Abstract

The current study aims to interpret student-teachers’ PowerPoint presentations using concepts derived from jazz improvisation. The purpose of the study is to acquire insight on how knowledge is instantiated in action in a ubiquitous educational setting. If musical lead sheets depict the draft model that provides players with a framework for improvising, Power Point slides may be studied in terms of their properties as an improvisational framework. Works for performance vary in their constitutive properties, differing in terms of how much slack is left for the performer’s interpretation. The concepts of horizontal and vertical playing are adopted to study the performance of the student teachers’ PowerPoints slides. A vertical approach involves elaborating and expanding on the constituent parts of the slides, whereas a horizontal approach involves connecting the pre-formed elements into coherent linear phrases. The outcome of the study is a model with a double matrix that supports a reflection on how curricula are transformed by being pre-formed and performed. Since the model illustrates the students agentive re-shaping of curricula, the model is aligned with the essential teaching skills conceptualised as Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). In view of PCK, improvisation should be considered a skill that is required to mediate the transformation of the pre-formed during performance. Empirical data are collected by video recording music students’ presentations of music lessons planned for their practicum placement.

Public interest statement

This study is motivated by teachers who report that they improvise when they teach. The study puts PowerPoint-led teaching under scrutiny, investigating how student-teachers perform their PowerPoint slides. To focus the research, the concept of improvisation is borrowed from jazz music. In jazz, improvisation involves reworking pre-composed materials and designs. By analysing presentations, it appears that students who present also rework their own pre-composed designs as they talk through their slides. The study summarises its findings by presenting a model that shows how slides vary from being “thin” to “thick” in terms of content. The presenters’ performances of slides span between elaborating on the givens or by connecting the givens without adding information. The study concludes that improvisation can be considered a teaching skill that captures what students do when they transform and represent knowledge, both at the stage of pre-forming and performing.

By Øystein Kvinge

My assertion is that the key features that teaching should share with jazz music and theatrical improvisation, although it currently does not, is the availability of an explicitly held and deliberately taught body of knowledge about how to successfully improvise in order to accomplish the intended aims of the profession

1. Introduction

In the knowledge and information society of the twenty-first century, teaching with the visual support of presentation software, such as PowerPoint, Prezi and Keynote, has become a widespread format for producing and disseminating knowledge. A recent study revealed that 92% of lecturers at Bergen University in Norway utilise these tools in their teaching (Kjeldsen & Guribye, Citation2015). In a national survey conducted in 2014 across all institutions of higher education in Norway, 90% of the teacher staff and 56% of the students reported that they use presentation tools on a regular basis (Digital tilstand Citation2014/2015). Teacher education is not exempted from this practice, and student-teachers gain first-hand experience with the ubiquitous practice of presenting when they share the outcome of various subjects’ assignments with their peers. Thus, presentations have a double function: they are a format resorted to by teacher educators and student-teachers alike.

Previous research on the use of presentation software in educational settings has mainly addressed the use of PowerPoint, noting how the technology affects the dynamics of pedagogical settings and the general relationship between the presenter and students (Craig & Amernic, Citation2006), and even going so far to claim that receivers may become “passively engaged” and not “actively engaged” (Jones, Citation2003). PowerPoint elevates form over content (Tufte, Citation2003) because the templates exert a particular formatting to the presentations. Inevitably, the content becomes reduced to bullet points, which affects the tacit, mimetic and dialogic dimensions of the teaching–learning relationship (Adams, Citation2006). A strain of research investigated what design principles may help the presenter communicate more effectively. Students’ own preferences have been assessed as to what construction principles works best (Apperson, Laws, & Scepansky, Citation2008; Rockwell & Singleton, Citation2007). Based on the cognitive load theory (Sweller, Citation2011), it is argued that the design of PowerPoint slides should adhere to the principles of coherence and redundancy by avoiding extraneous information (Atkinson & Atkinson, Citation2004; Clark, Nguyen, & Sweller, Citation2011).

Recent studies on presentations in academic settings have applied a multimodal framework for the analysis of the practice (Jurado, Citation2015; Querol-Julián & Fortanet-Gómez, Citation2014; Rowley-Jolivet & Carter-Thomas, Citation2005; Zhao, Djonov, & van Leeuwen, Citation2014). Affiliated with the linguistic research on language in use, these studies are based on an understanding that during presentations, meaning is made through the interplay of multiple semiotic resources or modes, not by speech or text alone. Here, modes constitute resources for making meaning (Kress, Citation2010), and they are deployed concurrently during presentations, that is, the speaker elaborates through the modes of speech on information presented on screen through the modes of image and text. Taking the stance that meaning occurs in the context of signs mediated by technology and embodied action, the presenter is attended to as a sign maker (Camiciottoli & Fortanet-Gómez, Citation2015).

By adopting a multimodal approach to examine presentations, the current study aims to contribute a new understanding of the epistemology of teaching as it is conducted in teacher education in the twenty-first century. Presenting entails giving curricular items a shape and form for representation across a series of slides. Ideally, the design is adapted to the target audience’s prior knowledge. Therefore, the presentation draws on the teaching skills of curricular transformation and curricular representation that constitute a part of the concept of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) (Shulman, Citation1986, Citation1987). PCK is a construct that describes the essential skills particular to the teaching profession. However, the transformation and representation of curricula are not completed by merely designing the slides; this process becomes completed in action as the presenter interacts with the elements on the slides i.e. by elaborating on the content and providing examples. Researching presentations, thus, provides an opportunity to study PCK as it unfolds in teacher education by “discovering and describing how knowledge is implemented and instantiated in practice” and by studying “(…) how the act of doing influences the nature of knowledge itself” (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006, p. 23).

Based on the empirical data derived from music student-teachers’ presentations of compulsory assignments for their peers, the current study proposes a model that describes the dynamic interplay that occurs during presentations between the presenter and the digital representation of curricula featured on the slides. Acknowledging that presentations encompass the articulation of knowledge in action, the present study utilises theoretical perspectives from the performing arts as analytical tools. In particular, the concept of improvisation is applied as an analytical lens because the ability to improvise resides in the tension between the pre-formed and the performed.

