 2 Bakhtin offers the “answerable act” as “the ontologically definitive feature of the subject” (p. 137). According to Bakhtin (Citation1993), every thought a person has and every deed a person performs is unique and individual. Indeed, a person’s existence is understood by Bakhtin as “an uninterrupted performing” of individual thoughts and deeds. In that regard, a person’s very existence is (nothing but) the sequence of unique thoughts and deeds that they perform (p. 3). Furthermore, it is this uniqueness from which arises “the answerability of a performed act” (Bakhtin, Citation1993, p. 59). Bakhtin (Citation1993) explained further that: “An answerable act or deed is precisely that act which is performed on the basis of an acknowledgment of my obligative (ought-to-be) uniqueness.… The answerably performed act … is the foundation of my life … for to be in life, to be actually, is to act” (p. 42). In other words, “one only exists insofar as one acts answerably in and upon the world. To be answerable, for Bakhtin, is primarily to act in such a fashion as to stand behind and committed to those acts, to claim one’s actions as one’s own, as verification of one’s existence as a deed-performing ‘series of acts’” (Murray, Citation2000, p. 138) (See Figure ).Footnote 3

Figure 2. Bakhtin’s notion of answerability. Answerability is constitutive of being indicated by all CAPS; focus on introspection upon one’s actions (as one’s being) indicated by

Synthesizing these two philosophies of ethics yields a rich, Bipartite Model of ethical Responsibility/Answerability—please note now that neither term, in its more casual usage, adequately captures the full sense of ethics. As Murray (Citation2000) argued, neither answerability alone nor responsibility alone provides a full accounting of both self and Other within the self-Other architectonic. Bakhtin’s notion of answerability is incomplete because its focus (within the self-Other architectonic) is the self. “[T]hough enmeshed within the architectonic of self and Other, [answerability] is ultimately centered on the self as answerable actor” (pp. 142–143). In Baktin’s own words, “the answerable act is, after all, the actualization of a decision” (Bakhtin, Citation1993, p. 28); answerability arises out of the individual’s “unique center of value” (Bakhtin, Citation1993, p. 59). Murray (Citation2000) continues that Levinas’s notion of responsibility is similarly incomplete because its focus (within the self-Other architectonic) is the Other. For Levinas, (the summons to) responsibility is ultimately a phenomenological account of the Other. Ethics, understood as the call to responsibility, originates in the Other. Hence, (p. 142) the two notions are complementary and inter-dependent.

In sum, “For Bakhtin, the ‘answerable act’ represents the primary ontological feature of the individual within the architectonic of self and Other.… For Levinas, the call to responsibility represents the primary metaphysical feature of the Other within the architectonic” (Murray, Citation2000, p. 136).Footnote 4 See Figure . Together, the synthesis of responsibility and answerability reveals that: “our very existence is a dialogicity in which the freedom of the self is always already in dialogue, face-to-face, with the call to responsibility of the Other. We are always already answerable in our world and in our actions as a result of our ontological nature, but we are always already called to responsibility by the Other as a result of the Other’s metaphysical nature. The dialogue that we are is a dialogue between self and Other, between answerability and the call to responsibility (Murray, Citation2000, p. 148).Footnote 5

4. Responsibility, answerability, accountability: A tripartite model of ethics

As I began to apply the aforementioned Bipartite Model of Ethics to my major group project assignments, it seemed at first glance that the incorporation of Captainships was fulfilling the dimension of Responsibility by providing students with clearly defined responsibilities to other members of the group—i.e. what other members of the group were relying upon and calling upon them to do—and that the incorporation of a Non-Compliance Policy must therefore be fulfilling the dimension of Answerability. With regard to Captainships—refer to Appendix A for an example of defined captainships—this element of the group project assignments did indeed seem to “fit” the first pole (Responsibility) insofar as the Captainships clarify for students what their responsibilities are to other members of the group, instead of some members realizing “I guess we have to do everything” or some members thinking (or making excuses of) “I didn’t know what I was supposed to do.” Clearly defined Captainships help ensure that every student knows what their specific responsibilities are, and therefore functions primarily at the pole of Responsibility. See Figure .

With regard to the Non-Compliance Policy, however—refer to Appendix C for an example of such a policy—further reflection suggested that it was not, in fact, serving the function of the second pole (Answerability), as I had too quickly assumed. The Non-Compliance Policy was not functioning primarily to help individual students acknowledge (and “own up to”) their answerability within the group—although sometimes it also did that to some extent. Rather, it was functioning primarily as a tool of accountability for other students to use in order to enforce the responsibilities of the Captainships. In other words, without the Non-Compliance Policy as a tool for other students in the group—and, similarly, without “the Grade” as a tool for the instructor—the Captainships do not adequately “motivate” students to fulfill their defined responsibilities. To be blunt, without the threat of a failing grade (for some students) or the fear of not getting an A (for other students), the Captainships can become a suggestion rather than a central requirement of the assignment.

