Abstract

This study sets out to investigate physical education (PE) teachers’ perceptions of the use of an online professional development resource to support making reasonable adjustment for learners with disability. The Equality Act (2010) called on all UK schools to ensure access to PE was equitable for all learners. This means schools have to adopt strategies for making reasonable adjustments so as not to disadvantage learners with any special educational need and disability. Teachers report that they are working towards an inclusive classroom; however, parents of learners with disabilities report that there remains a lack of opportunities for their children to engage with activity.

Using purposive sampling, participants were selected for the study after which they were asked to complete a continuing professional development online training course on the subject of making reasonable adjustments for learning with disabilities. Through one-to-one interviews, qualitative data were collected and analysed through thematic analysis. The findings indicated that the online resource was greeted positively by staff and not only supported the PE teachers but also increased their awareness of different approaches to making reasonable adjustments. The findings also indicated that the issue of making reasonable adjustments and the use of the online development tool need to be driven from the school senior leadership team if it is to have value for the whole school community.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The use of online tools for Professional Development to support teachers in enhancing and supporting learners with disabilities is an important means of assisting classroom practice. Schools have to adopt strategies for making reasonable adjustments so as not to disadvantage learners with any special educational needs and disability in all subjects and particularly physical education. Traditionally, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is where teachers would attend one-day workshops to develop their knowledge. The use of the online tool in the current age of technology is a suitable method of delivering CPD, in terms of both time and cost to teachers and their educational institutions. Online CPD tools can support teaching and learning dynamically by providing extensive resources and learning experiences that enable teachers to collaborate across programmes and schools. This paper focuses on the teacher's perceptions of an online professional development tool to support and enhance practice of learners wit disabilities in physical education.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on teacher’s perceptions of an online professional development tool to support and enhance practice of learners with disabilities in physical education (PE). Continuing professional development (CPD) can be formal or informal; its aim is to help teachers develop their skills and knowledge and enhance their professional practice. The frequency, quality and relevance of professional development for PE teachers are fundamental to improving teaching (Vickerman & Coates, Citation2009). A lack of knowledge, skills, experience and confidence to teach pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND), explained, to some extent, as to why pupils with SEND generally participated less often and in fewer activities when compared to their age-peers in mainstream school PE (Fitzgerald & Kay, Citation2005: Morley, Bailey, Tan, & Cooke, Citation2005). The importance of appropriately trained PE teachers becomes more apparent here if they are to meet the government expectation for making reasonable adjustments for pupils with SEND. Vickerman and Coates (Citation2008) identified lack of knowledge around disability by teachers as being a key factor quoted by learners with disability as shaping their own lack of school sport participation. Large-scale studies such as Colver et al. (Citation2010) and Hammal, Jarvis and Colver (Citation2004) proposed that inequality and inconsistency of messages in regards to policies of making reasonable adjustments had a detrimental effect on accessing resources for service providers and people with disabilities. They suggested that with better access and appropriate resources there followed greater participation.

Traditionally, CPD is where teachers would attend one-day workshops to develop their knowledge. However, in a study by Boyle, Lamprianou and Boyle (Citation2005), teachers reported such professional development as very mechanistic, where teachers are talked at passively by experts suggesting the need for alternative ways to deliver teacher professional development. Armour and Yelling (Citation2007) have equally suggested that in order for CPD in PE to meet the needs of the teacher, there is a demand for fundamental change. CPD should enable teachers to reflect and act upon their observation and analysis of their own teaching to improve pupil learning and their own teaching (Zwordiak-Myers, Citation2012). Currently, CPD is delivered in many different formats including development courses, online training and workshops. According to Boyle et al. (Citation2005), the most effective CPD is personalised, relevant and collaborative. Current PE literature has not attempted to evaluate the impact of a specific online development tool, making this paper unique in its field. This study, therefore, sets out to investigate the teachers’ perception of the use of an online professional development resource in supporting them to make reasonable adjustment for learners with disability.

