Abstract

Fostering positive and meaningful change amongst South African youth whose schooling and life experiences have rendered them largely ill-prepared, demotivated and often traumatised, is a complex endeavour, but one which needs urgent attention. Government programmes tend to ignore the psycho-social demands of the transition from unemployed hopelessness to career-oriented hopefulness. This article reports on a case study of a non-formal learning programme, offered by World Changers Academy (WCA), which has been found to be successful in building such psychological career resources amongst marginalised youth. It discusses four aspects of the learning process and the nature of learning which has led to some life-altering changes in youth participating in the programme. These are emotions, healing and hopefulness; identity, purpose and self-confidence; reflection and changing mindsets; community engagement, relationships and authenticity. Lessons from this programme could help in the development of more widespread provision for youth in South Africa and elsewhere.

Public Interest Statement

South Africa’s large population of youth who are not in employment, education or training, has long given rise to apocalyptic predictions of this being a “ticking time bomb”. While policy and programmes to propel more youth into learning and employment are receiving attention, many of these efforts ignore the psycho-social demands of the transition from unemployed hopelessness to career-oriented hopefulness. This article reports on a case study of a non-formal learning programme which focuses on building such psychological career resources amongst marginalised youth. It discusses four aspects of the learning process and the nature of learning which has led to some life-altering changes in youth participating in the programme. These are emotions, healing and hopefulness; identity, purpose and self-confidence; reflection and changing mindsets; community engagement, relationships and authenticity. Lessons from this programme could help in the development of more widespread provision for youth in South Africa and elsewhere.

1. Introduction

One of South Africa’s most serious challenges is its large population of youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEETs). The growth of this sector, the so-called NEETs, has long given rise to apocalyptic predictions of this being South Africa’s “ticking time bomb”. Recent violent protests by students at universities in South Africa have brought to the fore the anger, alienation and impatience felt by youth generally. There is widespread agreement across government and civil society that something has to be done! While government has been developing policy and programmes to propel more youth into learning and employment, many of these efforts fail to recognise the levels of preparation, reorientation and pedagogical engagement required. Fostering meaningful change in identity, learning and direction amongst youth whose schooling and life experiences have rendered them largely ill-prepared, demotivated and often traumatised, is a complex endeavour.

Government programmes in South Africa tend to ignore the psycho-social demands of the transition from unemployed hopelessness to career-oriented hopefulness. In this regard, Coetzee and Esterhuizen refer to the important construct of “psychological career resources”, defined as:

The set of career-related preferences, values, attitudes, abilities and attributes that lead to self-empowering, proactive career behavior that promotes general employability. (Coetzee, as cited by Coetzee & Esterhuizen, Citation2010, p. 869)

Coetzee and Esterhuizen’s study shows that some of the skills needed for employability are linked to strength of mind and an ability to cope psychologically with various changes and challenges in the transition to the workplace. This includes the important work of broadening one’s mindset and perspectives in order to chart a new future. Where can youth gain such important skills?

This article reports on a case study of a non-formal learning programme, offered by World Changers Academy (WCA), which focuses on building such psychological career resources amongst marginalised youth. Since 2002, WCA has been engaging unemployed young adults through programmes that foster healing and hope. Two independent studies of WCA (Momo, Citation2009) and (Hazell, Citation2010) support the types of significant change that WCA claim that many of their students experience. The stories of life-altering change that many of the participants of the programme experience, initiated a research interest to explore the WCA programme as a case of a non-formal leadership programme for unemployed youth.

This study therefore sought to explore such changes and to investigate the nature and processes of learning which fostered such change by asking “What aspects of the programme have fostered change in participants?” Much could be learnt from a closer, in-depth look at these learning processes and experiences in the programmes at WCA. If we can understand what WCA does and the nature of the learning which transforms or empowers individuals on this programme, we could learn some valuable lessons about how to foster such change in other similar contexts in South Africa and elsewhere. The article therefore identifies and discusses four aspects of the learning process and the nature of learning which has led to some life-altering changes in youth participating in the WCA programme. These are emotions, healing and hopefulness; identity, self-confidence and purpose; reflection and changing mindsets; community engagement, relationships and authenticity.

2. Context

2.1. South African youth

Youth unemployment is a global concern, but in South Africa, as in much of Africa the problem is particularly alarming and a concern of both government and civil society. Reasons for the high rates of unemployment in South Africa are multi-faceted and complex and include the legacy of structural unemployment from the days of apartheid (Mohomed, Citation2002). Although the ANC government has made various attempts to address this issue the unemployment rates remain unacceptably high more than two decades into democracy.

Government intervention involved policy reform in the 1990s including policy on education, training and labour. Human Capital Theory (HCT), the prevailing global discourse on the relationship between education and labour, is the underlying philosophy informing these policies . The premise is that education and training will increase the productivity of individual workers and ultimately impact national economic performance. Thus, the intention behind the reformed policies was to make education more responsive to the needs of the labour market. Vally and Motala (Citation2014) argue that the premise of HCT needs critical reflection as it over-simplifies the much more complex relationship between education, training and labour. The critique of HCT is that it focuses only on the commodity value of people and not on the other important aspects of being human and being a citizen of a country.

