Abstract

“The field of ethics in teaching as a moral profession is a robust and compelling one. It captures the interest and imagination of scholars, researchers, and practitioners alike because it is so very important and integral to the world of education”. For the same purpose, the major aim of the current paper was to come up with a code of professional ethics for the academic context of universities through the available literature and to later on localize (50 EFL, English as a foreign language, university instructor-participants) this code through a semi-structured interview so as to adapt it according to the needs of Iranian English as a foreign-language university instructors. Afterwards, the code was utilized to design an instrument for the aforementioned instructors’ understanding and commitment to professional ethics. Finally, partial least square variance-based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to establish the reliability and validity (80 Iranian English language university instructor-participants) of the already designed instrument. The thorough analysis of the literature resulted in 4 major components (commitment to profession, learners, society and organization) for the code along with relevant items for each. The localization process of the code revealed that to Iranian university instructors, only two of the four components of professional ethics stand as crucial (commitment to profession and learners) and there needs to be abundant awareness-raising measures regarding the other two aspects of professional ethics. Overall, this study concerns Iranian English as a foreign-language educators/teachers and the results exhibited that educators display commitment to learners and profession but should become more aware of commitment to organization and society. The availability of the postulated code at universities can be one such measures which also stands as one of the important implications of this research. The instrument also turned out to be reliable and valid and there existed only two items which needed to be eliminated out of the instrument through the validation process.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Ethics has almost always been one of the concerns of humans in both their private and public lives. In this study, the researchers focused on the idea of professional ethics in the teaching profession. The primary goal was to develop a code of professional ethics based on the available literature. Four components were extracted as a result: “commitment to profession, learners, society and organization”. Next, the researchers localized this code through interviewing English as a foreign-language Iranian university instructors. The outcome revealed that these Iranian instructors were not much aware of two of the constructs of professional ethics: “commitment to society and organization”. Afterwards, an instrument was designed based on the current code and its validity and reliability was estimated through statistical means. Two items were removed from the questionnaire in this phase. Overall, teachers need to possess enough knowledge about professional ethics especially the constructs of commitment to society and organization.

1. Introduction

1.1. Significance of the study

How much importance a teacher, educator, chancellor etc. attaches to the notion of ethics in the twenty-first century? Can ethics help us reach a better understanding of professionalism? Is ethics defined differently when it comes to the academic context of universities? These issues, along with many other corners of ethics, have formed the core concern for all the following discussions on professional ethics in this study. The researchers will also do their best to provide a comprehensive foundation for developing a code of professional ethics which can work out as a solution to some of the ethical dilemmas at universities.

As typically understood, “teaching reflects the intentional effort to influence another human being for the good rather than for the bad” (Hansen, Citation2001, p. 828, as cited in Campbell, Citation2008, p. 7). Consequently, many researchers including Campbell (Citation2000) emphasize the importance of providing codes in the way that they “can provide important and useful guidelines regarding ideals, behaviors and decisions” (Beck & Murphy, Citation1994, p. 9). Elsewhere in the article, Campbell (Citation2000) gives reference to Haynes (Citation1998) saying that codes do provide guidelines to the implementation of ethical values. And she also calls on the idea presented by Lovat (Citation1998) that the endorsement of an ethical code would signal a new maturity for the profession. An overall perspective which is repeatedly observable in her paper is that “teachers ought to seriously engage in teaching as an ethical practice” (Hostetler, Citation1997, p. 205). In her following article in 2008, Campbell asserts that because teaching is a moral activity, it calls for attention to teachers’ conduct, character, perceptions, judgment, and understanding (Hansen, Citation2001).

Following the same pattern of thought, Freeman (Citation2000, p. 2) provides further proof for the vital existence of an ethics code through applying Kipnis (Citation1986) words on adherence to a code of ethics which is, in fact, one of the important characteristics that differentiates professions from other occupations. He asserts that professionals who know how to “do ethics” think systematically when they face difficult moral decisions. (Nash, Citation1996; Strike & Ternasky, Citation1993).

Taking a postmodern perspective of ethics in twenty-first century, it is observed that ethics has changed into a priority for almost all organizations and it is neither considered a luxury, nor a priority. This means, in the competitive world today, the twenty-first century organizational leaders have, and actually need to have, a lot in their minds regarding various issues such as their mission, vision, values, culture, etc. All these help organizations to find out how they can place ethics as a priority in their organization. Also, ethical values need to achieve recognition by the elite group in organizations such as universities. Additionally, once changed into a priority in twenty-first postmodern century, ethics will not only affect decision-making, but also the institutional culture (Brimmer, Citation2007). To close, according to Kidder (Citation2001), “The principle task of this decade (twenty-first century) is the creation and nurturing of a values-based culture”. And as a result, due to the extensive amount of time people spend at work, much of that nurturing must take place in the business environment (organizations).

On top of all the already discussed, ethics is also crucial in our day to day life. Many number of articles and researches have focused on illustrating the reasons ethics comes as important not only in our public life but also in our private lives! Regarding the daily life of humans, ethics is mainly involved with the effects of our behavior on others (Beach, Citation2013). Mostly, in almost all cultures, ethics on a daily basis, is concerned with fairness, honesty, trustworthiness etc. however, recently there has been a new notion which stresses the fact that ethics is all about behaviors and actions that discourage human suffering and results in promoting happiness among individuals. The product of such a view is surely an egalitarian society (Lane, Citation2005). Additionally, in the current century, there has been reported a heightened interest in everybody regarding ethics. This might be the result of people caring for the quality of life and its values prior to other factors which will surely be more visible if ethical principles are met by each and every individual in the society. In spite of this importance of ethics in daily life, there is a lack of reflection which people need. They are to think and reflect on their decisions on a daily basis so as to develop this ethics-sensitive perspective in the younger generation who will be the prospective future educators, teachers, leaders, etc.

Ethics in Iran has touched many major fields of study including medicine, varied branches of management, law etc. and to the best knowledge of the researcher, these fields, specifically medicine and management, have developed comprehensive codes of ethics applicable for anyone who chooses to pick these majors as his/her profession. Numerous studies which have been carried out in these fields, have helped the members of these professions to gain a comprehensive understanding of ethics. Taken as an instance, in a study on professional ethics and its role in medicine (Fazeli, Fazeli Bavand Pour, Rezaei Tavirani, Mozafari, & Haidari Moghadam, Citation2012), the importance of ethics in medicine is highlighted from time to time in the paper. It has even been expressed that issues relevant to medical ethics have attracted serious issues of science to itself. The reason for this is the fact that ethics in medicine embraces aspects which are beyond general norms of ethics and therefore, what is stated as general principles of ethics cannot fulfill the requirements of the medical profession.

Similarly, the field of teaching English as a foreign language, same as any other profession, needs to form a comprehensive code of professional ethics to let all its staff be aware of its norms and values.

