Abstract

To capture the unique nature of collective teacher efficacy as reflected in ELT settings, the current study attempted to develop and validate a context-specific collective efficacy scale and use it in exploring collective efficacy beliefs in different ELT contexts. To achieve this goal, guided by the related literature, the most prominent constituent elements of collective teacher efficacy were identified through a series of semistructured interviews with English language teachers and instructors in educational contexts of school, institute, and university. Based on the seven-component initial model obtained from qualitative content analysis, a 32-item questionnaire was developed and tried on 405 EFL teachers and instructors. The data were then subjected to exploratory factor analysis. The proposed model consisted of 21 items encompassing four factors. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the scale showed indices of construct validity and suitably fit the proposed collective efficacy model. Applying a one-way ANOVA also revealed that the three educational contexts differed significantly with respect to English teacher collective efficacy beliefs. English language institute teachers displayed the highest collective efficacy level while university instructors showed the lowest level. A significant difference existed between institute and high school teachers and university instructors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Due to its significant importance in teachers’ accomplishment, collective teacher efficacy has been greatly emphasized in the last two decades. Accordingly, several collective efficacy instruments have been developed which have proved to be well designed but context-neutral. Therefore, the current study attempted to construct and validate a context-specific scale of collective teacher efficacy which would reflect the underlying constituent elements of collective efficacy specific to the ELT context. The newly developed scale was then utilized to investigate school and institutes teachers as well as university instructors’ perceptions and level of collective efficacy and to explore the most prominent dimensions of this construct in each of the three different educational contexts. The results help educators to find ways to improve teachers and instructors’ sense of collective efficacy in the respective educational contexts which in turn lead to enriching the quality of education and enhancing English learners’ performance.

1. Introduction

For over three decades, teacher efficacy has been recognized as one of the most influential teacher-related factors in the educational context (Eells, Citation2011; Goddard, Goddard, Kim, & Miller, Citation2015; Hattie, Citation2016; Holanda Ramos, Silva, Ramos Pontes, Fernandez, & Furtado Nina, Citation2014; Hoy, Citation2012). Bandura (Citation1997) introduces teacher efficacy as an important quality of effective teachers and Wright, Hom, and Sanders (Citation1997) believe that “More can be done to improve education by improving the effectiveness of teachers than by any other single factor” (p. 63).

Since teaching is an interpersonal activity in a group context, teacher efficacy which is defined as “The teacher’s beliefs in his or her capability to organize and execute courses of action required to successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (Tschannen–Moran, Woolfolk Hoy, & Hoy, Citation1998, p. 233), may be affected and formed by different contextual variables in the school (Chong, Huan, Klassen, Wong, & Kates, Citation2010). In this regard, Tschannen–Moran et al. (Citation1998) noticed that teachers did not feel equally efficacious for all teaching situations. They may feel more or less efficacious when teaching specific subjects to specific students in particular settings. Tschannen–Moran et al. (Citation1998) conclude that teacher efficacy ought to be context-specific and it is crucial to look at the contextual specificity of the construct when it is measured.

By the same token, collective teacher efficacy which is defined as “the perceptions of teachers in a school that the efforts of the faculty as a whole will have a positive effect on students” (Goddard, Hoy, & Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2000, p. 480) is context specific. It is regarded as judgments that people make about groups and their capabilities and effectiveness in specific domains of action (Caprara, Barbaranelli, Borgogni, & Steca, Citation2003).

Even though, several collective efficacy scales have been developed so far (Goddard et al., Citation2000; Olivier, Citation2001; Schwarzer, Schmitz, & Daytner, Citation1999; Tschannen–Moran & Barr, Citation2004), most of them have tried to measure the construct in a decontextualized way. In fact, they do not succeed in capturing the contextual specificity of the construct which is highly recommended (Tschannen–Moran et al., Citation1998). To the best knowledge of the researchers of this study, none of the available collective efficacy measures have focused on the specificity of the ELT context which is by nature different from the context of other academic subjects due to the fact that in these contexts both the content and the language of instruction are taught simultaneously (Hawkins, Citation2004). Furthermore, most studies concerning collective teacher efficacy are conducted at school levels; however, studies in the educational contexts of language institutes and specially universities have received little attention. To take a step forward, the main issues addressed in the present study have been to develop and validate a new collective teacher efficacy scale which can reflect the specific context of ELT through probing into the constituent elements of collective efficacy obtained from English language teachers and instructors’ perceptions, and then to examine if different educational contexts of school, English language institute, and university differ regarding English language teacher collective efficacy beliefs.

2. Research questions

The present study aimed at pursuing the following research questions:

What are the underlying factors that constitute the construct of collective teacher efficacy?

Does English language teacher collective efficacy scale (ELTCES) shows indices of construct validity and suitably fit the proposed collective efficacy model?

What is Iranian English teachers and instructors’ level of collective efficacy in different educational context?

Do English language teachers and instructors in the three educational contexts of high school, English language institute, and university differ significantly in terms of their collective efficacy beliefs?

3. Literature review

The construct of teacher efficacy evolved from two different theoretical perspectives: Rotter’s (Citation1966) Locus of Control Theory and Bandura’s (Citation1977, Citation1986) Social Cognitive Theory, both of which emerged from the field of psychology.

In Bandura’s (Citation1977) Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy is regarded as the most fundamental mechanism of human agency. It is viewed as a self-system which is capable of controlling such personal activities as being able to utilize specialized knowledge and expertise appropriately. Thus, self-efficacy beliefs control one’s system of thought patterns and feelings. Such beliefs influence how capable individuals regard themselves to be in achieving their goals. Bandura (Citation1977) asserts that in academic contexts, teachers who believe that they are not able to succeed in teaching their students, do not try hard enough to prepare and deliver appropriate instruction.

Bandura (Citation1993) was the first to broaden the study of efficacy to encompass collective beliefs of individuals within organizations incorporating not only individual teachers but also schools as the unit of analysis (Goddard et al., Citation2000). Collective teacher efficacy is an “emergent group-level attribute, the product of the interactive dynamics of the group members” (Goddard et al., Citation2000, p. 482). Collective efficacy beliefs affect the collective future goals, level of effort exerted, efficacious use of resources, and persistence when dealing with difficulties (Goddard et al., Citation2000).

According to Bandura (Citation1986, Citation1997), self-efficacy beliefs are constructed through individual cognitive processing under the influence of four different types of information: mastery experience, physiological arousal, vicarious experience, and verbal persuasion. He further claims that due to the fact that collective and individual perceptions of efficacy share many theoretical assumptions, the same four sources influence the construction of collective efficacy. When these individual or collective perceptions are formed through the four types of information, the resultant information is then processed cognitively (Bandura, Citation1993). “It is within the cognitive process, or introspective reflection, that beliefs about future performance form” (Adams & Forsyth, Citation2006, p. 4). From this perspective, such beliefs are under the influence of the “circumstantial effects of environmental and contextual factors” (Adams & Forsyth, Citation2006, p. 4).

