Abstract

This study sought to examine the extent of contribution of school feeding programmes towards the achievement of the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) policy in countries. Based on a purposive sampling of a deprived rural community in northern Ghana, the study utilised the concurrent mixed method design relying mainly on documentary analysis, questionnaires and interviews as data sources. A sample of 377 participants made up of teachers and parents were drawn for the research. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and qualitative content analysis. The main finding of the study was that the programme had a positive influence on school enrolment and retention which are key indicators of the achievement of the FCUBE policy. Recommendations proffered pointed to the need to extend the SFP to other deprived areas, and to give the programme in Ghana a constitutional backing among others.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study was conducted in a deprived rural community of northern Ghana to find out whether the School Feeding Programme (SFP) introduced by the government has helped the country to get parents to send their children to school and for the children to remain in attendance until completion. It is important for all children in Ghana to attend school because of the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) policy introduced in 1995 with an expected target of achieving universal education by 2005. A total of 377 teachers and parents took part in the research. The main finding of the research was that the SFP caused many children in the community to attend school and made the children remain in attendance until completion. Based on this finding, the researchers recommended that the SFP should be implemented in other deprived areas.

Competing Interest

No conflict of interest.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Formal education has widely been seen as a tool for achieving quality personal life. It has also been considered as a means through which a country can put its human and material resources into usefulness (Janke, Citation2001). Perhaps these advantages explain the reason why every country would like to ensure that all its citizens attain, at least, basic education. However, for most developing countries, the task of ensuring universal education appears to be a difficult one to achieve because of poverty and deprivation which make most parents unable to afford school fees (Alderman & Bundy, Citation2011). Recent trends, however, indicate that a number of social intervention policies and programmes aimed at abolishing fee payment at the basic level of education have been initiated by most developing countries. In Ghana for example, successive governments have initiated various policies and programmes aimed at ensuring that every Ghanaian child has equal access to and participation in basic education. Some of these policies include: the 1951 Accelerated Education Development Plan (ADP), Education Strategic Plan (ESP) for 2003–2005, the Growth Poverty Reduction Strategy, and the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) policy for 1995–2005 (Acheampong, Citation2009).

For the purpose of this paper, attention will be focused on the FCUBE policy because of its relevance to the achievement of some aspects of the erstwhile Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as well as the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries, especially in Ghana. However, before delving into a detailed discussion on the policy, the stage would firstly be set by explaining the nature of basic education in Ghana as a key framing of the title of our research.

Basic education in Ghana is the initial and the first of the three cycles of the educational ladder. It comprises two years kindergarten, six years primary and three years junior high school which sum up to 11 years. It is currently considered a terminal stage. Students write an external examination called Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) at the final year after which they may continue to pursue a three-year senior high or technical education (second cycle) which is also considered terminal. Moving up the ladder, a four-year university (tertiary) education is the third cycle and the final stage.

Turning attention now to the FCUBE, the policy was introduced in Ghana in 1995 with an expected target of achieving universal education by 2005 (Acheampong, Citation2009). The policy is necessary as it makes access to basic education in Ghana a right for all citizens irrespective of gender, geographical location, religion or ethnic background. Its legal backing is enshrined in the country’s constitution which states that:

All persons shall have the right to equal educational opportunities and facilities and with a view to achieving the full realisation of that right, basic education shall be free, compulsory and available to all (Constitution of the Republic of Ghana, Citation1992).

Since the inception of the FCUBE policy in Ghana in 1995, various strategic initiatives have been introduced in order to successfully implement it as follows: Capitation grant (a fee abolishment policy of the Ghana Government in which every public primary school receives monetary allocation per pupil enrolled per year), expansion of Early Childhood Development Services (ECDS), promotion of measures to improve gender parity in primary schools, and School Feeding Programme (SFP) (Agbenyega, Citation2008; Osei, Owusu, Asem, & Afutu-Kotey, Citation2009; Osei-Fosu, Citation2011).

The contributions of all the above enumerated implementation initiatives to the success of the FCUBE policy are worth considering. However, since it is not possible to capture all of them in a single write-up because of journal word limit, the scope of the research has been narrowed down to assess only the contribution of the School Feeding Programme (SFP). The SFP is one of the major FCUBE implementation initiatives through which the Government of Ghana provides food to children in primary schools in poor and deprived communities in order to increase enrolment and retention. In the context of this research, enrolment refers to participation in basic education by Ghanaian children. Retention also refers to a situation where the enrolled children remain in school until they complete the basic education level.