1.1. A need for online professional development in PE

The effects of using technology in order to provide tools to support professional development, with the overall goal of enhancing learning and teaching (Becta, Citation2008), have been a focus for a number of years (Becker, Bohnenkamp, Domitrovich, Keperling, & Lalongo, Citation2014). One aspect of technology that has increased in popularity over recent years is online professional development (Becker et al., Citation2014; Dedman & Bierlein Palmer, Citation2011; Paranal, Washington Thomas, & Derrick, Citation2012). Online training can be as effective as face-to-face professional development as the resulting outcomes of can be comparable, or even better than face-to-face (Becker et al., Citation2014). However, these programmes have encountered a number of issues, including lack of time to engage and innovate, lack of support from school leadership and lack of collaboration within departments and across schools (Wang & Woo, Citation2006). The traditional in-service (INSET) approach that delivers information and guidance to teachers is moving towards a more co-learning style. This method recognises a teacher’s own knowledge and experience must be at the centre of professional development, to make it something “done with them”, not “done to them” (Laurillard, Citation2014).

If used effectively, technology can support teaching and learning dynamically by providing extensive resources and learning experiences, where it “ […] enables professionals to share expertise and resources within and beyond their own institution” (Becta, Citation2008, p. 11). Dalston and Turner (Citation2011) outlined the different levels of online training, where the lowest and most popular level is where the learning material is made available online and the learner works through the content alone without any peer or institutional support and without the involvement of their line manager.

The resource was created as an online tool, as the value and popularity of this form of professional development is fourfold, these being flexibility, time and place, fiscal viability and the acquisition of knowledge in relation to learners’ needs. A range of authors highlight the choice of time and place offered to learners as the main benefit of the online professional development programmes (Becker et al., Citation2014; Kenny, Citation2007; Paranal et al., Citation2012; Wang & Woo, Citation2006). However, the empirical evidence available identified a lack of training for pre-service teachers in PE (Armour & Yelling, Citation2007) including the specialist and often-complex area of SEND (Morley et al., Citation2005). A study by Vickerman (Citation2007), for instance, suggested that 50% of the 30 teacher training providers surveyed in his report found it difficult to dedicate time for SEND training. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a lack of SEND training for pre-service teachers has led many teachers, educationalists and academics to call for inclusion and SEND to form an integral aspect of professional development programmes for serving PE teachers (Vickerman, Citation2007).

The online professional development resource focused on in this study has three aims. First, to ensure that PE teachers understand the need for reasonable adjustments to be made according to the “Equality Act” (2010). Second, to confirm that PE teachers understand the range of adjustments that can be made to increase the participation and attainment of learners with disabilities. Third, to ensure that PE teachers understand the use of a range of strategies to improve the outcomes for all pupils with disabilities, with specific reference to current policy, the adaptation of equipment and the deployment of Teaching Assistants.

The online resource highlights both policy and practice to enable understanding of both the reasonable adjustments duty for learners with disability and the implications in the educational environment. The definition of disability was set out in the Disability Discrimination Act (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Citation1995) in England with a duty placed on schools to take reasonable steps to ensure that learners with disabilities were not placed at a disadvantage. Schools are required to make “reasonable adjustments” through the development and implementation of strategies to improve “access” to physical environments and the taught curriculum (Porter, Georgeson, Daniels, Martin, & Feiler, Citation2013).

Amongst the many barriers in which inclusive provision can deliver most gains is the physical environment, be it in the teaching, in the coaching, in artistic dance spaces or outdoor educational and adventurous settings. It is well established that the equipment and technical adaptions available can provide significant scope for improving levels of inclusivity in provision and delivery (Vickerman, Citation2007). Likewise, access and physical environment including ramps or choice of inappropriate locations is a central facilitator or inhibitor to inclusive practice in activities involving physical activity (Goodwin & Watkinson, Citation2000).

2. Methodology

2.1. Background

Academic staff from a university in North-West England gained funding from the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) to develop an online professional development resource that composed of a suite of modules to help pre- and in-service teachers make reasonable adjustments for learners with disabilities. The EHRC’s role is that of outcome-focused strategic regulator, promoter of standards and good practice and centre for intelligence and innovation (Equality and Human Rights Commission, Citation2015). The online resource focused on a range of curriculum subjects and various post holders including special educational needs coordinators and senior leaders within a school. Initially, the resource was made available to schools from the university’s database through an email invite. Schools simply had to register following, which individual staff from across the whole school could then register.