Ever since Bandura (Citation1993, Citation1997) introduced the construct of collective teacher efficacy, many researchers have tried to operationalize it by developing collective teacher efficacy scales, such as Collective Teacher Self-Efficacy (Schwarzer et al., Citation1999), Collective Teacher Efficacy Scale (Goddard et al., Citation2000), Teacher Efficacy Belief Scale-Collective Form (Olivier, Citation2001), Collective Teacher Beliefs Scale (Tschannen–Moran & Barr, Citation2004). Since then, collective teacher efficacy has been extensively investigated probing its relationship with various variables, such as self-efficacy of teachers and students’ performance (Goddard et al., Citation2000; Tschannen–Moran & Barr, Citation2004), school contextual factors (Chong et al., Citation2010), satisfaction at work (Abdeli Soltan Ahmadi, Eisazadegan, Gholami, Mahmodi, & Amani, Citation2017; Göker, Citation2012; Stephanoul, Georgios, & Doulkeridou, Citation2013), confidence in the coworkers (Lee, Zhang, & Yin, Citation2011), teacher empowerment and leadership (Baleghizadeh & Goldouz, Citation2016; Henday Al–Mahdi, Mohamed Emam, & Hallinger, Citation2017), professional learning (Lee et al., Citation2011; Lin, Citation2013), principal self-efficacy (Tena, Versland, & Erickson, Citation2017) and demographic variables, such as teachers’ ethnicity, gender, level of education, and different grade levels (Baleghizadeh & Goldouz, Citation2016; Lin, Citation2013).

The results of the above studies in most cases indicate that there exists a positive relationship between teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs and the aforementioned variables. Never the less, almost all of them have used either Goddard et al. (Citation2000), Tschannen–Moran and Barr (Citation2004), or Olivier’s (Citation2001) collective teacher efficacy scales which do not reflect the contextual specificity of the ELT settings.

In addition, since the construct of collective teacher efficacy has a substantial effect on the enrichment of the quality of educational organizations, commentators have called attention to the need for conducting more studies on the issue with a qualitative and mixed method designs. Accordingly, quite a little research has endeavored to discover collective efficacy-enhancing factors (Zabrina-Anyagre, Citation2017), fundamental features of fostering teacher collective efficacy (Nordick, Citation2017), and how school leaders might promote higher levels of collective teacher efficacy (Prelli, Citation2016) via qualitative approaches. Nonetheless, studies with mixed method design are scarce.

Such mixed method studies can provide deeper insights into the construct’s constituent elements through the qualitative phase and establish the basis for the quantitative phase to probe into teachers and instructors’ collective efficacy perceptions which can in turn shed light on the development and stability of this construct (Holanda Ramos, et al. Citation2014). Such mixed method research also sets the stage for the progress of quantitative research.

To provide new insights into the nature of this construct and to expand the means of measuring it in ELT contexts, the current study has attempted to adopt a mixed method design and develop a context-specific collective efficacy scale to measure and compare English teachers’ collective efficacy perceptions in different educational contexts. Investigating the effect of different educational contexts on EFL practitioners’ level of collective efficacy would offer new perspectives on the issue.

4. Methodology

4.1. The design of the study

Due to the complex and unobservable characteristics of beliefs about the construct of collective teacher efficacy, the present study was designed to use both qualitative and quantitative research methods. In the qualitative section of the study, the aim was to identify the underlying factors that constitute the construct of collective teacher efficacy from English teachers and instructors’ perceptions via a series of in-depth semistructured interviews. The data gleaned from in-depth interviews were analyzed and the common themes that emerged from the qualitative data were used as the basis of the development of the context-specific scale of English teacher collective efficacy beliefs after a process of review and discussion with English teachers and instructors.

The quantitative section of the study was in the form of a survey. After the newly developed 32-item measure underwent a pilot study, it was utilized to gather the data of this section of the study. The aim was to validate the newly constructed scale through the processes of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and to investigate the effect different educational contexts on this construct.

4.2. The qualitative section

4.2.1. Participants

Through purposive and snowball sampling, 28 male and female English teachers and instructors (10 secondary and high school teachers, nine university instructors, and nine institute teachers with years of teaching experience ranging from 5 to 28) were asked to participate in in-depth interviews. Moreover, three university professors, all teacher education experts in English teaching, were interviewed to collect their perceptions regarding English language teachers’ collective efficacy.

4.2.2. Instrument

The most prominent constituent elements of collective teacher efficacy as reflected in English practitioners’ views in educational contexts of school, university, and English language institute were planned to be obtained through a series of semistructured interviews.

To ensure the interviews’ content validity, the interview questions were developed in accordance with the extensive literature review regarding the sources of collective teacher efficacy. Also, by making use of the established collective efficacy questionnaires, namely Goddard et al. (Citation2000), Tschannen-Moran & Barr (Citation2004), and Oliver’s (Citation2001) scales, as well as Banduras’ (Citation1997) 30-item Teacher Efficacy Scale as a guide, the researcher tried to extract the factors which were identified as important collective teacher efficacy underlying factors in the available efficacy measures.

In fact, a comprehensive analysis of the existing scale’s items was conducted to discover the elements which could be used as the basis of a valid and useful interview to detect the underlying elements of collective teacher efficacy from the perspective of English practitioners in the three aforementioned educational contexts.

The interviews were initiated by general open-ended questions regarding the elements that constituted collective teacher efficacy, the characteristics of English teachers with high collective efficacy, and the factors that could affect collective teacher efficacy. As the interviews proceeded, the researcher collected more in-depth information by asking some additional guiding open-ended questions which were based on the factors that were introduced in the related literature as the possible influential factors.

The questions regarding the elements that constitute teachers and instructors’ collective efficacy perceptions were as follows:

How do you define collective teacher efficacy?

What are the characteristics of an English language teacher/instructor with high collective efficacy beliefs?

What individual elements constitute teachers’/instructors’ collective efficacy?

What contextual elements constitute teachers’/instructors’ collective efficacy?

A summary of the additional guiding open-ended questions are as follows:

What do you think the role of the principal, the staff, the colleagues, the students, the parents can be with regard to English practitioners’ collective efficacy beliefs?

From your view point, what would the role of students’ cultural background, students’ proficiency level, the number of students in the class, the availability of resources be concerning English practitioners’ collective efficacy beliefs?

What other Individual/contextual/environmental factors can be considered influential?

To further ensure the interview validity, three university faculty members who were familiar with the concept of collective efficacy were consulted to verify the interview questions which were based on the relevant elements in the collective teacher efficacy literature. They agreed on the suitability of the questions. Validity was also addressed during piloting the interview through discussing the content and relevance of the questions with three English practitioners.

The interview was tried out with three English practitioners. A school teacher, an institute teacher, and a university instructor were asked to participate in piloting the interview and to provide feedback both on the clarity of the questions and on the way the interview proceeded. The researcher explained what the interview questions were intended to discover and the teachers communicated if they arrived at the same understanding. Applying their feedback and making the necessary changes, the researcher was ready to collect the qualitative data.

4.2.3. Data collection and analysis procedures

Before the interviews started, the participants were ensured about the confidentiality of the content of their interviews. They were also informed about the purpose of the interview and were asked to grant the permission so that the researcher could record what they said. The interviews were initiated by general open-ended questions and followed by guiding open-ended questions. Each interview lasted approximately 40 min. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed afterward by the first researcher.

Thematic (qualitative) content analysis was applied to discover the major themes which reflected the underlying elements of collective teacher efficacy. It was conducted through classification process of coding and identifying themes and patterns. To code the data, the process of content analysis began after the first few interviews were conducted. Following Schamber’s (Citation2000, p. 739) recommendation who asserts that the criterion for identifying a coding unit can be “a word or group of words that could be coded under one criterion or category,” the collected data were coded and the emerging themes obtained from related categories were labeled.