The choice of the SFP was informed by the seemingly many issues and controversies (e.g. corruption) bedevilling its implementation (Levitsky, Citation2005; Martens, Citation2007; Nuako, Citation2007; Ohene-Afoakwa, Citation2003). Besides, it appears to be the initiative which currently receives the most political attention with funding sources coming from both the local government and international organisations. For example, locally, the SFP receives budgetary allocations from the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and the District Assembly Common Funds (DACF) (Ministry of Education, Citation2006; Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, Citation2005). Internationally, the SFP has also attracted many donations and aids from the World Bank, the World Food Programme (WFP), Partnership for Child Development (PCD), United Nations International Children Emergency Funds (UNICEF), Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Netherlands Development Organisation (SNV) and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) (Martens, Citation2007; Nuako, Citation2007).

Despite all the huge investment made in the programme in recent times, it appears there is very little to show about its effectiveness so far as an implementation initiative for the FCUBE policy. This situation might have arisen because of the absence of sufficient coverage on it in the literature which has tended to examine the FCUBE policy only in terms of a historical perspective (e.g. Acheampong, Citation2009). Meanwhile, given that the programme has received much attention and financial support, it is important that adequate research information is available for policy makers and interested academics to assess its performance in bringing about the achievement of universal basic education in the country. Focusing on a deprived rural community in the northern part of Ghana where the impact of the FCUBE policy is supposed to be felt tremendously because of poor households who can hardly afford school fees of their wards (Acheampong, Citation2009), The preoccupation of this research was to explore how the SFP, as one of the implementation initiatives of the FCUBE, has contributed in making the FCUBE policy achieve its desired results.

1.2. Research purpose and objectives

This research was to assess the level of contribution of the School Feeding Programme (SFP) towards the achievement of the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) policy in Ghana. Specifically, the research was to find the extent to which the SFP has brought about increases in enrolment targets in deprived community schools as a pivotal target of the FCUBE policy. The second was to uncover whether or not the SFP has brought about any significant increase in retention of pupils in those deprived schools as another crucial target of the policy. The last issue the research sought to find was any challenge(s) bedevilling a successful implementation of the School Feeding Programme in the deprived community schools.

1.3. Research questions

In line with the objectives, the following questions were posed:

To what extent has the School Feeding Programme increased enrolment in deprived community schools?

How has the School Feeding Programme increased retention of children in deprived community schools?

What is the nature of the challenge confronting the implementation of the School Feeding Programme in deprived community schools?

2. A review of the literature

2.1. Theoretical framework: Maslow’s theory of need

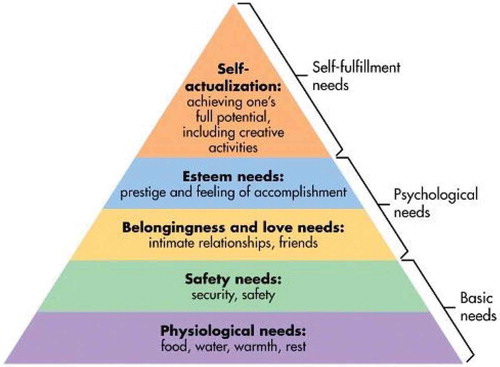

The theoretical framework in Figure is a humanistic view of motivation based on Abraham Maslow’s (Citation1943, Citation1954) theory of need. The framework is appropriate to the research because it enables the researchers to theorise the needs of school children (e.g. food, shelter, security, love, etc.) from a humanistic point of view, and to make sense of how the SFP could bring about an achievement of those needs.

Figure 1. Source: (McLeod, Citation2016), p. 1

The theoretical framework argues that all human beings (including school children) have common needs which affect their lives. These needs are represented in a hierarchy of five main levels. At the bottom are basic, fundamental or physiological needs such as food, water, shelter, clothing and rest. In Maslow’s view, these needs are basic because without them no human being can continue to live. From the bottom, the next level (second) on the pyramid is safety and security needs. Moving up to the third level is the dimension of psychological needs called belongingness and love needs. These needs manifest in people’s quest for acceptance, love, intimate relationship and group identification.

Featuring at the fourth level is the second dimension of psychological needs known as esteem needs. They refer to feelings of recognition and respect within a person’s society. The fifth and final level of the pyramid has actualisation needs (self-fulfilling needs). This level refers to a point in life when people feel they have achieved their ultimate or full potential.

2.2. The school feeding programme from a historical perspective

The School Feeding Programme (SFP) in Ghana is one of the FCUBE implementation initiatives through which the Government of Ghana provides food to children in primary schools in poor and deprived communities in order to increase enrolment and retention. A review of the literature about the School Feeding Programme provides an important theoretical basis for this study.

School feeding started in the 1930s in the developed world, particularly in the United Kingdom and the United States as an intervention aimed at improving the growth of school children (Gleason & Suitor, Citation2000). In the United Kingdom, for example, the programme was implemented as subsidised milk for school children in 1934 and continued until 1944. It was, however, reviewed between 1960 and 1970 to provide for only needy children (Alderman & Bundy, Citation2011; Gelli & Daryanani, Citation2006)).