This recognition, of how the Non-Compliance Policy was not working within the Bipartite Model of ethical Responsibility/Answerability, yielded two insights. First, if I were taking the Bipartite Model of Ethics seriously, I needed to incorporate into the group assignment an element more explicitly targeted at the pole of Answerability. To that end, I have resurrected a Self-Assessment assignment in which students evaluate their own level of work within the group. [Unfortunately, I had been using an assessment tool that focused more on peer-assessment than on self-assessment (see Johnson & Johnson, Citation2004, pp. 120–143 and pp. 144–170, on peer assessment and self-assessment, respectively). I have now realized that peer-assessment has more to do with Accountability—see below—whereas Answerability is likely best addressed through Self-Assessment]. Indeed, I became convinced that an intentionally designed Self-Assessment tool would prove a better mechanism by which to foster students’ meta-cognitive reflection on their Answerability. More specifically, my strong suspicion, especially after talking with colleagues about their group project assignments and mechanisms of student self-assessment, is that a Self-Assessment tool will work better as an exercise in Answerability if it is not about a grade. In other words, it should be a qualitative self-assessment aimed at having students take ownership of their successes and failures rather than assigning themselves a grade. It should get them to focus on conducting their own honest self-inventory rather than on (guessing at or trying to influence) external evaluation. [The theoretical argument for decoupling the Grade (qua Accountability) from the Self-Assessment (qua Answerability) will be clarified]. See Figure and please refer to Appendix B for a sample Self-Assessment tool.

Second, though the Non-Compliance Policy did not seem to be about Answerability—at least not primarily—the presence of a mechanism by which students could effectively kick out a member of the group who is not doing their work has seemed very effective as a strategy for increasing student engagement in group projects. So where does it fit? This puzzle led to the realization that perhaps a third pole needed to be added. Not a third dimension of the ethical encounter itself—which I believe the synthesis of Levinas and Bakhtin adequately and correctly describes—but a mechanism of externally-imposed evaluation that helps compel students to engage themselves in the bipartite structure of ethical Responsibility / Answerability. A third notion is needed: Accountability.

Recalling the discussion of Shoemaker (Citation2011) and others on the related concepts of attributability, answerability, and accountability, we now have need for that adjudicatory framework, which was previously set aside. To be sure, the notion of “answerability” as derived from Bakhtin’s dialogic philosophy is not the same as that deployed by Shoemaker. Bakhtin’s notion is at root an existential, if not ontological, account (of a person’s very being) rather than a juridical one. So too, the notion of “responsibility” as derived from Levinas’s ethical philosophy is not the same as the umbrella term used by Shoemaker and others. Levinas’s notion is at root a phenomenological account of the appearance (in being) and acknowledgment (in perception) of the primordial reality of our obligation to the other. But having put those two conceptions together to yield a Bipartite Model, we find that still missing from that model, at least in the educational context of collaborative work, are the familiar mechanisms of extrinsic motivation—most notably, grades. It is those mechanisms of accountability that get students to do the activities and assignments that were designed to facilitate their learning and, in this case, moral development.

Consequently, as a complement to Levinas’s notion of “responsibility” and Bahktin’s notion of “answerability”—as discussed at some length above—“accountability” is reintroduced here, in an admittedly generic manner, to refer to any mechanism of external assessment of moral behavior. Such a generic use of the term accountability seems warranted insofar as it is often deployed in less technical applications, such as Painter and Hodges’s (Citation2010) analysis of the beneficial policing role of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart upon mainstream news media. For Painter and Hodges (Citation2010), “accountability ‘refers to the process by which the media are called to account for meeting their obligations’ (McQuail, Citation1997, p. 515)” (p. 257). In the classroom, if not also in professional journalism, such measures of accountability hopefully serve not only to make one answer for one’s actions but also to more fully recognize and understand one’s obligations in the first place. In other words, this essay is not concerned with distinguishing how a particular student in a particular situation might be, in Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) language, merely “attributable” rather than “answerable,” or “answerable” rather than fully “accountable.”Footnote 6 Instead, this essay is concerned with better understanding how mechanisms of accountability in the classroom can facilitate the primary paired-objective of facilitating students’ abilities to (1) recognize the interpersonal / inter-professional obligations intrinsic to any collaborative endeavor and (2) take ownership of their own actions, behaviors, and patterns of conduct as they pertain to those obligations.

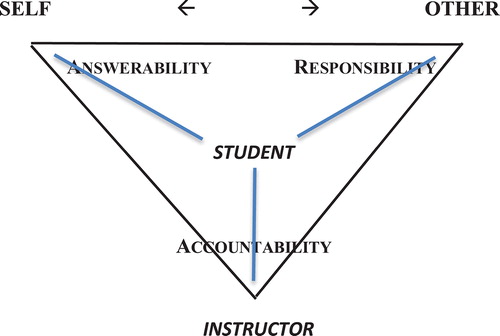

The result, upon putting all the pieces together, is a Tripartite Model of Responsibility, Answerability, Accountability. Please note again that the third notion, Accountability, is not viewed here as part of the interpersonal dynamic itself, but as a practical reality that gives those first two dimensions compellent force. It is the extrinsic rather than intrinsic motivation (and hence not part of Bakhtinian “answerability”) often needed for students to adequately focus on and consider their responsibilities and to adequately exercise answerability for their behaviors, be they meaningful contributions, shortcomings, or failures. In short, Accountability is what gets students to hear the call of the Other (i.e. Responsibility) and motivates them to act (i.e. Answerability). See Figure .