2.2. Online resource

A key aim of the resource is to ensure that schools are aware of learner’s physical or mental health conditions, and the challenges they face in school. Good lesson planning, in which differentiated activities are available, will enable pupils with disabilities to access the activity (Vickerman & Hayes, 2012). There may be some individual lessons where modifications or adjustments will need to be made to ensure that all pupils are included. The online training adopted by the resource in this research paper followed this pattern. Utilising a mix of videos of expert teachers, case studies from schools, talking heads and multiple-choice activity tests, each unit encouraged the teacher to reflect on their current practice and their own knowledge and ability in making reasonable adjustments in PE. The materials not only tested their current knowledge but also included tasks and prompts, including suggested discussions with colleagues, around supporting learners with disabilities

2.3. Approach

An interpretivist, qualitative approach was used in this research because it was deemed the most appropriate for exploring the key research question (Tashakkori & Teddlie, Citation2010). The approach illuminated PE teachers’ perceptions of the online resource and how it has, or has not, influenced and supported the way in which they make reasonable adjustments for learners with disabilities. An interpretivist approach affords an understanding of the social worlds of teachers through an exploration of meaning constructed by them (Bryman, Citation2012). A notable limitation of qualitative approaches is that the knowledge generated from this small sample of PE teachers cannot and should not be generalised to wider populations of teachers. Nonetheless, the findings of this study can go some way towards contributing to the ever-growing body of knowledge on using an online resource as a form of CPD (Becker et al., Citation2014).

2.4. Participants and settings

The North-West university’s school database was utilised to offer the online professional development resource to schools. All schools registered were then used as a basis for sample recruitment and a mostly inductive qualitative approach was undertaken. Purposeful sampling was used to include only those participants who were teachers, who had studied the online modules on reasonable adjustments and were currently teaching PE in a secondary school in this area; had experience of working with learners with disabilities; and were available and willing to participate in an interview. Participants were recruited from two secondary schools in the North-West of England (n = 6). The ages ranged from 24 to 46 years with a mean of 32 and included 3 males and 3 females.

While all research involves ethical issues, Punch (Citation2005) asserted that they are likely to be more acute in social research because it requires collecting from people, about people. Ethical issues are heightened in qualitative investigations because the level of intrusion into people’s lives is often greater than in quantitative research (Punch, Citation2005). Consideration was given to ethical issues in adherence to the revised BERA Guidelines 2011 from the outset of this qualitative study, including ethical approval from the institution.

An information letter was distributed to the participants prior to their involvement, which explained the study and requested their involvement in the research. Furthermore, participants signed consent forms as evidence that their involvement was voluntary and that they were aware that they could withdraw from the study at any moment with all data generated being destroyed. To preserve the participant’s confidentiality, each participant was identified by a pseudonym (Webster et al., Citation2010). Interviews were held in an office at the school where the PE teacher worked. This setting was used as the familiarity of the environment may have encouraged more open and honest answers, thus resulting in the capture of richer data (Bryman, Citation2012).

2.5. Method and procedure

Individual, semi-structured interviews were chosen as the method to collect the data as they were recognised as a valuable instrument in interpreting, constructing and negotiating the meaning of the PE teacher’s perceptions of using the online resource. The interviews generally lasted between 30 and 40 min and were all conducted by the same researcher for consistency (Merriam, Citation2009).

In order for the discussion to have a degree of structure and be relevant to the objectives of the research, an interview guide was used (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2011) based on six questions:

What previous experience do you have of working with disabled young people?

What is your understanding of reasonable adjustments?

How did the online modules influence your understanding of reasonable adjustments?

What impact have the online modules had on your current teaching practice?

Have the online modules influenced the progress of the disabled pupils you teach?

What more needs doing to ensure that reasonable adjustments are made for disabled pupils?

These questions helped to ensure that an appropriate degree of consistency across the interviews was achieved, while giving enough flexibility to allow for exploration of issues that were salient to each individual (Arthur et al., Citation2013). An audio recording device was used, with the permission of participants, to record the interview. This approach attempted to prevent key information being missed and allowed the facilitator the freedom to engage with the interview. Interviews were transcribed by an external agency and care was taken to comply with the university’s ethics committee information on confidentiality arrangements. Transcripts were also saved to a password-protected file on a personal computer for data analysis.