In Africa, documentary evidence (Buttenheim, Alderman, & Friedman, Citation2011; Mayaki, Citation2015) has revealed that school feeding was first introduced in South Africa in the early years of the 1940 with a similar implementation style of supplying free milk but exclusively to white children in white schools (Buttenheim et al., Citation2011; Suresh & Anne, Citation2015). In South Africa, the scope of the programme was subsequently broadened to include the provision of biscuits or full meals but again, only to white children in white schools (Buttenheim et al., Citation2011).

The School Feeding Programme (SFP) was later replicated in other African countries such as Malawi, Uganda and quite recently, Ghana (Baker, Elwood, Hughes, Jones, & Sweetnam, Citation1978; Essuman & Bosumtwi-Sam, Citation2013). Based on specific objectives, Bennett and Strevens (Citation2003) have classified the SFP into five namely; school feeding as an emergency intervention, as a developmental intervention to aid recovery, as a nutritional intervention, as an improvement on child cognitive development, and as a short and long term food security. In the implementation SFP, school children are provided with free breakfast and snack or lunch. The meals afford the school an opportunity to get its community interested in its activities (Essuman & Bosumtwi-Sam, Citation2013).

2.3. Justifying the school feeding programme in Ghana

Iddrisu’s (Citation2016) research conducted in Tamale, the capital town of the Northern Region of Ghana, to find the importance of the School Feeding Programme revealed that, through the implementation of the Programme in many basic schools, enrolment and retention increased in the area. Kristjansson et al. (Citation2007) (NB: “et al.” has been used in this first time citation because the authors are seven) also conducted a comparative study of Kenya and India and similarly found that the SFP reduced dropout in schools by a quarter and one-fifth in the countries respectively. Corroborating Iddrisu and Kristjansson et al.’s finding, Osei-Fosu’s (Citation2011) research also revealed that the SFP has caused enrolment increases in many implementing countries implying that, a 100% increase in the SFP may cause a corresponding increase in retention by about 99%.

Lending credence to the findings above, other research sources (e.g. Jacoby, Citation2002; Sally, Grartham-McGegrregor, Chang, & Walker, Citation2015; World Food Programme, Citation2006) evinced that hunger and malnutrition affect cognitive abilities of children, reduce school attendance and educational outcomes. Recent developments further show that chronic protein–energy malnutrition both in the past and in the present reduces cognitive growth, and short-term hunger brings about poor concentration and low educational outcomes (Bennett & Strevens, Citation2003). Malnutrition among pre-school children in Ghana has been found to be on the ascendency evidenced in 30% of the children being severely malnourished and drop out of school because of illness (Nuako, Citation2007; Ohene-Afoakwa, Citation2003). Considering this revelation, it becomes apparent that the SFP should be a necessary part of the early childhood education programme in order to serve as a means of enhancing nutrition among school children as well as improving school attendance and educational outcomes.

2.4. Structure of the school feeding programme in Ghana

The current structure of the SFP in Ghana has three levels namely; national, regional, district and local levels. At the national level is the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, Programme Steering Committee (Board) and the SFP National Secretariat. The SFP National Secretariat is the co-coordinating body of the programme and it is supervised by the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

At the regional level, the SFP is composed of regional coordinators and monitors. The regional level serves as an intermediary between the District Assembly and the national in order to facilitate the effective implementation of the programme at the local level. The district level of the SFP is also composed of an implementation committee chaired by the District Chief Executive (DCE) and district SFP desk officer. The last is the local level which is also composed of the school implementation committee chaired by Parent Teacher Association (PTA) representatives who oversee the implementation of the SFP in collaboration with head teachers and a representative each from management committees and traditional rulers in their respective schools.

2.5. Criteria for selecting beneficiary districts and communities of the school feeding programme

From a documentary study, almost all the SFP selected their districts based on the following criteria: deprived districts (according to the Ghana poverty reduction strategy classification), poorest and most food insecure district, low pre-school and school enrolment district, low literacy level (Ghana Government Report on the SFP, Citation2006). Beneficiary communities are also selected based on the following: low attendance rate (i.e. high absenteeism), low school enrolment, high school drop- out rates, high communal spirit, high community management capability, increased utilisation of diversified balanced local diets and judicious management of the environment (Ghana Government Report on the SFP, Citation2006).

2.6. Challenges confronting school feeding programmes

School feeding programmes worldwide have encountered myriad of setbacks hampering their implementations in many developed and developing countries. Among the challenges cited in the literature include corruption such as: award of contracts to non-existent companies, the disappearance of funds allocated to programme management and the deliberate purchase of unwholesome cheaper ingredients and foodstuff for the schools. In Ghana, a challenge bedevilling the implementation of the SFP is political influence where it is alleged unqualified caterers are often given contracts because of their political affiliations (Atta, Citation2007).