Policy reform in education and training resulted in the establishment of a national qualifications framework (NQF). The intention was to reform the education landscape, in particular regarding vocational skills addressed through the Further Education and Training (FET) sector (now known as the Technical and Vocational Education and Training section). The original intention of FET colleges was to provide an NQF 4 qualification, the same level as a final school-leaving certificate at Grade 12. These colleges were intended as “second-chance” institutions for those who dropped out of school after Grade 9 (NQF 1) and wanted to achieve an NQF 4 through a more vocational route. However, many who enroll at FET colleges to pursue vocational qualification have already achieved a school matric pass of NQF 4 level (Cosser, Citation2010) and hence are not progressing in their qualification level. Wedekind (Citation2014) outlines the various reforms that have taken place within the college sector since 1994 and argues that despite the various reforms, the continued underlying policy of aligning the education system to the labour market remains. Wedekind (Citation2014) therefore suggests that the wider purposes of education in society need to also be considered. It seems the underlying premise of HCT limits such consideration.

A more recent but controversial Government response to the youth unemployment crisis, has been the implementation of a youth wage subsidy (YWS). The goal of the YWS is to reduce youth unemployment by lowering the cost for employers of hiring youth who have never been employed. Reddy (Citation2014) argues that it is likely that the youth wage subsidy will not increase employment levels but rather create churning, where employers simply substitute older workers for younger workers at a much lower cost. This is particularly likely in the South African context where employers favour casualised work and could easily make the changes, without having any significant effect on unemployment (Reddy, Citation2014). The initiative also does not take into consideration the preparedness (or lack of preparedness) of school leavers for the workplace, particularly the psycho-social aspects which we argue are an important element of school to work transitions for young people.

Swartz and Soudien (Citation2015) advocate that youth need a range of capitals, like social capital and cultural capital to be empowered for the workplace and not just work related skills. They furthermore emphasise the importance of youth agency and involvement in community-based initiatives aimed at facilitating school to work transitions for young people. Bastien and Holmarsdottir (Citation2015) also advocated for youth agency as an important aspect of addressing youth unemployment problems. As discussed below, agency and community engagement are given significant attention in the WCA programme.

This article, through the study of the WCA programme, highlights the important role that civil society can play in empowering unemployed youth. The study shows the important role of developing skills amongst the youth that will prepare them to be better citizens and to be better prepared for employment or entrepreneurship.

2.2. World changers academy

WCA, a non-profit organisation based in Shongweni, KwaZulu-Natal, aims to empower young adults for work through life skills and leadership training courses. Their courses also help students find ways to gain valuable work experience. WCA focuses on students’ attitudes and mindsets, while also providing knowledge and skills, by focusing on the roots of the problems faced by youth. WCA’s aims to raise leaders of high integrity in communities, who will positively impact their communities, imparting skills and attributes which they have learnt and implemented in their own lives.

WCA identifies communities where there are high levels of unemployment and invites unemployed youth who have finished school to attend a Life Skills course. The course takes place each weekday morning for four weeks within these communities. The Life Skills Course focuses on “changing the world within” as indicated on the WCA website as of 19 July 2011. Topics covered on the Life Skills course include Vision and Goal Setting; Worldview, African Renaissance and Job Preparation Skills. Furthermore, students are encouraged to be productive in their communities and, depending on their needs and interests, are channelled into various jobs, study or entrepreneurial opportunities.

About 10% of the students from Life Skills courses proceed to the “Leadership” courses which are eleven weeks long. Leadership courses are divided into three phases: lecture phase; community volunteer phase and then feedback phase. The Leadership Course takes place at the WCA premises in Shongweni. The focus of the Leadership Course is “changing the world around us” as indicated on the WCA website as of 19 July 2011 and builds on the topics covered in Life Skills, by focusing on raising future leaders for communities. These two courses are closely linked and this study investigated change in participants who had been through both of the courses. Thus the term chosen to describe this combination will be the WCA Programme.

The values of the WCA Programme include volunteerism and community involvement. These are addressed during Life Skills as part of the curriculum, and during Leadership as a major phase of the programme, when during a six-week period, students are required to go back to their community to do volunteer work. The purpose of this volunteer work is twofold. Firstly, it is a way of giving back to the community and teaching the value of community participation and involvement, and secondly, it is a way of gaining valuable work experience. One of the major disadvantages unemployed people carry in looking for work, is their lack of work experience. The community work requirement of the WCA programme helps participants gain both insight and experience in real workplaces, thus further preparing and empowering the participants for employment.