2.6. Data analysis

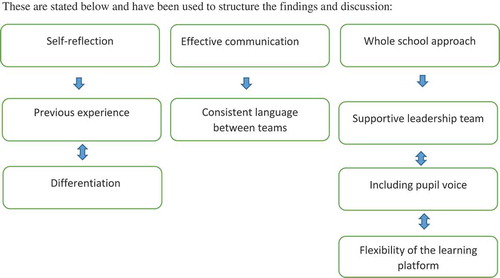

Thematic analysis is an approach which advocates a thorough examination and interpretation of the ways in which “events, realities, meanings and experiences” operate in society (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 9). Transcripts were re-read a number of times by two researchers in order to obtain an understanding and overview of the complete data set (Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bonda, Citation2013). The two researchers were then tasked with generating categories independently without seeing each other’s list. Coding involved highlighting sections of the transcripts aligned to the research objectives. The lists of categories were then discussed and agreed between the two researchers and hierarchical ordering of data was achieved using themes. Thematic analysis provides researchers with a flexible yet structured framework that can inclusively interpret data across a number of participants. The aim of this stage is to attempt to enhance the trustworthiness of the categorising method and to guard against researcher bias. The three emerging themes were self-reflection, effective communication and whole school approach.

These are stated below and have been used to structure the findings and discussion:

3. Findings and discussion

3.1. Self-reflection

All six participants acknowledged that online learning allowed them to complete the professional development resource around the other aspects of their responsibilities during a school day. A flexible approach agrees with Wang and Woo (Citation2006) in relation to the value of a self-directed learning environment as opposed to face-to-face learning. On a personal level, they suggested that there had been an increased level of self-reflection after the completion of the online resource, which enabled them to consider their current practice in the implementation of reasonable adjustments, as well as giving insight into what practical solutions could be applied within future lessons. Martine reflected on this issue claiming that

…It makes you stop and think am I doing everything I can [for pupils with disability].

In addition, Jenny reported that by using some of the ideas from the online module, she saw one pupil progress in one of her sessions:

…because I’ve implemented the suggestions they’ve been able to make progress.

The online resource detailed the need for PE teachers to ensure that they fully understood the range of adjustments and strategies that can be used to increase the participation and attainment of learners with disabilities, including the adaptation of equipment and deployment of teaching assistants (Vickerman, Citation2007). When asked about their current understanding of reasonable adjustments, all participants cited planning as an important aspect of making reasonable adjustments, and this included formulating individual plans for learners with disabilities. After completing the module and reflecting on their current practice, respondents acknowledged that they needed to plan in more detail to make lessons more inclusive. Martine stated:

I will now ensure that I plan in depth for all pupils, but particularly those with disabilities.

As part of the module, the online resource outlined the need for differentiation. Teachers of all subjects need to be creative and flexible in order to develop and deliver differentiated lessons that optimise the capabilities of all pupils, even more so for learners with disabilities (Lovey, Citation2002). After completing the tasks, all the participants agreed that this was a priority in understanding how to include reasonable adjustments within their lessons. Differentiating a learning activity or experience involves making reasonable adjustments because changes made ensure that pupils with SEND are not disadvantaged (EHRC, Citation2015). For example, the ability to alter the lesson plan for the adaptation of equipment, resources and tasks when necessary, as well as adapting the criteria for assessment accordingly in order to enhance learning was outlined as important. In general, participants within this study outlined that making reasonable adjustments involved encouraging integration and subsequent participation of learners with disabilities in order to achieve the overriding goal of success and enjoyment within PE lessons.

In addition to this, participants had a variety of positive feedback regarding the online modules, some of which included not only the significant improvement upon their current knowledge of reasonable adjustments but it also gave them insights into planning and delivery of PE for all pupils. The module also allowed the teachers to reflect on making reasonable adjustments for all learners across the school not just in PE as Simon alludes to:

I’m now aware of the fact that making reasonable adjustments is now more of a whole school issue, rather than an individual staff issue.

3.2. Effective communication

The participants were encouraged as part of the online training resource to communicate with the rest of their department and hold further discussion around the inclusion of learners with disabilities. However, participants were very much on a personal level indicating that there is further work to be done on developing a whole department and whole school approach. Martine commented that

I did speak to other staff members about the resource, I think one or two had a look at it, but others said they did not have time so unless it was a directive from senior management they would not do it.

Debbie summarised this in her concluding statement regarding communicating about professional development for making reasonable adjustments for disabled pupils:

If you’d have sent me an email saying there’s something online for reasonable adjustments […] would I do it? Probably not because I’d probably have pushed it to the back of my mind.

Despite this lack of departmental communication, teachers reported positively regarding the online modules, improving their current knowledge of reasonable adjustments; it also gave them insights into planning and delivery of PE for all pupils.