2.7. Summarising the literature and locating the gap

The extant literature reviewed has highlighted scholarly information on the global history of the SFP including the rationale, structure and implementation challenges. Conspicuously missing, however, is coverage on the contribution of the programme to the achievement of the FCUBE as major national policy. In Ghana, this vacuum in the literature is a major concern because of the country’s quest to meet its Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) through increased enrolment and retention of children at the basic school level. It is therefore a timely effort to conduct a research that investigates the contribution of the SFP towards the achievement of the FCUBE, and this is what the current research sets out to do in order to fill the knowledge gap.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach and design

This research adopted the mixed method approach relying specifically on the concurrent design. The design allowed a prioritisation of both the quantitative data and the qualitative data, and their collection was done simultaneously (Creswell, Citation2009). On the one hand, the quantitative part of the research was a cross sectional survey which was chosen so as to be able to make a generalisation based on a representative sample of the population (Creswell, Citation2009) of all SFP beneficiary schools in the study area. The qualitative aspect, on the other hand, was conducted as a single case study to provide the basis of engaging in an in-depth enquiry to unpack, understand, describe and interpret the views of participants (Merriam, Citation2000) regarding the contribution of the SFP to the successful implementation of the FCUBE policy in Ghana.

3.2. Sampling

The target participants for the study were teachers and parents in all the SFP beneficiary communities in northern Ghana. Three sampling techniques (modal purposive, simple random and accidental sampling techniques) were used to select participants for the survey part of the research.

Modal purposive sampling was the first technique used to select the Upper East Region in the northern part of the country because of its record as one of the poorest regions with the highest illiteracy rate (78.1%). The rate has been considered even higher than the national average of 45.9% illiteracy rate (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2010; Index Mundi, Citation2016). Again, the same sampling technique was used to select one out of the 13 districts of the region namely; Bawku West District. The choice of the district was informed by its social demographic as the most deprived rural community in the region (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2010).

The second selection technique used in the survey research was the simple random sampling procedure which was also used to select only teachers in the community (district). It was chosen because of the aim to arrive at a representative sample of the population of the teachers in the community numbering 682, according to the desk officer of the Education Management Information System (EMIS) at the Bawku West District Education Office. Based on the technique, 310 participants were selected out of the 682 teachers in accordance with Krejcie and Morgan’s (Citation1970) standard procedure for determining a sample size. The selection was done using the “blind draw” method suggested by Burns and Bush (Citation1995). The technique enabled us to blindly choose the participants from an alphabetical list of teachers in the community obtained from the District Education Office.

The third sampling procedure used in the survey was the accidental or haphazard technique. The technique also enabled the researchers to select a total of 67 literate parents they came across and were prepared to take part in the research. In all 377 participants (i.e. 310 teachers and 67 parents) were used for the survey.

For the qualitative case study, the expert purposive sampling technique was used to select three head teachers among the 377 teacher participants to take part in individual face-to-face interviews. They were chosen because their schools were the pioneers of the SFP. It was therefore the researchers’ belief that they were key informants with better knowledge and experience of how the programme promoted retention of children at the basic level of education in the district.

3.3. Ethics

In line with ethical standards, the participants were briefed on the nature of the research and their written consent was sought and achieved prior to the commencement of the research. Participation in the research was therefore voluntary and the participants had the choice to withdraw at any stage of the research. The participants were also assured of anonymity. In place of institutional ethical clearance, the researchers applied and obtained written permissions from the Upper East Regional Director of Education as well as the Bawku West District Director of Education. During analysis of the qualitative data, the researchers used anonymous coding in order to ensure that participants’ identities were concealed.

3.4. Instruments

Three instruments (documentary analysis, questionnaire and interview schedule) were utilised in the research for field data collection. Starting with the documentary analysis, archives on enrolment statistics of schools covering periods before and during the implementation of the SFP were accessed from the Education Management and Information System (EMIS) unit of the district education office of the study area.

Two sets of researcher-developed questionnaire were the second instrument used. The first questionnaire which was used for the first survey had one structured open-ended question seeking to find the causes yearly increase in school enrolments. The second questionnaire which was rather used for the second survey had seven close-ended items seeking information on the extent of the contribution of the School Feeding Programme in enrolment increases in beneficiary schools. All the items were designed according to authoritative views expressed in the literature.

Because the questionnaires were both researcher-developed, they were piloted to find reliability and validity. A combination of 126 parents and teachers outside the study area were used for the purpose. A Cronbach’s alpha test conducted revealed reliability coefficients of .89 and .78 for the first and second pilots respectively. Face validity tests also conducted to measure the precision of both questionnaires in covering all the domains of the research objectives showed positive results.

The third type of instrument used in the research was an unstructured open-ended interview schedule with questions framed according to views expressed in the literature. It was used for the qualitative case study in which three school heads that started the SFP in the district were interviewed.