Therefore, what a teaching community in general and an Iranian one in particular need to consider as its mission, is to provide ELT instructors with a comprehensive code of ethics which illustrates the roles professional ethics serve in education. This means, there needs to be moves toward codification and domestication of teachers’ work, responsibilities and identities (Clarke & Moore, Citation2013).

Additionally, because it is the post method era that we are concerned with these days, it would not seem far too illogical if we Iranian EFL teachers of universities, apart from facilitating learning of academic subjects, be responsible for the moral uprightness of the students to whom we teach. Furthermore, we should always bear in mind that merely teaching moral responsibilities is not sufficient and us, teachers should also constantly construct and re-construct ourselves as academically and socially accepted models that students should emulate on moral issues.

Another reason which signifies the existing problem in the EFL context of Iran is that still we are observing teachers whose end product of their classes are not fully satisfying, despite the great number of classes they have taught and the huge amount of experience they are tagged with! Part of this failure, it seems, goes to either the academic contexts’ not having a clear-cut set of ethical codes for teachers, or teachers’ lack of attendance and attention to such provided set of guidelines. Therefore, to devise a comprehensive code of professional ethics and investigating teachers’ awareness of such ethical issues would be an essential step to be taken in the Iranian EFL academic context.

Therefore, the following questions were addressed in the study:

What are the components of a code of professional ethics employed in the Iranian EFL academic context?

What is the factor structure of professional ethics in teaching?

1.2. Statement of the problem: the need for more local research on professional ethics in teaching

Gluchmanova (Citation2015) maintains that in the teaching profession, teachers are the ones responsible for leading students through making appropriate decisions and also towad actions and behaviors that show respect and dignity for all human beings including peers, parents etc. Gluchmanova (Citation2015) also asserts;

Teachers of ethics could be a significant stimulus when forming students on their journey to achieving higher quality, or added value, of human dignity of a moral agent in the future. Accordingly, a crucial role of teachers, as well as the teaching profession is to, together with parents and families, help students on their path from potential to full moral agents (p. 4).

With regard to his discussion on ethics and human dignity, one may assume that morality can be considered a significant issue in the mutual relationship between the teacher and the students and vice versa. Therefore, education needs to be also directed toward a full development of human personality as well as strengthening respect of human rights in order to achieve mutual understanding, tolerance and friendship (Fitzmaurice, Citation2010) and this cannot be achieved unless teachers rise for help. As Billings (Citation1990) voices, “It is often true that if the teacher does not respect the student’s dignity, then he/she cannot expect his/her own dignity to be respected”(p. 66). To conclude, we can assume that “teachers at all levels of education should ensure the cognitive, intellectual and moral progress of their students and show them appropriate respect and appreciation” (Gluchmanova, Citation2015, p. 4).

There also exist a number of additional concerns which stand up for why a local research needs to be carried out in the EFL academic context of Iran. Many behaviors and measures taken by managers are believed to be the result of ethical values and can be said to have their roots in ethics. Therefore, disregarding ethics in managing organizations such as universities, can cause horrible problems for institutions. This ignorance of ethics in professions or any observable weaknesses in maintaining ethical principles when dealing with students, teachers, colleagues etc. can put the legitimacy of any organization under question. Consequently, designing a comprehensive code of professional ethics for Iranian EFL academic context seems to be a vital need. This is also because poor ethics in a profession, can influence instructors’ attitude toward their career, organization or even toward their manager. Moreover, today, the presence of professional ethics is considered as a competitive benefit for organizations and surely EFL universities are not isolated cases.

Additionally, the inclusion of professional ethics at universities of Iran, is believed to have a drastic influence on the outcomes of universities, their social activities, their productivity, and ultimately amends the relationships within and beyond the organization as well as reducing the number of possible risks. This will happen, mainly because higher education is a professional system which covers a wide range of human-like behaviors.

Another prominent reason for this study to happen is because science and higher education are becoming worldwide, international processes and for this to happen, a mutual language in ethics, especially on a worldwide basis, is required. And to the best knowledge of the researcher, the available codes of ethics in Iran only cover those aspects of ethics which deal with ethical concerns of doing research and a comprehensive code which embraces the major corners of professional ethics is missing in the EFL academic context of Iran. Consequently, a code of professional ethics for universities of Iran will enable them to move along this worldwide process while holding up that mutual ethical understanding.

Another crucial reason which supports the need for the presence of an ethical code in the EFL context of Iran, can be directed to the issue that because teaching occurs in a community of educators and each educational system has professional codes of ethics/conduct for the teachers, that code of ethics leads to self-government and an integral disciplinary process that provides a mechanism for controlling inappropriate professional behavior. Thus, various miss-behaviors are avoided through the implementation of an ethical code.

What comes next, might be the reality of any code of ethics giving a vision of excellence to any organization with regard to what each individual should do and what they can probably achieve through following this code. Also, the current assumption is EFL instructors same as learners are strongly required to be aware of the values and attitudes that underpin the framework of their immediate organization.

Last, looking more closely at teachers, it would be easy to distinguish that they have always been the very first observable component of any teaching learning context/program. Therefore, equipping EFL instructors with necessary tools will not only help them to better perform in their classes but will, undoubtedly, aid universities to come up with highly qualified teachers who are well aware of ethical dilemmas at their workplace. Thus, the need for a tangible code of ethics as one such tool, which comes as the immediate and primary need for any working place, is once again highlighted. Let us bear in mind that what a code of ethics might look like in any university reflect the organization’s values, pedagogical needs, priorities, expectations and standards. It also helps EFL University students identify, understand, and make progress toward resolving moral conflicts while adding to their expertise. Consequently, EFL teachers should know how they can be part of this code and as a result part of the curriculum.

1.3. Universities & academic capitalism

Another notion which has affected the ethical aspects at universities is academic capitalism. One of the problem rising as a result of this kind of capitalism refer to the fact that due to the great move toward the need for academic degrees, many of the members involved in academic activities opt to behave in quite varied unethical ways and what comes as the priority is people’s sole attention to fulfill their desire. As Beach (Citation2013) discusses in his book on “academic capitalism in china: higher education or fraud?”, this kind of perspective mostly occurs among those teachers, students or decision makers who are not motivated enough and who do not have a clear vision about what they will be actually doing once they have enrolled at university. According to Beach (Citation2013), “social pressure” and earning a chance for having a “decent job” can stand as other reasons for academic capitalism to occur and as a result ethical behavior not being met.

What we mostly observe in a capitalist circle, are teachers, students or staffs who do not care for their personal and moral development. Individuals who strive to invest their social, economic, or ethical capital only for the sake of securing their future course of life. Overall, under such circumstances, quality education, ethical standards and educational development are the very first elements which are surely lost at universities! To conclude, in case all the members of an academic setting are ethically trained individuals who place ethical behavior as a priority in their personal and public lives, we would observe less unethical actions (academic capitalism) taking place.