In order for teachers to plan and implement the appropriate reasonable adjustments, they must have the ability to communicate effectively and sensitively with the pupils, parents and support staff to implement the appropriate reasonable adjustments (EHRC, Citation2015). Having completed the online module, one of the participants commented that

…making reasonable adjustments should also involve the avoidance of labelling children with disability in order to encourage full integration and participation, this training has shown me the language I should be using which will be help in the future.

Colver et al. (Citation2010) alluded to the need for a consistent message from teachers to promote participation, as part of a whole school senior leadership approach and more time for teachers to undertake professional development then a school could develop an inclusive and varied curriculum, not only in PE but also across the school. Such an approach to reasonable adjustments for learners with disabilities is supported in England through statutory and non-statutory guidance such as the National Curriculum Inclusion statement (DfE, Citation2004) and the Reasonable Adjustments policy (EHRC, Citation2015).

3.3. Whole school approach

It is important to note that the teachers outlined the potential disengagement of staff with online modules, especially if the training is not compulsory. Some respondents argued that staff might feel less encouraged to consider reasonable adjustment training if they are currently not teaching any pupil with disability at that time. The majority of participants stated that the online tool had been of personal benefit in developing their knowledge and practice of delivering inclusive lessons. They also agreed it had potential to support a whole school approach including teaching assistants, support staff and external coaches because of its modular approach. However, there was a need for the senior leadership team to drive this initiative. This agrees with a report by Pont et al. (Citation2000), who raised the lack of support from school leadership as an issue in improving professional development. All participants placed an overwhelming emphasis on the need for support for teaching learners with disabilities, whether that be from senior leadership, support staff, their school’s professional development structures and parents. Equally, participants suggested that a consistent message from teachers is required, thus supporting Colver et al. (Citation2010).

If there were a whole school senior leadership approach and more time for teachers to undertake professional development, then a school could develop an inclusive and varied curriculum, not only in PE but also across the school. Both Martine and Simon highlighted limited availability to training and the need for reasonable adjustments to be part of a “whole school policy” driven by the Senior Management Team to encourage, promote and ensure implementation of practice. Vickerman and Coates (Citation2008) have suggested that there is generally a lack of professional development in this area.

Martine stressed

The Head has to opt in to such online modules and also to address training for teaching pupils with disabilities.

Consistent with guidance from the EHRC (Citation2016), a whole school approach also needs to include advice from learners with disability themselves in order to understand and appreciate what they find useful and helpful and what could be improved in order to make their experience a success. Jenny summarised this viewpoint:

We need advice from the children themselves, what do they find useful? What do they find helpful?

This reflected the views of Ian:

Students can let teachers know how they helped them to progress, and how they supported them on a one-to-one basis.

Three participants suggested the need for specialist training and support for more practical or vocational subjects due to the perceived increased difficulty in implementing reasonable adjustments in these lessons. Vickerman (Citation2004) reported that teachers have a lack of knowledge for the delivery of inclusive lesson. Therefore, it is quite disturbing to think, some 6 years on teachers still make similar claims and does strongly suggest that a change in the philosophy towards learner with disability is still required.

The online resource focused on planning and preparation to include learners with disabilities and all participants cited the need for more planning and preparation. The participants outlined that they are not given enough time in advance to plan in order to make reasonable adjustments and feel “out of the loop” when it comes to being aware of additional needs. Therefore, the feedback suggests that teachers would appreciate an opportunity to meet with support staff and parents. Furthermore, some participants feel that although in-service training for teaching pupils with disability may be in place, there is often a lack of practical solutions, help or advice. This was summarised by Simon concerning his view on in-service training:

For starters, training for teachers, requires attention. It is very difficult in PE if you are solo teaching and dealing with a whole range of abilities. Integration is hard without neglecting the other 32, 33, or 34 [pupils] there might be.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

There was a belief that the online resource was of value, though, ultimately it requires support from the senior leadership team and time allocated to undergo the professional development. There needs to be a whole school policy that integrates this area as one of great importance with that of other major issues in the school.

The use of the online CPD tool has promoted self-reflection around subject knowledge, though at an individual level more so than group reflections, suggesting that further work is required to develop the online platform where teachers are encouraged to interact in groups beyond taking the module itself. Holmes (Citation2013) recommends that the use of developing online learning communities would facilitate such group interaction.