Figure 6. Tripartite model of student group projects. The poles of Responsibility/Answerability/Accountability are overlaid with the three primary elements of Captainships, Self-Assessment, and Non-Compliance Policy

The need for such a decidedly pedagogical model of the ethical dynamics of student collaboration, in contrast to a philosophical taxonomy of different levels of accountability, is perhaps best illustrated by students who improve dramatically during group projects. Based on my own observations, some struggling (or even failing) students radically improve their performance during a group project because they are more driven by their sense of responsibility to other students (whose grades depend on their performance) than by any fear of accountability upon themselves (i.e. bad grades) for their lack of performance. Indeed, I have had numerous students over the last ten years who have habitually failed to complete assignments throughout the semester except during the group project. And with the group project occurring in the middle of the semester, the phenomenon is not explained either by a “slow start” or by finally “getting their act together.” They performed poorly on individual assignments for which they were not responsible to others, then performed significantly better on group assignments for which they were responsible to others, and then returned to poor performance on individual assignments for which they were not responsible to others.

Granted, such a change in behavior could be due to those students not wanting to be held accountable by their peers (as opposed to being held accountable by their instructor), but my impression has consistently been that it is instead more often due to a genuine concern to not have their own poor performance cause harm to other students. This dynamic, in my view, is simply not captured by an adjudicatory model, such as that of Shoemaker (Citation2011). Such models do not examine the difference between (i) a student’s sense of responsibility to other students, (ii) a student’s meta-cognition concerning the moral implications of their own conduct, and (iii) a student’s concern for the formal assessment (i.e. grade) of their own work. Moreover, every imaginable permutation of these three axes is possible, and intentional design of collaborative assignments should seek to pair specific assignment design elements with each axis of the student’s experience of collaborative work: Responsibility, Answerability, Accountability.

This seems like a good point—and hopefully not far too late in this essay—to provide a brief background discussion of my current teaching context, from which this tripartite ethical framework has been influenced. It is hoped that this will not only clarify some of what has gone before in the essay, but also suggest how individual instructors might “balance” the three poles of the tripartite model to suit their own teaching context. For the last several years, I have been predominantly teaching Focused Inquiry, which is the name of a two-semester course sequence (Univ 111 and Univ 112) which constitutes Tier I of Virginia Commonwealth University’s General Education requirements. It is “a learner-centered, interdisciplinary course” that “takes the place of traditional freshman Composition and is required for all incoming first-year students” (Gordon, Henry, & Dempster, Citation2014, p. 104). With a strong emphasis on active learning and student engagement, the Focused Inquiry sequence, since its inception in 2007, “has proven to be instrumental in enhancing the academic success of first-year students and in improving their retention” (Rankin, Citation2009). Most important for the current discussion is the fact that this course is almost entirely comprised of first-year students (with a non-first-year transfer student or student retaking the course here and there). What this means, above all else, is that there is a demonstrable need for a clear, if not robust, mechanism of accountability to ensure that students act responsibly throughout group projects. By contrast, an upper-level seminar or graduate course would likely require far less by way of an accountability-forcing mechanism. Indeed, such extrinsic motivations –e.g. grade penalties, extra-credit, etc.—could conceivably hinder rather than assist the fostering of student responsibility and answerability. [Again, in the tripartite ethical framework, Levinasian responsibility and Baktinian answerability are the two foundational poles of the self-other encounter, so those should prove indispensable in any pedagogical context]. Put bluntly, mature adults may not need, or might even resent, such overt “policing” to guarantee (other-)responsible and (self-)reflective behavior.

A particular teaching context, therefore, can be understood as demanding a sort of pole-balancing or student-positioning within the tripartite framework. Here, one might imagine the student being located in the center of the triangle—see Figure . But the exact shape or “balance” of the triangle may differ depending on the teaching context. In Focused Inquiry, with all first-year students, the model I envision is an equilateral triangle with the student in the very center, demanding equal attention in assignment design to mechanisms of responsibility, answerability, and accountability. [In some cases, when group dysfunction afflicts a group of students, a greater weighting of accountability becomes necessary as the project unfolds—i.e. in the current visualization, the instructor needs to bring the student “closer” to accountability, such as by reminding them of the impact of their behavior on their grade]. By contrast, a visualization of this model for a senior-capstone, for example, might have the student much closer to the self-other side of the triangle, with a longer (i.e. more distant) accountability “arm.” With this degree of adaptability, the tripartite framework offered here is intended to be malleable to the particular needs of a particular course, a particular student cohort, a particular assignment, and so on.