1.4. Ethics: a way of accountability in the value system of Islam

Ethics, to the best knowledge of the researchers, is not only of importance in the teaching profession throughout the world, but also in most of the Islamic religions and the day to day life of humans. As obvious, an individual’s religion will not only affect his/her world view but also his/her personal as well as public performance and ethics is one of the ingredients of many religions. Therefore, as the current study sheds light on the importance of professional ethics for English as a foreign-language university instructors of Iran, a reference is given to the importance of ethics in the value system of Islam in Iran.

As the front page of the website of “WhyIslam” puts the notion forward, “ethics, in this regard, generally refers to a code of conduct that an individual, group or society hold as authoritative in distinguishing right from wrong”. Continuing the same pattern of thought, they claim that Islam, as a comprehensive way of life, encompasses a complete moral system that is an important aspect of its world-view. What their critics highlight is the fact that human beings live in an age where good and evil are often looked at as relative concepts. In Islamic worldviews; however, it is held that not only moral positions are not relative, but also Islam defines a universal standard by which actions may be deemed moral or immoral. Therefore, one can conclude that “Islam’s moral system is striking in that it not only defines morality, but also guides the human race in how to achieve it, at both an individual as well as a collective level”(retrieved from WhyIslam.org).

Keeping all the already-mentioned quotes from the critics of WhyIslam forum in mind, it can be an easier task to do at this stage i.e.to find the importance of ethics in teaching and for teachers. Teachers, as agents in the society, can find ethics as a tool which, if understood and used appropriately, can bridge the gap between themselves and the students, themselves and their colleagues and themselves and the society as a larger perspective of the community they live and work in. To verify this, a reference can be given to the same forum, which rightly mentions that “for an individual as well as a society, morality is one of the fundamental sources of strength” (retrieved from WhyIslam.org). This means that while respecting the rights of the individual within a broad Islamic framework, Islam is also concerned with the moral health of the society.

Considering the importance of ethics in Iran, which is one of the countries holding many ideas underpinned by ethics, it can be mentioned that principles of professional ethics are believed to possess dignified values within them. Thus, observing the principles of professional ethics will lead to observing social norms and relations. As a result, an initial understanding of the basic components of ethics sounds quite essential (Ahmadi Hedayat, Karimi, & Saveh, Citation2017).

The ethical criteria are indeed the guiding blueprints which help the members of an organization to perform their responsibilities in as clear a way as possible. These criteria are derived from the local culture, the civic culture and in case of our country, Iran, are believed to be affected by our Islamic religion. For instance, Mohammad, the prophet of Islam, initiated the leadership of Muslims’ political and social behavior through the leading and teaching of their thoughts. Whatsoever he wanted his followers to do in practice, came after giving them a thorough awareness of all the values. Forming a true sense of reflection, a flawless cognition and a virtue-driven ethics, along with introducing human’s spiritual attractions have always been among the basic foundation in the framework of Islam (Ahmadi Hedayat et al., Citation2017).

Last, in the academic context of Islam, professional ethics is referred to as a collection of regulations that a person has to voluntarily observe based on his/her consciousness and nature (Karami, Galavandi, & Galaeei, Citation2017). Consequently, what is implied throughout the already mentioned, is the fact that internalizing ethics, as a value-laden individual factor, can help people express a true sense of accountability in the Islamic society of Iran.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

The data collection procedure in this study was of two phases (qualitative and quantitative). Therefore, the participants who attended the study were in two groups, each of which will be explained hereafter.

Collecting data for the purpose of localizing the code of professional ethics embraced the first group of participants. These teacher participants included 50 EFL university instructors. Majority of these male and female participants (65%) were teaching B.A. or M.A. programs either in TEFL or Translation and possessed an educational degree of M.A. or were PhD candidates. A great number of them (80%) had an average teaching experience of 10–15 years. They all believed they possessed an excellent proficiency level in the field. The mentioned teachers were the teaching staffs of Azad University of Mashhad, Khayam University, Sabzevar University, Azad University of Birjand and Tabaran Institute of Higher Education as well as Tehran Central Branch of Azad University and Bojnord Payam-e-noor University. They participated in a semi-structured interview. The interview was carried out for the instructors who were available to the researchers and those who were not within the availability of the researchers received the question via email.

The second phase of the data collection, which was a quantitative one, included 80 EFL university instructors who helped the researchers to establish the reliability and the validity of the designed instrument and to also postulate a model through partial least square variance-based structural equation modeling. This group of participants possessed almost the same characteristics. That is, they were mostly the ones teaching at Azad University, non-profit and Payam-e-noor University. These participants were the ones holding M.A. and PhD degrees in English or they were PhD candidates in either of the three fields of English. They were mostly aged between 31 and 40. And possessed a teaching experience of either 10 to 15 or over 15 years. The individual characteristics (age, teaching experience, etc.) of these participants are reported based on the information gathered from the bio data section of the questionnaire. Also, considering both qualitative and quantitative data collection phases, random selection of the participants (from various cities and universities) was applied in order not to affect the results or the generalizability for the Iranian academic context. Moreover, for the same purpose of generalizability issue of the results, the researchers did their best to collect data from as many sectors of academic settings as possible i.e. the state and non-state universities and also from as many provinces of Iran as possible.

2.2. Instrumentation

2.2.1. Semi-structured interview

Once the core components of the code of professional ethics and its sub-categories were prepared through an in depth analysis of the available literature including previous researches and the available ethics codes, localizing this code was considered the second aim of the researchers (how the researchers came up with the four components of professional ethics, is thoroughly elaborated when providing the answer to the first phase of the first research question).

To this end, the semi-structured interview was run with 50 Iranian university instructors. The participant teachers were provided with one question including “what components they believed should be included in a code of professional ethics for the Iranian EFL academic context”.

The amount of time allotted for running the semi-structured interview was 15 min per participant and their answers were recorded. In case these instructors were not available to the researcher, the questions were sent to them via email and the responses were sent back within few days.

Once the interviews were run, the answers were analyzed so as to extract the common and the most frequent beliefs and suggestions of these EFL instructors about the probable components of a code of professional ethics in the Iranian EFL academic context. A thematic, deductive approach to data analysis was opted for this phase and the process for caring this stage is fully elaborated in the “results” section (the qualitative data analysis phase).

This comparison was run with the purpose of checking how far the components of an ethics code in EFL teachers’ perspective was similar or different from the one the researchers had already extracted based on the available literature. This also means that apart from localizing the available code of ethics, the content validity of the code was also put under scrutiny. Moving ahead, the following step which was taken was to apply changes, if any, to the present code according to the ideas accumulated through the semi-structured interview, so as to localize the professional code of ethics.

2.2.2. Questionnaire on professional ethics in teaching (QPET)

Once the components of the ethics code along with its sub-items were extracted based on the available literature, the accumulated content was localized through a semi-structured interview with 50 EFL university instructors. This means that any notion which was highly frequent among teacher participants was added to the current code. At the same time, there existed some notions mentioned by teachers which were already extracted from the literature and this localization process cross-checked the content validity of the code, as well. Finally, when the localization process was over, the modifications to the code were cross-checked and verified by three experts in the field (two in the field of ELT, one in the field of Management), once the final draft was presented. These experts were first selected based on their mastery and experience in the fields of qualitative and quantitative research in English-language teaching and management and second based on their availability to the researchers as well as their willingness to participate in the process of data collection and analysis.

