Abstract

There might always be errors during the learning process which need correction; accordingly, providing corrective feedback is critical. However, the various types of feedback applied during classes affect the learning and teaching process. Teaching and learning could be applied within EFL classes by providing learners with recasts. Recasts have been provided frequently in both first language acquisition and second language acquisition. Extensive studies have indicated that recasts are the most frequent feedback type in speaking, yet this study investigates their efficacy on writing. Forty high school EFL learners participated in this study for 20 sessions within a period of 3 months. The participants were divided into two experimental groups and were provided with two types of feedback. While participants of one group received recasts as a type of indirect feedback, participants of other group received direct corrective feedback. Results obtained by a pretest and a posttest indicated that both groups made significant progress in their writing performance, yet there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups on the posttest. The recast group achieved higher scores, performing better than the direct correction group.

Public Interest Statement

It is almost impossible to imagine a language learning process without any mistakes and errors. What we all know is that the various types of feedback applied during classes affect the learning and teaching process. This urges us to know more about the most effective types of error correction. Forty high school learners in a non-English speaking context participated in this study for 20 sessions within a period of 3 months. While participants of one group received recasts as a type of indirect feedback, participants of other group received direct corrective feedback. Results of the test before the course and the final test at the end of the course indicated that both groups made significant progress in their writing performance, yet the recast group achieved higher scores, performing better than the direct correction group.

1. Introduction

Writing has been claimed to be the most challenging task for second language learners by scholars (e.g. Banaruee, Citation2016; Richards & Renandya, Citation2002). Skills involved in writing are highly complex (Richards & Renandya, Citation2002). This complexity becomes still more noticeable when the learners’ proficiency is not high (Banaruee, Citation2016). An important point in writing concerns errors and whether they should be corrected or tolerated. Accordingly, Banaruee and Askari (Citation2016) stated that it is not evident which feedback strategy is more effective; they believe the findings are not conclusive. Teachers may take advantage of different kinds of correction techniques, such as recasts. Even though scholars such as Ellis (Citation2003) and Sheen (Citation2006) assert that recast is the most common type of correction, the effectiveness of recast has not been investigated in writing performance. The present study sought to find out the effectiveness of recasts on high school EFL learners’ writing performance. The major focus of studies that have investigated the effectiveness of different types of corrective feedback has been the extent to which direct or indirect corrective feedback facilitates improved accuracy.

With a focus on speaking, recast has been defined variously in the context of English language teaching, Bohannon, Padgett, Nelson, and Mark (Citation1996) defined recast as a correction technique through expansion, transposition, deletion, and other changes, yet with the maintenance of the meaning. Some studies added additional elements to the definition of recasts, such as length (Lyster & Ranta, Citation1997), stressed intonation (Doughty & Varela, Citation1998), and number of reformulations (Philp, Citation2003). Similarly, recast was expounded as rephrasing an utterance with a change of components and unchanged meaning of the whole. Additionally, recasts may vary in form, size, length, and function. In this respect, Ellis and Sheen (Citation2006) argued that recasts can be of various types including corrective or non-corrective, full or partial, single or multiple, and simple or complex recasts. The effect of teaching is demonstrated in learning, in this respect, taking the process approach into account to evaluate learners’ writings was also considered throughout this study. Hamp-Lyons and Condon (Citation2000) asserted that drafting, peer and teacher correction, and revision are highly important in developing writing skills. The idea was based on Flower and Hayes’s (Citation1981) model of process writing. This was reaffirmed by Ruegg (Citation2015a) “of particular importance within the process approach to writing instruction are drafting, feedback, and the use of that feedback in revision.” (p. 262). The practice of recast in writing has not received significant attention by scholars. Therefore, this study was conducted to fill this research gap by providing high school learners with this type of corrective feedback and comparing its efficacy with direct corrective feedback. This study aimed to answer the following research questions:

| (1) | Do recast and direct corrective feedback have any significant impact on the writing performance of high school EFL learners? | ||||

| (2) | If the answer to above question is affirmative, which one is more effective in improving writing performance of learners? | ||||

In order to answer research questions, the following hypotheses were suggested by researchers of this study:

Hypothesis1: Recast and direct corrective feedback have a significant positive impact on the writing performance of high school EFL learners.

Hypothesis2: Recast is more effective than direct corrective feedback in improving writing performance of high school EFL learners.

2. Review of the related literature

2.1. Theoretical views of feedback

A historical overview of correction on writing tasks in EFL courses suggests a change in the underlying guidelines throughout the past thirty years. From 1970s to1980s, countless research was done on writing in L2 classrooms. In the 1970s, the dominant methodology was rooted in the behaviorism theory of learning (Brown, Citation2007). This theory asserted the role of immediate correction and insisted on the role of teachers as error-preventers. On the contrary, in the next decade, not much attention was paid to error correction and the required teaching and learning pedagogy in this respect (Ferris, Citation2003). As Lee (Citation1997, Citation2004) indicated, teachers may clarify whether: to correct or not to correct errors, to identify or not identify error types, or to locate errors directly or indirectly. Some scholars (e.g. Banaruee & Askari, Citation2016; Ruegg, Citation2010, Citation2017, Citation2018) suggested that providing feedback, direct or indirect, from teachers or peers, and on every language component can have a significant effect. Research on error correction today investigates beyond the ideas of to correct or not to correct errors. Scholars seek solutions for finding specific methods of correction for every different type of error in different types of tasks. Moreover, learners’ age, gender, learning styles, and cultural backgrounds have been under investigation recently.

2.2. Empirical studies

2.2.1. Studies against corrective feedback

Pienemann’s (Citation1998) processability theory stated that no change or learning would occur if it is beyond the learners’ level of interlanguage. Semke (Citation1984) studied the effects of various methods of responding on L2 learners’ writing and the findings revealed that correction neither developed the learners’ writing skill nor their language performance in general. Truscott (Citation1996, Citation1999) persistently believed that error correction, regarding grammatical errors, is not beneficial. He went as far as to contend that it is detrimental to learners’ progress in writing. Truscott (Citation2004, Citation2007) reaffirmed that even though numerous studies have claimed that error feedback could improve writing performance; error correction has been a big failure. Additionally, he suggested that the fewer errors made by the students could be due to learners avoiding correction by writing less or not writing certain constructions. Xu (Citation2009) argued that studies concerning the efficacy of corrective feedback need to consider the treatability of linguistic features, but not their teachability, while contemporary research has focused on the linguistic features that are teachable. She also added that observing learners’ learned systems of specific linguistic features encourages them to be monitor those features consciously, and this is what researchers have considered as evidence for the efficacy of error correction which it is not. Fazio (Citation2001) investigated the effect of differential feedback on the journal writing accuracy. She argued that the correction was not effective to increase the learners’ accuracy. She also added that without considering the learning context, learners’ attentiveness, and their familiarity with the correction procedure, deciding on the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of error correction is a pointless effort. Knoblauch and Brannon (Citation1984) suggested that learners who receive peer correction or use self editing develop better writing skills than those who receive teacher feedback. They contended that teacher error correction inhibits learners’ cognitive skill development. Hendrikson (Citation1980) contended that direct error correction does not involve much cognitive processing and learners need to engage in self-editing. Other studies (Cohen & Cavalcanti, Citation1990; Ferris, Citation1995; Hyland & Hyland, Citation2001; Zacharias, Citation2007) have claimed that learners do not understand the feedback they receive. Krashen (Citation1985) suggested postponing error corrections to the last stage of language learning. This was based on the input hypothesis. Learners speak as a result of the competence built through comprehensible input and not the cause of acquisition. Moreover, he asserted that the comprehensible input was necessary, yet not sufficient. Learners’ affective factor needs to have little impact on their learning, which means the learners must be motivated, confident, and free of anxiety and stress.

2.2.2. Studies supporting corrective feedback

A significant body of research has investigated the efficiency and nature of corrective feedback (CF), as well as the roles of CF. This research substantially supports the usefulness and feasiblity of CF. There are a large number of studies (e.g. Bitchener & Knoch, Citation2008; Chandler, Citation2003; Ferris, Citation1995, Citation2003; Ferris & Roberts, Citation2001; Khoshsima & Banaruee, Citation2017; Lalande, Citation1982; Ruegg, Citation2010, Citation2017) which have illustrated that corrective feedback can successfully reduce some types of errors present in writing. In a typology of corrective feedback types, Banaruee and Askari (Citation2016) indicated that all types of corrective feedback can be effective and could be employed simultaneously. Some studies (e.g. Kepner, Citation1991; Ruegg, Citation2015b; Semke, Citation1984; Sheppard, Citation1992) have argued for the efficacy of content-focused corrections. In the study done by Maleki and Eslami (Citation2013), it was found that indirect feedback enabled learners to make fewer morphological errors in a new piece of writing than direct correction did. This confirms the findings of Chandler (Citation2003) who pinpointed corrective feedback as a way of improving the accuracy of L2 students’ writing. Interestingly, it was found by Banaruee, Khoshsima, and Askari (Citation2017) that individuals with different personality types demand different levels of explicitness of corrective feedback. They suggest that in order to provide effective feedback on extrovert learners’ writings, a mixture of explicit and implicit feedback is the most effective.