1.1. Performing the pre-formed

The act of presenting can be likened to that of a performance. Performance theorists have agreed that “all performance is based upon some pre-existing model, script or pattern of action” (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 12), and there is no performance without pre-formance (MacAloon, Citation1984). The student-teachers observed in the current study transformed curricular items by turning them into a pre-formed (Van Leeuwen, Citation2016) representation of the current topic in terms of text and images on a set of slides; these are performed during the presentation. The performance aspect is also a result of knowledge communication being decontextualised by the mediation technologies (Knoblauch, Citation2008). Thus, this type of performance is inescapably influenced and governed by the pre-formed because the pre-formed designs of the PowerPoint slides are drafts by their very nature and require someone to perform them to form them into some sort of coherent meaning.

The use of metaphors in exploring a domain for research may reveal connections that otherwise might not be seen. Using jazz improvisation as the root metaphor (Pepper, Citation1942) can enable the researcher to use a concept as a heuristic device to assist in understanding a different field (Black, Citation1962). A standard notation format for music within the jazz community is the lead sheet. The current study views the lead sheet as a pre-formed element that guides a jazz musician’s improvised performance. By acknowledging the “draft” nature of the constituent parts of lead sheets, concepts from a musical domain can be ported to the context of education by force of metaphor: similarly, the PowerPoint slides are draft designs. Contrary to scores for classical music, the lead sheets are sparse in terms of how much musical information is represented. These provide “the bare bone-bones musical information—melody, chords and form—that you need to play a tune” (Baerman, Citation2004, p. 20). This musical framework leaves a substantial space for the performer(s) to interpret and rework the musical material. Lead sheets depict “the kind of skeletal model that typically provides players with a framework for improvising” (Berliner, Citation1994, p. 507). However, the free space is not limitless because “with a lead sheet, players are in a genuine sense “tied to” the “score”—that is, they must agree to submit to the “givens” of the piece and respond accordingly” (Nielsen, Citation2015, p.5).

The notions of “thick” and “thin” works are used by the philosopher Stephen Davies to describe musical works’ constitutive properties (Davies, Citation2001). “Thin works” are characterised as featuring few determinative properties compared to their counterpart, “thick” works. Pieces that are represented as lead sheets, and thus only provide the melody, chords and form, can be considered thin works. An important observation is that the thinner the work is, the freer the performer is “to control aspects of the performance” (Davies, Citation2001, p. 20). Consequently, pertaining to the performance of thin works, most qualities of the performance should be ascribed to the performer’s interpretation, not to the work.

Building on the notion that jazz improvisation is guided by the pre-formed constituent properties of “lead sheets”, in the current study, jazz will be utilised as a toolbox that supplies the theoretical devices for studying student-teachers’ performances of the pre-formed curricula. Hence, the research question is as follows:

How does improvisation materialise in the interplay between the pre-formed curricula and the performer in student-led PowerPoint presentations in teacher education?

1.2. Improvisation—Reworking the pre-composed

The epistemological motivation for researching improvisation as a professional skill can be found in prior debates on what constitutes professional knowledge. An important contribution to the debate is Schön’s critique of the prevailing view of the time that competent practice is the “application of knowledge to instrumental decisions” (Schön, Citation1992, p. 9). Schön questioned the ability of theoretical knowledge to capture the “indeterminate zones of practice” and hence called for a view of professional practice as a reflection exercised in and on action. The tacit dimension of practice may be referred to as “art” (Eisner & Reinharz, Citation1984) or “professional artistry” (Kinsella, Citation2010) because the conception of art contrasts with the positivistic view on practice as guided by theory. “Pedagogical tact” (Van Manen, Citation1986) is in its very practice a kind of knowing; it captures the teachers’ ability to know instantly how to deal with the interactive teaching–learning situations. Montuori (Citation2003) brought the concept of improvisation into the discussion on professional practice using the term as a musical metaphor to “bring in all the elements from the arts that were successfully avoided by the social sciences” (Montuori, Citation2003, p. 239).

The Latin root of improvisation is improvisus, or unforeseen or unprepared. In his landmark book Thinking in Jazz, ethno-musicologist Paul Berliner (Citation1994) claimed that the popular conception of improvisation as “performance without previous preparation” is fundamentally misleading; he revealed there is “a lifetime of preparation and knowledge behind every idea that an improviser performs” (Berliner, Citation1994, p. 17). Berliner’s definition of improvisation in jazz music is as follows:

Improvisation involves reworking pre-composed material and designs in relation to unanticipated ideas conceived, shaped and transformed under the special conditions of performance, thereby adding unique features to every creation. (Citation1994, p. 241)

A close reading of educational researchers Beghetto and Kaufman’s (Citation2011) definition reveals that they modified Berliner’s wording to fit in the domain of education. Their interpretation of improvisation may serve as an example of how other researchers also have looked at the performing arts and borrowed analytical concepts from this realm to explore the domain of education. Beghetto and Kaufman (Citation2011) identified curricula as the material subject to transformation across two stages—as-planned and as-lived:

Disciplined improvisation in teaching for creativity involves reworking the curriculum-as- planned in relation to unanticipated ideas conceived, shaped and transformed under the special conditions of the curriculum-as-lived, thereby adding unique or fluid features to the learning of academic subject matter (p. 96).

The current study departs from the common denominators shared by the above definitions of improvisation. By analysing these definitions, it becomes clear that the concept of improvisation encompasses elements and processes that must be operationalised in the current study to make the concept work as a utility for researching the practice of presentation. First, the current study identifies the PowerPoint slides created by student-teachers as “pre-composed materials and designs”. These can be examined according to their constituent properties and considered “lead sheets” around which the processual aspects of presentation revolves. In this regard, the definitions of improvisation convey “re-working” as the process that unfolds during performance. Then, the current study must apply methods for identifying and describing the processes of reworking the curricular designs, which is expected to take place in the observed settings where student-teachers perform their PowerPoint slides. If this happens, the research question can be responded to in terms of how improvisation materialises in the interplay between the pre-formed curricula and the student performer. In the following section, the methodological approach will be outlined in more detail.

2. Method

The present study was organised around a compulsory assignment in music pedagogy that was given to a group of 18 first-year music student-teachers at a Norwegian teacher training college. The student-teachers were required to work individually or in groups of two to three to make plans for a music lesson that they would later carry out during practicum placement in a primary school. The aim of their lesson would be to teach a song of their choice to a group of pupils. Using the didactic relation model (Bjørndal, Citation1978) and core texts on music pedagogy from the syllabus, student-teachers were asked to write an assignment on their own reflections on the didactic aspects of teaching this song to their target group. This assignment would later be converted to PowerPoint slides and presented by the student-teachers to their peers under supervision of their subject teacher. All the student-teacher presentations were subject to video observations and constituted the empirical material of the current study.