To ensure the validity of the qualitative results, several measures were taken. The transcribed interviews were checked more than once, paying special attention to grouping and categorizing them according to their themes. Furthermore, as more data were collected, the coding was checked continuously and new codes and/or themes were added if necessary. Also, naming and coding processes were guided by the review of the related literature and close inspection of applied research results to make sure that the researcher could obtain the themes which reflected the construct under investigation. Moreover, an external reader who was familiar with the construct was asked to code the collected data and to enumerate the categories and major themes. Consensus was acquired through the process of discussing uncertain categories and/or themes. The data were coded as a theme if described, acknowledged, or emphasized by three or more participants. Finally, three university faculty members who were familiar with the concept of collective teacher efficacy were asked to review and validate the obtained categories and themes.

4.3. The quantitative section

4.3.1. Participants

405 EFL high school and institute teachers as well as university instructors from six cities in Fars, Iran, participated in the study through convenient and snowball sampling. The sample included 126 (%31.1) high school teachers (10th–12th grades), 179 (%44.2) institute teachers, and 100 (%24.7) university instructors and professors. The sample comprised of 153 males (%37.8) and 252 females (%62.2) whose age and teaching experience ranged from 24 to 77 (mean = 38.2, standard deviation (SD) = 9.10) and 1 to 38 years (mean = 13.7, SD = 8.2), respectively. A total of 148 held (%36.5) a BA degree, 184 (%45.4) and 73 (%18) had MA and PhD degrees, respectively.

4.3.2. Instrument

The development of the new measure was on the basis of the conceptual framework offered by Bandura (Citation1993, Citation1997) and the theoretical model of teacher efficacy postulated by Tschannen–Moran et al. (Citation1998) in which measures of teacher efficacy are regarded as valid on the condition that they incorporate the assessment of teachers’ personal competence, encompass the analysis of their teaching tasks in the specific educational context, and include items covering obstacles teachers with high efficacy are capable to overcome.

An item pool based on the obtained themes and the categories was developed. The first draft of the questionnaire with 39 items was developed and assessed using experts’ judgment. Four university professors who were familiar with developing surveys in the social science field and the concept of collective efficacy were asked to review the themes and categories and the 39 developed items.

Moreover, an experienced team including two school English teachers, an institute teacher, and two PhD university instructors, all with more than 20 years of teaching experience, reviewed the questionnaire item by item and discussed each item’s relevance to their teaching context and provided feedback on its clarity and interpretability.

Receiving feedback from the reviewers resulted in the following changes: Ambiguous items were revised or discarded, and irrelevant or repetitious items were identified and eliminated reducing the number of items to 25. Seven new items were also developed by the aforementioned experienced team added to the questionnaire. The result was a revised 32-item questionnaire. Examples of the added items are:

How much can we, English language teachers, do to positively influence the instructional quality of the school by sharing our successful teaching experiences with our colleagues?

As English language teachers at this school, to what extent can our opinions influence the educational decisions at school?

In the final form of the instrument, the items focused on how teachers assessed their abilities to perform with regard to each teaching task or their personal competence focusing on what “we, as English teachers at this school/institute” or “we, as English instructors at this university” are able to do. For example, for the item “As English teachers at this school, how well can we succeed in teaching English language skills to our students?” the corresponding item for the institute teachers would be “As English teachers at this institute, how well can we succeed in teaching English language skills to our students?”, and the corresponding item for the university instructors would be “As English instructors at this university, how well can we succeed in teaching English language skills to our students?”

The 32-item newly developed scale called English Language Teacher Collective Efficacy Scale (ELTCES) was then subjected to a pilot study. A toytal of 35 high school teachers (25 females and 10 males) from 27 schools participated in the pilot study. Their age ranged from 24 to 56 years with an average teaching experience of 22 years. The participants were asked to respond to the 32-item questionnaire on a six-point Likert scale ranging from (1) None at all to (6) A great deal (see Appendix A).

The results revealed that the teachers approved of the items and no further revision needed to be applied. Also, the reliability of the instrument measured by Cronbach’s alpha showed a value of .93. The reliability was also checked through test-retest reliability by conducting the questionnaire twice within 2- to 3-week time interval. A total of 25 English teachers and instructors including12 institute teachers, and 13 university instructors (20 females and 5 males) took part in the test-retest study. Cronbach’s alpha showed a value of .95 and .93 for the first and second application of the questionnaire. A correlation of r = .81 (p < .01) was obtained between the two showing that they were highly correlated.

4.3.3. Data collection and analysis procedures

A total of 590 questionnaires were distributed in person and through e-mail. From the 436 questionnaires returned to the researchers (response rate of 73%), 31 were discarded due to being incomplete. The remaining 405 questionnaires were subjected to exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. In the exploratory factor analysis, principle components factoring with Varimax rotation was carried out, and in the confirmatory factor analysis phase of the study, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were employed as tests of incremental fit. Also, as tests of absolute fit, Chi-Squared Statistic, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Goodness of Fit Indices (GFI) were carried out (Ho, Citation2006; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) to evaluate model fit. In addition, a one-way ANOVA was utilized to examine the effect of educational context on the construct.

5. Results

5.1. Results of the qualitative section

To answer the first research question, “What are the underlying factors that constitute the construct of collective teacher efficacy?”, after the process of the interview content analysis was completed and the obtained results were compared with the supportive literature, seven major themes and 26 categories regarding collective teacher efficacy in the ELT context emerged. The obtained themes and categories are presented in Table .

Table 1. Themes and categories of English language teacher collective efficacy

The most frequent theme disclosed by EFL teachers and instructors concerned instructional capability. They recognized instructional ability which encompassed the ability to promote creativity in students, to improve their motivation, to recognize their needs, to possess language teaching knowledge and skills, and to use effective teaching strategies and methods as one of the major collective efficacy themes. They affirmed that teachers with such capabilities are assumed to possess a high sense of collective efficacy which enables them to achieve instructionally challenging goals.

The second theme concerned the ability to collaborate with colleagues. English language practitioners approved that the ability to achieve common instructional goals, to accept colleagues’ constructive feedback and opinions, to share successful instructional experiences with them, and to support one another in difficult situations in the educational setting were noticeable elements that constitute an educational team with a strong sense of collective efficacy. Working in an educational setting which is characterized by collaborative atmosphere and shared responsibility improves teachers and instructors’ personal and collective beliefs and tremendously influences their academic accomplishment.

To be able to cope with difficult situations in educational settings was the other mentioned theme. The participants enumerated the ability to cope with limited or lack of instructional materials and equipment, crowded classes, students with different English ability levels and cultural backgrounds, and other system constraints as essential characteristics of an educational setting with strong collective efficacy beliefs. They emphasized that a high sense of collective efficacy empowers teachers and instructors to cope with the demanding conditions in their work place and enables them to overcome difficulties.

English language teachers and instructors also reported that the ability to communicate effectively with the administration, the staff, the students, and their parents was another quality of an educational setting with high collective efficacy perceptions. They believed that building effective communication with the staff and the students was the key element which could enrich the quality of an educational organization.