3.5. Data collection and analysis

Data collection for the quantitative part of this research was done via documentary analysis and questionnaires. The document analysis enabled the researchers to consult with archives to obtain quantitative data on school enrolments in the district. Using the questionnaire as a data source also lasted for 14 days. Participants were contacted face-to-face and personally given the questionnaires to complete because our belief that doing so would bring about the anticipated co-operation, at least, better than commissioning others to assist in that direction.

With the aid of SPSS version 2.0.0.0., the collected data were analysed descriptively applying measures of central tendencies and measures of dispersion. As part of the analysis, the responses to the item in the first survey questionnaire were ranked using descriptive statistics. In the case of the second survey questionnaire, the items were coded according to a five-point Likert scale in the following order: Strongly Agree – 5; Agree – 4; Neutral – 3; Disagree – 2; Strongly Disagree – 1. They were also analysed descriptively.

Data collection for the qualitative part was done using individual in-depth interviews. Each interview session was done face-to-face lasting for 35 min. Because the researchers were concern about ensuring rigour and trustworthiness in the collection process, they engaged in reflexivity prior to the collection. The reflexivity made it possible to assume the outsider position which later helped to analyse the data from the perspectives of the interviewees rather than doing so from the researchers’ perspective. After collecting the data, an audit trail was also conducted including peer debriefing and member check which were also organised when the research report was ready. The qualitative data were coded anonymously and analysed inductively using content analysis.

4. Results

This section presents the analysis of the field data obtained from the three instruments (documentary analysis, questionnaire and interview schedule). The data were analysed separately because they were in different forms. Tables and present the quantitative data obtained through documentary analysis and questionnaire respectively. The qualitative data, however, is being presented in participant quotes.

Table 1. Enrolment levels of pupils before and after the SFP implementation

Table 2. Participants’ views on causes of school enrolment increases

4.1. The quantitative data

Table provides details of enrolment statistics of all beneficiary schools of the SFP in the study area numbering 21. The data were obtained from the Management Information System (MIS) unit of the District Education Office. The SFP was introduced in the area in the 2004/2005 academic year (see asterisked and highlighted academic year in the table). The enrolment figures covered the period 1994/1995 academic year (i.e. 10 years prior to the introduction of the SFP in 2004/2005 academic year) up to 2016/2017 academic year.

It is evidenced from the table that generally, there were significant increases in the enrolment figures year after year, right from the academic years prior to the implementation through to the 2004/2005 academic year when the implementation began. The trend continued to the 2016/2017 academic year when data were collected for this research, thus making it difficult to pinpoint a single issue that could be responsible for the enrolment increases. There was therefore the need to conduct further investigations to find out the underlying issues.

Analysis of the enrolment records from the District Education MIS of the study area indicated that school enrolments in the beneficiary schools had yearly increases even before the introduction of the SFP implying that there were other latent competing issues to be uncovered. It therefore became necessary to conduct a further investigation to find out those issues, and whether or not the SFP was the most influential factor among them. A first quantitative survey was conducted as a follow-up for the purpose using one structured open-ended item: “Please name all the factors you think are responsible for the reasons why parents are now more willing to take their children to school than before”. Table presents all the responses to the item, which have been ranked descriptively from the highest to the lowest. From the table, “SFP” had the highest, being cited by almost all the participants (369) representing 97.9% as compared to “proximity of schools to households” which had the lowest being cited by only 21 participants representing 5.6%.

The second questionnaire seeking to measure the extent of the influence of the SFP on school enrolment was used for the second survey. Table presents a summary of the results in mean scores and standard deviation. All the 7 variables on the table were designed according to what was found in the literature, and featured in section “B” of the questionnaire for participants to indicate their responses according to a five-point Likert scale (see section on “Instruments”). Interestingly, none of the participants provided any responses outside what were provided them, perhaps, because the instrument captured all that were required.

Table 3. The Extent of the influence of the SFP on school enrolment

A close look at only the extreme measures of the means (i.e. the variable with the highest mean and the variable with the lowest mean) reveals that while the participants’ responses for the variable on whether school admission seeking had been rising with the introduction of the SFP has the highest mean score (m = 4.65) indicating a skew towards the strong agreement scale, responses for the variable on whether the SFP should be abolished when school enrolments in deprived communities increased has the lowest mean score (m = 1.68) showing a skew towards the disapproval scale.

In the case of the measure of dispersion, an examination of the table shows two extreme measures of standard deviations (i.e. the most dispersed variable from its mean and the least dispersed variable from its mean) indicating that responses for the variable on the need to improve the SFP in order to attract more children to school are the farthest apart and most dispersed (SD = 1.66). On the contrary, responses for the variable on whether the SFP should be extended to all communities in Ghana to increase school enrolments are the closest and least dispersed (SD = 0.50).