The total number of presentations was 12, and each presentation spanned from six to eight slides. The total number of slides presented was 75. The average duration of a presentation was 8:45 min. A single HD camera was positioned at the back of the classroom to capture the student-teachers’ actions, speech and projected PowerPoint slides. During the presentations, field notes were made using an observation template, and emerging issues were addressed in a full class subsequently after each session.

The current study was designed to be an instrumental case study (Stake, Citation1995). The instrumental case study is an appropriate tool because it facilitates an understanding of a particular phenomenon other than the case itself. In the present study, the cases comprise several presentations performed by music student-teachers; however, the phenomena external to the situations is that of improvisation, which in the current context is perceived of as a skill that is manifested in the student-teachers’ design and reworking of the PowerPoint slides. In instrumental case study research, the focus of the study is more likely to be known in advance and then designed around an established theory or methods. The case is of secondary interest: it plays a supportive role, and it facilitates our understanding of something else (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). Importing the concepts derived from jazz improvisation provides a theoretical framework that helps conceptualise the phenomena under scrutiny. It is common for instrumental case studies to “test existing theory in a real site” (Mills, Durepos, & Wiebe, Citation2010), and the use of an instrumental case may, as demonstrated by the current study, facilitate the development and demonstrate the applicability of the existing theory in a different domain than where it originated.

The instrumental case study approach does not attempt to draw on a statistical defence of the claims of regularity. At the heart of the approach is the concern for local, situated evidence of the relevance of the analysis (Heath, Hindmarsh, & Luff, Citation2010). The aim of analysing situated, social activity is usually related to how participants make meaning in naturally occurring interactions where information about the setting, manipulation of objects, body language and so forth may need to be integral to transcription (Lancaster, Hauck, Hampel, & Flewitt, Citation2013). The collected video material was transcribed using the HyperTranscribe software (Hesse-Biber, Kinder, & Dupuis, Citation2009). Primarily, the spoken words of the presenters were attended to and transcribed to text in their entirety. The text components of the accompanying slides were transcribed and included as separate text sections in the transcripts, demarcated by brackets to separate the units from the spoken words. Images were represented in the transcripts by text snippets that describe the content of the image.

The transcribed files were imported into the HyperResearch software for coding, categorisation, review and annotation. A priori codes derived from the multimodal theory were first applied to segments to capture the various kinds of organising principles that pertain to the pre-formed slides as separate entities and between the pre-formed slides and the performer during the presentation. In the next iteration, codes were grouped according to common features and categorised in abstract terms. The latter representation of the data formed the basis on which an evaluation of candidate concepts from within the jazz theory could be made.

3. Analytical framework

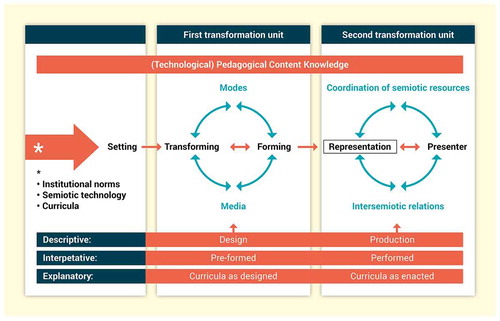

To support the analysis of the data from the field, the current study adopted the learning design sequence (LDS) (Figure ) as an analytical framework (Selander, Citation2008, Citation2017; Selander & Kress, Citation2010). This model was selected because it reflects the properties of improvisation, as discussed above, in that it conceptualises the elements and processes of the pre-formed and performance. The LDS may be conceived of as a theoretical map that identifies the learner’s activities at the level of sign-making. Thus, the model aligns the current study with the branch of studies on PowerPoint that are grounded in a multimodal social semiotic approach:

A basic assumption of social semiotics is that “meanings derive from social action and interaction using semiotic resources as tools”. It stresses the agency of sign makers, focusing on modes and their affordances, as well as the social uses and needs they serve.

Figure 1. The learning design sequence, amended (Kvinge, Citation2018)

A key aspect of social semiotics is that sign-making, and thereby the acts of meaning making, is a motivated activity. Essential is the notion that the sign-maker, guided by his or her interest, selects from the available resources to make an apt representation—or sign—of the aspect of the world that is in focus at the moment. In an educational context, the sign-making activity is thought to be pedagogically motivated. In semiotic terms, communication is about selecting the most apt signifier for the signified. And signs, which are the expression side of meaning, are thought to be continuously remade according to the need of the person acting. Signs are not a stable entity; rather, the social semiotic approach sees a sign as being invented by the acting person because of the needs of the given situation in the given social setting.

Multimodal research attends to the interplay between modes to look at the specific work of each mode and how each mode interacts with and contributes to the others in the multimodal ensemble. In the current setting, this multimodal cohesion occurs across meaning-making devices within the pre-formed slide and between the pre-formed slides and the presenter during a performance.

In the settings observed in the current study, the student-teachers engaged with the assignment in two stages that correspond to the first and second transformation units of the learning design sequence. In the first unit, the learner directed his or her transformative engagement towards the reflexive written assignment that they had completed individually or by work in groups. Available were the semiotic resources afforded by the software (PowerPoint), that is, text, fonts, images and colours, which allowed the student-teachers to convert their written text into a multimodal representation. In material terms, the outcome of the first cycle was a PowerPoint slideshow, and this is what is referred to as a representation in the LDS-model and a lead sheet according to the jazz metaphor. The first transformation unit maps the part of the process where the representation is pre-formed.

The second unit of the LDS-model maps the stage in the process where the presenter performed the pre-formed. The settings that were observed and video recorded for the current study were numerous instances of the second transformation unit. This unit made up settings where knowledge could be instantiated in action by being performed by a presenter. Although the transformation of curricula now takes place in real time, the presenter’s agency and interest were also considered to be guiding the transformative processes across the modes available in the situation. The researcher’s focus was directed towards the multimodal interplay that occurred between the pre-formed semiotic artefact, referred to as a representation in the LDS, and the student-teacher’s actions, such as speech and gesture.