Afterwards, the researchers used the code of professional ethics in order to change it into a tool for checking EFL university instructors’ understanding of professional ethics in teaching. First, a bio-data section was designed which asked the teacher participants questions regarding their age, gender, years of teaching experience, educational status and their English proficiency. Later on, the items of the model were transferred into statements, showing teachers’ point of view, which all started with “I” which is a self-decelerating design. Next, a five-point Likert-scale design was adopted for the questionnaire which deemed teachers to mark each statement from 1 to 5 (never, always) based on how frequent they believed they followed each of the ethical issues in the questionnaire. The allotted time for filling in the questionnaire was 15 min.

The questionnaire covered all the four categories of the code of professional ethics, namely as Teachers’ Commitment to Learners, Teachers’ Commitment to Society, Teachers’ Commitment to Profession, and Teachers’ Commitment to Organization. Each category embraced 11–20 items which compromised a 61-item questionnaire. The process of how these components along with their items selected, are thoroughly elaborated in the “results” section.

However, since the researchers did not aim to give the teacher participants a pattern of thought or direct/influence their answers in any way, the titles for all the four categories were eliminated and the questions of all those four categories were fairly distributed throughout the questionnaire so as to accumulate more valid and un-biased answers.

Considering the validation process of the questionnaire two approaches were taken; expert validation and construct validation (through quantitative means). As for the expert validation, once the four categories of the code and the sub-items of each category were extracted out of the related literature, three experts in the field were asked to review the items and give comments on either the notions, the wording of the statements, the relevance of each item to its category, or any other crucial point and the required modifications were applied accordingly. Following this, the researchers went for the localization process of the questionnaire and when the procedure was fully and completely carried out and new items were added to the previous version, once again the revised questionnaire was handed in to the same three experts and they checked the consistency of all the items to their relevant category, the wording of the statements and appropriate modifications were also applied. Besides, this process could stand as investigating the content validity of the code.

Considering the statistical construct validation and the reliability of the instrument, PLS_SEM smart software was employed and various means such as Convergent Validity, Discriminant Validity, Factor Loadings and Cronbach Alpha were deployed. In this phase of the study, 80 EFL university instructors attended the validation process, the results of which will be fully discussed in the data analysis section.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection throughout the current study commenced in July 2017 and ended in December 2017. The process of carrying out this research which resulted in a professional code of ethics, consisted of several stages which embraced both qualitative and quantitative means. To begin with, the researchers did a thorough analysis of the available literature on the notion of ethics as well as the available codes of ethics which belonged both to universities inside the country and overseas. Also, a theoretical framework was opted by the researcher which acted as the basis for the code (Waldo, 1996).

Once the components and sub-components of this ethics code were designed based on literature, the first draft was handed in to three experts in the field to check out the statements, the complexity of the wording procedure, the go-togetherness of the items with their components, their relevance to the realm of teaching, etc. and following that, the required modifications were applied accordingly. Afterwards, 50 EFL university instructors were randomly chosen and were asked to take part in the qualitative phase in order to answer two open-ended questions either through email or a semi-structured interview (based on their willingness and their availability to the researcher). The two questions centered on what their definition of these EFL university instructors about ethics in teaching was and also what components they thought could compromise a code of professional ethics for the EFL Iranian academic context of universities. The purpose of this question was to localize the code which was extracted out of the available literature.

Having run the interview, the accumulated data was closely analyzed through a deductive approach so as to draw a comparison between the code extracted from the available literature and what EFL teachers claimed must be included in a code of professional ethics suitable for an EFL academic context. Following this analysis, necessary modifications were applied to the first code so as to localize the professional ethics code. Following this procedure, once again the finalized version was handed in to the same three experts, who were also university instructors or faculty members, to give comments on the wording of the statements, the go-togetherness of all the items in each category and their overall consistency and any advices were applied to the last version accordingly. This process could also be notified as the content validity of the code.

Afterwards, the modified code of ethics was converted into and used as a questionnaire on professional ethics in teaching with the aim of providing a validated instrument for future studies in the realm of ethics and ethical conduct in teaching. This questionnaire was targeted to check the understanding of EFL University instructors about the extent they care to follow and maintain ethical issues in their profession. The questionnaire embraced 61 items on a five-point Likert scale which was administered to 80 EFL teachers so as to establish the construct validity as well as the reliability of the instrument.

The very first measure which was taken regarding the data analysis was a qualitative one. A semi-structured interview was run with 50 EFL university instructors in order to accumulate their perceptions on an appropriate code of professional ethics for the academic context of Iran. The responses were analyzed by the researchers based on a deductive approach to qualitative data analysis and in order to make sure of the extracted notions, two other researchers in the field were asked to go over the instructors’ responses once again and check out the consistency of the extracted notions with the constructs of the code. Also, once the responses were transcribed and categorized thematically, some of the teacher participants were asked to read their responses and give comments on whether they were well understood by the researcher. These two stages, stood as verifying the validity of the extracted themes and notions. The same procedures were undertaken by the researcher to analyze the instructors’ responses for the second question of the semi-structured interview which aimed at checking how EFL instructors defined ethics in teaching.

As for the construct validation and the reliability of the presented instrument on professional ethics in teaching, partial least square variance-based structural equation modeling software was employed and various means of estimating reliability and validity were run through the software.

2.4. Study design

As the researchers’ purpose was to first provide a localized code of professional ethics for universities of Iran through qualitative means and following that to design and validate a questionnaire on professional ethics in teaching, through quantitative means, as well as establishing a correlational perspective of the study, the current research can be said to have enjoyed both qualitative and quantitative means of data collection and since both were equally crucial in carrying out this research; therefore, the design was a mixed method.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative data analysis: theoretical framework & developing a code of professional ethics for Iranian EFL university instructors

From among the available relevant frameworks applicable for academic contexts, the thought pattern postulated by Waldo (Citation1956) was opted. The reason this framework was opted, rooted in the fact that his model/book is believed to “have done much to broaden the horizons and deepen the intellectual content of academic public administration in the United States as well as many other educational centers” . Therefore, the model was used as a pattern of thought and a kind of mind set for accumulating more data relevant to a code of professional ethics. In his model, there existed 12 kinds of occupational commitment which cover any aspect of ethics in occupations. However, since the scope of the study centered on ethics in academic contexts (universities) only, the four components which were directly in line with universities’ educational scope were opted as the main constructs. These included Commitment to Society, Commitment to Organization, Commitment to Learners, and Commitment to Profession. Worth mentioning that there also existed some other sources which had a lot in common with the current extracted constructs of the code.