4.2. The qualitative data

The qualitative data were generated through a case study involving three head teachers who took part in face-to-face individual interviews. The interviews enabled the researchers to get the participants’ views on school retention. The researchers began with the head teacher of School “A”. The researchers sought to find out from the interviewee whether the introduction of the SFP in school had brought about any noticeable reduction in pupils’ absenteeism, lateness, truancy and drop out. The head teacher responded in the affirmative claiming the programme had made many children regular at school and punctual for breakfast in the morning and lunch in the afternoon prior to the end of classes. The interviewee added that the programme had “…motivated many parents to allow their children to regularly come to school because the burden of providing food is taken off their heads”.

When the researchers went further to enquire whether any pupil had left school within the last six months, the interviewee did not mince words and asserted that “… because they (pupils) get food to eat at school they don’t drop out, they rather continue to be in school till completion; healthy development I’m happy about”.

The next participant interviewed was the head teacher of School “B”. This head teacher’s responses revealed a similar line of thought about the influence of the SFP on pupils’ continuous stay in school. For instance, when the researchers wanted to know whether taking meals at school by pupils had anything to do with attendance, the head teacher released a loud breath (perhaps indicative of a deep concern for the programme) and intimated that “the School Feeding Programme has significantly reduced absenteeism, truancy and has instilled in many of my pupils the joy for education.”

The next question put before the interviewee was “could you tell us how many pupils have dropped out of school since this feeding programme started?” Responding, the participant said:

I’ve on record only two incidents of school dropout. And it happened because they were girls who became pregnant….This situation doesn’t compare to those years when many parents preferred to take their children to farms to bring food home instead of taking them to school.

This head teacher appeared very passionate about girls’ education. This was apparent in the way the interviewee expressed joy seeing many girls going to school instead of playing truancy only to be married off to older men who often promise their parents four cows as dowry. In the view of the head teacher, such girls “…become pregnant at a very tender age and mess up their lives.”

The third and final person who attended the researchers’ interviews was the head teacher of School “C”. This head teacher claimed that the programme was not as effective as it began because “the caterers are not paid on time” The head teacher added that the quantity of food served in his school did not suffice his pupils. The researchers also learnt from the head teacher that sometimes the food served the children was not well cooked and affected the pupils’ health. The interviewee concluded expressing the fear that “gradually most of the children who come to school because of food may lose the joy for school and have interest waned and fall out”.

Expressing further pessimism, the head teacher indicated that, although the SFP was a laudable intervention package aimed at bridging the gap between rich and poor communities in Ghana in terms of education access, it was confronted with many challenges because:

…in many homes of this community, child do not get breakfast and dinner and so they become hungry at mid-night and in the following day. As early as six ‘o’ clock such pupils come to school with the hope of getting breakfast. They are often disappointed because the caterers do not turn at all or report late to cook. Hunger compels the pupils to sleep in class. If a child comes to school and feels hungry and depressed, would he come the next day for you to achieve retention?

Having posed this rhetorical question in the concluding remarks, the researchers sought to find out what the interviewee thought was the nature of the challenge impeding the SFP and the way forward. The interviewee paused for some time to get composed in an after-thought claimed that:

…the political element in this school feeding package needs to be tackled by the government. Also, caterers who receive their contracts money and yet refuse to turn up for duties to cook for these poor kids have to be sanctioned. Also, if the government doesn’t have enough money to pay more for an increase in quality and quantity of the meals served in schools, it (the government) should seek assistance from philanthropic organisations and individuals.

5. Discussion

This section examines and makes sense of both the quantitative and qualitative results in light of the contemporary literature and the theoretical framework. To start with, the first research question asks: To what extent has the School Feeding Programme increased enrolment in deprived community schools? In order to provide responses to this question, two surveys were conducted and results presented in Tables and . Generally, the results point to a positive influence of the SFP on enrolment in the beneficiary schools of the community and this was important in the achievement of the FCUBE policy in Ghana.

A perusal of the results obtained from the first survey (see Table ) in terms of the measure of central tendency gives an indication that the participants were generally optimistic about the SFP in Ghana and had evidently affirmed that school enrolment had increased through the programme. However, despite the overwhelming affirmations, relativities on the table show that some variables have superior responses to others. For example, the SFP is the most cited cause of school enrolment increases. The second survey results (see Table ) show a general positive attitude of the participants towards the SFP as the participants were very interested in seeing an improvement in its implementation rather than a discontinuation.

The second research question asks: How has the School Feeding Programme increased retention of children in deprived community schools? Face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted on individual basis and the responses generated qualitative results. A summary indicated that, through noticeable reduction of pupils’ absenteeism, lateness, truancy and drop out, the SFP increased retention of children in the beneficiary schools of the study area.