By attending to the multimodal composition of the slides and the multimodal interaction between the performer and pre-formed, the stage was set to analyse the elements and processes observed using the concepts derived from jazz. By doing so, the research question could be answered: how improvisation materialises in the interplay between the presenter and the representation of curricula. In the following section, the two transformation units of the LDS will be placed under closer scrutiny by testing the appropriate concepts from the art of jazz improvisation as analytical devices.

3.1. Analysis: Pre-formed Slides

To approach the PowerPoint slides as “lead sheets”, two contrasting samples will be discussed in the following section. The two samples were selected because they are representative of the variation width (Yin, Citation2003, Citation2012) in the data material in terms of how much pre-composed materials were featured on the slides. Considered as “lead sheets”, they differ in their configuration because the “givens” vary from being sparse on the one hand and more towards being fully articulated texts on the other. This observation suggests that pre-formed PowerPoint slides may be positioned along an axis spanning from “thin” to “thick”, depending on how much space they leave for the presenter’s interpretation.

3.1.1. A thin work

Contextually, the sample slide below (Figure ) is captured from the introduction part of a presentation made by a music student-teacher, and it provides an overview of the content of the lesson he planned for his practicum placement. His lesson was based on using the tune “La ti do re” as a warm-up exercise for the primary school students. The tune is based on the Sol-fa-principle, where the syllables of the text correspond to the pitch. The slide was displayed for his peers during his explanation of the Sol-fa-principle and how he intended to introduce the tune to his pupils.

Design wise, the slide is based on a template off the PowerPoint software. Wave shapes divide the screen vertically between superordinate elements, such as the main headline and subordinate content elements. The main heading is centre aligned. The text elements are featured in a bulleted list, aligned left, consisting of five list items that are keywords. In terms of cohesion, the spatial organisation of the elements suggests that the keywords belong together and that they refer to various aspects of the main headline. Figure represents a form in terms of how the elements that are subject to being performed—the list items—are placed in a certain order. The content is reduced to a “bare-bones” state in that the list items feature a bare minimum: just the keywords. In terms of its properties as a “lead sheet”, the heading is given similar prominence as the title of a tune, hinting at what the work thematically is focused on. Despite its sparse inherent information load, the layout suggests cohesive ties between the heading and the constitutive elements of the list items. As a piece of a work subject to performance, the slide can be characterised as “thin” in that the content, being keywords, do not fully articulate meaning and leave the presenter with the challenge of interpreting and articulating the keywords’ meaning during the performance of the slide.

3.1.2. Thick work

The context of the next sample is a student-teacher’s presentation of a generic plan for instructing a musical learning process to a group of primary school pupils. Her presentation began with the slide below (Figure ), which introduces the concept of curricular aims on various levels as an organising principle for a teacher’s work. Throughout her presentation, she broke down the principle of the aim as an overarching idea down to how it determines her own planning of the lesson to be conducted in practicum.

Figure is not based on a design template. It features ordered text elements on a white background. The heading stands out because of its heavier weight in terms of font size. The main text elements are organised as three bulleted list items. The first list item is a sentence fragment that establishes a cohesive tie to the heading, elaborating on it. The second list item elaborates on the first list item by providing further specification. A nested list item, in terms of a sentence fragment, further elaborates on the second list item. The final bulleted item is a quotation from a textbook from the syllabus for the music student-teachers’ education.

Inherent cohesion exists among the list items by means of how each element elaborates on the one above by further specifying or extending on the meaning’s potential. The inherent logic of the list items can be considered nested in terms of how they support the item above by elaborating or extending on its meaning.

In terms of being a lead sheet, the heading may be perceived of as the title of a work. It introduces the overall theme, or “aim”, that then becomes gradually more elaborated on throughout the form. The structure of Figure is organised using a bulleted list. The list provides the slide with a form, which suggests the order in which the items should be addressed by a performer. The internal cohesion supports this view in that the cohesive ties in terms of elaboration move from the general headline, which states the topic, to the specifics of the quotation from the syllabus at the bottom of the slide. The “givens” of this slide contrast those of the previous sample (Figure ) in that the list items are more elaborate and self-contained in terms of their expression of meaning. The sentence fragments articulate meaning more specifically than the keywords do, as does the quotation from the syllabus to an even greater extent. Therefore, the slide suggests the existence of a “thick” work in terms of PowerPoint slides that have cohesive and more articulated determinative properties.

3.2. Lead sheets performed—Horizontal and vertical approaches

Having analysed aspects of the pre-formed slides in terms of their properties as “lead sheets”, the next step is to identify what concepts derived from jazz may pertain to the stage of performance. Berliner explained that “Performers are also sensitive to the relationship between the constituent elements of the phrase and their harmonic backgrounds” (Citation1994, p. 250); this suggests that there is a relationship between the melodic invention of the jazz improviser and the underlying harmonies that constitute an important part of the “givens” of the lead sheet. Researching improvisation in educational settings, therefore, requires the researcher to attend to the interplay between the presenter’s utterances and the elements of the digital representation of the curricula.

Method accounts on jazz improvisation within musicology refer to the terms horizontal playing and vertical playing, which capture two approaches to improvisation that both relate to the underlying lead sheet; however, they do so in different manners. A vertical approach to performing jazz tunes is based on the underlying chord schedule by “relating to each chord change as it passes” (Longo, Citation1992, as cited in Holbrook, Citation2008, p. 3). The soloist’s musical material articulates the chords or the base chord’s remote extensions and alterations using the pitches derived from the chord for melodic invention. A horizontal approach is less concerned with describing each chord and incorporating the chord changes in the formulation of melodies, though it does rely on chord progression as a general rule (Berliner, Citation1994, p. 128). Amadie and Christensen (Citation1990) explained the distinction between the two approaches as improvisation based on chords and improvisation based on scales, where a scale-based approach is equivalent to horizontal playing. A simple explanation of the horizontal approach would be “superimposing a scale or mode over an entire chord progression” (Berliner, Citation1994, p. 128). In the following, this relationship between the pre-formed and the performed is transferred from the domain of jazz improvisation to the practice of presenting. The terms “vertical” and “horizontal” approach will be tested as analytical devices that can describe the performance of slides by applying the terms to samples that match the characteristics of “thick” and “thin” works.