According to the English language practitioners, one of the most eminent themes which characterize a team of teachers with high collective efficacy is decision-making capability. The ability to carry out decisions with respect to such issues as teaching and assessment methods, instructional goals and the ability to provide input in making other key educational and organizational decisions exemplifies teachers with high collective efficacy. Collective teacher efficacy is enhanced when teachers are bestowed the ability to exert control over instructional and organizational decisions in their work place.

Another frequently mentioned theme was the ability to create a positive climate. EFL teachers emphasized that teachers’ capability to create a positive school atmosphere, to provide a safe place for the students, and to improve school environment is what signifies an educational setting with a high level of collective efficacy. Since collective teacher efficacy is significantly related to academic climate and in turn to students’ achievement, it is vital for an educational system to struggle to create and maintain an educational climate in which both the teachers and the students feel at peace. In this respect, teachers can play a key role. They can provide an inclusive classroom atmosphere in which the students can feel good about themselves and what they are accomplishing in the class.

The ability to keep discipline was the other important theme that was enumerated by the participants. They stated that it is essential for a competent team of teachers to be able to prevent and control disruptive student behavior. To develop a high sense of collective teacher efficacy, teachers need to have established a set of rules and principles to follow in order to provide a well-ordered, disciplined educational setting in which shared instructional goals can be achieved.

The results of the content analysis of the interviews served as the basis of the development of a 32-item initial model of English language teacher collective efficacy. The 32-item initial model of English language teacher collective efficacy, its components, the items, and sample items are presented in Table (for more information refer to Appendix A).

Table 2. The 32-item initial model of English language teacher collective efficacy

5.2. Results of the quantitative section

In order to answer the second research question, “Does English language teacher collective efficacy scale (ELTCES) show indices of construct validity and suitably fit the proposed collective efficacy model?” the gathered date underwent exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. A one-way ANOVA was performed to test the third research question “Do English language teachers and instructors in the three educational contexts of high school, English language institute, and university differ significantly in terms of their collective efficacy beliefs?”

5.2.1. Exploratory factor analysis

Since the instrument showed a high reliability (.93) in the pilot study, the instrument was further analyzed to inspect whether it was factorable. First, the suitability of the data for factor analysis with respect to the sample size and the strength of the relationship among the variables was scrutinized. Since 405 English language teachers participated in the study and the results showed that many values in the correlation matrix were above .3, the data were considered to be factorable (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013).

Then, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were inspected. In the present study, the value of .94 was obtained for KMO and the value of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (.000) approving that the data were factorable. Thus, the data were submitted to Principal Component Factoring with Varimax rotation which yielded six factors with eigenvalues greater than one, accounting for 57.38% of the total variance (Table ).

Table 3. Total variance explained for 32 items

Regarding the fact that Kaiser Criterion yields too many components with eigenvalues greater than one, it is strongly suggested to inspect the scree plot as well (Pallent, Citation2013). Examining Cattell’s (Citation1966) scree test, the researchers detected a clear break between the second and the third components and another break after the fourth component which suggested that three or four factors could be extracted; both solutions were examined.

When the three factor solution was tried, items related to “ability to collaborate with colleagues” either loaded across “instructional capability” or “decision making capability” or they did not load on any of the factors. However, the loadings were low. When the four factor solution was inspected, the items related to “ability to collaborate with colleagues” appeared as a separate factor and the solution seemed more interpretable. Consulting experts in the field, three statisticians who were also familiar with developing scales in social sciences, the researchers decided to keep the fourth factor because it was regarded as a significant factor when measuring collective teacher efficacy. Therefore, the four factor solution was further examined through the process of scale development.

Inspecting the first factor with an eigenvalue of 11.08 which accounted for 34.62% of the total variance, the researchers set as a criterion loadings higher than .50 to further analyze the items. Thus rotated component matrix was examined and the items with loadings smaller than .50 were removed (Table ).

Table 4. Rotated component matrix with 32 items

As a result, items 8, 12, 17, 20, 23, 24, 29, and 30 were discarded. Concerning items 14 and 15, the researchers decided to eliminate them as well since they loaded on the fifth factor and did not belong to the same component. Item 10 was also removed for it was the only item which loaded on the sixth component. The remaining items were further scrutinized. Inquiring domain experts’ judgments, the items which loaded on more than one factor were kept and assigned to the component which showed a higher loading on the condition that it was thematically relevant. It resulted in a clear and easily interpretable structure with 21 items and four factors the loadings of which ranged from .51 to .76 (Table ).

The four extracted factors, based on their commonalities, were labeled as: Efficacy in collaboration with colleagues, efficacy in decision making, efficacy in instruction, and disciplinary and coping efficacy. Table presents the four factors and their corresponding description and items.

Table 5. Rotated component matrix with 21 items

Table 6. Factors and their corresponding items

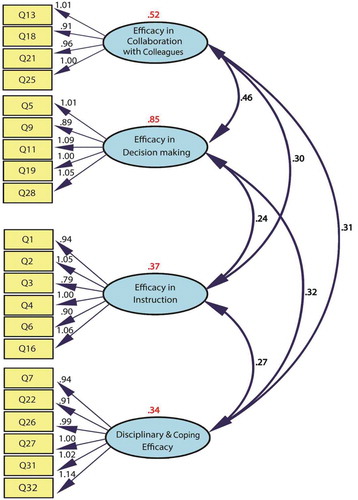

5.2.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

Before submitting the 21-item hypothetical model to confirmatory factor analysis, the reliabilities of the scale and the four subscales were calculated utilizing Cronbach’s alpha. Table presents the obtained total reliability and the reliabilities for the four subscales. The total reliability was .90 and the reliabilities for the four subscales were .80 for efficacy in collaboration with colleagues, .84 for efficacy in decision making, .81 for efficacy in instruction, and .81 for disciplinary and coping efficacy.

Table 7. Total reliability and the reliabilities of the four subscales

To obtain a well-specified model, well-established indices, i.e., tests of absolute fit and tests of incremental fit were employed. The results are presented in Table .

Table 8. Absolute and incremental fit indices for CFA model

As Table shows, for Chi-Sq, GFI, AGFI, and RMSEA the values of 2.7, .90, .87, and .066 were obtained, respectively. As for IFI, TLI, and CFI, the obtained values were .91, .90, and .91, respectively. The results indicated that all the values exceeded the minimum acceptance cut-off points; that is, values greater than .9 for IFI, TLI, CFI, and GFI indices, a value greater than .85 for AGFI (Bollen, Citation1989; Byrne, Citation2001; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) and a value less than 3 for Chi-Squared statistic (Sharma, Citation1996). Also, a value of .08 or less specifies a good fit for RMSEA (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

As Figure shows, the confirmatory factor analysis verified a four-factor model. The loadings between the latent factors and the items proved to be significant at p < .001. The results also showed that the covariance among the factors were significant at p < .001. None of the 21 items were discarded since all of them loaded on their perceived factors which resulted in a 21-item English language teacher collective efficacy scale (Appendix B).

5.2.3. Descriptive statistics

To answer the third research question “What is Iranian English teachers and instructors’ level of collective efficacy?”, descriptive statistics of the 21-item ELTCES and its four dimensions for the whole sample, descriptive statistics of the four dimensions of the 21-item ELTCES in different educational context, and descriptive statistics for the 21-item ELTCES with respect to educational context were obtained.