Situating the research within the contemporary literature reveals that the findings to the first and second research questions are consistent with those of some previous studies. For instance, the results show that the SFP has increased school enrolment and retention in the study area. This finding appears to validate a key finding of Iddrisu’s (Citation2016) research which claimed that school enrolment and retention have been on the increase in Tamale, the capital town of the Northern Region of Ghana. Outside Ghana, Kristjansson et al.’s (Citation2007) comparative study of Kenya and India similarly observed that due to the implementation of the SFP, dropout in schools have fallen by a quarter and one-fifth in the countries respectively. In another development, Osei-Fosu’s (Citation2011) also noted that the SFP has increased enrolment in many implementing countries, and in his view, a 100% increase in the SFP may cause an increase in retention by about 99%.

The third and final research question asks: What is the nature of the challenge confronting the implementation of the School Feeding Programme in deprived community schools? The response this research found to this question is that the SFP has been saddled with implementation difficulties relating to cronyism, delay in the release of funds and non-payment of caterers among others. Similar findings have been documented in the literature where Atta (Citation2007) averred that award of contracts to non-existent companies as well as disappearance of funds allocated to school feeding programmes in many implementing countries are among several other challenges that have affected the sustenance of the programmes. From the need theoretical point of view, one would argue that engaging in any act that would jeopardise the SFP, thereby denying school children access to basic food requirement amounts to a violation of their right to existence.

By applying Maslow’s (Citation1943, Citation1954) theory of need to these important results, it becomes obvious that school children like all other human beings have basic needs without which they cannot live let alone enrol and maintain school attendance. The implication here is that, children from poor and deprived rural communities like those in Bawku West District can only be in school if their parents provide them with food. Since their parents are constrained by financial difficulties and are unable to do so, the government and other organisations interested in education may only ensure the children participate in school by providing their basic needs especially food while in school. The provision of food to these children may have a positive outcome of making them safe from all forms of ill-health emanating from hunger and deprivation (Maslow, Citation1943, Citation1954). A further theorisation of the results from the perspective of the Theory of Need makes an obvious case that giving food to the children in school may enable them enjoy the right of belongingness as citizens of Ghana. It may also mean the country cares about them and are loved. The achievement of this unalienable right is what Maslow (Citation1943) has described as psychological needs of human beings.

6. Summary and limitations

The discussion of results focused on the three research questions posed in the introduction section of this paper. The main finding of the research was positive as it revealed that the SFP increased both basic school enrolment and retention in the selected beneficiary community. A contrary finding, however, indicated that the viability of the programme was threatened by numerous challenges bordering on corruption. The fact that the SFP exerted an important influence on school enrolment and attendance is healthy development because both factors are key indicators of the achievement of the FCUBE. It is, however, important to state that the research is limited in the capacity to generalise for the entire population of SFP beneficiary communities in Ghana because of the purposive sampling technique used in selecting only one beneficiary community. Also, because the survey data were interpreted using only descriptive statistics the external validity of the research may be affected.

7. Conclusion and recommendations

Despite the limitation, the findings on the whole may serve as a useful guidance for policy direction regarding the successful implementation of the FCUBE policy in Ghana since the selected community for the research shared very similar characteristics with other beneficiary communities. Furthermore, the use of Maslow’s theory of need in the discussion of results provided the basis of theorising the needs of the school children from a humanistic point of view while making sense of how the SFP contributed to an achievement of those needs. This is a unique effort and arguably credits the research with making an original contribution to the body of knowledge on school feeding.

Based on the conclusion, the following recommendations are made: Firstly, the SFP should be extended to other deprived areas not covered. Secondly, a legislative backing should be given to the programme to compel the country to extend the programme to cover all basic schools in the country. Also, infrastructure provision should be increased to accommodate the growing number of pupils. Furthermore, there should be a policy enactment that would ensure high quality teaching and learning, attractive conditions of service for teachers and effective supervision at the basic education level. Finally, the programme should be devoid of political interference and cronyism in the appointment of caterers and supervisors so that only qualified persons would handle it.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.1 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed here http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1509429

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Inusah Salifu

Dr Inusah Salifu is a lecturer at the Department of Adult Education and Human Resource Studies, University of Ghana. His research interests are in teacher professional development, educational administration/management/leadership, special needs education, psychological basis of teaching and learning and mixed method research approaches.

John Kwame Boateng

Dr John Kwame is a Senior Lecturer and Head of Department of the University of Ghana Learning Centres. His research interests include instructional supervision and management, and the integration of e-learning into traditional Adult Education programme in Ghana.

Salifu Sandubil Kunduzore

Mr. Salifu Sandubil Kunduzore is a professional teacher with several years of teaching and administrative experiences. Mr Kunduzore holds a Master of Arts Degree in Educational Leadership. His research interest is in Educational Administration and Leadership. He is currently an Assistant Director in-charge of supervision at the Education Directorate of the Bawku West District in Ghana.