3.2.1. Ex. 1–Vertical approach to performing a “thin work”

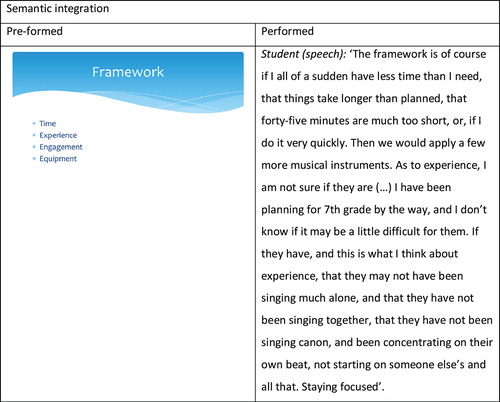

The context of the next sample is a student-teacher’s explanation of his planned music lesson. In the slide, he gives an account of how external factors might impact his plans. His analysis of what constitutes external factors is a step towards integrating the principles of the didactic relations model (Bjørndal, Citation1978) into his planning. The student-teacher engages with the curricula of teacher education by making a qualified assessment of what local terms and conditions might impact his own teaching during his practicum placement.

The student-teacher’s slide (Figure ) contains a headline and one bulleted list. The template emphasises the division between the title and content of the page using a graphical shape and colour to set them apart. The title and the four list items are single keywords, which leave a large space for the performer’s interpretations. There is a semantic link between the headline and the list items in that the keywords detail the topic introduced by the headline. A form in terms of the order of the elements is indicated by the list itself. The slide is considered “thin” because the determinate properties are few and not fully articulated; hence, there is space remaining for the performer to interpret the lead sheet.

The student-teacher performed the list items of the slide one by one. “Time” was elaborated on by providing several examples of scenarios that might occur in practice. Coping strategies in the case of too much time were also mentioned. The elaboration made by the student-teacher moved beyond what is suggested by the keywords alone. It is therefore relevant to draw a parallel between the concept of vertical improvisation and the way of extending the meaning’s potential of the “givens” of a PowerPoint slide. In this case, the student-teacher related to the underlying material by outlining the elements one by one and elaborating on what the list items might mean in a given setting. Likewise, jazz soloists who apply a vertical approach move beyond the “givens” of the chord symbols of the lead sheet, which by convention is represented in its most basic form, and outline the harmony by creating melodic material derived from the chord’s extensions and its alterations. The sample in Figure exemplifies a vertical approach to performing a thin work.

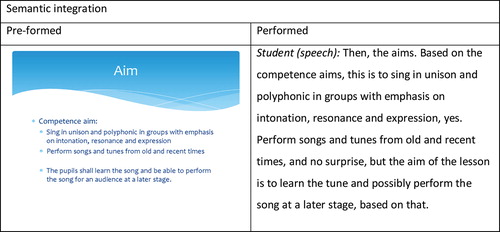

3.2.2. Ex 2–Vertical approach to performing a “thick work”

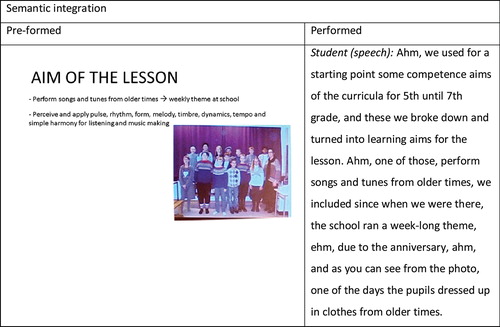

The context of the next sample is a music student-teacher’s presentation of her plans for a lesson on teaching pupils older songs. Because the student-teacher’s practicum placement coincided with a school anniversary, the choice of the musical theme was influenced by the local circumstances.

The sample slide below (Figure ) features a headline that states its topic. Two bullet points follow, and a colour image aligned to the right extends the last sentence. There is cohesion between the heading and the two bulleted items. The heading states the topic—“Aim of the Lesson”—and the two sentences appear to formulate the aims by further specifying what those aims are. There is no reference that states where the formulation of the aims is taken from or if they are quotations of curricula or student-made formulations. The order of the elements indicates that the second element elaborates on what is expressed in the first one. The image depicts a group of pupils wearing vintage clothes. There is no caption for the image that would help linking the motif of the photo to the text, but the reference to “older times”, as expressed in the first list item, becomes more specific in terms of the image, which displays the enactment of “old times” in the local context of the school classroom.

The slide is comparatively more self-explained than the “thin” slide referred to above; its content is more articulated, and its meaning is expressed across several modes, such as text, photo and layout. The slide in Figure serves as an example of “thick” work.

The performance of this “thick” work was vertically oriented, that is, towards the “givens” and by elaborating on these “givens”. The opening phrase extended the meaning of the content of the slide by specifying that the aims are formulations that come from the national curriculum. Thus, the speech provided the reference for the aims formulated on the slide, which now can be understood as quotations of external sources. Furthermore, an explanation was provided as to why the curricular aims were selected. The photo was commented on, and the comment anchored (Barthes, Citation2003) the photo in the context by emphasising what aspects of the image to attend to; it is the clothing that is of interest and that contributes to expanding the scope of the student-teacher’s account on the experiences from practicum.

The performance complied with a vertical approach, yet this time, it was based on a “thick” work. Although the “givens” of the slide were comparatively elaborated on, the speech contributed important contextual information that extended the overall meaning potential of the components of the slide.

3.2.3. Ex. 3–Horizontal approach to performing a “thin work”

The sample below is the introductory slide performed by a student-teacher who planned a music lesson for her practicum placement and who aimed at teaching her pupils a more popular song. The slide serves as an overview that addresses parts of the local and external conditions that could impact her planned lesson.

No layout from the available PowerPoint templates was applied to her slides. The main items are a headline on white background and a bulleted list that suggest a form, determining in what order to address the elements. The headline is generic in that it does not address the specifics of the student-teacher’s assignment. The headline does not immediately connect semantically with the five items on the list; however, the topics suggested by the list items indicate that what is represented are the local conditions for the planned lesson. The list elements are keywords, sentence fragments and sentences, leaving room for interpretation. The bottom two items are sentences that express meaning on their own. The draft character and the short-hand writing of the constituent parts indicate that the sample below can be considered “thin” (Figure ).