3. Methodology

The purpose of this study was to gain deeper understanding of what makes the WCA programme successful in fostering life-altering change. A qualitative, interpretative approach was most suited for this purpose (Henning, Citation2004). As predefined indicators of success were not available, this study adopted an exploratory case study design which sought to identify such indicators and factors leading to success (Yin, Citation2003). Such exploratory case studies can then allow for future explanatory case studies wherein ex-ante and ex-post change on the basis of predefined indicators can be determined. Case study methodology was used to create a rich and deep understanding of aspects of the programme that had been influential in the lives of participants. In keeping with case study methodology multiple data collection methods and multiple data sources were used to explore the experiences and stories of participants (Yin, Citation2003). Data were collected through observation, focus groups, in-depth interviews and some creative participatory methods like drawing. Participants ranged from those who had completed the first WCA programme in 2002, through to those who completed in 2011.

A limitation of the study was that it did not explore the shortcomings of programme or those who did not experience change. The aim of the study was to explore what aspects of the programme had contributed to change in those who had experienced it. Thus, it does not claim that all WCA participants undergo life-altering change, but intentionally foregrounds exemplary cases of change.

Hence, the method of sampling was purposive, in order to foreground particularly successful participants of the programme with the hope that they would be the richest sources of data. Purposive sampling is described as handpicking participants according to specific characteristics as needed by the research (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2007). The handpicking of participants for this study is explained below.

As outlined earlier, the WCA programme consists of a life skills followed by a leadership course to which about 10% of the life skills participants are invited. About 10% of the Leadership students then spend a period of time in a phase of voluntary work for the organisation where their leadership potential is further developed. Finally, about 50% of those that complete this volunteer phase become WCA staff. All the participants of this study had completed the WCA programme. Furthermore, the three primary participants were working as staff in the organisation at the time of the study.

Prior to encountering the WCA life skills course, the primary participants were educated, but unemployed. They wanted to find work, but did not indicate that they were proactively looking for employment and they were not engaged in other work or study related activities. Thus, the WCA programme was particularly significant in a process of change that these young people had experienced.

Thematic data analysis methods were used to make sense of the data. Four key aspects of the learning process were identified through this analysis. The three primary participants, Mandla, Nothando and Kosan, reported experience of all four aspects of learning, while a fourth participant, Nobuhle, strongly reflected two of these aspects. For the purpose of the study, these four participants were given pseudonyms and will be introduced below. The pseudonyms were chosen to reflect aspects of each participant’s character, in keeping with African culture in which the meaning of names is particularly important. Other participant’s quotes and stories add further depth and insight into the understanding of the learning and change in participants on the WCA programme, but were not given names in the study.

Mandla (meaning: strength or power) grew up with both parents and a number of siblings in extreme poverty. The WCA programme seemed to foster a strength and confidence in him. He completed the WCA programme in 2008.

Nothando (meaning: Love or “mother of love”) grew up knowing both parents but going regularly between their two homes, as her parents were not married. Through the WCA programme she overcame many of her insecurities and emerged as a young woman able to give love and compassion to others. She completed the WCA programme in 2008.

Kosan (meaning: leader) came from a single parent home, never knowing his father, or even who his father was. His learning on the WCA programme enabled him to overcome his shyness and to fill a leadership role in the organisation. He completed the programme in 2005.

Nobuhle (meaning: Mother of beauty) loved expressing herself through creative drawing. Her drawings strongly reflect the first two aspects of learning that will be discussed. Nobuhle, completed the WCA programme in 2011.

The three primary participants of the study, were born in the last decade of apartheid and started their schooling around the time of transition to democracy in 1994. The history and context of the province has been outlined earlier and includes growing up in areas of conflict and violence. Furthermore, although they completed their schooling, at a crucial stage of their lives, when they should be furthering their education or finding work, they found themselves as one of many youth who were not in employment, education or training, despite the positive changes in the country and the hopefulness that came with democracy. It was during this time of transition that the participants encountered the WCA programme and over a period of time experienced life-altering change and learning.

Having introduced the primary participants, the four aspects of learning are discussed next.

4. Four aspects of the nature and process of learning

4.1. Emotions, healing and hopefulness

Emotions appear to play a significant role in the learning process of WCA students. Many participants used emotive words such as anger, pain, conflict, fear and confusion in telling their stories. Considering the history of hardship which most of these students and their families have come from, it made sense that issues of pain and anger were very real to them. However, along with these expressions of negative emotions, were also descriptions of positive emotions, like healing, hope, fun and joy. The topic “Healing of the Past” in the programme seemed instrumental in helping students deal with painful past issues, with a sense of hope emerging as a result.

When students were asked: “What changes have you experienced in your life since being involved in WCA?” some responses were:

I was very angry, holding grudges. I know now that I can’t live like that, that it is not a life.

Facing the issue of forgiveness … now I’m empowered to forgive.

These two students showed they had learnt about the negative impact of holding grudges and have learnt the power of forgiveness.

Another two responses were:

Healing, relationships and behavior to other people – I take decisions in a positive way now.

Helped me to be positive in life - I always had fear.

The above two quotes show that positive change had resulted from the programme, while the two following, express hope.

Bringing hope back, understand myself better and clear future.