2.2.3. Studies against recasts

Criticism has been leveled against recasts as a feedback method. The main limitations of recasts are related to whether or not they are noticeable and their ambiguous nature. Sommers (Citation1982) argued that learners as writers desire and demand thoughtful comments; in this respect, appropriating learners’ writings is not effective. Learners need comments which allow them to develop control over their writing and to get their intended meaning communicated.

Lyster and Ranta (Citation1997) argued that, even though over half of the teachers in their study used recasts in their classes, the level of uptake resulted from recast was found insignificant. Lyster (Citation1998) discussed the unnoticability and implicitness of recast as a drawback of this feedback type. Accordingly, Panova and Lyster (Citation2002) believed that recasts usually pass by the learners unnoticed and hence are not facilitative for interlanguage development. Lyster and Mori (Citation2006) in line with Panova and Lyster (Citation2002) found that the teachers preferred to use recasts. However, the rate of learners’ uptake following these recasts was very low. Another issue raised against recasts is that due to their ambiguous nature they might be perceived as synonymous in function to mere repetition for language learners (Long, Citation2006). Another limitation of recasts is related to their repairing function; recasts do not elicit repair and learners are simply provided with the correct form without being pushed to modify their output (Loewen & Philp, Citation2006). Furthermore, based on previous research (Ellis & Sheen, Citation2006), Loewen and Philp (Citation2006) believed that recasts may be differentially effective depending on the targeted form under study. Recast is mainly limited in use in classes due to its ambiguous corrective force and the overt corrective nature of explicit negative feedback. In this respect, several scholars have claimed the ineffectiveness of recast in comparison with prompts (e.g. Ammar & Spada, Citation2006; Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor, & Mackey, Citation2006; Lyster, Citation2004; Lyster & Izquierdo, Citation2009) as the result of implicitness, vagueness, and being passed unnoticed by learners. Additionally, Egi (Citation2007) suggested that recasts in their long form are considered different from the problematic utterances, and learners tended to misinterpret them as responses to content. All of the studies discussed focused on recasts as spoken corrective feedback and considered it as negative implicit feedback.

Therefore, it may be effective to follow implicit corrective recasts with explicit corrective feedback or to change the degree of implicitness toward explicitness on recasts as written corrective feedback. No study has investigated the relative effectiveness of recasts accompanied with explicit feedback in the realm of writing. This study makes an effort to do so. The following section reviews a number of studies that have supported the effectiveness of recasts on the speaking of EFL learners (the literature lacks studies done on the efficacy of recasts on writing performance of EFL learners).

2.2.4. Studies supporting recasts

A significant body of research supports the efficacy of recast in classrooms which focused on speaking (e.g. Banaruee, Citation2016; Braidi, Citation2002; Han, Citation2002; Lyster & Ranta, Citation1997; Mackey & Oliver, Citation2002; Mackey & Philp, Citation1998; Nassaji, Citation2009; Zabihi, Citation2013). In terms of the consistency of tense acquisition, Han (Citation2002) compared one group that received no feedback and one that received (oral or written) recasts and claimed that in written and oral examinations the recast group outperformed the no feedback group due to enhanced awareness. A study performed by Zabihi (Citation2013) also supported the notion that recasts, as a form of error correction, could contribute to learners’ writing improvement. Nassaji (Citation2009) investigated two types of interactional feedback: recasts and elicitations. He investigated recasts and elicitations’ subsequent effects in grammatical features popping up in incidental dyadic interactions. Recast was practiced as an indirect indicator of incorrect statements as the teacher expressed the reformulated sentence implicitly, while elicitation was practiced in various forms as the teacher initiated corrected statements and waited for the learners to complete them, asked them questions to explain “hows”, “whys”, and “whats”, and asked them directly to reformulate their incorrect statements. The results of his study revealed that recasts were more effective than elicitations in the short-term. Previous research supported the notion that students tend to receive feedback on the errors they make, and believe in its usefulness in improving their writing skill (e.g. Hedgcock & Lefkowitz, Citation1994; Lee, Citation2008; Leki, Citation1991; Ruegg, Citation2010). In an investigation of the effectiveness of written recasts, Ayoun (Citation2001) investigated the efficacy of written recasts in comparison with modeling as positive evidence and grammar instruction which was explicit and negative feedback. She concluded that learners who received recasts outperformed those who received explicit grammar instruction. Given the conflicting results on the effects of different feedback types, it can hardly be concluded that one feedback strategy would work for all grammatical errors in student writing. It is thus important to investigate various error categories that are targeted. The present study followed this line of research by examining recasts in foreign language writing.