Figure 7. Tripartite model of student group projects. Here—in an alternative rendering of the model—the individual student is placed at the center of the triangle to indicate the three relational “arms” (in blue) and the balancing of those arms to suit a particular teaching context

The metaphorical positioning of the student in the center of the triangle raises an additional question: where does the instructor reside in this model? It would seem that the instructor simultaneously occupies two positions. The first position is at the accountability pole—see Figure —insofar as accountability is imposed by the instructor upon the student as part of the assignment parameters. In other words, the relationship between the student (in the center) and the instructor (at the bottom pole) is that of accountability to the instructor in terms of their grade. This is the student–instructor “arm” (shown in blue) in Figure . Similarly, the relationship between the student and their classmates is indicated by the responsibility “arm” (in blue) and the relationship between the student and themselves is indicated by the answerability “arm” (in blue). This first position is the explicit role of the instructor in the group project, as the person who does the assessment and assigns the grade. The second position, by contrast, is not “seen” by the student and is therefore situated above rather than in the triangle. Here, we need to envision a three-dimensional pyramid (rather than triangle) with the instructor, as the person who designs the group project, at the apex. From this apex of intentional lesson-planning, the instructor designs not only the three poles of the tripartite framework but the aforementioned “balancing” of the three poles as well. The three poles and the balancing of them are manifested in the specific “elements” or parameters of the assignment—as exemplified in Appendices A–C.

Before concluding, I wish to mention three other elements of my major group project assignments that appear to fit quite well within this Tripartite Model of the ethical dimensions of student collaborative work. First, and as mentioned earlier, I have been using a Peer-Assessment tool—refer to Appendix D—which this model suggests does not address the dimension of Answerability as well as a Self-Assessment tool. [Although the two instruments could be combined, it will likely be most effective to maintain them as separate activities in terms of heightened meta-cognition for students (i.e. today we are assessing ourselves and our own answerability for our actions; next class we will assess our teammates in order to hold them accountability for their actions)]. Yet the Peer-Assessment has been a very important part of major group assignments, primarily insofar as students know at the outset, and throughout all stages of the group project, that they will be evaluated by other members of their group. In other words, all students know at the outset that their group members will hold them accountable for what they have or have not done. Here, being held accountable comes from without, in contrast to Bakhtin’s more intrinsic/introspective notion of answerability. To be sure, knowing that peer assessments are coming may urge students to be more cognizant of their responsibilities and to be more self-consciously answerable for their actions throughout. So while Peer-Assessment, like any of the strategies discussed in this essay, can contribute meaningfully at any of the three poles of the Tripartite Model of Student Group Projects, it most clearly fits as an instrument of Accountability—see Figure .

Figure 8. Tripartite model of student group projects. The model adds peer-assessment, rehearsal presentation, and group description classroom activity … and the course grade

Second, for the past several years I have required students to give a Rehearsal Presentation prior to their final group presentation—refer to Appendix E. Instructors quite often require students to submit and revise drafts of major written assignments, but oddly often accept what are essentially first drafts of oral presentations. The impact of the required Rehearsal Presentation has been significant and unmistakable. Most noticeably, and as one would expect, the incorporation of a required Rehearsal Presentation into group assignment design has significantly increased the quality of final presentations. Please note that instructors do not necessarily need to commit additional class time. For example, I typically assign half the groups to present their rehearsal in class (and to then record their final presentation outside of class) and assign the other half to deliver their final presentation in class (after having recorded a rehearsal outside of class). But in addition to improving the quality of group presentations, the required Rehearsal Presentation also functions powerfully in terms of all three dimensions of the Tripartite Model of Ethics—hence its placement in the middle of Figure . In terms of Responsibility, students are reminded at this time of their individual responsibilities (including and in addition to those defined by the Captainships), often as a result of other group members pointing out what they have not yet done (to the group’s satisfaction) or what they could improve before the final presentation. In terms of Answerability, students often need to take ownership at this time for what they have and have not yet done. Individual students are often able to recognize and congratulate themselves for the work they have done to help the group—e.g. being more prepared than other members of the group or having prepared audio/visual aids for the group—or to take stock of themselves in recognizing what they have not yet done and make the decision to “step up their game” for the sake of the group. And in terms of Accountability—in service of both Responsibility and Answerability—it is also a time when group members call each other out, either positively for all the hard work they’ve done or negatively for letting the group down and threatening their grades. Indeed, this element of the major group project assignment has likely been so impactful precisely because it simultaneously supports all three poles of the Tripartite Model.

Finally, a third additional element that I have most recently incorporated into a major group project assignment is a classroom activity designed to compel students to take an honest look at their role within the group (see chapter eight, “Designing group experiences for assessment” in Johnson & Johnson, Citation2004, pp. 171–184). Working with Undergraduate Teaching Assistants, I generate a one-page group description for each group in the class—see Appendix F. [This activity can take considerable time to prepare, and so teaching assistants are a big help, if not essential. For an overview description of such an Undergraduate Teaching Assistant program, see Gordon et al. (Citation2014) and Murray (Citation2015)]. The descriptions are disguised, typically to look like they were downloaded from a website about corporate communication. Each group is then given one of the descriptions (other than their own) to evaluate, unaware that it is in fact a description of one of the other groups in the class. Once they complete their evaluation, both the description and evaluation sheet are given to the group to which they apply. Students then get to see their group, and their individual role within the group, from an outsider’s perspective. Because it is not a formal evaluation, this activity does not directly function as a mechanism of Accountability, though it can remind students that they are being evaluated and will be graded for the work they do. More directly, this activity functions powerfully to simultaneously remind students of their assigned Captainship duties to the group (Responsibility) and compel students to claim greater ownership of and answerability for their contributions to the group (Answerability)—hence its placement at both poles of the Self

Other ethical axis in Figure .