Next after this, in order to extract items underlying each of these four components, the researchers spent abundant time analyzing and reviewing the available literature. This included varied codes of ethics, and ethical guidelines which all belonged to different universities both inside and outside Iran. Some of the sources include University of Birmingham Code of Ethics, Code of Ethics of the University of Southern California, Code of Ethics of the University of Virginia (2004), Ministry of Education and Employment: Teachers’ Code of Ethics and Practice (2012), Code of Ethics for Certified Teachers: Education Council, New Zealand and Professional Ethics for the Profession and some other sources which were comprehensively discussed in chapter two. Some of the codes which belonged to Iranian universities were namely as the codes of ethics for Al-Zahra University, Tehran University, Fani-Herfeii Department of Education etc.

Majority of these codes, directly or indirectly, more or less, possessed similar themes, however, almost many of them did not have their code categorized under clear-cut borders i.e. a 20 or 30 item code was used as a guideline without specifying what criterion each item or theme belonged to (university, students, etc.). And for this reason, choosing components based on Waldo’s (Citation1956) framework seemed a required step to be taken by the researchers. Going through all the available literature, codes of ethics and the within-reach ethical guidelines, the researchers extracted relevant items for each of the four components and finally they came up with a four-component code of ethics each of which included 11–14 items which resulted in a 51-item ethics code. Once the first draft of the code was prepared, it was handed in to three experts in the field and they went through all the items so as to check the go-togetherness of the items, their comprehensibility, wording, etc. and any recommended modifications were applied accordingly. The first draft of the code of professional ethics, which was purely based on literature, is illustrated in Table .

Table 1. The early draft of the code of professional ethics

The second stage for preparing a code of professional ethics for the Iranian EFL academic context, was to localize the first draft of the current code of professional ethics. For doing so, an open-ended question was employed in the form of a semi-structured interview with 50 EFL instructors.

The question required EFL university instructors to name the notions or components they believed a code of professional ethics aimed to be employed in universities of Iran must possess. Once the data was accumulated, all the 50 interview results were examined all at the same time, through a deductive approach, in order to cross-refer to the various available data sources. This enabled the researchers to move back and forth in the data whenever the need was immediate.

After transcribing the accumulated data, all of them were coded thematically and a range of common key themes which contributed to locating the components of a code of professional ethics, emerged and were consequently extracted and categorized and finally they were discussed in the teaching learning process.

Maintaining a closer perspective of how the qualitative data analysis was carried out, it is important to mention that a thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation1998) i.e. a deductive approach was used; that is, generation and categorization of codes resulted from established theory and prior research findings (the four components of code of professional ethics already extracted from the literature). Afterwards, raw data themes, from the transcribed interviews, were identified and coded and instances for each category were identified and determined. Finally, the reliability of these codes was established. In order to achieve reliability, an external researcher (a second mentor and experienced instructor in the field), familiar with qualitative research, checked the codes as well as the extracted ideas and their instances and finally, any further modifications were applied. “Throughout the qualitative phase, ongoing analyses (Rossman & Rallis, Citation1998) were conducted with the assistance of a peer debriefer (the supervisor, in this case, who is an expert in the field), and notes were made concerning the raw data. These sessions included meetings with him to examine both methodological procedures as well as approaches to the interpretation of the data” (Patton, Citation1990; as cited in Ashraf & Kafi, Citation2016).

Moreover, in order to check the validity of the transcripts and the accumulated data, some of the instructors were randomly chosen and were asked to verify their interview results by reading their transcription 2–5 days after the interview had been conducted and further revisions and modifications were applied if mentioned by any of the participants of the study.

Finally, when their answers were carefully and cautiously analyzed based on the previously explained procedures of qualitative data analysis, the most frequent and recurring notions were extracted and were eventually added to either of the four relevant categories of the ethics code. Ultimately, the 51 item code of professional ethics changed into a 61-item code. Also, in order to make sure of the kind of classification of the notions and their true assignment to different categories, the same three experts were once again asked to give comments on the relevance of the items to their category, their wording, the comprehensibility etc. and any recommended suggestions were applied accordingly. The localized draft of the code of professional ethics, for each of its four components, is illustrated hereafter respectively. The localization results for the first component are illustrated in Table .

Table 2. Localized code of professional ethics: commitment to learners

The thorough analysis of the results revealed interesting outcomes. First of all, there were some notions mentioned by EFL instructors that already existed in the first draft of the code. This could mean that ethics (in teaching), in some ways, might mean the same in any academic context, no matter what country, nation or nationality you are teaching in! The items which were strongly frequent in both the two drafts of the code, regarding the first component, included item numbers 1, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14.

Next after this, there were some notions which were highly recurring among teachers; however, they did not exist in the early draft of the code. Therefore, these ideas were added to the relevant constructs of the current code and any further modifications were applied accordingly. As for the first component, the notions which totally new to the code included item numbers 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20. Table illustrates the localization process for the second component of the code.

The localization process for the second component of the code revealed that the notion which was highly recurring in both drafts of the code was item numbers 23. There did not exist any notion which could be considered as totally new for this component of the code of professional ethics. Table depicts the localization result for the third component of the code.

Table 3. Localized code of professional ethics: commitment to society

Table 4. Localized code of professional ethics: commitment to profession

Table 5. Localized code of professional ethics: commitment to organization

As for the third component of the code, the results of the interviews depicted that item numbers 32, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, were highly referred to by almost all the EFL instructors. Item numbers 46 and 47 were the ones which were strongly repeated by the EFL instructors and they were totally new to the code and consequently they were added to the early draft. The results for the localization process of the last component are illustrated in Table .

Regarding the last component of the code of professional ethics, the results revealed that item numbers 48 and 51 were the most recurring items among EFL instructors which already existed in the early draft. However, when it came to commitment to organization, only item number 60 was the one which was highly mentioned by many of the EFL instructors and therefore it was added as new notion to the final draft of the code.

To highlight, what came out as even more surprising, was the fact that once the answers were analyzed and recurring items were identified, almost all the notions expressed by the EFL instructors belonged to the two categories of “Commitment to Learners” and “Commitment to Profession”. This means that to Iranian EFL instructors ethics comes as following guidelines either related to one self (profession) or one’s learners only. Except for item numbers 23, 48, 51, and 60 (out of 61), there did not exist any other relevant notion mentioned by teachers, especially when it came to the category of “commitment to society”! Therefore, it seems that the other two categories of the current code of professional ethics (Commitment to Society and Commitment to Organization) can operate as a tool for raising teachers’ awareness in other realms of ethics including their commitment to the organization for which they are working and the kind of commitment they are expected to possess for the society they belong to.

3.2. Quantitative data: the factor structure of professional ethics in teaching

The scope of the second research question in this study centered on estimating the construct validity of the provided instrument on professional ethics in teaching. The process of turning the code into a questionnaire is fully explained in the “instruments” section. However, the questionnaire and its items were ultimately arranged in this way:

Teachers’ Commitment to Learners included item numbers 1, 2, 7, 8, 13, 14, 19, 20, 25, 26, 31, 32, 37, 38, 44, 45, 51, 52, 56, and 57.