Table presents the mean and SD as well as the minimum and maximum of the 21-item ELTCES and its four dimensions for the whole sample. The English practitioners’ scores were obtained for the four dimensions as well as the total ELTCE (English language teacher collective efficacy) by adding up the selected options (from 1 to 6) in each item. The higher the value of a score designates the higher level of collective teacher efficacy in each factor and the total ELTCE. Since the four factors of ELTCES do not contain the same number of items, to facilitate comparison, mean divided by the number of items (M/N) was used as the basis of comparison in the study. For example, the mean of efficacy in collaboration was divided by four, but the mean of efficacy in decision-making was divided by five since they contained four and five items, respectively.

Table 9. Descriptive statistics of the 21-item ELTCES and its four dimensions for the whole sample

According to the mean divided by the number of items (Table ), the total ELTCE showed a value of 4.23 out of 6. The order of the level of collective efficacy for English practitioners from the highest to the lowest was as follows: (1) Efficacy in collaboration (M/N = 4.57), (2) Efficacy in instruction (M/N = 4.34), (3) Disciplinary and coping efficacy (M/N = 4.34), and (4) Efficacy in decision-making (M/N = 3.70).

In this study, the M/N values below 3 are considered as a low level of collective teacher efficacy (1 = none at all, 2 = very little, 3 = little). The M/N values between 3 and 5 (4 = some degree) are regarded as an average level of collective teacher efficacy (values below 4 are regarded as a below average and above four as an above average level). The M/N values above 5 (5 = quite a bit, 6 = a great deal) are viewed as a high level of collective teacher efficacy. Accordingly, the total ELTCE and all the factors except for efficacy in decision-making (M/N = 3.7) showed above average values.

It is worth mentioning that with regard to the total obtained score, out of the minimum possible score of 21 and maximum possible score of 126, a score below 64 is considered as a low level of collective teacher efficacy (1 = none at all, 2 = very little, 3 =\ little), between 64 and 104 (4 = some degree) as an average level of collective teacher efficacy, and above 104 (5 = quite a bit, 6 = a great deal) as a high level of collective teacher efficacy.

Table displays the descriptive statistics of the four dimensions of the 21-item ELTCES in different educational context. A total of 126 EFL high school English teachers, 178 EFL language institute teachers, and 101 EFL university instructors and professors constituted the sample. For efficacy in collaboration the mean score for high school teachers was 18.6 and the SD was 2.8. For English language institute teachers the mean was 18.5 with the SD of 3.2, and for university instructors the mean and SD were 18.3 and 2.9, respectively.

Table 10. Descriptive statistics of the four dimensions of the 21-item ELTCES in different educational context

For efficacy in decision making, the mean scores for high school teachers, English language institute teachers, and university instructors were 20.2 (SD 4.0), 18.9 (SD 5.6), and 16.2 (SD 4.5), respectively. With respect to efficacy in instruction, the mean score for English language institute teachers was 27.3 (SD 3.7), for university instructors was 25.9 (SD 3.3), and for high school teachers was 24.9 (SD 3.9). Regarding disciplinary and coping efficacy, the mean score for English language institute teachers was 27.1 (SD 3.4), for high school teachers was 25.6 (SD 4.3), and for university instructors was 25.5 (SD 3.8).

Table illustrates the descriptive statistics for the total ELTCE with respect to educational context. English practitioners in the three educational contexts showed an average level of ELTCE (a total mean score between 64 and 104). It was further found that English language institute teachers exhibited the highest total collective efficacy level (91.7) while university instructors displayed the lowest level (84.3). The obtained collective efficacy level for the high school teachers was 87.8.

Table 11. Descriptive statistics for the 21-item ELTCES with respect to educational context

5.2.4. Inferential statistics

To inspect whether there existed a significant difference in EFL teachers ELTCE level with respect to different educational contexts (school, university, and institute), a one-way ANOVA was applied.

Drawing on the data illustrated in Table , educational context had a significant effect (F = 10.7 p < .000) on the ELTCE level. According to Table which presents the mean score for each of the three contexts, English language institute teachers displayed the highest collective efficacy level whereas university instructors showed the lowest level.

Table 12. The result of the one-way ANOVA on the effect of academic qualification on collective teacher efficacy

To locate the exact difference, Scheffe test was inspected. The results are displayed in Table . The findings revealed that the difference in the level of ELTCE between English language institute and university was significant at p < .01. Considering their mean scores, this is indicative of English language institute teachers’ significantly higher level of collective efficacy compared to the university instructors’. The difference between the two contexts of English language institute and high school teachers was not significant. The mean difference of high school teachers and university instructors with English language institute teachers were 2.84 and 7.37, respectively.

Table 13. Results of Scheffe test on the total ELTCE for different educational context

6. Discussion and conclusion

In educational contexts, the ELT community has been aware of the great impact of teacher efficacy on English language teachers’ performance (Akbari & Abednia, Citation2012; Akbari & Tavassoli, Citation2014; Akomolafe, & Ogunmakin, Citation2014; Cadungog, Citation2015), but collective teacher efficacy has been less emphasized. Hence, to address the complex nature of collective teacher efficacy which is believed to be greatly sensitive to the teaching context and the subject matter which is being taught (Bandura, Citation1997), the current study has tried to investigate the construct of collective teacher efficacy in different educational contexts by means of developing a context-specific collective teacher efficacy scale which uniquely reflects ELT settings.

After the major themes of collective teacher efficacy were identified by English language school and institute teachers and university instructors through a series of in-depth semistructured interviews, the data were analyzed utilizing thematic content analysis. After the process of content analysis of the interviews was completed and the obtained results were compared with the supportive literature, seven major themes emerged. The participants identified instructional, decision making, and coping abilities as well as the ability to collaborate with colleagues, to communicate effectively, to create a positive climate, and to keep discipline as the underlying factors.

The common themes and categories that emerged from the qualitative data were used as the basis of the development of the context-specific scale of English teacher collective efficacy beliefs after a process of review and discussion with English practitioners and university faculty members familiar with the concept of collective efficacy.

Afterward, the newly developed instrument was tried on 405 English language teachers and instructors in the three aforementioned educational contexts. Then, exploratory factor analysis was applied the result of which was a clear and easily interpretable structure with four factors.

The result of the confirmatory factor analysis was also encouraging. It specified a four-factor model which yielded that the proposed model was a good fit for the data. All the items loaded on their corresponding factor and showed a significant relationship with it. The four extracted factors, “efficacy in collaboration with colleagues,” “efficacy in decision making,” “efficacy in instruction,” and “disciplinary and coping efficacy,” are supported by the existing literature.

The outcomes of the present study reinforce the existing literature. The findings are echoed by Goddard, Hoy, and Woolfolk Hoy (Citation2004, p. 10) who argue that “the more teachers have the opportunity to influence instructionally relevant school decisions, the more likely a school is to be characterized by a robust sense of collective efficacy.” They further offer means by which teachers can influence relevant school decisions, such as control over curriculum, teaching materials, communication with parents, and disciplinary policies. Influencing relevant school decisions empowers teachers to impact on the instructional and more school wide decisions.

Ross and Gray (Citation2006) also acknowledge that collective teacher efficacy is improved if teachers are provided with occasional opportunities to share their skills and experiences collaboratively, to receive actionable feedback on their performance, and to be involved in school-wide decision making. They further emphasize the effect of building instructional knowledge and skills.