Other ethical axis in Figure .

5. Conclusion

Beginning in an attempt to mitigate the primary objections and most common negative experiences of students with regard to group projects—at least as they have been witnessed by and reported to me—as well as promote active learning and maximize student engagement (see Weimer, Citation2002), this essay has offered a tripartite ethical framework which simultaneously responds to a deficit in pedagogical and philosophical literature and informs the intentional design of student group projects. Regarding the former, this essay has developed a tripartite ethical framework that supplements existing pedagogical literature with a theoretical model of the inner dynamic of student collaboration and group work while also complementing existing philosophical literature with a taxonomy of ethical responsibility in a decidedly educational rather than adjudicatory context. Regarding the latter, built first upon a synthesis of the ethical philosophies of Emmanuel Levinas and Mikhail Bakhtin, and then adding the concept of accountability from existing philosophical literature, this essay has offered a Tripartite Model of Responsibility/Answerability/Accountability. This model offers not an adjudicatory framework for the assessment of moral culpability and blame, but instead a pedagogical framework that illuminates the dynamics through which students develop their abilities to (1) recognize the interpersonal/inter-professional obligations intrinsic to any collaborative endeavor, and (2) take ownership of their own actions, behaviors, and patterns of conduct as they pertain to those obligations, particularly as those two dimensions of moral development are facilitated through intentionally designed mechanisms of accountability. Consistent with the Tripartite Model of Responsibility/Answerability/Accountability and its pedagogical objectives, this essay has suggested that a fully effective collaborative assignment will, in some manner, implement strategies designed to foster those three poles of ethicality: responsibility, answerability, and accountability.

While it is hoped that this essay has contributed meaningfully to the literature on responsibility, answerability, and accountability by addressing a (perceived) deficit in theoretical frameworks sufficient to the pedagogical context of student collaboration and group work, it is equally hoped that this essay’s (resultant) Tripartite Model of Ethics will prove useful as a practical tool for intentional lesson planning and curriculum design. To that end, this essay both clarified and illustrated that tripartite ethical framework with a discussion of three best practices: the assignment of precisely defined individual Captainships, a requirement for students to complete a qualitative Self-Assessment, and the inclusion of a detailed Non-Compliance Policy. Finally, three supplemental best practices—a required Peer-Assessment, a mandatory Rehearsal Presentation, and a meta-cognitive group descriptions classroom activity—were discussed, both in terms of how they fit within the Tripartite Model and how they complement and reinforce the first three strategies. Together, these six intentionally designed elements of an extended group project may help ensure that (1) students will more fully acknowledge and better understand their individual responsibilities within the group, (2) students will confront and reflect upon their individual answerability for the decisions they make and the actions they take, and (3) mechanisms of enforcement are in place to help guarantee that (1) and (2) will happen in a meaningful way.

Funding

The author received no direct funding for this research.

Erratum

This article was originally published with errors. This version has been corrected. Please see Erratum (https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1386349).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeffrey W. Murray

Jeffrey W. Murray, PhD is an associate professor in the Department of Focused Inquiry at Virginia Commonwealth University. He teaches Focused Inquiry, a two-semester seminar for first-year students that emphasizes the development of professional/academic skills and comprises the first tier of the University’s core education curriculum. Murray received a master’s degree in Rhetoric and Communication Studies from the University of Virginia in 1994 and a doctorate in Communication Studies from the University of Iowa in 1998. Throughout his career, he has published numerous articles in the areas of philosophy of rhetoric and communication ethics, and more recently in the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Notes

1. Much of this body of inquiry seems traceable back to the influential work of Blatz (Citation1972), who investigated the distinction between accountability and answerability. Similarly, Smith (Citation2015) credits Watson (Citation1996) as the first to introduce the distinction between “responsibility as attributability” and “responsibility as accountability” (p. 99). Adding to the obvious confusion arising from the myriad pairings among just these three terms (attributability, answerability, accountability) are yet other frameworks, such as that of Dubnick (Citation2003), who distinguishes four forms of accountability: answerability, blameworthiness, liability, and attributability (p. 405).

Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) framework seeks to make meaningful distinctions between the following sorts of questions: “What it means for [some agent] A to be morally responsible for [some action] Φ,” “What it means for A to be blameworthy for Φ,” “What it means for B to blame A” (Shoemaker, Citation2011, p. 604), and so on. Shoemaker (Citation2011) asserts that for Scanlon and Smith, “being responsible for Φ is most importantly a matter of being answerable to others for Φ, where the conditions of answerability are just the conditions for attributability. In other words, what makes Φ properly attributable to me is just what makes me answerable for Φ. Answerability is coextensive with attributability” (p. 603). Shoemaker (Citation2011), by contrast, argues that this view “conflates attributability and answerability, which are actually distinct conceptions of responsibility” and that “one may well be attributability-responsible for Φ without being answerability-responsible for it” (p. 603).