It helped me find my identity and brings my hope back.

One student’s response illustrated that healing was still taking place, that it is a process and that it was not yet complete. When responding to the question, “What was challenging about the course?” he said:

Anger – it’s not easy to forgive but the more we learn about forgiveness, the more challenged we are to forgive. I’m not there yet, but I’m trying. (emphasis ours)

Another student responded:

The most challenging part [of the course was] dealing with anger management and forgiveness.

These final two examples demonstrate that the process of healing and forgiveness is not easy, and that it is a process which takes time and continual effort.

Mandla found the topic of “Healing of the past” very challenging, because it was difficult to face the past and forgive others. However, he didn’t run away from this challenge and was able to forgive and move forward positively with his life. One of the things Mandla had to do was face people from his past that he had treated badly. Mandla used to abuse alcohol and had been involved in gangs while he was at school. During the volunteer phase of the WCA programme, he had to go back to his old school where there were students who still knew him and his past behaviour. Since then he had turned his life around and had come to do motivational talks about self-management. This was an emotionally challenging situation to be in, but by working through it, he found healing and restoration.

Nothando was very self-conscious and self-absorbed when she started the WCA programme. She held a lot of pain and bitterness from her past, especially towards men, whom she had seen abusing women in her family. The WCA programme helped her to learn about healing and dealing with the past which she was able to put into practice. The emotional healing she experienced freed her to be more hopeful and positive about life and to work well with others. Kosan held deep hurt about not knowing his father and had very low self-esteem. Through the WCA programme he experienced emotional and spiritual healing that brought wholeness to him.

Nobuhle depicted emotional hurt and then healing most graphically through two drawings. Her first drawing (Figure ) suggested very strongly that deep emotional pain had been part of her early life.

Nobuhle said that this is a picture of a heart, which is red in some places, but should be all red. There is a spear through the heart and it has been bleeding, which has made it go pink. The black in the background is fear. To the right of the heart is another picture, which is the devil. Around the devil is blue, which is peace, but the devil comes into places of peace and destroys them. Around the blue is a range of colours, which are different emotions. Nobuhle’s description is a vivid depiction of a range of conflicting emotions, ranging from pain and fear, to an element of hope, because peace is also present.

Nobhule’s second drawing (Figure ), suggests that hope and peace are possible. This is a picture of a tall tree, with grass and flowers on the bank and a peaceful stream running next to it. Nobuhle explained that when she wants to get to a place of peace, she looks at this picture.

As can be seen from the quotes shown earlier as well as Nobhle’s drawings, although students displayed high levels of pain, using words like anger and fear about their past, there was also a message of hope emerging in the descriptions of change. Healing of the past, to face the pain and hurt, and to learn to forgive, seemed to be a significant step in helping them move forward in their life journeys with new hope.

4.2. Identity, self-confidence and purpose

A further key component of learning through the WCA Programme was that students established new positive identities which were accompanied by greater self-confidence and purpose. The further aspect of identity related to considerations of African identity. We discuss these features of identity next.

4.2.1. Positive personal identity

Many participants responded with the words identity and purpose when asked what the WCA Programme had done in their lives. For example, one student said it had helped him “to find my true identity”.

Other responses included references to a spiritual identity as the following two quotes illustrate:

It has empowered my life in terms of identity and about who God is

I now found my identity in God.

Similar comments were found on the WCA website (WCA, Citation2009) from past students about what the programme had done for them. Three examples follow:

I now know my purpose in life. I won’t sit at home any longer

I didn’t have a vision before, but I now know what I want.

I have learned about my true identity and that I was not a mistake. I’m now positive towards my future and believe in myself

Furthermore, two earlier studies of WCA, Momo (Citation2009) on the Life Skills course and Hazell (Citation2010) on the Leadership course, also found that students developed a sense of identity, direction and purpose for their lives. The present study confirms these findings.

The stories of Mandla, Nothando and Kosan strongly corroborate the finding on the centrality of identity and purpose to success. Each of them developed a sense of purpose for their lives, a sense of what they were good at and what they wanted to do with their lives, which has been illustrated through the pseudonyms chosen for them and recapped below.

Mandla (Strength) began the WCA Programme with an identity as a good soccer player, but knowing that he had destroyed his chances of becoming a professional player because of a drinking problem. Through the WCA Programme he discovered a new identity and strengths he didn’t know he possessed. He started recognising his skill at public speaking, which was affirmed by WCA leaders, and he proceeded to develop that skill. The manner in which he confidently and engagingly told his story, conveyed that his vision was based on accurate knowledge of his strengths and not just an unrealistic idea or dream.

Nothando (mother of love) experienced much confusion and conflict in her life growing up because her parents didn’t marry and she had to spend time between their homes. She said she often felt “caught in the middle” between her two parents. In other words she didn’t have a sense of belonging to a family unit and this caused confusion for her. Nothando started with WCA, as a self-conscious young woman who was afraid of standing up in front of people. She had a poor sense of self and of her place in this world. Now she has a heart for others and knows that she wants to be in a profession helping to empower people. The WCA Programme has facilitated her process of establishing a healthy identity of self.