Teachers’ Commitment to Society included item numbers 3, 9, 15, 21, 27, 33, 39, 46, 53, 58, and 59.

Teachers’ Commitment to Profession included item numbers 4, 5, 10, 11, 16, 17, 22, 23, 28, 29, 34, 35, 40, 41, 47, and 48.

Teachers’ Commitment to Organization included item numbers 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 43, 49, 50, 54, 55, 60, and 61.

In order to commence the data collection relevant to the validation process, the questionnaire was transformed into a Google doc format and was emailed or sent (via social networks) to 110 EFL university instructors out of which only 80 responded back (the characteristics of whom are explained in the “participants” section).

To check the construct validity as well as the reliability of the tool, PLS-SEM (Partial Least Square variance-based structural equation modeling) was employed to investigate the relationship among latent variables. Using the aforementioned software which has turned into a widely recognized data analysis platform in any research field including social sciences and behavioral studies (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Citation2011), mainly because of being efficient with small sample sizes (Esposito Vinzi, Trinchera, & Amato, Citation2010), one can check the construct validity and reliability of a questionnaire. It has also proved to be of use where theory is still less developed or proposed (exploratory researches) (Rِnkkِ & Evermann, Citation2013).

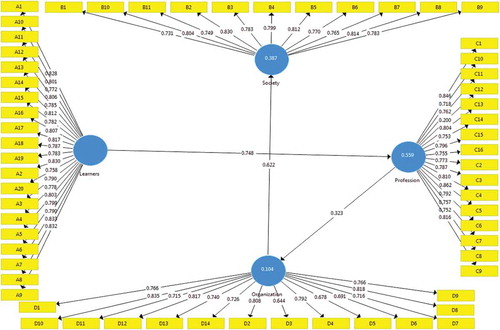

Formative and Reflective are believed to be the two kinds of measurement scales when using structural equation modeling. Since the indicators of this study are to correlate highly and in an interchangeable way, Reflective Model was therefore the appropriate one and the variables’ reliability and validity have to be thoroughly inspected (Haenlein & Kaplan, Citation2004). Therefore, the Model of Standard Coefficients is illustrated hereafter in Figure .

As illustrated in Figure , the researchers designed the model assuming that the construct of Commitment to Learners bears a relation with Commitment to Profession. Commitment to Profession holds a relation with Commitment to Organization and Commitment to Organization depicts a relation with Commitment to Society. Considering the postulated model, the construct validation of the instrument was investigated.

In order to prove the suitability of the selected measurement model, various means for measuring reliability and validity of the latent variables needed to be taken. Factor loadings coefficient was employed as one of the means of estimating reliability at this phase. Through this data analysis procedure, factor loadings was calculated by checking how far the items of one variable correlate with that latent variable. And if this correlation is equal or greater than 0.4, it can be claimed that the variance between that variable and its items is greater than the error variance and therefore the reliability regarding that variable is deemed to be verified and proved.

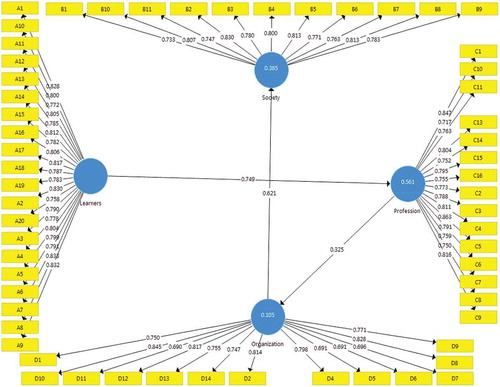

When using Factor Loadings Coefficient, in case the result for any of the items of a variable is lower than 0.4, the researcher needs to either modify that item or totally remove it. According to the obtained results, the coefficient index for 59 items (out of 61) was above 0.4, varying from 0.7 to around 0.9. However, there existed only 2 items which possessed a low index. (one was 0.20 and the other 0.64). This happens because loadings above 0.70 are considered to be high, whereas loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 are satisfactory if elimination of the indicators does not result in an increase in the reliability of the model (Hair et al., Citation2011). Therefore, these two items were consequently removed out of the scale and the 61-item questionnaire changed into a 59-item one. The ultimate model is presented in Figure .

Based on this figure the third item (I make sure to take appropriate steps to promote the integrity of the university) from the construct of Commitment to organization, was removed out of the final model of the professional ethics. Besides, the twelfth item (I do my best to be an asset in developing and promoting policies and new trends in the profession) which goes under the construct Commitment to Profession was also removed out of the questionnaire.

Next after this, Cronbach Alpha as well as Composite Reliability were also employed, through PLS-SEM (partial least square variance-based structural equation modeling), to check out the internal consistency of the items of the questionnaire as a whole and the correlation between and among its variables. The advantage of Composite Reliability, a modern way of reliability estimation, over Cronbach Alpha, a traditional way of estimating reliability, is that opposite to Cronbach Alpha, Composite Reliability looks for the extent to which the variables/components of a questionnaire/model correlate with each other i.e. the degree of correlation between and among the variables is of importance in composite reliability. Therefore, in order to come up with a more comprehensive perspective of the reliability index of the questionnaire, both these two means were applied and the results are illustrated in Table .

Table 6. Construct reliability results

For the results of the Cronbach Alpha and the Composite Reliability to stand as verifiable, the index needs to be a minimum of 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2011) and as the outcomes reveal in Table six all the four variables of the questionnaire possess an index of above 0.9 which is greater than 0.7. Consequently, the internal consistency of all the items of the questionnaire and the degree of the correlation between and among the variables of the study are proved as reliable.

As Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt (Citation2014) rightly mentions, “Threats to construct validity stem from various sources, consequently, researchers must employ different construct validity subtypes to evaluate their work and its results” (Henseler et al., Citation2014, p.1). Thus, dealing with the construct validity of the instrument at hand, partial least square variance-based structural equation modeling was once again applied and Convergent Validity as well as Discriminant Validity were opted as the two means of data analysis.

Convergent Validity is mainly used to investigate the correlation between one variable and its items. The results of this kind of analysis through PLS are depicted in the average variance extracted (AVE) column which expresses the shared average variance between each variable and its items. In other words, AVE shows the degree of correlation between one variable and its own items. The results of this analysis for each of the four variables/components of the study are included in Table .

Table 7. Construct validation: convergent validity results

In order for the results to stand as significant in Convergent Validity, the AVE results need to be equal or greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2011). As depicted in the aforementioned table, the AVE index for all the four variables is greater than 0.5, varying from 0.5 to 0.6. Accordingly, the Convergent validity at this level is verified since there exists a significant level of correlation between each of the four variables and their items in an independent way.

The second approach to construct validation in this study was namely as Discriminant Validity. Discriminant validity is considered well when the loadings of the indicator variables on their latent variable is higher than the loadings of that indicator on any other latent variable (Hair et al., Citation2011).