Guskey (Citation2002) pointed out if teachers are to be held accountable for education, then the approach to developing in-service training needs to be more appropriate to their requirements. This study concludes that online provision, by its flexible nature, is suitable for the teaching profession as it allows completion between other commitments and by having this continual access to training is a real benefit of online training to the teaching profession (Holmes, Citation2013). In addition, the way the online material is presented is important and this study has shown that teachers appreciate receiving a mix of video, talking head, case studies and multiple-choice tests. This variety also ensures that it is aligned with different roles, including teacher, teaching assistant and senior leadership.

The study also concludes that whether CPD is online or a more traditional approach it must have the support and encouragement of the Head Teacher and the Senior Leadership Team in order to create an ethos within the school that suggests confidence in making reasonable adjustments for disabled pupils. Overall, if a school supports a professional development programme, there will be more consistency in staff approaches to making reasonable adjustments.

Currently, teachers view the need for professional development in the area of reasonable adjustments on a “need to know” basis, suggesting that they seek out the support in this area, as and when they have a disabled learner in their class. This supports the need for online tools, such as the one in this research, that are easily accessible for individuals. The teachers in this research felt that, because of taking part in the online module, they were provided with a greater range of knowledge and understanding for making reasonable adjustments in their PE lessons and were more reflective in working alongside pupils with disability.

However, whilst teachers in this study felt that they made reasonable adjustments for pupils with disability as part of their practice, this paper shows clear signs that there is a disconnect between the use of language used by teachers and the language by policy makers. Teachers used the term “pupils with Special Educational Needs” and “pupils with Disability” as one of the same, this is in fact not the case (EHRC, Citation2015). Not all pupils with a disability have a special educational need but still require a “reasonable adjustment” being made to their learning situation. It is vital, therefore, that teachers are fully informed of their pupils’ needs in order that the most appropriate reasonable adjustment can be made. The use of terminology and language for teachers therefore needs to be addressed, and to some extent, this is what the online module provided for teachers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara Walsh

Barbara Walsh is the director of School for Sport Studies, Leisure and Nutrition at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). Her current interests lie in mentoring, coaching and understanding the complexities of self as part of a developmental journey.

Track Dinning

Track Dinning is a programmes manager in the School of Sport Studies, Leisure and Nutrition. Her main research focus is the development of student employability and enterprise skills.

Julie Money

Julie Money is a programmes manager in the School of Sport Studies, Leisure and Nutrition. Her research is based around the student experience in Higher Education.

Sophie Money

Sophie Money is a teacher of Modern Languages at Wirral Grammar School for Boys; her research interests are school students’ reflection on their learning and post-colonial identity in France.

Anthony Maher

Anthony Maher is a senior lecturer in Physical Education and Youth Sport at Edge Hill University. Anthony’s research and teaching interests relate mainly to diversity, equity and inclusion in physical education; teacher education; special education; and disability sport.

References

- Armour, K. M., & Yelling, M. (2007). Effective professional development for physical education teachers: The role of informal, collaborative learning. Journal of Teaching PE, 26(2), 177–200.

- Arthur, S., Mitchell, M., Lewis, J., & McNaughton-Nicholls, C. (2013). Designing fieldwork. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. McNaughton-Nicholls, & R. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (2nd ed., pp. 147–176). London: Sage.

- Becker, K. D., Bohnenkamp, J., Domitrovich, C., Keperling, J. P., & Lalongo, N. S. (2014). Online training for teachers delivering evidence –Based preventive interventions. School Mental Health, 6, 225–236. doi:10.1007/s12310-014-9124-x

- Becta. (2008). Harnessing technology: Next generation learning 2008–2014. Coventry: Author.

- Boyle, B., Lamprianou, I., & Boyle, T. (2005). A longitudinal study of teacher change: What makes professional development effective? Report of the second year of the study. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16(1), 1–27. doi:10.1080/09243450500114819

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Colver, A., Dickinson, H., Parkinson, K., Arnaud, C., Beckung, E., Fauconnier, J., … Thyen, U. (2010). Access of children with cerebral palsy to the physical, social and attitudinal environment they need: A cross-sectional European study. Disability Rehabilitation, 33, 28–35. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.485669

- Dalston, T. R., & Turner, P. M. (2011). An evaluation of four levels of online training in public libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 30, 12–33. doi:10.1080/01616846.2011.551041