3. Methodology

3.1. Design

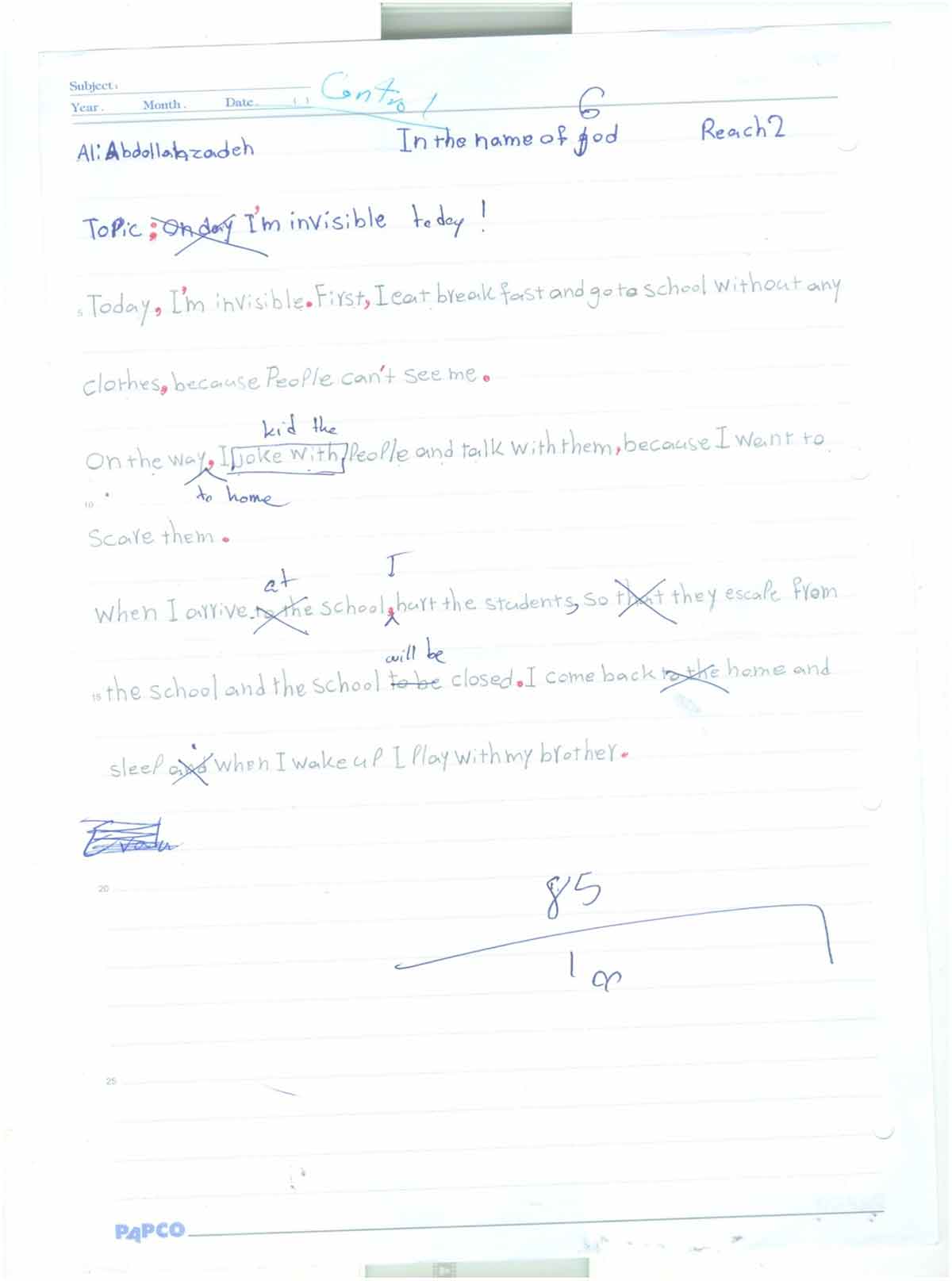

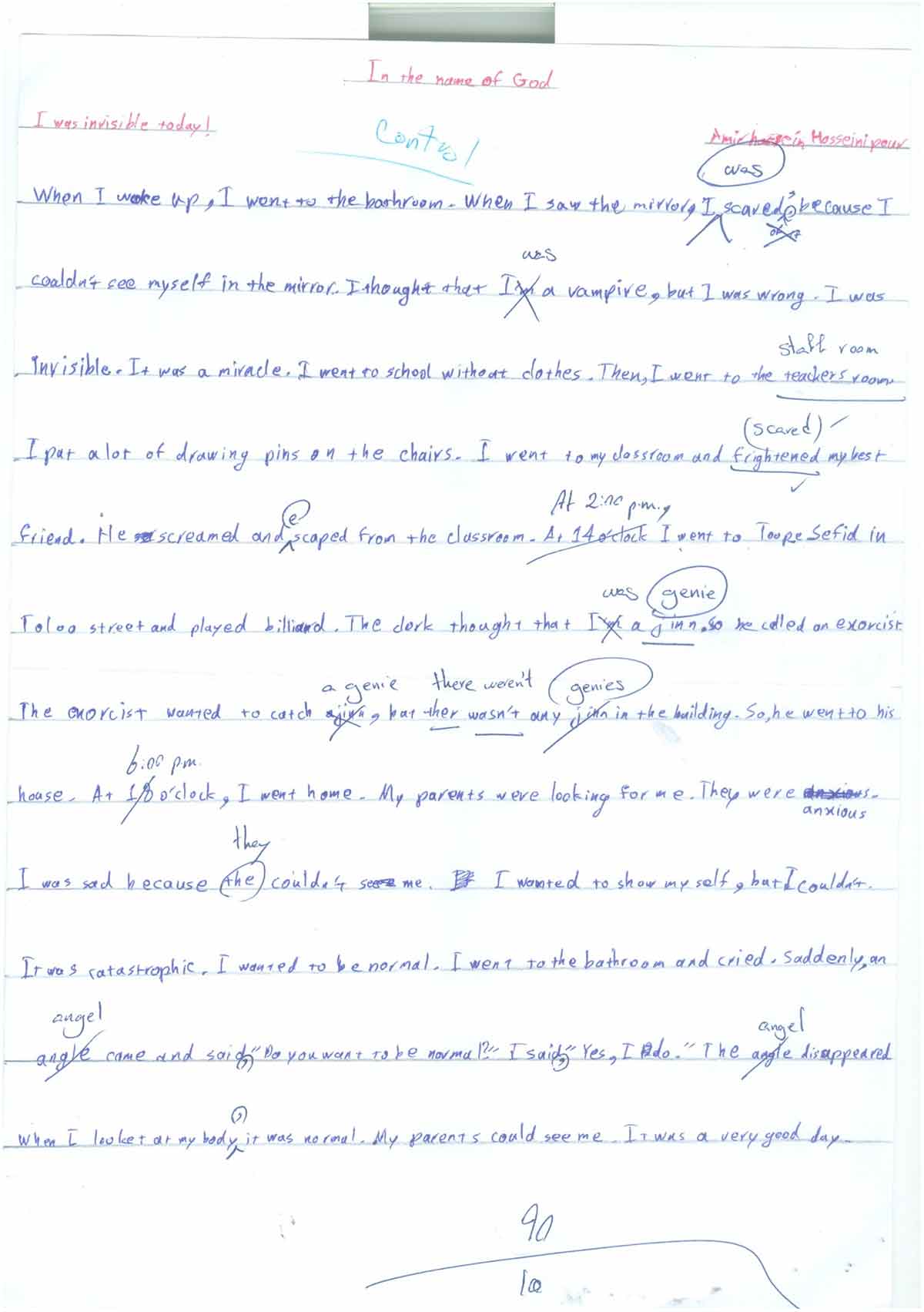

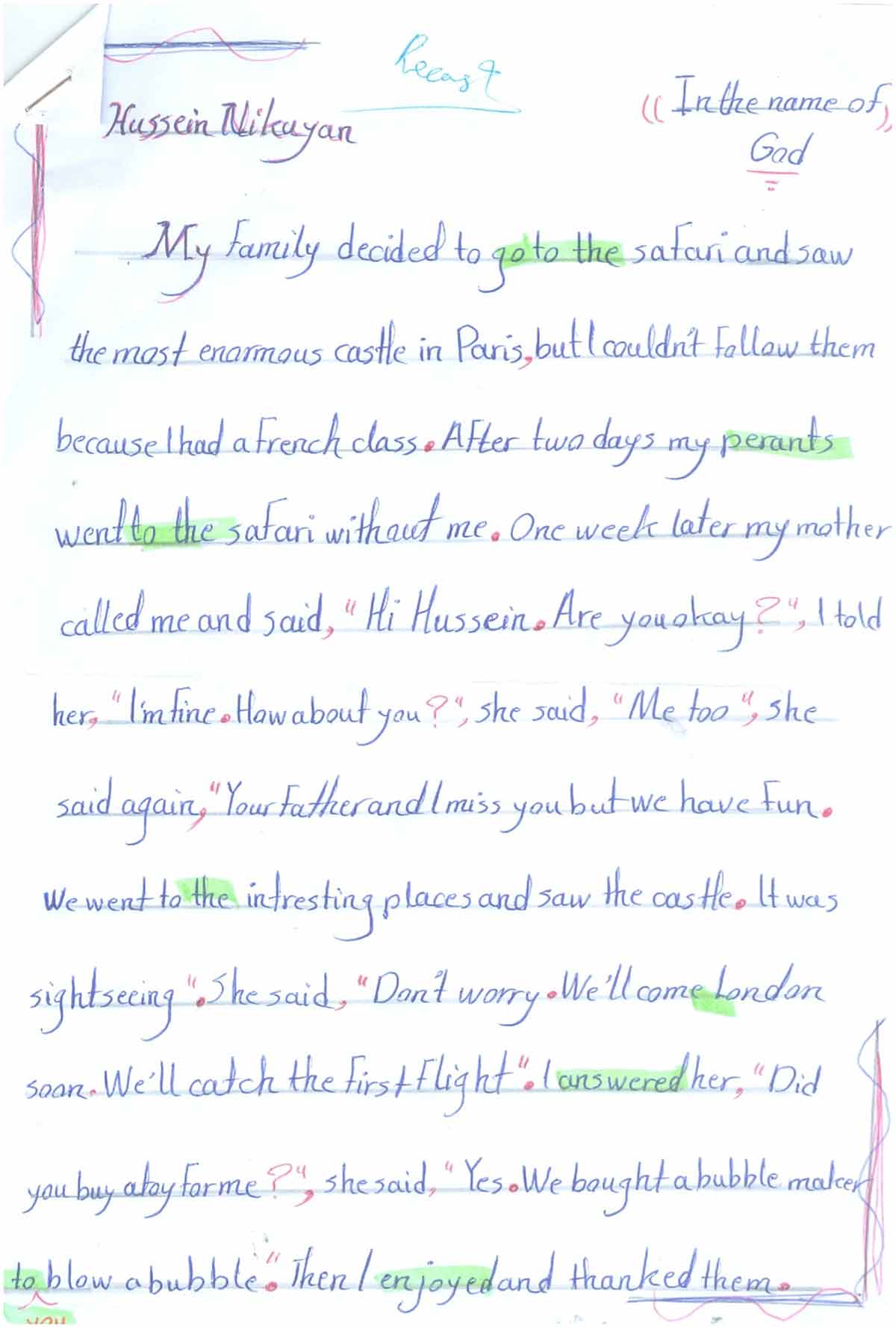

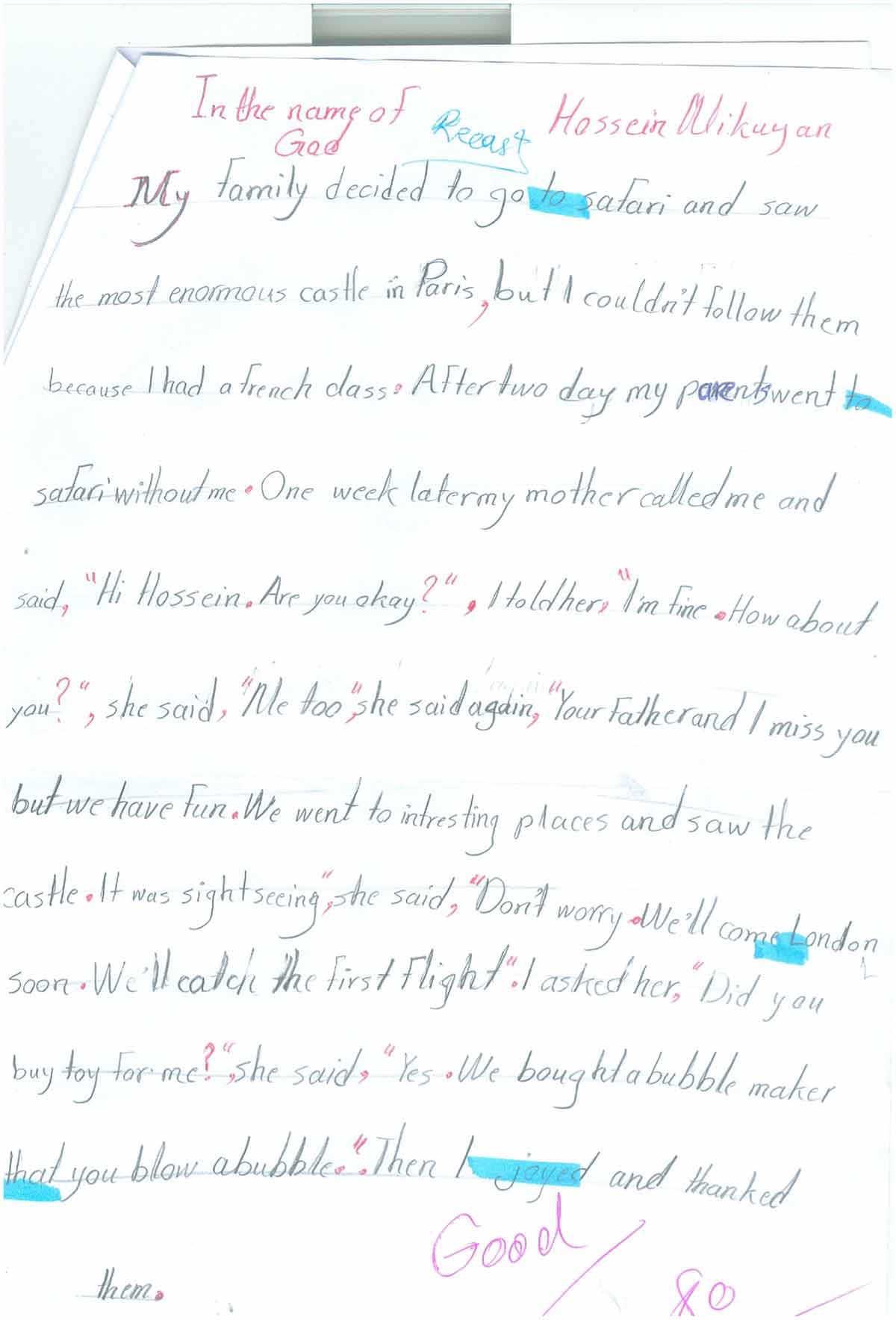

This study employed a quantitative, quasi-experimental research design with a pretest–treatment–posttest structure. Two groups were assigned on the basis of intact classes. Each class consisted of 20 students in Reach level, equal to A2 (Waystage Level) based on the Common European Framework. Both groups were given a written pretest before the program to approve the homogeneity of the two groups under study. The pretest was a Mock IELTs Writing Task 2 provided to the learners and the resulting texts were rated by their teacher and two other teachers. Following this, a treatment was given to each group. The writing and scoring criteria were explained to the learners in the initial sessions. The posttest was a Mock IELTs Writing Task 2 provided to the learners and the resulting texts were rated by their teacher and two other teachers. The focus of this research was to provide an increased understanding of how utilizing feedback can be beneficial in EFL writing classes at high school. Finally, all the collected data were analyzed. Details on all these aspects will be discussed in the following sections.

3.2. Participants

The participants of this study were 40 high school male EFL learners, chosen according to convenience sampling from Reach level (A2) classes. They were placed randomly into two intact groups; each group consisted of 20 learners aged between 14 and 16 years old. All 40 participants were in level A2, and their homogeneity was corroborated by the pretest results.

3.3. Instrumentation

Instruments employed for the purpose of this study included a pretest, writing task 2 of IELTS, so as to assure the level of the students before they received treatments. Writings assigned as homework tasks received recasts as feedback in two phases and were scored in accordance with IELTs grading norm (see Appendix 1) based on the level of vocabulary, grammar, coherence, and relevance. The learners received feedback, revised, and then received the second feedback and assessment. Inter-rater reliability was tested to ensure reliability and consistency of scoring procedures. For the posttest, another writing task 2 of IELTs was given to find out whether the learners had improved their writing performance while receiving the treatments or not. Students’ writings were rated by three different raters.