According to Gefen and Straub (Citation2005, p. 92), “discriminant validity is shown when each measurement item correlates weakly with all other constructs except for the one to which it is theoretically associated” (as cited in Henseler et al., Citation2014) . This can also be traced back to exploratory factor analysis approach for validation. Using PLS-SEM, this means that “each indicator loading should be greater than all of its cross-loadings; otherwise, “the measure in question is unable to discriminate as to whether it belongs to the construct it was intended to measure or to another (i.e., discriminant validity problem)” (Chin, Citation2010, p. 671, as cited in Henseler et al., Citation2014).

Discriminant Validity checks out the extent of the relation a variable holds with its own items in comparison to the kind of relation it holds with other variables of the study. This means, in such analyses it is expected that one variable needs to be in greater relation with its own items rather than other variables of the study. The results of this analysis are depicted through a matrix in Table .

Table 8. Discriminant validity results according to Fornell–Larcker criterion

In the matrix presented according to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the square of AVE for each of the four variables is of importance which means, Discriminant Validity is established, because the off-diagonal values signify the correlation between the latent constructs and based on the cross loadings criterion, the discriminant validity between all the constructs is well verified. As a concluding point, it can be asserted that the chosen measurement model well fitted the data.

Finally, the construct validation and reliability of the presented model was proved and the model designed by the researcher revealed significant relations i.e. the constructs of the model possessed an index of above 0.20 (varying between 0.30 and 0.70). Therefore, the construct of Commitment to Learners possessed a significant relation with Commitment to Profession. Commitment to profession revealed a significant relation with Commitment to Organization and last, Commitment to Organization possessed a statically significant relation with commitment to Society. This means, the collected data from EFL instructors and the suggested model by the researcher reveal the fact that professional ethics to EFL university instructors is more highlighted from very within (their learners and themselves) moving toward being less highlighted and significant when it comes to the construct of society. This is because as illustrated in Figure , the construct of society does not bear any relations with other constructs of professional ethics.

4. Discussion & conclusion

To conclude, all the data analysis procedures adopted throughout the qualitative all stood out for the importance these instructors attached to the kind of responsibility and commitment they have toward their learners and their profession respectively. However, when it came to their understanding of the kind of commitment they needed to have toward their society and toward the organization they were working for, almost no significant responses were accumulated. This fact calls for some instructional, as well as awareness-raising programs regarding the other two aspects of professional ethics in teaching (commitment to organization and commitment to society). Therefore, enriching the current study, a model of code of professional ethics for EFL university instructors was postulated through PLS-SEM (Figure ). The kind of relationships presented among the constructs of the model was also re-approved by the outcomes of the qualitative data analysis of the study. This means, as illustrated through the qualitative and the quantitative phases, Iranian university instructors’ understanding of professional ethics in teaching, embraces at its heart the kind of responsibility and commitment they feel they have toward their learners, to whom they devote most of their worries, energy, time, efforts etc., and on the other hand, stands the society as the least important concept they find themselves attached to! Because as depicted in Figure , the component of Society did not bear any relations with other constructs of the study.

Seems the fact that learners of our classrooms, who are the members of the society to which they will soon return, is dramatically missing in the process of pursuing professional ethics in teaching! This lack of priority and importance to organization and society has also been highlighted in other similar research findings (Ashraf, Hosseinnia & Domsky,Citation2017; Salehnia & Ashraf, Citation2015) All in all, the results of this study, similar to some other, highlight the fact that “Society’s desperate need for an ethical culture is every organization’s opportunity to influence social culture, through the institutionalization of ethical values. When this occurs, communities benefit from the positive influences employees take from their workplace back to families, friends and associates” (Brimmer, Citation2007, p. 3).

Reflecting on all the already discussed, it seems even more crucial than ever before, to consider ethical foundations in all and any educational context specifically universities which are considered as the birth place of novel thoughts as well as societal relations. This is even more of a necessity in EFL contexts which have very recently been in touch with the notion of ethics. The need for this action to be taken has also been highlighted by researchers including Strike & Ternasky (1993) who claim, “education to date it seems, has neither deliberate and systematic instruction in ethics nor an enforceable code of ethics” (p. 3) and perhaps it is time to take measures to change this current trend (as cited in Campbell, Citation2000, p. 19).

Codes of ethics can be assumed as one of the best practical ways of providing teachers with the right intuition about how to approach various ethical concepts which might be relevant to students, colleagues, the organization or even the society. All this is needed cause as Campbell (Citation1997) stresses, “professionals’ sense of moral agency does not inevitably emerge as a result of their training and education, but instead needs to be developed in a deliberate way through the teaching of ethics to teachers” (as cited in Freeman, Citation2000, p. 6) and the presence of a professional ethics code can be one such deliberate ways of raising teachers’ awareness of ethical codes and their principles in education. Therefore, establishing a code of professional ethics can guide practitioners as they navigate a broad range of gray areas because as future educators, teachers, by the very nature of their jobs face a constant series of gray areas with only their personal experience and values as a guide!

All in all, the results of this study could be of great benefit for ministry of higher education as well as those who have a role in providing materials and the basis for ethical guidelines at universities. They can think of new codes of professional ethics in which the importance is equally given to all the four components of professional ethics and not only highlighting the responsibilities teachers have toward their learners and their profession. Besides, careful attention and awareness is also deemed necessary on the part of EFL university instructors as the ones who have to be well aware of ethical guidelines at first place and then try to put them into practice in their daily teaching life so as to train future ethical-sensitive teachers for the society. This issue has also been put forward by Gluchmanova (Citation2015), who believes “teachers at all levels of education should ensure the cognitive, intellectual and moral progress of their students and show them appropriate respect and appreciation” (p. 4). Besides all the above mentioned, there exists the need for holding varied sessions in which professional ethics, its concept at the level of universities and higher education, and its potential positive effects on EFL educational system be explicitly taught and teachers be well trained in the realm of ethics in education! This will help up to a great deal to gain professional solidarity in organizations and within and among individual teachers.

5. Limitations and future research directions

Among the limitations which were imposed on this study is the widespread applications of ethics in all fields of study. However, the scope of this research centered on the angle of professional ethics which deals with university instructors. Consequently, future studies can focus on whether teachers at private sectors such as language schools also hold the same world view about ethics in teaching or not. Moreover, this study was carried out based on the perspectives of English as foreign-language teachers, therefore, another interesting aspect of further research in this regard could be to shed light on whether university instructors of different fields of study hold similar or different perceptions of professional ethics in teaching compared to EFL university instructors. Additionally, drawing a comparison regarding the perception of professional ethics between university chancellors and university instructors which can stand as another practical area of investigation in this regard.

Shedding light on the pedagogical implications of this study which is of benefit for different members of different academic settings, one can assume varied aspects which might relate to three sectors of “teachers, training bodies, and policy-makers”.