2. Furthermore,

Bakhtin’s insight is not only that language is dialogically laden with the traces of the words of Others, but moreover that we are dialogically laden with the traces of Others. We are dialogical. Bakhtin claims that “[c]onsciousness is in essence multiple” (Citation1984, p. 288): “I am conscious of myself and become myself only while revealing myself for another, through another, and with the help of another. The most important acts constituting self-consciousness are determined by a relationship toward another consciousness (toward a thou) … The very being of man … is the deepest communion. To be means to communicate” (1984, p. 287). (Murray, Citation2000, p. 137).

3. At this point it should be noted (again) that Bakhtin’s notion of “answerability” is entirely distinct from the notion of answerability appearing in the body of philosophical literature represented by Blatz (Citation1972), Shoemaker (Citation2011, Citation2015), and Smith (Citation2015), or in other (competing) philosophical vocabularies—Dubnick (Citation2003), for example. Moreover, the interpretation of Bakhtin’s notion of answerability offered by Murray (Citation2000) and reaffirmed in this current essay is, of course, not the only viable reading of Bakhtin. Ewald (Citation1993), for example, offered a reading of Bakhtin’s notion of answerability qua “response” that places it very close to this essay’s synthesis of Levinasian responsibility and Bakhtinian answerabililty. According to Ewald (Citation1993), “the notion of answerability carries with it a pun. To answer is not only to be (ethically) responsible, but also to respond” (p. 340). And “this ‘double-voicedness’ of answerability” (p. 340) means that “individual accountability is ‘answerability-as-responsibility’” (p. 341). Arguing from the disciplinary perspective of composition studies, Ewald (Citation1993) asserts that “Another way to interpret answerability is as an answer or response. Answerability-as-response is intimately linked in Bakhtin to the act of authorship. Answering is authoring. Authoring is responding. For Bakhtin, the word, and the writing of the word, is a two-sided act, where meaning is created by both writer and reader (See Figure )” (p. 341).

4. This synthesis has numerous implications, including the following: Bakhtin is pointing out that ethical philosophy has overlooked the existential freedom of the subject by taking as unproblematic the translation of an abstract ethical principle into a concrete obligation to act. Instead, Bakhtin foregrounds the freedom of the subject to make the decision to act or not to act in a particular situation. According to Bakhtin, “the answerable act is, after all, the actualization of a decision” (Citation1993, p. 28), the freedom to obligate oneself through the answerable act. Of course, Levinas acknowledges this fact when he admits that “Murder, it is true, is a banal fact: one can kill the Other; the ethical exigency is not an ontological necessity. The prohibition against killing does not render murder impossible” (Citation1985, p. 87). The shortcoming in Levinas’s conception of ethics is that he cannot provide an adequate account of how and why murder is possible. Levinas recognizes the fact of murder, but it is Bakhtin’s existentialist conception of answerability which provides an explanation of the how and why of murder. (Murray, Citation2000, p. 144).

5. Finally, please note that:

In one sense, there is no “self” or “Other” as a wholly distinct and autonomous entity. In another sense, within the dialogical interrelatedness of self and Other, the self and the Other remain distinguishable as separate poles within the architectonic. Therefore, self and Other are discussed here as points of emphasis within a larger dialogism and not as entirely distinct or separable entities. (Murray, Citation2000, p. 137).

In other words, “Self and Other exist only within an overarching dialogical superstructure, or architectonic, the ‘fundamental moments’ of which are ‘I, the other, and I-for-the-other’ (Bakhtin, Citation1993, p. 54)” (Murray, Citation2000, p. 137)

6. Such distinctions, though, surely arise when we, as teachers, evaluate our students’ performance. We might find, for example, that a student who missed a week of classes due a death in the family is answerable rather than accountable for a particular failing in a group project, or that a student for whom English is a second language might be merely attributable for a particular oversight on an assignment rather than answerable for it. Indeed, this is one of Shoemaker’s (Citation2011) main goals, as well as a point of contention for other writers (see Smith, Citation2015, for example): that any “truly comprehensive theory” that purports to account for our actual “moral practices” and to be capable of handling difficult cases (such as the mentally incapacitated or the psychopath) “must incorporate … three distinct conceptions of responsibility—attributability, answerability, and accountability” (p. 602).

References

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Toward a reworking of the Dostoevsky book. In M. M. Bakhtin (Ed.), Problems of Dostoevsky's poetics (C. Emerson, Ed. & Trans., pp. 283–302). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1993). Toward a philosophy of the act ( V. Liapunov & M. Holquist , (Eds.), ( V. Liapunov , Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Blatz, C. V. (1972). Accountability and answerability. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour , 2 , 101–120.10.1111/jtsb.1972.2.issue-2

- Costa, A. L. , & Kallick, B. (2014). Dispositions: Reframing teaching and learning . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- DeBoer, T. (1986). An ethical transcendental philosophy ( A. Platinga , Trans.). In R. A. Cohen (Ed.), Face to face with Levinas (pp. 83–116). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Dubnick, M. J. (2003). Accountability and ethics: Reconsidering the relationships. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior , 6 , 405–441.