The performance of the slide differed from the previous sample. Most notably, the performance was characterised by linking together the “givens” already present on the slide into a coherent whole, as opposed to elaborating and extending on the potential meaning of the items. The student initiated the spoken phrase by establishing the slide as “her starting point”. The information then became contextualised in the local, which was the host school for her practicum placement. What followed were the list items linked together by speech but with one exception: the title of the song was not “given” on the pre-formed slide. The performance resembled that of a jazz improviser’s horizontal approach in that it oriented towards creating a coherent “line” by linking together and, thus superimposing, the “givens” along the temporal dimension. A vertical approach was not applied because there was little “going beyond the givens” by elaborating or extending on the meaning potential of the list items. Hence, the slide represents a horizontal approach to performing a thin slide.

3.2.4. Ex 4.–Horizontal approach to performing a “thick work”

The final example captures how a student-teacher gave an account of the aim of his planned music lesson. According to the didactic relation model, the “aim” was a specific category that the music student-teachers should address when planning their lessons. In the slide, the aims are formulated as references to the general guidelines of the national curricula, and these general aims should be reflected by the concrete learning activities devised by students as they carry out the planning of their own lessons.

The sample below (Figure ) is based on a design template from the PowerPoint software. Wave shapes contribute to dividing the screen vertically between superordinate elements, such as the main headline and the subordinate content elements. The main heading is aligned in the centre and reads “Aim”, which in turn is more general compared to the more elaborate “Aim of the Lesson” in the previous example. The content elements are featured as three sentences organised in a bulleted list that are aligned to the left. A separate list headline applies for all three subsequent list items in that they are all indented; however, the third is separated from the rest by an extra line space. Therefore, the final list element is ambiguous as to whether it belongs to the main list or if it is a separate entity.

In terms of cohesion, the list items can be interpreted as an elaboration of the headline: the main headline “Aim” is further specified by the list headline that reads “Competence aim”. The list items may be read as detailing what the competence aims of the national curricula are. However, the last item on the list, which is separated from the rest by an extra line space, remains ambiguous in that it may either be taken as a general principle, one responding to the headline, or taken as a formulation of the aim of the concrete lesson that was explained by the student. This slide may be labelled “thick” in that it features elements that articulate meaning on their own with, to some extent, cohesive ties among them.

The performance of the slide followed the order of the content elements and abided to the inherent form of the slide. Beginning with a conjunction, the student-teacher glued the “given” elements of the slide together by pronouncing what was written. There was minimal elaboration on the elements, the only instance being the specification expressed as “no surprise but, the aim of the lesson is”, which contributed to tying the final list item to the local context, thus separating the element from the two above, which referred to the competence aims expressed in the curricula. The performance of the sample represented a horizontal approach to a “thick” piece of work. The determinative properties of the slides were foregrounded and given a linear verbal representation, with few alterations contributed by the performer. There was no going in-depth beyond the givens, which characterises a horizontal approach.

4. Discussion

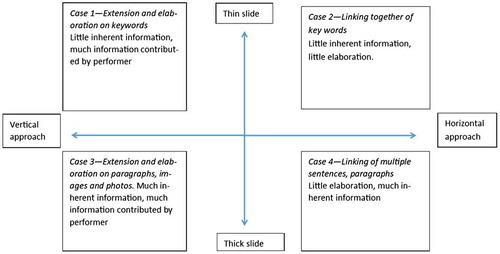

The analysis of the samples above indicates that a student-teacher’s presentation can be positioned in a matrix consisting of two crossing continuums. The pre-formed slides reside between “thin” and “thick” works. “Thin” slides feature few determinative elements, and those elements that are present are not fully articulated in terms of their self-contained expression of meaning. “Thick” slides feature self-contained entities, such as sentences and paragraphs that may be quotations or originate from the student-teacher’s own text production. A second matrix reflects a span between the “vertical” and “horizontal”, which captures the student-teacher’s approach to articulating the constituent elements of the slide as these are performed. A vertical approach addresses the elements of the slides in terms of elaborating and extending on their potential meaning one by one. This is equivalent to the “chordal approach” that develops musical material by going beyond what is “given” by augmenting and altering the harmonic foundations of a jazz lead sheet. On the opposite end resides the horizontal approach, which attends to the linear articulation of the givens, or the pre-formed elements on the slides. This resembles the melodic approach to jazz improvisation, which pays less attention to going in-depth beyond the givens, but rather invents coherent lines stretching across several bars. These observations are summarised in the following matrix:

The double matrix should be regarded as a theoretical construct that can capture what improvisation entails in the current setting. The theoretical construct operationalises, here in an educational context, what may be considered key aspects of improvisation, as defined by Berliner (Citation1994) and echoed by educational researchers Beghetto and Kaufman (Citation2011): that of “re-working pre-composed materials and designs”, which in the current setting are represented by “thick” and “thin” slides. A “horizontal” or “vertical” approach captures how “ideas conceived, shaped and transformed under the special conditions of performance” (Berliner, Citation1994), which are the student-teacher’ verbal expressions, relate to the pre-formed slides. The research question asks how improvisation materialises in the multimodal interplay between the pre-formed and the performer. The question was formulated to capture the primary features of disciplined improvisation, an informed activity that takes place within structures, which in the current setting are the curricular items featured in the pre-formed PowerPoint slides.

The current project is grounded in a discussion of the nature of student-teachers’ professional knowledge as it unfolds in teacher education in the twenty-first century. The dichotomy between seeing professional knowledge as the instrumental application of scientific knowledge on practice on the one hand and the metaphorical use of artistry on the other constitutes a backdrop towards which this project should be understood. The current study sought to find a middle ground between the two contrasting views by applying theoretical concepts derived from jazz improvisation to understand the aspects of presentations practiced in teacher education. Theorising improvisation constitutes a middle ground because it envisages the possibility of applying propositional knowledge, which is developed within the arts, on a knowledge practice that is liable to escape the articulation of its nature in propositional terms. The research effort should be regarded as an attempt to meet the need for developing a body of knowledge “about how to successfully improvise in order to accomplish the intended aims of the profession” (Dezutter, Citation2011, p. 29).

The design of the present study does not support making inferences as to what design and performance principles are the more efficient for learning and instruction. However, the double matrix may be aligned to the findings advocated by other studies on PowerPoint. A vertical performance of a thick slide may, in principle, conflict with the coherence principle (Clark et al., Citation2011), which encourages the exclusion of extraneous material. In practice, one should cut text on screen that will be narrated. In this sense, thin slides are favoured over thick slides, provided the presenter applies a vertical approach and goes beyond the givens of the slide. Such views are based on a cognitive approach to presentations that assumes that there are limits to how much information can be processed by the receiver at one time.