- Dedman, D. E., & Bierlein Palmer, L. (2011). Field instructors and online training: An exploratory survey. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(1), 151–161. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900057

- Department for Education and Skills. (2004). Removing barriers to achievement: The government’s strategy for SEN. London: HMSO.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC). (2015). Reasonable adjustments. Retrieved September 25, 2017 from Higher education provider's guidence, http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/private-and-public-sector-guidance/education-providers/higher-education-providers-guidance/key-concepts/what-discrimination/reasonable-adjustments

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) (2016). Commission launches online training kit to help schools unlock opportunity for disabled children. Retrieved August 10, 2017 from http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/commission-launches-online-training-kit-help-schools-unlock-opportunity-disabled-children

- Fitzgerald, H., & Kay, T. (2005). Research report: Gifted and talented disability project. Loughborough: Loughborough University.

- Goodwin, D. L., & Watkinson, E. J. (2000). Inclusive physical education from the perspective of students with physical disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 17(2), 144–160. doi:10.1123/apaq.17.2.144

- Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381–391. doi:10.1080/135406002100000512

- Hammal, D., Jarvis, S. N., & Colver, A. F. (2004). Participation of children with cerebral palsy is influenced by where they live. Dev Med Child Neurol, 46, 292–298. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00488.x

- Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. (1995). Disability and discrimination act (1995). London: HMSO.

- Holmes, B. (2013). Schoolteachers continued professional development in an online learning community: Lessons from a case study of an eTwinning learning event. European Journal of Education, 48(1), 97–112. doi:10.1111/ejed.12015

- Kenny, M. (2007). Web-based training in child maltreatment for future mandated reporters. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 671–678. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.008

- Laurillard, D. (2014, January 16). Hits and Myths: MOOCS may be a wonderful idea, but they’re not viable. Times Higher Education, p 28.

- Lovey, J. (2002). Supporting special educational needs in the secondary school classroom (2nd ed). London: David Fulton.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). London: Sage.

- Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Morley, D., Bailey, R., Tan, J., & Cooke, B. (2005). Inclusive physical education: Teachers’ views of teaching children with special educational needs and disabilities in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 11(1), 84–107. doi:10.1177/1356336X05049826

- Paranal, R., Washington Thomas, K., & Derrick, C. (2012). Utilizing online training for child sexual abuse prevention: Benefits and limitations. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 21, 507–520. doi:10.1080/10538712.2012.661696

- Pont, B., Nuschel, D., & Moorman, H. (2000). Improving School Leadership: Volume 1: Policy and Practice. Retrieved March 12 2018 from www.oecd.org/publishing/corrigenda

- Porter, J., Georgeson, J., Daniels, H., Martin, S., & Feiler, A. (2013). Reasonable adjustments for disabled pupils: What support do parents want for their child? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28(1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/08856257.2012.742747

- Punch, K. F. (2005). Introduction to social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage.

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). Putting the human back in “human research methodology”: The researcher in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(4), 271–277. doi:10.1177/1558689810382532

- Vaismoradi, H., Turunen, H., & Bonda, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

- Vickerman, P. (2004). The training of Physical Education Teachers for the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs: PhD Thesis, School of Education, University of Leeds: Leeds, UK.

- Vickerman, P. (2007). Teaching physical education to children with special educational needs. London: Routledge.

- Vickerman, P. (2012). Including children with special educational needs in physical education: Has their entitlement and accessibility been realised. Disability and Society, 27(2), 249–262. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.644934

- Vickerman, P., & Coates, J. K. (2008). Let the children have their say: A review of children with special educational needs experiences of physical education. Support for Learning, 44, 168–175.

- Vickerman, P., & Coates, J. K. (2009). Trainee and recently qualified physical education teachers’ perspectives on including children with special educational needs. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14(2), 137–153. doi:10.1080/17408980802400502

- Wang, Q., & Woo, H. (2006). Comparing asynchronous online discussions and face-to-face discussions in a classroom. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(2), 272–286. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00621.x

- Webster, R., Blatchford, P., Bassett, P., Brown, P., Martin, C., & Russell, R. (2010). Double standards and first principles: Framing teaching assistant support for pupils with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(4), 319–336. doi:10.1080/08856257.2010.513533

- Zwozdiak-Myers, P. (2012). The teacher’s reflective practice handbook: Becoming an extended professional through capturing evidence-informed practice. London: Routledge.