- Ewald, H. R. (1993). Waiting for answerability: Bakhtin and composition studies. College Composition and Communication , 44 , 331–348.10.2307/358987

- Gordon, J. , Henry, P. , & Dempster, M. (2014). Undergraduate teaching assistants: A learner-centered model for enhancing student engagement in the first-year experience. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 25 , 103–109.

- Handelman, S. (1989). Parodic play and prophetic reason: Two interpretations of interpretation. In P. Hernadi (Ed.), The rhetoric of interpretation and the interpretation of rhetoric (pp. 143–171). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Johnson, D. W. , & Johnson, R. T. (2004). Assessing students in groups: Promoting group responsibility and individual accountability . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Levinas, E. (1985). Ethics and infinity (R. A. Cohen, Trans.). Pittsburgh, PA: Dusquesne University Press.

- Levinas, E. (1989a). Ethics as first philosophy ( S. Hand & M. Temple , Trans.). In E. Levinas & S. Hand (Eds.), The Levinas reader (pp. 75–87). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Levinas, E. (1989b). Ideology and idealism ( S. Ames & A. Lesley , Trans.). In E. Levinas & S. Hand (Eds.), The Levinas reader (pp. 235–248). Oxford: Blackwell.

- McQuail, D. (1997). Accountability of Media to Society. European Journal of Communication , 12 , 511–529.

- Murray, J. W. (2000). Bakhtinian answerability and Levinasian responsibility: Forging a fuller dialogical communicative ethics. Southern Communication Journal , 65 , 133–150.10.1080/10417940009373163

- Murray, J. W. (2015). Articulating learning outcomes for an undergraduate teaching assistant program: Merging teaching practicum, leadership seminar, and service-learning. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 15 , 63–77.10.14434/josotl.v15i6.19099

- Murray, J. W. (2016). Skills development, habits of mind, and the spiral curriculum: A dialectical approach to undergraduate general education curriculum mapping. Cogent Education , 3 , 1156807.

- Painter, C. , & Hodges, L. (2010). Mocking the news: How the daily show with Jon Stewart holds traditional broadcast news accountable. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 25 , 257–274.10.1080/08900523.2010.512824

- Rankin, D. L. (2009). Curriculum approval request form ( Unpublished internal document). Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

- Scanlon, T. M. (1998). What we owe to each other . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Scanlon, T. M. (2008). Moral dimensions: Permissibility, meaning, blame . Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674043145

- Shoemaker, D. (2011). Attributability, answerability, and accountability: Toward a wider theory of moral responsibility. Ethics , 121 , 602–632.10.1086/659003

- Shoemaker, D. (2015). Responsibility from the margins . Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198715672.001.0001

- Smith, A. M. (2005). Responsibility for attitudes: Activity and passivity in mental life. Ethics , 115 , 236–271.10.1086/426957

- Smith, A. M. (2007). On being responsible and holding responsible. The Journal of Ethics , 11 , 465–484.10.1007/s10892-005-7989-5

- Smith, A. M. (2015). Responsibility an answerability. Inquiry , 58 , 99–126.10.1080/0020174X.2015.986851

- Watson, G. (1996). Two faces of responsibility. Philosophical Topics , 24 , 227–248.10.5840/philtopics199624222

- Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Appendix A Captainships (Responsibility)

Research Project Leadership Roles—Print and sign your name below:

Proposal Captain and Team Manager: _____________________________________________

The Proposal Captain/Team Manager is responsible for: (a) facilitating the two Proposal Workshops (today and Wednesday), (b) distributing copies of Proposal #1 and Proposal #2, before or at the next class meeting, to each member of the group and to the course instructor—please bring one copy of #1 for me on Wed. and two copies of #2 for me on Fri., and (c) thereafter ensuring the group’s regular progress by coordinating meetings, sending reminders, etc., and by assisting the other Captains when appropriate. All individual work should be submitted through the Team Manager!

Arrangement Captain: _____________________________________________

The Arrangement Captain is responsible for: (a) facilitating the Arrangement Workshop (see Overview for date),and ensuring that all necessary arrangement devices are composed for the Group Presentation, (b) typing up the completed arrangement worksheet and providing copies to the Written Report Captain and course instructor on or before the Rehearsal Presentation, and (c) coordinating with the Presentation Captain about inclusion of the Arrangement Devices into the Group Presentation, including deciding who will deliver those parts of the Group Presentation.

Presentation Captain: _____________________________________________

The Presentation Captain is responsible for: (a) ensuring that all members of the group clearly understand the parameters and expectations of the Group Presentation assignment, (b) scheduling—perhaps in Cabell Library’s Presentation Rehearsal Studio—and administering the out-of-class presentation (either the rehearsal presentation or the final presentation, as scheduled), (c) facilitating an evaluation of the rehearsal by members of the group and preparing a brief (½–1 page) report of the rehearsal, and (d) orchestrating the successful delivery of the final presentation, including responsibility for any group audio/visual aids or equipment.

Research Poster Captain: _____________________________________________

The Poster Captain is responsible for: (a) ensuring that all members of the group submit their half-page research abstracts for inclusion on the Research Poster, (b) soliciting from group members or otherwise procuring all necessary audio/visual aids for completion of the Research Poster, (c) physically constructing the Research Poster, and (d) ensuring that the Research Poster includes a Title, Introduction, and Conclusion, in addition to the individual research abstracts and supplementary audio/visual aids.