Talking about policy-makers, when preparing and deciding about the missions and future visions of organizations in particular and societies in general, they need to invest some of their budget, resources and attention in ethical concepts embedded in educational contexts. Additionally, the results of this study could be of great benefit for ministry of higher education as well as those who have a role in providing ethic-related materials and the basis for ethical guidelines at universities. They can think of new codes of professional ethics in which the importance is equally given to all the four components of professional ethics and not only highlighting the responsibilities teachers have toward their learners and their profession.

With regard to teachers, ethically educated teachers in the realm of professional ethics seem an urgent need at universities. Researchers including Maxwell and Schwimmer (Citation2016) stand up for the same factor by saying that “the act of teaching is moral” in the sense that education inevitably involves attempting to transform people in ways that are considered to be good or worthwhile and that “teaching is necessarily as much about transmitting values and social ideals as it is about transmitting knowledge and skills” (p. 354).

Last, this study can be of help for training bodies. There exists the need for holding varied sessions in which professional ethics, its concept at the level of universities and higher education, and its potential positive effects on educational systems be explicitly taught and teachers be well trained in the realm of ethics in education! This will help, up to a great deal, to gain professional solidarity in organizations as well as within and among individual teachers. The importance of this need is also pinpointed by Maxwell and Schwimmer (Citation2016) who wrote that preparing future teachers to assume the role of moral models for their students has been a primary concern of teacher education in Europe and North America from the beginning of formalized teacher education. They also maintained saying that from 1980s onwards “a renewed prioritization of the ethical and moral dimensions of teaching in teacher education has been urgent” (p. 2).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zeinab Kafi

Zeinab Kafi is a PhD candidate in TEFL, at Islamic Azad University of Torbat-e-Heydarieh, Iran. Her research interests mainly center on language teaching/learning approaches and methodologies, effective teaching and learning, teachers’ professional development/behavior. She also takes interest in areas relevant to sociolinguistic aspects of teaching and learning.

Khalil Motallebzadeh

Khalil Motallebzadeh is an associate professor at the Islamic Azad University of Torbat-e-Heydarieh and Mashhad Branches, Iran. He is a widely published researcher in teacher education, language testing and e-learning. He is also an accredited teacher/master trainer of the British Council since 2008. He has represented Iran in Asia TEFL since 2009.

Hamid Ashraf

Hamid Ashraf, PhD in ELT from University of Pune (India), has been a member of faculty at English Department, Islamic Azad University, Torbat-e Heydarieh, Iran. He has worked on language testing, critical thinking, and e-learning.

References

- Ahmadi Hedayat, H., Karimi, M., & Saveh, M. (2017). Universities’ components of professional ethics. National Higher Education Congress of Iran.

- Ashraf, H., Hosseinnia, M., & Domsky, J. (2017). EFL teachers’ commitment to professional ethics and their emotional intelligence: A relationship study. Educational Psychology and Counselling, 2(4), 1–9.

- Ashraf, H., & Kafi, Z. (2016). Investigating the notion of demotivation among a community of EFL learners. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 5(2), 116–122.

- Beach, J. (2013). Academic capitalism in China: Higher education or fraud? West by Southwest Press. 978-1482509502.

- Beck, L., & Murphy, J. (1994). Ethics in educational leadership programs: An expanding role. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Billings, J. C. (1990). Teaching values by example. The Education Digest, 56(4), 66–68.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: Sage.

- Brimmer, S., (2007). The role of ethics in 21st century organizations. Leadership Advance Online, 1-7.

- Campbell, E. (1997). Connecting the ethics of teaching and moral education. Journal of Teacher Education, 48(4), 255–263. doi:10.1177/0022487197048004003

- Campbell, E. (2000). Professional Ethics in teaching: Towards the development of a code of practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(2), 203–221. doi:10.1080/03057640050075198

- Campbell, E. (2008). The ethics of teaching as a moral profession. Ontario institute for studies in education. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto.

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. Handbook of Partial Least Squares, pp. 655-690. University of Houston.

- Clarke, M, & Moore, A. (2013). Professional standards, teacher identities and ethics of singularity.Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(4), 487-500.

- Esposito Vinzi, V., Trinchera, L., & Amato, S. (2010). PLS path modeling: From foundations to recent developments and open issues for model assessment and improvement. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 47–82)). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Fazeli, Z., Fazeli Bavand Pour, F., Rezaei Tavirani, M., Mozafari, M., & Haidari Moghadam, R. (2012). Professional ethics and its role in the medicine. The Scientific Journal of Medical Science of Illam, 20(4), 1–6.

- Fitzmaurice, M. (2010). Considering teaching in higher education as a practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(1), 45–55. doi:10.1080/13562510903487941

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312

- Freeman, N. K. (2000). Professional ethics: A cornerstone of teachers’ pre-service curriculum. Action in Teacher Education, 22(3), 12–18. doi:10.1080/01626620.2000.10463015

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the AIS, 16, 91–109.

- Gluchmanova, M. (2015). The importance of ethics in the teaching profession. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 17(6), 509–513. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.504

- Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. M. (2004). A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3, 283–297. doi:10.1207/s15328031us0304_4

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19, 139–152. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hansen, D. T. (2001). Teaching as a moral activity. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 826–857). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- Haynes, F. (1998). The ethical school. London: Routledge.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hostetler, K. D. (1997). Ethical judgment in teaching. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Karami, M., Galavandi, H., & Galaeei, A. (2017). The relationship between professional ethics, ethical leadership and social responsibility in schools. Journal of School Administration, 5(1), 93–112.

- Kidder, R. M. (2001). Ethics is not optional. Association Management, 53(13), 30–32. Retrieved July 18, 2007, from Washington: Dec. 2001 http://proquest.umi.com.eres.regent.edu

- Kipnis, K. (1986). Legal ethics. Prentice-Hall Series in Occupational Ethics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lane, T. (2005). The role of ethics in daily life as we choose between right and wrong. Retrieved from The Blade website, June, 2018.

- Lovat, T. J. (1998). Ethics and ethics education: Professional and curricular best practice. Curriculum Perspectives, 18(1), 1–7.

- Maxwell, B., & Schwimmer, M. (2016). Professional ethics education for future teachers: A narrative review of the scholarly writings. The Journal of Moral Education, 45(3), 354–371. doi:10.1080/03057240.2016.1204271

- Nash, R. J. (1996). Real world ethics: Frameworks for educators and human service professionals. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Rِnkkِ, M., & Evermann, J. (2013). A critical examination of common beliefs about partial least squares path modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 16, 425–448. doi:10.1177/1094428112474693

- Rossman, B. G., & Rallis, S. F. (1998). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Salehnia, N., & Ashraf, H. (2015). On the relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ commitment to professional ethics and their students’ self-esteem. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(5), 135–143.

- Strike, K. A, & Ternasky, P. L. (1993). Ethics for professionals in education: Perspectives for preparation and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Waldo, D. (1956). Perspectives on administration. University, AL: University of Alabama Press.