The outcome of the current study may inform the practices that take place in teacher education, wherein student-teachers present various topics for each other. The present study sees a presentation as a way of operationalising the concept of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). At the core of PCK are the core teaching skills of transformation and representation, both of which become activated as the student-teacher engages with the topic at hand when preparing it for presentation. The current study argues that the imported concept of improvisation is a factor that mediates the transition of turning the pre-formed into performance. Improvisation is the mediating activity on part of the student-teacher that negotiates the space between the pre-formed and the performed. The present study does advocate a view that a presentation may be considered an exercise where the curricular theory of teacher education is turned into practice; PCK is a skill that in the current context resides in the tension between the pre-formed and the performed because both are stages of transforming curricula into multimodal representations.

Then, what is the connection between presenting and teaching? The settings observed were selected for scrutiny because they represent a widespread mode of disseminating knowledge in teacher education and beyond. Still, the practice can be identified as belonging to the paradigm that sees teaching as a transmission of knowledge, a view that currently is being surpassed by a constructivist view of knowledge. In a similar vein, the practice observed can be understood as a method for student-teachers to construe their professional knowledge in terms of understanding teaching as a practice of representation. To a large extent, education relies on a representational epistemology (Osberg & Biesta, Citation2003) that is illustrated by the analysed samples above. The student-teachers’ own experiences from practicum and the concepts and ideas from the curricula of teacher education are turned into representations by the student-teachers’ own design of PowerPoint slides and in the subsequent performance of these.

A recent study (Kvinge, Citation2018) dealt in-depth with the student-teachers’ own representations of the teaching profession itself, as exemplified by their own reflexions on their experiences from practicum placement. Thereby, the student-teachers constructed their versions of what may be considered a teacher’s professional knowledge. The current study, however, shows that to represent the “aspects of the world” by means of a presentation is subject to the fluid logics of improvisation. Thereby, the representation cannot, from an epistemological point of view, be understood as one-to-one reflection of the real world it claims to be a reference of. Rather, the findings adhere to a constructivist view of knowledge, whereby student-teachers’ own presentations should be considered their agentive design of a version of “reality”, whether this reality is a curricular entity, such as a declaration of an aim for teaching outcome, or the student-teacher’s own recollections and analysis of experiences from a recent practicum placement.

The validity of the current study’s findings depends on whether the double matrix (Figure ) can be considered as representing what it claims to be a model of. The current study is based on the observation of indicators thought to represent the phenomena of improvisation as conceived of by studying the application of improvisation in jazz. Through the process of analysis, a construct in terms of a double matrix is established to represent the findings of the research effort. Inferences have been made that the indicators observed in the field correspond with certain properties of improvisation, ones adopted from jazz. Based on these inferences, a theoretical construct has been visualised in the form of a model. Although a model has been constructed, the theoretical validity of it, according to Maxwell, is conditioned by the “… validity of the blocks from which the researcher builds a model, as these are applied to the setting or phenomenon studied” and “… to the validity of the way the blocks are put together, as a theory of this setting or phenomenon” (Maxwell, Citation1992, p. 291). In this case, the “blocks” are the theoretical devices borrowed from the domain of musical performances. These are borrowed because they, as metaphors, both capture the properties of the structures and frameworks presented in the current study and the different approaches to reworking the predesigned elements. Transparency, ensured by a multimodal approach to transcription, may invite the research community to judge whether the blocks indeed capture the indicators that the blocks are considered to be an instance of.

5. Conclusion

In the teacher education setting observed, the very presentations have been unidirectional because the student-teachers performed their presentations without inviting the listeners to participate in a dialogue. This has conditioned the research project to focus on the relationship between the performing student-teacher and the pre-formed semiotic artefact. In accordance with multimodal social semiotic principles, this focus was sufficient for investigating how meaning is instantiated in action across the meaning-making devices employed by the presenter in the design of a pre-formed artefact and by means of the embodied resources, such as speech. Future studies should take into consideration the co-construction of meaning that occurs when a third party, the student-teachers watching, contribute by participating in the dialogue. Such a study could be motivated by extending the existing research on classroom talk that is approached through the lens of improvisation and the jazz metaphor. The focus could then be directed towards the semiotic artefact to investigate if and how it impacts the dialogue in the common effort by the teacher and students to construe meaning.

Funding

This work was supported by Norwegian Research Counci (NRC) [grant number 221058].

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Øystein Kvinge

Øystein Kvinge (f. 1972) has previously been working in the field of arts management in Bergen, Norway. He began his career at the BIT20 Ensemble and the Music Factory festival, and moved later on to the administration of Norwegian national company of contemporary dance, Carte Blanche, where he stayed for 8 ½ years. He worked as programme coordinator at the Bergen international festival from 2011 until he started as a PhD student at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL) in January 2014. Currently, he teaches music at various programmes for teacher education at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences in Bergen.

References

- Adams, C. (2006). PowerPoint, habits of mind, and classroom culture. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(4), 389–411. doi:10.1080/00220270600579141

- Amadie, J., & Christensen, K. (1990). Jazz improv: How to play it and teach it! A unique method for improvisation based on the concept of tension and release. Thornton Publications. Retrieved from https://books.google.no/books?id=7ftLAAAAYAAJ

- Apperson, J. M., Laws, E. L., & Scepansky, J. A. (2008). An assessment of student preferences for PowerPoint presentation structure in undergraduate courses. Computers & Education, 50(1), 148–153. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2006.04.003

- Atkinson, C., & Atkinson, R. E. (2004). Five ways to reduce power point overload. Creative Commons. Retrieved from www.indezine.com/stuff/atkinsonmaye.pdf

- Baerman, N. (2004). The big book of jazz piano improvisation. New York, NY: New Bay Media LLC.

- Barthes, R. (2003). Rhetoric of the image. London: Routledge.