3.4. Data collection procedure

3.4.1. Recasts group procedure

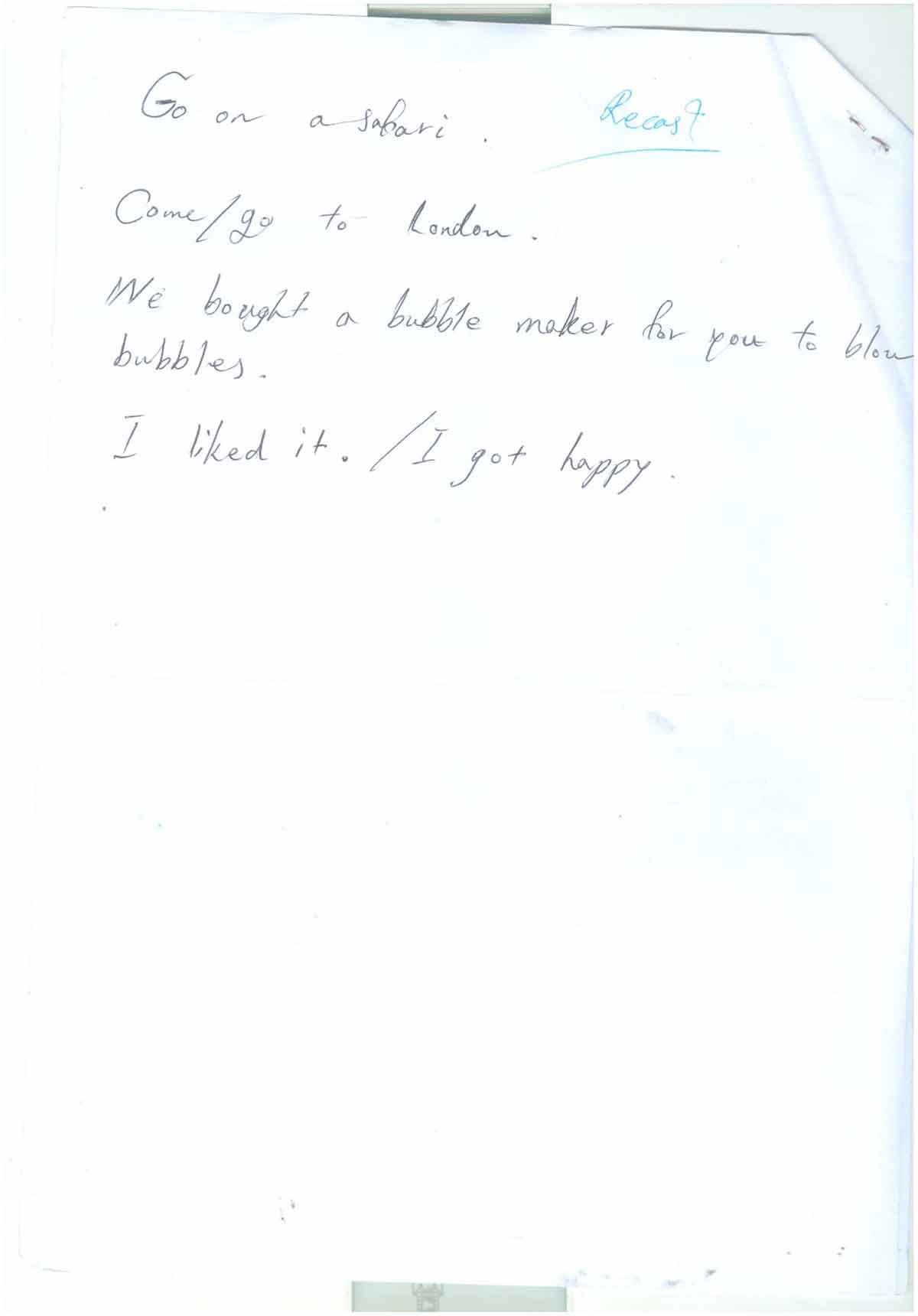

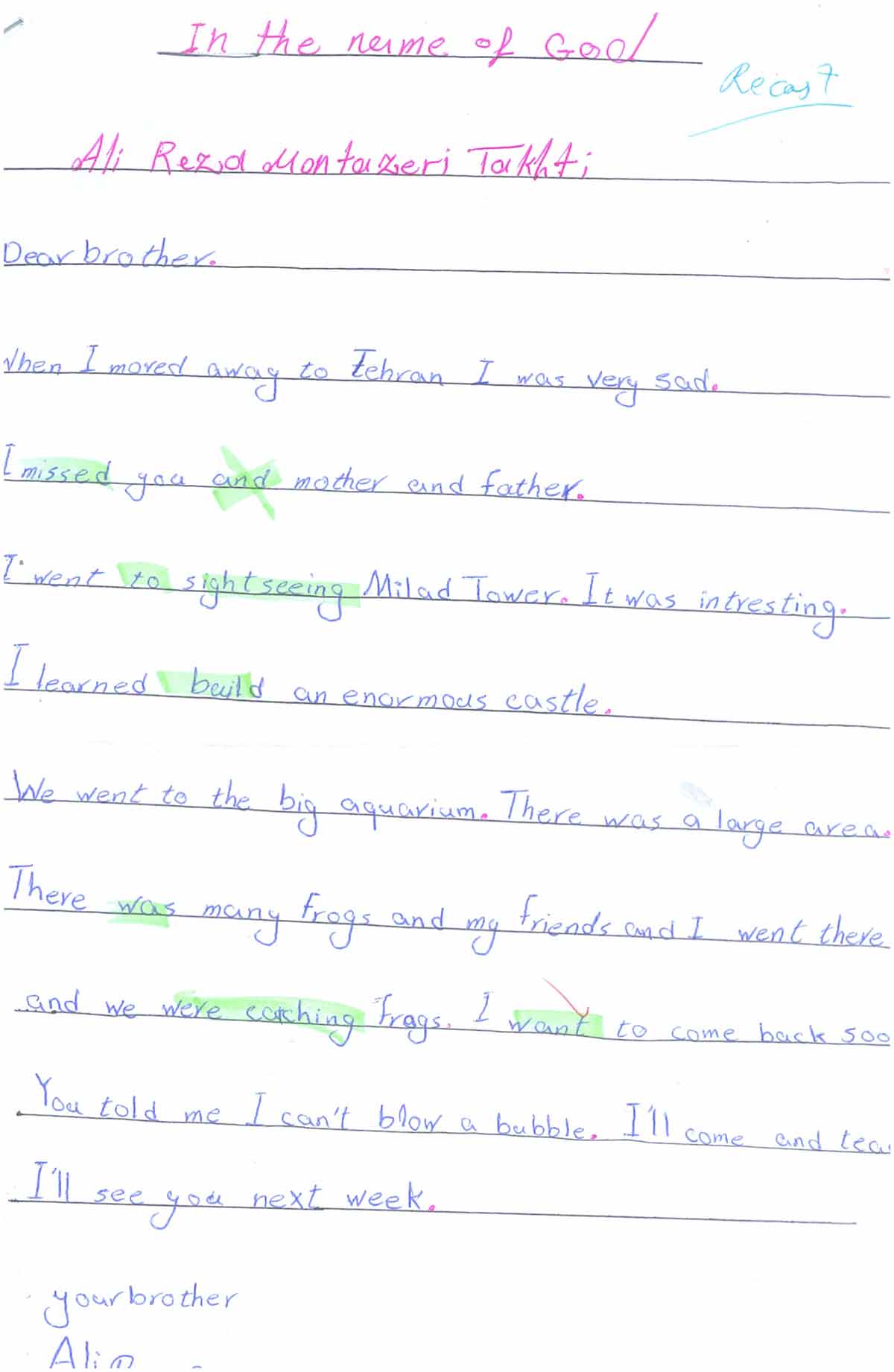

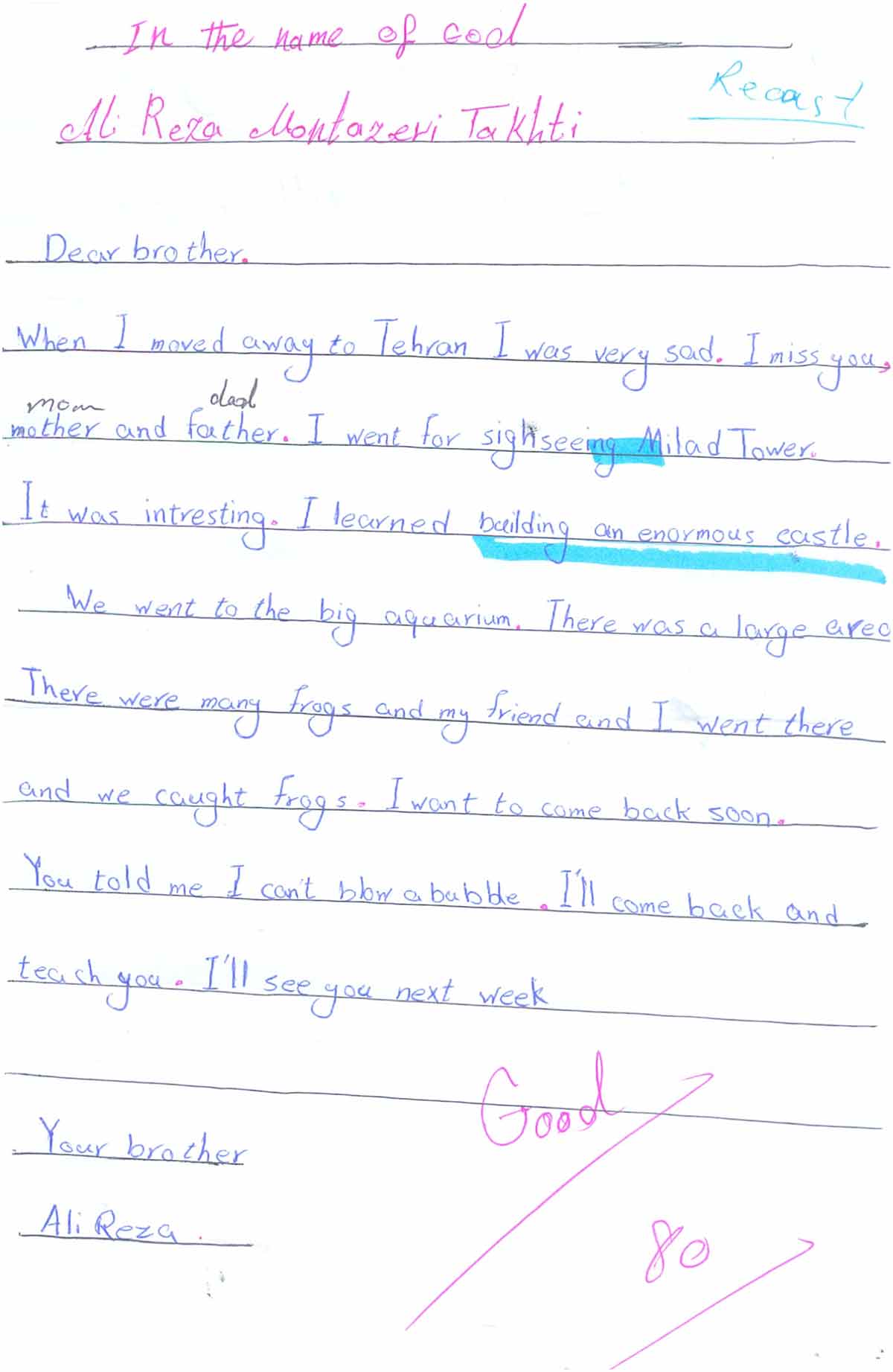

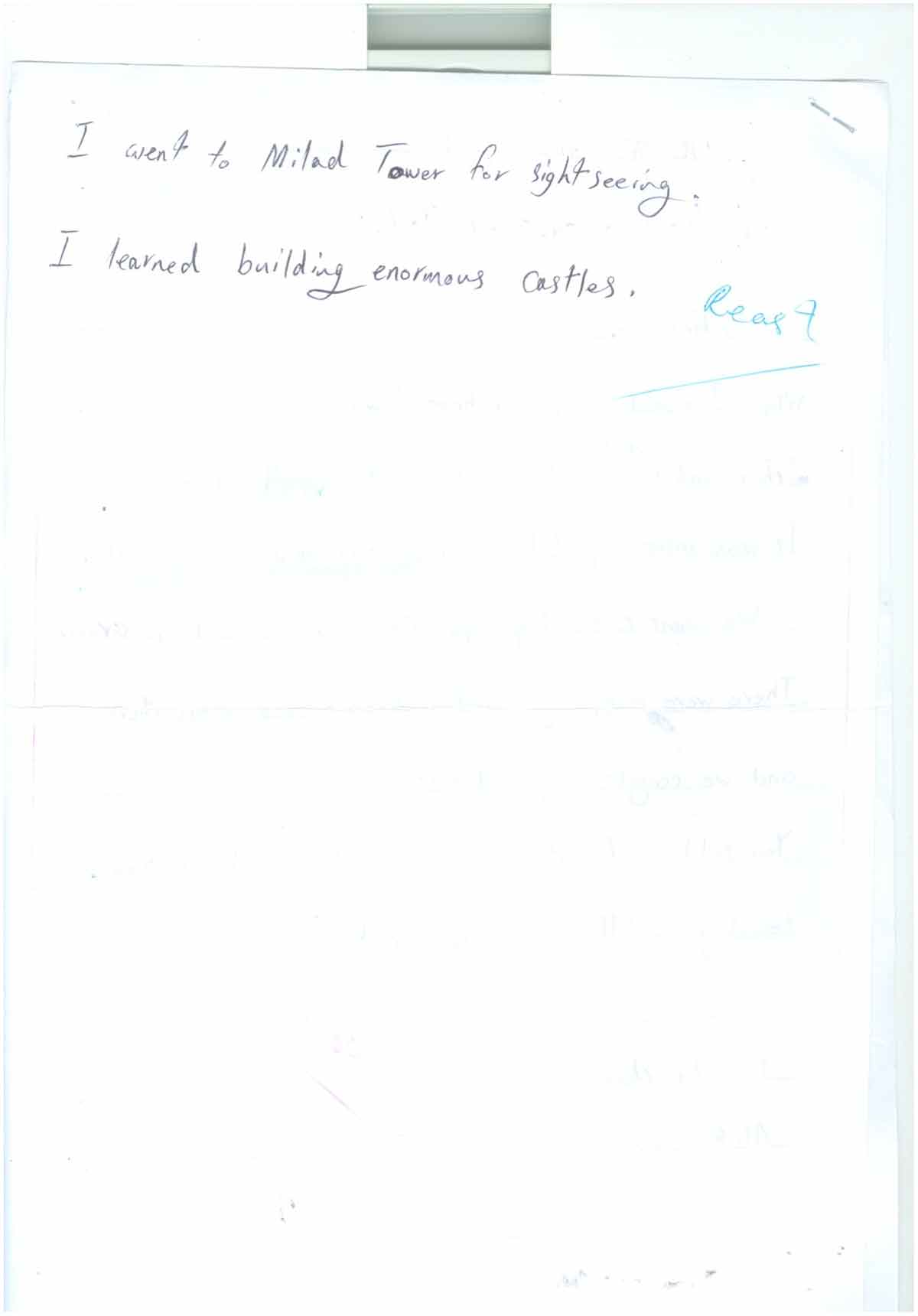

At first two intact classes were chosen. Secondly, writing was assigned within 20 sessions and the learners received recasts in two phases. The time dedicated to a learner’s writing was a total of 272 s on average. The participants took part in classes twice a week and studied the book English Time 5 as the focal material, practiced listening, speaking and reading skills inside the classroom, studied new words and practiced sentence making within the class, yet did their writings outside the classroom as their assigned projects. Phase one: initially, the participants took part in vocabulary learning and sentence making exercises based on the designed syllabus (this teaching took place in both classes). The learners practiced a dialog and a reading on the same topic. Subsequently, they were assigned to write a paper based on the topic they had already practiced for the following session. After providing the students with the course materials needed, in the second week, they submitted their first writing assignment, which the teacher/researcher received and provided feedback on by highlighting a single word to a complete sentence as the clarification request, highlighting some spaces before or after a word as the addition request and highlighting below or above a complete phrase or a sentence as the substitution request and gave the writings back to the participants (different types of highlighting were explained orally while giving students their writings back in order to avoid learner confusion) and asked them to correct the mistakes they had made and revise the same writing for the next session. The correction process was timed for each paper. As an average, a writing of 120 words took the teacher/researcher 2 min and 10 s to read. When it came to providing feedback in the first phase of recast, the highlighting process only added 12 s to the reading time. The teacher also applied grading and scored their writings out of 100, and sometimes wrote encouraging words as; good, nice work, well done, perfect, or even “Practice more”. The purpose of this grading was to ensure the learners that their works were being evaluated and the whole process was under close observation. Accordingly, they were aware that the better writing they wrote on the next assignment, the higher average they would achieve.

Phase two: the teacher received the revised writings attached to the first ones; in this stage, he scrutinized the writings and provided recasts to the repeated mistakes and any new mistakes encountered on the second text by writing the reformulated phrases or sentences while keeping the initial meaning. The reformulations were written down behind the learners’ writing sheets; the purpose was to provide learners with quick access to the feedback anytime they read their writing. At this stage, the correction process was also timed for each paper. Every paper needed two minutes on average to be corrected. In this respect, every paper needed 4 min and 22 s to be corrected. Hence, about 90 minutes was spent on providing recasts on 20 learners’ writings. The writings were given back to the students for reviewing. The writings were graded the second time and at this time the learners received higher scores in comparison to their previous writings. The aim of this ascending scoring was to motivate them as they were writing more drafts. This type of recasts was repeated five times during the term, before giving the students the posttest.

3.4.2. Direct feedback group procedure