Written Report Captain: _____________________________________________

The Written Report Captain is responsible for overseeing the compilation of the individual written components of the research project into the Final Written Group Report, including insertion of arrangement devices, and proper and consistent formatting of the Report.

Bibliography Captain: _____________________________________________

The Bibliography Captain is responsible for overseeing the compilation of the individual annotated bibliographies, including collating and alphabetizing all entries, into the collective Bibliography and for checking for the proper and consistent formatting of those entries throughout the collective Bibliography.

*The Written Report and Bibliography Captains should also conduct a final proof-reading (and/or oversee a final group proofreading session), including double-checking all intra-textual and bibliography citations. This does NOT release other group members of their responsibility for properly documenting their own sources and carefully proofreading their own component. Rather, the role of the Written Report and Bibliography Captains is to check for and remedy any remaining errors with this added level of review.

Appendix B Self-Assessment (Answerability)

Having completed the Unit II Group Presentation, Academic Research Poster, and Written Research Report, you must now critically evaluate your contribution to the group project.

For this Self-Assessment assignment, you are asked to critically reflect upon your contributions to the Unit II Group Project. In doing so, please consider both the quantity and the quality of your work and your participation throughout the unit. This includes both the specific duties of your assigned Captainship as well as your General Contribution (to the proposal workshops, arrangement workshop, rehearsal presentation, final presentation, academic research poster, final written research report, and any other scheduled group meetings).

Moreover, please consider all aspects of your work and participation, as they may have contributed not only to the final outcome / grade of the group, but also to the mental health and comfort level of your teammates. For example, consider the consistency of your work, your ability to meet deadlines set by the group, your punctuality to team meetings, your communication, and so on. And consider how your efforts (or lack thereof) contributed not only to the tasks and performance of the group, but also to the social cohesion and enjoyment of the group. What was your attitude like? Did you contribute to a positive atmosphere for the group? Did you drive people insane?

OK, now here are the hard parts. First, do NOT assign yourself a grade or in any other way quantify your performance. Second, do NOT compare yourself to other members of the group. Got that?

No numbers! Evaluate the inherent quality of your membership in the group. And no comparisons! What other people did or did not do is not an alibi for your effort or an excuse for your commitment. You evaluate you!

Got that? This Self-Assessment is intended to be your honest appraisal of your performance, regardless of the performance of the group as a whole or of other members of the group. What kind of team member were you? What did you do? What did you fail to do? What more could you have done? Did you do your best? Are you proud of your effort? Are your pleased with your attitude? Did you surprise yourself? What did you learn about yourself? Who are you?

Appendix C Non-Compliance Policy (Accountability)

Non-Compliance Policy

Any Group Work that is incomplete (i.e. missing the contribution of one or more individual group member) will incur a one letter-grade penalty (per missing contribution). This policy pertains to the Final Group Presentation, Group Academic Research Poster, and Final Group Written Research Report.

This penalty is not intended to penalize students who complete their work on time but to help ensure accountability from all group members. This penalty to the group can be avoided if and only if the non-compliant student, Team Manager, and Course Instructor are all notified in writing of the student’s non-compliance with an individual submission deadline at least 48 h before the final due date—e.g. before 9:00am on Wednesday if the assignment is due at 9:00am on Friday. The student should be reminded at that time that they must submit their work to the appropriate Captain no less than 24 h in advance of the due date. If that group member continues to be non-compliant, the group will not be held accountable. In that case, the student, Team Manager, and Course Instructor should all be notified once again in writing at 24 h in advance of the due date, and the group should proceed without that group member’s contribution. This protocol also applies if a Captain is not fulfilling their duties!

So basically: 48 h = “Hey Dunderhead (cc: Instructor), I don’t have your stuff yet. I need it by this time tomorrow.” 24 h = “Hey Instructor (cc: Dunderhead), I still don’t have their stuff.” [At your discretion, you may give that member more time to comply—if you don’t mind staying up all night to complete the assignment—but there must be initial communication 48 h in advance and secondary communication 24 h in advance of the due date in order to avoid the incomplete penalty.]

Please note that this protocol may need to be enacted if a particular group member’s work is grossly unsatisfactory, as opposed to missing entirely. If such a case arises, initiate the Non-Compliance Policy—only “You need to fix your stuff” instead of “I don’t have your stuff yet”—and attach that member’s work to the email to the Instructor so they can assess the degree of non-compliance. [In the case of the Written Report, any group member who received less than a 70 on the integrated research component is susceptible to exclusion from the Report.]

Note: Any non-compliant group member will receive a grade of zero on the assignment and will need to make arrangements with the Instructor to complete the assignment in whole or in part for partial credit.

As usual, late group work will be penalized one letter grade, so don’t wait for a member of your group to turn in their work if it will put the group in jeopardy of incurring both an incomplete work penalty and a late work penalty. It wouldn’t be too bad to trade the incomplete penalty for a late penalty, but if that group member never gets their part done, your group would incur both penalties. Ouch!