As for the efficacy in cooperation with colleagues, Pugach and Johnson (Citation2002, p. 6) highlight that “In collaborative working environments, teachers have the potential to create the collective capacity for initiating and sustaining ongoing improvement in their professional practice, so each student they serve can receive the highest quality of education possible.” In such a collaborative educational setting, teachers are able to elevate the instructional quality by sharing their successful teaching experiences with their colleagues, looking for their constructive feedback and opinions. The shared interactions serve as the basis for building collective efficacy and collaboration among teachers is a step forward to build collective efficacy (Carpenter, Citation2015; Goddard et al., Citation2015).

Emphasizing collaborative educational settings, Viel-Ruma, Houchins, Jolivette, & Benson (Citation2010) also assert that interpersonal relations with colleagues, superiors, parents, and students influence teachers’ perceptions regarding their collective capability in attaining institutional objectives.

By the same token, Lee et al. (Citation2011) maintain that if an atmosphere of collaboration and mutual trust is built, both collective teacher efficacy and teachers’ relationship with students are improved. They further add that the collaborative atmosphere in the work place provides teachers with the opportunities to share their experiences and elevates school’s educational quality.

The results of some recent studies on the issue also support the findings of the current study. Berebitsky & Salloum’s study (Citation2017) discovered a significant relationship between school’s collective efficacy level and teachers’ instructional practices. They came to the conclusion that turning to colleagues for instructional advice enhances teachers’ collective efficacy. Similarly, Siciliano (Citation2016) revealed that knowledge access and peer influence had significant relationship with teachers’ efficacy perceptions. They observed that only teachers who had faith in their colleagues’ abilities turned to them for advice. Prelli (Citation2016) also found that a collaborative atmosphere increased teachers chance to share their teaching experiences and to get feedback from colleagues.

Disciplinary and coping efficacy dimension of collective teacher efficacy is also supported by the related literature. According to Bandura (Citation1997), teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs reflect an emergent group property that influences the extent to which teachers in a school make an effort to cope with diverse challenge well realizing that the shared beliefs in the level of group bring about the expected changes and results even if their individual motivation is reduced when they face challenges and failures in school settings. In this regard, Godard et al. (Citation2000) assert that teachers with high levels of collective efficacy are persistent when dealing with difficulties.

High sense of collective efficacy enables teachers to consider challenging goals and to overcome difficulties. Such efficacious teachers would help all students to succeed via building positive connections with them (Jahnke, Citation2010). In his study, Ross (Citation1995) discovered that effective teachers set more challenging goals for their students and themselves. They assume themselves responsible for the achievement of their students’ learning, and they make an effort to deal effectively with difficulties.

Disciplinary and coping efficacy is supported by more recent studies as Nordick (Citation2017) and Yu, Wang, Zhai, Dai, and Yang (Citation2015) affirm that current increased school accountability has lead teaching to become increasingly demanding. They recommend that teachers need to elevate their coping abilities in order to overcome the negative influence and empower themselves with group-referent abilities to perform as a whole

Likewise, Prelli (Citation2016) found that when teachers face with high levels of pressure in their work, their efficacy beliefs decrease. External threats to efficacy such as an increase in the percentage of English language learners in a school threaten the efficacy of the staff if teachers are not confident that they have the required ability and skill. It was concluded that providing opportunities for collaborative sharing of experiences and increasing teachers’ chance to observe peers implementing best practice strategies can reinforce teachers’ beliefs regarding their power in confronting the most challenging situations.

The amount of stress and depression that people experience in threatening or difficult circumstances as well as their level of motivation are influenced by their beliefs in their coping capabilities. People who think are not capable of managing threats suffer from high anxiety arousal. They live with their coping deficiencies which, in turn, impairs their level of performance. Perception of coping efficacy “regulates avoidance behavior as well as anxiety arousal. The stronger the sense of efficacy the bolder people are in taking on taxing and threatening activities” (Bandura, Citation1994, p. 5). Collaborative environments inspire staff to work as a unified team and to overcome obstacles. Faculties that built a network of collaboration and exchanges of expertise and guidance tend to build stronger collective efficacy beliefs (Moolenaar, Sleegers, & Daly, Citation2012).

Instructional capability as reflected by efficacy in instruction is also emphasized by a great many research projects. Hoy and Spero (Citation2005) found that teachers’ efficacy beliefs drastically influenced their teaching efforts, goals, and level of aspiration. Similar results are reported by Riggs and Enochs (Citation1990) and Riggs (Citation1995) who found that teachers with higher levels of efficacy tended to spend more time teaching. They tended to implement new ideas and methods to adjust to the specific needs of their students. Czerniak & Schriver-Waldon’s (Citation1994) study also showed that teacher efficacy positively influence the use of student-centered learning strategies.

In this respect, Ashton and Webb’s (Citation1986) found that “teachers with a high sense of efficacy seemed to employ a pattern of strategies that minimized negative affect, promoted an expectation of achievement, and provided a definition of the classroom situation characterized by warm interpersonal relationships and academic work” (p. 125).

In his article, Gavora (Citation2011) reviewed the results obtained by a great many researchers who have also reported that teacher efficacy beliefs can positively affect the extent to which teachers make efforts and persist in the face of difficulties, implement new instructional practices, increase pupils’ academic achievement and success, show greater levels of organization, planning, and enthusiasm, and use less teacher-directed whole-class instruction.

The findings of this study are further supported by Tschannen–Moran and Barr (Citation2004) Collective Teacher Beliefs Scale which includes two dimensions of instructional strategies and teacher collective efficacy for student discipline, Olivier’s (Citation2001) Teacher Efficacy Belief Scale-Collective Form which incorporates carrying out decisions and plans and managing student misbehavior, and Skaalvik & Skaalvik’s (Citation2007)Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy Scale which is a one-dimensional measure the items of which focus on instruction, motivation, controlling student behavior, addressing students’ needs, and creating a safe environment.

The present study offers more precise results since the 21-item ELTCES moves beyond the existing collective measures for two reasons. First, being a context-specific instrument, it provides more meaningful and detailed information about what teachers and instructors are able to accomplish in the specific ELT context. Second, compared to other collective efficacy measures, it captures a wider range of teaching tasks in ELT context. Instructional and disciplinary efficacy are emphasized in other scales, but decision making and cooperative efficacies are less emphasized areas. Thus, by focusing on these four dimensions which also incorporate aspects of the ability to cope with difficult situations, the ability to create a positive climate, and the ability to communicate effectively as were reflected in items 18 “How much can we, English language teachers at this school, do to teach our students successfully regardless of such problems as the students’ cultural and proficiency differences?”, item 21 “How much can we, English language teachers at this school, do to create a safe and sound atmosphere for our students?”, item 9 “How much can we, English language teachers, do to communicate effectively with the school administration?”, and item 12 “How much can we, English language teachers, do to communicate effectively with our colleagues at this school?”, respectively, the ELTCES offers more insightful results (for more information refer to Appendix B).

Although the 21-item final model proved to be a valid tool and the obtained results verified the final model’s construct validity, this new measure, undoubtedly, needs to be further tested and validated by future empirical studies. Since collective efficacy is immensely influenced by contextual factors, the findings of such empirical studies in different pedagogical contexts may result in major or minor modifications in the model offered here.