The second group (direct feedback), received direct corrective feedback which is the conventional pedagogical methodology. In line with the teaching initiation, the participants practiced a dialog and a reading in the same topic. The focus of the dialog and the reading were on teaching vocabulary and sentence making. The learners were assigned to write on the same topic of their practiced unit. After providing the students with the course materials needed, in the second week, they had their first writing assignment, which the teacher/researcher received precisely as was done for the recasts group. For the direct feedback group, explicit correction was given directly to the writings. The teacher corrected all of the students’ mistakes and errors on the same paper in an unfocused corrective fashion and gave them back their writings the following session. The correction process was timed and 5 min and 8 s was spent by the teacher/researcher on every learner’s writing on average. In this respect, a class of 20 learners took around 1 hour and 45 minutes to be corrected. The papers were scored and the learners were aware of the outcome. Long explanations, if necessary, were provided orally in the classroom while returning the writing to the students. This type of direct feedback was repeated for five times during the term, before assigning the students a final writing task as the posttest. This study takes advantage of the process approach to writing evaluation and teaching.

3.5. Data analysis

An Alpha Cronbach test was run to analyze the inter-rater reliability of the three raters’ scores on both pretest and posttest. Two independent samples t-tests were run to compare the performances of the two groups before and after treatment. The aim of the first independent samples t-test was to ensure that the two groups were at the same level of proficiency before receiving the treatment. The aim of the second independent samples t-test was to compare the performance of the two groups after the treatment. In addition, two dependent samples t-tests were run. The aim of the first was to compare the performance of learners in recast group before and after the treatment. The aim of the second dependent samples t-test was to compare the performance of the learners in the direct feedback group before and after the treatment.

4. Results

In order to evaluate the reliability of the scores rated by three different raters, an Alpha Cronbach’s inter-rater reliability test was employed. The results obtained from the Alpha Cronbach inter-rater reliability test indicated that there is a highly significant inter-reliability of all three raters’ evaluations. The alpha data obtained were 0.92 for the control group pretest, 0.92 for the experimental group pretest, 0.80 for the control group posttest, and 0.85 for the experimental group posttest which are close to 1 and indicate that the evaluation was not excessively subjective.

In the following part, the descriptive statistics for the writing performance of high school EFL learners are presented. The homogeneity of the direct feedback and recast groups in the pretest is presented below.

The results given in Table indicate that the difference between the means obtained by the direct feedback group and the recast group are not statistically significant; the p-value obtained from the independent t-test was 0.461. Table shows that the mean score attained from the pretest writing scores between the control group and the experimental group was very close and indicated their homogeneity. The statistical results obtained from the paired samples t-test run on the performance of the recast group before and after the treatment indicated significant gains, the obtained p-value was 0.0001. The mean obtained from the performance on pretest was 5.07 and the mean obtained from the posttest was 5.75. The difference between the pre and posttest means was 0.67. Based on this result, it can be concluded that providing the high school EFL learners with recasts on the errors in their writing in particular is probably positively effective in their writing performance development.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for pretest scores

Do recasts enhance writing performance in comparison to direct corrective feedback? Is there any meaningful difference regarding the writing scores of the two experimental groups in the posttest?