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2011). Teaching for creativity with disciplined improvisation. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), Structure and improvisation in creative teaching (pp. 94–110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511997105

- Berliner, P. (1994). Thinking in jazz: The infinite art of improvisation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226044521.001.0001

- Bjørndal, B. (1978). Nye veier i didaktikken?: En innføring i didaktiske emner og begreper. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Black, M. (1962). Models and metaphors; studies in language and philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Camiciottoli, B. C., & Fortanet-Gómez, I. (2015). Multimodal analysis in academic settings: From research to teaching. London: Routledge.

- Carlson, M. (2017). Performance: A critical introduction. London: Routledge.

- Clark, R. C., Nguyen, F., & Sweller, J. (2011). Efficiency in learning: Evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Craig, R. J., & Amernic, J. H. (2006). Power point and the dynamics of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 31(3), 147–160.10.1007/s10755-006-9017-5

- Davies, S. (2001). Musical works and performances: A philosophical exploration. Oxford: Clarendon Press.10.1093/0199241589.001.0001

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dezutter, S. (2011). Professional improvisation and teacher education: Opening the conversation. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), Structure and Improvisation in Creative Teaching (pp. 27–50). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511997105

- Digital tilstand. (2014/2015). (No. 1). Tromsø: Norgesuniveristetet.

- Eisner, E. W., & Reinharz, J. (1984). The art and craft of teaching. Educational leadership., 40(4), 4–13.

- Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hesse-Biber, D. S., Kinder, T. S., & Dupuis, P. (2009). HyperResearch. Researchware.

- Holbrook, M. B. (2008). Playing the changes on the jazz metaphor: An expanded conceptualization of music-, management-, and marketing-related themes. Foundations and Trends in Marketing, 2(3–4), 185–442. doi:10.1561/1700000007

- Jewitt, C., Bezemer, J., & O’Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing multimodality. London: Routledge.

- Jones, A. M. (2003). The use and abuse of PowerPoint in teaching and learning in the life sciences: A personal overview. Bioscience Education, 2(1), 1–13. doi:10.3108/beej.2003.02000004

- Jurado, J. V. (2015). 5 A multimodal approach to persuasion in conference presentationsMultimodal Analysis in Academic Settings: From Research to Teaching (p. 108).

- Kinsella, E. A. (2010). Professional knowledge and the epistemology of reflective practice. Nursing Philosophy, 11(1), 3–14.10.1111/(ISSN)1466-769X

- Kjeldsen, J. E., & Guribye, F. (2015). Digitale presentasjonsteknologier i høyere utdanning — foreleseres holdninger og bruk. Uniped, 38(03). Retrieved from http://www.idunn.no/ts/uniped/2015/03/digitale_presentasjonsteknologier_i_hoeyere_utdanning_fore

- Knoblauch, H. (2008). The performance of knowledge: Pointing and knowledge in powerpoint presentations. Cultural Sociology, 2(1), 75–97. doi:10.1177/1749975507086275

- Kress, G. R. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge. Retrieved from http://books.google.no/books?id=ihTm_cI58JQC

- Kvinge, Ø. (2018). Teaching represented: A study of student-teachers’ representations of the professional practice of teaching. In K. Smith (Ed.), Norsk og internasjonal lærerutdanningsforskning: Hvor er vi? hvor vil vi gå? hva skal vi gjøre nå? (pp. 199–222). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Lancaster, L., Hauck, M., Hampel, R., & Flewitt, R. (2013). What are multimodal data and transcription? In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (2nd ed.). (pp. 44–59). London: Routledge.

- Longo, M. (1992). The technique of creating harmonic melody for the jazz improviser. New York, NY: Consolidated Artists Publishing Inc.

- MacAloon, J. J. (1984). Rite, drama, festival, spectacle: Rehearsals toward a theory of cultural performance. Philadelphia, PA: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

- Maxwell, J. (1992). Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review, 62(3), 279–301. doi:10.17763/haer.62.3.8323320856251826

- Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.10.4135/9781412957397

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. The Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.10.1111/tcre.2006.108.issue-6

- Montuori, A. (2003). The complexity of improvisation and the improvisation of complexity: Social science, art and creativity. Human Relations, 56(2), 237–255. doi:10.1177/0018726703056002893

- Nielsen, C. R. (2015). Interstitial soundings: Philosophical reflections on improvisation, practice, and self-making. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Osberg, D., & Biesta, G. (2003). Complexity, representation and the epistemology of schooling. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2003 Complexity Science and Educational Research Conference, 16–18.

- Pepper, S. C. (1942). World hypotheses: A study in evidence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Querol-Julián, M., & Fortanet-Gómez, I. (2014). Evaluation in discussion sessions of conference presentations: Theoretical foundations for a multimodal analysis. Linguistics: Germanic & Romance Studies/Kalbotyra: Romanu ir Germanu Studijos (pp. 66). Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH & Co.

- Rockwell, S. C., & Singleton, L. A. (2007). The effect of the modality of presentation of streaming multimedia on information acquisition. Media Psychology, 9(1), 179–191. doi:10.1080/15213260709336808

- Rowley-Jolivet, E., & Carter-Thomas, S. (2005). The rhetoric of conference presentation introductions: Context, argument and interaction. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15(1), 45–70.10.1111/ijal.2005.15.issue-1

- Schön, D. A. (1992). The crisis of professional knowledge and the pursuit of an epistemology of practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 6(1), 49–63.10.3109/13561829209049595

- Selander, S. (2008). Designs for learning–A theoretical perspective. Designs for Learning, 1(1), 4–22. doi:10.16993/dfl.5

- Selander, S. (2017). Didaktiken efter vygotsky—design för lärande. Stockholm: Liber.

- Selander, S., & Kress, G. (2010). Design för lärande: Ett multimodalt perspektiv. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23.10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Sweller, J. (2011). In Mestre, J. P. & B. H. Ross (Eds.), Chapter Two–Cognitive load theory. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press 37-76 Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387691-1.00002-810.1007/978-1-4419-8126-4

- Tufte, E. R. (2003). The cognitive style of PowerPoint graphics press. Retrieved from http://books.google.no/books?id=3oNRAAAAMAAJ

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2016). Masterclass semiotic technology: Software, social medial and digital artefacts. Odense: University of Southern Denmark.

- Van Manen, M. (1986). The tone of teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Educational Books.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Zhao, S., Djonov, E., & van Leeuwen, T. (2014). Semiotic technology and practice: A multimodal social semiotic approach to PowerPoint. Text & Talk, 34(3), 349–375. doi:10.1515/text-2014-0005