Inspecting Iranian English teachers and instructors’ total level of collective efficacy and the four dimensions for the whole sample and in different educational context, the descriptive statistics revealed above average values for the total ELTCE and all the factors except for efficacy in decision-making the value of which was below average.

With respect to efficacy in collaboration, the mean score for high school teachers was the highest (18.6), the second highest mean score belonged to English language institute teachers (18.5). The lowest mean score was university instructors’ (18.3). This indicated that the perceptions of Iranian high school teachers concerning collaboration with colleagues, the students, the parents, and the administration were stronger than teachers and instructors in the other two educational settings. However, considering the fact that the difference was negligible, one possible explanation could be that while at school settings teachers communicate with the students’ parents often, it is less common at institutes, and not common at universities. As a consequence, it can be concluded that aside from efficient communication with parents, English practitioners in the three educational contexts presented similar collective efficacy levels with regard to efficacy in collaboration.

Concerning efficacy in decision-making, the mean score for high school teachers, English language institute teachers, and university instructors were 20.2, 18.9, and 16.2, respectively. In other words, high school teachers revealed stronger perceptions in decision-making. That is, they perceived themselves to be much more influential in educational and school-wide decision-making than institute teachers or university instructors. In contrast, university instructors expressed the lowest level of decision-making efficacy indicating that their perceptions of their effective role in influencing important decisions were lower than those of the teachers in the other two educational settings.

With respect to institute teachers it is understandable why their efficacy level in decision-making is lower than that of high school teachers since as, they highlighted, institute teachers do not have any role in making such important instructional decisions as selecting teaching strategies and assessment issues. They have to follow the strict institute’s procedures. Regarding university instructors, as they expressed, while they are capable of influencing instructional decisions and goals, they cannot take part in making wider important decisions which are made to run the department and university.

Since, decision-making capability is one of the most prominent factors that characterize a team of teachers with high collective efficacy (Goddard et al., Citation2004; Ross & Gray, Citation2006), to enhance collective teacher efficacy perceptions, teachers, and instructors should be bestowed the ability to exert control over both instructional and organizational decisions. Educational leaders should have policies to reinforce instructors’ collective perceptions by building an inclusive atmosphere in which faculty members are provided with opportunities to provide input in making key educational and organizational decisions.

Pertaining to efficacy in instruction, the highest mean score was obtained for English language institute teachers (27.3), and at lower levels for university instructors and high school teachers with mean scores of 25.9 and 24.9, respectively. That is, institute teachers revealed stronger instructional ability perceptions, such as the ability to promote creativity in students, to improve their motivation, to possess language teaching knowledge and skills, and to use effective teaching strategies and methods compared to university instructors and high school teachers.

Most possibly, the difference lies in the strict disciplines practiced at institutes with respect to the high standards with which teachers are employed and later evaluated. In other words, initially, teachers with high instructional capabilities are employed and this high level is preserved by regular observations, professional development programs and workshops.

In the case of Iranian English high school teachers, the employment procedures proceed without a correct evaluation of the instructional ability of the teacher. More importantly, there are literally no established plans and programs which could develop their efficacy level. There are no regular, useful educational development programs, and if there rarely are, high school teachers are reluctant to take part due to their lack of interest, lack of time, and lack of effective evaluation by the ministry of education or even the heads of the major districts.

Relating to university instructors, the assumption is that they are instructionally capable when they join the educational system. Nevertheless, since they do not regularly attend professional development programs and workshops which are identified as profoundly influential factors in enhancing teacher self-efficacy and collective efficacy (Bandura, Citation1993; Cadungog, Citation2015; Goddard et al., Citation2000; Watson, Citation2006), and they do not have the chance to receive constructive feedback which could positively affect their efficacy (Goddard et al., Citation2000; Goddard, Hoy, & Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2004; Goddard et al., Citation2004), their initial high collective efficacy decreases.

In relation to disciplinary and coping efficacy, the mean score for English language institute teachers was 27.1, for high school teachers was 25.6, and for university instructors was 25.5. This shows that English language institute teachers had significantly more positive efficacy perceptions regarding such disciplinary issues as controlling and preventing disruptive behavior, and creating a safe and sound atmosphere for the students, as well as coping with such difficult situations as students’ cultural and proficiency differences and low English ability compared to the English practitioners in the two other educational contexts.

High school teachers have to deal with the day-to-day difficult situations such as crowded classes with students who are very different with respect to their English ability level or even cultural background. Other problems like limited resources or lack of instructional equipment are also very common at high schools. Consequently, they might be discouraged when they are challenged by such setbacks and they do not have the ability to overcome them effectively.

Lack of instructional materials and equipment is not a common problem which university instructors have to deal with, but their profession sometimes gets very difficult to cope with when they have to deal with such challenging situations as students with different proficiency levels or students who are very difficult to deal with.

In English language institutes, the condition is much better since students enter the institute through a placement test, the teacher is not challenged by students’ different English ability level. Moreover, institutes are well equipped with instructional materials, and classes are not crowded. In addition, institutes’ established set of rules and principles provide a well-ordered, disciplined educational setting in which teachers do not have to deal with very difficult students.

Comparing the three educational contexts with reference to the overall collective efficacy perceptions, the results of the one-way ANOVA showed that the highest collective efficacy level was exhibited by English language institute teachers. High school teachers showed the second highest level whereas university instructors showed the lowest level. Scheffe test located the exact difference; the significant difference was between English language institute teachers and university instructors. That is, English language institute teachers’ showed a significantly higher level of total ELTCE compared to the university instructors.

Nonetheless, reasons other than professional development programs, educational workshops, colleagues’ constructive feedback and opinion, regular observation, lack of educational instruments, might be influential in the process of the developing of high school teachers, and university instructors’ collective efficacy. As a consequence, further studies are still required to be conducted in different educational contexts the results of which would undoubtedly offer a broader perspective on the issue and would provide educators with effective ways to enrich the construct. Furthermore, since no other study on the effect of educational contexts on English practitioners’ collective efficacy was found in the collective efficacy literature by the researchers of the study, future studies, both quantitative and qualitative ones, can offer a deeper understanding on the topic.

Given the interplay of contextual variables with collective teacher efficacy, the results of this study broaden and deepen our perception of the construct of collective teacher efficacy. The outcomes of the current research project are also expected to provide us with a deeper understanding of the true nature of this noticeable construct and to make a valuable contribution to the growing body of literature on the construct of collective teacher efficacy since the study of collective efficacy beliefs “holds promise for deeper theoretical understanding and practical knowledge concerning the improved function of organized activity, particularly schooling” (Goddard et al., Citation2004, p. 10). Furthermore, the results “would help explain the process by which teacher efficacy develops and might lead to insights into how to better enhance the self-efficacy and collective efficacy of teachers” (Klassen, Tze, Betts, & Gordon, Citation2011, p. 24). The findings can also be a step forward to discern different ways to elevate collective teacher efficacy in ELT educational contexts which in turn would influence other educational accomplishments.