References

- Acheampong, K. (2009). Revisiting Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) in Ghana. Comparative Education, 45(2), 175–195. doi:10.1080/03050060902920534

- Agbenyega, J. S. (2008). Development of early years policy and practice in Ghana: Can outcomes be improved for marginalised children? Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 9(4), 400–404. doi:10.2304/ciec.2008.9.4.400

- Alderman, H., & Bundy, D. (2011). The food security and nutrition network. The World Bank Research Observer, 26(2), 1.

- Atta, A. R. H. (2007, September, 25). The school feeding programme: A promise of hope. Accra Daily Mail, p. 11.

- Baker, I., Elwood, P., Hughes, J., Jones, M., & Sweetnam, P. (1978). School milk and growth in primary school children. Washington DC: The Lancer Press.

- Bennett, J., & Strevens, A. (2003). Review of school feeding projects. Westminster: Department for Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Burns, A. C., & Bush, R. F. (1995). Marketing research. Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Buttenheim, A. M., Alderman, H., & Friedman, J. (2011). Impact evaluation of school feeding programmes in Lao PDR. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, 55(18), 19.

- Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. (1992). Ministry of Justice, Pub. L. No. 25 § 1a.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Essuman, A., & Bosumtwi-Sam, C. (2013). School feeding and educational development. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(1), 25–262.

- Gelli, A., & Daryanani, D. (2006)). School feeding moving from practice to policy: Reflections on building sustainable monitoring and evaluation system. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3), 310–317. doi:10.1177/156482651303400303

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2010). Population and housing census. Ghana: Author.

- Gleason, P., & Suitor, C. (2000). Changes in children diets. Wasington DC: United States Department of Agriculture and Nutrition Press.

- Government of Ghana Report on School Feeding Programme. (2006). Accra: Accra Printing Press Assembly.

- Iddrisu, I. (2016). Universal basic education policy: Impact on enrolment and retention. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(17), 141–148.

- Index Mundi. (2016). Ghana GDP-per capita income. Retrieved March 7, 2017, from index mundi. http://www.indexmundi.com/ghana/gdp_per_capita_(ppp).html

- Jacoby, H. G. (2002). Is there intra-house “fly paper effect’? Evidence from a school feeding programme. The Economic Journal, 12(4), 12–13.

- Janke, C. (2001). Food and Nutrition: Background considerations for policy and programming. Catholic Relief Services, July, 26-29.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 607–610. doi:10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kristjansson, E. A., Robinson, V., Petticrew, M., MacDonald, B., Krasevec, J., Janzen, L., & Shea, B. J. (2007). School feeding for improving the physical and psychosocial health of disadvantaged elementary school children. Copenhagen: Campbell Review, SFI Campbell.

- Levitsky, D. (2005). The future of school feeding programmes. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 26(87), 3. doi:10.1177/15648265050262S221

- Martens, T. (2007). Impact of the Ghana school feeding programme in four districts of the central region of Ghana (PhD thesis). Division of Nutrition, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row Publishers Inc.

- Mayaki, I. A. (2015). Home grown school feeding. Keynote Address on a CAADP Conference; NEPAD, South Africa, Johannesburg.

- McLeod, S. (2016). Maslow’s hierarch of needs. Simple psychology. Retrieved March, 29, 2017, from https://www.simplypsychology.org › Perspectives › Humanism

- Merriam, S. (2000). Qualitative research and case-study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Ministry of Education. (2006). Ghana education service: Education management information system. Schools Annual Census, 1-15.

- Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development Report. (2005). District operations manual: Ghana school feeding program. Accra: Edo printing Press.

- Nuako, K. (2007). Ghana school feeding programme implementation and results to date. Accra: National School Feeding Programme Secretariat.

- Ohene-Afoakwa, E. (2003). Enhancing quality of feeding in educational institutions in Ghana: Development and challenges. Retrieved June 16, 2016, from www.works.com/emanuelohenefoakwa

- Osei, R. D., Owusu, G. A., Asem, F. E., & Afutu-Kotey, R. L. (2009). Effects of Capitation grant on education outcomes in Ghana (pp. 1–30). Accra: Institute of Statistical Social and Economic Research (ISSER).

- Osei-Fosu, A. K. (2011). Evaluating the impact of the capitation grant and the school feeding programme. Home Journal, 31(1), 25-51. Kumasi: KNUST press.

- Sally, M., Grartham-McGegrregor, S., Chang, S., & Walker, P. (2015). Evaluation of school feeding programmes. Jamaican Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 4(9), 646–653.

- Suresh, C. B., & Anne, J. H. (2015). Socio-economic impact of school feeding programmes. Empirical Evidence from a South Indian Village, 14(1), 1–5.

- World Food Programme. (2006). Global school feeding report. Rome: Commonwealth Secretariat.