The descriptive statistics for the posttest scores can be seen in Table . The results from the independent samples t-test showed that the students in both the recast group and the direct feedback group improved significantly in their writing performance. Also, the difference between the means obtained by the direct feedback group and the recast group on the posttest is staistically significant; the obtained p-value was 0.00081. Based on the comparison of the two groups, the results revealed that the t-observed values are higher than the critical value in two pairs (pre-test vs. post-test) indicating that the difference between the performance of the participants in the pretest and the posttest was statistically significant. This suggests that the participants in the both groups benefited from the feedback types provided, yet the recast group superseded the direct feedback group. In order to answer the question “Does direct corrective feedback have any effect on high school EFL learners’ writing performance?”, the following data analysis was applied. The means of the scores obtained by the direct feedback group on the pretest were 4.98, and 5.30 for posttest. The difference between the pretest mean and posttest mean for the direct feedback is 0.32. As P is zero, less than 0.5 (p > 0.005), the difference between the mean of pretest and that of posttest is statistically significant.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for posttest scores

5. Discussions and conclusions

Results obtained in this study suggest that both recast and direct corrective feedback have a significant impact on the writing performance of language learners. It seems that both of them could be effective tools for encouraging learners to identify their errors in writing and to correct their errors. It was revealed that there was a prominent difference between the performance of recast and direct feedback on the posttest; the recast group had better performance in comparison to the direct feedback group which confirmed the second hypothesis; the recasts had a statistically significant effect on the writing ability of high school EFL learners. Some researchers have suggested recasts are less effective than other types of feedback (Lyster & Ranta, Citation1997; Panova & Lyster, Citation2002; Long, Citation2006; Loewen & Philp, Citation2006; Khatib, Rezaei & Derakkhshan, Citation2011). It is necessary to highlight that these studies investigated the efficacy of recasts in speaking performance. Not only was recast effective in developing learners’ writing performance in the current study, it also outperformed the other feedback device, direct corrective feedback. This finding was also in contrast with those who argued against the effectiveness of corrective feedback (Chiang, Citation2004; Hyland, Citation2000; Hyland & Hyland, Citation2001; Semke, Citation1984; Straub, Citation1997; Truscott, Citation1996, Citation1999, Citation2004, Citation2007; Xu, Citation2009; Zamel, Citation1985). The finding of the study was in accordance with other studies (such as Ayoun, Citation2001; Doughty & Varela, Citation1998; Long, Citation2006; Maleki & Eslami, Citation2013; Nassaji, Citation2009; Zabihi, Citation2013) which have found recast effective on the development of writing skills.

Leki (Citation1991) proposed that it is more effective to provide learners with qualitative feedback about their strengths and weaknesses. Several scholars (e.g. Ferris & Hedgcock, Citation2005; Goldstein, Citation2004; Linn & Miller, Citation2005) have emphasized the effectiveness of assessing and grading learners’ writings. They have suggested that grading learners’ writings encourages them to revise their papers more attentively. Ruegg (Citation2014) concluded that assessing learners’ feedback leads to higher feedback uptake. In her study, the teacher scored learners’ writings in the two experimental groups, and it was observed that learners seemed more responsible for their work after receiving scores. This reaffirms findings from several studies (e.g. Ferris & Hedgcock, Citation2005; Goldstein, Citation2004; Hamp-Lyons & Condon, Citation2000; Linn & Miller, Citation2005; Ruegg, Citation2015a). This practice pushes learners to utilize the teachers’ feedback in their writing.

Time management is a heated controversy in issues surrounding classroom management, materials development, curriculum design, and teaching techniques. The results obtained from the analysis of the time spent on these two types of corrective feedback are so interesting and helpful. At first sight, having a quick look at the process of providing learners with written recasts seemed lengthy. The reason was considering the highlighting process with different codes in one phase, and reading the revised version of the writings on the second phase while writing the reformulations would be so time consuming. On the other hand, writing corrections of all learners’ errors directly at the exact place of the occurrence of errors and doing it in one phase of reading would seem less time-consuming. Yet, having the two processes timed, we found that providing recasts takes much less time in comparison to direct corrective feedback. By meticulous observation, it was found that the reason correcting every error was more time-consuming in the direct feedback group, while the highlighting process did not need much time in the recast group, despite providing feedback twice to this group was that on the second draft of the writing most of the errors had been corrected by the learners. Therefore, the teacher only had to reformulate a few sentences or expressions.

6. Limitations

The number of participants in this study was only 40 which is a small sample of EFL learners intra-culturally and cross-culturally. Hence, studies with bigger samples within a particular educational setting or cross-culturally would add valuable information to the findings of this study. The comparison of recast was limited to direct corrective feedback mainly because this is the conventional method of correcting learners’ writing in EFL classes in Iran, which is based on the old and perhaps outdated perception of considering direct written corrective feedback as a fast and effective correction process.

A major limitation of this study was the inequality of the time and stages spent on the learners’ writings. Receiving direct corrective feedback twice was not possible for learners. The reason was the nature of this type of error correction which is the correction of errors on the spot. Consequently, this made the learners and the teacher less involved (based on the stages—they only spent one time on each text) with the ongoing process of writing. The department in which the research was conducted did not permit writing within the class time as an in-class activity which limited our observation of the writing as their final outcome and we were not able to follow their writing process step by step while having them write in the classes under close observation.

7. Suggestions for further research and pedagogical implications

The current study aimed to examine the effect of recasts on the writing performance of high school EFL learners. According to the analyses, there were significant differences between the recast group and the direct feedback group. Considering the finding it can be concluded that recasts are more effective than direct feedback in improving the writing performance of high school EFL learners. The results of this study suggest implications for language teachers, teachers’ manuals in the domain of error correction types, and modifications to language institutes lesson plans, and methodology. This study revealed that recast as an indirect feedback was less time-consuming, analysis of various types of indirect corrective feedback can help researchers obtain a clearer understanding of their effectiveness. This could make a significant contribution to current teaching and learning pedagogy. Teachers’ guides can also suggest error correction practices based on research findings. It is recommended that teachers bring variety to the way they deliver their feedback and make their feedback more tangible and traceable. This can take place by providing written feedback. Moreover, this study suggests that teachers do not put all of their eggs in one basket, and do not wrap up the feedback process at a time. The way that recast was provided in this study gives learners the chance to receive feedback more than once and feel the sense of achievement after every revised draft of their writing. Above all, we suggest that both implicit and explicit feedback enhances learners’ performance on writing and this would be a movement from implicitness to explicitness between drafts. Many researchers have focused on the effect of recasts dealing with spoken performance of learners especially on adults, while this research focused on the writing performance of high school learners. Therefore, it may contribute satisfying information which can be the basis for more research in the current domain.

Funding

The authors received no direct funding for this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hassan Banaruee

Hassan Banaruee is a PhD candidate of TESOL at Chabahar Maritime University. His research interests include Neurolanguage Teaching, Educational Psychology, Philosophy of Language, and Metaphor Comprehension. He currently researches the philosophy and psychology of error correction and psycholinguistic aspects of lexical and semantic patterning.

Omid Khatin-Zadeh

Omid Khatin-Zadeh is a PhD candidate at Chabahar Maritime University. His research interests include metaphor comprehension and mathematical isomorphic domains.

Rachael Ruegg

Rachael Ruegg received a PhD in Linguistics from Macquarie University, Australia. She is currently a lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her research interests include instruction and assessment of writing, English for Academic Purposes, and learner autonomy.

References

- Ammar, A., & Spada, N. (2006). One size fits all? Recasts, prompts, and L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 543–574.

- Ayoun, D. (2001). The role of negative and positive feedback in the second language acquisition of the “passé compose” and the “imparfait”. The Modern Language Journal, 85(2), 226–243.10.1111/modl.2001.85.issue-2

- Banaruee, H. (2016). Recast in writing. Isfahan: Sana Gostar Publications.

- Banaruee, H., & Askari, A. (2016). Typology of corrective feedback and error analysis. Isfahan: Sana Gostar Publications.

- Banaruee, H., Khoshsima, H., & Askari, A. (2017). Corrective feedback and personality type: A case study of Iranian L2 learners. Global Journal of Educational Studies, 3(2), 14–21. doi:10.5296/gjes.v3i2.11501

- Bitchener, J., & Knoch, U. (2008). The value of written corrective feedback for migrant and international students. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 409–431.10.1177/1362168808089924

- Bohannon, J. N., Padgett, R. J., Nelson, K. E., & Mark, M. (1996). Finding relations between input and outcome in language acquisition. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 556–559.

- Braidi, S. M. (2002). Reexaming the role of recasts in native-speaker/non-native speaker interactions. Language Learning, 52, 1–42.10.1111/lang.2002.52.issue-1

- Brown, D. H. (2007). First language acquisition. Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson ESL.

- Carpenter, H., Jeon, K. S., MacGregor, D., & Mackey, A. (2006). Learners’ interpretation of recasts. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 209–236.