Further research, using diverse methodologies, which can provide detailed information about EFL school and institute teachers as well as university instructors’ perceptions concerning what builds and fosters collective efficacy perceptions in the specific ELT contexts are strongly recommended. Educational leaders and educators are also invited to turn their attention to improving collective teacher efficacy in the ELT educational contexts of high schools and universities where collective teacher efficacy perceptions need to be further developed and maintained.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Sadegh Bagheri

The authors of the present study intended to investigate Iranian collective teacher efficacy beliefs in different ELT settings through developing a context-specific English language teacher collective efficacy scale. To this end, employing a mixed-method design, the current study explored English language teachers and instructors’ perceptions regarding the constituent elements of collective teacher efficacy through a qualitative research design (in-depth-interview) and developed and validated a new collective teacher efficacy scale and utilized it in detecting and comparing EFL school and institute teachers as well as university instructors’ perceptions and level of collective teacher efficacy in the quantitative phase of the study. The results provide detailed information about their perceptions concerning what builds and fosters collective efficacy perceptions in their specific ELT context. Thus, the results can contribute significantly to the current interest in discovering different ways which can lead to the improvement of this prominent construct in the educational domain.

References

- Abdeli Soltan Ahmadi, J., Eisazadegan, A., Gholami, M. T., Mahmodi, H., & Amani, J. (2017). The relationship between collective efficacy beliefs and self-efficacy with job satisfaction of secondary school male teachers in Qom. Quarterly Journal of Career & Organizational Counseling, 4(10), 105–124.

- Adams, C. M., & Forsyth, P. B. (2006). Proximate sources of collective teacher efficacy. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(6), 625–642. doi:10.1108/09578230610704828

- Akbari, R., & Abednia, A. (2012). Second language teachers’ sense of self–Efficacy: A construct validation. Teaching English Language and Literature, 13(4), 69–101.

- Akbari, R., & Tavassoli, K. (2014). Developing an ELT context-specific teacher efficacy instrument. RELC Journal, 45(1), 27–50. doi:10.1177/0033688214523345

- Akomolafe, M. J., & Ogunmakin, A. O. (2014). Job satisfaction among secondary school teachers: Emotional intelligence, occupational stress and self–Efficacy as predictors. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 4(3), 487–498.

- Ashton, P. T., & Webb, R. B. (1986). Making a difference: Teachers’ sense of efficacy and student achievement. New York, NJ: RAND Corporation.

- Baleghizadeh, S., & Goldouz, E. (2016). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs, teaching experience and perception of teacher empowerment. Cogent Education, 3, 1–15. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1223262

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self–Efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self–Efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

- Bandura, A. (1994). Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. New York, Plenum.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self–Efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Berebitsky, D., & Salloum, S. J. (2017). The relationship between collective efficacy and teachers’ social networks in urban middle schools. AERA Open, 3(4), 1–1.1. Retrieved May 5, 2018, from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2332858417743927

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17, 303–316. doi:10.1177/0049124189017003004

- Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cadungog, M. C. (2015). The mediating effect of professional development on the relationship between instructional leadership and teacher self– Efficacy. International Journal of Novel Research in Education and Learning, 2(4), 90–101.

- Caprara, G., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Steca, P. (2003). Efficacy beliefs as determinants of teachers’ job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 821–832. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.821

- Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(5), 682–694.

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, 245–276. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

- Chong, W., Huan, V., Klassen, R., Wong, I., & Kates, A. D. (2010). The relationships among school types, teacher efficacy beliefs, and academic climate: Perspective from Asian middle schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 820–830.

- Czerniak, C. M., & Schriver-Waldon, M. (1994). An examination of preservice science teachers’ beliefs and behaviors as related to self-efficacy. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 5(3), 77–86. doi:10.1007/BF02614577

- Eells, R. J. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement ( Doctoral dissertation). Loyola University, Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/133

- Gavora, P. (2011). Measuring the self-efficacy of in-service teachers in slovakia. Orbis Scholae, 5(2), 79–94. doi:10.14712/23363177.2018.102

- Goddard, R., Goddard, Y., Kim, E. S., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration, and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. doi:10.1086/681925

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 479–507. doi:10.3102/00028312037002479

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2004). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3–13. doi:10.3102/0013189X033003003

- Goddard, R. D., LoGerfo, L., & Hoy, W. K. (2004). High school accountability: The role of collective efficacy. Educational Policy, 18(3), 403–425. doi:10.1177/0895904804265066

- Göker, S. D. (2012). Impact of EFL teachers’ collective efficacy and job stress on job satisfaction. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(8), 1545–1551. doi:10.4304/tpls.2.8.1545-1551

- Hattie, J. (2016). The current status of the visible learning research. Paper presented at the third annual Visible Learning Conference, Washington, DC.

- Hawkins, M. R. (2004). Language learning and teaching education: A sociocultural approach. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Henday Al–Mahdi, Y. F., Mohamed Emam, M., & Hallinger, P. (2017). Accessing the contribution of principal instructional leadership and collective teacher efficacy on teacher commitment in Oman. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 191–201. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.10.007

- Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Holanda Ramos, M. F., Silva, S. S., Ramos Pontes, F. A., Fernandez, A., . O., & Furtado Nina, K. C. (2014). Collective teacher efficacy beliefs: A critical review of the literature. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(7), 179–188.

- Hoy, A. W., & Spero, R. B. (2005). Changes in the teacher efficacy during the early years of teaching: A comparison of four measures. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 343–356. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.01.007

- Hoy, W. (2012). School characteristics that make a difference for the achievement of all students: A 40-year odyssey. Journal of Educational Administration, 50(1), 76–97. doi:10.1108/09578231211196078

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jahnke, M. S. (2010). How teacher collective efficacy is developed and sustained in high achieving middle schools ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). College of Education and Leadership Cardinal Stritch University, United States.

- Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M. C., Betts, S. M., & Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher efficacy research 1998–2009: Signs of progress or unfulfilled promise? Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 21–43. doi:10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

- Lee, J. C., Zhang, Z., & Yin, H. (2011). A multilevel analysis of the impact of a professional learning community, faculty trust in colleagues and collective efficacy on teacher commitment to students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 820–830. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.006

- Lin, S. (2013). The relationships among teacher perceptions on professional learning community, collective efficacy, gender, and school level. Journal of Studies in Education, 3(4), 98–111. doi:10.5296/jse.v3i4

- Moolenaar, N. M., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Daly, A. J. (2012). Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy, and student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 251–262. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.001

- Nordick, S. (2017). Fundamental features of fostering teacher collective efficacy: principals’ attitudes, behaviors, and practices ( Doctoral dissertation). Utah State University. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7828&context=etd

- Olivier, D. F. (2001). Teachers personal and school culture characteristics in effective schools: Toward a model of a professional learning community ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Louisiana State University, Louisiana.

- Pallent, J. (2013). SPSS survival manual (5th ed.). UK: MC Graw Hill.

- Prelli, G. E. (2016). How school leaders might promote higher levels of collective teacher efficacy at the level of school and team. English Language Teaching, 9(3), 174–180. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n3p174

- Pugach, M. C., & Johnson, L. J. (2002). Unlocking expertise among classroom teachers through structured dialogue: Extending research on peer collaboration. Exceptional Children, 62, 101–110. doi:10.1177/001440299506200201

- Riggs, I. (1995). The characteristics of high and low efficacy elementary teachers. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, San Francisco.

- Riggs, I., & Enochs, L. (1990). Toward the development of an elementary teacher’s science teaching efficacy belief instrument. Science Education, 74(6), 625–638. doi:10.1002/sce.3730740605

- Ross, J. A. (1995). Strategies for enhancing teachers’ beliefs in their effectiveness: Research on a school improvement hypothesis. Teachers College Record, 97, 227–250.