Prior to the WCA programme, Kosan (leader) lacked a sense of identity, particularly from not knowing his father. He lacked male role-models in his life, was unsure of himself and was a loner. However, he emerged as a leader and pioneer, whose activities included mastering cycling and bringing the sport to the African community. After being a participant on the WCA programme, he had taken a leadership role in the organisation and become a facilitator of the leadership course. The WCA Programme seems to have helped him to find that identity and to live his life more purposefully.

These three life stories indicate that these participants have developed a sense of positive identity and purpose. It would also seem that they have found identity in their purpose and that finding a purpose seems key in developing a new positive identity.

4.2.2. Growing self-confidence as part of new identity

For Kosan and Nothando high levels of self-confidence appear to be part of their new identity. However, they described themselves as being shy and lacking confidence when they first joined WCA. This illustrates that the level of confidence each of them has gained has been significant. Their confidence grew as they progressed through the programme.

Mandla seemed to come to the WCA Programme showing more self-confidence than Kosan and Nothando, even speaking well in public on the first day. However, his journey was still one of self-discovery in which he grew in confidence and competence in new skills and knowledge of himself. Right from the start of the WCA Programme he realised his strength in public speaking, but it was through participating in the programme and getting affirmation and positive feedback from others, that he developed and honed this skill, growing in self-confidence.

Other participant’s, who had just completed their community service phase of the leadership programme at the time of data collection, seemed to have gained self-confidence from the experience. When asked what they had learnt through the volunteer experience, many highlighted that they had learnt about themselves and about what they are good at doing. The following four quotes reveal what participants had learned during the volunteer phase:

I discovered that I am good at teaching.

Learnt about myself – that I can be patient with kids

Discovered that I am able to teach so that they (others) can understand and enjoy the sessions

Learnt that others believe in me, that I am a leader

These findings affirm Hazell’s (Citation2010) study in which she reported that an increased sense of self-confidence was seen in WCA students. The growth of self-confidence in this context could be seen as part of the process of learning. As the students progressed through the programme, the step-by-step process of trying on new roles (like doing a small presentation in class) could be seen as an incremental step in the process of learning – a learning which saw self-conscious individuals being changed into self-confident young leaders.

4.2.3. Considerations of African identity

A third aspect of identity was that of African identity. The topic of “African Renaissance” on the Life Skills course encourages students to think about their African heritage, where the understanding of being African stretches beyond the borders of South Africa and involves embracing people from all African countries. Mandla’s assumptions were challenged by this. He says he was proud of being African, but explained how he and others used to use the derogatory word “makwerekwere” to refer to foreigners from other parts of Africa. Then, when confronted with the teaching during “African Renaissance” his mindset was challenged about what it means to be African, to have an African identity and who else should be included in that identity.

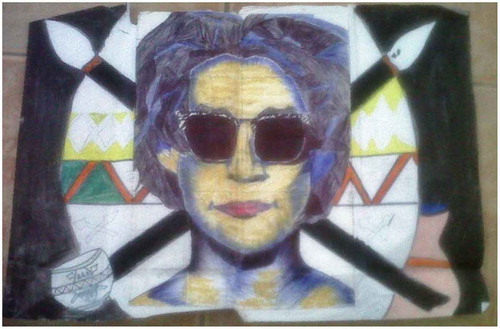

Nobhule creatively expressed “Being African” as an important aspect of identity in Figure . Her drawing is a representation of herself which described as follows:

In the background are two spears and a shield, weapons and symbols of her Zulu heritage and culture. The pot in the bottom left corner is like the one African women drink from, while the pot in the bottom right corner is like the one African men drink from.

Nobuhle said that no matter what she becomes, she must not forget where she has come from While she didn’t indicate what direction she wanted to take in her life, she identified that where she has come from (her African identity) is and must remain an integral part of where she is going to (her purpose). Clearly for Nobuhle, identity as a Zulu woman with its heritage is an integral part of who she is. However, there was also the sense of moving forward purposefully into new identities, while not forgetting past identities.

4.3. Reflection and changing mindsets

The study exposed multiple forms of reflection which WCA students engaged in. In many instances such reflections led to profound learning and alterations of mindsets.

Kosan, for instance, reflects in a very active way while he is teaching Leadership classes. Whatever message he is teaching, he evaluates whether his actions are matching what he is saying. Reflection takes place while he is in action. On the other hand, there are other instances when he takes time to be alone to reflect, and this is rather reflection on action.

Other participants indicated the need for time alone in quiet, for internal dialogue and critical reflection. Nothando made the most reference to these times, although Kosan and Mandla also identified quality time alone as being important to them. Nothando found these times particularly helpful as a way to work through some of the conflicting opinions and viewpoints she was confronted with to decide what was right for her.