- Chandler, J. (2003). The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(3), 267–296. doi:10.1016/s1060-3743(03)00038-9

- Chiang, K. (2004). An investigation into students’ preferences for and responses to teacher feedback and its implications for writing teachers. Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal, 3, 98–115. Retrieved from http://edb.org.hk/HKTC/download/journal/j3/10.pdf

- Cohen, A., & Cavalcanti, M. (1990). Feedback on compositions: Teacher and student verbal reports. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing (pp. 155–177). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139524551.015

- Doughty, H., & Varela, E. (1998). Communicative focus on form. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 114–138). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Egi, T. (2007). Interpreting recasts as linguistic evidence: The roles of linguistic target, length, and degree of change. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 29, 511–537.

- Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ellis, R., & Sheen, Y. (2006). Reexamining the role of recasts in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 575–600. doi:10.1017/s027226310606027x

- Fazio, L. (2001). The effect of corrections and commentaries on the journal writing accuracy of minority- and majority-language students. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(4), 235–249. doi:10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00042-X

- Ferris, D. (1995). Student reactions to teacher response in multiple-draft composition classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 33–53. doi:10.2307/3587804

- Ferris, D. (2003). Response to student writing: Implications for second language students. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ferris, D., & Hedgcock, J. (2005). Teaching ESL composition: Purpose, process, practice. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ferris, D. R., & Roberts, B. (2001). Error feedback in L2 writing classes Journal of Second Language Writing, 10, 161–184.10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00039-X

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387.10.2307/356600

- Goldstein, L. (2004). Questions and answers about teacher written commentary and student revision: Teachers and students working together. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 63–80. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2004.04.006

- Hamp-Lyons, L., & Condon, W. (2000). Assessing the portfolio: Principles for practice, theory and research. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Han, Z. (2002). A study of the impact on tense consistency in L2 output. TESOL Quarterly, 36, 543–572.10.2307/3588240

- Hedgcock, J., & Lefkowitz, N. (1994). Feedback on feedback: Assessing learner receptivity to teacher response in L2 composing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 141–163.10.1016/1060-3743(94)90012-4

- Hendrikson, J. (1980). The treatment of error in written work. Modern Language Journal, 64, 264–271.

- Hyland, F. (2000). ESL writers and feedback: Giving more autonomy to students. Language Teaching Research, 4(1), 33–54.10.1177/136216880000400103

- Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the Pill: Praise and criticism in written feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10, 185–212. doi:10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00038-8

- Kepner, C. (1991). An experiment in the relationship of types of written feedback to the development of second-language writing skills. The Modern Language Journal, 75, 305–313.10.1111/modl.1991.75.issue-3

- Khatib, M., Rezaei, S., & Derakkhshan, A. (2011). Literature in ESL/EFL classroom. English Language Teaching, 4(1), 201–208.

- Khoshsima, H., & Banaruee, H. (2017). L1 interfering and L2 developmental writing errors among Iranian EFL learners. European Journal of English Language Teaching, 2(4), 1–14. doi:10.5281/zenodo.802945

- Knoblauch, C., & Brannon, L. (1984). Rhetorical traditions and the teaching of writing. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton/Cook.

- Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. New York, NY: Longman.

- Lalande, J. (1982). Reducing composition errors: An experiment. The Modern Language Journal, 66, 140–149.10.1111/modl.1982.66.issue-2

- Lee, I. (1997). ESL learners’ performance in error correction in writing: Some implications for teaching. System, 25(4), 465–477.10.1016/S0346-251X(97)00045-6

- Lee, I. (2004). Error correction in L2 secondary writing classrooms: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(4), 285–312.10.1016/j.jslw.2004.08.001

- Lee, I. (2008). Student reactions to teacher feedback in two Hong Kong secondary classrooms. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17, 144–164.10.1016/j.jslw.2007.12.001

- Leki, I. (1991). The preferences of ESL students for error correction in college-level writing classes. Foreign Language Annals, 24, 203–218.10.1111/flan.1991.24.issue-3

- Linn, R., & Miller, M. (2005). Measurement and assessment in teaching. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Loewen, S., & Philp, J. (2006). Recasts in adult English L2 classroom: Characteristics, explicitness, and effectiveness. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4), 536–556. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00465.x

- Long, M. (2006). Problems in SLA. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in l2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 51–81.10.1017/S027226319800103X

- Lyster, R. (2004). Differential effects of prompts and recasts in form-focused instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26, 399–432.

- Lyster, R., & Izquierdo, J. (2009). Prompts versus recasts in dyadic interaction. Language Learning, 59(2), 453–498.

- Lyster, R., & Mori, H. (2006). Interactional feedback and instructional counterbalance. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 269–300.

- Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66. doi:10.1017/s0272263197001034

- Mackey, A., & Oliver, R. (2002). Interactional feedback and children’s L2 development. System, 30, 459–477.10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00049-0

- Mackey, A., & Philp, J. (1998). Conversational interaction and second language development: Recasts, responses and red herrings. The Modern Language Journal, 82, 338–356.10.1111/modl.1998.82.issue-3

- Maleki, A., & Eslami, E. (2013). The effects of written corrective feedback techniques on EFL students’ control over grammatical construction of their written English. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(7), 1250–1257.

- Nassaji, H. (2009). Effects of recasts and elicitations in dyadic interaction and the role of feedback explicitness. Language Learning, 59(2), 411–452. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00511.x

- Panova, I., & Lyster, R. (2002). Patterns of corrective feedback and uptake in an adult ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), 573–595. doi:10.2307/3588241

- Philp, J. (2003). Constrains on “noticing the gap”. Non-native speakers’ noticing of recast in NS-NNS interaction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 25(1), 99–126. doi:10.1017/s0272263103000044

- Pienemann, M. (1998). Language processing and second language development: Processability theory. Studies in Bilingualism (Vol. 15). Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamin. doi:10.1075/sibil.15

- Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511667190

- Ruegg, R. (2010). Who wants feedback and does it make any difference? In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT2009 Conference Proceedings (pp. 683–691). Tokyo: JALT.

- Ruegg, R. (2014). The effect of assessment of process after receiving teacher feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.998168

- Ruegg, R. (2015a). The influence of assessment of classroom writing on feedback processes and product vs. on product alone. Writing & Pedagogy, 7(2–3). doi:10.1558/wap.v7i2-3.16672

- Ruegg, R. (2015b). Student uptake of teacher written feedback on writing. Asian EFL Journal, 17(1), 36–56.

- Ruegg, R. (2017). Learner revision practices and perceptions of peer and teacher feedback. Writing & Pedagogy, 9(2), 275–300. doi:10.1558/wap.33157

- Ruegg, R. (2018). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on changes in EFL students’ writing self-efficacy. The Language Learning Journal, 46(2), 87–102. doi:10.1080/09571736.2014.958190

- Semke, H. (1984). The effects of the red pen. Foreign Language Annals, 17, 195–202.10.1111/flan.1984.17.issue-3

- Sheen, Y. (2006). Exploring the relationship between characteristics of recasts and learner uptake. Language Teaching Research, 10(4), 361–392. doi:10.1191/1362168806lr203oa

- Sheppard, K. (1992). Two feedback types: Do they make a difference? RELC Journal, 23, 103–110.10.1177/003368829202300107

- Sommers, N. (1982). Responding to student writing. College Composition and Communication, 33(2), 148–156.10.2307/357622

- Straub, R. (1997). Students’ reactions to teacher comments: An exploratory study. Research in the Teaching of English, 31(1), 91–119.

- Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language Learning, 46(2), 327–369.10.1111/lang.1996.46.issue-2

- Truscott, J. (1999). The case for “The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes”: A response to Ferris. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8, 111–122.10.1016/S1060-3743(99)80124-6

- Truscott, J. (2004). Evidence and conjecture on the effects of correction: A response to Chandler. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 337–343.10.1016/j.jslw.2004.05.002

- Truscott, J. (2007). The effect of error correction on learners’ ability to write accurately. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(4), 255–272. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2007.06.003

- Xu, C. (2009). Overgeneralization from a narrow focus: A response to Ellis et al. (2008) and Bitchener (2008). Journal of Second Language Writing, 18, 270–275.10.1016/j.jslw.2009.05.005

- Zabihi, S. (2013). The effect of recast on Iranian EFL learners’ writing achievement. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 2(6), 28–35. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.2n.6p.28

- Zacharias, N. (2007). Teacher and student attitudes toward teacher feedback. RELC Journal, 38(1), 38–52. doi:10.1177/0033688206076157

- Zamel, V. (1985). Responding to student writing. TESOL Quarterly, 19(1), 79–101. doi:10.2307/3586773

Appendix 1

IELTS essays – checklist for evaluators

Evaluator 1

Evaluator 2

Evaluator 3