The volunteerism component of the programme proved to be another opportunity for reflection. Many of the participants talked about how the volunteer phase had helped them to learn what they were good at, and through having the experience they were able to evaluate and learn about the workplace.

The design of the study allowed for other observations of reflection. This was during a creative participatory data collection session with Kosan, Mandla and Nothando, where they spent a few hours creating a collage as a picture of their lives. In the beginning, Kosan sat very quietly by himself and seemed deep in thought, whereas Mandla and Nothando chatted to each other from the start. Kosan started by making a greeting card for someone, before doing his collage. It was unrelated to the task given and was for another WCA staff member. He seemed to need time with his own thoughts and used creativity to get started and to reflect on his journey. He later identified the process of doing the collages as being helpful in recognising his appreciation for art. The earlier example of Kosan was of how he reflected while in action during teaching. In this case, he seemed to need to be busy with his hands, doing something creative and active, in order to reflect back on the process and journey he had been through on the WCA Programme.

On the WCA programme, teaching about relationships, attitudes, emotions, health, beliefs and work principles is in many cases different to what students have grown up believing or hearing. The WCA programme, therefore introduces students to different ways of thinking about life, encouraging them not to simply take things for granted. It is an environment in which critical reflection is encouraged by creating space for questioning and challenging of assumptions. This type of learning environment is fertile ground for challenge and conflict. However, within the conflict, discomfort and disagreement, a potential space for discussion and learning and changed mindsets also arises. When the participants were asked in what ways they thought they had changed, some of the responses indicated changes in mindset:

I’ve changed the way I think.

I didn’t know that decisions I made could affect my life going forward.

These quotes show that students gained insight into different ways of thinking. There were indications that some students were able to engage in critical reflection on issues, have their mindsets challenged and sometimes changed.

Mandla recognised that it was the choices his father had made regarding alcohol which had severely impacted his own life growing up. He realised that he didn’t have to follow the same pattern and that the decisions he made about his lifestyle, would affect his own children and family in the future. These reflections were influential in Mandla deciding to stop the destructive habit of alcohol abuse.

Nothando’s perspectives were challenged in the community service phase. She faced opposition from her family and friends for doing work for no pay, because it was a mindset which was foreign to them. Although she was introduced to the ideas and values of volunteerism, back in her home community her friends and family had not been exposed to these new ideas. Despite the opposition, Nothando had to try out the new perspective she had adopted, to see how it worked out for her. Acting on new understanding, which is contrary to the mindset of those closest to you, is perhaps one of the most challenging parts of the critical reflection process.

Kosan’s mindset about the world of work, which had been reinforced by his family was challenged and later changed. Previously, he knew he needed to look for a job, but had never thought about starting a business himself. After participating in the WCA Programme, he now sees being an entrepreneur as a possibility.

The Biblical worldview held by WCA as an organisation is different from the worldview held by of many of the WCA students who believe in ancestral worship. It was evident that this was a source of conflict and challenge for some students. One student said, “Things we are taught here (are) against what we learnt at home”.

Kosan and Nothando wrestled a lot with this issue before coming to the point of changing their beliefs and practices. They were introduced to new ideas, and needed to work out for themselves what they believed and how they wanted to lead their lives. They engaged in discussion with leaders at WCA and their own families, to interrogate why certain rituals and belief systems were held. They revised some of the assumptions they had grown up with and embraced a different belief system in some instances.

4.4. Community engagement, relationships and authenticity

Community engagement, close relationships and being authentic were found to be an influential factor in student learning and the actions which such learning shaped. Two communities in particular were a significant part of each student’s life. Firstly, there is the community in which the student lives (their home) and secondly there is the WCA community. The former is a community representing a sense of familiarity, home and belonging before they encountered WCA through the Life Skills course. Then, the WCA Programme introduced a new aspect of relationship to this community.

While on the residential leadership course, students live in community with other students and with WCA staff and leaders. Thereafter, for a six week period, they return to their homes during the community service phase of the course to do volunteer work. This part of the course is about “giving back” to this community although there are also personal benefits such as gaining work experience. While the “giving back” to the community might simply be a part of the course and something never considered again once the programme is over, the findings indicate otherwise. Some students do return to volunteer situations of their own accord after the programme. When Mandla completed the programme, he returned to doing volunteer work to keep himself productive and out of the lifestyle of drinking. A number of the students indicated their intentions to do volunteer work after the course. Whether or not they followed through with this plan is unknown, but the volunteer experience seems to have opened up their eyes to the value of doing volunteer work and gaining work experience while giving back to their communities.

A brief review of the purposes which Mandla, Nothando and Kosan established for their lives, also illustrates elements of “giving back” to the community as each of them has an outward, community-oriented focus. Mandla knows he is good at public speaking and wants to use this skill to motivate others. Nothando is studying to become a teacher, a people focused profession and one which requires an extensive outward focus. Kosan likes to see people develop and grow the way that he has and wants to be a part of the process of helping people in that process.

The outcome or results of change in many of the students point towards the development of an outward focus and a giving back to others and to their communities.

The second community which became part of the student’s lives was the WCA community. WCA became something of a “home away from home” to some of the students. A bond and a sense of belonging developed amongst the staff and students on campus. This community seems to represent one from which students receive a lot in terms of support, nurturing and friendship.

Participants said there was engagement between facilitators of the programme and the students after classes, most especially when there had been issues of conflict arising during class time. Positive and trusting relationships were reported to develop between students and facilitators. There seems to be significant nurturing within the programme, helping students face challenges and changes.

The value Mandla places on the relationships at WCA can be seen through one of the pictures he chose for his collage, namely, a large group of people smiling and waving. He explain his choice of picture:

This picture, symbolises us at World Changers – we are too many from different places, but we formed one organisation and we formed a friendship – that is what is happening here… they are all wearing different clothes, but if you look at them close, you see that there is a smile and I believe that there is a friendship there and there is unity.

Mandla learnt and grew through the affirmation and encouragement he received from others about his public-speaking skills. In isolation, he would not have had this feedback, illustrating the crucial role of contexts and community in learning.

Kosan offers another example of the importance of community. When growing up, he used to spend hours and days in isolation. Now he enjoys the WCA campus more when there are lots of students around than when there are none. He says it is too quiet without them, showing his enjoyment of relationship and community.

During the Leadership course, where students and facilitators all live on campus, share responsibilities and abide by organisational codes of conduct, an intense community experience is created. The environment and community seem to create the space for deep levels of trust and disclosure and for relationships to develop, and positively influence the changes the students go through.

The importance of community and authentic relationship emerged in the data as various participants spoke of the importance of leaders within the organisation being role-models who practiced what they preached. Kosan said he was influenced by the way the facilitators of the courses he did lived out their lives. Now that he is in a leadership role, he is very aware of his own actions and that what he says needs to match up with how he lives his life.

Kosan believes that one of the strengths of the WCA model is that facilitators on the courses are people from the same communities and backgrounds as the students. This enables the facilitators to relate to the same struggles and challenges the students have been through, and to encourage and motivate them. It also means that the students are able to look to them as role-models to evaluate the authenticity of their message and to see in a practical way how that is working out. This is what Nothando did, when she was considering different belief systems. Kosan had already made changes to his beliefs and stopped practices associated with ancestor worship. Nothando looked to see how Kosan’s changed actions were affecting his life. The role of relationships, in particular authentic relationships based on trust and integrity have been seen to be influential in the lives of the students.

The role of community seems to be bi-directional–the “getting from” or nurturing as well as the “giving back” to the community–clearly plays an integral part in student’s learning processes.

5. Implications for youth programmes in SA

The life-altering learning and transformations reported by WCA participants like Nobuhle, Kosan, Nothando, Mandla are inspiring and instructive. In a country facing serious challenges with large parts of its youth who are not in employment, education or training, many of whom have grown up with negative experiences and role models, these stories augur much hope. However, the programme which these youth have benefited from is not typical of what is on offer to youth in South Africa today. The current focus on preparing young people for the workplace is narrow and technicist and ignores the psycho-social rehabilitation and reorientations needed to address painful and limiting early socialisation and often trauma

This case study of the WCA programme has surfaced four important aspects of learning which seem to combine to provide life-altering change. This points to the need for programmes designed for more holistic development of youth and which:

| • | consider the role of emotional healing to address past issues and move forward with hopefulness; | ||||

| • | develop positive identity, confidence and purpose; | ||||

| • | foster critical reflection that can challenge and sometimes change previous mindsets; | ||||

| • | Contribute to community life, building of close, trusting relationships and valuing authenticity in order to receive from others in community. | ||||

This latter aspect of learning may well connect with traditional African values which valorized communal ways of life and interdependence. In essence this points to a form of education which pays greater attention to the context and histories of learners. It also points to the need for curricula, learning processes and learning environments which promote humanising education. Such an orientation to youth education stands in stark contrast to youth programmes premised on Human Capital Theory and the preparation of workers for the labour market. The fact that the South African economy has experienced growing unemployment, makes the need for broader and holistic development of youth more important and urgent.

Furthermore, the fostering of critical reflection seems key when working with youth who have been marginalised in society and who may have internalised experiences of oppression. Cooper (Citation2012) has pointed to the lack of criticality in youth work practice in England. Mainstream youth programmes in South Africa likewise lack such criticality. The kinds of socialisation many South African youth have experienced have shaped mindsets that could be limiting in the current context. Youth programmes must challenge and prompt critical reflection. This is also an important component of citizenship education in a democracy.

World Changers Academy has developed a model which appears to do the above and which address critical needs of youth from marginalised communities. The content and pedagogy of WCA programme seems to trigger powerful learning and transformations. Changes at the level of identity, confidence and purpose as reported above are not easy to attain. This is similar to the powerful learning described by Gervais (Citation2011) in the context of empowering workshops for girls in Bolivia where personal growth regarding self-esteem and self-respect are indicative of the transformative potential of human rights education that is delivered through supportive and encouraging approaches. Further explorations on how one can create such learning environments on scale are needed.

It would be important to explore how government, private sector and civil society organisations can bring this type of youth development to scale to benefit the large numbers of youth needing such programmes. If innovative youth programmes are only provided by NGOs like WCA, the large majority of youth will not benefit. It is important for all institutions working with youth to finds ways in which they can give attention to emotional healing, hopefulness, positive identity, critical reflection and the building trusting relationships and community, in their programmes. This needs to happen through formal programmes of schools, colleges and universities and through nonformal programmes of NGOs as well community, faith-based and sports organisations. The expanded post-school system of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges and Community Education and Training (CET) colleges in South Africa could be harnessed for such programmes. Getting youth to lead such programmes, as done in WCA, could build capacity to bring such learning to scale. Given the context and widespread need for such learning opportunities, the key challenge is to explore how educational programmes for youth could be structured with more humanising and holistic learning objectives.

6. Conclusion

Giving attention to the psycho-social demands of the transition from unemployed hopelessness to career-oriented hopefulness is very important if we are to address the challenges posed by millions of youth who remain on the margins of the economy and society. This should be a major consideration in all educational programmes for youth in South Africa.

The contribution that this study has been able to make to the design of programmes for youth has been the identification of the importance of emotions, healing and building hope; of developing of positive identities, confidence and purpose in students; of fostering critical reflection on mindsets and finally, prioritising the development of community-building orientations, positive relationships and authenticity. These lessons could help in the development of programmes for youth in South Africa and elsewhere.

Creating education, training and work experiences are important but not sufficient preparation for youth. Jonathan Jansen (Citation2014), former vice-chancellor of the University of Free State and critical education scholar, advised that, “A student who looks to our turbulent history in order to chart a path of healing and hope, rather than anger and retribution, is one who can create a different future out of that broken past”. When working with youth there is need for attention to healing, re-humanising and building of hope alongside more traditional work-readiness skills.

Funding

The authors received no direct funding for this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vaughn M. John

Vaughn M. John, PhD, is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. His research interests include adult learning, peace education and community development.

Amanda J. Cox

Amanda J. Cox, MEd, is a PhD candidate in the School of Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. Her primary research interests focus on adult learning for personal and professional development in a range of contexts.

References

- Bastien, A., & Holmarsdottir, H. B. (Eds.). (2015). Youth ‘At the Margins’: Critical perspectives and experiences of engaging youth in research worldwide. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Coetzee, M., & Esterhuizen, K. (2010). Psychological career resources and coping resources of the young unemployed African graduate: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(1), 868–876.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cooper, C. (2012). Imagining ‘radical’ youth work possibilities – challenging the ‘symbolic violence’ within the mainstream tradition in contemporary state-led youth work practice in England. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(1), 53–71.

- Cosser, M. (2010, August 2). Not a “NEET” solution to joblessness. Retrieved November 17, 2016, from Mail and Guardian: http://mg.co.za/article/2010-08-02-not-a-neet-solution-to-joblessness/

- Gervais, C. (2011). On their own and in their own words: Bolivian adolescent girls' empowerment through non-governmental human rights education. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(2), 197–217.

- Hazell, E. (2010). An evaluation of the World Changers Academys Leadership programme. Shongweni, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa ( Unpublished research report).

- Henning, E. (2004). Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

- Jansen, J. (2014). University: What is it and what is it not. Irawa Post, 70(1), 3. Retrieved March 15, 2016, from Irawa Post: https://issuu.com/irawa/docs/irawa_january_2014

- Mohomed, N. (2002). Transforming education and training in the post-apartheid period: Revisiting the education, training and labour market axis. In E. Motala & J. Pampalis (Eds.), The state, education and equity in post-apartheid South Africa (pp. 105–138). Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Momo, G. (2009). NGOs and social development: An assessment of the participant’s perceptions of the effects of World Changer’s Academy’s life skills education program, Ethekweni Municipality ( Unpublished Masters dissertation). University of Kwazulu-Natal.

- Reddy, N. (2014). The youth wage subsidy. In S. Vally & E. Motala (Eds.), Education economy and society (pp. 190–212). Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- Swartz, S., & Soudien, C. (2015). Developing young people's capacities to navigate adversity. In A. De Lannoy, S. Swartz, L. Lake, & C. Smith (Eds.), South African Child Gauge (pp. 92–97). Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

- Vally, S., & Motala, E. (2014). No one to blame but themselves: Rethinking the relationship between education, skills and employment. In S. Vally & E. Motala (Eds.), Education economy and society (pp. 1–25). Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- WCA. (2009). World Changers Academy: Empowering people to change the world. Retrieved March 12, 2011, from World Changers Academy: http://www.wca-sa.org/

- Wedekind, V. (2014). Going around in circles: Employability, responsiveness and the reform of the college sector. In S. Vally & E. Motala (Eds.), Education, economy and society (pp. 57–79). Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.